User login

Blisters in a Comatose Elderly Woman

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

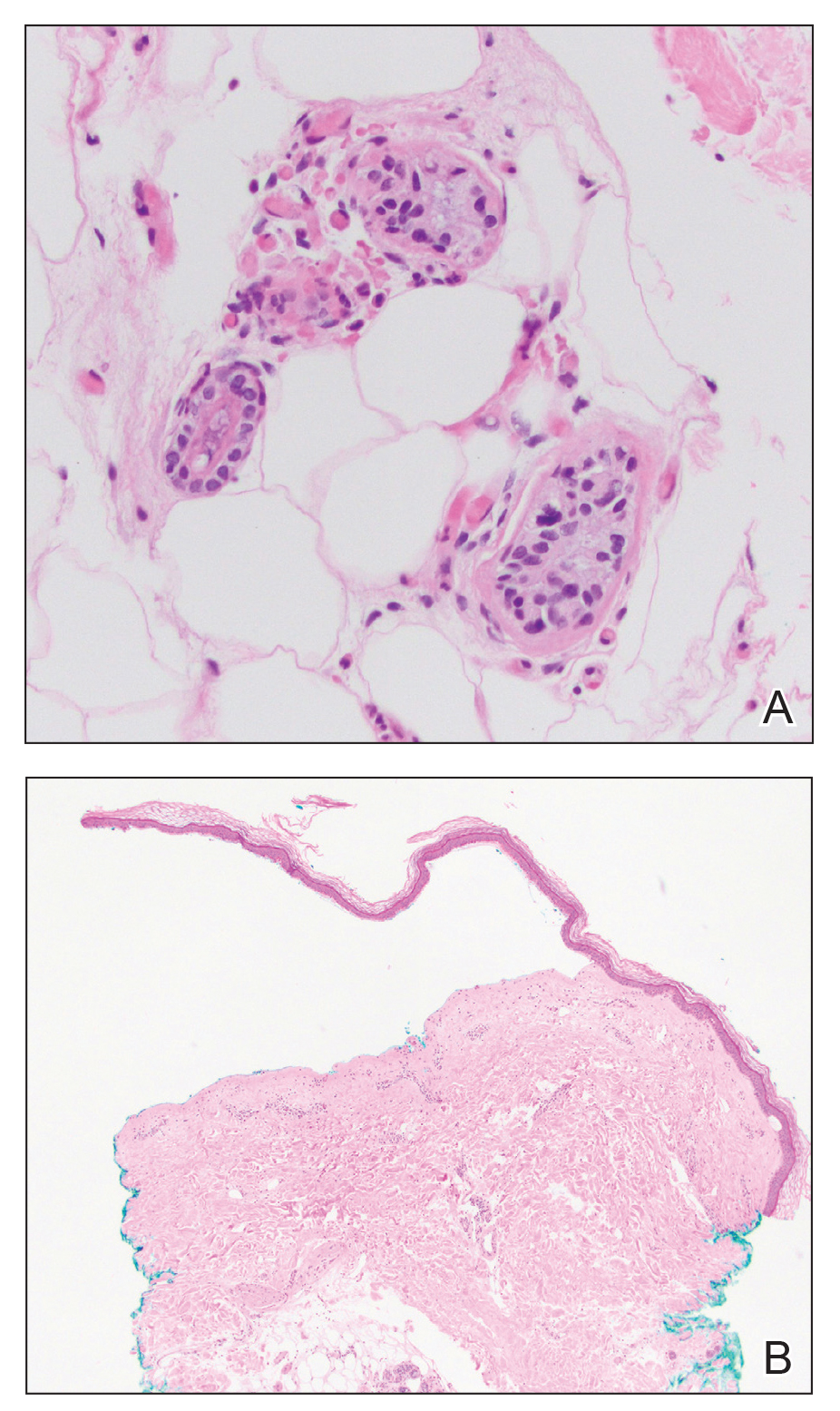

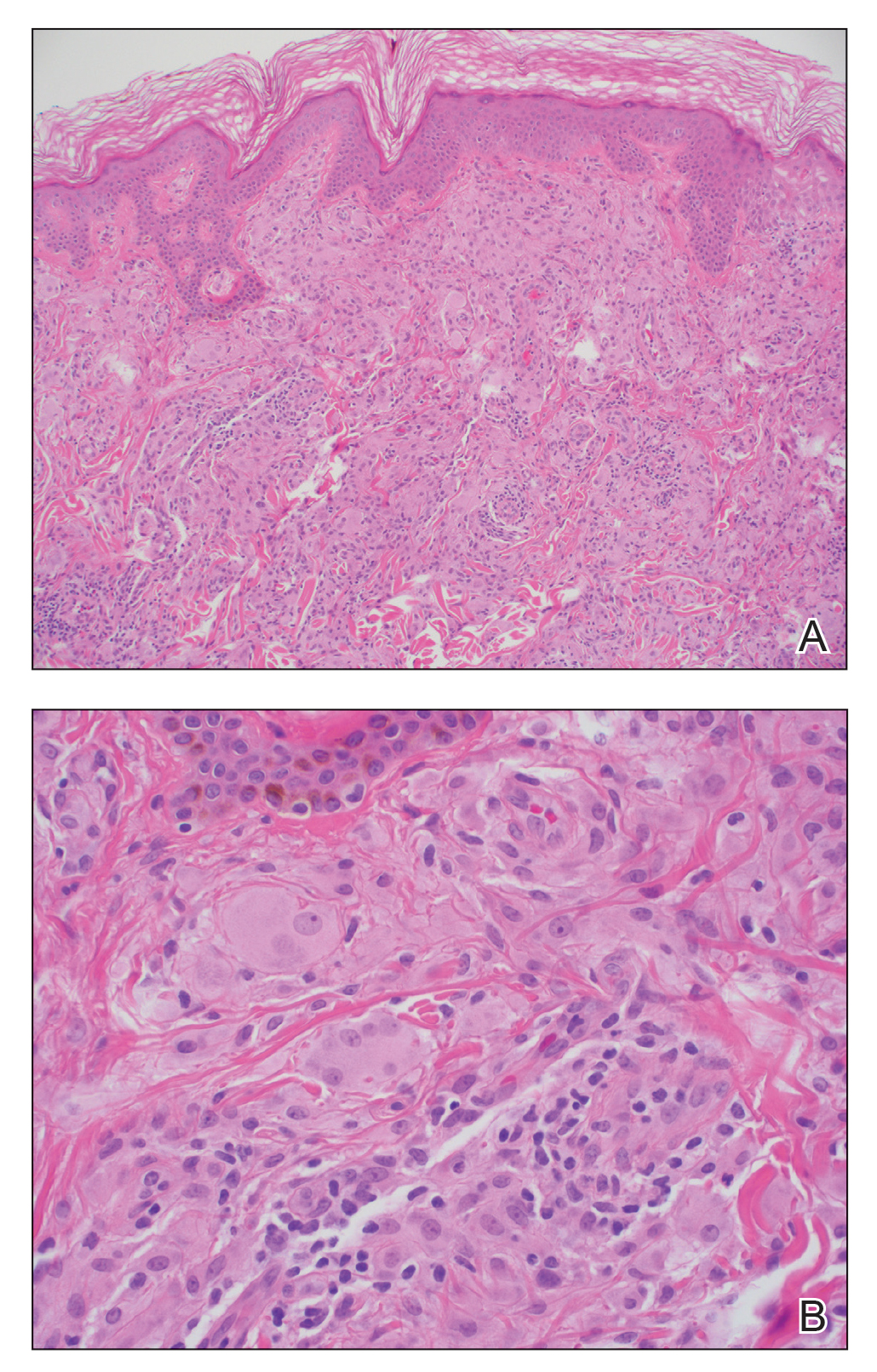

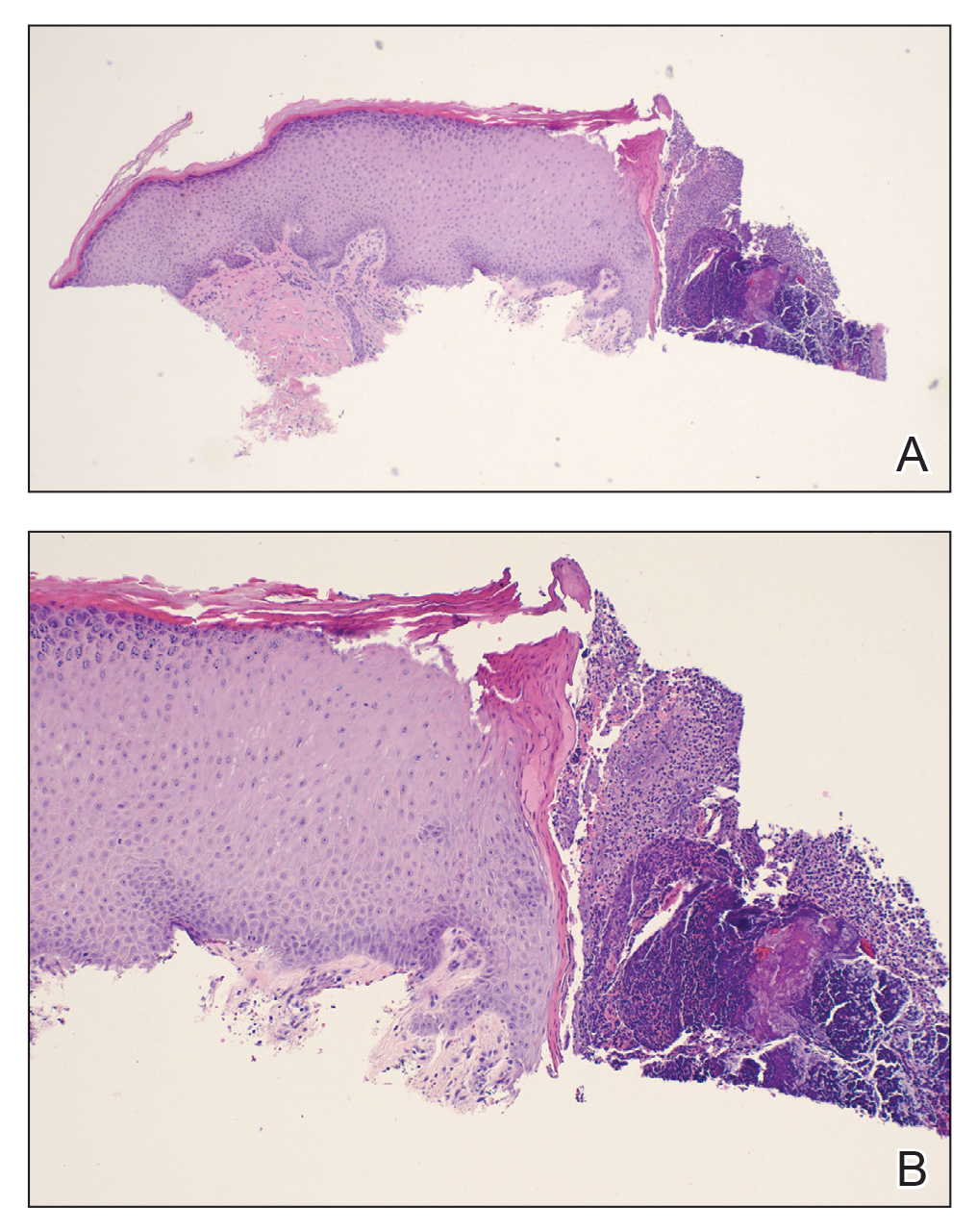

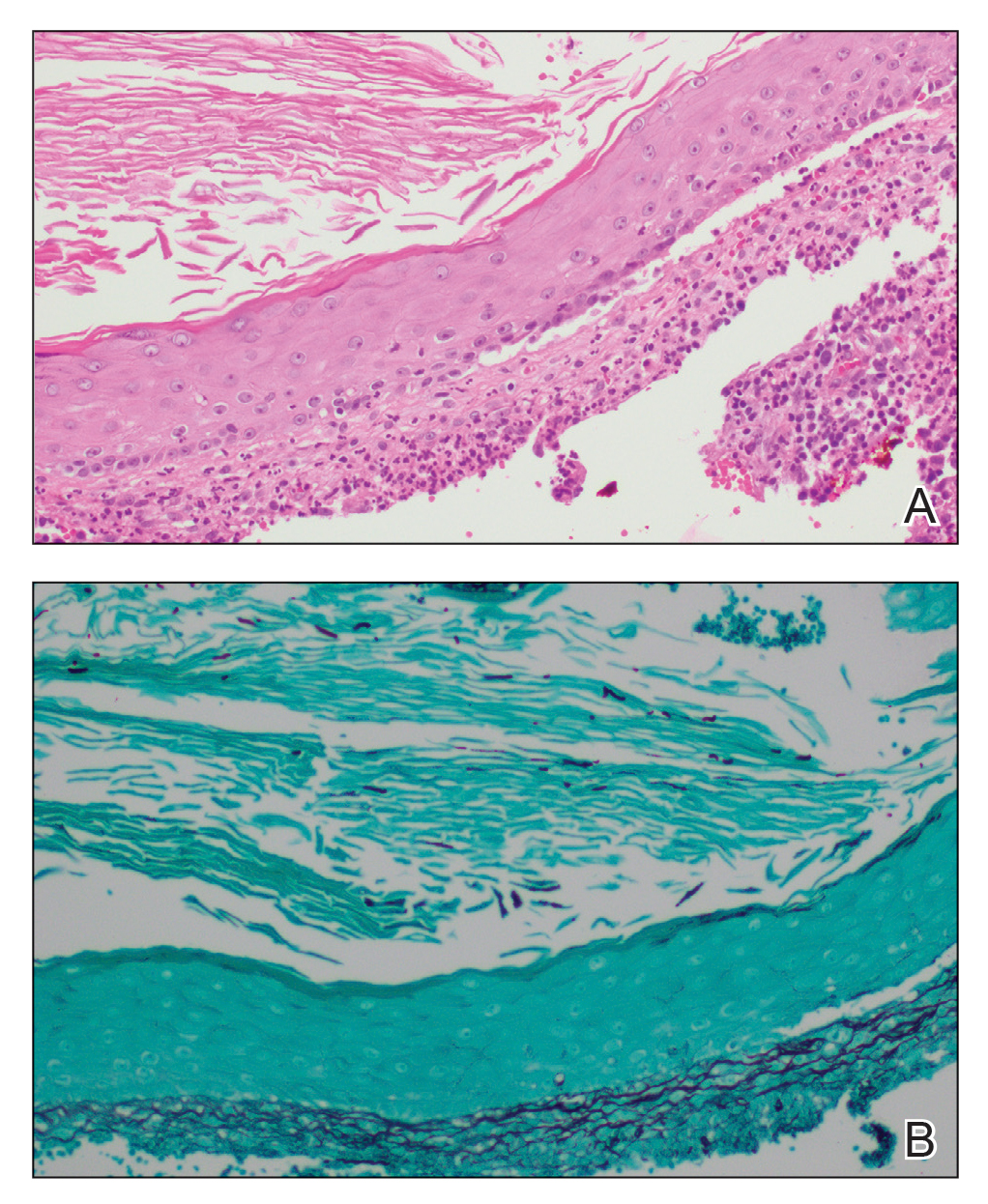

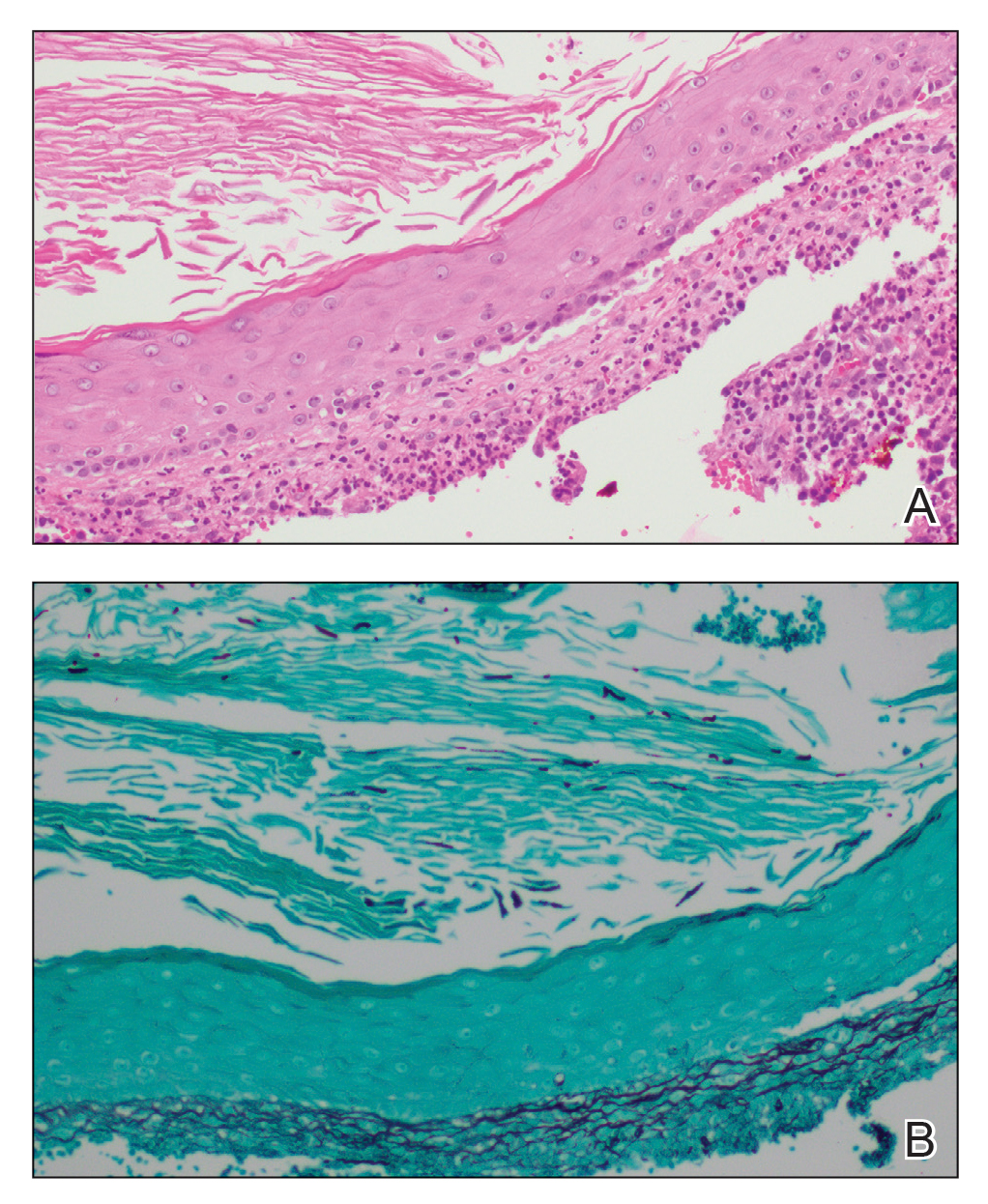

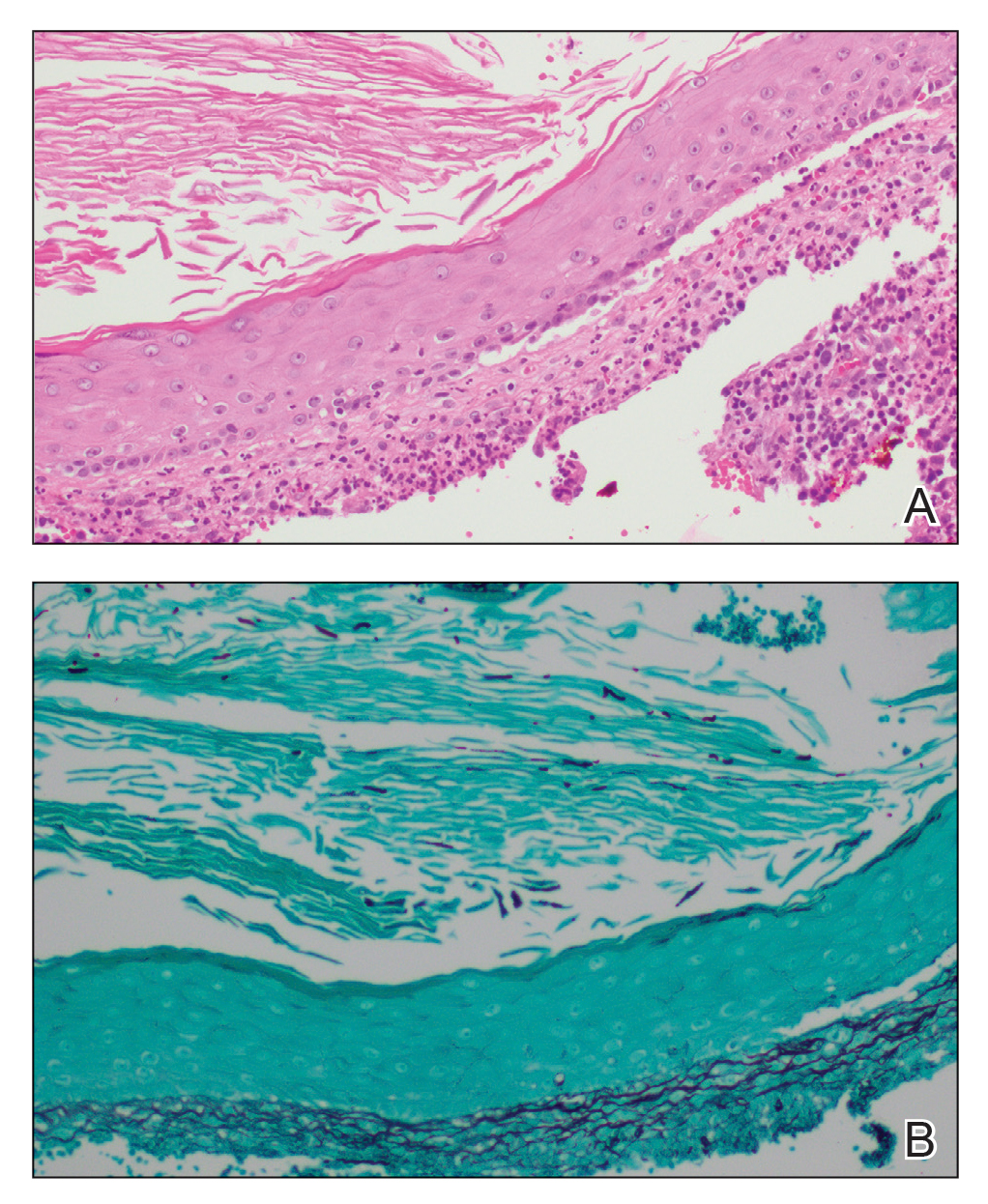

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

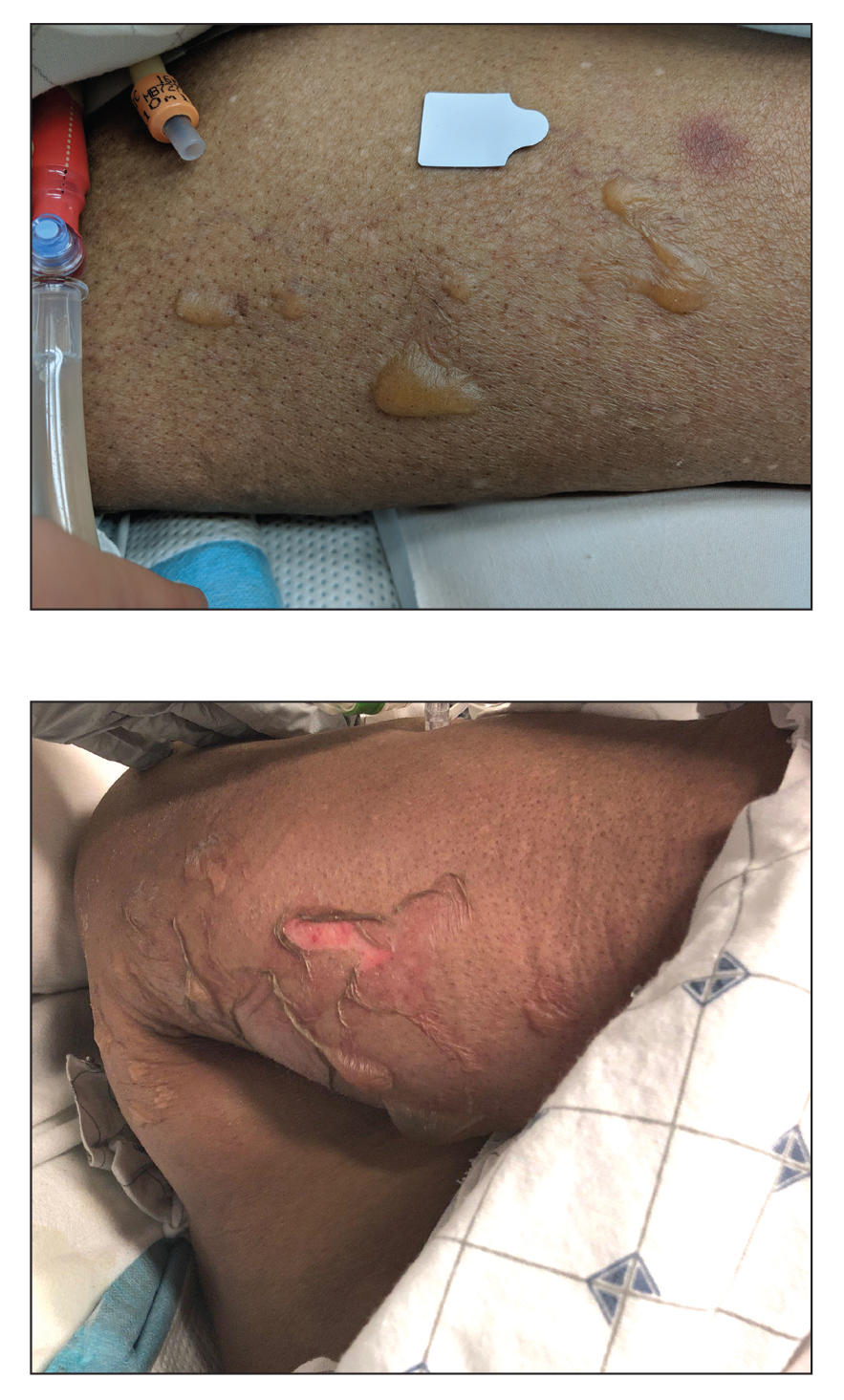

An 82-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after her daughter found her unconscious in the bathroom laying on her right side. Her medical history was notable for hypertension and asthma for which she was on losartan, furosemide, diltiazem, and albuterol. She recently had been prescribed lorazepam for insomnia and had started taking the medication 2 days prior. She underwent intubation and was noted to have flaccid, fluid-filled bullae on the right thigh (top) along with large areas of desquamation on the right lateral arm (bottom) with minimal surrounding erythema. There was no mucous membrane involvement. Urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and negative for all other drugs, including barbiturates.

