User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

COVID-19: When health care personnel become patients

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That number, however, is probably an underestimation because health care personnel (HCP) status was available for just over 49,000 of the 315,000 COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of April 9. Of the cases with known HCP status, 9,282 (19%) were health care personnel, Matthew J. Stuckey, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team said.

“The number of cases in HCP reported here must be considered a lower bound because additional cases likely have gone unidentified or unreported,” they said.

The median age of the nearly 9,300 HCP with COVID-19 was 42 years, and the majority (55%) were aged 16-44 years; another 21% were 45-54, 18% were 55-64, and 6% were age 65 and over. The oldest group, however, represented 10 of the 27 known HCP deaths, the investigators reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

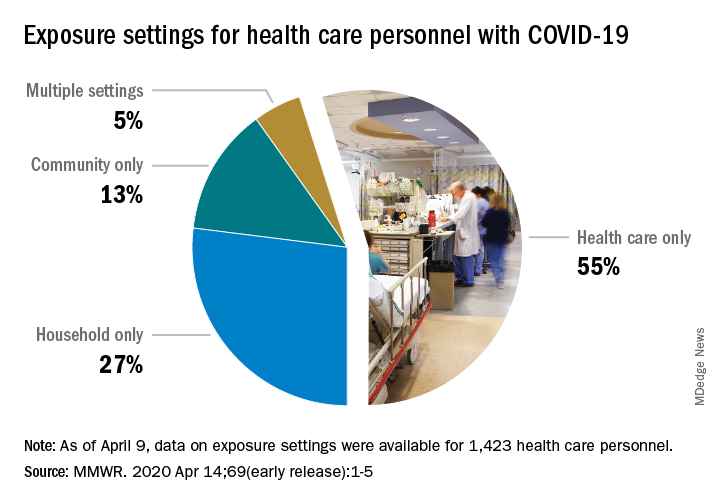

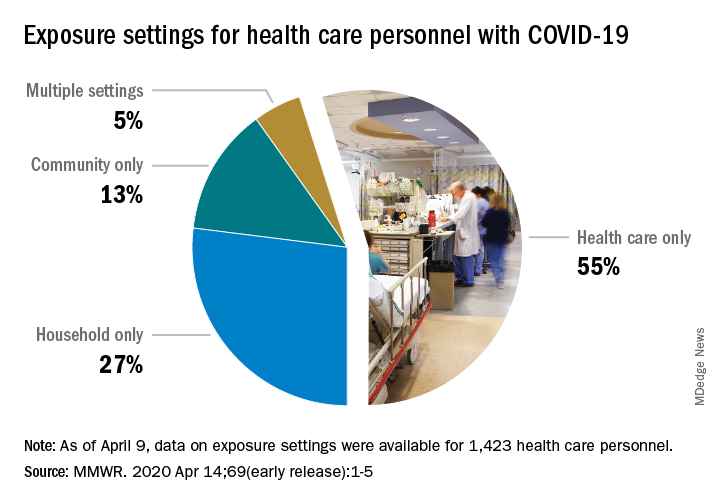

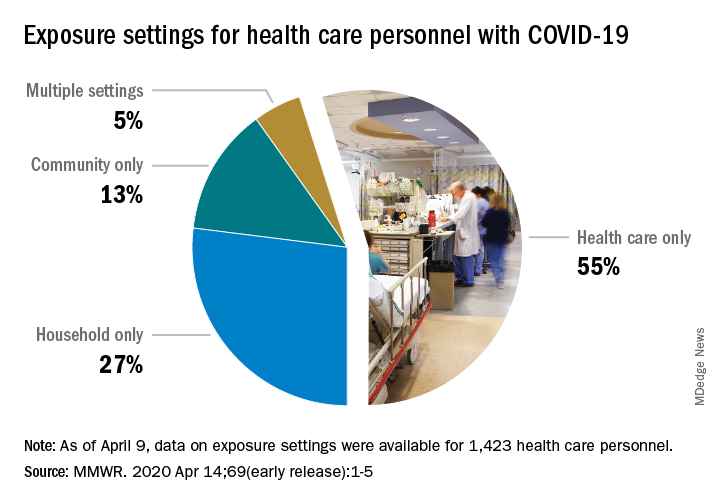

The majority of infected HCP (55%) reported exposure to a COVID-19 patient in the health care setting, but “there were also known exposures in households and in the community, highlighting the potential for exposure in multiple settings, especially as community transmission increases,” the response team said.

Since “contact tracing after recognized occupational exposures likely will fail to identify many HCP at risk for developing COVID-19,” other measures will probably be needed to “reduce the risk for infected HCP transmitting the virus to colleagues and patients,” they added.

HCP with COVID-19 were less likely to be hospitalized (8%-10%) than the overall population (21%-31%), which “might reflect the younger median age … of HCP patients, compared with that of reported COVID-19 patients overall, as well as prioritization of HCP for testing, which might identify less-severe illness,” the investigators suggested.

The prevalence of underlying conditions in HCP patients, 38%, was the same as all patients with COVID-19, and 92% of the HCP patients presented with fever, cough, or shortness of breath. Two-thirds of all HCP reported muscle aches, and 65% reported headache, the CDC response team noted.

“It is critical to make every effort to ensure the health and safety of this essential national workforce of approximately 18 million HCP, both at work and in the community,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Stuckey MJ et al. MMWR. Apr 14;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That number, however, is probably an underestimation because health care personnel (HCP) status was available for just over 49,000 of the 315,000 COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of April 9. Of the cases with known HCP status, 9,282 (19%) were health care personnel, Matthew J. Stuckey, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team said.

“The number of cases in HCP reported here must be considered a lower bound because additional cases likely have gone unidentified or unreported,” they said.

The median age of the nearly 9,300 HCP with COVID-19 was 42 years, and the majority (55%) were aged 16-44 years; another 21% were 45-54, 18% were 55-64, and 6% were age 65 and over. The oldest group, however, represented 10 of the 27 known HCP deaths, the investigators reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The majority of infected HCP (55%) reported exposure to a COVID-19 patient in the health care setting, but “there were also known exposures in households and in the community, highlighting the potential for exposure in multiple settings, especially as community transmission increases,” the response team said.

Since “contact tracing after recognized occupational exposures likely will fail to identify many HCP at risk for developing COVID-19,” other measures will probably be needed to “reduce the risk for infected HCP transmitting the virus to colleagues and patients,” they added.

HCP with COVID-19 were less likely to be hospitalized (8%-10%) than the overall population (21%-31%), which “might reflect the younger median age … of HCP patients, compared with that of reported COVID-19 patients overall, as well as prioritization of HCP for testing, which might identify less-severe illness,” the investigators suggested.

The prevalence of underlying conditions in HCP patients, 38%, was the same as all patients with COVID-19, and 92% of the HCP patients presented with fever, cough, or shortness of breath. Two-thirds of all HCP reported muscle aches, and 65% reported headache, the CDC response team noted.

“It is critical to make every effort to ensure the health and safety of this essential national workforce of approximately 18 million HCP, both at work and in the community,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Stuckey MJ et al. MMWR. Apr 14;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That number, however, is probably an underestimation because health care personnel (HCP) status was available for just over 49,000 of the 315,000 COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of April 9. Of the cases with known HCP status, 9,282 (19%) were health care personnel, Matthew J. Stuckey, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team said.

“The number of cases in HCP reported here must be considered a lower bound because additional cases likely have gone unidentified or unreported,” they said.

The median age of the nearly 9,300 HCP with COVID-19 was 42 years, and the majority (55%) were aged 16-44 years; another 21% were 45-54, 18% were 55-64, and 6% were age 65 and over. The oldest group, however, represented 10 of the 27 known HCP deaths, the investigators reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The majority of infected HCP (55%) reported exposure to a COVID-19 patient in the health care setting, but “there were also known exposures in households and in the community, highlighting the potential for exposure in multiple settings, especially as community transmission increases,” the response team said.

Since “contact tracing after recognized occupational exposures likely will fail to identify many HCP at risk for developing COVID-19,” other measures will probably be needed to “reduce the risk for infected HCP transmitting the virus to colleagues and patients,” they added.

HCP with COVID-19 were less likely to be hospitalized (8%-10%) than the overall population (21%-31%), which “might reflect the younger median age … of HCP patients, compared with that of reported COVID-19 patients overall, as well as prioritization of HCP for testing, which might identify less-severe illness,” the investigators suggested.

The prevalence of underlying conditions in HCP patients, 38%, was the same as all patients with COVID-19, and 92% of the HCP patients presented with fever, cough, or shortness of breath. Two-thirds of all HCP reported muscle aches, and 65% reported headache, the CDC response team noted.

