User login

MRI isn’t of much benefit to women with breast cancer—despite a rise in its use

- “We must take the lead in the battle against breast cancer”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2009)

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for breast cancer screening and to guide treatment decisions is increasing—with little evidence that it is beneficial in those settings, according to the findings of a recent study.1 Although MRI was shown to be a valuable tool for screening women who are at genetically high risk of breast cancer, the investigation produced limited support for its 1) use in screening women in the general population and 2) routine use before breast-conserving surgery to guide patient selection, reduce surgical procedures, or lower the risk of local recurrence.

Morrow and colleagues from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reviewed research from the past decade to determine whether the increased sensitivity of MRI in the detection of cancer actually improves outcomes. Over recent years, MRI has been widely incorporated into clinical practice because of its heightened sensitivity.

There is sufficient evidence that MRI is a beneficial tool for screening women at high risk of breast cancer because of their family history or a known gene mutation. The modality can accurately identify tumors missed by mammography and ultrasonographic imaging. However, little is known about whether this improved detection has an impact on survival.

Morrow and colleagues conclude that the existing data “do not support the idea that MRI improves patient selection for breast-conserving surgery or that it increases the likelihood of obtaining negative margins at the initial surgical excision.”

Furthermore, the impact of MRI on longer-term outcomes, such as the incidence of contralateral cancer or the recurrence of ipsilateral cancer, cannot be established because of the limited number of trials, many of which are of low quality.

Research does suggest, however, that MRI is more reliable than traditional examinations (i.e., physical examination, mammography, and ultrasonography) at assessing the extent of residual disease after preoperative chemotherapy, as well as the response to preoperative chemotherapy. But whether this improves the surgeon’s ability to select patients suitable for breast-conserving therapy is unclear.

“Ultimately, the true value of MRI might lie in its ability to predict biological behavior, rather than to quantitate low-volume disease,” the investigators conclude. “Very early changes in intracellular metabolism that are detectable by magnetic resonance spectroscopy seem to be predictive of the response to treatment, and, if validated in larger studies, could avoid the toxicity and expense of continuing a chemotherapy regimen that will not be beneficial.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. Morrow M, Waters J, Morris E. MRI for breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1804-1811.

- “We must take the lead in the battle against breast cancer”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2009)

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for breast cancer screening and to guide treatment decisions is increasing—with little evidence that it is beneficial in those settings, according to the findings of a recent study.1 Although MRI was shown to be a valuable tool for screening women who are at genetically high risk of breast cancer, the investigation produced limited support for its 1) use in screening women in the general population and 2) routine use before breast-conserving surgery to guide patient selection, reduce surgical procedures, or lower the risk of local recurrence.

Morrow and colleagues from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reviewed research from the past decade to determine whether the increased sensitivity of MRI in the detection of cancer actually improves outcomes. Over recent years, MRI has been widely incorporated into clinical practice because of its heightened sensitivity.

There is sufficient evidence that MRI is a beneficial tool for screening women at high risk of breast cancer because of their family history or a known gene mutation. The modality can accurately identify tumors missed by mammography and ultrasonographic imaging. However, little is known about whether this improved detection has an impact on survival.

Morrow and colleagues conclude that the existing data “do not support the idea that MRI improves patient selection for breast-conserving surgery or that it increases the likelihood of obtaining negative margins at the initial surgical excision.”

Furthermore, the impact of MRI on longer-term outcomes, such as the incidence of contralateral cancer or the recurrence of ipsilateral cancer, cannot be established because of the limited number of trials, many of which are of low quality.

Research does suggest, however, that MRI is more reliable than traditional examinations (i.e., physical examination, mammography, and ultrasonography) at assessing the extent of residual disease after preoperative chemotherapy, as well as the response to preoperative chemotherapy. But whether this improves the surgeon’s ability to select patients suitable for breast-conserving therapy is unclear.

“Ultimately, the true value of MRI might lie in its ability to predict biological behavior, rather than to quantitate low-volume disease,” the investigators conclude. “Very early changes in intracellular metabolism that are detectable by magnetic resonance spectroscopy seem to be predictive of the response to treatment, and, if validated in larger studies, could avoid the toxicity and expense of continuing a chemotherapy regimen that will not be beneficial.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- “We must take the lead in the battle against breast cancer”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2009)

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for breast cancer screening and to guide treatment decisions is increasing—with little evidence that it is beneficial in those settings, according to the findings of a recent study.1 Although MRI was shown to be a valuable tool for screening women who are at genetically high risk of breast cancer, the investigation produced limited support for its 1) use in screening women in the general population and 2) routine use before breast-conserving surgery to guide patient selection, reduce surgical procedures, or lower the risk of local recurrence.

Morrow and colleagues from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reviewed research from the past decade to determine whether the increased sensitivity of MRI in the detection of cancer actually improves outcomes. Over recent years, MRI has been widely incorporated into clinical practice because of its heightened sensitivity.

There is sufficient evidence that MRI is a beneficial tool for screening women at high risk of breast cancer because of their family history or a known gene mutation. The modality can accurately identify tumors missed by mammography and ultrasonographic imaging. However, little is known about whether this improved detection has an impact on survival.

Morrow and colleagues conclude that the existing data “do not support the idea that MRI improves patient selection for breast-conserving surgery or that it increases the likelihood of obtaining negative margins at the initial surgical excision.”

Furthermore, the impact of MRI on longer-term outcomes, such as the incidence of contralateral cancer or the recurrence of ipsilateral cancer, cannot be established because of the limited number of trials, many of which are of low quality.

Research does suggest, however, that MRI is more reliable than traditional examinations (i.e., physical examination, mammography, and ultrasonography) at assessing the extent of residual disease after preoperative chemotherapy, as well as the response to preoperative chemotherapy. But whether this improves the surgeon’s ability to select patients suitable for breast-conserving therapy is unclear.

“Ultimately, the true value of MRI might lie in its ability to predict biological behavior, rather than to quantitate low-volume disease,” the investigators conclude. “Very early changes in intracellular metabolism that are detectable by magnetic resonance spectroscopy seem to be predictive of the response to treatment, and, if validated in larger studies, could avoid the toxicity and expense of continuing a chemotherapy regimen that will not be beneficial.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. Morrow M, Waters J, Morris E. MRI for breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1804-1811.

Reference

1. Morrow M, Waters J, Morris E. MRI for breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1804-1811.

Radiotherapy halves the rate of recurrence after breast-conserving cancer surgery

Women who undergo radiotherapy to the conserved breast after breast-conserving cancer surgery can expect a reduction in the rate of recurrence (locoregional or distant) of approximately 50% and a reduction in the rate of death from breast cancer of about one sixth. Those are the latest findings from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), published online in The Lancet.1

The EBCTCG report updates earlier analyses of individual patient data from randomized trials of radiotherapy after breast-conserving therapy. It adds follow-up data from nine of 10 trials analyzed earlier. It also includes information from seven new trials (six of them in low-risk women). Overall, it boosts the total number of women analyzed by almost 50%.1

The EBCTCG performed a meta-analysis using individual patient data from 10,801 women in 17 randomized trials of radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery. Of these women, 8,337 had pathologically confirmed lymph node status (7,287 with negative nodes and 1,050 with positive nodes).

Among the findings:

- Women randomized to radiotherapy had an average annual rate of any first recurrence 50% lower than the women who underwent surgery alone (rate ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48–0.56), with the greatest reduction seen in the first year after treatment (rate ratio, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.26–0.37). The reduction in the rate of recurrence persisted during years 5–9 (rate ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.50–0.70).

- Women allocated to radiotherapy had a reduction in the risk of death from breast cancer of about 17% (rate ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75–0.90).

- Women who had negative nodes experienced a reduction in the average annual recurrence rate of about 50% during the first decade (rate ratio, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.41–0.51), lowering the 10-year-risk of any first recurrence from 31.0% to 15.6%, an absolute reduction of 15.4% (95% CI, 13.2–17.6; 2p<.00001).

