User login

Blood Products Provided to Patients Receiving Futile Critical Care

Critical care physicians frequently find themselves providing care that they find to be futile or inappropriate for hospitalized critically ill patients. A survey of physicians found that 87% felt that “futile” treatment was provided in their intensive care unit (ICU) in the past year.1 In a single-day cross-sectional study, 27% of ICU clinicians reported providing inappropriate care to at least 1 patient, most of which was excessive.2 In a 3-month study, 11% of all ICU patients were perceived by their physician as receiving futile treatment at some point during their ICU hospitalization.3 Given that more than 1 in 5 decedents die after an ICU stay during a terminal admission, there is increasing scrutiny of the ICU as a setting where potentially inappropriate resource-intensive treatment is provided.4-6 Blood is an especially valuable resource, not only because it exists in finite supply (and is sometimes in shortage) but also because it is donated in ways that arguably create special stewardship expectations and responsibilities for those trusted to make decisions about its use. The amount of blood products used for patients who are perceived to be receiving inappropriate critical care has not been quantified.

Blood transfusion is the most frequently performed inpatient procedure, occurring in more than 10% of hospital admissions that involve a procedure.7 When used appropriately, the transfusion of blood products can be lifesaving; however, studies show that some transfused blood might not be needed and efforts are afoot to improve the match between transfusion and transfusion need.8,9 These efforts largely focus on generating guidelines based on physiologic benefit and aim mainly at promoting a restrictive transfusion protocol by avoiding blood product use for patients who will likely do well even without transfusion.8,10-12 The guiding principle behind efforts to improve the stewardship of scarce blood products is that they should only be used if they will make a difference in patient outcomes. Unlike prior studies, the goal of this study is to quantify the amount of blood products administered to patients who would do poorly with or without receipt of blood products, that is, patients perceived by their physicians as receiving futile critical care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Based on a focus group discussion with physicians who cared for critically ill patients, a questionnaire was developed to identify patients perceived as receiving futile critical care. Details of the definition of futile treatment and the core data collection are described in detail elsewhere.3

For each ICU patient under the physician’s care, the attending physician completed a daily questionnaire asking whether the patient was receiving futile treatment, probably futile treatment, or nonfutile treatment. These surveys were administered every day from December 15, 2011, through March 15, 2012, to each critical care specialist providing care in 5 ICUs (medical ICU, neurocritical care ICU, cardiac care unit, cardiothoracic ICU, and a mixed medical-surgical ICU) in 1 academic health system. All clinicians provided informed consent.

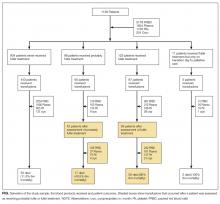

Patients were categorized into the following 3 groups: patients for whom treatment was never perceived as futile; patients with at least 1 assessment that treatment was probably futile, but no futile treatment assessments; and patients who had at least 1 assessment of futile treatment. Hospital and 6-month mortality was abstracted for all patients.

The Division of Transfusion Medicine provided a database of all adult patients during the 3-month study period who received a transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), apheresis platelets, plasma, or cryoprecipitate (5 unit prepooled units). This database was merged with the daily assessments of the appropriateness of critical care. To determine the proportion of blood products that was utilized for patients receiving inappropriate treatment, we tallied the blood products infused to these patients after the day the patient was assessed as receiving probably inappropriate or inappropriate treatment. The denominator was the total amount of blood products used by all assessed patients during the 3-month study period.

This study was approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

During the 3-month study period, 36 critical care clinicians in 5 ICUs provided care to 1193 adult patients. After excluding boarders in the ICUs and missed and invalid assessments, 6916 assessments were made on 1136 patients. Of these 1136 patients, 98 (8.6%) patients received probably futile treatment and 123 (11%) patients received futile treatment according to the physicians caring for them.

For patients who were never rated as receiving futile treatment, the in-hospital mortality was 4.6% and the 6-month mortality was 7.3%. On the contrary, 68% of the patients who were perceived to receive futile ICU treatment died before hospital discharge and 85% died within 6 months; survivors remained in severely compromised health states.3

DISCUSSION

Blood and blood products are donated resources. These biological products are altruistically given with the expectation that they will be used to benefit others.13 It is the clinicians’ responsibility to use these precious gifts to achieve the goals of medicine, which include curing, preserving function, and preventing clinical deterioration that has meaning to the patient. Our study shows that a small, but not insignificant, proportion of these donated resources are provided to hospitalized patients who are perceived as receiving futile critical care. That means that these transfusions are used as part of the critical care interventions that prolong the dying process and achieve outcomes, such as existence in coma, which few, if any, patients would desire. However, it should be noted that some of the health states preserved, such as neurological devastation or multi-organ failure with an inability to survive outside an ICU, were likely desired by patients’ families and might even have been desired by patients themselves. Whether blood donors would wish to donate blood to preserve life in such compromised health states is testable. This proportion of blood provided to ICU patients perceived as receiving futile treatment (7.6%) is similar to or greater than that lost due to wastage, which ranges from 0.1% to 6.7%.14 While the loss of this small proportion of blood products due to expiration or procedural issues is probably unavoidable, but should be minimized as much as possible, the provision of blood products to patients receiving futile critical care is under the control of the healthcare team. This raises the question of how altruistic blood donors would feel about donating if they were aware that 1 of every 13 units transfused in the ICU would be given to a patient that the physician feels will not benefit. In turn, it raises the question of whether the physician should refrain from using these blood products for patients who will not benefit in accordance with principles of evidence-based medicine, in order to ensure their availability for patients that will benefit.

This study has several limitations. Family/patient perspectives were not included in the assessment of futile treatment. It should also be recognized that the percentage of blood products provided to patients receiving inappropriate critical care is likely an underestimate as only blood product use during the 3-month study period was included, as many of these patients were admitted to the ICU prior the study period, and/or remained in the ICU or hospital after this window.

CONCLUSIONS

Similar to other treatments provided to patients who are perceived to receive futile critical care, blood products represent a healthcare resource that has the potential to be used without achieving the goals of medicine. But unlike many other medical treatments, the ability to maintain an adequate blood supply for transfusion relies on altruistic blood donors, individuals who are simply motivated by a desire to achieve a healthcare good.13 Explicit guidelines on the use of blood products should be developed to ensure that the use of this precious resource achieves meaningful goals. These goals need to be transparently defined such that a physician’s decision to not transfuse is expected as part of evidence-based medicine. Empiric research, educational interventions, and clearly delineated conflict-resolution processes may improve clinicians’ ability to handle these difficult cases.15

Disclosure

T. Neville was supported by the UCLA CTSI KL2 UL1TR000124, the NIH-NIA 1K23AG047900 - 01A1, and the NIH Loan Repayment Program grant. This project was supported by a donation from Mary Kay Farley to RAND Health. The funder played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Palda VA, Bowman KW, McLean RF, Chapman MG. “Futile” care: do we provide it? Why? A semistructured, Canada-wide survey of intensive care unit doctors and nurses. J Crit Care. 2005;20:207-213. PubMed

2. Piers RD, Azoulay E, Ricou B, et al. Perceptions of appropriateness of care among European and Israeli intensive care unit nurses and physicians. JAMA. 2011;306:2694-2703. PubMed

3. Huang S, Dang H, Huynh W, Sambrook PJ, Goss AN. The healing of dental extraction sockets in patients with Type 2 diabetes on oral hypoglycaemics: a prospective cohort. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:89-93. PubMed

4. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638-643. PubMed

5. Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Harrison DA, Barnato AE, Rowan KM, Angus DC. Use of intensive care services during terminal hospitalizations in England and the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:875-880. PubMed

6. Esserman L, Belkora J, Lenert L. Potentially ineffective care. A new outcome to assess the limits of critical care. JAMA. 1995;274:1544-1551. PubMed

7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: HCUP facts and figures: statistics on hospital-based care in the United States. 2009. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/factsandfigures/2009/TOC_2009.jsp. Accessed July 15, 2016.

