User login

Calcinosis universalis

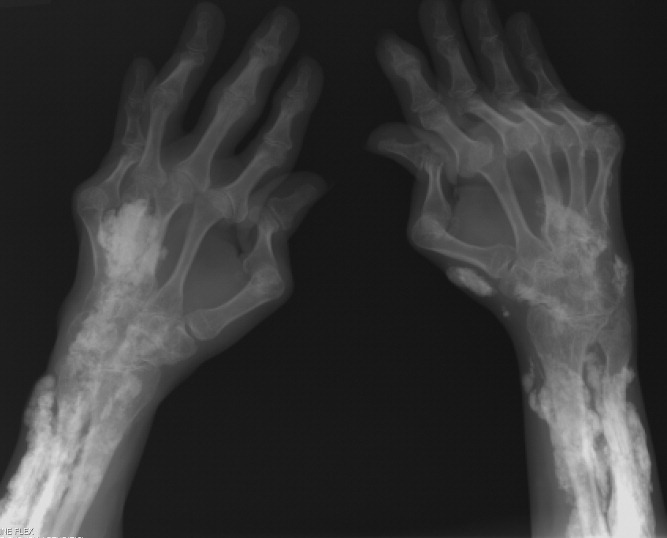

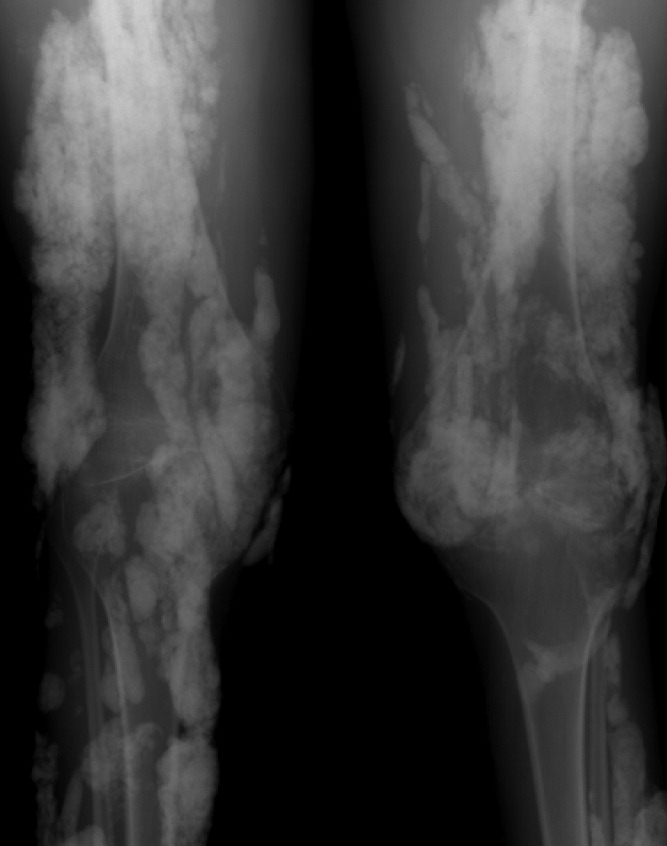

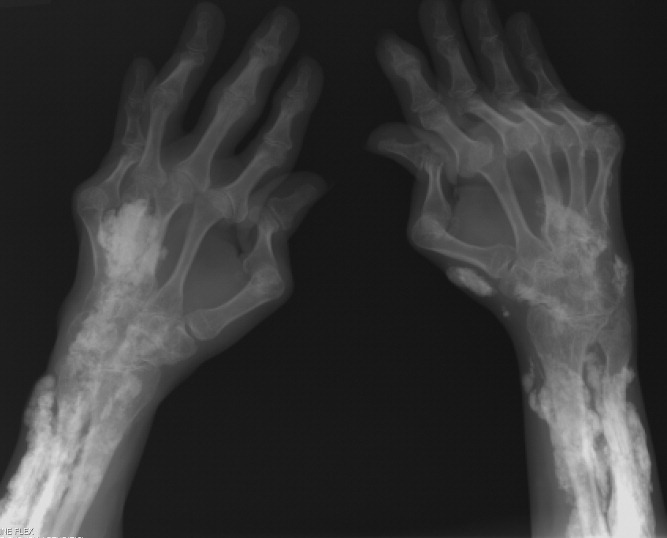

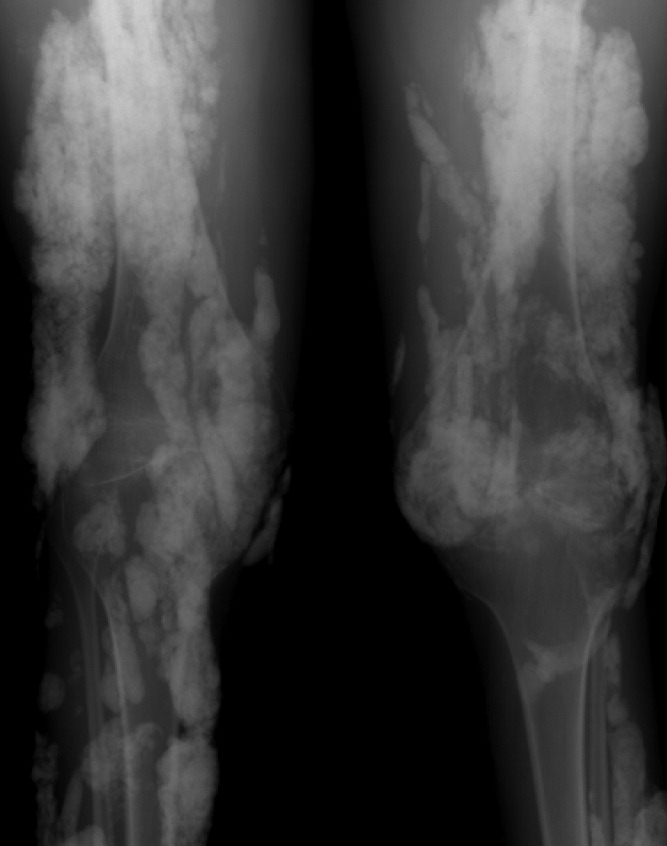

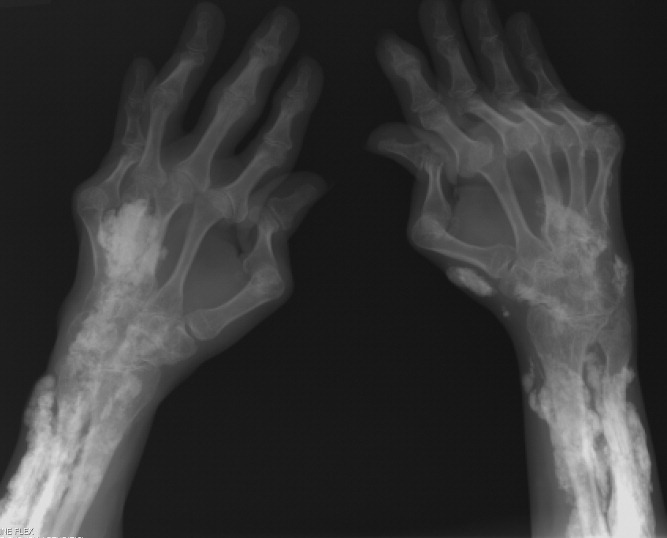

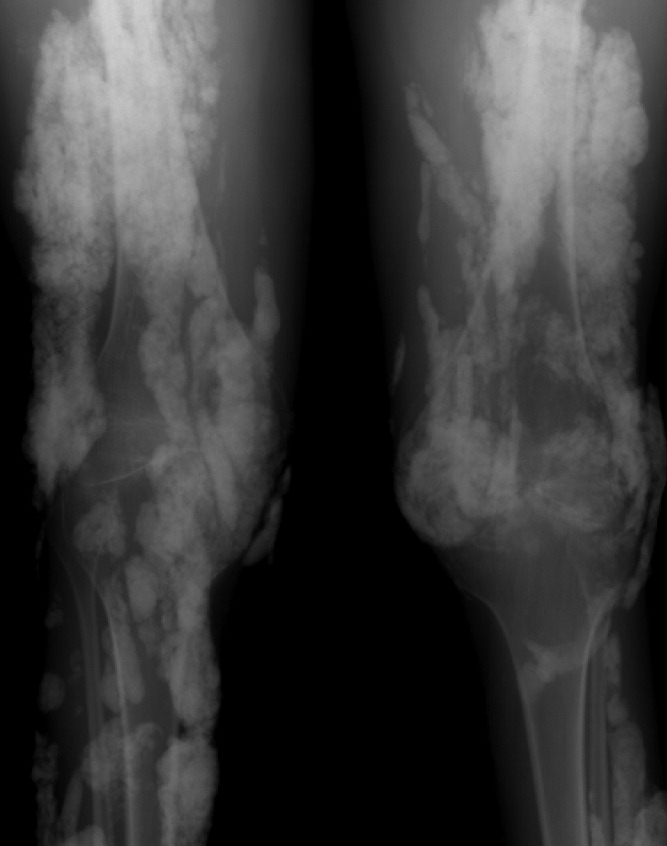

A 38‐year‐old woman with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and calcinosis universalis presented with 3 days of drainage from a lesion on her right elbow. An examination of the elbow revealed diffuse and firm subcutaneous nodules with overlying erythema. X‐rays illustrated soft‐tissue calcifications in the forearm and elbow without evidence of osteomyelitis (Figure 1). Wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was started on intravenous antibiotics for abscess treatment.

Calcinosis universalis is soft‐tissue calcification presenting as a complication of JDM. It is often detected in childhood in 30% to 70% of patients. It is hypothesized that calcinosis is due to chronic tissue inflammation, as seen in JDM, leading to muscle damage, releasing calcium, and inducing mineralization. Calcinosis universalis often presents as calcified nodules and plaques in areas of repeated trauma, such as joints, extremities, and buttocks (Figures 13). Calcification is localized in subcutaneous tissue, fascial planes, tendons, or intramuscular areas. It can cause debilitating secondary complications such as skin ulcerations expressing calcified material, superimposed infections of skin lesions, joint contractures with severe arthralgias, and muscle atrophy. Calcinosis has been correlated with severity of JDM with presence of cardiac involvement and use of more than one immunosuppression medication.1 It has also been associated with the degree of vasculopathy and delay in initiation of therapy for controlling inflammation in JDM.2

Soft‐tissue calcification can be classified into 5 categories:

-

Dystrophic calcification occurs in injured tissues with normal calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, as seen in this patient. Calcified nodules or plaques occur in the extremities and buttocks. This is most often seen in JDM, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

-

Metastatic calcification affects normal tissues with abnormal levels of calcium and phosphorus. It is seen in large joints as well as arteries and visceral organs. It is associated with hyperparathyroidism, hypervitaminosis D, and malignancies.

-

Calciphylaxis with abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism causes small‐vessel calcification in patients with chronic renal failure.

-

Tumoral calcification is a familial condition with normal calcium levels but elevated phosphorus levels. Large subcutaneous calcifications are seen near high‐pressure areas and joints.

-

Idiopathic calcification is seen in healthy children and young adults with normal calcium metabolism and appears as multiple subcutaneous calcifications.2

Although multiple therapeutic options have been tried for the management or prevention of calcinosis, there is currently no accepted standard of treatment. In patients with calcinosis, warfarin, probenecid, colchicine, bisphosphonates, minocycline, diltiazem, aluminum hydroxide, corticosteroids, and salicylate have been attempted with variable results. Other therapeutic options include carbon dioxide laser treatments and surgical excision of large plaques. Decreasing muscle inflammation with aggressive treatment of JDM may improve outcomes and decrease the incidence of calcification.3 Unfortunately, once calcinosis has occurred, it is highly refractory to medical therapy.

Calcinosis universalis can lead to severe functional impairment. It can be distinguished from other types of calcinosis by diffuse involvement of muscle and fascia in connective tissue disease with normal calcium and phosphorus levels. New management modalities such as cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are currently being evaluated.

- ,,, et al.Risk factors associated with calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis.JPediatr (Rio J).2008;84(1):68–74.

- ,,,.Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2005;34(6):805–812.

- ,,, et al.Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis results in improved outcome and decreased incidence of calcinosis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2002;47(4):505–511.

A 38‐year‐old woman with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and calcinosis universalis presented with 3 days of drainage from a lesion on her right elbow. An examination of the elbow revealed diffuse and firm subcutaneous nodules with overlying erythema. X‐rays illustrated soft‐tissue calcifications in the forearm and elbow without evidence of osteomyelitis (Figure 1). Wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was started on intravenous antibiotics for abscess treatment.

