User login

Linear Violaceous Papules in a Child

The Diagnosis: Linear Lichen Planus

The patient was clinically diagnosed with linear lichen planus and was started on betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% applied once daily with improvement in both the pruritus and appearance at 4-month follow-up. A biopsy was deferred based on the parents’ wishes.

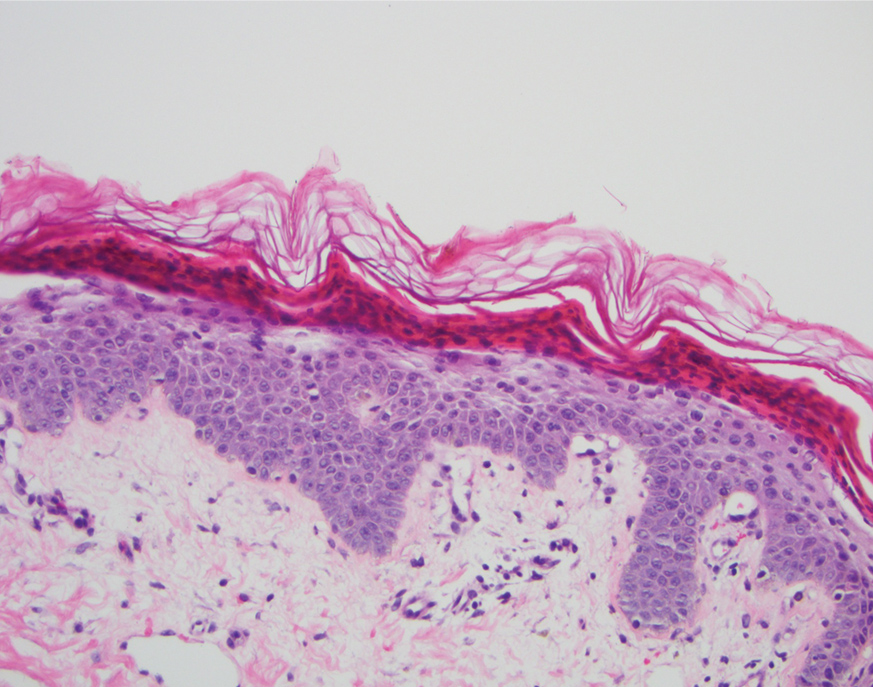

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder involving the skin and oral mucosa. Cutaneous lichen planus classically presents as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic, polygonal papules with overlying fine white or grey lines known as Wickham striae.1 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common, especially in patients with darker skin tones. Expected histologic findings include orthokeratosis, apoptotic keratinocytes, and bandlike lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction.1

An estimated 5% of cases of cutaneous lichen planus occur in children.2 A study of 316 children with lichen planus demonstrated that the classic morphology remained the most common presentation, while the linear variant was present in only 6.9% of pediatric cases.3 Linear lichen planus appears to be more common among children than adults. A study of 36 pediatric cases showed a greater representation of lichen planus in Black children (67% affected vs 21% cohort).2

Cutaneous lichen planus often clears spontaneously in approximately 1 year.4 Treatment in children primarily is focused on shortening the time to resolution and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids as firstline therapy.3,4 Oral corticosteroids have a faster clinical response; greater efficacy; and more effectively prevent residual hyperpigmentation, which is especially relevant in individuals with darker skin.3 Nonetheless, oral corticosteroids are considered a second-line treatment due to their unfavorable side-effect profile. Additional treatment options include oral aromatic retinoids (acitretin) and phototherapy.3

Incontinentia pigmenti is characterized by a defect in the inhibitor of nuclear factor–κB kinase regulatory subunit gamma, IKBKG, gene on the X chromosome. Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males; in females, it leads to ectodermal dysplasia associated with skin findings in a blaschkoid distribution occurring in 4 stages.5 The verrucous stage is preceded by the vesicular stage and expected to occur within the first few months of life, making it unlikely in our 5-year-old patient. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually occurs in children younger than 5 years and is characterized by psoriasiform papules coalescing into a plaque with substantial scale instead of Wickham striae, as seen in our patient.6 Lichen striatus consists of smaller, pink to flesh-colored papules that rarely are pruritic.7 It is more common among atopic individuals and is associated with postinflammatory hypopigmentation.8 Linear psoriasis presents similarly to inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, with greater erythema and scale compared to the fine lacy Wickham striae that were seen in our patient.8

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Walton KE, Bowers EV, Drolet BA, et al. Childhood lichen planus: demographics of a U.S. population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-38.

- Pandhi D, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN. Lichen planus in childhood: a series of 316 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:59-67.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:E45-E52.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell CJ. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Payette MJ, Weston G, Humphrey S, et al. Lichen planus and other lichenoid dermatoses: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:631-643.

- Moss C, Browne F. Mosaicism and linear lesions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

The Diagnosis: Linear Lichen Planus

The patient was clinically diagnosed with linear lichen planus and was started on betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% applied once daily with improvement in both the pruritus and appearance at 4-month follow-up. A biopsy was deferred based on the parents’ wishes.

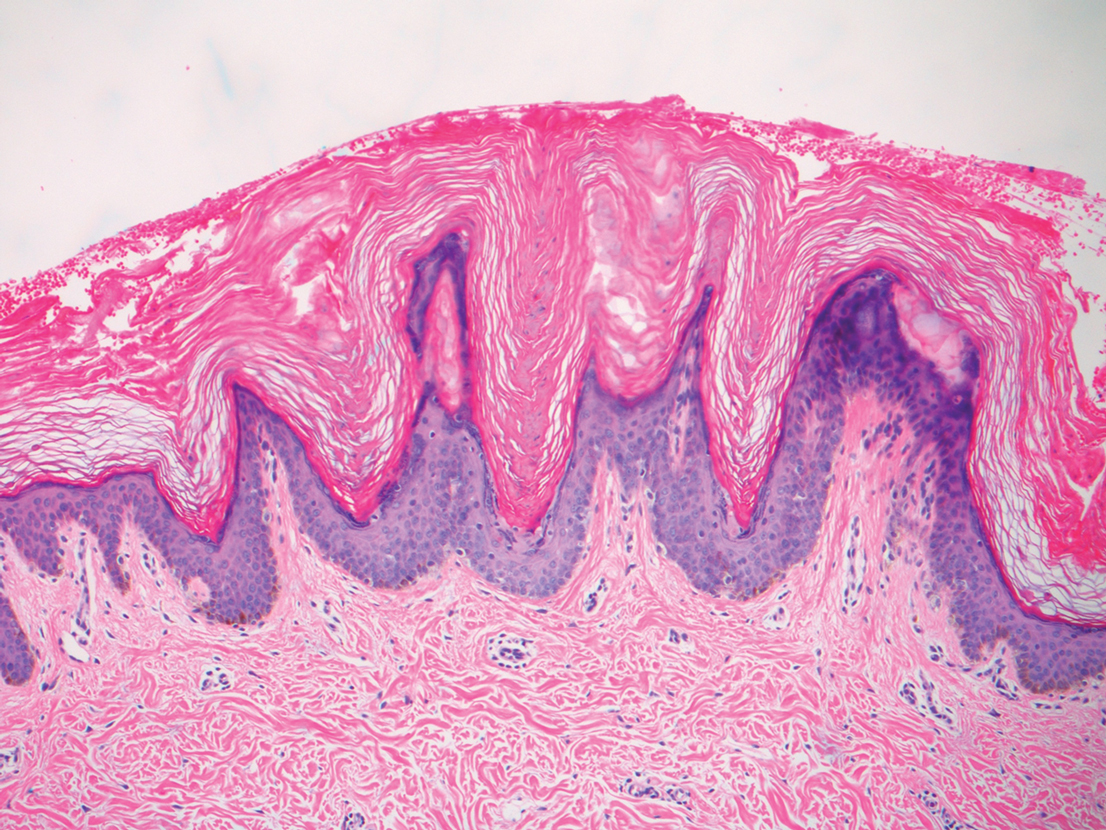

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder involving the skin and oral mucosa. Cutaneous lichen planus classically presents as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic, polygonal papules with overlying fine white or grey lines known as Wickham striae.1 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common, especially in patients with darker skin tones. Expected histologic findings include orthokeratosis, apoptotic keratinocytes, and bandlike lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction.1