8. Goodnough LT, Maggio P, Hadhazy E, et al. Restrictive blood transfusion practices are associated with improved patient outcomes. Transfusion. 2014;54:2753-2759. PubMed

9. Shander AS, Goodnough LT. Blood transfusion as a quality indicator in cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2010;304:1610-1611. PubMed

10. Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417. PubMed

11. Morton J, Anastassopoulos KP, Patel ST, et al. Frequency and outcomes of blood products transfusion across procedures and clinical conditions warranting inpatient care: an analysis of the 2004 healthcare cost and utilization project nationwide inpatient sample database. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:289-296. PubMed

12. Shander A, Fink A, Javidroozi M, et al. Appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: the international consensus conference on transfusion outcomes. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:232-246 e53. PubMed

13. Bednall TC, Bove LL. Donating blood: a meta-analytic review of self-reported motivators and deterrents. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:317-334. PubMed

14. Heitmiller ES, Hill RB, Marshall CE, et al. Blood wastage reduction using Lean Sigma methodology. Transfusion. 2010;50:1887-1896. PubMed

15. Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. An Official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM Policy Statement: Responding to Requests for Potentially Inappropriate Treatments in Intensive Care Units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1318-1330. PubMed

Critical care physicians frequently find themselves providing care that they find to be futile or inappropriate for hospitalized critically ill patients. A survey of physicians found that 87% felt that “futile” treatment was provided in their intensive care unit (ICU) in the past year.1 In a single-day cross-sectional study, 27% of ICU clinicians reported providing inappropriate care to at least 1 patient, most of which was excessive.2 In a 3-month study, 11% of all ICU patients were perceived by their physician as receiving futile treatment at some point during their ICU hospitalization.3 Given that more than 1 in 5 decedents die after an ICU stay during a terminal admission, there is increasing scrutiny of the ICU as a setting where potentially inappropriate resource-intensive treatment is provided.4-6 Blood is an especially valuable resource, not only because it exists in finite supply (and is sometimes in shortage) but also because it is donated in ways that arguably create special stewardship expectations and responsibilities for those trusted to make decisions about its use. The amount of blood products used for patients who are perceived to be receiving inappropriate critical care has not been quantified.

Blood transfusion is the most frequently performed inpatient procedure, occurring in more than 10% of hospital admissions that involve a procedure.7 When used appropriately, the transfusion of blood products can be lifesaving; however, studies show that some transfused blood might not be needed and efforts are afoot to improve the match between transfusion and transfusion need.8,9 These efforts largely focus on generating guidelines based on physiologic benefit and aim mainly at promoting a restrictive transfusion protocol by avoiding blood product use for patients who will likely do well even without transfusion.8,10-12 The guiding principle behind efforts to improve the stewardship of scarce blood products is that they should only be used if they will make a difference in patient outcomes. Unlike prior studies, the goal of this study is to quantify the amount of blood products administered to patients who would do poorly with or without receipt of blood products, that is, patients perceived by their physicians as receiving futile critical care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Based on a focus group discussion with physicians who cared for critically ill patients, a questionnaire was developed to identify patients perceived as receiving futile critical care. Details of the definition of futile treatment and the core data collection are described in detail elsewhere.3

For each ICU patient under the physician’s care, the attending physician completed a daily questionnaire asking whether the patient was receiving futile treatment, probably futile treatment, or nonfutile treatment. These surveys were administered every day from December 15, 2011, through March 15, 2012, to each critical care specialist providing care in 5 ICUs (medical ICU, neurocritical care ICU, cardiac care unit, cardiothoracic ICU, and a mixed medical-surgical ICU) in 1 academic health system. All clinicians provided informed consent.

Patients were categorized into the following 3 groups: patients for whom treatment was never perceived as futile; patients with at least 1 assessment that treatment was probably futile, but no futile treatment assessments; and patients who had at least 1 assessment of futile treatment. Hospital and 6-month mortality was abstracted for all patients.

The Division of Transfusion Medicine provided a database of all adult patients during the 3-month study period who received a transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), apheresis platelets, plasma, or cryoprecipitate (5 unit prepooled units). This database was merged with the daily assessments of the appropriateness of critical care. To determine the proportion of blood products that was utilized for patients receiving inappropriate treatment, we tallied the blood products infused to these patients after the day the patient was assessed as receiving probably inappropriate or inappropriate treatment. The denominator was the total amount of blood products used by all assessed patients during the 3-month study period.

This study was approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

During the 3-month study period, 36 critical care clinicians in 5 ICUs provided care to 1193 adult patients. After excluding boarders in the ICUs and missed and invalid assessments, 6916 assessments were made on 1136 patients. Of these 1136 patients, 98 (8.6%) patients received probably futile treatment and 123 (11%) patients received futile treatment according to the physicians caring for them.

For patients who were never rated as receiving futile treatment, the in-hospital mortality was 4.6% and the 6-month mortality was 7.3%. On the contrary, 68% of the patients who were perceived to receive futile ICU treatment died before hospital discharge and 85% died within 6 months; survivors remained in severely compromised health states.3

DISCUSSION

Blood and blood products are donated resources. These biological products are altruistically given with the expectation that they will be used to benefit others.13 It is the clinicians’ responsibility to use these precious gifts to achieve the goals of medicine, which include curing, preserving function, and preventing clinical deterioration that has meaning to the patient. Our study shows that a small, but not insignificant, proportion of these donated resources are provided to hospitalized patients who are perceived as receiving futile critical care. That means that these transfusions are used as part of the critical care interventions that prolong the dying process and achieve outcomes, such as existence in coma, which few, if any, patients would desire. However, it should be noted that some of the health states preserved, such as neurological devastation or multi-organ failure with an inability to survive outside an ICU, were likely desired by patients’ families and might even have been desired by patients themselves. Whether blood donors would wish to donate blood to preserve life in such compromised health states is testable. This proportion of blood provided to ICU patients perceived as receiving futile treatment (7.6%) is similar to or greater than that lost due to wastage, which ranges from 0.1% to 6.7%.14 While the loss of this small proportion of blood products due to expiration or procedural issues is probably unavoidable, but should be minimized as much as possible, the provision of blood products to patients receiving futile critical care is under the control of the healthcare team. This raises the question of how altruistic blood donors would feel about donating if they were aware that 1 of every 13 units transfused in the ICU would be given to a patient that the physician feels will not benefit. In turn, it raises the question of whether the physician should refrain from using these blood products for patients who will not benefit in accordance with principles of evidence-based medicine, in order to ensure their availability for patients that will benefit.

This study has several limitations. Family/patient perspectives were not included in the assessment of futile treatment. It should also be recognized that the percentage of blood products provided to patients receiving inappropriate critical care is likely an underestimate as only blood product use during the 3-month study period was included, as many of these patients were admitted to the ICU prior the study period, and/or remained in the ICU or hospital after this window.