Erythematous Indurated Nodule on the Forehead

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

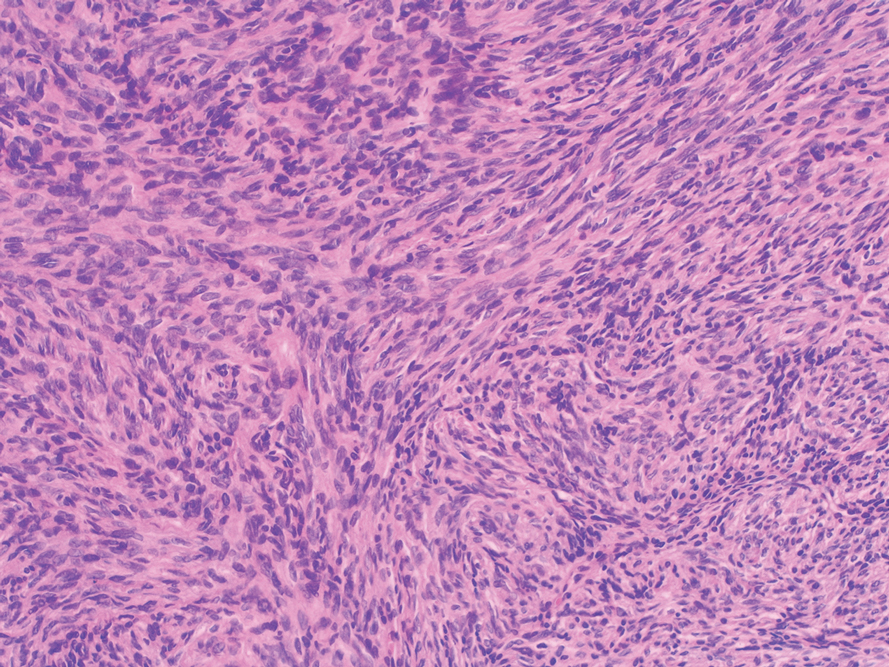

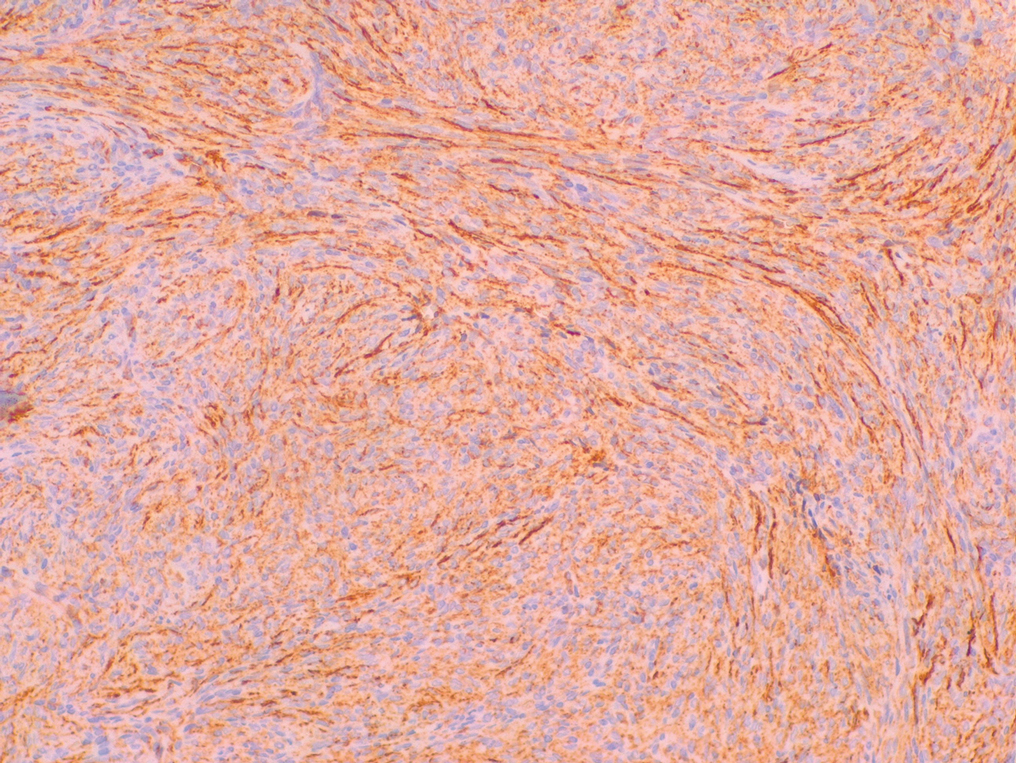

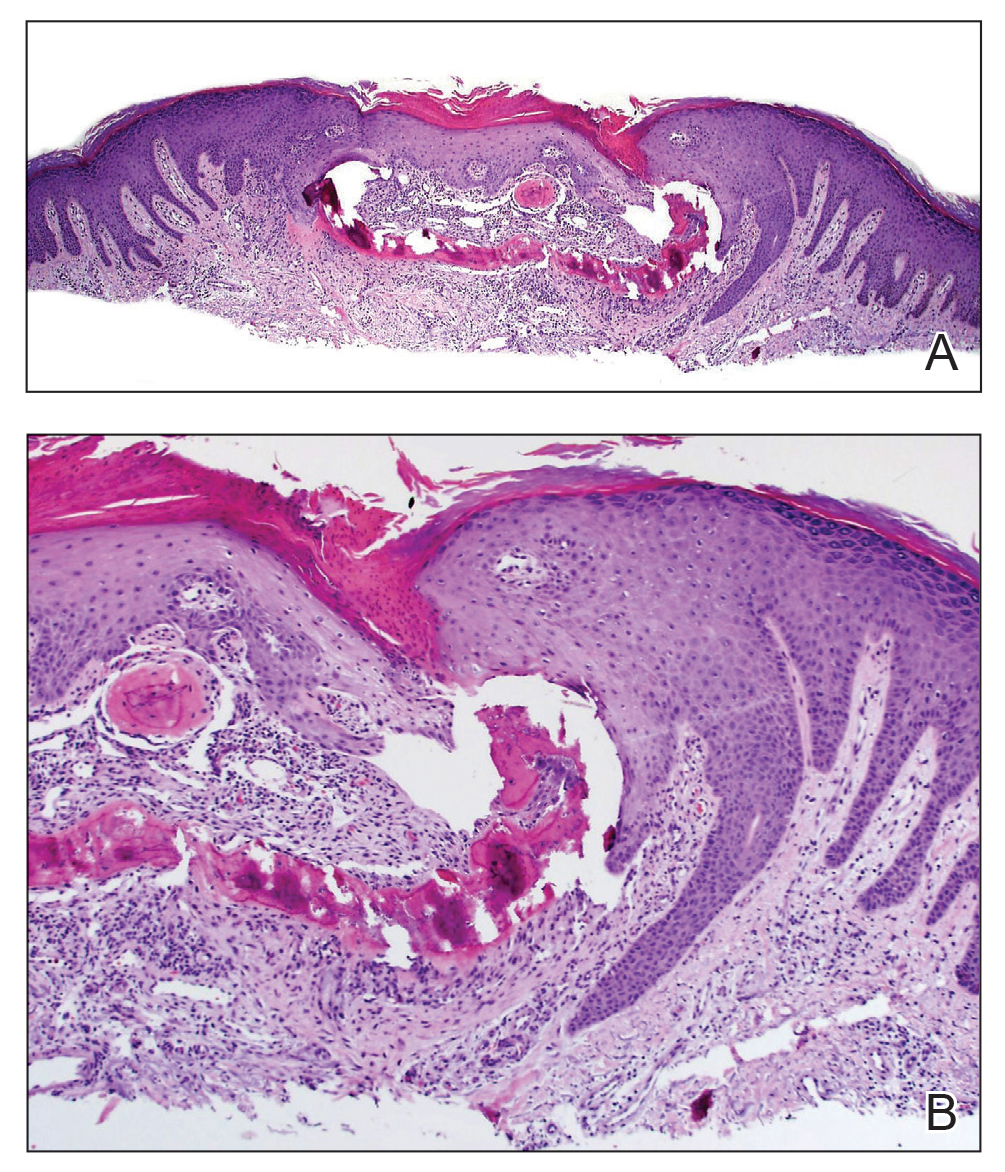

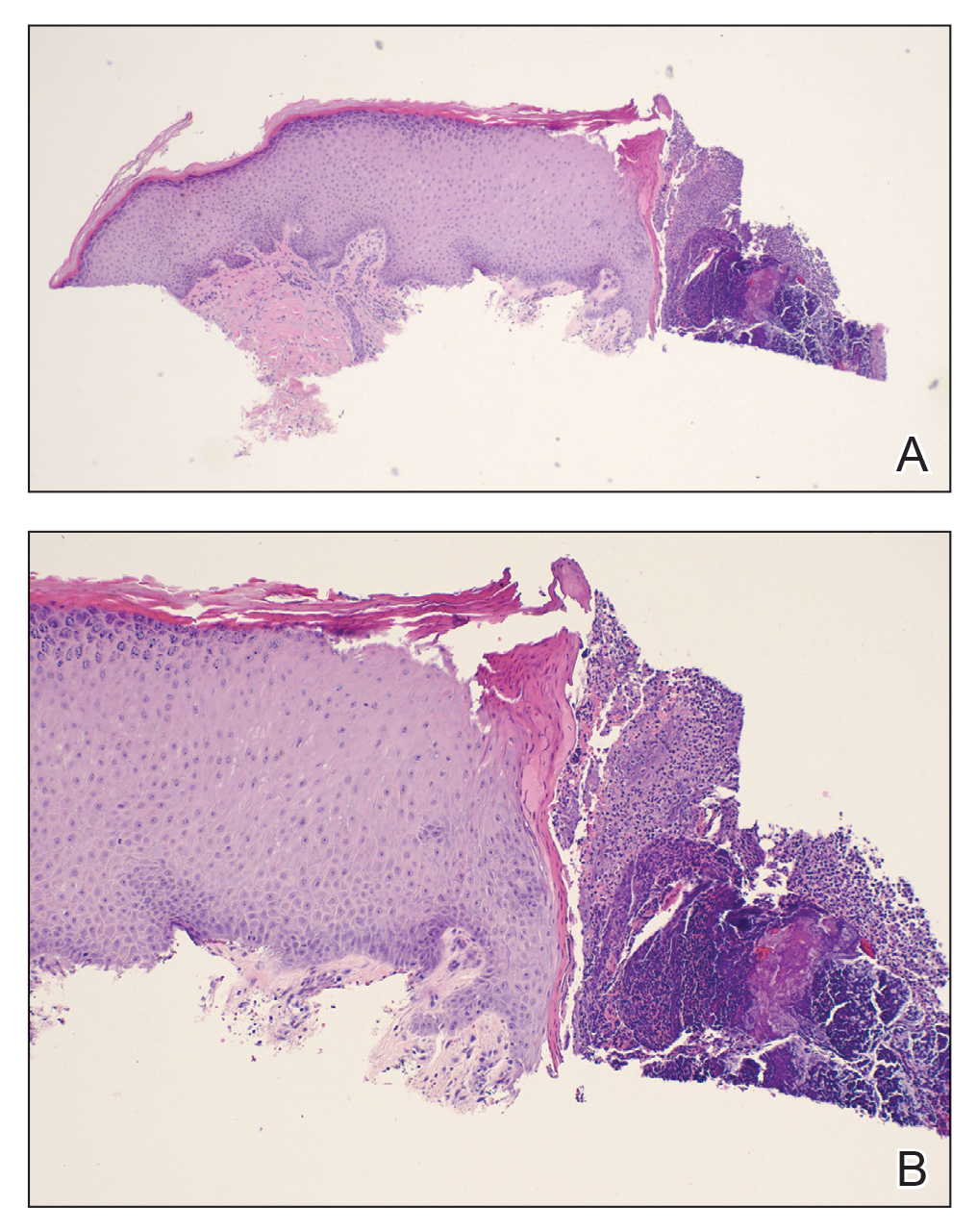

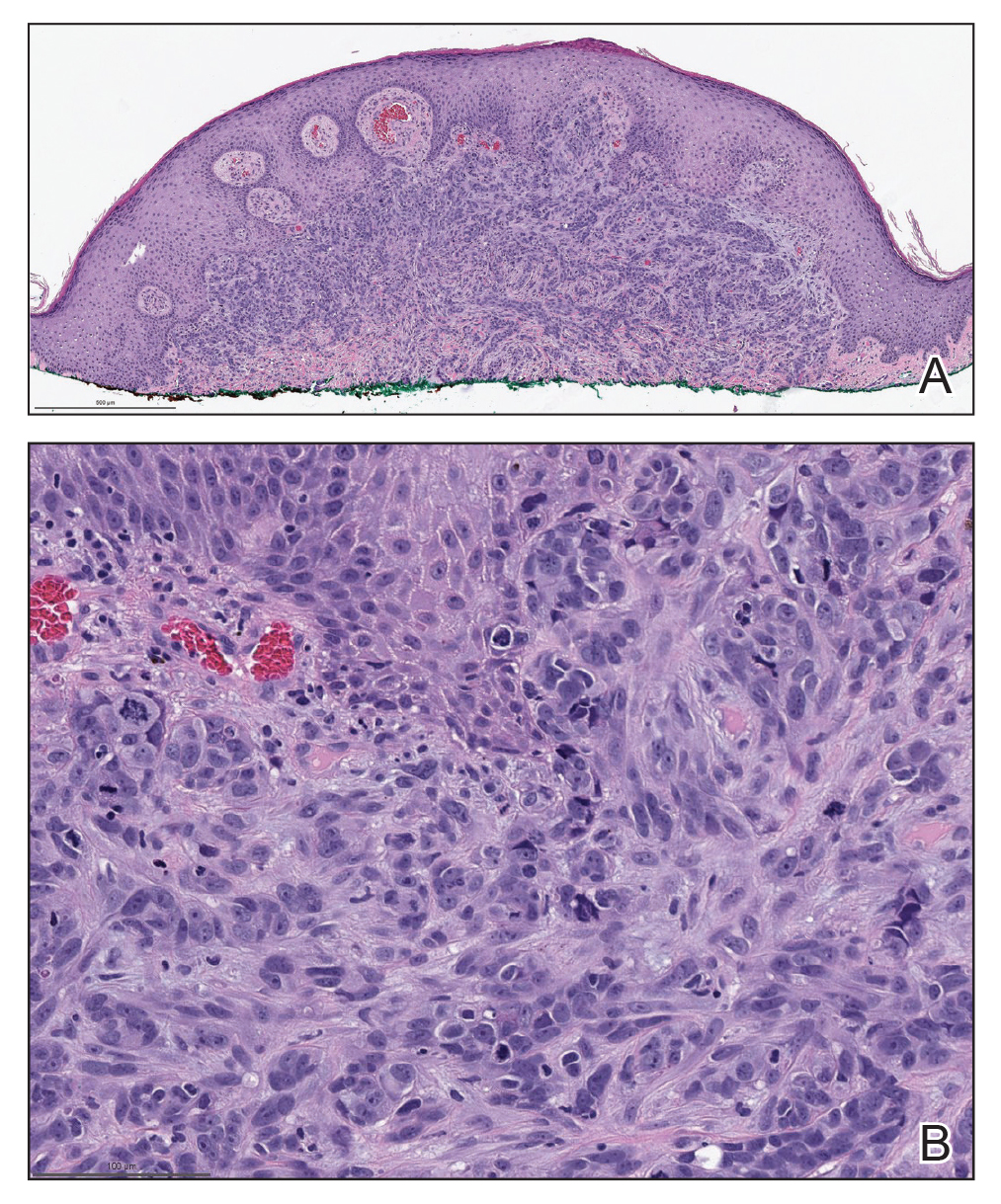

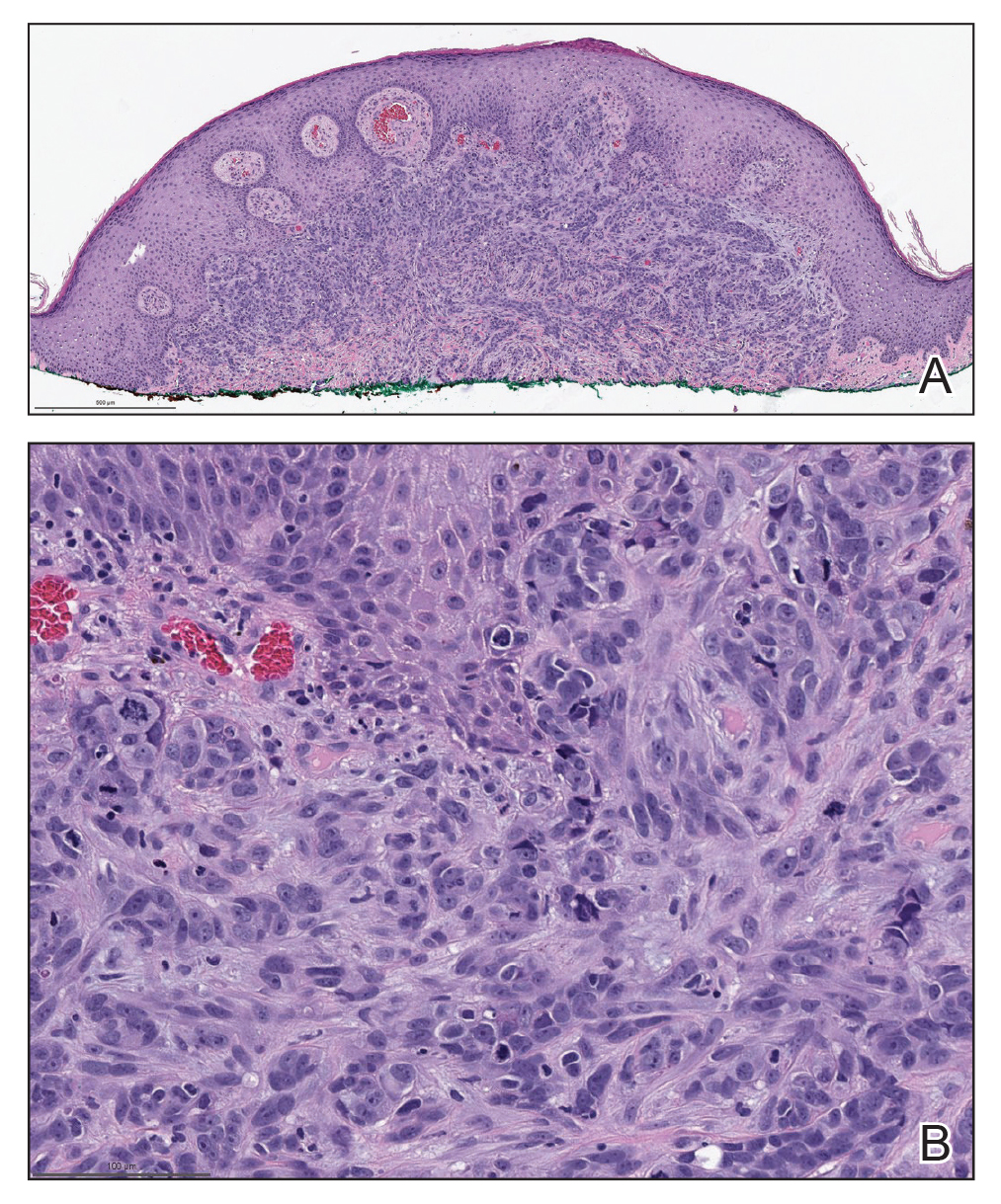

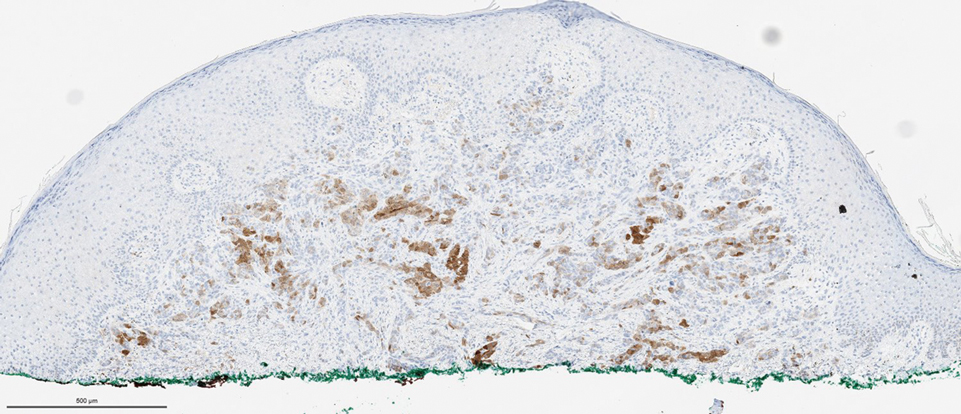

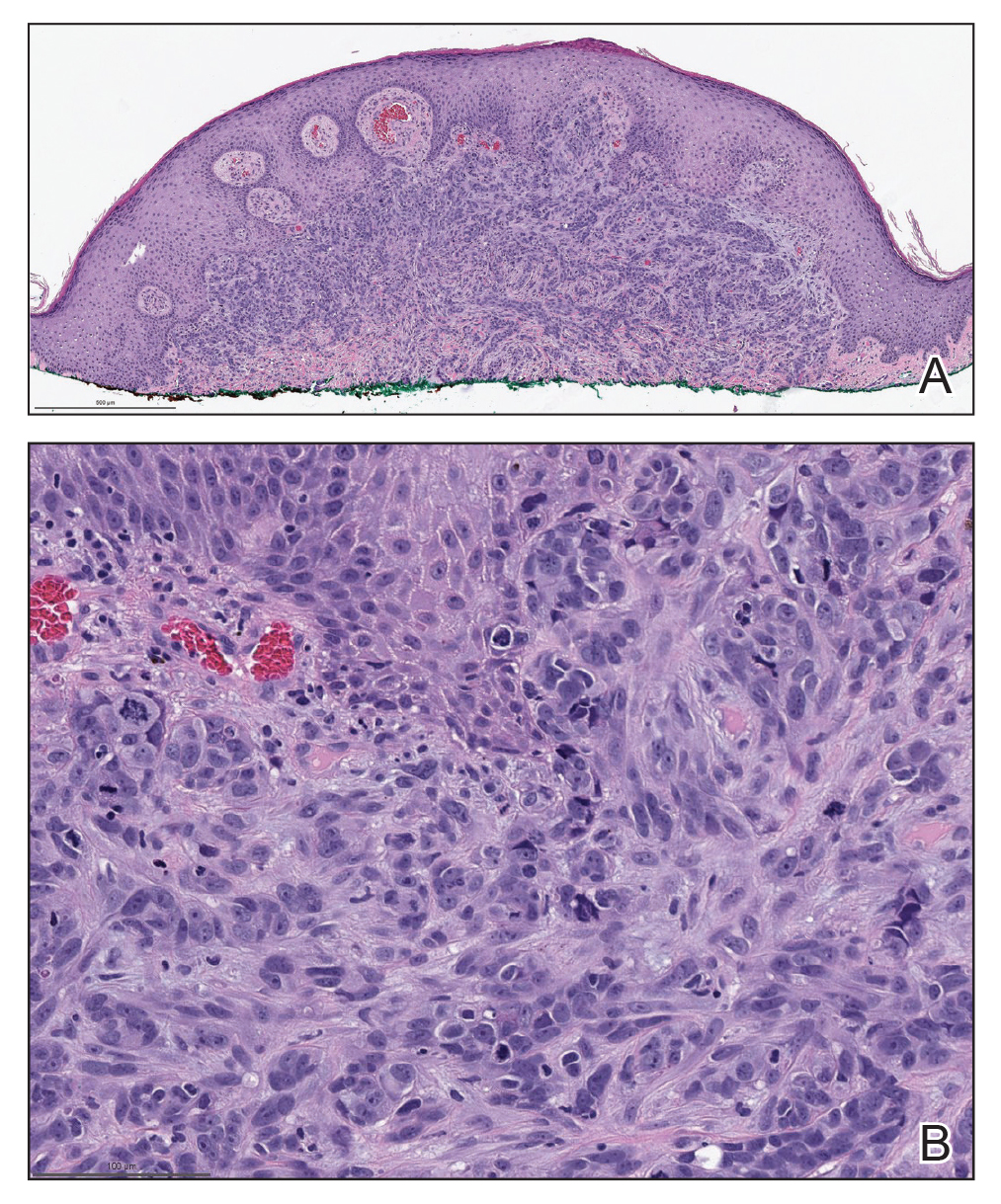

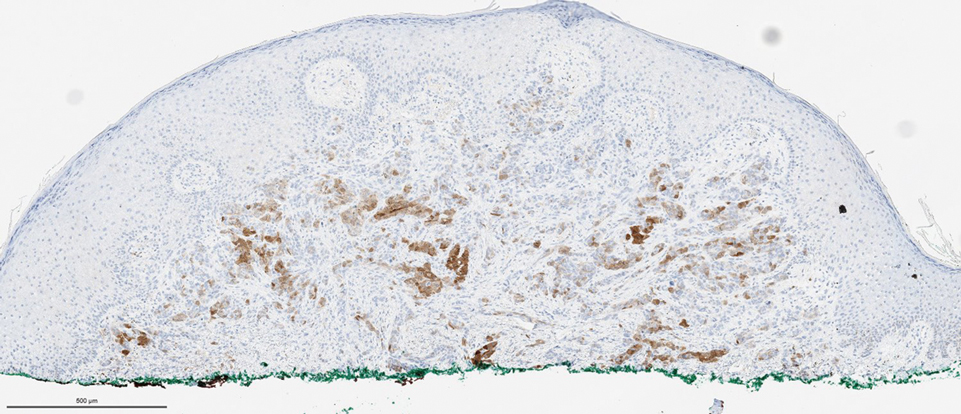

Histopathologic examination showed a dermal tumor composed of spindle cells in a storiform arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positive CD34 staining of the tumoral cells (Figure 2). Clinical review, histopathologic examination, and immunohistochemistry confirmed a diagnosis of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with clear margins after 3 stages, followed by repair with a rotation flap. No evidence of recurrence was found at 4-year follow-up.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare low-grade sarcoma of fibroblast origin with an annual incidence of 0.8 to 5 cases per million individuals.1 It typically presents in patients aged 30 to 50 years on the trunk, scalp, or proximal extremities as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored, erythematous or brown, indurated plaque or nodule.2 Due to its variable presentation, these lesions often may be misdiagnosed as lipomas or epidermoid cysts, preventing proper targeted treatment. Therefore, suspicious enlarging indurated nodules require a lower threshold for biopsy.1

A definitive diagnosis of DFSP is achieved after a biopsy and histopathologic evaluation. Hematoxylin and eosin staining typically shows diffuse infiltration of the dermis and the subcutaneous fat by densely packed, cytologic, relatively uniform, spindle-shaped tumor cells arranged in a characteristic storiform shape. Tumor cells are spread along the septae of the subcutaneous fatty tissue.3 Immunohistochemistry is characterized by positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa, with rare exceptions.

