User login

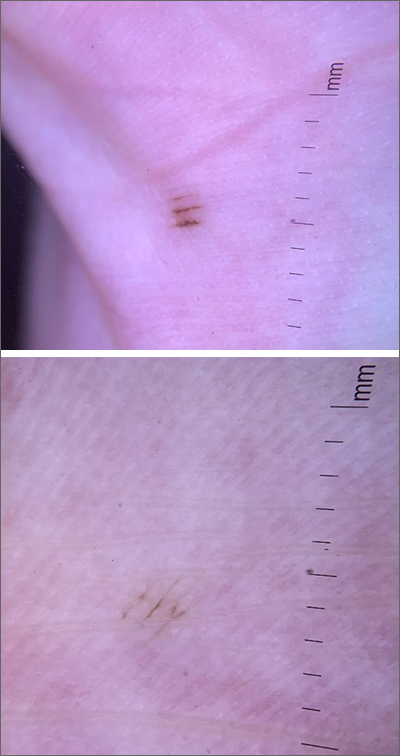

Asymptomatic hyperpigmented skin changes

The intertriginous findings, along with results from a punch biopsy showing resolving lichenoid inflammation with post-inflammatory pigmentary alteration, indicated a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus inversus (LPPI).

Insidious onset of usually asymptomatic, sometimes mildly pruritic, well-defined, hyperpigmented macules and patches with occasional Wickham striae of the intertriginous areas is characteristic of LPPI. It is a variant of lichen planus pigmentosus, which conversely occurs on sun-exposed areas. The etiology is unknown and there is no association with medications or sun exposure. Pathophysiology is thought to be chronic inflammation, mediated by T-lymphocyte cytotoxic activity against basal keratinocytes.1

At the time of this patient’s clinical presentation, the differential diagnoses for new onset hyperpigmentation included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, and erythema dyschromicum perstans. However, further tests were ordered for diagnostic clarification.

The clinical course of LPPI is variable. In some cases, there is complete resolution of lesions without treatment, while in other cases, lesions may last for years despite treatment and the condition may recur. Current management options include topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) and topical steroids. Response to these topical medications may be variable. The patient in this case was started on topical tacrolimus 0.1% twice daily, with follow-up in 3 months.

Text courtesy of Rachel Rose, BS, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP.

Barros HR, de Almeida JRP, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132599

The intertriginous findings, along with results from a punch biopsy showing resolving lichenoid inflammation with post-inflammatory pigmentary alteration, indicated a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus inversus (LPPI).

Insidious onset of usually asymptomatic, sometimes mildly pruritic, well-defined, hyperpigmented macules and patches with occasional Wickham striae of the intertriginous areas is characteristic of LPPI. It is a variant of lichen planus pigmentosus, which conversely occurs on sun-exposed areas. The etiology is unknown and there is no association with medications or sun exposure. Pathophysiology is thought to be chronic inflammation, mediated by T-lymphocyte cytotoxic activity against basal keratinocytes.1

At the time of this patient’s clinical presentation, the differential diagnoses for new onset hyperpigmentation included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, and erythema dyschromicum perstans. However, further tests were ordered for diagnostic clarification.

The clinical course of LPPI is variable. In some cases, there is complete resolution of lesions without treatment, while in other cases, lesions may last for years despite treatment and the condition may recur. Current management options include topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) and topical steroids. Response to these topical medications may be variable. The patient in this case was started on topical tacrolimus 0.1% twice daily, with follow-up in 3 months.

Text courtesy of Rachel Rose, BS, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP.

The intertriginous findings, along with results from a punch biopsy showing resolving lichenoid inflammation with post-inflammatory pigmentary alteration, indicated a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus inversus (LPPI).

Insidious onset of usually asymptomatic, sometimes mildly pruritic, well-defined, hyperpigmented macules and patches with occasional Wickham striae of the intertriginous areas is characteristic of LPPI. It is a variant of lichen planus pigmentosus, which conversely occurs on sun-exposed areas. The etiology is unknown and there is no association with medications or sun exposure. Pathophysiology is thought to be chronic inflammation, mediated by T-lymphocyte cytotoxic activity against basal keratinocytes.1

At the time of this patient’s clinical presentation, the differential diagnoses for new onset hyperpigmentation included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, and erythema dyschromicum perstans. However, further tests were ordered for diagnostic clarification.

The clinical course of LPPI is variable. In some cases, there is complete resolution of lesions without treatment, while in other cases, lesions may last for years despite treatment and the condition may recur. Current management options include topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) and topical steroids. Response to these topical medications may be variable. The patient in this case was started on topical tacrolimus 0.1% twice daily, with follow-up in 3 months.

Text courtesy of Rachel Rose, BS, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP.

Barros HR, de Almeida JRP, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132599

Barros HR, de Almeida JRP, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132599

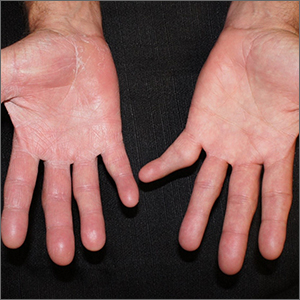

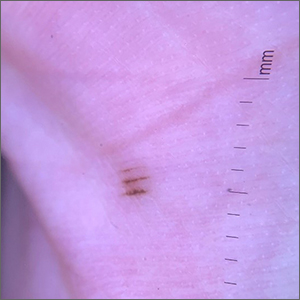

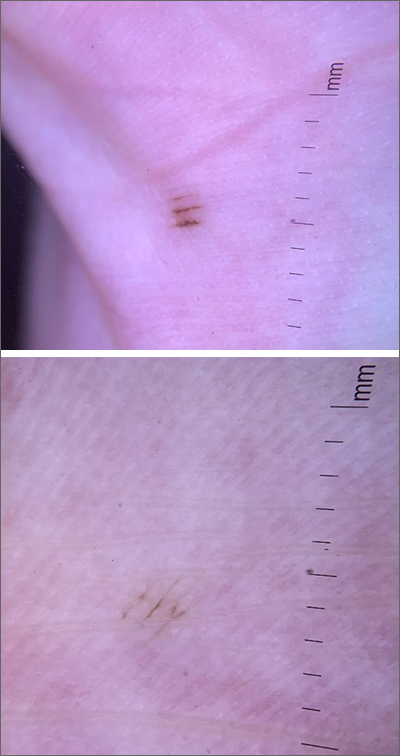

Scaly patches on hand and feet

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount of skin scrapings from the patient’s feet and hand confirmed a diagnosis of unilateral tinea manuum and bilateral tinea pedis—the so-called 2-foot, 1-hand syndrome. Additionally, nail clippings from the patient’s right hand confirmed onychomycosis.

Tinea is common and caused by various dermatophytes that are ubiquitous in soil. Often there is a history of atopic dermatitis or xerosis leading to skin barrier dysfunction. Immunosuppression and diabetes mellitus are also predisposing factors. Trichophyton rubrum is a commonly isolated cause.

On the hands, tinea may be challenging to distinguish from irritant dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis. A KOH prep test should be considered for any red, scaly rash, especially on the hands and feet. Curiously, the incidence of unilateral tinea manuum and bilateral tinea pedis occurs relatively frequently and can affect either the dominant or nondominant hand. The cause of this asymmetry is speculative.

Topical therapy with various antifungals—terbinafine, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, ciclopirox—can be effective, but challenging to apply to affected areas. For the treatment of nail disease, oral therapy with terbinafine or itraconazole is usually indicated (6 weeks for fingernails and 12 weeks for toenails). Terbinafine is generally tolerated very well for both 6- and 12-week courses. Some clinicians consider lab monitoring unnecessary because the risk of hepatic injury from terbinafine is uncertain; others consider it worthwhile to check liver function test results prior to initiation of terbinafine and after 6 weeks of therapy, with either a 6- or 12-week course.1

Since the patient in this case had skin and nail disease, oral therapy with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 6 weeks was prescribed. His skin cleared within 3 weeks and his nails cleared after 6 months. It is important to counsel patients with nail disease that treatment will end before they see a clinical improvement. Fingernails typically require 6 months to see clearance and toenails require 18 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Stolmeier DA, Stratman HB, McIntee TJ, et al. Utility of laboratory test result monitoring in patients taking oral terbinafine or griseofulvin for dermatophyte infections. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1409-1416. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3578

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount of skin scrapings from the patient’s feet and hand confirmed a diagnosis of unilateral tinea manuum and bilateral tinea pedis—the so-called 2-foot, 1-hand syndrome. Additionally, nail clippings from the patient’s right hand confirmed onychomycosis.

