User login

Should every scheduled cesarean birth use an Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) pathway?

Cesarean birth is one of the most common major surgical procedures performed in developed countries1 with over 1,170,000 cesarean births in the United States in 2021.2 Many surgeons and anesthesiologists believe that Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) pathways improve surgical outcomes.3,4 Important goals of ERAS include setting patient expectations for the surgical procedure, accelerating patient recovery to full function, and minimizing perioperative complications such as severe nausea, aspiration, surgical site infection, wound complications, and perioperative anemia. The ERAS Society in 20185-7 and the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) in 20218 proposed ERAS pathways for cesarean birth. Both societies recommended that obstetric units consider adopting an ERAS pathway compatible with local clinical resources. In addition, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has provided guidance for implementing ERAS pathways for gynecologic surgery.9 The consistent use of standardized protocols to improve surgical care in obstetrics should lead to a reduction in care variation and improve health equity outcomes.

The clinical interventions recommended for ERAS cesarean birth occur sequentially in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of care. The recommendations associated with each of these phases are reviewed below. It is important to note that each obstetric unit should use a multidisciplinary process to develop an ERAS pathway that best supports local practice given clinician preferences, patient characteristics, and resource availability.

Preoperative components of ERAS

Standardized patient education (SPE). SPE is an important component of ERAS, although evidence to support the recommendation is limited. At a minimum a written handout describing steps in the cesarean birth process, or a patient-education video should be part of patient education. The University of Michigan Medical Center has produced a 3-minute video for patients explaining ERAS cesarean birth.10 The University of Maryland Medical Center has produced a 2.5-minute video in English and Spanish, explaining ERAS cesarean birth for patients.11 Some surgeons place a telephone call to patients the evening before surgery to help orient the patient to ERAS cesarean birth.

Breastfeeding education. An important goal of obstetric care is to optimize the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at birth. Breastfeeding education, including a commitment to support the initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth, may enhance the rate of exclusive breastfeeding. There are numerous videos available for patients about breastfeeding after cesarean birth (as an example, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9iOGn85NdTg).

Limit fasting. In the past, surgical guidelines recommended fasting after midnight prior to surgery. The ERAS Society recommends that patients should be encouraged to drink clear fluids up to 2 hours before surgery and may have a light meal up to 6 hours before surgery (Part 1).

Carbohydrate loading. Surgery causes a metabolic stress that is increased by fasting. Carbohydrate loading prior to surgery reduces the magnitude of the catabolic state caused by the combination of surgery and fasting.12 SOAP and the ERAS Society recommend oral carbohydrate fluid supplementation 2 hours before surgery for nondiabetic patients. SOAP suggests 32 oz of Gatorade or 16 oz of clear apple juice as options for carbohydrate loading. For diabetic patients, the carbohydrate load can be omitted. In fasting pregnant patients at term, gastric emptying was near complete 2 hours after consumption of 400 mL of a carbohydrate drink.13 In one study, consumption of 400 mL of a carbohydrate drink 2 hours before cesarean resulted in a 7% increase in the newborn blood glucose level at 20 min after delivery.14

Minimize preoperative anemia. Approximately 50% of pregnant women are iron deficient and approximately 10% are anemic in the third trimester.15,16 Cesarean birth is associated with significant blood loss necessitating the need to optimize red blood cell mass before surgery. Measuring ferritin to identify patients with iron deficiency and aggressive iron replacement, including intravenous iron if necessary, will reduce the prevalence of anemia prior to cesarean birth.17 Another cause of anemia in pregnancy is vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency. Low vitamin B12 is especially common in pregnant patients who have previously had bariatric surgery. One study reported that, of 113 pregnant patients who were, on average, 3 years from a bariatric surgery procedure, 12% had vitamin B12 circulating levels < 130 pg/mL.18 Among pregnant patients who are anemic, and do not have a hemoglobinopathy, measuring ferritin, folic acid, and vitamin B12 will help identify the cause of anemia and guide treatment.19

Optimize preoperative physical condition. Improving healthy behaviors and reducing unhealthy behaviors preoperatively may enhance patient recovery to full function. In the weeks before scheduled cesarean birth, cessation of the use of tobacco products, optimizing activity and improving diet quality, including increasing protein intake, may best prepare patients for the metabolic stress of surgery.

Continue to: Intraoperative components of ERAS...

Intraoperative components of ERAS

Reduce the risk of surgical site infection (SSI) and wound complications. Bundles that include antibiotics, chlorhexidine (or an alternative antibacterial soap) and clippers have been shown to reduce SSI.20 Routine administration of preoperative antibiotics is a consensus recommendation and there is high adherence with this recommendation in the United States. Chlorhexidine-alcohol is the preferred solution for skin preparation. Vaginal preparation with povidine-iodine or chlorhexidine may be considered.6

Surgical technique. Blunt extension of a transverse hysterotomy may reduce blood loss. Closure of the hysterotomy incision in 2 layers is recommended to reduce uterine scar dehiscence in a subsequent pregnancy. If the patient has ≥2 cm of subcutaneous tissue, this layer should be approximated with sutures. Skin closure should be with subcuticular suture.6

Optimize uterotonic administration. Routine use of uterotonics reduces the risk of blood loss, transfusion, and postoperative anemia. There is high adherence with the use of uterotonic administration after birth in the United States.6,8

Ensure normothermia. Many patients become hypothermic during a cesarean birth. Active warming of the patient with an in-line IV fluid warmer and forced air warming over the patient’s body can reduce the risk of hypothermia.8

Initiate multimodal anesthesia. Anesthesiologists often use intrathecal or epidural morphine to enhance analgesia. Ketorolac administration prior to completion of the cesarean procedure and perioperative administration of acetaminophen may reduce postoperative pain.8 The use of preoperative antiemetics will reduce intraoperative and postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Initiate VTE prophylaxis. Pneumatic compression stockings are recommended. Anticoagulation should not be routinely used for VTE prophylaxis.6

Postoperative components of ERAS

Patient education to prepare for discharge home when ready. Patient education focused on home when ready is important in preparing the patient for discharge home.7 Completion of required newborn testing, lactation education, and contraception planning plus coordination of newborn pediatric follow-up is necessary before discharge.

Support early return of bowel function. Early return of bowel function is best supported by a multimodal approach including initiation of clear fluid intake immediately following surgery, encouraging consumption of a regular diet within 27 to 4 hours8 following surgery. Gum chewing for at least 5 minutes 3 times daily accelerates return of bowel function.8 In a meta-analysis of 10 randomized studies examining the effect of gum chewing after cesarean, the investigators reported that gum chewing shortened the time to passage of flatus and defecation.21

Early ambulation.

Sequentially advanced activity, starting with sitting on the edge of the bed, sitting in a chair, and ambulation within 8 hours of surgery, is recommended to facilitate faster recovery, reduce rates of complications, and enable transition to home.8

Early removal of the urinary catheter. It is recommended that the urinary catheter be removed within 12 hours after cesarean birth.8 Early removal of the urinary catheter increases patient mobility and reduces the length of hospitalization. Early removal of the urinary catheter may be associated with postoperative urinary retention and recatheterization in a small number of patients.

Prescribe routinely scheduled acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and ketorolac. A key component of ERAS cesarean birth is the standardized administration of nonopioid pain medicines, alternating doses of acetaminophen and an NSAID. ERAS cesarean birth is likely to result in a reduction in inpatient and postdischarge opioid use.22-24

VTE prophylaxis. Pneumatic compression stockings are recommended. Anticoagulation should not be routinely used for VTE prophylaxis.8

Auditing and reporting adherence with components of ERAS

In clinical practice there may be a gap between a clinician’s subjective perception of their performance and an independent audit of their clinical performance. ERAS pathways should be implemented with a commitment to performing audits and providing quantitative feedback to clinicians. Consistent use of measurement, feedback, and coaching can improve performance and reduce variation among individual clinicians. As an example, in one study of the use of a surgical safety checklist, 99% of the surgeons reported that they routinely used a surgical safety checklist, but the audit showed that the checklist was used in only 60% of cases.25 Gaps between self-reported performance and audited performance are common in clinical practice. Audits with feedback are critical to improving adherence with the components of an ERAS pathway.