The differential diagnosis includes lipoma, epidermoid cyst, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.3 Positive CD34 immunostaining, negative S-100 staining, and a storiform pattern of spindle cells can assist in differentiating DFSP from these possible differential diagnoses; lesions of these other entities are characterized by different pathologic findings. Lipomas are composed of fat tissue, epidermoid cysts have epithelial-lined cysts filled with keratin, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors have plexiform rays of fibrous tissue extending into fat with negative CD34 staining, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors have fleshy variegated masses involving the peripheral nerve trunks with partial S-100 staining.4-7 Additional evaluation to confirm DFSP can be accomplished by analysis of tumor samples by fluorescence in situ hybridization or reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction to detect chromosomal translocations and fusion gene transcripts, as chromosomal translocations may be found in more than 90% of cases.3

Early diagnosis of DFSP is beneficial, as it can help prevent recurrence as well as metastasis. Studies have attempted to document the risk for recurrence as well as metastasis based on characteristic features and treatment strategies of DFSP. In a study of 186 patients, 3 had metastatic disease to the lungs, the most common site of metastasis.8 These 3 patients had fibrosarcomatous transformation within DFSP, emphasizing the importance of detailing this finding early in the diagnosis, as it was characterized by a higher degree of cellularity, cytologic atypia, mitotic activity, and negative CD34 immunostaining.9 In patients with suspected metastasis, lymph node ultrasonography, chest radiography, and computed tomography may be utilized.3

When treating DFSP, the goal is complete removal of the tumor with clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery, modified MMS, and wide local excision (WLE) with 2- to 4-cm margins are appropriate treatment options, though MMS is the treatment of choice. A study comparing MMS and WLE demonstrated 3% and 30.8% recurrence rates, respectively.8 In MMS, complete margin evaluation on microscopy is performed after each stage to ensure negative surgical margins. The presence of positive surgical margins elicits continued resection until the margins are clear.10,11

Other treatment modalities may be considered for patients with DFSP. Molecular therapy with imatinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting platelet-derived growth factor–regulated expression, can be utilized for inoperable tumors; however, additional clinical trials are required to ensure efficacy.3 Surgical removal of the possible remaining tumor is still recommended after molecular therapy. Radiotherapy is an additional method of treatment that may be used for inoperable tumors.3

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare lowgrade sarcoma of fibroblast origin that typically does not metastasize but often has notable subclinical extension and recurrence. Differentiating DFSP from other tumors often may be difficult. A protuberant, flesh-colored, slowgrowing, and asymptomatic lesion often may be confused with lipomas or epidermoid cysts; therefore, biopsies with immunohistostaining for suspicious lesions is required.12 Mohs micrographic surgery has evolved as the treatment of choice for this tumor, though WLE and new targeted molecular therapies still are considered. Proper diagnosis and treatment of DFSP is paramount in preventing future morbidity.

- Benoit A, Aycock J, Milam D, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead with extensive subclinical spread. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:261-264. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000604

- Khachemoune A, Barkoe D, Braun M, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead and scalp with involvement of the outer calvarial plate: multistaged repair with the use of skin expanders. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:115-119. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31021

- Saiag P, Grob J-J, Lebbe C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2604-2608. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.108

- Charifa A, Badri T. Lipomas, pathology. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Cyst, epidermoid (sebaceous cyst). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138. doi:10.5858 /2007-131-1135-PFTABR

- Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, et al. Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:295-319. doi:10.1007 /s00401-012-0954-z

- Lowe GC, Onajin O, Baum CL, et al. A comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision for treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with long-term follow-up: the Mayo Clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:98-106. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000910

- Rouhani P, Fletcher CDM, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous soft tissue sarcoma incidence patterns in the U.S.: an analysis of 12,114 cases. Cancer. 2008;113:616-627. doi:10.1002/cncr.23571

- Ratner D, Thomas CO, Johnson TM, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. results of a multiinstitutional series with an analysis of the extent of microscopic spread. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:600-613. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(97)70179-8

- Buck DW, Kim JYS, Alam M, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:861-866. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.039

- Shih P-Y, Chen C-H, Kuo T-T, et al. Deep dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a pitfall in the ultrasonographic diagnosis of lipoma -like subcutaneous lesions. Dermatologica Sinica. 2010;28:32-35. doi:10.1016/S1027-8117(10)60005-5

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Histopathologic examination showed a dermal tumor composed of spindle cells in a storiform arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positive CD34 staining of the tumoral cells (Figure 2). Clinical review, histopathologic examination, and immunohistochemistry confirmed a diagnosis of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with clear margins after 3 stages, followed by repair with a rotation flap. No evidence of recurrence was found at 4-year follow-up.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare low-grade sarcoma of fibroblast origin with an annual incidence of 0.8 to 5 cases per million individuals.1 It typically presents in patients aged 30 to 50 years on the trunk, scalp, or proximal extremities as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored, erythematous or brown, indurated plaque or nodule.2 Due to its variable presentation, these lesions often may be misdiagnosed as lipomas or epidermoid cysts, preventing proper targeted treatment. Therefore, suspicious enlarging indurated nodules require a lower threshold for biopsy.1

A definitive diagnosis of DFSP is achieved after a biopsy and histopathologic evaluation. Hematoxylin and eosin staining typically shows diffuse infiltration of the dermis and the subcutaneous fat by densely packed, cytologic, relatively uniform, spindle-shaped tumor cells arranged in a characteristic storiform shape. Tumor cells are spread along the septae of the subcutaneous fatty tissue.3 Immunohistochemistry is characterized by positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa, with rare exceptions.

The differential diagnosis includes lipoma, epidermoid cyst, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.3 Positive CD34 immunostaining, negative S-100 staining, and a storiform pattern of spindle cells can assist in differentiating DFSP from these possible differential diagnoses; lesions of these other entities are characterized by different pathologic findings. Lipomas are composed of fat tissue, epidermoid cysts have epithelial-lined cysts filled with keratin, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors have plexiform rays of fibrous tissue extending into fat with negative CD34 staining, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors have fleshy variegated masses involving the peripheral nerve trunks with partial S-100 staining.4-7 Additional evaluation to confirm DFSP can be accomplished by analysis of tumor samples by fluorescence in situ hybridization or reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction to detect chromosomal translocations and fusion gene transcripts, as chromosomal translocations may be found in more than 90% of cases.3

Early diagnosis of DFSP is beneficial, as it can help prevent recurrence as well as metastasis. Studies have attempted to document the risk for recurrence as well as metastasis based on characteristic features and treatment strategies of DFSP. In a study of 186 patients, 3 had metastatic disease to the lungs, the most common site of metastasis.8 These 3 patients had fibrosarcomatous transformation within DFSP, emphasizing the importance of detailing this finding early in the diagnosis, as it was characterized by a higher degree of cellularity, cytologic atypia, mitotic activity, and negative CD34 immunostaining.9 In patients with suspected metastasis, lymph node ultrasonography, chest radiography, and computed tomography may be utilized.3

When treating DFSP, the goal is complete removal of the tumor with clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery, modified MMS, and wide local excision (WLE) with 2- to 4-cm margins are appropriate treatment options, though MMS is the treatment of choice. A study comparing MMS and WLE demonstrated 3% and 30.8% recurrence rates, respectively.8 In MMS, complete margin evaluation on microscopy is performed after each stage to ensure negative surgical margins. The presence of positive surgical margins elicits continued resection until the margins are clear.10,11

Other treatment modalities may be considered for patients with DFSP. Molecular therapy with imatinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting platelet-derived growth factor–regulated expression, can be utilized for inoperable tumors; however, additional clinical trials are required to ensure efficacy.3 Surgical removal of the possible remaining tumor is still recommended after molecular therapy. Radiotherapy is an additional method of treatment that may be used for inoperable tumors.3

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare lowgrade sarcoma of fibroblast origin that typically does not metastasize but often has notable subclinical extension and recurrence. Differentiating DFSP from other tumors often may be difficult. A protuberant, flesh-colored, slowgrowing, and asymptomatic lesion often may be confused with lipomas or epidermoid cysts; therefore, biopsies with immunohistostaining for suspicious lesions is required.12 Mohs micrographic surgery has evolved as the treatment of choice for this tumor, though WLE and new targeted molecular therapies still are considered. Proper diagnosis and treatment of DFSP is paramount in preventing future morbidity.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Histopathologic examination showed a dermal tumor composed of spindle cells in a storiform arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positive CD34 staining of the tumoral cells (Figure 2). Clinical review, histopathologic examination, and immunohistochemistry confirmed a diagnosis of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with clear margins after 3 stages, followed by repair with a rotation flap. No evidence of recurrence was found at 4-year follow-up.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare low-grade sarcoma of fibroblast origin with an annual incidence of 0.8 to 5 cases per million individuals.1 It typically presents in patients aged 30 to 50 years on the trunk, scalp, or proximal extremities as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored, erythematous or brown, indurated plaque or nodule.2 Due to its variable presentation, these lesions often may be misdiagnosed as lipomas or epidermoid cysts, preventing proper targeted treatment. Therefore, suspicious enlarging indurated nodules require a lower threshold for biopsy.1

A definitive diagnosis of DFSP is achieved after a biopsy and histopathologic evaluation. Hematoxylin and eosin staining typically shows diffuse infiltration of the dermis and the subcutaneous fat by densely packed, cytologic, relatively uniform, spindle-shaped tumor cells arranged in a characteristic storiform shape. Tumor cells are spread along the septae of the subcutaneous fatty tissue.3 Immunohistochemistry is characterized by positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa, with rare exceptions.

The differential diagnosis includes lipoma, epidermoid cyst, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.3 Positive CD34 immunostaining, negative S-100 staining, and a storiform pattern of spindle cells can assist in differentiating DFSP from these possible differential diagnoses; lesions of these other entities are characterized by different pathologic findings. Lipomas are composed of fat tissue, epidermoid cysts have epithelial-lined cysts filled with keratin, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors have plexiform rays of fibrous tissue extending into fat with negative CD34 staining, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors have fleshy variegated masses involving the peripheral nerve trunks with partial S-100 staining.4-7 Additional evaluation to confirm DFSP can be accomplished by analysis of tumor samples by fluorescence in situ hybridization or reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction to detect chromosomal translocations and fusion gene transcripts, as chromosomal translocations may be found in more than 90% of cases.3

Early diagnosis of DFSP is beneficial, as it can help prevent recurrence as well as metastasis. Studies have attempted to document the risk for recurrence as well as metastasis based on characteristic features and treatment strategies of DFSP. In a study of 186 patients, 3 had metastatic disease to the lungs, the most common site of metastasis.8 These 3 patients had fibrosarcomatous transformation within DFSP, emphasizing the importance of detailing this finding early in the diagnosis, as it was characterized by a higher degree of cellularity, cytologic atypia, mitotic activity, and negative CD34 immunostaining.9 In patients with suspected metastasis, lymph node ultrasonography, chest radiography, and computed tomography may be utilized.3

When treating DFSP, the goal is complete removal of the tumor with clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery, modified MMS, and wide local excision (WLE) with 2- to 4-cm margins are appropriate treatment options, though MMS is the treatment of choice. A study comparing MMS and WLE demonstrated 3% and 30.8% recurrence rates, respectively.8 In MMS, complete margin evaluation on microscopy is performed after each stage to ensure negative surgical margins. The presence of positive surgical margins elicits continued resection until the margins are clear.10,11

Other treatment modalities may be considered for patients with DFSP. Molecular therapy with imatinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting platelet-derived growth factor–regulated expression, can be utilized for inoperable tumors; however, additional clinical trials are required to ensure efficacy.3 Surgical removal of the possible remaining tumor is still recommended after molecular therapy. Radiotherapy is an additional method of treatment that may be used for inoperable tumors.3

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare lowgrade sarcoma of fibroblast origin that typically does not metastasize but often has notable subclinical extension and recurrence. Differentiating DFSP from other tumors often may be difficult. A protuberant, flesh-colored, slowgrowing, and asymptomatic lesion often may be confused with lipomas or epidermoid cysts; therefore, biopsies with immunohistostaining for suspicious lesions is required.12 Mohs micrographic surgery has evolved as the treatment of choice for this tumor, though WLE and new targeted molecular therapies still are considered. Proper diagnosis and treatment of DFSP is paramount in preventing future morbidity.