- For women who had positive nodes, randomization to radiotherapy reduced the 1-year risk of recurrence from 26.0% to 5.1%, a fivefold reduction (rate ratio, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.14–0.29)

- Overall, one breast cancer death was avoided by year 15 for every four recurrences avoided by year 10.

“The overall findings from these trials show that radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery not only substantially reduces the risk of recurrence but also moderately reduces the risk of death from breast cancer,” the investigators write. “These results suggest that killing microscopic tumor foci in the conserved breast with radiotherapy reduces the potential for both local recurrence and distant metastasis.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials [published online ahead of print October 20, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(11)61629–2.

Women who undergo radiotherapy to the conserved breast after breast-conserving cancer surgery can expect a reduction in the rate of recurrence (locoregional or distant) of approximately 50% and a reduction in the rate of death from breast cancer of about one sixth. Those are the latest findings from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), published online in The Lancet.1

The EBCTCG report updates earlier analyses of individual patient data from randomized trials of radiotherapy after breast-conserving therapy. It adds follow-up data from nine of 10 trials analyzed earlier. It also includes information from seven new trials (six of them in low-risk women). Overall, it boosts the total number of women analyzed by almost 50%.1

The EBCTCG performed a meta-analysis using individual patient data from 10,801 women in 17 randomized trials of radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery. Of these women, 8,337 had pathologically confirmed lymph node status (7,287 with negative nodes and 1,050 with positive nodes).

Among the findings:

- Women randomized to radiotherapy had an average annual rate of any first recurrence 50% lower than the women who underwent surgery alone (rate ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48–0.56), with the greatest reduction seen in the first year after treatment (rate ratio, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.26–0.37). The reduction in the rate of recurrence persisted during years 5–9 (rate ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.50–0.70).

- Women allocated to radiotherapy had a reduction in the risk of death from breast cancer of about 17% (rate ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75–0.90).

- Women who had negative nodes experienced a reduction in the average annual recurrence rate of about 50% during the first decade (rate ratio, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.41–0.51), lowering the 10-year-risk of any first recurrence from 31.0% to 15.6%, an absolute reduction of 15.4% (95% CI, 13.2–17.6; 2p<.00001).

- For women who had positive nodes, randomization to radiotherapy reduced the 1-year risk of recurrence from 26.0% to 5.1%, a fivefold reduction (rate ratio, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.14–0.29)

- Overall, one breast cancer death was avoided by year 15 for every four recurrences avoided by year 10.

“The overall findings from these trials show that radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery not only substantially reduces the risk of recurrence but also moderately reduces the risk of death from breast cancer,” the investigators write. “These results suggest that killing microscopic tumor foci in the conserved breast with radiotherapy reduces the potential for both local recurrence and distant metastasis.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Women who undergo radiotherapy to the conserved breast after breast-conserving cancer surgery can expect a reduction in the rate of recurrence (locoregional or distant) of approximately 50% and a reduction in the rate of death from breast cancer of about one sixth. Those are the latest findings from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), published online in The Lancet.1

The EBCTCG report updates earlier analyses of individual patient data from randomized trials of radiotherapy after breast-conserving therapy. It adds follow-up data from nine of 10 trials analyzed earlier. It also includes information from seven new trials (six of them in low-risk women). Overall, it boosts the total number of women analyzed by almost 50%.1

The EBCTCG performed a meta-analysis using individual patient data from 10,801 women in 17 randomized trials of radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery. Of these women, 8,337 had pathologically confirmed lymph node status (7,287 with negative nodes and 1,050 with positive nodes).

Among the findings:

- Women randomized to radiotherapy had an average annual rate of any first recurrence 50% lower than the women who underwent surgery alone (rate ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48–0.56), with the greatest reduction seen in the first year after treatment (rate ratio, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.26–0.37). The reduction in the rate of recurrence persisted during years 5–9 (rate ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.50–0.70).

- Women allocated to radiotherapy had a reduction in the risk of death from breast cancer of about 17% (rate ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75–0.90).

- Women who had negative nodes experienced a reduction in the average annual recurrence rate of about 50% during the first decade (rate ratio, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.41–0.51), lowering the 10-year-risk of any first recurrence from 31.0% to 15.6%, an absolute reduction of 15.4% (95% CI, 13.2–17.6; 2p<.00001).

- For women who had positive nodes, randomization to radiotherapy reduced the 1-year risk of recurrence from 26.0% to 5.1%, a fivefold reduction (rate ratio, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.14–0.29)

- Overall, one breast cancer death was avoided by year 15 for every four recurrences avoided by year 10.

“The overall findings from these trials show that radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery not only substantially reduces the risk of recurrence but also moderately reduces the risk of death from breast cancer,” the investigators write. “These results suggest that killing microscopic tumor foci in the conserved breast with radiotherapy reduces the potential for both local recurrence and distant metastasis.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials [published online ahead of print October 20, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(11)61629–2.

Reference

1. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials [published online ahead of print October 20, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(11)61629–2.

New data: Foley catheter is as effective as prostaglandin gel for induction of labor—with fewer side effects

The Foley catheter is one of the oldest mechanical methods used for inducing labor. New data show that it produces a vaginal delivery rate similar to that of prostaglandin E2 gel, the current treatment of choice in the United States and United Kingdom—but carries fewer side effects.1

The newly published PROBAAT trial suggests that a mechanical approach to induction of labor could reduce complications; it also challenges the belief that mechanical methods increase the risk of infection for mothers and newborns.1

In the open-label trial of 824 women in 12 hospitals in the Netherlands, women who had a singleton gestation in cephalic presentation, with intact membranes and an unfavorable cervix, were randomized to induction of labor with a 30-mL Foley catheter (n=412) or vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel (n=412). The rate of cesarean delivery was similar between groups (23% for the Foley catheter vs 20% for prostaglandin gel; risk ratio, 1.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87–1.47). Two serious maternal adverse events were recorded in the prostaglandin group—one uterine perforation after insertion of a uterine pressure catheter and one uterine rupture during augmentation with oxytocin—versus none in the Foley-catheter group, though this difference was not statistically significant.1

In addition, the women randomized to the Foley catheter had a lower rate of operative delivery for suspected fetal distress, fewer mothers required intrapartum antibiotics, and fewer newborns were admitted to the NICU. However, the time from the start of induction of labor to birth was longer with the Foley catheter (median of 29 versus 18 hours; relative risk, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.34-1.61; P < .0001).

A meta-analysis that included these new data was then conducted by the researchers; it confirmed that induction of labor with the Foley catheter produces a vaginal delivery rate similar to that of prostaglandin E2 gel and significantly reduces the rates of uterine hyperstimulation and postpartum hemorrhage. This finding is in line with another recent meta-analysis.2

In a commentary accompanying the study, Jane Norman and Sarah Stock of the University of Edinburgh in Edinburgh, Scotland, conclude: “These data should prompt a revision of the recommendation that ‘mechanical procedures (balloon catheters and laminaria tents) should not be used routinely for induction of [labor].’”3

The authors of the study itself conclude: “We think that a Foley catheter should at least be considered for induction of labor in women with an unfavorable cervix at term.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Jozwiak M, Rengerink KO, Benthem M, et al. for the PROBAAT Study Group. Foley catheter versus vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel for induction of labour at term (PROBAAT trial): an open-label, randomised controlled trial [published online ahead of print October 25, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61484-0.

2. Vaknin Z, Kurzweil Y, Sherman D, et al. Foley catheter balloon vs locally applied prostaglandins for cervical ripening and labor induction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(5):418-429.

3. Norman JE, Stock S. Intracervical Foley catheter for induction of labour [published online ahead of print October 25, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61581-X.

