User login

Technology and the evolution of medical knowledge: What’s happening in the background

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers. It may not be difficult to store up in the mind a vast quantity of facts within a comparatively short time, but the ability to form judgments requires the severe discipline of hard work and the tempering heat of experience and maturity.” – Calvin Coolidge

The information we use every day in patient care comes from one of two sources: personal experience (our own or that of another clinician) or a research study. Up until a hundred years ago, medicine was primarily a trade in which more experienced clinicians passed along their wisdom to younger clinicians, teaching them the things that they had learned during their long and difficult careers. Knowledge accrued slowly, influenced by the biased observations of each practicing doctor. People tended to remember their successes or unusual outcomes more than their failures or ordinary outcomes. Eventually, doctors realized that their knowledge base would be more accurate and accumulate more efficiently if they looked at the outcomes of many patients given the same treatment. Thus, the observational trial emerged.

As promising and important as the dawn of observational research was, it quickly became apparent that these trials had important limitations. The most notable limitations were the potential for bias and confounding variables to influence the results. Bias occurs when the opinion of the researcher influences how the result is interpreted. Confounders occur when an outcome is generated by some unexpected aspect of the patient, environment, or medication, rather than the thing that is being studied. An example of this might be a study that finds a higher mortality rate in a city by the sea than a city located inland. From these results, one might initially conclude that the sea is unhealthy. After realizing more retired people lived in the city by the sea; however, an individual would probably change his or her mind. In this example, the older age of this city’s population would be a confounding variable that drove the increased mortality in the city by the sea.

To solve the inherent problems with observational trials, the randomized, controlled trial was developed. Our reliance on information from RCTs runs so deep that it is hard to believe that the first modern clinical trial was not reported until 1948, in a paper on streptomycin in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. It followed that faith in the randomized, controlled trial reached almost religious proportions, and the belief that information that does not come from an RCT should not be relied on was held by many, until recently. Why have things changed and what does this have to do with technology?

The first is an increasing recognition that, for all of their advantages, randomized trials have one nagging but critical limitation – generalizability. Randomized trials have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. We do not have such inclusion and exclusion criteria when we take care of patients in our offices. For example, a recent trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.), entitled “Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer,” concluded that apixaban therapy resulted in a lower rate of venous thromboembolism than did placebo in patients starting chemotherapy for cancer. This was a large trial with more than 500 patients enrolled, and it reached an important conclusion with significant clinical implications. When you look at the details of the article, more than 1,800 patients were assessed to find the 500 patients who were eventually included in the trial. This is fairly typical of clinical trials and raises an important point: We need to be careful about how well the results of these clinical trials can be generalized to apply to the patient in front of us. This leads us to the second development that is something happening behind the scenes that each of us has contributed to.

Real-world research

As we see each patient and type information into the EHR, we add to an enormous database of medical information. That database is increasingly being used to advance our knowledge of how medicines actually work in the real world with real patients, and has already started providing answers that supplement, clarify, and even change our perspectives. The information will provide observations derived from real populations that have not been selected or influenced by the way in which a study is conducted. This new field of research is called “real-world research.”

An example of the difference between randomized controlled trial results and real-world research was published in Diabetes Care. This article examined the effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors vs. glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in the treatment of patients with diabetes. The goal of the study was to assess the difference in change in hemoglobin A1c between real-world evidence and randomized-trial evidence after initiation of a GLP-1 RA or a DPP-4 inhibitor. In RCTs, GLP-1 RAs decreased HbA1c by about 1.3% while DPP-4 inhibitors decreased HbA1c by about 0.68% (i.e., DPP-4 inhibitors were about half as effective). However, when the effects of these two diabetes drugs were examined using clinical databases in the real world, the two classes of medications had almost the same effect, each decreasing HbA1c by about 0.5%. This difference between RCT and real-world evidence might have been caused by the differential adherence to the two classes of medications, one being an injectable with significant GI side effects, and the other being a pill with few side effects.

The important take-home point is that we are now all contributing to a massive database that can be queried to give quicker, more accurate, more relevant information. Along with personal experience and randomized trials, this third source of clinical information, when used with wisdom, will provide us with the information we need to take ever better care of patients.

References

Carls GS et al. Understanding the gap between efficacy in randomized controlled trials and effectiveness in real-world use of GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1469-78.

Blonde L et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018 Nov;35:1763-74.

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers. It may not be difficult to store up in the mind a vast quantity of facts within a comparatively short time, but the ability to form judgments requires the severe discipline of hard work and the tempering heat of experience and maturity.” – Calvin Coolidge

The information we use every day in patient care comes from one of two sources: personal experience (our own or that of another clinician) or a research study. Up until a hundred years ago, medicine was primarily a trade in which more experienced clinicians passed along their wisdom to younger clinicians, teaching them the things that they had learned during their long and difficult careers. Knowledge accrued slowly, influenced by the biased observations of each practicing doctor. People tended to remember their successes or unusual outcomes more than their failures or ordinary outcomes. Eventually, doctors realized that their knowledge base would be more accurate and accumulate more efficiently if they looked at the outcomes of many patients given the same treatment. Thus, the observational trial emerged.

As promising and important as the dawn of observational research was, it quickly became apparent that these trials had important limitations. The most notable limitations were the potential for bias and confounding variables to influence the results. Bias occurs when the opinion of the researcher influences how the result is interpreted. Confounders occur when an outcome is generated by some unexpected aspect of the patient, environment, or medication, rather than the thing that is being studied. An example of this might be a study that finds a higher mortality rate in a city by the sea than a city located inland. From these results, one might initially conclude that the sea is unhealthy. After realizing more retired people lived in the city by the sea; however, an individual would probably change his or her mind. In this example, the older age of this city’s population would be a confounding variable that drove the increased mortality in the city by the sea.

