User login

Choose Your Exam Rules

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

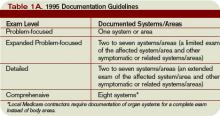

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

No Fee for Errors

State governments, private payors, Medicare, and hospitals have reached the same conclusion: Hospitals should not charge for preventable medical errors.

One of the latest entities to join this trend is Washington state. Early this year, healthcare associations there passed a resolution saying Washington healthcare providers no longer will charge for preventable hospital errors. The resolution applies to 28 “never events” published by the National Quality Forum (NQF). These are medical errors that clearly are identifiable, preventable, serious in their consequences for patients, and indicative of a real problem in the safety and credibility of a healthcare facility. (For a complete list of events, visit NQF’s Web site (www.qualityforum.org/pdf/news/prSeriousReportableEvents10-15-06.pdf).

Hospitals in Massachusetts, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Vermont have adopted similar policies. Private insurers Aetna, Wellpoint, and Blue Cross Blue Shield each are taking steps toward refusing payment for treatment resulting from serious medical errors in hospitals.

Amid these decisions, the American Hospital Association (AHA) released a quality advisory Feb. 12, recommending hospitals implement a no-charge policy for serious adverse errors.

“There’s certainly been a lot of conversation about aligning payment around outcomes,” says Nancy E. Foster, the AHA’s vice president for quality and patient safety policy. “Most of those conversations have focused on reward for doing the right thing, but there were certainly parts of those conversations based on the notion of who’s responsible and who pays when something that was preventable did happen.”

Even the federal government has gotten involved. Beginning in October, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) plans to no longer reimburse for specific preventable conditions.

CMS “Stop Payments”

If Congress approves Medicare’s plan, the CMS will not pay any extra-care costs for eight conditions unless they were present upon admission—and it prohibits hospitals from charging patients for such conditions. The conditions include three “never events”:

- Objects left in the body during surgery (“never event”);

- Air embolism (“never event”);

- Blood incompatibility (“never event”);

- Falls;

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections;

- Pressure ulcers (decubitus ulcers);

- Vascular catheter-associated infection; and

- Surgical site infection after coronary artery bypass graft surgery (mediastinitis).

Next year, the CMS plans to add more conditions to the no-pay list. The most likely additions are ventilator-associated pneumonia, staphylococcus aureus septicemia, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism.

The CMS rule obviously directly affects hospital income, which will affect hospital processes and staff.

“As hospitalists, this affects us,” says Winthrop F. Whitcomb, MD, director of clinical performance improvement at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., director of hospital medicine at Catholic Health East, and co-founder of SHM. “It’s another thing showcasing the value of hospitalists because we tend to document well. When a patient comes in with DVT or a pressure ulcer, we tend to document that, and that will help our hospitals.”

Other physicians may balk at hospital requests to amend or add to their notes to ensure payment, but, says Dr. Whitcomb: “Hospitalists understand the requirement for documentation. If you’re not a hospitalist, you may not be happy to be asked to change your documentation so that the hospital can get paid more, but we understand how important this is.”

Hospitals likely will continue to closely oversee physician documentation on Medicare patients.

“At our hospital, we [already] work with coders,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “I’ve heard of this more and more. They round with us now on every Medicare patient and review the charts. They actually write a formal note that prompts us to document accurately—they may ask us to amend that something was present on admission.” Dr. Whitcomb’s hospital has a paper-based system for this information; an electronic system will include this type of prompt. “Electronic prompts can be customized, but they can also be ignored; prompt fatigue is a big issue,” Dr. Whitcomb warns.

Another potential effect on hospitalists will be involvement in hospital efforts to prevent the eight conditions.

“The CMS change is definitely going to up the ante for quality improvement and patient safety work, no matter who undertakes it,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “It should expand opportunities for hospitalists to work in [quality improvement]. Hospitalists may end up leading teams to specifically address certain never events. The good news is, it gets right at the bottom line of the hospital, so nonclinicians like administrators in the financial office will immediately understand the importance of work like this.”

Leaving a sponge inside a patient is clearly a preventable medical error—but what about pressure ulcers? Or DVT?

In his “Wachter’s World” blog post of Feb. 11 (www.wachtersworld.org), Robert Wachter, MD, professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, addressed the CMS rule.

“For some of the events on the Medicare list, particularly the infections (such as catheter-related bloodstream infections), there is good evidence that the vast majority of events can be prevented,” Dr. Wachter wrote. “For others, such as pressure ulcers and falls, although some commonsensical practices have been widely promoted (particularly through IHI’s 5 Million Lives campaign), the evidence linking adherence to ‘prevention practices’ and reductions in adverse events is tenuous. These adverse events should stay off the list until the evidence is stronger.”

In spite of his misgivings, Dr. Wachter is a strong proponent of the trend toward nonpayment for preventable errors. “We’ve already seen hospitals putting far more resources into trying to prevent line infections, falls, and [pressure ulcers] than they were before,” he says. “And remember that the dollars at stake are relatively small. The extra payments for “Complicating Conditions” (CC) are not enormous, and many patients who have one CC have more than one; in which case, the hospital will still receive the extra payment even if the adverse event-related payment is denied. So, in essence the policy is creating an unusual amount of patient safety momentum for a relatively small displacement of dollars – a pretty clever trick.”

For more information on the CMS rule, read “Medicare’s decision to withhold payment for hospital errors: the devil is in the details,” by Dr. Wachter, Nancy Foster, and Adams Dudley, MD, in the February 2008 Joint Commission Journal of Quality and Patient Safety. TH

Jane Jerrard is a medical writer based in Chicago.

State governments, private payors, Medicare, and hospitals have reached the same conclusion: Hospitals should not charge for preventable medical errors.

One of the latest entities to join this trend is Washington state. Early this year, healthcare associations there passed a resolution saying Washington healthcare providers no longer will charge for preventable hospital errors. The resolution applies to 28 “never events” published by the National Quality Forum (NQF). These are medical errors that clearly are identifiable, preventable, serious in their consequences for patients, and indicative of a real problem in the safety and credibility of a healthcare facility. (For a complete list of events, visit NQF’s Web site (www.qualityforum.org/pdf/news/prSeriousReportableEvents10-15-06.pdf).

