User login

What’s your diagnosis?

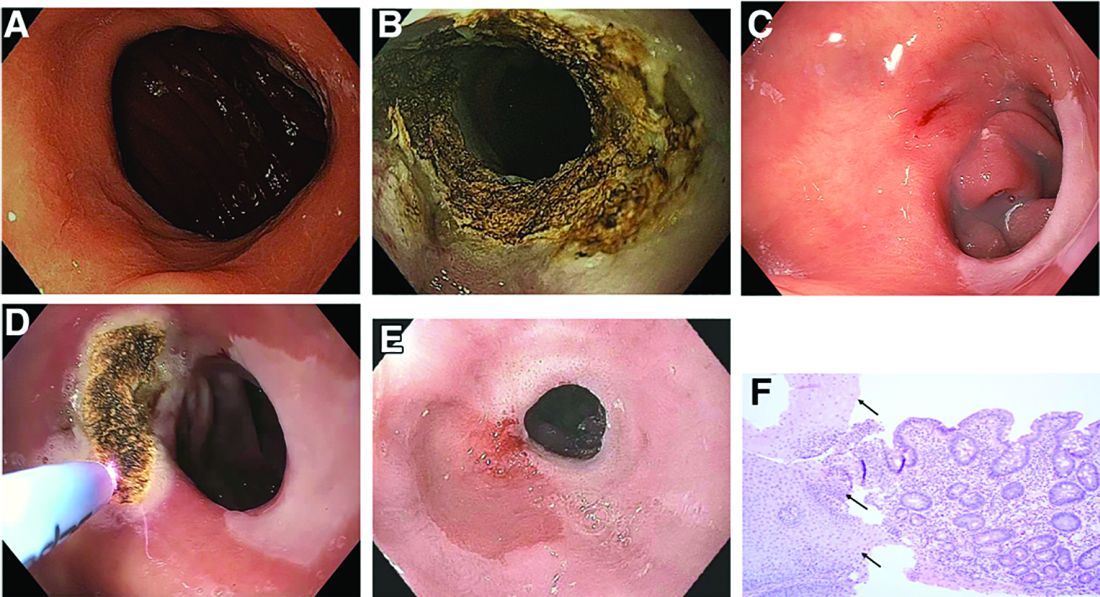

Choledocopyloric fistula secondary to peptic ulcer disease.

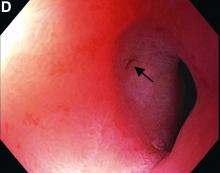

This patient has a known history of prepyloric peptic ulcer disease and related gastric outlet obstruction requiring two previous dilations. Upon endoscopic examination, we observed high-grade obstruction at the pylorus similar to previous examinations. During the initial positioning of the balloon for dilation, we inadvertently cannulated the fistula located in the pyloric channel using the guidewire (arrow in Figure D) and were able to characterize its anatomy upon contrast administration (Figure C). However, after repositioning the guidewire into the duodenal lumen beyond pyloric stricture, the balloon was inflated to a maximal diameter of 15 mm under fluoroscopic guidance. Discounting other common causes, our patient presented with an infrequent occurrence of choledocopyloric fistula secondary to peptic ulcer disease.

The most common cause of choledocoenteric fistula is bile duct inflammation due to gallstone formation, while other minor causes include neoplasms, ulcers, and inflammation of neighboring organs.1 Additionally, in recent years, fistula formation is a relatively rare complication of peptic ulcer disease due to the increased effectiveness of ulcer drugs.2 Similar to this patient's condition, cholangitis, jaundice, or anomaly of biological liver examinations are rarely observed. Consequently, diagnosis is mainly incidental with pneumobilia being the most helpful marker present in 50% of cases.3 Because cholangitis and biliary sequelae remain rare, choledocoenteric fistulas do not warrant prophylactic surgical treatment. As a result, treatment is generally focused on the underlying ulcer disease.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Stagnitti F et al. G Chir. 2000 Mar;21(3):110-7.

2. Wu MB et al. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015 Nov;89(5):240-6.

3. Dewulf E et al. J Chir (Paris). 1987 Jan;124(1):19-23.

Previously published in Gastroenterology (2019 Oct;157[4]:936-7).

Choledocopyloric fistula secondary to peptic ulcer disease.

This patient has a known history of prepyloric peptic ulcer disease and related gastric outlet obstruction requiring two previous dilations. Upon endoscopic examination, we observed high-grade obstruction at the pylorus similar to previous examinations. During the initial positioning of the balloon for dilation, we inadvertently cannulated the fistula located in the pyloric channel using the guidewire (arrow in Figure D) and were able to characterize its anatomy upon contrast administration (Figure C). However, after repositioning the guidewire into the duodenal lumen beyond pyloric stricture, the balloon was inflated to a maximal diameter of 15 mm under fluoroscopic guidance. Discounting other common causes, our patient presented with an infrequent occurrence of choledocopyloric fistula secondary to peptic ulcer disease.

The most common cause of choledocoenteric fistula is bile duct inflammation due to gallstone formation, while other minor causes include neoplasms, ulcers, and inflammation of neighboring organs.1 Additionally, in recent years, fistula formation is a relatively rare complication of peptic ulcer disease due to the increased effectiveness of ulcer drugs.2 Similar to this patient's condition, cholangitis, jaundice, or anomaly of biological liver examinations are rarely observed. Consequently, diagnosis is mainly incidental with pneumobilia being the most helpful marker present in 50% of cases.3 Because cholangitis and biliary sequelae remain rare, choledocoenteric fistulas do not warrant prophylactic surgical treatment. As a result, treatment is generally focused on the underlying ulcer disease.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Stagnitti F et al. G Chir. 2000 Mar;21(3):110-7.

2. Wu MB et al. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015 Nov;89(5):240-6.

3. Dewulf E et al. J Chir (Paris). 1987 Jan;124(1):19-23.

Previously published in Gastroenterology (2019 Oct;157[4]:936-7).

Choledocopyloric fistula secondary to peptic ulcer disease.

This patient has a known history of prepyloric peptic ulcer disease and related gastric outlet obstruction requiring two previous dilations. Upon endoscopic examination, we observed high-grade obstruction at the pylorus similar to previous examinations. During the initial positioning of the balloon for dilation, we inadvertently cannulated the fistula located in the pyloric channel using the guidewire (arrow in Figure D) and were able to characterize its anatomy upon contrast administration (Figure C). However, after repositioning the guidewire into the duodenal lumen beyond pyloric stricture, the balloon was inflated to a maximal diameter of 15 mm under fluoroscopic guidance. Discounting other common causes, our patient presented with an infrequent occurrence of choledocopyloric fistula secondary to peptic ulcer disease.

The most common cause of choledocoenteric fistula is bile duct inflammation due to gallstone formation, while other minor causes include neoplasms, ulcers, and inflammation of neighboring organs.1 Additionally, in recent years, fistula formation is a relatively rare complication of peptic ulcer disease due to the increased effectiveness of ulcer drugs.2 Similar to this patient's condition, cholangitis, jaundice, or anomaly of biological liver examinations are rarely observed. Consequently, diagnosis is mainly incidental with pneumobilia being the most helpful marker present in 50% of cases.3 Because cholangitis and biliary sequelae remain rare, choledocoenteric fistulas do not warrant prophylactic surgical treatment. As a result, treatment is generally focused on the underlying ulcer disease.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Stagnitti F et al. G Chir. 2000 Mar;21(3):110-7.

2. Wu MB et al. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015 Nov;89(5):240-6.

3. Dewulf E et al. J Chir (Paris). 1987 Jan;124(1):19-23.

Previously published in Gastroenterology (2019 Oct;157[4]:936-7).

What’s the diagnosis?

July 2021 - What's the diagnosis?

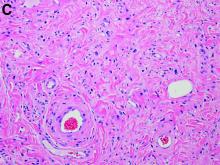

Answer: Erythropoietic protoporphyria.Figure B demonstrated massive cholestasis with brown deposits that represented protoporphyrin precipitates, which plugged the bile ducts and led to a cholestatic pattern of liver injury. Under polarized light, protoporhyrin precipitates produced Maltese crosses (Figure C), which are pathognomonic of erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP). Porphyria is a rare group of inherited heme biosynthesis disorders. EPP is an uncommon type of porphyria and is secondary to a ferrochelatase (FECH) gene mutation, which results in deficient activity of the mitochondrial enzyme FECH.1

FECH catalyzes chelation of iron into proptoporphyrin IX to form heme. The inability of protoporphyrins to be transformed into heme inhibits hepatic elimination and results in hepatocyte accumulation of protoporphyrins, leading to protoporphyrin precipitation in bile canaliculi. Painful photosensitivity (Figure A) is the most common manifestation of EPP, beginning in childhood.2 Only a small proportion of patients with EPP develop liver dysfunction but the consequences can be severe.2 Therefore, therapeutic decisions are based on limited published experience without randomized, controlled data.2 One treatment method is to attempt to remove protoporphyrins from the blood via therapeutic plasma exchange.2Our patient underwent one session of therapeutic plasma exchange; however, after this initial course of treatment, the patient’s goals of care changed and she elected to enroll in hospice. Patients with severe liver dysfunction as a result of EPP require consideration of liver transplantation in the setting of fulminant hepatic failure. Liver transplantation does not cure EPP; the graft is at risk for similar EPP-related changes.1 Only bone marrow transplantation can correct the underlying enzymatic defect in FECH.1 Although physicians are often taught “common things are common,” this case highlights a rare complication of a rare disease such as porphyria is an often forgotten or missed condition. Vigilance should be kept for other rare conditions, especially ones with curative treatments or fatal consequences. In an era where the role of liver biopsy is often questioned in favor of prediction models or noninvasive testing, we must have a low threshold to safely perform a liver biopsy when the diagnosis is unclear or a patient is deteriorating.

The quiz authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Windon AL et al. Am J Transplant. 2018 Mar;18(3):745-9.

