User login

Cognitive Biases Influence Decision-Making Regarding Postacute Care in a Skilled Nursing Facility

The combination of decreasing hospital lengths of stay and increasing age and comorbidity of the United States population is a principal driver of the increased use of postacute care in the US.1-3 Postacute care refers to care in long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and care provided by home health agencies after an acute hospitalization. In 2016, 43% of Medicare beneficiaries received postacute care after hospital discharge at the cost of $60 billion annually; nearly half of these received care in an SNF.4 Increasing recognition of the significant cost and poor outcomes of postacute care led to payment reforms, such as bundled payments, that incentivized less expensive forms of postacute care and improvements in outcomes.5-9 Early evaluations suggested that hospitals are sensitive to these reforms and responded by significantly decreasing SNF utilization.10,11 It remains unclear whether this was safe and effective.

In this context, increased attention to how hospital clinicians and hospitalized patients decide whether to use postacute care (and what form to use) is appropriate since the effect of payment reforms could negatively impact vulnerable populations of older adults without adequate protection.12 Suboptimal decision-making can drive both overuse and inappropriate underuse of this expensive medical resource. Initial evidence suggests that patients and clinicians are poorly equipped to make high-quality decisions about postacute care, with significant deficits in both the decision-making process and content.13-16 While these gaps are important to address, they may only be part of the problem. The fields of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics have revealed new insights into decision-making, demonstrating that people deviate from rational decision-making in predictable ways, termed decision heuristics, or cognitive biases.17 This growing field of research suggests heuristics or biases play important roles in decision-making and determining behavior, particularly in situations where there may be little information provided and the patient is stressed, tired, and ill—precisely like deciding on postacute care.18 However, it is currently unknown whether cognitive biases are at play when making hospital discharge decisions.

We sought to identify the most salient heuristics or cognitive biases patients may utilize when making decisions about postacute care at the end of their hospitalization and ways clinicians may contribute to these biases. The overall goal was to derive insights for improving postacute care decision-making.

METHODS

Study Design

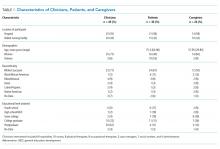

We conducted a secondary analysis on interviews with hospital and SNF clinicians as well as patients and their caregivers who were either leaving the hospital for an SNF or newly arrived in an SNF from the hospital to understand if cognitive biases were present and how they manifested themselves in a real-world clinical context.19 These interviews were part of a larger qualitative study that sought to understand how clinicians, patients, and their caregivers made decisions about postacute care, particularly related to SNFs.13,14 This study represents the analysis of all our interviews, specifically examining decision-making bias. Participating sites, clinical roles, and both patient and caregiver characteristics (Table 1) in our cohort have been previously described.13,14

Analysis

We used a team-based approach to framework analysis, which has been used in other decision-making studies14, including those measuring cognitive bias.20 A limitation in cognitive bias research is the lack of a standardized list or categorization of cognitive biases. We reviewed prior systematic17,21 and narrative reviews18,22, as well as prior studies describing examples of cognitive biases playing a role in decision-making about therapy20 to construct a list of possible cognitive biases to evaluate and narrow these a priori to potential biases relevant to the decision about postacute care based on our prior work (Table 2).

We applied this framework to analyze transcripts through an iterative process of deductive coding and reviewing across four reviewers (ML, RA, AL, CL) and a hospitalist physician with expertise leading qualitative studies (REB).

Intercoder consensus was built through team discussion by resolving points of disagreement.23 Consistency of coding was regularly checked by having more than one investigator code individual manuscripts and comparing coding, and discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. We triangulated the data (shared our preliminary results) using a larger study team, including an expert in behavioral economics (SRG), physicians at study sites (EC, RA), and an anthropologist with expertise in qualitative methods (CL). We did this to ensure credibility (to what extent the findings are credible or believable) and confirmability of findings (ensuring the findings are based on participant narratives rather than researcher biases).

RESULTS

We reviewed a total of 105 interviews with 25 hospital clinicians, 20 SNF clinicians, 21 patients and 14 caregivers in the hospital, and 15 patients and 10 caregivers in the SNF setting (Table 1). We found authority bias/halo effect; default/status quo bias, anchoring bias, and framing was commonly present in decision-making about postacute care in a SNF, whereas there were few if any examples of ambiguity aversion, availability heuristic, confirmation bias, optimism bias, or false consensus effect (Table 2).

Authority Bias/Halo Effect

While most patients deferred to their inpatient teams when it came to decision-making, this effect seemed to differ across VA and non-VA settings. Veterans expressed a higher degree of potential authority bias regarding the VA as an institution, whereas older adults in non-VA settings saw physicians as the authority figure making decisions in their best interests.

Veterans expressed confidence in the VA regarding both whether to go to a SNF and where to go:

“The VA wouldn’t license [an SNF] if they didn’t have a good reputation for care, cleanliness, things of that nature” (Veteran, VA CLC)

“I just knew the VA would have my best interests at heart” (Veteran, VA CLC)

Their caregivers expressed similar confidence:

“I’m not gonna decide [on whether the patient they care for goes to postacute care], like I told you, that’s totally up to the VA. I have trust and faith in them…so wherever they send him, that’s where he’s going” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In some cases, this perspective was closer to the halo effect: a positive experience with the care provider or the care team led the decision-makers to believe that their recommendations about postacute care would be similarly positive.

“I think we were very trusting in the sense that whatever happened the last time around, he survived it…they took care of him…he got back home, and he started his life again, you know, so why would we question what they’re telling us to do? (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In contrast to Veterans, non-Veteran patients seemed to experience authority bias when it came to the inpatient team.

“Well, I’d like to know more about the PTs [Physical Therapists] there, but I assume since they were recommended, they will be good.” (Patient, University hospital)

This perspective was especially apparent when it came to physicians:

“The level of trust that they [patients] put in their doctor is gonna outweigh what anyone else would say.” (Clinical liaison, SNF)

“[In response to a question about influences on the decision to go to rehab] I don’t…that’s not my decision to make, that’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

“They said so…[the doctor] said I needed to go to rehab, so I guess I do because it’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

Default/Status quo Bias

In a related way, patients and caregivers with exposure to a SNF seemed to default to the same SNF with which they had previous experience. This bias seems to be primarily related to knowing what to expect.