An estimated 5% of cases of cutaneous lichen planus occur in children.2 A study of 316 children with lichen planus demonstrated that the classic morphology remained the most common presentation, while the linear variant was present in only 6.9% of pediatric cases.3 Linear lichen planus appears to be more common among children than adults. A study of 36 pediatric cases showed a greater representation of lichen planus in Black children (67% affected vs 21% cohort).2

Cutaneous lichen planus often clears spontaneously in approximately 1 year.4 Treatment in children primarily is focused on shortening the time to resolution and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids as firstline therapy.3,4 Oral corticosteroids have a faster clinical response; greater efficacy; and more effectively prevent residual hyperpigmentation, which is especially relevant in individuals with darker skin.3 Nonetheless, oral corticosteroids are considered a second-line treatment due to their unfavorable side-effect profile. Additional treatment options include oral aromatic retinoids (acitretin) and phototherapy.3

Incontinentia pigmenti is characterized by a defect in the inhibitor of nuclear factor–κB kinase regulatory subunit gamma, IKBKG, gene on the X chromosome. Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males; in females, it leads to ectodermal dysplasia associated with skin findings in a blaschkoid distribution occurring in 4 stages.5 The verrucous stage is preceded by the vesicular stage and expected to occur within the first few months of life, making it unlikely in our 5-year-old patient. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually occurs in children younger than 5 years and is characterized by psoriasiform papules coalescing into a plaque with substantial scale instead of Wickham striae, as seen in our patient.6 Lichen striatus consists of smaller, pink to flesh-colored papules that rarely are pruritic.7 It is more common among atopic individuals and is associated with postinflammatory hypopigmentation.8 Linear psoriasis presents similarly to inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, with greater erythema and scale compared to the fine lacy Wickham striae that were seen in our patient.8

The Diagnosis: Linear Lichen Planus

The patient was clinically diagnosed with linear lichen planus and was started on betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% applied once daily with improvement in both the pruritus and appearance at 4-month follow-up. A biopsy was deferred based on the parents’ wishes.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder involving the skin and oral mucosa. Cutaneous lichen planus classically presents as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic, polygonal papules with overlying fine white or grey lines known as Wickham striae.1 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common, especially in patients with darker skin tones. Expected histologic findings include orthokeratosis, apoptotic keratinocytes, and bandlike lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction.1

An estimated 5% of cases of cutaneous lichen planus occur in children.2 A study of 316 children with lichen planus demonstrated that the classic morphology remained the most common presentation, while the linear variant was present in only 6.9% of pediatric cases.3 Linear lichen planus appears to be more common among children than adults. A study of 36 pediatric cases showed a greater representation of lichen planus in Black children (67% affected vs 21% cohort).2

Cutaneous lichen planus often clears spontaneously in approximately 1 year.4 Treatment in children primarily is focused on shortening the time to resolution and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids as firstline therapy.3,4 Oral corticosteroids have a faster clinical response; greater efficacy; and more effectively prevent residual hyperpigmentation, which is especially relevant in individuals with darker skin.3 Nonetheless, oral corticosteroids are considered a second-line treatment due to their unfavorable side-effect profile. Additional treatment options include oral aromatic retinoids (acitretin) and phototherapy.3

Incontinentia pigmenti is characterized by a defect in the inhibitor of nuclear factor–κB kinase regulatory subunit gamma, IKBKG, gene on the X chromosome. Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males; in females, it leads to ectodermal dysplasia associated with skin findings in a blaschkoid distribution occurring in 4 stages.5 The verrucous stage is preceded by the vesicular stage and expected to occur within the first few months of life, making it unlikely in our 5-year-old patient. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually occurs in children younger than 5 years and is characterized by psoriasiform papules coalescing into a plaque with substantial scale instead of Wickham striae, as seen in our patient.6 Lichen striatus consists of smaller, pink to flesh-colored papules that rarely are pruritic.7 It is more common among atopic individuals and is associated with postinflammatory hypopigmentation.8 Linear psoriasis presents similarly to inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, with greater erythema and scale compared to the fine lacy Wickham striae that were seen in our patient.8

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Walton KE, Bowers EV, Drolet BA, et al. Childhood lichen planus: demographics of a U.S. population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-38.

- Pandhi D, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN. Lichen planus in childhood: a series of 316 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:59-67.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:E45-E52.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell CJ. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Payette MJ, Weston G, Humphrey S, et al. Lichen planus and other lichenoid dermatoses: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:631-643.

- Moss C, Browne F. Mosaicism and linear lesions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Walton KE, Bowers EV, Drolet BA, et al. Childhood lichen planus: demographics of a U.S. population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-38.

- Pandhi D, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN. Lichen planus in childhood: a series of 316 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:59-67.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:E45-E52.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell CJ. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Payette MJ, Weston G, Humphrey S, et al. Lichen planus and other lichenoid dermatoses: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:631-643.

- Moss C, Browne F. Mosaicism and linear lesions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

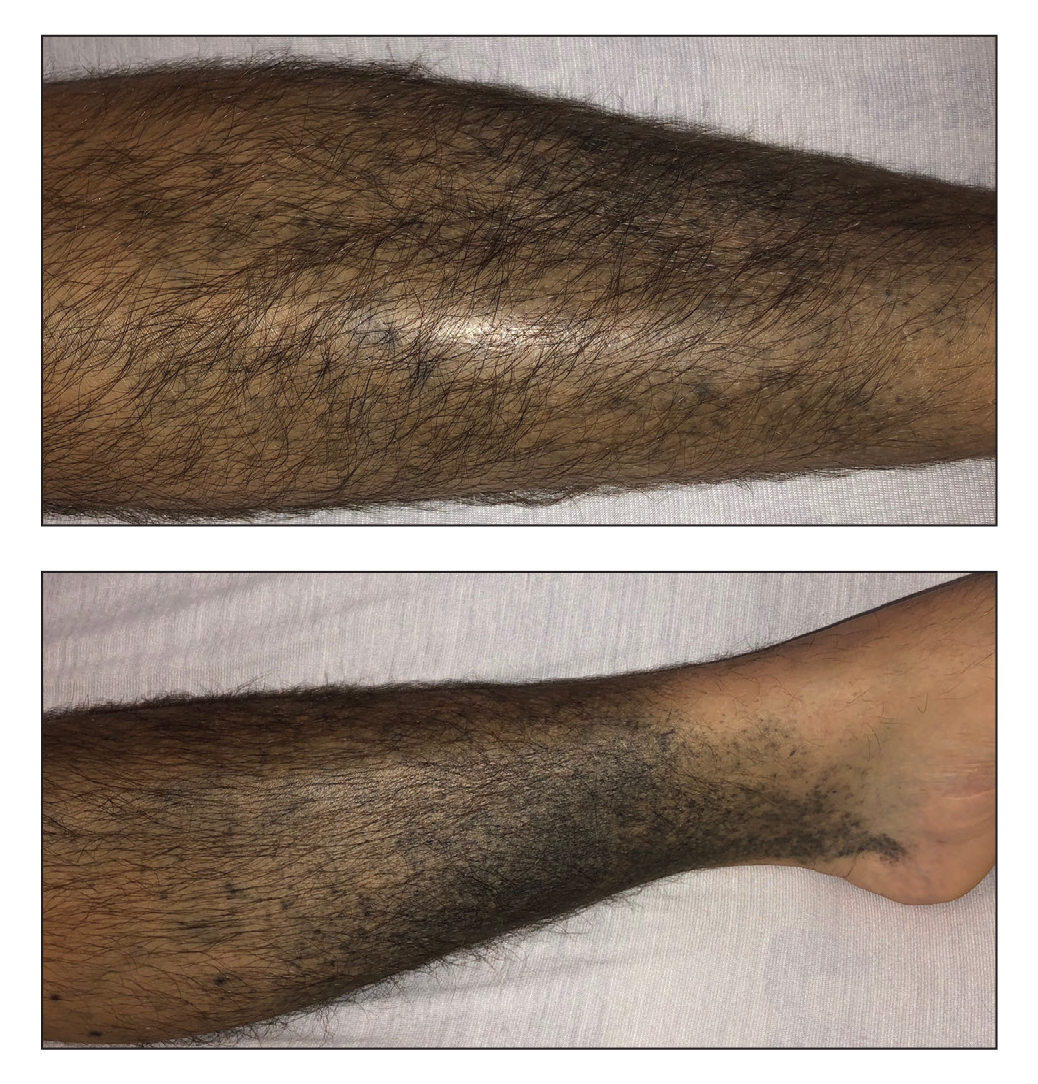

A 5-year-old Black girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a stable pruritic eruption on the right leg of 1 month’s duration. Over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream was applied for 3 days with no response. Physical examination revealed grouped, flat-topped, violaceous papules coalescing into plaques with overlying lacy white striae along the right lower leg, wrapping around to the right dorsal foot in a blaschkoid distribution. The patient was otherwise healthy and up-to-date on immunizations and had an unremarkable birth history.