CONCLUSIONS

Similar to other treatments provided to patients who are perceived to receive futile critical care, blood products represent a healthcare resource that has the potential to be used without achieving the goals of medicine. But unlike many other medical treatments, the ability to maintain an adequate blood supply for transfusion relies on altruistic blood donors, individuals who are simply motivated by a desire to achieve a healthcare good.13 Explicit guidelines on the use of blood products should be developed to ensure that the use of this precious resource achieves meaningful goals. These goals need to be transparently defined such that a physician’s decision to not transfuse is expected as part of evidence-based medicine. Empiric research, educational interventions, and clearly delineated conflict-resolution processes may improve clinicians’ ability to handle these difficult cases.15

Disclosure

T. Neville was supported by the UCLA CTSI KL2 UL1TR000124, the NIH-NIA 1K23AG047900 - 01A1, and the NIH Loan Repayment Program grant. This project was supported by a donation from Mary Kay Farley to RAND Health. The funder played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Critical care physicians frequently find themselves providing care that they find to be futile or inappropriate for hospitalized critically ill patients. A survey of physicians found that 87% felt that “futile” treatment was provided in their intensive care unit (ICU) in the past year.1 In a single-day cross-sectional study, 27% of ICU clinicians reported providing inappropriate care to at least 1 patient, most of which was excessive.2 In a 3-month study, 11% of all ICU patients were perceived by their physician as receiving futile treatment at some point during their ICU hospitalization.3 Given that more than 1 in 5 decedents die after an ICU stay during a terminal admission, there is increasing scrutiny of the ICU as a setting where potentially inappropriate resource-intensive treatment is provided.4-6 Blood is an especially valuable resource, not only because it exists in finite supply (and is sometimes in shortage) but also because it is donated in ways that arguably create special stewardship expectations and responsibilities for those trusted to make decisions about its use. The amount of blood products used for patients who are perceived to be receiving inappropriate critical care has not been quantified.

Blood transfusion is the most frequently performed inpatient procedure, occurring in more than 10% of hospital admissions that involve a procedure.7 When used appropriately, the transfusion of blood products can be lifesaving; however, studies show that some transfused blood might not be needed and efforts are afoot to improve the match between transfusion and transfusion need.8,9 These efforts largely focus on generating guidelines based on physiologic benefit and aim mainly at promoting a restrictive transfusion protocol by avoiding blood product use for patients who will likely do well even without transfusion.8,10-12 The guiding principle behind efforts to improve the stewardship of scarce blood products is that they should only be used if they will make a difference in patient outcomes. Unlike prior studies, the goal of this study is to quantify the amount of blood products administered to patients who would do poorly with or without receipt of blood products, that is, patients perceived by their physicians as receiving futile critical care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Based on a focus group discussion with physicians who cared for critically ill patients, a questionnaire was developed to identify patients perceived as receiving futile critical care. Details of the definition of futile treatment and the core data collection are described in detail elsewhere.3

For each ICU patient under the physician’s care, the attending physician completed a daily questionnaire asking whether the patient was receiving futile treatment, probably futile treatment, or nonfutile treatment. These surveys were administered every day from December 15, 2011, through March 15, 2012, to each critical care specialist providing care in 5 ICUs (medical ICU, neurocritical care ICU, cardiac care unit, cardiothoracic ICU, and a mixed medical-surgical ICU) in 1 academic health system. All clinicians provided informed consent.

Patients were categorized into the following 3 groups: patients for whom treatment was never perceived as futile; patients with at least 1 assessment that treatment was probably futile, but no futile treatment assessments; and patients who had at least 1 assessment of futile treatment. Hospital and 6-month mortality was abstracted for all patients.

The Division of Transfusion Medicine provided a database of all adult patients during the 3-month study period who received a transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), apheresis platelets, plasma, or cryoprecipitate (5 unit prepooled units). This database was merged with the daily assessments of the appropriateness of critical care. To determine the proportion of blood products that was utilized for patients receiving inappropriate treatment, we tallied the blood products infused to these patients after the day the patient was assessed as receiving probably inappropriate or inappropriate treatment. The denominator was the total amount of blood products used by all assessed patients during the 3-month study period.

This study was approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

During the 3-month study period, 36 critical care clinicians in 5 ICUs provided care to 1193 adult patients. After excluding boarders in the ICUs and missed and invalid assessments, 6916 assessments were made on 1136 patients. Of these 1136 patients, 98 (8.6%) patients received probably futile treatment and 123 (11%) patients received futile treatment according to the physicians caring for them.

For patients who were never rated as receiving futile treatment, the in-hospital mortality was 4.6% and the 6-month mortality was 7.3%. On the contrary, 68% of the patients who were perceived to receive futile ICU treatment died before hospital discharge and 85% died within 6 months; survivors remained in severely compromised health states.3

DISCUSSION

Blood and blood products are donated resources. These biological products are altruistically given with the expectation that they will be used to benefit others.13 It is the clinicians’ responsibility to use these precious gifts to achieve the goals of medicine, which include curing, preserving function, and preventing clinical deterioration that has meaning to the patient. Our study shows that a small, but not insignificant, proportion of these donated resources are provided to hospitalized patients who are perceived as receiving futile critical care. That means that these transfusions are used as part of the critical care interventions that prolong the dying process and achieve outcomes, such as existence in coma, which few, if any, patients would desire. However, it should be noted that some of the health states preserved, such as neurological devastation or multi-organ failure with an inability to survive outside an ICU, were likely desired by patients’ families and might even have been desired by patients themselves. Whether blood donors would wish to donate blood to preserve life in such compromised health states is testable. This proportion of blood provided to ICU patients perceived as receiving futile treatment (7.6%) is similar to or greater than that lost due to wastage, which ranges from 0.1% to 6.7%.14 While the loss of this small proportion of blood products due to expiration or procedural issues is probably unavoidable, but should be minimized as much as possible, the provision of blood products to patients receiving futile critical care is under the control of the healthcare team. This raises the question of how altruistic blood donors would feel about donating if they were aware that 1 of every 13 units transfused in the ICU would be given to a patient that the physician feels will not benefit. In turn, it raises the question of whether the physician should refrain from using these blood products for patients who will not benefit in accordance with principles of evidence-based medicine, in order to ensure their availability for patients that will benefit.

This study has several limitations. Family/patient perspectives were not included in the assessment of futile treatment. It should also be recognized that the percentage of blood products provided to patients receiving inappropriate critical care is likely an underestimate as only blood product use during the 3-month study period was included, as many of these patients were admitted to the ICU prior the study period, and/or remained in the ICU or hospital after this window.