The Foley catheter is one of the oldest mechanical methods used for inducing labor. New data show that it produces a vaginal delivery rate similar to that of prostaglandin E2 gel, the current treatment of choice in the United States and United Kingdom—but carries fewer side effects.1

The newly published PROBAAT trial suggests that a mechanical approach to induction of labor could reduce complications; it also challenges the belief that mechanical methods increase the risk of infection for mothers and newborns.1

In the open-label trial of 824 women in 12 hospitals in the Netherlands, women who had a singleton gestation in cephalic presentation, with intact membranes and an unfavorable cervix, were randomized to induction of labor with a 30-mL Foley catheter (n=412) or vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel (n=412). The rate of cesarean delivery was similar between groups (23% for the Foley catheter vs 20% for prostaglandin gel; risk ratio, 1.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87–1.47). Two serious maternal adverse events were recorded in the prostaglandin group—one uterine perforation after insertion of a uterine pressure catheter and one uterine rupture during augmentation with oxytocin—versus none in the Foley-catheter group, though this difference was not statistically significant.1

In addition, the women randomized to the Foley catheter had a lower rate of operative delivery for suspected fetal distress, fewer mothers required intrapartum antibiotics, and fewer newborns were admitted to the NICU. However, the time from the start of induction of labor to birth was longer with the Foley catheter (median of 29 versus 18 hours; relative risk, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.34-1.61; P < .0001).

A meta-analysis that included these new data was then conducted by the researchers; it confirmed that induction of labor with the Foley catheter produces a vaginal delivery rate similar to that of prostaglandin E2 gel and significantly reduces the rates of uterine hyperstimulation and postpartum hemorrhage. This finding is in line with another recent meta-analysis.2

In a commentary accompanying the study, Jane Norman and Sarah Stock of the University of Edinburgh in Edinburgh, Scotland, conclude: “These data should prompt a revision of the recommendation that ‘mechanical procedures (balloon catheters and laminaria tents) should not be used routinely for induction of [labor].’”3

The authors of the study itself conclude: “We think that a Foley catheter should at least be considered for induction of labor in women with an unfavorable cervix at term.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The Foley catheter is one of the oldest mechanical methods used for inducing labor. New data show that it produces a vaginal delivery rate similar to that of prostaglandin E2 gel, the current treatment of choice in the United States and United Kingdom—but carries fewer side effects.1

The newly published PROBAAT trial suggests that a mechanical approach to induction of labor could reduce complications; it also challenges the belief that mechanical methods increase the risk of infection for mothers and newborns.1

In the open-label trial of 824 women in 12 hospitals in the Netherlands, women who had a singleton gestation in cephalic presentation, with intact membranes and an unfavorable cervix, were randomized to induction of labor with a 30-mL Foley catheter (n=412) or vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel (n=412). The rate of cesarean delivery was similar between groups (23% for the Foley catheter vs 20% for prostaglandin gel; risk ratio, 1.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87–1.47). Two serious maternal adverse events were recorded in the prostaglandin group—one uterine perforation after insertion of a uterine pressure catheter and one uterine rupture during augmentation with oxytocin—versus none in the Foley-catheter group, though this difference was not statistically significant.1

In addition, the women randomized to the Foley catheter had a lower rate of operative delivery for suspected fetal distress, fewer mothers required intrapartum antibiotics, and fewer newborns were admitted to the NICU. However, the time from the start of induction of labor to birth was longer with the Foley catheter (median of 29 versus 18 hours; relative risk, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.34-1.61; P < .0001).

A meta-analysis that included these new data was then conducted by the researchers; it confirmed that induction of labor with the Foley catheter produces a vaginal delivery rate similar to that of prostaglandin E2 gel and significantly reduces the rates of uterine hyperstimulation and postpartum hemorrhage. This finding is in line with another recent meta-analysis.2

In a commentary accompanying the study, Jane Norman and Sarah Stock of the University of Edinburgh in Edinburgh, Scotland, conclude: “These data should prompt a revision of the recommendation that ‘mechanical procedures (balloon catheters and laminaria tents) should not be used routinely for induction of [labor].’”3

The authors of the study itself conclude: “We think that a Foley catheter should at least be considered for induction of labor in women with an unfavorable cervix at term.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Jozwiak M, Rengerink KO, Benthem M, et al. for the PROBAAT Study Group. Foley catheter versus vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel for induction of labour at term (PROBAAT trial): an open-label, randomised controlled trial [published online ahead of print October 25, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61484-0.

2. Vaknin Z, Kurzweil Y, Sherman D, et al. Foley catheter balloon vs locally applied prostaglandins for cervical ripening and labor induction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(5):418-429.

3. Norman JE, Stock S. Intracervical Foley catheter for induction of labour [published online ahead of print October 25, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61581-X.

1. Jozwiak M, Rengerink KO, Benthem M, et al. for the PROBAAT Study Group. Foley catheter versus vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel for induction of labour at term (PROBAAT trial): an open-label, randomised controlled trial [published online ahead of print October 25, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61484-0.

2. Vaknin Z, Kurzweil Y, Sherman D, et al. Foley catheter balloon vs locally applied prostaglandins for cervical ripening and labor induction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(5):418-429.

3. Norman JE, Stock S. Intracervical Foley catheter for induction of labour [published online ahead of print October 25, 2011]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61581-X.

Noninvasive test identifies more than 98% of Down syndrome cases

The first noninvasive maternal blood test for Down syndrome is available to physicians on request in 20 major metropolitan regions in the United States, with more widespread availability planned in the coming months.

According to manufacturer Sequenom, Inc., the MaterniT21 assay is indicated for use in pregnant women at “high risk” of carrying a fetus with Down syndrome and can accurately test maternal blood as early as 10 weeks of gestation.

The test is based on the presence of cell-free fetal nucleic acids in maternal plasma. The health provider draws a small sample of whole blood from a pregnant woman and ships the sample to the Sequenom Center for Molecular Medicine in San Diego, California, where massively parallel sequencing (MPS) is used to measure a possible overabundance of chromosome 21, or Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).

Down syndrome affects approximately 6,000 infants or 1 in every 691 pregnancies each year in the United States.1

Currently, identification of Trisomy 21 requires assessment of several maternal serum screening markers and sonographic measurement of nuchal translucency. If these tests identify a high risk of Trisomy 21, chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis follows. First-trimester screening identifies as many as 90% of all cases of Down syndrome, with a false-positive rate of 2%.1 Because CVS and amniocentesis are invasive, however, they carry a small risk of pregnancy loss.

All MaterniT21 tests must be interpreted at one of the manufacturer’s laboratories. Approximate cost: $1,900—roughly equivalent to the cost of amniocentesis. Sequenom expects the out-of-pocket cost for patients with insurance to be no more than $235.

The test is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, which does not regulate tests when only one laboratory is involved.

Similar tests for Down syndrome are reportedly being developed by other laboratories.

Data on the new test

MaterniT21 was evaluated in a validation study of 4,664 women who had a high risk of Down syndrome.2 Fetal karyotyping was compared with the MaterniT21 test in 212 cases of Down syndrome and 1,484 matched euploid cases. The Down syndrome detection rate for the MaterniT21 test was 98.6% (209 of 212 cases); the false-positive rate was 0.20% (three of 1,471 cases); and testing failed in 13 pregnancies (0.8%), all of which were euploid. Researchers concluded that the new test “can substantially reduce the need for invasive diagnostic procedures and attendant procedure-related fetal losses.”2

“The results of this large clinical validation study are extremely promising,” said Allan T. Bombard, MD, laboratory director of Sequenom Center for Molecular Medicine and one of the authors of the study. “We believe perinatal specialists and obstetricians will appreciate the introduction of a test that is noninvasive and highly specific.”

The manufacturer is planning outreach to clinicians through its sales force, medical science liaisons, managed care team, and genetic counselors.

Is the test ready for widespread use?

“I certainly think this test needs to be confirmed by other studies before it becomes ready for prime time,” says Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and clinical geneticist at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. Dr. Kuller notes that the MaterniT21 test detects only Trisomy 21, whereas conventional first-trimester screening assesses Trisomy 18 and, usually, Trisomy 13 as well. Dr. Kuller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke.

“Another big question mark is what does one do with an abnormal result? We have a pretty standardized algorithm for what we do if a patient has an abnormal first-trimester screen,” he points out—”they’re offered invasive testing.” But it’s unclear whether this test is intended to be diagnostic if it detects Trisomy 21.

“Can we essentially tell a patient, ‘You’re carrying a fetus with Down syndrome?’ Or do we need to do invasive testing like we do right now?”

