User login

CKD Awareness in Hospitalized Patients

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects over 13% of the US population and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.[1] However, only 10% of individuals with CKD are aware of their diagnoses.[2] Even in those with stage 5 CKD, only 60% of individuals are aware of their CKD.[3] To our knowledge, no work has examined CKD awareness in a hospitalized patient population.

Patient awareness of their CKD diagnosis is important because progression of kidney disease can be slowed by patient self‐management of diabetes and hypertension.[4] Patient awareness of CKD may also increase acceptance of preend‐stage renal disease (ESRD) patient education and nephrology referral, which have been shown to delay CKD progression and improve clinical status at dialysis initiation.[5] However, only 60% of patients with advanced CKD have visited a nephrologist in the past year or have seen a nephrologist prior to dialysis initiation.[1]

The hospital is an important site for patient education and linkage to outpatient care for patients with CKD.[6] The hospital serves high‐risk patients who may not be well connected to outpatient care or who have lesswell‐controlled disease.[6, 7] Thus, hospitalization represents an opportunity to identify existing CKD and to use a multidisciplinary approach to preventative care, patient education, and patient‐provider planning for renal replacement therapy needs. In our cross‐sectional study in an urban, minority‐serving hospital, we sought to determine what patient factors were associated with hospitalized patients correctly self‐identifying as having CKD.

METHODS

Subjects and Data

We used data from the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project, a study of hospitalized patient outcomes.[8] Within 48 hours of hospitalization, all general medicine patients or their proxies are approached to enroll. During one‐on‐one inpatient interviews, a trained research assistant obtains demographic, health status, and healthcare utilization information. Participants consent for study staff to review their medical records. More than 80% of general medicine patients enroll.

We obtained data on 1234 general medicine patients discharged between January 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013 with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) code for chronic kidney disease (ICD‐9 codes 585.0585.5, 585.9) in their first 20 admission diagnoses. These codes are highly specific for CKD but have lower sensitivity.[9] We excluded all patients with a history of transplant (996.81, V42.0, n=90) or ESRD (585.6, n=416). We excluded repeat admissions during the study period (n=138). Our final sample included 590 unique patients with ICD‐9 diagnosis of CKD without ESRD.

Demographic, Clinical, and Health Service Utilization Characteristics

Our outcome was CKD awareness, the patient's correct self‐report of kidney disease. Patients selected their chronic medical conditions from a list read to them and were specifically asked if they had kidney problems. Demographic characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education were also obtained. Healthcare utilization variables included how often the patient saw their primary medical care provider in the past year and whether patients had a prior hospitalization in the last year.

Health status variables such as mental status, diabetes, hypertension, and CKD stage were also assessed. Mental status was quantified using the telephone version of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE), scored from 1 to 22.10 We defined diabetes as ICD‐9 codes 250.0250.00, and hypertension as ICD‐9 codes 401.0, 401.9, 403, 405.09, 405.19, 405.91, 405.99, or by patient self‐report. CKD stage was based on the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from the medical record using Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines.[11] We used the mode of the eGFR to calculate the appropriate CKD stage for those with more than 1 eGFR value from the hospitalization (576/590, 98%). The eGFR was calculated by the modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation: (GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)=175 (Screatinine)1.154 (Age)0.203 (0.742 if female) x (1.212 if African American)) recommended by the National Kidney Disease Education Program.[12]

Analysis

We used logistic regression to analyze the influence of the demographic, clinical, and healthcare utilization covariates on the likelihood of a patient reporting kidney problems. For the multivariate analysis, we sequentially added variables in a step‐wise fashion. We adjusted for (1) demographic factors: gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education; (2) eGFR‐calculated CKD stage and comorbidities: diabetes, hypertension, and mental status; and (3) healthcare utilization in the last 12 months: any hospitalizations and the number of visits to a health provider.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Bivariable Association With Patient CKD Self‐Report

Table 1 shows demographic, clinical, and health service use characteristics for 590 patients with ICD‐9 coded CKD. In the bivariable model in Table 1, age, race, marital status and comorbidities, were associated with patient self‐report of CKD. Patients older than 80 years with physician‐identified CKD through ICD‐9 coding had 57% lower odds of reporting CKD than their younger counterparts. Patients of other races (nonwhite, non‐African American), married patients, and those with CKD stages 4 and 5 were much more likely to correctly self‐report CKD. Patients with higher MMSE score, diabetes, or hypertension had greater odds of CKD self‐report (all P<0.05).

| Total, N=590 | Bivariable Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Multivariable With Stepwise Addition (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1, Demographic Factors | Model 2, Plus CKD Stage and Other Comorbidities | Model 3, Plus Health Service Use | |||

| |||||

| Female | 312 (52.98%) | 1.21 (0.85‐1.70) | 1.64 (1.09‐2.47)* | 1.28 (0.79‐2.06) | 1.36 (0.75‐2.48) |

| Age, y | |||||

| Below 54 | 138 (23.4%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 5466 | 150 (24.4%) | 0.96 (0.59‐1.54) | 0.95 (0.56‐1.59) | 1.01 (0.56‐1.81) | 0.83 (0.41‐1.68) |

| 6779 | 161 (27.3%) | 0.77 (0.48‐1.23) | 0.67 (0.39‐1.15) | 0.66 (0.35‐1.23) | 0.72(0.34‐1.52) |

| Above 80 | 141 (23.9%) | 0.43 (0.26‐0.74) | 0.32 (0.17‐0.60) | 0.42 (0.20‐0.91)* | 0.37 (0.15‐0.93)* |

| Race | |||||

| African American | 449 (82.1%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| White | 75 (13.7%) | 1.47 (0.89‐2.42) | 1.53 (0.86‐2.71) | 1.56 (0.78‐3.12) | 1.08 (0.47‐2.49) |

| Other | 23 (4.2%) | 3.62 (1.53‐8.54) | 5.29 (1.78‐15.73) | 6.19 (1.72‐22.29) | 11.63 (1.80‐75.21)* |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic is reference group) | 21 (4.0%) | 0.97 (0.38‐2.44) | 0.43 (0.13‐1.45) | 0.71 (0.16‐3.09) | 0.46 (0.06‐3.57) |

| Married | 171 (32.6%) | 1.49 (1.03‐2.18)* | 1.32 (0.85‐2.04) | 1.20 (0.73‐1.98) | 1.77 (0.94‐3.33) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 128 (25.2%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| High school grad/some college | 296 (58.2%) | 1.05 (0.68‐1.63) | 0.93 (0.58‐1.49) | 0.95 (0.54‐1.67) | 0.85 (0.42‐1.72) |

| College grad or higher | 85 (16.7%) | 1.13 (0.64‐2.01) | 0.96 (0.51‐1.78) | 1.07 (0.51‐2.23) | 0.69 (0.27‐1.77) |

| CKD stage (eGFR calculated, mode) | |||||

| 12 | 115 (20.0%) | 0.55 (0.32‐0.95)* | 0.52 (0.27‐1.01) | 0.28 (0.11‐0.69) | |

| 3 | 300 (52.1%) | REF | REF | REF | |

| 4 | 112 (19.4%) | 2.43 (1.55‐3.81) | 2.69 (1.52‐4.76) | 3.07 (1.56‐6.07) | |

| 5 | 49 (8.5%) | 4.50 (2.39‐8.48) | 3.94 (1.81‐8.56) | 5.16 (1.85‐14.41) | |

| Diabetes (ICD‐9 coded or self‐report)‖ | 292 (49.5%) | 1.52 (1.07‐2.15)* | 1.54 (0.97‐2.45) | 1.26 (0.71‐2.26) | |

| Hypertension (ICD‐9 coded or self‐report) | 436 (73.9%) | 3.36 (2.09‐5.41) | 1.53 (0.80‐2.90) | 1.26 (0.57‐2.81) | |

| Mini‐Mental State Exam score# | 19.7 (2.5) | 1.13 (1.03‐1.23) | 1.09 (0.98‐1.22) | 1.22 (1.06‐1.42) | |

| Hospitalized in last 12 months | 253 (46.9%) | 1.50 (1.05‐2.13)* | 1.12 (0.65‐1.95) | ||

| No. of visits to health provider | |||||

| Once/year or less | 80 (18.4%) | REF | REF | ||

| 23 times/year | 58 (13.3%) | 0.80 (0.40‐1.60) | 0.44 (0.17‐1.16) | ||

| 4+ times/year | 298 (68.4%) | 0.60 (0.36‐0.99)* | 0.38 (0.19‐0.74) | ||

Multivariable Associations With Patient CKD Self‐Report

Age, race, and CKD stage remained consistently associated with CKD self‐report, although the magnitude of the effects (odds ratios [ORs]) varied across models (Table 1). Across all the models, patients older than 80 years were still significantly less likely than younger patients to self‐report CKD (ORs ranging from 0.32 to 0.42, all P<0.05). Patients classified as being of other race were found to have a 5.29 to 11.63 greater odds of CKD self‐report than African American patients (all P<0.05).

Patients with CKD stage 4 and 5 were more likely to self‐report than patients with CKD stage 3 (ORs ranging from 2.693.07 for stage 4 and 3.945.16 for stage 5, P<0.05). In the final model, every unit increase in MMSE score increased the odds of CKD self‐report by 22%. In addition, patients who saw their health provider 4 or more times per year were 62% less likely to self‐report CKD than patients who saw their provider 1 or fewer times per year (OR: 0.38, P<0.05).

A large proportion of patients (68.6%) were CKD unspecified by ICD‐9 codes, and only 27% of the unspecified group reported having CKD (Table 2). Examining the eGFR CKD stage of the CKD unspecified group showed that 22.8% were eGFR‐determined CKD stage 1 to 2, 57.1% were CKD stage 3, 14.8% were CKD stage 4, and 5.3% were CKD stage 5. Patients had 2 to 3 times greater odds of correct CKD self‐report if physicians had correctly identified their CKD stage (bivariable OR: 2.42, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.57‐3.72, multivariable OR: 3.22, 95% CI: 0.99‐10.46) (analysis not shown).

| CKD Stage* | Physician (ICD‐9) Coded | eGFR Calculated | eGFR Coded With ICD‐9 Correct |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Unspecified | 110 (27.2%) | ||

| 12 | 5 (31.2%) | 20 (17.4%) | 0 |

| 3 | 25 (27.2%) | 83 (27.7%) | 17 (29.8%) |

| 4 | 40 (63.5%) | 54 (48.2%) | 25 (69.4%) |

| 5 | 11 (78.6%) | 31 (63.3%) | 10 (83.3%) |

DISCUSSION

Although prior work has examined CKD awareness in the general population and in high‐risk cohorts,[2, 3, 13] this is the first study examining CKD awareness in an urban, underserved hospitalized population. We found that overall patients' CKD awareness was low (32%), but increased as high as 63% for CKD stage 5, even after controlling for patient demographic, clinical characteristics, and healthcare use. Our overall rate of CKD awareness was higher than prior studies overall and at lower CKD stages.[2, 3, 13] Our work is consistent with prior literature that shows increasing CKD awareness with advancing CKD stage.[2, 3, 13]

Older patients (>80 years) had lower awareness of CKD. Older patients are more likely to have a near normal creatinine, despite a markedly reduced eGFR, so their CKD may go unnoticed.[14] Even with appropriate recognition, providers may also feel like their CKD is unlikely to progress to ESRD, given its stability and/or their competing risk of death.[15] Finally, older hospitalized patients may also be less likely to report a CKD diagnosis due to difficulty in recall due to denial, dementia, or delirium.