Hospitals in Massachusetts, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Vermont have adopted similar policies. Private insurers Aetna, Wellpoint, and Blue Cross Blue Shield each are taking steps toward refusing payment for treatment resulting from serious medical errors in hospitals.

Amid these decisions, the American Hospital Association (AHA) released a quality advisory Feb. 12, recommending hospitals implement a no-charge policy for serious adverse errors.

“There’s certainly been a lot of conversation about aligning payment around outcomes,” says Nancy E. Foster, the AHA’s vice president for quality and patient safety policy. “Most of those conversations have focused on reward for doing the right thing, but there were certainly parts of those conversations based on the notion of who’s responsible and who pays when something that was preventable did happen.”

Even the federal government has gotten involved. Beginning in October, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) plans to no longer reimburse for specific preventable conditions.

CMS “Stop Payments”

If Congress approves Medicare’s plan, the CMS will not pay any extra-care costs for eight conditions unless they were present upon admission—and it prohibits hospitals from charging patients for such conditions. The conditions include three “never events”:

- Objects left in the body during surgery (“never event”);

- Air embolism (“never event”);

- Blood incompatibility (“never event”);

- Falls;

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections;

- Pressure ulcers (decubitus ulcers);

- Vascular catheter-associated infection; and

- Surgical site infection after coronary artery bypass graft surgery (mediastinitis).

Next year, the CMS plans to add more conditions to the no-pay list. The most likely additions are ventilator-associated pneumonia, staphylococcus aureus septicemia, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism.

The CMS rule obviously directly affects hospital income, which will affect hospital processes and staff.

“As hospitalists, this affects us,” says Winthrop F. Whitcomb, MD, director of clinical performance improvement at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., director of hospital medicine at Catholic Health East, and co-founder of SHM. “It’s another thing showcasing the value of hospitalists because we tend to document well. When a patient comes in with DVT or a pressure ulcer, we tend to document that, and that will help our hospitals.”

Other physicians may balk at hospital requests to amend or add to their notes to ensure payment, but, says Dr. Whitcomb: “Hospitalists understand the requirement for documentation. If you’re not a hospitalist, you may not be happy to be asked to change your documentation so that the hospital can get paid more, but we understand how important this is.”

Hospitals likely will continue to closely oversee physician documentation on Medicare patients.

“At our hospital, we [already] work with coders,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “I’ve heard of this more and more. They round with us now on every Medicare patient and review the charts. They actually write a formal note that prompts us to document accurately—they may ask us to amend that something was present on admission.” Dr. Whitcomb’s hospital has a paper-based system for this information; an electronic system will include this type of prompt. “Electronic prompts can be customized, but they can also be ignored; prompt fatigue is a big issue,” Dr. Whitcomb warns.

Another potential effect on hospitalists will be involvement in hospital efforts to prevent the eight conditions.

“The CMS change is definitely going to up the ante for quality improvement and patient safety work, no matter who undertakes it,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “It should expand opportunities for hospitalists to work in [quality improvement]. Hospitalists may end up leading teams to specifically address certain never events. The good news is, it gets right at the bottom line of the hospital, so nonclinicians like administrators in the financial office will immediately understand the importance of work like this.”

Leaving a sponge inside a patient is clearly a preventable medical error—but what about pressure ulcers? Or DVT?

In his “Wachter’s World” blog post of Feb. 11 (www.wachtersworld.org), Robert Wachter, MD, professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, addressed the CMS rule.

“For some of the events on the Medicare list, particularly the infections (such as catheter-related bloodstream infections), there is good evidence that the vast majority of events can be prevented,” Dr. Wachter wrote. “For others, such as pressure ulcers and falls, although some commonsensical practices have been widely promoted (particularly through IHI’s 5 Million Lives campaign), the evidence linking adherence to ‘prevention practices’ and reductions in adverse events is tenuous. These adverse events should stay off the list until the evidence is stronger.”

In spite of his misgivings, Dr. Wachter is a strong proponent of the trend toward nonpayment for preventable errors. “We’ve already seen hospitals putting far more resources into trying to prevent line infections, falls, and [pressure ulcers] than they were before,” he says. “And remember that the dollars at stake are relatively small. The extra payments for “Complicating Conditions” (CC) are not enormous, and many patients who have one CC have more than one; in which case, the hospital will still receive the extra payment even if the adverse event-related payment is denied. So, in essence the policy is creating an unusual amount of patient safety momentum for a relatively small displacement of dollars – a pretty clever trick.”

For more information on the CMS rule, read “Medicare’s decision to withhold payment for hospital errors: the devil is in the details,” by Dr. Wachter, Nancy Foster, and Adams Dudley, MD, in the February 2008 Joint Commission Journal of Quality and Patient Safety. TH

Jane Jerrard is a medical writer based in Chicago.

State governments, private payors, Medicare, and hospitals have reached the same conclusion: Hospitals should not charge for preventable medical errors.

One of the latest entities to join this trend is Washington state. Early this year, healthcare associations there passed a resolution saying Washington healthcare providers no longer will charge for preventable hospital errors. The resolution applies to 28 “never events” published by the National Quality Forum (NQF). These are medical errors that clearly are identifiable, preventable, serious in their consequences for patients, and indicative of a real problem in the safety and credibility of a healthcare facility. (For a complete list of events, visit NQF’s Web site (www.qualityforum.org/pdf/news/prSeriousReportableEvents10-15-06.pdf).

Hospitals in Massachusetts, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Vermont have adopted similar policies. Private insurers Aetna, Wellpoint, and Blue Cross Blue Shield each are taking steps toward refusing payment for treatment resulting from serious medical errors in hospitals.

Amid these decisions, the American Hospital Association (AHA) released a quality advisory Feb. 12, recommending hospitals implement a no-charge policy for serious adverse errors.