To solve the inherent problems with observational trials, the randomized, controlled trial was developed. Our reliance on information from RCTs runs so deep that it is hard to believe that the first modern clinical trial was not reported until 1948, in a paper on streptomycin in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. It followed that faith in the randomized, controlled trial reached almost religious proportions, and the belief that information that does not come from an RCT should not be relied on was held by many, until recently. Why have things changed and what does this have to do with technology?

The first is an increasing recognition that, for all of their advantages, randomized trials have one nagging but critical limitation – generalizability. Randomized trials have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. We do not have such inclusion and exclusion criteria when we take care of patients in our offices. For example, a recent trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.), entitled “Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer,” concluded that apixaban therapy resulted in a lower rate of venous thromboembolism than did placebo in patients starting chemotherapy for cancer. This was a large trial with more than 500 patients enrolled, and it reached an important conclusion with significant clinical implications. When you look at the details of the article, more than 1,800 patients were assessed to find the 500 patients who were eventually included in the trial. This is fairly typical of clinical trials and raises an important point: We need to be careful about how well the results of these clinical trials can be generalized to apply to the patient in front of us. This leads us to the second development that is something happening behind the scenes that each of us has contributed to.

Real-world research

As we see each patient and type information into the EHR, we add to an enormous database of medical information. That database is increasingly being used to advance our knowledge of how medicines actually work in the real world with real patients, and has already started providing answers that supplement, clarify, and even change our perspectives. The information will provide observations derived from real populations that have not been selected or influenced by the way in which a study is conducted. This new field of research is called “real-world research.”

An example of the difference between randomized controlled trial results and real-world research was published in Diabetes Care. This article examined the effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors vs. glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in the treatment of patients with diabetes. The goal of the study was to assess the difference in change in hemoglobin A1c between real-world evidence and randomized-trial evidence after initiation of a GLP-1 RA or a DPP-4 inhibitor. In RCTs, GLP-1 RAs decreased HbA1c by about 1.3% while DPP-4 inhibitors decreased HbA1c by about 0.68% (i.e., DPP-4 inhibitors were about half as effective). However, when the effects of these two diabetes drugs were examined using clinical databases in the real world, the two classes of medications had almost the same effect, each decreasing HbA1c by about 0.5%. This difference between RCT and real-world evidence might have been caused by the differential adherence to the two classes of medications, one being an injectable with significant GI side effects, and the other being a pill with few side effects.

The important take-home point is that we are now all contributing to a massive database that can be queried to give quicker, more accurate, more relevant information. Along with personal experience and randomized trials, this third source of clinical information, when used with wisdom, will provide us with the information we need to take ever better care of patients.

References

Carls GS et al. Understanding the gap between efficacy in randomized controlled trials and effectiveness in real-world use of GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1469-78.

Blonde L et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018 Nov;35:1763-74.

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers. It may not be difficult to store up in the mind a vast quantity of facts within a comparatively short time, but the ability to form judgments requires the severe discipline of hard work and the tempering heat of experience and maturity.” – Calvin Coolidge

The information we use every day in patient care comes from one of two sources: personal experience (our own or that of another clinician) or a research study. Up until a hundred years ago, medicine was primarily a trade in which more experienced clinicians passed along their wisdom to younger clinicians, teaching them the things that they had learned during their long and difficult careers. Knowledge accrued slowly, influenced by the biased observations of each practicing doctor. People tended to remember their successes or unusual outcomes more than their failures or ordinary outcomes. Eventually, doctors realized that their knowledge base would be more accurate and accumulate more efficiently if they looked at the outcomes of many patients given the same treatment. Thus, the observational trial emerged.

As promising and important as the dawn of observational research was, it quickly became apparent that these trials had important limitations. The most notable limitations were the potential for bias and confounding variables to influence the results. Bias occurs when the opinion of the researcher influences how the result is interpreted. Confounders occur when an outcome is generated by some unexpected aspect of the patient, environment, or medication, rather than the thing that is being studied. An example of this might be a study that finds a higher mortality rate in a city by the sea than a city located inland. From these results, one might initially conclude that the sea is unhealthy. After realizing more retired people lived in the city by the sea; however, an individual would probably change his or her mind. In this example, the older age of this city’s population would be a confounding variable that drove the increased mortality in the city by the sea.

To solve the inherent problems with observational trials, the randomized, controlled trial was developed. Our reliance on information from RCTs runs so deep that it is hard to believe that the first modern clinical trial was not reported until 1948, in a paper on streptomycin in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. It followed that faith in the randomized, controlled trial reached almost religious proportions, and the belief that information that does not come from an RCT should not be relied on was held by many, until recently. Why have things changed and what does this have to do with technology?

The first is an increasing recognition that, for all of their advantages, randomized trials have one nagging but critical limitation – generalizability. Randomized trials have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. We do not have such inclusion and exclusion criteria when we take care of patients in our offices. For example, a recent trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.), entitled “Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer,” concluded that apixaban therapy resulted in a lower rate of venous thromboembolism than did placebo in patients starting chemotherapy for cancer. This was a large trial with more than 500 patients enrolled, and it reached an important conclusion with significant clinical implications. When you look at the details of the article, more than 1,800 patients were assessed to find the 500 patients who were eventually included in the trial. This is fairly typical of clinical trials and raises an important point: We need to be careful about how well the results of these clinical trials can be generalized to apply to the patient in front of us. This leads us to the second development that is something happening behind the scenes that each of us has contributed to.

