User login

Worsening agitation and hallucinations: Could it be PTSD?

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

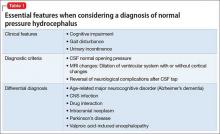

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

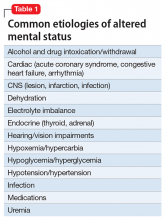

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

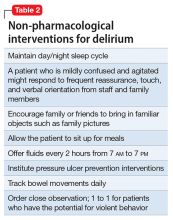

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

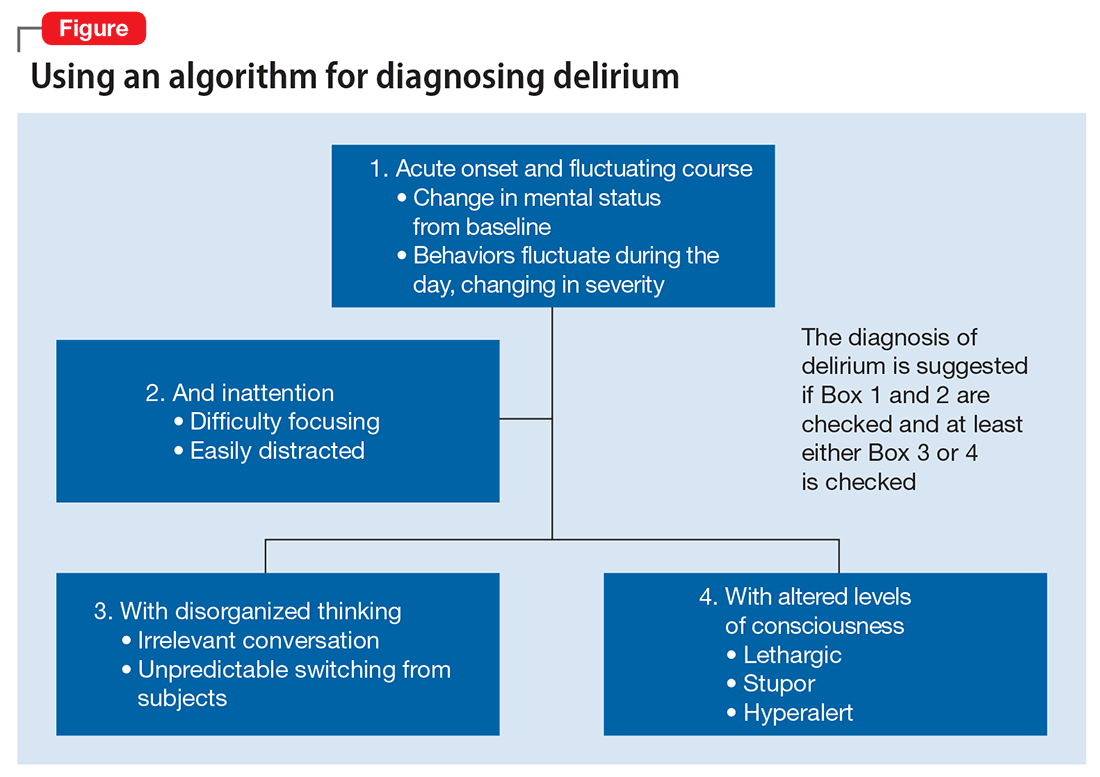

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

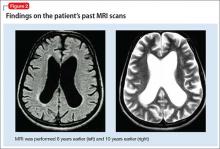

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

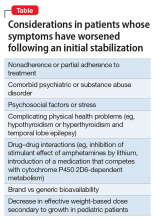

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

Suicidal and asking for money for food

CASE Suicidal and hungry

Mr. L, age 59, attempts suicide by taking approximately 20 acetaminophen tablets of unknown dosage. He immediately comes to the emergency department where blood work reveals a 4-hour acetaminophen level of 94.8 μg/mL (therapeutic range, 10 to 30 μg/mL; toxic range, >150 μg/mL); administration of N-acetylcysteine is unnecessary. Mr. L is admitted to general medical services for monitoring and is transferred to our unit for psychiatric evaluation and management.