“He thinks it’s [a particular SNF] the right place for him now…he was there before and he knew, again, it was the right place for him to be” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

“It’s the only one I’ve ever been in…but they have a lot of activities; you have a lot of freedom, staff was good” (Patient, VA hospital)

“I’ve been [to this SNF] before and I kind of know what the program involves…so it was kind of like going home, not, going home is the wrong way to put it…I mean coming here is like something I know, you know, I didn’t need anybody to explain it to me.” (Patient, VA hospital)

“Anybody that’s been to [SNF], that would be their choice to go back to, and I guess I must’ve liked it that first time because I asked to go back again.” (Patient, University hospital)

Anchoring Bias

While anchoring bias was less frequent, it came up in two domains: first, related to costs of care, and second, related to facility characteristics. Costs came up most frequently for Veterans who preferred to move their care to the VA for cost reasons, which appeared in these cases to overshadow other considerations:

“I kept emphasizing that the VA could do all the same things at a lot more reasonable price. The whole purpose of having the VA is for the Veteran, so that…we can get the healthcare that we need at a more reasonable [sic] or a reasonable price.” (Veteran, CLC)

“I think the CLC [VA SNF] is going to take care of her probably the same way any other facility of its type would, unless she were in a private facility, but you know, that costs a lot more money.” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

Patients occasionally had striking responses to particular characteristics of SNFs, regardless of whether this was a central feature or related to their rehabilitation:

“The social worker comes and talks to me about the nursing home where cats are running around, you know, to infect my leg or spin their little cat hairs into my lungs and make my asthma worse…I’m going to have to beg the nurses or the aides or the family or somebody to clean the cat…” (Veteran, VA hospital)

Framing

Framing was the strongest theme among clinician interviews in our sample. Clinicians most frequently described the SNF as a place where patients could recover function (a positive frame), explaining risks (eg, rehospitalization) associated with alternative postacute care options besides the SNF in great detail.

“Aside from explaining the benefits of going and…having that 24-hour care, having the therapies provided to them [the patients], talking about them getting stronger, phrasing it in such a way that patients sometimes are more agreeable, like not calling it a skilled nursing facility, calling it a rehab you know, for them to get physically stronger so they can be the most independent that they can once they do go home, and also explaining … we think that this would be the best plan to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, so those are some of the things that we’ll mention to patients to try and educate them and get them to be agreeable for placement.” (Social worker, University hospital)

Clinicians avoided negative associations with “nursing home” (even though all SNFs are nursing homes) and tended to use more positive frames such as “rehabilitation facility.”

“Use the word rehab….we definitely use the word rehab, to get more therapy, to go home; it’s not a, we really emphasize it’s not a nursing home, it’s not to go to stay forever.” (Physical therapist, safety-net hospital)

Clinicians used a frame of “safety” when discussing the SNF and used a frame of “risk” when discussing alternative postacute care options such as returning home. We did not find examples of clinicians discussing similar risks in going to a SNF even for risks, such as falling, which exist in both settings.

“I’ve talked to them primarily on an avenue of safety because I think people want and they value independence, they value making sure they can get home, but you know, a lot of the times they understand safety is, it can be a concern and outlining that our goal is to make sure that they’re safe and they stay home, and I tend to broach the subject saying that our therapists believe that they might not be safe at home in the moment, but they have potential goals to be safe later on if we continue therapy. I really highlight safety being the major driver of our discussion.” (Physician, VA hospital)

In some cases, framing was so overt that other risk-mitigating options (eg, home healthcare) are not discussed.

“I definitely tend to explain the ideal first. I’m not going to bring up home care when we really think somebody should go to rehab, however, once people say I don’t want to do that, I’m not going, then that’s when I’m like OK, well, let’s talk to the doctors, but we can see about other supports in the home.” (Social worker, VA hospital)

DISCUSSION

In a large sample of patients and their caregivers, as well as multidisciplinary clinicians at three different hospitals and three SNFs, we found authority bias/halo effect and framing biases were most common and seemed most impactful. Default/status quo bias and anchoring bias were also present in decision-making about a SNF. The combination of authority bias/halo effect and framing biases could synergistically interact to augment the likelihood of patients accepting a SNF for postacute care. Patients who had been to a SNF before seemed more likely to choose the SNF they had experienced previously even if they had no other postacute care experiences, and could be highly influenced by isolated characteristics of that facility (such as the physical environment or cost of care).

It is important to mention that cognitive biases do not necessarily have a negative impact: indeed, as Kahneman and Tversky point out, these are useful heuristics from “fast” thinking that are often effective.24 For example, clinicians may be trying to act in the best interests of the patient when framing the decision in terms of regaining function and averting loss of safety and independence. However, the evidence base regarding the outcomes of an SNF versus other postacute options is not robust, and this decision-making is complex. While this decision was most commonly framed in terms of rehabilitation and returning home, the fact that only about half of patients have returned to the community by 100 days4 was not discussed in any interview. In fact, initial evidence suggests replacing the SNF with home healthcare in patients with hip and knee arthroplasty may reduce costs without worsening clinical outcomes.6 However, across a broader population, SNFs significantly reduce 30-day readmissions when directly compared with home healthcare, but other clinical outcomes are similar.25 This evidence suggests that the “right” postacute care option for an individual patient is not clear, highlighting a key role biases may play in decision-making. Further, the nebulous concept of “safety” could introduce potential disparities related to social determinants of health.12 The observed inclination to accept an SNF with which the individual had prior experience may be influenced by the acceptability of this choice because of personal factors or prior research, even if it also represents a bias by limiting the consideration of current alternatives.

Our findings complement those of others in the literature which have also identified profound gaps in discharge decision-making among patients and clinicians,13-16,26-31 though to our knowledge the role of cognitive biases in these decisions has not been explored. This study also addresses gaps in the cognitive bias literature, including the need for real-world data rather than hypothetical vignettes,17 and evaluation of treatment and management decisions rather than diagnoses, which have been more commonly studied.21

These findings have implications for both individual clinicians and healthcare institutions. In the immediate term, these findings may serve as a call to discharging clinicians to modulate language and “debias” their conversations with patients about care after discharge.18,22 Shared decision-making requires an informed choice by patients based on their goals and values; framing a decision in a way that puts the clinician’s goals or values (eg, safety) ahead of patient values (eg, independence and autonomy) or limits disclosure (eg, a “rehab” is a nursing home) in the hope of influencing choice may be more consistent with framing bias and less with shared decision-making.14 Although controversy exists about the best way to “debias” oneself,32 self-awareness of bias is increasingly recognized across healthcare venues as critical to improving care for vulnerable populations.33 The use of data rather than vignettes may be a useful debiasing strategy, although the limitations of currently available data (eg, capturing nursing home quality) are increasingly recognized.34 From a policy and health system perspective, cognitive biases should be integrated into the development of decision aids to facilitate informed, shared, and high-quality decision-making that incorporates patient values, and perhaps “nudges” from behavioral economics to assist patients in choosing the right postdischarge care for them. Such nudges use principles of framing to influence care without restricting choice.35 As the science informing best practice regarding postacute care improves, identifying the “right” postdischarge care may become easier and recommendations more evidence-based.36

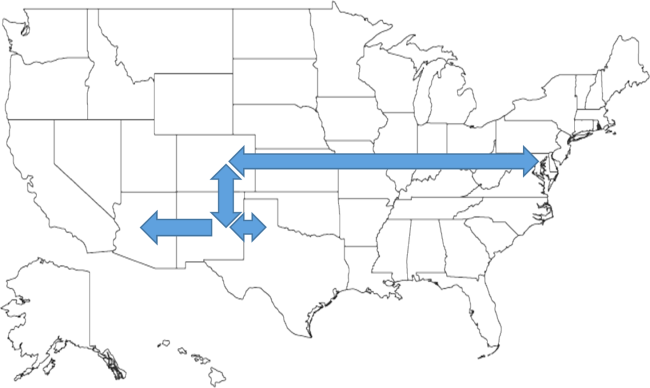

Strengths of the study include a large, diverse sample of patients, caregivers, and clinicians in both the hospital and SNF setting. Also, we used a team-based analysis with an experienced team and a deep knowledge of the data, including triangulation with clinicians to verify results. However, all hospitals and SNFs were located in a single metropolitan area, and responses may vary by region or population density. All three hospitals have housestaff teaching programs, and at the time of the interviews all three community SNFs were “five-star” facilities on the Nursing Home Compare website; results may be different at community hospitals or other SNFs. Hospitalists were the only physician group sampled in the hospital as they provide the majority of inpatient care to older adults; geriatricians, in particular, may have had different perspectives. Since we intended to explore whether cognitive biases were present overall, we did not evaluate whether cognitive biases differed by role or subgroup (by clinician type, patient, or caregiver), but this may be a promising area to explore in future work. Many cognitive biases have been described, and there are likely additional biases we did not identify. To confirm the generalizability of these findings, they should be studied in a larger, more generalizable sample of respondents in future work.

