User login

A worsening abdominal rash

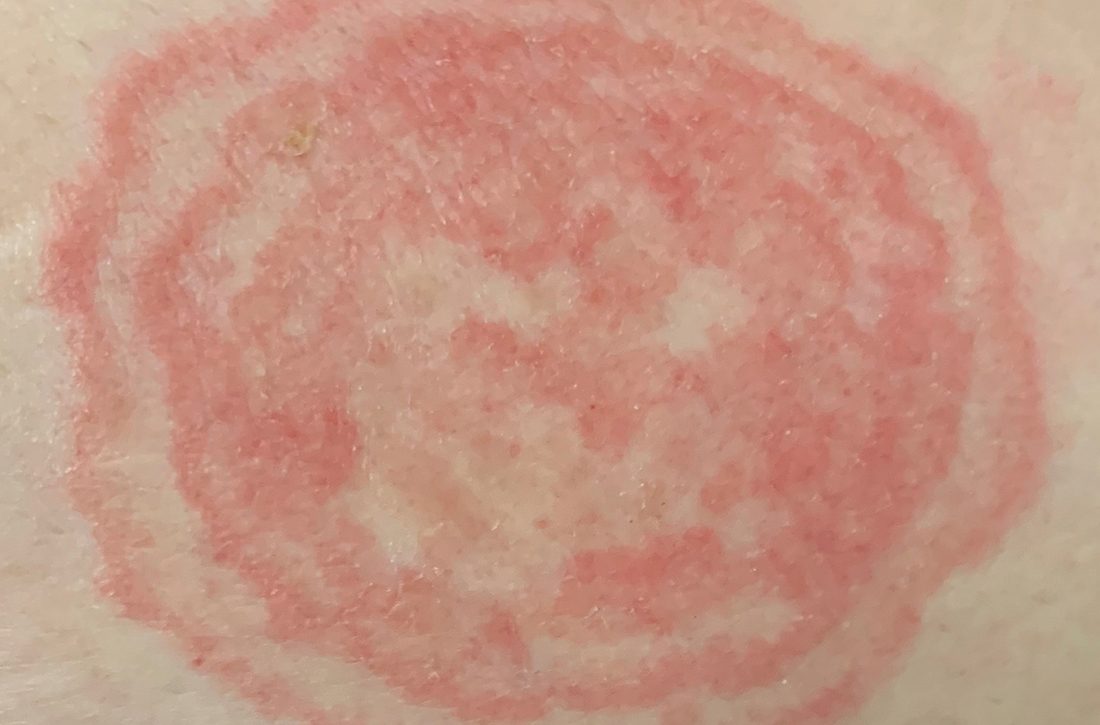

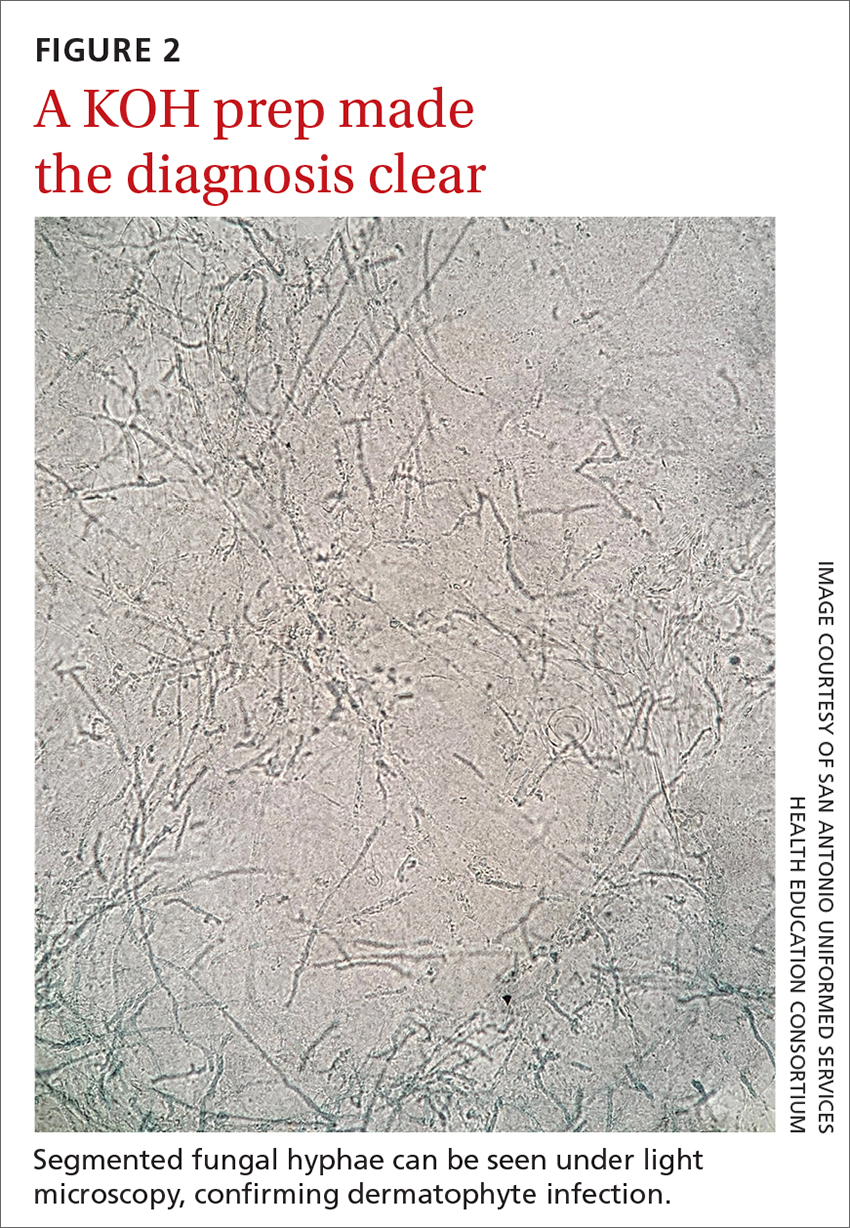

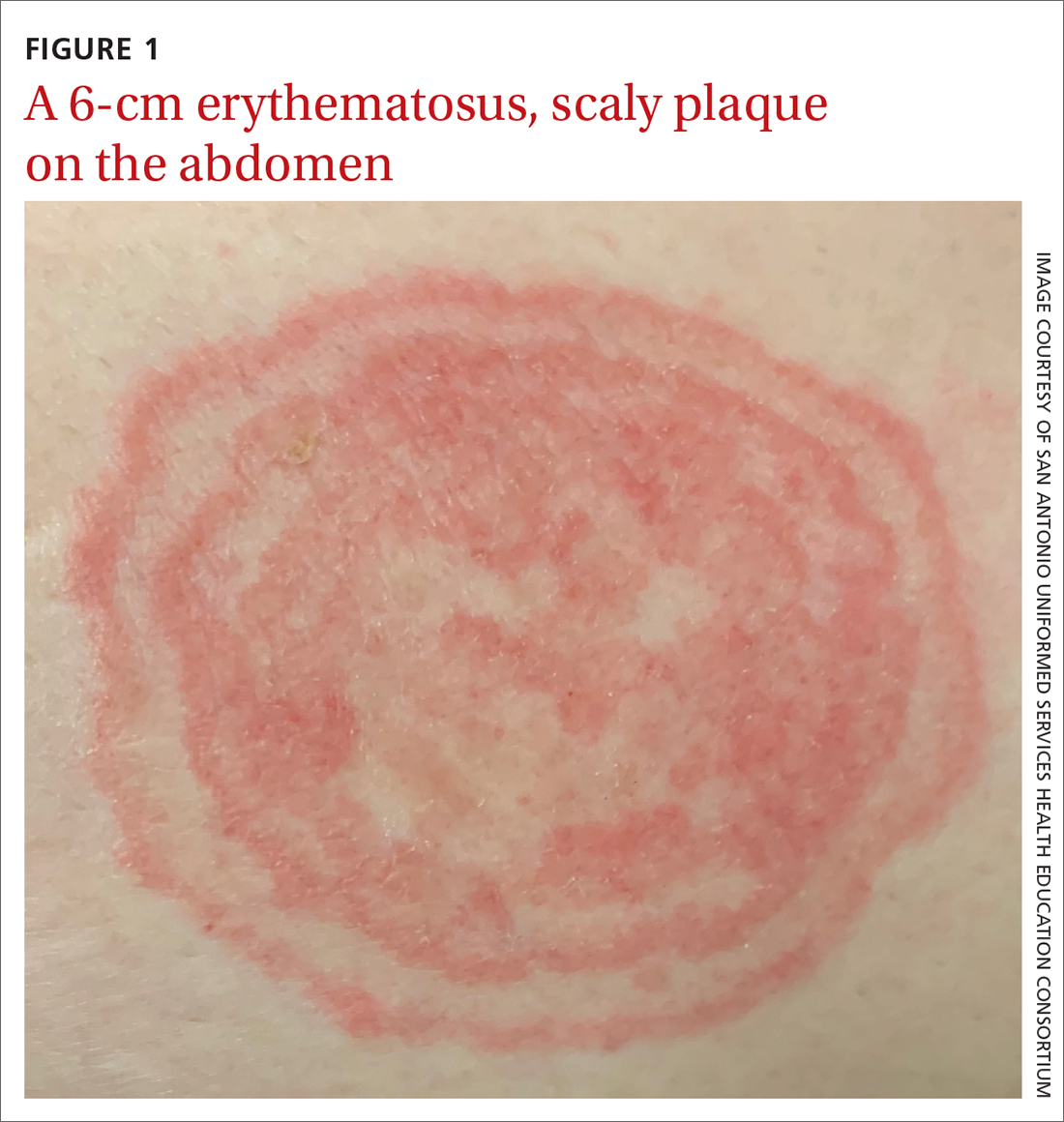

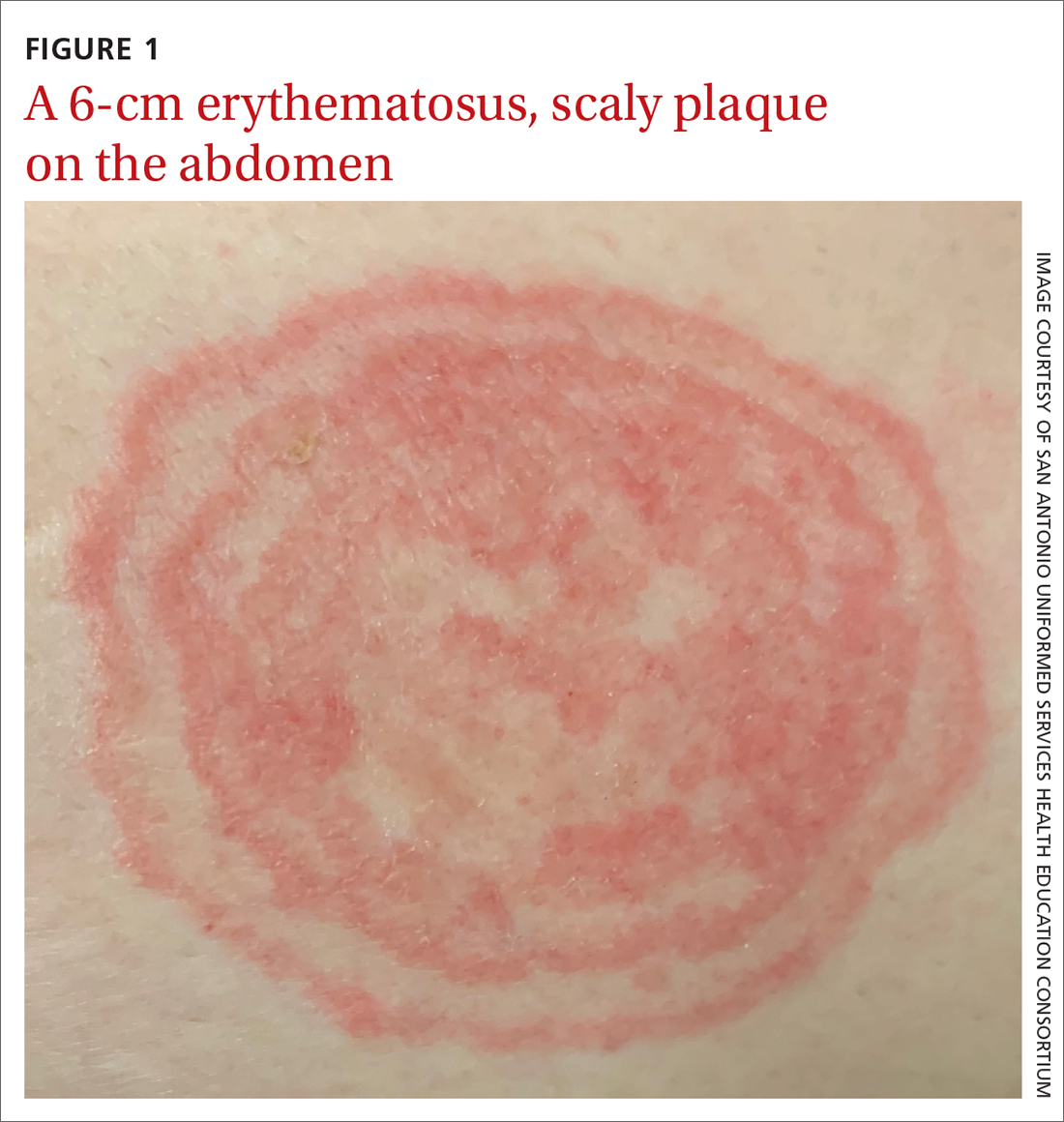

A 48-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented to Dermatology for evaluation of a 6-cm abdominal lesion that had been present for 5 weeks (FIGURE 1). The lesion was originally about the size of a quarter, but it started to enlarge after treatment of an asthma exacerbation with a 4-day course of prednisone. It continued to grow after another physician, likely presuming the lesion was a corticosteroid-responsive dermatosis (eg, nummular eczema, granuloma annulare, or erythema annulare centrifugum), prescribed a 2-week trial of clobetasol ointment. Physical examination revealed a mildly pruritic, 6-cm erythematous plaque with scaly, annular, concentric rings on the left lower abdomen. The patient had no travel history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea incognito

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea incognito, a form of tinea corporis that is exacerbated by the inappropriate use of corticosteroids in the management of a cutaneous fungal infection.1 Furthermore, this patient’s case was consistent with tinea pseudoimbricata, a variant of tinea incognito. Tinea pseudoimbricata is characterized by striking concentric scaly rings that mimic tinea imbricata, a fungal infection caused by the dermatophyte Trichophyton concentricum, which is commonly found in tropical areas.2

A common infection is alteredby steroid use

Tinea corporis has a relatively high prevalence. Approximately 10% to 20% of the world population is affected by fungal skin infections.3

T rubrum is the most common cause of tinea corporis. Other causes include T tonsurans, T interdigitale, T violaceum, Microsporum canis, M gypseum, and M audouinii.

Tinea corporis can be acquired through direct contact with an infected person, animal, or fomite. It may also be acquired through autoinoculation from another area of the body containing a dermatophyte fungal infection. Tinea corporis lesions are usually pruritic, erythematous, annular plaques with overlying scale and central clearing.