“It is critical to make every effort to ensure the health and safety of this essential national workforce of approximately 18 million HCP, both at work and in the community,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Stuckey MJ et al. MMWR. Apr 14;69(early release):1-5.

FROM THE MMWR

The role of FOAM and social networks in COVID-19

“Uncertainty creates weakness. Uncertainty makes one tentative, if not fearful, and tentative steps, even when in the right direction, may not overcome significant obstacles.”1

Recently, I spent my vacation time quarantined reading “The Great Influenza,” which recounts the history of the 1918 pandemic. Despite over a century of scientific and medical progress, the parallels to our current situation are indisputable. Just as in 1918, we are limiting social gatherings, quarantining, wearing face masks, and living with the fear and anxiety of keeping ourselves and our families safe. In 1918, use of aspirin, quinine, and digitalis therapies in a desperate search for relief despite limited evidence mirror the current use of hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and lopinavir/ritonavir. While there are many similarities between the two situations, in this pandemic our channels for dissemination of scientific literature are better developed, and online networks are enabling physicians across the globe to communicate their experience and findings in near real time.

During this time of uncertainty, our understanding of COVID-19 evolves daily. Without the advantage of robust randomized, controlled trials and large-scale studies to guide us, we are forced to rely on pattern recognition for surveillance and anecdotal or limited case-based accounts to guide clinical care. Fortunately, free open-access medical education (FOAM) and social networks offer a significant advantage in our ability to collect and disseminate information.

Free open access medical education

The concept of FOAM started in 2012 with the intent of creating a collaborative and constantly evolving community to provide open-access medical education. It encompasses multiple platforms – blogs, podcasts, videos, and social media – and features content experts from across the globe. Since its inception, FOAM has grown in popularity and use, especially within emergency medicine and critical care communities, as an adjunct for asynchronous learning.2,3

In a time where knowledge of COVID-19 is dynamically changing, traditional sources like textbooks, journals, and organizational guidelines often lag behind real-time clinical experience and needs. Additionally, many clinicians are now being tasked with taking care of patient populations and a new critical illness profile with which they are not comfortable. It is challenging to find a well-curated and updated repository of information to answer questions surrounding pathophysiology, critical care, ventilator management, caring for adult patients, and personal protective equipment (PPE). During this rapidly evolving reality, FOAM is becoming the ideal modality for timely and efficient sharing of reviews of current literature, expert discussions, and clinical practice guidelines.

A few self-directed hours on EMCrit’s Internet Book of Critical Care’s COVID-19 chapter reveals a bastion of content regarding diagnosis, pathophysiology, transmission, therapies, and ventilator strategies.4 It includes references to major journals and recommendations from international societies. Websites like EMCrit and REBEL EM are updated daily with podcasts, videos, and blog posts surrounding the latest highly debated topics in COVID-19 management.5 Podcasts like EM:RAP and Peds RAP have made COVID segments discussing important topics like pharmacotherapy, telemedicine, and pregnancy available for free.6,7 Many networks, institutions, and individual physicians have created and posted videos online on critical care topics and refreshers.

Social networks

Online social networks composed of international physicians within Facebook and LinkedIn serve as miniature publishing houses. First-hand accounts of patient presentations and patient care act as case reports. As similar accounts accumulate, they become case series. Patterns emerge and new hypotheses are generated, debated, and critiqued through this informal peer review. Personal accounts of frustration with lack of PPE, fear of exposing loved ones, distress at being separated from family, and grief of witnessing multiple patients die alone are opinion and perspective articles.

These networks offer the space for sharing. Those who have had the experience of caring for the surge of COVID-19 patients offer advice and words of caution to those who have yet to experience it. Protocols from a multitude of institutions on triage, surge, disposition, and end-of-life care are disseminated, serving as templates for those that have not yet developed their own. There is an impressive variety of innovative, do-it-yourself projects surrounding PPE, intubation boxes, and three-dimensionally printed ventilator parts.

Finally, these networks provide emotional support. There are offers to ship additional PPE, videos of cities cheering as clinicians go to work, stories of triumph and recovery, pictures depicting ongoing wellness activities, and the occasional much-needed humorous anecdote or illustration. These networks reinforce the message that our lives continue despite this upheaval, and we are not alone in this struggle.

The end of the passage in The Great Influenza concludes with: “Ultimately a scientist has nothing to believe in but the process of inquiry. To move forcefully and aggressively even while uncertain requires a confidence and strength deeper than physical courage.”

They represent a highly adaptable, evolving, and collaborative global community’s determination to persevere through time of uncertainty together.

Dr. Ren is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. Dr. Simpson is a pediatric emergency medicine attending and medical director of emergency preparedness at the hospital. They reported that they do not have any disclosures or conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Ren and Dr. Simpson at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.” (New York: Penguin Books, 2005, pp. 261-62).

2. Emerg Med J. 2014 Oct;31(e1):e76-7.

3. Acad Med. 2014 Apr;89(4):598-601.

4. “The Internet Book of Critical Care: COVID-19.” EMCrit Project.

5. “Covid-19.” REBEL EM-Emergency Medicine Blog.

6. “EM:RAP COVID-19 Resources.” EM RAP: Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives.

7. “Episodes.” Peds RAP, Hippo Education.

“Uncertainty creates weakness. Uncertainty makes one tentative, if not fearful, and tentative steps, even when in the right direction, may not overcome significant obstacles.”1

Recently, I spent my vacation time quarantined reading “The Great Influenza,” which recounts the history of the 1918 pandemic. Despite over a century of scientific and medical progress, the parallels to our current situation are indisputable. Just as in 1918, we are limiting social gatherings, quarantining, wearing face masks, and living with the fear and anxiety of keeping ourselves and our families safe. In 1918, use of aspirin, quinine, and digitalis therapies in a desperate search for relief despite limited evidence mirror the current use of hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and lopinavir/ritonavir. While there are many similarities between the two situations, in this pandemic our channels for dissemination of scientific literature are better developed, and online networks are enabling physicians across the globe to communicate their experience and findings in near real time.

During this time of uncertainty, our understanding of COVID-19 evolves daily. Without the advantage of robust randomized, controlled trials and large-scale studies to guide us, we are forced to rely on pattern recognition for surveillance and anecdotal or limited case-based accounts to guide clinical care. Fortunately, free open-access medical education (FOAM) and social networks offer a significant advantage in our ability to collect and disseminate information.

Free open access medical education

The concept of FOAM started in 2012 with the intent of creating a collaborative and constantly evolving community to provide open-access medical education. It encompasses multiple platforms – blogs, podcasts, videos, and social media – and features content experts from across the globe. Since its inception, FOAM has grown in popularity and use, especially within emergency medicine and critical care communities, as an adjunct for asynchronous learning.2,3

In a time where knowledge of COVID-19 is dynamically changing, traditional sources like textbooks, journals, and organizational guidelines often lag behind real-time clinical experience and needs. Additionally, many clinicians are now being tasked with taking care of patient populations and a new critical illness profile with which they are not comfortable. It is challenging to find a well-curated and updated repository of information to answer questions surrounding pathophysiology, critical care, ventilator management, caring for adult patients, and personal protective equipment (PPE). During this rapidly evolving reality, FOAM is becoming the ideal modality for timely and efficient sharing of reviews of current literature, expert discussions, and clinical practice guidelines.

A few self-directed hours on EMCrit’s Internet Book of Critical Care’s COVID-19 chapter reveals a bastion of content regarding diagnosis, pathophysiology, transmission, therapies, and ventilator strategies.4 It includes references to major journals and recommendations from international societies. Websites like EMCrit and REBEL EM are updated daily with podcasts, videos, and blog posts surrounding the latest highly debated topics in COVID-19 management.5 Podcasts like EM:RAP and Peds RAP have made COVID segments discussing important topics like pharmacotherapy, telemedicine, and pregnancy available for free.6,7 Many networks, institutions, and individual physicians have created and posted videos online on critical care topics and refreshers.

Social networks

Online social networks composed of international physicians within Facebook and LinkedIn serve as miniature publishing houses. First-hand accounts of patient presentations and patient care act as case reports. As similar accounts accumulate, they become case series. Patterns emerge and new hypotheses are generated, debated, and critiqued through this informal peer review. Personal accounts of frustration with lack of PPE, fear of exposing loved ones, distress at being separated from family, and grief of witnessing multiple patients die alone are opinion and perspective articles.