Real-world research

As we see each patient and type information into the EHR, we add to an enormous database of medical information. That database is increasingly being used to advance our knowledge of how medicines actually work in the real world with real patients, and has already started providing answers that supplement, clarify, and even change our perspectives. The information will provide observations derived from real populations that have not been selected or influenced by the way in which a study is conducted. This new field of research is called “real-world research.”

An example of the difference between randomized controlled trial results and real-world research was published in Diabetes Care. This article examined the effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors vs. glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in the treatment of patients with diabetes. The goal of the study was to assess the difference in change in hemoglobin A1c between real-world evidence and randomized-trial evidence after initiation of a GLP-1 RA or a DPP-4 inhibitor. In RCTs, GLP-1 RAs decreased HbA1c by about 1.3% while DPP-4 inhibitors decreased HbA1c by about 0.68% (i.e., DPP-4 inhibitors were about half as effective). However, when the effects of these two diabetes drugs were examined using clinical databases in the real world, the two classes of medications had almost the same effect, each decreasing HbA1c by about 0.5%. This difference between RCT and real-world evidence might have been caused by the differential adherence to the two classes of medications, one being an injectable with significant GI side effects, and the other being a pill with few side effects.

The important take-home point is that we are now all contributing to a massive database that can be queried to give quicker, more accurate, more relevant information. Along with personal experience and randomized trials, this third source of clinical information, when used with wisdom, will provide us with the information we need to take ever better care of patients.

References

Carls GS et al. Understanding the gap between efficacy in randomized controlled trials and effectiveness in real-world use of GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1469-78.

Blonde L et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018 Nov;35:1763-74.

Electronic health records and the lost power of prose

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass,” Anton Chekhov

In March 2006, four programmers turned entrepreneurs launched Twitter. This revolutionary tool experienced a monumental growth in scale over the next 10 years from a handful of users sharing a few thousand messages (known as “tweets”) each day to a global social network of over 300 million users valued at over $25 billion dollars. In fact, on Election Day 2016, Twitter was the No. 1 source of breaking news1, and it has been used as a launchpad for everything from social activism to national revolutions.

When Twitter was first conceived, it was designed to operate through wireless phone carriers’ SMS messaging functionality (aka “via text message”). SMS messages are limited to just 160 characters, so Twitter’s creators decided to restrict tweets to 140 characters, allowing 20 characters for a username. This decision created a necessity for communication efficiency that harks back to the days of the telegraph. From the liberal use of contractions and abbreviations to the tireless search for the shortest synonyms possible, Twitter users have employed countless techniques to enable them to say more with less. While clever and creative, this extreme verbal austerity has pervaded other media as well, becoming the hallmark literary style of the current generation.

Contemporaneous with the Twitter revolution, the medical field has allowed technology to dramatically change its style of communication as well, but in the opposite way. We have become far less efficient in our use of words, yet we seem to be doing a really poor job of expressing ourselves.

Saying less with more

I was once asked to provide expert testimony in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Working in support of the defense, I endured question after question from the plaintiff’s legal team as they picked apart every aspect of the case. Of particular interest was the physician’s documentation. Sadly – yet perhaps unsurprisingly – it was poor. The defendant had clearly used an EHR template and clicked checkboxes to create his note, documenting history, physical exam, assessment, and plan without having typed a single word. While adequate for billing purposes, the note was missing any narrative that could communicate the story of what had transpired during the patient’s visit. Sure, the presenting symptoms and vital signs were there, but the no description of the patient’s appearance had been recorded? What had the physician been thinking? What unspoken messages had led the physician to make the decisions he had made?

Like Twitter, the dawn of EHRs created an entirely new form of communication, but instead of limiting the content of physicians’ notes it expanded it. Objectively, this has made for more complete notes. Subjectively, this has led to notes packed with data, yet devoid of meaningful narrative. While handwritten notes from the previous generation were brief, they included the most important elements of the patient’s history and often the physician’s thought process in forming the differential. The electronically generated notes of today are quite the opposite; they are dense, yet far from illuminating. A clinician referring back to the record might have tremendous difficulty discerning salient features amidst all of the “note bloat.”This puts the patient (and the provider, as in the case above) at risk. Details may be present, but the diagnosis will be missed without the story that ties them all together.

Writing a new chapter

Physicians hoping to create meaningful notes are often stymied by the technology at their disposal or the demands placed on their time. These issues, combined with an ever-growing number of regulatory requirements, are what led to the decay of narrative in the first place. As a result, doctors are looking for alternative ways to buck the trend and bring patients’ stories back to their medical records. These methods are often expensive or involved, but in many cases they dramatically improve quality and efficiency.

An example of a tool that allows doctors to achieve these goals is speech recognition technology. Instead of typing or clicking, physicians dictate into the EHR, creating notes that are typically richer and more akin to a story than a list of symptoms or data points. When voice-to-text is properly deployed and utilized, documentation improves along with efficiency. Alternately, many providers are now employing scribes to accompany them in the exam room and complete the medical record. Taking this step leads to more descriptive notes, better productivity, and happier providers. The use of scribes also seems to result in happier patients, who report better therapeutic interactions when their doctors aren’t typing or staring at a computer screen.

The above-mentioned methods for recording information about a patient during a visit may be too expensive or complicated for some providers, but there are other simple techniques that can be used without incurring additional cost or resources. Previsit planning is one such possibility. By reviewing patient charts in advance of appointments, physicians can look over results, identify preventive health gaps, and anticipate follow-up needs and medication refills. They can then create skeleton notes and prepopulate orders to reduce the documentation burden during the visit. While time consuming at first, physicians have reported this practice actually saves time in the long run and allows them to focus on recording the patient narrative during the visit.