2. Pagano MB et al. J Clin Apher. 2012;27(6):336-41.

Answer: Erythropoietic protoporphyria.Figure B demonstrated massive cholestasis with brown deposits that represented protoporphyrin precipitates, which plugged the bile ducts and led to a cholestatic pattern of liver injury. Under polarized light, protoporhyrin precipitates produced Maltese crosses (Figure C), which are pathognomonic of erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP). Porphyria is a rare group of inherited heme biosynthesis disorders. EPP is an uncommon type of porphyria and is secondary to a ferrochelatase (FECH) gene mutation, which results in deficient activity of the mitochondrial enzyme FECH.1

FECH catalyzes chelation of iron into proptoporphyrin IX to form heme. The inability of protoporphyrins to be transformed into heme inhibits hepatic elimination and results in hepatocyte accumulation of protoporphyrins, leading to protoporphyrin precipitation in bile canaliculi. Painful photosensitivity (Figure A) is the most common manifestation of EPP, beginning in childhood.2 Only a small proportion of patients with EPP develop liver dysfunction but the consequences can be severe.2 Therefore, therapeutic decisions are based on limited published experience without randomized, controlled data.2 One treatment method is to attempt to remove protoporphyrins from the blood via therapeutic plasma exchange.2Our patient underwent one session of therapeutic plasma exchange; however, after this initial course of treatment, the patient’s goals of care changed and she elected to enroll in hospice. Patients with severe liver dysfunction as a result of EPP require consideration of liver transplantation in the setting of fulminant hepatic failure. Liver transplantation does not cure EPP; the graft is at risk for similar EPP-related changes.1 Only bone marrow transplantation can correct the underlying enzymatic defect in FECH.1 Although physicians are often taught “common things are common,” this case highlights a rare complication of a rare disease such as porphyria is an often forgotten or missed condition. Vigilance should be kept for other rare conditions, especially ones with curative treatments or fatal consequences. In an era where the role of liver biopsy is often questioned in favor of prediction models or noninvasive testing, we must have a low threshold to safely perform a liver biopsy when the diagnosis is unclear or a patient is deteriorating.

The quiz authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Windon AL et al. Am J Transplant. 2018 Mar;18(3):745-9.

2. Pagano MB et al. J Clin Apher. 2012;27(6):336-41.

Answer: Erythropoietic protoporphyria.Figure B demonstrated massive cholestasis with brown deposits that represented protoporphyrin precipitates, which plugged the bile ducts and led to a cholestatic pattern of liver injury. Under polarized light, protoporhyrin precipitates produced Maltese crosses (Figure C), which are pathognomonic of erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP). Porphyria is a rare group of inherited heme biosynthesis disorders. EPP is an uncommon type of porphyria and is secondary to a ferrochelatase (FECH) gene mutation, which results in deficient activity of the mitochondrial enzyme FECH.1

FECH catalyzes chelation of iron into proptoporphyrin IX to form heme. The inability of protoporphyrins to be transformed into heme inhibits hepatic elimination and results in hepatocyte accumulation of protoporphyrins, leading to protoporphyrin precipitation in bile canaliculi. Painful photosensitivity (Figure A) is the most common manifestation of EPP, beginning in childhood.2 Only a small proportion of patients with EPP develop liver dysfunction but the consequences can be severe.2 Therefore, therapeutic decisions are based on limited published experience without randomized, controlled data.2 One treatment method is to attempt to remove protoporphyrins from the blood via therapeutic plasma exchange.2Our patient underwent one session of therapeutic plasma exchange; however, after this initial course of treatment, the patient’s goals of care changed and she elected to enroll in hospice. Patients with severe liver dysfunction as a result of EPP require consideration of liver transplantation in the setting of fulminant hepatic failure. Liver transplantation does not cure EPP; the graft is at risk for similar EPP-related changes.1 Only bone marrow transplantation can correct the underlying enzymatic defect in FECH.1 Although physicians are often taught “common things are common,” this case highlights a rare complication of a rare disease such as porphyria is an often forgotten or missed condition. Vigilance should be kept for other rare conditions, especially ones with curative treatments or fatal consequences. In an era where the role of liver biopsy is often questioned in favor of prediction models or noninvasive testing, we must have a low threshold to safely perform a liver biopsy when the diagnosis is unclear or a patient is deteriorating.

The quiz authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Windon AL et al. Am J Transplant. 2018 Mar;18(3):745-9.

2. Pagano MB et al. J Clin Apher. 2012;27(6):336-41.

A 66-year-old White woman with tetralogy of Fallot status after remote pulmonic valve surgery, hypothyroidism, and previous cholecystectomy presented to her primary care provider with 2 days of constant, dull, right upper quadrant pain with nausea but without fever, association with meals, or association with defecation. Her home medications included low-dose aspirin and levothyroxine. Her physical examination revealed normal vital signs, a body mass index of 29 kg/m2, right upper quadrant tenderness to palpation without peritoneal signs, and normal bowel sounds. The remainder of her examination was normal.

The patient underwent an exhaustive evaluation beginning with laboratory tests, which revealed a normal complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, lipase, international normalized ratio, and urinalysis. Her liver function tests results showed aspartate aminotransferase 118 international IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 117 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 147 IU/L, and total bilirubin 17.6 mg/dL, with a direct bilirubin of 11.9 mg/dL.

Her liver function tests were last checked 18 months prior and were normal. A liver ultrasound examination revealed cirrhotic morphology without ascites or hepatic or portal vein thrombosis. A magnetic resonance imaging study of the liver revealed morphologic changes of hepatic cirrhosis without portal hypertension, biliary dilation, or stricturing. Additionally, hepatitis A IgM, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core IgM and IgG, hepatitis C antibody, ceruloplasmin, antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-liver-kidney-microsomal antibody, quantitative immunoglobulins, antimitochondrial antibody, alpha-1 antitrypsin phenotype, phosphatidylethanolamine, serum protein electrophoresis, and alpha fetoprotein were reassuring. Later, the patient reported sensitivity to the sun, described as a "sun allergy" with irritation on her hands (Figure A). Mentation remained normal; however, given progressive worsening hepatic function evidenced by international normalized ratio of 1.7 and bilirubin of 27.6 mg/dL, the patient was urgently admitted for expedited portal manometry with transjugular liver biopsy. The hepatic venous pressure gradient was 23 mm Hg. The liver biopsy images are shown in Figure B, C.

What's the diagnosis?

What's your diagnosis?

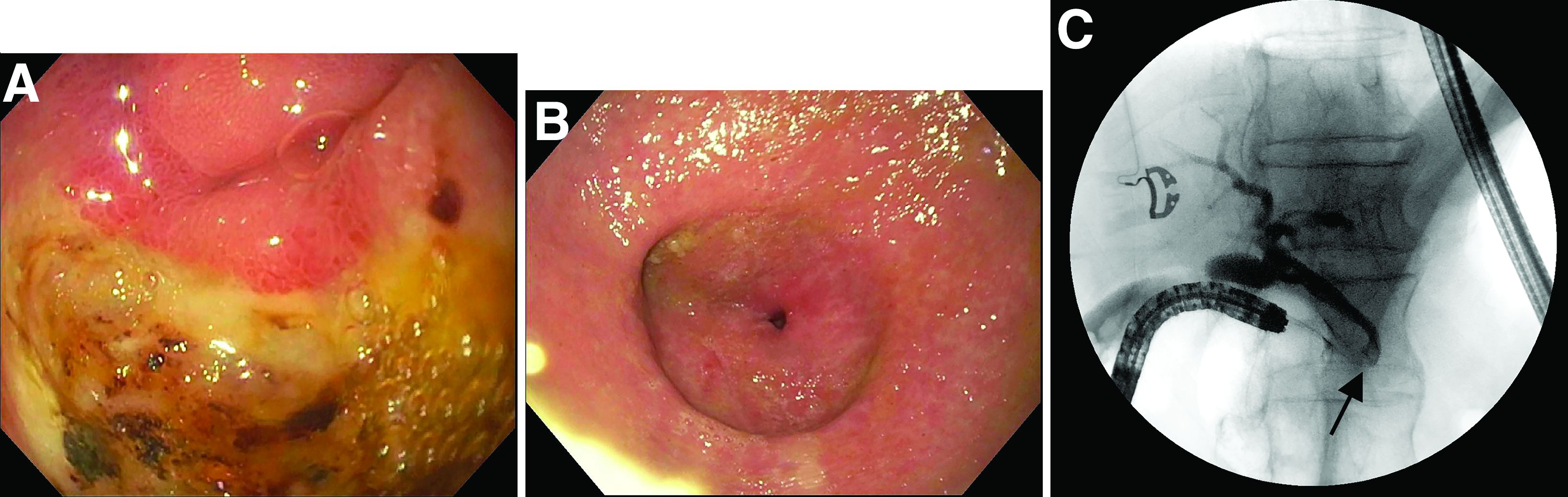

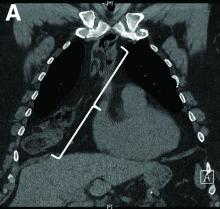

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

How should this condition be managed?

March 2021 - What's your diagnosis?