One limitation is that our case‐finding for CKD was physician ICD‐9 coding, which is highly specific but not sensitive.[9] The majority of patients with physician‐identified CKD were CKD unspecified, perhaps due to poor coding, physician underdocumentation, or physician under‐recognition of CKD stage. Although only 27% of the CKD unspecified group correctly self‐identified as having CKD, over 75% were found to be CKD stage 3 or higher, which should trigger additional monitoring or care based on guidelines.[10] In addition, despite statistical significance, we may not be able to make meaningful inferences about our small other group (nonwhite, non‐African American). Our sample was from 1 hospitalan urban, academic, tertiary care center with a large proportion of African American patientswhich may limit generalizability. The multivariable model will need to be tested in other populations for reproducibility.

Our study significantly contributes to the literature by examining patient awareness of CKD in a high‐risk, urban, hospitalized minority population. Other study strengths include use of basic demographic information, as well as survey and laboratory data for a richer examination of the associations between patient factors and CKD awareness.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalized patients with CKD have a low CKD awareness. Patient awareness of their CKD is increased with physician documentation of CKD severity. Patient awareness of their CKD must be coupled with provider awareness and CKD documentation to link patients to multidisciplinary CKD education and care to slow CKD progression and reduce associated cardiovascular and metabolic complications. Further work is needed across hospitals to determineand improveCKD awareness among both patients and providers.

Disclosures

Dr. Saunders was supported by Pilot and Feasibility Funding from the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 DK092949). Dr. Chin was supported by NIDDK K24 DK071933. Dr. Meltzer was supported by NIA T35 AG029795. Dr. Saunders had full access to all of the study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. An abstract of this article was presented at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada in March 2014 and at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in San Diego, California in April 2014. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- United States Renal Data System. Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End‐Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2012.

- , , , et al. Chronic kidney disease awareness among individuals with clinical markers of kidney dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Neph. 2011;6(8):1838–1844.

- , , , et al. Comparison of CKD awareness in a screening population using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study and CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD‐EPI) equations. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3 suppl 2):S17–S23.

- , , , et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(3):646–661.

- , , , et al. Multidisciplinary predialysis education decreases the incidence of dialysis and reduces mortality—a controlled cohort study based on the NKFDOQI guidelines. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(11):3426–3433.

- , , . Pre‐dialysis hospital use and late referrals in incident dialysis patients in England: a retrospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(1):124–129.

- , , , et al. Do hospitals that provide heart failure patient education prior to discharge also promote continuity of care? A report from OPTIMIZE‐HF. J Card Fail. 2006;12(6 suppl):S111.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , , et al. Failure of ICD‐9‐CM codes to identify patients with comorbid chronic kidney disease in diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(2):564–580.

- , , , . Validation of a telephone version of the mini‐mental state examination. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(7):697–702.

- National Kidney Foundation. Kidney disease outcomes quality initiative guidelines 2002. Available at: http://www2.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_ckd/toc.htm. Accessed October 9, 2014.

- , , , , , . A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–470.

- , , , et al. Prevalence and awareness of CKD among African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(2):238–247.

- , , , , , . Magnitude of underascertainment of impaired kidney function in older adults with normal serum creatinine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(6):816–823.

- , , , et al. Prediction, Progression, and Outcomes of Chronic Kidney Disease in Older Adults. J Am Soc Neph. 2009;20(6):1199–1209.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects over 13% of the US population and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.[1] However, only 10% of individuals with CKD are aware of their diagnoses.[2] Even in those with stage 5 CKD, only 60% of individuals are aware of their CKD.[3] To our knowledge, no work has examined CKD awareness in a hospitalized patient population.

Patient awareness of their CKD diagnosis is important because progression of kidney disease can be slowed by patient self‐management of diabetes and hypertension.[4] Patient awareness of CKD may also increase acceptance of preend‐stage renal disease (ESRD) patient education and nephrology referral, which have been shown to delay CKD progression and improve clinical status at dialysis initiation.[5] However, only 60% of patients with advanced CKD have visited a nephrologist in the past year or have seen a nephrologist prior to dialysis initiation.[1]

The hospital is an important site for patient education and linkage to outpatient care for patients with CKD.[6] The hospital serves high‐risk patients who may not be well connected to outpatient care or who have lesswell‐controlled disease.[6, 7] Thus, hospitalization represents an opportunity to identify existing CKD and to use a multidisciplinary approach to preventative care, patient education, and patient‐provider planning for renal replacement therapy needs. In our cross‐sectional study in an urban, minority‐serving hospital, we sought to determine what patient factors were associated with hospitalized patients correctly self‐identifying as having CKD.

METHODS

Subjects and Data

We used data from the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project, a study of hospitalized patient outcomes.[8] Within 48 hours of hospitalization, all general medicine patients or their proxies are approached to enroll. During one‐on‐one inpatient interviews, a trained research assistant obtains demographic, health status, and healthcare utilization information. Participants consent for study staff to review their medical records. More than 80% of general medicine patients enroll.

We obtained data on 1234 general medicine patients discharged between January 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013 with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) code for chronic kidney disease (ICD‐9 codes 585.0585.5, 585.9) in their first 20 admission diagnoses. These codes are highly specific for CKD but have lower sensitivity.[9] We excluded all patients with a history of transplant (996.81, V42.0, n=90) or ESRD (585.6, n=416). We excluded repeat admissions during the study period (n=138). Our final sample included 590 unique patients with ICD‐9 diagnosis of CKD without ESRD.

Demographic, Clinical, and Health Service Utilization Characteristics

Our outcome was CKD awareness, the patient's correct self‐report of kidney disease. Patients selected their chronic medical conditions from a list read to them and were specifically asked if they had kidney problems. Demographic characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education were also obtained. Healthcare utilization variables included how often the patient saw their primary medical care provider in the past year and whether patients had a prior hospitalization in the last year.

Health status variables such as mental status, diabetes, hypertension, and CKD stage were also assessed. Mental status was quantified using the telephone version of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE), scored from 1 to 22.10 We defined diabetes as ICD‐9 codes 250.0250.00, and hypertension as ICD‐9 codes 401.0, 401.9, 403, 405.09, 405.19, 405.91, 405.99, or by patient self‐report. CKD stage was based on the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from the medical record using Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines.[11] We used the mode of the eGFR to calculate the appropriate CKD stage for those with more than 1 eGFR value from the hospitalization (576/590, 98%). The eGFR was calculated by the modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation: (GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)=175 (Screatinine)1.154 (Age)0.203 (0.742 if female) x (1.212 if African American)) recommended by the National Kidney Disease Education Program.[12]

Analysis

We used logistic regression to analyze the influence of the demographic, clinical, and healthcare utilization covariates on the likelihood of a patient reporting kidney problems. For the multivariate analysis, we sequentially added variables in a step‐wise fashion. We adjusted for (1) demographic factors: gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education; (2) eGFR‐calculated CKD stage and comorbidities: diabetes, hypertension, and mental status; and (3) healthcare utilization in the last 12 months: any hospitalizations and the number of visits to a health provider.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Bivariable Association With Patient CKD Self‐Report

Table 1 shows demographic, clinical, and health service use characteristics for 590 patients with ICD‐9 coded CKD. In the bivariable model in Table 1, age, race, marital status and comorbidities, were associated with patient self‐report of CKD. Patients older than 80 years with physician‐identified CKD through ICD‐9 coding had 57% lower odds of reporting CKD than their younger counterparts. Patients of other races (nonwhite, non‐African American), married patients, and those with CKD stages 4 and 5 were much more likely to correctly self‐report CKD. Patients with higher MMSE score, diabetes, or hypertension had greater odds of CKD self‐report (all P<0.05).

| Total, N=590 | Bivariable Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Multivariable With Stepwise Addition (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1, Demographic Factors | Model 2, Plus CKD Stage and Other Comorbidities | Model 3, Plus Health Service Use | |||

| |||||

| Female | 312 (52.98%) | 1.21 (0.85‐1.70) | 1.64 (1.09‐2.47)* | 1.28 (0.79‐2.06) | 1.36 (0.75‐2.48) |

| Age, y | |||||

| Below 54 | 138 (23.4%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 5466 | 150 (24.4%) | 0.96 (0.59‐1.54) | 0.95 (0.56‐1.59) | 1.01 (0.56‐1.81) | 0.83 (0.41‐1.68) |

| 6779 | 161 (27.3%) | 0.77 (0.48‐1.23) | 0.67 (0.39‐1.15) | 0.66 (0.35‐1.23) | 0.72(0.34‐1.52) |

| Above 80 | 141 (23.9%) | 0.43 (0.26‐0.74) | 0.32 (0.17‐0.60) | 0.42 (0.20‐0.91)* | 0.37 (0.15‐0.93)* |

| Race | |||||

| African American | 449 (82.1%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| White | 75 (13.7%) | 1.47 (0.89‐2.42) | 1.53 (0.86‐2.71) | 1.56 (0.78‐3.12) | 1.08 (0.47‐2.49) |

| Other | 23 (4.2%) | 3.62 (1.53‐8.54) | 5.29 (1.78‐15.73) | 6.19 (1.72‐22.29) | 11.63 (1.80‐75.21)* |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic is reference group) | 21 (4.0%) | 0.97 (0.38‐2.44) | 0.43 (0.13‐1.45) | 0.71 (0.16‐3.09) | 0.46 (0.06‐3.57) |

| Married | 171 (32.6%) | 1.49 (1.03‐2.18)* | 1.32 (0.85‐2.04) | 1.20 (0.73‐1.98) | 1.77 (0.94‐3.33) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 128 (25.2%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| High school grad/some college | 296 (58.2%) | 1.05 (0.68‐1.63) | 0.93 (0.58‐1.49) | 0.95 (0.54‐1.67) | 0.85 (0.42‐1.72) |