These networks offer the space for sharing. Those who have had the experience of caring for the surge of COVID-19 patients offer advice and words of caution to those who have yet to experience it. Protocols from a multitude of institutions on triage, surge, disposition, and end-of-life care are disseminated, serving as templates for those that have not yet developed their own. There is an impressive variety of innovative, do-it-yourself projects surrounding PPE, intubation boxes, and three-dimensionally printed ventilator parts.

Finally, these networks provide emotional support. There are offers to ship additional PPE, videos of cities cheering as clinicians go to work, stories of triumph and recovery, pictures depicting ongoing wellness activities, and the occasional much-needed humorous anecdote or illustration. These networks reinforce the message that our lives continue despite this upheaval, and we are not alone in this struggle.

The end of the passage in The Great Influenza concludes with: “Ultimately a scientist has nothing to believe in but the process of inquiry. To move forcefully and aggressively even while uncertain requires a confidence and strength deeper than physical courage.”

They represent a highly adaptable, evolving, and collaborative global community’s determination to persevere through time of uncertainty together.

Dr. Ren is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. Dr. Simpson is a pediatric emergency medicine attending and medical director of emergency preparedness at the hospital. They reported that they do not have any disclosures or conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Ren and Dr. Simpson at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.” (New York: Penguin Books, 2005, pp. 261-62).

2. Emerg Med J. 2014 Oct;31(e1):e76-7.

3. Acad Med. 2014 Apr;89(4):598-601.

4. “The Internet Book of Critical Care: COVID-19.” EMCrit Project.

5. “Covid-19.” REBEL EM-Emergency Medicine Blog.

6. “EM:RAP COVID-19 Resources.” EM RAP: Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives.

7. “Episodes.” Peds RAP, Hippo Education.

“Uncertainty creates weakness. Uncertainty makes one tentative, if not fearful, and tentative steps, even when in the right direction, may not overcome significant obstacles.”1

Recently, I spent my vacation time quarantined reading “The Great Influenza,” which recounts the history of the 1918 pandemic. Despite over a century of scientific and medical progress, the parallels to our current situation are indisputable. Just as in 1918, we are limiting social gatherings, quarantining, wearing face masks, and living with the fear and anxiety of keeping ourselves and our families safe. In 1918, use of aspirin, quinine, and digitalis therapies in a desperate search for relief despite limited evidence mirror the current use of hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and lopinavir/ritonavir. While there are many similarities between the two situations, in this pandemic our channels for dissemination of scientific literature are better developed, and online networks are enabling physicians across the globe to communicate their experience and findings in near real time.

During this time of uncertainty, our understanding of COVID-19 evolves daily. Without the advantage of robust randomized, controlled trials and large-scale studies to guide us, we are forced to rely on pattern recognition for surveillance and anecdotal or limited case-based accounts to guide clinical care. Fortunately, free open-access medical education (FOAM) and social networks offer a significant advantage in our ability to collect and disseminate information.

Free open access medical education

The concept of FOAM started in 2012 with the intent of creating a collaborative and constantly evolving community to provide open-access medical education. It encompasses multiple platforms – blogs, podcasts, videos, and social media – and features content experts from across the globe. Since its inception, FOAM has grown in popularity and use, especially within emergency medicine and critical care communities, as an adjunct for asynchronous learning.2,3

In a time where knowledge of COVID-19 is dynamically changing, traditional sources like textbooks, journals, and organizational guidelines often lag behind real-time clinical experience and needs. Additionally, many clinicians are now being tasked with taking care of patient populations and a new critical illness profile with which they are not comfortable. It is challenging to find a well-curated and updated repository of information to answer questions surrounding pathophysiology, critical care, ventilator management, caring for adult patients, and personal protective equipment (PPE). During this rapidly evolving reality, FOAM is becoming the ideal modality for timely and efficient sharing of reviews of current literature, expert discussions, and clinical practice guidelines.

A few self-directed hours on EMCrit’s Internet Book of Critical Care’s COVID-19 chapter reveals a bastion of content regarding diagnosis, pathophysiology, transmission, therapies, and ventilator strategies.4 It includes references to major journals and recommendations from international societies. Websites like EMCrit and REBEL EM are updated daily with podcasts, videos, and blog posts surrounding the latest highly debated topics in COVID-19 management.5 Podcasts like EM:RAP and Peds RAP have made COVID segments discussing important topics like pharmacotherapy, telemedicine, and pregnancy available for free.6,7 Many networks, institutions, and individual physicians have created and posted videos online on critical care topics and refreshers.

Social networks

Online social networks composed of international physicians within Facebook and LinkedIn serve as miniature publishing houses. First-hand accounts of patient presentations and patient care act as case reports. As similar accounts accumulate, they become case series. Patterns emerge and new hypotheses are generated, debated, and critiqued through this informal peer review. Personal accounts of frustration with lack of PPE, fear of exposing loved ones, distress at being separated from family, and grief of witnessing multiple patients die alone are opinion and perspective articles.

These networks offer the space for sharing. Those who have had the experience of caring for the surge of COVID-19 patients offer advice and words of caution to those who have yet to experience it. Protocols from a multitude of institutions on triage, surge, disposition, and end-of-life care are disseminated, serving as templates for those that have not yet developed their own. There is an impressive variety of innovative, do-it-yourself projects surrounding PPE, intubation boxes, and three-dimensionally printed ventilator parts.

Finally, these networks provide emotional support. There are offers to ship additional PPE, videos of cities cheering as clinicians go to work, stories of triumph and recovery, pictures depicting ongoing wellness activities, and the occasional much-needed humorous anecdote or illustration. These networks reinforce the message that our lives continue despite this upheaval, and we are not alone in this struggle.

The end of the passage in The Great Influenza concludes with: “Ultimately a scientist has nothing to believe in but the process of inquiry. To move forcefully and aggressively even while uncertain requires a confidence and strength deeper than physical courage.”

They represent a highly adaptable, evolving, and collaborative global community’s determination to persevere through time of uncertainty together.

Dr. Ren is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. Dr. Simpson is a pediatric emergency medicine attending and medical director of emergency preparedness at the hospital. They reported that they do not have any disclosures or conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Ren and Dr. Simpson at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.” (New York: Penguin Books, 2005, pp. 261-62).

2. Emerg Med J. 2014 Oct;31(e1):e76-7.

3. Acad Med. 2014 Apr;89(4):598-601.

4. “The Internet Book of Critical Care: COVID-19.” EMCrit Project.

5. “Covid-19.” REBEL EM-Emergency Medicine Blog.

6. “EM:RAP COVID-19 Resources.” EM RAP: Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives.

7. “Episodes.” Peds RAP, Hippo Education.

FDA approves emergency use of saliva test to detect COVID-19

As the race to develop rapid testing for COVID-19 expands, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency approval for an approach that uses saliva as the primary test biomaterial.

According to a document provided to the FDA, the Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory TaqPath SARS-CoV-2 Assay is intended for the qualitative detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2 in oropharyngeal (throat) swab, nasopharyngeal swab, anterior nasal swab, mid-turbinate nasal swab from individuals suspected of COVID-19 by their health care clinicians. To expand on this assay, Rutgers University–based RUCDR Infinite Biologics developed a saliva collection method in partnership with Spectrum Solutions and Accurate Diagnostic Labs.

The document states that Samples are transported for RNA extraction and are tested within 48 hours of collection. In saliva samples obtained from 60 patients evaluated by the researchers, all were in agreement with the presence of COVID-19.

“If shown to be as accurate as nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal samples, saliva as a biomatrix offers the advantage of not generating aerosols or creating as many respiratory droplets during specimen procurement, therefore decreasing the risk of transmission to the health care worker doing the testing,” said Matthew P. Cheng, MDCM, of the division of infectious diseases at McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, who was not involved in development of the test but who has written about diagnostic testing for the virus.

“Also, it may be easy enough for patients to do saliva self-collection at home. However, it is important to note that SARS-CoV-2 tests on saliva have not yet undergone the more rigorous evaluation of full FDA authorization, and saliva is not a preferred specimen type of the FDA nor the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] for respiratory virus testing.”

In a prepared statement, Andrew I. Brooks, PhD, chief operating officer at RUCDR Infinite Biologics, said the saliva collection method enables clinicians to preserve personal protective equipment for use in patient care instead of testing. “We can significantly increase the number of people tested each and every day as self-collection of saliva is quicker and more scalable than swab collections,” he said. “All of this combined will have a tremendous impact on testing in New Jersey and across the United States.”

The tests are currently available to the RWJBarnabas Health network, based in West Orange, N.J., which has partnered with Rutgers University.