Cognitive biases play an important role in patient decision-making about postacute care, particularly regarding SNF care. As postacute care undergoes a transformation spurred by payment reforms, it is more important than ever to ensure that patients understand their choices at hospital discharge and can make a high-quality decision consistent with their goals.

1. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post-acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):295-296. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6383.

2. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Patient and hospitalization characteristics associated with increased postacute care facility discharges from US hospitals. Med Care. 2015;53(6):492-500. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000359.

3. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408.

4. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission June 2018 Report to Congress. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_ch5_medpacreport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 9, 2018.

5. Burke RE, Cumbler E, Coleman EA, Levy C. Post-acute care reform: implications and opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):46-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2673.

6. Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.12717.

7. Navathe AS, Troxel AB, Liao JM, et al. Cost of joint replacement using bundled payment models. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):214-222. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8263.

8. Kennedy G, Lewis VA, Kundu S, Mousqués J, Colla CH. Accountable care organizations and post-acute care: a focus on preferred SNF networks. Med Care Res Rev MCRR. 2018;1077558718781117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558718781117.

9. Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2013;32(5):864-872. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1262.

10. McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare shared savings program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):518-526. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9115.

11. Zhu JM, Patel V, Shea JA, Neuman MD, Werner RM. Hospitals using bundled payment report reducing skilled nursing facility use and improving care integration. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2018;37(8):1282-1289. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0257.

12. Burke RE, Ibrahim SA. Discharge destination and disparities in postoperative care. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1653-1654. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21884.

13. Burke RE, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, et al. How hospital clinicians select patients for skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2466-2472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14954.

14. Burke RE, Jones J, Lawrence E, et al. Evaluating the quality of patient decision-making regarding post-acute care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):678-684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4298-1.

15. Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Mor V. Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: individual and family perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2459-2465. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14988.

16. Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, Shield RR, Winblad U, Mor V. Patients are not given quality-of-care data about skilled nursing facilities when discharged from hospitals. Health Aff. 2017;36(8):1385-1391. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0155.

17. Blumenthal-Barby JS, Krieger H. Cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decision making: a critical review using a systematic search strategy. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2015;35(4):539-557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X14547740.

18. Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii58-ii64. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001712.

19. Hinds PS, Vogel RJ, Clarke-Steffen L. The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qual Health Res. 1997;7(3):408-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239700700306.

20. Magid M, Mcllvennan CK, Jones J, et al. Exploring cognitive bias in destination therapy left ventricular assist device decision making: a retrospective qualitative framework analysis. Am Heart J. 2016;180:64-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.06.024.

21. Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1.

22. Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 2: impediments to and strategies for change. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii65-ii72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001713.

23. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x.

24. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Daniel Kahneman. Macmillan. US Macmillan. https://us.macmillan.com/thinkingfastandslow/danielkahneman/9780374533557. Accessed February 5, 2019.

25. Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Coe NB. Does type of post-acute care matter? The effect of hospital discharge to home with home health care versus to skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern Med. In press.

26. Jones J, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, Leonard C, Ayele R, Burke RE. Nurses’ role in managing “The Fit” of older adults in skilled nursing facilities. J Gerontol Nurs. 2017;43(12):11-20. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20171110-06.

27. Lawrence E, Casler J-J, Jones J, et al. Variability in skilled nursing facility screening and admission processes: implications for value-based purchasing. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000225.

28. Ayele R, Jones J, Ladebue A, et al. Perceived costs of care influence post-acute care choices by clinicians, patients, and caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15768.

29. Sefcik JS, Nock RH, Flores EJ, et al. Patient preferences for information on post-acute care services. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(4):175-182. https://doi.org/10.3928/19404921-20160120-01.

30. Konetzka RT, Perraillon MC. Use of nursing home compare website appears limited by lack of awareness and initial mistrust of the data. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2016;35(4):706-713. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1377.

31. Schapira MM, Shea JA, Duey KA, Kleiman C, Werner RM. The nursing home compare report card: perceptions of residents and caregivers regarding quality ratings and nursing home choice. Health Serv Res. 2016;51 Suppl 2:1212-1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12458.

32. Dhaliwal G. Premature closure? Not so fast. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(2):87-89. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005267.

33. Masters C, Robinson D, Faulkner S, Patterson E, McIlraith T, Ansari A. Addressing biases in patient care with the 5Rs of cultural humility, a clinician coaching tool. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):627-630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4814-y.

34. Burke RE, Werner RM. Quality measurement and nursing homes: measuring what matters. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(7);520-523. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009447.

35. Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Nudge units to improve the delivery of health care. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(3):214-216. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1712984.

36. Jenq GY, Tinetti ME. Post–acute care: who belongs where? JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):296-297. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4298.

The combination of decreasing hospital lengths of stay and increasing age and comorbidity of the United States population is a principal driver of the increased use of postacute care in the US.1-3 Postacute care refers to care in long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and care provided by home health agencies after an acute hospitalization. In 2016, 43% of Medicare beneficiaries received postacute care after hospital discharge at the cost of $60 billion annually; nearly half of these received care in an SNF.4 Increasing recognition of the significant cost and poor outcomes of postacute care led to payment reforms, such as bundled payments, that incentivized less expensive forms of postacute care and improvements in outcomes.5-9 Early evaluations suggested that hospitals are sensitive to these reforms and responded by significantly decreasing SNF utilization.10,11 It remains unclear whether this was safe and effective.

In this context, increased attention to how hospital clinicians and hospitalized patients decide whether to use postacute care (and what form to use) is appropriate since the effect of payment reforms could negatively impact vulnerable populations of older adults without adequate protection.12 Suboptimal decision-making can drive both overuse and inappropriate underuse of this expensive medical resource. Initial evidence suggests that patients and clinicians are poorly equipped to make high-quality decisions about postacute care, with significant deficits in both the decision-making process and content.13-16 While these gaps are important to address, they may only be part of the problem. The fields of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics have revealed new insights into decision-making, demonstrating that people deviate from rational decision-making in predictable ways, termed decision heuristics, or cognitive biases.17 This growing field of research suggests heuristics or biases play important roles in decision-making and determining behavior, particularly in situations where there may be little information provided and the patient is stressed, tired, and ill—precisely like deciding on postacute care.18 However, it is currently unknown whether cognitive biases are at play when making hospital discharge decisions.

