User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Overuse of Digital Devices in the Exam Room: A Teaching Opportunity

A 3-year-old presents to my clinic for evaluation of a possible autism spectrum disorder/difference. He has a history of severe emotional dysregulation, as well as reduced social skills and multiple sensory sensitivities. When I enter the exam room he is watching videos on his mom’s phone, and has some difficulty transitioning to play with toys when I encourage him to do so. He is eventually able to cooperate with my testing, though a bit reluctantly, and scores within the low average range for both language and pre-academic skills. His neurologic exam is within normal limits. He utilizes reasonably well-modulated eye contact paired with some typical use of gestures, and his affect is moderately directed and reactive. He displays typical intonation and prosody of speech, though engages in less spontaneous, imaginative, and reciprocal play than would be expected for his age. His mother reports decreased pretend play at home, minimal interest in toys, and difficulty playing cooperatively with other children.

Upon further history, it becomes apparent that the child spends a majority of his time on electronic devices, and has done so since early toddlerhood. Further dialogue suggests that the family became isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not yet re-engaged with the community in a meaningful way. The child has had rare opportunity for social interactions with other children, and minimal access to outdoor play. His most severe meltdowns generally involve transitions away from screens, and his overwhelmed parents often resort to use of additional screens to calm him once he is dysregulated.

At the end of the visit, through shared decision making, we agree that enrolling the child in a high-quality public preschool will help parents make a concerted effort towards a significant reduction in the hours per day in which the child utilizes electronic devices, while also providing him more exposure to peers. We plan for the child to return in 6 months for a re-evaluation around social-emotional skills, given his current limited exposure to peers and limited “unplugged” play-time.

Overutilization of Electronic Devices

As clinicians, we can all see how pervasive the use of electronic devices has become in the lives of the families we care for, as well as in our own lives, and how challenging some aspects of modern parenting have become. The developmental impact of early and excessive use of screens in young children is well documented,1 but as clinicians it can be tricky to help empower parents to find ways to limit screen time. When parents use screens to comfort and amuse their children during a clinic visit, this situation may serve as an excellent opportunity for a meaningful and respectful conversation around skill deficits which can result from overutilization of electronic devices in young children.

One scenario I often encounter during my patient evaluations as a developmental and behavioral pediatrician is children begging their parents for use of their phone throughout their visits with me. Not infrequently, a child is already on a screen when I enter the exam room, even when there has been a minimal wait time, which often leads to some resistance on behalf of the child as I explain to the family that a significant portion of the visit involves my interactions with the child, testing the child, and observing their child at play. I always provide ample amounts of age-appropriate art supplies, puzzles, fidgets, building toys, and imaginative play items to children during their 30 to 90 minute evaluations, but these are often not appealing to children when they have been very recently engaged with an electronic device. At times I also need to ask caretakers themselves to please disengage from their own electronic devices during the visit so that I can involve them in a detailed discussion about their child.

One challenge with the practice of allowing children access to entertainment on their parent’s smartphones in particular, lies in the fact that these devices are almost always present, meaning there is no natural boundary to inhibit access, in contrast to a television set or stationary computer parked in the family living room. Not dissimilar to candy visible in a parent’s purse, a cell phone becomes a constant temptation for children accustomed to utilizing them at home and public venues, and the incessant begging can wear down already stressed parents.

Children can become conditioned to utilize the distraction of screens to avoid feelings of discomfort or stress, and so can be very persistent and emotional when asking for the use of screens in public settings. Out in the community, I very frequently see young children and toddlers quietly staring at their phones and tablets while at restaurants and stores. While I have empathy for exhausted parents desperate for a moment of quiet, if this type of screen use is the rule rather than the exception for a child, there is risk for missed opportunities for the development of self-regulation skills.

Additionally, I have seen very young children present to my clinic with poor posture and neck pain secondary to chronic smartphone use, and young children who are getting minimal exercise or outdoor time due to excessive screen use, leading to concerns around fine and gross motor skills as well.

While allowing a child to stay occupied with or be soothed by a highly interesting digital experience can create a more calm environment for all, if habitual, this use can come at a cost regarding opportunities for the growth of executive functioning skills, general coping skills, general situational awareness, and experiential learning. Reliance on screens to decrease uncomfortable experiences decreases the opportunity for building distress tolerance, patience, and coping skills.

Of course there are times of extreme distress where a lollipop or bit of screen time might be reasonable to help keep a child safe or further avoid emotional trauma, but in general, other methods of soothing can very often be utilized, and in the long run would serve to increase the child’s general adaptive functioning.

A Teachable Moment

When clinicians encounter screens being used by parents to entertain their kids in clinic, it provides a valuable teaching moment around the risks of using screens to keep kids regulated and occupied during life’s less interesting or more anxiety provoking experiences. Having a meaningful conversation about the use of electronic devices with caregivers by clinicians in the exam room can be a delicate dance between providing supportive education while avoiding judgmental tones or verbiage. Normalizing and sympathizing with the difficulty of managing challenging behaviors from children in public spaces can help parents feel less desperate to keep their child quiet at all costs, and thus allow for greater development of coping skills.

Some parents may benefit from learning simple ideas for keeping a child regulated and occupied during times of waiting such as silly songs and dances, verbal games like “I spy,” and clapping routines. For a child with additional sensory or developmental needs, a referral to an occupational therapist to work on emotional regulation by way of specific sensory tools can be helpful. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for kids ages 2 to 7 can also help build some relational activities and skills that can be utilized during trying situations to help keep a child settled and occupied.

If a child has qualified for Developmental Disability Services (DDS), medical providers can also write “prescriptions’ for sensory calming items which are often covered financially by DDS, such as chewies, weighted vests, stuffed animals, and fidgets. Encouraging parents to schedule allowed screen time at home in a very predictable and controlled manner is one method to help limit excessive use, as well as it’s utilization as an emotional regulation tool.

For public outings with children with special needs, and in particular in situations where meltdowns are likely to occur, some families find it helpful to dress their children in clothing or accessories that increase community awareness about their child’s condition (such as an autism awareness t-shirt). This effort can also help deflect unhelpful attention or advice from the public. Some parents choose to carry small cards explaining the child’s developmental differences, which can then be easily handed to unsupportive strangers in community settings during trying moments.

Clinicians can work to utilize even quick visits with families as an opportunity to review the American Academy of Pediatrics screen time recommendations with families, and also direct them to the Family Media Plan creation resources. Parenting in the modern era presents many challenges regarding choices around the use of electronic devices with children, and using the exam room experience as a teaching opportunity may be a helpful way to decrease utilization of screens as emotional regulation tools for children, while also providing general education around healthy use of screens.

Dr. Roth is a developmental and behavioral pediatrician in Eugene, Oregon.

Reference

1. Takahashi I et al. Screen Time at Age 1 Year and Communication and Problem-Solving Developmental Delays at 2 and 4 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Oct 1;177(10):1039-1046. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3057.

A 3-year-old presents to my clinic for evaluation of a possible autism spectrum disorder/difference. He has a history of severe emotional dysregulation, as well as reduced social skills and multiple sensory sensitivities. When I enter the exam room he is watching videos on his mom’s phone, and has some difficulty transitioning to play with toys when I encourage him to do so. He is eventually able to cooperate with my testing, though a bit reluctantly, and scores within the low average range for both language and pre-academic skills. His neurologic exam is within normal limits. He utilizes reasonably well-modulated eye contact paired with some typical use of gestures, and his affect is moderately directed and reactive. He displays typical intonation and prosody of speech, though engages in less spontaneous, imaginative, and reciprocal play than would be expected for his age. His mother reports decreased pretend play at home, minimal interest in toys, and difficulty playing cooperatively with other children.

Upon further history, it becomes apparent that the child spends a majority of his time on electronic devices, and has done so since early toddlerhood. Further dialogue suggests that the family became isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not yet re-engaged with the community in a meaningful way. The child has had rare opportunity for social interactions with other children, and minimal access to outdoor play. His most severe meltdowns generally involve transitions away from screens, and his overwhelmed parents often resort to use of additional screens to calm him once he is dysregulated.