How steroid use can change the picture. Treatment with corticosteroids is ineffective for fungal skin infections and causes immunosuppression, allowing the fungus to thrive. This patient had been treated with a topical steroid (clobetasol) for the abdominal lesion caused by tinea corporis, as well as an oral steroid (prednisone) for an asthma exacerbation. These steroid treatments caused the abdominal lesion to morph from the typical appearance of tinea corporis—classically an annular erythematous plaque with overlying scale and central clearing—to an erythematous plaque with striking concentric scaly rings.

Continue to: Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

The differential diagnosis for an annular skin lesion includes not only tinea corporis, but also superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, pityriasis rosea, granuloma annulare, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and nummular eczema.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, like tinea corporis, has scale. But the location of the scale sets the 2 apart. Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum lesions have a central trailing scale, whereas tinea corporis lesions have a peripheral leading scale.4

Pityriasis rosea forms multiple lesions in a “Christmas tree” pattern on the trunk, sometimes beginning with a single herald patch. Our patient’s single lesion with concentric scaly rings was inconsistent with the distribution and quality of the lesions in pityriasis rosea.4

Granuloma annulare lesions are smooth, nonscaly plaques that are most often seen on the dorsal hands and feet. The scaly manifestation of our patient’s lesion was not consistent with this diagnosis.4

SCLE lesions are typically photodistributed on sun-exposed skin (eg, the neck, upper trunk, or arms), whereas our patient’s lesion involved a sun-protected site.4

Continue to: Nummular eczema

Nummular eczema can be differentiated from tinea corporis by potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination. Nummular eczema is characterized by a negative KOH exam and response to topical corticosteroids.4