During our initial interview, Mr. L, who has a developmental disability, is grossly oriented and generally cooperative, reporting depressed mood with an irritable affect. He is preoccupied with having limited funds and repeatedly states he is worried that he can’t buy food, but says that the hospital could help by providing for him. Mr. L states that his depressed mood is directly related to his financial situation and, that if he had more money, he would not be suicidal. He cites worsening visual impairment that requires surgery as an additional stressor.

On several occasions, Mr. L states that the only way to help him is to give him $600 so that he can buy food and pay for medical treatment. Mr. L says he does not feel supported by his family, despite having a sister who lives nearby.

What would you include in the differential diagnosis for Mr. L?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) depression secondary to a medical condition

c) neurocognitive disorder

d) adjustment disorder with depressive features

e) factitious disorder

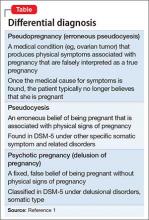

The authors’ observations

Our differential diagnosis included MDD, adjustment disorder, neurocognitive disorder, and factitious disorder. He did not meet criteria for MDD because he did not have excessive guilt, loss of interest, change in sleep or appetite, psychomotor dysregulation, or change in energy level. Although suicidal behavior could indicate MDD, the fact that he immediately walked to the hospital after taking an excessive amount of acetaminophen suggests that he did not want to die. Further, he attributed his suicidal thoughts to environmental stressors. Similarly, we ruled out adjustment disorder because he had no reported or observed changes in mood or anxiety. Although financial difficulties might have overwhelmed his limited coping abilities, he took too much acetaminophen to ensure that he was hospitalized. His motivation for seeking hospitalization ruled out factitious disorder. Mr. L has a developmental disability, but information obtained from collateral sources ruled out an acute change to cognitive functioning.

HISTORY Repeated admissions

Mr. L has a history of a psychiatric hospitalization 3 weeks prior to this admission. He presented to an emergency department stating that his blood glucose was low. Mr. L was noted to be confused and anxious and said he was convinced he was going to die. At that time, his thought content was hyper-religious and he claimed he could hear the devil. Mr. L was hospitalized and started on low-dosage risperidone. At discharge, he declined referral for outpatient mental health treatment because he denied having a mental illness. However, he was amenable to follow up at a wellness clinic.

Mr. L has worked at a local supermarket for 19 years and has lived independently throughout his adult life. After he returned to the community, he was repeatedly absent from work, which further exacerbated his financial strain. He attended a follow-up outpatient appointment but reported, “They didn’t help me,” although it was unclear what he meant.

Between admissions to our hospital, Mr. L had 2 visits to an emergency department, the first time saying he felt depressed and the second reporting he attempted suicide by taking 5 acetaminophen tablets. On both occasions he requested placement in a residential facility but was discharged home after an initial assessment. Emergency room records indicated that Mr. L stated, “If you cannot give me money for food, then there is no use and I would rather die.”

What is the most likely DSM-5 diagnosis for Mr. L?

a) schizophrenia

b) malingering

c) brief psychotic disorder

d) dependent personality disorder

The authors’ observations

Malingering in DSM-5 is defined as the “intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives.”1 These external incentives include financial compensation, avoiding military duties, evading criminal charges, and avoiding work, and are collectively considered as secondary gain. Although not considered a diagnosis in the strictest sense, clinicians must differentiate malingering from other psychiatric disorders. In the literature, case reports describe patients who feigned an array of symptoms including those of posttraumatic stress disorder, paraphilias, cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, and psychosis.2-5

In Mr. L’s case, malingering presented as suicidal behavior with an inadvertently high fatality risk. Notably, Mr. L came to an emergency room a few days before this admission after swallowing 5 acetaminophen tablets in a suicide attempt, which did not lead to a medical or psychiatric hospitalization. In an attempt to ensure admission, Mr. L then took a potentially lethal dose of 20 acetaminophen tablets. In our assessment and according to his statements, the primary motivation for the suicide attempt was to obtain reliable food and housing. Mr. L’s developmental disability might have contributed to a relative lack of understanding of the consequences of his actions. In addition, poor overall communication and coping skills led to an exaggerated response to psychosocial stressors.