“There’s certainly been a lot of conversation about aligning payment around outcomes,” says Nancy E. Foster, the AHA’s vice president for quality and patient safety policy. “Most of those conversations have focused on reward for doing the right thing, but there were certainly parts of those conversations based on the notion of who’s responsible and who pays when something that was preventable did happen.”

Even the federal government has gotten involved. Beginning in October, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) plans to no longer reimburse for specific preventable conditions.

CMS “Stop Payments”

If Congress approves Medicare’s plan, the CMS will not pay any extra-care costs for eight conditions unless they were present upon admission—and it prohibits hospitals from charging patients for such conditions. The conditions include three “never events”:

- Objects left in the body during surgery (“never event”);

- Air embolism (“never event”);

- Blood incompatibility (“never event”);

- Falls;

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections;

- Pressure ulcers (decubitus ulcers);

- Vascular catheter-associated infection; and

- Surgical site infection after coronary artery bypass graft surgery (mediastinitis).

Next year, the CMS plans to add more conditions to the no-pay list. The most likely additions are ventilator-associated pneumonia, staphylococcus aureus septicemia, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism.

The CMS rule obviously directly affects hospital income, which will affect hospital processes and staff.

“As hospitalists, this affects us,” says Winthrop F. Whitcomb, MD, director of clinical performance improvement at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., director of hospital medicine at Catholic Health East, and co-founder of SHM. “It’s another thing showcasing the value of hospitalists because we tend to document well. When a patient comes in with DVT or a pressure ulcer, we tend to document that, and that will help our hospitals.”

Other physicians may balk at hospital requests to amend or add to their notes to ensure payment, but, says Dr. Whitcomb: “Hospitalists understand the requirement for documentation. If you’re not a hospitalist, you may not be happy to be asked to change your documentation so that the hospital can get paid more, but we understand how important this is.”

Hospitals likely will continue to closely oversee physician documentation on Medicare patients.

“At our hospital, we [already] work with coders,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “I’ve heard of this more and more. They round with us now on every Medicare patient and review the charts. They actually write a formal note that prompts us to document accurately—they may ask us to amend that something was present on admission.” Dr. Whitcomb’s hospital has a paper-based system for this information; an electronic system will include this type of prompt. “Electronic prompts can be customized, but they can also be ignored; prompt fatigue is a big issue,” Dr. Whitcomb warns.

Another potential effect on hospitalists will be involvement in hospital efforts to prevent the eight conditions.

“The CMS change is definitely going to up the ante for quality improvement and patient safety work, no matter who undertakes it,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “It should expand opportunities for hospitalists to work in [quality improvement]. Hospitalists may end up leading teams to specifically address certain never events. The good news is, it gets right at the bottom line of the hospital, so nonclinicians like administrators in the financial office will immediately understand the importance of work like this.”

Leaving a sponge inside a patient is clearly a preventable medical error—but what about pressure ulcers? Or DVT?

In his “Wachter’s World” blog post of Feb. 11 (www.wachtersworld.org), Robert Wachter, MD, professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, addressed the CMS rule.

“For some of the events on the Medicare list, particularly the infections (such as catheter-related bloodstream infections), there is good evidence that the vast majority of events can be prevented,” Dr. Wachter wrote. “For others, such as pressure ulcers and falls, although some commonsensical practices have been widely promoted (particularly through IHI’s 5 Million Lives campaign), the evidence linking adherence to ‘prevention practices’ and reductions in adverse events is tenuous. These adverse events should stay off the list until the evidence is stronger.”

In spite of his misgivings, Dr. Wachter is a strong proponent of the trend toward nonpayment for preventable errors. “We’ve already seen hospitals putting far more resources into trying to prevent line infections, falls, and [pressure ulcers] than they were before,” he says. “And remember that the dollars at stake are relatively small. The extra payments for “Complicating Conditions” (CC) are not enormous, and many patients who have one CC have more than one; in which case, the hospital will still receive the extra payment even if the adverse event-related payment is denied. So, in essence the policy is creating an unusual amount of patient safety momentum for a relatively small displacement of dollars – a pretty clever trick.”

For more information on the CMS rule, read “Medicare’s decision to withhold payment for hospital errors: the devil is in the details,” by Dr. Wachter, Nancy Foster, and Adams Dudley, MD, in the February 2008 Joint Commission Journal of Quality and Patient Safety. TH

Jane Jerrard is a medical writer based in Chicago.

Mentorship Essentials

You may have had a mentor as a resident and possibly in your first year as a hospitalist, but don’t count out these valuable resources as you continue in your career. And don’t count out mentors who may come from other walks of life.

“It’s natural for physicians to look toward other physicians for guidance,” says Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer for Cogent Healthcare, Nashville. “For physicians, including hospitalists, their natural inclination is to seek mentors who are physicians or have a similar training background. While there are many great physician mentors, you may be limiting yourself and missing opportunities that come from broader mentoring.”

Informal mentoring relationships are an excellent way to learn all sorts of leadership skills, from the subtle—like handling complains about a physician’s constant body odor—to hard skills, such as putting together a budget for your department or practice.

—Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer, Cogent Healthcare, Nashville

Management Mentors

Dr. Holman identified people at various stages in his career who could impart skills he sought, from a vice president of [human relations] for an integrated health system who steered him on personnel management and leadership development, to a carpenter-turned-attorney who helped him hone critical thinking skills.

“Talking to a mentor can show you the fresh side of new or old situations,” says Dr. Holman. “And you can feel comfortable telling them things that you wouldn’t tell anyone else. [When] you don’t work together, it provides a safe harbor to express ideas and opinions you normally wouldn’t.”

Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, chief executive officer of Advanced ICU Care in St. Louis, Mo., agrees. “If you want someone to bounce ideas off of, try to find someone outside your organization,” she advises. She recommends physician organizations such as SHM: “Find someone who will listen, can keep their mouth shut and give you some honest feedback. For that reason, I’m a fan of professional coaches and career counselors. They provide an objective and unbiased audience and can suggest straightforward ways to manage sensitive issues.”