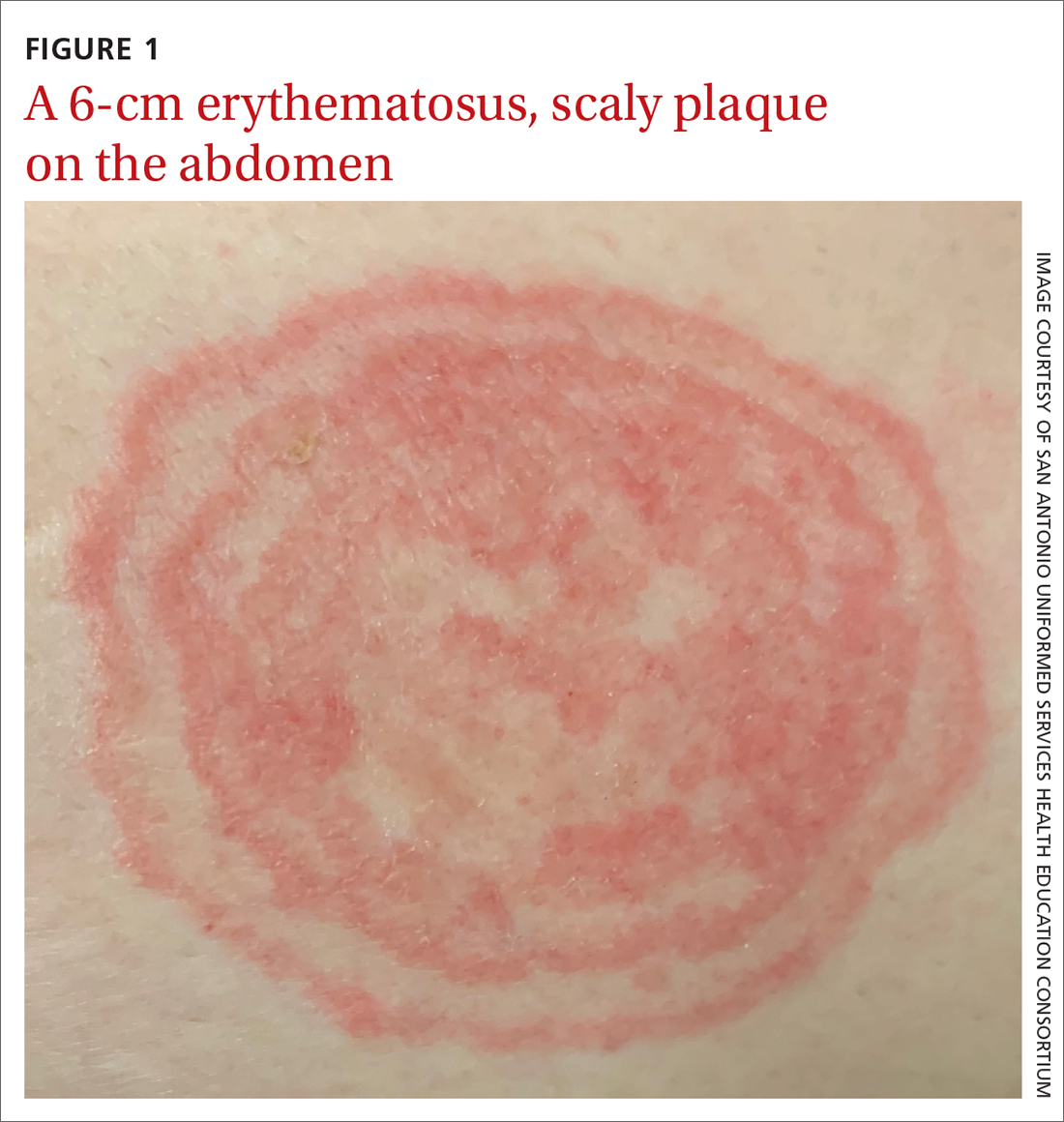

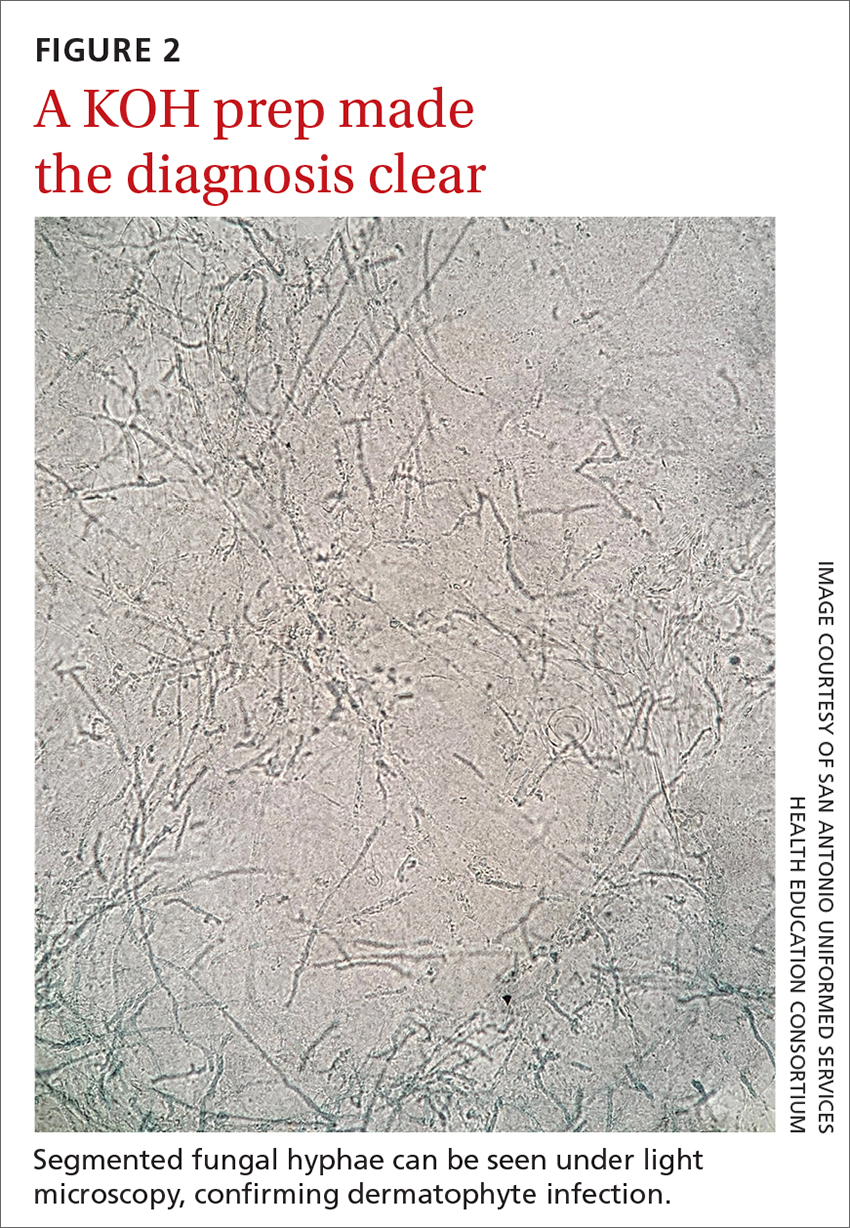

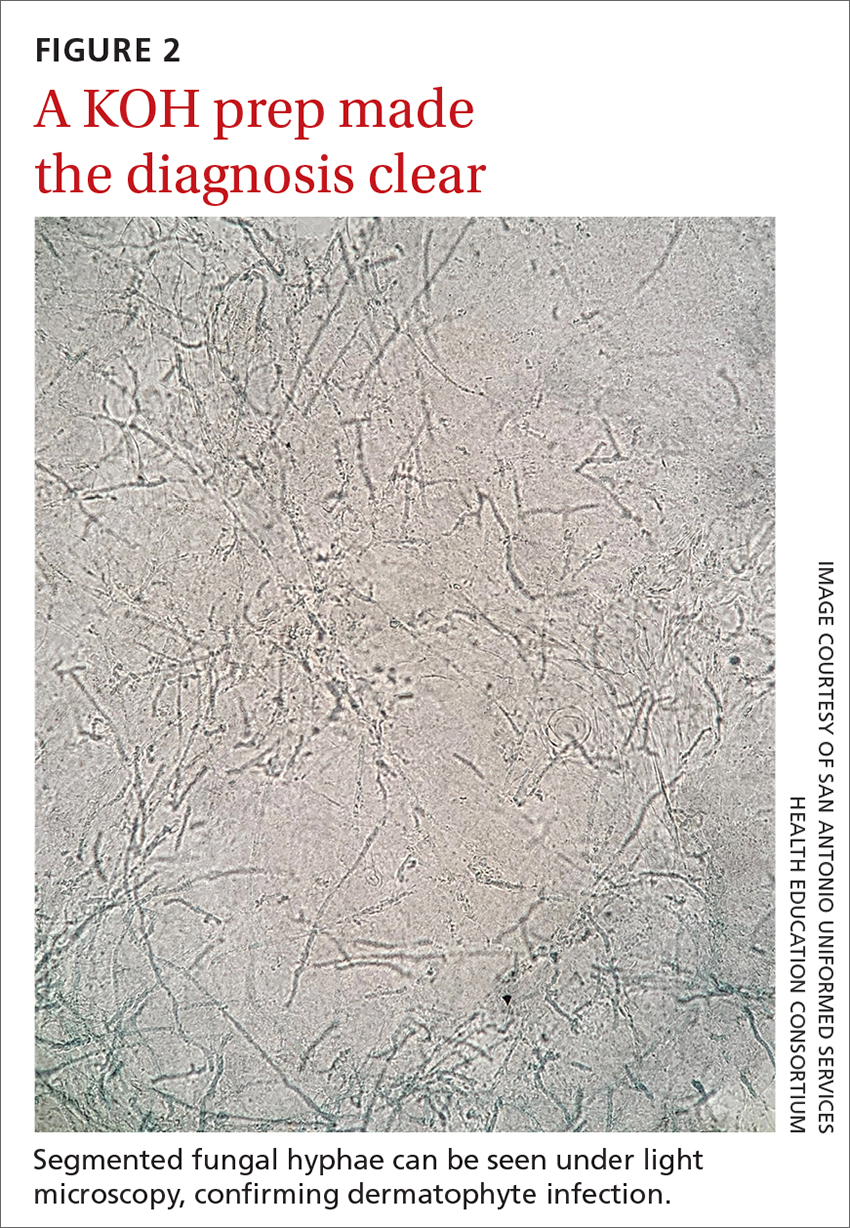

Performing a KOH examination, using the skin scrapings from the active border of a plaque, is useful on any lesion with potential fungal etiology. If the cause is indeed a dermatophyte infection, segmented fungal hyphae will be seen under light microscopy (FIGURE 2).1 If a KOH examination is not feasible, a skin scraping can be performed with a surgical scalpel blade and collected in a sterile urine cup for stain and culture at a qualified laboratory.

Topical and oral antifungal medications combat dermatophyte fungi

Treatments for cutaneous infections caused by dermatophyte fungi, such as tinea corporis, include topical and oral antifungals. The choice of agent depends on the extent of the disease.

Limited, localized disease can be treated topically with allylamines (terbinafine, naftifine) or imidazoles (clotrimazole). Other topical agents, such as butenafine, ciclopirox, and tolnaftate, also may be used.

Extensive disease, or tinea infection of vellus hairs, may require treatment with oral antifungal medications, such as the azoles (itraconazole, fluconazole), allylamines (terbinafine), or griseofulvin. Systemic therapy with oral antifungals has been associated with liver damage; therefore, oral therapy should not be used in patients with liver disease and liver enzymes should be monitored when appropriate.5 Nystatin is not effective in treating dermatophyte fungal infections.1

One complication of the inappropriate use of steroids on a dermatophyte infection is an increased risk of the fungus extending from the superficial skin into the hair follicles in the dermis, resulting in a condition known as Majocchi granuloma. Follicular infection is more severe and requires oral antifungal medication, such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, or griseofulvin.1

Our patient was treated with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks, due to the possibility of follicular infection. After the completion of 4 weeks of therapy, the patient’s cutaneous symptoms had resolved.

1. Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated November 8, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections

2. Lederman E, Craft N, Burgin S. Tinea imbricata in adult. VisualDx. Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52399

3. El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD009992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009992.pub2

4. Unwala R. Approach to the patient with annular skin lesions. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated September 7, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-annular-skin-lesions

5. Wong V, High W, Burgin S. Tinea corporis in adult. VisualDx. Updated March 24, 2019. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52396#Therapy

A 48-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented to Dermatology for evaluation of a 6-cm abdominal lesion that had been present for 5 weeks (FIGURE 1). The lesion was originally about the size of a quarter, but it started to enlarge after treatment of an asthma exacerbation with a 4-day course of prednisone. It continued to grow after another physician, likely presuming the lesion was a corticosteroid-responsive dermatosis (eg, nummular eczema, granuloma annulare, or erythema annulare centrifugum), prescribed a 2-week trial of clobetasol ointment. Physical examination revealed a mildly pruritic, 6-cm erythematous plaque with scaly, annular, concentric rings on the left lower abdomen. The patient had no travel history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea incognito

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea incognito, a form of tinea corporis that is exacerbated by the inappropriate use of corticosteroids in the management of a cutaneous fungal infection.1 Furthermore, this patient’s case was consistent with tinea pseudoimbricata, a variant of tinea incognito. Tinea pseudoimbricata is characterized by striking concentric scaly rings that mimic tinea imbricata, a fungal infection caused by the dermatophyte Trichophyton concentricum, which is commonly found in tropical areas.2

A common infection is alteredby steroid use

Tinea corporis has a relatively high prevalence. Approximately 10% to 20% of the world population is affected by fungal skin infections.3

T rubrum is the most common cause of tinea corporis. Other causes include T tonsurans, T interdigitale, T violaceum, Microsporum canis, M gypseum, and M audouinii.

Tinea corporis can be acquired through direct contact with an infected person, animal, or fomite. It may also be acquired through autoinoculation from another area of the body containing a dermatophyte fungal infection. Tinea corporis lesions are usually pruritic, erythematous, annular plaques with overlying scale and central clearing.