Malingering and suicide attempts

Few studies have investigated malingering in regards to suicide and other psychiatric emergencies. In a study of 227 consecutive psychiatric emergencies assessed for evidence of malingering, 13% were thought to be feigned or exaggerated.6 Interestingly, the most commonly reported secondary gain was food and shelter, similar to Mr. L. This study did not report the types of psychiatric emergencies, therefore suicidal actions associated with malingering could not be evaluated.

In another study, 40 patients hospitalized for suicidal ideation (n = 29, 72%) or suicidal gestures (n = 11, 28%) in a large, urban tertiary care center were evaluated for malingering by anonymous report of feigned or exaggerated symptoms.7 Most of these patients were diagnosed with a mood disorder (28%) and/or an adjustment disorder (53%). Four (10%) admitted to malingering. Among the malingerers, reasons for feigning illness included:

- wanting to be hospitalized

- wanting to make someone angry or feel sorry

- gaining access to detoxification programs

- getting treatment for emotional problems.

Interestingly, an analysis of demographic factors associated with malingering reveals an association with suicide attempts but not persistent suicidal ideations. This could be because of selection bias; patients who reported a suicide attempt might be more likely to be hospitalized.

A follow-up study8 evaluated 50 additional consecutive psychiatric inpatients admitted to the same tertiary care hospital for suicide risk. Unlike the previous study, a larger proportion of these patients had made a suicide attempt (n = 21, 42%) and a greater number had made a previous suicide attempt (n = 33, 66%). Primary mood disorders comprised most of the psychiatric diagnoses (n = 28, 56%). In this study, the exact nature of the suicide gestures was not documented, leaving open the question of lethality of the attempts. These studies do not suggest that those who malinger are not at risk for suicide, only that these patients tend to exaggerate the severity of their ideations or behaviors.

OUTCOME Reluctantly discharged

We contact Mr. L’s siblings, who offer to provide temporary housing and financial support and assist him with medical needs. This abated Mr. L’s suicidal ideation; however, he wishes to remain in the hospital with the goals of obtaining eyeglasses and dentures. We explain that psychiatric hospitalization is no longer indicated and he is discharged.

Which of the following is the most effective management strategy for malingering?

a) direct confrontation of the malingering patient

b) immediate discharge once malingering is identified

c) evaluation for possible comorbid psychiatric conditions

d) neuropsychiatric consultation

The authors’ observations

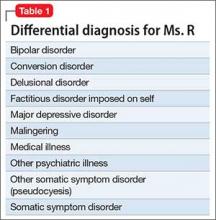

The challenges of treating patients who malinger include clinician uncertainty in making the diagnosis and high variability in occurrence across settings (Table 1). Current estimates indicate that 4% to 8% of medical and psychiatric cases not involved in litigation or compensation have an element of feigned symptoms.3,9 The rate could be higher in specific circumstances such as medicolegal disputes and criminal cases.10

The societal impact of malingering is significant. Therefore, identifying these patients is an important clinical intervention that can have a wide impact.11 However, it is also important to acknowledge that genuine psychiatric illness could be comorbid with malingering. Although differentiating a patient’s true from feigned symptoms can be difficult, it is critical to carefully evaluate the patient in order to provide the best treatment.

It seems that physicians can detect malingering, but documentation often is not provided. In the Rissmiller et al study,7 all 4 cases of malingering were identified retrospectively by study psychiatrists; however, none of their medical records included documentation of malingering, a finding also reported in the Yates et al study.6 Also concerning, the clinicians suspected malingering in some patients who were not feigning symptoms, suggesting that a relatively high threshold is necessary for making the diagnosis.

How to help patients who malinger

Identifying malingering in patients with obvious secondary gain is important to prevent exposure to potential adverse effects of medication and unnecessary use of medical resources. In addition, obtaining collateral information, records from previous admissions or outpatient treatment, and psychological testing adds to the body of evidence suggesting malingering. We also recommend a comprehensive psychosocial evaluation to identify the presence of secondary gain.

Management of malingering (Table 2) includes building a strong therapeutic alliance, exploring reasons for feigning symptoms, open discussion of inciting external factors such as interpersonal conflict or difficulties at work, and/or confrontation.10 In addition, supportive psychotherapy might help strengthen coping mechanisms and problem solving strategies, thereby removing the need for secondary gain.12 Additionally, face-saving mechanisms that allow the patient to discard their feigned symptoms, or enable the person to alter his (her) history, could be to his benefit. Lastly, and importantly, clinicians should focus efforts on ruling out or effectively treating comorbid psychiatric conditions.