As the race to develop rapid testing for COVID-19 expands, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency approval for an approach that uses saliva as the primary test biomaterial.

According to a document provided to the FDA, the Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory TaqPath SARS-CoV-2 Assay is intended for the qualitative detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2 in oropharyngeal (throat) swab, nasopharyngeal swab, anterior nasal swab, mid-turbinate nasal swab from individuals suspected of COVID-19 by their health care clinicians. To expand on this assay, Rutgers University–based RUCDR Infinite Biologics developed a saliva collection method in partnership with Spectrum Solutions and Accurate Diagnostic Labs.

The document states that Samples are transported for RNA extraction and are tested within 48 hours of collection. In saliva samples obtained from 60 patients evaluated by the researchers, all were in agreement with the presence of COVID-19.

“If shown to be as accurate as nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal samples, saliva as a biomatrix offers the advantage of not generating aerosols or creating as many respiratory droplets during specimen procurement, therefore decreasing the risk of transmission to the health care worker doing the testing,” said Matthew P. Cheng, MDCM, of the division of infectious diseases at McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, who was not involved in development of the test but who has written about diagnostic testing for the virus.

“Also, it may be easy enough for patients to do saliva self-collection at home. However, it is important to note that SARS-CoV-2 tests on saliva have not yet undergone the more rigorous evaluation of full FDA authorization, and saliva is not a preferred specimen type of the FDA nor the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] for respiratory virus testing.”

In a prepared statement, Andrew I. Brooks, PhD, chief operating officer at RUCDR Infinite Biologics, said the saliva collection method enables clinicians to preserve personal protective equipment for use in patient care instead of testing. “We can significantly increase the number of people tested each and every day as self-collection of saliva is quicker and more scalable than swab collections,” he said. “All of this combined will have a tremendous impact on testing in New Jersey and across the United States.”

The tests are currently available to the RWJBarnabas Health network, based in West Orange, N.J., which has partnered with Rutgers University.

As the race to develop rapid testing for COVID-19 expands, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency approval for an approach that uses saliva as the primary test biomaterial.

According to a document provided to the FDA, the Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory TaqPath SARS-CoV-2 Assay is intended for the qualitative detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2 in oropharyngeal (throat) swab, nasopharyngeal swab, anterior nasal swab, mid-turbinate nasal swab from individuals suspected of COVID-19 by their health care clinicians. To expand on this assay, Rutgers University–based RUCDR Infinite Biologics developed a saliva collection method in partnership with Spectrum Solutions and Accurate Diagnostic Labs.

The document states that Samples are transported for RNA extraction and are tested within 48 hours of collection. In saliva samples obtained from 60 patients evaluated by the researchers, all were in agreement with the presence of COVID-19.

“If shown to be as accurate as nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal samples, saliva as a biomatrix offers the advantage of not generating aerosols or creating as many respiratory droplets during specimen procurement, therefore decreasing the risk of transmission to the health care worker doing the testing,” said Matthew P. Cheng, MDCM, of the division of infectious diseases at McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, who was not involved in development of the test but who has written about diagnostic testing for the virus.

“Also, it may be easy enough for patients to do saliva self-collection at home. However, it is important to note that SARS-CoV-2 tests on saliva have not yet undergone the more rigorous evaluation of full FDA authorization, and saliva is not a preferred specimen type of the FDA nor the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] for respiratory virus testing.”

In a prepared statement, Andrew I. Brooks, PhD, chief operating officer at RUCDR Infinite Biologics, said the saliva collection method enables clinicians to preserve personal protective equipment for use in patient care instead of testing. “We can significantly increase the number of people tested each and every day as self-collection of saliva is quicker and more scalable than swab collections,” he said. “All of this combined will have a tremendous impact on testing in New Jersey and across the United States.”

The tests are currently available to the RWJBarnabas Health network, based in West Orange, N.J., which has partnered with Rutgers University.

Learning about the curve

Empty shelves that once cradled toilet paper rolls; lines of shoppers, some with masks; waiting 6 feet or at least a shopping cart length apart to get into grocery stores; hazmat-suited workers loading body bags into makeshift mortuaries ... These are the images we have come to associate with the COVID-19 pandemic. But then there also are the graphs and charts, none of them bearing good news. Some are difficult to interpret because they may be missing a key ingredient, such as a scale. Day to day fluctuations in the timeliness of the data points can make valid comparisons impossible. In most cases, it is too early to look at the graphs and hope for the big picture. Whether you are concerned about the stock market or the number of new cases of the virus in your county, you are hoping to see some graphic depiction of a favorable trend.

We have suddenly learned about the urgency of a process called “flattening the curve.” Are we doing as good a job of flattening as we could be? Are we doing better than France or Spain? Or are we heading toward an Italianesque apocalypse? Who is going to tell us when the flattening is for real and not just a 2- or 3-day statistical aberration?

The curves we are obsessed with today are those showing us new cases and new deaths. But And we won’t be seeing this curve in four-color graphics on the front page of our newspapers. It is the learning curve, and we want it to be as steep as we can make it without any hint of flattening in the foreseeable future.

We need to learn more about corona-like viruses. Why are some of us more vulnerable? We need to learn more about contagion. Does the 6-foot guideline make any sense? How long are viral particles floating in the air capable of initiating disease? What about air flow and dilution? Can we build a cruise ship or airplane that will be less of a health hazard?

More importantly, we need to learn to be better prepared. Even before the pandemic there have been shortages in intravenous solutions and drugs of critical importance to common diseases. Can we learn how to create reliable and affordable supply chains that allow researchers and developers to make a reasonable profit? Can we relearn to value science? Can we learn to invest more heavily in epidemiology and make it a specialty that attracts our best thinkers and communicators? Then can we elect officials who will share our trust in their recommendations?

Can we do a better job of resolving the tension between those who believe in a strong federal government and those who believe in local autonomy because we are seeing every day that this is an issue of survival, not just coexistence? Can we learn that the globalization that has allowed this viral spread can also be leveraged to beat it into submission?

Over the last half century there has been an unfortunate flattening of the learning curve. Ironically we have seen exponential growth among hi-tech industries that have forced us to keep abreast of new developments. But along with this has been a growing skepticism about value of scientific investigation. It is time we climbed back on that steep learning curve. The view gets better the higher we climb.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Empty shelves that once cradled toilet paper rolls; lines of shoppers, some with masks; waiting 6 feet or at least a shopping cart length apart to get into grocery stores; hazmat-suited workers loading body bags into makeshift mortuaries ... These are the images we have come to associate with the COVID-19 pandemic. But then there also are the graphs and charts, none of them bearing good news. Some are difficult to interpret because they may be missing a key ingredient, such as a scale. Day to day fluctuations in the timeliness of the data points can make valid comparisons impossible. In most cases, it is too early to look at the graphs and hope for the big picture. Whether you are concerned about the stock market or the number of new cases of the virus in your county, you are hoping to see some graphic depiction of a favorable trend.

We have suddenly learned about the urgency of a process called “flattening the curve.” Are we doing as good a job of flattening as we could be? Are we doing better than France or Spain? Or are we heading toward an Italianesque apocalypse? Who is going to tell us when the flattening is for real and not just a 2- or 3-day statistical aberration?

The curves we are obsessed with today are those showing us new cases and new deaths. But And we won’t be seeing this curve in four-color graphics on the front page of our newspapers. It is the learning curve, and we want it to be as steep as we can make it without any hint of flattening in the foreseeable future.

We need to learn more about corona-like viruses. Why are some of us more vulnerable? We need to learn more about contagion. Does the 6-foot guideline make any sense? How long are viral particles floating in the air capable of initiating disease? What about air flow and dilution? Can we build a cruise ship or airplane that will be less of a health hazard?

More importantly, we need to learn to be better prepared. Even before the pandemic there have been shortages in intravenous solutions and drugs of critical importance to common diseases. Can we learn how to create reliable and affordable supply chains that allow researchers and developers to make a reasonable profit? Can we relearn to value science? Can we learn to invest more heavily in epidemiology and make it a specialty that attracts our best thinkers and communicators? Then can we elect officials who will share our trust in their recommendations?

Can we do a better job of resolving the tension between those who believe in a strong federal government and those who believe in local autonomy because we are seeing every day that this is an issue of survival, not just coexistence? Can we learn that the globalization that has allowed this viral spread can also be leveraged to beat it into submission?