You also can find valuable mentors inside your workplace. “An often overlooked resource for hospitalist leaders is the other managers in their facilities,” says Dr. Gorman. “When I was a new manager, one of my mentors was the director of nursing. We could toss ideas back and forth, and she knew the politics and the personalities of the place, knew what mattered and what didn’t, and could steer me in the right direction.”

The managers and directors you work with, regardless of whether they’re physicians, are likely to have a lot of management experience, and can be resources for on-the-spot advice and guidance.

“Depending on the situation, even a chief operating officer or CEO of your hospital can give you good ideas and help you,” adds Dr. Gorman. “You’re a hospitalist; they’re supposed to be on your side. And they may be just five or 10 years older than you, but they have a lot of people management experience under their belts.”

They’re Everywhere

If you look beyond physicians and other healthcare professionals, finding an informal mentor is simply a matter of keeping your eyes and your mind open.

“You find a mentor by being in different situations,” Dr. Holman says. “Take advantage of getting to know people in different spheres, see what makes them tick that you can learn and apply to yourself.”

Consider all aspects of your life outside the workplace—your neighborhood, your church, your children’s school, any organizations you volunteer for, or social venues. Even your family—does anyone have management or business experience?

Keep your options open for learning from others, but if you have a specific area where you want to gain knowledge, you can search your circle of acquaintances to see who might be able to fill in that gap.

“Outside of healthcare, my personal accountant was a huge help,” says Dr. Gorman. “He sat down with me and helped me understand the financials I was supposed to do. You may have to pay for this service, but if you’re just asking for a few hours of their time and you have a good relationship, they’ll help you out.”

Regardless of what you want to learn, keep in mind that mentors can come in any shape and form. “A mentor can be someone younger than you, someone less well educated,” Dr. Holman points out. “What matters is when you recognize the value of the perspectives they bring.”

In fact, Dr. Holman says, he deliberately looks for people who are a little different from himself. “We tend to gravitate to those who are like us, but [in mentoring] this doesn’t lend itself to the greatest growth long-term,” he explains.

Make Mentoring Work

When you target someone as a potential mentor, it’s best to start with occasional questions and keep the relationship casual.

“My experience—and this is supported by literature—is that mentoring relationships are most solid when they form naturally,” Dr. Holman says. “The mentorship arena lends itself to flexibility and informal structure.”

Dr. Gorman agrees, suggesting that you not even mention “the M word.” “In my experience, asking someone flat out if they’ll be your mentor doesn’t really work,” Dr. Gorman says. “It sounds like a big commitment, and they shy away from it. Instead, I’d say just keep going back to the same people for guidance. Find those people who will listen to you and give you some help.”

Once you establish a mentoring relationship, try to find a way to return the favor—at least by being a good mentee.

“It’s particularly rewarding when mentoring is not one-sided, when each person has something to bring to the table,” Dr. Holman says. “Though it may be mostly one-sided, it’s good to be able to give some advice or counsel in return.”

Dr. Gorman adds that a good mentee either will act on advice or address why they didn’t. “No one likes to give advice just to see you blow it off, or head straight into a situation they warned you against,” she stresses. “Be respectful of their time, and be prepared when you present a problem. And be sure to thank them. You don’t have to send flowers or anything, just a verbal thank you for their time.”

No matter what stage your career is in, you can always pick up new skills and perspectives—particularly if you’re in a leadership position. Even if you feel you’re well established, finding new mentors can only make you better at what you do.

“You should always look for someone to learn from,” Dr. Gorman says. “They’re out there, no matter where you are or what you’re doing. Throw out some questions and see who you hit it off with, who gives you sound advice.” TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

You may have had a mentor as a resident and possibly in your first year as a hospitalist, but don’t count out these valuable resources as you continue in your career. And don’t count out mentors who may come from other walks of life.

“It’s natural for physicians to look toward other physicians for guidance,” says Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer for Cogent Healthcare, Nashville. “For physicians, including hospitalists, their natural inclination is to seek mentors who are physicians or have a similar training background. While there are many great physician mentors, you may be limiting yourself and missing opportunities that come from broader mentoring.”

Informal mentoring relationships are an excellent way to learn all sorts of leadership skills, from the subtle—like handling complains about a physician’s constant body odor—to hard skills, such as putting together a budget for your department or practice.

—Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer, Cogent Healthcare, Nashville

Management Mentors

Dr. Holman identified people at various stages in his career who could impart skills he sought, from a vice president of [human relations] for an integrated health system who steered him on personnel management and leadership development, to a carpenter-turned-attorney who helped him hone critical thinking skills.

“Talking to a mentor can show you the fresh side of new or old situations,” says Dr. Holman. “And you can feel comfortable telling them things that you wouldn’t tell anyone else. [When] you don’t work together, it provides a safe harbor to express ideas and opinions you normally wouldn’t.”

Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, chief executive officer of Advanced ICU Care in St. Louis, Mo., agrees. “If you want someone to bounce ideas off of, try to find someone outside your organization,” she advises. She recommends physician organizations such as SHM: “Find someone who will listen, can keep their mouth shut and give you some honest feedback. For that reason, I’m a fan of professional coaches and career counselors. They provide an objective and unbiased audience and can suggest straightforward ways to manage sensitive issues.”

You also can find valuable mentors inside your workplace. “An often overlooked resource for hospitalist leaders is the other managers in their facilities,” says Dr. Gorman. “When I was a new manager, one of my mentors was the director of nursing. We could toss ideas back and forth, and she knew the politics and the personalities of the place, knew what mattered and what didn’t, and could steer me in the right direction.”

The managers and directors you work with, regardless of whether they’re physicians, are likely to have a lot of management experience, and can be resources for on-the-spot advice and guidance.

“Depending on the situation, even a chief operating officer or CEO of your hospital can give you good ideas and help you,” adds Dr. Gorman. “You’re a hospitalist; they’re supposed to be on your side. And they may be just five or 10 years older than you, but they have a lot of people management experience under their belts.”