CONCLUSIONS

Similar to other treatments provided to patients who are perceived to receive futile critical care, blood products represent a healthcare resource that has the potential to be used without achieving the goals of medicine. But unlike many other medical treatments, the ability to maintain an adequate blood supply for transfusion relies on altruistic blood donors, individuals who are simply motivated by a desire to achieve a healthcare good.13 Explicit guidelines on the use of blood products should be developed to ensure that the use of this precious resource achieves meaningful goals. These goals need to be transparently defined such that a physician’s decision to not transfuse is expected as part of evidence-based medicine. Empiric research, educational interventions, and clearly delineated conflict-resolution processes may improve clinicians’ ability to handle these difficult cases.15

Disclosure

T. Neville was supported by the UCLA CTSI KL2 UL1TR000124, the NIH-NIA 1K23AG047900 - 01A1, and the NIH Loan Repayment Program grant. This project was supported by a donation from Mary Kay Farley to RAND Health. The funder played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Palda VA, Bowman KW, McLean RF, Chapman MG. “Futile” care: do we provide it? Why? A semistructured, Canada-wide survey of intensive care unit doctors and nurses. J Crit Care. 2005;20:207-213. PubMed

2. Piers RD, Azoulay E, Ricou B, et al. Perceptions of appropriateness of care among European and Israeli intensive care unit nurses and physicians. JAMA. 2011;306:2694-2703. PubMed

3. Huang S, Dang H, Huynh W, Sambrook PJ, Goss AN. The healing of dental extraction sockets in patients with Type 2 diabetes on oral hypoglycaemics: a prospective cohort. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:89-93. PubMed

4. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638-643. PubMed

5. Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Harrison DA, Barnato AE, Rowan KM, Angus DC. Use of intensive care services during terminal hospitalizations in England and the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:875-880. PubMed

6. Esserman L, Belkora J, Lenert L. Potentially ineffective care. A new outcome to assess the limits of critical care. JAMA. 1995;274:1544-1551. PubMed

7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: HCUP facts and figures: statistics on hospital-based care in the United States. 2009. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/factsandfigures/2009/TOC_2009.jsp. Accessed July 15, 2016.

8. Goodnough LT, Maggio P, Hadhazy E, et al. Restrictive blood transfusion practices are associated with improved patient outcomes. Transfusion. 2014;54:2753-2759. PubMed

9. Shander AS, Goodnough LT. Blood transfusion as a quality indicator in cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2010;304:1610-1611. PubMed

10. Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417. PubMed

11. Morton J, Anastassopoulos KP, Patel ST, et al. Frequency and outcomes of blood products transfusion across procedures and clinical conditions warranting inpatient care: an analysis of the 2004 healthcare cost and utilization project nationwide inpatient sample database. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:289-296. PubMed

12. Shander A, Fink A, Javidroozi M, et al. Appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: the international consensus conference on transfusion outcomes. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:232-246 e53. PubMed

13. Bednall TC, Bove LL. Donating blood: a meta-analytic review of self-reported motivators and deterrents. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:317-334. PubMed

14. Heitmiller ES, Hill RB, Marshall CE, et al. Blood wastage reduction using Lean Sigma methodology. Transfusion. 2010;50:1887-1896. PubMed

15. Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. An Official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM Policy Statement: Responding to Requests for Potentially Inappropriate Treatments in Intensive Care Units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1318-1330. PubMed

1. Palda VA, Bowman KW, McLean RF, Chapman MG. “Futile” care: do we provide it? Why? A semistructured, Canada-wide survey of intensive care unit doctors and nurses. J Crit Care. 2005;20:207-213. PubMed

2. Piers RD, Azoulay E, Ricou B, et al. Perceptions of appropriateness of care among European and Israeli intensive care unit nurses and physicians. JAMA. 2011;306:2694-2703. PubMed

3. Huang S, Dang H, Huynh W, Sambrook PJ, Goss AN. The healing of dental extraction sockets in patients with Type 2 diabetes on oral hypoglycaemics: a prospective cohort. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:89-93. PubMed

4. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638-643. PubMed

5. Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Harrison DA, Barnato AE, Rowan KM, Angus DC. Use of intensive care services during terminal hospitalizations in England and the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:875-880. PubMed

6. Esserman L, Belkora J, Lenert L. Potentially ineffective care. A new outcome to assess the limits of critical care. JAMA. 1995;274:1544-1551. PubMed

7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: HCUP facts and figures: statistics on hospital-based care in the United States. 2009. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/factsandfigures/2009/TOC_2009.jsp. Accessed July 15, 2016.

8. Goodnough LT, Maggio P, Hadhazy E, et al. Restrictive blood transfusion practices are associated with improved patient outcomes. Transfusion. 2014;54:2753-2759. PubMed

9. Shander AS, Goodnough LT. Blood transfusion as a quality indicator in cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2010;304:1610-1611. PubMed

10. Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417. PubMed

11. Morton J, Anastassopoulos KP, Patel ST, et al. Frequency and outcomes of blood products transfusion across procedures and clinical conditions warranting inpatient care: an analysis of the 2004 healthcare cost and utilization project nationwide inpatient sample database. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:289-296. PubMed

12. Shander A, Fink A, Javidroozi M, et al. Appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: the international consensus conference on transfusion outcomes. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:232-246 e53. PubMed

13. Bednall TC, Bove LL. Donating blood: a meta-analytic review of self-reported motivators and deterrents. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:317-334. PubMed

14. Heitmiller ES, Hill RB, Marshall CE, et al. Blood wastage reduction using Lean Sigma methodology. Transfusion. 2010;50:1887-1896. PubMed

15. Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. An Official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM Policy Statement: Responding to Requests for Potentially Inappropriate Treatments in Intensive Care Units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1318-1330. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Magnitude of Potentially Inappropriate Thrombophilia Testing in the Inpatient Hospital Setting

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) affects more than 1 million patients and costs the US healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.1 Inherited and acquired thrombophilias have been perceived as important risk factors in assessing the risk of VTE recurrence and guiding the duration of anticoagulation.

Thrombophilias increase the risk of a first thrombotic event, but existing data have failed to demonstrate the usefulness of routine thrombophilia screening on subsequent management.2,3 Moreover, thrombophilia testing ordered in the context of an inpatient hospitalization is limited by confounding factors, especially during an acute thrombotic event or in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.4

Recognizing the costliness of routine thrombophilia testing, The American Society of Hematology introduced its Choosing Wisely campaign in 2013 in an effort to reduce test ordering in the setting of provoked VTEs with a major transient risk factor.5 In order to define current practice behavior at our institution, we conducted a retrospective study to determine the magnitude and financial impact of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing in the inpatient setting.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of thrombophilia testing across all inpatient services at a large, quaternary-care academic institution over a 2-year period. Electronic medical record data containing all thrombophilia tests ordered on inpatients from June 2013 to June 2015 were obtained. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Inclusion criteria included any inpatient for which thrombophilia testing occurred. Patients were excluded if testing was ordered in the absence of VTE or arterial thrombosis or if it was ordered as part of a work-up for another medical condition (see Supplementary Material).

Thrombophilia testing was defined as any of the following: inherited thrombophilias (Factor V Leiden or prothrombin 20210 gene mutations, antithrombin, or protein C or S activity levels) or acquired thrombophilias (lupus anticoagulant [Testing refers to the activated partial thromboplastin time lupus assay.], beta-2 glycoprotein 1 immunoglobulins M and G, anticardiolipin immunoglobulins M and G, dilute Russell’s viper venom time, or JAK2 V617F mutations).

Extracted data included patient age, sex, type of thrombophilia test ordered, ordering primary service, admission diagnosis, and objective confirmation of thrombotic events. The indication for test ordering was determined via medical record review of the patient’s corresponding hospitalization. Each test was evaluated in the context of the patient’s presenting history, hospital course, active medications, accompanying laboratory and radiographic studies, and consultant recommendations to arrive at a conclusion regarding both the test’s reason for ordering and whether its indication was “inappropriate,” “appropriate,” or “equivocal.” Cost data were obtained through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule for 2016 (see Supplementary Material).6

The criteria for defining test appropriateness were formulated by utilizing a combination of major society guidelines and literature review.5,7-10 The criteria placed emphasis upon the ordered tests’ clinical relevance and reliability and were subsequently reviewed by a senior hematologist with specific expertise in thrombosis (see Supplementary Material).