Another strategy is even more simple in concept, though may seem counter-intuitive at first: get better acquainted with the electronic records system. That is, take the time to really learn and understand the tools designed to improve productivity that are available in your EHR, then use them judiciously; take advantage of templates and macros when they’ll make you more efficient yet won’t inhibit your ability to tell the patient’s story; embrace optimization but don’t compromise on narrative. By carefully choosing your words, you’ll paint a clearer picture of every patient and enable safer and more personalized care.

Reference

1. “For Election Day Influence, Twitter Ruled Social Media” New York Times. Nov. 8, 2016.

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass,” Anton Chekhov

In March 2006, four programmers turned entrepreneurs launched Twitter. This revolutionary tool experienced a monumental growth in scale over the next 10 years from a handful of users sharing a few thousand messages (known as “tweets”) each day to a global social network of over 300 million users valued at over $25 billion dollars. In fact, on Election Day 2016, Twitter was the No. 1 source of breaking news1, and it has been used as a launchpad for everything from social activism to national revolutions.

When Twitter was first conceived, it was designed to operate through wireless phone carriers’ SMS messaging functionality (aka “via text message”). SMS messages are limited to just 160 characters, so Twitter’s creators decided to restrict tweets to 140 characters, allowing 20 characters for a username. This decision created a necessity for communication efficiency that harks back to the days of the telegraph. From the liberal use of contractions and abbreviations to the tireless search for the shortest synonyms possible, Twitter users have employed countless techniques to enable them to say more with less. While clever and creative, this extreme verbal austerity has pervaded other media as well, becoming the hallmark literary style of the current generation.

Contemporaneous with the Twitter revolution, the medical field has allowed technology to dramatically change its style of communication as well, but in the opposite way. We have become far less efficient in our use of words, yet we seem to be doing a really poor job of expressing ourselves.

Saying less with more

I was once asked to provide expert testimony in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Working in support of the defense, I endured question after question from the plaintiff’s legal team as they picked apart every aspect of the case. Of particular interest was the physician’s documentation. Sadly – yet perhaps unsurprisingly – it was poor. The defendant had clearly used an EHR template and clicked checkboxes to create his note, documenting history, physical exam, assessment, and plan without having typed a single word. While adequate for billing purposes, the note was missing any narrative that could communicate the story of what had transpired during the patient’s visit. Sure, the presenting symptoms and vital signs were there, but the no description of the patient’s appearance had been recorded? What had the physician been thinking? What unspoken messages had led the physician to make the decisions he had made?

Like Twitter, the dawn of EHRs created an entirely new form of communication, but instead of limiting the content of physicians’ notes it expanded it. Objectively, this has made for more complete notes. Subjectively, this has led to notes packed with data, yet devoid of meaningful narrative. While handwritten notes from the previous generation were brief, they included the most important elements of the patient’s history and often the physician’s thought process in forming the differential. The electronically generated notes of today are quite the opposite; they are dense, yet far from illuminating. A clinician referring back to the record might have tremendous difficulty discerning salient features amidst all of the “note bloat.”This puts the patient (and the provider, as in the case above) at risk. Details may be present, but the diagnosis will be missed without the story that ties them all together.

Writing a new chapter

Physicians hoping to create meaningful notes are often stymied by the technology at their disposal or the demands placed on their time. These issues, combined with an ever-growing number of regulatory requirements, are what led to the decay of narrative in the first place. As a result, doctors are looking for alternative ways to buck the trend and bring patients’ stories back to their medical records. These methods are often expensive or involved, but in many cases they dramatically improve quality and efficiency.

An example of a tool that allows doctors to achieve these goals is speech recognition technology. Instead of typing or clicking, physicians dictate into the EHR, creating notes that are typically richer and more akin to a story than a list of symptoms or data points. When voice-to-text is properly deployed and utilized, documentation improves along with efficiency. Alternately, many providers are now employing scribes to accompany them in the exam room and complete the medical record. Taking this step leads to more descriptive notes, better productivity, and happier providers. The use of scribes also seems to result in happier patients, who report better therapeutic interactions when their doctors aren’t typing or staring at a computer screen.

The above-mentioned methods for recording information about a patient during a visit may be too expensive or complicated for some providers, but there are other simple techniques that can be used without incurring additional cost or resources. Previsit planning is one such possibility. By reviewing patient charts in advance of appointments, physicians can look over results, identify preventive health gaps, and anticipate follow-up needs and medication refills. They can then create skeleton notes and prepopulate orders to reduce the documentation burden during the visit. While time consuming at first, physicians have reported this practice actually saves time in the long run and allows them to focus on recording the patient narrative during the visit.

Another strategy is even more simple in concept, though may seem counter-intuitive at first: get better acquainted with the electronic records system. That is, take the time to really learn and understand the tools designed to improve productivity that are available in your EHR, then use them judiciously; take advantage of templates and macros when they’ll make you more efficient yet won’t inhibit your ability to tell the patient’s story; embrace optimization but don’t compromise on narrative. By carefully choosing your words, you’ll paint a clearer picture of every patient and enable safer and more personalized care.

Reference

1. “For Election Day Influence, Twitter Ruled Social Media” New York Times. Nov. 8, 2016.