| College grad or higher | 85 (16.7%) | 1.13 (0.64‐2.01) | 0.96 (0.51‐1.78) | 1.07 (0.51‐2.23) | 0.69 (0.27‐1.77) |

| CKD stage (eGFR calculated, mode) | |||||

| 12 | 115 (20.0%) | 0.55 (0.32‐0.95)* | 0.52 (0.27‐1.01) | 0.28 (0.11‐0.69) | |

| 3 | 300 (52.1%) | REF | REF | REF | |

| 4 | 112 (19.4%) | 2.43 (1.55‐3.81) | 2.69 (1.52‐4.76) | 3.07 (1.56‐6.07) | |

| 5 | 49 (8.5%) | 4.50 (2.39‐8.48) | 3.94 (1.81‐8.56) | 5.16 (1.85‐14.41) | |

| Diabetes (ICD‐9 coded or self‐report)‖ | 292 (49.5%) | 1.52 (1.07‐2.15)* | 1.54 (0.97‐2.45) | 1.26 (0.71‐2.26) | |

| Hypertension (ICD‐9 coded or self‐report) | 436 (73.9%) | 3.36 (2.09‐5.41) | 1.53 (0.80‐2.90) | 1.26 (0.57‐2.81) | |

| Mini‐Mental State Exam score# | 19.7 (2.5) | 1.13 (1.03‐1.23) | 1.09 (0.98‐1.22) | 1.22 (1.06‐1.42) | |

| Hospitalized in last 12 months | 253 (46.9%) | 1.50 (1.05‐2.13)* | 1.12 (0.65‐1.95) | ||

| No. of visits to health provider | |||||

| Once/year or less | 80 (18.4%) | REF | REF | ||

| 23 times/year | 58 (13.3%) | 0.80 (0.40‐1.60) | 0.44 (0.17‐1.16) | ||

| 4+ times/year | 298 (68.4%) | 0.60 (0.36‐0.99)* | 0.38 (0.19‐0.74) | ||

Multivariable Associations With Patient CKD Self‐Report

Age, race, and CKD stage remained consistently associated with CKD self‐report, although the magnitude of the effects (odds ratios [ORs]) varied across models (Table 1). Across all the models, patients older than 80 years were still significantly less likely than younger patients to self‐report CKD (ORs ranging from 0.32 to 0.42, all P<0.05). Patients classified as being of other race were found to have a 5.29 to 11.63 greater odds of CKD self‐report than African American patients (all P<0.05).

Patients with CKD stage 4 and 5 were more likely to self‐report than patients with CKD stage 3 (ORs ranging from 2.693.07 for stage 4 and 3.945.16 for stage 5, P<0.05). In the final model, every unit increase in MMSE score increased the odds of CKD self‐report by 22%. In addition, patients who saw their health provider 4 or more times per year were 62% less likely to self‐report CKD than patients who saw their provider 1 or fewer times per year (OR: 0.38, P<0.05).

A large proportion of patients (68.6%) were CKD unspecified by ICD‐9 codes, and only 27% of the unspecified group reported having CKD (Table 2). Examining the eGFR CKD stage of the CKD unspecified group showed that 22.8% were eGFR‐determined CKD stage 1 to 2, 57.1% were CKD stage 3, 14.8% were CKD stage 4, and 5.3% were CKD stage 5. Patients had 2 to 3 times greater odds of correct CKD self‐report if physicians had correctly identified their CKD stage (bivariable OR: 2.42, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.57‐3.72, multivariable OR: 3.22, 95% CI: 0.99‐10.46) (analysis not shown).

| CKD Stage* | Physician (ICD‐9) Coded | eGFR Calculated | eGFR Coded With ICD‐9 Correct |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Unspecified | 110 (27.2%) | ||

| 12 | 5 (31.2%) | 20 (17.4%) | 0 |

| 3 | 25 (27.2%) | 83 (27.7%) | 17 (29.8%) |

| 4 | 40 (63.5%) | 54 (48.2%) | 25 (69.4%) |

| 5 | 11 (78.6%) | 31 (63.3%) | 10 (83.3%) |

DISCUSSION

Although prior work has examined CKD awareness in the general population and in high‐risk cohorts,[2, 3, 13] this is the first study examining CKD awareness in an urban, underserved hospitalized population. We found that overall patients' CKD awareness was low (32%), but increased as high as 63% for CKD stage 5, even after controlling for patient demographic, clinical characteristics, and healthcare use. Our overall rate of CKD awareness was higher than prior studies overall and at lower CKD stages.[2, 3, 13] Our work is consistent with prior literature that shows increasing CKD awareness with advancing CKD stage.[2, 3, 13]

Older patients (>80 years) had lower awareness of CKD. Older patients are more likely to have a near normal creatinine, despite a markedly reduced eGFR, so their CKD may go unnoticed.[14] Even with appropriate recognition, providers may also feel like their CKD is unlikely to progress to ESRD, given its stability and/or their competing risk of death.[15] Finally, older hospitalized patients may also be less likely to report a CKD diagnosis due to difficulty in recall due to denial, dementia, or delirium.

One limitation is that our case‐finding for CKD was physician ICD‐9 coding, which is highly specific but not sensitive.[9] The majority of patients with physician‐identified CKD were CKD unspecified, perhaps due to poor coding, physician underdocumentation, or physician under‐recognition of CKD stage. Although only 27% of the CKD unspecified group correctly self‐identified as having CKD, over 75% were found to be CKD stage 3 or higher, which should trigger additional monitoring or care based on guidelines.[10] In addition, despite statistical significance, we may not be able to make meaningful inferences about our small other group (nonwhite, non‐African American). Our sample was from 1 hospitalan urban, academic, tertiary care center with a large proportion of African American patientswhich may limit generalizability. The multivariable model will need to be tested in other populations for reproducibility.

Our study significantly contributes to the literature by examining patient awareness of CKD in a high‐risk, urban, hospitalized minority population. Other study strengths include use of basic demographic information, as well as survey and laboratory data for a richer examination of the associations between patient factors and CKD awareness.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalized patients with CKD have a low CKD awareness. Patient awareness of their CKD is increased with physician documentation of CKD severity. Patient awareness of their CKD must be coupled with provider awareness and CKD documentation to link patients to multidisciplinary CKD education and care to slow CKD progression and reduce associated cardiovascular and metabolic complications. Further work is needed across hospitals to determineand improveCKD awareness among both patients and providers.

Disclosures

Dr. Saunders was supported by Pilot and Feasibility Funding from the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 DK092949). Dr. Chin was supported by NIDDK K24 DK071933. Dr. Meltzer was supported by NIA T35 AG029795. Dr. Saunders had full access to all of the study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. An abstract of this article was presented at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada in March 2014 and at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in San Diego, California in April 2014. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects over 13% of the US population and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.[1] However, only 10% of individuals with CKD are aware of their diagnoses.[2] Even in those with stage 5 CKD, only 60% of individuals are aware of their CKD.[3] To our knowledge, no work has examined CKD awareness in a hospitalized patient population.

Patient awareness of their CKD diagnosis is important because progression of kidney disease can be slowed by patient self‐management of diabetes and hypertension.[4] Patient awareness of CKD may also increase acceptance of preend‐stage renal disease (ESRD) patient education and nephrology referral, which have been shown to delay CKD progression and improve clinical status at dialysis initiation.[5] However, only 60% of patients with advanced CKD have visited a nephrologist in the past year or have seen a nephrologist prior to dialysis initiation.[1]

The hospital is an important site for patient education and linkage to outpatient care for patients with CKD.[6] The hospital serves high‐risk patients who may not be well connected to outpatient care or who have lesswell‐controlled disease.[6, 7] Thus, hospitalization represents an opportunity to identify existing CKD and to use a multidisciplinary approach to preventative care, patient education, and patient‐provider planning for renal replacement therapy needs. In our cross‐sectional study in an urban, minority‐serving hospital, we sought to determine what patient factors were associated with hospitalized patients correctly self‐identifying as having CKD.

METHODS

Subjects and Data

We used data from the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project, a study of hospitalized patient outcomes.[8] Within 48 hours of hospitalization, all general medicine patients or their proxies are approached to enroll. During one‐on‐one inpatient interviews, a trained research assistant obtains demographic, health status, and healthcare utilization information. Participants consent for study staff to review their medical records. More than 80% of general medicine patients enroll.

We obtained data on 1234 general medicine patients discharged between January 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013 with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) code for chronic kidney disease (ICD‐9 codes 585.0585.5, 585.9) in their first 20 admission diagnoses. These codes are highly specific for CKD but have lower sensitivity.[9] We excluded all patients with a history of transplant (996.81, V42.0, n=90) or ESRD (585.6, n=416). We excluded repeat admissions during the study period (n=138). Our final sample included 590 unique patients with ICD‐9 diagnosis of CKD without ESRD.

Demographic, Clinical, and Health Service Utilization Characteristics

Our outcome was CKD awareness, the patient's correct self‐report of kidney disease. Patients selected their chronic medical conditions from a list read to them and were specifically asked if they had kidney problems. Demographic characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education were also obtained. Healthcare utilization variables included how often the patient saw their primary medical care provider in the past year and whether patients had a prior hospitalization in the last year.