We sought to identify the most salient heuristics or cognitive biases patients may utilize when making decisions about postacute care at the end of their hospitalization and ways clinicians may contribute to these biases. The overall goal was to derive insights for improving postacute care decision-making.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a secondary analysis on interviews with hospital and SNF clinicians as well as patients and their caregivers who were either leaving the hospital for an SNF or newly arrived in an SNF from the hospital to understand if cognitive biases were present and how they manifested themselves in a real-world clinical context.19 These interviews were part of a larger qualitative study that sought to understand how clinicians, patients, and their caregivers made decisions about postacute care, particularly related to SNFs.13,14 This study represents the analysis of all our interviews, specifically examining decision-making bias. Participating sites, clinical roles, and both patient and caregiver characteristics (Table 1) in our cohort have been previously described.13,14

Analysis

We used a team-based approach to framework analysis, which has been used in other decision-making studies14, including those measuring cognitive bias.20 A limitation in cognitive bias research is the lack of a standardized list or categorization of cognitive biases. We reviewed prior systematic17,21 and narrative reviews18,22, as well as prior studies describing examples of cognitive biases playing a role in decision-making about therapy20 to construct a list of possible cognitive biases to evaluate and narrow these a priori to potential biases relevant to the decision about postacute care based on our prior work (Table 2).

We applied this framework to analyze transcripts through an iterative process of deductive coding and reviewing across four reviewers (ML, RA, AL, CL) and a hospitalist physician with expertise leading qualitative studies (REB).

Intercoder consensus was built through team discussion by resolving points of disagreement.23 Consistency of coding was regularly checked by having more than one investigator code individual manuscripts and comparing coding, and discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. We triangulated the data (shared our preliminary results) using a larger study team, including an expert in behavioral economics (SRG), physicians at study sites (EC, RA), and an anthropologist with expertise in qualitative methods (CL). We did this to ensure credibility (to what extent the findings are credible or believable) and confirmability of findings (ensuring the findings are based on participant narratives rather than researcher biases).

RESULTS

We reviewed a total of 105 interviews with 25 hospital clinicians, 20 SNF clinicians, 21 patients and 14 caregivers in the hospital, and 15 patients and 10 caregivers in the SNF setting (Table 1). We found authority bias/halo effect; default/status quo bias, anchoring bias, and framing was commonly present in decision-making about postacute care in a SNF, whereas there were few if any examples of ambiguity aversion, availability heuristic, confirmation bias, optimism bias, or false consensus effect (Table 2).

Authority Bias/Halo Effect

While most patients deferred to their inpatient teams when it came to decision-making, this effect seemed to differ across VA and non-VA settings. Veterans expressed a higher degree of potential authority bias regarding the VA as an institution, whereas older adults in non-VA settings saw physicians as the authority figure making decisions in their best interests.

Veterans expressed confidence in the VA regarding both whether to go to a SNF and where to go:

“The VA wouldn’t license [an SNF] if they didn’t have a good reputation for care, cleanliness, things of that nature” (Veteran, VA CLC)

“I just knew the VA would have my best interests at heart” (Veteran, VA CLC)

Their caregivers expressed similar confidence:

“I’m not gonna decide [on whether the patient they care for goes to postacute care], like I told you, that’s totally up to the VA. I have trust and faith in them…so wherever they send him, that’s where he’s going” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In some cases, this perspective was closer to the halo effect: a positive experience with the care provider or the care team led the decision-makers to believe that their recommendations about postacute care would be similarly positive.

“I think we were very trusting in the sense that whatever happened the last time around, he survived it…they took care of him…he got back home, and he started his life again, you know, so why would we question what they’re telling us to do? (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In contrast to Veterans, non-Veteran patients seemed to experience authority bias when it came to the inpatient team.

“Well, I’d like to know more about the PTs [Physical Therapists] there, but I assume since they were recommended, they will be good.” (Patient, University hospital)

This perspective was especially apparent when it came to physicians:

“The level of trust that they [patients] put in their doctor is gonna outweigh what anyone else would say.” (Clinical liaison, SNF)

“[In response to a question about influences on the decision to go to rehab] I don’t…that’s not my decision to make, that’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

“They said so…[the doctor] said I needed to go to rehab, so I guess I do because it’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

Default/Status quo Bias

In a related way, patients and caregivers with exposure to a SNF seemed to default to the same SNF with which they had previous experience. This bias seems to be primarily related to knowing what to expect.

“He thinks it’s [a particular SNF] the right place for him now…he was there before and he knew, again, it was the right place for him to be” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

“It’s the only one I’ve ever been in…but they have a lot of activities; you have a lot of freedom, staff was good” (Patient, VA hospital)

“I’ve been [to this SNF] before and I kind of know what the program involves…so it was kind of like going home, not, going home is the wrong way to put it…I mean coming here is like something I know, you know, I didn’t need anybody to explain it to me.” (Patient, VA hospital)

“Anybody that’s been to [SNF], that would be their choice to go back to, and I guess I must’ve liked it that first time because I asked to go back again.” (Patient, University hospital)

Anchoring Bias

While anchoring bias was less frequent, it came up in two domains: first, related to costs of care, and second, related to facility characteristics. Costs came up most frequently for Veterans who preferred to move their care to the VA for cost reasons, which appeared in these cases to overshadow other considerations:

“I kept emphasizing that the VA could do all the same things at a lot more reasonable price. The whole purpose of having the VA is for the Veteran, so that…we can get the healthcare that we need at a more reasonable [sic] or a reasonable price.” (Veteran, CLC)

“I think the CLC [VA SNF] is going to take care of her probably the same way any other facility of its type would, unless she were in a private facility, but you know, that costs a lot more money.” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

Patients occasionally had striking responses to particular characteristics of SNFs, regardless of whether this was a central feature or related to their rehabilitation:

“The social worker comes and talks to me about the nursing home where cats are running around, you know, to infect my leg or spin their little cat hairs into my lungs and make my asthma worse…I’m going to have to beg the nurses or the aides or the family or somebody to clean the cat…” (Veteran, VA hospital)

Framing

Framing was the strongest theme among clinician interviews in our sample. Clinicians most frequently described the SNF as a place where patients could recover function (a positive frame), explaining risks (eg, rehospitalization) associated with alternative postacute care options besides the SNF in great detail.

“Aside from explaining the benefits of going and…having that 24-hour care, having the therapies provided to them [the patients], talking about them getting stronger, phrasing it in such a way that patients sometimes are more agreeable, like not calling it a skilled nursing facility, calling it a rehab you know, for them to get physically stronger so they can be the most independent that they can once they do go home, and also explaining … we think that this would be the best plan to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, so those are some of the things that we’ll mention to patients to try and educate them and get them to be agreeable for placement.” (Social worker, University hospital)

Clinicians avoided negative associations with “nursing home” (even though all SNFs are nursing homes) and tended to use more positive frames such as “rehabilitation facility.”

“Use the word rehab….we definitely use the word rehab, to get more therapy, to go home; it’s not a, we really emphasize it’s not a nursing home, it’s not to go to stay forever.” (Physical therapist, safety-net hospital)

Clinicians used a frame of “safety” when discussing the SNF and used a frame of “risk” when discussing alternative postacute care options such as returning home. We did not find examples of clinicians discussing similar risks in going to a SNF even for risks, such as falling, which exist in both settings.