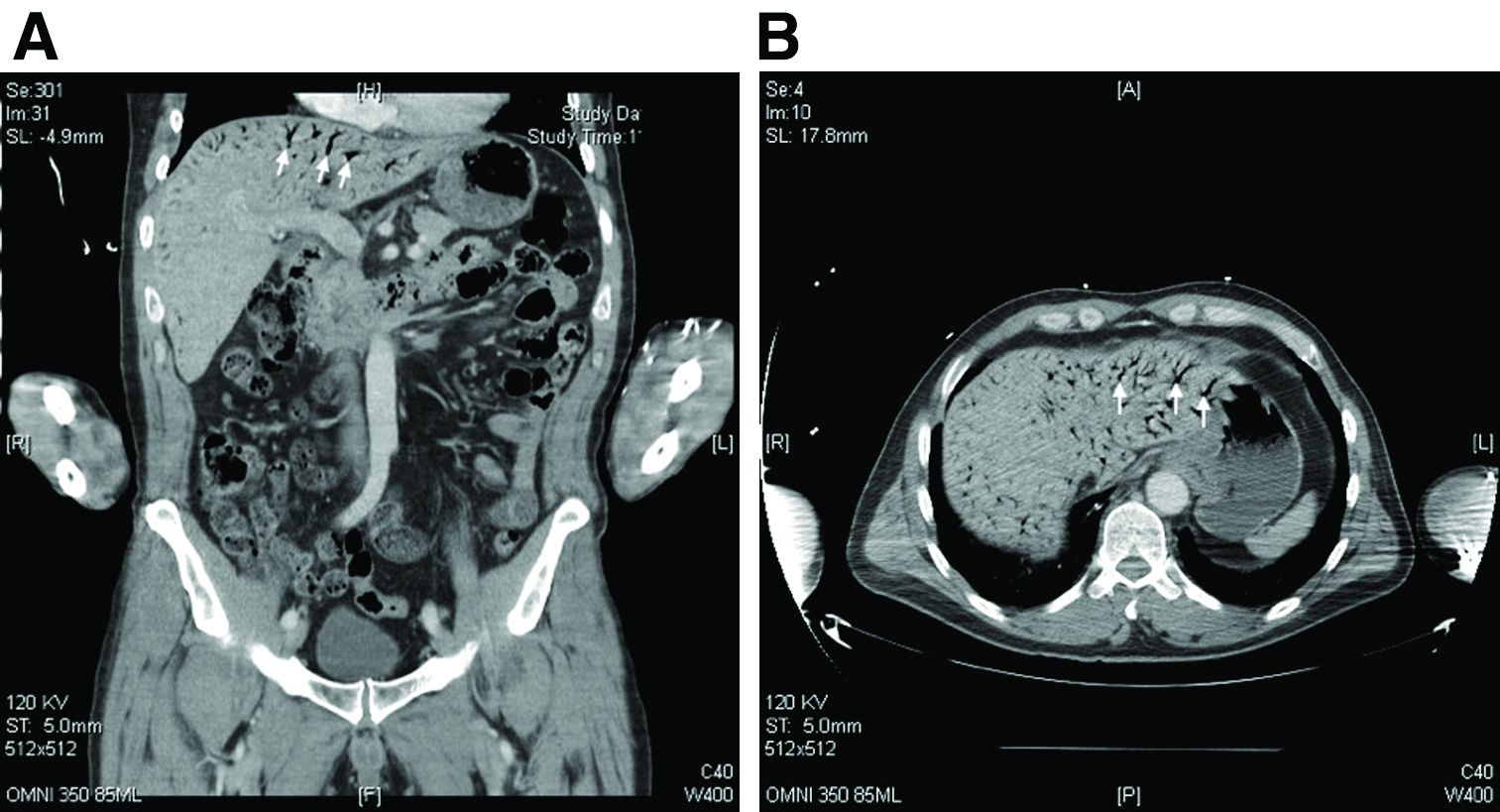

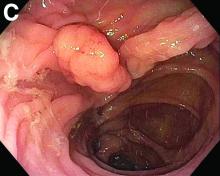

Answer: esophageal Crohn’s disease.

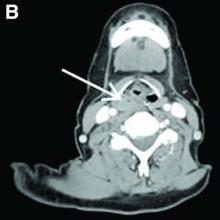

The esophageal biopsies demonstrate severe chronic inflammation of the subepithelial tissue with marked lymphocytic infiltration and the presence of granulomas containing multinucleate giant cells (Figure B, arrow). Given his immunosuppression with azathioprine, stains for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and mycobacterial and fungal organisms were performed and returned negative.

A diagnosis of esophageal Crohn’s disease was made, and adalimumab was recommenced. A rapid and dramatic clinical improvement was observed, with complete resolution of his symptoms. Adalimumab trough levels were checked and found to be therapeutic (9 mcg/mL). Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy at 6 months showed healing of the esophageal ulceration, with residual scarring and the presence of two postinflammatory polyps (Figure C). The histopathology was consistent with quiescent Crohn’s disease.

Recognition of this very rare manifestation of Crohn’s is challenging but important so that appropriate treatment is not delayed. It is both unexplained and unusual for Crohn’s disease to flare in a new gastrointestinal location. Moreover, although accurate adult prevalence data for esophageal Crohn’s are scarce, retrospective data suggest it is present in just 0.2% of Crohn’s disease patients.1 By contrast, gastroesophageal reflux disease prevalence is between 18% and 28% of the total population in North America. Esophageal Crohn’s commonly leads to nonspecific symptoms that resemble gastroesophageal reflux disease, and as for acid reflux, the mid and distal esophagus are the most common sites of involvement. In keeping with the behavior of luminal Crohn’s disease, progression from inflammation to stenosis (causing marked dysphagia) or perforation (leading to fistula formation) may occur.2 Histopathology typically demonstrates chronic inflammation, although noncaseating granulomas are seen in the minority (7%-39%) of patients.3 Multiple deep biopsies are recommended to improve diagnostic yield,3 and our case demonstrates the value of repeat endoscopic evaluation.

Unsurprisingly given its rarity, there are no systematic data on optimal treatment. Acid suppression therapy may provide symptomatic benefit but does not treat the underlying inflammatory process. Oral prednisolone, topical budesonide, and immunomodulators including thiopurines have been used in case series, but biological therapy (typically anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy) is likely to be required for severe disease.2,3 There are no data on the use of more novel biologics. Critically, almost all reported cases of esophageal Crohn’s disease have concomitant intestinal disease, and the presence of upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s predicts a more severe disease phenotype, supporting the use of more aggressive medical therapy in this instance.3

References

1. Decker GA et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):113-9.

2. De Felice KM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Sep;21(9):2106-13.

3. Laube R et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;33(2):355-64.

Answer: esophageal Crohn’s disease.

The esophageal biopsies demonstrate severe chronic inflammation of the subepithelial tissue with marked lymphocytic infiltration and the presence of granulomas containing multinucleate giant cells (Figure B, arrow). Given his immunosuppression with azathioprine, stains for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and mycobacterial and fungal organisms were performed and returned negative.

A diagnosis of esophageal Crohn’s disease was made, and adalimumab was recommenced. A rapid and dramatic clinical improvement was observed, with complete resolution of his symptoms. Adalimumab trough levels were checked and found to be therapeutic (9 mcg/mL). Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy at 6 months showed healing of the esophageal ulceration, with residual scarring and the presence of two postinflammatory polyps (Figure C). The histopathology was consistent with quiescent Crohn’s disease.

Recognition of this very rare manifestation of Crohn’s is challenging but important so that appropriate treatment is not delayed. It is both unexplained and unusual for Crohn’s disease to flare in a new gastrointestinal location. Moreover, although accurate adult prevalence data for esophageal Crohn’s are scarce, retrospective data suggest it is present in just 0.2% of Crohn’s disease patients.1 By contrast, gastroesophageal reflux disease prevalence is between 18% and 28% of the total population in North America. Esophageal Crohn’s commonly leads to nonspecific symptoms that resemble gastroesophageal reflux disease, and as for acid reflux, the mid and distal esophagus are the most common sites of involvement. In keeping with the behavior of luminal Crohn’s disease, progression from inflammation to stenosis (causing marked dysphagia) or perforation (leading to fistula formation) may occur.2 Histopathology typically demonstrates chronic inflammation, although noncaseating granulomas are seen in the minority (7%-39%) of patients.3 Multiple deep biopsies are recommended to improve diagnostic yield,3 and our case demonstrates the value of repeat endoscopic evaluation.

Unsurprisingly given its rarity, there are no systematic data on optimal treatment. Acid suppression therapy may provide symptomatic benefit but does not treat the underlying inflammatory process. Oral prednisolone, topical budesonide, and immunomodulators including thiopurines have been used in case series, but biological therapy (typically anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy) is likely to be required for severe disease.2,3 There are no data on the use of more novel biologics. Critically, almost all reported cases of esophageal Crohn’s disease have concomitant intestinal disease, and the presence of upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s predicts a more severe disease phenotype, supporting the use of more aggressive medical therapy in this instance.3

References

1. Decker GA et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):113-9.

2. De Felice KM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Sep;21(9):2106-13.

3. Laube R et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;33(2):355-64.

Answer: esophageal Crohn’s disease.

The esophageal biopsies demonstrate severe chronic inflammation of the subepithelial tissue with marked lymphocytic infiltration and the presence of granulomas containing multinucleate giant cells (Figure B, arrow). Given his immunosuppression with azathioprine, stains for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and mycobacterial and fungal organisms were performed and returned negative.

A diagnosis of esophageal Crohn’s disease was made, and adalimumab was recommenced. A rapid and dramatic clinical improvement was observed, with complete resolution of his symptoms. Adalimumab trough levels were checked and found to be therapeutic (9 mcg/mL). Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy at 6 months showed healing of the esophageal ulceration, with residual scarring and the presence of two postinflammatory polyps (Figure C). The histopathology was consistent with quiescent Crohn’s disease.

Recognition of this very rare manifestation of Crohn’s is challenging but important so that appropriate treatment is not delayed. It is both unexplained and unusual for Crohn’s disease to flare in a new gastrointestinal location. Moreover, although accurate adult prevalence data for esophageal Crohn’s are scarce, retrospective data suggest it is present in just 0.2% of Crohn’s disease patients.1 By contrast, gastroesophageal reflux disease prevalence is between 18% and 28% of the total population in North America. Esophageal Crohn’s commonly leads to nonspecific symptoms that resemble gastroesophageal reflux disease, and as for acid reflux, the mid and distal esophagus are the most common sites of involvement. In keeping with the behavior of luminal Crohn’s disease, progression from inflammation to stenosis (causing marked dysphagia) or perforation (leading to fistula formation) may occur.2 Histopathology typically demonstrates chronic inflammation, although noncaseating granulomas are seen in the minority (7%-39%) of patients.3 Multiple deep biopsies are recommended to improve diagnostic yield,3 and our case demonstrates the value of repeat endoscopic evaluation.