They’re Everywhere

If you look beyond physicians and other healthcare professionals, finding an informal mentor is simply a matter of keeping your eyes and your mind open.

“You find a mentor by being in different situations,” Dr. Holman says. “Take advantage of getting to know people in different spheres, see what makes them tick that you can learn and apply to yourself.”

Consider all aspects of your life outside the workplace—your neighborhood, your church, your children’s school, any organizations you volunteer for, or social venues. Even your family—does anyone have management or business experience?

Keep your options open for learning from others, but if you have a specific area where you want to gain knowledge, you can search your circle of acquaintances to see who might be able to fill in that gap.

“Outside of healthcare, my personal accountant was a huge help,” says Dr. Gorman. “He sat down with me and helped me understand the financials I was supposed to do. You may have to pay for this service, but if you’re just asking for a few hours of their time and you have a good relationship, they’ll help you out.”

Regardless of what you want to learn, keep in mind that mentors can come in any shape and form. “A mentor can be someone younger than you, someone less well educated,” Dr. Holman points out. “What matters is when you recognize the value of the perspectives they bring.”

In fact, Dr. Holman says, he deliberately looks for people who are a little different from himself. “We tend to gravitate to those who are like us, but [in mentoring] this doesn’t lend itself to the greatest growth long-term,” he explains.

Make Mentoring Work

When you target someone as a potential mentor, it’s best to start with occasional questions and keep the relationship casual.

“My experience—and this is supported by literature—is that mentoring relationships are most solid when they form naturally,” Dr. Holman says. “The mentorship arena lends itself to flexibility and informal structure.”

Dr. Gorman agrees, suggesting that you not even mention “the M word.” “In my experience, asking someone flat out if they’ll be your mentor doesn’t really work,” Dr. Gorman says. “It sounds like a big commitment, and they shy away from it. Instead, I’d say just keep going back to the same people for guidance. Find those people who will listen to you and give you some help.”

Once you establish a mentoring relationship, try to find a way to return the favor—at least by being a good mentee.

“It’s particularly rewarding when mentoring is not one-sided, when each person has something to bring to the table,” Dr. Holman says. “Though it may be mostly one-sided, it’s good to be able to give some advice or counsel in return.”

Dr. Gorman adds that a good mentee either will act on advice or address why they didn’t. “No one likes to give advice just to see you blow it off, or head straight into a situation they warned you against,” she stresses. “Be respectful of their time, and be prepared when you present a problem. And be sure to thank them. You don’t have to send flowers or anything, just a verbal thank you for their time.”

No matter what stage your career is in, you can always pick up new skills and perspectives—particularly if you’re in a leadership position. Even if you feel you’re well established, finding new mentors can only make you better at what you do.

“You should always look for someone to learn from,” Dr. Gorman says. “They’re out there, no matter where you are or what you’re doing. Throw out some questions and see who you hit it off with, who gives you sound advice.” TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

You may have had a mentor as a resident and possibly in your first year as a hospitalist, but don’t count out these valuable resources as you continue in your career. And don’t count out mentors who may come from other walks of life.

“It’s natural for physicians to look toward other physicians for guidance,” says Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer for Cogent Healthcare, Nashville. “For physicians, including hospitalists, their natural inclination is to seek mentors who are physicians or have a similar training background. While there are many great physician mentors, you may be limiting yourself and missing opportunities that come from broader mentoring.”

Informal mentoring relationships are an excellent way to learn all sorts of leadership skills, from the subtle—like handling complains about a physician’s constant body odor—to hard skills, such as putting together a budget for your department or practice.

—Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer, Cogent Healthcare, Nashville

Management Mentors

Dr. Holman identified people at various stages in his career who could impart skills he sought, from a vice president of [human relations] for an integrated health system who steered him on personnel management and leadership development, to a carpenter-turned-attorney who helped him hone critical thinking skills.

“Talking to a mentor can show you the fresh side of new or old situations,” says Dr. Holman. “And you can feel comfortable telling them things that you wouldn’t tell anyone else. [When] you don’t work together, it provides a safe harbor to express ideas and opinions you normally wouldn’t.”

Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, chief executive officer of Advanced ICU Care in St. Louis, Mo., agrees. “If you want someone to bounce ideas off of, try to find someone outside your organization,” she advises. She recommends physician organizations such as SHM: “Find someone who will listen, can keep their mouth shut and give you some honest feedback. For that reason, I’m a fan of professional coaches and career counselors. They provide an objective and unbiased audience and can suggest straightforward ways to manage sensitive issues.”

You also can find valuable mentors inside your workplace. “An often overlooked resource for hospitalist leaders is the other managers in their facilities,” says Dr. Gorman. “When I was a new manager, one of my mentors was the director of nursing. We could toss ideas back and forth, and she knew the politics and the personalities of the place, knew what mattered and what didn’t, and could steer me in the right direction.”

The managers and directors you work with, regardless of whether they’re physicians, are likely to have a lot of management experience, and can be resources for on-the-spot advice and guidance.

“Depending on the situation, even a chief operating officer or CEO of your hospital can give you good ideas and help you,” adds Dr. Gorman. “You’re a hospitalist; they’re supposed to be on your side. And they may be just five or 10 years older than you, but they have a lot of people management experience under their belts.”

They’re Everywhere

If you look beyond physicians and other healthcare professionals, finding an informal mentor is simply a matter of keeping your eyes and your mind open.

“You find a mentor by being in different situations,” Dr. Holman says. “Take advantage of getting to know people in different spheres, see what makes them tick that you can learn and apply to yourself.”

Consider all aspects of your life outside the workplace—your neighborhood, your church, your children’s school, any organizations you volunteer for, or social venues. Even your family—does anyone have management or business experience?

Keep your options open for learning from others, but if you have a specific area where you want to gain knowledge, you can search your circle of acquaintances to see who might be able to fill in that gap.