Three independent systematic reviews and meta-analyses report that ERAS pathways reduce hospital length of stay without increasing the readmission rate.26-28 One meta-analysis reported that ERAS may also reduce time to first mobilization and result in earlier removal of the urinary catheter.26 ERAS pathways also may reduce postoperative complications, lower pain scores, and decrease opioid use.27 The general consensus among quality and safety experts is that reducing variation through standardization of pathways is generally associated with improved quality and enhanced safety. ERAS pathways have been widely accepted in multiple surgical fields. ERAS pathways should become the standard for performing cesarean procedures.●

1. Molina G, Weiser RG, Lipsitz SR, et al. Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA. 2015;314:2263-2270.

2. Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Births: provisional data for 2021. Vital Statistics Release; No. 20. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. May 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr020.pdf.

3. Berian JR, Ban KA, Liu JB, et al. Adherence to enhanced recovery protocols in NSQIP and association with colectomy outcomes. Ann Surg. 2019;486-493.

4. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:292-298.

5. Wilson RD, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for antenatal and preoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 1). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:523.e1-523.e15.

6. Caughey AB, Wood SL, Macones GA, et al Guidelines for intraoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 2). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:533-544.

7. Macones GA, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for postoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 3). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:247.e1-247.e9.

8. Bollag L, Lim G, Sultan P, et al. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology: Consensus statement and recommendations for enhanced recovery after cesarean. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:1362-1377.

9. Perioperative pathways: enhanced recovery after surgery. ACOG Committee Opinion No 750. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e120-130.

10. University of Michigan. ERAS: A patient education video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CoFtgdluBc0. Accessed October 24, 2022.

11. University of Maryland. ERAS. https://www.umms.org/ummc/health-services/womens-health/ostetrics-gynecology/pregnancy-childbirth/labor-delivery/enhanced-recovery-after-cesarean. Accessed October 24, 2022.

12. Bilku DK, Dennison AR, Hall TC, et al. Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:15-22.

13. Popivanov P, Irwin R, Walsh M, et al. Gastric emptying of carbohydrate drinks in term parturients before elective caesarean surgery: an observational study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2020;41:29-34.

14. He Y, Liu C, Han Y, et al. The impact of carbohydrate-rich supplement taken two hours before caesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal perioperative outcomes- a randomized clinical trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:682.

15. Auerbach M, Abernathy J, Juul S, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency in first trimester, nonanemic pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34:1002-1005.

16. Mei Z, Cogswell ME, Looker AC, et al. Assessment of iron status in US pregnant women from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1996-2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1312-1320.

17. Nour N, Barbieri RL. Optimize detection and treatment of iron deficiency in pregnancy. OBG Manag. 2022;34:9-11.

18. Mead NC, Sakkatos P, Sakellaropoulos GC, et al. Pregnancy outcomes and nutritional indices after 3 types of bariatric surgery performed at a single institution. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:1166-1173.

19. Achebe MM, Gafter-Gvili A. How I treat anemia in pregnancy: iron, cobalamin and folate. Blood. 2017;129:940-949.

20. Carter EB, Temming LA, Fowler S, et al. Evidence-based bundles and cesarean delivery surgical site infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:735-746.

21. Wen Z, Shen M, Wu C, et al. Chewing gum for intestinal function recovery after caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:105.

22. McCoy JA, Gutman S, Hamm RF, et al. The association between implementation of an enhanced recovery after cesarean pathway with standardized discharge prescriptions and opioid use and pain experience after cesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38:1341-1347.

23. Mullman L, Hilden P, Goral J, et al. Improved outcomes with an enhanced recovery approach to cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:685-691.

24. Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

25. Sendlhofer G, Lumenta DB, Leitgeb K, et al. The gap between individual perception and compliance: a quantitative follow-up study of the surgical safety checklist application. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149212.

26. Sultan P, Sharawi N, Blake L, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after cesarean delivery on maternal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40:100935.

27. Meng X, Chen K, Yang C, et al. The clinical efficacy and safety of enhanced recovery after surgery for cesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Front Med. 2021;8:694385.

28. Corson E, Hind D, Beever D, et al. Enhanced recovery after elective caesarean: a rapid review of clinical protocols and an umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:91.

Cesarean birth is one of the most common major surgical procedures performed in developed countries1 with over 1,170,000 cesarean births in the United States in 2021.2 Many surgeons and anesthesiologists believe that Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) pathways improve surgical outcomes.3,4 Important goals of ERAS include setting patient expectations for the surgical procedure, accelerating patient recovery to full function, and minimizing perioperative complications such as severe nausea, aspiration, surgical site infection, wound complications, and perioperative anemia. The ERAS Society in 20185-7 and the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) in 20218 proposed ERAS pathways for cesarean birth. Both societies recommended that obstetric units consider adopting an ERAS pathway compatible with local clinical resources. In addition, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has provided guidance for implementing ERAS pathways for gynecologic surgery.9 The consistent use of standardized protocols to improve surgical care in obstetrics should lead to a reduction in care variation and improve health equity outcomes.

The clinical interventions recommended for ERAS cesarean birth occur sequentially in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of care. The recommendations associated with each of these phases are reviewed below. It is important to note that each obstetric unit should use a multidisciplinary process to develop an ERAS pathway that best supports local practice given clinician preferences, patient characteristics, and resource availability.

Preoperative components of ERAS

Standardized patient education (SPE). SPE is an important component of ERAS, although evidence to support the recommendation is limited. At a minimum a written handout describing steps in the cesarean birth process, or a patient-education video should be part of patient education. The University of Michigan Medical Center has produced a 3-minute video for patients explaining ERAS cesarean birth.10 The University of Maryland Medical Center has produced a 2.5-minute video in English and Spanish, explaining ERAS cesarean birth for patients.11 Some surgeons place a telephone call to patients the evening before surgery to help orient the patient to ERAS cesarean birth.

Breastfeeding education. An important goal of obstetric care is to optimize the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at birth. Breastfeeding education, including a commitment to support the initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth, may enhance the rate of exclusive breastfeeding. There are numerous videos available for patients about breastfeeding after cesarean birth (as an example, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9iOGn85NdTg).

Limit fasting. In the past, surgical guidelines recommended fasting after midnight prior to surgery. The ERAS Society recommends that patients should be encouraged to drink clear fluids up to 2 hours before surgery and may have a light meal up to 6 hours before surgery (Part 1).