Unsurprisingly given its rarity, there are no systematic data on optimal treatment. Acid suppression therapy may provide symptomatic benefit but does not treat the underlying inflammatory process. Oral prednisolone, topical budesonide, and immunomodulators including thiopurines have been used in case series, but biological therapy (typically anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy) is likely to be required for severe disease.2,3 There are no data on the use of more novel biologics. Critically, almost all reported cases of esophageal Crohn’s disease have concomitant intestinal disease, and the presence of upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s predicts a more severe disease phenotype, supporting the use of more aggressive medical therapy in this instance.3

References

1. Decker GA et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):113-9.

2. De Felice KM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Sep;21(9):2106-13.

3. Laube R et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;33(2):355-64.

A 49-year-old man presented with symptoms of retrosternal discomfort and mild dysphagia to solids. He had a 30-year history of ileocolonic Crohn's disease requiring previous resections of the ileum and sigmoid colon. Clinical remission had been achieved with adalimumab and azathioprine combination therapy, with the subsequent decision to de-escalate to maintenance with azathioprine monotherapy after consideration of the risks and benefits of dual immunosuppression. After 5 years of azathioprine monotherapy, complete endoscopic remission was reconfirmed at a recent ileocolonoscopy.

To investigate his upper gastrointestinal symptoms he underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy that demonstrated severe esophagitis (Los Angeles grade D) of the lower esophagus with biopsies confirming apparent reflux esophagitis. However, his symptoms worsened despite a course of high dose proton pump inhibitor, and a repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed. This demonstrated deep longitudinal ulcers and inflammation of the lower two-thirds of the esophagus (Figure A). Biopsies were sent for histopathologic analysis (Figure B).

January 2021 - What's your diagnosis?

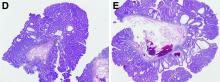

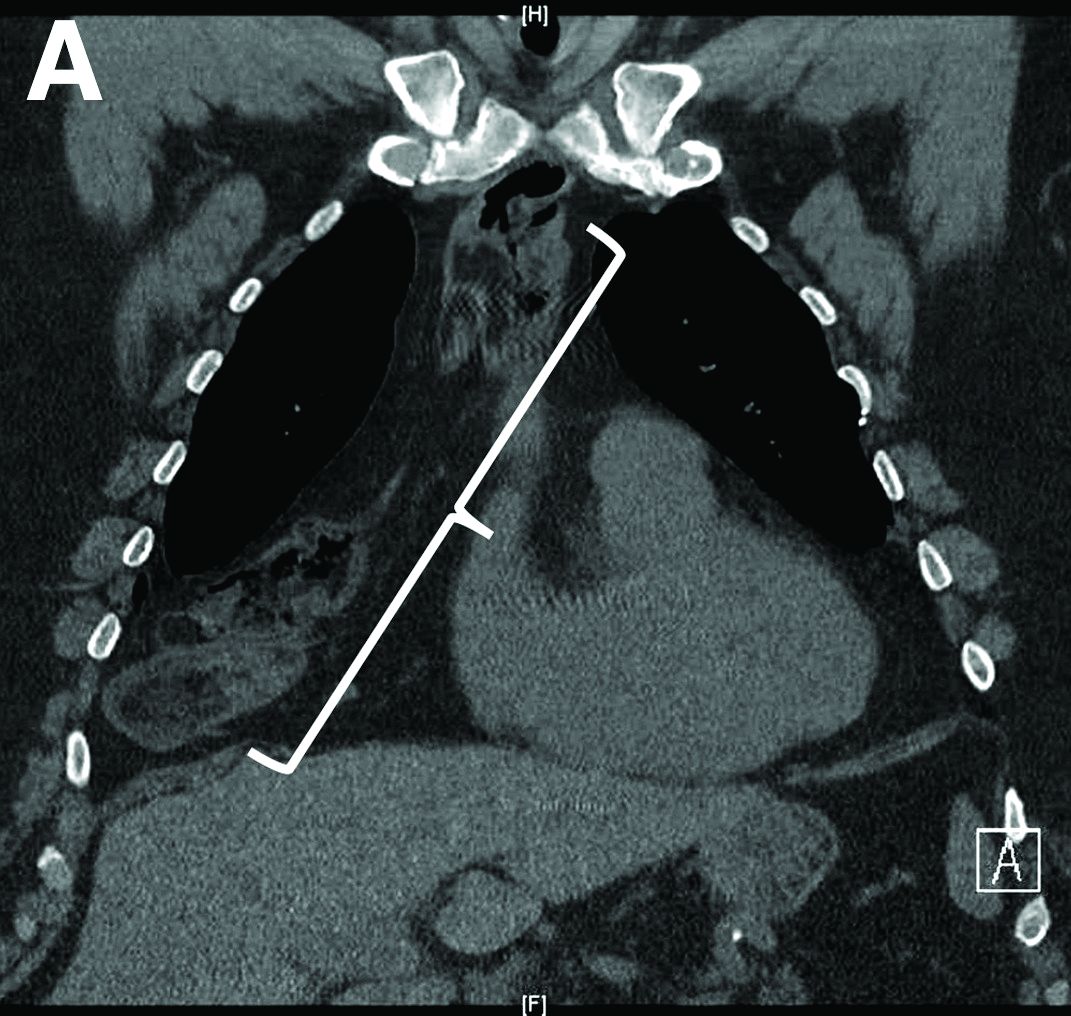

Tubulovillous adenoma within a colonic interposition

In addition to the source of the bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, the upper endoscopy revealed a large adenomatous polyp along with evidence of significant diverticular disease throughout the interposed colon. The polyp was later resected completely and histopathologic evaluation confirmed the polyp to be a tubulovillous adenoma without dysplasia (Figures D, E).

Esophageal replacement by colonic interposition is a rare surgical procedure typically only used in advanced esophageal cancers, end-stage stricturing disease, or severe caustic ingestions.1 Because of the scarcity of cases, there is little known regarding the long-term outcomes of the procedure.1

There are a growing number of reports demonstrating the presence of colon polyps within the interposed colon.2,3 These polyps range from simple adenomas to high-grade adenocarcinomas.2,3 In the majority of cases, the interposition procedure was performed later in the patient’s life, leading to the potential that the polyp or subsequent adenocarcinoma arose from a missed lesion. However, in our case the interposition was performed in adolescence, more than 50 years before presentation, strongly suggesting that the lesion likely occurred de novo.

Fecal retention is commonly thought to contribute toward polyp development and diverticula in the colon, but in the case of our patient the segment of colon used for his neoesophagus would have only been exposed to stool until adolescence. It is possible that significant stasis of food owing to poor peristaltic activity in the interposed colonic segment and the presence of diverticula may have both contributed to polyp development. The fact that diverticular pouches are identified directly under the polyp would seem to support the role of food retention in polyp formation (Figures B, C). Regardless of the inciting event, this case demonstrates that the molecular pathogenesis of colon polyp formation is likely preserved, irrespective of the presence of stool or the physical location of the colon.

Had our patient not received an endoscopy for his GI bleed, the adenomatous polyp would not have been identified and removed, and likely would have continued to progress into adenocarcinoma.

Given our findings, gastroenterologists should be aware of this condition in this patient population and long-term surveillance endoscopies should be considered in all patients with colonic interpositions.

References

1. Barbosa B. et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy264.

2. Fisher R.A. et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-10.

3. Ramage L. et al. Surgery. 2012;10:304-5.

ginews@gastro.org

Tubulovillous adenoma within a colonic interposition

In addition to the source of the bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, the upper endoscopy revealed a large adenomatous polyp along with evidence of significant diverticular disease throughout the interposed colon. The polyp was later resected completely and histopathologic evaluation confirmed the polyp to be a tubulovillous adenoma without dysplasia (Figures D, E).

Esophageal replacement by colonic interposition is a rare surgical procedure typically only used in advanced esophageal cancers, end-stage stricturing disease, or severe caustic ingestions.1 Because of the scarcity of cases, there is little known regarding the long-term outcomes of the procedure.1

There are a growing number of reports demonstrating the presence of colon polyps within the interposed colon.2,3 These polyps range from simple adenomas to high-grade adenocarcinomas.2,3 In the majority of cases, the interposition procedure was performed later in the patient’s life, leading to the potential that the polyp or subsequent adenocarcinoma arose from a missed lesion. However, in our case the interposition was performed in adolescence, more than 50 years before presentation, strongly suggesting that the lesion likely occurred de novo.

Fecal retention is commonly thought to contribute toward polyp development and diverticula in the colon, but in the case of our patient the segment of colon used for his neoesophagus would have only been exposed to stool until adolescence. It is possible that significant stasis of food owing to poor peristaltic activity in the interposed colonic segment and the presence of diverticula may have both contributed to polyp development. The fact that diverticular pouches are identified directly under the polyp would seem to support the role of food retention in polyp formation (Figures B, C). Regardless of the inciting event, this case demonstrates that the molecular pathogenesis of colon polyp formation is likely preserved, irrespective of the presence of stool or the physical location of the colon.

Had our patient not received an endoscopy for his GI bleed, the adenomatous polyp would not have been identified and removed, and likely would have continued to progress into adenocarcinoma.

Given our findings, gastroenterologists should be aware of this condition in this patient population and long-term surveillance endoscopies should be considered in all patients with colonic interpositions.

References

1. Barbosa B. et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy264.

2. Fisher R.A. et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-10.

3. Ramage L. et al. Surgery. 2012;10:304-5.

ginews@gastro.org

Tubulovillous adenoma within a colonic interposition

In addition to the source of the bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, the upper endoscopy revealed a large adenomatous polyp along with evidence of significant diverticular disease throughout the interposed colon. The polyp was later resected completely and histopathologic evaluation confirmed the polyp to be a tubulovillous adenoma without dysplasia (Figures D, E).