Ulcer on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Calcinosis Cutis Due to Systemic Sclerosis Sine Scleroderma

Laboratory evaluation was notable for high titers of antinuclear antibodies (>1/320; reference range, 0–1/80) and positive anticentromere antibodies. There were no other relevant laboratory findings; phosphocalcic metabolism was within normal limits, and urinary sediment was normal. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer revealed basophilic material compatible with calcium deposits. In a 3D volume rendering reconstruction from the lower limb scanner, grouped calcifications were observed in subcutaneous cellular tissue near the ulcer (Figure). The patient had a restrictive ventilatory pattern observed in a pulmonary function test. An esophageal motility study was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) type II because she met the 4 criteria established by Poormoghim et al1 : (1) Raynaud phenomenon or a peripheral vascular equivalent (ie, digital pitting scars, digital-tip ulcers, digital-tip gangrene, abnormal nail fold capillaries); (2) positive antinuclear antibodies; (3) distal esophageal hypomotility, small bowel hypomotility, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (without fibrosis), cardiac involvement typical of scleroderma, or renal failure; and (4) no other defined connective tissue or other disease as a cause of the prior conditions.

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic disease characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin and other internal organs—especially the lungs, kidneys, digestive tract, and heart—as well as generalized vascular dysfunction. Cutaneous induration is its hallmark; however, up to 10% of affected patients have ssSSc.2 This entity is characterized by the total or partial absence of cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis with the occurrence of internal organ involvement and serologic abnormalities. There are 3 types of ssSSc depending on the grade of skin involvement. Type I is characterized by the lack of any typical cutaneous stigmata of the disease. Type II is without sclerodactyly but can coexist with other cutaneous findings such as calcifications, telangiectases, or pitting scars. Type III is characterized clinically by internal organ involvement, typical of systemic sclerosis, that has appeared before skin changes.2

An abnormal deposit of calcium in the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue is called calcinosis cutis. There are 5 subtypes of calcinosis cutis: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, iatrogenic, and calciphylaxis. Dystrophic skin calcifications may appear in patients with connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis or systemic sclerosis.3 Up to 25% of patients with systemic sclerosis can develop calcinosis cutis due to local tissue damage, with normal phosphocalcic metabolism.3

Calcinosis cutis is more common in patients with systemic sclerosis and positive anticentromere antibodies.4 The calcifications usually are located in areas that are subject to repeated trauma, such as the fingers or arms, though other locations have been described such as cervical, paraspinal, or on the hips.5,6 Our patient developed calcifications on both legs, which represent atypical areas for this process.

Dermatomyositis also can present with calcinosis cutis. There are 4 patterns of calcification: superficial nodulelike calcified masses; deep calcified masses; deep sheetlike calcifications within the fascial planes; and a rare, diffuse, superficial lacy and reticular calcification that involves almost the entire body surface area.7 Patients with calcinosis cutis secondary to dermatomyositis usually develop proximal muscle weakness, high titers of creatine kinase, heliotrope rash, or interstitial lung disease with specific antibodies.

Calciphylaxis is a serious disorder involving the calcification of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles and capillaries. It presents with painful cutaneous areas of necrosis.

Venous ulcers also can present with secondary dystrophic calcification due to local tissue damage. These patients usually have cutaneous signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Our patient denied prior trauma to the area; therefore, a traumatic ulcer with secondary calcification was ruled out.

The most concerning complication of calcinosis cutis is the development of ulcers, which occurred in 154 of 316 calcinoses (48.7%) in patients with systemic sclerosis and secondary calcifications.8 These ulcers can cause disabling pain or become superinfected, as in our patient.

There currently is no drug capable of removing dystrophic calcifications, but diltiazem, minocycline, or colchicine can reduce their size and prevent their progression. In the event of neurologic compromise or intractable pain, the treatment of choice is surgical removal of the calcification.9 Curettage, intralesional sodium thiosulfate, and intravenous sodium thiosulfate also have been suggested as therapeutic options.10 Antibiotic treatment was carried out in our patient, which controlled the superinfection of the ulcers. Diltiazem also was started, with stabilization of the calcium deposits without a reduction in their size.

There are few studies evaluating the presence of nondigital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Shanmugam et al11 calculated a 4% (N=249) prevalence of ulcers in the lower limbs of systemic sclerosis patients. In a study by Bohelay et al12 of 45 patients, the estimated prevalence of lower limb ulcers was 12.8%, and the etiologies consisted of 22 cases of venous insufficiency (49%), 21 cases of ischemic causes (47%), and 2 cases of other causes (4%).

We present the case of a woman with ssSSc who developed dystrophic calcinosis cutis in atypical areas with secondary ulceration and superinfection. The skin usually plays a key role in the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis, as sclerodactyly and the characteristic generalized skin induration stand out in affected individuals. Although our patient was diagnosed with ssSSc, her skin manifestations also were crucial for the diagnosis, as she had ulcers on the lower limbs.

- Poormoghim H, Lucas M, Fertig N, et al. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in forty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:444-451.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛ drek M. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:875-880.

- Valenzuela A, Baron M, Herrick AL, et al. Calcinosis is associated with digital ulcers and osteoporosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: a scleroderma clinical trials consortium study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:344-349.

- D’Aoust J, Hudson M, Tatibouet S, et al. Clinical and serologic correlates of antiPM/Scl antibodies in systemic sclerosis: a multicenter study of 763 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:1608-1615.

- Contreras I, Sallés M, Mínguez S, et al. Hard paracervical tumor in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Clin. 2014; 10:336-337.

- Meriglier E, Lafourcade F, Gombert B, et al. Giant calcinosis revealing systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:1787-1788.

- Chung CH. Calcinosis universalis in juvenile dermatomyositis [published online September 24, 2020]. Chonnam Med J. 2020;56:212-213.

- Bartoli F, Fiori G, Braschi F, et al. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: subsets, distribution and complications [published online May 30, 2016]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1610-1614.

- Jung H, Lee D, Cho J, et al. Surgical treatment of extensive tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;48:151-154.

- Badawi AH, Patel V, Warner AE, et al. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis: treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Cutis. 2020;106:E15-E17.

- Shanmugam V, Price P, Attinger C, et al. Lower extremity ulcers in systemic sclerosis: features and response to therapy [published online August 18, 2010]. Int J Rheumatol. doi:10.1155/2010/747946

- Bohelay G, Blaise S, Levy P, et al. Lower-limb ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a multicentre retrospective case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:677-682.

The Diagnosis: Calcinosis Cutis Due to Systemic Sclerosis Sine Scleroderma

Laboratory evaluation was notable for high titers of antinuclear antibodies (>1/320; reference range, 0–1/80) and positive anticentromere antibodies. There were no other relevant laboratory findings; phosphocalcic metabolism was within normal limits, and urinary sediment was normal. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer revealed basophilic material compatible with calcium deposits. In a 3D volume rendering reconstruction from the lower limb scanner, grouped calcifications were observed in subcutaneous cellular tissue near the ulcer (Figure). The patient had a restrictive ventilatory pattern observed in a pulmonary function test. An esophageal motility study was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) type II because she met the 4 criteria established by Poormoghim et al1 : (1) Raynaud phenomenon or a peripheral vascular equivalent (ie, digital pitting scars, digital-tip ulcers, digital-tip gangrene, abnormal nail fold capillaries); (2) positive antinuclear antibodies; (3) distal esophageal hypomotility, small bowel hypomotility, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (without fibrosis), cardiac involvement typical of scleroderma, or renal failure; and (4) no other defined connective tissue or other disease as a cause of the prior conditions.