Carbohydrate loading. Surgery causes a metabolic stress that is increased by fasting. Carbohydrate loading prior to surgery reduces the magnitude of the catabolic state caused by the combination of surgery and fasting.12 SOAP and the ERAS Society recommend oral carbohydrate fluid supplementation 2 hours before surgery for nondiabetic patients. SOAP suggests 32 oz of Gatorade or 16 oz of clear apple juice as options for carbohydrate loading. For diabetic patients, the carbohydrate load can be omitted. In fasting pregnant patients at term, gastric emptying was near complete 2 hours after consumption of 400 mL of a carbohydrate drink.13 In one study, consumption of 400 mL of a carbohydrate drink 2 hours before cesarean resulted in a 7% increase in the newborn blood glucose level at 20 min after delivery.14

Minimize preoperative anemia. Approximately 50% of pregnant women are iron deficient and approximately 10% are anemic in the third trimester.15,16 Cesarean birth is associated with significant blood loss necessitating the need to optimize red blood cell mass before surgery. Measuring ferritin to identify patients with iron deficiency and aggressive iron replacement, including intravenous iron if necessary, will reduce the prevalence of anemia prior to cesarean birth.17 Another cause of anemia in pregnancy is vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency. Low vitamin B12 is especially common in pregnant patients who have previously had bariatric surgery. One study reported that, of 113 pregnant patients who were, on average, 3 years from a bariatric surgery procedure, 12% had vitamin B12 circulating levels < 130 pg/mL.18 Among pregnant patients who are anemic, and do not have a hemoglobinopathy, measuring ferritin, folic acid, and vitamin B12 will help identify the cause of anemia and guide treatment.19

Optimize preoperative physical condition. Improving healthy behaviors and reducing unhealthy behaviors preoperatively may enhance patient recovery to full function. In the weeks before scheduled cesarean birth, cessation of the use of tobacco products, optimizing activity and improving diet quality, including increasing protein intake, may best prepare patients for the metabolic stress of surgery.

Continue to: Intraoperative components of ERAS...

Intraoperative components of ERAS

Reduce the risk of surgical site infection (SSI) and wound complications. Bundles that include antibiotics, chlorhexidine (or an alternative antibacterial soap) and clippers have been shown to reduce SSI.20 Routine administration of preoperative antibiotics is a consensus recommendation and there is high adherence with this recommendation in the United States. Chlorhexidine-alcohol is the preferred solution for skin preparation. Vaginal preparation with povidine-iodine or chlorhexidine may be considered.6

Surgical technique. Blunt extension of a transverse hysterotomy may reduce blood loss. Closure of the hysterotomy incision in 2 layers is recommended to reduce uterine scar dehiscence in a subsequent pregnancy. If the patient has ≥2 cm of subcutaneous tissue, this layer should be approximated with sutures. Skin closure should be with subcuticular suture.6

Optimize uterotonic administration. Routine use of uterotonics reduces the risk of blood loss, transfusion, and postoperative anemia. There is high adherence with the use of uterotonic administration after birth in the United States.6,8

Ensure normothermia. Many patients become hypothermic during a cesarean birth. Active warming of the patient with an in-line IV fluid warmer and forced air warming over the patient’s body can reduce the risk of hypothermia.8

Initiate multimodal anesthesia. Anesthesiologists often use intrathecal or epidural morphine to enhance analgesia. Ketorolac administration prior to completion of the cesarean procedure and perioperative administration of acetaminophen may reduce postoperative pain.8 The use of preoperative antiemetics will reduce intraoperative and postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Initiate VTE prophylaxis. Pneumatic compression stockings are recommended. Anticoagulation should not be routinely used for VTE prophylaxis.6

Postoperative components of ERAS

Patient education to prepare for discharge home when ready. Patient education focused on home when ready is important in preparing the patient for discharge home.7 Completion of required newborn testing, lactation education, and contraception planning plus coordination of newborn pediatric follow-up is necessary before discharge.

Support early return of bowel function. Early return of bowel function is best supported by a multimodal approach including initiation of clear fluid intake immediately following surgery, encouraging consumption of a regular diet within 27 to 4 hours8 following surgery. Gum chewing for at least 5 minutes 3 times daily accelerates return of bowel function.8 In a meta-analysis of 10 randomized studies examining the effect of gum chewing after cesarean, the investigators reported that gum chewing shortened the time to passage of flatus and defecation.21

Early ambulation.

Sequentially advanced activity, starting with sitting on the edge of the bed, sitting in a chair, and ambulation within 8 hours of surgery, is recommended to facilitate faster recovery, reduce rates of complications, and enable transition to home.8

Early removal of the urinary catheter. It is recommended that the urinary catheter be removed within 12 hours after cesarean birth.8 Early removal of the urinary catheter increases patient mobility and reduces the length of hospitalization. Early removal of the urinary catheter may be associated with postoperative urinary retention and recatheterization in a small number of patients.

Prescribe routinely scheduled acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and ketorolac. A key component of ERAS cesarean birth is the standardized administration of nonopioid pain medicines, alternating doses of acetaminophen and an NSAID. ERAS cesarean birth is likely to result in a reduction in inpatient and postdischarge opioid use.22-24

VTE prophylaxis. Pneumatic compression stockings are recommended. Anticoagulation should not be routinely used for VTE prophylaxis.8

Auditing and reporting adherence with components of ERAS

In clinical practice there may be a gap between a clinician’s subjective perception of their performance and an independent audit of their clinical performance. ERAS pathways should be implemented with a commitment to performing audits and providing quantitative feedback to clinicians. Consistent use of measurement, feedback, and coaching can improve performance and reduce variation among individual clinicians. As an example, in one study of the use of a surgical safety checklist, 99% of the surgeons reported that they routinely used a surgical safety checklist, but the audit showed that the checklist was used in only 60% of cases.25 Gaps between self-reported performance and audited performance are common in clinical practice. Audits with feedback are critical to improving adherence with the components of an ERAS pathway.

Three independent systematic reviews and meta-analyses report that ERAS pathways reduce hospital length of stay without increasing the readmission rate.26-28 One meta-analysis reported that ERAS may also reduce time to first mobilization and result in earlier removal of the urinary catheter.26 ERAS pathways also may reduce postoperative complications, lower pain scores, and decrease opioid use.27 The general consensus among quality and safety experts is that reducing variation through standardization of pathways is generally associated with improved quality and enhanced safety. ERAS pathways have been widely accepted in multiple surgical fields. ERAS pathways should become the standard for performing cesarean procedures.●

Cesarean birth is one of the most common major surgical procedures performed in developed countries1 with over 1,170,000 cesarean births in the United States in 2021.2 Many surgeons and anesthesiologists believe that Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) pathways improve surgical outcomes.3,4 Important goals of ERAS include setting patient expectations for the surgical procedure, accelerating patient recovery to full function, and minimizing perioperative complications such as severe nausea, aspiration, surgical site infection, wound complications, and perioperative anemia. The ERAS Society in 20185-7 and the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) in 20218 proposed ERAS pathways for cesarean birth. Both societies recommended that obstetric units consider adopting an ERAS pathway compatible with local clinical resources. In addition, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has provided guidance for implementing ERAS pathways for gynecologic surgery.9 The consistent use of standardized protocols to improve surgical care in obstetrics should lead to a reduction in care variation and improve health equity outcomes.

The clinical interventions recommended for ERAS cesarean birth occur sequentially in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of care. The recommendations associated with each of these phases are reviewed below. It is important to note that each obstetric unit should use a multidisciplinary process to develop an ERAS pathway that best supports local practice given clinician preferences, patient characteristics, and resource availability.

Preoperative components of ERAS

Standardized patient education (SPE). SPE is an important component of ERAS, although evidence to support the recommendation is limited. At a minimum a written handout describing steps in the cesarean birth process, or a patient-education video should be part of patient education. The University of Michigan Medical Center has produced a 3-minute video for patients explaining ERAS cesarean birth.10 The University of Maryland Medical Center has produced a 2.5-minute video in English and Spanish, explaining ERAS cesarean birth for patients.11 Some surgeons place a telephone call to patients the evening before surgery to help orient the patient to ERAS cesarean birth.

Breastfeeding education. An important goal of obstetric care is to optimize the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at birth. Breastfeeding education, including a commitment to support the initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth, may enhance the rate of exclusive breastfeeding. There are numerous videos available for patients about breastfeeding after cesarean birth (as an example, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9iOGn85NdTg).

