User login

Answer: esophageal Crohn’s disease.

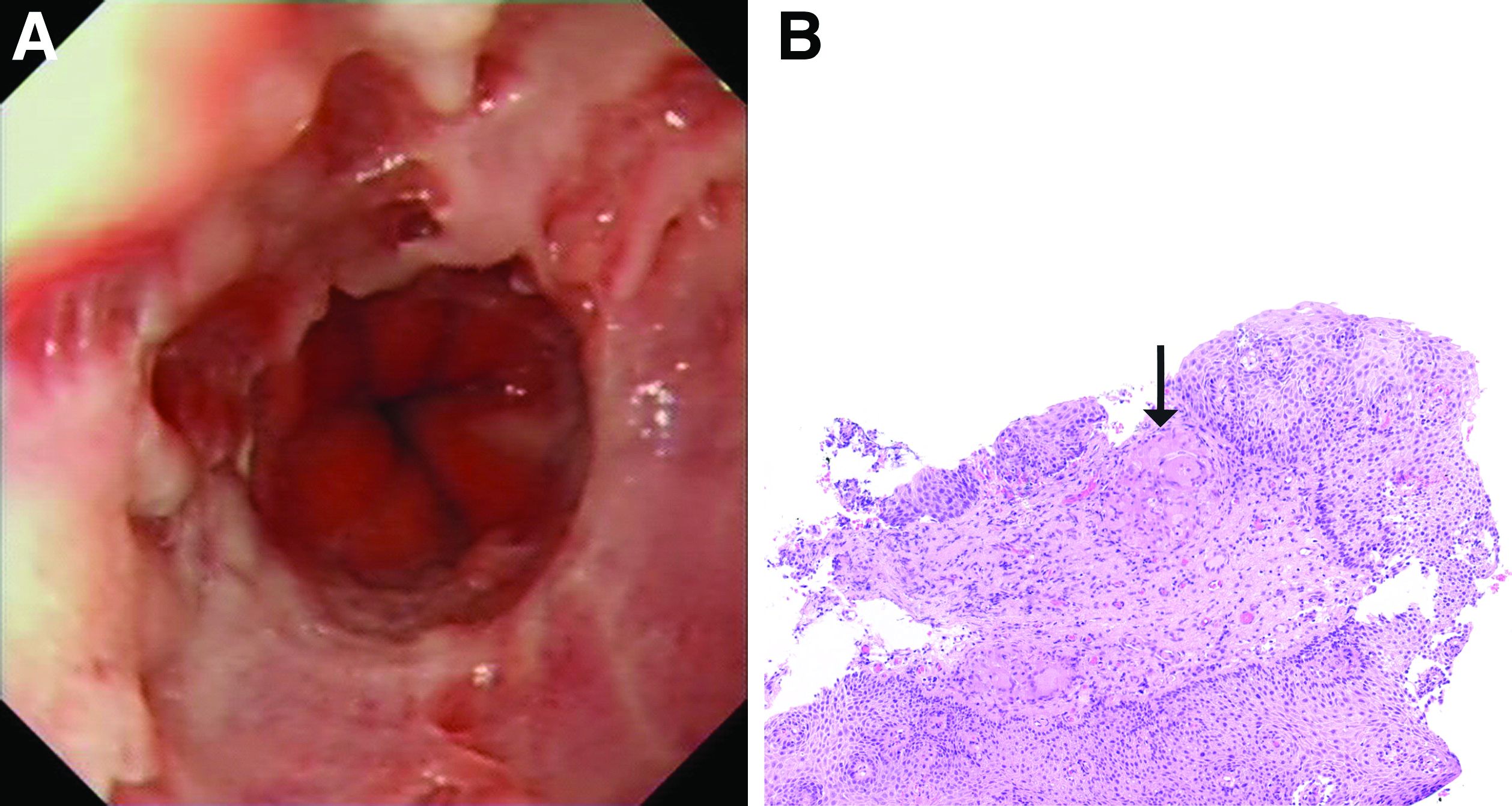

The esophageal biopsies demonstrate severe chronic inflammation of the subepithelial tissue with marked lymphocytic infiltration and the presence of granulomas containing multinucleate giant cells (Figure B, arrow). Given his immunosuppression with azathioprine, stains for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and mycobacterial and fungal organisms were performed and returned negative.