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass,” Anton Chekhov

In March 2006, four programmers turned entrepreneurs launched Twitter. This revolutionary tool experienced a monumental growth in scale over the next 10 years from a handful of users sharing a few thousand messages (known as “tweets”) each day to a global social network of over 300 million users valued at over $25 billion dollars. In fact, on Election Day 2016, Twitter was the No. 1 source of breaking news1, and it has been used as a launchpad for everything from social activism to national revolutions.

When Twitter was first conceived, it was designed to operate through wireless phone carriers’ SMS messaging functionality (aka “via text message”). SMS messages are limited to just 160 characters, so Twitter’s creators decided to restrict tweets to 140 characters, allowing 20 characters for a username. This decision created a necessity for communication efficiency that harks back to the days of the telegraph. From the liberal use of contractions and abbreviations to the tireless search for the shortest synonyms possible, Twitter users have employed countless techniques to enable them to say more with less. While clever and creative, this extreme verbal austerity has pervaded other media as well, becoming the hallmark literary style of the current generation.

Contemporaneous with the Twitter revolution, the medical field has allowed technology to dramatically change its style of communication as well, but in the opposite way. We have become far less efficient in our use of words, yet we seem to be doing a really poor job of expressing ourselves.

Saying less with more

I was once asked to provide expert testimony in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Working in support of the defense, I endured question after question from the plaintiff’s legal team as they picked apart every aspect of the case. Of particular interest was the physician’s documentation. Sadly – yet perhaps unsurprisingly – it was poor. The defendant had clearly used an EHR template and clicked checkboxes to create his note, documenting history, physical exam, assessment, and plan without having typed a single word. While adequate for billing purposes, the note was missing any narrative that could communicate the story of what had transpired during the patient’s visit. Sure, the presenting symptoms and vital signs were there, but the no description of the patient’s appearance had been recorded? What had the physician been thinking? What unspoken messages had led the physician to make the decisions he had made?

Like Twitter, the dawn of EHRs created an entirely new form of communication, but instead of limiting the content of physicians’ notes it expanded it. Objectively, this has made for more complete notes. Subjectively, this has led to notes packed with data, yet devoid of meaningful narrative. While handwritten notes from the previous generation were brief, they included the most important elements of the patient’s history and often the physician’s thought process in forming the differential. The electronically generated notes of today are quite the opposite; they are dense, yet far from illuminating. A clinician referring back to the record might have tremendous difficulty discerning salient features amidst all of the “note bloat.”This puts the patient (and the provider, as in the case above) at risk. Details may be present, but the diagnosis will be missed without the story that ties them all together.

Writing a new chapter

Physicians hoping to create meaningful notes are often stymied by the technology at their disposal or the demands placed on their time. These issues, combined with an ever-growing number of regulatory requirements, are what led to the decay of narrative in the first place. As a result, doctors are looking for alternative ways to buck the trend and bring patients’ stories back to their medical records. These methods are often expensive or involved, but in many cases they dramatically improve quality and efficiency.

An example of a tool that allows doctors to achieve these goals is speech recognition technology. Instead of typing or clicking, physicians dictate into the EHR, creating notes that are typically richer and more akin to a story than a list of symptoms or data points. When voice-to-text is properly deployed and utilized, documentation improves along with efficiency. Alternately, many providers are now employing scribes to accompany them in the exam room and complete the medical record. Taking this step leads to more descriptive notes, better productivity, and happier providers. The use of scribes also seems to result in happier patients, who report better therapeutic interactions when their doctors aren’t typing or staring at a computer screen.

The above-mentioned methods for recording information about a patient during a visit may be too expensive or complicated for some providers, but there are other simple techniques that can be used without incurring additional cost or resources. Previsit planning is one such possibility. By reviewing patient charts in advance of appointments, physicians can look over results, identify preventive health gaps, and anticipate follow-up needs and medication refills. They can then create skeleton notes and prepopulate orders to reduce the documentation burden during the visit. While time consuming at first, physicians have reported this practice actually saves time in the long run and allows them to focus on recording the patient narrative during the visit.

Another strategy is even more simple in concept, though may seem counter-intuitive at first: get better acquainted with the electronic records system. That is, take the time to really learn and understand the tools designed to improve productivity that are available in your EHR, then use them judiciously; take advantage of templates and macros when they’ll make you more efficient yet won’t inhibit your ability to tell the patient’s story; embrace optimization but don’t compromise on narrative. By carefully choosing your words, you’ll paint a clearer picture of every patient and enable safer and more personalized care.

Reference

1. “For Election Day Influence, Twitter Ruled Social Media” New York Times. Nov. 8, 2016.

Who is in charge here?

My first patient of the afternoon was a simple hypertension follow-up, or so I thought as I was walking into the room. She was a healthy 50-year-old woman with no medical problems other than her blood pressure, which was measured at 130/76 in the office. Her heart and lungs were normal, she had no chest pain or shortness of breath, and she was taking her medications without any problem. All simple enough. I complimented her on how she was doing, told her to continue her medications, and return in 6 months.

She put up her hand and said, “Wait a minute.”

Then she pulled out her smartphone. She tapped open an app, and handed it to me so I could look at a graph of her home blood pressures. The graph had all of her readings from the last 4 months, taken 2-3 times a day. It had automatically labeled each blood pressure in green, yellow, or red to indicate whether they were normal, higher than normal, or elevated, respectively.