Another unresolved issue is whether the test can be used reliably in a “low-risk” population. The creators of the MaterniT21 assay tested the product only in a “high-risk” population, Dr. Kuller notes. “I don’t think we know whether this would be a reasonable test for all patients.”

These three issues remain unresolved, says Dr. Kuller:

- confirmation of the test’s efficacy in additional studies

- clarification of whether it is diagnostic of Down syndrome

- evaluation of the test in a population at low risk of Trisomy 21.

Panel offers recommendations for genetic counseling

The International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD) issued a “rapid response statement” on the new test on October 24: “At this time, individual women who might be considering the MPS test need to receive detailed genetic counseling that explains the benefits and limitations of the test. Testing should only be provided after an informed consent.”3

The ISPD recommends that the following information be conveyed to the patient:

- The test identifies only Down syndrome, or only “about half of the fetal aneuploidy that would be identified through amniocentesis or CVS”.

- The test is not perfect; that is, it does not identify all cases of fetal Down syndrome.

- Because false-positive results are possible, women who test positive still need the result confirmed by amniocentesis or CVS.

- If a woman tests positive for Down syndrome on the MPS test, the waiting period for the results of confirmatory testing may be “highly stressful”.

- The MPS test may not be informative in all cases.

- Women who have an elevated risk of having a child with a “prenatally diagnosable disorder with Mendelian pattern of inheritance, microdeletion syndrome, or some other conditions” still need to undergo amniocentesis or CVS.3

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Facts about Down Syndrome.http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/DownSyndrome.html. Updated June 8 2011. Accessed October 24, 2011.

2. Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: an international clinical validation study [published online ahead of print October 14, 2011. Genet Med. 2011. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182368a0e.

3. International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis. ISPD Rapid Response Statement: Prenatal Detection of Down Syndrome using Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS): a rapid response statement from a committee on behalf of the Board of the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis 24 October 2011. Charlottesville, Va: ISPD; 2011.

The first noninvasive maternal blood test for Down syndrome is available to physicians on request in 20 major metropolitan regions in the United States, with more widespread availability planned in the coming months.

According to manufacturer Sequenom, Inc., the MaterniT21 assay is indicated for use in pregnant women at “high risk” of carrying a fetus with Down syndrome and can accurately test maternal blood as early as 10 weeks of gestation.

The test is based on the presence of cell-free fetal nucleic acids in maternal plasma. The health provider draws a small sample of whole blood from a pregnant woman and ships the sample to the Sequenom Center for Molecular Medicine in San Diego, California, where massively parallel sequencing (MPS) is used to measure a possible overabundance of chromosome 21, or Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).

Down syndrome affects approximately 6,000 infants or 1 in every 691 pregnancies each year in the United States.1

Currently, identification of Trisomy 21 requires assessment of several maternal serum screening markers and sonographic measurement of nuchal translucency. If these tests identify a high risk of Trisomy 21, chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis follows. First-trimester screening identifies as many as 90% of all cases of Down syndrome, with a false-positive rate of 2%.1 Because CVS and amniocentesis are invasive, however, they carry a small risk of pregnancy loss.

All MaterniT21 tests must be interpreted at one of the manufacturer’s laboratories. Approximate cost: $1,900—roughly equivalent to the cost of amniocentesis. Sequenom expects the out-of-pocket cost for patients with insurance to be no more than $235.

The test is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, which does not regulate tests when only one laboratory is involved.

Similar tests for Down syndrome are reportedly being developed by other laboratories.

Data on the new test

MaterniT21 was evaluated in a validation study of 4,664 women who had a high risk of Down syndrome.2 Fetal karyotyping was compared with the MaterniT21 test in 212 cases of Down syndrome and 1,484 matched euploid cases. The Down syndrome detection rate for the MaterniT21 test was 98.6% (209 of 212 cases); the false-positive rate was 0.20% (three of 1,471 cases); and testing failed in 13 pregnancies (0.8%), all of which were euploid. Researchers concluded that the new test “can substantially reduce the need for invasive diagnostic procedures and attendant procedure-related fetal losses.”2

“The results of this large clinical validation study are extremely promising,” said Allan T. Bombard, MD, laboratory director of Sequenom Center for Molecular Medicine and one of the authors of the study. “We believe perinatal specialists and obstetricians will appreciate the introduction of a test that is noninvasive and highly specific.”

The manufacturer is planning outreach to clinicians through its sales force, medical science liaisons, managed care team, and genetic counselors.

Is the test ready for widespread use?

“I certainly think this test needs to be confirmed by other studies before it becomes ready for prime time,” says Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and clinical geneticist at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. Dr. Kuller notes that the MaterniT21 test detects only Trisomy 21, whereas conventional first-trimester screening assesses Trisomy 18 and, usually, Trisomy 13 as well. Dr. Kuller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke.

“Another big question mark is what does one do with an abnormal result? We have a pretty standardized algorithm for what we do if a patient has an abnormal first-trimester screen,” he points out—”they’re offered invasive testing.” But it’s unclear whether this test is intended to be diagnostic if it detects Trisomy 21.

“Can we essentially tell a patient, ‘You’re carrying a fetus with Down syndrome?’ Or do we need to do invasive testing like we do right now?”

Another unresolved issue is whether the test can be used reliably in a “low-risk” population. The creators of the MaterniT21 assay tested the product only in a “high-risk” population, Dr. Kuller notes. “I don’t think we know whether this would be a reasonable test for all patients.”

These three issues remain unresolved, says Dr. Kuller:

- confirmation of the test’s efficacy in additional studies

- clarification of whether it is diagnostic of Down syndrome

- evaluation of the test in a population at low risk of Trisomy 21.

Panel offers recommendations for genetic counseling

The International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD) issued a “rapid response statement” on the new test on October 24: “At this time, individual women who might be considering the MPS test need to receive detailed genetic counseling that explains the benefits and limitations of the test. Testing should only be provided after an informed consent.”3

The ISPD recommends that the following information be conveyed to the patient:

- The test identifies only Down syndrome, or only “about half of the fetal aneuploidy that would be identified through amniocentesis or CVS”.

- The test is not perfect; that is, it does not identify all cases of fetal Down syndrome.

- Because false-positive results are possible, women who test positive still need the result confirmed by amniocentesis or CVS.

- If a woman tests positive for Down syndrome on the MPS test, the waiting period for the results of confirmatory testing may be “highly stressful”.

- The MPS test may not be informative in all cases.

- Women who have an elevated risk of having a child with a “prenatally diagnosable disorder with Mendelian pattern of inheritance, microdeletion syndrome, or some other conditions” still need to undergo amniocentesis or CVS.3

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The first noninvasive maternal blood test for Down syndrome is available to physicians on request in 20 major metropolitan regions in the United States, with more widespread availability planned in the coming months.

According to manufacturer Sequenom, Inc., the MaterniT21 assay is indicated for use in pregnant women at “high risk” of carrying a fetus with Down syndrome and can accurately test maternal blood as early as 10 weeks of gestation.

The test is based on the presence of cell-free fetal nucleic acids in maternal plasma. The health provider draws a small sample of whole blood from a pregnant woman and ships the sample to the Sequenom Center for Molecular Medicine in San Diego, California, where massively parallel sequencing (MPS) is used to measure a possible overabundance of chromosome 21, or Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).

Down syndrome affects approximately 6,000 infants or 1 in every 691 pregnancies each year in the United States.1

Currently, identification of Trisomy 21 requires assessment of several maternal serum screening markers and sonographic measurement of nuchal translucency. If these tests identify a high risk of Trisomy 21, chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis follows. First-trimester screening identifies as many as 90% of all cases of Down syndrome, with a false-positive rate of 2%.1 Because CVS and amniocentesis are invasive, however, they carry a small risk of pregnancy loss.

All MaterniT21 tests must be interpreted at one of the manufacturer’s laboratories. Approximate cost: $1,900—roughly equivalent to the cost of amniocentesis. Sequenom expects the out-of-pocket cost for patients with insurance to be no more than $235.

The test is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, which does not regulate tests when only one laboratory is involved.