Over the last half century there has been an unfortunate flattening of the learning curve. Ironically we have seen exponential growth among hi-tech industries that have forced us to keep abreast of new developments. But along with this has been a growing skepticism about value of scientific investigation. It is time we climbed back on that steep learning curve. The view gets better the higher we climb.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Empty shelves that once cradled toilet paper rolls; lines of shoppers, some with masks; waiting 6 feet or at least a shopping cart length apart to get into grocery stores; hazmat-suited workers loading body bags into makeshift mortuaries ... These are the images we have come to associate with the COVID-19 pandemic. But then there also are the graphs and charts, none of them bearing good news. Some are difficult to interpret because they may be missing a key ingredient, such as a scale. Day to day fluctuations in the timeliness of the data points can make valid comparisons impossible. In most cases, it is too early to look at the graphs and hope for the big picture. Whether you are concerned about the stock market or the number of new cases of the virus in your county, you are hoping to see some graphic depiction of a favorable trend.

We have suddenly learned about the urgency of a process called “flattening the curve.” Are we doing as good a job of flattening as we could be? Are we doing better than France or Spain? Or are we heading toward an Italianesque apocalypse? Who is going to tell us when the flattening is for real and not just a 2- or 3-day statistical aberration?

The curves we are obsessed with today are those showing us new cases and new deaths. But And we won’t be seeing this curve in four-color graphics on the front page of our newspapers. It is the learning curve, and we want it to be as steep as we can make it without any hint of flattening in the foreseeable future.

We need to learn more about corona-like viruses. Why are some of us more vulnerable? We need to learn more about contagion. Does the 6-foot guideline make any sense? How long are viral particles floating in the air capable of initiating disease? What about air flow and dilution? Can we build a cruise ship or airplane that will be less of a health hazard?

More importantly, we need to learn to be better prepared. Even before the pandemic there have been shortages in intravenous solutions and drugs of critical importance to common diseases. Can we learn how to create reliable and affordable supply chains that allow researchers and developers to make a reasonable profit? Can we relearn to value science? Can we learn to invest more heavily in epidemiology and make it a specialty that attracts our best thinkers and communicators? Then can we elect officials who will share our trust in their recommendations?

Can we do a better job of resolving the tension between those who believe in a strong federal government and those who believe in local autonomy because we are seeing every day that this is an issue of survival, not just coexistence? Can we learn that the globalization that has allowed this viral spread can also be leveraged to beat it into submission?

Over the last half century there has been an unfortunate flattening of the learning curve. Ironically we have seen exponential growth among hi-tech industries that have forced us to keep abreast of new developments. But along with this has been a growing skepticism about value of scientific investigation. It is time we climbed back on that steep learning curve. The view gets better the higher we climb.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Resources for LGBTQ youth during challenging times

If you are anything like me, March 1 came and went as just another first day of the month. Few of us could have imagined that our day-to-day way of life would soon be upended, and our country would be in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. While there is considerable anxiety around protecting our individual health, social distancing and the physical isolation that comes from it have cut off a vital source of support for many of our lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (or queer) (LGBTQ) youth. Shared experiences with other young people like themselves provide these youth with a sense of community that they may not find in their schools, towns, etc.

LGBTQ youth already face increased rates of anxiety and depression compared with their heterosexual and cisgender peers. According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 63% of LGB youth nationwide reported feeling sad or hopeless compared with 28% of their heterosexual peers. While quarantined at home, many of these youth now are stuck for many more hours per day with families who may not accept them for who they are. Previous research by Ryan et al. shows that LGB adolescents who have higher rates of family rejection are nearly six times more likely to have higher rates of depression and more than eight times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers who come from families with low or no levels of rejection (Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123[1]:346-52). Going to school for roughly 8 hours a day allows some of these youth an escape from what is otherwise an unpleasant home situation. In addition, educators and other school staff may be among the only allies that a student has in his/her life, and school cancellations remove students from access to these important people.

Due to stay-at-home orders and physical distancing measures, lack of in-person access to medical and psychological care can be distressing for many LGBTQ youth. While many practices have been able to convert to audiovisual telemedicine visits, not all of them have the resources or capability to do so. Consequently, LGBTQ youth may have reduced access to support services that help to bolster their social and emotional health. In addition, many trans youth suffer from physical dysphoria that can make it distressing to see themselves on camera doing teletherapy and so they wish to avoid it for this reason.

This is not to say that everything is bleak. LGBTQ youth can also be resilient in times of stress and worry. “The LGBTQ community has a long history of overcoming adversity and utilizing challenges to build an even stronger sense of community. This pandemic will create yet another opportunity for us to highlight existing health disparities and to support our LGBTQ young people in finding creative responses,” said Heather Newby, LCSW, clinical social worker for the GENECIS (GENder Education and Care Interdisciplinary Support) Program at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. In addition, she reported that many LGBTQ advocacy groups have created excellent online support networks and resources to provide nationwide, regional, and local help.

During these challenging times, there are a number of resources that LGBTQ youth can turn to while trying to maintain their connection to their peers. First, many local LGBTQ service organizations have moved their in-person support groups to a virtual or online platform. Check with your local service organization to see what they are offering during these times. National organizations, such as Gender Spectrum, continue to have online groups as well that youth can participate in. Second, many virtual mental health helplines, such as those through the Trevor Project, remain staffed should LGBTQ youth need to access their services (1-866-488-7386, plus text and chat). They can be reached 24/7 to help those whose mental health has been affected during this pandemic. Third, youth can continue to stay connected to their friends through means such as Zoom, FaceTime, or other virtual audiovisual tools. Lastly, some youth have taken to meeting in school parking lots, mall parking lots, etc., and staying at least 6 feet apart so that they can still see their friends in person.

While the current times may be challenging, they will pass and we will be able to return to those activities that bring us joy. Do not hesitate to reach out if you need help. As Rainer Maria Rilke once said, “In the difficult, we must have our joys, our happiness, our dreams: There against the depth of this background, they stand out, there for the first time we see how beautiful they are.”

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Cooper is on Twitter @teendocmbc. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

If you are anything like me, March 1 came and went as just another first day of the month. Few of us could have imagined that our day-to-day way of life would soon be upended, and our country would be in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. While there is considerable anxiety around protecting our individual health, social distancing and the physical isolation that comes from it have cut off a vital source of support for many of our lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (or queer) (LGBTQ) youth. Shared experiences with other young people like themselves provide these youth with a sense of community that they may not find in their schools, towns, etc.

LGBTQ youth already face increased rates of anxiety and depression compared with their heterosexual and cisgender peers. According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 63% of LGB youth nationwide reported feeling sad or hopeless compared with 28% of their heterosexual peers. While quarantined at home, many of these youth now are stuck for many more hours per day with families who may not accept them for who they are. Previous research by Ryan et al. shows that LGB adolescents who have higher rates of family rejection are nearly six times more likely to have higher rates of depression and more than eight times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers who come from families with low or no levels of rejection (Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123[1]:346-52). Going to school for roughly 8 hours a day allows some of these youth an escape from what is otherwise an unpleasant home situation. In addition, educators and other school staff may be among the only allies that a student has in his/her life, and school cancellations remove students from access to these important people.

Due to stay-at-home orders and physical distancing measures, lack of in-person access to medical and psychological care can be distressing for many LGBTQ youth. While many practices have been able to convert to audiovisual telemedicine visits, not all of them have the resources or capability to do so. Consequently, LGBTQ youth may have reduced access to support services that help to bolster their social and emotional health. In addition, many trans youth suffer from physical dysphoria that can make it distressing to see themselves on camera doing teletherapy and so they wish to avoid it for this reason.

This is not to say that everything is bleak. LGBTQ youth can also be resilient in times of stress and worry. “The LGBTQ community has a long history of overcoming adversity and utilizing challenges to build an even stronger sense of community. This pandemic will create yet another opportunity for us to highlight existing health disparities and to support our LGBTQ young people in finding creative responses,” said Heather Newby, LCSW, clinical social worker for the GENECIS (GENder Education and Care Interdisciplinary Support) Program at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. In addition, she reported that many LGBTQ advocacy groups have created excellent online support networks and resources to provide nationwide, regional, and local help.

During these challenging times, there are a number of resources that LGBTQ youth can turn to while trying to maintain their connection to their peers. First, many local LGBTQ service organizations have moved their in-person support groups to a virtual or online platform. Check with your local service organization to see what they are offering during these times. National organizations, such as Gender Spectrum, continue to have online groups as well that youth can participate in. Second, many virtual mental health helplines, such as those through the Trevor Project, remain staffed should LGBTQ youth need to access their services (1-866-488-7386, plus text and chat). They can be reached 24/7 to help those whose mental health has been affected during this pandemic. Third, youth can continue to stay connected to their friends through means such as Zoom, FaceTime, or other virtual audiovisual tools. Lastly, some youth have taken to meeting in school parking lots, mall parking lots, etc., and staying at least 6 feet apart so that they can still see their friends in person.