At the end of the visit, through shared decision making, we agree that enrolling the child in a high-quality public preschool will help parents make a concerted effort towards a significant reduction in the hours per day in which the child utilizes electronic devices, while also providing him more exposure to peers. We plan for the child to return in 6 months for a re-evaluation around social-emotional skills, given his current limited exposure to peers and limited “unplugged” play-time.

Overutilization of Electronic Devices

As clinicians, we can all see how pervasive the use of electronic devices has become in the lives of the families we care for, as well as in our own lives, and how challenging some aspects of modern parenting have become. The developmental impact of early and excessive use of screens in young children is well documented,1 but as clinicians it can be tricky to help empower parents to find ways to limit screen time. When parents use screens to comfort and amuse their children during a clinic visit, this situation may serve as an excellent opportunity for a meaningful and respectful conversation around skill deficits which can result from overutilization of electronic devices in young children.

One scenario I often encounter during my patient evaluations as a developmental and behavioral pediatrician is children begging their parents for use of their phone throughout their visits with me. Not infrequently, a child is already on a screen when I enter the exam room, even when there has been a minimal wait time, which often leads to some resistance on behalf of the child as I explain to the family that a significant portion of the visit involves my interactions with the child, testing the child, and observing their child at play. I always provide ample amounts of age-appropriate art supplies, puzzles, fidgets, building toys, and imaginative play items to children during their 30 to 90 minute evaluations, but these are often not appealing to children when they have been very recently engaged with an electronic device. At times I also need to ask caretakers themselves to please disengage from their own electronic devices during the visit so that I can involve them in a detailed discussion about their child.

One challenge with the practice of allowing children access to entertainment on their parent’s smartphones in particular, lies in the fact that these devices are almost always present, meaning there is no natural boundary to inhibit access, in contrast to a television set or stationary computer parked in the family living room. Not dissimilar to candy visible in a parent’s purse, a cell phone becomes a constant temptation for children accustomed to utilizing them at home and public venues, and the incessant begging can wear down already stressed parents.

Children can become conditioned to utilize the distraction of screens to avoid feelings of discomfort or stress, and so can be very persistent and emotional when asking for the use of screens in public settings. Out in the community, I very frequently see young children and toddlers quietly staring at their phones and tablets while at restaurants and stores. While I have empathy for exhausted parents desperate for a moment of quiet, if this type of screen use is the rule rather than the exception for a child, there is risk for missed opportunities for the development of self-regulation skills.

Additionally, I have seen very young children present to my clinic with poor posture and neck pain secondary to chronic smartphone use, and young children who are getting minimal exercise or outdoor time due to excessive screen use, leading to concerns around fine and gross motor skills as well.

While allowing a child to stay occupied with or be soothed by a highly interesting digital experience can create a more calm environment for all, if habitual, this use can come at a cost regarding opportunities for the growth of executive functioning skills, general coping skills, general situational awareness, and experiential learning. Reliance on screens to decrease uncomfortable experiences decreases the opportunity for building distress tolerance, patience, and coping skills.

Of course there are times of extreme distress where a lollipop or bit of screen time might be reasonable to help keep a child safe or further avoid emotional trauma, but in general, other methods of soothing can very often be utilized, and in the long run would serve to increase the child’s general adaptive functioning.

A Teachable Moment

When clinicians encounter screens being used by parents to entertain their kids in clinic, it provides a valuable teaching moment around the risks of using screens to keep kids regulated and occupied during life’s less interesting or more anxiety provoking experiences. Having a meaningful conversation about the use of electronic devices with caregivers by clinicians in the exam room can be a delicate dance between providing supportive education while avoiding judgmental tones or verbiage. Normalizing and sympathizing with the difficulty of managing challenging behaviors from children in public spaces can help parents feel less desperate to keep their child quiet at all costs, and thus allow for greater development of coping skills.

Some parents may benefit from learning simple ideas for keeping a child regulated and occupied during times of waiting such as silly songs and dances, verbal games like “I spy,” and clapping routines. For a child with additional sensory or developmental needs, a referral to an occupational therapist to work on emotional regulation by way of specific sensory tools can be helpful. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for kids ages 2 to 7 can also help build some relational activities and skills that can be utilized during trying situations to help keep a child settled and occupied.

If a child has qualified for Developmental Disability Services (DDS), medical providers can also write “prescriptions’ for sensory calming items which are often covered financially by DDS, such as chewies, weighted vests, stuffed animals, and fidgets. Encouraging parents to schedule allowed screen time at home in a very predictable and controlled manner is one method to help limit excessive use, as well as it’s utilization as an emotional regulation tool.

For public outings with children with special needs, and in particular in situations where meltdowns are likely to occur, some families find it helpful to dress their children in clothing or accessories that increase community awareness about their child’s condition (such as an autism awareness t-shirt). This effort can also help deflect unhelpful attention or advice from the public. Some parents choose to carry small cards explaining the child’s developmental differences, which can then be easily handed to unsupportive strangers in community settings during trying moments.

Clinicians can work to utilize even quick visits with families as an opportunity to review the American Academy of Pediatrics screen time recommendations with families, and also direct them to the Family Media Plan creation resources. Parenting in the modern era presents many challenges regarding choices around the use of electronic devices with children, and using the exam room experience as a teaching opportunity may be a helpful way to decrease utilization of screens as emotional regulation tools for children, while also providing general education around healthy use of screens.

Dr. Roth is a developmental and behavioral pediatrician in Eugene, Oregon.

Reference

1. Takahashi I et al. Screen Time at Age 1 Year and Communication and Problem-Solving Developmental Delays at 2 and 4 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Oct 1;177(10):1039-1046. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3057.

A 3-year-old presents to my clinic for evaluation of a possible autism spectrum disorder/difference. He has a history of severe emotional dysregulation, as well as reduced social skills and multiple sensory sensitivities. When I enter the exam room he is watching videos on his mom’s phone, and has some difficulty transitioning to play with toys when I encourage him to do so. He is eventually able to cooperate with my testing, though a bit reluctantly, and scores within the low average range for both language and pre-academic skills. His neurologic exam is within normal limits. He utilizes reasonably well-modulated eye contact paired with some typical use of gestures, and his affect is moderately directed and reactive. He displays typical intonation and prosody of speech, though engages in less spontaneous, imaginative, and reciprocal play than would be expected for his age. His mother reports decreased pretend play at home, minimal interest in toys, and difficulty playing cooperatively with other children.

Upon further history, it becomes apparent that the child spends a majority of his time on electronic devices, and has done so since early toddlerhood. Further dialogue suggests that the family became isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not yet re-engaged with the community in a meaningful way. The child has had rare opportunity for social interactions with other children, and minimal access to outdoor play. His most severe meltdowns generally involve transitions away from screens, and his overwhelmed parents often resort to use of additional screens to calm him once he is dysregulated.

At the end of the visit, through shared decision making, we agree that enrolling the child in a high-quality public preschool will help parents make a concerted effort towards a significant reduction in the hours per day in which the child utilizes electronic devices, while also providing him more exposure to peers. We plan for the child to return in 6 months for a re-evaluation around social-emotional skills, given his current limited exposure to peers and limited “unplugged” play-time.

Overutilization of Electronic Devices

As clinicians, we can all see how pervasive the use of electronic devices has become in the lives of the families we care for, as well as in our own lives, and how challenging some aspects of modern parenting have become. The developmental impact of early and excessive use of screens in young children is well documented,1 but as clinicians it can be tricky to help empower parents to find ways to limit screen time. When parents use screens to comfort and amuse their children during a clinic visit, this situation may serve as an excellent opportunity for a meaningful and respectful conversation around skill deficits which can result from overutilization of electronic devices in young children.