“I’ve talked to them primarily on an avenue of safety because I think people want and they value independence, they value making sure they can get home, but you know, a lot of the times they understand safety is, it can be a concern and outlining that our goal is to make sure that they’re safe and they stay home, and I tend to broach the subject saying that our therapists believe that they might not be safe at home in the moment, but they have potential goals to be safe later on if we continue therapy. I really highlight safety being the major driver of our discussion.” (Physician, VA hospital)

In some cases, framing was so overt that other risk-mitigating options (eg, home healthcare) are not discussed.

“I definitely tend to explain the ideal first. I’m not going to bring up home care when we really think somebody should go to rehab, however, once people say I don’t want to do that, I’m not going, then that’s when I’m like OK, well, let’s talk to the doctors, but we can see about other supports in the home.” (Social worker, VA hospital)

DISCUSSION

In a large sample of patients and their caregivers, as well as multidisciplinary clinicians at three different hospitals and three SNFs, we found authority bias/halo effect and framing biases were most common and seemed most impactful. Default/status quo bias and anchoring bias were also present in decision-making about a SNF. The combination of authority bias/halo effect and framing biases could synergistically interact to augment the likelihood of patients accepting a SNF for postacute care. Patients who had been to a SNF before seemed more likely to choose the SNF they had experienced previously even if they had no other postacute care experiences, and could be highly influenced by isolated characteristics of that facility (such as the physical environment or cost of care).

It is important to mention that cognitive biases do not necessarily have a negative impact: indeed, as Kahneman and Tversky point out, these are useful heuristics from “fast” thinking that are often effective.24 For example, clinicians may be trying to act in the best interests of the patient when framing the decision in terms of regaining function and averting loss of safety and independence. However, the evidence base regarding the outcomes of an SNF versus other postacute options is not robust, and this decision-making is complex. While this decision was most commonly framed in terms of rehabilitation and returning home, the fact that only about half of patients have returned to the community by 100 days4 was not discussed in any interview. In fact, initial evidence suggests replacing the SNF with home healthcare in patients with hip and knee arthroplasty may reduce costs without worsening clinical outcomes.6 However, across a broader population, SNFs significantly reduce 30-day readmissions when directly compared with home healthcare, but other clinical outcomes are similar.25 This evidence suggests that the “right” postacute care option for an individual patient is not clear, highlighting a key role biases may play in decision-making. Further, the nebulous concept of “safety” could introduce potential disparities related to social determinants of health.12 The observed inclination to accept an SNF with which the individual had prior experience may be influenced by the acceptability of this choice because of personal factors or prior research, even if it also represents a bias by limiting the consideration of current alternatives.

Our findings complement those of others in the literature which have also identified profound gaps in discharge decision-making among patients and clinicians,13-16,26-31 though to our knowledge the role of cognitive biases in these decisions has not been explored. This study also addresses gaps in the cognitive bias literature, including the need for real-world data rather than hypothetical vignettes,17 and evaluation of treatment and management decisions rather than diagnoses, which have been more commonly studied.21

These findings have implications for both individual clinicians and healthcare institutions. In the immediate term, these findings may serve as a call to discharging clinicians to modulate language and “debias” their conversations with patients about care after discharge.18,22 Shared decision-making requires an informed choice by patients based on their goals and values; framing a decision in a way that puts the clinician’s goals or values (eg, safety) ahead of patient values (eg, independence and autonomy) or limits disclosure (eg, a “rehab” is a nursing home) in the hope of influencing choice may be more consistent with framing bias and less with shared decision-making.14 Although controversy exists about the best way to “debias” oneself,32 self-awareness of bias is increasingly recognized across healthcare venues as critical to improving care for vulnerable populations.33 The use of data rather than vignettes may be a useful debiasing strategy, although the limitations of currently available data (eg, capturing nursing home quality) are increasingly recognized.34 From a policy and health system perspective, cognitive biases should be integrated into the development of decision aids to facilitate informed, shared, and high-quality decision-making that incorporates patient values, and perhaps “nudges” from behavioral economics to assist patients in choosing the right postdischarge care for them. Such nudges use principles of framing to influence care without restricting choice.35 As the science informing best practice regarding postacute care improves, identifying the “right” postdischarge care may become easier and recommendations more evidence-based.36

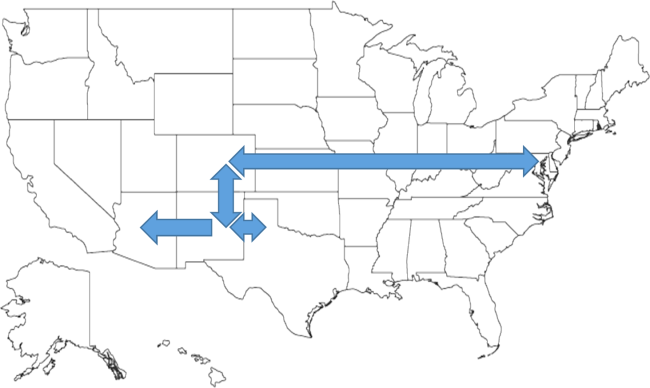

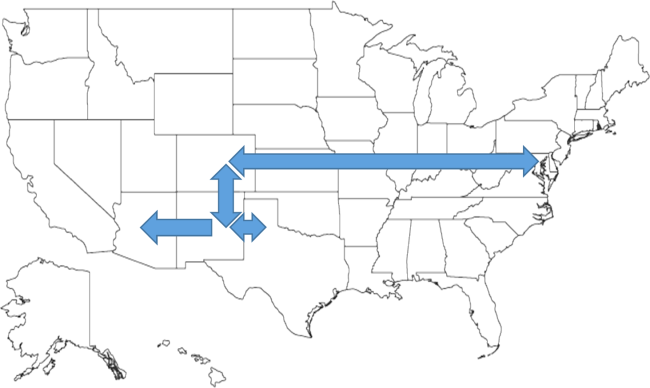

Strengths of the study include a large, diverse sample of patients, caregivers, and clinicians in both the hospital and SNF setting. Also, we used a team-based analysis with an experienced team and a deep knowledge of the data, including triangulation with clinicians to verify results. However, all hospitals and SNFs were located in a single metropolitan area, and responses may vary by region or population density. All three hospitals have housestaff teaching programs, and at the time of the interviews all three community SNFs were “five-star” facilities on the Nursing Home Compare website; results may be different at community hospitals or other SNFs. Hospitalists were the only physician group sampled in the hospital as they provide the majority of inpatient care to older adults; geriatricians, in particular, may have had different perspectives. Since we intended to explore whether cognitive biases were present overall, we did not evaluate whether cognitive biases differed by role or subgroup (by clinician type, patient, or caregiver), but this may be a promising area to explore in future work. Many cognitive biases have been described, and there are likely additional biases we did not identify. To confirm the generalizability of these findings, they should be studied in a larger, more generalizable sample of respondents in future work.