Calcinosis universalis is soft‐tissue calcification presenting as a complication of JDM. It is often detected in childhood in 30% to 70% of patients. It is hypothesized that calcinosis is due to chronic tissue inflammation, as seen in JDM, leading to muscle damage, releasing calcium, and inducing mineralization. Calcinosis universalis often presents as calcified nodules and plaques in areas of repeated trauma, such as joints, extremities, and buttocks (Figures 13). Calcification is localized in subcutaneous tissue, fascial planes, tendons, or intramuscular areas. It can cause debilitating secondary complications such as skin ulcerations expressing calcified material, superimposed infections of skin lesions, joint contractures with severe arthralgias, and muscle atrophy. Calcinosis has been correlated with severity of JDM with presence of cardiac involvement and use of more than one immunosuppression medication.1 It has also been associated with the degree of vasculopathy and delay in initiation of therapy for controlling inflammation in JDM.2

Soft‐tissue calcification can be classified into 5 categories:

-

Dystrophic calcification occurs in injured tissues with normal calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, as seen in this patient. Calcified nodules or plaques occur in the extremities and buttocks. This is most often seen in JDM, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

-

Metastatic calcification affects normal tissues with abnormal levels of calcium and phosphorus. It is seen in large joints as well as arteries and visceral organs. It is associated with hyperparathyroidism, hypervitaminosis D, and malignancies.

-

Calciphylaxis with abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism causes small‐vessel calcification in patients with chronic renal failure.

-

Tumoral calcification is a familial condition with normal calcium levels but elevated phosphorus levels. Large subcutaneous calcifications are seen near high‐pressure areas and joints.

-

Idiopathic calcification is seen in healthy children and young adults with normal calcium metabolism and appears as multiple subcutaneous calcifications.2

Although multiple therapeutic options have been tried for the management or prevention of calcinosis, there is currently no accepted standard of treatment. In patients with calcinosis, warfarin, probenecid, colchicine, bisphosphonates, minocycline, diltiazem, aluminum hydroxide, corticosteroids, and salicylate have been attempted with variable results. Other therapeutic options include carbon dioxide laser treatments and surgical excision of large plaques. Decreasing muscle inflammation with aggressive treatment of JDM may improve outcomes and decrease the incidence of calcification.3 Unfortunately, once calcinosis has occurred, it is highly refractory to medical therapy.

Calcinosis universalis can lead to severe functional impairment. It can be distinguished from other types of calcinosis by diffuse involvement of muscle and fascia in connective tissue disease with normal calcium and phosphorus levels. New management modalities such as cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are currently being evaluated.

A 38‐year‐old woman with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and calcinosis universalis presented with 3 days of drainage from a lesion on her right elbow. An examination of the elbow revealed diffuse and firm subcutaneous nodules with overlying erythema. X‐rays illustrated soft‐tissue calcifications in the forearm and elbow without evidence of osteomyelitis (Figure 1). Wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was started on intravenous antibiotics for abscess treatment.

Calcinosis universalis is soft‐tissue calcification presenting as a complication of JDM. It is often detected in childhood in 30% to 70% of patients. It is hypothesized that calcinosis is due to chronic tissue inflammation, as seen in JDM, leading to muscle damage, releasing calcium, and inducing mineralization. Calcinosis universalis often presents as calcified nodules and plaques in areas of repeated trauma, such as joints, extremities, and buttocks (Figures 13). Calcification is localized in subcutaneous tissue, fascial planes, tendons, or intramuscular areas. It can cause debilitating secondary complications such as skin ulcerations expressing calcified material, superimposed infections of skin lesions, joint contractures with severe arthralgias, and muscle atrophy. Calcinosis has been correlated with severity of JDM with presence of cardiac involvement and use of more than one immunosuppression medication.1 It has also been associated with the degree of vasculopathy and delay in initiation of therapy for controlling inflammation in JDM.2

Soft‐tissue calcification can be classified into 5 categories:

-

Dystrophic calcification occurs in injured tissues with normal calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, as seen in this patient. Calcified nodules or plaques occur in the extremities and buttocks. This is most often seen in JDM, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

-

Metastatic calcification affects normal tissues with abnormal levels of calcium and phosphorus. It is seen in large joints as well as arteries and visceral organs. It is associated with hyperparathyroidism, hypervitaminosis D, and malignancies.

-

Calciphylaxis with abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism causes small‐vessel calcification in patients with chronic renal failure.

-

Tumoral calcification is a familial condition with normal calcium levels but elevated phosphorus levels. Large subcutaneous calcifications are seen near high‐pressure areas and joints.

-

Idiopathic calcification is seen in healthy children and young adults with normal calcium metabolism and appears as multiple subcutaneous calcifications.2

Although multiple therapeutic options have been tried for the management or prevention of calcinosis, there is currently no accepted standard of treatment. In patients with calcinosis, warfarin, probenecid, colchicine, bisphosphonates, minocycline, diltiazem, aluminum hydroxide, corticosteroids, and salicylate have been attempted with variable results. Other therapeutic options include carbon dioxide laser treatments and surgical excision of large plaques. Decreasing muscle inflammation with aggressive treatment of JDM may improve outcomes and decrease the incidence of calcification.3 Unfortunately, once calcinosis has occurred, it is highly refractory to medical therapy.

Calcinosis universalis can lead to severe functional impairment. It can be distinguished from other types of calcinosis by diffuse involvement of muscle and fascia in connective tissue disease with normal calcium and phosphorus levels. New management modalities such as cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are currently being evaluated.

- ,,, et al.Risk factors associated with calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis.JPediatr (Rio J).2008;84(1):68–74.

- ,,,.Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2005;34(6):805–812.

- ,,, et al.Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis results in improved outcome and decreased incidence of calcinosis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2002;47(4):505–511.

- ,,, et al.Risk factors associated with calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis.JPediatr (Rio J).2008;84(1):68–74.

- ,,,.Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2005;34(6):805–812.

- ,,, et al.Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis results in improved outcome and decreased incidence of calcinosis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2002;47(4):505–511.

Evaluation of glycemic control following discontinuation of an intensive insulin protocol

Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance are common occurrences in critically ill patients, even those without a past medical history of diabetes.1, 2 This hyperglycemic state is associated with adverse outcomes, including severe infections, polyneuropathy, multiple‐organ failure, and death.3 Several studies have shown benefit in keeping patients' blood glucose (BG) tightly controlled.37 In a randomized controlled study, strict BG control (80‐110 mg/dL) with an insulin drip significantly reduced morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients.3 A recent meta‐analysis concluded that avoiding BG levels >150 mg/dL appeared to be crucial to reducing mortality in a mixed medical and surgical intensive care unit (ICU) population.7

The Diabetes Mellitus Insulin‐Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction study addressed the issue of tight glycemic control both acutely and chronically in 620 diabetic patients postmyocardial infarction. Patients were randomized to tight glycemic control (126‐180 mg/dL) followed by a transition to maintenance insulin or to standard care. This intervention demonstrated a sustained mortality reduction of 7.5% at 1 year.8 In contrast, the CREATE‐ECLA study showed a neutral mortality benefit of a short‐term (24‐hour) insulin infusion in postmyocardial infarction patients.9 These data demonstrate the need for clinicians to consider insulin requirements throughout the hospital stay and after discharge. To date, there are no published studies evaluating glycemic control following discontinuation of an intensive insulin protocol (IIP). Therefore, the current study was conducted to compare BG control during the use of an IIP and for the 5 days following intensive insulin therapy.

METHODS

Patient Population

This retrospective chart review was conducted at Methodist University Hospital (MUH), Memphis, TN. MUH is a 500‐bed, university‐affiliated tertiary referral hospital. The study was approved by the hospital institutional review board. From January 2006 to January 2007, a computer‐generated pharmacy report was used to identify all patients receiving the hospital‐approved IIP. Patients were included if they were 18 years old and received the IIP for 24 hours. Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (1) complete BG measurements were not retrievable while the patient received the IIP or for the 5 days following discontinuation of the IIP, (2) the patient died while receiving the IIP, and (3) an endocrinologist was involved in the care of the patient.

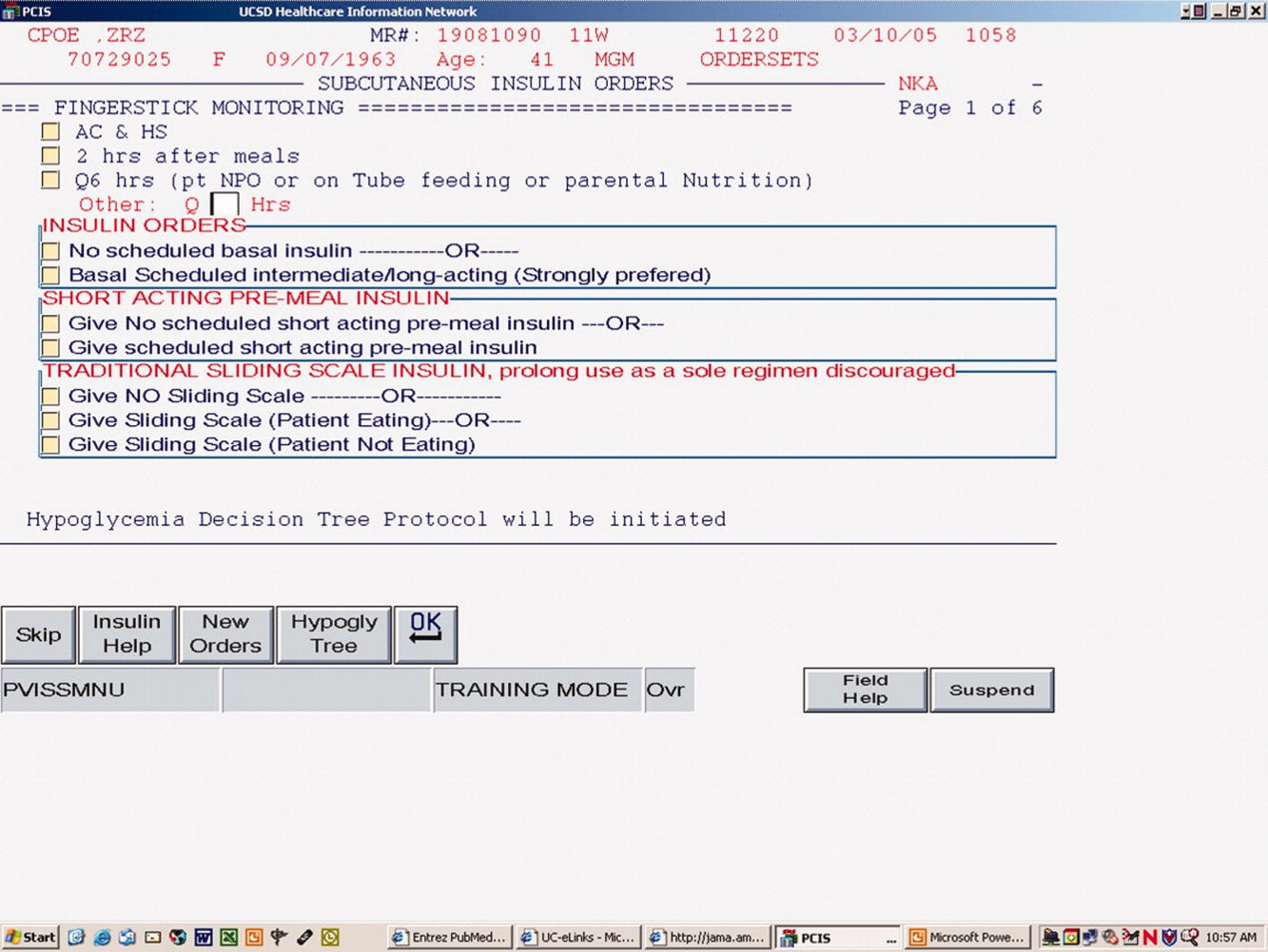

IIP

The hospital‐approved IIP is a paper‐based, physician‐initiated, nurse‐managed protocol. Criteria required before initiating the IIP include (1) ICU admission, (2) 2 BG measurements >150 mg/dL, (3) administration of continuous exogenous glucose, and (4) absence of diabetic ketoacidosis. The goal range of the IIP is 80 to 150 mg/dL. Hourly BG measurements are initially required, but as control is achieved, measurements may be extended to every 2 hours and then every 4 hours. In general, the criteria used for transitioning off the IIP include stability during the last 12 hours. Patients were considered to be stable on the IIP if they had >70% of their glucose measurements within the goal range during the last 12 hours.