One scenario I often encounter during my patient evaluations as a developmental and behavioral pediatrician is children begging their parents for use of their phone throughout their visits with me. Not infrequently, a child is already on a screen when I enter the exam room, even when there has been a minimal wait time, which often leads to some resistance on behalf of the child as I explain to the family that a significant portion of the visit involves my interactions with the child, testing the child, and observing their child at play. I always provide ample amounts of age-appropriate art supplies, puzzles, fidgets, building toys, and imaginative play items to children during their 30 to 90 minute evaluations, but these are often not appealing to children when they have been very recently engaged with an electronic device. At times I also need to ask caretakers themselves to please disengage from their own electronic devices during the visit so that I can involve them in a detailed discussion about their child.

One challenge with the practice of allowing children access to entertainment on their parent’s smartphones in particular, lies in the fact that these devices are almost always present, meaning there is no natural boundary to inhibit access, in contrast to a television set or stationary computer parked in the family living room. Not dissimilar to candy visible in a parent’s purse, a cell phone becomes a constant temptation for children accustomed to utilizing them at home and public venues, and the incessant begging can wear down already stressed parents.

Children can become conditioned to utilize the distraction of screens to avoid feelings of discomfort or stress, and so can be very persistent and emotional when asking for the use of screens in public settings. Out in the community, I very frequently see young children and toddlers quietly staring at their phones and tablets while at restaurants and stores. While I have empathy for exhausted parents desperate for a moment of quiet, if this type of screen use is the rule rather than the exception for a child, there is risk for missed opportunities for the development of self-regulation skills.

Additionally, I have seen very young children present to my clinic with poor posture and neck pain secondary to chronic smartphone use, and young children who are getting minimal exercise or outdoor time due to excessive screen use, leading to concerns around fine and gross motor skills as well.

While allowing a child to stay occupied with or be soothed by a highly interesting digital experience can create a more calm environment for all, if habitual, this use can come at a cost regarding opportunities for the growth of executive functioning skills, general coping skills, general situational awareness, and experiential learning. Reliance on screens to decrease uncomfortable experiences decreases the opportunity for building distress tolerance, patience, and coping skills.

Of course there are times of extreme distress where a lollipop or bit of screen time might be reasonable to help keep a child safe or further avoid emotional trauma, but in general, other methods of soothing can very often be utilized, and in the long run would serve to increase the child’s general adaptive functioning.

A Teachable Moment

When clinicians encounter screens being used by parents to entertain their kids in clinic, it provides a valuable teaching moment around the risks of using screens to keep kids regulated and occupied during life’s less interesting or more anxiety provoking experiences. Having a meaningful conversation about the use of electronic devices with caregivers by clinicians in the exam room can be a delicate dance between providing supportive education while avoiding judgmental tones or verbiage. Normalizing and sympathizing with the difficulty of managing challenging behaviors from children in public spaces can help parents feel less desperate to keep their child quiet at all costs, and thus allow for greater development of coping skills.

Some parents may benefit from learning simple ideas for keeping a child regulated and occupied during times of waiting such as silly songs and dances, verbal games like “I spy,” and clapping routines. For a child with additional sensory or developmental needs, a referral to an occupational therapist to work on emotional regulation by way of specific sensory tools can be helpful. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for kids ages 2 to 7 can also help build some relational activities and skills that can be utilized during trying situations to help keep a child settled and occupied.

If a child has qualified for Developmental Disability Services (DDS), medical providers can also write “prescriptions’ for sensory calming items which are often covered financially by DDS, such as chewies, weighted vests, stuffed animals, and fidgets. Encouraging parents to schedule allowed screen time at home in a very predictable and controlled manner is one method to help limit excessive use, as well as it’s utilization as an emotional regulation tool.

For public outings with children with special needs, and in particular in situations where meltdowns are likely to occur, some families find it helpful to dress their children in clothing or accessories that increase community awareness about their child’s condition (such as an autism awareness t-shirt). This effort can also help deflect unhelpful attention or advice from the public. Some parents choose to carry small cards explaining the child’s developmental differences, which can then be easily handed to unsupportive strangers in community settings during trying moments.

Clinicians can work to utilize even quick visits with families as an opportunity to review the American Academy of Pediatrics screen time recommendations with families, and also direct them to the Family Media Plan creation resources. Parenting in the modern era presents many challenges regarding choices around the use of electronic devices with children, and using the exam room experience as a teaching opportunity may be a helpful way to decrease utilization of screens as emotional regulation tools for children, while also providing general education around healthy use of screens.

Dr. Roth is a developmental and behavioral pediatrician in Eugene, Oregon.

Reference

1. Takahashi I et al. Screen Time at Age 1 Year and Communication and Problem-Solving Developmental Delays at 2 and 4 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Oct 1;177(10):1039-1046. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3057.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Reduce Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents With Obesity

, a large international retrospective study found.

A study published in JAMA Pediatrics suggested that GLP-1 RAs such as semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide, which are widely used to treat type 2 diabetes (T2D), have a favorable psychiatric safety profile and open up potential avenues for prospective studies of psychiatric outcomes in adolescents with obesity.

Investigators Liya Kerem, MD, MSc, and Joshua Stokar, MD, of Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel, reported that the reduced risk in GLP-1 RA recipients was maintained up to 3 years follow-up compared with propensity score–matched controls treated with behavioral interventions alone.

“These findings support the notion that childhood obesity does not result from lack of willpower and shed light on underlying mechanisms that can be targeted by pharmacotherapy.” Kerem and Stokar wrote.

Other research has suggested these agents have neurobiologic effects unrelated to weight loss that positively affect mood and mental health.

Study Details

The analysis included data from December 2019 to June 2024, drawn from 120 international healthcare organizations, mainly in the United States. A total of 4052 racially and ethnically diverse adolescents with obesity (aged 12-18 years [mean age, about 15.5 years]) being treated with an anti-obesity intervention were identified for the GLP-1 RA cohort and 50,112 for the control cohort. The arms were balanced for baseline demographic characteristics, psychiatric medications and comorbidities, and diagnoses associated with socioeconomic status and healthcare access.

Propensity score matching (PSM) resulted in 3456 participants in each of two balanced cohorts.

Before PSM, intervention patients were older (mean age, 15.5 vs 14.7 years), were more likely to be female (59% vs 49%), and had a higher body mass index (41.9 vs 33.8). They also had a higher prevalence of diabetes (40% vs 4%) and treatment with antidiabetic medications.

GLP-1 RA recipients also had a history of psychiatric diagnoses (17% vs 9% for mood disorders) and psychiatric medications (18% vs 7% for antidepressants). Previous use of non–GLP-1 RA anti-obesity medications was uncommon in the cohort overall, although more common in the GLP-1 RA cohort (2.5% vs 0.2% for phentermine).

Prescription of GLP-1 RA was associated with a 33% reduced risk for suicidal ideation or attempts over 12 months of follow-up: 1.45% vs 2.26% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47-0.95; P = .02). It was also associated with a higher rate of gastrointestinal symptoms: 6.9% vs 5.4% (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.12-1.78; P = .003). There was no difference in rates of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), although some research suggests these agents reduce URTIs.

Mechanisms

The etiology of childhood obesity is complex and multifactorial, the authors wrote, and genetic predisposition to adiposity, an obesogenic environment, and a sedentary lifestyle synergistically contribute to its development. Variants in genes active in the hypothalamic appetite-regulation neurocircuitry appear to be associated with the development of childhood and adolescent obesity.

The authors noted that adolescence carries an increased risk for psychiatric disorders and suicidal ideation. “The amelioration of obesity could indirectly improve these psychiatric comorbidities,” they wrote. In addition, preclinical studies suggested that GLP-1 RA may improve depression-related neuropathology, including neuroinflammation and neurotransmitter imbalance, and may promote neurogenesis.

A recent meta-analysis found that adults with T2D treated with GLP-1 RA showed significant reduction in depression scale scores compared with those treated with non-GLP-1 RA antidiabetic medications.