Cognitive biases play an important role in patient decision-making about postacute care, particularly regarding SNF care. As postacute care undergoes a transformation spurred by payment reforms, it is more important than ever to ensure that patients understand their choices at hospital discharge and can make a high-quality decision consistent with their goals.

The combination of decreasing hospital lengths of stay and increasing age and comorbidity of the United States population is a principal driver of the increased use of postacute care in the US.1-3 Postacute care refers to care in long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and care provided by home health agencies after an acute hospitalization. In 2016, 43% of Medicare beneficiaries received postacute care after hospital discharge at the cost of $60 billion annually; nearly half of these received care in an SNF.4 Increasing recognition of the significant cost and poor outcomes of postacute care led to payment reforms, such as bundled payments, that incentivized less expensive forms of postacute care and improvements in outcomes.5-9 Early evaluations suggested that hospitals are sensitive to these reforms and responded by significantly decreasing SNF utilization.10,11 It remains unclear whether this was safe and effective.

In this context, increased attention to how hospital clinicians and hospitalized patients decide whether to use postacute care (and what form to use) is appropriate since the effect of payment reforms could negatively impact vulnerable populations of older adults without adequate protection.12 Suboptimal decision-making can drive both overuse and inappropriate underuse of this expensive medical resource. Initial evidence suggests that patients and clinicians are poorly equipped to make high-quality decisions about postacute care, with significant deficits in both the decision-making process and content.13-16 While these gaps are important to address, they may only be part of the problem. The fields of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics have revealed new insights into decision-making, demonstrating that people deviate from rational decision-making in predictable ways, termed decision heuristics, or cognitive biases.17 This growing field of research suggests heuristics or biases play important roles in decision-making and determining behavior, particularly in situations where there may be little information provided and the patient is stressed, tired, and ill—precisely like deciding on postacute care.18 However, it is currently unknown whether cognitive biases are at play when making hospital discharge decisions.

We sought to identify the most salient heuristics or cognitive biases patients may utilize when making decisions about postacute care at the end of their hospitalization and ways clinicians may contribute to these biases. The overall goal was to derive insights for improving postacute care decision-making.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a secondary analysis on interviews with hospital and SNF clinicians as well as patients and their caregivers who were either leaving the hospital for an SNF or newly arrived in an SNF from the hospital to understand if cognitive biases were present and how they manifested themselves in a real-world clinical context.19 These interviews were part of a larger qualitative study that sought to understand how clinicians, patients, and their caregivers made decisions about postacute care, particularly related to SNFs.13,14 This study represents the analysis of all our interviews, specifically examining decision-making bias. Participating sites, clinical roles, and both patient and caregiver characteristics (Table 1) in our cohort have been previously described.13,14

Analysis

We used a team-based approach to framework analysis, which has been used in other decision-making studies14, including those measuring cognitive bias.20 A limitation in cognitive bias research is the lack of a standardized list or categorization of cognitive biases. We reviewed prior systematic17,21 and narrative reviews18,22, as well as prior studies describing examples of cognitive biases playing a role in decision-making about therapy20 to construct a list of possible cognitive biases to evaluate and narrow these a priori to potential biases relevant to the decision about postacute care based on our prior work (Table 2).

We applied this framework to analyze transcripts through an iterative process of deductive coding and reviewing across four reviewers (ML, RA, AL, CL) and a hospitalist physician with expertise leading qualitative studies (REB).

Intercoder consensus was built through team discussion by resolving points of disagreement.23 Consistency of coding was regularly checked by having more than one investigator code individual manuscripts and comparing coding, and discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. We triangulated the data (shared our preliminary results) using a larger study team, including an expert in behavioral economics (SRG), physicians at study sites (EC, RA), and an anthropologist with expertise in qualitative methods (CL). We did this to ensure credibility (to what extent the findings are credible or believable) and confirmability of findings (ensuring the findings are based on participant narratives rather than researcher biases).

RESULTS

We reviewed a total of 105 interviews with 25 hospital clinicians, 20 SNF clinicians, 21 patients and 14 caregivers in the hospital, and 15 patients and 10 caregivers in the SNF setting (Table 1). We found authority bias/halo effect; default/status quo bias, anchoring bias, and framing was commonly present in decision-making about postacute care in a SNF, whereas there were few if any examples of ambiguity aversion, availability heuristic, confirmation bias, optimism bias, or false consensus effect (Table 2).

Authority Bias/Halo Effect

While most patients deferred to their inpatient teams when it came to decision-making, this effect seemed to differ across VA and non-VA settings. Veterans expressed a higher degree of potential authority bias regarding the VA as an institution, whereas older adults in non-VA settings saw physicians as the authority figure making decisions in their best interests.

Veterans expressed confidence in the VA regarding both whether to go to a SNF and where to go:

“The VA wouldn’t license [an SNF] if they didn’t have a good reputation for care, cleanliness, things of that nature” (Veteran, VA CLC)

“I just knew the VA would have my best interests at heart” (Veteran, VA CLC)

Their caregivers expressed similar confidence:

“I’m not gonna decide [on whether the patient they care for goes to postacute care], like I told you, that’s totally up to the VA. I have trust and faith in them…so wherever they send him, that’s where he’s going” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In some cases, this perspective was closer to the halo effect: a positive experience with the care provider or the care team led the decision-makers to believe that their recommendations about postacute care would be similarly positive.

“I think we were very trusting in the sense that whatever happened the last time around, he survived it…they took care of him…he got back home, and he started his life again, you know, so why would we question what they’re telling us to do? (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In contrast to Veterans, non-Veteran patients seemed to experience authority bias when it came to the inpatient team.

“Well, I’d like to know more about the PTs [Physical Therapists] there, but I assume since they were recommended, they will be good.” (Patient, University hospital)

This perspective was especially apparent when it came to physicians:

“The level of trust that they [patients] put in their doctor is gonna outweigh what anyone else would say.” (Clinical liaison, SNF)

“[In response to a question about influences on the decision to go to rehab] I don’t…that’s not my decision to make, that’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

“They said so…[the doctor] said I needed to go to rehab, so I guess I do because it’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

Default/Status quo Bias

In a related way, patients and caregivers with exposure to a SNF seemed to default to the same SNF with which they had previous experience. This bias seems to be primarily related to knowing what to expect.

“He thinks it’s [a particular SNF] the right place for him now…he was there before and he knew, again, it was the right place for him to be” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

“It’s the only one I’ve ever been in…but they have a lot of activities; you have a lot of freedom, staff was good” (Patient, VA hospital)

“I’ve been [to this SNF] before and I kind of know what the program involves…so it was kind of like going home, not, going home is the wrong way to put it…I mean coming here is like something I know, you know, I didn’t need anybody to explain it to me.” (Patient, VA hospital)

“Anybody that’s been to [SNF], that would be their choice to go back to, and I guess I must’ve liked it that first time because I asked to go back again.” (Patient, University hospital)

Anchoring Bias

While anchoring bias was less frequent, it came up in two domains: first, related to costs of care, and second, related to facility characteristics. Costs came up most frequently for Veterans who preferred to move their care to the VA for cost reasons, which appeared in these cases to overshadow other considerations:

“I kept emphasizing that the VA could do all the same things at a lot more reasonable price. The whole purpose of having the VA is for the Veteran, so that…we can get the healthcare that we need at a more reasonable [sic] or a reasonable price.” (Veteran, CLC)

“I think the CLC [VA SNF] is going to take care of her probably the same way any other facility of its type would, unless she were in a private facility, but you know, that costs a lot more money.” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

Patients occasionally had striking responses to particular characteristics of SNFs, regardless of whether this was a central feature or related to their rehabilitation:

“The social worker comes and talks to me about the nursing home where cats are running around, you know, to infect my leg or spin their little cat hairs into my lungs and make my asthma worse…I’m going to have to beg the nurses or the aides or the family or somebody to clean the cat…” (Veteran, VA hospital)

Framing

Framing was the strongest theme among clinician interviews in our sample. Clinicians most frequently described the SNF as a place where patients could recover function (a positive frame), explaining risks (eg, rehospitalization) associated with alternative postacute care options besides the SNF in great detail.