Tinea is common and caused by various dermatophytes that are ubiquitous in soil. Often there is a history of atopic dermatitis or xerosis leading to skin barrier dysfunction. Immunosuppression and diabetes mellitus are also predisposing factors. Trichophyton rubrum is a commonly isolated cause.

On the hands, tinea may be challenging to distinguish from irritant dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis. A KOH prep test should be considered for any red, scaly rash, especially on the hands and feet. Curiously, the incidence of unilateral tinea manuum and bilateral tinea pedis occurs relatively frequently and can affect either the dominant or nondominant hand. The cause of this asymmetry is speculative.

Topical therapy with various antifungals—terbinafine, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, ciclopirox—can be effective, but challenging to apply to affected areas. For the treatment of nail disease, oral therapy with terbinafine or itraconazole is usually indicated (6 weeks for fingernails and 12 weeks for toenails). Terbinafine is generally tolerated very well for both 6- and 12-week courses. Some clinicians consider lab monitoring unnecessary because the risk of hepatic injury from terbinafine is uncertain; others consider it worthwhile to check liver function test results prior to initiation of terbinafine and after 6 weeks of therapy, with either a 6- or 12-week course.1

Since the patient in this case had skin and nail disease, oral therapy with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 6 weeks was prescribed. His skin cleared within 3 weeks and his nails cleared after 6 months. It is important to counsel patients with nail disease that treatment will end before they see a clinical improvement. Fingernails typically require 6 months to see clearance and toenails require 18 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount of skin scrapings from the patient’s feet and hand confirmed a diagnosis of unilateral tinea manuum and bilateral tinea pedis—the so-called 2-foot, 1-hand syndrome. Additionally, nail clippings from the patient’s right hand confirmed onychomycosis.

Tinea is common and caused by various dermatophytes that are ubiquitous in soil. Often there is a history of atopic dermatitis or xerosis leading to skin barrier dysfunction. Immunosuppression and diabetes mellitus are also predisposing factors. Trichophyton rubrum is a commonly isolated cause.

On the hands, tinea may be challenging to distinguish from irritant dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis. A KOH prep test should be considered for any red, scaly rash, especially on the hands and feet. Curiously, the incidence of unilateral tinea manuum and bilateral tinea pedis occurs relatively frequently and can affect either the dominant or nondominant hand. The cause of this asymmetry is speculative.

Topical therapy with various antifungals—terbinafine, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, ciclopirox—can be effective, but challenging to apply to affected areas. For the treatment of nail disease, oral therapy with terbinafine or itraconazole is usually indicated (6 weeks for fingernails and 12 weeks for toenails). Terbinafine is generally tolerated very well for both 6- and 12-week courses. Some clinicians consider lab monitoring unnecessary because the risk of hepatic injury from terbinafine is uncertain; others consider it worthwhile to check liver function test results prior to initiation of terbinafine and after 6 weeks of therapy, with either a 6- or 12-week course.1

Since the patient in this case had skin and nail disease, oral therapy with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 6 weeks was prescribed. His skin cleared within 3 weeks and his nails cleared after 6 months. It is important to counsel patients with nail disease that treatment will end before they see a clinical improvement. Fingernails typically require 6 months to see clearance and toenails require 18 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Stolmeier DA, Stratman HB, McIntee TJ, et al. Utility of laboratory test result monitoring in patients taking oral terbinafine or griseofulvin for dermatophyte infections. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1409-1416. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3578

1. Stolmeier DA, Stratman HB, McIntee TJ, et al. Utility of laboratory test result monitoring in patients taking oral terbinafine or griseofulvin for dermatophyte infections. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1409-1416. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3578

Painful ingrown nail

Paronychia, or an ingrown nail, is caused by the introduction of bacteria into the nail fold, which can cause cellulitis and/or abscess formation. Typically, a single nail is involved, although multiple nails may be affected in rare, chemotherapy-induced cases. Generally, nail grooming behaviors, abnormal or scarred nail matrix architecture, nail biting, and wet work are the causes of acute or chronic disease.1

Conservative options are a reasonable first choice when there is no abscess. These include soaks 2 to 3 times daily for 15 to 20 minutes in hot water or water treated with an antiseptic, such as chlorhexidine. Topical or oral antibiotics aimed at suspected organisms may be helpful. Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is a common isolate. Psuedomonas is characteristic in cases involving trauma to the hand and frequent workplace water exposure, as can happen in foodservice, farming, and marine industries.

When an abscess has formed (as in this case), or when conservative treatments fail, incision and drainage or partial nail avulsion can be curative and successful with, or without, antibiotics. Patients with recurrent paronychia in the same location may benefit from partial nail avulsion with partial matrix removal. This can be done surgically or with phenol.

In this case, the patient underwent lateral partial nail avulsion, which also served as an incision and drainage. She was not given antibiotics and her nail regrew within 6 months; there was no recurrence. She was counseled not to cut the nail plate too aggressively.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, et al. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:339-346.

Paronychia, or an ingrown nail, is caused by the introduction of bacteria into the nail fold, which can cause cellulitis and/or abscess formation. Typically, a single nail is involved, although multiple nails may be affected in rare, chemotherapy-induced cases. Generally, nail grooming behaviors, abnormal or scarred nail matrix architecture, nail biting, and wet work are the causes of acute or chronic disease.1

Conservative options are a reasonable first choice when there is no abscess. These include soaks 2 to 3 times daily for 15 to 20 minutes in hot water or water treated with an antiseptic, such as chlorhexidine. Topical or oral antibiotics aimed at suspected organisms may be helpful. Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is a common isolate. Psuedomonas is characteristic in cases involving trauma to the hand and frequent workplace water exposure, as can happen in foodservice, farming, and marine industries.

When an abscess has formed (as in this case), or when conservative treatments fail, incision and drainage or partial nail avulsion can be curative and successful with, or without, antibiotics. Patients with recurrent paronychia in the same location may benefit from partial nail avulsion with partial matrix removal. This can be done surgically or with phenol.

In this case, the patient underwent lateral partial nail avulsion, which also served as an incision and drainage. She was not given antibiotics and her nail regrew within 6 months; there was no recurrence. She was counseled not to cut the nail plate too aggressively.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Paronychia, or an ingrown nail, is caused by the introduction of bacteria into the nail fold, which can cause cellulitis and/or abscess formation. Typically, a single nail is involved, although multiple nails may be affected in rare, chemotherapy-induced cases. Generally, nail grooming behaviors, abnormal or scarred nail matrix architecture, nail biting, and wet work are the causes of acute or chronic disease.1

Conservative options are a reasonable first choice when there is no abscess. These include soaks 2 to 3 times daily for 15 to 20 minutes in hot water or water treated with an antiseptic, such as chlorhexidine. Topical or oral antibiotics aimed at suspected organisms may be helpful. Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is a common isolate. Psuedomonas is characteristic in cases involving trauma to the hand and frequent workplace water exposure, as can happen in foodservice, farming, and marine industries.

When an abscess has formed (as in this case), or when conservative treatments fail, incision and drainage or partial nail avulsion can be curative and successful with, or without, antibiotics. Patients with recurrent paronychia in the same location may benefit from partial nail avulsion with partial matrix removal. This can be done surgically or with phenol.

In this case, the patient underwent lateral partial nail avulsion, which also served as an incision and drainage. She was not given antibiotics and her nail regrew within 6 months; there was no recurrence. She was counseled not to cut the nail plate too aggressively.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, et al. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:339-346.

Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, et al. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:339-346.

Ptosis after motorcycle accident

A 45-year-old woman visited the clinic 6 weeks after having a stroke while on her motorcycle, which resulted in a crash. She had not been wearing a helmet and was uncertain if she had sustained a head injury. She said that during the hospital stay following the accident, she was diagnosed as hypertensive; she denied any other significant prior medical history.

Following the crash, she said she’d been experiencing weakness in her right arm and leg and had been unable to open her right eye. When her right eye was opened manually, she said she had double vision and sensitivity to light.