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic disease characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin and other internal organs—especially the lungs, kidneys, digestive tract, and heart—as well as generalized vascular dysfunction. Cutaneous induration is its hallmark; however, up to 10% of affected patients have ssSSc.2 This entity is characterized by the total or partial absence of cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis with the occurrence of internal organ involvement and serologic abnormalities. There are 3 types of ssSSc depending on the grade of skin involvement. Type I is characterized by the lack of any typical cutaneous stigmata of the disease. Type II is without sclerodactyly but can coexist with other cutaneous findings such as calcifications, telangiectases, or pitting scars. Type III is characterized clinically by internal organ involvement, typical of systemic sclerosis, that has appeared before skin changes.2

An abnormal deposit of calcium in the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue is called calcinosis cutis. There are 5 subtypes of calcinosis cutis: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, iatrogenic, and calciphylaxis. Dystrophic skin calcifications may appear in patients with connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis or systemic sclerosis.3 Up to 25% of patients with systemic sclerosis can develop calcinosis cutis due to local tissue damage, with normal phosphocalcic metabolism.3

Calcinosis cutis is more common in patients with systemic sclerosis and positive anticentromere antibodies.4 The calcifications usually are located in areas that are subject to repeated trauma, such as the fingers or arms, though other locations have been described such as cervical, paraspinal, or on the hips.5,6 Our patient developed calcifications on both legs, which represent atypical areas for this process.

Dermatomyositis also can present with calcinosis cutis. There are 4 patterns of calcification: superficial nodulelike calcified masses; deep calcified masses; deep sheetlike calcifications within the fascial planes; and a rare, diffuse, superficial lacy and reticular calcification that involves almost the entire body surface area.7 Patients with calcinosis cutis secondary to dermatomyositis usually develop proximal muscle weakness, high titers of creatine kinase, heliotrope rash, or interstitial lung disease with specific antibodies.

Calciphylaxis is a serious disorder involving the calcification of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles and capillaries. It presents with painful cutaneous areas of necrosis.

Venous ulcers also can present with secondary dystrophic calcification due to local tissue damage. These patients usually have cutaneous signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Our patient denied prior trauma to the area; therefore, a traumatic ulcer with secondary calcification was ruled out.

The most concerning complication of calcinosis cutis is the development of ulcers, which occurred in 154 of 316 calcinoses (48.7%) in patients with systemic sclerosis and secondary calcifications.8 These ulcers can cause disabling pain or become superinfected, as in our patient.

There currently is no drug capable of removing dystrophic calcifications, but diltiazem, minocycline, or colchicine can reduce their size and prevent their progression. In the event of neurologic compromise or intractable pain, the treatment of choice is surgical removal of the calcification.9 Curettage, intralesional sodium thiosulfate, and intravenous sodium thiosulfate also have been suggested as therapeutic options.10 Antibiotic treatment was carried out in our patient, which controlled the superinfection of the ulcers. Diltiazem also was started, with stabilization of the calcium deposits without a reduction in their size.

There are few studies evaluating the presence of nondigital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Shanmugam et al11 calculated a 4% (N=249) prevalence of ulcers in the lower limbs of systemic sclerosis patients. In a study by Bohelay et al12 of 45 patients, the estimated prevalence of lower limb ulcers was 12.8%, and the etiologies consisted of 22 cases of venous insufficiency (49%), 21 cases of ischemic causes (47%), and 2 cases of other causes (4%).

We present the case of a woman with ssSSc who developed dystrophic calcinosis cutis in atypical areas with secondary ulceration and superinfection. The skin usually plays a key role in the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis, as sclerodactyly and the characteristic generalized skin induration stand out in affected individuals. Although our patient was diagnosed with ssSSc, her skin manifestations also were crucial for the diagnosis, as she had ulcers on the lower limbs.

The Diagnosis: Calcinosis Cutis Due to Systemic Sclerosis Sine Scleroderma

Laboratory evaluation was notable for high titers of antinuclear antibodies (>1/320; reference range, 0–1/80) and positive anticentromere antibodies. There were no other relevant laboratory findings; phosphocalcic metabolism was within normal limits, and urinary sediment was normal. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer revealed basophilic material compatible with calcium deposits. In a 3D volume rendering reconstruction from the lower limb scanner, grouped calcifications were observed in subcutaneous cellular tissue near the ulcer (Figure). The patient had a restrictive ventilatory pattern observed in a pulmonary function test. An esophageal motility study was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) type II because she met the 4 criteria established by Poormoghim et al1 : (1) Raynaud phenomenon or a peripheral vascular equivalent (ie, digital pitting scars, digital-tip ulcers, digital-tip gangrene, abnormal nail fold capillaries); (2) positive antinuclear antibodies; (3) distal esophageal hypomotility, small bowel hypomotility, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (without fibrosis), cardiac involvement typical of scleroderma, or renal failure; and (4) no other defined connective tissue or other disease as a cause of the prior conditions.

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic disease characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin and other internal organs—especially the lungs, kidneys, digestive tract, and heart—as well as generalized vascular dysfunction. Cutaneous induration is its hallmark; however, up to 10% of affected patients have ssSSc.2 This entity is characterized by the total or partial absence of cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis with the occurrence of internal organ involvement and serologic abnormalities. There are 3 types of ssSSc depending on the grade of skin involvement. Type I is characterized by the lack of any typical cutaneous stigmata of the disease. Type II is without sclerodactyly but can coexist with other cutaneous findings such as calcifications, telangiectases, or pitting scars. Type III is characterized clinically by internal organ involvement, typical of systemic sclerosis, that has appeared before skin changes.2

An abnormal deposit of calcium in the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue is called calcinosis cutis. There are 5 subtypes of calcinosis cutis: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, iatrogenic, and calciphylaxis. Dystrophic skin calcifications may appear in patients with connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis or systemic sclerosis.3 Up to 25% of patients with systemic sclerosis can develop calcinosis cutis due to local tissue damage, with normal phosphocalcic metabolism.3

Calcinosis cutis is more common in patients with systemic sclerosis and positive anticentromere antibodies.4 The calcifications usually are located in areas that are subject to repeated trauma, such as the fingers or arms, though other locations have been described such as cervical, paraspinal, or on the hips.5,6 Our patient developed calcifications on both legs, which represent atypical areas for this process.

Dermatomyositis also can present with calcinosis cutis. There are 4 patterns of calcification: superficial nodulelike calcified masses; deep calcified masses; deep sheetlike calcifications within the fascial planes; and a rare, diffuse, superficial lacy and reticular calcification that involves almost the entire body surface area.7 Patients with calcinosis cutis secondary to dermatomyositis usually develop proximal muscle weakness, high titers of creatine kinase, heliotrope rash, or interstitial lung disease with specific antibodies.

Calciphylaxis is a serious disorder involving the calcification of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles and capillaries. It presents with painful cutaneous areas of necrosis.

Venous ulcers also can present with secondary dystrophic calcification due to local tissue damage. These patients usually have cutaneous signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Our patient denied prior trauma to the area; therefore, a traumatic ulcer with secondary calcification was ruled out.

The most concerning complication of calcinosis cutis is the development of ulcers, which occurred in 154 of 316 calcinoses (48.7%) in patients with systemic sclerosis and secondary calcifications.8 These ulcers can cause disabling pain or become superinfected, as in our patient.

There currently is no drug capable of removing dystrophic calcifications, but diltiazem, minocycline, or colchicine can reduce their size and prevent their progression. In the event of neurologic compromise or intractable pain, the treatment of choice is surgical removal of the calcification.9 Curettage, intralesional sodium thiosulfate, and intravenous sodium thiosulfate also have been suggested as therapeutic options.10 Antibiotic treatment was carried out in our patient, which controlled the superinfection of the ulcers. Diltiazem also was started, with stabilization of the calcium deposits without a reduction in their size.

There are few studies evaluating the presence of nondigital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Shanmugam et al11 calculated a 4% (N=249) prevalence of ulcers in the lower limbs of systemic sclerosis patients. In a study by Bohelay et al12 of 45 patients, the estimated prevalence of lower limb ulcers was 12.8%, and the etiologies consisted of 22 cases of venous insufficiency (49%), 21 cases of ischemic causes (47%), and 2 cases of other causes (4%).

We present the case of a woman with ssSSc who developed dystrophic calcinosis cutis in atypical areas with secondary ulceration and superinfection. The skin usually plays a key role in the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis, as sclerodactyly and the characteristic generalized skin induration stand out in affected individuals. Although our patient was diagnosed with ssSSc, her skin manifestations also were crucial for the diagnosis, as she had ulcers on the lower limbs.