Limit fasting. In the past, surgical guidelines recommended fasting after midnight prior to surgery. The ERAS Society recommends that patients should be encouraged to drink clear fluids up to 2 hours before surgery and may have a light meal up to 6 hours before surgery (Part 1).

Carbohydrate loading. Surgery causes a metabolic stress that is increased by fasting. Carbohydrate loading prior to surgery reduces the magnitude of the catabolic state caused by the combination of surgery and fasting.12 SOAP and the ERAS Society recommend oral carbohydrate fluid supplementation 2 hours before surgery for nondiabetic patients. SOAP suggests 32 oz of Gatorade or 16 oz of clear apple juice as options for carbohydrate loading. For diabetic patients, the carbohydrate load can be omitted. In fasting pregnant patients at term, gastric emptying was near complete 2 hours after consumption of 400 mL of a carbohydrate drink.13 In one study, consumption of 400 mL of a carbohydrate drink 2 hours before cesarean resulted in a 7% increase in the newborn blood glucose level at 20 min after delivery.14

Minimize preoperative anemia. Approximately 50% of pregnant women are iron deficient and approximately 10% are anemic in the third trimester.15,16 Cesarean birth is associated with significant blood loss necessitating the need to optimize red blood cell mass before surgery. Measuring ferritin to identify patients with iron deficiency and aggressive iron replacement, including intravenous iron if necessary, will reduce the prevalence of anemia prior to cesarean birth.17 Another cause of anemia in pregnancy is vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency. Low vitamin B12 is especially common in pregnant patients who have previously had bariatric surgery. One study reported that, of 113 pregnant patients who were, on average, 3 years from a bariatric surgery procedure, 12% had vitamin B12 circulating levels < 130 pg/mL.18 Among pregnant patients who are anemic, and do not have a hemoglobinopathy, measuring ferritin, folic acid, and vitamin B12 will help identify the cause of anemia and guide treatment.19

Optimize preoperative physical condition. Improving healthy behaviors and reducing unhealthy behaviors preoperatively may enhance patient recovery to full function. In the weeks before scheduled cesarean birth, cessation of the use of tobacco products, optimizing activity and improving diet quality, including increasing protein intake, may best prepare patients for the metabolic stress of surgery.

Continue to: Intraoperative components of ERAS...

Intraoperative components of ERAS

Reduce the risk of surgical site infection (SSI) and wound complications. Bundles that include antibiotics, chlorhexidine (or an alternative antibacterial soap) and clippers have been shown to reduce SSI.20 Routine administration of preoperative antibiotics is a consensus recommendation and there is high adherence with this recommendation in the United States. Chlorhexidine-alcohol is the preferred solution for skin preparation. Vaginal preparation with povidine-iodine or chlorhexidine may be considered.6

Surgical technique. Blunt extension of a transverse hysterotomy may reduce blood loss. Closure of the hysterotomy incision in 2 layers is recommended to reduce uterine scar dehiscence in a subsequent pregnancy. If the patient has ≥2 cm of subcutaneous tissue, this layer should be approximated with sutures. Skin closure should be with subcuticular suture.6

Optimize uterotonic administration. Routine use of uterotonics reduces the risk of blood loss, transfusion, and postoperative anemia. There is high adherence with the use of uterotonic administration after birth in the United States.6,8

Ensure normothermia. Many patients become hypothermic during a cesarean birth. Active warming of the patient with an in-line IV fluid warmer and forced air warming over the patient’s body can reduce the risk of hypothermia.8

Initiate multimodal anesthesia. Anesthesiologists often use intrathecal or epidural morphine to enhance analgesia. Ketorolac administration prior to completion of the cesarean procedure and perioperative administration of acetaminophen may reduce postoperative pain.8 The use of preoperative antiemetics will reduce intraoperative and postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Initiate VTE prophylaxis. Pneumatic compression stockings are recommended. Anticoagulation should not be routinely used for VTE prophylaxis.6

Postoperative components of ERAS

Patient education to prepare for discharge home when ready. Patient education focused on home when ready is important in preparing the patient for discharge home.7 Completion of required newborn testing, lactation education, and contraception planning plus coordination of newborn pediatric follow-up is necessary before discharge.

Support early return of bowel function. Early return of bowel function is best supported by a multimodal approach including initiation of clear fluid intake immediately following surgery, encouraging consumption of a regular diet within 27 to 4 hours8 following surgery. Gum chewing for at least 5 minutes 3 times daily accelerates return of bowel function.8 In a meta-analysis of 10 randomized studies examining the effect of gum chewing after cesarean, the investigators reported that gum chewing shortened the time to passage of flatus and defecation.21

Early ambulation.

Sequentially advanced activity, starting with sitting on the edge of the bed, sitting in a chair, and ambulation within 8 hours of surgery, is recommended to facilitate faster recovery, reduce rates of complications, and enable transition to home.8

Early removal of the urinary catheter. It is recommended that the urinary catheter be removed within 12 hours after cesarean birth.8 Early removal of the urinary catheter increases patient mobility and reduces the length of hospitalization. Early removal of the urinary catheter may be associated with postoperative urinary retention and recatheterization in a small number of patients.

Prescribe routinely scheduled acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and ketorolac. A key component of ERAS cesarean birth is the standardized administration of nonopioid pain medicines, alternating doses of acetaminophen and an NSAID. ERAS cesarean birth is likely to result in a reduction in inpatient and postdischarge opioid use.22-24

VTE prophylaxis. Pneumatic compression stockings are recommended. Anticoagulation should not be routinely used for VTE prophylaxis.8

Auditing and reporting adherence with components of ERAS

In clinical practice there may be a gap between a clinician’s subjective perception of their performance and an independent audit of their clinical performance. ERAS pathways should be implemented with a commitment to performing audits and providing quantitative feedback to clinicians. Consistent use of measurement, feedback, and coaching can improve performance and reduce variation among individual clinicians. As an example, in one study of the use of a surgical safety checklist, 99% of the surgeons reported that they routinely used a surgical safety checklist, but the audit showed that the checklist was used in only 60% of cases.25 Gaps between self-reported performance and audited performance are common in clinical practice. Audits with feedback are critical to improving adherence with the components of an ERAS pathway.

Three independent systematic reviews and meta-analyses report that ERAS pathways reduce hospital length of stay without increasing the readmission rate.26-28 One meta-analysis reported that ERAS may also reduce time to first mobilization and result in earlier removal of the urinary catheter.26 ERAS pathways also may reduce postoperative complications, lower pain scores, and decrease opioid use.27 The general consensus among quality and safety experts is that reducing variation through standardization of pathways is generally associated with improved quality and enhanced safety. ERAS pathways have been widely accepted in multiple surgical fields. ERAS pathways should become the standard for performing cesarean procedures.●

1. Molina G, Weiser RG, Lipsitz SR, et al. Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA. 2015;314:2263-2270.

2. Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Births: provisional data for 2021. Vital Statistics Release; No. 20. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. May 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr020.pdf.

3. Berian JR, Ban KA, Liu JB, et al. Adherence to enhanced recovery protocols in NSQIP and association with colectomy outcomes. Ann Surg. 2019;486-493.

4. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:292-298.

5. Wilson RD, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for antenatal and preoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 1). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:523.e1-523.e15.

6. Caughey AB, Wood SL, Macones GA, et al Guidelines for intraoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 2). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:533-544.

7. Macones GA, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for postoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 3). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:247.e1-247.e9.

8. Bollag L, Lim G, Sultan P, et al. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology: Consensus statement and recommendations for enhanced recovery after cesarean. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:1362-1377.

9. Perioperative pathways: enhanced recovery after surgery. ACOG Committee Opinion No 750. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e120-130.

10. University of Michigan. ERAS: A patient education video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CoFtgdluBc0. Accessed October 24, 2022.