Health status variables such as mental status, diabetes, hypertension, and CKD stage were also assessed. Mental status was quantified using the telephone version of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE), scored from 1 to 22.10 We defined diabetes as ICD‐9 codes 250.0250.00, and hypertension as ICD‐9 codes 401.0, 401.9, 403, 405.09, 405.19, 405.91, 405.99, or by patient self‐report. CKD stage was based on the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from the medical record using Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines.[11] We used the mode of the eGFR to calculate the appropriate CKD stage for those with more than 1 eGFR value from the hospitalization (576/590, 98%). The eGFR was calculated by the modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation: (GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)=175 (Screatinine)1.154 (Age)0.203 (0.742 if female) x (1.212 if African American)) recommended by the National Kidney Disease Education Program.[12]

Analysis

We used logistic regression to analyze the influence of the demographic, clinical, and healthcare utilization covariates on the likelihood of a patient reporting kidney problems. For the multivariate analysis, we sequentially added variables in a step‐wise fashion. We adjusted for (1) demographic factors: gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education; (2) eGFR‐calculated CKD stage and comorbidities: diabetes, hypertension, and mental status; and (3) healthcare utilization in the last 12 months: any hospitalizations and the number of visits to a health provider.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Bivariable Association With Patient CKD Self‐Report

Table 1 shows demographic, clinical, and health service use characteristics for 590 patients with ICD‐9 coded CKD. In the bivariable model in Table 1, age, race, marital status and comorbidities, were associated with patient self‐report of CKD. Patients older than 80 years with physician‐identified CKD through ICD‐9 coding had 57% lower odds of reporting CKD than their younger counterparts. Patients of other races (nonwhite, non‐African American), married patients, and those with CKD stages 4 and 5 were much more likely to correctly self‐report CKD. Patients with higher MMSE score, diabetes, or hypertension had greater odds of CKD self‐report (all P<0.05).

| Total, N=590 | Bivariable Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Multivariable With Stepwise Addition (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1, Demographic Factors | Model 2, Plus CKD Stage and Other Comorbidities | Model 3, Plus Health Service Use | |||

| |||||

| Female | 312 (52.98%) | 1.21 (0.85‐1.70) | 1.64 (1.09‐2.47)* | 1.28 (0.79‐2.06) | 1.36 (0.75‐2.48) |

| Age, y | |||||

| Below 54 | 138 (23.4%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 5466 | 150 (24.4%) | 0.96 (0.59‐1.54) | 0.95 (0.56‐1.59) | 1.01 (0.56‐1.81) | 0.83 (0.41‐1.68) |

| 6779 | 161 (27.3%) | 0.77 (0.48‐1.23) | 0.67 (0.39‐1.15) | 0.66 (0.35‐1.23) | 0.72(0.34‐1.52) |

| Above 80 | 141 (23.9%) | 0.43 (0.26‐0.74) | 0.32 (0.17‐0.60) | 0.42 (0.20‐0.91)* | 0.37 (0.15‐0.93)* |

| Race | |||||

| African American | 449 (82.1%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| White | 75 (13.7%) | 1.47 (0.89‐2.42) | 1.53 (0.86‐2.71) | 1.56 (0.78‐3.12) | 1.08 (0.47‐2.49) |

| Other | 23 (4.2%) | 3.62 (1.53‐8.54) | 5.29 (1.78‐15.73) | 6.19 (1.72‐22.29) | 11.63 (1.80‐75.21)* |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic is reference group) | 21 (4.0%) | 0.97 (0.38‐2.44) | 0.43 (0.13‐1.45) | 0.71 (0.16‐3.09) | 0.46 (0.06‐3.57) |

| Married | 171 (32.6%) | 1.49 (1.03‐2.18)* | 1.32 (0.85‐2.04) | 1.20 (0.73‐1.98) | 1.77 (0.94‐3.33) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 128 (25.2%) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| High school grad/some college | 296 (58.2%) | 1.05 (0.68‐1.63) | 0.93 (0.58‐1.49) | 0.95 (0.54‐1.67) | 0.85 (0.42‐1.72) |

| College grad or higher | 85 (16.7%) | 1.13 (0.64‐2.01) | 0.96 (0.51‐1.78) | 1.07 (0.51‐2.23) | 0.69 (0.27‐1.77) |

| CKD stage (eGFR calculated, mode) | |||||

| 12 | 115 (20.0%) | 0.55 (0.32‐0.95)* | 0.52 (0.27‐1.01) | 0.28 (0.11‐0.69) | |

| 3 | 300 (52.1%) | REF | REF | REF | |

| 4 | 112 (19.4%) | 2.43 (1.55‐3.81) | 2.69 (1.52‐4.76) | 3.07 (1.56‐6.07) | |

| 5 | 49 (8.5%) | 4.50 (2.39‐8.48) | 3.94 (1.81‐8.56) | 5.16 (1.85‐14.41) | |

| Diabetes (ICD‐9 coded or self‐report)‖ | 292 (49.5%) | 1.52 (1.07‐2.15)* | 1.54 (0.97‐2.45) | 1.26 (0.71‐2.26) | |

| Hypertension (ICD‐9 coded or self‐report) | 436 (73.9%) | 3.36 (2.09‐5.41) | 1.53 (0.80‐2.90) | 1.26 (0.57‐2.81) | |

| Mini‐Mental State Exam score# | 19.7 (2.5) | 1.13 (1.03‐1.23) | 1.09 (0.98‐1.22) | 1.22 (1.06‐1.42) | |

| Hospitalized in last 12 months | 253 (46.9%) | 1.50 (1.05‐2.13)* | 1.12 (0.65‐1.95) | ||

| No. of visits to health provider | |||||

| Once/year or less | 80 (18.4%) | REF | REF | ||

| 23 times/year | 58 (13.3%) | 0.80 (0.40‐1.60) | 0.44 (0.17‐1.16) | ||

| 4+ times/year | 298 (68.4%) | 0.60 (0.36‐0.99)* | 0.38 (0.19‐0.74) | ||

Multivariable Associations With Patient CKD Self‐Report

Age, race, and CKD stage remained consistently associated with CKD self‐report, although the magnitude of the effects (odds ratios [ORs]) varied across models (Table 1). Across all the models, patients older than 80 years were still significantly less likely than younger patients to self‐report CKD (ORs ranging from 0.32 to 0.42, all P<0.05). Patients classified as being of other race were found to have a 5.29 to 11.63 greater odds of CKD self‐report than African American patients (all P<0.05).

Patients with CKD stage 4 and 5 were more likely to self‐report than patients with CKD stage 3 (ORs ranging from 2.693.07 for stage 4 and 3.945.16 for stage 5, P<0.05). In the final model, every unit increase in MMSE score increased the odds of CKD self‐report by 22%. In addition, patients who saw their health provider 4 or more times per year were 62% less likely to self‐report CKD than patients who saw their provider 1 or fewer times per year (OR: 0.38, P<0.05).

A large proportion of patients (68.6%) were CKD unspecified by ICD‐9 codes, and only 27% of the unspecified group reported having CKD (Table 2). Examining the eGFR CKD stage of the CKD unspecified group showed that 22.8% were eGFR‐determined CKD stage 1 to 2, 57.1% were CKD stage 3, 14.8% were CKD stage 4, and 5.3% were CKD stage 5. Patients had 2 to 3 times greater odds of correct CKD self‐report if physicians had correctly identified their CKD stage (bivariable OR: 2.42, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.57‐3.72, multivariable OR: 3.22, 95% CI: 0.99‐10.46) (analysis not shown).

| CKD Stage* | Physician (ICD‐9) Coded | eGFR Calculated | eGFR Coded With ICD‐9 Correct |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Unspecified | 110 (27.2%) | ||

| 12 | 5 (31.2%) | 20 (17.4%) | 0 |

| 3 | 25 (27.2%) | 83 (27.7%) | 17 (29.8%) |

| 4 | 40 (63.5%) | 54 (48.2%) | 25 (69.4%) |

| 5 | 11 (78.6%) | 31 (63.3%) | 10 (83.3%) |

DISCUSSION

Although prior work has examined CKD awareness in the general population and in high‐risk cohorts,[2, 3, 13] this is the first study examining CKD awareness in an urban, underserved hospitalized population. We found that overall patients' CKD awareness was low (32%), but increased as high as 63% for CKD stage 5, even after controlling for patient demographic, clinical characteristics, and healthcare use. Our overall rate of CKD awareness was higher than prior studies overall and at lower CKD stages.[2, 3, 13] Our work is consistent with prior literature that shows increasing CKD awareness with advancing CKD stage.[2, 3, 13]

Older patients (>80 years) had lower awareness of CKD. Older patients are more likely to have a near normal creatinine, despite a markedly reduced eGFR, so their CKD may go unnoticed.[14] Even with appropriate recognition, providers may also feel like their CKD is unlikely to progress to ESRD, given its stability and/or their competing risk of death.[15] Finally, older hospitalized patients may also be less likely to report a CKD diagnosis due to difficulty in recall due to denial, dementia, or delirium.

One limitation is that our case‐finding for CKD was physician ICD‐9 coding, which is highly specific but not sensitive.[9] The majority of patients with physician‐identified CKD were CKD unspecified, perhaps due to poor coding, physician underdocumentation, or physician under‐recognition of CKD stage. Although only 27% of the CKD unspecified group correctly self‐identified as having CKD, over 75% were found to be CKD stage 3 or higher, which should trigger additional monitoring or care based on guidelines.[10] In addition, despite statistical significance, we may not be able to make meaningful inferences about our small other group (nonwhite, non‐African American). Our sample was from 1 hospitalan urban, academic, tertiary care center with a large proportion of African American patientswhich may limit generalizability. The multivariable model will need to be tested in other populations for reproducibility.

Our study significantly contributes to the literature by examining patient awareness of CKD in a high‐risk, urban, hospitalized minority population. Other study strengths include use of basic demographic information, as well as survey and laboratory data for a richer examination of the associations between patient factors and CKD awareness.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalized patients with CKD have a low CKD awareness. Patient awareness of their CKD is increased with physician documentation of CKD severity. Patient awareness of their CKD must be coupled with provider awareness and CKD documentation to link patients to multidisciplinary CKD education and care to slow CKD progression and reduce associated cardiovascular and metabolic complications. Further work is needed across hospitals to determineand improveCKD awareness among both patients and providers.

Disclosures

Dr. Saunders was supported by Pilot and Feasibility Funding from the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 DK092949). Dr. Chin was supported by NIDDK K24 DK071933. Dr. Meltzer was supported by NIA T35 AG029795. Dr. Saunders had full access to all of the study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. An abstract of this article was presented at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada in March 2014 and at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in San Diego, California in April 2014. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- United States Renal Data System. Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End‐Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2012.

- , , , et al. Chronic kidney disease awareness among individuals with clinical markers of kidney dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Neph. 2011;6(8):1838–1844.

- , , , et al. Comparison of CKD awareness in a screening population using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study and CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD‐EPI) equations. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3 suppl 2):S17–S23.

- , , , et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(3):646–661.

- , , , et al. Multidisciplinary predialysis education decreases the incidence of dialysis and reduces mortality—a controlled cohort study based on the NKFDOQI guidelines. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(11):3426–3433.

- , , . Pre‐dialysis hospital use and late referrals in incident dialysis patients in England: a retrospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(1):124–129.

- , , , et al. Do hospitals that provide heart failure patient education prior to discharge also promote continuity of care? A report from OPTIMIZE‐HF. J Card Fail. 2006;12(6 suppl):S111.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , , et al. Failure of ICD‐9‐CM codes to identify patients with comorbid chronic kidney disease in diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(2):564–580.

- , , , . Validation of a telephone version of the mini‐mental state examination. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(7):697–702.

- National Kidney Foundation. Kidney disease outcomes quality initiative guidelines 2002. Available at: http://www2.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_ckd/toc.htm. Accessed October 9, 2014.

- , , , , , . A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–470.

- , , , et al. Prevalence and awareness of CKD among African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(2):238–247.