- Poormoghim H, Lucas M, Fertig N, et al. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in forty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:444-451.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛ drek M. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:875-880.

- Valenzuela A, Baron M, Herrick AL, et al. Calcinosis is associated with digital ulcers and osteoporosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: a scleroderma clinical trials consortium study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:344-349.

- D’Aoust J, Hudson M, Tatibouet S, et al. Clinical and serologic correlates of antiPM/Scl antibodies in systemic sclerosis: a multicenter study of 763 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:1608-1615.

- Contreras I, Sallés M, Mínguez S, et al. Hard paracervical tumor in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Clin. 2014; 10:336-337.

- Meriglier E, Lafourcade F, Gombert B, et al. Giant calcinosis revealing systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:1787-1788.

- Chung CH. Calcinosis universalis in juvenile dermatomyositis [published online September 24, 2020]. Chonnam Med J. 2020;56:212-213.

- Bartoli F, Fiori G, Braschi F, et al. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: subsets, distribution and complications [published online May 30, 2016]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1610-1614.

- Jung H, Lee D, Cho J, et al. Surgical treatment of extensive tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;48:151-154.

- Badawi AH, Patel V, Warner AE, et al. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis: treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Cutis. 2020;106:E15-E17.

- Shanmugam V, Price P, Attinger C, et al. Lower extremity ulcers in systemic sclerosis: features and response to therapy [published online August 18, 2010]. Int J Rheumatol. doi:10.1155/2010/747946

- Bohelay G, Blaise S, Levy P, et al. Lower-limb ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a multicentre retrospective case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:677-682.

- Poormoghim H, Lucas M, Fertig N, et al. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in forty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:444-451.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛ drek M. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:875-880.

- Valenzuela A, Baron M, Herrick AL, et al. Calcinosis is associated with digital ulcers and osteoporosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: a scleroderma clinical trials consortium study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:344-349.

- D’Aoust J, Hudson M, Tatibouet S, et al. Clinical and serologic correlates of antiPM/Scl antibodies in systemic sclerosis: a multicenter study of 763 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:1608-1615.

- Contreras I, Sallés M, Mínguez S, et al. Hard paracervical tumor in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Clin. 2014; 10:336-337.

- Meriglier E, Lafourcade F, Gombert B, et al. Giant calcinosis revealing systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:1787-1788.

- Chung CH. Calcinosis universalis in juvenile dermatomyositis [published online September 24, 2020]. Chonnam Med J. 2020;56:212-213.

- Bartoli F, Fiori G, Braschi F, et al. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: subsets, distribution and complications [published online May 30, 2016]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1610-1614.

- Jung H, Lee D, Cho J, et al. Surgical treatment of extensive tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;48:151-154.

- Badawi AH, Patel V, Warner AE, et al. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis: treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Cutis. 2020;106:E15-E17.

- Shanmugam V, Price P, Attinger C, et al. Lower extremity ulcers in systemic sclerosis: features and response to therapy [published online August 18, 2010]. Int J Rheumatol. doi:10.1155/2010/747946

- Bohelay G, Blaise S, Levy P, et al. Lower-limb ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a multicentre retrospective case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:677-682.

A 49-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, pulmonary fibrosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension presented to our hospital with an ulcer on the left leg of unknown etiology that was superinfected by multidrug-resistant Klebsiella according to bacterial culture. She had an axillary temperature of 38.6 °C. She underwent amputation of the second and third toes on the left foot 5 years prior to presentation due to distal necrotic ulcers of ischemic origin. Physical examination revealed an 8×2-cm deep ulcer with abrupt edges on the left leg with fibrin and a purulent exudate. Deep palpation of the perilesional skin revealed indurated subcutaneous nodules. She also had scars on the fingertips of both hands with no induration on the rest of the skin surface. Capillaroscopy showed no pathologic findings. Blood cultures were performed, and she was admitted to the hospital for intravenous antibiotic therapy. During ulcer debridement, some solid whitish material was released.