Of course, the app creators had determined that a ‘green’ (normal) systolic pressure was less than 120 mm Hg. Values above that were yellow (higher than normal), until a systolic pressure of 130, at which point they became red (elevated). This is consistent with the most recent American Heart Association guidelines, but these guidelines have been the subject of a lot of controversy. There are many, including myself, who believe that the correct systolic pressure to define hypertension should be 140 for many patients, rather than 130. The app disagrees, and patients using the app see the app’s definition of hypertension every time they enter a blood pressure. In the case of my patient, since normal was indicated only by a systolic of less than 120 (which is a relatively rare event), I had to explain the difference between normal blood pressure and her blood pressure goal, and why the two were not the same.

Later that afternoon I was seeing a 60-year-old male who had electrical cardioversion of his atrial fibrillation 2 weeks prior to the visit. He had been sent home, as is usually the case, on an antiarrhythmic and an oral anticoagulant. He was feeling fine and had not noticed any palpitations, chest discomfort, or shortness of breath. I listened to his heart and lungs, which sounded normal, and I told him it sounded like he was doing well. Then he said, “I have an Apple watch.” I had a feeling I knew what was coming next.

He handed me his iPhone and asked me if I could review his rhythm strips. For those unacquainted with the new Apple watch, all he had to do to obtain those strips was open an EKG app and touch the crown of his watch with a finger from his other hand. This essentially made an electrical connection from his left to right arm, allowing the watch to generate a one-lead EKG tracing. The device then provides a computer-generated rhythm strip and sends that image and an interpretation of it to an iPhone, which is connected to the watch via Bluetooth. These results can then be shared or printed out as a pdf document.

The patient wanted to know if the smartphone’s interpretation of those rhythm strips was correct, and if he was really having frequent asymptomatic recurrence of his atrial fibrillation. Unsurprising to me or anyone who has used one of these (or other) phone-based EKG devices, the watch-generated rhythm strips looked clean and clear and the interpretation was spot on. It correctly identified his frequent asymptomatic episodes of atrial fibrillation. This was important information, which markedly affected his medical care.

These two very different examples are early indications that the way that we will be collecting information will rapidly and radically change over the next few years. It has always been clear that making long-term decisions about the treatment of hypertension based on a single reading in the office setting is not optimal. It has been equally clear that a single office EKG provides a limited snapshot into the frequency of intermittent atrial fibrillation. Deciding how to treat patients has never been easy and many decisions are plagued with ambiguity. Having limited information is a blessing and a curse; it’s quick and easy to review a small amount of data, but there is a nagging recognition that those data are only a distant representation of a patient’s real health outside of the office.

As we move forward we will increasingly have the ability to see a patient’s physiologic parameters where and when those values are most important: during the countless hours when they are not in our offices. The new American Heart Association hypertension guideline, issued in late 2017, has placed increased emphasis on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Determining how to use all this new information will be a challenge. It will take time to become comfortable with interpreting and making sense of an incredible number of data points. For example, if a patient checks his blood pressure twice a day for 3 months, his efforts will generate 180 separate blood pressure readings! You can bet there is going to be a good deal of inconsistency in those readings, making interpretation challenging. There will also probably be a few high readings, such as the occasional 190/110, which are likely to cause concern and anxiety in patients. There is little question that the availability of such detailed information holds the potential to allow us to make better decisions. The challenge will be in deciding how to use it to actually improve – not just complicate – patient care.

What are your thoughts on this? Feel free to email us at info@ehrpc.com.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on twitter (@doctornotte).

My first patient of the afternoon was a simple hypertension follow-up, or so I thought as I was walking into the room. She was a healthy 50-year-old woman with no medical problems other than her blood pressure, which was measured at 130/76 in the office. Her heart and lungs were normal, she had no chest pain or shortness of breath, and she was taking her medications without any problem. All simple enough. I complimented her on how she was doing, told her to continue her medications, and return in 6 months.

She put up her hand and said, “Wait a minute.”

Then she pulled out her smartphone. She tapped open an app, and handed it to me so I could look at a graph of her home blood pressures. The graph had all of her readings from the last 4 months, taken 2-3 times a day. It had automatically labeled each blood pressure in green, yellow, or red to indicate whether they were normal, higher than normal, or elevated, respectively.

Of course, the app creators had determined that a ‘green’ (normal) systolic pressure was less than 120 mm Hg. Values above that were yellow (higher than normal), until a systolic pressure of 130, at which point they became red (elevated). This is consistent with the most recent American Heart Association guidelines, but these guidelines have been the subject of a lot of controversy. There are many, including myself, who believe that the correct systolic pressure to define hypertension should be 140 for many patients, rather than 130. The app disagrees, and patients using the app see the app’s definition of hypertension every time they enter a blood pressure. In the case of my patient, since normal was indicated only by a systolic of less than 120 (which is a relatively rare event), I had to explain the difference between normal blood pressure and her blood pressure goal, and why the two were not the same.

Later that afternoon I was seeing a 60-year-old male who had electrical cardioversion of his atrial fibrillation 2 weeks prior to the visit. He had been sent home, as is usually the case, on an antiarrhythmic and an oral anticoagulant. He was feeling fine and had not noticed any palpitations, chest discomfort, or shortness of breath. I listened to his heart and lungs, which sounded normal, and I told him it sounded like he was doing well. Then he said, “I have an Apple watch.” I had a feeling I knew what was coming next.

He handed me his iPhone and asked me if I could review his rhythm strips. For those unacquainted with the new Apple watch, all he had to do to obtain those strips was open an EKG app and touch the crown of his watch with a finger from his other hand. This essentially made an electrical connection from his left to right arm, allowing the watch to generate a one-lead EKG tracing. The device then provides a computer-generated rhythm strip and sends that image and an interpretation of it to an iPhone, which is connected to the watch via Bluetooth. These results can then be shared or printed out as a pdf document.