Esophageal replacement by colonic interposition is a rare surgical procedure typically only used in advanced esophageal cancers, end-stage stricturing disease, or severe caustic ingestions.1 Because of the scarcity of cases, there is little known regarding the long-term outcomes of the procedure.1

There are a growing number of reports demonstrating the presence of colon polyps within the interposed colon.2,3 These polyps range from simple adenomas to high-grade adenocarcinomas.2,3 In the majority of cases, the interposition procedure was performed later in the patient’s life, leading to the potential that the polyp or subsequent adenocarcinoma arose from a missed lesion. However, in our case the interposition was performed in adolescence, more than 50 years before presentation, strongly suggesting that the lesion likely occurred de novo.

Fecal retention is commonly thought to contribute toward polyp development and diverticula in the colon, but in the case of our patient the segment of colon used for his neoesophagus would have only been exposed to stool until adolescence. It is possible that significant stasis of food owing to poor peristaltic activity in the interposed colonic segment and the presence of diverticula may have both contributed to polyp development. The fact that diverticular pouches are identified directly under the polyp would seem to support the role of food retention in polyp formation (Figures B, C). Regardless of the inciting event, this case demonstrates that the molecular pathogenesis of colon polyp formation is likely preserved, irrespective of the presence of stool or the physical location of the colon.

Had our patient not received an endoscopy for his GI bleed, the adenomatous polyp would not have been identified and removed, and likely would have continued to progress into adenocarcinoma.

Given our findings, gastroenterologists should be aware of this condition in this patient population and long-term surveillance endoscopies should be considered in all patients with colonic interpositions.

References

1. Barbosa B. et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy264.

2. Fisher R.A. et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-10.

3. Ramage L. et al. Surgery. 2012;10:304-5.

ginews@gastro.org

Nine months before his current presentation, he was evaluated for episodic dysphagia with associated prandial and postprandial chest discomfort and shortness of breath, which he reported had been gradually worsening over the past 20 years. The patient had undergone an exhaustive cardiopulmonary evaluation with cross-sectional imaging (Figure A, neoesophagus bracketed) and it was suspected that his symptoms were partially explained by retained food in his neoesophagus. A promotility agent was prescribed but no intervention was performed.

The patient was hemodynamically stabilized with aggressive fluid resuscitation and blood products. An urgent bedside esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed. An ulcer with a visible vessel was identified in the duodenal bulb and treated with both mechanical clipping and cauterization. However, incidental findings were noted within the esophagus (Figures B, C).

Based on the clinical history, what is the most likely underlying etiology for the incidental findings in the esophagus?

October 2020 - What's the diagnosis?

Answer: Celiac hepatitis

Endoscopic biopsy of this severely scalloped duodenal mucosa demonstrated characteristic findings of gluten-sensitive enteropathy, or celiac disease. Celiac disease involvement of the liver is a common extraintestinal manifestation of this immune-mediated disorder, termed celiac hepatitis. Celiac hepatitis affects 40% of adults with celiac disease.1 The pathogenesis is poorly understood, but posited to be related to autoimmunity or toxin-mediated liver injury in the setting of gluten exposure, gut permeability, chronic inflammation, and host susceptibility, among other mechanisms.1-3

Clinical manifestations of celiac hepatitis range from unexplained enzyme elevations in the absence of known liver disease to autoimmune hepatitis to hepatic steatosis, and even cirrhosis.1 The initial presentation can also be elevated liver enzymes in the setting of known celiac disease, without known hepatic disease. Histology of the liver is similarly variable, from a mild or a chronic hepatitis to steatohepatitis and even fibrosis.2 Elevated transaminases less than five times the upper limit of normal when found at celiac diagnosis suggest celiac hepatitis, and do not require further workup.1 For these individuals, response to a gluten-free diet should be monitored and liver chemistries should be repeated at 6–12 months. Persistently elevated aminotransferases should prompt further workup.1 Generally, enzyme elevation and even the histologic appearance of the liver improve after implementation of a gluten-free diet, although not all.2 In celiac hepatitis associated with autoimmune liver disease, immunosuppression may be required in addition to abstaining from gluten.3 Our patient was found to have a tissue transglutaminase level > 100 U/mL (normal, < 4 U/mL). He began a gluten-free diet guided by a nutritionist 4 weeks ago, with rapid improvement in abdominal symptoms, and will be followed to ensure normalization of liver enzymes, which can take up to 1 year.

References

1. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Liver involvement in celiac disease. Minerva Med. 2008;99:595-604.

2. Majumdar K, Sakhuja P, Puri AS, et al. Coeliac disease and the liver: spectrum of liver histology, serology and treatment response at a tertiary referral centre. J Clin Pathol. 2018;71:412-9.

3. Marciano F, Savoia M, Vajro P. Celiac disease-related hepatic injury: insights into associated conditions and underlying pathomechanisms. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:112-9.

ginews@gastro.org

Answer: Celiac hepatitis

Endoscopic biopsy of this severely scalloped duodenal mucosa demonstrated characteristic findings of gluten-sensitive enteropathy, or celiac disease. Celiac disease involvement of the liver is a common extraintestinal manifestation of this immune-mediated disorder, termed celiac hepatitis. Celiac hepatitis affects 40% of adults with celiac disease.1 The pathogenesis is poorly understood, but posited to be related to autoimmunity or toxin-mediated liver injury in the setting of gluten exposure, gut permeability, chronic inflammation, and host susceptibility, among other mechanisms.1-3

Clinical manifestations of celiac hepatitis range from unexplained enzyme elevations in the absence of known liver disease to autoimmune hepatitis to hepatic steatosis, and even cirrhosis.1 The initial presentation can also be elevated liver enzymes in the setting of known celiac disease, without known hepatic disease. Histology of the liver is similarly variable, from a mild or a chronic hepatitis to steatohepatitis and even fibrosis.2 Elevated transaminases less than five times the upper limit of normal when found at celiac diagnosis suggest celiac hepatitis, and do not require further workup.1 For these individuals, response to a gluten-free diet should be monitored and liver chemistries should be repeated at 6–12 months. Persistently elevated aminotransferases should prompt further workup.1 Generally, enzyme elevation and even the histologic appearance of the liver improve after implementation of a gluten-free diet, although not all.2 In celiac hepatitis associated with autoimmune liver disease, immunosuppression may be required in addition to abstaining from gluten.3 Our patient was found to have a tissue transglutaminase level > 100 U/mL (normal, < 4 U/mL). He began a gluten-free diet guided by a nutritionist 4 weeks ago, with rapid improvement in abdominal symptoms, and will be followed to ensure normalization of liver enzymes, which can take up to 1 year.

References

1. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Liver involvement in celiac disease. Minerva Med. 2008;99:595-604.

2. Majumdar K, Sakhuja P, Puri AS, et al. Coeliac disease and the liver: spectrum of liver histology, serology and treatment response at a tertiary referral centre. J Clin Pathol. 2018;71:412-9.

3. Marciano F, Savoia M, Vajro P. Celiac disease-related hepatic injury: insights into associated conditions and underlying pathomechanisms. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:112-9.

ginews@gastro.org

Answer: Celiac hepatitis

Endoscopic biopsy of this severely scalloped duodenal mucosa demonstrated characteristic findings of gluten-sensitive enteropathy, or celiac disease. Celiac disease involvement of the liver is a common extraintestinal manifestation of this immune-mediated disorder, termed celiac hepatitis. Celiac hepatitis affects 40% of adults with celiac disease.1 The pathogenesis is poorly understood, but posited to be related to autoimmunity or toxin-mediated liver injury in the setting of gluten exposure, gut permeability, chronic inflammation, and host susceptibility, among other mechanisms.1-3

Clinical manifestations of celiac hepatitis range from unexplained enzyme elevations in the absence of known liver disease to autoimmune hepatitis to hepatic steatosis, and even cirrhosis.1 The initial presentation can also be elevated liver enzymes in the setting of known celiac disease, without known hepatic disease. Histology of the liver is similarly variable, from a mild or a chronic hepatitis to steatohepatitis and even fibrosis.2 Elevated transaminases less than five times the upper limit of normal when found at celiac diagnosis suggest celiac hepatitis, and do not require further workup.1 For these individuals, response to a gluten-free diet should be monitored and liver chemistries should be repeated at 6–12 months. Persistently elevated aminotransferases should prompt further workup.1 Generally, enzyme elevation and even the histologic appearance of the liver improve after implementation of a gluten-free diet, although not all.2 In celiac hepatitis associated with autoimmune liver disease, immunosuppression may be required in addition to abstaining from gluten.3 Our patient was found to have a tissue transglutaminase level > 100 U/mL (normal, < 4 U/mL). He began a gluten-free diet guided by a nutritionist 4 weeks ago, with rapid improvement in abdominal symptoms, and will be followed to ensure normalization of liver enzymes, which can take up to 1 year.

References

1. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Liver involvement in celiac disease. Minerva Med. 2008;99:595-604.

2. Majumdar K, Sakhuja P, Puri AS, et al. Coeliac disease and the liver: spectrum of liver histology, serology and treatment response at a tertiary referral centre. J Clin Pathol. 2018;71:412-9.

3. Marciano F, Savoia M, Vajro P. Celiac disease-related hepatic injury: insights into associated conditions and underlying pathomechanisms. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:112-9.

ginews@gastro.org

Question: A 24-year-old white man with depression and anxiety disorder is referred for an isolated alanine aminotransferase elevation found by his primary medical doctor on routine blood work. He denies a family history of liver disease, although he does report a family history of lupus. He denies risk factors for viral hepatitis. He drinks about three alcoholic beverages per week. His family is originally from Germany and Ireland. He denies use of over-the-counter medications or supplements beyond a rare use of ibuprofen. His only medication is daily escitalopram. On further questioning he also reports abdominal pain. The abdominal pain is described as dull, constant, right upper quadrant pain near his rib cage. The pain occasionally becomes worse if he eats fast foods. He also notes a 3-month history of bloating and alternating bowel habits between diarrhea and constipation.