Data Collection

When inclusion criteria were met, patients' medical records were reviewed. Data collection included basic demographic information, concurrent medications, duration of IIP, amount of insulin administered during the last 12 hours of the IIP, insulin regimen post‐IIP, and BG measurements during the last 12 hours on the IIP and for a total of 5 days after the IIP was stopped (follow‐up period). For this study, hyperglycemia was defined as a BG value >150 mg/dL, significant hyperglycemia was defined as >200 mg/dL, and severe hyperglycemia was defined as >300 mg/dL. Hypoglycemia was defined as a BG value <60 mg/dL. The values of <60 mg/dL, >150 mg/dL, and >200 mg/dL were chosen on the basis of the criteria used in the MUH IIP and standard sliding‐scale protocols. A value of >300 mg/dL was used to better describe patients with hyperglycemia. Poor glycemic control following the IIP was defined as a >30% change in mean BG during the last 12 hours on the drip and on the first day after discontinuation of the drip.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of this study was to compare BG control during the last 12 hours of an IIP and for the 5 days following its discontinuation. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the incidence of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia during the transition period and to identify patients at risk of poor glycemic control following discontinuation of the IIP. Continuous data are appropriately reported as the mean standard deviation or median (interquartile range), depending on the distribution. Continuous variables were compared with the Student t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test. Discrete variables were compared with chi‐square analysis and Bonferroni Correction where appropriate. For comparisons of BG during the IIP and on days 1 to 5 of the follow‐up period, repeated‐measures analysis of variance on ranks was conducted because of the distribution. These statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat version 2.03 (Systat Software, Inc., Richmond, VA). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. However, when the Bonferroni correction was used, a value of less than 0.01 was considered significant. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine independent predictors of a greater than 30% change in the mean BG value between the last 12 hours of the IIP and the first day off the insulin drip. Potential independent variables included in the analysis were stability on protocol, requiring less than 20 units of insulin in the last 12 hours on the IIP, use of antibiotics, use of steroids, history of diabetes, and type of insulin to which the patient was transitioned (none, sliding scale, and scheduled and sliding scale). The model was built in a backwards, stepwise fashion with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 171 patients received the IIP during the study period. Ninety‐seven patients did not meet inclusion criteria because they received the IIP for less than 24 hours. Of the 74 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 9 were excluded (5 had insufficient glucose data, 3 were cared for by an endocrinologist, and 1 died while receiving the IIP). Thus, 65 patients were included in the study.

Table 1 lists the baseline demographics for all patients and those with and without a history of diabetes mellitus (DM). The majority of the patients (n = 49) underwent a surgical procedure, with the most common procedure being coronary artery bypass graft (n = 38). Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft had the IIP included in their standard postoperative order set. The majority of patients were considered stable during the 12 hours prior to discontinuation of the IIP, including 23 patients with a history of DM. Of the 65 patients who were included in the study, 25 (38.5%) received a scheduled insulin order following discontinuation of the IIP, whereas 38 (58.5%) received some form of sliding‐scale insulin (SSI). Additionally, 2 (3%) patients did not receive any form of insulin order after stopping the IIP. Of those receiving scheduled insulin, 15 (60%) received neutral protamine Hagedorn, 5 (20%) received glargine, 5 (20%) received 70/30, and 1 (4%) received regular insulin. Of those receiving SSI only, the prescribed frequency was as follows: every 4 hours for 17 (45%), before meals and at bedtime for 15 (39%), every 6 hours for 5 (13%), and every 2 hours for 1 (3%).

| All Patients (n = 65) | PMH of DM (n = 36) | No PMH of DM (n = 29) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, mean years SD | 62 11 | 61 10 | 64 12 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 38 (58) | 22 (61) | 16 (55.2) |

| BMI SD | 30 7.2 | 31 7 | 30 6.5 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 49 (74.2) | 27 (75) | 21 (72.4) |

| CABG, n | 38 | 22 | 16 |

| Liver transplant, n | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| Other, n | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Last 24 hours on IIP, n (%) | |||

| Ventilator | 37 (56.9) | 22 (61.1) | 15 (51.7) |

| Antibiotics | 37 (56.9) | 20 (55.6) | 17 (58.6) |

| Vasopressors | 11 (16.9) | 5 (13.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| Hemodialysis | 8 (12.3) | 5 (13.9) | 3 (10.3) |

| Steroids | 16 (24.6) | 9 (25) | 7 (24.1) |

| Duration of IIP, mean hours SD | 72 65 | 80 78 | 62 45 |

| Insulin during last 12 hours of IIP, mean units SD | 47 37 | 51 30 | 46 45 |

| Type of insulin received following IIP, n (%) | |||

| Scheduled + sliding scale | 25 (38.5) | 19 (52.8) | 6 (20.7) |

| Sliding scale only | 38 (58.5) | 16 (44.4) | 22 (75.9) |

| None | 2 (3) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.4) |

| Total daily insulin following IIP, mean units SD | 28 41 | 38 49 | 17 24 |

| Patients stable on IIP | 44 (67.7) | 23 (64.8) | 21 (72.4) |

| Hospital LOS, mean days SD | 24 18 | 24 17 | 23 19 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 15 (23.1) | 5 (13.8) | 10 (34.5) |

