User login

Role of barium esophagography in evaluating dysphagia

A 55-year-old woman presents with an intermittent sensation of food getting stuck in her mid to lower chest. The symptoms have occurred several times per year over the last 2 or 3 years and appear to be slowly worsening. She says she has no trouble swallowing liquids. She has a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease, for which she takes a proton pump inhibitor once a day. She says she has had no odynophagia, cough, regurgitation, or weight loss.

How should her symptoms best be evaluated?

DYSPHAGIA CAN BE OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Dysphagia is the subjective sensation of difficulty swallowing solids, liquids, or both. Symptoms can range from the inability to initiate a swallow to the sensation of esophageal obstruction. Other symptoms of esophageal disease may also be present, such as chest pain, heartburn, and regurgitation. There may also be nonesophageal symptoms related to the disease process causing the dysphagia.

Dysphagia can be separated into oropharyngeal and esophageal types.

Interestingly, many patients with symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia in fact have referred symptoms from primary esophageal dysphagia2; many patients with a distal mucosal ring describe a sense of something sticking in the cervical esophagus.

Esophageal dysphagia arises in the mid to distal esophagus or gastric cardia, and as a result, the symptoms are typically retrosternal.1 It can be caused by structural problems such as strictures, rings, webs, extrinsic compression, or a primary esophageal or gastroesophageal neoplasm, or by a primary motility abnormality such as achalasia (Table 1). Eosinophilic esophagitis is now a frequent cause of esophageal dysphagia, especially in white men.3

ESOPHAGOGRAPHY VS ENDOSCOPY IN EVALUATING DYSPHAGIA

Many gastroenterologists recommend endoscopy rather than barium esophagography as the initial examination in patients with dysphagia.4–8 Each test has certain advantages.

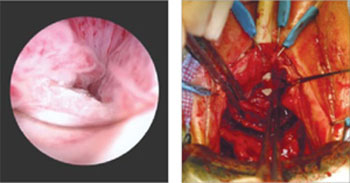

Advantages of endoscopy. Endoscopy is superior to esophagography in detecting milder grades of esophagitis. Further, interventions can be performed endoscopically (eg, dilation, biopsy, attachment of a wireless pH testing probe) that cannot be done during a radiographic procedure, and endoscopy does not expose the patient to radiation.

Advantages of esophagography. Endoscopy cannot detect evidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease unless mucosal injury is present. In dysphagia, the radiologic findings correlate well with endoscopic findings, including the detection of esophageal malignancy and moderate to severe esophagitis. Further, motility disorders can be detected with barium esophagography but not with endoscopy.9,10

Subtle abnormalities, especially rings and strictures, may be missed by narrow-diameter (9.8–10 mm) modern upper-endoscopic equipment. Further, esophagography is noninvasive, costs less, and may be more convenient (it does not require sedation and a chaperone for the patient after sedation). This examination also provides dynamic evaluation of the complex process of swallowing. Causes of dysphagia external to the esophagus can also be determined.

In view of the respective advantages and disadvantages of the two methods, we believe that in most instances barium esophagography should be the initial examination,1,9,11–15 and at our institution most patients presenting with dysphagia undergo barium esophagography before they undergo other examinations.14

OBTAIN A HISTORY BEFORE ORDERING ESOPHAGOGRAPHY

Before a barium examination of the esophagus is done, a focused medical history should be obtained, as it can guide the further workup as well as the esophageal study itself.

An attempt should be made to determine whether the dysphagia is oropharyngeal or if it is esophageal, as the former is generally best initially evaluated by a speech and language pathologist. Generally, the physician who orders the test judges whether the patient has oropharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia. Often, both an oropharyngeal examination, performed by a speech and language pathologist, and an esophageal examination, performed by a radiologist, are ordered.

Rapidly progressive symptoms, especially if accompanied by weight loss, should make one suspect cancer. Chronic symptoms usually point to gastroesophageal reflux disease or a motility disorder such as achalasia. Liquid dysphagia almost always means the patient has a motility disorder such as achalasia.

In view of the possibility of eosinophilic esophagitis, one should ask about food or seasonal allergies, especially in young patients with intermittent difficulty swallowing solids.3

BARIUM ESOPHAGOGRAPHY HAS EIGHT SEPARATE PHASES

Barium esophagography is tailored to the patient with dysphagia on the basis of his or her history. The standard examination is divided into eight separate phases (see below).14 Each phase addresses a specific question or questions concerning the structure and function of the esophagus.