Physical examination is notable for unremarkable vital signs and a normal body mass index. He has no stigmata of chronic liver disease or hepatomegaly. He has normal bowel sounds without any tenderness to palpation. An in-office FibroScan is normal with a value of 3 kPa. Aspartate aminotransferase is 33 U/L (normal, 10-40 U/L). Viral serologies are notable for nonreactive hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody. Hepatitis C virus RNA is undetectable. Ferritin, iron, and creatine kinase are normal. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, antimitochondrial antibody, and antinuclear antibody are negative. Ceruloplasmin is normal and alpha-1 antitrypsin showed MZ phenotype. An abdominal ultrasound scan shows a normal size liver, normal echotexture, and sludge in the gallbladder, without any intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct dilation. The extrahepatic bile duct diameter is 0.3 cm.

Antismooth muscle and quantitative immunoglobulin tests were ordered. An endoscopy is performed for abdominal pain, and duodenal endoscopic and histologic images are provided.

What is your diagnosis? - September 2020

Capillaria hepatica infection

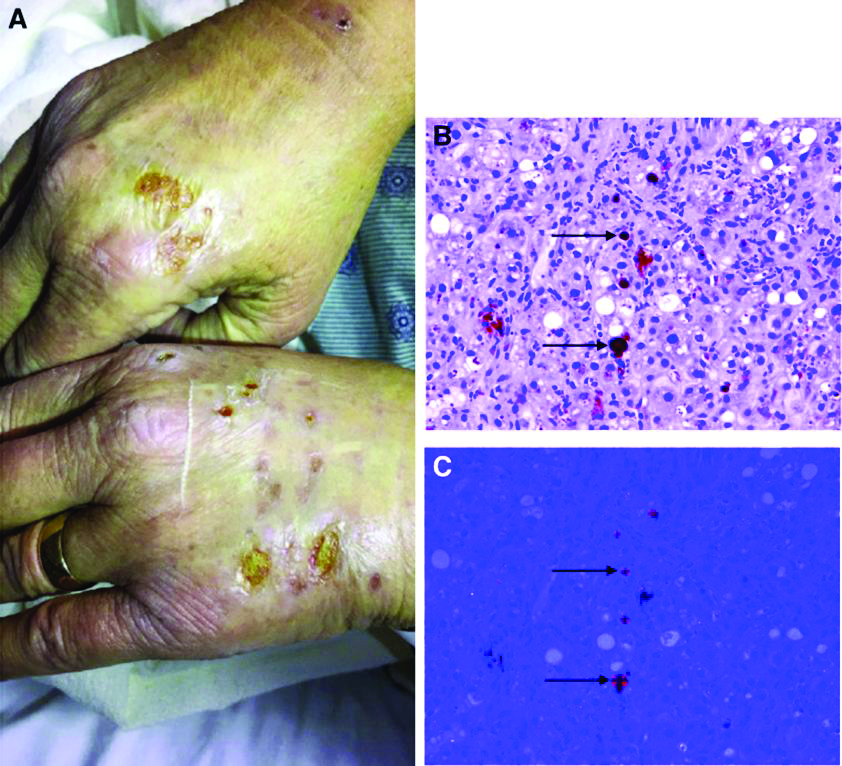

The liver parenchyma shows spindle-shaped eosinophilic eggs surrounded by eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates and epithelioid granuloma (original magnification ×200). Figure B shows spindle-shaped eosinophilic eggs with shells, radial striations, and visible polar body, containing granular eosinophilic debris (original magnification ×1000), consistent with Capillaria hepatica. Figure C reveals crescent-shaped, degenerated adult worms of C. hepatica showing longitudinal bacillary bands, vacuolated intestine, and convoluted gonads surrounded by intense eosinophilic inflammation in liver parenchyma (original magnification ×400). The outer cuticle is not appreciated because the worms are degenerated.

A review of history revealed that the child played with stray cats and had pica. He was given 10 mg/kg of oral albendazole for 16 weeks and 1 mg/kg of oral prednisolone for the first 2 weeks to prevent paradoxical inflammatory response. Thereafter, prednisolone was tapered and stopped. Pyrexia, liver size, AEC, and liver enzymes normalized at 24 hours, 72 hours, 4 months, and 5 months, respectively. At 12 months of follow-up, the child is asymptomatic.

Capillaria hepatica is a rare nematodal invasive parasitosis where humans are the dead-end host; the main lifecycle occurs between rodents and their predators. Adult worms live, mate, and lay noninfective unembryonated eggs in rodent livers. Embryogenesis occurs only after contact with the soil in two settings: 1) the rodent is eaten by the predator and the unembryonated eggs are released in the predator's feces or 2) carcass disintegration after natural death of the rodent. Humans incidentally ingest the infective embryonated eggs by soil to mouth transmission. They hatch in the human intestine and the larvae migrate through the portal vein into the liver where they mature into adult worms. In the liver, the cycle continues with the adult worms mating and laying eggs. This elicits intense inflammation with systemic symptoms.1 In the index case, we hypothesize that the toddler with pica would have come in contact with soil in the vicinity of the stray cats. This soil would have initially contained the feline feces with unembryonated eggs that later underwent embryogenesis. The triad of fever, hepatomegaly, and eosinophilia is the hallmark and characteristic liver histology clinches the diagnosis. Duration of anthelminthic therapy should be guided by AEC response.2,3

References

1. Wright K.A. Observation on the life cycle of Capillaria hepatica with a description of the adult. Can J Zool. 1961;39:167-82.

2. Berger T. Degrémont A. Gebbers J.O. et al. Hepatic capillariasis in a 1-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;149:333-633.

3. Choe G. Lee H.S. Seo J.K. et al. Hepatic capillariasis: first case report in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:610-25.

Capillaria hepatica infection

The liver parenchyma shows spindle-shaped eosinophilic eggs surrounded by eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates and epithelioid granuloma (original magnification ×200). Figure B shows spindle-shaped eosinophilic eggs with shells, radial striations, and visible polar body, containing granular eosinophilic debris (original magnification ×1000), consistent with Capillaria hepatica. Figure C reveals crescent-shaped, degenerated adult worms of C. hepatica showing longitudinal bacillary bands, vacuolated intestine, and convoluted gonads surrounded by intense eosinophilic inflammation in liver parenchyma (original magnification ×400). The outer cuticle is not appreciated because the worms are degenerated.

A review of history revealed that the child played with stray cats and had pica. He was given 10 mg/kg of oral albendazole for 16 weeks and 1 mg/kg of oral prednisolone for the first 2 weeks to prevent paradoxical inflammatory response. Thereafter, prednisolone was tapered and stopped. Pyrexia, liver size, AEC, and liver enzymes normalized at 24 hours, 72 hours, 4 months, and 5 months, respectively. At 12 months of follow-up, the child is asymptomatic.

Capillaria hepatica is a rare nematodal invasive parasitosis where humans are the dead-end host; the main lifecycle occurs between rodents and their predators. Adult worms live, mate, and lay noninfective unembryonated eggs in rodent livers. Embryogenesis occurs only after contact with the soil in two settings: 1) the rodent is eaten by the predator and the unembryonated eggs are released in the predator's feces or 2) carcass disintegration after natural death of the rodent. Humans incidentally ingest the infective embryonated eggs by soil to mouth transmission. They hatch in the human intestine and the larvae migrate through the portal vein into the liver where they mature into adult worms. In the liver, the cycle continues with the adult worms mating and laying eggs. This elicits intense inflammation with systemic symptoms.1 In the index case, we hypothesize that the toddler with pica would have come in contact with soil in the vicinity of the stray cats. This soil would have initially contained the feline feces with unembryonated eggs that later underwent embryogenesis. The triad of fever, hepatomegaly, and eosinophilia is the hallmark and characteristic liver histology clinches the diagnosis. Duration of anthelminthic therapy should be guided by AEC response.2,3

References

1. Wright K.A. Observation on the life cycle of Capillaria hepatica with a description of the adult. Can J Zool. 1961;39:167-82.

2. Berger T. Degrémont A. Gebbers J.O. et al. Hepatic capillariasis in a 1-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;149:333-633.

3. Choe G. Lee H.S. Seo J.K. et al. Hepatic capillariasis: first case report in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:610-25.

Capillaria hepatica infection

The liver parenchyma shows spindle-shaped eosinophilic eggs surrounded by eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates and epithelioid granuloma (original magnification ×200). Figure B shows spindle-shaped eosinophilic eggs with shells, radial striations, and visible polar body, containing granular eosinophilic debris (original magnification ×1000), consistent with Capillaria hepatica. Figure C reveals crescent-shaped, degenerated adult worms of C. hepatica showing longitudinal bacillary bands, vacuolated intestine, and convoluted gonads surrounded by intense eosinophilic inflammation in liver parenchyma (original magnification ×400). The outer cuticle is not appreciated because the worms are degenerated.

A review of history revealed that the child played with stray cats and had pica. He was given 10 mg/kg of oral albendazole for 16 weeks and 1 mg/kg of oral prednisolone for the first 2 weeks to prevent paradoxical inflammatory response. Thereafter, prednisolone was tapered and stopped. Pyrexia, liver size, AEC, and liver enzymes normalized at 24 hours, 72 hours, 4 months, and 5 months, respectively. At 12 months of follow-up, the child is asymptomatic.