Flesh-Colored Papule in the Nose of a Child

The Diagnosis: Striated Muscle Hamartoma

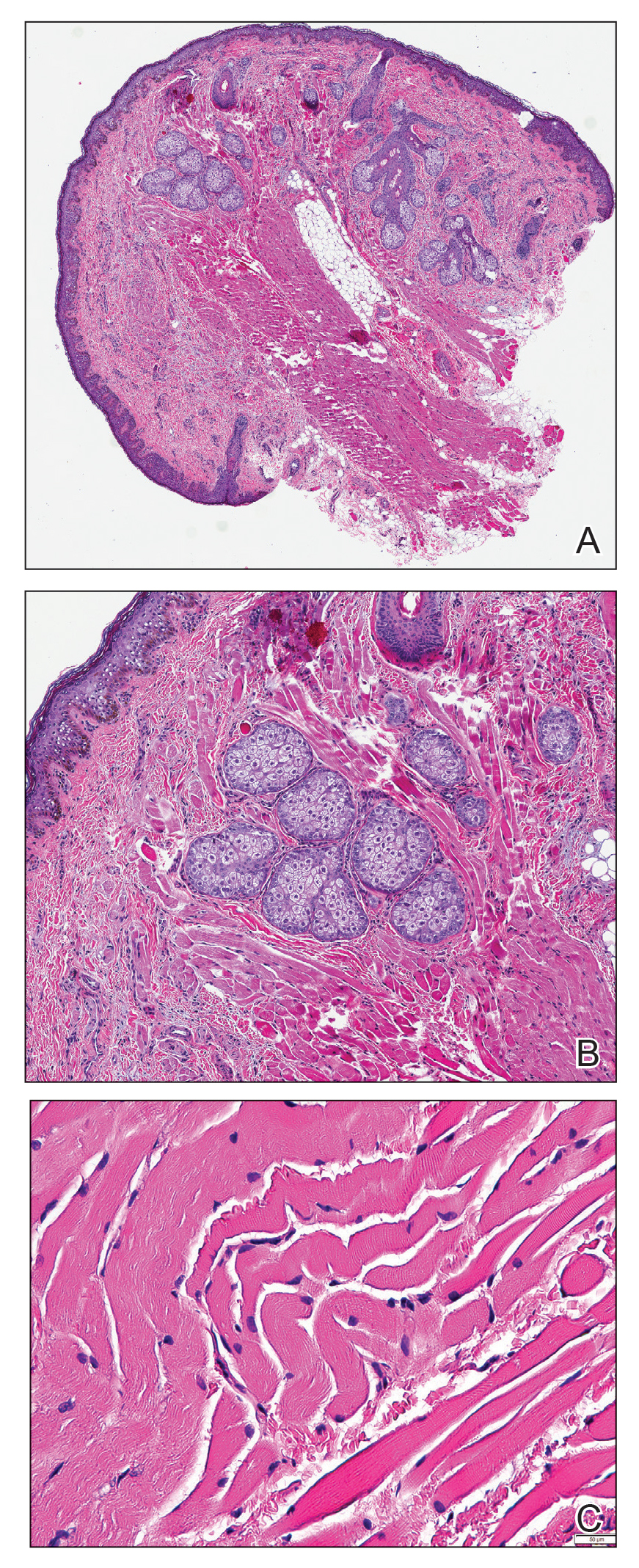

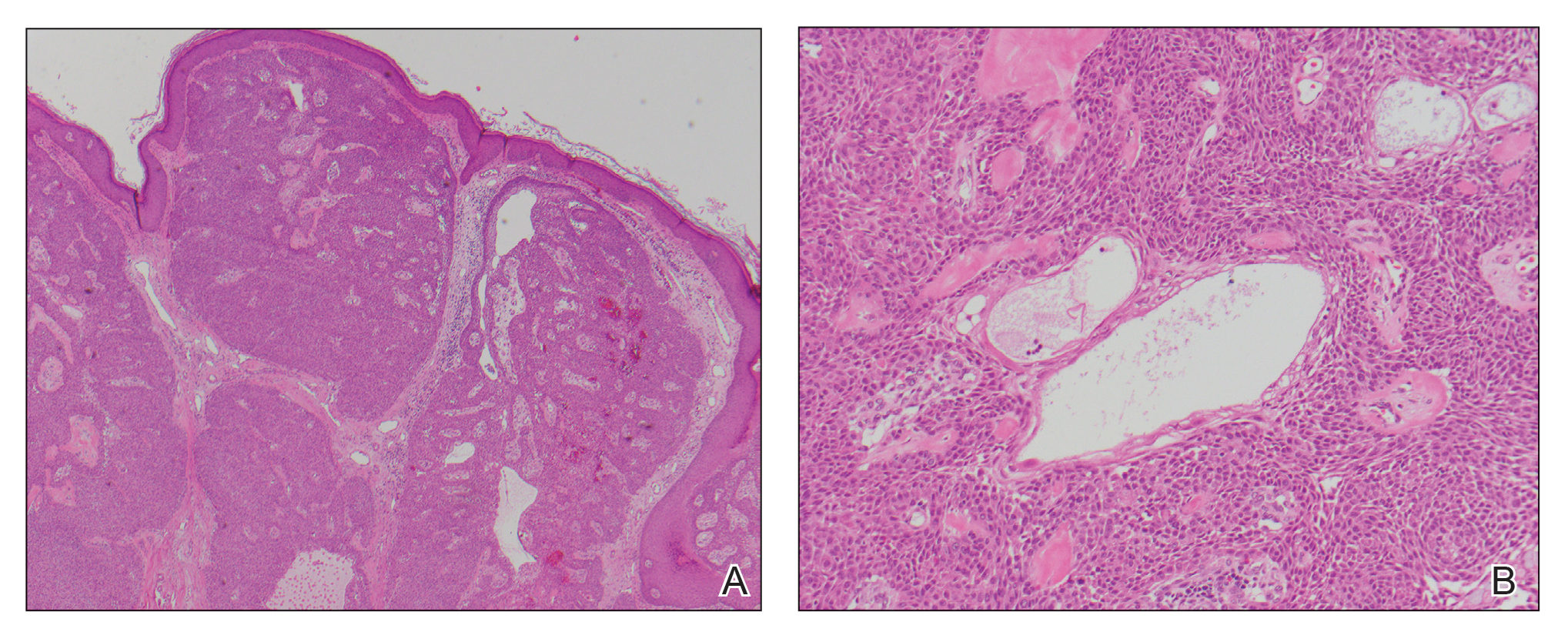

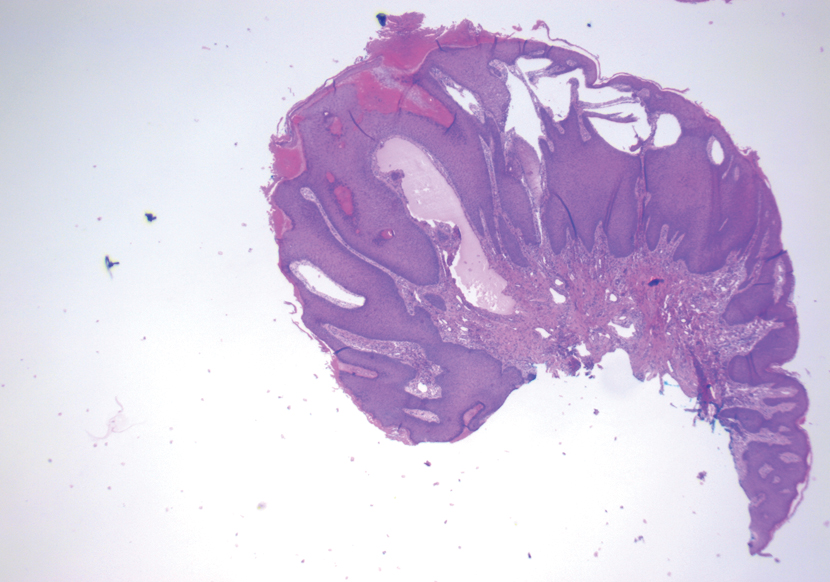

Histopathologic evaluation revealed a dome-shaped papule with a center composed of mature striated muscle bundles, vellus hairs, sebaceous lobules, and nerve twigs (Figure) consistent with a diagnosis of striated muscle hamartoma (SMH).

Striated muscle hamartoma was first described in 1986 by Hendrick et al1 with 2 cases in neonates. Biopsies of the lesions taken from the upper lip and sternum showed a characteristic histology consisting of dermal striated muscle fibers and nerve bundles in the central core of the papules associated with a marked number of adnexa. In 1989, the diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma was described, which showed similar findings.2 Cases reported since these entities were discovered have used the terms striated muscle hamartoma and rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma interchangeably.3

Most commonly found on the head and neck, SMH has now been observed in diverse locations including the sternum, hallux, vagina, and oral cavity.1-15 Many reported cases describe lesions around or in the nose.4,7,8 Multiple congenital anomalies have been described alongside SMH and may be associated with this entity including amniotic bands, cleft lip and palate, coloboma, and Delleman syndrome.1,3,4 Almost all of the lesions present as a sessile or pedunculated papule, polyp, nodule, or plaque measuring from 0.3 cm up to 4.9 cm and typically are present since birth.3,5,15 However, there are a few cases of lesions presenting in adults with no prior history.5,6,15

Microscopically, SMH is defined by a dermal lesion with a core comprised of mature skeletal muscle admixed with adipose tissue, adnexa, nerve bundles, and fibrovascular tissue.1 There are other entities that should be considered before making the diagnosis of SMH. Other hamartomas such as accessory tragus, connective tissue nevus, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, and nevus lipomatosis may present similarly; however, these lesions classically lack skeletal muscle. Benign triton tumors, or neuromuscular hamartomas, are rare lesions composed of skeletal muscle and abundant, intimately associated neural tissue. Neuromuscular hamartomas frequently involve large nerves.16 Rhabdomyomas also should be considered. Adult rhabdomyomas are composed of eosinophilic polygonal cells with granular cytoplasm and occasional cross-striations. Fetal rhabdomyomas have multiple histologic types and are defined by a variable myxoid stroma, eosinophilic spindled cells, and rhabdomyocytes in various stages of maturity. Genital rhabdomyomas histopathologically appear similar to fetal rhabdomyomas but are confined to the genital region. The skeletal muscle present in rhabdomyomas typically is less differentiated.17 TMature skeletal bundles should be a dominant component of the lesion before diagnosing SMH.

Typically presenting as congenital lesions in the head and neck region, papules with a dermal core of mature skeletal muscle associated with adnexa and nerve twigs should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of SMH or rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. These lesions are benign and usually are cured with complete excision.

- Hendrick SJ, Sanchez RL, Blackwell SJ, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma: description of two cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:153-157.

- Mills AE. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;1:58-63.

- Rosenberg AS, Kirk J, Morgan MB. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: an unusual dermal entity with a report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:238-243.

- Sánchez RL, Raimer SS. Clinical and histologic features of striated muscle hamartoma: possible relationship to Delleman’s syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:40-46.

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:185-188.

- Harris MA, Dutton JJ, Proia AD. Striated muscle hamartoma of the eyelid in an adult woman. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:492-494.

- Nakanishi H, Hashimoto I, Takiwaki H, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma of the nostril. J Dermatol. 1995;22:504-507.

- Farris PE, Manning S, Veatch F. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:73-75.

- Grilli R, Escalonilla P, Soriano ML, et al. The so-called striated muscle hamartoma is a hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyme, but not of striated muscle. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:390.

- Sampat K, Cheesman E, Siminas S. Perianal rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:E193-E195.

- Brinster NK, Farmer ER. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting on a digit. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:61-63.

- Han SH, Song HJ, Hong WK, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the vagina. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:753-755.

- De la Sotta P, Salomone C, González S. Rhabdomyomatous (mesenchymal) hamartoma of the tongue: report of a case. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:58-59.

- Magro G, Di Benedetto A, Sanges G, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of oral cavity: an unusual location for such a rare lesion. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:346-347.

- Wang Y, Zhao H, Yue X, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a big subcutaneous mass on the neck: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:410.

- Amita K, Shankar SV, Nischal KC, et al. Benign triton tumor: a rare entity in head and neck region. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:74-76.

- Walsh S, Hurt M. Cutaneous fetal rhabdomyoma: a case report and historical review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:485-491.

The Diagnosis: Striated Muscle Hamartoma

Histopathologic evaluation revealed a dome-shaped papule with a center composed of mature striated muscle bundles, vellus hairs, sebaceous lobules, and nerve twigs (Figure) consistent with a diagnosis of striated muscle hamartoma (SMH).