11. University of Maryland. ERAS. https://www.umms.org/ummc/health-services/womens-health/ostetrics-gynecology/pregnancy-childbirth/labor-delivery/enhanced-recovery-after-cesarean. Accessed October 24, 2022.

12. Bilku DK, Dennison AR, Hall TC, et al. Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:15-22.

13. Popivanov P, Irwin R, Walsh M, et al. Gastric emptying of carbohydrate drinks in term parturients before elective caesarean surgery: an observational study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2020;41:29-34.

14. He Y, Liu C, Han Y, et al. The impact of carbohydrate-rich supplement taken two hours before caesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal perioperative outcomes- a randomized clinical trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:682.

15. Auerbach M, Abernathy J, Juul S, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency in first trimester, nonanemic pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34:1002-1005.

16. Mei Z, Cogswell ME, Looker AC, et al. Assessment of iron status in US pregnant women from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1996-2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1312-1320.

17. Nour N, Barbieri RL. Optimize detection and treatment of iron deficiency in pregnancy. OBG Manag. 2022;34:9-11.

18. Mead NC, Sakkatos P, Sakellaropoulos GC, et al. Pregnancy outcomes and nutritional indices after 3 types of bariatric surgery performed at a single institution. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:1166-1173.

19. Achebe MM, Gafter-Gvili A. How I treat anemia in pregnancy: iron, cobalamin and folate. Blood. 2017;129:940-949.

20. Carter EB, Temming LA, Fowler S, et al. Evidence-based bundles and cesarean delivery surgical site infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:735-746.

21. Wen Z, Shen M, Wu C, et al. Chewing gum for intestinal function recovery after caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:105.

22. McCoy JA, Gutman S, Hamm RF, et al. The association between implementation of an enhanced recovery after cesarean pathway with standardized discharge prescriptions and opioid use and pain experience after cesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38:1341-1347.

23. Mullman L, Hilden P, Goral J, et al. Improved outcomes with an enhanced recovery approach to cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:685-691.

24. Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

25. Sendlhofer G, Lumenta DB, Leitgeb K, et al. The gap between individual perception and compliance: a quantitative follow-up study of the surgical safety checklist application. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149212.

26. Sultan P, Sharawi N, Blake L, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after cesarean delivery on maternal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40:100935.

27. Meng X, Chen K, Yang C, et al. The clinical efficacy and safety of enhanced recovery after surgery for cesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Front Med. 2021;8:694385.

28. Corson E, Hind D, Beever D, et al. Enhanced recovery after elective caesarean: a rapid review of clinical protocols and an umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:91.

1. Molina G, Weiser RG, Lipsitz SR, et al. Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA. 2015;314:2263-2270.

2. Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Births: provisional data for 2021. Vital Statistics Release; No. 20. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. May 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr020.pdf.

3. Berian JR, Ban KA, Liu JB, et al. Adherence to enhanced recovery protocols in NSQIP and association with colectomy outcomes. Ann Surg. 2019;486-493.

4. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:292-298.

5. Wilson RD, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for antenatal and preoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 1). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:523.e1-523.e15.

6. Caughey AB, Wood SL, Macones GA, et al Guidelines for intraoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 2). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:533-544.

7. Macones GA, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for postoperative care in cesarean delivery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Society recommendations (Part 3). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:247.e1-247.e9.

8. Bollag L, Lim G, Sultan P, et al. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology: Consensus statement and recommendations for enhanced recovery after cesarean. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:1362-1377.

9. Perioperative pathways: enhanced recovery after surgery. ACOG Committee Opinion No 750. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e120-130.

10. University of Michigan. ERAS: A patient education video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CoFtgdluBc0. Accessed October 24, 2022.

11. University of Maryland. ERAS. https://www.umms.org/ummc/health-services/womens-health/ostetrics-gynecology/pregnancy-childbirth/labor-delivery/enhanced-recovery-after-cesarean. Accessed October 24, 2022.

12. Bilku DK, Dennison AR, Hall TC, et al. Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:15-22.

13. Popivanov P, Irwin R, Walsh M, et al. Gastric emptying of carbohydrate drinks in term parturients before elective caesarean surgery: an observational study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2020;41:29-34.

14. He Y, Liu C, Han Y, et al. The impact of carbohydrate-rich supplement taken two hours before caesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal perioperative outcomes- a randomized clinical trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:682.

15. Auerbach M, Abernathy J, Juul S, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency in first trimester, nonanemic pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34:1002-1005.

16. Mei Z, Cogswell ME, Looker AC, et al. Assessment of iron status in US pregnant women from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1996-2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1312-1320.

17. Nour N, Barbieri RL. Optimize detection and treatment of iron deficiency in pregnancy. OBG Manag. 2022;34:9-11.

18. Mead NC, Sakkatos P, Sakellaropoulos GC, et al. Pregnancy outcomes and nutritional indices after 3 types of bariatric surgery performed at a single institution. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:1166-1173.

19. Achebe MM, Gafter-Gvili A. How I treat anemia in pregnancy: iron, cobalamin and folate. Blood. 2017;129:940-949.

20. Carter EB, Temming LA, Fowler S, et al. Evidence-based bundles and cesarean delivery surgical site infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:735-746.

21. Wen Z, Shen M, Wu C, et al. Chewing gum for intestinal function recovery after caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:105.

22. McCoy JA, Gutman S, Hamm RF, et al. The association between implementation of an enhanced recovery after cesarean pathway with standardized discharge prescriptions and opioid use and pain experience after cesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38:1341-1347.

23. Mullman L, Hilden P, Goral J, et al. Improved outcomes with an enhanced recovery approach to cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:685-691.

24. Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

25. Sendlhofer G, Lumenta DB, Leitgeb K, et al. The gap between individual perception and compliance: a quantitative follow-up study of the surgical safety checklist application. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149212.

26. Sultan P, Sharawi N, Blake L, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after cesarean delivery on maternal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40:100935.

27. Meng X, Chen K, Yang C, et al. The clinical efficacy and safety of enhanced recovery after surgery for cesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Front Med. 2021;8:694385.

28. Corson E, Hind D, Beever D, et al. Enhanced recovery after elective caesarean: a rapid review of clinical protocols and an umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:91.

“Blind” endometrial sampling: A call to end the practice

Linda Bradley, MD: The standard in ObGyn for many years has been our reliance on the blind dilation and curettage (D&C)—it has been the mainstay for evaluation of the endometrial cavity. We know that it has risks, but most importantly, the procedure has low sensitivity for detecting focal pathology. This basic lack of confirmation of lesions makes a diagnosis impossible and patients are challenged in getting adequate treatment, and will not, since they may not know what options they have for the treatment of intrauterine pathology.

Because it is a “blind procedure,” done without looking, we don’t know the endpoints, such as when is the procedure completed, how do we know we removed all of the lesions? Let’s look at our colleagues, like GI and colorectal physicians. If a patient presents with rectal bleeding, we would perform an exam, followed by either a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. If a patient were vomiting up blood, a gastroenterologist would perform an upper endoscopy, look with a tube to see if there is an ulcer or something else as a source of the bleeding. If a patient were bleeding from the bladder, a urologist would use a cystoscope for direct inspection.