- Benoit A, Aycock J, Milam D, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead with extensive subclinical spread. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:261-264. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000604

- Khachemoune A, Barkoe D, Braun M, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead and scalp with involvement of the outer calvarial plate: multistaged repair with the use of skin expanders. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:115-119. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31021

- Saiag P, Grob J-J, Lebbe C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2604-2608. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.108

- Charifa A, Badri T. Lipomas, pathology. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Cyst, epidermoid (sebaceous cyst). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138. doi:10.5858 /2007-131-1135-PFTABR

- Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, et al. Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:295-319. doi:10.1007 /s00401-012-0954-z

- Lowe GC, Onajin O, Baum CL, et al. A comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision for treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with long-term follow-up: the Mayo Clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:98-106. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000910

- Rouhani P, Fletcher CDM, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous soft tissue sarcoma incidence patterns in the U.S.: an analysis of 12,114 cases. Cancer. 2008;113:616-627. doi:10.1002/cncr.23571

- Ratner D, Thomas CO, Johnson TM, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. results of a multiinstitutional series with an analysis of the extent of microscopic spread. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:600-613. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(97)70179-8

- Buck DW, Kim JYS, Alam M, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:861-866. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.039

- Shih P-Y, Chen C-H, Kuo T-T, et al. Deep dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a pitfall in the ultrasonographic diagnosis of lipoma -like subcutaneous lesions. Dermatologica Sinica. 2010;28:32-35. doi:10.1016/S1027-8117(10)60005-5

- Benoit A, Aycock J, Milam D, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead with extensive subclinical spread. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:261-264. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000604

- Khachemoune A, Barkoe D, Braun M, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead and scalp with involvement of the outer calvarial plate: multistaged repair with the use of skin expanders. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:115-119. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31021

- Saiag P, Grob J-J, Lebbe C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2604-2608. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.108

- Charifa A, Badri T. Lipomas, pathology. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Cyst, epidermoid (sebaceous cyst). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138. doi:10.5858 /2007-131-1135-PFTABR

- Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, et al. Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:295-319. doi:10.1007 /s00401-012-0954-z

- Lowe GC, Onajin O, Baum CL, et al. A comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision for treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with long-term follow-up: the Mayo Clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:98-106. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000910

- Rouhani P, Fletcher CDM, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous soft tissue sarcoma incidence patterns in the U.S.: an analysis of 12,114 cases. Cancer. 2008;113:616-627. doi:10.1002/cncr.23571

- Ratner D, Thomas CO, Johnson TM, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. results of a multiinstitutional series with an analysis of the extent of microscopic spread. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:600-613. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(97)70179-8

- Buck DW, Kim JYS, Alam M, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:861-866. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.039

- Shih P-Y, Chen C-H, Kuo T-T, et al. Deep dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a pitfall in the ultrasonographic diagnosis of lipoma -like subcutaneous lesions. Dermatologica Sinica. 2010;28:32-35. doi:10.1016/S1027-8117(10)60005-5

A 39-year-old man presented with an enlarging asymptomatic nodule on the forehead of more than 3 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 3.4×2.3-cm, indurated, firm, erythematous nodule on the frontotemporal scalp. The patient denied any history of trauma to the area.

Indurated Mass on the Right Central Back

The Diagnosis: Actinomycetoma

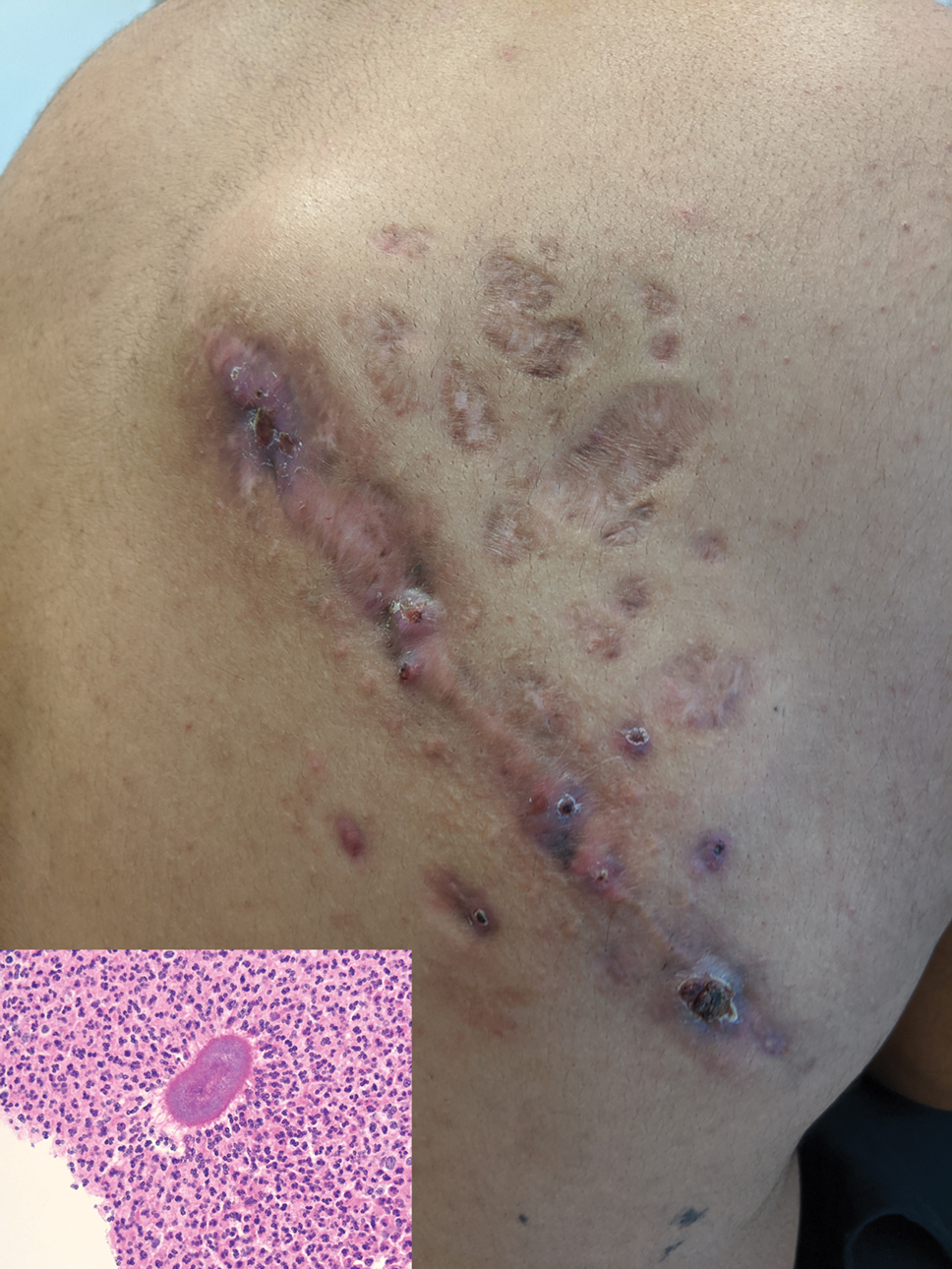

Histopathology revealed evidence of an actinomycete organism within the suppuration, consistent with actinomycosis (quiz image [inset]). Given the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings, our patient was diagnosed with actinomycetoma.

Actinomycetoma is an indolent, progressive, subcutaneous infection characterized by a well-known clinical triad of tumefaction/subcutaneous mass, draining sinuses, and an exudate containing grains on microscopy. The sinus tracts are formed from the chronic infectious process that destroys tissue, creating tunnels. This infectious disease of soft tissue is a clinical subset of mycetoma, which is categorized as eumycetoma (fungal) and actinomycetoma (bacterial). Actinomycetoma resembles the behavior of insidious and chronic fungal infections; however, most mycetoma infections are bacterial.1,2 Actinomycetoma may be confused with actinomycosis, which is caused by Actinomycoses species, commensal organisms commonly located on the teeth and oral mucosa in association with other microorganisms that may pathogenically cause cervicofacial actinomycosis.3,4 Actinomycetoma can be caused by Nocardia, Streptomyces, and Actinomadura. 2,5 The foot is the most common location of involvement followed by the thoracic region. It is more common in tropical or equatorial locations and may be contracted through exposure to soil or wood.5 Mycetoma is considered a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization.1 In tropical countries, this disease may go undiagnosed or untreated for so long that surgical amputation may be the only effective treatment.

Actinomycetoma commonly is identifiable by direct microscopy, Gram stain, or bacterial culture, with Gram stain being more sensitive than bacterial culture.3 It is important to indicate the suspected organism to the microbiology laboratory because common bacterial pathogens are detected within 24 to 48 hours, but the causative microorganism in actinomycetoma may require up to 4 weeks for culture,2 leading to possible false negatives due to inadequate culture time.3 Histopathology of actinomycotic infections will demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, focal suppuration, and the presence of grains (ie, a colony of filamentous bacteria in a stellate shaped mass)(quiz image [inset]).

The gold standard of treatment is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for up to several years.4,5 Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, dapsone, amikacin, streptomycin, and beta-lactams have been used successfully.2,5 The treatment course is dependent on clinical severity and location of the disease. The cure rate with appropriate antibiotics can be as high as 90%,2,5 and thus surgical intervention can be avoided.

In the differential, cutaneous tuberculosis would show tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes with possible caseation on histopathology, typically alongside positive tuberculosis screening. Botryomycosis has a similar clinical presentation of a swollen or indurated lesion with draining sinus tracts, but it less commonly occurs on the trunk. Histopathology also is a close mimic of actinomycetoma with a small grain inside a suppurative infiltrate; however, it has no filamentous bacteria. A foreign body reaction would not histologically present with suppuration or grains, and draining sinuses typically would not be seen on clinical presentation. Sarcoma is a neoplastic process and most commonly would show a proliferation of cells with soft tissue or bone origin on histopathology and not primarily an inflammatory cell process.6

- Verma P, Jha A. Mycetoma: reviewing a neglected disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:123-129.

- Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-197.

- Bennhoff DF. Actinomycosis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1198-1217.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R, Fernandez Martinez RF, Torres-Guerrero E, et al. Actinomycetoma: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Cutis. 2017;99:E11-E15.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

The Diagnosis: Actinomycetoma

Histopathology revealed evidence of an actinomycete organism within the suppuration, consistent with actinomycosis (quiz image [inset]). Given the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings, our patient was diagnosed with actinomycetoma.

Actinomycetoma is an indolent, progressive, subcutaneous infection characterized by a well-known clinical triad of tumefaction/subcutaneous mass, draining sinuses, and an exudate containing grains on microscopy. The sinus tracts are formed from the chronic infectious process that destroys tissue, creating tunnels. This infectious disease of soft tissue is a clinical subset of mycetoma, which is categorized as eumycetoma (fungal) and actinomycetoma (bacterial). Actinomycetoma resembles the behavior of insidious and chronic fungal infections; however, most mycetoma infections are bacterial.1,2 Actinomycetoma may be confused with actinomycosis, which is caused by Actinomycoses species, commensal organisms commonly located on the teeth and oral mucosa in association with other microorganisms that may pathogenically cause cervicofacial actinomycosis.3,4 Actinomycetoma can be caused by Nocardia, Streptomyces, and Actinomadura. 2,5 The foot is the most common location of involvement followed by the thoracic region. It is more common in tropical or equatorial locations and may be contracted through exposure to soil or wood.5 Mycetoma is considered a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization.1 In tropical countries, this disease may go undiagnosed or untreated for so long that surgical amputation may be the only effective treatment.

Actinomycetoma commonly is identifiable by direct microscopy, Gram stain, or bacterial culture, with Gram stain being more sensitive than bacterial culture.3 It is important to indicate the suspected organism to the microbiology laboratory because common bacterial pathogens are detected within 24 to 48 hours, but the causative microorganism in actinomycetoma may require up to 4 weeks for culture,2 leading to possible false negatives due to inadequate culture time.3 Histopathology of actinomycotic infections will demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, focal suppuration, and the presence of grains (ie, a colony of filamentous bacteria in a stellate shaped mass)(quiz image [inset]).

The gold standard of treatment is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for up to several years.4,5 Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, dapsone, amikacin, streptomycin, and beta-lactams have been used successfully.2,5 The treatment course is dependent on clinical severity and location of the disease. The cure rate with appropriate antibiotics can be as high as 90%,2,5 and thus surgical intervention can be avoided.

In the differential, cutaneous tuberculosis would show tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes with possible caseation on histopathology, typically alongside positive tuberculosis screening. Botryomycosis has a similar clinical presentation of a swollen or indurated lesion with draining sinus tracts, but it less commonly occurs on the trunk. Histopathology also is a close mimic of actinomycetoma with a small grain inside a suppurative infiltrate; however, it has no filamentous bacteria. A foreign body reaction would not histologically present with suppuration or grains, and draining sinuses typically would not be seen on clinical presentation. Sarcoma is a neoplastic process and most commonly would show a proliferation of cells with soft tissue or bone origin on histopathology and not primarily an inflammatory cell process.6

The Diagnosis: Actinomycetoma

Histopathology revealed evidence of an actinomycete organism within the suppuration, consistent with actinomycosis (quiz image [inset]). Given the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings, our patient was diagnosed with actinomycetoma.

Actinomycetoma is an indolent, progressive, subcutaneous infection characterized by a well-known clinical triad of tumefaction/subcutaneous mass, draining sinuses, and an exudate containing grains on microscopy. The sinus tracts are formed from the chronic infectious process that destroys tissue, creating tunnels. This infectious disease of soft tissue is a clinical subset of mycetoma, which is categorized as eumycetoma (fungal) and actinomycetoma (bacterial). Actinomycetoma resembles the behavior of insidious and chronic fungal infections; however, most mycetoma infections are bacterial.1,2 Actinomycetoma may be confused with actinomycosis, which is caused by Actinomycoses species, commensal organisms commonly located on the teeth and oral mucosa in association with other microorganisms that may pathogenically cause cervicofacial actinomycosis.3,4 Actinomycetoma can be caused by Nocardia, Streptomyces, and Actinomadura. 2,5 The foot is the most common location of involvement followed by the thoracic region. It is more common in tropical or equatorial locations and may be contracted through exposure to soil or wood.5 Mycetoma is considered a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization.1 In tropical countries, this disease may go undiagnosed or untreated for so long that surgical amputation may be the only effective treatment.