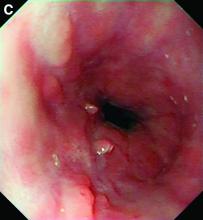

A diagnosis of esophageal Crohn’s disease was made, and adalimumab was recommenced. A rapid and dramatic clinical improvement was observed, with complete resolution of his symptoms. Adalimumab trough levels were checked and found to be therapeutic (9 mcg/mL). Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy at 6 months showed healing of the esophageal ulceration, with residual scarring and the presence of two postinflammatory polyps (Figure C). The histopathology was consistent with quiescent Crohn’s disease.

Recognition of this very rare manifestation of Crohn’s is challenging but important so that appropriate treatment is not delayed. It is both unexplained and unusual for Crohn’s disease to flare in a new gastrointestinal location. Moreover, although accurate adult prevalence data for esophageal Crohn’s are scarce, retrospective data suggest it is present in just 0.2% of Crohn’s disease patients.1 By contrast, gastroesophageal reflux disease prevalence is between 18% and 28% of the total population in North America. Esophageal Crohn’s commonly leads to nonspecific symptoms that resemble gastroesophageal reflux disease, and as for acid reflux, the mid and distal esophagus are the most common sites of involvement. In keeping with the behavior of luminal Crohn’s disease, progression from inflammation to stenosis (causing marked dysphagia) or perforation (leading to fistula formation) may occur.2 Histopathology typically demonstrates chronic inflammation, although noncaseating granulomas are seen in the minority (7%-39%) of patients.3 Multiple deep biopsies are recommended to improve diagnostic yield,3 and our case demonstrates the value of repeat endoscopic evaluation.

Unsurprisingly given its rarity, there are no systematic data on optimal treatment. Acid suppression therapy may provide symptomatic benefit but does not treat the underlying inflammatory process. Oral prednisolone, topical budesonide, and immunomodulators including thiopurines have been used in case series, but biological therapy (typically anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy) is likely to be required for severe disease.2,3 There are no data on the use of more novel biologics. Critically, almost all reported cases of esophageal Crohn’s disease have concomitant intestinal disease, and the presence of upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s predicts a more severe disease phenotype, supporting the use of more aggressive medical therapy in this instance.3

References

1. Decker GA et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):113-9.

2. De Felice KM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Sep;21(9):2106-13.

3. Laube R et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;33(2):355-64.

Answer: esophageal Crohn’s disease.

The esophageal biopsies demonstrate severe chronic inflammation of the subepithelial tissue with marked lymphocytic infiltration and the presence of granulomas containing multinucleate giant cells (Figure B, arrow). Given his immunosuppression with azathioprine, stains for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and mycobacterial and fungal organisms were performed and returned negative.

A diagnosis of esophageal Crohn’s disease was made, and adalimumab was recommenced. A rapid and dramatic clinical improvement was observed, with complete resolution of his symptoms. Adalimumab trough levels were checked and found to be therapeutic (9 mcg/mL). Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy at 6 months showed healing of the esophageal ulceration, with residual scarring and the presence of two postinflammatory polyps (Figure C). The histopathology was consistent with quiescent Crohn’s disease.

Recognition of this very rare manifestation of Crohn’s is challenging but important so that appropriate treatment is not delayed. It is both unexplained and unusual for Crohn’s disease to flare in a new gastrointestinal location. Moreover, although accurate adult prevalence data for esophageal Crohn’s are scarce, retrospective data suggest it is present in just 0.2% of Crohn’s disease patients.1 By contrast, gastroesophageal reflux disease prevalence is between 18% and 28% of the total population in North America. Esophageal Crohn’s commonly leads to nonspecific symptoms that resemble gastroesophageal reflux disease, and as for acid reflux, the mid and distal esophagus are the most common sites of involvement. In keeping with the behavior of luminal Crohn’s disease, progression from inflammation to stenosis (causing marked dysphagia) or perforation (leading to fistula formation) may occur.2 Histopathology typically demonstrates chronic inflammation, although noncaseating granulomas are seen in the minority (7%-39%) of patients.3 Multiple deep biopsies are recommended to improve diagnostic yield,3 and our case demonstrates the value of repeat endoscopic evaluation.