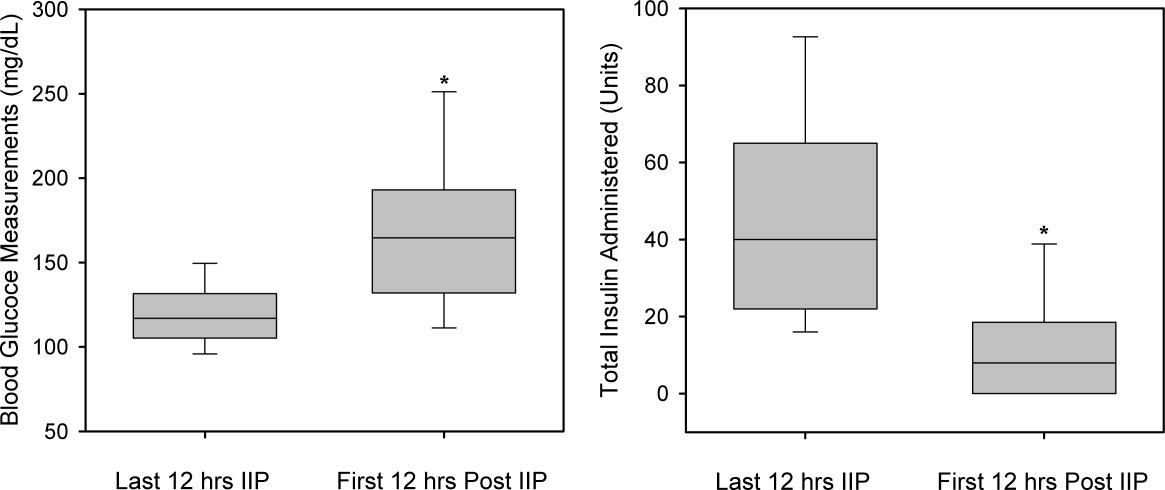

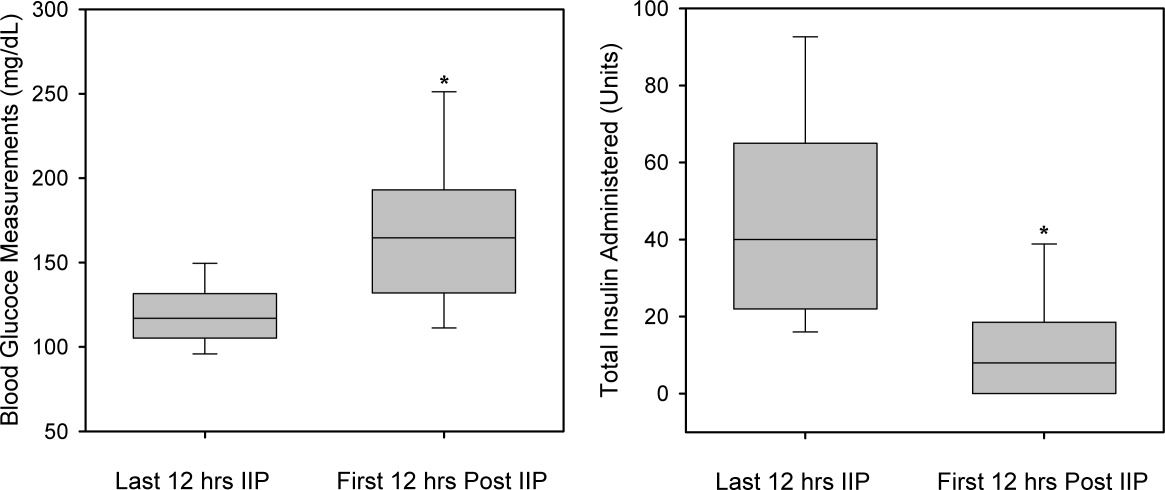

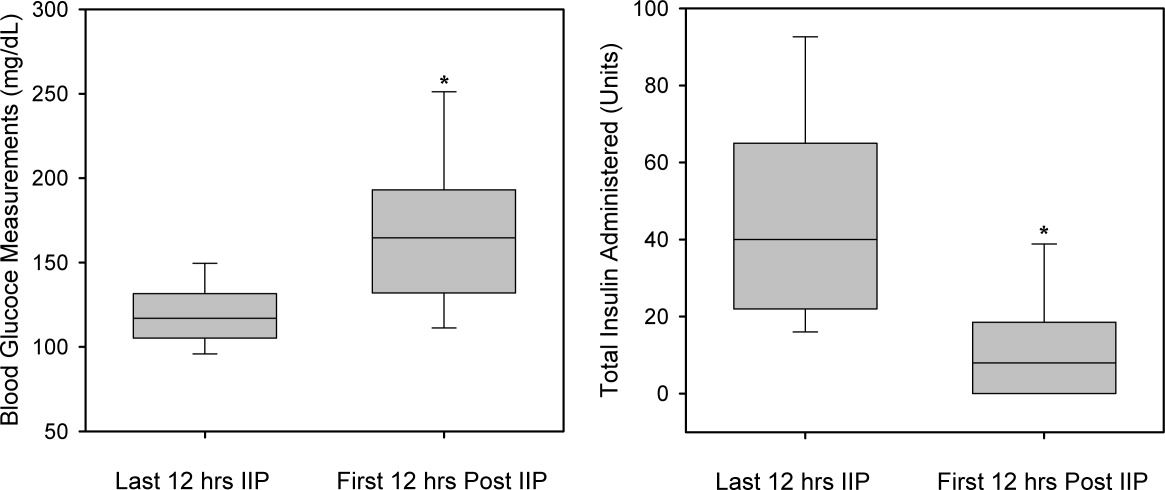

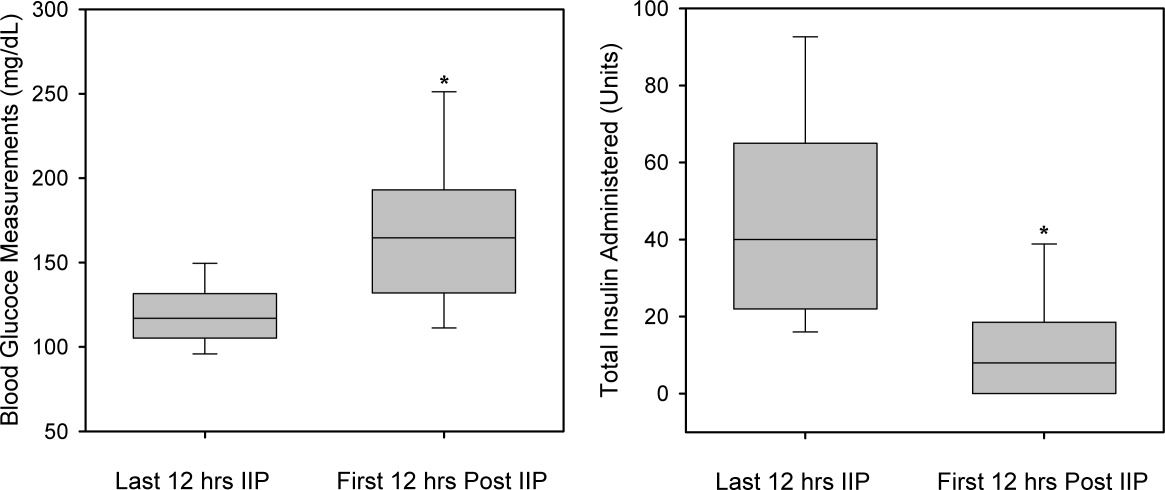

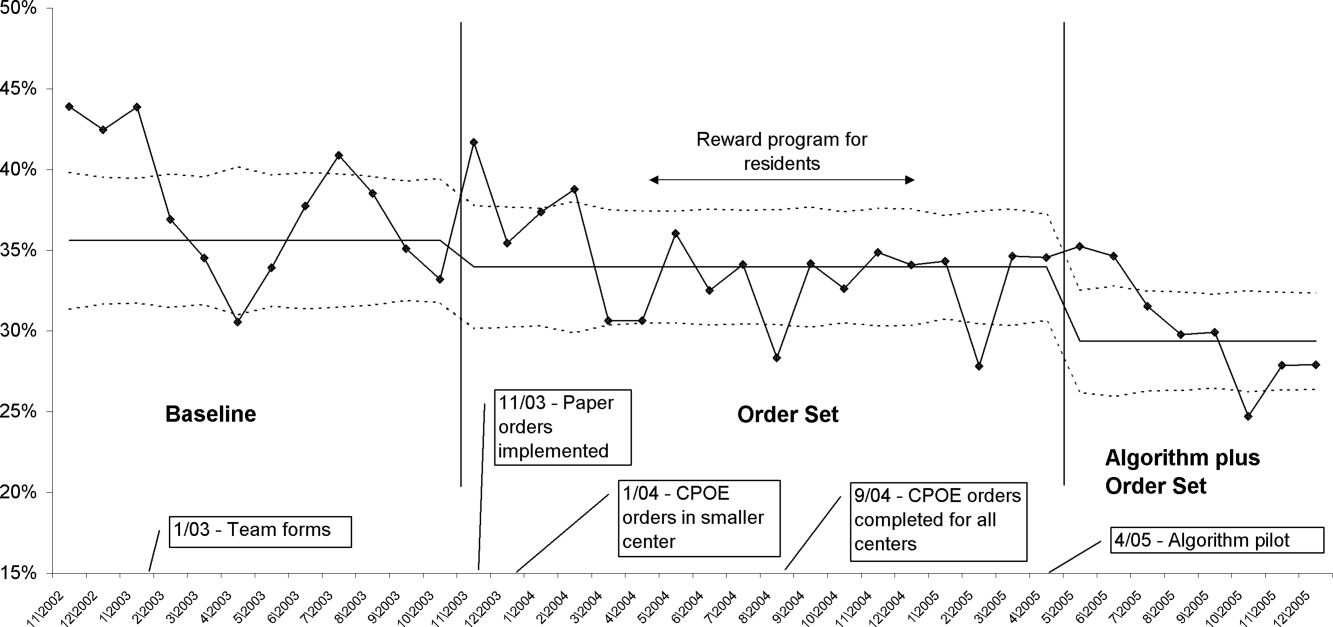

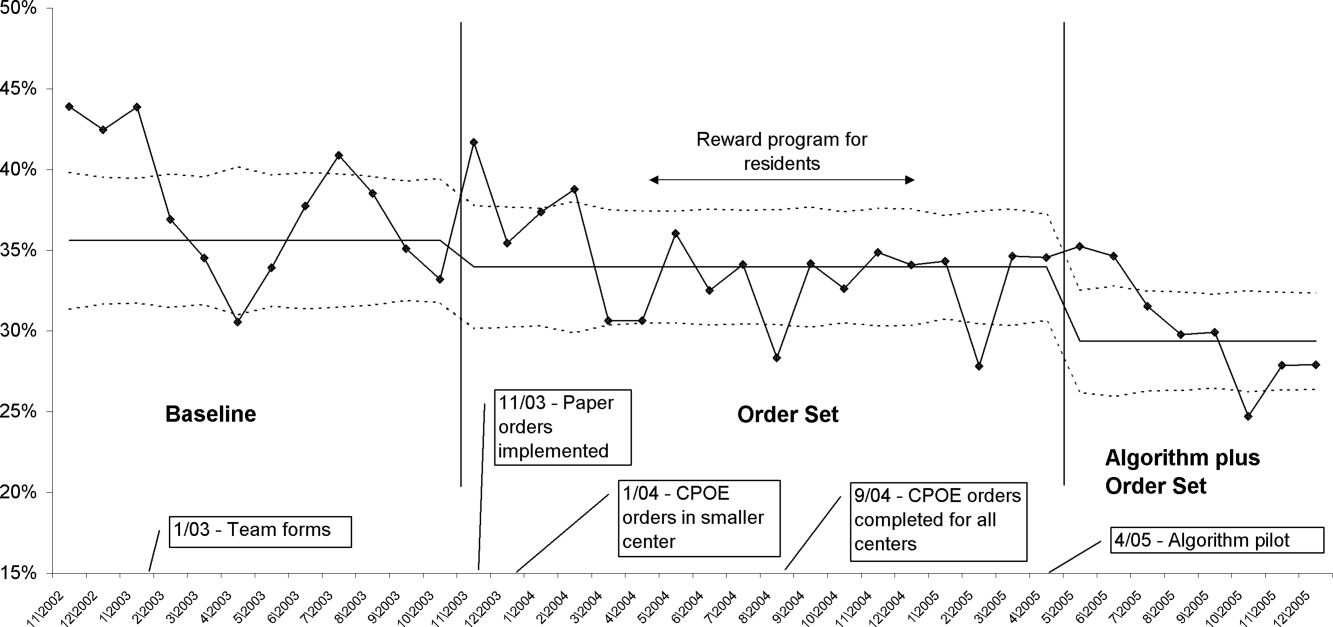

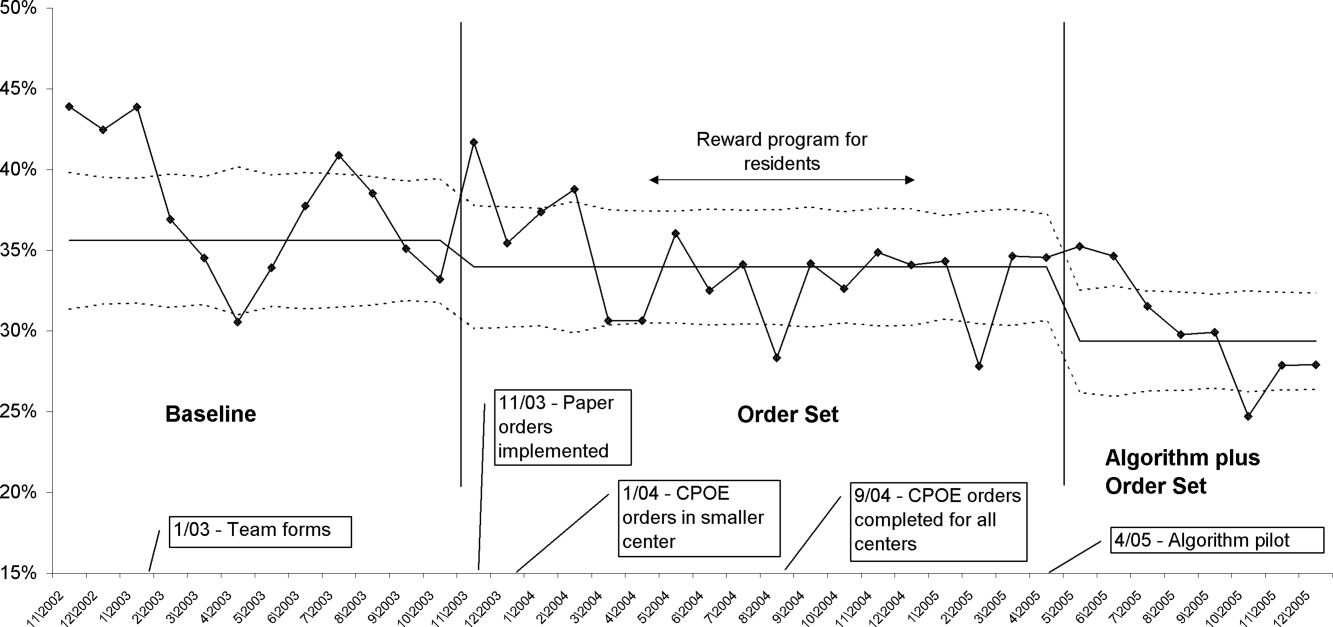

A total of 562 glucose measurements were collected during the last 12 hours on the IIP, whereas 201 were collected during the first 12 hours immediately following the IIP. Patients demonstrated a significant increase in BG (mean standard deviation) during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP (168 50 mg/dL versus 123 26 mg/dL, P < 0.001). This corresponded to a significant decrease in the median (interquartile range) insulin administered during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP [8 (0‐18) units versus 40 (22‐65) units, P < 0.001; Figure 1]. A total of 1914 BG measurements were collected during the follow‐up period. Figure 2 shows mean BG values for all patients on the IIP compared to mean BG values for each day of the follow‐up period. There was a significant increase in mean BG measurements when the IIP was compared to each day of the follow‐up period, but there was no difference between days of the follow‐up period. Table 2 shows the proportion of patients experiencing at least 1 episode of hyperglycemia (BG > 150 mg/dL), significant hyperglycemia (BG > 200 mg/dL), severe hyperglycemia (BG > 300 mg/dL), or hypoglycemia (BG < 60 mg/dL) while receiving the IIP and during the follow‐up period. When comparing the IIP to the follow‐up period, we found a significant increase in the proportion of patients with at least 1 BG > 150 mg/dL. This was also true for patients with a BG of > 200 mg/dL.

| IIP (n = 65) | Day 1 (n = 65) | Day 2 (n = 65) | Day 3 (n = 64) | Day 4 (n = 62) | Day 5 (n = 59) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Patients with >150 mg/dL, n (%) | 33 (51) | 54 (83)* | 54 (83)* | 52 (81)* | 51 (82)* | 48 (81)* |

| Patients with >200 mg/dL, n (%) | 11 (17) | 37 (57)* | 31 (48)* | 26 (41)* | 33 (53)* | 34 (58)* |

| Patients with >300 mg/dL, n (%) | 2 (3) | 11 (17) | 7 (11) | 8 (12) | 5 (8) | 10 (17) |

| Patients with <60 mg/dL, n (%) | 6 (9) | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

The only independent predictor of a greater than 30% change in mean BG was the requirement for more than 20 units of insulin (>1.7 units/hour) during the last 12 hours on the IIP. The odds of a greater than 30% change was 4.62 times higher (95% confidence interval: 1.1718.17) in patients requiring more than 20 units during the last 12 hours on IIP after adjustments for stability on the protocol and past medical history of diabetes. Stability on the protocol was not identified as an independent predictor, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.40 (95% confidence interval: 0.797.32).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to describe glycemic control following the transition from an IIP to subcutaneous insulin. We observed that during the 5 days following discontinuation of an IIP, patients had significantly elevated mean BG values. These data are highlighted by the fact that patients received significantly less insulin during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP. Additionally, a larger than expected proportion of patients exhibited at least 1 episode of hyperglycemia during the follow‐up period. We also found that an increased insulin requirement of >1.7 units/hour during the last 12 hours of the IIP was an independent risk factor for a greater than 30% increase in mean BG on day 1 of the follow‐up period.

Increasing evidence demonstrates that the development of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting is a marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality. In fact, hyperglycemia has been associated with prolonged hospital stay, infection, disability after discharge, and death in patients on general surgical and medical wards.1012 This makes the increase in mean BG found in our study following discontinuation of the IIP a concern.

SSI with subcutaneous short‐acting insulin has been used for inpatients as the standard of care for many years. However, evidence supporting the effectiveness of SSI alone is lacking, and it is not recommended by the American Diabetes Association.13 Queale et al.14 showed that SSI regimens when used alone were associated with suboptimal glycemic control and a 3‐fold higher risk of hyperglycemic episodes.1 Two retrospective studies have also demonstrated that SSI is less effective and widely variable in comparison with proactive preventative therapy.15, 16 In the current study, 58.5% of patients received SSI alone during the follow‐up period. As indicated in Figure 1, there was a significant increase in mean BG during this time interval. The choice of an inappropriate insulin regimen might be a contributing factor to poor glycemic control.

Because only 38.5% of patients were transitioned to scheduled insulin in our study, one possible strategy to help improve glycemic control would be to transition patients to a scheduled insulin regimen. Umpierrez et al.12 conducted a prospective, multicenter randomized trial to compare the efficacy and safety of a basal‐bolus insulin regimen with that of SSI in hospitalized type 2 diabetics. These authors found that patients treated with insulin glargine and glulisine had greater improvement in glycemic control than those treated with SSI (P < 0.01).12 Interestingly, the basal‐bolus method provides a maintenance insulin regimen that is aggressively titrated upward as well as an adjustable SSI based on insulin sensitivity. Patients in the current study may have benefited from a similar approach as many did not have their scheduled insulin adjusted despite persistent hyperglycemia.