Actinomycetoma commonly is identifiable by direct microscopy, Gram stain, or bacterial culture, with Gram stain being more sensitive than bacterial culture.3 It is important to indicate the suspected organism to the microbiology laboratory because common bacterial pathogens are detected within 24 to 48 hours, but the causative microorganism in actinomycetoma may require up to 4 weeks for culture,2 leading to possible false negatives due to inadequate culture time.3 Histopathology of actinomycotic infections will demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, focal suppuration, and the presence of grains (ie, a colony of filamentous bacteria in a stellate shaped mass)(quiz image [inset]).

The gold standard of treatment is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for up to several years.4,5 Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, dapsone, amikacin, streptomycin, and beta-lactams have been used successfully.2,5 The treatment course is dependent on clinical severity and location of the disease. The cure rate with appropriate antibiotics can be as high as 90%,2,5 and thus surgical intervention can be avoided.

In the differential, cutaneous tuberculosis would show tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes with possible caseation on histopathology, typically alongside positive tuberculosis screening. Botryomycosis has a similar clinical presentation of a swollen or indurated lesion with draining sinus tracts, but it less commonly occurs on the trunk. Histopathology also is a close mimic of actinomycetoma with a small grain inside a suppurative infiltrate; however, it has no filamentous bacteria. A foreign body reaction would not histologically present with suppuration or grains, and draining sinuses typically would not be seen on clinical presentation. Sarcoma is a neoplastic process and most commonly would show a proliferation of cells with soft tissue or bone origin on histopathology and not primarily an inflammatory cell process.6

- Verma P, Jha A. Mycetoma: reviewing a neglected disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:123-129.

- Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-197.

- Bennhoff DF. Actinomycosis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1198-1217.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R, Fernandez Martinez RF, Torres-Guerrero E, et al. Actinomycetoma: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Cutis. 2017;99:E11-E15.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Verma P, Jha A. Mycetoma: reviewing a neglected disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:123-129.

- Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-197.

- Bennhoff DF. Actinomycosis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1198-1217.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R, Fernandez Martinez RF, Torres-Guerrero E, et al. Actinomycetoma: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Cutis. 2017;99:E11-E15.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

A 26-year-old Guatemalan man who was a former carpenter presented with an indurated, nontender, nonpruritic, subcutaneous mass on the right central back with multiple draining sinus tracts on the surface and several depressed circular atrophic scars on the periphery of the mass. He noticed that the lesion began as a pustule 1.5 years prior and gradually enlarged. He denied any trauma, insect bites, fever, chills, headaches, weight loss, or travel history (he relocated to the United States 3.5 years ago) prior to the skin eruption. A biopsy was performed by an outside dermatologist 1 year prior to the current presentation, with a diagnosis of Pityrosporum folliculitis. Throughout his clinical course, treatment with oral antifungals, oral doxycycline, and topical clindamycin all failed. The mass was removed by plastic surgery 1 year prior.

A tissue biopsy for histology and culture was obtained at presentation to our institution. Laboratory findings showed that the basic metabolic panel was within reference range. Chest radiography indicated no active disease. A tuberculosis screening was negative. A bacterial culture of the lesion identified no growth after 48 hours. Our tissue biopsy revealed fibrosing granulation tissue, but the surgical pathology from a prior mass excision revealed sinus tracts with suppuration, evidence of scarring, foreign body giant cell reaction, and a characteristic finding (inset: H&E, original magnification ×200).

Pruritic Eruption on the Trunk and Extremities

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Acquired Perforating Disorder of Renal Disease

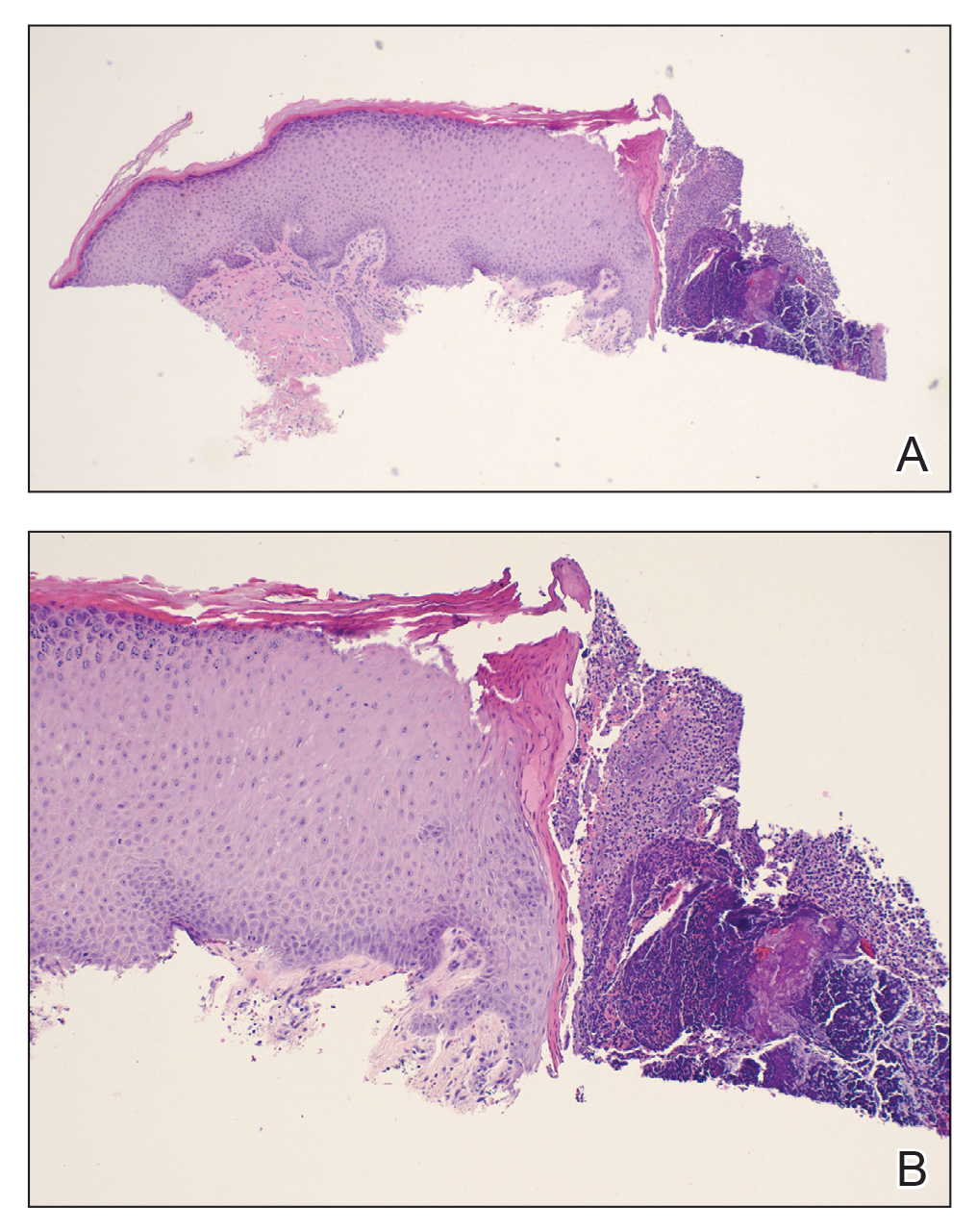

A papule with the central plug removed left a pitlike depression, representing Kyrle disease (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the left forearm revealed epidermal hyperplasia (Figure 2A) surrounding a keratin plug that contained degenerated basophilic material (Figure 2B), confirming the diagnosis of acquired perforating disorder of renal disease (APDRD), classically described as Kyrle disease.

Acquired perforating disorder of renal disease is an uncommon condition in the general population. It is associated with systemic disease, commonly diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure, and is seen in up to 10% patients receiving hemodialysis.1 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of APDRD remains unknown. It has been proposed to be a variant of prurigo nodularis, representing end-stage excoriated folliculitis.1 Given that most cases appear in patients with systemic disease and metabolic abnormalities, APDRD also has been classified under the spectrum of acquired perforating dermatoses, a group of disorders defined by transepithelial elimination of dermal connective tissue. Elevated levels of serum and tissue fibronectin, uremia, and hyperphosphatemia have been observed in patients with APDRD.1,2 Fibronectin stimulates epithelial migration and proliferation and may lead to expulsion of keratin. Furthermore, dermal deposition of excess urea and/or phosphate could initiate transepithelial elimination of material. Alternative hypotheses implicate abnormal keratinization or an imbalance between the rates of epidermal proliferation/ differentiation and keratin production, whereby keratin production outpaces the former. Keratin deposited within the dermis subsequently elicits an inflammatory response along with alterations in the local dermis and connective tissue. These components become intermixed and are extruded through the plug opening.3 Lastly, immune dysregulation resulting from systemic disease could contribute to APDRD through increased expression of IL-31, a cytokine thought to play a role in several pruritic inflammatory skin diseases.4

Although standardized treatment guidelines for APDRD have not been established, the mainstay of therapy is control of the underlying systemic disorder. Intense pruritus and repeated scratching may contribute to microtrauma and subsequent koebnerization of new lesions.3 Thus, ameliorating pruritus can provide both symptomatic relief and prevent the development of new lesions. Retinoids, UV light, oral antibiotics, antihistamines, corticosteroids, keratolytic agents, and immunosuppressants (eg, allopurinol, tacrolimus) have shown some benefit.4

The differential diagnoses for APDRD include arthropod hypersensitivity reactions, eruptive keratoacanthomas, keratosis pilaris, and prurigo nodularis. Arthropod hypersensitivity reactions are seen in patients with a history of a bite or sting from arthropods such as bees, fleas, mites, ticks, and spiders. These reactions cause symptoms of pain, burning, or pruritus and present heterogeneously. They can be edematous and appear as single or multiple papules, pustules, plaques, vesicles, and/or bullae. A central punctum or crusting also may be present. Eruptive keratoacanthomas are seen in Grzybowski syndrome and Ferguson-Smith disease. Grzybowski syndrome arises in the fifth to seventh decades of life and is characterized by the eruptive onset of hundreds to thousands of pruritic, dome-shaped, follicular papules with or without central keratin plugs. Ectropion, mucosal lesions, and masklike facies are other clinical characteristics of Grzybowski syndrome. Ferguson-Smith disease begins in the second decade of life. The eruption of multiple keratoacanthomas and/or squamous cell carcinomas occurs in crops, rapidly growing over 2 to 4 weeks, and then self-resolves. This disease is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and is associated with chromosome 9q22. Keratosis pilaris is a benign condition of follicular hyperkeratosis that can appear in any age group and usually is absent of symptoms. It is not associated with any systemic disease. Clinically, the condition appears as folliculocentric keratotic papules with varying degrees of perifollicular erythema located along the extensor surfaces. Keratosis pilaris and APDRD share features of a follicular hyperkeratosis and dilated infundibulum; however, perforation is absent in keratosis pilaris. Lastly, prurigo nodularis is another intensely pruritic dermatosis associated with renal disease that presents as papulonodules on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. A biopsy can help to distinguish prurigo nodularis from APDRD.

- Rice AS, Zedek D. Kyrle disease. StatPearls [internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532886/

- McKinley-Grant L, Peebles J. Renal disease. In: Kelly A, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2016

- Patterson JW. The perforating disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:561-581. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80259-5

- Forouzandeh M, Stratman S, Yosipovitch G. The treatment of Kyrle’s disease: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1457-1463. doi:10.1111/jdv.16182

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Acquired Perforating Disorder of Renal Disease

A papule with the central plug removed left a pitlike depression, representing Kyrle disease (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the left forearm revealed epidermal hyperplasia (Figure 2A) surrounding a keratin plug that contained degenerated basophilic material (Figure 2B), confirming the diagnosis of acquired perforating disorder of renal disease (APDRD), classically described as Kyrle disease.

Acquired perforating disorder of renal disease is an uncommon condition in the general population. It is associated with systemic disease, commonly diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure, and is seen in up to 10% patients receiving hemodialysis.1 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of APDRD remains unknown. It has been proposed to be a variant of prurigo nodularis, representing end-stage excoriated folliculitis.1 Given that most cases appear in patients with systemic disease and metabolic abnormalities, APDRD also has been classified under the spectrum of acquired perforating dermatoses, a group of disorders defined by transepithelial elimination of dermal connective tissue. Elevated levels of serum and tissue fibronectin, uremia, and hyperphosphatemia have been observed in patients with APDRD.1,2 Fibronectin stimulates epithelial migration and proliferation and may lead to expulsion of keratin. Furthermore, dermal deposition of excess urea and/or phosphate could initiate transepithelial elimination of material. Alternative hypotheses implicate abnormal keratinization or an imbalance between the rates of epidermal proliferation/ differentiation and keratin production, whereby keratin production outpaces the former. Keratin deposited within the dermis subsequently elicits an inflammatory response along with alterations in the local dermis and connective tissue. These components become intermixed and are extruded through the plug opening.3 Lastly, immune dysregulation resulting from systemic disease could contribute to APDRD through increased expression of IL-31, a cytokine thought to play a role in several pruritic inflammatory skin diseases.4

Although standardized treatment guidelines for APDRD have not been established, the mainstay of therapy is control of the underlying systemic disorder. Intense pruritus and repeated scratching may contribute to microtrauma and subsequent koebnerization of new lesions.3 Thus, ameliorating pruritus can provide both symptomatic relief and prevent the development of new lesions. Retinoids, UV light, oral antibiotics, antihistamines, corticosteroids, keratolytic agents, and immunosuppressants (eg, allopurinol, tacrolimus) have shown some benefit.4

The differential diagnoses for APDRD include arthropod hypersensitivity reactions, eruptive keratoacanthomas, keratosis pilaris, and prurigo nodularis. Arthropod hypersensitivity reactions are seen in patients with a history of a bite or sting from arthropods such as bees, fleas, mites, ticks, and spiders. These reactions cause symptoms of pain, burning, or pruritus and present heterogeneously. They can be edematous and appear as single or multiple papules, pustules, plaques, vesicles, and/or bullae. A central punctum or crusting also may be present. Eruptive keratoacanthomas are seen in Grzybowski syndrome and Ferguson-Smith disease. Grzybowski syndrome arises in the fifth to seventh decades of life and is characterized by the eruptive onset of hundreds to thousands of pruritic, dome-shaped, follicular papules with or without central keratin plugs. Ectropion, mucosal lesions, and masklike facies are other clinical characteristics of Grzybowski syndrome. Ferguson-Smith disease begins in the second decade of life. The eruption of multiple keratoacanthomas and/or squamous cell carcinomas occurs in crops, rapidly growing over 2 to 4 weeks, and then self-resolves. This disease is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and is associated with chromosome 9q22. Keratosis pilaris is a benign condition of follicular hyperkeratosis that can appear in any age group and usually is absent of symptoms. It is not associated with any systemic disease. Clinically, the condition appears as folliculocentric keratotic papules with varying degrees of perifollicular erythema located along the extensor surfaces. Keratosis pilaris and APDRD share features of a follicular hyperkeratosis and dilated infundibulum; however, perforation is absent in keratosis pilaris. Lastly, prurigo nodularis is another intensely pruritic dermatosis associated with renal disease that presents as papulonodules on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. A biopsy can help to distinguish prurigo nodularis from APDRD.