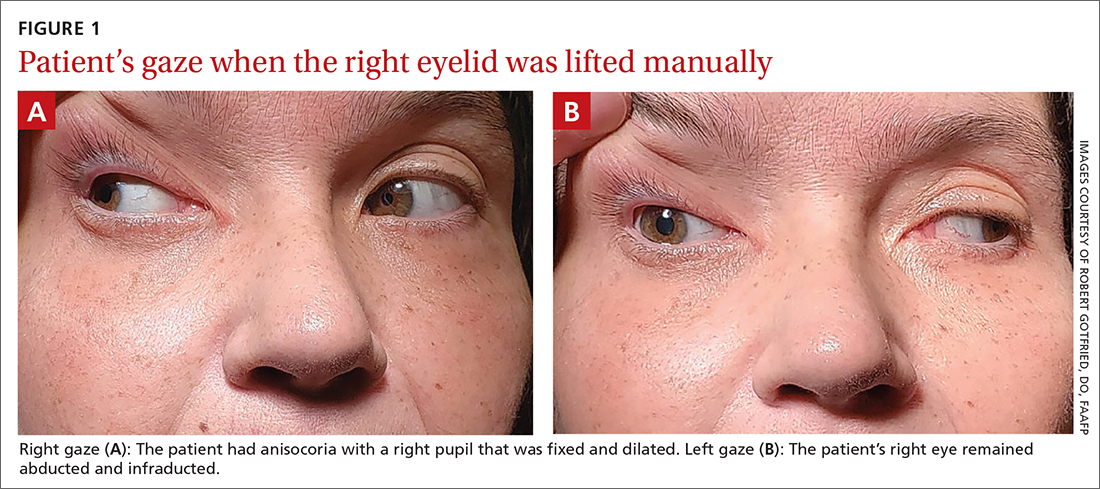

On exam, the patient had exotropia with hypotropia of her right eye. Additionally, she had anisocoria with an enlarged, nonreactive right pupil (FIGURE 1A). She was unable to adduct, supraduct, or infraduct her right eye (FIGURE 1B). Her cranial nerves were otherwise intact. On manual strength testing, she had 4/5 strength of both her right upper and lower extremities.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Third (oculomotor) nerve palsy

This patient had a complete third nerve palsy (TNP). This is defined as palsy involving all of the muscles innervated by the oculomotor nerve, with pupillary involvement.1 The oculomotor nerve supplies motor innervation to the levator palpebrae superioris, superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior rectus, and inferior oblique muscles and parasympathetic innervation to the pupillary constrictor and ciliary muscles.2 As a result, patients present with exotropia and hypotropia on exam with anisocoria. Diplopia, ptosis, and an enlarged pupil are classic symptoms of TNP.2

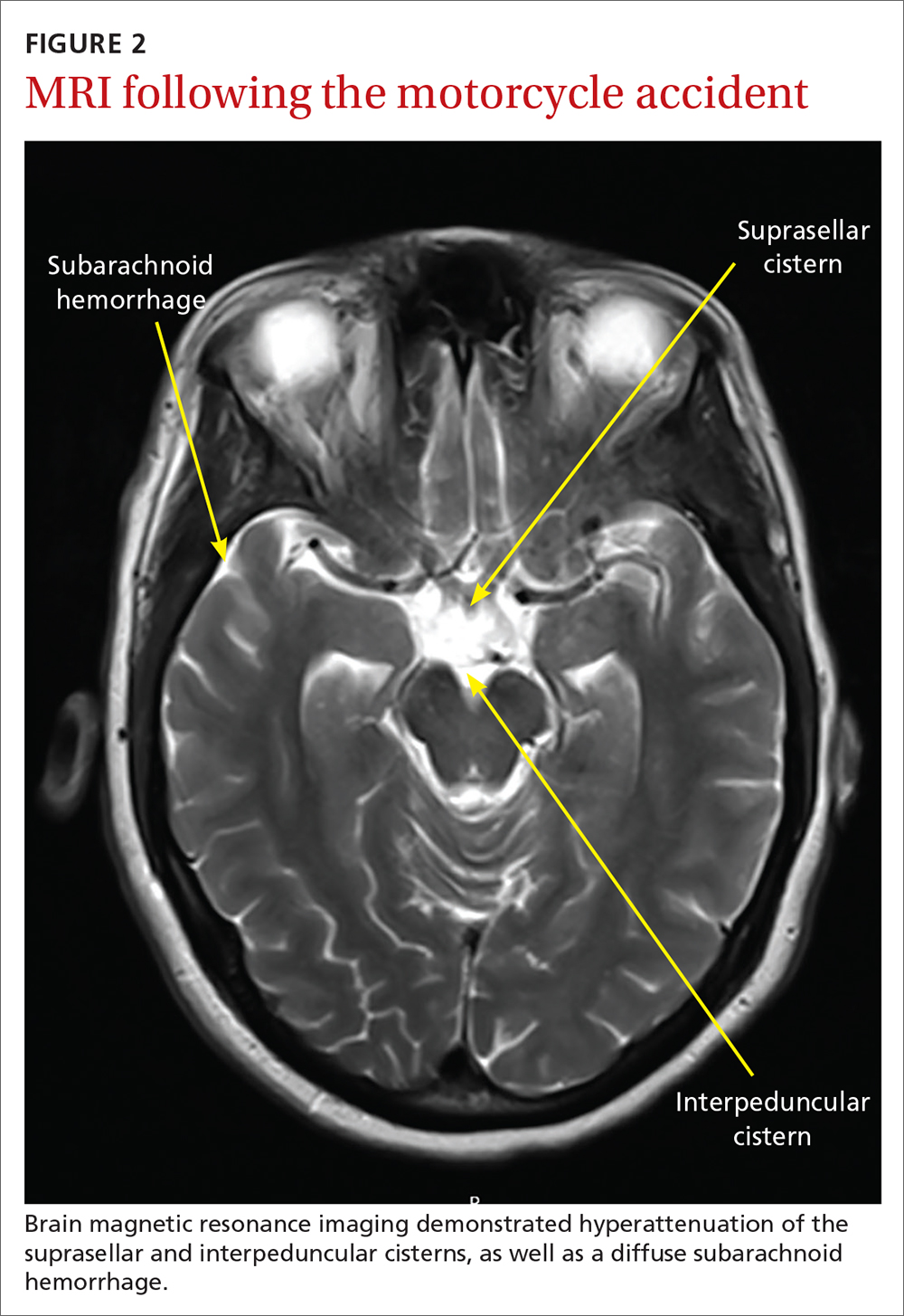

Computed tomography (CT) of the brain performed immediately after this patient’s accident demonstrated a 15-mm hemorrhage within the left basal ganglia with mild associated edema, and a small focus of hyperattenuation within the right aspect of the suprasellar cistern. There was no evidence of skull fracture. CT angiography (CTA) of the brain showed no evidence of aneurysm.

Several days later, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain confirmed prior CT findings and revealed hemorrhagic contusions along the anterior and medial left temporal lobe. Additionally, the MRI showed subtle subdural hemorrhages along the midline falx and right parietal region, as well as diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage around both hemispheres, the interpeduncular cistern, and the suprasellar cistern (FIGURE 2). The basal ganglia hemorrhage was believed to have been a result of uncontrolled hypertension. The hemorrhage was responsible for her right-sided weakness and was the presumed cause of the accident. The other findings were due to head trauma. Her TNP was most likely caused by both compression and irritation of the right oculomotor nerve.