From a risk management standpoint, include all available data to support the malingering diagnosis in your progress notes and discharge summaries. A clinician seeking to discharge a patient suspected of malingering who is still endorsing suicidal or homicidal intent will benefit from administrative review, including legal counsel to mitigate risk, and be more confident discharging somebody assessed to be malingering.

We recognize that certain patients could trigger countertransference reactions that impel clinicians to take on a significant caretaking role. Patients skillful at deception could manifest a desire to rescue or save them. In these instances, clinicians should examine why and how these feelings have come about, particularly if there is evidence that the individual could be attempting to use the interaction to achieve secondary gain. Awareness of these feelings could help with the diagnostic formulation. Moreover, a clinician who has such strong feelings might be tempted to abet a patient in achieving the secondary gain, or protect him (her) from the natural consequences of individual’s deception (eg, not discharging a hospitalized patient). This is counter-therapeutic and reinforces maladaptive behaviors and coping processes.13

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Fedoroff JP, Hanson A, McGuire M, et al. Simulated paraphilias: a preliminary study of patients who imitate or exaggerate paraphilic symptoms and behaviors. J Forensic Sci. 1992;37(3):902-911.

3. Mittenberg W, Patton C, Canyock EM, et al. Base rates of malingering and symptom exaggeration. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24(8):1094-1102.

4. Waite S, Geddes A. Malingered psychosis leading to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14(4):419-421.

5. Hall RC, Hall RC. Malingering of PTSD: forensic and diagnostic consideration, characteristics of malingerers and clinical presentations. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(6):525-535.

6. Yates BD, Nordquist CR, Shultz-Ross RA. Feigned psychiatric symptoms in the emergency room. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(9):998-1000.

7. Rissmiller DJ, Wayslow A, Madison H, et al. Prevalence of malingering in inpatient suicidal ideators and attempters. Crisis. 1998;19(2):62-66.

8. Rissmiller D, Steer RA, Friedman M, et al. Prevalence of malingering in suicidal psychiatric inpatients: a replication. Psychol Rep. 1999;84(3 pt 1):726-730.

9. Sullivan K, Lange RT, Dawes S. Methods of detecting malingering and estimated symptom exaggeration base rates in Australia. Journal of Forensic Neuropsychology. 2007;4(4):49-70.

10. Bass C, Halligan P. Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422-1432.

11. Chafetz M, Underhill J. Estimated costs of malingered disability. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28(7):633-639.

12. Peebles R, Sabel

13. Malone RD, Lange CL. A clinical approach to the malingering patient. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2007;35(1):13-21.

CASE Suicidal and hungry

Mr. L, age 59, attempts suicide by taking approximately 20 acetaminophen tablets of unknown dosage. He immediately comes to the emergency department where blood work reveals a 4-hour acetaminophen level of 94.8 μg/mL (therapeutic range, 10 to 30 μg/mL; toxic range, >150 μg/mL); administration of N-acetylcysteine is unnecessary. Mr. L is admitted to general medical services for monitoring and is transferred to our unit for psychiatric evaluation and management.

During our initial interview, Mr. L, who has a developmental disability, is grossly oriented and generally cooperative, reporting depressed mood with an irritable affect. He is preoccupied with having limited funds and repeatedly states he is worried that he can’t buy food, but says that the hospital could help by providing for him. Mr. L states that his depressed mood is directly related to his financial situation and, that if he had more money, he would not be suicidal. He cites worsening visual impairment that requires surgery as an additional stressor.

On several occasions, Mr. L states that the only way to help him is to give him $600 so that he can buy food and pay for medical treatment. Mr. L says he does not feel supported by his family, despite having a sister who lives nearby.