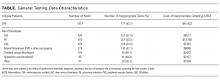

Two internal medicine resident physician data reviewers independently evaluated the ordered tests. To ensure consistency between reviewers, a sample of identical test orders was compared for concordance, and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated. For purposes of analysis, equivocal orders were included under the appropriate category, as this study focused on the quantification of potentially inappropriate ordering practices. Pearson chi-square testing was performed in order to compare ordering practices between services using Stata.11

RESULTS

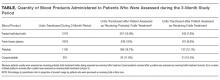

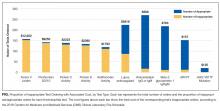

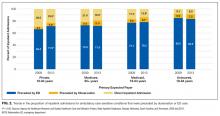

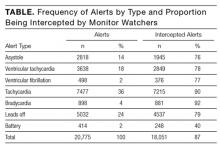

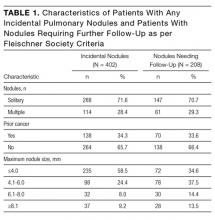

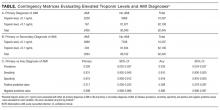

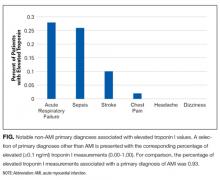

In total, we reviewed 2179 individual tests, of which 362 (16.6%) were excluded. The remaining 1817 tests involved 299 patients across 26 primary specialties. Fifty-two (2.9% of orders) were ultimately deemed equivocal. The Table illustrates the overall proportion and cost of inappropriate test ordering as well as testing characteristics of the most commonly encountered thrombotic diagnoses. The Figure illustrates the proportion of potentially inappropriate test ordering with its associated cost by test type.

Orders for Factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210, and protein C and S activity levels were most commonly deemed inappropriate due to the test results’ failure to alter clinical management (97.3%, 99.2%, 99.4% of their inappropriate orders, respectively). Antithrombin testing (59.4%) was deemed inappropriate most commonly in the setting of acute thrombosis. The lupus anticoagulant (82.8%) was inappropriately ordered most frequently in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.

Ordering practices were then compared between nonteaching and teaching inpatient general medicine services. We observed a higher proportion of inappropriate tests ordered by the nonteaching services as compared to the teaching services (120 of 173 orders [69.4%] versus 125 of 320 [39.1%], respectively; P < 0.001).

The interreviewer kappa coefficient was 0.82 (P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective analysis represents one of the largest examinations of inpatient thrombophilia testing practices to date. Our results illustrate the high prevalence and significant financial impact of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing conducted in the inpatient setting. The data confirm that, per our defined criteria, more than 90% of inherited thrombophilia testing was potentially inappropriate while the majority of acquired thrombophilia testing was appropriate, with the exception of the lupus anticoagulant.

Even when appropriately ordered, studies suggest that positive thrombophilia screening results fail to impact outcomes in most patients with VTE. In an effort to evaluate positive results’ potential to provide a basis from which to extend the duration of anticoagulation, and therefore reduce the risk of a recurrent VTE, a case-control analysis was performed on a series of patients with a first-VTE event (Multiple Environmental and Genetic Assessment of risk factors for venous thrombosis [MEGA] study).3 In examining the odds ratio (OR) for recurrence between patients who did or did not undergo testing for Factor V Leiden, antithrombin, or protein C or S activity, the data failed to show an impact of testing on the risk of VTE recurrence (OR 1.2; confidence interval, 0.8-1.8). In fact, decision making has increasingly relied on patients’ clinical characteristics rather than thrombophilia test results to guide anticoagulation duration after incident VTEs. A 2017 study illustrated that when using a clinical decision rule (Clinical Decision Rule Validation Study to Predict Low Recurrent Risk in Patients With Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism [REVERSE criteria]) in patients with a first, unprovoked VTE, routine thrombophilia screening added little to determining the need for prolonged anticoagulation.12 These findings support the limited clinical utility of current test ordering practices for the prediction and management of recurrent venous thrombosis.

Regarding the acquired thrombophilias, antiphospholipid antibody testing was predominantly ordered in a justified manner, which is consistent with the notion that test results could affect clinical management, such as anticoagulation duration or choice of anticoagulant.13 However, the validity of lupus anticoagulant testing was limited by the frequency of patients on concurrent anticoagulation.

Financially, the cumulative cost associated with inappropriate ordering was substantial, regardless of the thrombotic event in question. Moreover, our calculated costs are derived from CMS reimbursement rates and likely underestimate the true financial impact of errant testing given that commercial laboratories frequently charge at rates several-fold higher. On a national scale, prior analyses have suggested that the annual cost of thrombophilia testing, based on typical commercial rates, ranges from $300 million to $672 million.14

Researchers in prior studies have similarly examined the frequency of inappropriate thrombophilia testing and methods to reduce it. Researchers in a 2014 study demonstrated initially high rates of inappropriate inherited thrombophilia testing, and then showed marked reductions in testing and cost savings across multiple specialties following the introduction of a flowchart on a preprinted order form.15 Our findings provide motivation to perform similar endeavors.

The proportional difference of inappropriate ordering observed between nonteaching- and teaching-medicine services indicates a potential role for educational interventions. We recently completed a series of lectures on high-value thrombophilia ordering for residents and are actively analyzing its impact on subsequent ordering practices. We are also piloting an electronic best practice advisory for thrombophilia test ordering. Though the advisory may be overridden, providers are asked to provide justification for doing so on a voluntary basis. We plan to evaluate its effect on our findings reported in this study.

We acknowledge that our exclusion criteria resulted in the omission of testing across a spectrum of nonthrombotic clinical conditions, raising the question of selection bias. Because there are no established guidelines to determine the appropriateness of testing in these scenarios, we chose to limit the analysis of errant ordering to the context of thrombotic events. Other limitations of this study include the analysis of equivocal orders as appropriate. However, because equivocal ordering represented less than 3% of all analyzed orders, including these as inappropriate would not have significantly altered our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

A review of thrombophilia testing practices at our institution demonstrated that inappropriate testing in the inpatient setting is a frequent phenomenon associated with a significant financial impact. This effect was more pronounced in inherited versus acquired thrombophilia testing. Testing was frequently confounded and often failed to impact patients’ short- or long-term clinical management, regardless of the result.

These findings serve as a strong impetus to reduce the burden of routine thrombophilia testing during hospital admissions. Our data demonstrate a need for institution-wide changes such as implementing best practice advisories, introducing ordering restrictions, and conducting educational interventions in order to reduce unnecessary expenditures and improve patient care.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953. PubMed

2. Cohn DM, Vansenne F, de Borgie CA, Middeldorp S. Thrombophilia testing for prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:Cd007069. PubMed

3. Coppens M, Reijnders JH, Middeldorp S, Doggen CJ, Rosendaal FR. Testing for inherited thrombophilia does not reduce the recurrence of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1474-1477. PubMed

4. Somma J, Sussman, II, Rand JH. An evaluation of thrombophilia screening in an urban tertiary care medical center: A “real world” experience. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(1):120-127. PubMed

5. Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely® campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Blood. 2013;122(24):3879-3883. PubMed

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html. Accessed October 2016

7. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):154-164. PubMed

8. Moll S. Thrombophilia: clinical-practical aspects. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39(3):367-378. PubMed

9. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for vte disease: Chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. PubMed

10. Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220. PubMed

11. Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

12. Garcia-Horton A, Kovacs MJ, Abdulrehman J, Taylor JE, Sharma S, Lazo-Langner A. Impact of thrombophilia screening on venous thromboembolism management practices. Thromb Res.149:76-80. PubMed

13. Schulman S, Svenungsson E, Granqvist S. Anticardiolipin antibodies predict early recurrence of thromboembolism and death among patients with venous thromboembolism following anticoagulant therapy. Duration of Anticoagulation Study Group. Am J Med. 1998;104(4):332-338. PubMed

14. Petrilli CM, Heidemann L, Mack M, Durance P, Chopra V. Inpatient inherited thrombophilia testing. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):801-804. PubMed

15. Smith TW, Pi D, Hudoba M, Lee AY. Reducing inpatient heritable thrombophilia testing using a clinical decision-making tool. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(4):345-349. PubMed

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) affects more than 1 million patients and costs the US healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.1 Inherited and acquired thrombophilias have been perceived as important risk factors in assessing the risk of VTE recurrence and guiding the duration of anticoagulation.