With the increasing evidence for tight glycemic control in the ICU, a standardized transition from an intensive insulin infusion to a subcutaneous basal‐bolus regimen or other scheduled regimen is needed. To date, the current study is the first to describe this transition. Based on these data, recommendations for transitioning patients off an IIP provided by Furnary and Braithwaite17 should be considered by clinicians. In fact, one of their proposed predictors for unsuccessful transition was an insulin requirement of 2 units/hour. Indeed, the only independent risk factor for poor glycemic control identified in the current study was a requirement of >20 units (>1.7 units/hour) during the last 12 hours of the IIP. Further research is required to verify the other predictors suggested by Furnary and Braithwaite. They recommended using a standardized conversion protocol to transition patients off an IIP.

More recently, Kitabchi et al.18 recommended that a BG target of less than 180 mg/dL be maintained for the hospitalized patient.18 Although our study showed a mean BG less than 180 mg/dL during the follow‐up period, the variability in these values raises concerns for individual patients.

The current study is limited by its size and retrospective nature. As with all retrospective studies, the inability to control the implementation and discontinuation of the IIP may confound the results. However, this study demonstrates a real world experience with an IIP and illustrates the difficulties with transitioning patients to a subcutaneous regimen. BG values and administered insulin were collected only for the last 12 hours on the IIP. This duration is considered appropriate as this time period is used clinically at MUH, and previous recommendations for transitioning patients suggest using a time period of 6 to 8 hours to guide the transition insulin regimen.17 In addition, data regarding the severity of illness and new onset of infections were not collected for patients in the study. Both could affect glucose control. All patients had to be in an ICU to receive the IIP, but their location during the follow‐up period varied. Although these data were not available, control of BG is a problem that should be addressed whether the patient is in the ICU or not. Another possible limitation of the study was the identification of patients with or without a past medical history of DM. The inability to identify new‐onset or previously undiagnosed DM may have affected analyses based on this variable.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated a significant increase in mean BG following discontinuation of an IIP; this corresponded to a significant decrease in the amount of insulin administered. This increase was sustained for a period of at least 5 days. Additionally, an independent risk factor for poor glycemic control immediately following discontinuation of an IIP was an insulin requirement of >1.7 units/hour during the previous 12 hours. Further study into transitioning off an IIP is warranted.

- ,,.Stress‐induced hyperglycemia.Crit Care Clin.2001;17:107–124.

- .Alterations in carbohydrate metabolism during stress: a review of the literature.Am J Med.1995;98:75–84.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients.N Engl J Med.2001;345:1359–1367.

- .Effect of an intensive glucose management protocol on the mortality of critically ill adult patients.Mayo Clin Proc.2004;79(8):992–1000.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU.N Engl J Med.2006;354:449–461.

- ,,, et al.Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI 2) effects on mortality and morbidity.Eur Heart J.2005;26:651–661.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in mixed medical/surgical intensive care units.Diabetes.2006;55:3151–3159.

- ,,, et al.Randomized trial of insulin‐glucose infusion followed by subcutaneous insulin treatment in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI study): effects on mortality at 1 year.J Am Coll Cardiol.1995;26:56–65.

- ,,, et al.Effect of glucose‐insulin‐potassium infusion on mortality in patients with acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: the CREATE‐ECLA randomized controlled trial.JAMA.2005;293(4):437–446.

- ,,,,,.Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes.J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:978–982.

- ,,, et al.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.2004;27:553–597.

- ,,, et al.Randomized study of basal‐bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial).Diabetes Care.2007;30(9):2181–2186.

- ,,, et al.,for the American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus.Diabetes Care.2006;29(suppl 1):43–48.

- ,,.Glycemic control and sliding scale insulin use in medical inpatients with diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.1997;157(5):545–552.

- ,,,,.Management of diabetes mellitus in hospitalized patients: efficiency and effectiveness of sliding‐scale insulin therapy.Pharmacotherapy.2006;26(10):1421–1432.

- ,,,,.Efficacy of sliding‐scale insulin therapy: a comparison with prospective regimens.Fam Pract Res J.1994;14(4):313–322.

- ,.Effects of outcome on in‐hospital transition from intravenous insulin infusion to subcutaneous therapy.Am J Cardiol.2006;98:557–564.

- ,,.Evidence for strict inpatient blood glucose control: time to revise glycemic goals in hospitalized patients.Metabolism.2008;57:116–120.

Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance are common occurrences in critically ill patients, even those without a past medical history of diabetes.1, 2 This hyperglycemic state is associated with adverse outcomes, including severe infections, polyneuropathy, multiple‐organ failure, and death.3 Several studies have shown benefit in keeping patients' blood glucose (BG) tightly controlled.37 In a randomized controlled study, strict BG control (80‐110 mg/dL) with an insulin drip significantly reduced morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients.3 A recent meta‐analysis concluded that avoiding BG levels >150 mg/dL appeared to be crucial to reducing mortality in a mixed medical and surgical intensive care unit (ICU) population.7

The Diabetes Mellitus Insulin‐Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction study addressed the issue of tight glycemic control both acutely and chronically in 620 diabetic patients postmyocardial infarction. Patients were randomized to tight glycemic control (126‐180 mg/dL) followed by a transition to maintenance insulin or to standard care. This intervention demonstrated a sustained mortality reduction of 7.5% at 1 year.8 In contrast, the CREATE‐ECLA study showed a neutral mortality benefit of a short‐term (24‐hour) insulin infusion in postmyocardial infarction patients.9 These data demonstrate the need for clinicians to consider insulin requirements throughout the hospital stay and after discharge. To date, there are no published studies evaluating glycemic control following discontinuation of an intensive insulin protocol (IIP). Therefore, the current study was conducted to compare BG control during the use of an IIP and for the 5 days following intensive insulin therapy.

METHODS

Patient Population

This retrospective chart review was conducted at Methodist University Hospital (MUH), Memphis, TN. MUH is a 500‐bed, university‐affiliated tertiary referral hospital. The study was approved by the hospital institutional review board. From January 2006 to January 2007, a computer‐generated pharmacy report was used to identify all patients receiving the hospital‐approved IIP. Patients were included if they were 18 years old and received the IIP for 24 hours. Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (1) complete BG measurements were not retrievable while the patient received the IIP or for the 5 days following discontinuation of the IIP, (2) the patient died while receiving the IIP, and (3) an endocrinologist was involved in the care of the patient.