At our institution, the first phase of the examination is determined by the presenting symptoms. If the patient has liquid dysphagia, we start with a timed barium swallow to assess esophageal emptying. If the patient does not have liquid dysphagia, we start with an air-contrast mucosal examination.

The patient must be cooperative and mobile to complete all phases of the examination.

Timed barium swallow to measure esophageal emptying

The timed barium swallow is an objective measure of esophageal emptying.16–18 This technique is essential in the initial evaluation of a patient with liquid dysphagia, a symptom common in patients with severe dysmotility, usually achalasia.

We use this examination in our patients with suspected or confirmed achalasia and to follow up patients who have been treated with pneumatic dilatation, botulinum toxin injection, and Heller myotomy.17,18 In addition, this timed test is an objective measure of emptying in patients who have undergone intervention but whose symptoms have not subjectively improved, and can suggest that further intervention may be required.

Air-contrast or mucosal phase

Although this phase is not as sensitive as endoscopy, it can detect masses, mucosal erosions, ulcers, and—most importantly in our experience—fixed hernias. Patients with a fixed hernia have a foreshortened esophagus, which is important to know about before repairing the hernia. Many esophageal surgeons believe that a foreshortened esophagus precludes a standard Nissen fundoplication and necessitates an esophageal lengthening procedure (ie, Collis gastroplasty with a Nissen fundoplication).14

Motility phase

The third phase examines esophageal motility. With the patient in a semiprone position, low-density barium is given in single swallows, separated by 25 to 30 seconds. The images are recorded on digital media to allow one to review them frame by frame.

The findings on this phase correlate well with those of manometry.19 This portion of the examination also uses impedance monitoring to assess bolus transfer, an aspect not evaluated by manometry.20,21 Impedance monitoring detects changes in resistance to current flow and correlates well with esophagraphic findings regarding bolus transfer.

While many patients with dysphagia also undergo esophageal manometry, the findings from this phase of the esophagographic examination may be the first indication of an esophageal motility disorder. In fact, this portion of the examination shows the distinct advantage of esophagography over endoscopy as the initial test in patients with dysphagia, as endoscopy may not identify patients with achalasia, especially early on.4

Single-contrast (full-column) phase to detect strictures, rings

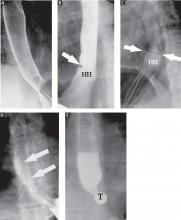

The fourth phase of the esophagographic evaluation is the distended, single-contrast examination (Figure 2B). This is performed in the semiprone position with the patient rapidly drinking thin barium. It is done to detect esophageal strictures, rings, and contour abnormalities caused by extrinsic processes. Subtle abnormalities shown by this technique, including benign strictures and rings, are often not visualized with endoscopy.

Mucosal relief phase

The fifth phase is performed with a collapsed esophagus immediately after the distended, single-contrast phase, where spot films are taken of the barium-coated, collapsed esophagus (Figure 2C). This phase is used to evaluate thickened mucosal folds, a common finding in moderate to severe reflux esophagitis.

Reflux evaluation

Provocative maneuvers are used in the sixth phase to elicit gastroesophageal reflux (Figure 2D). With the patient supine, he or she is asked to roll side to side, do a Valsalva maneuver, and do a straight-leg raise. The patient then sips water in the supine position to assess for reflux (the water siphon test). If reflux is seen, the cause, the height of the reflux, and the duration of reflux retention are recorded.

Solid-bolus phase to assess strictures

In the seventh phase, the patient swallows a 13-mm barium tablet (Figure 2E). This allows one to assess the significance of a ring or stricture and to assess if dysphagia symptoms recur as a result of tablet obstruction. Subtle strictures that were not detected during the prior phases can also be detected using a tablet. If obstruction or impaired passage occurs, the site of obstruction and the presence or absence of symptoms are recorded.

Modified esophagography to assess the oropharynx

The final or eighth phase of barium esophagography is called “modified barium esophagography” or the modified barium swallow. However, it may be the first phase of the examination performed or the only portion of the examination performed, or it may not be performed at all.

Modified barium esophagography is used to define the anatomy of the oropharynx and to assess its function in swallowing.12 It may also guide rehabilitation strategies aimed at eliminating a patient’s swallowing symptoms.

Most patients referred for this test have sustained damage to the central nervous system or structures of the oropharynx, such as stroke or radiation therapy for laryngeal cancer. Many have difficulty in starting to swallow, aspirate when they try to swallow, or both.