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, psychiatrist Robert H. Dicker, MD, associate director of child and adolescent psychiatry at Northwell Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, New York, cautioned that these are preliminary data limited by a retrospective review, not a prospective double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

“The mechanism is unknown — is it a direct effect on weight loss with an improvement of quality of life, more positive feedback by the community, enhanced ability to exercise, and a decrease in depressive symptoms?” he asked.

Dicker suggested an alternative hypothesis: Does the GLP-1 RA have a direct effect on neurotransmitters and inflammation and, thus, an impact on mood, emotional regulation, impulse control, and suicide?

“To further answer these questions, prospective studies must be conducted. It is far too early to conclude that these medications are effective in treating mood disorders in our youth,” Dicker said. “But it is promising that these treatments do not appear to increase suicidal ideas and behavior.”

Adding another outsider’s perspective on the study, Suzanne E. Cuda, MD, FOMA, FAAP, a pediatrician who treats childhood obesity in San Antonio, said that while there was no risk for increased psychiatric disease and a suggestion that GLP-1 RAs may reduce suicidal ideation or attempts, “I don’t think this translates to a treatment for depression in adolescents. Nor does this study indicate there could be a decrease in depression due specifically to the use of GLP1Rs. If the results in this study are replicated, however, it would be reassuring to know that adolescents would not be at risk for an increase in suicidal ideation or attempts.”

This study had no external funding. Kerem reported receiving personal fees from Novo Nordisk for lectures on childhood obesity outside of the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Dicker and Cuda had no competing interests relevant to their comments.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large international retrospective study found.

A study published in JAMA Pediatrics suggested that GLP-1 RAs such as semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide, which are widely used to treat type 2 diabetes (T2D), have a favorable psychiatric safety profile and open up potential avenues for prospective studies of psychiatric outcomes in adolescents with obesity.

Investigators Liya Kerem, MD, MSc, and Joshua Stokar, MD, of Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel, reported that the reduced risk in GLP-1 RA recipients was maintained up to 3 years follow-up compared with propensity score–matched controls treated with behavioral interventions alone.

“These findings support the notion that childhood obesity does not result from lack of willpower and shed light on underlying mechanisms that can be targeted by pharmacotherapy.” Kerem and Stokar wrote.

Other research has suggested these agents have neurobiologic effects unrelated to weight loss that positively affect mood and mental health.

Study Details

The analysis included data from December 2019 to June 2024, drawn from 120 international healthcare organizations, mainly in the United States. A total of 4052 racially and ethnically diverse adolescents with obesity (aged 12-18 years [mean age, about 15.5 years]) being treated with an anti-obesity intervention were identified for the GLP-1 RA cohort and 50,112 for the control cohort. The arms were balanced for baseline demographic characteristics, psychiatric medications and comorbidities, and diagnoses associated with socioeconomic status and healthcare access.

Propensity score matching (PSM) resulted in 3456 participants in each of two balanced cohorts.

Before PSM, intervention patients were older (mean age, 15.5 vs 14.7 years), were more likely to be female (59% vs 49%), and had a higher body mass index (41.9 vs 33.8). They also had a higher prevalence of diabetes (40% vs 4%) and treatment with antidiabetic medications.

GLP-1 RA recipients also had a history of psychiatric diagnoses (17% vs 9% for mood disorders) and psychiatric medications (18% vs 7% for antidepressants). Previous use of non–GLP-1 RA anti-obesity medications was uncommon in the cohort overall, although more common in the GLP-1 RA cohort (2.5% vs 0.2% for phentermine).

Prescription of GLP-1 RA was associated with a 33% reduced risk for suicidal ideation or attempts over 12 months of follow-up: 1.45% vs 2.26% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47-0.95; P = .02). It was also associated with a higher rate of gastrointestinal symptoms: 6.9% vs 5.4% (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.12-1.78; P = .003). There was no difference in rates of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), although some research suggests these agents reduce URTIs.

Mechanisms

The etiology of childhood obesity is complex and multifactorial, the authors wrote, and genetic predisposition to adiposity, an obesogenic environment, and a sedentary lifestyle synergistically contribute to its development. Variants in genes active in the hypothalamic appetite-regulation neurocircuitry appear to be associated with the development of childhood and adolescent obesity.

The authors noted that adolescence carries an increased risk for psychiatric disorders and suicidal ideation. “The amelioration of obesity could indirectly improve these psychiatric comorbidities,” they wrote. In addition, preclinical studies suggested that GLP-1 RA may improve depression-related neuropathology, including neuroinflammation and neurotransmitter imbalance, and may promote neurogenesis.

A recent meta-analysis found that adults with T2D treated with GLP-1 RA showed significant reduction in depression scale scores compared with those treated with non-GLP-1 RA antidiabetic medications.

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, psychiatrist Robert H. Dicker, MD, associate director of child and adolescent psychiatry at Northwell Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, New York, cautioned that these are preliminary data limited by a retrospective review, not a prospective double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

“The mechanism is unknown — is it a direct effect on weight loss with an improvement of quality of life, more positive feedback by the community, enhanced ability to exercise, and a decrease in depressive symptoms?” he asked.

Dicker suggested an alternative hypothesis: Does the GLP-1 RA have a direct effect on neurotransmitters and inflammation and, thus, an impact on mood, emotional regulation, impulse control, and suicide?

“To further answer these questions, prospective studies must be conducted. It is far too early to conclude that these medications are effective in treating mood disorders in our youth,” Dicker said. “But it is promising that these treatments do not appear to increase suicidal ideas and behavior.”

Adding another outsider’s perspective on the study, Suzanne E. Cuda, MD, FOMA, FAAP, a pediatrician who treats childhood obesity in San Antonio, said that while there was no risk for increased psychiatric disease and a suggestion that GLP-1 RAs may reduce suicidal ideation or attempts, “I don’t think this translates to a treatment for depression in adolescents. Nor does this study indicate there could be a decrease in depression due specifically to the use of GLP1Rs. If the results in this study are replicated, however, it would be reassuring to know that adolescents would not be at risk for an increase in suicidal ideation or attempts.”

This study had no external funding. Kerem reported receiving personal fees from Novo Nordisk for lectures on childhood obesity outside of the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Dicker and Cuda had no competing interests relevant to their comments.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large international retrospective study found.

A study published in JAMA Pediatrics suggested that GLP-1 RAs such as semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide, which are widely used to treat type 2 diabetes (T2D), have a favorable psychiatric safety profile and open up potential avenues for prospective studies of psychiatric outcomes in adolescents with obesity.

Investigators Liya Kerem, MD, MSc, and Joshua Stokar, MD, of Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel, reported that the reduced risk in GLP-1 RA recipients was maintained up to 3 years follow-up compared with propensity score–matched controls treated with behavioral interventions alone.

“These findings support the notion that childhood obesity does not result from lack of willpower and shed light on underlying mechanisms that can be targeted by pharmacotherapy.” Kerem and Stokar wrote.

Other research has suggested these agents have neurobiologic effects unrelated to weight loss that positively affect mood and mental health.

Study Details

The analysis included data from December 2019 to June 2024, drawn from 120 international healthcare organizations, mainly in the United States. A total of 4052 racially and ethnically diverse adolescents with obesity (aged 12-18 years [mean age, about 15.5 years]) being treated with an anti-obesity intervention were identified for the GLP-1 RA cohort and 50,112 for the control cohort. The arms were balanced for baseline demographic characteristics, psychiatric medications and comorbidities, and diagnoses associated with socioeconomic status and healthcare access.

Propensity score matching (PSM) resulted in 3456 participants in each of two balanced cohorts.

Before PSM, intervention patients were older (mean age, 15.5 vs 14.7 years), were more likely to be female (59% vs 49%), and had a higher body mass index (41.9 vs 33.8). They also had a higher prevalence of diabetes (40% vs 4%) and treatment with antidiabetic medications.

GLP-1 RA recipients also had a history of psychiatric diagnoses (17% vs 9% for mood disorders) and psychiatric medications (18% vs 7% for antidepressants). Previous use of non–GLP-1 RA anti-obesity medications was uncommon in the cohort overall, although more common in the GLP-1 RA cohort (2.5% vs 0.2% for phentermine).