“Aside from explaining the benefits of going and…having that 24-hour care, having the therapies provided to them [the patients], talking about them getting stronger, phrasing it in such a way that patients sometimes are more agreeable, like not calling it a skilled nursing facility, calling it a rehab you know, for them to get physically stronger so they can be the most independent that they can once they do go home, and also explaining … we think that this would be the best plan to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, so those are some of the things that we’ll mention to patients to try and educate them and get them to be agreeable for placement.” (Social worker, University hospital)

Clinicians avoided negative associations with “nursing home” (even though all SNFs are nursing homes) and tended to use more positive frames such as “rehabilitation facility.”

“Use the word rehab….we definitely use the word rehab, to get more therapy, to go home; it’s not a, we really emphasize it’s not a nursing home, it’s not to go to stay forever.” (Physical therapist, safety-net hospital)

Clinicians used a frame of “safety” when discussing the SNF and used a frame of “risk” when discussing alternative postacute care options such as returning home. We did not find examples of clinicians discussing similar risks in going to a SNF even for risks, such as falling, which exist in both settings.

“I’ve talked to them primarily on an avenue of safety because I think people want and they value independence, they value making sure they can get home, but you know, a lot of the times they understand safety is, it can be a concern and outlining that our goal is to make sure that they’re safe and they stay home, and I tend to broach the subject saying that our therapists believe that they might not be safe at home in the moment, but they have potential goals to be safe later on if we continue therapy. I really highlight safety being the major driver of our discussion.” (Physician, VA hospital)

In some cases, framing was so overt that other risk-mitigating options (eg, home healthcare) are not discussed.

“I definitely tend to explain the ideal first. I’m not going to bring up home care when we really think somebody should go to rehab, however, once people say I don’t want to do that, I’m not going, then that’s when I’m like OK, well, let’s talk to the doctors, but we can see about other supports in the home.” (Social worker, VA hospital)

DISCUSSION

In a large sample of patients and their caregivers, as well as multidisciplinary clinicians at three different hospitals and three SNFs, we found authority bias/halo effect and framing biases were most common and seemed most impactful. Default/status quo bias and anchoring bias were also present in decision-making about a SNF. The combination of authority bias/halo effect and framing biases could synergistically interact to augment the likelihood of patients accepting a SNF for postacute care. Patients who had been to a SNF before seemed more likely to choose the SNF they had experienced previously even if they had no other postacute care experiences, and could be highly influenced by isolated characteristics of that facility (such as the physical environment or cost of care).

It is important to mention that cognitive biases do not necessarily have a negative impact: indeed, as Kahneman and Tversky point out, these are useful heuristics from “fast” thinking that are often effective.24 For example, clinicians may be trying to act in the best interests of the patient when framing the decision in terms of regaining function and averting loss of safety and independence. However, the evidence base regarding the outcomes of an SNF versus other postacute options is not robust, and this decision-making is complex. While this decision was most commonly framed in terms of rehabilitation and returning home, the fact that only about half of patients have returned to the community by 100 days4 was not discussed in any interview. In fact, initial evidence suggests replacing the SNF with home healthcare in patients with hip and knee arthroplasty may reduce costs without worsening clinical outcomes.6 However, across a broader population, SNFs significantly reduce 30-day readmissions when directly compared with home healthcare, but other clinical outcomes are similar.25 This evidence suggests that the “right” postacute care option for an individual patient is not clear, highlighting a key role biases may play in decision-making. Further, the nebulous concept of “safety” could introduce potential disparities related to social determinants of health.12 The observed inclination to accept an SNF with which the individual had prior experience may be influenced by the acceptability of this choice because of personal factors or prior research, even if it also represents a bias by limiting the consideration of current alternatives.

Our findings complement those of others in the literature which have also identified profound gaps in discharge decision-making among patients and clinicians,13-16,26-31 though to our knowledge the role of cognitive biases in these decisions has not been explored. This study also addresses gaps in the cognitive bias literature, including the need for real-world data rather than hypothetical vignettes,17 and evaluation of treatment and management decisions rather than diagnoses, which have been more commonly studied.21

These findings have implications for both individual clinicians and healthcare institutions. In the immediate term, these findings may serve as a call to discharging clinicians to modulate language and “debias” their conversations with patients about care after discharge.18,22 Shared decision-making requires an informed choice by patients based on their goals and values; framing a decision in a way that puts the clinician’s goals or values (eg, safety) ahead of patient values (eg, independence and autonomy) or limits disclosure (eg, a “rehab” is a nursing home) in the hope of influencing choice may be more consistent with framing bias and less with shared decision-making.14 Although controversy exists about the best way to “debias” oneself,32 self-awareness of bias is increasingly recognized across healthcare venues as critical to improving care for vulnerable populations.33 The use of data rather than vignettes may be a useful debiasing strategy, although the limitations of currently available data (eg, capturing nursing home quality) are increasingly recognized.34 From a policy and health system perspective, cognitive biases should be integrated into the development of decision aids to facilitate informed, shared, and high-quality decision-making that incorporates patient values, and perhaps “nudges” from behavioral economics to assist patients in choosing the right postdischarge care for them. Such nudges use principles of framing to influence care without restricting choice.35 As the science informing best practice regarding postacute care improves, identifying the “right” postdischarge care may become easier and recommendations more evidence-based.36

Strengths of the study include a large, diverse sample of patients, caregivers, and clinicians in both the hospital and SNF setting. Also, we used a team-based analysis with an experienced team and a deep knowledge of the data, including triangulation with clinicians to verify results. However, all hospitals and SNFs were located in a single metropolitan area, and responses may vary by region or population density. All three hospitals have housestaff teaching programs, and at the time of the interviews all three community SNFs were “five-star” facilities on the Nursing Home Compare website; results may be different at community hospitals or other SNFs. Hospitalists were the only physician group sampled in the hospital as they provide the majority of inpatient care to older adults; geriatricians, in particular, may have had different perspectives. Since we intended to explore whether cognitive biases were present overall, we did not evaluate whether cognitive biases differed by role or subgroup (by clinician type, patient, or caregiver), but this may be a promising area to explore in future work. Many cognitive biases have been described, and there are likely additional biases we did not identify. To confirm the generalizability of these findings, they should be studied in a larger, more generalizable sample of respondents in future work.