Capillaria hepatica is a rare nematodal invasive parasitosis where humans are the dead-end host; the main lifecycle occurs between rodents and their predators. Adult worms live, mate, and lay noninfective unembryonated eggs in rodent livers. Embryogenesis occurs only after contact with the soil in two settings: 1) the rodent is eaten by the predator and the unembryonated eggs are released in the predator's feces or 2) carcass disintegration after natural death of the rodent. Humans incidentally ingest the infective embryonated eggs by soil to mouth transmission. They hatch in the human intestine and the larvae migrate through the portal vein into the liver where they mature into adult worms. In the liver, the cycle continues with the adult worms mating and laying eggs. This elicits intense inflammation with systemic symptoms.1 In the index case, we hypothesize that the toddler with pica would have come in contact with soil in the vicinity of the stray cats. This soil would have initially contained the feline feces with unembryonated eggs that later underwent embryogenesis. The triad of fever, hepatomegaly, and eosinophilia is the hallmark and characteristic liver histology clinches the diagnosis. Duration of anthelminthic therapy should be guided by AEC response.2,3

References

1. Wright K.A. Observation on the life cycle of Capillaria hepatica with a description of the adult. Can J Zool. 1961;39:167-82.

2. Berger T. Degrémont A. Gebbers J.O. et al. Hepatic capillariasis in a 1-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;149:333-633.

3. Choe G. Lee H.S. Seo J.K. et al. Hepatic capillariasis: first case report in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:610-25.

A 15-month-old, previously thriving boy from western urban India was brought in with high-grade pyrexia of unknown origin for the last 45 days. He had received multiple courses of antibiotics and antimalarials elsewhere without any response. Appetite and general activity were preserved. Examination revealed mild pallor, significant nontender soft hepatomegaly (liver span of 14 cm) without splenomegaly or peripheral lymphadenopathy. Investigations showed a hemoglobin of 9 g/dL, microcytic hypochromic smear, total leukocyte count of 48,900/mm3, neutrophils at 16%, lymphocytes at 23%, eosinophils at 58%, absolute eosinophil count of 28,362/mm3, platelet count of 490,000/mm3, bilirubin of 0.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase of 203 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase of 179 IU/L, total protein of 9.3 g/dL, albumin of 3.6 g/dL, alkaline phosphatase of 203 IU/L, and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase of 107 IU/L. Ultrasound examination and computed tomography scans of abdomen showed no focal lesions or abscesses. A bone marrow biopsy revealed an increase in eosinophils and its precursors. Echocardiography, retroviral serology, and multiple blood and urine cultures were unyielding. Liver biopsy was performed for diagnosis (Figures A-C).

What is your diagnosis? - July 2020

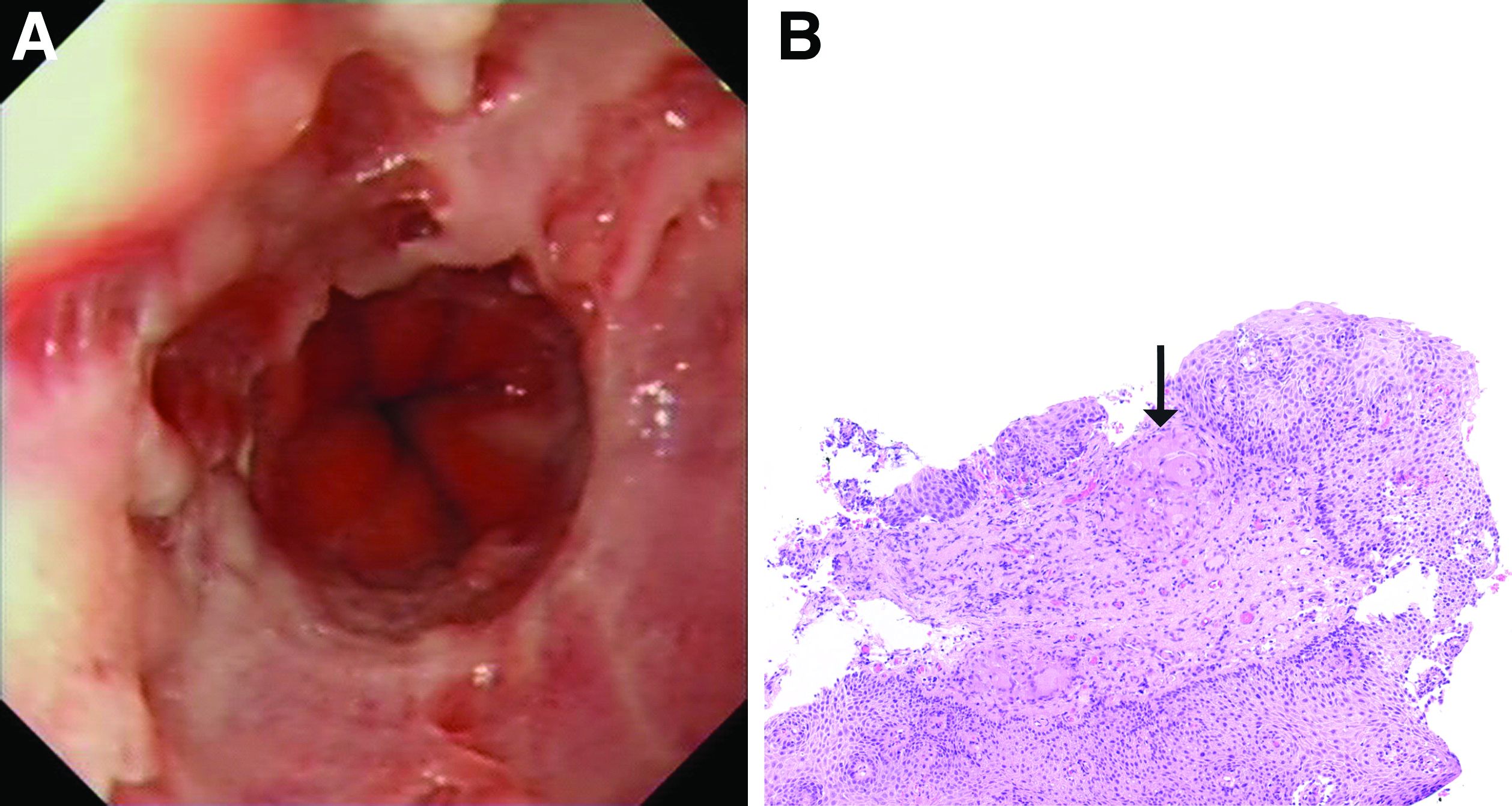

Fibroepithelial polyp of the hypopharynx

Our patient underwent an upper endoscopy to evaluate symptoms of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease and was found to have a large hiatal hernia. Upon careful endoscopic withdrawal, the polyp was briefly visualized as it was pulled back into the oropharynx. The patient was referred for flexible laryngoscopy that confirmed a polypoid mass involving the right lateral piriform wall. She subsequently underwent direct laryngoscopy with harmonic scalpel-assisted excision of the lesion leading to resolution of her symptom of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The surgical specimen measured 3 × 1.4 × 0.4 cm. Pathology demonstrated benign overlying squamous mucosa with submucosa composed of bland spindle cells and fat, consistent with a benign fibroepithelial polyp (Figure C, original magnification × 100; stain: hematoxylin and eosin).

Fibroepithelial polyps are rare benign lesions of the hypopharynx and proximal esophagus that can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.1 Larger hypopharyngeal polyps have been associated with aspiration and airway compromise.1 Owing to their proximal location, these lesions are more readily identified under flexible laryngoscopy, but can also be observed with esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Cross-sectional imaging of the neck can be considered for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia and a normal video-swallow study. Although the underlying pathogenesis remains unclear, inflammation or infection may play a role, especially in smokers.2 The rate of recurrence after resection is low.1

Further evaluation for her symptomatic hiatal hernia was performed and the patient ultimately underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with wedge gastroplasty, leading to improvement in her symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This case illustrates that, although esophagogastroduodenoscopy is not considered the first step in the evaluation of patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, a careful examination can sometimes reveal the diagnosis.

References

1. Caceres M, et al. Large pedunculated polyps originating in the esophagus and hypopharynx. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:393-6.

2. Maskey AP, et al. Endobronchial fibroepithelial polyp. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:313-4.

ginews@gastro.org

Fibroepithelial polyp of the hypopharynx

Our patient underwent an upper endoscopy to evaluate symptoms of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease and was found to have a large hiatal hernia. Upon careful endoscopic withdrawal, the polyp was briefly visualized as it was pulled back into the oropharynx. The patient was referred for flexible laryngoscopy that confirmed a polypoid mass involving the right lateral piriform wall. She subsequently underwent direct laryngoscopy with harmonic scalpel-assisted excision of the lesion leading to resolution of her symptom of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The surgical specimen measured 3 × 1.4 × 0.4 cm. Pathology demonstrated benign overlying squamous mucosa with submucosa composed of bland spindle cells and fat, consistent with a benign fibroepithelial polyp (Figure C, original magnification × 100; stain: hematoxylin and eosin).

Fibroepithelial polyps are rare benign lesions of the hypopharynx and proximal esophagus that can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.1 Larger hypopharyngeal polyps have been associated with aspiration and airway compromise.1 Owing to their proximal location, these lesions are more readily identified under flexible laryngoscopy, but can also be observed with esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Cross-sectional imaging of the neck can be considered for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia and a normal video-swallow study. Although the underlying pathogenesis remains unclear, inflammation or infection may play a role, especially in smokers.2 The rate of recurrence after resection is low.1

Further evaluation for her symptomatic hiatal hernia was performed and the patient ultimately underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with wedge gastroplasty, leading to improvement in her symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This case illustrates that, although esophagogastroduodenoscopy is not considered the first step in the evaluation of patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, a careful examination can sometimes reveal the diagnosis.

References

1. Caceres M, et al. Large pedunculated polyps originating in the esophagus and hypopharynx. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:393-6.