The final esophagographic report should document the findings of each phase of the examination (Table 2).

WHAT HAPPENED TO OUR PATIENT?

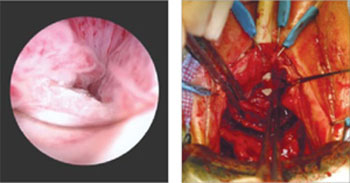

Our patient underwent barium esophagography (Figure 2). A distal mucosal ring that transiently obstructed a 13-mm tablet was found. The patient underwent endoscopy and the ring was dilated. No biopsies were necessary.

- Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Radiologic investigation of dysphagia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990; 154:1157–1163.

- Smith DF, Ott DJ, Gelfand DW, Chen MY. Lower esophageal mucosal ring: correlation of referred symptoms with radiographic findings using a marshmallow bolus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998; 171:1361–1365.

- Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007; 133:1342–1363.

- Spechler SJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology 1999; 117:229–233.

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Appropriate use of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 52:831–837.

- Esfandyari T, Potter JW, Vaezi MF. Dysphagia: a cost analysis of the diagnostic approach. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2733–2737.

- Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA, Patel RS, et al. The yield and the predictors of esophageal pathology when upper endoscopy is used for the initial evaluation of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61:804–808.

- Standards of Practice Committee. Role of endoscopy in the management of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66:219–224.

- Halpert RD, Feczko PJ, Spickler EM, Ackerman LV. Radiological assessment of dysphagia with endoscopic correlation. Radiology 1985; 157:599–602.

- Ott DJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Radiol Clin North Am 1994; 32:1147–1166.

- Ekberg O, Pokieser P. Radiologic evaluation of the dysphagic patient. Eur Radiol 1997; 7:1285–1295.

- Logemann JA. Role of the modified barium swallow in management of patients with dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 116:335–338.

- Baker ME, Rice TW. Radiologic evaluation of the esophagus: methods and value in motility disorders and GERD. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 13:201–225.

- Baker ME, Einstein DM, Herts BR, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: integrating the barium esophagram before and after antire-flux surgery. Radiology 2007; 243:329–339.

- Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Barium esophagography: a study for all seasons. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:11–25.

- deOliveira JM, Birgisson S, Doinoff C, et al. Timed barium swallow: a simple technique for evaluating esophageal emptying in patients with achalasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 169:473–479.

- Kostic SV, Rice TW, Baker ME, et al. Time barium esophagram: a simple physiologic assessment for achalasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 120:935–943.

- Vaezi MF, Baker ME, Achkar E, Richter JE. Timed barium oesophagram: better predictor of long term success after pneumatic dilation in achalasia than symptom assessment. Gut 2002; 50:765–770.

- Hewson EG, Ott DJ, Dalton CB, Chen YM, Wu WC, Richter JE. Manometry and radiology. Complementary studies in the assessment of esophageal motility disorders. Gastroenterology 1990; 98:626–632.

- Imam H, Shay S, Ali A, Baker M. Bolus transit patterns in healthy subjects: a study using simultaneous impedance monitoring, video-esophagram, and esophageal manometry. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005;G1000–G1006.

- Imam H, Baker M, Shay S. Simultaneous barium esophagram, impedance monitoring and manometry in patients with dysphagia due to a tight fundoplication [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:A-639.

A 55-year-old woman presents with an intermittent sensation of food getting stuck in her mid to lower chest. The symptoms have occurred several times per year over the last 2 or 3 years and appear to be slowly worsening. She says she has no trouble swallowing liquids. She has a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease, for which she takes a proton pump inhibitor once a day. She says she has had no odynophagia, cough, regurgitation, or weight loss.

How should her symptoms best be evaluated?

DYSPHAGIA CAN BE OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Dysphagia is the subjective sensation of difficulty swallowing solids, liquids, or both. Symptoms can range from the inability to initiate a swallow to the sensation of esophageal obstruction. Other symptoms of esophageal disease may also be present, such as chest pain, heartburn, and regurgitation. There may also be nonesophageal symptoms related to the disease process causing the dysphagia.

Dysphagia can be separated into oropharyngeal and esophageal types.

Interestingly, many patients with symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia in fact have referred symptoms from primary esophageal dysphagia2; many patients with a distal mucosal ring describe a sense of something sticking in the cervical esophagus.