Thrombophilias increase the risk of a first thrombotic event, but existing data have failed to demonstrate the usefulness of routine thrombophilia screening on subsequent management.2,3 Moreover, thrombophilia testing ordered in the context of an inpatient hospitalization is limited by confounding factors, especially during an acute thrombotic event or in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.4

Recognizing the costliness of routine thrombophilia testing, The American Society of Hematology introduced its Choosing Wisely campaign in 2013 in an effort to reduce test ordering in the setting of provoked VTEs with a major transient risk factor.5 In order to define current practice behavior at our institution, we conducted a retrospective study to determine the magnitude and financial impact of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing in the inpatient setting.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of thrombophilia testing across all inpatient services at a large, quaternary-care academic institution over a 2-year period. Electronic medical record data containing all thrombophilia tests ordered on inpatients from June 2013 to June 2015 were obtained. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Inclusion criteria included any inpatient for which thrombophilia testing occurred. Patients were excluded if testing was ordered in the absence of VTE or arterial thrombosis or if it was ordered as part of a work-up for another medical condition (see Supplementary Material).

Thrombophilia testing was defined as any of the following: inherited thrombophilias (Factor V Leiden or prothrombin 20210 gene mutations, antithrombin, or protein C or S activity levels) or acquired thrombophilias (lupus anticoagulant [Testing refers to the activated partial thromboplastin time lupus assay.], beta-2 glycoprotein 1 immunoglobulins M and G, anticardiolipin immunoglobulins M and G, dilute Russell’s viper venom time, or JAK2 V617F mutations).

Extracted data included patient age, sex, type of thrombophilia test ordered, ordering primary service, admission diagnosis, and objective confirmation of thrombotic events. The indication for test ordering was determined via medical record review of the patient’s corresponding hospitalization. Each test was evaluated in the context of the patient’s presenting history, hospital course, active medications, accompanying laboratory and radiographic studies, and consultant recommendations to arrive at a conclusion regarding both the test’s reason for ordering and whether its indication was “inappropriate,” “appropriate,” or “equivocal.” Cost data were obtained through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule for 2016 (see Supplementary Material).6

The criteria for defining test appropriateness were formulated by utilizing a combination of major society guidelines and literature review.5,7-10 The criteria placed emphasis upon the ordered tests’ clinical relevance and reliability and were subsequently reviewed by a senior hematologist with specific expertise in thrombosis (see Supplementary Material).

Two internal medicine resident physician data reviewers independently evaluated the ordered tests. To ensure consistency between reviewers, a sample of identical test orders was compared for concordance, and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated. For purposes of analysis, equivocal orders were included under the appropriate category, as this study focused on the quantification of potentially inappropriate ordering practices. Pearson chi-square testing was performed in order to compare ordering practices between services using Stata.11

RESULTS

In total, we reviewed 2179 individual tests, of which 362 (16.6%) were excluded. The remaining 1817 tests involved 299 patients across 26 primary specialties. Fifty-two (2.9% of orders) were ultimately deemed equivocal. The Table illustrates the overall proportion and cost of inappropriate test ordering as well as testing characteristics of the most commonly encountered thrombotic diagnoses. The Figure illustrates the proportion of potentially inappropriate test ordering with its associated cost by test type.

Orders for Factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210, and protein C and S activity levels were most commonly deemed inappropriate due to the test results’ failure to alter clinical management (97.3%, 99.2%, 99.4% of their inappropriate orders, respectively). Antithrombin testing (59.4%) was deemed inappropriate most commonly in the setting of acute thrombosis. The lupus anticoagulant (82.8%) was inappropriately ordered most frequently in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.

Ordering practices were then compared between nonteaching and teaching inpatient general medicine services. We observed a higher proportion of inappropriate tests ordered by the nonteaching services as compared to the teaching services (120 of 173 orders [69.4%] versus 125 of 320 [39.1%], respectively; P < 0.001).

The interreviewer kappa coefficient was 0.82 (P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective analysis represents one of the largest examinations of inpatient thrombophilia testing practices to date. Our results illustrate the high prevalence and significant financial impact of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing conducted in the inpatient setting. The data confirm that, per our defined criteria, more than 90% of inherited thrombophilia testing was potentially inappropriate while the majority of acquired thrombophilia testing was appropriate, with the exception of the lupus anticoagulant.

Even when appropriately ordered, studies suggest that positive thrombophilia screening results fail to impact outcomes in most patients with VTE. In an effort to evaluate positive results’ potential to provide a basis from which to extend the duration of anticoagulation, and therefore reduce the risk of a recurrent VTE, a case-control analysis was performed on a series of patients with a first-VTE event (Multiple Environmental and Genetic Assessment of risk factors for venous thrombosis [MEGA] study).3 In examining the odds ratio (OR) for recurrence between patients who did or did not undergo testing for Factor V Leiden, antithrombin, or protein C or S activity, the data failed to show an impact of testing on the risk of VTE recurrence (OR 1.2; confidence interval, 0.8-1.8). In fact, decision making has increasingly relied on patients’ clinical characteristics rather than thrombophilia test results to guide anticoagulation duration after incident VTEs. A 2017 study illustrated that when using a clinical decision rule (Clinical Decision Rule Validation Study to Predict Low Recurrent Risk in Patients With Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism [REVERSE criteria]) in patients with a first, unprovoked VTE, routine thrombophilia screening added little to determining the need for prolonged anticoagulation.12 These findings support the limited clinical utility of current test ordering practices for the prediction and management of recurrent venous thrombosis.

Regarding the acquired thrombophilias, antiphospholipid antibody testing was predominantly ordered in a justified manner, which is consistent with the notion that test results could affect clinical management, such as anticoagulation duration or choice of anticoagulant.13 However, the validity of lupus anticoagulant testing was limited by the frequency of patients on concurrent anticoagulation.

Financially, the cumulative cost associated with inappropriate ordering was substantial, regardless of the thrombotic event in question. Moreover, our calculated costs are derived from CMS reimbursement rates and likely underestimate the true financial impact of errant testing given that commercial laboratories frequently charge at rates several-fold higher. On a national scale, prior analyses have suggested that the annual cost of thrombophilia testing, based on typical commercial rates, ranges from $300 million to $672 million.14

Researchers in prior studies have similarly examined the frequency of inappropriate thrombophilia testing and methods to reduce it. Researchers in a 2014 study demonstrated initially high rates of inappropriate inherited thrombophilia testing, and then showed marked reductions in testing and cost savings across multiple specialties following the introduction of a flowchart on a preprinted order form.15 Our findings provide motivation to perform similar endeavors.