Similar tests for Down syndrome are reportedly being developed by other laboratories.

Data on the new test

MaterniT21 was evaluated in a validation study of 4,664 women who had a high risk of Down syndrome.2 Fetal karyotyping was compared with the MaterniT21 test in 212 cases of Down syndrome and 1,484 matched euploid cases. The Down syndrome detection rate for the MaterniT21 test was 98.6% (209 of 212 cases); the false-positive rate was 0.20% (three of 1,471 cases); and testing failed in 13 pregnancies (0.8%), all of which were euploid. Researchers concluded that the new test “can substantially reduce the need for invasive diagnostic procedures and attendant procedure-related fetal losses.”2

“The results of this large clinical validation study are extremely promising,” said Allan T. Bombard, MD, laboratory director of Sequenom Center for Molecular Medicine and one of the authors of the study. “We believe perinatal specialists and obstetricians will appreciate the introduction of a test that is noninvasive and highly specific.”

The manufacturer is planning outreach to clinicians through its sales force, medical science liaisons, managed care team, and genetic counselors.

Is the test ready for widespread use?

“I certainly think this test needs to be confirmed by other studies before it becomes ready for prime time,” says Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and clinical geneticist at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. Dr. Kuller notes that the MaterniT21 test detects only Trisomy 21, whereas conventional first-trimester screening assesses Trisomy 18 and, usually, Trisomy 13 as well. Dr. Kuller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke.

“Another big question mark is what does one do with an abnormal result? We have a pretty standardized algorithm for what we do if a patient has an abnormal first-trimester screen,” he points out—”they’re offered invasive testing.” But it’s unclear whether this test is intended to be diagnostic if it detects Trisomy 21.

“Can we essentially tell a patient, ‘You’re carrying a fetus with Down syndrome?’ Or do we need to do invasive testing like we do right now?”

Another unresolved issue is whether the test can be used reliably in a “low-risk” population. The creators of the MaterniT21 assay tested the product only in a “high-risk” population, Dr. Kuller notes. “I don’t think we know whether this would be a reasonable test for all patients.”

These three issues remain unresolved, says Dr. Kuller:

- confirmation of the test’s efficacy in additional studies

- clarification of whether it is diagnostic of Down syndrome

- evaluation of the test in a population at low risk of Trisomy 21.

Panel offers recommendations for genetic counseling

The International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD) issued a “rapid response statement” on the new test on October 24: “At this time, individual women who might be considering the MPS test need to receive detailed genetic counseling that explains the benefits and limitations of the test. Testing should only be provided after an informed consent.”3

The ISPD recommends that the following information be conveyed to the patient:

- The test identifies only Down syndrome, or only “about half of the fetal aneuploidy that would be identified through amniocentesis or CVS”.

- The test is not perfect; that is, it does not identify all cases of fetal Down syndrome.

- Because false-positive results are possible, women who test positive still need the result confirmed by amniocentesis or CVS.

- If a woman tests positive for Down syndrome on the MPS test, the waiting period for the results of confirmatory testing may be “highly stressful”.

- The MPS test may not be informative in all cases.

- Women who have an elevated risk of having a child with a “prenatally diagnosable disorder with Mendelian pattern of inheritance, microdeletion syndrome, or some other conditions” still need to undergo amniocentesis or CVS.3

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Facts about Down Syndrome.http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/DownSyndrome.html. Updated June 8 2011. Accessed October 24, 2011.

2. Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: an international clinical validation study [published online ahead of print October 14, 2011. Genet Med. 2011. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182368a0e.

3. International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis. ISPD Rapid Response Statement: Prenatal Detection of Down Syndrome using Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS): a rapid response statement from a committee on behalf of the Board of the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis 24 October 2011. Charlottesville, Va: ISPD; 2011.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Facts about Down Syndrome.http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/DownSyndrome.html. Updated June 8 2011. Accessed October 24, 2011.

2. Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: an international clinical validation study [published online ahead of print October 14, 2011. Genet Med. 2011. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182368a0e.

3. International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis. ISPD Rapid Response Statement: Prenatal Detection of Down Syndrome using Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS): a rapid response statement from a committee on behalf of the Board of the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis 24 October 2011. Charlottesville, Va: ISPD; 2011.

VTE risk in hormone therapy: Lower with transdermal estradiol than with oral estrogen, study finds

Experience from research and practice have demonstrated that venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common complication of hormone therapy. Now, that obstacle to safe treatment of the symptoms of menopause may be tempered by the results of a large population-based study, suggesting that patients who take transdermal estradiol have a 30% lower incidence of VTE than those who take oral estrogen only. The lower risk of VTE was also statistically significant when transdermal estradiol was at high dose.1,2

Study results were presented at the 22nd Annual Meeting of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) in Washington, DC, in September.

In the retrospective, matched-cohort study that compared high-dose transdermal estradiol and oral estrogen-only HT agents, 115 of 27,018 users of the estradiol transdermal system (ETS) and 164 of 27,018 users of the oral estrogen developed VTE. In those taking high-dose ETS (0.1 mg/day), 32 of 8,956 ETS users and 65 of 8,956 oral users of high dose oral estrogen developed VTE.1,2

“The incidence of hospitalization related to VTE events among the ETS users was also significantly lower, relative to the oral-only hormone therapy users,” said Eric Beresford, PharmD, presenter and coauthor of the study and director of medical affairs at Forest Research Institute, Secaucus, NJ, who previously worked at Novartis.1

2011-2012 NAMS President JoAnn Manson, MD, DrPH, HCMP, commented that the study “provides further reassurance that transdermal estrogen may not increase the risk of venous thrombosis.”1

“We do know that transdermal products don’t go directly to the liver and don’t increase the production of clotting proteins to the same extent as the oral estrogen products,” Manson added, “so it’s biologically very plausible. I do think that it’s a reasonable choice for trying to avoid venous thrombosis risk.”1

For details: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/750558.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Yin S. Transdermal Estradiol Safer Than Oral Estrogen. MedScape.com. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/750558. Published September 28, 2011. Accessed September 29, 2011.

2. Kahler KH, Nyirady J, Beresford E, et al. Does route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy and estradiol transdermal system dosage strength impact risk of venous thromboembolism. Washington, DC: North American Menopause Society (NAMS); September 23, 2011. Abstract S-4. http://www.menopause.org/meetings/AGMasithappens.aspx. Accessed September 29, 2011.

Experience from research and practice have demonstrated that venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common complication of hormone therapy. Now, that obstacle to safe treatment of the symptoms of menopause may be tempered by the results of a large population-based study, suggesting that patients who take transdermal estradiol have a 30% lower incidence of VTE than those who take oral estrogen only. The lower risk of VTE was also statistically significant when transdermal estradiol was at high dose.1,2

Study results were presented at the 22nd Annual Meeting of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) in Washington, DC, in September.

In the retrospective, matched-cohort study that compared high-dose transdermal estradiol and oral estrogen-only HT agents, 115 of 27,018 users of the estradiol transdermal system (ETS) and 164 of 27,018 users of the oral estrogen developed VTE. In those taking high-dose ETS (0.1 mg/day), 32 of 8,956 ETS users and 65 of 8,956 oral users of high dose oral estrogen developed VTE.1,2

“The incidence of hospitalization related to VTE events among the ETS users was also significantly lower, relative to the oral-only hormone therapy users,” said Eric Beresford, PharmD, presenter and coauthor of the study and director of medical affairs at Forest Research Institute, Secaucus, NJ, who previously worked at Novartis.1

2011-2012 NAMS President JoAnn Manson, MD, DrPH, HCMP, commented that the study “provides further reassurance that transdermal estrogen may not increase the risk of venous thrombosis.”1

“We do know that transdermal products don’t go directly to the liver and don’t increase the production of clotting proteins to the same extent as the oral estrogen products,” Manson added, “so it’s biologically very plausible. I do think that it’s a reasonable choice for trying to avoid venous thrombosis risk.”1

For details: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/750558.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Experience from research and practice have demonstrated that venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common complication of hormone therapy. Now, that obstacle to safe treatment of the symptoms of menopause may be tempered by the results of a large population-based study, suggesting that patients who take transdermal estradiol have a 30% lower incidence of VTE than those who take oral estrogen only. The lower risk of VTE was also statistically significant when transdermal estradiol was at high dose.1,2

Study results were presented at the 22nd Annual Meeting of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) in Washington, DC, in September.