“Outside of healthcare, my personal accountant was a huge help,” says Dr. Gorman. “He sat down with me and helped me understand the financials I was supposed to do. You may have to pay for this service, but if you’re just asking for a few hours of their time and you have a good relationship, they’ll help you out.”

Regardless of what you want to learn, keep in mind that mentors can come in any shape and form. “A mentor can be someone younger than you, someone less well educated,” Dr. Holman points out. “What matters is when you recognize the value of the perspectives they bring.”

In fact, Dr. Holman says, he deliberately looks for people who are a little different from himself. “We tend to gravitate to those who are like us, but [in mentoring] this doesn’t lend itself to the greatest growth long-term,” he explains.

Make Mentoring Work

When you target someone as a potential mentor, it’s best to start with occasional questions and keep the relationship casual.

“My experience—and this is supported by literature—is that mentoring relationships are most solid when they form naturally,” Dr. Holman says. “The mentorship arena lends itself to flexibility and informal structure.”

Dr. Gorman agrees, suggesting that you not even mention “the M word.” “In my experience, asking someone flat out if they’ll be your mentor doesn’t really work,” Dr. Gorman says. “It sounds like a big commitment, and they shy away from it. Instead, I’d say just keep going back to the same people for guidance. Find those people who will listen to you and give you some help.”

Once you establish a mentoring relationship, try to find a way to return the favor—at least by being a good mentee.

“It’s particularly rewarding when mentoring is not one-sided, when each person has something to bring to the table,” Dr. Holman says. “Though it may be mostly one-sided, it’s good to be able to give some advice or counsel in return.”

Dr. Gorman adds that a good mentee either will act on advice or address why they didn’t. “No one likes to give advice just to see you blow it off, or head straight into a situation they warned you against,” she stresses. “Be respectful of their time, and be prepared when you present a problem. And be sure to thank them. You don’t have to send flowers or anything, just a verbal thank you for their time.”

No matter what stage your career is in, you can always pick up new skills and perspectives—particularly if you’re in a leadership position. Even if you feel you’re well established, finding new mentors can only make you better at what you do.

“You should always look for someone to learn from,” Dr. Gorman says. “They’re out there, no matter where you are or what you’re doing. Throw out some questions and see who you hit it off with, who gives you sound advice.” TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Nurse Ratios Suffer

Several studies have linked lower nurse-to-patient ratios with fewer medical errors and deaths, better overall treatment, and reduced rates of nurse burnout. These findings led California, in 1999, to pass the country’s first law mandating a minimum nurse-to-patient staffing ratio.

By 2004, the mandated ratio was one licensed nurse for every six patients; that was decreased in 2005 to one nurse for every five patients. Since then, similar bills have been passed or proposed in at least 25 more states. The benefits to patients and nurses of these improved ratios are clear. However, their effect on hospitalists, other staff members, and hospitals have not been widely studied. Further, the mandates often do not come with additional money to implement them.

In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Patrick Conway, MD, and colleagues examine nurse staffing trends in California hospitals since the mandate went into effect. They were particularly interested in what they called “safety net” hospitals: urban, government-owned, resource-poor institutions with at least 36% of patients uninsured or on Medicaid.

Dr. Conway, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his coauthors hypothesized that cash-strapped hospitals would find it hard to meet the mandate and might shortchange other programs in an effort to comply. Laudable as such legislation might be, “we wanted to make it clear to hospitalists and hospitals that the ratios could have an impact on other goals they wanted to achieve, such as meeting pay-for-performance targets,” he says.

Using financial data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, they examined staffing trends on adult general medical surgical units in short-term, acute-care general hospitals from 1993 to 2004, the most recent years for which complete data was available. For 2003 and 2004, they also analyzed staff ratios according to five characteristics: hospital ownership (profit, nonprofit, government-owned), market competitiveness, teaching status, location (urban vs. rural), and whether or not the hospital met the definition of a safety net facility.

From 1993-99, nurse staffing ratios remained flat; they rose steadily thereafter. Not surprisingly, the largest increase occurred between 2003 and 2004, the year implementation was slated to go into effect. During that period, the median ratio for all hospitals studied went from less than one nurse per four patients to more than 1:4, exceeding the mandated figure. Fewer than 25% of hospitals fell short of the minimum mandate of 1:5.

However, further analysis reveals more nuances. The mandate requires a minimum ratio of licensed nurses to patients; those nurses can be registered nurses (RNs), licensed vocational nurses (LVNs), or a combination. In 2004, only 2.4% of hospitals fell below the mandated minimum for that year of 1:6, compared with 5% from the year before—but 11.4% were below 1:5 (RNs plus LVNs). When RNs only were considered, 29.5% of hospitals fell short of one for every five patients.

Further, some states are considering a minimum mandate of one licensed nurse per every four patients—yet 40.4% of the hospitals in this study did not meet that standard. “This demonstrates the substantial increase in the proportion of hospitals that are below minimum ratios as the number of nurses or required training level of nurses is increased,” the authors point out.

The finding that nearly 30% of hospitals had less than one registered nurse for every five patients was surprising, says Dr. Conway, whose wife is a registered nurse. In other words, “if you or I or our parents were admitted to a hospital, your chances are about one in three that they will have less than one nurse for every five patients. That means each nurse has less time to spend per patient.”

For-profit hospitals, non-teaching hospitals, and hospitals in urban or more competitive locations fared best at achieving the mandated ratios. However, hospitals with high Medicaid or uninsured populations were significantly more likely to fall below the minimum ratios than their more affluent counterparts and did not achieve the marked gains in staffing ratios achieved in other facilities.

All in all, more than 20% of safety net hospitals failed to achieve the 2004 mandate of 1:5, compared with about 12% of the other types of hospitals.

Of the safety net hospitals that did achieve the mandate, one wonders what types of tradeoffs they had to make, Dr. Conway adds: “Are they closing emergency rooms? Investing less in new equipment and facilities? Hiring less-trained staff? This study raises those questions, although it doesn’t answer them.”