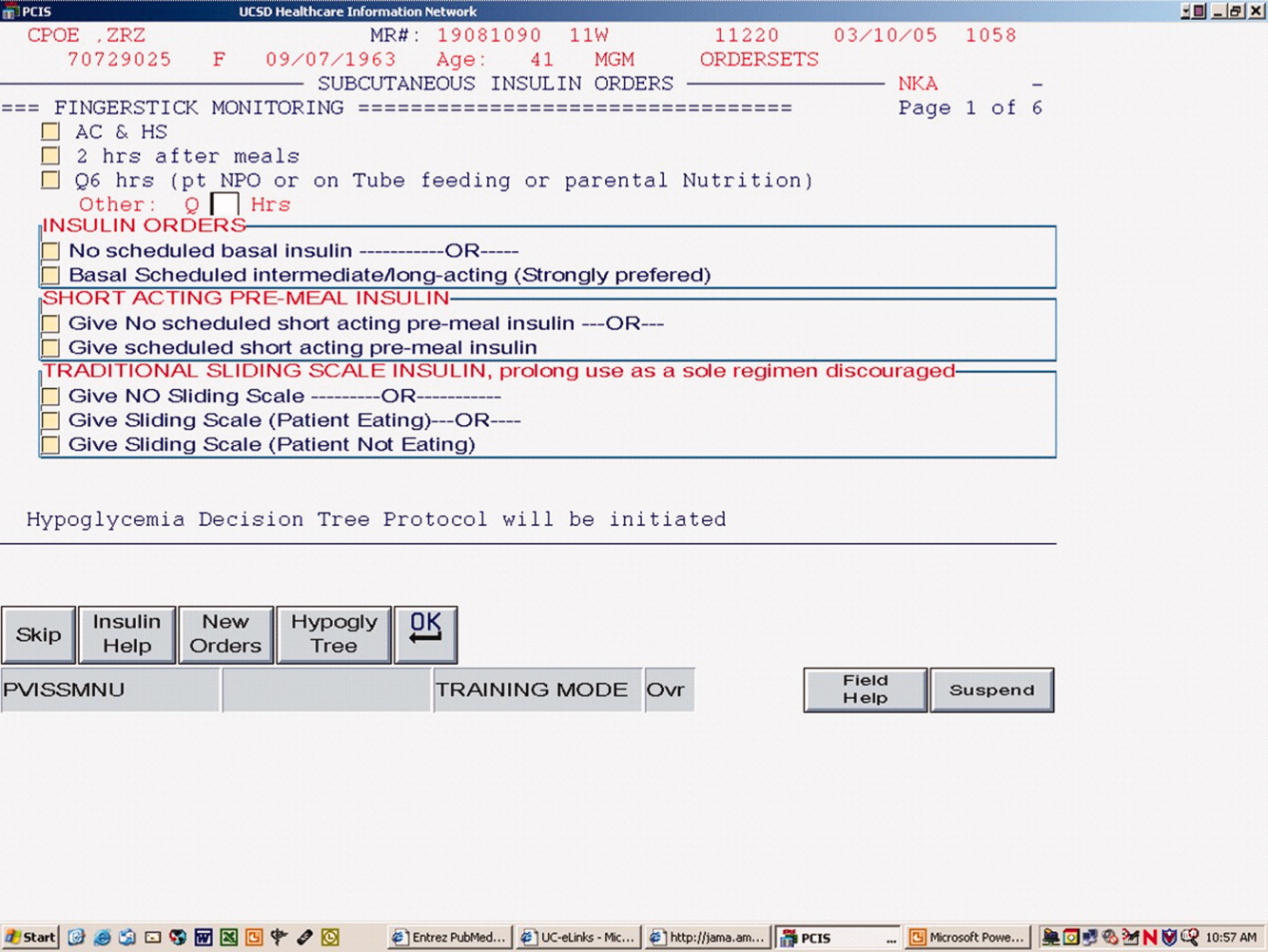

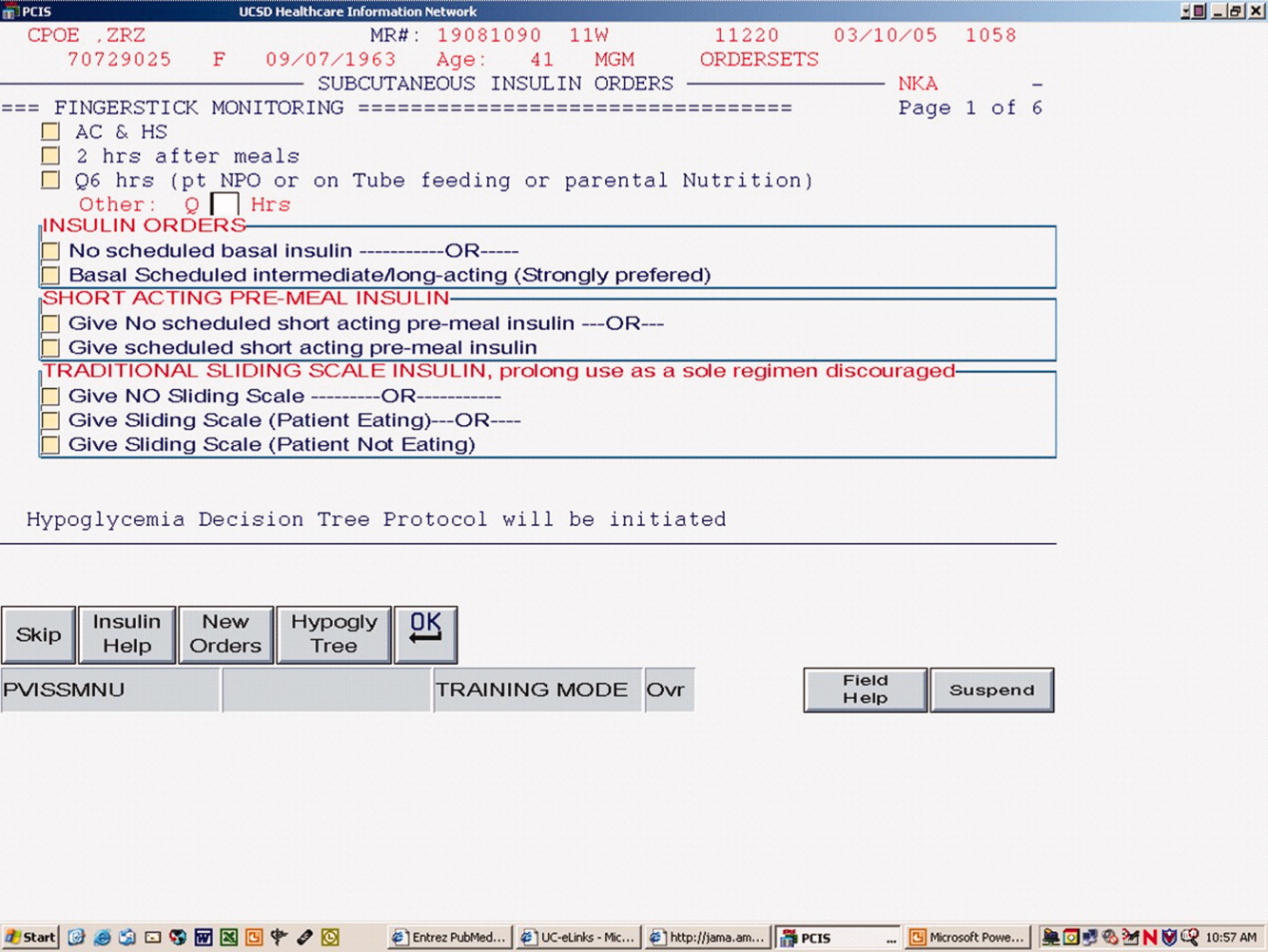

IIP

The hospital‐approved IIP is a paper‐based, physician‐initiated, nurse‐managed protocol. Criteria required before initiating the IIP include (1) ICU admission, (2) 2 BG measurements >150 mg/dL, (3) administration of continuous exogenous glucose, and (4) absence of diabetic ketoacidosis. The goal range of the IIP is 80 to 150 mg/dL. Hourly BG measurements are initially required, but as control is achieved, measurements may be extended to every 2 hours and then every 4 hours. In general, the criteria used for transitioning off the IIP include stability during the last 12 hours. Patients were considered to be stable on the IIP if they had >70% of their glucose measurements within the goal range during the last 12 hours.

Data Collection

When inclusion criteria were met, patients' medical records were reviewed. Data collection included basic demographic information, concurrent medications, duration of IIP, amount of insulin administered during the last 12 hours of the IIP, insulin regimen post‐IIP, and BG measurements during the last 12 hours on the IIP and for a total of 5 days after the IIP was stopped (follow‐up period). For this study, hyperglycemia was defined as a BG value >150 mg/dL, significant hyperglycemia was defined as >200 mg/dL, and severe hyperglycemia was defined as >300 mg/dL. Hypoglycemia was defined as a BG value <60 mg/dL. The values of <60 mg/dL, >150 mg/dL, and >200 mg/dL were chosen on the basis of the criteria used in the MUH IIP and standard sliding‐scale protocols. A value of >300 mg/dL was used to better describe patients with hyperglycemia. Poor glycemic control following the IIP was defined as a >30% change in mean BG during the last 12 hours on the drip and on the first day after discontinuation of the drip.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of this study was to compare BG control during the last 12 hours of an IIP and for the 5 days following its discontinuation. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the incidence of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia during the transition period and to identify patients at risk of poor glycemic control following discontinuation of the IIP. Continuous data are appropriately reported as the mean standard deviation or median (interquartile range), depending on the distribution. Continuous variables were compared with the Student t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test. Discrete variables were compared with chi‐square analysis and Bonferroni Correction where appropriate. For comparisons of BG during the IIP and on days 1 to 5 of the follow‐up period, repeated‐measures analysis of variance on ranks was conducted because of the distribution. These statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat version 2.03 (Systat Software, Inc., Richmond, VA). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. However, when the Bonferroni correction was used, a value of less than 0.01 was considered significant. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine independent predictors of a greater than 30% change in the mean BG value between the last 12 hours of the IIP and the first day off the insulin drip. Potential independent variables included in the analysis were stability on protocol, requiring less than 20 units of insulin in the last 12 hours on the IIP, use of antibiotics, use of steroids, history of diabetes, and type of insulin to which the patient was transitioned (none, sliding scale, and scheduled and sliding scale). The model was built in a backwards, stepwise fashion with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 171 patients received the IIP during the study period. Ninety‐seven patients did not meet inclusion criteria because they received the IIP for less than 24 hours. Of the 74 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 9 were excluded (5 had insufficient glucose data, 3 were cared for by an endocrinologist, and 1 died while receiving the IIP). Thus, 65 patients were included in the study.

Table 1 lists the baseline demographics for all patients and those with and without a history of diabetes mellitus (DM). The majority of the patients (n = 49) underwent a surgical procedure, with the most common procedure being coronary artery bypass graft (n = 38). Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft had the IIP included in their standard postoperative order set. The majority of patients were considered stable during the 12 hours prior to discontinuation of the IIP, including 23 patients with a history of DM. Of the 65 patients who were included in the study, 25 (38.5%) received a scheduled insulin order following discontinuation of the IIP, whereas 38 (58.5%) received some form of sliding‐scale insulin (SSI). Additionally, 2 (3%) patients did not receive any form of insulin order after stopping the IIP. Of those receiving scheduled insulin, 15 (60%) received neutral protamine Hagedorn, 5 (20%) received glargine, 5 (20%) received 70/30, and 1 (4%) received regular insulin. Of those receiving SSI only, the prescribed frequency was as follows: every 4 hours for 17 (45%), before meals and at bedtime for 15 (39%), every 6 hours for 5 (13%), and every 2 hours for 1 (3%).

| All Patients (n = 65) | PMH of DM (n = 36) | No PMH of DM (n = 29) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, mean years SD | 62 11 | 61 10 | 64 12 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 38 (58) | 22 (61) | 16 (55.2) |

| BMI SD | 30 7.2 | 31 7 | 30 6.5 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 49 (74.2) | 27 (75) | 21 (72.4) |

| CABG, n | 38 | 22 | 16 |

| Liver transplant, n | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| Other, n | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Last 24 hours on IIP, n (%) | |||

| Ventilator | 37 (56.9) | 22 (61.1) | 15 (51.7) |

| Antibiotics | 37 (56.9) | 20 (55.6) | 17 (58.6) |

| Vasopressors | 11 (16.9) | 5 (13.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| Hemodialysis | 8 (12.3) | 5 (13.9) | 3 (10.3) |

| Steroids | 16 (24.6) | 9 (25) | 7 (24.1) |

| Duration of IIP, mean hours SD | 72 65 | 80 78 | 62 45 |

| Insulin during last 12 hours of IIP, mean units SD | 47 37 | 51 30 | 46 45 |

| Type of insulin received following IIP, n (%) | |||

| Scheduled + sliding scale | 25 (38.5) | 19 (52.8) | 6 (20.7) |

| Sliding scale only | 38 (58.5) | 16 (44.4) | 22 (75.9) |

| None | 2 (3) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.4) |

| Total daily insulin following IIP, mean units SD | 28 41 | 38 49 | 17 24 |

| Patients stable on IIP | 44 (67.7) | 23 (64.8) | 21 (72.4) |

| Hospital LOS, mean days SD | 24 18 | 24 17 | 23 19 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 15 (23.1) | 5 (13.8) | 10 (34.5) |

A total of 562 glucose measurements were collected during the last 12 hours on the IIP, whereas 201 were collected during the first 12 hours immediately following the IIP. Patients demonstrated a significant increase in BG (mean standard deviation) during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP (168 50 mg/dL versus 123 26 mg/dL, P < 0.001). This corresponded to a significant decrease in the median (interquartile range) insulin administered during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP [8 (0‐18) units versus 40 (22‐65) units, P < 0.001; Figure 1]. A total of 1914 BG measurements were collected during the follow‐up period. Figure 2 shows mean BG values for all patients on the IIP compared to mean BG values for each day of the follow‐up period. There was a significant increase in mean BG measurements when the IIP was compared to each day of the follow‐up period, but there was no difference between days of the follow‐up period. Table 2 shows the proportion of patients experiencing at least 1 episode of hyperglycemia (BG > 150 mg/dL), significant hyperglycemia (BG > 200 mg/dL), severe hyperglycemia (BG > 300 mg/dL), or hypoglycemia (BG < 60 mg/dL) while receiving the IIP and during the follow‐up period. When comparing the IIP to the follow‐up period, we found a significant increase in the proportion of patients with at least 1 BG > 150 mg/dL. This was also true for patients with a BG of > 200 mg/dL.

| IIP (n = 65) | Day 1 (n = 65) | Day 2 (n = 65) | Day 3 (n = 64) | Day 4 (n = 62) | Day 5 (n = 59) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Patients with >150 mg/dL, n (%) | 33 (51) | 54 (83)* | 54 (83)* | 52 (81)* | 51 (82)* | 48 (81)* |

| Patients with >200 mg/dL, n (%) | 11 (17) | 37 (57)* | 31 (48)* | 26 (41)* | 33 (53)* | 34 (58)* |

| Patients with >300 mg/dL, n (%) | 2 (3) | 11 (17) | 7 (11) | 8 (12) | 5 (8) | 10 (17) |

| Patients with <60 mg/dL, n (%) | 6 (9) | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

The only independent predictor of a greater than 30% change in mean BG was the requirement for more than 20 units of insulin (>1.7 units/hour) during the last 12 hours on the IIP. The odds of a greater than 30% change was 4.62 times higher (95% confidence interval: 1.1718.17) in patients requiring more than 20 units during the last 12 hours on IIP after adjustments for stability on the protocol and past medical history of diabetes. Stability on the protocol was not identified as an independent predictor, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.40 (95% confidence interval: 0.797.32).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to describe glycemic control following the transition from an IIP to subcutaneous insulin. We observed that during the 5 days following discontinuation of an IIP, patients had significantly elevated mean BG values. These data are highlighted by the fact that patients received significantly less insulin during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP. Additionally, a larger than expected proportion of patients exhibited at least 1 episode of hyperglycemia during the follow‐up period. We also found that an increased insulin requirement of >1.7 units/hour during the last 12 hours of the IIP was an independent risk factor for a greater than 30% increase in mean BG on day 1 of the follow‐up period.

Increasing evidence demonstrates that the development of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting is a marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality. In fact, hyperglycemia has been associated with prolonged hospital stay, infection, disability after discharge, and death in patients on general surgical and medical wards.1012 This makes the increase in mean BG found in our study following discontinuation of the IIP a concern.

SSI with subcutaneous short‐acting insulin has been used for inpatients as the standard of care for many years. However, evidence supporting the effectiveness of SSI alone is lacking, and it is not recommended by the American Diabetes Association.13 Queale et al.14 showed that SSI regimens when used alone were associated with suboptimal glycemic control and a 3‐fold higher risk of hyperglycemic episodes.1 Two retrospective studies have also demonstrated that SSI is less effective and widely variable in comparison with proactive preventative therapy.15, 16 In the current study, 58.5% of patients received SSI alone during the follow‐up period. As indicated in Figure 1, there was a significant increase in mean BG during this time interval. The choice of an inappropriate insulin regimen might be a contributing factor to poor glycemic control.

Because only 38.5% of patients were transitioned to scheduled insulin in our study, one possible strategy to help improve glycemic control would be to transition patients to a scheduled insulin regimen. Umpierrez et al.12 conducted a prospective, multicenter randomized trial to compare the efficacy and safety of a basal‐bolus insulin regimen with that of SSI in hospitalized type 2 diabetics. These authors found that patients treated with insulin glargine and glulisine had greater improvement in glycemic control than those treated with SSI (P < 0.01).12 Interestingly, the basal‐bolus method provides a maintenance insulin regimen that is aggressively titrated upward as well as an adjustable SSI based on insulin sensitivity. Patients in the current study may have benefited from a similar approach as many did not have their scheduled insulin adjusted despite persistent hyperglycemia.

With the increasing evidence for tight glycemic control in the ICU, a standardized transition from an intensive insulin infusion to a subcutaneous basal‐bolus regimen or other scheduled regimen is needed. To date, the current study is the first to describe this transition. Based on these data, recommendations for transitioning patients off an IIP provided by Furnary and Braithwaite17 should be considered by clinicians. In fact, one of their proposed predictors for unsuccessful transition was an insulin requirement of 2 units/hour. Indeed, the only independent risk factor for poor glycemic control identified in the current study was a requirement of >20 units (>1.7 units/hour) during the last 12 hours of the IIP. Further research is required to verify the other predictors suggested by Furnary and Braithwaite. They recommended using a standardized conversion protocol to transition patients off an IIP.