- , , , , , . Magnitude of underascertainment of impaired kidney function in older adults with normal serum creatinine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(6):816–823.

- , , , et al. Prediction, Progression, and Outcomes of Chronic Kidney Disease in Older Adults. J Am Soc Neph. 2009;20(6):1199–1209.

- United States Renal Data System. Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End‐Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2012.

- , , , et al. Chronic kidney disease awareness among individuals with clinical markers of kidney dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Neph. 2011;6(8):1838–1844.

- , , , et al. Comparison of CKD awareness in a screening population using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study and CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD‐EPI) equations. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3 suppl 2):S17–S23.

- , , , et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(3):646–661.

- , , , et al. Multidisciplinary predialysis education decreases the incidence of dialysis and reduces mortality—a controlled cohort study based on the NKFDOQI guidelines. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(11):3426–3433.

- , , . Pre‐dialysis hospital use and late referrals in incident dialysis patients in England: a retrospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(1):124–129.

- , , , et al. Do hospitals that provide heart failure patient education prior to discharge also promote continuity of care? A report from OPTIMIZE‐HF. J Card Fail. 2006;12(6 suppl):S111.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , , et al. Failure of ICD‐9‐CM codes to identify patients with comorbid chronic kidney disease in diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(2):564–580.

- , , , . Validation of a telephone version of the mini‐mental state examination. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(7):697–702.

- National Kidney Foundation. Kidney disease outcomes quality initiative guidelines 2002. Available at: http://www2.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_ckd/toc.htm. Accessed October 9, 2014.

- , , , , , . A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–470.

- , , , et al. Prevalence and awareness of CKD among African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(2):238–247.

- , , , , , . Magnitude of underascertainment of impaired kidney function in older adults with normal serum creatinine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(6):816–823.

- , , , et al. Prediction, Progression, and Outcomes of Chronic Kidney Disease in Older Adults. J Am Soc Neph. 2009;20(6):1199–1209.

EVB in Hospitalized Cirrhotic Patients

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death in the United States. In 2010, cirrhosis resulted in an estimated 49,500 deaths, which represented a significant increase from 35,500 deaths 2 decades ago.[1] Cirrhotic patients are susceptible to numerous disease‐specific complications including ascites, esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS).[2]

Esophageal varices develop in approximately 50% of patient with cirrhosis, and their presence correlates with the severity of liver disease.[3] In cirrhotic patients, esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB) occurs at an annual rate of 5% to 15% and results in substantial morbidity and mortality.[3] Utilizing US national data, Jamal et al. reported a decline in the rate of hospitalizations related to EVB from 1988 to 2002.[4] However, recent large‐scale studies relating to the epidemiology of EVB are lacking. We conducted a retrospective analysis using a national US database to study the differences in demographic characteristics, rate of complications, outcomes, and temporal trends in hospitalized cirrhotic patients with and without EVB.

METHODS

We utilized biennial data (20022012) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample using methods described earlier.[5] Initially, we extracted all entries with any discharge diagnosis of cirrhosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes: 571.2, 571.5, 571.6) in adult patients ages 18 years and older.[6] Within this cirrhotic population, we next extracted all entries with any discharge diagnosis of EVB (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 456.0., 456.20).[6] Population‐based rates relating to hospital discharges were reported as per 100,000 population/year.

The outcome variables of interest were in‐hospital mortality, total charges (rounded to the nearest $1000) and length of stay (LOS). Demographic details and hospital characteristics were also extracted. Cases were queried for complications well recognized in cirrhotic patients. These included urinary tract infection (UTI) (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 1122, 59010‐11, 5902‐03, 59080‐81, 5950, 5970, 5990), skin and subcutaneous tissue infections (SSCI) (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 680‐82, 684, 686), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 56723, 5672), Clostridium difficile infection (ICD‐9‐CM code: 00845), or pneumonia (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 480‐83, 487).[6] Also queried were HE (ICD‐9‐CM code: 572.2)[7] and HRS (ICD‐9‐CM code: 572.4).[8] Comorbid conditions were assessed using the Elixhauser comorbidity index minus the presence of liver disorders but including alcohol abuse.[9]

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To determine the independent association of EVB on outcome variables, we performed case‐control matching (EVB vs no EVB). We used high‐dimensional propensity scores in a 1:5 matching ratio with a greedy matching algorithm generated by regression analysis of patients with EVB based on demographics details (age, gender, insurance status), comorbid conditions, alcohol abuse, infections as detailed above, HE, and HRS. The 2 test and the Mann‐Whitney U test compared categorical and continuous variables. For trend analysis, we used the Cochrane‐Armitage test. The threshold for significance for all analyses was P<0.01.

RESULTS

In 2012, there were 570,020 hospital discharges related to cirrhosis in patients 18 years of age and older. Within this cohort, EVB occurred in 32,945 discharges (5.78%). Table 1 details differences between cirrhotic patients with and without EVB. Comparatively, patients with EVB were younger (median age 55 years, interquartile range [IQR] 13 years vs median age 58 years, IQR 15 years; P<0.01), more likely to be male (70.1% vs 60.4%; P<0.01), and without health insurance (21.0% vs 12.50%; P<0.01). Minor differences between the 2 groups were observed in respect to hospital region, location, teaching status, and household income quartile. There was no difference in the number of comorbid conditions (median 4 comorbid conditions in each group).

| Study Group | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis Without Variceal Bleeding | Cirrhosis With Variceal Bleeding | ||

| |||

| Total 570,220 (100%) | 537,275 (94.22%) | 32,945 (5.78%) | |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 58 (15) | 55 (13) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 60.40% | 70.10% | |

| Female | 39.60% | 29.90% | |

| Mortality | 5.80% | 9.90% | |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 19.70% | 22.40% | |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 67.80% | 56.60% | |

| None | 12.50% | 21.00% | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 4 (5) | 4 (4) | |

| Hospital charges, median (IQR) | 28 (39) | 41 (49) | |

| Associated comorbidities, median (IQR) | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 48.80% | 63.90% | |

| Infections | |||

| Overall | 24.10% | 13.50% | |

| UTI | 13.10% | 6.90% | |

| Pneumonia | 1.50% | 1.40% | 0.03 |

| SBP | 3.40% | 3.40% | 0.45 |

| SSCI | 6.30% | 1.70% | |

| CDI | 2.20% | 1.40% | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 17.70% | 18.80% | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 3.70% | 4.30% | |

| EVL | 66.40% | ||

| TIPS | 4.90% | ||

| Blood transfusions | 56.90% | ||

Patients with EVB suffered a significantly higher rate of alcohol abuse (63.90% vs 48.80%; P<0.01). EVB was also associated with an overall lower incidence of infection (13.50% vs 24.10%; P<0.01). Specifically, the greatest difference in rates of infection were observed for UTI (6.90% vs 13.10%; P<0.01) and SSCI (1.70% vs 6.30%; P<0.01). Also, patients with EVB demonstrated a small, yet significant increased incidence of HE (18.80% vs 17.70%; P<0.01) and HRS (4.30% vs 3.70%; P<0.01).

Cirrhotic patients with EVB demonstrated worse overall outcomes compared to their counterparts without EVB. This manifested in an unadjusted higher mortality rate (9.90% vs 5.80%; P<0.01) and increased hospital charges (median $41,000 [IQR $49,000] vs $28,000 [IQR $39,000]; P<0.01). LOS between the 2 groups did not differ (median 4 days). After adjusting for demographic differences, complications, and comorbid conditions, EVB in patients with cirrhosis continued to be independently associated with a higher mortality rate (10.00% vs 5.00%; P<0.01) and increased hospital charges (median $41,000 [IQR $49,000] vs $26,000 [IQR $34,000]; P<0.01). Again, LOS was similar for the 2 groups (median 4 days).