More and more, hospitalists are being held responsible for quality improvement programs and outcomes measures within hospitals. The targets monitored often are those most strongly influenced by nurse presence, such as the number of central line infections, pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, ventilator-acquired pneumonia, and similar conditions.

On the other hand, “no one has yet studied what happens when a hospital goes from a ratio of 1:5 to 1:4,” Dr. Conway says. It is possible that the [patient] gains realized may not be large enough to justify the compromises a hospital might have to make in other areas to meet that goal. “We must determine what the tradeoffs are and identify optimal nurse staffing ratios. Adequate nurse staffing is a significant key to achieving a successful team management approach in a hospital.” TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Editor’s note: Dr. Conway was featured in the February 2008 issue (p. 28) as a member of the White House Fellows Program.

Several studies have linked lower nurse-to-patient ratios with fewer medical errors and deaths, better overall treatment, and reduced rates of nurse burnout. These findings led California, in 1999, to pass the country’s first law mandating a minimum nurse-to-patient staffing ratio.

By 2004, the mandated ratio was one licensed nurse for every six patients; that was decreased in 2005 to one nurse for every five patients. Since then, similar bills have been passed or proposed in at least 25 more states. The benefits to patients and nurses of these improved ratios are clear. However, their effect on hospitalists, other staff members, and hospitals have not been widely studied. Further, the mandates often do not come with additional money to implement them.

In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Patrick Conway, MD, and colleagues examine nurse staffing trends in California hospitals since the mandate went into effect. They were particularly interested in what they called “safety net” hospitals: urban, government-owned, resource-poor institutions with at least 36% of patients uninsured or on Medicaid.

Dr. Conway, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his coauthors hypothesized that cash-strapped hospitals would find it hard to meet the mandate and might shortchange other programs in an effort to comply. Laudable as such legislation might be, “we wanted to make it clear to hospitalists and hospitals that the ratios could have an impact on other goals they wanted to achieve, such as meeting pay-for-performance targets,” he says.

Using financial data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, they examined staffing trends on adult general medical surgical units in short-term, acute-care general hospitals from 1993 to 2004, the most recent years for which complete data was available. For 2003 and 2004, they also analyzed staff ratios according to five characteristics: hospital ownership (profit, nonprofit, government-owned), market competitiveness, teaching status, location (urban vs. rural), and whether or not the hospital met the definition of a safety net facility.

From 1993-99, nurse staffing ratios remained flat; they rose steadily thereafter. Not surprisingly, the largest increase occurred between 2003 and 2004, the year implementation was slated to go into effect. During that period, the median ratio for all hospitals studied went from less than one nurse per four patients to more than 1:4, exceeding the mandated figure. Fewer than 25% of hospitals fell short of the minimum mandate of 1:5.

However, further analysis reveals more nuances. The mandate requires a minimum ratio of licensed nurses to patients; those nurses can be registered nurses (RNs), licensed vocational nurses (LVNs), or a combination. In 2004, only 2.4% of hospitals fell below the mandated minimum for that year of 1:6, compared with 5% from the year before—but 11.4% were below 1:5 (RNs plus LVNs). When RNs only were considered, 29.5% of hospitals fell short of one for every five patients.

Further, some states are considering a minimum mandate of one licensed nurse per every four patients—yet 40.4% of the hospitals in this study did not meet that standard. “This demonstrates the substantial increase in the proportion of hospitals that are below minimum ratios as the number of nurses or required training level of nurses is increased,” the authors point out.

The finding that nearly 30% of hospitals had less than one registered nurse for every five patients was surprising, says Dr. Conway, whose wife is a registered nurse. In other words, “if you or I or our parents were admitted to a hospital, your chances are about one in three that they will have less than one nurse for every five patients. That means each nurse has less time to spend per patient.”

For-profit hospitals, non-teaching hospitals, and hospitals in urban or more competitive locations fared best at achieving the mandated ratios. However, hospitals with high Medicaid or uninsured populations were significantly more likely to fall below the minimum ratios than their more affluent counterparts and did not achieve the marked gains in staffing ratios achieved in other facilities.

All in all, more than 20% of safety net hospitals failed to achieve the 2004 mandate of 1:5, compared with about 12% of the other types of hospitals.

Of the safety net hospitals that did achieve the mandate, one wonders what types of tradeoffs they had to make, Dr. Conway adds: “Are they closing emergency rooms? Investing less in new equipment and facilities? Hiring less-trained staff? This study raises those questions, although it doesn’t answer them.”

More and more, hospitalists are being held responsible for quality improvement programs and outcomes measures within hospitals. The targets monitored often are those most strongly influenced by nurse presence, such as the number of central line infections, pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, ventilator-acquired pneumonia, and similar conditions.

On the other hand, “no one has yet studied what happens when a hospital goes from a ratio of 1:5 to 1:4,” Dr. Conway says. It is possible that the [patient] gains realized may not be large enough to justify the compromises a hospital might have to make in other areas to meet that goal. “We must determine what the tradeoffs are and identify optimal nurse staffing ratios. Adequate nurse staffing is a significant key to achieving a successful team management approach in a hospital.” TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Editor’s note: Dr. Conway was featured in the February 2008 issue (p. 28) as a member of the White House Fellows Program.

Several studies have linked lower nurse-to-patient ratios with fewer medical errors and deaths, better overall treatment, and reduced rates of nurse burnout. These findings led California, in 1999, to pass the country’s first law mandating a minimum nurse-to-patient staffing ratio.

By 2004, the mandated ratio was one licensed nurse for every six patients; that was decreased in 2005 to one nurse for every five patients. Since then, similar bills have been passed or proposed in at least 25 more states. The benefits to patients and nurses of these improved ratios are clear. However, their effect on hospitalists, other staff members, and hospitals have not been widely studied. Further, the mandates often do not come with additional money to implement them.

In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Patrick Conway, MD, and colleagues examine nurse staffing trends in California hospitals since the mandate went into effect. They were particularly interested in what they called “safety net” hospitals: urban, government-owned, resource-poor institutions with at least 36% of patients uninsured or on Medicaid.