The proportional difference of inappropriate ordering observed between nonteaching- and teaching-medicine services indicates a potential role for educational interventions. We recently completed a series of lectures on high-value thrombophilia ordering for residents and are actively analyzing its impact on subsequent ordering practices. We are also piloting an electronic best practice advisory for thrombophilia test ordering. Though the advisory may be overridden, providers are asked to provide justification for doing so on a voluntary basis. We plan to evaluate its effect on our findings reported in this study.

We acknowledge that our exclusion criteria resulted in the omission of testing across a spectrum of nonthrombotic clinical conditions, raising the question of selection bias. Because there are no established guidelines to determine the appropriateness of testing in these scenarios, we chose to limit the analysis of errant ordering to the context of thrombotic events. Other limitations of this study include the analysis of equivocal orders as appropriate. However, because equivocal ordering represented less than 3% of all analyzed orders, including these as inappropriate would not have significantly altered our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

A review of thrombophilia testing practices at our institution demonstrated that inappropriate testing in the inpatient setting is a frequent phenomenon associated with a significant financial impact. This effect was more pronounced in inherited versus acquired thrombophilia testing. Testing was frequently confounded and often failed to impact patients’ short- or long-term clinical management, regardless of the result.

These findings serve as a strong impetus to reduce the burden of routine thrombophilia testing during hospital admissions. Our data demonstrate a need for institution-wide changes such as implementing best practice advisories, introducing ordering restrictions, and conducting educational interventions in order to reduce unnecessary expenditures and improve patient care.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) affects more than 1 million patients and costs the US healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.1 Inherited and acquired thrombophilias have been perceived as important risk factors in assessing the risk of VTE recurrence and guiding the duration of anticoagulation.

Thrombophilias increase the risk of a first thrombotic event, but existing data have failed to demonstrate the usefulness of routine thrombophilia screening on subsequent management.2,3 Moreover, thrombophilia testing ordered in the context of an inpatient hospitalization is limited by confounding factors, especially during an acute thrombotic event or in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.4

Recognizing the costliness of routine thrombophilia testing, The American Society of Hematology introduced its Choosing Wisely campaign in 2013 in an effort to reduce test ordering in the setting of provoked VTEs with a major transient risk factor.5 In order to define current practice behavior at our institution, we conducted a retrospective study to determine the magnitude and financial impact of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing in the inpatient setting.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of thrombophilia testing across all inpatient services at a large, quaternary-care academic institution over a 2-year period. Electronic medical record data containing all thrombophilia tests ordered on inpatients from June 2013 to June 2015 were obtained. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Inclusion criteria included any inpatient for which thrombophilia testing occurred. Patients were excluded if testing was ordered in the absence of VTE or arterial thrombosis or if it was ordered as part of a work-up for another medical condition (see Supplementary Material).

Thrombophilia testing was defined as any of the following: inherited thrombophilias (Factor V Leiden or prothrombin 20210 gene mutations, antithrombin, or protein C or S activity levels) or acquired thrombophilias (lupus anticoagulant [Testing refers to the activated partial thromboplastin time lupus assay.], beta-2 glycoprotein 1 immunoglobulins M and G, anticardiolipin immunoglobulins M and G, dilute Russell’s viper venom time, or JAK2 V617F mutations).

Extracted data included patient age, sex, type of thrombophilia test ordered, ordering primary service, admission diagnosis, and objective confirmation of thrombotic events. The indication for test ordering was determined via medical record review of the patient’s corresponding hospitalization. Each test was evaluated in the context of the patient’s presenting history, hospital course, active medications, accompanying laboratory and radiographic studies, and consultant recommendations to arrive at a conclusion regarding both the test’s reason for ordering and whether its indication was “inappropriate,” “appropriate,” or “equivocal.” Cost data were obtained through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule for 2016 (see Supplementary Material).6

The criteria for defining test appropriateness were formulated by utilizing a combination of major society guidelines and literature review.5,7-10 The criteria placed emphasis upon the ordered tests’ clinical relevance and reliability and were subsequently reviewed by a senior hematologist with specific expertise in thrombosis (see Supplementary Material).

Two internal medicine resident physician data reviewers independently evaluated the ordered tests. To ensure consistency between reviewers, a sample of identical test orders was compared for concordance, and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated. For purposes of analysis, equivocal orders were included under the appropriate category, as this study focused on the quantification of potentially inappropriate ordering practices. Pearson chi-square testing was performed in order to compare ordering practices between services using Stata.11

RESULTS

In total, we reviewed 2179 individual tests, of which 362 (16.6%) were excluded. The remaining 1817 tests involved 299 patients across 26 primary specialties. Fifty-two (2.9% of orders) were ultimately deemed equivocal. The Table illustrates the overall proportion and cost of inappropriate test ordering as well as testing characteristics of the most commonly encountered thrombotic diagnoses. The Figure illustrates the proportion of potentially inappropriate test ordering with its associated cost by test type.

Orders for Factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210, and protein C and S activity levels were most commonly deemed inappropriate due to the test results’ failure to alter clinical management (97.3%, 99.2%, 99.4% of their inappropriate orders, respectively). Antithrombin testing (59.4%) was deemed inappropriate most commonly in the setting of acute thrombosis. The lupus anticoagulant (82.8%) was inappropriately ordered most frequently in the setting of concurrent anticoagulation.

Ordering practices were then compared between nonteaching and teaching inpatient general medicine services. We observed a higher proportion of inappropriate tests ordered by the nonteaching services as compared to the teaching services (120 of 173 orders [69.4%] versus 125 of 320 [39.1%], respectively; P < 0.001).

The interreviewer kappa coefficient was 0.82 (P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective analysis represents one of the largest examinations of inpatient thrombophilia testing practices to date. Our results illustrate the high prevalence and significant financial impact of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing conducted in the inpatient setting. The data confirm that, per our defined criteria, more than 90% of inherited thrombophilia testing was potentially inappropriate while the majority of acquired thrombophilia testing was appropriate, with the exception of the lupus anticoagulant.

Even when appropriately ordered, studies suggest that positive thrombophilia screening results fail to impact outcomes in most patients with VTE. In an effort to evaluate positive results’ potential to provide a basis from which to extend the duration of anticoagulation, and therefore reduce the risk of a recurrent VTE, a case-control analysis was performed on a series of patients with a first-VTE event (Multiple Environmental and Genetic Assessment of risk factors for venous thrombosis [MEGA] study).3 In examining the odds ratio (OR) for recurrence between patients who did or did not undergo testing for Factor V Leiden, antithrombin, or protein C or S activity, the data failed to show an impact of testing on the risk of VTE recurrence (OR 1.2; confidence interval, 0.8-1.8). In fact, decision making has increasingly relied on patients’ clinical characteristics rather than thrombophilia test results to guide anticoagulation duration after incident VTEs. A 2017 study illustrated that when using a clinical decision rule (Clinical Decision Rule Validation Study to Predict Low Recurrent Risk in Patients With Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism [REVERSE criteria]) in patients with a first, unprovoked VTE, routine thrombophilia screening added little to determining the need for prolonged anticoagulation.12 These findings support the limited clinical utility of current test ordering practices for the prediction and management of recurrent venous thrombosis.