What would you include in the differential diagnosis for Mr. L?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) depression secondary to a medical condition

c) neurocognitive disorder

d) adjustment disorder with depressive features

e) factitious disorder

The authors’ observations

Our differential diagnosis included MDD, adjustment disorder, neurocognitive disorder, and factitious disorder. He did not meet criteria for MDD because he did not have excessive guilt, loss of interest, change in sleep or appetite, psychomotor dysregulation, or change in energy level. Although suicidal behavior could indicate MDD, the fact that he immediately walked to the hospital after taking an excessive amount of acetaminophen suggests that he did not want to die. Further, he attributed his suicidal thoughts to environmental stressors. Similarly, we ruled out adjustment disorder because he had no reported or observed changes in mood or anxiety. Although financial difficulties might have overwhelmed his limited coping abilities, he took too much acetaminophen to ensure that he was hospitalized. His motivation for seeking hospitalization ruled out factitious disorder. Mr. L has a developmental disability, but information obtained from collateral sources ruled out an acute change to cognitive functioning.

HISTORY Repeated admissions

Mr. L has a history of a psychiatric hospitalization 3 weeks prior to this admission. He presented to an emergency department stating that his blood glucose was low. Mr. L was noted to be confused and anxious and said he was convinced he was going to die. At that time, his thought content was hyper-religious and he claimed he could hear the devil. Mr. L was hospitalized and started on low-dosage risperidone. At discharge, he declined referral for outpatient mental health treatment because he denied having a mental illness. However, he was amenable to follow up at a wellness clinic.

Mr. L has worked at a local supermarket for 19 years and has lived independently throughout his adult life. After he returned to the community, he was repeatedly absent from work, which further exacerbated his financial strain. He attended a follow-up outpatient appointment but reported, “They didn’t help me,” although it was unclear what he meant.

Between admissions to our hospital, Mr. L had 2 visits to an emergency department, the first time saying he felt depressed and the second reporting he attempted suicide by taking 5 acetaminophen tablets. On both occasions he requested placement in a residential facility but was discharged home after an initial assessment. Emergency room records indicated that Mr. L stated, “If you cannot give me money for food, then there is no use and I would rather die.”

What is the most likely DSM-5 diagnosis for Mr. L?

a) schizophrenia

b) malingering

c) brief psychotic disorder

d) dependent personality disorder

The authors’ observations

Malingering in DSM-5 is defined as the “intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives.”1 These external incentives include financial compensation, avoiding military duties, evading criminal charges, and avoiding work, and are collectively considered as secondary gain. Although not considered a diagnosis in the strictest sense, clinicians must differentiate malingering from other psychiatric disorders. In the literature, case reports describe patients who feigned an array of symptoms including those of posttraumatic stress disorder, paraphilias, cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, and psychosis.2-5

In Mr. L’s case, malingering presented as suicidal behavior with an inadvertently high fatality risk. Notably, Mr. L came to an emergency room a few days before this admission after swallowing 5 acetaminophen tablets in a suicide attempt, which did not lead to a medical or psychiatric hospitalization. In an attempt to ensure admission, Mr. L then took a potentially lethal dose of 20 acetaminophen tablets. In our assessment and according to his statements, the primary motivation for the suicide attempt was to obtain reliable food and housing. Mr. L’s developmental disability might have contributed to a relative lack of understanding of the consequences of his actions. In addition, poor overall communication and coping skills led to an exaggerated response to psychosocial stressors.

Malingering and suicide attempts

Few studies have investigated malingering in regards to suicide and other psychiatric emergencies. In a study of 227 consecutive psychiatric emergencies assessed for evidence of malingering, 13% were thought to be feigned or exaggerated.6 Interestingly, the most commonly reported secondary gain was food and shelter, similar to Mr. L. This study did not report the types of psychiatric emergencies, therefore suicidal actions associated with malingering could not be evaluated.

In another study, 40 patients hospitalized for suicidal ideation (n = 29, 72%) or suicidal gestures (n = 11, 28%) in a large, urban tertiary care center were evaluated for malingering by anonymous report of feigned or exaggerated symptoms.7 Most of these patients were diagnosed with a mood disorder (28%) and/or an adjustment disorder (53%). Four (10%) admitted to malingering. Among the malingerers, reasons for feigning illness included:

- wanting to be hospitalized

- wanting to make someone angry or feel sorry

- gaining access to detoxification programs

- getting treatment for emotional problems.