The patient wanted to know if the smartphone’s interpretation of those rhythm strips was correct, and if he was really having frequent asymptomatic recurrence of his atrial fibrillation. Unsurprising to me or anyone who has used one of these (or other) phone-based EKG devices, the watch-generated rhythm strips looked clean and clear and the interpretation was spot on. It correctly identified his frequent asymptomatic episodes of atrial fibrillation. This was important information, which markedly affected his medical care.

These two very different examples are early indications that the way that we will be collecting information will rapidly and radically change over the next few years. It has always been clear that making long-term decisions about the treatment of hypertension based on a single reading in the office setting is not optimal. It has been equally clear that a single office EKG provides a limited snapshot into the frequency of intermittent atrial fibrillation. Deciding how to treat patients has never been easy and many decisions are plagued with ambiguity. Having limited information is a blessing and a curse; it’s quick and easy to review a small amount of data, but there is a nagging recognition that those data are only a distant representation of a patient’s real health outside of the office.

As we move forward we will increasingly have the ability to see a patient’s physiologic parameters where and when those values are most important: during the countless hours when they are not in our offices. The new American Heart Association hypertension guideline, issued in late 2017, has placed increased emphasis on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Determining how to use all this new information will be a challenge. It will take time to become comfortable with interpreting and making sense of an incredible number of data points. For example, if a patient checks his blood pressure twice a day for 3 months, his efforts will generate 180 separate blood pressure readings! You can bet there is going to be a good deal of inconsistency in those readings, making interpretation challenging. There will also probably be a few high readings, such as the occasional 190/110, which are likely to cause concern and anxiety in patients. There is little question that the availability of such detailed information holds the potential to allow us to make better decisions. The challenge will be in deciding how to use it to actually improve – not just complicate – patient care.

What are your thoughts on this? Feel free to email us at info@ehrpc.com.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on twitter (@doctornotte).

My first patient of the afternoon was a simple hypertension follow-up, or so I thought as I was walking into the room. She was a healthy 50-year-old woman with no medical problems other than her blood pressure, which was measured at 130/76 in the office. Her heart and lungs were normal, she had no chest pain or shortness of breath, and she was taking her medications without any problem. All simple enough. I complimented her on how she was doing, told her to continue her medications, and return in 6 months.

She put up her hand and said, “Wait a minute.”

Then she pulled out her smartphone. She tapped open an app, and handed it to me so I could look at a graph of her home blood pressures. The graph had all of her readings from the last 4 months, taken 2-3 times a day. It had automatically labeled each blood pressure in green, yellow, or red to indicate whether they were normal, higher than normal, or elevated, respectively.

Of course, the app creators had determined that a ‘green’ (normal) systolic pressure was less than 120 mm Hg. Values above that were yellow (higher than normal), until a systolic pressure of 130, at which point they became red (elevated). This is consistent with the most recent American Heart Association guidelines, but these guidelines have been the subject of a lot of controversy. There are many, including myself, who believe that the correct systolic pressure to define hypertension should be 140 for many patients, rather than 130. The app disagrees, and patients using the app see the app’s definition of hypertension every time they enter a blood pressure. In the case of my patient, since normal was indicated only by a systolic of less than 120 (which is a relatively rare event), I had to explain the difference between normal blood pressure and her blood pressure goal, and why the two were not the same.

Later that afternoon I was seeing a 60-year-old male who had electrical cardioversion of his atrial fibrillation 2 weeks prior to the visit. He had been sent home, as is usually the case, on an antiarrhythmic and an oral anticoagulant. He was feeling fine and had not noticed any palpitations, chest discomfort, or shortness of breath. I listened to his heart and lungs, which sounded normal, and I told him it sounded like he was doing well. Then he said, “I have an Apple watch.” I had a feeling I knew what was coming next.

He handed me his iPhone and asked me if I could review his rhythm strips. For those unacquainted with the new Apple watch, all he had to do to obtain those strips was open an EKG app and touch the crown of his watch with a finger from his other hand. This essentially made an electrical connection from his left to right arm, allowing the watch to generate a one-lead EKG tracing. The device then provides a computer-generated rhythm strip and sends that image and an interpretation of it to an iPhone, which is connected to the watch via Bluetooth. These results can then be shared or printed out as a pdf document.

The patient wanted to know if the smartphone’s interpretation of those rhythm strips was correct, and if he was really having frequent asymptomatic recurrence of his atrial fibrillation. Unsurprising to me or anyone who has used one of these (or other) phone-based EKG devices, the watch-generated rhythm strips looked clean and clear and the interpretation was spot on. It correctly identified his frequent asymptomatic episodes of atrial fibrillation. This was important information, which markedly affected his medical care.

These two very different examples are early indications that the way that we will be collecting information will rapidly and radically change over the next few years. It has always been clear that making long-term decisions about the treatment of hypertension based on a single reading in the office setting is not optimal. It has been equally clear that a single office EKG provides a limited snapshot into the frequency of intermittent atrial fibrillation. Deciding how to treat patients has never been easy and many decisions are plagued with ambiguity. Having limited information is a blessing and a curse; it’s quick and easy to review a small amount of data, but there is a nagging recognition that those data are only a distant representation of a patient’s real health outside of the office.