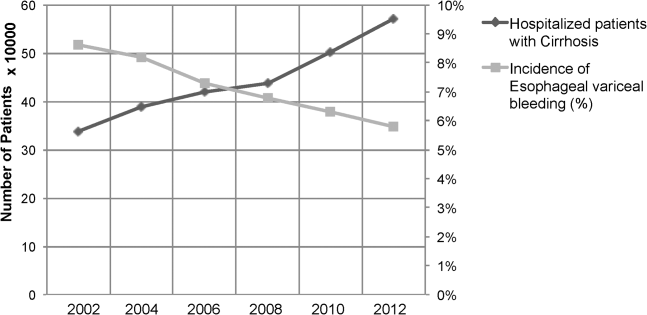

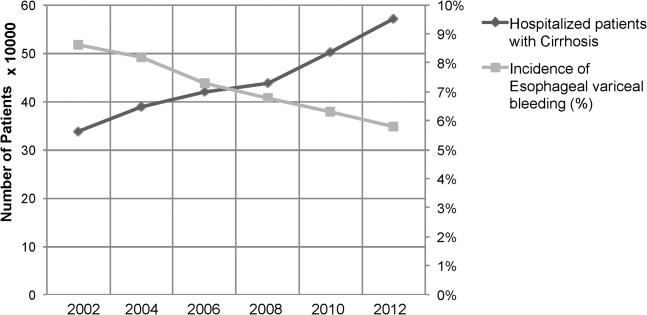

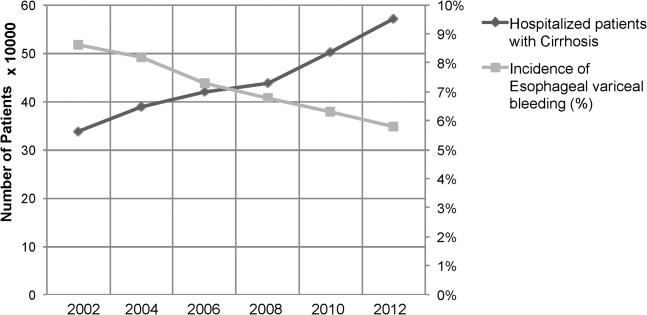

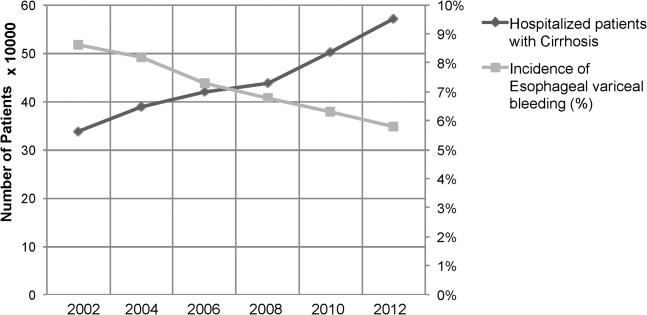

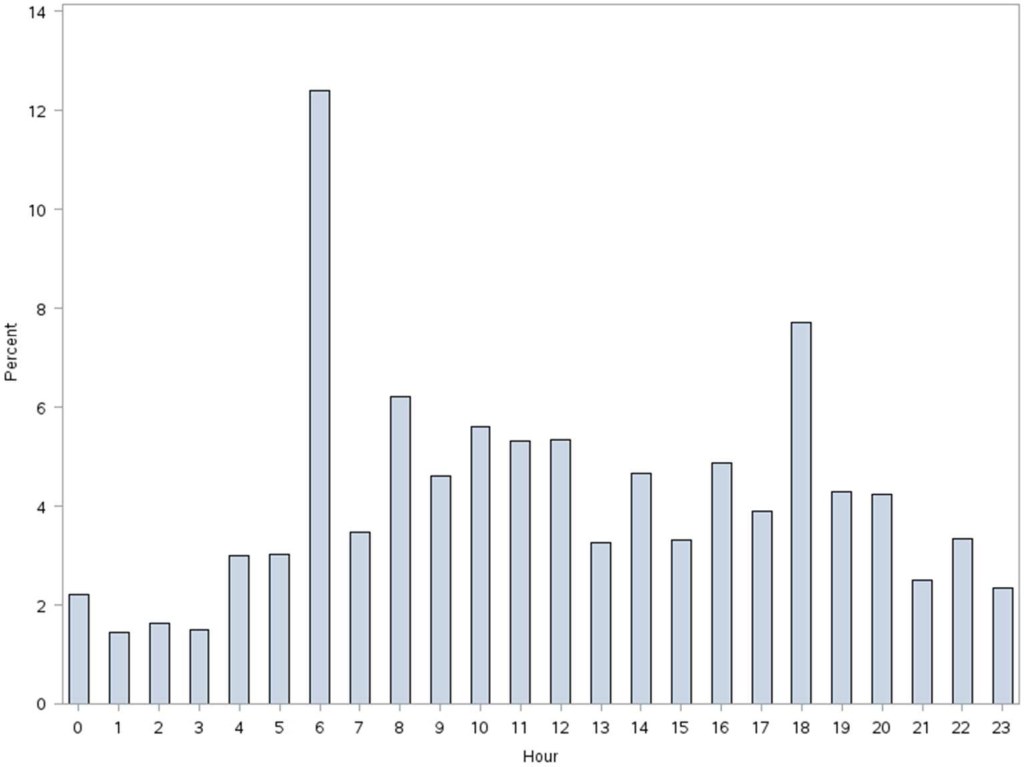

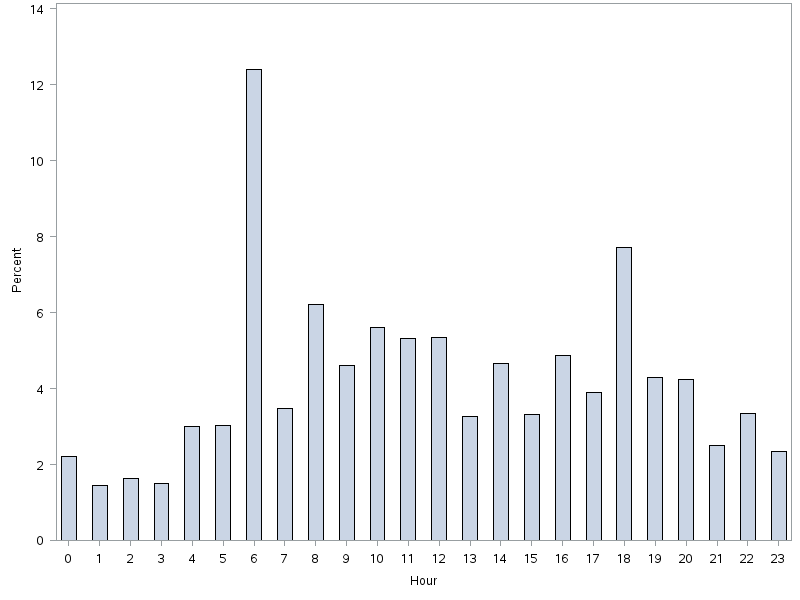

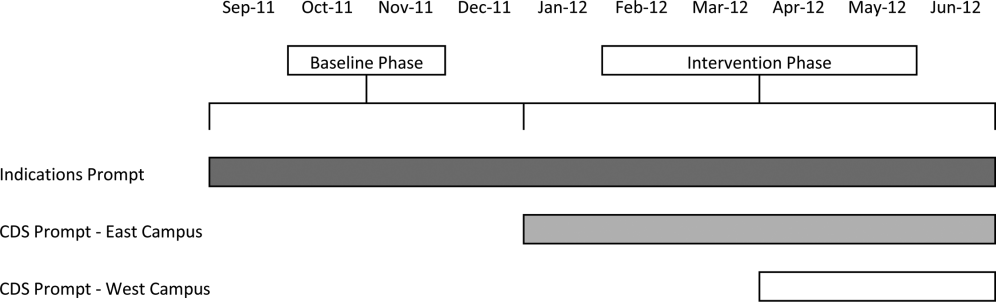

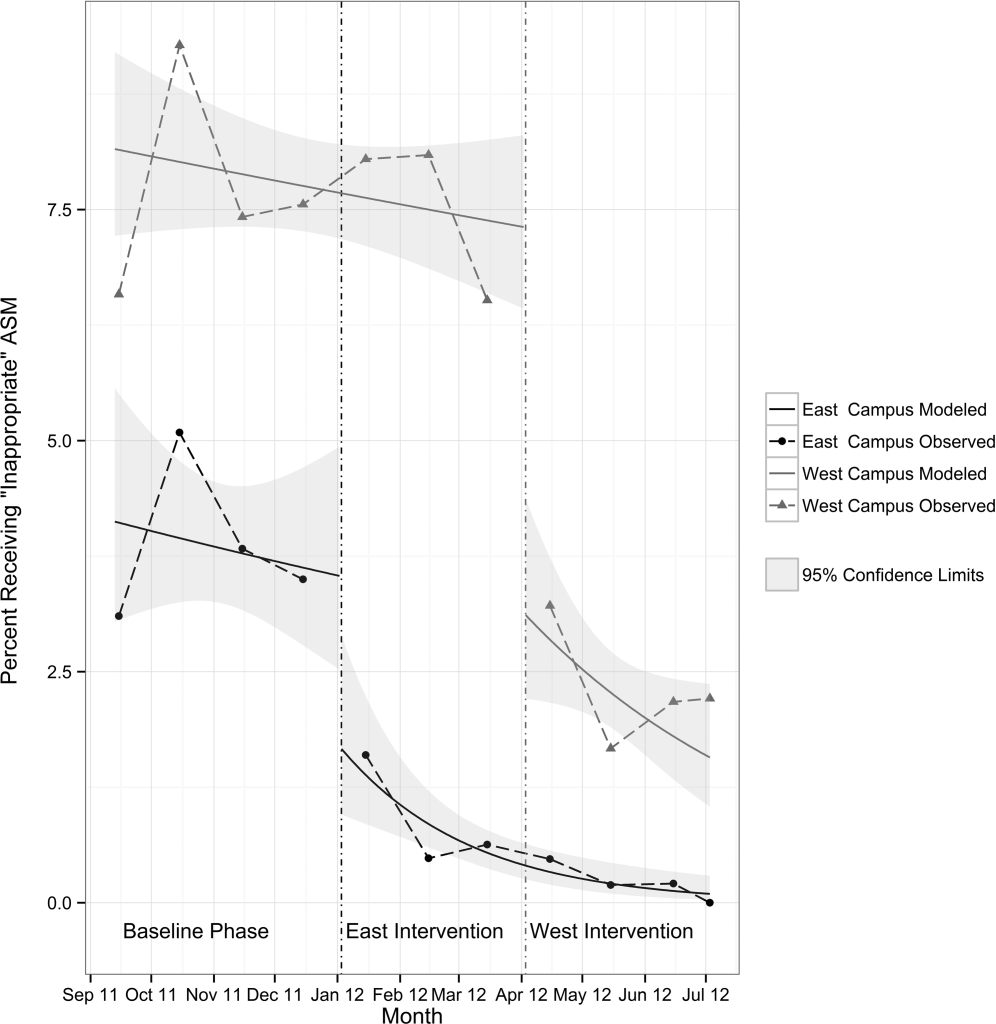

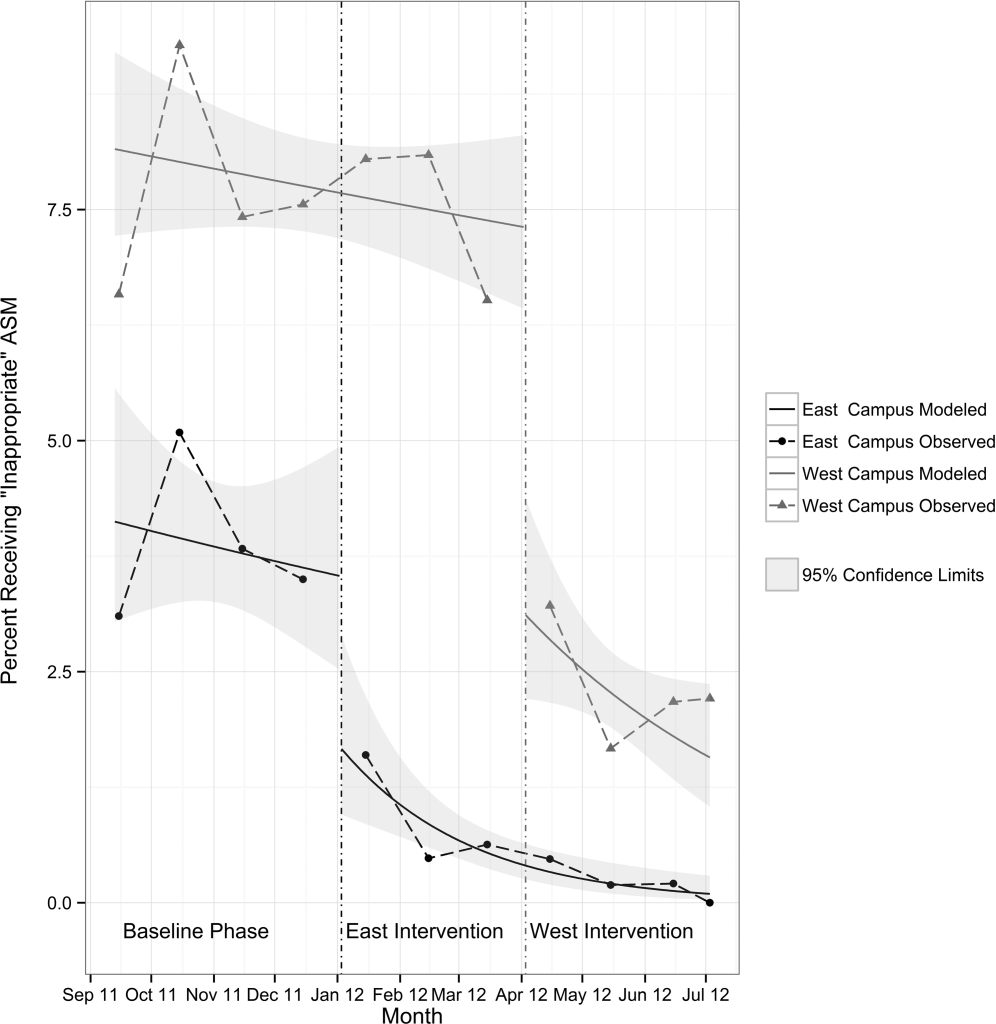

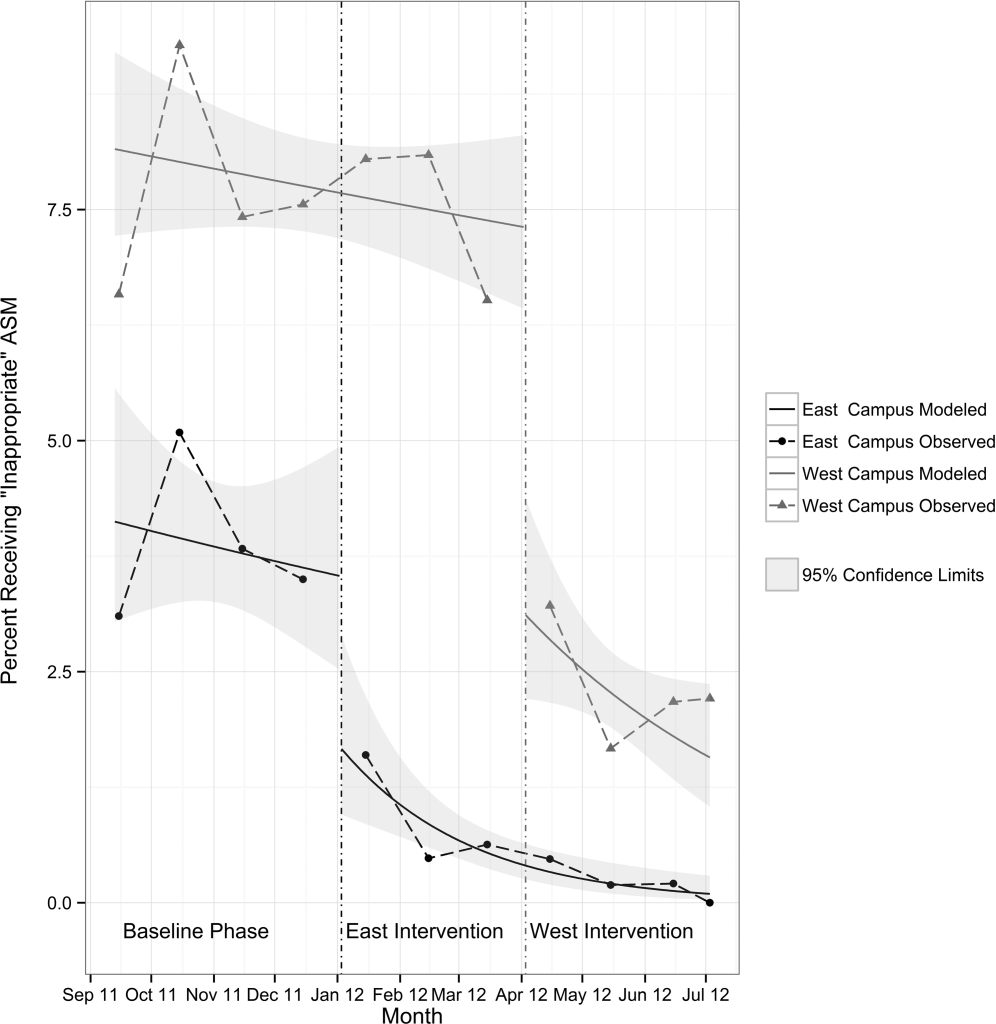

Between the years 2002 and 2012, the number of hospital discharges related to cirrhosis increased from 337,956 to 570,220 (P<0.01). Concurrently, the incidence of EVB in this population declined from 8.60% to 5.78% (Figure 1), representing an overall decrease of 33.0% with a significant decreased trend (P<0.01).

We also calculated population‐adjusted hospitalization rates for discharges related to cirrhosis and EVB. The rate of cirrhosis‐related discharges continued to demonstrate an increased trend from 157.42/100,000 population in 2002 to 237.43/100,000 population in 2012 (P<0.01). However, no significant trend was observed for EVB‐related hospital discharges in the same period of time (13.60/100,000 population in 2002 to 13.72/100,000 population in 2012; P=0.91).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicated a significantly higher rate of alcohol abuse in cirrhotic patients with EVB. Alcohol consumption is an independent risk factor for esophageal variceal bleeding.[10, 11] Continued alcohol consumption not only increases the risk for development of varices but may also precipitate variceal rupture.[10] Other risk factors associated with EVB in this study (younger age, male, lower economic status) are likely related to a higher incidence of alcohol abuse in this demographic.[12]

Patients with EVB were also noted to have a lower overall incidence of infection, especially UTI and SSCI. The use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics decreases mortality from secondary infection and improves the prognosis of cirrhotic patients with EVB.[13, 14] The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends the use of third‐generation cephalosporins in the setting of EVB.[3] The widespread adoption of this in clinical practice may have contributed to a decreased rate of infection in patients with EVB. The difference in the incidence rates of HE and HRS, although statistically significant, were small, and likely the consequence of the large numbers involved in our study.

Our results also indicate that cirrhotic patients with EVB were twice as likely to die compared to matched counterparts without EVB. The increased mortality associated with EVB could be related to hemorrhagic/hypovolemic shock and cardiovascular collapse, aspiration into airway, multiorgan dysfunction due to poor perfusion, infections including SBP, and HE. Although prior studies have demonstrated the relationship between EVB and increased mortality, typically they have been restricted to small single‐center studies involving fewer than 200 patients.[6, 7, 8, 9] Cirrhotic patients with EVB also incurred significantly higher hospital charges compared to matched counterparts. Interestingly, the hospital LOS did not differ between the 2 groups. Intensive care and procedural costs were likely a major contributor to the higher charges; cirrhotic patients with EVB underwent a median of 3 procedures (IQR 2) during their hospital stay compared to a median of 1 procedure (IQR 3) for cirrhotic patients without EVB (P<0.01; data not shown).

In contrast to trends from earlier decades,[4] the population‐adjusted rate of EVB‐related hospital discharges did not change significantly from 2002 to 2012. However, these data are confounded in their interpretation by a substantial increase in the prevalence of cirrhosis in the United States during the same time period.[15] Therefore, it may be more meaningful to state that there was a contemporaneous decline in EVB‐related hospital discharges when considered in the context of a complicating rate in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. These results are consistent with a recent single‐center study[16] and are very likely the fruition of intensive screening programs with primary and secondary prophylaxis for EVB involving esophageal variceal ligation and pharmacotherapy (‐blockers) as well as the increased acceptance of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement.[17, 18, 19]

There are limitations to our study. First, we relied exclusively on ICD‐9‐CM codes for case identification. Second, there is a nonavailability of data pertaining to Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease score calculations, medication, and antibiotic usage. Third, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database does not allow for distinguishing individual patients with repeat admissions. Finally, our results represent a weighted estimate of national data.