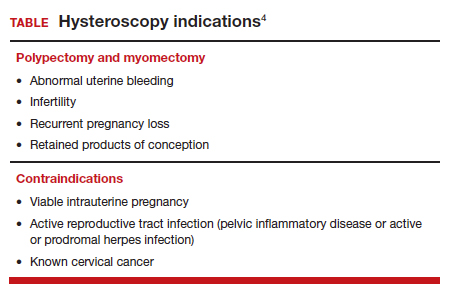

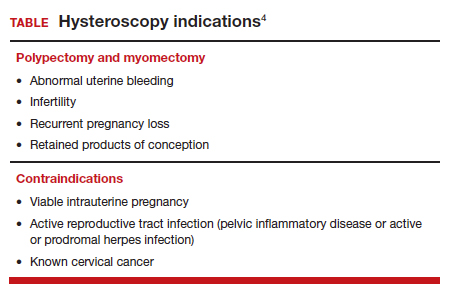

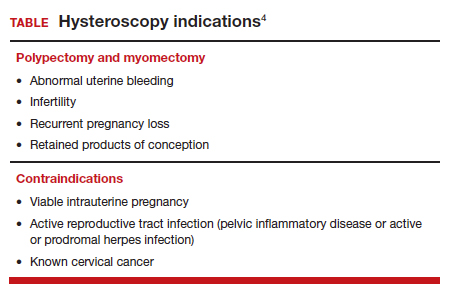

Unfortunately for gynecologists, only about 15% to 25% of us will use hysteroscopy as a diagnostic method2—a method that has excellent sensitivity in detecting endocervical disease, intrauterine disease, and proximal tubal pathology. Compared with blind curettage, we can visualize the cavity; we can sample the cavity directly; we can determine what the patient has and determine the proper surgical procedure, medical therapy, or reassurance that a patient may be offered. We often are looking at focal lesions, lesions in the uterine cavity that could be cancer, so we can make a diagnosis. Or we may be looking at small things, like endometrial hyperplasia, endocervical or endometrial polyps, retained products of conception, or fibroids. We can look at uterine pathology as well as anatomic issues and malformations—such as bicornuate or septate uterus.

I actually say, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope” because it allows us to evaluate for many things. The beauty of the new office hysteroscopes is that they are miniaturized. Doctors now have the ability to use reusable devices that are as small as 3 millimeters. There are disposable ones that are up to 3.5 to 4 millimeters in size. Gynecologists have the options to choose from reusuable rigid or flexible hysteroscopes or completely disposable devices. So, truly, we now should not have an excuse for evaluating a woman’s anatomy, especially for bleeding. We should no longer rely, as we have for the last century or more, just on blind sampling, because we miss focal lesions.

OBG Management: When was the hysteroscope first introduced into the field?

Dr. Bradley: The technology employed in hysteroscopy has been around really since the last 150+ years, introduced by Dr. Pantaleoni. We just have not embraced its usefulness in our clinical practice for many years. Today, about 15% to 25% of gynecologists practicing in the United States are performing hysteroscopy in the office.1

OBG Management: How does using hysteroscopy contribute to better patient outcomes?

Dr. Bradley: We can get a more accurate diagnosis—fewer false-negatives and a high degree of sensitivity in detecting focal lesions. With D&C, much focal pathology can be left behind. In a 2001 study, 105 symptomatic postmenopausal women with bleeding and thickened lining of the uterus greater than 5 mm on ultrasound underwent blind D&C. They found that 80% of the women had intracavitary lesions and 90% had focal lesions. In fact, 87% of the patients with focal lesions still had residual pathology after the blind D&C.3 The D&C procedure missed 58% of polyps, 50% of endometrial hyperplasia, 60% of cases of complex atypical hyperplasia, and even 11% of endometrial cancers. So these numbers are just not very good. Direct inspection of the uterus, with uninterrupted visualization through hysteroscopy, with removal of lesions under direct visualization, should be our goal.

Blind sampling also poses greater risk for things like perforation. In addition, you not only can miss lesions by just scraping the endometrium, D&C also can leave lesions just floating around in the uterine cavity, with those lesions never retrieved. With office hysteroscopy, the physician can be more successful in treating a condition because once you see what is going on in the uterine cavity, you can say, “Okay, I can fix this with a surgical procedure. What instruments do I need? How much time is it going to take? Is this a straightforward case? Is it more complicated? Do I let an intern do the case? Is this for a more senior resident or fellow?” So I think it helps to direct the next steps for surgical management and even medical management, which also could be what we call “one-stop shopping.” For instance, for directed biopsies for removal of small polyps, for patients that can tolerate the procedure a little longer, the diagnostic hysteroscopy then becomes a management, an operative procedure, that really, for myself, can be done in the office. Removal of larger fibroids, because of fluid management and other concerns, would not be done in the office. Most patients tolerate office procedures, but it also depends on a patient’s weight, and her ability to relax during the procedure.

The ultimate goal for hysteroscopy is a minimum of diagnosis, meaning in less than 2, 3 minutes, you can look inside the uterus. Our devices are 3 millimeters in size; I tell my patients, it’s the size of “a piece of spaghetti or pasta,” and we will just take a look. If we see a polyp, okay, if your office is not equipped, because then you need a different type of equipment for removal, then take her to the operating room. The patient would be under brief anesthesia and go home an hour or 2 later. So really, for physicians, we just need to embrace the technology to make a diagnosis, just look, and then from there decide what is next.

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?...

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: I think first is always be patient-centric. Let patients be prepared for the procedure. We have reading materials; our nurses explain the procedure. In the office, I try to prepare the patient for success. I let her know what is going on. A friend, family member can be with her. We have a nurse that understands the procedure; she explains it well. We have a type of bed that allows the patients’ legs to rest more comfortably in the stirrups—a leg rest kind of stirrup. We use a heating pad. Some patients like to hear music. Some patients like to have aromatherapy. We are quick and efficient, and typically just talk to the patient throughout the procedure. Although some patients don’t like this explanatory, “talkative” approach—they say, “Dr. Bradley, just do the procedure. I don’t want to know you are touching the cervix. I don’t want to know that you’re prepping. Just do it.”

But I like what we called it when I was growing up: vocal-local (talk to your patient and explain as you proceed). It’s like local anesthesia. For these procedures in the office you usually do not have to use numbing medicine or a paracervical block. Look at the patient’s age, number of years in menopause, whether or not she has delivered vaginally, and what her cervix looks like. Does she have a sexually transmitted infection or pelvic inflammatory disease? Sometimes we will use misoprostol, my personal preference is oral, but there are data to suggest that vaginal can be of help.4 We suggest Motrin, Tylenol an hour or 2 before, and we always want patients to not come in on an empty stomach. There is also the option of primrose oil, a supplement, that patients buy at the drug store in the vitamin section. It’s used for cervical softening. It is taken orally.5-7

If they want, patients can watch a video—similar to watching childbirth videos when I used to deliver babies. At some point we started putting mirrors where women could see their efforts of pushing a baby out, as it might give them more willpower to push harder. Some people don’t want to look. But the majority of women will do well in this setting. I do have a small number of women that just say, “I can’t do this in the office,” and so in those cases, they can go to the operating room. But the main idea is, even in an operating room, you are not just doing a D&C. You are still going to look inside with a hysteroscope and have a great panoramic view of what is going on, and remove a lesion with an instrument while you watch. Not a process of looking with the hysteroscope, scraping with a curettage, and thinking that you are complete. Targeted removal of focal lesions under continuous visualization is the goal.

OBG Management: Can you describe the goals of the consensus document on ending blind sampling co-created by the European Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy, AAGL, and the Global Community on Hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: Our goal for this year is to get a systematic review and guidelines paper written that speaks to what we have just talked about. We want to have as many articles about why blind sampling is not beneficial, with too many misses, and now we have new technology available. We want to speak to physicians to solve the conundrum of bleeding, with equivocal ultrasounds, equivocal saline infusion, sonograms, equivocal MRIs—be able to take a look. Let’s come up to speed like our other colleagues in other specialties that “look.” A systematic review guideline document will provide the evidence that blind D&C is fraught with problems and how often we miss disease and its inherent risk.