How steroid use can change the picture. Treatment with corticosteroids is ineffective for fungal skin infections and causes immunosuppression, allowing the fungus to thrive. This patient had been treated with a topical steroid (clobetasol) for the abdominal lesion caused by tinea corporis, as well as an oral steroid (prednisone) for an asthma exacerbation. These steroid treatments caused the abdominal lesion to morph from the typical appearance of tinea corporis—classically an annular erythematous plaque with overlying scale and central clearing—to an erythematous plaque with striking concentric scaly rings.

Continue to: Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

The differential diagnosis for an annular skin lesion includes not only tinea corporis, but also superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, pityriasis rosea, granuloma annulare, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and nummular eczema.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, like tinea corporis, has scale. But the location of the scale sets the 2 apart. Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum lesions have a central trailing scale, whereas tinea corporis lesions have a peripheral leading scale.4

Pityriasis rosea forms multiple lesions in a “Christmas tree” pattern on the trunk, sometimes beginning with a single herald patch. Our patient’s single lesion with concentric scaly rings was inconsistent with the distribution and quality of the lesions in pityriasis rosea.4

Granuloma annulare lesions are smooth, nonscaly plaques that are most often seen on the dorsal hands and feet. The scaly manifestation of our patient’s lesion was not consistent with this diagnosis.4

SCLE lesions are typically photodistributed on sun-exposed skin (eg, the neck, upper trunk, or arms), whereas our patient’s lesion involved a sun-protected site.4

Continue to: Nummular eczema

Nummular eczema can be differentiated from tinea corporis by potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination. Nummular eczema is characterized by a negative KOH exam and response to topical corticosteroids.4

Performing a KOH examination, using the skin scrapings from the active border of a plaque, is useful on any lesion with potential fungal etiology. If the cause is indeed a dermatophyte infection, segmented fungal hyphae will be seen under light microscopy (FIGURE 2).1 If a KOH examination is not feasible, a skin scraping can be performed with a surgical scalpel blade and collected in a sterile urine cup for stain and culture at a qualified laboratory.

Topical and oral antifungal medications combat dermatophyte fungi

Treatments for cutaneous infections caused by dermatophyte fungi, such as tinea corporis, include topical and oral antifungals. The choice of agent depends on the extent of the disease.

Limited, localized disease can be treated topically with allylamines (terbinafine, naftifine) or imidazoles (clotrimazole). Other topical agents, such as butenafine, ciclopirox, and tolnaftate, also may be used.

Extensive disease, or tinea infection of vellus hairs, may require treatment with oral antifungal medications, such as the azoles (itraconazole, fluconazole), allylamines (terbinafine), or griseofulvin. Systemic therapy with oral antifungals has been associated with liver damage; therefore, oral therapy should not be used in patients with liver disease and liver enzymes should be monitored when appropriate.5 Nystatin is not effective in treating dermatophyte fungal infections.1

One complication of the inappropriate use of steroids on a dermatophyte infection is an increased risk of the fungus extending from the superficial skin into the hair follicles in the dermis, resulting in a condition known as Majocchi granuloma. Follicular infection is more severe and requires oral antifungal medication, such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, or griseofulvin.1

Our patient was treated with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks, due to the possibility of follicular infection. After the completion of 4 weeks of therapy, the patient’s cutaneous symptoms had resolved.

A 48-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented to Dermatology for evaluation of a 6-cm abdominal lesion that had been present for 5 weeks (FIGURE 1). The lesion was originally about the size of a quarter, but it started to enlarge after treatment of an asthma exacerbation with a 4-day course of prednisone. It continued to grow after another physician, likely presuming the lesion was a corticosteroid-responsive dermatosis (eg, nummular eczema, granuloma annulare, or erythema annulare centrifugum), prescribed a 2-week trial of clobetasol ointment. Physical examination revealed a mildly pruritic, 6-cm erythematous plaque with scaly, annular, concentric rings on the left lower abdomen. The patient had no travel history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea incognito

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea incognito, a form of tinea corporis that is exacerbated by the inappropriate use of corticosteroids in the management of a cutaneous fungal infection.1 Furthermore, this patient’s case was consistent with tinea pseudoimbricata, a variant of tinea incognito. Tinea pseudoimbricata is characterized by striking concentric scaly rings that mimic tinea imbricata, a fungal infection caused by the dermatophyte Trichophyton concentricum, which is commonly found in tropical areas.2

A common infection is alteredby steroid use

Tinea corporis has a relatively high prevalence. Approximately 10% to 20% of the world population is affected by fungal skin infections.3

T rubrum is the most common cause of tinea corporis. Other causes include T tonsurans, T interdigitale, T violaceum, Microsporum canis, M gypseum, and M audouinii.

Tinea corporis can be acquired through direct contact with an infected person, animal, or fomite. It may also be acquired through autoinoculation from another area of the body containing a dermatophyte fungal infection. Tinea corporis lesions are usually pruritic, erythematous, annular plaques with overlying scale and central clearing.

How steroid use can change the picture. Treatment with corticosteroids is ineffective for fungal skin infections and causes immunosuppression, allowing the fungus to thrive. This patient had been treated with a topical steroid (clobetasol) for the abdominal lesion caused by tinea corporis, as well as an oral steroid (prednisone) for an asthma exacerbation. These steroid treatments caused the abdominal lesion to morph from the typical appearance of tinea corporis—classically an annular erythematous plaque with overlying scale and central clearing—to an erythematous plaque with striking concentric scaly rings.

Continue to: Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

The differential diagnosis for an annular skin lesion includes not only tinea corporis, but also superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, pityriasis rosea, granuloma annulare, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and nummular eczema.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, like tinea corporis, has scale. But the location of the scale sets the 2 apart. Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum lesions have a central trailing scale, whereas tinea corporis lesions have a peripheral leading scale.4

Pityriasis rosea forms multiple lesions in a “Christmas tree” pattern on the trunk, sometimes beginning with a single herald patch. Our patient’s single lesion with concentric scaly rings was inconsistent with the distribution and quality of the lesions in pityriasis rosea.4

Granuloma annulare lesions are smooth, nonscaly plaques that are most often seen on the dorsal hands and feet. The scaly manifestation of our patient’s lesion was not consistent with this diagnosis.4

SCLE lesions are typically photodistributed on sun-exposed skin (eg, the neck, upper trunk, or arms), whereas our patient’s lesion involved a sun-protected site.4

Continue to: Nummular eczema

Nummular eczema can be differentiated from tinea corporis by potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination. Nummular eczema is characterized by a negative KOH exam and response to topical corticosteroids.4

Performing a KOH examination, using the skin scrapings from the active border of a plaque, is useful on any lesion with potential fungal etiology. If the cause is indeed a dermatophyte infection, segmented fungal hyphae will be seen under light microscopy (FIGURE 2).1 If a KOH examination is not feasible, a skin scraping can be performed with a surgical scalpel blade and collected in a sterile urine cup for stain and culture at a qualified laboratory.

Topical and oral antifungal medications combat dermatophyte fungi

Treatments for cutaneous infections caused by dermatophyte fungi, such as tinea corporis, include topical and oral antifungals. The choice of agent depends on the extent of the disease.

Limited, localized disease can be treated topically with allylamines (terbinafine, naftifine) or imidazoles (clotrimazole). Other topical agents, such as butenafine, ciclopirox, and tolnaftate, also may be used.

Extensive disease, or tinea infection of vellus hairs, may require treatment with oral antifungal medications, such as the azoles (itraconazole, fluconazole), allylamines (terbinafine), or griseofulvin. Systemic therapy with oral antifungals has been associated with liver damage; therefore, oral therapy should not be used in patients with liver disease and liver enzymes should be monitored when appropriate.5 Nystatin is not effective in treating dermatophyte fungal infections.1

One complication of the inappropriate use of steroids on a dermatophyte infection is an increased risk of the fungus extending from the superficial skin into the hair follicles in the dermis, resulting in a condition known as Majocchi granuloma. Follicular infection is more severe and requires oral antifungal medication, such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, or griseofulvin.1

Our patient was treated with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks, due to the possibility of follicular infection. After the completion of 4 weeks of therapy, the patient’s cutaneous symptoms had resolved.

1. Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated November 8, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections

2. Lederman E, Craft N, Burgin S. Tinea imbricata in adult. VisualDx. Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52399

3. El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD009992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009992.pub2

4. Unwala R. Approach to the patient with annular skin lesions. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated September 7, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-annular-skin-lesions

5. Wong V, High W, Burgin S. Tinea corporis in adult. VisualDx. Updated March 24, 2019. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52396#Therapy

1. Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated November 8, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections

2. Lederman E, Craft N, Burgin S. Tinea imbricata in adult. VisualDx. Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52399

3. El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD009992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009992.pub2

4. Unwala R. Approach to the patient with annular skin lesions. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated September 7, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-annular-skin-lesions

5. Wong V, High W, Burgin S. Tinea corporis in adult. VisualDx. Updated March 24, 2019. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52396#Therapy

Acral Papulovesicular Eruption in a Soldier Following Smallpox Vaccination

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, heightened concerns over bioterrorism and the potential use of smallpox as a biological weapon made smallpox vaccination a critical component of military readiness. Therefore, the US Military resumed its smallpox vaccination program in 2002 using the first-generation smallpox vaccine (Dryvax, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), a live vaccinia virus vaccine created in the late 19th century. This vaccine was developed by pooling vaccinia strains from the skin of infected cows1 and had previously been used during the worldwide vaccination campaign in the 1970s. Dryvax was associated with various cardiac and cutaneous complications, from benign hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

Due to concerns that the remaining supply of Dryvax was insufficient to vaccinate the US population in the case of a bioterrorism attack, investigators developed the second-generation smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000, Sanofi Pasteur Biologics Co) using advances in vaccine technology.2 ACAM2000 is a plaque-purified isolate of vaccinia virus propagated in cell culture, thereby reducing contaminants and lot-to-lot variation.1 Clinical trials demonstrated comparable immunogenicity and frequency of adverse events compared with Dryvax,2 and ACAM2000 replaced Dryvax in 2008. However, these trials focused on serious adverse events, such as cardiac complications and postvaccinal encephalitis, with less specific characterization and description of cutaneous eruptions.3

Since 2008, there have been few reports of cutaneous adverse reactions following vaccination with ACAM2000. Beachkofsky et al4 described 7 cases of papulovesicular eruptions and 1 case of generalized vaccinia. Freeman and Lenz5 described 4 cases of papulovesicular eruptions, and there has been 1 case of progressive vaccinia reported in a soldier with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia.6 Kramer7 described a patient with multiple vesiculopustular lesions secondary to autoinoculation. The distinct pruritic acral papulovesicular eruptions following ACAM2000 vaccination have occurred in healthy military service members at different locations since the introduction of ACAM2000. We describe an additional case of this unique cutaneous eruption, followed by a review of previously described cutaneous adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination.