Prescription of GLP-1 RA was associated with a 33% reduced risk for suicidal ideation or attempts over 12 months of follow-up: 1.45% vs 2.26% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47-0.95; P = .02). It was also associated with a higher rate of gastrointestinal symptoms: 6.9% vs 5.4% (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.12-1.78; P = .003). There was no difference in rates of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), although some research suggests these agents reduce URTIs.

Mechanisms

The etiology of childhood obesity is complex and multifactorial, the authors wrote, and genetic predisposition to adiposity, an obesogenic environment, and a sedentary lifestyle synergistically contribute to its development. Variants in genes active in the hypothalamic appetite-regulation neurocircuitry appear to be associated with the development of childhood and adolescent obesity.

The authors noted that adolescence carries an increased risk for psychiatric disorders and suicidal ideation. “The amelioration of obesity could indirectly improve these psychiatric comorbidities,” they wrote. In addition, preclinical studies suggested that GLP-1 RA may improve depression-related neuropathology, including neuroinflammation and neurotransmitter imbalance, and may promote neurogenesis.

A recent meta-analysis found that adults with T2D treated with GLP-1 RA showed significant reduction in depression scale scores compared with those treated with non-GLP-1 RA antidiabetic medications.

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, psychiatrist Robert H. Dicker, MD, associate director of child and adolescent psychiatry at Northwell Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, New York, cautioned that these are preliminary data limited by a retrospective review, not a prospective double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

“The mechanism is unknown — is it a direct effect on weight loss with an improvement of quality of life, more positive feedback by the community, enhanced ability to exercise, and a decrease in depressive symptoms?” he asked.

Dicker suggested an alternative hypothesis: Does the GLP-1 RA have a direct effect on neurotransmitters and inflammation and, thus, an impact on mood, emotional regulation, impulse control, and suicide?

“To further answer these questions, prospective studies must be conducted. It is far too early to conclude that these medications are effective in treating mood disorders in our youth,” Dicker said. “But it is promising that these treatments do not appear to increase suicidal ideas and behavior.”

Adding another outsider’s perspective on the study, Suzanne E. Cuda, MD, FOMA, FAAP, a pediatrician who treats childhood obesity in San Antonio, said that while there was no risk for increased psychiatric disease and a suggestion that GLP-1 RAs may reduce suicidal ideation or attempts, “I don’t think this translates to a treatment for depression in adolescents. Nor does this study indicate there could be a decrease in depression due specifically to the use of GLP1Rs. If the results in this study are replicated, however, it would be reassuring to know that adolescents would not be at risk for an increase in suicidal ideation or attempts.”

This study had no external funding. Kerem reported receiving personal fees from Novo Nordisk for lectures on childhood obesity outside of the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Dicker and Cuda had no competing interests relevant to their comments.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

From JAMA Pediatrics

PCPs Play a Key Role in Managing and Preventing the Atopic March in Children

Primary care physicians (PCPs) play a key role in treating young patients as they progress through the “atopic march” from atopic dermatitis through food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. They can also help prevent the process from starting.

“The PCP is usually the first clinician a family with concerns about atopic conditions sees, unless they first visit urgent care or an emergency department after an allergic reaction to food. Either way, families rely on their PCP for ongoing guidance,” said Terri F. Brown-Whitehorn, MD, attending physician in the Division of Allergy and Immunology at the Center for Pediatric Eosinophilic Disorders and the Integrative Health Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The most important thing PCPs can do is know that the atopic march exists, how it progresses over time, and what signs and symptoms to look for,” she told this news organization.

The Atopic March

The atopic march describes the progression of allergic diseases in a child over time, with atopic dermatitis and food allergy in infancy tending to be followed by allergic rhinitis and asthma into later childhood and adulthood.

Although the pathophysiology of the inflammation that precedes atopic dermatitis is unclear, two main hypotheses have been proposed. The first suggests a primary immune dysfunction leads to immunoglobulin E (IgE) sensitization, allergic inflammation, and a secondary disturbance of the epithelial barrier; the second starts with a primary defect in the epithelial barrier that leads to secondary immunologic dysregulation and results in inflammation.

Genetics, infection, hygiene, extreme climate, food allergens, probiotics, aeroallergens, and tobacco smoke are thought to play roles in atopic dermatitis. An estimated 10%-12% of children and 1% of adults in the United States have been reported to have the condition, and the prevalence appears to be increasing. An estimated 85% of cases occur during the first year of life and 95% before the age of 5 years.

“Atopy often, though not always, runs in families, so PCPs should inquire about the history of atopic dermatitis, IgE-mediated food allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in the patient’s siblings, parents, and grandparents,” Brown-Whitehorn said.

Key Educators

PCPs treat the full gamut of atopic conditions and are key educators on ways families can help mitigate their children’s atopic march or stop it before it begins, said Gerald Bell Lee, MD, an allergist and immunologist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and an associate professor in the Division of Allergy and Immunology at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

“Most parents who bring their infants with eczema to the PCP assume their child ate something that caused their rash. But the relationship between atopic dermatitis, a type of eczema, and food allergy is more complicated,” he added.

Lee said PCPs should explain to their patients what atopic dermatitis is, how it starts and progresses, and how families can help prevent the condition by, for example, introducing allergenic foods to infants at around 4-6 months of age.

Atopic Dermatitis

PCPs should inform parents and other caregivers to wash their hands before moisturizing their child, take care not to contaminate the moisturizer, and bathe their child only when the child is dirty.

“Soap removes protective natural skin oils and increases moisture loss, and exposure to soap and bathing is a main contributor to eczema,” said Lee. “Dry skin loses its protective barrier, allowing outside agents to penetrate and be identified by the immune system.”

“According to one hypothesis, parents may eat food, not wash their hands afterwards, then moisturize their baby. This unhygienic practice spreads food proteins from the adult’s meal, and possibly from contaminants present in the moisturizer, all over the baby’s body,” he added.

Lee said he and his colleagues discourage overbathing babies to minimize the risk for skin injury that begins the atopic march: “New parents are inundated with infant skincare messaging and products. But we need to weigh societal pressures against practicality and ask, ‘Is the child’s skin actually dirty?’ ”