More recently, Kitabchi et al.18 recommended that a BG target of less than 180 mg/dL be maintained for the hospitalized patient.18 Although our study showed a mean BG less than 180 mg/dL during the follow‐up period, the variability in these values raises concerns for individual patients.

The current study is limited by its size and retrospective nature. As with all retrospective studies, the inability to control the implementation and discontinuation of the IIP may confound the results. However, this study demonstrates a real world experience with an IIP and illustrates the difficulties with transitioning patients to a subcutaneous regimen. BG values and administered insulin were collected only for the last 12 hours on the IIP. This duration is considered appropriate as this time period is used clinically at MUH, and previous recommendations for transitioning patients suggest using a time period of 6 to 8 hours to guide the transition insulin regimen.17 In addition, data regarding the severity of illness and new onset of infections were not collected for patients in the study. Both could affect glucose control. All patients had to be in an ICU to receive the IIP, but their location during the follow‐up period varied. Although these data were not available, control of BG is a problem that should be addressed whether the patient is in the ICU or not. Another possible limitation of the study was the identification of patients with or without a past medical history of DM. The inability to identify new‐onset or previously undiagnosed DM may have affected analyses based on this variable.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated a significant increase in mean BG following discontinuation of an IIP; this corresponded to a significant decrease in the amount of insulin administered. This increase was sustained for a period of at least 5 days. Additionally, an independent risk factor for poor glycemic control immediately following discontinuation of an IIP was an insulin requirement of >1.7 units/hour during the previous 12 hours. Further study into transitioning off an IIP is warranted.

Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance are common occurrences in critically ill patients, even those without a past medical history of diabetes.1, 2 This hyperglycemic state is associated with adverse outcomes, including severe infections, polyneuropathy, multiple‐organ failure, and death.3 Several studies have shown benefit in keeping patients' blood glucose (BG) tightly controlled.37 In a randomized controlled study, strict BG control (80‐110 mg/dL) with an insulin drip significantly reduced morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients.3 A recent meta‐analysis concluded that avoiding BG levels >150 mg/dL appeared to be crucial to reducing mortality in a mixed medical and surgical intensive care unit (ICU) population.7

The Diabetes Mellitus Insulin‐Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction study addressed the issue of tight glycemic control both acutely and chronically in 620 diabetic patients postmyocardial infarction. Patients were randomized to tight glycemic control (126‐180 mg/dL) followed by a transition to maintenance insulin or to standard care. This intervention demonstrated a sustained mortality reduction of 7.5% at 1 year.8 In contrast, the CREATE‐ECLA study showed a neutral mortality benefit of a short‐term (24‐hour) insulin infusion in postmyocardial infarction patients.9 These data demonstrate the need for clinicians to consider insulin requirements throughout the hospital stay and after discharge. To date, there are no published studies evaluating glycemic control following discontinuation of an intensive insulin protocol (IIP). Therefore, the current study was conducted to compare BG control during the use of an IIP and for the 5 days following intensive insulin therapy.

METHODS

Patient Population

This retrospective chart review was conducted at Methodist University Hospital (MUH), Memphis, TN. MUH is a 500‐bed, university‐affiliated tertiary referral hospital. The study was approved by the hospital institutional review board. From January 2006 to January 2007, a computer‐generated pharmacy report was used to identify all patients receiving the hospital‐approved IIP. Patients were included if they were 18 years old and received the IIP for 24 hours. Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (1) complete BG measurements were not retrievable while the patient received the IIP or for the 5 days following discontinuation of the IIP, (2) the patient died while receiving the IIP, and (3) an endocrinologist was involved in the care of the patient.

IIP

The hospital‐approved IIP is a paper‐based, physician‐initiated, nurse‐managed protocol. Criteria required before initiating the IIP include (1) ICU admission, (2) 2 BG measurements >150 mg/dL, (3) administration of continuous exogenous glucose, and (4) absence of diabetic ketoacidosis. The goal range of the IIP is 80 to 150 mg/dL. Hourly BG measurements are initially required, but as control is achieved, measurements may be extended to every 2 hours and then every 4 hours. In general, the criteria used for transitioning off the IIP include stability during the last 12 hours. Patients were considered to be stable on the IIP if they had >70% of their glucose measurements within the goal range during the last 12 hours.

Data Collection

When inclusion criteria were met, patients' medical records were reviewed. Data collection included basic demographic information, concurrent medications, duration of IIP, amount of insulin administered during the last 12 hours of the IIP, insulin regimen post‐IIP, and BG measurements during the last 12 hours on the IIP and for a total of 5 days after the IIP was stopped (follow‐up period). For this study, hyperglycemia was defined as a BG value >150 mg/dL, significant hyperglycemia was defined as >200 mg/dL, and severe hyperglycemia was defined as >300 mg/dL. Hypoglycemia was defined as a BG value <60 mg/dL. The values of <60 mg/dL, >150 mg/dL, and >200 mg/dL were chosen on the basis of the criteria used in the MUH IIP and standard sliding‐scale protocols. A value of >300 mg/dL was used to better describe patients with hyperglycemia. Poor glycemic control following the IIP was defined as a >30% change in mean BG during the last 12 hours on the drip and on the first day after discontinuation of the drip.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of this study was to compare BG control during the last 12 hours of an IIP and for the 5 days following its discontinuation. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the incidence of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia during the transition period and to identify patients at risk of poor glycemic control following discontinuation of the IIP. Continuous data are appropriately reported as the mean standard deviation or median (interquartile range), depending on the distribution. Continuous variables were compared with the Student t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test. Discrete variables were compared with chi‐square analysis and Bonferroni Correction where appropriate. For comparisons of BG during the IIP and on days 1 to 5 of the follow‐up period, repeated‐measures analysis of variance on ranks was conducted because of the distribution. These statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat version 2.03 (Systat Software, Inc., Richmond, VA). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. However, when the Bonferroni correction was used, a value of less than 0.01 was considered significant. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine independent predictors of a greater than 30% change in the mean BG value between the last 12 hours of the IIP and the first day off the insulin drip. Potential independent variables included in the analysis were stability on protocol, requiring less than 20 units of insulin in the last 12 hours on the IIP, use of antibiotics, use of steroids, history of diabetes, and type of insulin to which the patient was transitioned (none, sliding scale, and scheduled and sliding scale). The model was built in a backwards, stepwise fashion with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 171 patients received the IIP during the study period. Ninety‐seven patients did not meet inclusion criteria because they received the IIP for less than 24 hours. Of the 74 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 9 were excluded (5 had insufficient glucose data, 3 were cared for by an endocrinologist, and 1 died while receiving the IIP). Thus, 65 patients were included in the study.

Table 1 lists the baseline demographics for all patients and those with and without a history of diabetes mellitus (DM). The majority of the patients (n = 49) underwent a surgical procedure, with the most common procedure being coronary artery bypass graft (n = 38). Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft had the IIP included in their standard postoperative order set. The majority of patients were considered stable during the 12 hours prior to discontinuation of the IIP, including 23 patients with a history of DM. Of the 65 patients who were included in the study, 25 (38.5%) received a scheduled insulin order following discontinuation of the IIP, whereas 38 (58.5%) received some form of sliding‐scale insulin (SSI). Additionally, 2 (3%) patients did not receive any form of insulin order after stopping the IIP. Of those receiving scheduled insulin, 15 (60%) received neutral protamine Hagedorn, 5 (20%) received glargine, 5 (20%) received 70/30, and 1 (4%) received regular insulin. Of those receiving SSI only, the prescribed frequency was as follows: every 4 hours for 17 (45%), before meals and at bedtime for 15 (39%), every 6 hours for 5 (13%), and every 2 hours for 1 (3%).

| All Patients (n = 65) | PMH of DM (n = 36) | No PMH of DM (n = 29) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, mean years SD | 62 11 | 61 10 | 64 12 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 38 (58) | 22 (61) | 16 (55.2) |

| BMI SD | 30 7.2 | 31 7 | 30 6.5 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 49 (74.2) | 27 (75) | 21 (72.4) |

| CABG, n | 38 | 22 | 16 |

| Liver transplant, n | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| Other, n | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Last 24 hours on IIP, n (%) | |||

| Ventilator | 37 (56.9) | 22 (61.1) | 15 (51.7) |

| Antibiotics | 37 (56.9) | 20 (55.6) | 17 (58.6) |

| Vasopressors | 11 (16.9) | 5 (13.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| Hemodialysis | 8 (12.3) | 5 (13.9) | 3 (10.3) |

| Steroids | 16 (24.6) | 9 (25) | 7 (24.1) |

| Duration of IIP, mean hours SD | 72 65 | 80 78 | 62 45 |

| Insulin during last 12 hours of IIP, mean units SD | 47 37 | 51 30 | 46 45 |

| Type of insulin received following IIP, n (%) | |||

| Scheduled + sliding scale | 25 (38.5) | 19 (52.8) | 6 (20.7) |

| Sliding scale only | 38 (58.5) | 16 (44.4) | 22 (75.9) |

| None | 2 (3) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.4) |

| Total daily insulin following IIP, mean units SD | 28 41 | 38 49 | 17 24 |

| Patients stable on IIP | 44 (67.7) | 23 (64.8) | 21 (72.4) |

| Hospital LOS, mean days SD | 24 18 | 24 17 | 23 19 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 15 (23.1) | 5 (13.8) | 10 (34.5) |

A total of 562 glucose measurements were collected during the last 12 hours on the IIP, whereas 201 were collected during the first 12 hours immediately following the IIP. Patients demonstrated a significant increase in BG (mean standard deviation) during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP (168 50 mg/dL versus 123 26 mg/dL, P < 0.001). This corresponded to a significant decrease in the median (interquartile range) insulin administered during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP [8 (0‐18) units versus 40 (22‐65) units, P < 0.001; Figure 1]. A total of 1914 BG measurements were collected during the follow‐up period. Figure 2 shows mean BG values for all patients on the IIP compared to mean BG values for each day of the follow‐up period. There was a significant increase in mean BG measurements when the IIP was compared to each day of the follow‐up period, but there was no difference between days of the follow‐up period. Table 2 shows the proportion of patients experiencing at least 1 episode of hyperglycemia (BG > 150 mg/dL), significant hyperglycemia (BG > 200 mg/dL), severe hyperglycemia (BG > 300 mg/dL), or hypoglycemia (BG < 60 mg/dL) while receiving the IIP and during the follow‐up period. When comparing the IIP to the follow‐up period, we found a significant increase in the proportion of patients with at least 1 BG > 150 mg/dL. This was also true for patients with a BG of > 200 mg/dL.

| IIP (n = 65) | Day 1 (n = 65) | Day 2 (n = 65) | Day 3 (n = 64) | Day 4 (n = 62) | Day 5 (n = 59) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Patients with >150 mg/dL, n (%) | 33 (51) | 54 (83)* | 54 (83)* | 52 (81)* | 51 (82)* | 48 (81)* |

| Patients with >200 mg/dL, n (%) | 11 (17) | 37 (57)* | 31 (48)* | 26 (41)* | 33 (53)* | 34 (58)* |

| Patients with >300 mg/dL, n (%) | 2 (3) | 11 (17) | 7 (11) | 8 (12) | 5 (8) | 10 (17) |

| Patients with <60 mg/dL, n (%) | 6 (9) | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

The only independent predictor of a greater than 30% change in mean BG was the requirement for more than 20 units of insulin (>1.7 units/hour) during the last 12 hours on the IIP. The odds of a greater than 30% change was 4.62 times higher (95% confidence interval: 1.1718.17) in patients requiring more than 20 units during the last 12 hours on IIP after adjustments for stability on the protocol and past medical history of diabetes. Stability on the protocol was not identified as an independent predictor, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.40 (95% confidence interval: 0.797.32).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to describe glycemic control following the transition from an IIP to subcutaneous insulin. We observed that during the 5 days following discontinuation of an IIP, patients had significantly elevated mean BG values. These data are highlighted by the fact that patients received significantly less insulin during the first 12 hours of the follow‐up period versus the last 12 hours of the IIP. Additionally, a larger than expected proportion of patients exhibited at least 1 episode of hyperglycemia during the follow‐up period. We also found that an increased insulin requirement of >1.7 units/hour during the last 12 hours of the IIP was an independent risk factor for a greater than 30% increase in mean BG on day 1 of the follow‐up period.

Increasing evidence demonstrates that the development of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting is a marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality. In fact, hyperglycemia has been associated with prolonged hospital stay, infection, disability after discharge, and death in patients on general surgical and medical wards.1012 This makes the increase in mean BG found in our study following discontinuation of the IIP a concern.