Interestingly, an analysis of demographic factors associated with malingering reveals an association with suicide attempts but not persistent suicidal ideations. This could be because of selection bias; patients who reported a suicide attempt might be more likely to be hospitalized.

A follow-up study8 evaluated 50 additional consecutive psychiatric inpatients admitted to the same tertiary care hospital for suicide risk. Unlike the previous study, a larger proportion of these patients had made a suicide attempt (n = 21, 42%) and a greater number had made a previous suicide attempt (n = 33, 66%). Primary mood disorders comprised most of the psychiatric diagnoses (n = 28, 56%). In this study, the exact nature of the suicide gestures was not documented, leaving open the question of lethality of the attempts. These studies do not suggest that those who malinger are not at risk for suicide, only that these patients tend to exaggerate the severity of their ideations or behaviors.

OUTCOME Reluctantly discharged

We contact Mr. L’s siblings, who offer to provide temporary housing and financial support and assist him with medical needs. This abated Mr. L’s suicidal ideation; however, he wishes to remain in the hospital with the goals of obtaining eyeglasses and dentures. We explain that psychiatric hospitalization is no longer indicated and he is discharged.

Which of the following is the most effective management strategy for malingering?

a) direct confrontation of the malingering patient

b) immediate discharge once malingering is identified

c) evaluation for possible comorbid psychiatric conditions

d) neuropsychiatric consultation

The authors’ observations

The challenges of treating patients who malinger include clinician uncertainty in making the diagnosis and high variability in occurrence across settings (Table 1). Current estimates indicate that 4% to 8% of medical and psychiatric cases not involved in litigation or compensation have an element of feigned symptoms.3,9 The rate could be higher in specific circumstances such as medicolegal disputes and criminal cases.10

The societal impact of malingering is significant. Therefore, identifying these patients is an important clinical intervention that can have a wide impact.11 However, it is also important to acknowledge that genuine psychiatric illness could be comorbid with malingering. Although differentiating a patient’s true from feigned symptoms can be difficult, it is critical to carefully evaluate the patient in order to provide the best treatment.

It seems that physicians can detect malingering, but documentation often is not provided. In the Rissmiller et al study,7 all 4 cases of malingering were identified retrospectively by study psychiatrists; however, none of their medical records included documentation of malingering, a finding also reported in the Yates et al study.6 Also concerning, the clinicians suspected malingering in some patients who were not feigning symptoms, suggesting that a relatively high threshold is necessary for making the diagnosis.

How to help patients who malinger

Identifying malingering in patients with obvious secondary gain is important to prevent exposure to potential adverse effects of medication and unnecessary use of medical resources. In addition, obtaining collateral information, records from previous admissions or outpatient treatment, and psychological testing adds to the body of evidence suggesting malingering. We also recommend a comprehensive psychosocial evaluation to identify the presence of secondary gain.

Management of malingering (Table 2) includes building a strong therapeutic alliance, exploring reasons for feigning symptoms, open discussion of inciting external factors such as interpersonal conflict or difficulties at work, and/or confrontation.10 In addition, supportive psychotherapy might help strengthen coping mechanisms and problem solving strategies, thereby removing the need for secondary gain.12 Additionally, face-saving mechanisms that allow the patient to discard their feigned symptoms, or enable the person to alter his (her) history, could be to his benefit. Lastly, and importantly, clinicians should focus efforts on ruling out or effectively treating comorbid psychiatric conditions.

From a risk management standpoint, include all available data to support the malingering diagnosis in your progress notes and discharge summaries. A clinician seeking to discharge a patient suspected of malingering who is still endorsing suicidal or homicidal intent will benefit from administrative review, including legal counsel to mitigate risk, and be more confident discharging somebody assessed to be malingering.

We recognize that certain patients could trigger countertransference reactions that impel clinicians to take on a significant caretaking role. Patients skillful at deception could manifest a desire to rescue or save them. In these instances, clinicians should examine why and how these feelings have come about, particularly if there is evidence that the individual could be attempting to use the interaction to achieve secondary gain. Awareness of these feelings could help with the diagnostic formulation. Moreover, a clinician who has such strong feelings might be tempted to abet a patient in achieving the secondary gain, or protect him (her) from the natural consequences of individual’s deception (eg, not discharging a hospitalized patient). This is counter-therapeutic and reinforces maladaptive behaviors and coping processes.13

CASE Suicidal and hungry

Mr. L, age 59, attempts suicide by taking approximately 20 acetaminophen tablets of unknown dosage. He immediately comes to the emergency department where blood work reveals a 4-hour acetaminophen level of 94.8 μg/mL (therapeutic range, 10 to 30 μg/mL; toxic range, >150 μg/mL); administration of N-acetylcysteine is unnecessary. Mr. L is admitted to general medical services for monitoring and is transferred to our unit for psychiatric evaluation and management.