Esophageal dysphagia arises in the mid to distal esophagus or gastric cardia, and as a result, the symptoms are typically retrosternal.1 It can be caused by structural problems such as strictures, rings, webs, extrinsic compression, or a primary esophageal or gastroesophageal neoplasm, or by a primary motility abnormality such as achalasia (Table 1). Eosinophilic esophagitis is now a frequent cause of esophageal dysphagia, especially in white men.3

ESOPHAGOGRAPHY VS ENDOSCOPY IN EVALUATING DYSPHAGIA

Many gastroenterologists recommend endoscopy rather than barium esophagography as the initial examination in patients with dysphagia.4–8 Each test has certain advantages.

Advantages of endoscopy. Endoscopy is superior to esophagography in detecting milder grades of esophagitis. Further, interventions can be performed endoscopically (eg, dilation, biopsy, attachment of a wireless pH testing probe) that cannot be done during a radiographic procedure, and endoscopy does not expose the patient to radiation.

Advantages of esophagography. Endoscopy cannot detect evidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease unless mucosal injury is present. In dysphagia, the radiologic findings correlate well with endoscopic findings, including the detection of esophageal malignancy and moderate to severe esophagitis. Further, motility disorders can be detected with barium esophagography but not with endoscopy.9,10

Subtle abnormalities, especially rings and strictures, may be missed by narrow-diameter (9.8–10 mm) modern upper-endoscopic equipment. Further, esophagography is noninvasive, costs less, and may be more convenient (it does not require sedation and a chaperone for the patient after sedation). This examination also provides dynamic evaluation of the complex process of swallowing. Causes of dysphagia external to the esophagus can also be determined.

In view of the respective advantages and disadvantages of the two methods, we believe that in most instances barium esophagography should be the initial examination,1,9,11–15 and at our institution most patients presenting with dysphagia undergo barium esophagography before they undergo other examinations.14

OBTAIN A HISTORY BEFORE ORDERING ESOPHAGOGRAPHY

Before a barium examination of the esophagus is done, a focused medical history should be obtained, as it can guide the further workup as well as the esophageal study itself.

An attempt should be made to determine whether the dysphagia is oropharyngeal or if it is esophageal, as the former is generally best initially evaluated by a speech and language pathologist. Generally, the physician who orders the test judges whether the patient has oropharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia. Often, both an oropharyngeal examination, performed by a speech and language pathologist, and an esophageal examination, performed by a radiologist, are ordered.

Rapidly progressive symptoms, especially if accompanied by weight loss, should make one suspect cancer. Chronic symptoms usually point to gastroesophageal reflux disease or a motility disorder such as achalasia. Liquid dysphagia almost always means the patient has a motility disorder such as achalasia.

In view of the possibility of eosinophilic esophagitis, one should ask about food or seasonal allergies, especially in young patients with intermittent difficulty swallowing solids.3

BARIUM ESOPHAGOGRAPHY HAS EIGHT SEPARATE PHASES

Barium esophagography is tailored to the patient with dysphagia on the basis of his or her history. The standard examination is divided into eight separate phases (see below).14 Each phase addresses a specific question or questions concerning the structure and function of the esophagus.

At our institution, the first phase of the examination is determined by the presenting symptoms. If the patient has liquid dysphagia, we start with a timed barium swallow to assess esophageal emptying. If the patient does not have liquid dysphagia, we start with an air-contrast mucosal examination.

The patient must be cooperative and mobile to complete all phases of the examination.

Timed barium swallow to measure esophageal emptying

The timed barium swallow is an objective measure of esophageal emptying.16–18 This technique is essential in the initial evaluation of a patient with liquid dysphagia, a symptom common in patients with severe dysmotility, usually achalasia.

We use this examination in our patients with suspected or confirmed achalasia and to follow up patients who have been treated with pneumatic dilatation, botulinum toxin injection, and Heller myotomy.17,18 In addition, this timed test is an objective measure of emptying in patients who have undergone intervention but whose symptoms have not subjectively improved, and can suggest that further intervention may be required.

Air-contrast or mucosal phase

Although this phase is not as sensitive as endoscopy, it can detect masses, mucosal erosions, ulcers, and—most importantly in our experience—fixed hernias. Patients with a fixed hernia have a foreshortened esophagus, which is important to know about before repairing the hernia. Many esophageal surgeons believe that a foreshortened esophagus precludes a standard Nissen fundoplication and necessitates an esophageal lengthening procedure (ie, Collis gastroplasty with a Nissen fundoplication).14

Motility phase

The third phase examines esophageal motility. With the patient in a semiprone position, low-density barium is given in single swallows, separated by 25 to 30 seconds. The images are recorded on digital media to allow one to review them frame by frame.