An uncommon occurrence

A population-based study identified the annual incidence of TNP to be 4 per 100,000.1 The mean age of onset was 42 years. The incidence in patients older than 60 years was greater than the incidence in those younger than 60.2 Isolated TNP occurred in approximately 40% of cases.2

Complete TNP is typically indicative of compression of the ipsilateral third nerve.2 The most common region for third nerve injury is the subarachnoid space, where the oculomotor nerve is vulnerable to compression, often by an aneurysm arising from the junction of the internal carotid and posterior communicating arteries.3

Continue to: Incomplete TNP

Incomplete TNP is often microvascular in origin and requires evaluation for diabetes and hypertension. Microvascular TNP is frequently painful but usually self-resolves after 2 to 4 months.2 Giant cell arteritis may also cause an isolated, painful TNP.2

A varied differential diagnosis and a TNP link to COVID-19

The differential diagnosis for TNP includes the following:

Orbital apex injury is usually seen after high-energy craniofacial trauma.4 Orbital apex fractures present with different signs and symptoms, depending on the degree of injury to neural and vascular structures. Various syndromes come into play, the most common being superior orbital fissure syndrome, which is characterized by dysfunction of cranial nerves III, IV, V, and VI.4 Features include ophthalmoplegia, upper eyelid ptosis, a nonreactive dilated pupil, anesthesia over the ipsilateral forehead, loss of corneal reflex, orbital pain, and proptosis.4

In patients with suspected orbital apex fractures, it’s important to assess for the presence of an optic neuropathy, an evolving orbital compartment syndrome, or a ruptured globe, because these 3 things may demand acute intervention.4

Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) is a mitochondrial disorder characterized by a slow, progressive paralysis of the extraocular muscles.5 Patients usually experience bilateral, symmetrical, progressive ptosis, followed by ophthalmoparesis months to years later. Ciliary and iris muscles are not involved. CPEO often occurs with other systemic features of mitochondrial dysfunction that can cause significant morbidity and mortality.5

Continue to: Graves ophthalmopathy

Graves ophthalmopathy arises from soft-tissue enlargement in the orbit, leading to increased pressure within the bony cavity.6 Approximately 40% of patients with Graves ophthalmopathy present with restrictive extraocular myopathy; however > 90% have eyelid retraction, as opposed to ptosis.7

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute, demyelinating immune-mediated polyneuropathy involving the spinal roots, peripheral nerves, and often the cranial nerves.8 The Miller Fisher variant of GBS is characterized by bilateral ophthalmoparesis, areflexia, and ataxia.8 At the early stage of illness, the presentation may be similar to TNP.8 Brain imaging is normal in patients with GBS; the diagnosis is established via characteristic electromyography and cerebrospinal fluid findings.8

Myasthenia gravis often manifests with variable ptosis associated with diplopia.9 Symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral. The ice-pack test has been identified as a simple, preliminary test for ocular myasthenia. The test involves the application of an ice-pack over the lids for 5 minutes. A 50% reduction in at least 1 component of ocular deviation is considered a positive response.10 Its specificity reportedly reaches 100%, with a sensitivity of 80%.10

COVID-19 infection may also include neurologic manifestations. There are an increasing number of case reports of central nervous system abnormalities including TNP.11,12

Trauma, tumors, or an aneurysm could be at work in TNP

TNP associated with trauma usually develops secondary to compression from an expanding hematoma, although it may also be a result of irritation of the nerve from blood in the subarachnoid space.13 Estimates of the incidence of TNP due to trauma range from 12% to 26% of cases.1,14 Vehicle-related injury is the most frequent cause of trauma-related TNP.14

Continue to: Pituitary tumors

Pituitary tumors most commonly involve the oculomotor nerve; 14% to 30% of pituitary tumors lead to TNP.13 Pituitary apoplexy secondary to infarction or hemorrhage is often associated with visual field defects and TNP.13

An underlying aneurysm manifests in a minority (10% to 15%) of patients presenting with TNP.3

Imaging is key to getting at the cause of TNP

The evaluation of patients presenting with acute TNP should be focused first on detecting an aneurysmal compressive lesion.3 CTA is the imaging modality of choice.

Once an aneurysm has been ruled out, the work-up should include a lumbar puncture and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Older patients should be assessed for conditions such as hypertension or diabetes that put them at risk for microvascular disease.3 If microvascular TNP is unlikely, MRI with MR angiography is recommended to exclude other potential etiologies of TNP.3 If the patient is younger than 50 years of age, consider potential infectious and inflammatory etiologies (eg, giant cell arteritis).3

Treatment options are varied

The treatment of patients with TNP is specific to the disease state. For those patients with vascular risk factors and a presumptive diagnosis of microvascular TNP, it is reasonable to observe the patient for 2 to 3 months.3 Antiplatelet therapy is usually initiated. Patching 1 eye is useful in alleviating diplopia, particularly in the short term. In most cases, deficits related to TNP resolve over weeks to months. Deficits that persist beyond 6 months may require surgical intervention.

Continue to: "The tip of the iceberg"

TNP: “The tip of the iceberg”

TNP may signal a neurologic emergency, such as an aneurysm, or other conditions such as pituitary disease or giant cell arteritis. Any patient presenting with acute onset of TNP should undergo a noninvasive neuroimaging study.3

Our patient was treated for hypertension; however, she was lost to follow-up.

1. Fang C, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, et al. Incidence and etiologies of acquired third nerve palsy using a population-based method. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:23-28. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.4456

2. Bruce BB, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Third nerve palsies. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:257-268. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979681

3. Margolin E, Freund P. A review of third nerve palsies. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2019;59:99-112. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000279

4. Linnau KF, Hallam DK, Lomoschitz FM, et al. Orbital apex injury: trauma at the junction between the face and the cranium. Eur J Radiol. 2003;48:5-16. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(03)00203-1

5. McClelland C, Manousakis G, Lee MS. Progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:53. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0652-7

6. Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726-738. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905750

7. Subetki I, Soewond P, Soebardi S, et al. Practical guidelines management of graves ophthalmopathy. Acta Med Indones. 2019;51:364-371.

8. Wijdicks EF, Klein CJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:467-479. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.002

9. Beloor Suresh A, Asuncion RMD. Myasthenia Gravis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Accessed April 26, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559331/

10. Chatzistefanou KI, Kouris T, Iliakis E, et al. The ice pack test in the differential diagnosis of myasthenic diplopia. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2236-2243. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.039

11. Pascual-Prieto J, Narváez-Palazón C, Porta-Etessam J, et al. COVID-19 epidemic: should ophthalmologists be aware of oculomotor paresis? Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2020;95:361-362. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2020.05.002

12. Collantes MEV, Espiritu AI, Sy MCC, et al. Neurological manifestations in COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48:66-76. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2020.146

13. Raza HK, Chen H, Chansysouphanthong T, et al. The aetiologies of the unilateral oculomotor nerve palsy: a review of the literature. Somatosens Mot Res. 2018;35:229-239. doi :10.1080/08990220.2018.1547697

14. Keane J. Third nerve palsy: analysis of 1400 personally-examined inpatients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:662-670. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100010866

A 45-year-old woman visited the clinic 6 weeks after having a stroke while on her motorcycle, which resulted in a crash. She had not been wearing a helmet and was uncertain if she had sustained a head injury. She said that during the hospital stay following the accident, she was diagnosed as hypertensive; she denied any other significant prior medical history.

Following the crash, she said she’d been experiencing weakness in her right arm and leg and had been unable to open her right eye. When her right eye was opened manually, she said she had double vision and sensitivity to light.

On exam, the patient had exotropia with hypotropia of her right eye. Additionally, she had anisocoria with an enlarged, nonreactive right pupil (FIGURE 1A). She was unable to adduct, supraduct, or infraduct her right eye (FIGURE 1B). Her cranial nerves were otherwise intact. On manual strength testing, she had 4/5 strength of both her right upper and lower extremities.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Third (oculomotor) nerve palsy

This patient had a complete third nerve palsy (TNP). This is defined as palsy involving all of the muscles innervated by the oculomotor nerve, with pupillary involvement.1 The oculomotor nerve supplies motor innervation to the levator palpebrae superioris, superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior rectus, and inferior oblique muscles and parasympathetic innervation to the pupillary constrictor and ciliary muscles.2 As a result, patients present with exotropia and hypotropia on exam with anisocoria. Diplopia, ptosis, and an enlarged pupil are classic symptoms of TNP.2

Computed tomography (CT) of the brain performed immediately after this patient’s accident demonstrated a 15-mm hemorrhage within the left basal ganglia with mild associated edema, and a small focus of hyperattenuation within the right aspect of the suprasellar cistern. There was no evidence of skull fracture. CT angiography (CTA) of the brain showed no evidence of aneurysm.