During our initial interview, Mr. L, who has a developmental disability, is grossly oriented and generally cooperative, reporting depressed mood with an irritable affect. He is preoccupied with having limited funds and repeatedly states he is worried that he can’t buy food, but says that the hospital could help by providing for him. Mr. L states that his depressed mood is directly related to his financial situation and, that if he had more money, he would not be suicidal. He cites worsening visual impairment that requires surgery as an additional stressor.

On several occasions, Mr. L states that the only way to help him is to give him $600 so that he can buy food and pay for medical treatment. Mr. L says he does not feel supported by his family, despite having a sister who lives nearby.

What would you include in the differential diagnosis for Mr. L?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) depression secondary to a medical condition

c) neurocognitive disorder

d) adjustment disorder with depressive features

e) factitious disorder

The authors’ observations

Our differential diagnosis included MDD, adjustment disorder, neurocognitive disorder, and factitious disorder. He did not meet criteria for MDD because he did not have excessive guilt, loss of interest, change in sleep or appetite, psychomotor dysregulation, or change in energy level. Although suicidal behavior could indicate MDD, the fact that he immediately walked to the hospital after taking an excessive amount of acetaminophen suggests that he did not want to die. Further, he attributed his suicidal thoughts to environmental stressors. Similarly, we ruled out adjustment disorder because he had no reported or observed changes in mood or anxiety. Although financial difficulties might have overwhelmed his limited coping abilities, he took too much acetaminophen to ensure that he was hospitalized. His motivation for seeking hospitalization ruled out factitious disorder. Mr. L has a developmental disability, but information obtained from collateral sources ruled out an acute change to cognitive functioning.

HISTORY Repeated admissions

Mr. L has a history of a psychiatric hospitalization 3 weeks prior to this admission. He presented to an emergency department stating that his blood glucose was low. Mr. L was noted to be confused and anxious and said he was convinced he was going to die. At that time, his thought content was hyper-religious and he claimed he could hear the devil. Mr. L was hospitalized and started on low-dosage risperidone. At discharge, he declined referral for outpatient mental health treatment because he denied having a mental illness. However, he was amenable to follow up at a wellness clinic.

Mr. L has worked at a local supermarket for 19 years and has lived independently throughout his adult life. After he returned to the community, he was repeatedly absent from work, which further exacerbated his financial strain. He attended a follow-up outpatient appointment but reported, “They didn’t help me,” although it was unclear what he meant.

Between admissions to our hospital, Mr. L had 2 visits to an emergency department, the first time saying he felt depressed and the second reporting he attempted suicide by taking 5 acetaminophen tablets. On both occasions he requested placement in a residential facility but was discharged home after an initial assessment. Emergency room records indicated that Mr. L stated, “If you cannot give me money for food, then there is no use and I would rather die.”

What is the most likely DSM-5 diagnosis for Mr. L?

a) schizophrenia

b) malingering

c) brief psychotic disorder

d) dependent personality disorder

The authors’ observations

Malingering in DSM-5 is defined as the “intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives.”1 These external incentives include financial compensation, avoiding military duties, evading criminal charges, and avoiding work, and are collectively considered as secondary gain. Although not considered a diagnosis in the strictest sense, clinicians must differentiate malingering from other psychiatric disorders. In the literature, case reports describe patients who feigned an array of symptoms including those of posttraumatic stress disorder, paraphilias, cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, and psychosis.2-5

In Mr. L’s case, malingering presented as suicidal behavior with an inadvertently high fatality risk. Notably, Mr. L came to an emergency room a few days before this admission after swallowing 5 acetaminophen tablets in a suicide attempt, which did not lead to a medical or psychiatric hospitalization. In an attempt to ensure admission, Mr. L then took a potentially lethal dose of 20 acetaminophen tablets. In our assessment and according to his statements, the primary motivation for the suicide attempt was to obtain reliable food and housing. Mr. L’s developmental disability might have contributed to a relative lack of understanding of the consequences of his actions. In addition, poor overall communication and coping skills led to an exaggerated response to psychosocial stressors.