CONCLUSION

EVB in cirrhotic patients was associated with significantly higher mortality and increased hospital charges. Also, the rate of EVB‐related hospital discharges as a complicating factor in patients with cirrhosis declined significantly during the decade 2002 to 2012. This likely reflects the ongoing effectiveness of primary and secondary prophylaxis.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample, sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which contributes to HCUP (

Disclosures: C.P., the first author and corresponding author, conceptualized the study, and with A.D. gathered and analyzed the data. C.P. and M.D. wrote, edited, and proofread the manuscript as well as created the bibliography and formulated the table and figure. R.G., R.T., and M.O. edited, commented on, and reviewed the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and agreed on the final version of the manuscript for submission. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990‐2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608.

- , Complications of cirrhosis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28(3):223–229.

- , , , , Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922–938.

- , , , Declining hospitalization rate of esophageal variceal bleeding in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(6):689–695; quiz 605.

- , , , , , Association of Clostridium difficile infection with outcomes of hospitalized solid organ transplant recipients: results from the 2009 Nationwide Inpatient Sample database. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14(5):540–547.

- , , Prevalence and in‐hospital mortality trends of infections among patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide study of hospitalised patients in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(1):105–112.

- , , Racial disparities in the management of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and complications of portal hypertension: a national study. Hepatology. 2007;45(5):1282–1289.

- , Protein‐calorie malnutrition as a prognostic indicator of mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Liver Int. 2009;29(9):1396–1402.

- , , , Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

- , , , , , Potential precipitating factors of esophageal variceal bleeding: a case‐control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(1):96–103.

- , , , et al. Effects of ethanol consumption on hepatic hemodynamics in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(4):1284–1289.

- , , , Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM‐IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842.

- , , Role of prophylactic antibiotics in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(7):1790–1796.

- , , , et al. Meta‐analysis: antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding—an updated Cochrane review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(5):509–518.

- , , , et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population‐based study [published online ahead of print October 8, 2014]. J Clin Gastroenterol. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208.

- , , , Hospitalization for variceal hemorrhage in an era with more prevalent cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(32):11326–11332.

- , Banding ligation versus beta‐blockers for primary prevention in oesophageal varices in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD004544.

- , , , et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2370–2379.

- , , , Meta‐analysis: banding ligation and medical interventions for the prevention of rebleeding from oesophageal varices. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(10):1155–1165.

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death in the United States. In 2010, cirrhosis resulted in an estimated 49,500 deaths, which represented a significant increase from 35,500 deaths 2 decades ago.[1] Cirrhotic patients are susceptible to numerous disease‐specific complications including ascites, esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS).[2]

Esophageal varices develop in approximately 50% of patient with cirrhosis, and their presence correlates with the severity of liver disease.[3] In cirrhotic patients, esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB) occurs at an annual rate of 5% to 15% and results in substantial morbidity and mortality.[3] Utilizing US national data, Jamal et al. reported a decline in the rate of hospitalizations related to EVB from 1988 to 2002.[4] However, recent large‐scale studies relating to the epidemiology of EVB are lacking. We conducted a retrospective analysis using a national US database to study the differences in demographic characteristics, rate of complications, outcomes, and temporal trends in hospitalized cirrhotic patients with and without EVB.