Regarding the acquired thrombophilias, antiphospholipid antibody testing was predominantly ordered in a justified manner, which is consistent with the notion that test results could affect clinical management, such as anticoagulation duration or choice of anticoagulant.13 However, the validity of lupus anticoagulant testing was limited by the frequency of patients on concurrent anticoagulation.

Financially, the cumulative cost associated with inappropriate ordering was substantial, regardless of the thrombotic event in question. Moreover, our calculated costs are derived from CMS reimbursement rates and likely underestimate the true financial impact of errant testing given that commercial laboratories frequently charge at rates several-fold higher. On a national scale, prior analyses have suggested that the annual cost of thrombophilia testing, based on typical commercial rates, ranges from $300 million to $672 million.14

Researchers in prior studies have similarly examined the frequency of inappropriate thrombophilia testing and methods to reduce it. Researchers in a 2014 study demonstrated initially high rates of inappropriate inherited thrombophilia testing, and then showed marked reductions in testing and cost savings across multiple specialties following the introduction of a flowchart on a preprinted order form.15 Our findings provide motivation to perform similar endeavors.

The proportional difference of inappropriate ordering observed between nonteaching- and teaching-medicine services indicates a potential role for educational interventions. We recently completed a series of lectures on high-value thrombophilia ordering for residents and are actively analyzing its impact on subsequent ordering practices. We are also piloting an electronic best practice advisory for thrombophilia test ordering. Though the advisory may be overridden, providers are asked to provide justification for doing so on a voluntary basis. We plan to evaluate its effect on our findings reported in this study.

We acknowledge that our exclusion criteria resulted in the omission of testing across a spectrum of nonthrombotic clinical conditions, raising the question of selection bias. Because there are no established guidelines to determine the appropriateness of testing in these scenarios, we chose to limit the analysis of errant ordering to the context of thrombotic events. Other limitations of this study include the analysis of equivocal orders as appropriate. However, because equivocal ordering represented less than 3% of all analyzed orders, including these as inappropriate would not have significantly altered our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

A review of thrombophilia testing practices at our institution demonstrated that inappropriate testing in the inpatient setting is a frequent phenomenon associated with a significant financial impact. This effect was more pronounced in inherited versus acquired thrombophilia testing. Testing was frequently confounded and often failed to impact patients’ short- or long-term clinical management, regardless of the result.

These findings serve as a strong impetus to reduce the burden of routine thrombophilia testing during hospital admissions. Our data demonstrate a need for institution-wide changes such as implementing best practice advisories, introducing ordering restrictions, and conducting educational interventions in order to reduce unnecessary expenditures and improve patient care.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953. PubMed

2. Cohn DM, Vansenne F, de Borgie CA, Middeldorp S. Thrombophilia testing for prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:Cd007069. PubMed

3. Coppens M, Reijnders JH, Middeldorp S, Doggen CJ, Rosendaal FR. Testing for inherited thrombophilia does not reduce the recurrence of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1474-1477. PubMed

4. Somma J, Sussman, II, Rand JH. An evaluation of thrombophilia screening in an urban tertiary care medical center: A “real world” experience. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(1):120-127. PubMed

5. Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely® campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Blood. 2013;122(24):3879-3883. PubMed

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html. Accessed October 2016

7. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):154-164. PubMed

8. Moll S. Thrombophilia: clinical-practical aspects. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39(3):367-378. PubMed

9. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for vte disease: Chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. PubMed

10. Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220. PubMed

11. Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

12. Garcia-Horton A, Kovacs MJ, Abdulrehman J, Taylor JE, Sharma S, Lazo-Langner A. Impact of thrombophilia screening on venous thromboembolism management practices. Thromb Res.149:76-80. PubMed

13. Schulman S, Svenungsson E, Granqvist S. Anticardiolipin antibodies predict early recurrence of thromboembolism and death among patients with venous thromboembolism following anticoagulant therapy. Duration of Anticoagulation Study Group. Am J Med. 1998;104(4):332-338. PubMed

14. Petrilli CM, Heidemann L, Mack M, Durance P, Chopra V. Inpatient inherited thrombophilia testing. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):801-804. PubMed

15. Smith TW, Pi D, Hudoba M, Lee AY. Reducing inpatient heritable thrombophilia testing using a clinical decision-making tool. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(4):345-349. PubMed

1. Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953. PubMed

2. Cohn DM, Vansenne F, de Borgie CA, Middeldorp S. Thrombophilia testing for prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:Cd007069. PubMed

3. Coppens M, Reijnders JH, Middeldorp S, Doggen CJ, Rosendaal FR. Testing for inherited thrombophilia does not reduce the recurrence of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1474-1477. PubMed

4. Somma J, Sussman, II, Rand JH. An evaluation of thrombophilia screening in an urban tertiary care medical center: A “real world” experience. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(1):120-127. PubMed

5. Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely® campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Blood. 2013;122(24):3879-3883. PubMed

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html. Accessed October 2016

7. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):154-164. PubMed

8. Moll S. Thrombophilia: clinical-practical aspects. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39(3):367-378. PubMed

9. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for vte disease: Chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. PubMed

10. Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220. PubMed

11. Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

12. Garcia-Horton A, Kovacs MJ, Abdulrehman J, Taylor JE, Sharma S, Lazo-Langner A. Impact of thrombophilia screening on venous thromboembolism management practices. Thromb Res.149:76-80. PubMed

13. Schulman S, Svenungsson E, Granqvist S. Anticardiolipin antibodies predict early recurrence of thromboembolism and death among patients with venous thromboembolism following anticoagulant therapy. Duration of Anticoagulation Study Group. Am J Med. 1998;104(4):332-338. PubMed

14. Petrilli CM, Heidemann L, Mack M, Durance P, Chopra V. Inpatient inherited thrombophilia testing. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):801-804. PubMed

15. Smith TW, Pi D, Hudoba M, Lee AY. Reducing inpatient heritable thrombophilia testing using a clinical decision-making tool. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(4):345-349. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

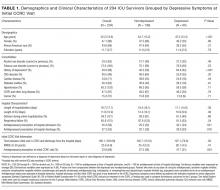

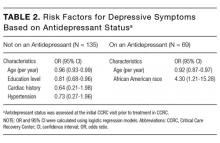

Antidepressant Use and Depressive Symptoms in Intensive Care Unit Survivors

As the number of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors has steadily increased over the past few decades, there is growing awareness of the long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments after ICU hospitalization, collectively known as post–intensive care syndrome (PICS).1 Systematic reviews based mostly on research studies suggest that the prevalence of depressive symptoms 2-12 months after ICU discharge is nearly 30%.2-5 Due to the scarcity of established models of care for ICU survivors, there is limited characterization of depressive symptoms and antidepressant regimens in this clinical population. The Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) at Eskenazi Hospital is one of the first ICU survivor clinics in the United States and targets a racially diverse, underserved population in the Indianapolis metropolitan area.6 In this study, we examined whether patients had depressive symptoms at their initial CCRC visit, and whether the risk factors for depressive symptoms differed if they were on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit.

METHODS

Referral criteria to the CCRC were 18 years or older, admitted to the Eskenazi ICU, were on mechanical ventilation or delirious for ≥48 hours (major risk factors for the development of PICS), and recommended for follow-up by a critical care physician. The exclusion criterion included was enrollment in hospice or palliative care services. Institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct retrospective analyses of de-identified clinical data. Medical history and medication lists were collected from patients, informal caregivers, and electronic medical records.