We need to, by itself, for most of our patients, abandon D&C because we have too many missed diagnoses. As doctors we have to be lifelong learners. There was no robot back in the day. We were not able to do laparoscopic hysterectomies, there were no MRIs. I remember in our city, there was one CT scan. We just did not have a lot of technology. The half-life of medical knowledge used to be decades—you graduated in the ‘60s, you could be a great gynecologist for the next 30 years because there was not that much going on. When I finished in the mid to late ‘80s, there was no hysteroscopy training. But I have come to see its value, the science behind it.

So what I say to doctors is, “We learn so many new things, we shouldn’t get stuck in just saying, ‘I didn’t do this when I was in training.’” And if your thought is, “Oh, in my practice, I don’t have that many cases,” you still need to be able to know who in your community can be a resource to your patients. As Maya Angelou says, “When you know better, you should do better.” And that’s where I am now—to be a lifelong learner, and just do it.

Lastly, patient influence is very important. If patients ask, “How are you going to do the procedure?” it’s a driver for change. By utilizing hysteroscopy in the evaluation of the intrauterine cavity, we have the opportunity to change the face of evaluation and treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding.●

To maximize visualization and procedure ease, schedule office hysteroscopy shortly after menstruation for reproductive-age women with regular menstrual cycles, which corresponds to timing of the thinnest endometrial lining.1 By contrast, the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle may be associated with the presence of secretory endometrium, which may mimic endometrial polyps or obscure intrauterine pathology, including FIGO type 1 and 2 submucous leiomyomas.

The following patients can have their procedures scheduled at any time, as they do not regularly cycle:

- those receiving continuous hormonal contraception

- women taking menopausal hormonal therapy

- women on progestin therapy (including those using intrauterine devices).

For patients with irregular cycles, timing is crucial as the topography of the endometrium can be variable. To increase successful visualization and diagnostic accuracy, a short course of combined hormonal contraceptives2 or progestin therapy3,4 can be considered for 10-14 days, followed by a withdrawal menses, and immediate procedure scheduling after bleeding subsides, as this will produce a thin endometrium. This approach may be especially beneficial for operative procedures such as polypectomy in order to promote complete specimen extraction.

Pharmacologic endometrial preparation also is an option and has been associated with decreased procedure time and improved patient and clinician satisfaction during operative hysteroscopy.2,3 We discourage the use of hormonal pre-treatment for diagnostic hysteroscopy alone, as this may alter endometrial histology and provide misleading results. Overall, data related to pharmacologic endometrial preparation are limited to small studies with varying treatment protocols, and an optimal regimen has yet to be determined.

References

1. The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003712.

2. Cicinelli E, Pinto V, Quattromini P, et al. Endometrial preparation with estradiol plus dienogest (Qlaira) for office hysteroscopic polypectomy: randomized pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:356-359. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2011.12.020.

3. Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Muscia V, et al. Endometrial preparation with dienogest before hysteroscopic surgery: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:661-667. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4244-1.

4. Ciebiera M, Zgliczyńska M, Zgliczyński S, et al. Oral desogestrel as endometrial preparation before operative hysteroscopy: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2021;86:209-217. doi:10.1159/000514584.

- Orlando MS, Bradley LD. Implementation of office hysteroscopy for the evaluation and treatment of intrauterine pathology. Obstet Gynecol. August 3, 2022. doi: 10.1097/ AOG.0000000000004898.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, et al. Dilatation and curettage fails to detect most focal lesions in the uterine cavity in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1131-1136. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801210.x.

- The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/ AOG.0000000000003712.

- Vahdat M, Tahermanesh K, Mehdizadeh Kashi A, et al. Evening Primrose Oil effect on the ease of cervical ripening and dilatation before operative hysteroscopy. Thrita. 2015;4:7-10. doi:10.5812/thrita.29876

- Nouri B, Baghestani A, Pooransari P. Evening primrose versus misoprostol for cervical dilatation before gynecologic surgeries: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Obstet Gynecol Cancer Res. 2021;6:87-94. doi:10.30699/jogcr.6.2.87

- Verano RMA, Veloso-borromeo MG. The efficacy of evening primrose oil as a cervical ripening agent for gynecologic procedures: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. PJOG. 2015;39:24-28.

Linda Bradley, MD: The standard in ObGyn for many years has been our reliance on the blind dilation and curettage (D&C)—it has been the mainstay for evaluation of the endometrial cavity. We know that it has risks, but most importantly, the procedure has low sensitivity for detecting focal pathology. This basic lack of confirmation of lesions makes a diagnosis impossible and patients are challenged in getting adequate treatment, and will not, since they may not know what options they have for the treatment of intrauterine pathology.

Because it is a “blind procedure,” done without looking, we don’t know the endpoints, such as when is the procedure completed, how do we know we removed all of the lesions? Let’s look at our colleagues, like GI and colorectal physicians. If a patient presents with rectal bleeding, we would perform an exam, followed by either a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. If a patient were vomiting up blood, a gastroenterologist would perform an upper endoscopy, look with a tube to see if there is an ulcer or something else as a source of the bleeding. If a patient were bleeding from the bladder, a urologist would use a cystoscope for direct inspection.

Unfortunately for gynecologists, only about 15% to 25% of us will use hysteroscopy as a diagnostic method2—a method that has excellent sensitivity in detecting endocervical disease, intrauterine disease, and proximal tubal pathology. Compared with blind curettage, we can visualize the cavity; we can sample the cavity directly; we can determine what the patient has and determine the proper surgical procedure, medical therapy, or reassurance that a patient may be offered. We often are looking at focal lesions, lesions in the uterine cavity that could be cancer, so we can make a diagnosis. Or we may be looking at small things, like endometrial hyperplasia, endocervical or endometrial polyps, retained products of conception, or fibroids. We can look at uterine pathology as well as anatomic issues and malformations—such as bicornuate or septate uterus.

I actually say, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope” because it allows us to evaluate for many things. The beauty of the new office hysteroscopes is that they are miniaturized. Doctors now have the ability to use reusable devices that are as small as 3 millimeters. There are disposable ones that are up to 3.5 to 4 millimeters in size. Gynecologists have the options to choose from reusuable rigid or flexible hysteroscopes or completely disposable devices. So, truly, we now should not have an excuse for evaluating a woman’s anatomy, especially for bleeding. We should no longer rely, as we have for the last century or more, just on blind sampling, because we miss focal lesions.

OBG Management: When was the hysteroscope first introduced into the field?

Dr. Bradley: The technology employed in hysteroscopy has been around really since the last 150+ years, introduced by Dr. Pantaleoni. We just have not embraced its usefulness in our clinical practice for many years. Today, about 15% to 25% of gynecologists practicing in the United States are performing hysteroscopy in the office.1

OBG Management: How does using hysteroscopy contribute to better patient outcomes?

Dr. Bradley: We can get a more accurate diagnosis—fewer false-negatives and a high degree of sensitivity in detecting focal lesions. With D&C, much focal pathology can be left behind. In a 2001 study, 105 symptomatic postmenopausal women with bleeding and thickened lining of the uterus greater than 5 mm on ultrasound underwent blind D&C. They found that 80% of the women had intracavitary lesions and 90% had focal lesions. In fact, 87% of the patients with focal lesions still had residual pathology after the blind D&C.3 The D&C procedure missed 58% of polyps, 50% of endometrial hyperplasia, 60% of cases of complex atypical hyperplasia, and even 11% of endometrial cancers. So these numbers are just not very good. Direct inspection of the uterus, with uninterrupted visualization through hysteroscopy, with removal of lesions under direct visualization, should be our goal.