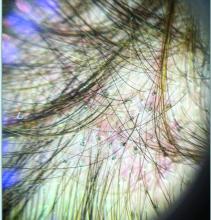

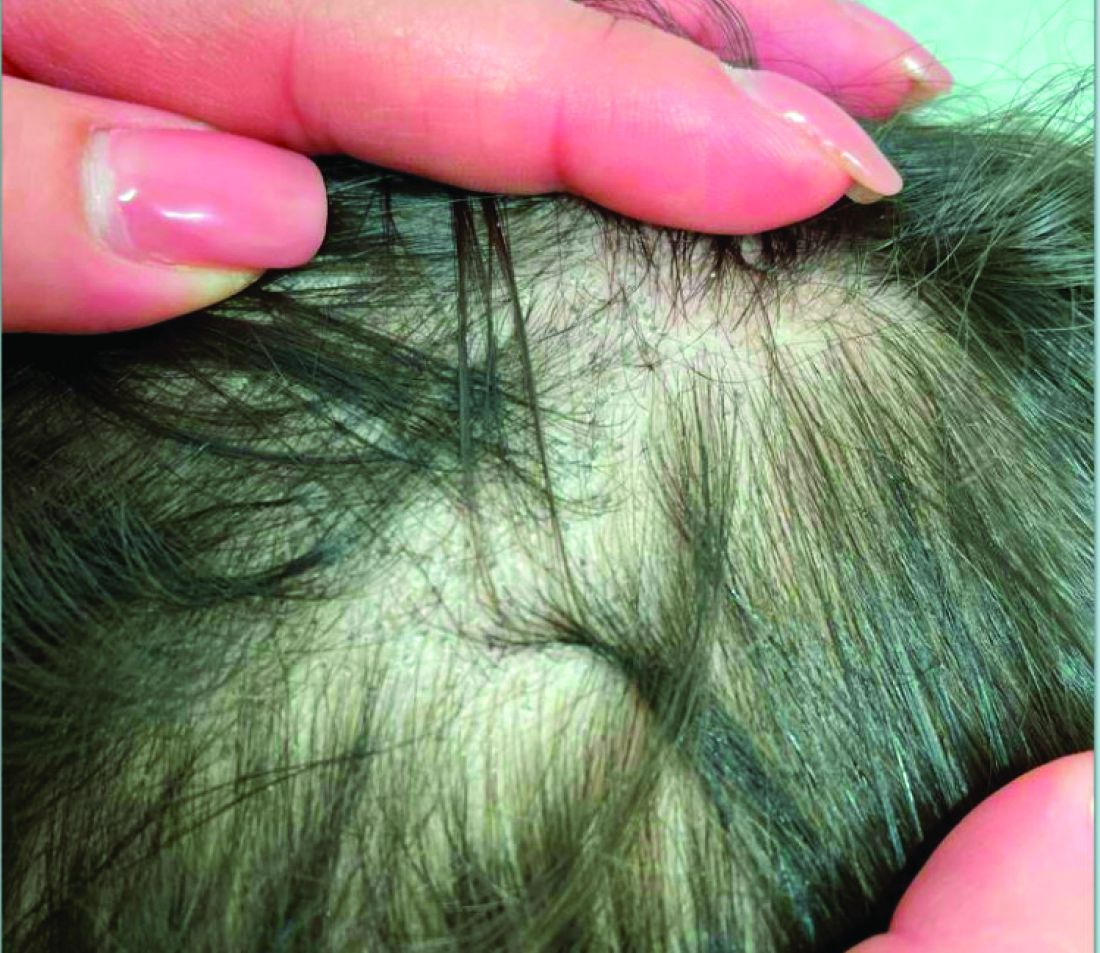

Atopic dermatitis tends to appear on the extensor surfaces, face, and scalp in infants and around arm and leg creases in toddlers and older children. Severe forms of the condition can be more widely distributed on the body, said Aarti P. Pandya, MD, medical director of the Food Allergy Center at Children’s Mercy Kansas City and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri.

Avoid Triggers, Minimize Flares

Triggers of eczema are varied and common. To help minimize flares, PCPs can encourage caregivers to avoid products with fragrances or dyes, minimize the use of soaps, and completely rinse laundry detergent from clothing and household items. “Advise them to keep fingernails short and control dander, pollen, mold, household chemicals, and tobacco smoke, as well as the child’s stress and anxiety, which can also be a trigger,” Lee said.

“Skin infections from organisms such as staph, herpes, or coxsackie can also exacerbate symptoms,” Brown-Whitehorn added. “PCPs can educate caregivers to avoid all known triggers and give them an ‘action plan’ to carry out when skin flares.”

Food Allergies

Parents may be unaware food allergens can travel far beyond the plate, Lee said. Researchers vacuuming household bedding, carpets, furniture, and other surfaces have detected unnoticeably tiny quantities of allergenic food proteins in ordinary house dust. Touching this dust appears to provide the main exposure to those allergens.

“According to the dual exposure to allergen hypothesis, an infant’s tolerance to antigens occurs through high-dose exposure by mouth, and allergic sensitization occurs through low-dose exposure through the skin,” he said. “As young as four to six months of age, even before eating solid food, a child develops eczema, has a leaky skin barrier, comes in contact with food, and develops a food allergy.”

IgE-mediated food allergies can begin at any age. “Symptoms occur when a food is ingested and the patient develops symptoms including but not limited to urticaria, angioedema, pruritus, flushing, vomiting, diarrhea, coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing, presyncope, or syncope,” Pandya noted.

In the case of eosinophilic esophagitis, which may also be part of the atopic march, infants and toddlers often have challenging-to-treat symptoms of reflux, while school-age children have reflux and abdominal pain, and adolescents and adults may experience difficulty swallowing and impactions of food or pills, Brown-Whitehorn said.

To differentiate between food allergy and contact dermatitis, Lee suggested providers ask, “ ’Is the rash hives? If yes, is the rash generalized or in a limited area?’ Then consider the statistical probabilities. Skin problems after milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanut, tree nut, fish, shellfish, or sesame are likely due to IgE-mediated food allergy, but after ketchup or strawberry are probably from skin contact.”

Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma

“For asthma, ask about frequency of night cough and symptoms with exercise, laughing, or crying. For allergic rhinitis, look for runny nose, itchy eyes, or sneezing,” Brown-Whitehorn said.

Testing and Monitoring

Assessing the extent of eczema with the Eczema Area and Severity Index or the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index takes time but may be necessary to obtain insurance coverage for treatments such as biologics.

Avoid ordering IgE food panels, which can result in false positives that can lead to loss of tolerance and nutritional deficiencies; psychological harm from bullying, anxiety, and decreased quality of life; and higher food and healthcare costs, Pandya said.

Treatments

Caregivers may be wary about treatments, and all the three experts this news organization spoke with stressed the importance of educating caregivers about how treatments work and what to expect from them.

“Early and aggressive atopic dermatitis treatment could prevent sensitization to food or aeroallergens, which could help prevent additional atopic diseases, including those on the atopic march,” Pandya said. “Topical steroids are considered first line at any age. Topical phosphodiesterase inhibitors are approved at 3 months of age and above. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are approved at 2 years of age and above. Wet wrap therapy and bleach baths can be effective. Other options include biologic therapy, allergen immunotherapy, and UV therapy.”

“Epinephrine auto-injectors can counteract food reactions. For allergic rhinitis, non-sedating antihistamines, steroidal nasal sprays, and nasal antihistamines help. Asthma treatments include various inhaled medications,” Brown-Whitehorn added.

When to Refer to Specialists

Involving an allergist, dermatologist, pulmonologist, or ear nose throat specialist to the patient’s care team is advisable in more challenging cases.

If a child is younger than 3 months and has moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, an underlying immune defect may be to blame, so an allergy and immunology assessment is warranted, Brown-Whitehorn said. “An allergist can help any child who has recurrent coughing or wheezing avoid the emergency room or hospitalization.”

“In pediatrics, we always try to find the medication, regimen, and avoidance strategies that use the least treatment to provide the best care for each patient,” Brown-Whitehorn added. “Children eat, play, learn, and sleep, and every stage of the atopic march affects each of these activities. As clinicians, we need to be sure that we are helping children make the best of all these activities.”

Brown-Whitehorn reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Lee reported financial relationships with Novartis. Pandya reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) play a key role in treating young patients as they progress through the “atopic march” from atopic dermatitis through food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. They can also help prevent the process from starting.

“The PCP is usually the first clinician a family with concerns about atopic conditions sees, unless they first visit urgent care or an emergency department after an allergic reaction to food. Either way, families rely on their PCP for ongoing guidance,” said Terri F. Brown-Whitehorn, MD, attending physician in the Division of Allergy and Immunology at the Center for Pediatric Eosinophilic Disorders and the Integrative Health Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The most important thing PCPs can do is know that the atopic march exists, how it progresses over time, and what signs and symptoms to look for,” she told this news organization.

The Atopic March

The atopic march describes the progression of allergic diseases in a child over time, with atopic dermatitis and food allergy in infancy tending to be followed by allergic rhinitis and asthma into later childhood and adulthood.

Although the pathophysiology of the inflammation that precedes atopic dermatitis is unclear, two main hypotheses have been proposed. The first suggests a primary immune dysfunction leads to immunoglobulin E (IgE) sensitization, allergic inflammation, and a secondary disturbance of the epithelial barrier; the second starts with a primary defect in the epithelial barrier that leads to secondary immunologic dysregulation and results in inflammation.

Genetics, infection, hygiene, extreme climate, food allergens, probiotics, aeroallergens, and tobacco smoke are thought to play roles in atopic dermatitis. An estimated 10%-12% of children and 1% of adults in the United States have been reported to have the condition, and the prevalence appears to be increasing. An estimated 85% of cases occur during the first year of life and 95% before the age of 5 years.