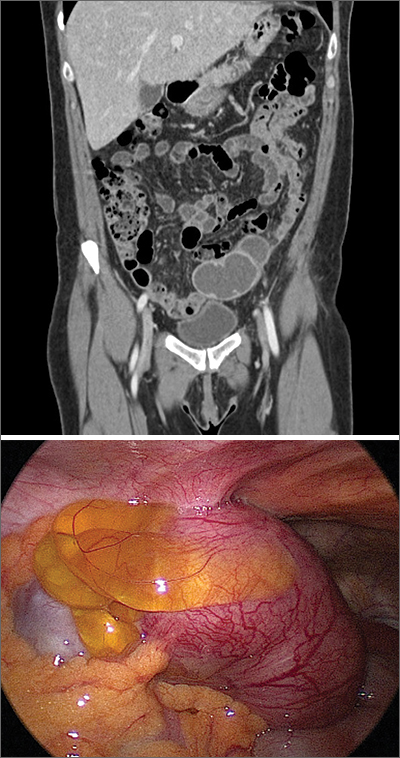

Several days later, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain confirmed prior CT findings and revealed hemorrhagic contusions along the anterior and medial left temporal lobe. Additionally, the MRI showed subtle subdural hemorrhages along the midline falx and right parietal region, as well as diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage around both hemispheres, the interpeduncular cistern, and the suprasellar cistern (FIGURE 2). The basal ganglia hemorrhage was believed to have been a result of uncontrolled hypertension. The hemorrhage was responsible for her right-sided weakness and was the presumed cause of the accident. The other findings were due to head trauma. Her TNP was most likely caused by both compression and irritation of the right oculomotor nerve.

An uncommon occurrence

A population-based study identified the annual incidence of TNP to be 4 per 100,000.1 The mean age of onset was 42 years. The incidence in patients older than 60 years was greater than the incidence in those younger than 60.2 Isolated TNP occurred in approximately 40% of cases.2

Complete TNP is typically indicative of compression of the ipsilateral third nerve.2 The most common region for third nerve injury is the subarachnoid space, where the oculomotor nerve is vulnerable to compression, often by an aneurysm arising from the junction of the internal carotid and posterior communicating arteries.3

Continue to: Incomplete TNP

Incomplete TNP is often microvascular in origin and requires evaluation for diabetes and hypertension. Microvascular TNP is frequently painful but usually self-resolves after 2 to 4 months.2 Giant cell arteritis may also cause an isolated, painful TNP.2

A varied differential diagnosis and a TNP link to COVID-19

The differential diagnosis for TNP includes the following:

Orbital apex injury is usually seen after high-energy craniofacial trauma.4 Orbital apex fractures present with different signs and symptoms, depending on the degree of injury to neural and vascular structures. Various syndromes come into play, the most common being superior orbital fissure syndrome, which is characterized by dysfunction of cranial nerves III, IV, V, and VI.4 Features include ophthalmoplegia, upper eyelid ptosis, a nonreactive dilated pupil, anesthesia over the ipsilateral forehead, loss of corneal reflex, orbital pain, and proptosis.4

In patients with suspected orbital apex fractures, it’s important to assess for the presence of an optic neuropathy, an evolving orbital compartment syndrome, or a ruptured globe, because these 3 things may demand acute intervention.4

Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) is a mitochondrial disorder characterized by a slow, progressive paralysis of the extraocular muscles.5 Patients usually experience bilateral, symmetrical, progressive ptosis, followed by ophthalmoparesis months to years later. Ciliary and iris muscles are not involved. CPEO often occurs with other systemic features of mitochondrial dysfunction that can cause significant morbidity and mortality.5

Continue to: Graves ophthalmopathy

Graves ophthalmopathy arises from soft-tissue enlargement in the orbit, leading to increased pressure within the bony cavity.6 Approximately 40% of patients with Graves ophthalmopathy present with restrictive extraocular myopathy; however > 90% have eyelid retraction, as opposed to ptosis.7

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute, demyelinating immune-mediated polyneuropathy involving the spinal roots, peripheral nerves, and often the cranial nerves.8 The Miller Fisher variant of GBS is characterized by bilateral ophthalmoparesis, areflexia, and ataxia.8 At the early stage of illness, the presentation may be similar to TNP.8 Brain imaging is normal in patients with GBS; the diagnosis is established via characteristic electromyography and cerebrospinal fluid findings.8

Myasthenia gravis often manifests with variable ptosis associated with diplopia.9 Symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral. The ice-pack test has been identified as a simple, preliminary test for ocular myasthenia. The test involves the application of an ice-pack over the lids for 5 minutes. A 50% reduction in at least 1 component of ocular deviation is considered a positive response.10 Its specificity reportedly reaches 100%, with a sensitivity of 80%.10

COVID-19 infection may also include neurologic manifestations. There are an increasing number of case reports of central nervous system abnormalities including TNP.11,12

Trauma, tumors, or an aneurysm could be at work in TNP

TNP associated with trauma usually develops secondary to compression from an expanding hematoma, although it may also be a result of irritation of the nerve from blood in the subarachnoid space.13 Estimates of the incidence of TNP due to trauma range from 12% to 26% of cases.1,14 Vehicle-related injury is the most frequent cause of trauma-related TNP.14

Continue to: Pituitary tumors

Pituitary tumors most commonly involve the oculomotor nerve; 14% to 30% of pituitary tumors lead to TNP.13 Pituitary apoplexy secondary to infarction or hemorrhage is often associated with visual field defects and TNP.13

An underlying aneurysm manifests in a minority (10% to 15%) of patients presenting with TNP.3

Imaging is key to getting at the cause of TNP

The evaluation of patients presenting with acute TNP should be focused first on detecting an aneurysmal compressive lesion.3 CTA is the imaging modality of choice.

Once an aneurysm has been ruled out, the work-up should include a lumbar puncture and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Older patients should be assessed for conditions such as hypertension or diabetes that put them at risk for microvascular disease.3 If microvascular TNP is unlikely, MRI with MR angiography is recommended to exclude other potential etiologies of TNP.3 If the patient is younger than 50 years of age, consider potential infectious and inflammatory etiologies (eg, giant cell arteritis).3

Treatment options are varied

The treatment of patients with TNP is specific to the disease state. For those patients with vascular risk factors and a presumptive diagnosis of microvascular TNP, it is reasonable to observe the patient for 2 to 3 months.3 Antiplatelet therapy is usually initiated. Patching 1 eye is useful in alleviating diplopia, particularly in the short term. In most cases, deficits related to TNP resolve over weeks to months. Deficits that persist beyond 6 months may require surgical intervention.

Continue to: "The tip of the iceberg"

TNP: “The tip of the iceberg”

TNP may signal a neurologic emergency, such as an aneurysm, or other conditions such as pituitary disease or giant cell arteritis. Any patient presenting with acute onset of TNP should undergo a noninvasive neuroimaging study.3

Our patient was treated for hypertension; however, she was lost to follow-up.

A 45-year-old woman visited the clinic 6 weeks after having a stroke while on her motorcycle, which resulted in a crash. She had not been wearing a helmet and was uncertain if she had sustained a head injury. She said that during the hospital stay following the accident, she was diagnosed as hypertensive; she denied any other significant prior medical history.

Following the crash, she said she’d been experiencing weakness in her right arm and leg and had been unable to open her right eye. When her right eye was opened manually, she said she had double vision and sensitivity to light.

On exam, the patient had exotropia with hypotropia of her right eye. Additionally, she had anisocoria with an enlarged, nonreactive right pupil (FIGURE 1A). She was unable to adduct, supraduct, or infraduct her right eye (FIGURE 1B). Her cranial nerves were otherwise intact. On manual strength testing, she had 4/5 strength of both her right upper and lower extremities.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Third (oculomotor) nerve palsy

This patient had a complete third nerve palsy (TNP). This is defined as palsy involving all of the muscles innervated by the oculomotor nerve, with pupillary involvement.1 The oculomotor nerve supplies motor innervation to the levator palpebrae superioris, superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior rectus, and inferior oblique muscles and parasympathetic innervation to the pupillary constrictor and ciliary muscles.2 As a result, patients present with exotropia and hypotropia on exam with anisocoria. Diplopia, ptosis, and an enlarged pupil are classic symptoms of TNP.2

Computed tomography (CT) of the brain performed immediately after this patient’s accident demonstrated a 15-mm hemorrhage within the left basal ganglia with mild associated edema, and a small focus of hyperattenuation within the right aspect of the suprasellar cistern. There was no evidence of skull fracture. CT angiography (CTA) of the brain showed no evidence of aneurysm.

Several days later, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain confirmed prior CT findings and revealed hemorrhagic contusions along the anterior and medial left temporal lobe. Additionally, the MRI showed subtle subdural hemorrhages along the midline falx and right parietal region, as well as diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage around both hemispheres, the interpeduncular cistern, and the suprasellar cistern (FIGURE 2). The basal ganglia hemorrhage was believed to have been a result of uncontrolled hypertension. The hemorrhage was responsible for her right-sided weakness and was the presumed cause of the accident. The other findings were due to head trauma. Her TNP was most likely caused by both compression and irritation of the right oculomotor nerve.