Case Report

A 21-year-old female soldier who was otherwise healthy presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic papular eruption involving the upper and lower extremities of 1 week’s duration. The lesions first appeared 8 days after she received the ACAM2000 vaccine. She received no other concurrent vaccines, had no history of atopic dermatitis, and had no systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous indurated papules involving the dorsolateral hands and fingers, as well as the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Based on the clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis included lichen planus, verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, and smallpox vaccine reaction. Erythema multiforme was considered; however, the absence of palmoplantar involvement and typical targetoid lesions made this diagnosis less likely.

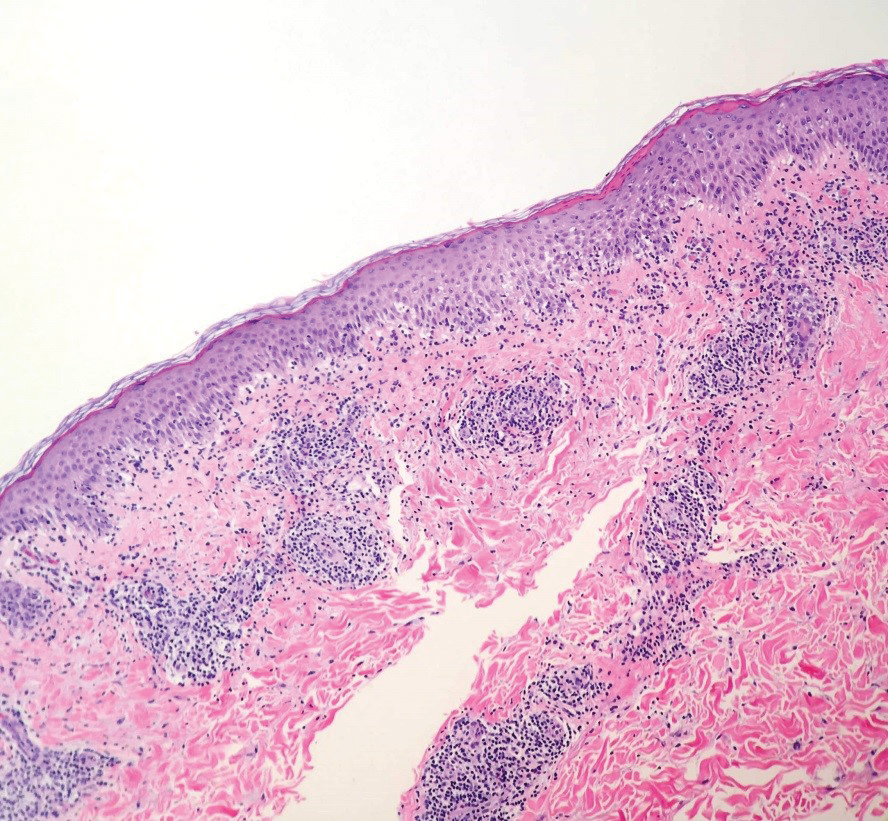

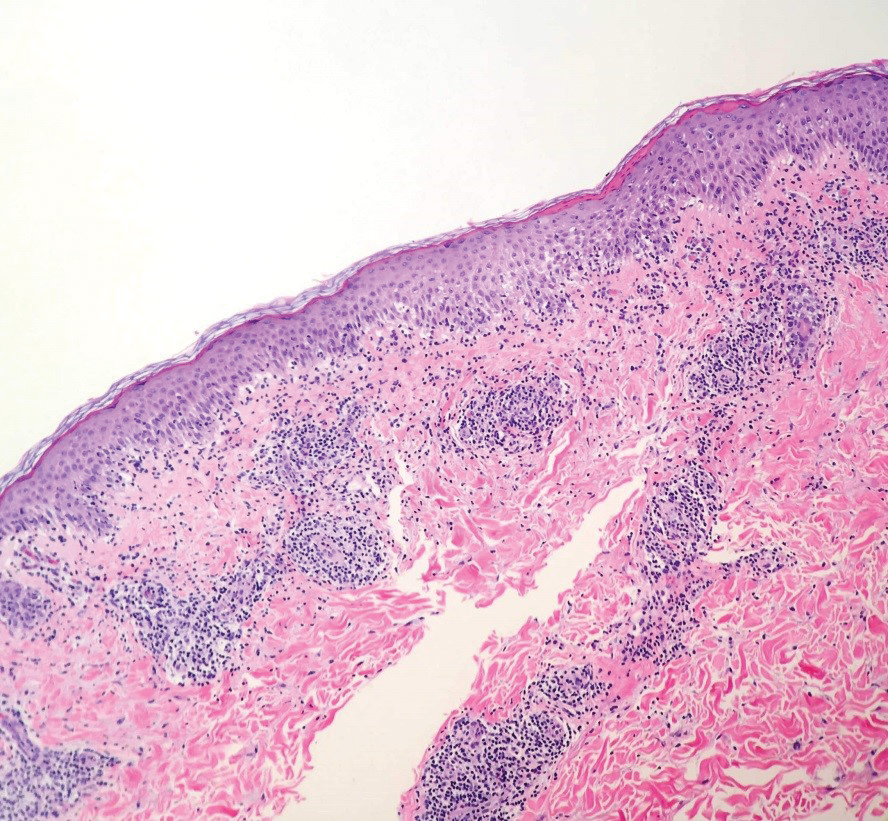

Biopsies of lesions on the arm and thigh were performed. Histologic findings revealed interface and spongiotic dermatitis with scattered necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 3). There was no evidence of viral cytopathic effects. Similar clinical and histologic findings have been reported in the literature as acral papulovesicular eruptions following smallpox vaccination or papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination.8 The presence of eosinophils was not conspicuous in the current case and was only a notable finding in 1 of 2 cases previously described by Gaertner et al.8 This may simply be due to an idiosyncratic drug reaction. Furthermore, in the cases described by Beachkofsky et al,4 there were essentially 2 histologic groups. The first group demonstrated a dermal hypersensitivity-type reaction, and the second group demonstrated a lymphocytic capillaritis.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with an acral papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination. Of note, the patient’s presentation was not consistent with other described smallpox vaccine reactions, which included eczema vaccinatum, autoinoculation, generalized vaccinia, and progressive vaccinia. The patient was treated supportively with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%, cool compresses, and oral diphenhydramine as needed for pruritus. The lesions notably improved within the first week of treatment.

Comment

Reported cases of acral papulovesicular eruption4-6 demonstrated an onset of cutaneous symptoms an average of 14 days following vaccination (range, 8–18 days postvaccination). Lesions were benign and self-limited in all cases, with resolution within an average of 25 days (range, 7–71 days). All patients were active-duty military adults with a mean age of 24 years. Supportive treatment varied from topical steroids and oral antihistamines to tapering oral prednisone doses. Of note, all previously reported cases of this reaction occurred in patients who also had received other concurrent or near-concurrent vaccines, including anthrax, hepatitis B, influenza, and typhoid. Our patient represents a unique case of a papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination with no history of concurrent vaccines.

Since the 1970s, smallpox vaccination has been associated with numerous cutaneous reactions, most of which have been reported with the first-generation Dryvax. Minor local reactions occurred in approximately 2% to 6% of vaccinees in clinical trials.9 These reactions included local edema involving the upper arm, satellite lesions within 2.5 cm of the vaccination site, local lymphadenopathy, intense inflammation or viral cellulitis surrounding the inoculation site, and viral lymphangitis tracking to axillary lymph nodes. In clinical trials, these reactions were self-limited and required only symptomatic treatment.9

Autoinoculation is another cutaneous reaction that can occur because Dryvax and ACAM2000 both contain live-attenuated replicating vaccinia virus. Accidental implantation may occur when the high titers of virus present at the vaccine site are subsequently transferred to other sites, especially abnormal mucosa or skin, resulting in an additional primary inoculation site.10

Eczema vaccinatum is a potentially life-threatening reaction that may occur in patients with disruptive skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis. These patients are at risk for massive confluent vaccinia infection of the skin.10 In patients with atopic dermatitis, the virus rapidly disseminates due to both skin barrier dysfunction and impaired immunomodulation, resulting in large confluent skin lesions and the potential for viremia, septic shock, and death.10,11 Mortality from eczema vaccinatum may be reduced by administration of vaccinia immune globulin.10

The vaccinia virus also may spread hematogenously in healthy individuals,10 resulting in a benign reaction called generalized vaccinia. These patients develop pustules on areas of the skin other than the vaccination site. Although typically benign and self-limited, Beachkofsky et al4 described a case of generalized vaccinia in a healthy 34-year-old man resulting in a rapidly progressive vesiculopustular eruption with associated fever and pancytopenia. The patient made a complete recovery over the course of the following month.4

Alternatively, progressive vaccinia is a severe complication of smallpox vaccination seen in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity. It also is known as vaccinia gangrenosum or vaccinia necrosum. These patients develop expanding ulcers due to exaggerated viral replication and cell-to-cell spread of the vaccinia virus.10,11 Hematogenous spread may result in viral implantation at distant sites of the body. This disease slowly progresses over weeks to months, and it often is resistant to treatment and fatal in patients with severe T-cell deficiency.10

Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct cutaneous adverse event following smallpox vaccination. Although further research is needed to discern the pathogenesis of this reaction, it is benign and self-limited, and patients have fully recovered with supportive care. In addition, a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine (Bavarian Nordic) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019.12,13 It is a nonreplicating attenuated viral vaccine that had fewer adverse events compared to ACAM2000 in clinical trials.13 To date, papulovesicular eruptions have not been reported following vaccination with the modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine; however, continued monitoring will help to further characterize any cutaneous reactions to this newer vaccine.

- Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79.

- Monath TP, Caldwell JR, Mundt W, et al. ACAM2000 clonal Vero cell culture vaccinia virus (New York City Board of Health strain)—a second-generation smallpox vaccine for biological defense. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:S31-S44.

- Thomas TN, Reef S, Neff L, et al. A review of the smallpox vaccine adverse events active surveillance system. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S212-S220.