In the retrospective, matched-cohort study that compared high-dose transdermal estradiol and oral estrogen-only HT agents, 115 of 27,018 users of the estradiol transdermal system (ETS) and 164 of 27,018 users of the oral estrogen developed VTE. In those taking high-dose ETS (0.1 mg/day), 32 of 8,956 ETS users and 65 of 8,956 oral users of high dose oral estrogen developed VTE.1,2

“The incidence of hospitalization related to VTE events among the ETS users was also significantly lower, relative to the oral-only hormone therapy users,” said Eric Beresford, PharmD, presenter and coauthor of the study and director of medical affairs at Forest Research Institute, Secaucus, NJ, who previously worked at Novartis.1

2011-2012 NAMS President JoAnn Manson, MD, DrPH, HCMP, commented that the study “provides further reassurance that transdermal estrogen may not increase the risk of venous thrombosis.”1

“We do know that transdermal products don’t go directly to the liver and don’t increase the production of clotting proteins to the same extent as the oral estrogen products,” Manson added, “so it’s biologically very plausible. I do think that it’s a reasonable choice for trying to avoid venous thrombosis risk.”1

For details: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/750558.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Yin S. Transdermal Estradiol Safer Than Oral Estrogen. MedScape.com. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/750558. Published September 28, 2011. Accessed September 29, 2011.

2. Kahler KH, Nyirady J, Beresford E, et al. Does route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy and estradiol transdermal system dosage strength impact risk of venous thromboembolism. Washington, DC: North American Menopause Society (NAMS); September 23, 2011. Abstract S-4. http://www.menopause.org/meetings/AGMasithappens.aspx. Accessed September 29, 2011.

1. Yin S. Transdermal Estradiol Safer Than Oral Estrogen. MedScape.com. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/750558. Published September 28, 2011. Accessed September 29, 2011.

2. Kahler KH, Nyirady J, Beresford E, et al. Does route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy and estradiol transdermal system dosage strength impact risk of venous thromboembolism. Washington, DC: North American Menopause Society (NAMS); September 23, 2011. Abstract S-4. http://www.menopause.org/meetings/AGMasithappens.aspx. Accessed September 29, 2011.

Daughters whose mothers are known carriers of genetic breast cancer are anxious and uninformed

Daughters of known carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations are understandably stressed, reported A. Farkas Patenaude, PhD, in a paper, “What do young adult daughters of BRCA mutation carriers know about hereditary risk and how much do they worry,” presented at The Era of Hope Conference in Orlando, Florida, August 2–6.

These 18-to-24-year-olds are at a 50% to 85% risk for breast and related ovarian cancers2—significantly more so than that of the general population (at 30 years, a 0.43% risk).1 In addition, these types of breast and ovarian cancer often occur at an unusually young age.2

Although ACOG recommends that annual screening mammograms begin at age 40,3 daughters of women who are known gene-mutation carriers should begin screening mammography at age 25.4 The ability of these women to make informed health decisions depends on their becoming knowledgeable about the risks, the availability of genetic testing, and options for screening and risk-reducing prophylactic surgery.

Although the daughters expressed worry about hereditary breast cancer, they had limited understanding of screening and risk-reduction options. If they did have the information, Dr. Patenaude’s study found, the young women were often afraid to have the testing.2,4

“Young, high-risk women have little knowledge about the probabilities and options for managing the cancers for which their risks are remarkably increased. Further, many report intense anxiety related to their potential cancer development,” said Dr. Patenaude of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. “These data support the need and can provide the foundation for the development of targeted educational materials to reduce that anxiety and ultimately improve participation in effective screening and risk-reducing interventions that can improve survival and quality of life for these young women.”2

The Era of Hope Conference provides a forum for scientists and clinicians from a variety of disciplines to join breast cancer survivors and advocates to discuss the advances made by the Congressionally Directed Breast Cancer Research Programs BCRP awardees, and to identify innovative, high-impact approaches for future research. Recognized as one of the premiere breast cancer research meetings.5

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Breast cancer risk by age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/age.htm. Updated August 13, 2010. Accessed August 10, 2011.

2. What Do Young Adult Daughters of BRCA Mutation Carriers Know About Hereditary Risk and How Much Do They Worry [press release]. http://eraofhopemediapage.org/press-releases-2/. Accessed August 9, 2011.

3. Yates J. ACOG recommends that annual screening mammograms begin at age 40. OBG Manage. 2011;23(8). http://www.obgmanagement.com/article_pages.asp?filename="2310OBG_NEWS_Daughters" aid=9816. Accessed August 9, 2011.

4. What Do Young Adult Daughters of BRCA Mutation Carriers Know About Hereditary Risk and How Much Do They Worry [Webinar]. Era of Hope Press Briefing. http://eraofhopemediapage.org/Era%20of%20Hope%20Press%20Conference%20Undedited/lib/playback.html. Published August 3, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2011.

5. Era of Hope 2011. CDMRPCures.org Web site. https://cdmrpcures.org/ocs/index.php/eoh/eoh2011. Accessed August 9, 2011.

Daughters of known carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations are understandably stressed, reported A. Farkas Patenaude, PhD, in a paper, “What do young adult daughters of BRCA mutation carriers know about hereditary risk and how much do they worry,” presented at The Era of Hope Conference in Orlando, Florida, August 2–6.

These 18-to-24-year-olds are at a 50% to 85% risk for breast and related ovarian cancers2—significantly more so than that of the general population (at 30 years, a 0.43% risk).1 In addition, these types of breast and ovarian cancer often occur at an unusually young age.2

Although ACOG recommends that annual screening mammograms begin at age 40,3 daughters of women who are known gene-mutation carriers should begin screening mammography at age 25.4 The ability of these women to make informed health decisions depends on their becoming knowledgeable about the risks, the availability of genetic testing, and options for screening and risk-reducing prophylactic surgery.

Although the daughters expressed worry about hereditary breast cancer, they had limited understanding of screening and risk-reduction options. If they did have the information, Dr. Patenaude’s study found, the young women were often afraid to have the testing.2,4

“Young, high-risk women have little knowledge about the probabilities and options for managing the cancers for which their risks are remarkably increased. Further, many report intense anxiety related to their potential cancer development,” said Dr. Patenaude of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. “These data support the need and can provide the foundation for the development of targeted educational materials to reduce that anxiety and ultimately improve participation in effective screening and risk-reducing interventions that can improve survival and quality of life for these young women.”2

The Era of Hope Conference provides a forum for scientists and clinicians from a variety of disciplines to join breast cancer survivors and advocates to discuss the advances made by the Congressionally Directed Breast Cancer Research Programs BCRP awardees, and to identify innovative, high-impact approaches for future research. Recognized as one of the premiere breast cancer research meetings.5

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Daughters of known carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations are understandably stressed, reported A. Farkas Patenaude, PhD, in a paper, “What do young adult daughters of BRCA mutation carriers know about hereditary risk and how much do they worry,” presented at The Era of Hope Conference in Orlando, Florida, August 2–6.

These 18-to-24-year-olds are at a 50% to 85% risk for breast and related ovarian cancers2—significantly more so than that of the general population (at 30 years, a 0.43% risk).1 In addition, these types of breast and ovarian cancer often occur at an unusually young age.2

Although ACOG recommends that annual screening mammograms begin at age 40,3 daughters of women who are known gene-mutation carriers should begin screening mammography at age 25.4 The ability of these women to make informed health decisions depends on their becoming knowledgeable about the risks, the availability of genetic testing, and options for screening and risk-reducing prophylactic surgery.