“Atopy often, though not always, runs in families, so PCPs should inquire about the history of atopic dermatitis, IgE-mediated food allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in the patient’s siblings, parents, and grandparents,” Brown-Whitehorn said.

Key Educators

PCPs treat the full gamut of atopic conditions and are key educators on ways families can help mitigate their children’s atopic march or stop it before it begins, said Gerald Bell Lee, MD, an allergist and immunologist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and an associate professor in the Division of Allergy and Immunology at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

“Most parents who bring their infants with eczema to the PCP assume their child ate something that caused their rash. But the relationship between atopic dermatitis, a type of eczema, and food allergy is more complicated,” he added.

Lee said PCPs should explain to their patients what atopic dermatitis is, how it starts and progresses, and how families can help prevent the condition by, for example, introducing allergenic foods to infants at around 4-6 months of age.

Atopic Dermatitis

PCPs should inform parents and other caregivers to wash their hands before moisturizing their child, take care not to contaminate the moisturizer, and bathe their child only when the child is dirty.

“Soap removes protective natural skin oils and increases moisture loss, and exposure to soap and bathing is a main contributor to eczema,” said Lee. “Dry skin loses its protective barrier, allowing outside agents to penetrate and be identified by the immune system.”

“According to one hypothesis, parents may eat food, not wash their hands afterwards, then moisturize their baby. This unhygienic practice spreads food proteins from the adult’s meal, and possibly from contaminants present in the moisturizer, all over the baby’s body,” he added.

Lee said he and his colleagues discourage overbathing babies to minimize the risk for skin injury that begins the atopic march: “New parents are inundated with infant skincare messaging and products. But we need to weigh societal pressures against practicality and ask, ‘Is the child’s skin actually dirty?’ ”

Atopic dermatitis tends to appear on the extensor surfaces, face, and scalp in infants and around arm and leg creases in toddlers and older children. Severe forms of the condition can be more widely distributed on the body, said Aarti P. Pandya, MD, medical director of the Food Allergy Center at Children’s Mercy Kansas City and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri.

Avoid Triggers, Minimize Flares

Triggers of eczema are varied and common. To help minimize flares, PCPs can encourage caregivers to avoid products with fragrances or dyes, minimize the use of soaps, and completely rinse laundry detergent from clothing and household items. “Advise them to keep fingernails short and control dander, pollen, mold, household chemicals, and tobacco smoke, as well as the child’s stress and anxiety, which can also be a trigger,” Lee said.

“Skin infections from organisms such as staph, herpes, or coxsackie can also exacerbate symptoms,” Brown-Whitehorn added. “PCPs can educate caregivers to avoid all known triggers and give them an ‘action plan’ to carry out when skin flares.”

Food Allergies

Parents may be unaware food allergens can travel far beyond the plate, Lee said. Researchers vacuuming household bedding, carpets, furniture, and other surfaces have detected unnoticeably tiny quantities of allergenic food proteins in ordinary house dust. Touching this dust appears to provide the main exposure to those allergens.

“According to the dual exposure to allergen hypothesis, an infant’s tolerance to antigens occurs through high-dose exposure by mouth, and allergic sensitization occurs through low-dose exposure through the skin,” he said. “As young as four to six months of age, even before eating solid food, a child develops eczema, has a leaky skin barrier, comes in contact with food, and develops a food allergy.”

IgE-mediated food allergies can begin at any age. “Symptoms occur when a food is ingested and the patient develops symptoms including but not limited to urticaria, angioedema, pruritus, flushing, vomiting, diarrhea, coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing, presyncope, or syncope,” Pandya noted.

In the case of eosinophilic esophagitis, which may also be part of the atopic march, infants and toddlers often have challenging-to-treat symptoms of reflux, while school-age children have reflux and abdominal pain, and adolescents and adults may experience difficulty swallowing and impactions of food or pills, Brown-Whitehorn said.

To differentiate between food allergy and contact dermatitis, Lee suggested providers ask, “ ’Is the rash hives? If yes, is the rash generalized or in a limited area?’ Then consider the statistical probabilities. Skin problems after milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanut, tree nut, fish, shellfish, or sesame are likely due to IgE-mediated food allergy, but after ketchup or strawberry are probably from skin contact.”

Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma

“For asthma, ask about frequency of night cough and symptoms with exercise, laughing, or crying. For allergic rhinitis, look for runny nose, itchy eyes, or sneezing,” Brown-Whitehorn said.

Testing and Monitoring

Assessing the extent of eczema with the Eczema Area and Severity Index or the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index takes time but may be necessary to obtain insurance coverage for treatments such as biologics.

Avoid ordering IgE food panels, which can result in false positives that can lead to loss of tolerance and nutritional deficiencies; psychological harm from bullying, anxiety, and decreased quality of life; and higher food and healthcare costs, Pandya said.

Treatments

Caregivers may be wary about treatments, and all the three experts this news organization spoke with stressed the importance of educating caregivers about how treatments work and what to expect from them.

“Early and aggressive atopic dermatitis treatment could prevent sensitization to food or aeroallergens, which could help prevent additional atopic diseases, including those on the atopic march,” Pandya said. “Topical steroids are considered first line at any age. Topical phosphodiesterase inhibitors are approved at 3 months of age and above. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are approved at 2 years of age and above. Wet wrap therapy and bleach baths can be effective. Other options include biologic therapy, allergen immunotherapy, and UV therapy.”

“Epinephrine auto-injectors can counteract food reactions. For allergic rhinitis, non-sedating antihistamines, steroidal nasal sprays, and nasal antihistamines help. Asthma treatments include various inhaled medications,” Brown-Whitehorn added.

When to Refer to Specialists

Involving an allergist, dermatologist, pulmonologist, or ear nose throat specialist to the patient’s care team is advisable in more challenging cases.

If a child is younger than 3 months and has moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, an underlying immune defect may be to blame, so an allergy and immunology assessment is warranted, Brown-Whitehorn said. “An allergist can help any child who has recurrent coughing or wheezing avoid the emergency room or hospitalization.”

“In pediatrics, we always try to find the medication, regimen, and avoidance strategies that use the least treatment to provide the best care for each patient,” Brown-Whitehorn added. “Children eat, play, learn, and sleep, and every stage of the atopic march affects each of these activities. As clinicians, we need to be sure that we are helping children make the best of all these activities.”

Brown-Whitehorn reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Lee reported financial relationships with Novartis. Pandya reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) play a key role in treating young patients as they progress through the “atopic march” from atopic dermatitis through food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. They can also help prevent the process from starting.

“The PCP is usually the first clinician a family with concerns about atopic conditions sees, unless they first visit urgent care or an emergency department after an allergic reaction to food. Either way, families rely on their PCP for ongoing guidance,” said Terri F. Brown-Whitehorn, MD, attending physician in the Division of Allergy and Immunology at the Center for Pediatric Eosinophilic Disorders and the Integrative Health Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The most important thing PCPs can do is know that the atopic march exists, how it progresses over time, and what signs and symptoms to look for,” she told this news organization.

The Atopic March

The atopic march describes the progression of allergic diseases in a child over time, with atopic dermatitis and food allergy in infancy tending to be followed by allergic rhinitis and asthma into later childhood and adulthood.

Although the pathophysiology of the inflammation that precedes atopic dermatitis is unclear, two main hypotheses have been proposed. The first suggests a primary immune dysfunction leads to immunoglobulin E (IgE) sensitization, allergic inflammation, and a secondary disturbance of the epithelial barrier; the second starts with a primary defect in the epithelial barrier that leads to secondary immunologic dysregulation and results in inflammation.

Genetics, infection, hygiene, extreme climate, food allergens, probiotics, aeroallergens, and tobacco smoke are thought to play roles in atopic dermatitis. An estimated 10%-12% of children and 1% of adults in the United States have been reported to have the condition, and the prevalence appears to be increasing. An estimated 85% of cases occur during the first year of life and 95% before the age of 5 years.