An uncommon occurrence

A population-based study identified the annual incidence of TNP to be 4 per 100,000.1 The mean age of onset was 42 years. The incidence in patients older than 60 years was greater than the incidence in those younger than 60.2 Isolated TNP occurred in approximately 40% of cases.2

Complete TNP is typically indicative of compression of the ipsilateral third nerve.2 The most common region for third nerve injury is the subarachnoid space, where the oculomotor nerve is vulnerable to compression, often by an aneurysm arising from the junction of the internal carotid and posterior communicating arteries.3

Continue to: Incomplete TNP

Incomplete TNP is often microvascular in origin and requires evaluation for diabetes and hypertension. Microvascular TNP is frequently painful but usually self-resolves after 2 to 4 months.2 Giant cell arteritis may also cause an isolated, painful TNP.2

A varied differential diagnosis and a TNP link to COVID-19

The differential diagnosis for TNP includes the following:

Orbital apex injury is usually seen after high-energy craniofacial trauma.4 Orbital apex fractures present with different signs and symptoms, depending on the degree of injury to neural and vascular structures. Various syndromes come into play, the most common being superior orbital fissure syndrome, which is characterized by dysfunction of cranial nerves III, IV, V, and VI.4 Features include ophthalmoplegia, upper eyelid ptosis, a nonreactive dilated pupil, anesthesia over the ipsilateral forehead, loss of corneal reflex, orbital pain, and proptosis.4

In patients with suspected orbital apex fractures, it’s important to assess for the presence of an optic neuropathy, an evolving orbital compartment syndrome, or a ruptured globe, because these 3 things may demand acute intervention.4

Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) is a mitochondrial disorder characterized by a slow, progressive paralysis of the extraocular muscles.5 Patients usually experience bilateral, symmetrical, progressive ptosis, followed by ophthalmoparesis months to years later. Ciliary and iris muscles are not involved. CPEO often occurs with other systemic features of mitochondrial dysfunction that can cause significant morbidity and mortality.5

Continue to: Graves ophthalmopathy

Graves ophthalmopathy arises from soft-tissue enlargement in the orbit, leading to increased pressure within the bony cavity.6 Approximately 40% of patients with Graves ophthalmopathy present with restrictive extraocular myopathy; however > 90% have eyelid retraction, as opposed to ptosis.7

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute, demyelinating immune-mediated polyneuropathy involving the spinal roots, peripheral nerves, and often the cranial nerves.8 The Miller Fisher variant of GBS is characterized by bilateral ophthalmoparesis, areflexia, and ataxia.8 At the early stage of illness, the presentation may be similar to TNP.8 Brain imaging is normal in patients with GBS; the diagnosis is established via characteristic electromyography and cerebrospinal fluid findings.8

Myasthenia gravis often manifests with variable ptosis associated with diplopia.9 Symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral. The ice-pack test has been identified as a simple, preliminary test for ocular myasthenia. The test involves the application of an ice-pack over the lids for 5 minutes. A 50% reduction in at least 1 component of ocular deviation is considered a positive response.10 Its specificity reportedly reaches 100%, with a sensitivity of 80%.10

COVID-19 infection may also include neurologic manifestations. There are an increasing number of case reports of central nervous system abnormalities including TNP.11,12

Trauma, tumors, or an aneurysm could be at work in TNP

TNP associated with trauma usually develops secondary to compression from an expanding hematoma, although it may also be a result of irritation of the nerve from blood in the subarachnoid space.13 Estimates of the incidence of TNP due to trauma range from 12% to 26% of cases.1,14 Vehicle-related injury is the most frequent cause of trauma-related TNP.14

Continue to: Pituitary tumors

Pituitary tumors most commonly involve the oculomotor nerve; 14% to 30% of pituitary tumors lead to TNP.13 Pituitary apoplexy secondary to infarction or hemorrhage is often associated with visual field defects and TNP.13

An underlying aneurysm manifests in a minority (10% to 15%) of patients presenting with TNP.3

Imaging is key to getting at the cause of TNP

The evaluation of patients presenting with acute TNP should be focused first on detecting an aneurysmal compressive lesion.3 CTA is the imaging modality of choice.

Once an aneurysm has been ruled out, the work-up should include a lumbar puncture and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Older patients should be assessed for conditions such as hypertension or diabetes that put them at risk for microvascular disease.3 If microvascular TNP is unlikely, MRI with MR angiography is recommended to exclude other potential etiologies of TNP.3 If the patient is younger than 50 years of age, consider potential infectious and inflammatory etiologies (eg, giant cell arteritis).3

Treatment options are varied

The treatment of patients with TNP is specific to the disease state. For those patients with vascular risk factors and a presumptive diagnosis of microvascular TNP, it is reasonable to observe the patient for 2 to 3 months.3 Antiplatelet therapy is usually initiated. Patching 1 eye is useful in alleviating diplopia, particularly in the short term. In most cases, deficits related to TNP resolve over weeks to months. Deficits that persist beyond 6 months may require surgical intervention.

Continue to: "The tip of the iceberg"

TNP: “The tip of the iceberg”

TNP may signal a neurologic emergency, such as an aneurysm, or other conditions such as pituitary disease or giant cell arteritis. Any patient presenting with acute onset of TNP should undergo a noninvasive neuroimaging study.3

Our patient was treated for hypertension; however, she was lost to follow-up.

1. Fang C, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, et al. Incidence and etiologies of acquired third nerve palsy using a population-based method. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:23-28. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.4456

2. Bruce BB, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Third nerve palsies. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:257-268. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979681

3. Margolin E, Freund P. A review of third nerve palsies. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2019;59:99-112. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000279

4. Linnau KF, Hallam DK, Lomoschitz FM, et al. Orbital apex injury: trauma at the junction between the face and the cranium. Eur J Radiol. 2003;48:5-16. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(03)00203-1

5. McClelland C, Manousakis G, Lee MS. Progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:53. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0652-7

6. Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726-738. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905750

7. Subetki I, Soewond P, Soebardi S, et al. Practical guidelines management of graves ophthalmopathy. Acta Med Indones. 2019;51:364-371.

8. Wijdicks EF, Klein CJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:467-479. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.002

9. Beloor Suresh A, Asuncion RMD. Myasthenia Gravis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Accessed April 26, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559331/

10. Chatzistefanou KI, Kouris T, Iliakis E, et al. The ice pack test in the differential diagnosis of myasthenic diplopia. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2236-2243. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.039

11. Pascual-Prieto J, Narváez-Palazón C, Porta-Etessam J, et al. COVID-19 epidemic: should ophthalmologists be aware of oculomotor paresis? Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2020;95:361-362. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2020.05.002

12. Collantes MEV, Espiritu AI, Sy MCC, et al. Neurological manifestations in COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48:66-76. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2020.146

13. Raza HK, Chen H, Chansysouphanthong T, et al. The aetiologies of the unilateral oculomotor nerve palsy: a review of the literature. Somatosens Mot Res. 2018;35:229-239. doi :10.1080/08990220.2018.1547697

14. Keane J. Third nerve palsy: analysis of 1400 personally-examined inpatients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:662-670. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100010866

1. Fang C, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, et al. Incidence and etiologies of acquired third nerve palsy using a population-based method. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:23-28. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.4456

2. Bruce BB, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Third nerve palsies. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:257-268. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979681

3. Margolin E, Freund P. A review of third nerve palsies. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2019;59:99-112. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000279

4. Linnau KF, Hallam DK, Lomoschitz FM, et al. Orbital apex injury: trauma at the junction between the face and the cranium. Eur J Radiol. 2003;48:5-16. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(03)00203-1

5. McClelland C, Manousakis G, Lee MS. Progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:53. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0652-7

6. Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726-738. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905750

7. Subetki I, Soewond P, Soebardi S, et al. Practical guidelines management of graves ophthalmopathy. Acta Med Indones. 2019;51:364-371.