Striated muscle hamartoma was first described in 1986 by Hendrick et al1 with 2 cases in neonates. Biopsies of the lesions taken from the upper lip and sternum showed a characteristic histology consisting of dermal striated muscle fibers and nerve bundles in the central core of the papules associated with a marked number of adnexa. In 1989, the diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma was described, which showed similar findings.2 Cases reported since these entities were discovered have used the terms striated muscle hamartoma and rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma interchangeably.3

Most commonly found on the head and neck, SMH has now been observed in diverse locations including the sternum, hallux, vagina, and oral cavity.1-15 Many reported cases describe lesions around or in the nose.4,7,8 Multiple congenital anomalies have been described alongside SMH and may be associated with this entity including amniotic bands, cleft lip and palate, coloboma, and Delleman syndrome.1,3,4 Almost all of the lesions present as a sessile or pedunculated papule, polyp, nodule, or plaque measuring from 0.3 cm up to 4.9 cm and typically are present since birth.3,5,15 However, there are a few cases of lesions presenting in adults with no prior history.5,6,15

Microscopically, SMH is defined by a dermal lesion with a core comprised of mature skeletal muscle admixed with adipose tissue, adnexa, nerve bundles, and fibrovascular tissue.1 There are other entities that should be considered before making the diagnosis of SMH. Other hamartomas such as accessory tragus, connective tissue nevus, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, and nevus lipomatosis may present similarly; however, these lesions classically lack skeletal muscle. Benign triton tumors, or neuromuscular hamartomas, are rare lesions composed of skeletal muscle and abundant, intimately associated neural tissue. Neuromuscular hamartomas frequently involve large nerves.16 Rhabdomyomas also should be considered. Adult rhabdomyomas are composed of eosinophilic polygonal cells with granular cytoplasm and occasional cross-striations. Fetal rhabdomyomas have multiple histologic types and are defined by a variable myxoid stroma, eosinophilic spindled cells, and rhabdomyocytes in various stages of maturity. Genital rhabdomyomas histopathologically appear similar to fetal rhabdomyomas but are confined to the genital region. The skeletal muscle present in rhabdomyomas typically is less differentiated.17 TMature skeletal bundles should be a dominant component of the lesion before diagnosing SMH.

Typically presenting as congenital lesions in the head and neck region, papules with a dermal core of mature skeletal muscle associated with adnexa and nerve twigs should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of SMH or rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. These lesions are benign and usually are cured with complete excision.

The Diagnosis: Striated Muscle Hamartoma

Histopathologic evaluation revealed a dome-shaped papule with a center composed of mature striated muscle bundles, vellus hairs, sebaceous lobules, and nerve twigs (Figure) consistent with a diagnosis of striated muscle hamartoma (SMH).

Striated muscle hamartoma was first described in 1986 by Hendrick et al1 with 2 cases in neonates. Biopsies of the lesions taken from the upper lip and sternum showed a characteristic histology consisting of dermal striated muscle fibers and nerve bundles in the central core of the papules associated with a marked number of adnexa. In 1989, the diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma was described, which showed similar findings.2 Cases reported since these entities were discovered have used the terms striated muscle hamartoma and rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma interchangeably.3

Most commonly found on the head and neck, SMH has now been observed in diverse locations including the sternum, hallux, vagina, and oral cavity.1-15 Many reported cases describe lesions around or in the nose.4,7,8 Multiple congenital anomalies have been described alongside SMH and may be associated with this entity including amniotic bands, cleft lip and palate, coloboma, and Delleman syndrome.1,3,4 Almost all of the lesions present as a sessile or pedunculated papule, polyp, nodule, or plaque measuring from 0.3 cm up to 4.9 cm and typically are present since birth.3,5,15 However, there are a few cases of lesions presenting in adults with no prior history.5,6,15

Microscopically, SMH is defined by a dermal lesion with a core comprised of mature skeletal muscle admixed with adipose tissue, adnexa, nerve bundles, and fibrovascular tissue.1 There are other entities that should be considered before making the diagnosis of SMH. Other hamartomas such as accessory tragus, connective tissue nevus, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, and nevus lipomatosis may present similarly; however, these lesions classically lack skeletal muscle. Benign triton tumors, or neuromuscular hamartomas, are rare lesions composed of skeletal muscle and abundant, intimately associated neural tissue. Neuromuscular hamartomas frequently involve large nerves.16 Rhabdomyomas also should be considered. Adult rhabdomyomas are composed of eosinophilic polygonal cells with granular cytoplasm and occasional cross-striations. Fetal rhabdomyomas have multiple histologic types and are defined by a variable myxoid stroma, eosinophilic spindled cells, and rhabdomyocytes in various stages of maturity. Genital rhabdomyomas histopathologically appear similar to fetal rhabdomyomas but are confined to the genital region. The skeletal muscle present in rhabdomyomas typically is less differentiated.17 TMature skeletal bundles should be a dominant component of the lesion before diagnosing SMH.

Typically presenting as congenital lesions in the head and neck region, papules with a dermal core of mature skeletal muscle associated with adnexa and nerve twigs should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of SMH or rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. These lesions are benign and usually are cured with complete excision.

- Hendrick SJ, Sanchez RL, Blackwell SJ, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma: description of two cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:153-157.

- Mills AE. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;1:58-63.

- Rosenberg AS, Kirk J, Morgan MB. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: an unusual dermal entity with a report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:238-243.

- Sánchez RL, Raimer SS. Clinical and histologic features of striated muscle hamartoma: possible relationship to Delleman’s syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:40-46.

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:185-188.

- Harris MA, Dutton JJ, Proia AD. Striated muscle hamartoma of the eyelid in an adult woman. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:492-494.

- Nakanishi H, Hashimoto I, Takiwaki H, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma of the nostril. J Dermatol. 1995;22:504-507.

- Farris PE, Manning S, Veatch F. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:73-75.

- Grilli R, Escalonilla P, Soriano ML, et al. The so-called striated muscle hamartoma is a hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyme, but not of striated muscle. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:390.

- Sampat K, Cheesman E, Siminas S. Perianal rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:E193-E195.

- Brinster NK, Farmer ER. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting on a digit. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:61-63.

- Han SH, Song HJ, Hong WK, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the vagina. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:753-755.

- De la Sotta P, Salomone C, González S. Rhabdomyomatous (mesenchymal) hamartoma of the tongue: report of a case. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:58-59.

- Magro G, Di Benedetto A, Sanges G, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of oral cavity: an unusual location for such a rare lesion. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:346-347.

- Wang Y, Zhao H, Yue X, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a big subcutaneous mass on the neck: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:410.

- Amita K, Shankar SV, Nischal KC, et al. Benign triton tumor: a rare entity in head and neck region. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:74-76.

- Walsh S, Hurt M. Cutaneous fetal rhabdomyoma: a case report and historical review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:485-491.

- Hendrick SJ, Sanchez RL, Blackwell SJ, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma: description of two cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:153-157.

- Mills AE. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;1:58-63.

- Rosenberg AS, Kirk J, Morgan MB. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: an unusual dermal entity with a report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:238-243.

- Sánchez RL, Raimer SS. Clinical and histologic features of striated muscle hamartoma: possible relationship to Delleman’s syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:40-46.

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:185-188.

- Harris MA, Dutton JJ, Proia AD. Striated muscle hamartoma of the eyelid in an adult woman. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:492-494.

- Nakanishi H, Hashimoto I, Takiwaki H, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma of the nostril. J Dermatol. 1995;22:504-507.

- Farris PE, Manning S, Veatch F. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:73-75.

- Grilli R, Escalonilla P, Soriano ML, et al. The so-called striated muscle hamartoma is a hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyme, but not of striated muscle. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:390.

- Sampat K, Cheesman E, Siminas S. Perianal rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:E193-E195.

- Brinster NK, Farmer ER. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting on a digit. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:61-63.

- Han SH, Song HJ, Hong WK, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the vagina. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:753-755.

- De la Sotta P, Salomone C, González S. Rhabdomyomatous (mesenchymal) hamartoma of the tongue: report of a case. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:58-59.

- Magro G, Di Benedetto A, Sanges G, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of oral cavity: an unusual location for such a rare lesion. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:346-347.

- Wang Y, Zhao H, Yue X, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a big subcutaneous mass on the neck: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:410.

- Amita K, Shankar SV, Nischal KC, et al. Benign triton tumor: a rare entity in head and neck region. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:74-76.