SSI with subcutaneous short‐acting insulin has been used for inpatients as the standard of care for many years. However, evidence supporting the effectiveness of SSI alone is lacking, and it is not recommended by the American Diabetes Association.13 Queale et al.14 showed that SSI regimens when used alone were associated with suboptimal glycemic control and a 3‐fold higher risk of hyperglycemic episodes.1 Two retrospective studies have also demonstrated that SSI is less effective and widely variable in comparison with proactive preventative therapy.15, 16 In the current study, 58.5% of patients received SSI alone during the follow‐up period. As indicated in Figure 1, there was a significant increase in mean BG during this time interval. The choice of an inappropriate insulin regimen might be a contributing factor to poor glycemic control.

Because only 38.5% of patients were transitioned to scheduled insulin in our study, one possible strategy to help improve glycemic control would be to transition patients to a scheduled insulin regimen. Umpierrez et al.12 conducted a prospective, multicenter randomized trial to compare the efficacy and safety of a basal‐bolus insulin regimen with that of SSI in hospitalized type 2 diabetics. These authors found that patients treated with insulin glargine and glulisine had greater improvement in glycemic control than those treated with SSI (P < 0.01).12 Interestingly, the basal‐bolus method provides a maintenance insulin regimen that is aggressively titrated upward as well as an adjustable SSI based on insulin sensitivity. Patients in the current study may have benefited from a similar approach as many did not have their scheduled insulin adjusted despite persistent hyperglycemia.

With the increasing evidence for tight glycemic control in the ICU, a standardized transition from an intensive insulin infusion to a subcutaneous basal‐bolus regimen or other scheduled regimen is needed. To date, the current study is the first to describe this transition. Based on these data, recommendations for transitioning patients off an IIP provided by Furnary and Braithwaite17 should be considered by clinicians. In fact, one of their proposed predictors for unsuccessful transition was an insulin requirement of 2 units/hour. Indeed, the only independent risk factor for poor glycemic control identified in the current study was a requirement of >20 units (>1.7 units/hour) during the last 12 hours of the IIP. Further research is required to verify the other predictors suggested by Furnary and Braithwaite. They recommended using a standardized conversion protocol to transition patients off an IIP.

More recently, Kitabchi et al.18 recommended that a BG target of less than 180 mg/dL be maintained for the hospitalized patient.18 Although our study showed a mean BG less than 180 mg/dL during the follow‐up period, the variability in these values raises concerns for individual patients.

The current study is limited by its size and retrospective nature. As with all retrospective studies, the inability to control the implementation and discontinuation of the IIP may confound the results. However, this study demonstrates a real world experience with an IIP and illustrates the difficulties with transitioning patients to a subcutaneous regimen. BG values and administered insulin were collected only for the last 12 hours on the IIP. This duration is considered appropriate as this time period is used clinically at MUH, and previous recommendations for transitioning patients suggest using a time period of 6 to 8 hours to guide the transition insulin regimen.17 In addition, data regarding the severity of illness and new onset of infections were not collected for patients in the study. Both could affect glucose control. All patients had to be in an ICU to receive the IIP, but their location during the follow‐up period varied. Although these data were not available, control of BG is a problem that should be addressed whether the patient is in the ICU or not. Another possible limitation of the study was the identification of patients with or without a past medical history of DM. The inability to identify new‐onset or previously undiagnosed DM may have affected analyses based on this variable.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated a significant increase in mean BG following discontinuation of an IIP; this corresponded to a significant decrease in the amount of insulin administered. This increase was sustained for a period of at least 5 days. Additionally, an independent risk factor for poor glycemic control immediately following discontinuation of an IIP was an insulin requirement of >1.7 units/hour during the previous 12 hours. Further study into transitioning off an IIP is warranted.

- ,,.Stress‐induced hyperglycemia.Crit Care Clin.2001;17:107–124.

- .Alterations in carbohydrate metabolism during stress: a review of the literature.Am J Med.1995;98:75–84.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients.N Engl J Med.2001;345:1359–1367.

- .Effect of an intensive glucose management protocol on the mortality of critically ill adult patients.Mayo Clin Proc.2004;79(8):992–1000.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU.N Engl J Med.2006;354:449–461.

- ,,, et al.Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI 2) effects on mortality and morbidity.Eur Heart J.2005;26:651–661.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in mixed medical/surgical intensive care units.Diabetes.2006;55:3151–3159.

- ,,, et al.Randomized trial of insulin‐glucose infusion followed by subcutaneous insulin treatment in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI study): effects on mortality at 1 year.J Am Coll Cardiol.1995;26:56–65.

- ,,, et al.Effect of glucose‐insulin‐potassium infusion on mortality in patients with acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: the CREATE‐ECLA randomized controlled trial.JAMA.2005;293(4):437–446.

- ,,,,,.Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes.J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:978–982.

- ,,, et al.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.2004;27:553–597.

- ,,, et al.Randomized study of basal‐bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial).Diabetes Care.2007;30(9):2181–2186.

- ,,, et al.,for the American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus.Diabetes Care.2006;29(suppl 1):43–48.

- ,,.Glycemic control and sliding scale insulin use in medical inpatients with diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.1997;157(5):545–552.

- ,,,,.Management of diabetes mellitus in hospitalized patients: efficiency and effectiveness of sliding‐scale insulin therapy.Pharmacotherapy.2006;26(10):1421–1432.

- ,,,,.Efficacy of sliding‐scale insulin therapy: a comparison with prospective regimens.Fam Pract Res J.1994;14(4):313–322.

- ,.Effects of outcome on in‐hospital transition from intravenous insulin infusion to subcutaneous therapy.Am J Cardiol.2006;98:557–564.

- ,,.Evidence for strict inpatient blood glucose control: time to revise glycemic goals in hospitalized patients.Metabolism.2008;57:116–120.

- ,,.Stress‐induced hyperglycemia.Crit Care Clin.2001;17:107–124.

- .Alterations in carbohydrate metabolism during stress: a review of the literature.Am J Med.1995;98:75–84.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients.N Engl J Med.2001;345:1359–1367.

- .Effect of an intensive glucose management protocol on the mortality of critically ill adult patients.Mayo Clin Proc.2004;79(8):992–1000.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU.N Engl J Med.2006;354:449–461.

- ,,, et al.Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI 2) effects on mortality and morbidity.Eur Heart J.2005;26:651–661.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in mixed medical/surgical intensive care units.Diabetes.2006;55:3151–3159.

- ,,, et al.Randomized trial of insulin‐glucose infusion followed by subcutaneous insulin treatment in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI study): effects on mortality at 1 year.J Am Coll Cardiol.1995;26:56–65.

- ,,, et al.Effect of glucose‐insulin‐potassium infusion on mortality in patients with acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: the CREATE‐ECLA randomized controlled trial.JAMA.2005;293(4):437–446.

- ,,,,,.Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes.J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:978–982.

- ,,, et al.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.2004;27:553–597.

- ,,, et al.Randomized study of basal‐bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial).Diabetes Care.2007;30(9):2181–2186.

- ,,, et al.,for the American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus.Diabetes Care.2006;29(suppl 1):43–48.

- ,,.Glycemic control and sliding scale insulin use in medical inpatients with diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.1997;157(5):545–552.

- ,,,,.Management of diabetes mellitus in hospitalized patients: efficiency and effectiveness of sliding‐scale insulin therapy.Pharmacotherapy.2006;26(10):1421–1432.

- ,,,,.Efficacy of sliding‐scale insulin therapy: a comparison with prospective regimens.Fam Pract Res J.1994;14(4):313–322.

- ,.Effects of outcome on in‐hospital transition from intravenous insulin infusion to subcutaneous therapy.Am J Cardiol.2006;98:557–564.

- ,,.Evidence for strict inpatient blood glucose control: time to revise glycemic goals in hospitalized patients.Metabolism.2008;57:116–120.

Copyright © 2009 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pericardial Effusion

Eight days prior to admission to our hospital, a 50‐year‐old morbidly obese patient presented to his primary care clinic, complaining of weakness, dizziness, and symptoms consistent with paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had a history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, chronic renal insufficiency with baseline creatinine in the range of 2.0 mg/dL, and atrial fibrillation on warfarin (10 mg/day). He was given diuretics and sent home. Two days later, the patient presented to a rural emergency department, complaining of leg pain and swelling. He was given cephalexin for cellulitis and discharged home. The evening prior to admission to our hospital, the patient developed sharp left‐sided chest pain, orthopnea, and worsening dyspnea. He again presented to the rural emergency department and was found to have a blood pressure of 60/40 mm Hg. He was admitted and given boluses of intravenous fluids and a dose of ceftriaxone. Laboratory studies at that time demonstrated the following: sodium, 130 mEq/L; potassium, 6.5 mEq/L; CO2, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 105 mg/dL; creatinine, 5.5 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 330 IU/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 507 IU/L; and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 145 IU/L. The following morning, he was oliguric, and his liver transaminases had increased to an AST level of 1862 IU/L and an ALT level of 1055 IU/L. At this point, he was transferred to our hospital for hemodialysis with a diagnosis of acute oliguric renal failure.

On admission to our hospital, the patient was afebrile, had a blood pressure of 112/80 mm Hg, and was hypoxic with an O2 saturation of 93% on 4 L of oxygen by nasal cannula. His weight was 201 kg. He was alert and cooperative. Heart sounds were distant but had a regular rate and rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. No jugular venous pulsations were appreciated. He had decreased lung sounds throughout both lung fields. His abdomen was morbidly obese and nontender. Extremities demonstrated chronic venous stasis changes with multiple superficial ulcers and bilateral pitting edema.

In light of the elevated liver function tests reported by the referring hospital, these studies were repeated on arrival, revealing an AST level of 4780 IU/L and an ALT level of 1876 IU/L. Other initial laboratory studies demonstrated a BUN level of 116 mg/dL, a creatinine level of 6 mg/dL, a potassium level of 7.2 mEq/L, negative cardiac enzymes, and an international normalized ratio greater than 9.0. A urinalysis could not be performed because the patient was anuric. An electrocardiogram demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm with a right bundle branch block and nonspecific ST segment and T wave changes. There was no prior electrocardiogram available for comparison. Blood acetaminophen level and infectious hepatitis panels were negative.

Within 1 hour of admission, the patient became hypotensive, with his systolic blood pressure decreasing into the 70s. Over the next 24 hours, the patient was treated with intravenous fluids and pressors (neosynephrine) but remained hypotensive, with his systolic blood pressure in the range of 64 to 80 mm Hg.

At 14 hours after admission, liver function tests were repeated and revealed further elevation of his transaminases (AST, 5135 IU/L; ALT, 2468 IU/L). The diagnosis of shock liver was entertained. A portable chest X‐ray (CXR) demonstrated an enlarged cardiac silhouette suggestive of cardiomegaly or pericardial effusion. No prior CXR was available for comparison. An echocardiogram showed probable effusion but was not diagnostic secondary to his body habitus and poor windows. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a large pericardial effusion. This finding, in combination with diminished heart sounds and hypotension, presented a clinical picture consistent with cardiac tamponade. The patient underwent a subxiphoid pericardial window, and 1.5 L of bloody effusion was removed. Intraoperatively, his systolic blood pressure immediately improved from 95 to 135 mm Hg. Urine output increased from 0 to 80 mL/hour in the first hour. Five days later, his creatinine returned to his baseline of 1.9 mg/dL, and other laboratory values had decreased: AST, 306 IU/L; ALT, 520 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 122 IU/L; and BUN, 86 mg/dL.

DISCUSSION

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a common condition, with an incidence of 1% on admission to the hospital; 70% of these cases are due to prerenal causes.1 Among patients already in the hospital, prerenal azotemia is responsible for 21% to 39% of cases of ARF.2, 3 Prerenal ARF is most commonly caused by hypotension, which may be cardiogenic, hypovolemic, septic, or due to vasodilatation. Adrenal insufficiency and other etiologies should also be considered. In our patient, chronic renal failure and superimposed hypotension contributed to acute oliguric renal failure. In searching for the etiology of his hypotension, we concentrated on cardiogenic causes in view of his enlarged cardiac silhouette.

In considering the cardiogenic causes of hypotension, we did not initially focus on tamponade. Although oliguria with renal failure is recognized as a complication of cardiac tamponade, relatively little has been written about ARF as the presenting problem in tamponade. The literature is limited to a few case reports, such as those described by Queffeulou et al.4 and Saklayen et al.5 In our patient, the diagnosis of tamponade was made more difficult by the patient's large size, which made the interpretation of physical findings such as heart sounds more difficult and compromised the quality of essential imaging studies.