2. Maskey AP, et al. Endobronchial fibroepithelial polyp. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:313-4.

ginews@gastro.org

Fibroepithelial polyp of the hypopharynx

Our patient underwent an upper endoscopy to evaluate symptoms of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease and was found to have a large hiatal hernia. Upon careful endoscopic withdrawal, the polyp was briefly visualized as it was pulled back into the oropharynx. The patient was referred for flexible laryngoscopy that confirmed a polypoid mass involving the right lateral piriform wall. She subsequently underwent direct laryngoscopy with harmonic scalpel-assisted excision of the lesion leading to resolution of her symptom of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The surgical specimen measured 3 × 1.4 × 0.4 cm. Pathology demonstrated benign overlying squamous mucosa with submucosa composed of bland spindle cells and fat, consistent with a benign fibroepithelial polyp (Figure C, original magnification × 100; stain: hematoxylin and eosin).

Fibroepithelial polyps are rare benign lesions of the hypopharynx and proximal esophagus that can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.1 Larger hypopharyngeal polyps have been associated with aspiration and airway compromise.1 Owing to their proximal location, these lesions are more readily identified under flexible laryngoscopy, but can also be observed with esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Cross-sectional imaging of the neck can be considered for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia and a normal video-swallow study. Although the underlying pathogenesis remains unclear, inflammation or infection may play a role, especially in smokers.2 The rate of recurrence after resection is low.1

Further evaluation for her symptomatic hiatal hernia was performed and the patient ultimately underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with wedge gastroplasty, leading to improvement in her symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This case illustrates that, although esophagogastroduodenoscopy is not considered the first step in the evaluation of patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, a careful examination can sometimes reveal the diagnosis.

References

1. Caceres M, et al. Large pedunculated polyps originating in the esophagus and hypopharynx. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:393-6.

2. Maskey AP, et al. Endobronchial fibroepithelial polyp. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:313-4.

ginews@gastro.org

What is your diagnosis? - June 2020

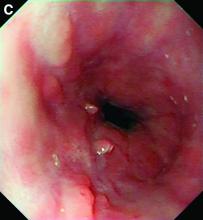

Phlegmonous gastritis

The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 6.6 g/d) and a proton pump inhibitor (esomeprazole 80 mg/d). Within a few days, her clinical status improved and abdominal ultrasound examination documented regression of the gastric wall thickening. Laboratory screening for predisposing factors such as diabetes mellitus, infection with human immunodeficiency virus, or immunoglobulin deficiency were negative and there was no clinical evidence of Crohn’s disease. Antibiotic treatment was stopped after 2 weeks. Six months later, follow-up gastroscopy was performed confirming complete resolution of the inflammatory changes in the stomach.

Phlegmonous gastritis is a rare but potentially life-threatening bacterial infection of the gastric wall. Since its first description in 1862, about 500 cases have been reported worldwide. Whereas the original reports dating back to the preantibiotic area suggest very high mortality rates in the range of 90%, phlegmonous gastritis still represents a life-threatening condition.1,2 In about one-half of the cases, acquired immunodeficiency states such as diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus, or alcoholism are identified as predisposing factors. In addition, gastric biopsies may herald the development of phlegmonous gastritis. Streptococcus spp. account for the majority of the cases, which can be isolated in about 70% of patients.1 Other organisms such as Staphylococcus spp., Escherichia coli Haemophilus influenzae, and Proteus or Clostridium spp. have been described as pathogens associated with this uncommon condition. Affected patients typically present with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomitus, hematemesis, or diarrhea. In light of the devastating natural course of phlegmonous gastritis, timely preemptive administration of broad spectrum antibiotic along with a high index of suspicion are paramount. A computed tomography scan and transabdominal ultrasound examination are useful as initial tests, whereas endoscopic ultrasound examination typically demonstrates a diffusely thickened, hypoechogenic submucosal wall layer that is not commonly found in patients with other submucosal lesions, such as carcinoid or leiomyoma. The diagnosis can be confirmed by endoscopic forceps biopsy provided that sufficient submucosal tissue is included.1 Surgery should only be considered for cases refractory to conservative treatment.

References

1. Kim G, Ward J, Henessey B, et al. Phlegmonous gastritis: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:168-74.

2. Starr A, Wilson J. Phlegmonous gastritis. Ann Surg. 1957;145:88-93.

ginews@gastro.org

Phlegmonous gastritis

The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 6.6 g/d) and a proton pump inhibitor (esomeprazole 80 mg/d). Within a few days, her clinical status improved and abdominal ultrasound examination documented regression of the gastric wall thickening. Laboratory screening for predisposing factors such as diabetes mellitus, infection with human immunodeficiency virus, or immunoglobulin deficiency were negative and there was no clinical evidence of Crohn’s disease. Antibiotic treatment was stopped after 2 weeks. Six months later, follow-up gastroscopy was performed confirming complete resolution of the inflammatory changes in the stomach.

Phlegmonous gastritis is a rare but potentially life-threatening bacterial infection of the gastric wall. Since its first description in 1862, about 500 cases have been reported worldwide. Whereas the original reports dating back to the preantibiotic area suggest very high mortality rates in the range of 90%, phlegmonous gastritis still represents a life-threatening condition.1,2 In about one-half of the cases, acquired immunodeficiency states such as diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus, or alcoholism are identified as predisposing factors. In addition, gastric biopsies may herald the development of phlegmonous gastritis. Streptococcus spp. account for the majority of the cases, which can be isolated in about 70% of patients.1 Other organisms such as Staphylococcus spp., Escherichia coli Haemophilus influenzae, and Proteus or Clostridium spp. have been described as pathogens associated with this uncommon condition. Affected patients typically present with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomitus, hematemesis, or diarrhea. In light of the devastating natural course of phlegmonous gastritis, timely preemptive administration of broad spectrum antibiotic along with a high index of suspicion are paramount. A computed tomography scan and transabdominal ultrasound examination are useful as initial tests, whereas endoscopic ultrasound examination typically demonstrates a diffusely thickened, hypoechogenic submucosal wall layer that is not commonly found in patients with other submucosal lesions, such as carcinoid or leiomyoma. The diagnosis can be confirmed by endoscopic forceps biopsy provided that sufficient submucosal tissue is included.1 Surgery should only be considered for cases refractory to conservative treatment.

References

1. Kim G, Ward J, Henessey B, et al. Phlegmonous gastritis: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:168-74.

2. Starr A, Wilson J. Phlegmonous gastritis. Ann Surg. 1957;145:88-93.

ginews@gastro.org

Phlegmonous gastritis

The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 6.6 g/d) and a proton pump inhibitor (esomeprazole 80 mg/d). Within a few days, her clinical status improved and abdominal ultrasound examination documented regression of the gastric wall thickening. Laboratory screening for predisposing factors such as diabetes mellitus, infection with human immunodeficiency virus, or immunoglobulin deficiency were negative and there was no clinical evidence of Crohn’s disease. Antibiotic treatment was stopped after 2 weeks. Six months later, follow-up gastroscopy was performed confirming complete resolution of the inflammatory changes in the stomach.

Phlegmonous gastritis is a rare but potentially life-threatening bacterial infection of the gastric wall. Since its first description in 1862, about 500 cases have been reported worldwide. Whereas the original reports dating back to the preantibiotic area suggest very high mortality rates in the range of 90%, phlegmonous gastritis still represents a life-threatening condition.1,2 In about one-half of the cases, acquired immunodeficiency states such as diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus, or alcoholism are identified as predisposing factors. In addition, gastric biopsies may herald the development of phlegmonous gastritis. Streptococcus spp. account for the majority of the cases, which can be isolated in about 70% of patients.1 Other organisms such as Staphylococcus spp., Escherichia coli Haemophilus influenzae, and Proteus or Clostridium spp. have been described as pathogens associated with this uncommon condition. Affected patients typically present with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomitus, hematemesis, or diarrhea. In light of the devastating natural course of phlegmonous gastritis, timely preemptive administration of broad spectrum antibiotic along with a high index of suspicion are paramount. A computed tomography scan and transabdominal ultrasound examination are useful as initial tests, whereas endoscopic ultrasound examination typically demonstrates a diffusely thickened, hypoechogenic submucosal wall layer that is not commonly found in patients with other submucosal lesions, such as carcinoid or leiomyoma. The diagnosis can be confirmed by endoscopic forceps biopsy provided that sufficient submucosal tissue is included.1 Surgery should only be considered for cases refractory to conservative treatment.

References

1. Kim G, Ward J, Henessey B, et al. Phlegmonous gastritis: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:168-74.

2. Starr A, Wilson J. Phlegmonous gastritis. Ann Surg. 1957;145:88-93.

ginews@gastro.org

A previously healthy 41-year-old woman presented with upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever for 4 days. On admission, the patient was febrile (40.1°C); her blood pressure, heart rate, and peripheral oxygen saturation were normal. Laboratory findings were notable for a C-reactive protein of 190 mg/L (reference range, less than 5 mg/L) along with a white cell count of 21,600/mm3 (reference range, 4,500-10,500/mm3). Liver enzymes, pancreatic lipase, and bilirubin were within normal limits. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed wall thickening of the gastric antrum (Figure A).

Gastroscopy showed a heavily distorted gastric antrum with a fistula (Figure B, C). Consecutively, endoscopic ultrasound examination was performed, confirming circumferential thickening of the antral wall up to 20 mm with inhomogeneous hypoechogenic areas within the submucosa (Figure D). Deep endoscopic forceps biopsies were obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed extensive infiltration of the mucosa and submucosa by neutrophils (Figure E, F) and microbial cultures were positive for Streptococcus spp. (S. pyogenes, viridans group streptococci) and Rothia mucilaginosa.

What is your diagnosis? - March 2020

Squamous metaplasia

Weight regain can accompany re-emergence of obesity-related comorbidities and, thus, early intervention is important. Although diet, exercise, and behavior modifications are fundamental, they can have limited efficacy. Thus, endoscopic management is important, with specific evaluation for gastrogastric fistulae, pouch dilation, and GJA dilation, all of which can be successfully intervened upon endoscopically. For GJA dilation in particular, APC has been used with promising results.1