- Beachkofsky TM, Carrizales SC, Bidinger JJ, et al. Adverse events following smallpox vaccination with ACAM2000 in a military population. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:656-661.

- Freeman R, Lenz B. Cutaneous reactions associated with ACAM2000 smallpox vaccination in a deploying U.S. Army unit. Mil Med. 2015;180:E152-E156.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progressive vaccinia in a military smallpox vaccinee—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:532-536.

- Kramer TR. Post–smallpox vaccination skin eruption in a marine. Mil Med. 2018;183:E649-E653.

- Gaertner EM, Groo S, Kim J. Papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination: report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1173-1175.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part I. background, vaccination technique, normal vaccination and revaccination, and expected normal reactions. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:241-250.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part II. adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:251-271.

- Bray M. Understanding smallpox vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1037-1039.

- Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia ankara smallpox vaccine (MVA-BN®) in 56-80-year-old subjects. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0157335.

- Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1897-1908.

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, heightened concerns over bioterrorism and the potential use of smallpox as a biological weapon made smallpox vaccination a critical component of military readiness. Therefore, the US Military resumed its smallpox vaccination program in 2002 using the first-generation smallpox vaccine (Dryvax, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), a live vaccinia virus vaccine created in the late 19th century. This vaccine was developed by pooling vaccinia strains from the skin of infected cows1 and had previously been used during the worldwide vaccination campaign in the 1970s. Dryvax was associated with various cardiac and cutaneous complications, from benign hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

Due to concerns that the remaining supply of Dryvax was insufficient to vaccinate the US population in the case of a bioterrorism attack, investigators developed the second-generation smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000, Sanofi Pasteur Biologics Co) using advances in vaccine technology.2 ACAM2000 is a plaque-purified isolate of vaccinia virus propagated in cell culture, thereby reducing contaminants and lot-to-lot variation.1 Clinical trials demonstrated comparable immunogenicity and frequency of adverse events compared with Dryvax,2 and ACAM2000 replaced Dryvax in 2008. However, these trials focused on serious adverse events, such as cardiac complications and postvaccinal encephalitis, with less specific characterization and description of cutaneous eruptions.3

Since 2008, there have been few reports of cutaneous adverse reactions following vaccination with ACAM2000. Beachkofsky et al4 described 7 cases of papulovesicular eruptions and 1 case of generalized vaccinia. Freeman and Lenz5 described 4 cases of papulovesicular eruptions, and there has been 1 case of progressive vaccinia reported in a soldier with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia.6 Kramer7 described a patient with multiple vesiculopustular lesions secondary to autoinoculation. The distinct pruritic acral papulovesicular eruptions following ACAM2000 vaccination have occurred in healthy military service members at different locations since the introduction of ACAM2000. We describe an additional case of this unique cutaneous eruption, followed by a review of previously described cutaneous adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination.

Case Report

A 21-year-old female soldier who was otherwise healthy presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic papular eruption involving the upper and lower extremities of 1 week’s duration. The lesions first appeared 8 days after she received the ACAM2000 vaccine. She received no other concurrent vaccines, had no history of atopic dermatitis, and had no systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous indurated papules involving the dorsolateral hands and fingers, as well as the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Based on the clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis included lichen planus, verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, and smallpox vaccine reaction. Erythema multiforme was considered; however, the absence of palmoplantar involvement and typical targetoid lesions made this diagnosis less likely.

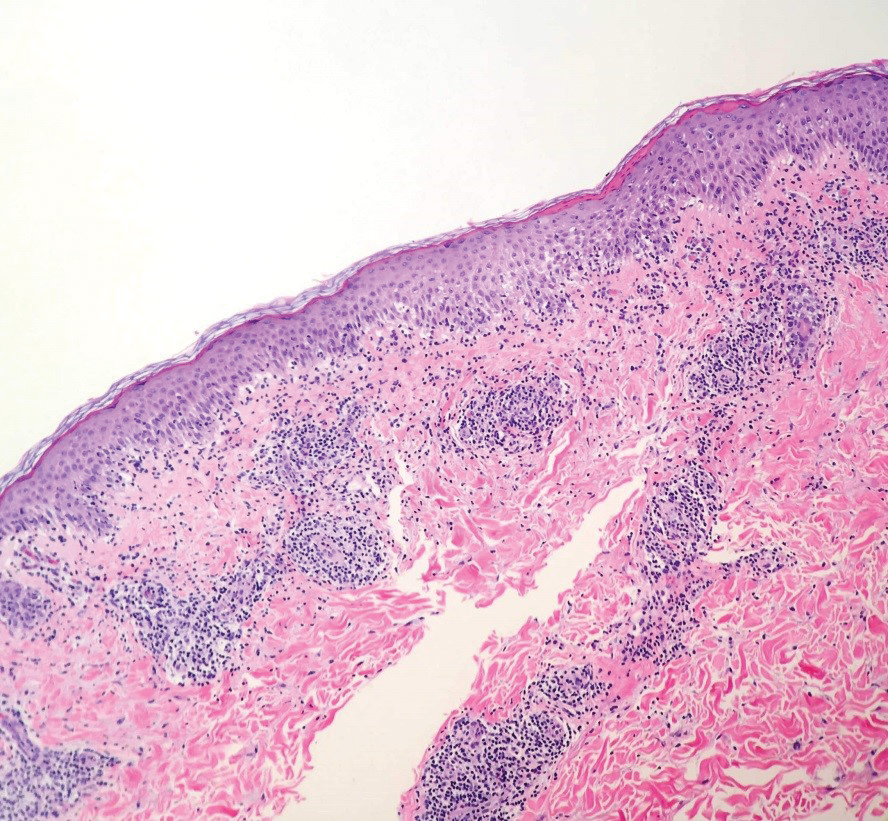

Biopsies of lesions on the arm and thigh were performed. Histologic findings revealed interface and spongiotic dermatitis with scattered necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 3). There was no evidence of viral cytopathic effects. Similar clinical and histologic findings have been reported in the literature as acral papulovesicular eruptions following smallpox vaccination or papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination.8 The presence of eosinophils was not conspicuous in the current case and was only a notable finding in 1 of 2 cases previously described by Gaertner et al.8 This may simply be due to an idiosyncratic drug reaction. Furthermore, in the cases described by Beachkofsky et al,4 there were essentially 2 histologic groups. The first group demonstrated a dermal hypersensitivity-type reaction, and the second group demonstrated a lymphocytic capillaritis.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with an acral papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination. Of note, the patient’s presentation was not consistent with other described smallpox vaccine reactions, which included eczema vaccinatum, autoinoculation, generalized vaccinia, and progressive vaccinia. The patient was treated supportively with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%, cool compresses, and oral diphenhydramine as needed for pruritus. The lesions notably improved within the first week of treatment.

Comment

Reported cases of acral papulovesicular eruption4-6 demonstrated an onset of cutaneous symptoms an average of 14 days following vaccination (range, 8–18 days postvaccination). Lesions were benign and self-limited in all cases, with resolution within an average of 25 days (range, 7–71 days). All patients were active-duty military adults with a mean age of 24 years. Supportive treatment varied from topical steroids and oral antihistamines to tapering oral prednisone doses. Of note, all previously reported cases of this reaction occurred in patients who also had received other concurrent or near-concurrent vaccines, including anthrax, hepatitis B, influenza, and typhoid. Our patient represents a unique case of a papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination with no history of concurrent vaccines.

Since the 1970s, smallpox vaccination has been associated with numerous cutaneous reactions, most of which have been reported with the first-generation Dryvax. Minor local reactions occurred in approximately 2% to 6% of vaccinees in clinical trials.9 These reactions included local edema involving the upper arm, satellite lesions within 2.5 cm of the vaccination site, local lymphadenopathy, intense inflammation or viral cellulitis surrounding the inoculation site, and viral lymphangitis tracking to axillary lymph nodes. In clinical trials, these reactions were self-limited and required only symptomatic treatment.9

Autoinoculation is another cutaneous reaction that can occur because Dryvax and ACAM2000 both contain live-attenuated replicating vaccinia virus. Accidental implantation may occur when the high titers of virus present at the vaccine site are subsequently transferred to other sites, especially abnormal mucosa or skin, resulting in an additional primary inoculation site.10

Eczema vaccinatum is a potentially life-threatening reaction that may occur in patients with disruptive skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis. These patients are at risk for massive confluent vaccinia infection of the skin.10 In patients with atopic dermatitis, the virus rapidly disseminates due to both skin barrier dysfunction and impaired immunomodulation, resulting in large confluent skin lesions and the potential for viremia, septic shock, and death.10,11 Mortality from eczema vaccinatum may be reduced by administration of vaccinia immune globulin.10

The vaccinia virus also may spread hematogenously in healthy individuals,10 resulting in a benign reaction called generalized vaccinia. These patients develop pustules on areas of the skin other than the vaccination site. Although typically benign and self-limited, Beachkofsky et al4 described a case of generalized vaccinia in a healthy 34-year-old man resulting in a rapidly progressive vesiculopustular eruption with associated fever and pancytopenia. The patient made a complete recovery over the course of the following month.4

Alternatively, progressive vaccinia is a severe complication of smallpox vaccination seen in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity. It also is known as vaccinia gangrenosum or vaccinia necrosum. These patients develop expanding ulcers due to exaggerated viral replication and cell-to-cell spread of the vaccinia virus.10,11 Hematogenous spread may result in viral implantation at distant sites of the body. This disease slowly progresses over weeks to months, and it often is resistant to treatment and fatal in patients with severe T-cell deficiency.10

Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct cutaneous adverse event following smallpox vaccination. Although further research is needed to discern the pathogenesis of this reaction, it is benign and self-limited, and patients have fully recovered with supportive care. In addition, a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine (Bavarian Nordic) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019.12,13 It is a nonreplicating attenuated viral vaccine that had fewer adverse events compared to ACAM2000 in clinical trials.13 To date, papulovesicular eruptions have not been reported following vaccination with the modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine; however, continued monitoring will help to further characterize any cutaneous reactions to this newer vaccine.