Although the daughters expressed worry about hereditary breast cancer, they had limited understanding of screening and risk-reduction options. If they did have the information, Dr. Patenaude’s study found, the young women were often afraid to have the testing.2,4

“Young, high-risk women have little knowledge about the probabilities and options for managing the cancers for which their risks are remarkably increased. Further, many report intense anxiety related to their potential cancer development,” said Dr. Patenaude of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. “These data support the need and can provide the foundation for the development of targeted educational materials to reduce that anxiety and ultimately improve participation in effective screening and risk-reducing interventions that can improve survival and quality of life for these young women.”2

The Era of Hope Conference provides a forum for scientists and clinicians from a variety of disciplines to join breast cancer survivors and advocates to discuss the advances made by the Congressionally Directed Breast Cancer Research Programs BCRP awardees, and to identify innovative, high-impact approaches for future research. Recognized as one of the premiere breast cancer research meetings.5

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Breast cancer risk by age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/age.htm. Updated August 13, 2010. Accessed August 10, 2011.

2. What Do Young Adult Daughters of BRCA Mutation Carriers Know About Hereditary Risk and How Much Do They Worry [press release]. http://eraofhopemediapage.org/press-releases-2/. Accessed August 9, 2011.

3. Yates J. ACOG recommends that annual screening mammograms begin at age 40. OBG Manage. 2011;23(8). http://www.obgmanagement.com/article_pages.asp?filename="2310OBG_NEWS_Daughters" aid=9816. Accessed August 9, 2011.

4. What Do Young Adult Daughters of BRCA Mutation Carriers Know About Hereditary Risk and How Much Do They Worry [Webinar]. Era of Hope Press Briefing. http://eraofhopemediapage.org/Era%20of%20Hope%20Press%20Conference%20Undedited/lib/playback.html. Published August 3, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2011.

5. Era of Hope 2011. CDMRPCures.org Web site. https://cdmrpcures.org/ocs/index.php/eoh/eoh2011. Accessed August 9, 2011.

1. Breast cancer risk by age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/age.htm. Updated August 13, 2010. Accessed August 10, 2011.

2. What Do Young Adult Daughters of BRCA Mutation Carriers Know About Hereditary Risk and How Much Do They Worry [press release]. http://eraofhopemediapage.org/press-releases-2/. Accessed August 9, 2011.

3. Yates J. ACOG recommends that annual screening mammograms begin at age 40. OBG Manage. 2011;23(8). http://www.obgmanagement.com/article_pages.asp?filename="2310OBG_NEWS_Daughters" aid=9816. Accessed August 9, 2011.

4. What Do Young Adult Daughters of BRCA Mutation Carriers Know About Hereditary Risk and How Much Do They Worry [Webinar]. Era of Hope Press Briefing. http://eraofhopemediapage.org/Era%20of%20Hope%20Press%20Conference%20Undedited/lib/playback.html. Published August 3, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2011.

5. Era of Hope 2011. CDMRPCures.org Web site. https://cdmrpcures.org/ocs/index.php/eoh/eoh2011. Accessed August 9, 2011.

Rate of hospitalization for pregnancy-related stroke jumps 50% over 12 years

Stroke may be an unusual event in pregnancy, but it’s becoming less of a rarity, according to a new study.1 Hospitalizations related to stroke in pregnancy increased 54% over the past dozen years, from 4,085 in 1994–95 to 6,293 in 2006–07.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyzed a large national database of 5 to 8 million discharges from 1,000 hospitals and compared the rates of stroke from 1994–95 with the rates from 2006–07 in women who were pregnant, delivering a baby, and who had recently given birth.

In women who were pregnant, the rate of hospitalization for stroke rose 47%. The rate during the 12 weeks after delivery rose 83%. The rate remained stable for hospitalizations that occurred during the time immediately surrounding childbirth.

“I am surprised at the magnitude of the increase, which is substantial,” said Elena V. Kuklina, MD, PhD, lead author of the study and senior service fellow and epidemiologist at the CDC’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention in Atlanta, Ga. “Our results indicate an urgent need to take a closer look. Stroke is such a debilitating condition. We need to put more effort into prevention.”

“Now more and more women entering pregnancy already have some type of risk factor for stroke, such as obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, or congenital heart disease. Since pregnancy by itself is a risk factor, if you have one of these other stroke risk factors, it doubles the risk.”

Not surprisingly, the prevalence of high blood pressure also rose over the 12-year period. In 1994–95, the rate was:

- 11.3% in antepartum women

- 23.4% in women at or near delivery

- 27.8% in women within 12 weeks after delivery.

In 2006–07, the rate was:

- 17% in antepartum women

- 28.5% in women at or near delivery

- 40.9% in women within 12 weeks after delivery.

“It’s best for women to enter pregnancy with ideal cardiovascular health, without additional risk factors,” Kuklina said. She recommends development of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary plan that gives doctors and patients guidelines for appropriate monitoring and care before, during, and after childbirth.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. Kuklina EV, Tong X, Bansil P, George MG, Callaghan WM. Trends in pregnancy hospitalizations that included a stroke in the United States from 1994 to 2007: Reasons for concern? Stroke. 2011;42(9):2564-2570.

Stroke may be an unusual event in pregnancy, but it’s becoming less of a rarity, according to a new study.1 Hospitalizations related to stroke in pregnancy increased 54% over the past dozen years, from 4,085 in 1994–95 to 6,293 in 2006–07.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyzed a large national database of 5 to 8 million discharges from 1,000 hospitals and compared the rates of stroke from 1994–95 with the rates from 2006–07 in women who were pregnant, delivering a baby, and who had recently given birth.

In women who were pregnant, the rate of hospitalization for stroke rose 47%. The rate during the 12 weeks after delivery rose 83%. The rate remained stable for hospitalizations that occurred during the time immediately surrounding childbirth.

“I am surprised at the magnitude of the increase, which is substantial,” said Elena V. Kuklina, MD, PhD, lead author of the study and senior service fellow and epidemiologist at the CDC’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention in Atlanta, Ga. “Our results indicate an urgent need to take a closer look. Stroke is such a debilitating condition. We need to put more effort into prevention.”

“Now more and more women entering pregnancy already have some type of risk factor for stroke, such as obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, or congenital heart disease. Since pregnancy by itself is a risk factor, if you have one of these other stroke risk factors, it doubles the risk.”

Not surprisingly, the prevalence of high blood pressure also rose over the 12-year period. In 1994–95, the rate was:

- 11.3% in antepartum women

- 23.4% in women at or near delivery

- 27.8% in women within 12 weeks after delivery.

In 2006–07, the rate was:

- 17% in antepartum women

- 28.5% in women at or near delivery

- 40.9% in women within 12 weeks after delivery.

“It’s best for women to enter pregnancy with ideal cardiovascular health, without additional risk factors,” Kuklina said. She recommends development of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary plan that gives doctors and patients guidelines for appropriate monitoring and care before, during, and after childbirth.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Stroke may be an unusual event in pregnancy, but it’s becoming less of a rarity, according to a new study.1 Hospitalizations related to stroke in pregnancy increased 54% over the past dozen years, from 4,085 in 1994–95 to 6,293 in 2006–07.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyzed a large national database of 5 to 8 million discharges from 1,000 hospitals and compared the rates of stroke from 1994–95 with the rates from 2006–07 in women who were pregnant, delivering a baby, and who had recently given birth.

In women who were pregnant, the rate of hospitalization for stroke rose 47%. The rate during the 12 weeks after delivery rose 83%. The rate remained stable for hospitalizations that occurred during the time immediately surrounding childbirth.

“I am surprised at the magnitude of the increase, which is substantial,” said Elena V. Kuklina, MD, PhD, lead author of the study and senior service fellow and epidemiologist at the CDC’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention in Atlanta, Ga. “Our results indicate an urgent need to take a closer look. Stroke is such a debilitating condition. We need to put more effort into prevention.”

“Now more and more women entering pregnancy already have some type of risk factor for stroke, such as obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, or congenital heart disease. Since pregnancy by itself is a risk factor, if you have one of these other stroke risk factors, it doubles the risk.”

Not surprisingly, the prevalence of high blood pressure also rose over the 12-year period. In 1994–95, the rate was:

- 11.3% in antepartum women

- 23.4% in women at or near delivery

- 27.8% in women within 12 weeks after delivery.