While the current times may be challenging, they will pass and we will be able to return to those activities that bring us joy. Do not hesitate to reach out if you need help. As Rainer Maria Rilke once said, “In the difficult, we must have our joys, our happiness, our dreams: There against the depth of this background, they stand out, there for the first time we see how beautiful they are.”

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Cooper is on Twitter @teendocmbc. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

If you are anything like me, March 1 came and went as just another first day of the month. Few of us could have imagined that our day-to-day way of life would soon be upended, and our country would be in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. While there is considerable anxiety around protecting our individual health, social distancing and the physical isolation that comes from it have cut off a vital source of support for many of our lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (or queer) (LGBTQ) youth. Shared experiences with other young people like themselves provide these youth with a sense of community that they may not find in their schools, towns, etc.

LGBTQ youth already face increased rates of anxiety and depression compared with their heterosexual and cisgender peers. According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 63% of LGB youth nationwide reported feeling sad or hopeless compared with 28% of their heterosexual peers. While quarantined at home, many of these youth now are stuck for many more hours per day with families who may not accept them for who they are. Previous research by Ryan et al. shows that LGB adolescents who have higher rates of family rejection are nearly six times more likely to have higher rates of depression and more than eight times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers who come from families with low or no levels of rejection (Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123[1]:346-52). Going to school for roughly 8 hours a day allows some of these youth an escape from what is otherwise an unpleasant home situation. In addition, educators and other school staff may be among the only allies that a student has in his/her life, and school cancellations remove students from access to these important people.

Due to stay-at-home orders and physical distancing measures, lack of in-person access to medical and psychological care can be distressing for many LGBTQ youth. While many practices have been able to convert to audiovisual telemedicine visits, not all of them have the resources or capability to do so. Consequently, LGBTQ youth may have reduced access to support services that help to bolster their social and emotional health. In addition, many trans youth suffer from physical dysphoria that can make it distressing to see themselves on camera doing teletherapy and so they wish to avoid it for this reason.

This is not to say that everything is bleak. LGBTQ youth can also be resilient in times of stress and worry. “The LGBTQ community has a long history of overcoming adversity and utilizing challenges to build an even stronger sense of community. This pandemic will create yet another opportunity for us to highlight existing health disparities and to support our LGBTQ young people in finding creative responses,” said Heather Newby, LCSW, clinical social worker for the GENECIS (GENder Education and Care Interdisciplinary Support) Program at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. In addition, she reported that many LGBTQ advocacy groups have created excellent online support networks and resources to provide nationwide, regional, and local help.

During these challenging times, there are a number of resources that LGBTQ youth can turn to while trying to maintain their connection to their peers. First, many local LGBTQ service organizations have moved their in-person support groups to a virtual or online platform. Check with your local service organization to see what they are offering during these times. National organizations, such as Gender Spectrum, continue to have online groups as well that youth can participate in. Second, many virtual mental health helplines, such as those through the Trevor Project, remain staffed should LGBTQ youth need to access their services (1-866-488-7386, plus text and chat). They can be reached 24/7 to help those whose mental health has been affected during this pandemic. Third, youth can continue to stay connected to their friends through means such as Zoom, FaceTime, or other virtual audiovisual tools. Lastly, some youth have taken to meeting in school parking lots, mall parking lots, etc., and staying at least 6 feet apart so that they can still see their friends in person.

While the current times may be challenging, they will pass and we will be able to return to those activities that bring us joy. Do not hesitate to reach out if you need help. As Rainer Maria Rilke once said, “In the difficult, we must have our joys, our happiness, our dreams: There against the depth of this background, they stand out, there for the first time we see how beautiful they are.”

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Cooper is on Twitter @teendocmbc. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

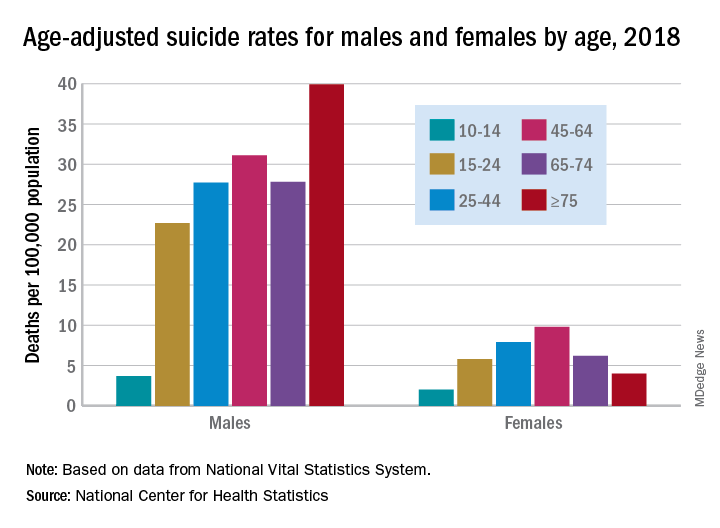

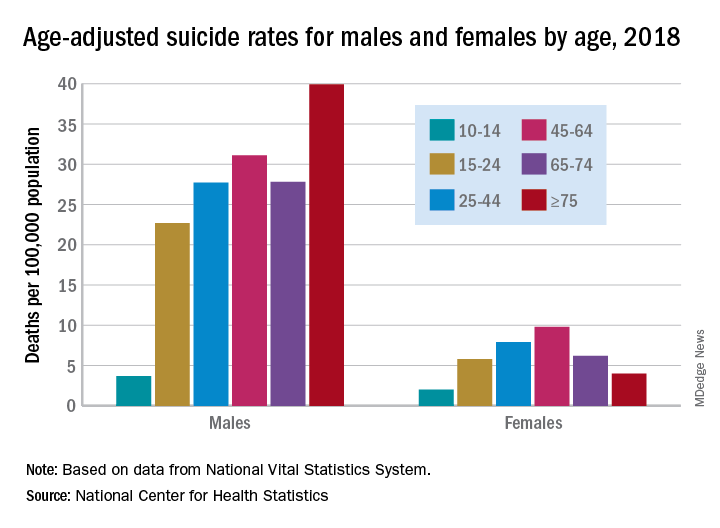

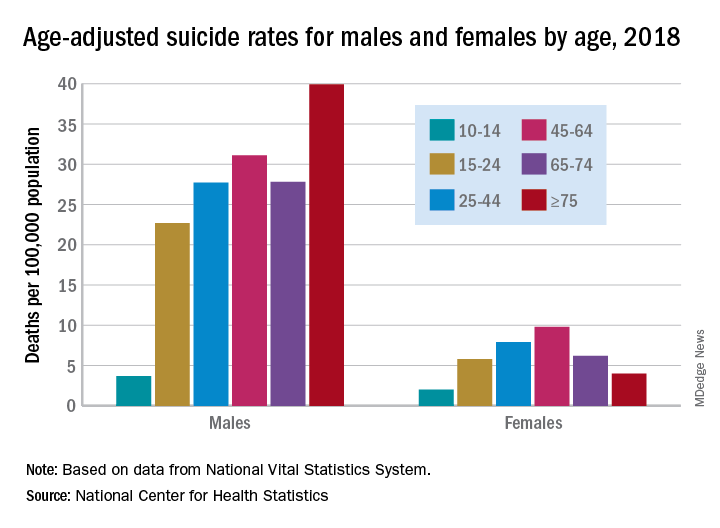

Suicide increased 35% during 1999-2018 in the U.S.

Age-adjusted suicide rate rose from 10.5 per 100,000 to 14.2 from 1999 to 2018, according to trends reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a data brief.

Holly Hedegaard, MD, and colleagues from the National Center for Health Statistics within the CDC analyzed final mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. As the second most common cause of death among Americans aged 10-34 years and the fourth most common among those aged 35-54 years, suicide is a major contributer to premature mortality.

at 22.8 and 6.2 per 100,000, respectively. Young people aged 10-14 years among both genders had the lowest rates of completing suicide, but it was men aged 75 years and older and women aged 45-64 years who had the highest rates. All of these trends were consistent throughout the study period.

Drawing from the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, the researchers found that rural counties had significantly higher rates of suicide than did urban counties in 2018, and this was true for men and women. That said, suicide rates were still 3.5-3.9 times higher among men than among women regardless of urbanicity or rurality that year.

The full data brief can be found on the CDC website.

Age-adjusted suicide rate rose from 10.5 per 100,000 to 14.2 from 1999 to 2018, according to trends reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a data brief.