Blind sampling also poses greater risk for things like perforation. In addition, you not only can miss lesions by just scraping the endometrium, D&C also can leave lesions just floating around in the uterine cavity, with those lesions never retrieved. With office hysteroscopy, the physician can be more successful in treating a condition because once you see what is going on in the uterine cavity, you can say, “Okay, I can fix this with a surgical procedure. What instruments do I need? How much time is it going to take? Is this a straightforward case? Is it more complicated? Do I let an intern do the case? Is this for a more senior resident or fellow?” So I think it helps to direct the next steps for surgical management and even medical management, which also could be what we call “one-stop shopping.” For instance, for directed biopsies for removal of small polyps, for patients that can tolerate the procedure a little longer, the diagnostic hysteroscopy then becomes a management, an operative procedure, that really, for myself, can be done in the office. Removal of larger fibroids, because of fluid management and other concerns, would not be done in the office. Most patients tolerate office procedures, but it also depends on a patient’s weight, and her ability to relax during the procedure.

The ultimate goal for hysteroscopy is a minimum of diagnosis, meaning in less than 2, 3 minutes, you can look inside the uterus. Our devices are 3 millimeters in size; I tell my patients, it’s the size of “a piece of spaghetti or pasta,” and we will just take a look. If we see a polyp, okay, if your office is not equipped, because then you need a different type of equipment for removal, then take her to the operating room. The patient would be under brief anesthesia and go home an hour or 2 later. So really, for physicians, we just need to embrace the technology to make a diagnosis, just look, and then from there decide what is next.

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?...

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: I think first is always be patient-centric. Let patients be prepared for the procedure. We have reading materials; our nurses explain the procedure. In the office, I try to prepare the patient for success. I let her know what is going on. A friend, family member can be with her. We have a nurse that understands the procedure; she explains it well. We have a type of bed that allows the patients’ legs to rest more comfortably in the stirrups—a leg rest kind of stirrup. We use a heating pad. Some patients like to hear music. Some patients like to have aromatherapy. We are quick and efficient, and typically just talk to the patient throughout the procedure. Although some patients don’t like this explanatory, “talkative” approach—they say, “Dr. Bradley, just do the procedure. I don’t want to know you are touching the cervix. I don’t want to know that you’re prepping. Just do it.”

But I like what we called it when I was growing up: vocal-local (talk to your patient and explain as you proceed). It’s like local anesthesia. For these procedures in the office you usually do not have to use numbing medicine or a paracervical block. Look at the patient’s age, number of years in menopause, whether or not she has delivered vaginally, and what her cervix looks like. Does she have a sexually transmitted infection or pelvic inflammatory disease? Sometimes we will use misoprostol, my personal preference is oral, but there are data to suggest that vaginal can be of help.4 We suggest Motrin, Tylenol an hour or 2 before, and we always want patients to not come in on an empty stomach. There is also the option of primrose oil, a supplement, that patients buy at the drug store in the vitamin section. It’s used for cervical softening. It is taken orally.5-7

If they want, patients can watch a video—similar to watching childbirth videos when I used to deliver babies. At some point we started putting mirrors where women could see their efforts of pushing a baby out, as it might give them more willpower to push harder. Some people don’t want to look. But the majority of women will do well in this setting. I do have a small number of women that just say, “I can’t do this in the office,” and so in those cases, they can go to the operating room. But the main idea is, even in an operating room, you are not just doing a D&C. You are still going to look inside with a hysteroscope and have a great panoramic view of what is going on, and remove a lesion with an instrument while you watch. Not a process of looking with the hysteroscope, scraping with a curettage, and thinking that you are complete. Targeted removal of focal lesions under continuous visualization is the goal.

OBG Management: Can you describe the goals of the consensus document on ending blind sampling co-created by the European Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy, AAGL, and the Global Community on Hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: Our goal for this year is to get a systematic review and guidelines paper written that speaks to what we have just talked about. We want to have as many articles about why blind sampling is not beneficial, with too many misses, and now we have new technology available. We want to speak to physicians to solve the conundrum of bleeding, with equivocal ultrasounds, equivocal saline infusion, sonograms, equivocal MRIs—be able to take a look. Let’s come up to speed like our other colleagues in other specialties that “look.” A systematic review guideline document will provide the evidence that blind D&C is fraught with problems and how often we miss disease and its inherent risk.

We need to, by itself, for most of our patients, abandon D&C because we have too many missed diagnoses. As doctors we have to be lifelong learners. There was no robot back in the day. We were not able to do laparoscopic hysterectomies, there were no MRIs. I remember in our city, there was one CT scan. We just did not have a lot of technology. The half-life of medical knowledge used to be decades—you graduated in the ‘60s, you could be a great gynecologist for the next 30 years because there was not that much going on. When I finished in the mid to late ‘80s, there was no hysteroscopy training. But I have come to see its value, the science behind it.

So what I say to doctors is, “We learn so many new things, we shouldn’t get stuck in just saying, ‘I didn’t do this when I was in training.’” And if your thought is, “Oh, in my practice, I don’t have that many cases,” you still need to be able to know who in your community can be a resource to your patients. As Maya Angelou says, “When you know better, you should do better.” And that’s where I am now—to be a lifelong learner, and just do it.

Lastly, patient influence is very important. If patients ask, “How are you going to do the procedure?” it’s a driver for change. By utilizing hysteroscopy in the evaluation of the intrauterine cavity, we have the opportunity to change the face of evaluation and treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding.●

To maximize visualization and procedure ease, schedule office hysteroscopy shortly after menstruation for reproductive-age women with regular menstrual cycles, which corresponds to timing of the thinnest endometrial lining.1 By contrast, the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle may be associated with the presence of secretory endometrium, which may mimic endometrial polyps or obscure intrauterine pathology, including FIGO type 1 and 2 submucous leiomyomas.

The following patients can have their procedures scheduled at any time, as they do not regularly cycle:

- those receiving continuous hormonal contraception

- women taking menopausal hormonal therapy

- women on progestin therapy (including those using intrauterine devices).

For patients with irregular cycles, timing is crucial as the topography of the endometrium can be variable. To increase successful visualization and diagnostic accuracy, a short course of combined hormonal contraceptives2 or progestin therapy3,4 can be considered for 10-14 days, followed by a withdrawal menses, and immediate procedure scheduling after bleeding subsides, as this will produce a thin endometrium. This approach may be especially beneficial for operative procedures such as polypectomy in order to promote complete specimen extraction.

Pharmacologic endometrial preparation also is an option and has been associated with decreased procedure time and improved patient and clinician satisfaction during operative hysteroscopy.2,3 We discourage the use of hormonal pre-treatment for diagnostic hysteroscopy alone, as this may alter endometrial histology and provide misleading results. Overall, data related to pharmacologic endometrial preparation are limited to small studies with varying treatment protocols, and an optimal regimen has yet to be determined.

References

1. The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003712.

2. Cicinelli E, Pinto V, Quattromini P, et al. Endometrial preparation with estradiol plus dienogest (Qlaira) for office hysteroscopic polypectomy: randomized pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:356-359. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2011.12.020.

3. Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Muscia V, et al. Endometrial preparation with dienogest before hysteroscopic surgery: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:661-667. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4244-1.

4. Ciebiera M, Zgliczyńska M, Zgliczyński S, et al. Oral desogestrel as endometrial preparation before operative hysteroscopy: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2021;86:209-217. doi:10.1159/000514584.

Linda Bradley, MD: The standard in ObGyn for many years has been our reliance on the blind dilation and curettage (D&C)—it has been the mainstay for evaluation of the endometrial cavity. We know that it has risks, but most importantly, the procedure has low sensitivity for detecting focal pathology. This basic lack of confirmation of lesions makes a diagnosis impossible and patients are challenged in getting adequate treatment, and will not, since they may not know what options they have for the treatment of intrauterine pathology.