METHODS

We utilized biennial data (20022012) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample using methods described earlier.[5] Initially, we extracted all entries with any discharge diagnosis of cirrhosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes: 571.2, 571.5, 571.6) in adult patients ages 18 years and older.[6] Within this cirrhotic population, we next extracted all entries with any discharge diagnosis of EVB (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 456.0., 456.20).[6] Population‐based rates relating to hospital discharges were reported as per 100,000 population/year.

The outcome variables of interest were in‐hospital mortality, total charges (rounded to the nearest $1000) and length of stay (LOS). Demographic details and hospital characteristics were also extracted. Cases were queried for complications well recognized in cirrhotic patients. These included urinary tract infection (UTI) (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 1122, 59010‐11, 5902‐03, 59080‐81, 5950, 5970, 5990), skin and subcutaneous tissue infections (SSCI) (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 680‐82, 684, 686), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 56723, 5672), Clostridium difficile infection (ICD‐9‐CM code: 00845), or pneumonia (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 480‐83, 487).[6] Also queried were HE (ICD‐9‐CM code: 572.2)[7] and HRS (ICD‐9‐CM code: 572.4).[8] Comorbid conditions were assessed using the Elixhauser comorbidity index minus the presence of liver disorders but including alcohol abuse.[9]

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To determine the independent association of EVB on outcome variables, we performed case‐control matching (EVB vs no EVB). We used high‐dimensional propensity scores in a 1:5 matching ratio with a greedy matching algorithm generated by regression analysis of patients with EVB based on demographics details (age, gender, insurance status), comorbid conditions, alcohol abuse, infections as detailed above, HE, and HRS. The 2 test and the Mann‐Whitney U test compared categorical and continuous variables. For trend analysis, we used the Cochrane‐Armitage test. The threshold for significance for all analyses was P<0.01.

RESULTS

In 2012, there were 570,020 hospital discharges related to cirrhosis in patients 18 years of age and older. Within this cohort, EVB occurred in 32,945 discharges (5.78%). Table 1 details differences between cirrhotic patients with and without EVB. Comparatively, patients with EVB were younger (median age 55 years, interquartile range [IQR] 13 years vs median age 58 years, IQR 15 years; P<0.01), more likely to be male (70.1% vs 60.4%; P<0.01), and without health insurance (21.0% vs 12.50%; P<0.01). Minor differences between the 2 groups were observed in respect to hospital region, location, teaching status, and household income quartile. There was no difference in the number of comorbid conditions (median 4 comorbid conditions in each group).

| Study Group | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis Without Variceal Bleeding | Cirrhosis With Variceal Bleeding | ||

| |||

| Total 570,220 (100%) | 537,275 (94.22%) | 32,945 (5.78%) | |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 58 (15) | 55 (13) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 60.40% | 70.10% | |

| Female | 39.60% | 29.90% | |

| Mortality | 5.80% | 9.90% | |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 19.70% | 22.40% | |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 67.80% | 56.60% | |

| None | 12.50% | 21.00% | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 4 (5) | 4 (4) | |

| Hospital charges, median (IQR) | 28 (39) | 41 (49) | |

| Associated comorbidities, median (IQR) | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 48.80% | 63.90% | |

| Infections | |||

| Overall | 24.10% | 13.50% | |

| UTI | 13.10% | 6.90% | |

| Pneumonia | 1.50% | 1.40% | 0.03 |

| SBP | 3.40% | 3.40% | 0.45 |

| SSCI | 6.30% | 1.70% | |

| CDI | 2.20% | 1.40% | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 17.70% | 18.80% | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 3.70% | 4.30% | |

| EVL | 66.40% | ||

| TIPS | 4.90% | ||

| Blood transfusions | 56.90% | ||

Patients with EVB suffered a significantly higher rate of alcohol abuse (63.90% vs 48.80%; P<0.01). EVB was also associated with an overall lower incidence of infection (13.50% vs 24.10%; P<0.01). Specifically, the greatest difference in rates of infection were observed for UTI (6.90% vs 13.10%; P<0.01) and SSCI (1.70% vs 6.30%; P<0.01). Also, patients with EVB demonstrated a small, yet significant increased incidence of HE (18.80% vs 17.70%; P<0.01) and HRS (4.30% vs 3.70%; P<0.01).

Cirrhotic patients with EVB demonstrated worse overall outcomes compared to their counterparts without EVB. This manifested in an unadjusted higher mortality rate (9.90% vs 5.80%; P<0.01) and increased hospital charges (median $41,000 [IQR $49,000] vs $28,000 [IQR $39,000]; P<0.01). LOS between the 2 groups did not differ (median 4 days). After adjusting for demographic differences, complications, and comorbid conditions, EVB in patients with cirrhosis continued to be independently associated with a higher mortality rate (10.00% vs 5.00%; P<0.01) and increased hospital charges (median $41,000 [IQR $49,000] vs $26,000 [IQR $34,000]; P<0.01). Again, LOS was similar for the 2 groups (median 4 days).

Between the years 2002 and 2012, the number of hospital discharges related to cirrhosis increased from 337,956 to 570,220 (P<0.01). Concurrently, the incidence of EVB in this population declined from 8.60% to 5.78% (Figure 1), representing an overall decrease of 33.0% with a significant decreased trend (P<0.01).

We also calculated population‐adjusted hospitalization rates for discharges related to cirrhosis and EVB. The rate of cirrhosis‐related discharges continued to demonstrate an increased trend from 157.42/100,000 population in 2002 to 237.43/100,000 population in 2012 (P<0.01). However, no significant trend was observed for EVB‐related hospital discharges in the same period of time (13.60/100,000 population in 2002 to 13.72/100,000 population in 2012; P=0.91).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicated a significantly higher rate of alcohol abuse in cirrhotic patients with EVB. Alcohol consumption is an independent risk factor for esophageal variceal bleeding.[10, 11] Continued alcohol consumption not only increases the risk for development of varices but may also precipitate variceal rupture.[10] Other risk factors associated with EVB in this study (younger age, male, lower economic status) are likely related to a higher incidence of alcohol abuse in this demographic.[12]

Patients with EVB were also noted to have a lower overall incidence of infection, especially UTI and SSCI. The use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics decreases mortality from secondary infection and improves the prognosis of cirrhotic patients with EVB.[13, 14] The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends the use of third‐generation cephalosporins in the setting of EVB.[3] The widespread adoption of this in clinical practice may have contributed to a decreased rate of infection in patients with EVB. The difference in the incidence rates of HE and HRS, although statistically significant, were small, and likely the consequence of the large numbers involved in our study.

Our results also indicate that cirrhotic patients with EVB were twice as likely to die compared to matched counterparts without EVB. The increased mortality associated with EVB could be related to hemorrhagic/hypovolemic shock and cardiovascular collapse, aspiration into airway, multiorgan dysfunction due to poor perfusion, infections including SBP, and HE. Although prior studies have demonstrated the relationship between EVB and increased mortality, typically they have been restricted to small single‐center studies involving fewer than 200 patients.[6, 7, 8, 9] Cirrhotic patients with EVB also incurred significantly higher hospital charges compared to matched counterparts. Interestingly, the hospital LOS did not differ between the 2 groups. Intensive care and procedural costs were likely a major contributor to the higher charges; cirrhotic patients with EVB underwent a median of 3 procedures (IQR 2) during their hospital stay compared to a median of 1 procedure (IQR 3) for cirrhotic patients without EVB (P<0.01; data not shown).

In contrast to trends from earlier decades,[4] the population‐adjusted rate of EVB‐related hospital discharges did not change significantly from 2002 to 2012. However, these data are confounded in their interpretation by a substantial increase in the prevalence of cirrhosis in the United States during the same time period.[15] Therefore, it may be more meaningful to state that there was a contemporaneous decline in EVB‐related hospital discharges when considered in the context of a complicating rate in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. These results are consistent with a recent single‐center study[16] and are very likely the fruition of intensive screening programs with primary and secondary prophylaxis for EVB involving esophageal variceal ligation and pharmacotherapy (‐blockers) as well as the increased acceptance of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement.[17, 18, 19]

There are limitations to our study. First, we relied exclusively on ICD‐9‐CM codes for case identification. Second, there is a nonavailability of data pertaining to Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease score calculations, medication, and antibiotic usage. Third, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database does not allow for distinguishing individual patients with repeat admissions. Finally, our results represent a weighted estimate of national data.

CONCLUSION

EVB in cirrhotic patients was associated with significantly higher mortality and increased hospital charges. Also, the rate of EVB‐related hospital discharges as a complicating factor in patients with cirrhosis declined significantly during the decade 2002 to 2012. This likely reflects the ongoing effectiveness of primary and secondary prophylaxis.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample, sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which contributes to HCUP (

Disclosures: C.P., the first author and corresponding author, conceptualized the study, and with A.D. gathered and analyzed the data. C.P. and M.D. wrote, edited, and proofread the manuscript as well as created the bibliography and formulated the table and figure. R.G., R.T., and M.O. edited, commented on, and reviewed the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and agreed on the final version of the manuscript for submission. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death in the United States. In 2010, cirrhosis resulted in an estimated 49,500 deaths, which represented a significant increase from 35,500 deaths 2 decades ago.[1] Cirrhotic patients are susceptible to numerous disease‐specific complications including ascites, esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS).[2]

Esophageal varices develop in approximately 50% of patient with cirrhosis, and their presence correlates with the severity of liver disease.[3] In cirrhotic patients, esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB) occurs at an annual rate of 5% to 15% and results in substantial morbidity and mortality.[3] Utilizing US national data, Jamal et al. reported a decline in the rate of hospitalizations related to EVB from 1988 to 2002.[4] However, recent large‐scale studies relating to the epidemiology of EVB are lacking. We conducted a retrospective analysis using a national US database to study the differences in demographic characteristics, rate of complications, outcomes, and temporal trends in hospitalized cirrhotic patients with and without EVB.

METHODS

We utilized biennial data (20022012) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample using methods described earlier.[5] Initially, we extracted all entries with any discharge diagnosis of cirrhosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes: 571.2, 571.5, 571.6) in adult patients ages 18 years and older.[6] Within this cirrhotic population, we next extracted all entries with any discharge diagnosis of EVB (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 456.0., 456.20).[6] Population‐based rates relating to hospital discharges were reported as per 100,000 population/year.