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, heightened concerns over bioterrorism and the potential use of smallpox as a biological weapon made smallpox vaccination a critical component of military readiness. Therefore, the US Military resumed its smallpox vaccination program in 2002 using the first-generation smallpox vaccine (Dryvax, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), a live vaccinia virus vaccine created in the late 19th century. This vaccine was developed by pooling vaccinia strains from the skin of infected cows1 and had previously been used during the worldwide vaccination campaign in the 1970s. Dryvax was associated with various cardiac and cutaneous complications, from benign hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

Due to concerns that the remaining supply of Dryvax was insufficient to vaccinate the US population in the case of a bioterrorism attack, investigators developed the second-generation smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000, Sanofi Pasteur Biologics Co) using advances in vaccine technology.2 ACAM2000 is a plaque-purified isolate of vaccinia virus propagated in cell culture, thereby reducing contaminants and lot-to-lot variation.1 Clinical trials demonstrated comparable immunogenicity and frequency of adverse events compared with Dryvax,2 and ACAM2000 replaced Dryvax in 2008. However, these trials focused on serious adverse events, such as cardiac complications and postvaccinal encephalitis, with less specific characterization and description of cutaneous eruptions.3

Since 2008, there have been few reports of cutaneous adverse reactions following vaccination with ACAM2000. Beachkofsky et al4 described 7 cases of papulovesicular eruptions and 1 case of generalized vaccinia. Freeman and Lenz5 described 4 cases of papulovesicular eruptions, and there has been 1 case of progressive vaccinia reported in a soldier with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia.6 Kramer7 described a patient with multiple vesiculopustular lesions secondary to autoinoculation. The distinct pruritic acral papulovesicular eruptions following ACAM2000 vaccination have occurred in healthy military service members at different locations since the introduction of ACAM2000. We describe an additional case of this unique cutaneous eruption, followed by a review of previously described cutaneous adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination.

Case Report

A 21-year-old female soldier who was otherwise healthy presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic papular eruption involving the upper and lower extremities of 1 week’s duration. The lesions first appeared 8 days after she received the ACAM2000 vaccine. She received no other concurrent vaccines, had no history of atopic dermatitis, and had no systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous indurated papules involving the dorsolateral hands and fingers, as well as the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Based on the clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis included lichen planus, verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, and smallpox vaccine reaction. Erythema multiforme was considered; however, the absence of palmoplantar involvement and typical targetoid lesions made this diagnosis less likely.

Biopsies of lesions on the arm and thigh were performed. Histologic findings revealed interface and spongiotic dermatitis with scattered necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 3). There was no evidence of viral cytopathic effects. Similar clinical and histologic findings have been reported in the literature as acral papulovesicular eruptions following smallpox vaccination or papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination.8 The presence of eosinophils was not conspicuous in the current case and was only a notable finding in 1 of 2 cases previously described by Gaertner et al.8 This may simply be due to an idiosyncratic drug reaction. Furthermore, in the cases described by Beachkofsky et al,4 there were essentially 2 histologic groups. The first group demonstrated a dermal hypersensitivity-type reaction, and the second group demonstrated a lymphocytic capillaritis.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with an acral papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination. Of note, the patient’s presentation was not consistent with other described smallpox vaccine reactions, which included eczema vaccinatum, autoinoculation, generalized vaccinia, and progressive vaccinia. The patient was treated supportively with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%, cool compresses, and oral diphenhydramine as needed for pruritus. The lesions notably improved within the first week of treatment.

Comment

Reported cases of acral papulovesicular eruption4-6 demonstrated an onset of cutaneous symptoms an average of 14 days following vaccination (range, 8–18 days postvaccination). Lesions were benign and self-limited in all cases, with resolution within an average of 25 days (range, 7–71 days). All patients were active-duty military adults with a mean age of 24 years. Supportive treatment varied from topical steroids and oral antihistamines to tapering oral prednisone doses. Of note, all previously reported cases of this reaction occurred in patients who also had received other concurrent or near-concurrent vaccines, including anthrax, hepatitis B, influenza, and typhoid. Our patient represents a unique case of a papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination with no history of concurrent vaccines.

Since the 1970s, smallpox vaccination has been associated with numerous cutaneous reactions, most of which have been reported with the first-generation Dryvax. Minor local reactions occurred in approximately 2% to 6% of vaccinees in clinical trials.9 These reactions included local edema involving the upper arm, satellite lesions within 2.5 cm of the vaccination site, local lymphadenopathy, intense inflammation or viral cellulitis surrounding the inoculation site, and viral lymphangitis tracking to axillary lymph nodes. In clinical trials, these reactions were self-limited and required only symptomatic treatment.9

Autoinoculation is another cutaneous reaction that can occur because Dryvax and ACAM2000 both contain live-attenuated replicating vaccinia virus. Accidental implantation may occur when the high titers of virus present at the vaccine site are subsequently transferred to other sites, especially abnormal mucosa or skin, resulting in an additional primary inoculation site.10

Eczema vaccinatum is a potentially life-threatening reaction that may occur in patients with disruptive skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis. These patients are at risk for massive confluent vaccinia infection of the skin.10 In patients with atopic dermatitis, the virus rapidly disseminates due to both skin barrier dysfunction and impaired immunomodulation, resulting in large confluent skin lesions and the potential for viremia, septic shock, and death.10,11 Mortality from eczema vaccinatum may be reduced by administration of vaccinia immune globulin.10

The vaccinia virus also may spread hematogenously in healthy individuals,10 resulting in a benign reaction called generalized vaccinia. These patients develop pustules on areas of the skin other than the vaccination site. Although typically benign and self-limited, Beachkofsky et al4 described a case of generalized vaccinia in a healthy 34-year-old man resulting in a rapidly progressive vesiculopustular eruption with associated fever and pancytopenia. The patient made a complete recovery over the course of the following month.4

Alternatively, progressive vaccinia is a severe complication of smallpox vaccination seen in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity. It also is known as vaccinia gangrenosum or vaccinia necrosum. These patients develop expanding ulcers due to exaggerated viral replication and cell-to-cell spread of the vaccinia virus.10,11 Hematogenous spread may result in viral implantation at distant sites of the body. This disease slowly progresses over weeks to months, and it often is resistant to treatment and fatal in patients with severe T-cell deficiency.10

Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct cutaneous adverse event following smallpox vaccination. Although further research is needed to discern the pathogenesis of this reaction, it is benign and self-limited, and patients have fully recovered with supportive care. In addition, a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine (Bavarian Nordic) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019.12,13 It is a nonreplicating attenuated viral vaccine that had fewer adverse events compared to ACAM2000 in clinical trials.13 To date, papulovesicular eruptions have not been reported following vaccination with the modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine; however, continued monitoring will help to further characterize any cutaneous reactions to this newer vaccine.

- Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79.

- Monath TP, Caldwell JR, Mundt W, et al. ACAM2000 clonal Vero cell culture vaccinia virus (New York City Board of Health strain)—a second-generation smallpox vaccine for biological defense. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:S31-S44.

- Thomas TN, Reef S, Neff L, et al. A review of the smallpox vaccine adverse events active surveillance system. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S212-S220.

- Beachkofsky TM, Carrizales SC, Bidinger JJ, et al. Adverse events following smallpox vaccination with ACAM2000 in a military population. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:656-661.

- Freeman R, Lenz B. Cutaneous reactions associated with ACAM2000 smallpox vaccination in a deploying U.S. Army unit. Mil Med. 2015;180:E152-E156.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progressive vaccinia in a military smallpox vaccinee—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:532-536.

- Kramer TR. Post–smallpox vaccination skin eruption in a marine. Mil Med. 2018;183:E649-E653.

- Gaertner EM, Groo S, Kim J. Papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination: report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1173-1175.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part I. background, vaccination technique, normal vaccination and revaccination, and expected normal reactions. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:241-250.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part II. adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:251-271.

- Bray M. Understanding smallpox vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1037-1039.

- Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia ankara smallpox vaccine (MVA-BN®) in 56-80-year-old subjects. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0157335.

- Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1897-1908.

- Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79.

- Monath TP, Caldwell JR, Mundt W, et al. ACAM2000 clonal Vero cell culture vaccinia virus (New York City Board of Health strain)—a second-generation smallpox vaccine for biological defense. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:S31-S44.

- Thomas TN, Reef S, Neff L, et al. A review of the smallpox vaccine adverse events active surveillance system. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S212-S220.

- Beachkofsky TM, Carrizales SC, Bidinger JJ, et al. Adverse events following smallpox vaccination with ACAM2000 in a military population. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:656-661.

- Freeman R, Lenz B. Cutaneous reactions associated with ACAM2000 smallpox vaccination in a deploying U.S. Army unit. Mil Med. 2015;180:E152-E156.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progressive vaccinia in a military smallpox vaccinee—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:532-536.

- Kramer TR. Post–smallpox vaccination skin eruption in a marine. Mil Med. 2018;183:E649-E653.

- Gaertner EM, Groo S, Kim J. Papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination: report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1173-1175.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part I. background, vaccination technique, normal vaccination and revaccination, and expected normal reactions. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:241-250.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part II. adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:251-271.

- Bray M. Understanding smallpox vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1037-1039.

- Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia ankara smallpox vaccine (MVA-BN®) in 56-80-year-old subjects. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0157335.

- Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1897-1908.

Practice Points

- There are several potential cutaneous adverse reactions associated with smallpox vaccination, ranging from benign self-limited hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

- Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct presentation that has been described in the US Military following vaccination with the second-generation live smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000).