Dr. Conway, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his coauthors hypothesized that cash-strapped hospitals would find it hard to meet the mandate and might shortchange other programs in an effort to comply. Laudable as such legislation might be, “we wanted to make it clear to hospitalists and hospitals that the ratios could have an impact on other goals they wanted to achieve, such as meeting pay-for-performance targets,” he says.

Using financial data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, they examined staffing trends on adult general medical surgical units in short-term, acute-care general hospitals from 1993 to 2004, the most recent years for which complete data was available. For 2003 and 2004, they also analyzed staff ratios according to five characteristics: hospital ownership (profit, nonprofit, government-owned), market competitiveness, teaching status, location (urban vs. rural), and whether or not the hospital met the definition of a safety net facility.

From 1993-99, nurse staffing ratios remained flat; they rose steadily thereafter. Not surprisingly, the largest increase occurred between 2003 and 2004, the year implementation was slated to go into effect. During that period, the median ratio for all hospitals studied went from less than one nurse per four patients to more than 1:4, exceeding the mandated figure. Fewer than 25% of hospitals fell short of the minimum mandate of 1:5.

However, further analysis reveals more nuances. The mandate requires a minimum ratio of licensed nurses to patients; those nurses can be registered nurses (RNs), licensed vocational nurses (LVNs), or a combination. In 2004, only 2.4% of hospitals fell below the mandated minimum for that year of 1:6, compared with 5% from the year before—but 11.4% were below 1:5 (RNs plus LVNs). When RNs only were considered, 29.5% of hospitals fell short of one for every five patients.

Further, some states are considering a minimum mandate of one licensed nurse per every four patients—yet 40.4% of the hospitals in this study did not meet that standard. “This demonstrates the substantial increase in the proportion of hospitals that are below minimum ratios as the number of nurses or required training level of nurses is increased,” the authors point out.

The finding that nearly 30% of hospitals had less than one registered nurse for every five patients was surprising, says Dr. Conway, whose wife is a registered nurse. In other words, “if you or I or our parents were admitted to a hospital, your chances are about one in three that they will have less than one nurse for every five patients. That means each nurse has less time to spend per patient.”

For-profit hospitals, non-teaching hospitals, and hospitals in urban or more competitive locations fared best at achieving the mandated ratios. However, hospitals with high Medicaid or uninsured populations were significantly more likely to fall below the minimum ratios than their more affluent counterparts and did not achieve the marked gains in staffing ratios achieved in other facilities.

All in all, more than 20% of safety net hospitals failed to achieve the 2004 mandate of 1:5, compared with about 12% of the other types of hospitals.

Of the safety net hospitals that did achieve the mandate, one wonders what types of tradeoffs they had to make, Dr. Conway adds: “Are they closing emergency rooms? Investing less in new equipment and facilities? Hiring less-trained staff? This study raises those questions, although it doesn’t answer them.”

More and more, hospitalists are being held responsible for quality improvement programs and outcomes measures within hospitals. The targets monitored often are those most strongly influenced by nurse presence, such as the number of central line infections, pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, ventilator-acquired pneumonia, and similar conditions.

On the other hand, “no one has yet studied what happens when a hospital goes from a ratio of 1:5 to 1:4,” Dr. Conway says. It is possible that the [patient] gains realized may not be large enough to justify the compromises a hospital might have to make in other areas to meet that goal. “We must determine what the tradeoffs are and identify optimal nurse staffing ratios. Adequate nurse staffing is a significant key to achieving a successful team management approach in a hospital.” TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Editor’s note: Dr. Conway was featured in the February 2008 issue (p. 28) as a member of the White House Fellows Program.

Protect the Platelets

The frequency of drug-induced thrombocytopenia (DIT) in acutely ill patients is thought to be up to 25%, making it a common problem.1,2

Hundreds of drugs have been identified as causing DIT, due to either accelerated immune-mediated platelet destruction, decreased platelet production (bone marrow suppression), or platelet aggregation. The latter is the case in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (HITT). DIT should be suspected in any patient who presents with acute thrombocytopenia from an unknown cause.3

Normal adult platelet counts usually are in the range of 140,000 to 450,000/mm3. A patient who presents with severe thrombocytopenia (less than 20,000 platelets/mm3) should strongly be suspected as having a drug-induced cause.

A patient also can present with moderate to severe thrombocytopenia (less than 50,000 platelets/mm3) and spontaneous bleeding from a drug-induced cause. The spontaneous bleeding can take the form of simple petechiae or ecchymoses, as well as mucosal bleeding or life-threatening intracranial or gastrointestinal hemorrhage. It may also present itself as bleeding around catheter insertion sites.

When DIT occurs, platelet count usually falls within two to three days of taking a drug that’s been taken before, or seven or more days after starting a drug the patient has not been exposed to. Once the offending drug is discontinued, platelet counts usually recover within 10 days.

Exclusions of other causes of thrombocytopenia, such as inflammatory processes and congenital disorders, as well as nondrug causes including sepsis, malignancy, extensive burns, chronic alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus, splenomegaly, and disseminated intravascular coagulation, become part of the differential diagnosis.

Generally, the frequency and severity of bleeding manifestations correlate with the actual platelet count. Patients with a platelet count of less than 50,000/mm3 have an increased risk of spontaneous hemorrhage, but the severity may vary. Other risk factors include advanced age, bleeding history, and general bleeding diatheses.

A thorough physical examination and drug history are essential. Agents commonly associated with thrombocytopenia should be identified first followed by a more extensive review for other causes. A careful drug history should include prescriptions, over-the-counter medications (specifically quinine and acetaminophen), dietary supplements, folk remedies, other complementary and alternative therapies, and vaccinations.

The Agents

The top two suspects for DIT are antineoplastic agents and heparin. After these two, the agents most frequently associated with DIT development include:

- Quinine/quinidine;

- Phenytoin;

- Sulfonamide antibiotics;

- Cimetidine;

- Ranitidine;