8. Wijdicks EF, Klein CJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:467-479. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.002

9. Beloor Suresh A, Asuncion RMD. Myasthenia Gravis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Accessed April 26, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559331/

10. Chatzistefanou KI, Kouris T, Iliakis E, et al. The ice pack test in the differential diagnosis of myasthenic diplopia. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2236-2243. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.039

11. Pascual-Prieto J, Narváez-Palazón C, Porta-Etessam J, et al. COVID-19 epidemic: should ophthalmologists be aware of oculomotor paresis? Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2020;95:361-362. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2020.05.002

12. Collantes MEV, Espiritu AI, Sy MCC, et al. Neurological manifestations in COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48:66-76. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2020.146

13. Raza HK, Chen H, Chansysouphanthong T, et al. The aetiologies of the unilateral oculomotor nerve palsy: a review of the literature. Somatosens Mot Res. 2018;35:229-239. doi :10.1080/08990220.2018.1547697

14. Keane J. Third nerve palsy: analysis of 1400 personally-examined inpatients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:662-670. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100010866

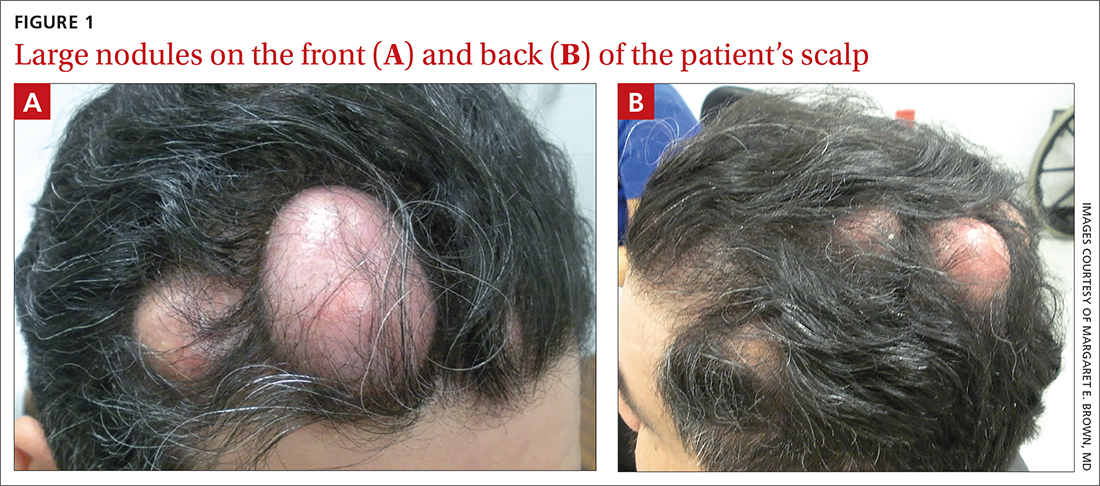

Numerous large nodules on scalp

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

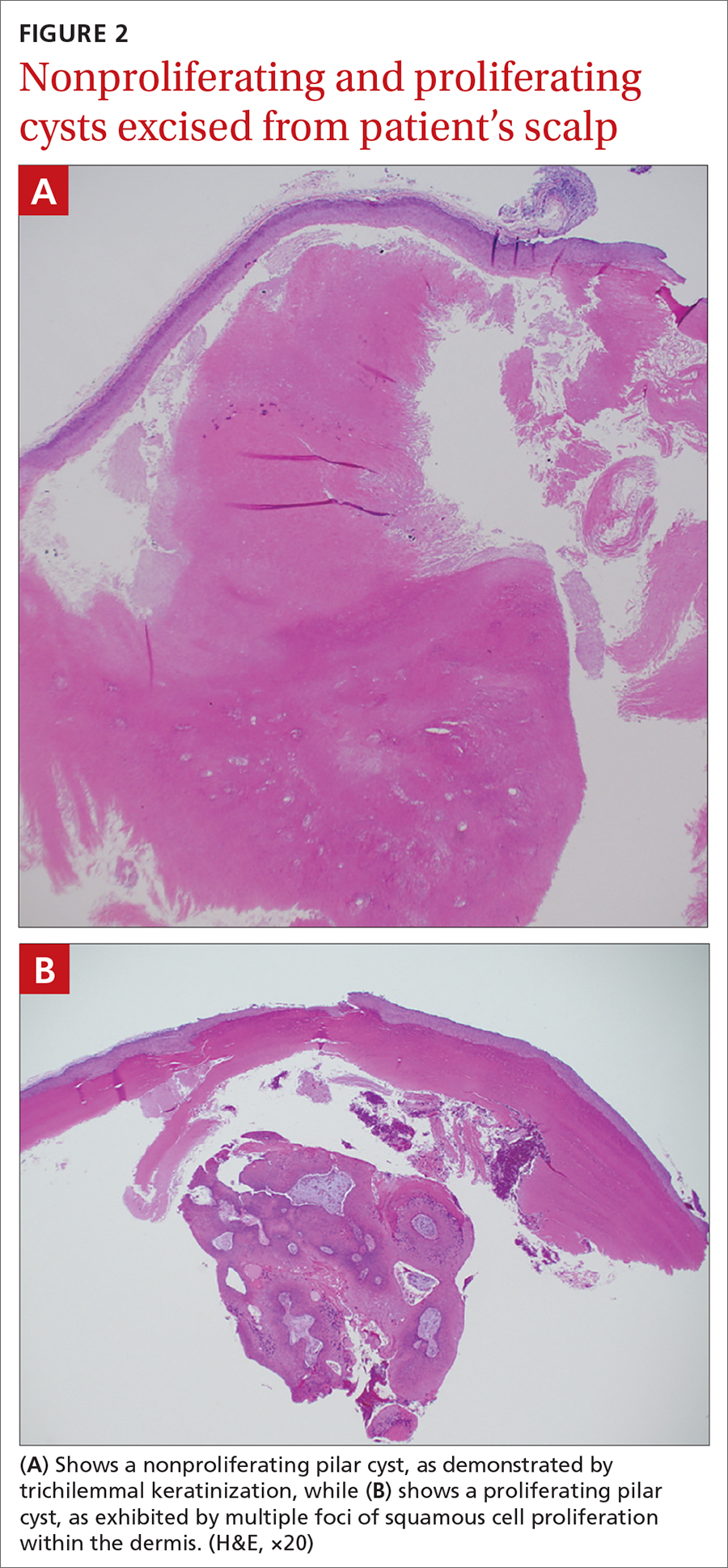

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

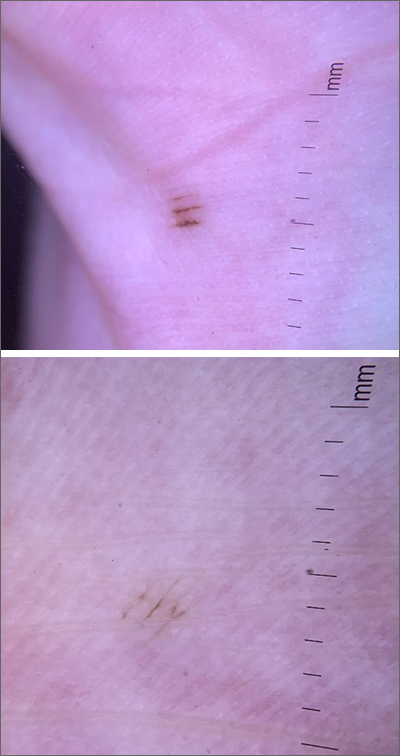

White macules on knee

The ivory white appearance and slight atrophy of the lesions raised the possibility of extragenital lichen sclerosus (LS). A 4-mm punch biopsy confirmed the diagnosis.

LS occurs in all races and is an uncommon, chronic inflammatory disease that most often affects the vulva and perianal mucosa in postmenopausal women.1 That said, it can also affect men and children, and manifest in places such as the trunk and neck. Extragenital lesions may appear ivory white, as in this case, or may resemble ecchymoses and raise alarm for possible abuse.

When LS is present on the extremities, a complete skin surface exam, including external genitalia, is warranted. LS is thought to be an autoimmune disease and is associated with vitiligo, autoimmune thyroid disease, and morphea.

In cases of suspected LS, it’s important to biopsy the full thickness of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is helpful to include an area of normal skin in the sample, as the findings are subtle and best contrasted with the architecture of unaffected skin. For this patient, a 4-mm punch biopsy was sufficient, but an incisional biopsy would be more appropriate for a larger patch or plaque.

Treatment options are based on a small case series and a few small randomized controlled trials. Medications include topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, systemic retinoids, and topical estrogens.

In this case, the patient was advised to apply topical clobetasol 0.05% cream bid to the affected area for 2 weeks, then twice weekly for 4 weeks. She had partial clearance with this approach, but small macules later appeared on her dorsal foot; the treatment was repeated.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JMC. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599. doi: 10.1111/pde.12615

The ivory white appearance and slight atrophy of the lesions raised the possibility of extragenital lichen sclerosus (LS). A 4-mm punch biopsy confirmed the diagnosis.