Unsurprisingly given its rarity, there are no systematic data on optimal treatment. Acid suppression therapy may provide symptomatic benefit but does not treat the underlying inflammatory process. Oral prednisolone, topical budesonide, and immunomodulators including thiopurines have been used in case series, but biological therapy (typically anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy) is likely to be required for severe disease.2,3 There are no data on the use of more novel biologics. Critically, almost all reported cases of esophageal Crohn’s disease have concomitant intestinal disease, and the presence of upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s predicts a more severe disease phenotype, supporting the use of more aggressive medical therapy in this instance.3

References

1. Decker GA et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):113-9.

2. De Felice KM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Sep;21(9):2106-13.

3. Laube R et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;33(2):355-64.

Answer: esophageal Crohn’s disease.

The esophageal biopsies demonstrate severe chronic inflammation of the subepithelial tissue with marked lymphocytic infiltration and the presence of granulomas containing multinucleate giant cells (Figure B, arrow). Given his immunosuppression with azathioprine, stains for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and mycobacterial and fungal organisms were performed and returned negative.

A diagnosis of esophageal Crohn’s disease was made, and adalimumab was recommenced. A rapid and dramatic clinical improvement was observed, with complete resolution of his symptoms. Adalimumab trough levels were checked and found to be therapeutic (9 mcg/mL). Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy at 6 months showed healing of the esophageal ulceration, with residual scarring and the presence of two postinflammatory polyps (Figure C). The histopathology was consistent with quiescent Crohn’s disease.

Recognition of this very rare manifestation of Crohn’s is challenging but important so that appropriate treatment is not delayed. It is both unexplained and unusual for Crohn’s disease to flare in a new gastrointestinal location. Moreover, although accurate adult prevalence data for esophageal Crohn’s are scarce, retrospective data suggest it is present in just 0.2% of Crohn’s disease patients.1 By contrast, gastroesophageal reflux disease prevalence is between 18% and 28% of the total population in North America. Esophageal Crohn’s commonly leads to nonspecific symptoms that resemble gastroesophageal reflux disease, and as for acid reflux, the mid and distal esophagus are the most common sites of involvement. In keeping with the behavior of luminal Crohn’s disease, progression from inflammation to stenosis (causing marked dysphagia) or perforation (leading to fistula formation) may occur.2 Histopathology typically demonstrates chronic inflammation, although noncaseating granulomas are seen in the minority (7%-39%) of patients.3 Multiple deep biopsies are recommended to improve diagnostic yield,3 and our case demonstrates the value of repeat endoscopic evaluation.

Unsurprisingly given its rarity, there are no systematic data on optimal treatment. Acid suppression therapy may provide symptomatic benefit but does not treat the underlying inflammatory process. Oral prednisolone, topical budesonide, and immunomodulators including thiopurines have been used in case series, but biological therapy (typically anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy) is likely to be required for severe disease.2,3 There are no data on the use of more novel biologics. Critically, almost all reported cases of esophageal Crohn’s disease have concomitant intestinal disease, and the presence of upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s predicts a more severe disease phenotype, supporting the use of more aggressive medical therapy in this instance.3

References

1. Decker GA et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):113-9.

2. De Felice KM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Sep;21(9):2106-13.

3. Laube R et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;33(2):355-64.

A 49-year-old man presented with symptoms of retrosternal discomfort and mild dysphagia to solids. He had a 30-year history of ileocolonic Crohn's disease requiring previous resections of the ileum and sigmoid colon. Clinical remission had been achieved with adalimumab and azathioprine combination therapy, with the subsequent decision to de-escalate to maintenance with azathioprine monotherapy after consideration of the risks and benefits of dual immunosuppression. After 5 years of azathioprine monotherapy, complete endoscopic remission was reconfirmed at a recent ileocolonoscopy.

To investigate his upper gastrointestinal symptoms he underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy that demonstrated severe esophagitis (Los Angeles grade D) of the lower esophagus with biopsies confirming apparent reflux esophagitis. However, his symptoms worsened despite a course of high dose proton pump inhibitor, and a repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed. This demonstrated deep longitudinal ulcers and inflammation of the lower two-thirds of the esophagus (Figure A). Biopsies were sent for histopathologic analysis (Figure B).