“Atopy often, though not always, runs in families, so PCPs should inquire about the history of atopic dermatitis, IgE-mediated food allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in the patient’s siblings, parents, and grandparents,” Brown-Whitehorn said.

Key Educators

PCPs treat the full gamut of atopic conditions and are key educators on ways families can help mitigate their children’s atopic march or stop it before it begins, said Gerald Bell Lee, MD, an allergist and immunologist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and an associate professor in the Division of Allergy and Immunology at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

“Most parents who bring their infants with eczema to the PCP assume their child ate something that caused their rash. But the relationship between atopic dermatitis, a type of eczema, and food allergy is more complicated,” he added.

Lee said PCPs should explain to their patients what atopic dermatitis is, how it starts and progresses, and how families can help prevent the condition by, for example, introducing allergenic foods to infants at around 4-6 months of age.

Atopic Dermatitis

PCPs should inform parents and other caregivers to wash their hands before moisturizing their child, take care not to contaminate the moisturizer, and bathe their child only when the child is dirty.

“Soap removes protective natural skin oils and increases moisture loss, and exposure to soap and bathing is a main contributor to eczema,” said Lee. “Dry skin loses its protective barrier, allowing outside agents to penetrate and be identified by the immune system.”

“According to one hypothesis, parents may eat food, not wash their hands afterwards, then moisturize their baby. This unhygienic practice spreads food proteins from the adult’s meal, and possibly from contaminants present in the moisturizer, all over the baby’s body,” he added.

Lee said he and his colleagues discourage overbathing babies to minimize the risk for skin injury that begins the atopic march: “New parents are inundated with infant skincare messaging and products. But we need to weigh societal pressures against practicality and ask, ‘Is the child’s skin actually dirty?’ ”

Atopic dermatitis tends to appear on the extensor surfaces, face, and scalp in infants and around arm and leg creases in toddlers and older children. Severe forms of the condition can be more widely distributed on the body, said Aarti P. Pandya, MD, medical director of the Food Allergy Center at Children’s Mercy Kansas City and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri.

Avoid Triggers, Minimize Flares

Triggers of eczema are varied and common. To help minimize flares, PCPs can encourage caregivers to avoid products with fragrances or dyes, minimize the use of soaps, and completely rinse laundry detergent from clothing and household items. “Advise them to keep fingernails short and control dander, pollen, mold, household chemicals, and tobacco smoke, as well as the child’s stress and anxiety, which can also be a trigger,” Lee said.

“Skin infections from organisms such as staph, herpes, or coxsackie can also exacerbate symptoms,” Brown-Whitehorn added. “PCPs can educate caregivers to avoid all known triggers and give them an ‘action plan’ to carry out when skin flares.”

Food Allergies

Parents may be unaware food allergens can travel far beyond the plate, Lee said. Researchers vacuuming household bedding, carpets, furniture, and other surfaces have detected unnoticeably tiny quantities of allergenic food proteins in ordinary house dust. Touching this dust appears to provide the main exposure to those allergens.

“According to the dual exposure to allergen hypothesis, an infant’s tolerance to antigens occurs through high-dose exposure by mouth, and allergic sensitization occurs through low-dose exposure through the skin,” he said. “As young as four to six months of age, even before eating solid food, a child develops eczema, has a leaky skin barrier, comes in contact with food, and develops a food allergy.”

IgE-mediated food allergies can begin at any age. “Symptoms occur when a food is ingested and the patient develops symptoms including but not limited to urticaria, angioedema, pruritus, flushing, vomiting, diarrhea, coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing, presyncope, or syncope,” Pandya noted.

In the case of eosinophilic esophagitis, which may also be part of the atopic march, infants and toddlers often have challenging-to-treat symptoms of reflux, while school-age children have reflux and abdominal pain, and adolescents and adults may experience difficulty swallowing and impactions of food or pills, Brown-Whitehorn said.

To differentiate between food allergy and contact dermatitis, Lee suggested providers ask, “ ’Is the rash hives? If yes, is the rash generalized or in a limited area?’ Then consider the statistical probabilities. Skin problems after milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanut, tree nut, fish, shellfish, or sesame are likely due to IgE-mediated food allergy, but after ketchup or strawberry are probably from skin contact.”

Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma

“For asthma, ask about frequency of night cough and symptoms with exercise, laughing, or crying. For allergic rhinitis, look for runny nose, itchy eyes, or sneezing,” Brown-Whitehorn said.

Testing and Monitoring

Assessing the extent of eczema with the Eczema Area and Severity Index or the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index takes time but may be necessary to obtain insurance coverage for treatments such as biologics.

Avoid ordering IgE food panels, which can result in false positives that can lead to loss of tolerance and nutritional deficiencies; psychological harm from bullying, anxiety, and decreased quality of life; and higher food and healthcare costs, Pandya said.

Treatments

Caregivers may be wary about treatments, and all the three experts this news organization spoke with stressed the importance of educating caregivers about how treatments work and what to expect from them.

“Early and aggressive atopic dermatitis treatment could prevent sensitization to food or aeroallergens, which could help prevent additional atopic diseases, including those on the atopic march,” Pandya said. “Topical steroids are considered first line at any age. Topical phosphodiesterase inhibitors are approved at 3 months of age and above. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are approved at 2 years of age and above. Wet wrap therapy and bleach baths can be effective. Other options include biologic therapy, allergen immunotherapy, and UV therapy.”

“Epinephrine auto-injectors can counteract food reactions. For allergic rhinitis, non-sedating antihistamines, steroidal nasal sprays, and nasal antihistamines help. Asthma treatments include various inhaled medications,” Brown-Whitehorn added.

When to Refer to Specialists

Involving an allergist, dermatologist, pulmonologist, or ear nose throat specialist to the patient’s care team is advisable in more challenging cases.

If a child is younger than 3 months and has moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, an underlying immune defect may be to blame, so an allergy and immunology assessment is warranted, Brown-Whitehorn said. “An allergist can help any child who has recurrent coughing or wheezing avoid the emergency room or hospitalization.”

“In pediatrics, we always try to find the medication, regimen, and avoidance strategies that use the least treatment to provide the best care for each patient,” Brown-Whitehorn added. “Children eat, play, learn, and sleep, and every stage of the atopic march affects each of these activities. As clinicians, we need to be sure that we are helping children make the best of all these activities.”

Brown-Whitehorn reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Lee reported financial relationships with Novartis. Pandya reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One-Dose HPV Vaccine Program Would Be Efficient in Canada

In Canada, switching to a one-dose, gender-neutral vaccination program for human papillomavirus (HPV) could use vaccine doses more efficiently and prevent a similar number of cervical cancer cases, compared with a two-dose program, according to a new modeling analysis.

If vaccine protection remains high during the ages of peak sexual activity, all one-dose vaccination options are projected to be “substantially more efficient” than two-dose programs, even in the most pessimistic scenarios, the study authors wrote.

In addition, the scenarios projected the elimination of cervical cancer in Canada between 2032 and 2040. HPV can also lead to oral, throat, and penile cancers, and most are preventable through vaccination.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted HPV vaccination in Canada, particularly among vulnerable population subgroups,” said study author Chantal Sauvageau, MD, a consultant in infectious diseases at the National Institute of Public Health of Quebec and associate professor of social and preventive medicine at the University of Laval, Quebec City, Canada.

Switching to one-dose vaccination would offer potential economic savings and programmatic flexibility, she added. The change also could enable investments aimed at increasing vaccination rates in regions where coverage is suboptimal, as well as in subgroups with a high HPV burden. Such initiatives could mitigate the pandemic’s impact on health programs and reduce inequalities.

The study was published online in CMAJ.

Vaccination Program Changes

Globally, countries have been investigating whether to shift from a two-dose to a one-dose HPV vaccine strategy since the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization issued a single-dose recommendation in 2022.