LS occurs in all races and is an uncommon, chronic inflammatory disease that most often affects the vulva and perianal mucosa in postmenopausal women.1 That said, it can also affect men and children, and manifest in places such as the trunk and neck. Extragenital lesions may appear ivory white, as in this case, or may resemble ecchymoses and raise alarm for possible abuse.

When LS is present on the extremities, a complete skin surface exam, including external genitalia, is warranted. LS is thought to be an autoimmune disease and is associated with vitiligo, autoimmune thyroid disease, and morphea.

In cases of suspected LS, it’s important to biopsy the full thickness of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is helpful to include an area of normal skin in the sample, as the findings are subtle and best contrasted with the architecture of unaffected skin. For this patient, a 4-mm punch biopsy was sufficient, but an incisional biopsy would be more appropriate for a larger patch or plaque.

Treatment options are based on a small case series and a few small randomized controlled trials. Medications include topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, systemic retinoids, and topical estrogens.

In this case, the patient was advised to apply topical clobetasol 0.05% cream bid to the affected area for 2 weeks, then twice weekly for 4 weeks. She had partial clearance with this approach, but small macules later appeared on her dorsal foot; the treatment was repeated.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The ivory white appearance and slight atrophy of the lesions raised the possibility of extragenital lichen sclerosus (LS). A 4-mm punch biopsy confirmed the diagnosis.

LS occurs in all races and is an uncommon, chronic inflammatory disease that most often affects the vulva and perianal mucosa in postmenopausal women.1 That said, it can also affect men and children, and manifest in places such as the trunk and neck. Extragenital lesions may appear ivory white, as in this case, or may resemble ecchymoses and raise alarm for possible abuse.

When LS is present on the extremities, a complete skin surface exam, including external genitalia, is warranted. LS is thought to be an autoimmune disease and is associated with vitiligo, autoimmune thyroid disease, and morphea.

In cases of suspected LS, it’s important to biopsy the full thickness of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is helpful to include an area of normal skin in the sample, as the findings are subtle and best contrasted with the architecture of unaffected skin. For this patient, a 4-mm punch biopsy was sufficient, but an incisional biopsy would be more appropriate for a larger patch or plaque.

Treatment options are based on a small case series and a few small randomized controlled trials. Medications include topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, systemic retinoids, and topical estrogens.

In this case, the patient was advised to apply topical clobetasol 0.05% cream bid to the affected area for 2 weeks, then twice weekly for 4 weeks. She had partial clearance with this approach, but small macules later appeared on her dorsal foot; the treatment was repeated.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JMC. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599. doi: 10.1111/pde.12615

1. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JMC. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599. doi: 10.1111/pde.12615

Brown plaque on the arm

Due to its size, 2 shave biopsies targeting the most concerning portions of the lesion were performed; the results were consistent with a lichenoid keratosis (LK), also known as lichen planus-like keratosis.

LK is a benign solitary lesion that mimics basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and superficial spreading or amelanotic melanoma.1 One theory suggests that LK is a solar lentigo or actinic keratosis undergoing attack from the immune system. Lesions most often manifest as a pink, gray, or brown macule to thin papule on the trunk or extremities. Itching or mild pain may be present. Dermoscopy can help distinguish an LK from malignancy but overlapping features of fine dark regression structures (called peppering, as seen in this case) should prompt further evaluation.

LKs are great mimics and biopsy is key to distinguishing them from cancer. In this case, shave biopsies were performed in the thickest and most characteristic portions of the lesion. Punch or incisional biopsies also would have been appropriate, but any result would have been a partial result. If the result had come back as an atypical melanocytic lesion, a complete excision would have been necessary to make sure the pathology reflected the entirety of the lesion.

Armed with the knowledge that the LK was benign, the patient in this case was scheduled for a follow-up visit for cryotherapy to remove the residual lesion.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Maor D, Ondhia C, Yu LL, et al. Lichenoid keratosis is frequently misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:663-666. doi: 10.1111/ced.13178

Due to its size, 2 shave biopsies targeting the most concerning portions of the lesion were performed; the results were consistent with a lichenoid keratosis (LK), also known as lichen planus-like keratosis.

LK is a benign solitary lesion that mimics basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and superficial spreading or amelanotic melanoma.1 One theory suggests that LK is a solar lentigo or actinic keratosis undergoing attack from the immune system. Lesions most often manifest as a pink, gray, or brown macule to thin papule on the trunk or extremities. Itching or mild pain may be present. Dermoscopy can help distinguish an LK from malignancy but overlapping features of fine dark regression structures (called peppering, as seen in this case) should prompt further evaluation.

LKs are great mimics and biopsy is key to distinguishing them from cancer. In this case, shave biopsies were performed in the thickest and most characteristic portions of the lesion. Punch or incisional biopsies also would have been appropriate, but any result would have been a partial result. If the result had come back as an atypical melanocytic lesion, a complete excision would have been necessary to make sure the pathology reflected the entirety of the lesion.

Armed with the knowledge that the LK was benign, the patient in this case was scheduled for a follow-up visit for cryotherapy to remove the residual lesion.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Due to its size, 2 shave biopsies targeting the most concerning portions of the lesion were performed; the results were consistent with a lichenoid keratosis (LK), also known as lichen planus-like keratosis.

LK is a benign solitary lesion that mimics basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and superficial spreading or amelanotic melanoma.1 One theory suggests that LK is a solar lentigo or actinic keratosis undergoing attack from the immune system. Lesions most often manifest as a pink, gray, or brown macule to thin papule on the trunk or extremities. Itching or mild pain may be present. Dermoscopy can help distinguish an LK from malignancy but overlapping features of fine dark regression structures (called peppering, as seen in this case) should prompt further evaluation.

LKs are great mimics and biopsy is key to distinguishing them from cancer. In this case, shave biopsies were performed in the thickest and most characteristic portions of the lesion. Punch or incisional biopsies also would have been appropriate, but any result would have been a partial result. If the result had come back as an atypical melanocytic lesion, a complete excision would have been necessary to make sure the pathology reflected the entirety of the lesion.

Armed with the knowledge that the LK was benign, the patient in this case was scheduled for a follow-up visit for cryotherapy to remove the residual lesion.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Maor D, Ondhia C, Yu LL, et al. Lichenoid keratosis is frequently misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:663-666. doi: 10.1111/ced.13178

1. Maor D, Ondhia C, Yu LL, et al. Lichenoid keratosis is frequently misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:663-666. doi: 10.1111/ced.13178

Perimenopausal woman with adnexal mass

The presence and location of this mass, paired with the patient’s symptoms, led to the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

PID is an acute infection of the upper genital tract in women that is thought to be due to an ascending infection from the lower genital tract. Diagnosis of PID in middle-aged women is a challenge, given the broad differential diagnosis of nonspecific presenting symptoms, lower index of suspicion in this age group, and unknown exact incidence of PID in postmenopausal women. Delay in diagnosis in postmenopausal women can pose serious potential complications such as tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA)—as was seen with this patient—and concurrent gynecologic malignancy found on pathology of TOA specimens.

Risk factors for PID in the postmenopausal population include recent uterine instrumentation, history of prior PID, and structural abnormalities such as cervical stenosis, uterine anatomic abnormalities, or tubal disease.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines recommend presumptive treatment for PID in women with pelvic or lower abdominal pain with 1 or more of the following clinical criteria: cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness. The CDC also suggests that the most specific criteria for PID include endometrial biopsy consistent with endometritis, imaging (transvaginal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) demonstrating fluid-filled tubes, or laparoscopic findings consistent with PID.

Due to the polymicrobial nature of PID, antibiotics should cover not only gonorrhea and chlamydia but also anaerobic pathogens. CDC guidelines recommend the following treatment:

- intravenous (IV) cefotetan (2 g bid) plus doxycycline (100 mg PO or IV bid),

- IV cefoxitin (2 g qid) plus doxycycline (100 mg PO or IV bid), or

- IV clindamycin (900 mg tid) plus IV or intramuscular gentamicin loading dose (2 mg/kg) followed by a maintenance dose (1.5 mg/kg tid).

Due to the increased risk of malignancy in postmenopausal women with TOA, surgical intervention may be needed.