In 2006–07, the rate was:

- 17% in antepartum women

- 28.5% in women at or near delivery

- 40.9% in women within 12 weeks after delivery.

“It’s best for women to enter pregnancy with ideal cardiovascular health, without additional risk factors,” Kuklina said. She recommends development of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary plan that gives doctors and patients guidelines for appropriate monitoring and care before, during, and after childbirth.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. Kuklina EV, Tong X, Bansil P, George MG, Callaghan WM. Trends in pregnancy hospitalizations that included a stroke in the United States from 1994 to 2007: Reasons for concern? Stroke. 2011;42(9):2564-2570.

Reference

1. Kuklina EV, Tong X, Bansil P, George MG, Callaghan WM. Trends in pregnancy hospitalizations that included a stroke in the United States from 1994 to 2007: Reasons for concern? Stroke. 2011;42(9):2564-2570.

Correcting pelvic organ prolapse with robotic sacrocolpopexy

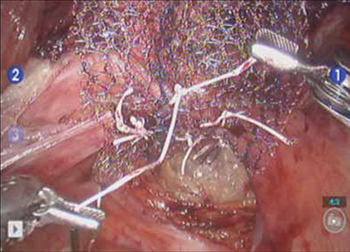

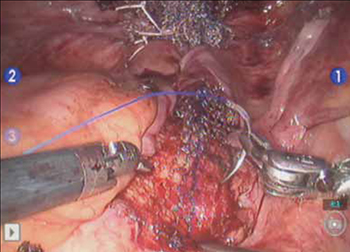

- Promontory dissection and creation of the retroperitoneal tunnel

- Dissection of the rectovaginal and vesicovaginal spaces

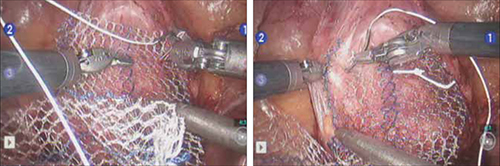

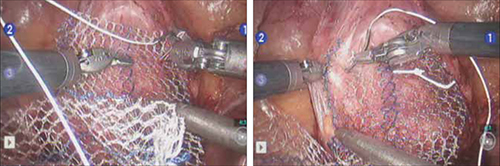

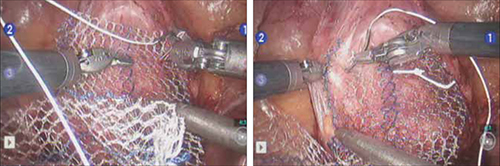

- Attachment of y-mesh to vagina: Start anteriorly

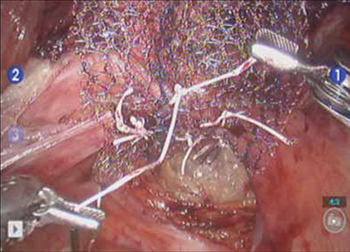

- Posterior y-mesh attachment

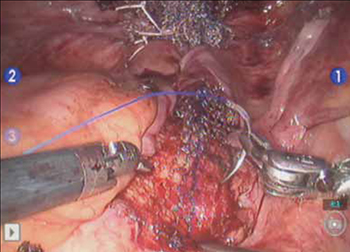

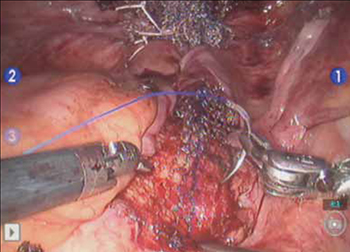

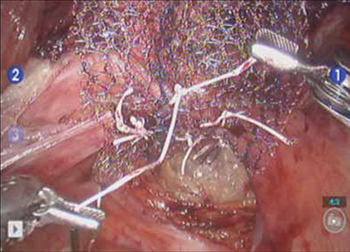

- Attachment of mesh to sacral promontory

These videos were provided by Catherine A. Matthews, MD.

Recent years have seen growing recognition that adequate support of the vaginal apex is an essential component of durable surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse.1,2 Sacrocolpopexy is now considered the gold standard for repair of Level-1 defects of pelvic support, providing excellent long-term results.3-5

A recent randomized, controlled trial demonstrated the superior efficacy of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy to a total vaginal mesh procedure in women who have vaginal vault prolapse—further evidence that sacrocolpopexy is the procedure of choice for these patients.6

The advantages of sacrocolpopexy include:

- reduced risk of mesh exposure, compared to insertion of vaginal mesh

- preservation of vaginal length

- reduced risk of re-operation for symptomatic recurrent prolapse

- reduced risk of de novo dyspareunia secondary to contraction of mesh.

Obstacles. Although a small number of surgeons are able to accomplish sacrocolpopexy using standard laparoscopic techniques, most of these procedures are still performed by laparotomy because the extensive suturing and knot-tying present a surgical challenge. Open sacrocolpopexy has disadvantages, too, including more pain, longer recovery, and longer length of stay.7-9

With the introduction of the da Vinci robot (Intuitive Surgical), the feasibility of having more surgeons perform this operation using a reproducible, minimally-invasive technique is much greater. The steep learning curve associated with standard laparoscopy in regard to mastering intracorporeal knot-tying and suturing is greatly diminished by articulating instruments. This makes robotic sacrocolpopexy an accessible option for all gynecologic surgeons who treat women with pelvic organ prolapse.

In this article, I detail the steps—with tips and tricks from my experience—to completing an efficient robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy—modeled exactly after the open technique—that utilizes a y-shaped polypropylene mesh graft. Included is capsule advice from OBG Management’s coding consultant on obtaining reimbursement for robotic procedures (see “ Coding tips for robotic sacrocolpopexy”).

- Two proficient tableside assistants are needed

- Use steep Trendelenburg to remove the bowel from the operative field

- A fan retractor is necessary in some cases to gain access to the promontory

- Correct identification of the sacral promontory is key

- In the absence of haptic feedback, novice surgeons must be aware of the potential danger in dissecting too far laterally and entering the common iliac vessels

- Y-shaped grafts should be fashioned individually

- Know the exit point of the needle at the promontory

- Adequate spacing between the robotic arms is essential to avoiding interference among instruments during the procedure.

Details of the procedure

1. Surgical preparation, set-up

The patient completes a bowel prep using two bottles of magnesium citrate and taking only clear liquids 1 day before surgery. Although mechanical bowel cleansing has not been shown to decrease operative morbidity, manipulation and retraction of the sigmoid colon may be easier with the bowel empty.

Perioperative antibiotics are administered 30 minutes prior to the procedure. Heparin, 5,000 U, is injected subcutaneously for thromboprophylaxis as the patient is en route to the operating suite.

The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, buttocks extending one inch over the end of the operating table. The table should be covered with egg-crate foam to avoid having her slip down while in steep Trendelenburg position.

After the patient is prepped and draped, a Foley catheter is placed into the bladder. EEA sizers (Covidien) are inserted into the vagina and rectum.

Two experienced surgical assistants are necessary:

- One on the patient’s right side to assist with tissue retraction and introduction of suture material

- Another seated between the patient’s legs to provide adequate vaginal and rectal manipulation during surgery.

2. Port placement, docking, and instrumentation

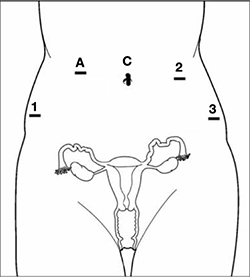

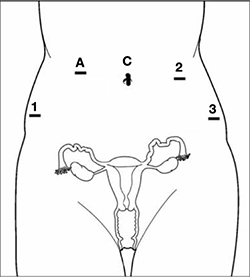

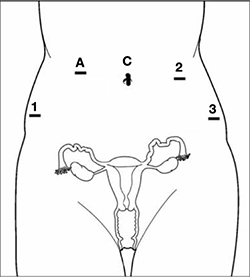

Pneumoperitoneum is obtained with a Veress needle. Five trocars are then placed (FIGURE 1).

Careful port placement is integral to the success of this procedure because:

- Inadequate distance between robotic arms and the camera results in arm collisions and interference