The findings on this phase correlate well with those of manometry.19 This portion of the examination also uses impedance monitoring to assess bolus transfer, an aspect not evaluated by manometry.20,21 Impedance monitoring detects changes in resistance to current flow and correlates well with esophagraphic findings regarding bolus transfer.

While many patients with dysphagia also undergo esophageal manometry, the findings from this phase of the esophagographic examination may be the first indication of an esophageal motility disorder. In fact, this portion of the examination shows the distinct advantage of esophagography over endoscopy as the initial test in patients with dysphagia, as endoscopy may not identify patients with achalasia, especially early on.4

Single-contrast (full-column) phase to detect strictures, rings

The fourth phase of the esophagographic evaluation is the distended, single-contrast examination (Figure 2B). This is performed in the semiprone position with the patient rapidly drinking thin barium. It is done to detect esophageal strictures, rings, and contour abnormalities caused by extrinsic processes. Subtle abnormalities shown by this technique, including benign strictures and rings, are often not visualized with endoscopy.

Mucosal relief phase

The fifth phase is performed with a collapsed esophagus immediately after the distended, single-contrast phase, where spot films are taken of the barium-coated, collapsed esophagus (Figure 2C). This phase is used to evaluate thickened mucosal folds, a common finding in moderate to severe reflux esophagitis.

Reflux evaluation

Provocative maneuvers are used in the sixth phase to elicit gastroesophageal reflux (Figure 2D). With the patient supine, he or she is asked to roll side to side, do a Valsalva maneuver, and do a straight-leg raise. The patient then sips water in the supine position to assess for reflux (the water siphon test). If reflux is seen, the cause, the height of the reflux, and the duration of reflux retention are recorded.

Solid-bolus phase to assess strictures

In the seventh phase, the patient swallows a 13-mm barium tablet (Figure 2E). This allows one to assess the significance of a ring or stricture and to assess if dysphagia symptoms recur as a result of tablet obstruction. Subtle strictures that were not detected during the prior phases can also be detected using a tablet. If obstruction or impaired passage occurs, the site of obstruction and the presence or absence of symptoms are recorded.

Modified esophagography to assess the oropharynx

The final or eighth phase of barium esophagography is called “modified barium esophagography” or the modified barium swallow. However, it may be the first phase of the examination performed or the only portion of the examination performed, or it may not be performed at all.

Modified barium esophagography is used to define the anatomy of the oropharynx and to assess its function in swallowing.12 It may also guide rehabilitation strategies aimed at eliminating a patient’s swallowing symptoms.

Most patients referred for this test have sustained damage to the central nervous system or structures of the oropharynx, such as stroke or radiation therapy for laryngeal cancer. Many have difficulty in starting to swallow, aspirate when they try to swallow, or both.

The final esophagographic report should document the findings of each phase of the examination (Table 2).

WHAT HAPPENED TO OUR PATIENT?

Our patient underwent barium esophagography (Figure 2). A distal mucosal ring that transiently obstructed a 13-mm tablet was found. The patient underwent endoscopy and the ring was dilated. No biopsies were necessary.

A 55-year-old woman presents with an intermittent sensation of food getting stuck in her mid to lower chest. The symptoms have occurred several times per year over the last 2 or 3 years and appear to be slowly worsening. She says she has no trouble swallowing liquids. She has a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease, for which she takes a proton pump inhibitor once a day. She says she has had no odynophagia, cough, regurgitation, or weight loss.

How should her symptoms best be evaluated?

DYSPHAGIA CAN BE OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Dysphagia is the subjective sensation of difficulty swallowing solids, liquids, or both. Symptoms can range from the inability to initiate a swallow to the sensation of esophageal obstruction. Other symptoms of esophageal disease may also be present, such as chest pain, heartburn, and regurgitation. There may also be nonesophageal symptoms related to the disease process causing the dysphagia.

Dysphagia can be separated into oropharyngeal and esophageal types.

Interestingly, many patients with symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia in fact have referred symptoms from primary esophageal dysphagia2; many patients with a distal mucosal ring describe a sense of something sticking in the cervical esophagus.