Malingering and suicide attempts

Few studies have investigated malingering in regards to suicide and other psychiatric emergencies. In a study of 227 consecutive psychiatric emergencies assessed for evidence of malingering, 13% were thought to be feigned or exaggerated.6 Interestingly, the most commonly reported secondary gain was food and shelter, similar to Mr. L. This study did not report the types of psychiatric emergencies, therefore suicidal actions associated with malingering could not be evaluated.

In another study, 40 patients hospitalized for suicidal ideation (n = 29, 72%) or suicidal gestures (n = 11, 28%) in a large, urban tertiary care center were evaluated for malingering by anonymous report of feigned or exaggerated symptoms.7 Most of these patients were diagnosed with a mood disorder (28%) and/or an adjustment disorder (53%). Four (10%) admitted to malingering. Among the malingerers, reasons for feigning illness included:

- wanting to be hospitalized

- wanting to make someone angry or feel sorry

- gaining access to detoxification programs

- getting treatment for emotional problems.

Interestingly, an analysis of demographic factors associated with malingering reveals an association with suicide attempts but not persistent suicidal ideations. This could be because of selection bias; patients who reported a suicide attempt might be more likely to be hospitalized.

A follow-up study8 evaluated 50 additional consecutive psychiatric inpatients admitted to the same tertiary care hospital for suicide risk. Unlike the previous study, a larger proportion of these patients had made a suicide attempt (n = 21, 42%) and a greater number had made a previous suicide attempt (n = 33, 66%). Primary mood disorders comprised most of the psychiatric diagnoses (n = 28, 56%). In this study, the exact nature of the suicide gestures was not documented, leaving open the question of lethality of the attempts. These studies do not suggest that those who malinger are not at risk for suicide, only that these patients tend to exaggerate the severity of their ideations or behaviors.

OUTCOME Reluctantly discharged

We contact Mr. L’s siblings, who offer to provide temporary housing and financial support and assist him with medical needs. This abated Mr. L’s suicidal ideation; however, he wishes to remain in the hospital with the goals of obtaining eyeglasses and dentures. We explain that psychiatric hospitalization is no longer indicated and he is discharged.

Which of the following is the most effective management strategy for malingering?

a) direct confrontation of the malingering patient

b) immediate discharge once malingering is identified

c) evaluation for possible comorbid psychiatric conditions

d) neuropsychiatric consultation

The authors’ observations

The challenges of treating patients who malinger include clinician uncertainty in making the diagnosis and high variability in occurrence across settings (Table 1). Current estimates indicate that 4% to 8% of medical and psychiatric cases not involved in litigation or compensation have an element of feigned symptoms.3,9 The rate could be higher in specific circumstances such as medicolegal disputes and criminal cases.10

The societal impact of malingering is significant. Therefore, identifying these patients is an important clinical intervention that can have a wide impact.11 However, it is also important to acknowledge that genuine psychiatric illness could be comorbid with malingering. Although differentiating a patient’s true from feigned symptoms can be difficult, it is critical to carefully evaluate the patient in order to provide the best treatment.

It seems that physicians can detect malingering, but documentation often is not provided. In the Rissmiller et al study,7 all 4 cases of malingering were identified retrospectively by study psychiatrists; however, none of their medical records included documentation of malingering, a finding also reported in the Yates et al study.6 Also concerning, the clinicians suspected malingering in some patients who were not feigning symptoms, suggesting that a relatively high threshold is necessary for making the diagnosis.

How to help patients who malinger

Identifying malingering in patients with obvious secondary gain is important to prevent exposure to potential adverse effects of medication and unnecessary use of medical resources. In addition, obtaining collateral information, records from previous admissions or outpatient treatment, and psychological testing adds to the body of evidence suggesting malingering. We also recommend a comprehensive psychosocial evaluation to identify the presence of secondary gain.