Verrucous Carcinoma in a Wounded Military Amputee

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

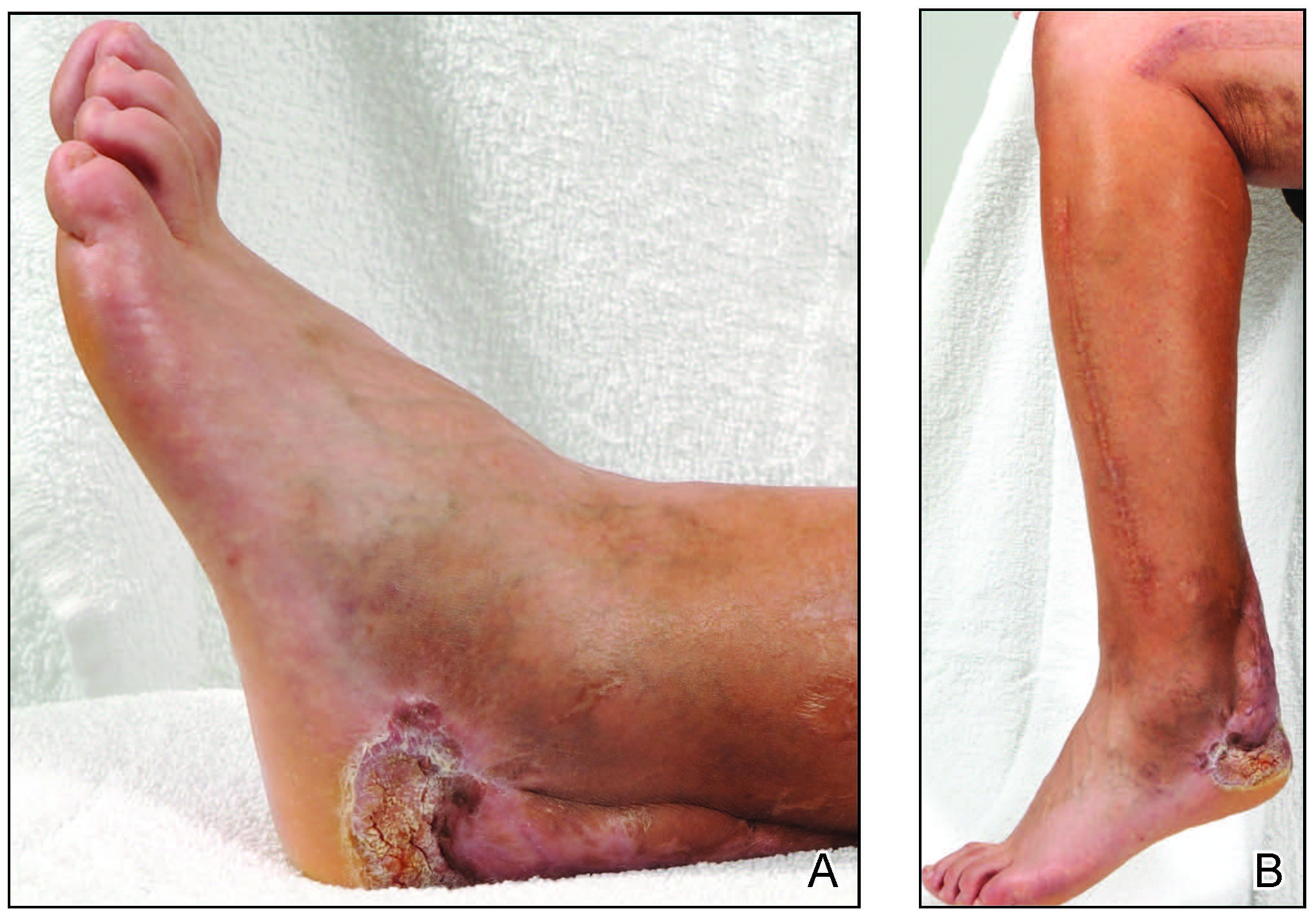

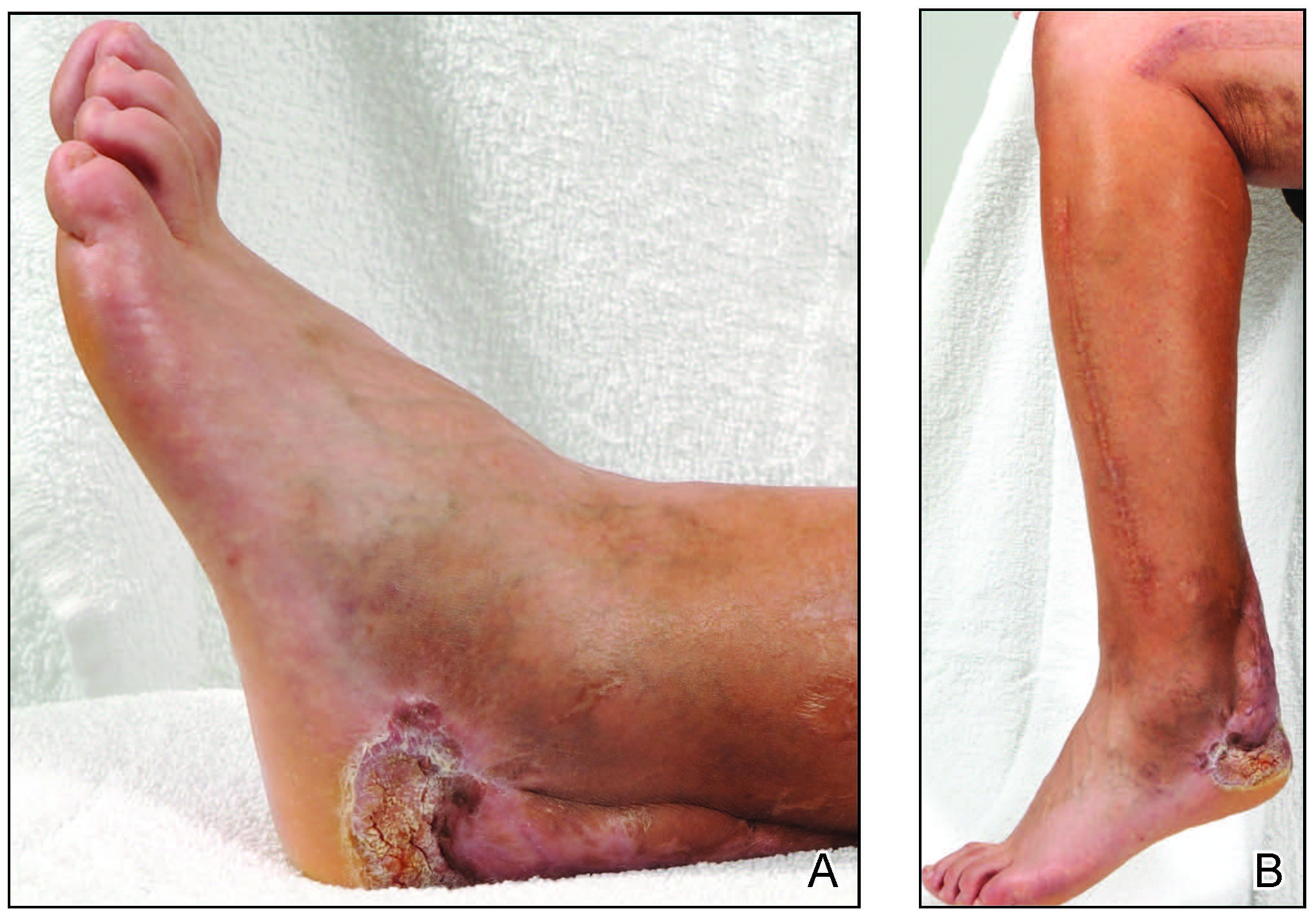

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

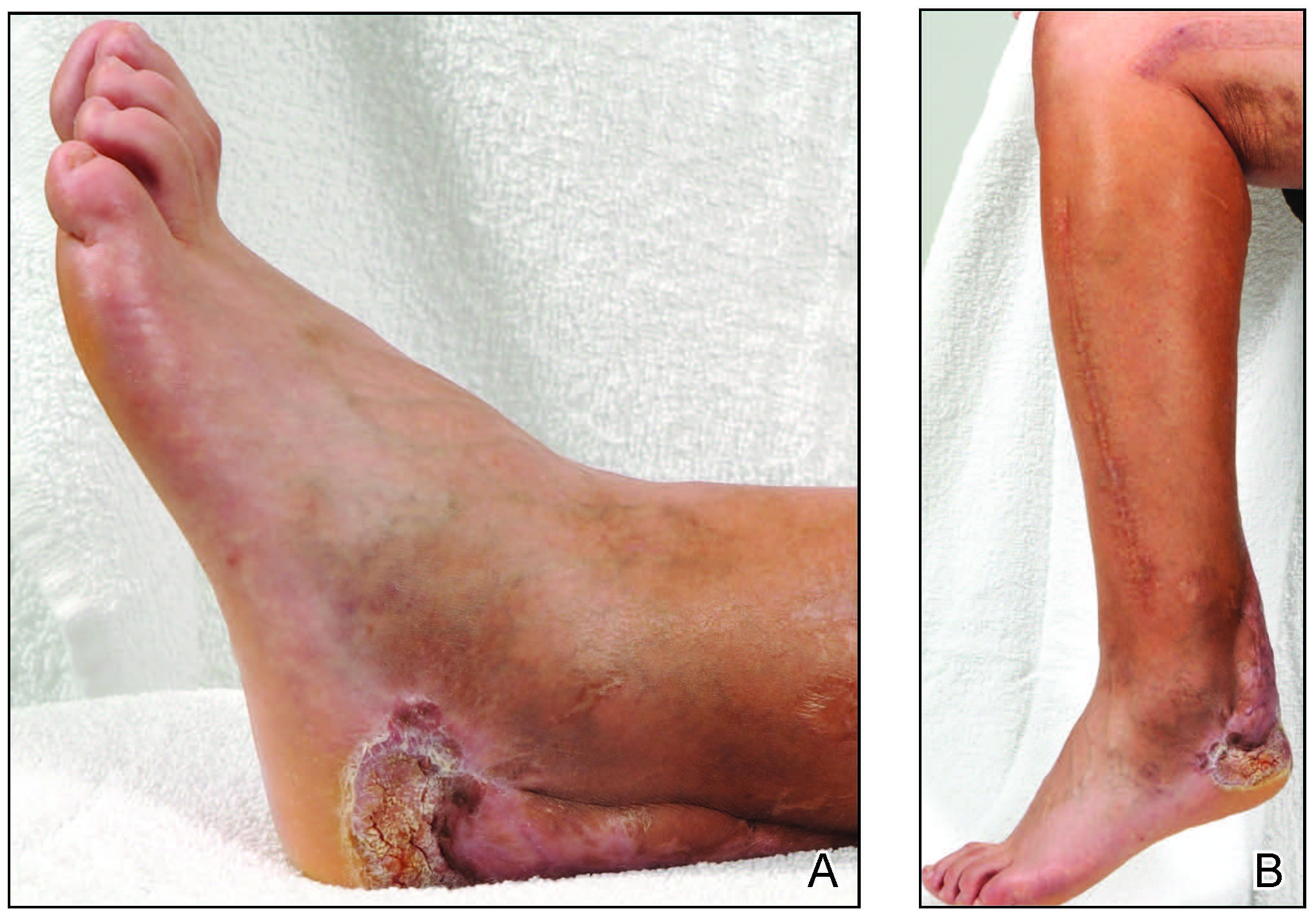

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

Practice Points

- Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma that commonly occurs in sites of inflammation or chronic irritation.

- Histologically, verrucous carcinoma can be mistaken for other entities including verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, often delaying the appropriate diagnosis and treatment.