Holly Hedegaard, MD, and colleagues from the National Center for Health Statistics within the CDC analyzed final mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. As the second most common cause of death among Americans aged 10-34 years and the fourth most common among those aged 35-54 years, suicide is a major contributer to premature mortality.

at 22.8 and 6.2 per 100,000, respectively. Young people aged 10-14 years among both genders had the lowest rates of completing suicide, but it was men aged 75 years and older and women aged 45-64 years who had the highest rates. All of these trends were consistent throughout the study period.

Drawing from the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, the researchers found that rural counties had significantly higher rates of suicide than did urban counties in 2018, and this was true for men and women. That said, suicide rates were still 3.5-3.9 times higher among men than among women regardless of urbanicity or rurality that year.

The full data brief can be found on the CDC website.

Age-adjusted suicide rate rose from 10.5 per 100,000 to 14.2 from 1999 to 2018, according to trends reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a data brief.

Holly Hedegaard, MD, and colleagues from the National Center for Health Statistics within the CDC analyzed final mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. As the second most common cause of death among Americans aged 10-34 years and the fourth most common among those aged 35-54 years, suicide is a major contributer to premature mortality.

at 22.8 and 6.2 per 100,000, respectively. Young people aged 10-14 years among both genders had the lowest rates of completing suicide, but it was men aged 75 years and older and women aged 45-64 years who had the highest rates. All of these trends were consistent throughout the study period.

Drawing from the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, the researchers found that rural counties had significantly higher rates of suicide than did urban counties in 2018, and this was true for men and women. That said, suicide rates were still 3.5-3.9 times higher among men than among women regardless of urbanicity or rurality that year.

The full data brief can be found on the CDC website.

Social distancing comes to the medicine wards

As the coronavirus pandemic has swept across America, so have advisories for social distancing. As of April 2, stay-at-home orders had been given in 38 states and parts of 7 more, affecting about 300 million people. Most of these people have been asked to maintain 6 feet of separation to anyone outside their immediate family and to avoid all avoidable contacts.

Typical hospital medicine patients at an academic hospital, however, traditionally receive visits from their hospitalist, an intern, a resident, and sometimes several medical students, pharmacists, and case managers. At University of California, San Diego, Health, many of these visits would occur during Focused Interdisciplinary Team rounds, with providers moving together in close proximity.

Asymptomatic and presymptomatic spread of coronavirus have been documented, which means distancing is a good idea for everyone. The risks of traditional patient visits during the coronavirus pandemic include spread to both patients (at high risk of complications) and staff (taken out of the workforce during surge times). Even if coronavirus were not a risk, visits to isolation rooms consume PPE, which is in short supply.

In response to the pandemic, UCSD Hospital Medicine drafted guidelines for the reduction of patient contacts. Our slide presentations and written guidelines were then distributed to physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other staff by our pandemic response command center. Key points include the following:

- Target one in-person MD visit per day for stable patients. This means that attending reexaminations of patients seen by residents, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and so on would not be done for billing or teaching purposes, only when clinically necessary.

- Use phone or video conferencing for follow-up discussions unless direct patient contact is needed.

- Consider skipping daily exams on patients who do not require them, such as patients awaiting placement or stably receiving long courses of antibiotics. Interview them remotely or from the door instead.

- Conduct team rounds, patient discussions, and handoffs with all members 6 feet apart or by telephone or video. Avoid shared work rooms. Substitute video conferences for in-person meetings. Use EMR embedded messaging to reduce face-to-face discussions.

- Check if a patient is ready for a visit before donning PPE to avoid waste.

- Explain to patients that distancing is being conducted to protect them. In our experience, when patients are asked about distancing, they welcome the changes.

We have also considered that most patient visits are generated by nurses and assistants. To increase distancing and reduce PPE waste, we have encouraged nurses and pharmacists to maximize their use of remote communication with patients and to suggest changes to care plans and come up with creative solutions to reduce traffic. We specifically suggested the following changes to routine care:

- Reduce frequency of taking vital signs, such as just daily or as needed, in stable patients (for example, those awaiting placement).

- Reduce checks for alcohol withdrawal and neurologic status as soon as possible, and stop fingersticks in patients with well-controlled diabetes not receiving insulin.

- Substitute less frequently administered medications where appropriate if doing so would reduce room traffic (such as enoxaparin for heparin, ceftriaxone for cefazolin, naproxen for ibuprofen, or patient-controlled analgesia for as needed morphine).

- Place intravenous pumps in halls if needed – luckily, our situation has not required these measures in San Diego.

- Explore the possibility of increased patient self-management (self-dosed insulin or inhalers) where medically appropriate.

- Eliminate food service and janitorial trips to isolation rooms unless requested by registered nurse.

There are clear downsides to medical distancing for hospital medicine patients. Patients might have delayed diagnosis of new conditions or inadequate management of conditions requiring frequent assessment, such as alcohol withdrawal. Opportunities for miscommunication (either patient-provider or provider-provider) may be increased with distancing. Isolation also comes with emotional costs such as stress and feelings of isolation or abandonment. Given the dynamic nature of the pandemic response, we are continually reevaluating our distancing guidelines to administer the safest and most effective hospital care possible as we approach California’s expected peak coronavirus infection period.

Dr. Jenkins is professor and chair of the Patient Safety Committee in the Division of Hospital Medicine at UCSD. Dr. Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD division of hospital medicine. Dr. Horman and Dr. Bell are hospitalists and associate professors of medicine at UC San Diego Health.

As the coronavirus pandemic has swept across America, so have advisories for social distancing. As of April 2, stay-at-home orders had been given in 38 states and parts of 7 more, affecting about 300 million people. Most of these people have been asked to maintain 6 feet of separation to anyone outside their immediate family and to avoid all avoidable contacts.

Typical hospital medicine patients at an academic hospital, however, traditionally receive visits from their hospitalist, an intern, a resident, and sometimes several medical students, pharmacists, and case managers. At University of California, San Diego, Health, many of these visits would occur during Focused Interdisciplinary Team rounds, with providers moving together in close proximity.

Asymptomatic and presymptomatic spread of coronavirus have been documented, which means distancing is a good idea for everyone. The risks of traditional patient visits during the coronavirus pandemic include spread to both patients (at high risk of complications) and staff (taken out of the workforce during surge times). Even if coronavirus were not a risk, visits to isolation rooms consume PPE, which is in short supply.

In response to the pandemic, UCSD Hospital Medicine drafted guidelines for the reduction of patient contacts. Our slide presentations and written guidelines were then distributed to physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other staff by our pandemic response command center. Key points include the following:

- Target one in-person MD visit per day for stable patients. This means that attending reexaminations of patients seen by residents, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and so on would not be done for billing or teaching purposes, only when clinically necessary.

- Use phone or video conferencing for follow-up discussions unless direct patient contact is needed.

- Consider skipping daily exams on patients who do not require them, such as patients awaiting placement or stably receiving long courses of antibiotics. Interview them remotely or from the door instead.

- Conduct team rounds, patient discussions, and handoffs with all members 6 feet apart or by telephone or video. Avoid shared work rooms. Substitute video conferences for in-person meetings. Use EMR embedded messaging to reduce face-to-face discussions.

- Check if a patient is ready for a visit before donning PPE to avoid waste.

- Explain to patients that distancing is being conducted to protect them. In our experience, when patients are asked about distancing, they welcome the changes.

We have also considered that most patient visits are generated by nurses and assistants. To increase distancing and reduce PPE waste, we have encouraged nurses and pharmacists to maximize their use of remote communication with patients and to suggest changes to care plans and come up with creative solutions to reduce traffic. We specifically suggested the following changes to routine care:

- Reduce frequency of taking vital signs, such as just daily or as needed, in stable patients (for example, those awaiting placement).

- Reduce checks for alcohol withdrawal and neurologic status as soon as possible, and stop fingersticks in patients with well-controlled diabetes not receiving insulin.

- Substitute less frequently administered medications where appropriate if doing so would reduce room traffic (such as enoxaparin for heparin, ceftriaxone for cefazolin, naproxen for ibuprofen, or patient-controlled analgesia for as needed morphine).

- Place intravenous pumps in halls if needed – luckily, our situation has not required these measures in San Diego.

- Explore the possibility of increased patient self-management (self-dosed insulin or inhalers) where medically appropriate.

- Eliminate food service and janitorial trips to isolation rooms unless requested by registered nurse.