- Walsh S, Hurt M. Cutaneous fetal rhabdomyoma: a case report and historical review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:485-491.

A 4-year-old girl presented to our clinic with an asymptomatic flesh-colored papule in the left nostril. The lesion had been present since birth and grew in relation to the patient with no rapid changes. There had been no pigmentation changes and no bleeding, pain, or itching. The patient’s birth and developmental history were normal. Physical examination revealed a singular, 10×5-mm, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on the left nasal sill. There were no additional lesions present. An excisional biopsy was performed and submitted for pathologic diagnosis.

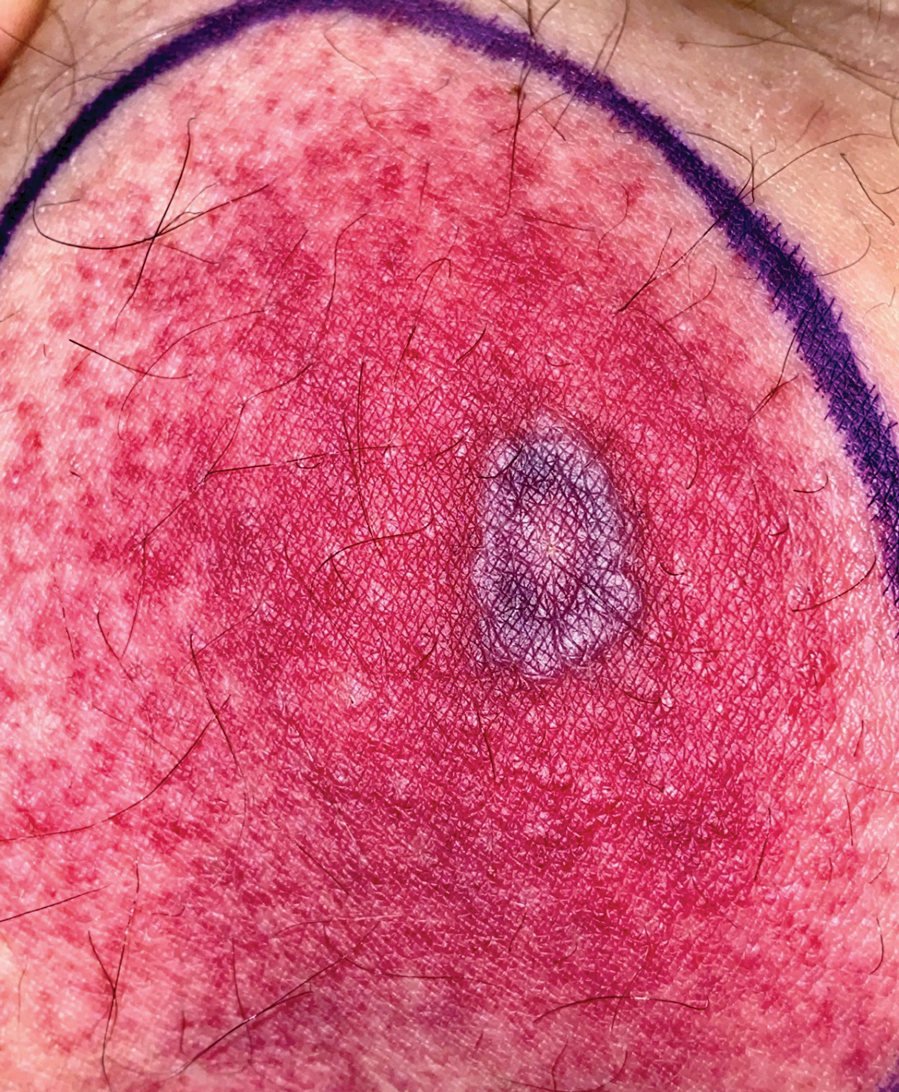

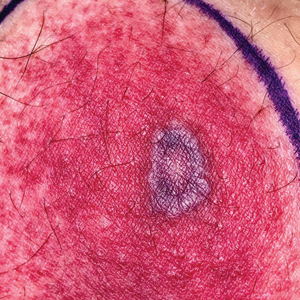

Tender Annular Plaque on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

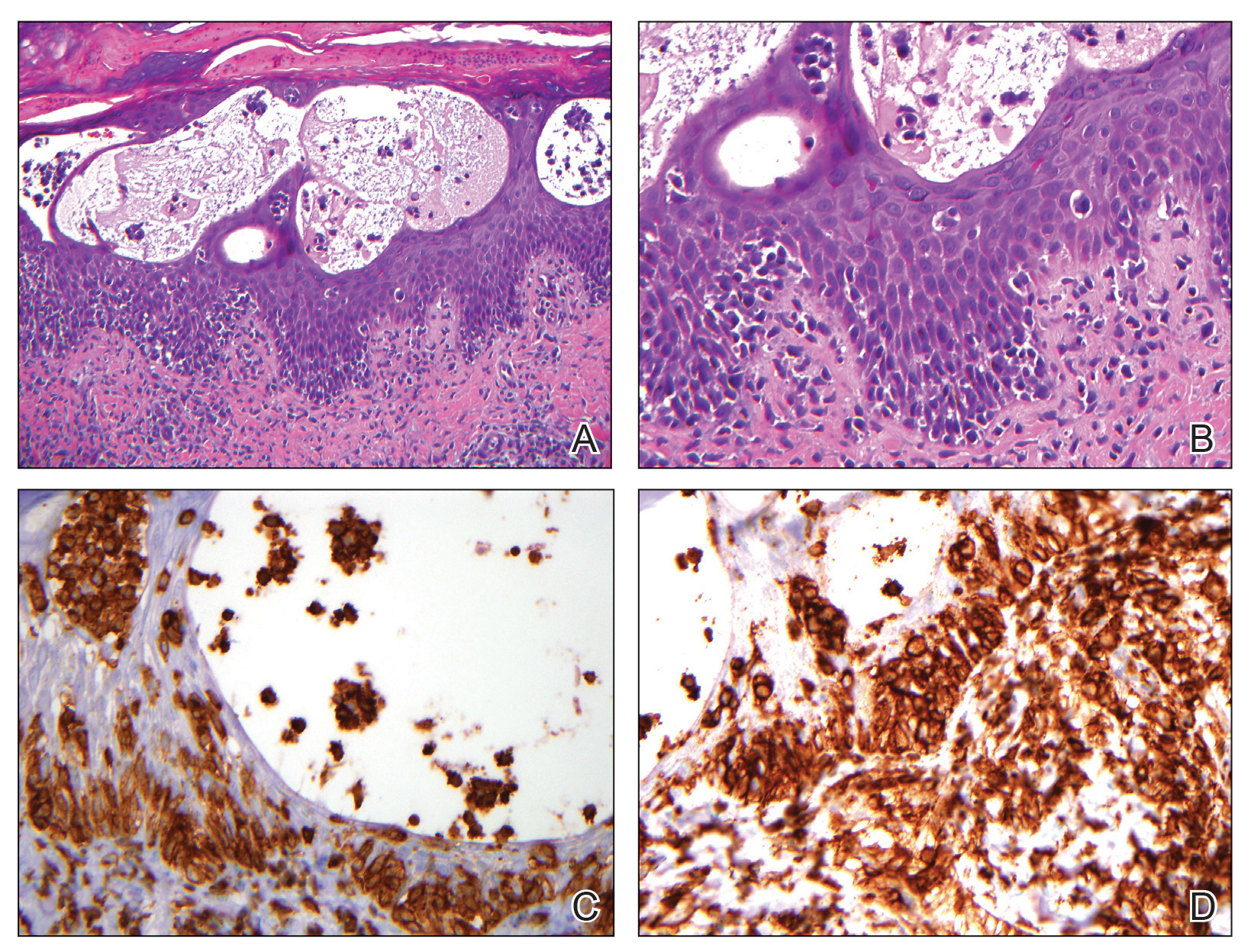

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557-565.

- Su WP, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, et al. Histopathologic and immunopathologic study of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 1986;13:323-330. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1986.tb00466.x

- Tirumalae R, Yeliur IK, Antony M, et al. Papulonecrotic tuberculidclinicopathologic and molecular features of 12 Indian patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:17-22. doi:10.5826/dpc.0402a03

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis [published online August 15, 2015]. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6m18g35f

- Vasudevan B, Chatterjee M. Lyme borreliosis and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:167-174. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110822

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.