Cognitive biases play an important role in patient decision-making about postacute care, particularly regarding SNF care. As postacute care undergoes a transformation spurred by payment reforms, it is more important than ever to ensure that patients understand their choices at hospital discharge and can make a high-quality decision consistent with their goals.

1. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post-acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):295-296. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6383.

2. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Patient and hospitalization characteristics associated with increased postacute care facility discharges from US hospitals. Med Care. 2015;53(6):492-500. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000359.

3. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408.

4. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission June 2018 Report to Congress. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_ch5_medpacreport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 9, 2018.

5. Burke RE, Cumbler E, Coleman EA, Levy C. Post-acute care reform: implications and opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):46-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2673.

6. Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.12717.

7. Navathe AS, Troxel AB, Liao JM, et al. Cost of joint replacement using bundled payment models. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):214-222. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8263.

8. Kennedy G, Lewis VA, Kundu S, Mousqués J, Colla CH. Accountable care organizations and post-acute care: a focus on preferred SNF networks. Med Care Res Rev MCRR. 2018;1077558718781117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558718781117.

9. Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2013;32(5):864-872. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1262.

10. McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare shared savings program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):518-526. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9115.

11. Zhu JM, Patel V, Shea JA, Neuman MD, Werner RM. Hospitals using bundled payment report reducing skilled nursing facility use and improving care integration. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2018;37(8):1282-1289. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0257.

12. Burke RE, Ibrahim SA. Discharge destination and disparities in postoperative care. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1653-1654. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21884.

13. Burke RE, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, et al. How hospital clinicians select patients for skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2466-2472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14954.

14. Burke RE, Jones J, Lawrence E, et al. Evaluating the quality of patient decision-making regarding post-acute care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):678-684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4298-1.

15. Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Mor V. Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: individual and family perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2459-2465. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14988.

16. Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, Shield RR, Winblad U, Mor V. Patients are not given quality-of-care data about skilled nursing facilities when discharged from hospitals. Health Aff. 2017;36(8):1385-1391. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0155.

17. Blumenthal-Barby JS, Krieger H. Cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decision making: a critical review using a systematic search strategy. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2015;35(4):539-557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X14547740.

18. Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii58-ii64. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001712.

19. Hinds PS, Vogel RJ, Clarke-Steffen L. The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qual Health Res. 1997;7(3):408-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239700700306.

20. Magid M, Mcllvennan CK, Jones J, et al. Exploring cognitive bias in destination therapy left ventricular assist device decision making: a retrospective qualitative framework analysis. Am Heart J. 2016;180:64-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.06.024.

21. Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1.

22. Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 2: impediments to and strategies for change. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii65-ii72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001713.

23. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x.

24. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Daniel Kahneman. Macmillan. US Macmillan. https://us.macmillan.com/thinkingfastandslow/danielkahneman/9780374533557. Accessed February 5, 2019.

25. Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Coe NB. Does type of post-acute care matter? The effect of hospital discharge to home with home health care versus to skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern Med. In press.

26. Jones J, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, Leonard C, Ayele R, Burke RE. Nurses’ role in managing “The Fit” of older adults in skilled nursing facilities. J Gerontol Nurs. 2017;43(12):11-20. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20171110-06.

27. Lawrence E, Casler J-J, Jones J, et al. Variability in skilled nursing facility screening and admission processes: implications for value-based purchasing. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000225.

28. Ayele R, Jones J, Ladebue A, et al. Perceived costs of care influence post-acute care choices by clinicians, patients, and caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15768.

29. Sefcik JS, Nock RH, Flores EJ, et al. Patient preferences for information on post-acute care services. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(4):175-182. https://doi.org/10.3928/19404921-20160120-01.

30. Konetzka RT, Perraillon MC. Use of nursing home compare website appears limited by lack of awareness and initial mistrust of the data. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2016;35(4):706-713. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1377.

31. Schapira MM, Shea JA, Duey KA, Kleiman C, Werner RM. The nursing home compare report card: perceptions of residents and caregivers regarding quality ratings and nursing home choice. Health Serv Res. 2016;51 Suppl 2:1212-1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12458.

32. Dhaliwal G. Premature closure? Not so fast. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(2):87-89. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005267.

33. Masters C, Robinson D, Faulkner S, Patterson E, McIlraith T, Ansari A. Addressing biases in patient care with the 5Rs of cultural humility, a clinician coaching tool. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):627-630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4814-y.

34. Burke RE, Werner RM. Quality measurement and nursing homes: measuring what matters. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(7);520-523. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009447.

35. Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Nudge units to improve the delivery of health care. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(3):214-216. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1712984.

36. Jenq GY, Tinetti ME. Post–acute care: who belongs where? JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):296-297. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4298.

1. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post-acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):295-296. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6383.

2. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Patient and hospitalization characteristics associated with increased postacute care facility discharges from US hospitals. Med Care. 2015;53(6):492-500. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000359.

3. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408.

4. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission June 2018 Report to Congress. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_ch5_medpacreport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 9, 2018.

5. Burke RE, Cumbler E, Coleman EA, Levy C. Post-acute care reform: implications and opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):46-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2673.

6. Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.12717.

7. Navathe AS, Troxel AB, Liao JM, et al. Cost of joint replacement using bundled payment models. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):214-222. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8263.

8. Kennedy G, Lewis VA, Kundu S, Mousqués J, Colla CH. Accountable care organizations and post-acute care: a focus on preferred SNF networks. Med Care Res Rev MCRR. 2018;1077558718781117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558718781117.

9. Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2013;32(5):864-872. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1262.

10. McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare shared savings program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):518-526. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9115.

11. Zhu JM, Patel V, Shea JA, Neuman MD, Werner RM. Hospitals using bundled payment report reducing skilled nursing facility use and improving care integration. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2018;37(8):1282-1289. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0257.

12. Burke RE, Ibrahim SA. Discharge destination and disparities in postoperative care. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1653-1654. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21884.

13. Burke RE, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, et al. How hospital clinicians select patients for skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2466-2472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14954.

14. Burke RE, Jones J, Lawrence E, et al. Evaluating the quality of patient decision-making regarding post-acute care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):678-684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4298-1.

15. Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Mor V. Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: individual and family perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2459-2465. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14988.

16. Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, Shield RR, Winblad U, Mor V. Patients are not given quality-of-care data about skilled nursing facilities when discharged from hospitals. Health Aff. 2017;36(8):1385-1391. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0155.

17. Blumenthal-Barby JS, Krieger H. Cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decision making: a critical review using a systematic search strategy. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2015;35(4):539-557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X14547740.

18. Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii58-ii64. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001712.

19. Hinds PS, Vogel RJ, Clarke-Steffen L. The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qual Health Res. 1997;7(3):408-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239700700306.

20. Magid M, Mcllvennan CK, Jones J, et al. Exploring cognitive bias in destination therapy left ventricular assist device decision making: a retrospective qualitative framework analysis. Am Heart J. 2016;180:64-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.06.024.

21. Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1.

22. Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 2: impediments to and strategies for change. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii65-ii72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001713.

23. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x.

24. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Daniel Kahneman. Macmillan. US Macmillan. https://us.macmillan.com/thinkingfastandslow/danielkahneman/9780374533557. Accessed February 5, 2019.