There are clear downsides to medical distancing for hospital medicine patients. Patients might have delayed diagnosis of new conditions or inadequate management of conditions requiring frequent assessment, such as alcohol withdrawal. Opportunities for miscommunication (either patient-provider or provider-provider) may be increased with distancing. Isolation also comes with emotional costs such as stress and feelings of isolation or abandonment. Given the dynamic nature of the pandemic response, we are continually reevaluating our distancing guidelines to administer the safest and most effective hospital care possible as we approach California’s expected peak coronavirus infection period.

Dr. Jenkins is professor and chair of the Patient Safety Committee in the Division of Hospital Medicine at UCSD. Dr. Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD division of hospital medicine. Dr. Horman and Dr. Bell are hospitalists and associate professors of medicine at UC San Diego Health.

As the coronavirus pandemic has swept across America, so have advisories for social distancing. As of April 2, stay-at-home orders had been given in 38 states and parts of 7 more, affecting about 300 million people. Most of these people have been asked to maintain 6 feet of separation to anyone outside their immediate family and to avoid all avoidable contacts.

Typical hospital medicine patients at an academic hospital, however, traditionally receive visits from their hospitalist, an intern, a resident, and sometimes several medical students, pharmacists, and case managers. At University of California, San Diego, Health, many of these visits would occur during Focused Interdisciplinary Team rounds, with providers moving together in close proximity.

Asymptomatic and presymptomatic spread of coronavirus have been documented, which means distancing is a good idea for everyone. The risks of traditional patient visits during the coronavirus pandemic include spread to both patients (at high risk of complications) and staff (taken out of the workforce during surge times). Even if coronavirus were not a risk, visits to isolation rooms consume PPE, which is in short supply.

In response to the pandemic, UCSD Hospital Medicine drafted guidelines for the reduction of patient contacts. Our slide presentations and written guidelines were then distributed to physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other staff by our pandemic response command center. Key points include the following:

- Target one in-person MD visit per day for stable patients. This means that attending reexaminations of patients seen by residents, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and so on would not be done for billing or teaching purposes, only when clinically necessary.

- Use phone or video conferencing for follow-up discussions unless direct patient contact is needed.

- Consider skipping daily exams on patients who do not require them, such as patients awaiting placement or stably receiving long courses of antibiotics. Interview them remotely or from the door instead.

- Conduct team rounds, patient discussions, and handoffs with all members 6 feet apart or by telephone or video. Avoid shared work rooms. Substitute video conferences for in-person meetings. Use EMR embedded messaging to reduce face-to-face discussions.

- Check if a patient is ready for a visit before donning PPE to avoid waste.

- Explain to patients that distancing is being conducted to protect them. In our experience, when patients are asked about distancing, they welcome the changes.

We have also considered that most patient visits are generated by nurses and assistants. To increase distancing and reduce PPE waste, we have encouraged nurses and pharmacists to maximize their use of remote communication with patients and to suggest changes to care plans and come up with creative solutions to reduce traffic. We specifically suggested the following changes to routine care:

- Reduce frequency of taking vital signs, such as just daily or as needed, in stable patients (for example, those awaiting placement).

- Reduce checks for alcohol withdrawal and neurologic status as soon as possible, and stop fingersticks in patients with well-controlled diabetes not receiving insulin.

- Substitute less frequently administered medications where appropriate if doing so would reduce room traffic (such as enoxaparin for heparin, ceftriaxone for cefazolin, naproxen for ibuprofen, or patient-controlled analgesia for as needed morphine).

- Place intravenous pumps in halls if needed – luckily, our situation has not required these measures in San Diego.

- Explore the possibility of increased patient self-management (self-dosed insulin or inhalers) where medically appropriate.

- Eliminate food service and janitorial trips to isolation rooms unless requested by registered nurse.

There are clear downsides to medical distancing for hospital medicine patients. Patients might have delayed diagnosis of new conditions or inadequate management of conditions requiring frequent assessment, such as alcohol withdrawal. Opportunities for miscommunication (either patient-provider or provider-provider) may be increased with distancing. Isolation also comes with emotional costs such as stress and feelings of isolation or abandonment. Given the dynamic nature of the pandemic response, we are continually reevaluating our distancing guidelines to administer the safest and most effective hospital care possible as we approach California’s expected peak coronavirus infection period.

Dr. Jenkins is professor and chair of the Patient Safety Committee in the Division of Hospital Medicine at UCSD. Dr. Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD division of hospital medicine. Dr. Horman and Dr. Bell are hospitalists and associate professors of medicine at UC San Diego Health.

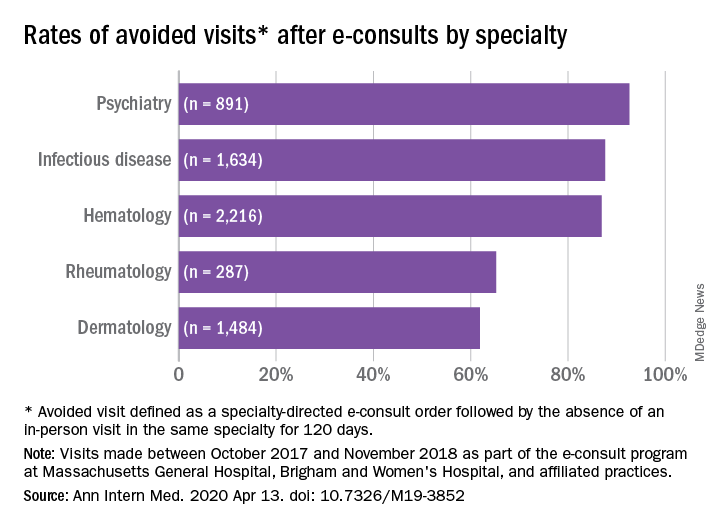

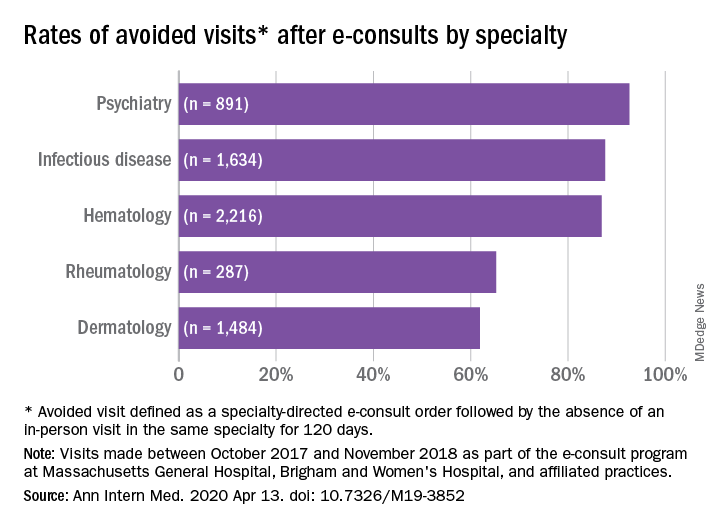

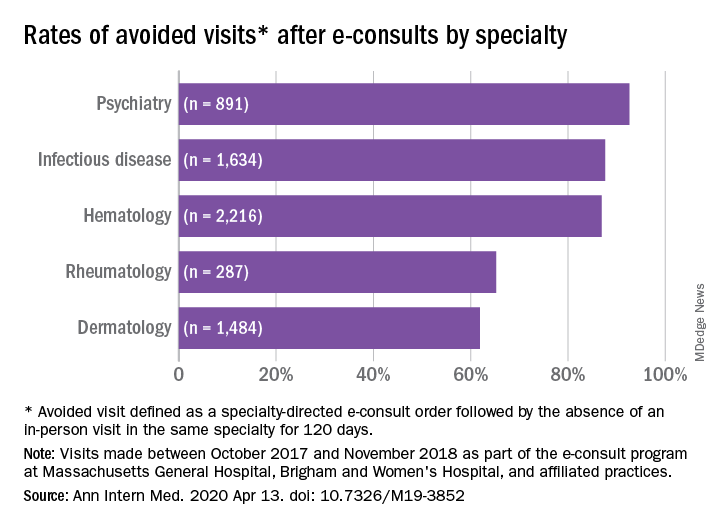

Most e-consults not followed by specialist visit

Studies have shown that e-consults increase access to specialist care and primary care physician (PCP) education, according to research published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (2020. Apr 14. doi: 10.7326/M19-3852) by Salman Ahmed, MD, and colleagues.

These resources are already being frequently used by physicians, but more often by general internists and hospitalists than by subspecialists, according to a recent survey by the American College of Physicians. That survey found that 42% of its respondents are using e-consults and that subspecialists’ use is less common primarily because of the lack of access to e-consult technology.