As we move forward we will increasingly have the ability to see a patient’s physiologic parameters where and when those values are most important: during the countless hours when they are not in our offices. The new American Heart Association hypertension guideline, issued in late 2017, has placed increased emphasis on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Determining how to use all this new information will be a challenge. It will take time to become comfortable with interpreting and making sense of an incredible number of data points. For example, if a patient checks his blood pressure twice a day for 3 months, his efforts will generate 180 separate blood pressure readings! You can bet there is going to be a good deal of inconsistency in those readings, making interpretation challenging. There will also probably be a few high readings, such as the occasional 190/110, which are likely to cause concern and anxiety in patients. There is little question that the availability of such detailed information holds the potential to allow us to make better decisions. The challenge will be in deciding how to use it to actually improve – not just complicate – patient care.

What are your thoughts on this? Feel free to email us at info@ehrpc.com.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on twitter (@doctornotte).

Breaking down blockchain: How this novel technology will unfetter health care

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

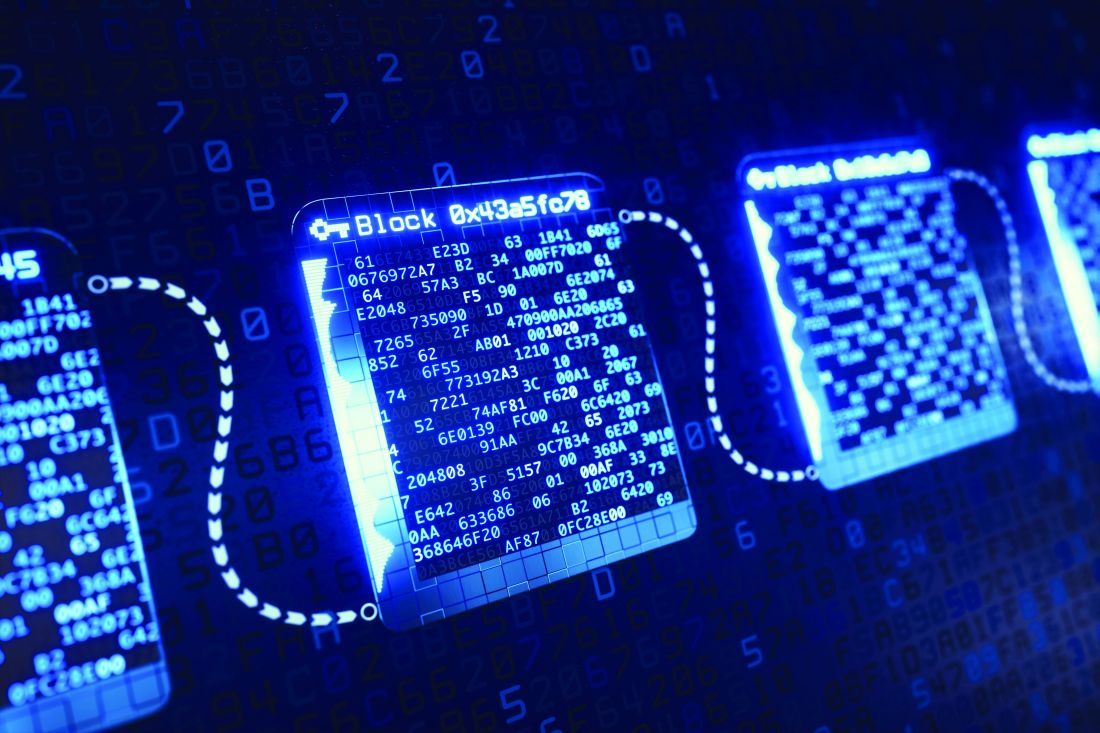

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

Martin Buber, deep learning, and the still soft voice beyond the screen

Life is short, art long, opportunity fleeting. – Hippocrates

The new year provides an opportunity to reflect on old things: to decide what to keep and what to toss out, to contemplate the habits to which we choose to rededicate ourselves, and those we choose to let wane. Over the last few years, while some older physicians have expressed a yearning for the comfort of paper charts, most of us have come to embrace the benefits of the electronic health record. That is a good thing. The EHR offers many advantages over paper, and, like it or not, it’s here to stay.

The other day I was working with a resident, admitting a patient to a nursing home. I handed her the inch-thick stack of papers that came from the hospital, and she immediately asked what we were supposed to do with it. When I explained that it was the hospital chart, she wondered aloud how she was supposed to navigate to the different sections in order to review the information. I was stupefied but understood the reason behind her question. The way we document has changed so dramatically over just the past decade. Unfortunately, without intention, the way that we chart has affected the way we relate to patients.

In 1923, the German philosopher Martin Buber published the book for which he is best known, “I and Thou.” In that book Buber says that there are two ways we can approach relationships: “I-Thou” or “I-It.” In I-It relationships, we view the other person as an “it” to be used to accomplish a purpose or to be experienced without his or her full involvement. In an I-Thou relationship, we appreciate the other person for all their complexity, in their full humanness. We acknowledge and approach the person as a unique individual who has dreams, goals, fears, and wishes that may be different than ours but to which we can still relate.

While the importance and benefits of the electronic record are clear, we must constantly remind ourselves that the EHR is a tool of care and not the goal of care. While the people we see have health needs that must be diagnosed, treated, and recorded, and their illnesses are an important part of their being, they do not define their being. Nor should they define our relationship with them. Patients agree; when surveyed about the attributes of a good physician, they regularly respond that they want their physicians to have a sense of them as people, not just patients.

Recently, I was reminded of the challenge of keeping this simple task in the forefront of care while on hospital service. I had occasion to sit and talk with one of my patients without a computer in the room. This was unusual for me, as I typically fill out the EHR as I am seeing the patient. As I listened to the individual in his gown, lying on his hospital bed and describing the symptoms that brought him to the hospital, I was reminded of the subtle pauses and nuances that occur during focused conversations, during deep listening.