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Acquired Perforating Disorder of Renal Disease

A papule with the central plug removed left a pitlike depression, representing Kyrle disease (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the left forearm revealed epidermal hyperplasia (Figure 2A) surrounding a keratin plug that contained degenerated basophilic material (Figure 2B), confirming the diagnosis of acquired perforating disorder of renal disease (APDRD), classically described as Kyrle disease.

Acquired perforating disorder of renal disease is an uncommon condition in the general population. It is associated with systemic disease, commonly diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure, and is seen in up to 10% patients receiving hemodialysis.1 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of APDRD remains unknown. It has been proposed to be a variant of prurigo nodularis, representing end-stage excoriated folliculitis.1 Given that most cases appear in patients with systemic disease and metabolic abnormalities, APDRD also has been classified under the spectrum of acquired perforating dermatoses, a group of disorders defined by transepithelial elimination of dermal connective tissue. Elevated levels of serum and tissue fibronectin, uremia, and hyperphosphatemia have been observed in patients with APDRD.1,2 Fibronectin stimulates epithelial migration and proliferation and may lead to expulsion of keratin. Furthermore, dermal deposition of excess urea and/or phosphate could initiate transepithelial elimination of material. Alternative hypotheses implicate abnormal keratinization or an imbalance between the rates of epidermal proliferation/ differentiation and keratin production, whereby keratin production outpaces the former. Keratin deposited within the dermis subsequently elicits an inflammatory response along with alterations in the local dermis and connective tissue. These components become intermixed and are extruded through the plug opening.3 Lastly, immune dysregulation resulting from systemic disease could contribute to APDRD through increased expression of IL-31, a cytokine thought to play a role in several pruritic inflammatory skin diseases.4

Although standardized treatment guidelines for APDRD have not been established, the mainstay of therapy is control of the underlying systemic disorder. Intense pruritus and repeated scratching may contribute to microtrauma and subsequent koebnerization of new lesions.3 Thus, ameliorating pruritus can provide both symptomatic relief and prevent the development of new lesions. Retinoids, UV light, oral antibiotics, antihistamines, corticosteroids, keratolytic agents, and immunosuppressants (eg, allopurinol, tacrolimus) have shown some benefit.4

The differential diagnoses for APDRD include arthropod hypersensitivity reactions, eruptive keratoacanthomas, keratosis pilaris, and prurigo nodularis. Arthropod hypersensitivity reactions are seen in patients with a history of a bite or sting from arthropods such as bees, fleas, mites, ticks, and spiders. These reactions cause symptoms of pain, burning, or pruritus and present heterogeneously. They can be edematous and appear as single or multiple papules, pustules, plaques, vesicles, and/or bullae. A central punctum or crusting also may be present. Eruptive keratoacanthomas are seen in Grzybowski syndrome and Ferguson-Smith disease. Grzybowski syndrome arises in the fifth to seventh decades of life and is characterized by the eruptive onset of hundreds to thousands of pruritic, dome-shaped, follicular papules with or without central keratin plugs. Ectropion, mucosal lesions, and masklike facies are other clinical characteristics of Grzybowski syndrome. Ferguson-Smith disease begins in the second decade of life. The eruption of multiple keratoacanthomas and/or squamous cell carcinomas occurs in crops, rapidly growing over 2 to 4 weeks, and then self-resolves. This disease is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and is associated with chromosome 9q22. Keratosis pilaris is a benign condition of follicular hyperkeratosis that can appear in any age group and usually is absent of symptoms. It is not associated with any systemic disease. Clinically, the condition appears as folliculocentric keratotic papules with varying degrees of perifollicular erythema located along the extensor surfaces. Keratosis pilaris and APDRD share features of a follicular hyperkeratosis and dilated infundibulum; however, perforation is absent in keratosis pilaris. Lastly, prurigo nodularis is another intensely pruritic dermatosis associated with renal disease that presents as papulonodules on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. A biopsy can help to distinguish prurigo nodularis from APDRD.

- Rice AS, Zedek D. Kyrle disease. StatPearls [internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532886/

- McKinley-Grant L, Peebles J. Renal disease. In: Kelly A, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2016

- Patterson JW. The perforating disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:561-581. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80259-5

- Forouzandeh M, Stratman S, Yosipovitch G. The treatment of Kyrle’s disease: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1457-1463. doi:10.1111/jdv.16182

- Rice AS, Zedek D. Kyrle disease. StatPearls [internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532886/

- McKinley-Grant L, Peebles J. Renal disease. In: Kelly A, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2016

- Patterson JW. The perforating disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:561-581. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80259-5

- Forouzandeh M, Stratman S, Yosipovitch G. The treatment of Kyrle’s disease: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1457-1463. doi:10.1111/jdv.16182

A 74-year-old woman with a 30-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic eruption on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 months’ duration. Several over-the-counter moisturizers had been used without improvement, and the pruritus was notably impacting her sleep. Physical examination revealed discrete, hyperkeratotic, predominantly follicular, eruptive papules with hyperkeratotic plugs diffusely distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs.

Zosteriform Eruption on the Chest and Abdomen

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Cutaneous Metastatic Mesothelioma

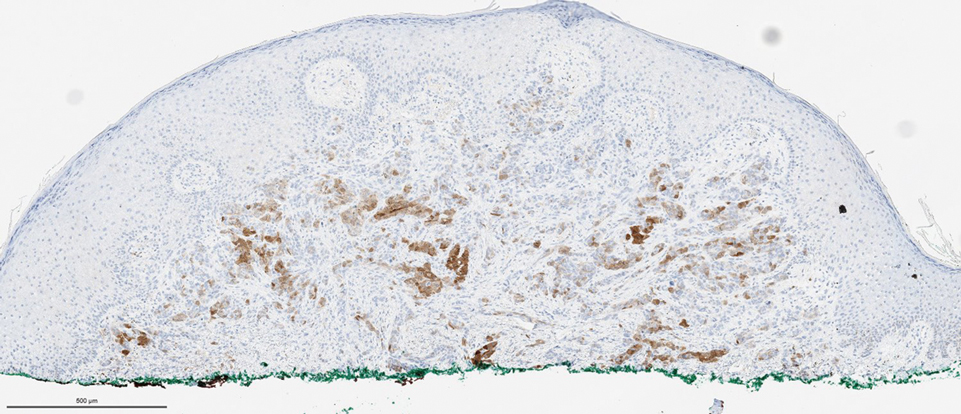

Biopsies of the larger erythematous papules revealed an infiltrate of atypical tumor cells with mitoses (Figure 1) that were immunoreactive for calretinin (Figure 2) and lacked nuclear BRCA1 associated protein-1, BAP1, expression (not shown). The patient’s prior mesothelioma was re-reviewed, and the cutaneous tumor cells were similar to the primary mesothelioma. A diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic mesothelioma (CMM) was made.

Mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm arising from the pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, and tunica vaginalis,1 with an estimated annual incidence of 2500 cases.2 The predominant risk factor for the development of pleural mesothelioma is asbestos exposure, which has been identified in up to 90% of cases. Mesothelioma can give rise to local and less frequently distant hematogenous metastases. Cutaneous involvement of mesothelioma is rare.3 More than 80% of CMM cases are attributed to seeding the skin at procedure sites or by direct infiltration of scars. Distant CMM is rare and typically presents as subcutaneous nodules.4 Few cases of inflammatory CMM have been published,1,4,5 with even fewer mimicking herpes zoster infection (HZI), as seen in our patient.

The most specific stain for mesothelioma is calretinin, which strongly and diffusely stains both the nucleus and cytoplasm. Other markers include Wilms tumor 1, cytokeratin 5/6, thrombomodulin, and HBME-1. Immunohistochemistry to detect the loss of BAP1 staining in the nucleus is important for differentiating between mesothelioma and mesothelial hyperplasia.3

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.7% to 9% of patients with internal malignant disease. Most commonly, cutaneous metastases present as cutaneous nodules, though other reported inflammatory presentations include erysipeloides, generalized erythematous patches, telangiectasia, and zosteriform distributions.6 Zosteriform distributions are particularly rare and most commonly are due to breast carcinomas or lymphomas. The mechanism of zosteriform metastasis is unknown, but theories include tumoral spread along vessels, invasion of the thoracic perineural sheaths, localized spread of tumor cells from a surgical site, or a Koebner-like reaction at the site of an existing HZI. Regardless of primary tumor type or presentation, cutaneous metastasis is a poor prognostic sign, with survival rates varying based on primary tumor type.7

Other differential diagnoses include herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis, radiation recall dermatitis, cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease, and zosteriform lichen planus, all of which have been reported after HZI.8-10 Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis typically presents weeks to years after acute HZI with erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques at the site of the prior HZI. A biopsy reveals interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and multinucleated giant cells.8 Radiation recall dermatitis is a cutaneous inflammatory reaction limited to regions of prior radiation exposure after the administration of a triggering medication. Radiation recall dermatitis can present days to many years after the completion of treatment.9 Although the eruption in our patient was at the site of prior radiation, the pathologic and clinical presentation was not consistent with radiation recall dermatitis. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that may present as either solitary or numerous papules, plaques, or nodules and has been reported to occur after HZI. Biopsy reveals a diffuse dermal histiocytic infiltration with plasma cells and lymphocytes. In contrast to metastatic disease, mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare in cutaneous RosaiDorfman disease.11 Lichen planus is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology presenting as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic papules12 that may present in a zosteriform pattern.13

Although it is uncommon, metastatic spread should be considered in patients with known malignancy presenting with zosteriform eruptions.2 Our patient remained on treatment with immunotherapy, as he was unable to undergo additional radiation and had failed multiple other lines of therapy. He died 3 months after presentation.

- Klebanov N, Reddy BY, Husain S, et al. Cutaneous presentation of mesothelioma with a sarcomatoid transformation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:378-382.

- Patel SC, Dowell JE. Modern management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer (Auckl). 2016;7:63-72.

- Ward RE, Ali SA, Kuhar M. Epithelioid malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:1057-1063.

- Prieto VG, Kenet BJ, Varghese M. Malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin, presenting as inflammatory carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:261-265.

- Gaudy-Marqueste C, Dales JP, Collet-Villette AM, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of pleural mesothelioma: two cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:455-459.

- Chiang A, Salomon N, Gaikwad R, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis mimicking herpes zoster rash. IDCases. 2018;12:167-168.

- Thomaidou E, Armon G, Klapholz L, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:734-736.

- Ferenczi K, Rosenberg AS, McCalmont TH, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis: histopathologic findings in a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:739-745.

- Carrasco L, Pastor MA, Izquierdo MJ, et al. Drug eruption secondary to acyclovir with recall phenomenon in a dermatome previously affected by herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:132-134.

- Malviya N, Marzuka A, Maamed-Tayeb M, et al. Cutaneous involvement of pre-existing Rosai-Dorfman disease via post-herpetic isotopic response. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1211-1214.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Fink-Puches R, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Smolle J. Zosteriform lichen planus. Dermatology. 1996;192:375-377.

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Cutaneous Metastatic Mesothelioma

Biopsies of the larger erythematous papules revealed an infiltrate of atypical tumor cells with mitoses (Figure 1) that were immunoreactive for calretinin (Figure 2) and lacked nuclear BRCA1 associated protein-1, BAP1, expression (not shown). The patient’s prior mesothelioma was re-reviewed, and the cutaneous tumor cells were similar to the primary mesothelioma. A diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic mesothelioma (CMM) was made.

Mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm arising from the pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, and tunica vaginalis,1 with an estimated annual incidence of 2500 cases.2 The predominant risk factor for the development of pleural mesothelioma is asbestos exposure, which has been identified in up to 90% of cases. Mesothelioma can give rise to local and less frequently distant hematogenous metastases. Cutaneous involvement of mesothelioma is rare.3 More than 80% of CMM cases are attributed to seeding the skin at procedure sites or by direct infiltration of scars. Distant CMM is rare and typically presents as subcutaneous nodules.4 Few cases of inflammatory CMM have been published,1,4,5 with even fewer mimicking herpes zoster infection (HZI), as seen in our patient.