Esophageal dysphagia arises in the mid to distal esophagus or gastric cardia, and as a result, the symptoms are typically retrosternal.1 It can be caused by structural problems such as strictures, rings, webs, extrinsic compression, or a primary esophageal or gastroesophageal neoplasm, or by a primary motility abnormality such as achalasia (Table 1). Eosinophilic esophagitis is now a frequent cause of esophageal dysphagia, especially in white men.3

ESOPHAGOGRAPHY VS ENDOSCOPY IN EVALUATING DYSPHAGIA

Many gastroenterologists recommend endoscopy rather than barium esophagography as the initial examination in patients with dysphagia.4–8 Each test has certain advantages.

Advantages of endoscopy. Endoscopy is superior to esophagography in detecting milder grades of esophagitis. Further, interventions can be performed endoscopically (eg, dilation, biopsy, attachment of a wireless pH testing probe) that cannot be done during a radiographic procedure, and endoscopy does not expose the patient to radiation.

Advantages of esophagography. Endoscopy cannot detect evidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease unless mucosal injury is present. In dysphagia, the radiologic findings correlate well with endoscopic findings, including the detection of esophageal malignancy and moderate to severe esophagitis. Further, motility disorders can be detected with barium esophagography but not with endoscopy.9,10

Subtle abnormalities, especially rings and strictures, may be missed by narrow-diameter (9.8–10 mm) modern upper-endoscopic equipment. Further, esophagography is noninvasive, costs less, and may be more convenient (it does not require sedation and a chaperone for the patient after sedation). This examination also provides dynamic evaluation of the complex process of swallowing. Causes of dysphagia external to the esophagus can also be determined.

In view of the respective advantages and disadvantages of the two methods, we believe that in most instances barium esophagography should be the initial examination,1,9,11–15 and at our institution most patients presenting with dysphagia undergo barium esophagography before they undergo other examinations.14

OBTAIN A HISTORY BEFORE ORDERING ESOPHAGOGRAPHY

Before a barium examination of the esophagus is done, a focused medical history should be obtained, as it can guide the further workup as well as the esophageal study itself.

An attempt should be made to determine whether the dysphagia is oropharyngeal or if it is esophageal, as the former is generally best initially evaluated by a speech and language pathologist. Generally, the physician who orders the test judges whether the patient has oropharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia. Often, both an oropharyngeal examination, performed by a speech and language pathologist, and an esophageal examination, performed by a radiologist, are ordered.

Rapidly progressive symptoms, especially if accompanied by weight loss, should make one suspect cancer. Chronic symptoms usually point to gastroesophageal reflux disease or a motility disorder such as achalasia. Liquid dysphagia almost always means the patient has a motility disorder such as achalasia.

In view of the possibility of eosinophilic esophagitis, one should ask about food or seasonal allergies, especially in young patients with intermittent difficulty swallowing solids.3

BARIUM ESOPHAGOGRAPHY HAS EIGHT SEPARATE PHASES

Barium esophagography is tailored to the patient with dysphagia on the basis of his or her history. The standard examination is divided into eight separate phases (see below).14 Each phase addresses a specific question or questions concerning the structure and function of the esophagus.

At our institution, the first phase of the examination is determined by the presenting symptoms. If the patient has liquid dysphagia, we start with a timed barium swallow to assess esophageal emptying. If the patient does not have liquid dysphagia, we start with an air-contrast mucosal examination.

The patient must be cooperative and mobile to complete all phases of the examination.

Timed barium swallow to measure esophageal emptying

The timed barium swallow is an objective measure of esophageal emptying.16–18 This technique is essential in the initial evaluation of a patient with liquid dysphagia, a symptom common in patients with severe dysmotility, usually achalasia.

We use this examination in our patients with suspected or confirmed achalasia and to follow up patients who have been treated with pneumatic dilatation, botulinum toxin injection, and Heller myotomy.17,18 In addition, this timed test is an objective measure of emptying in patients who have undergone intervention but whose symptoms have not subjectively improved, and can suggest that further intervention may be required.

Air-contrast or mucosal phase

Although this phase is not as sensitive as endoscopy, it can detect masses, mucosal erosions, ulcers, and—most importantly in our experience—fixed hernias. Patients with a fixed hernia have a foreshortened esophagus, which is important to know about before repairing the hernia. Many esophageal surgeons believe that a foreshortened esophagus precludes a standard Nissen fundoplication and necessitates an esophageal lengthening procedure (ie, Collis gastroplasty with a Nissen fundoplication).14

Motility phase

The third phase examines esophageal motility. With the patient in a semiprone position, low-density barium is given in single swallows, separated by 25 to 30 seconds. The images are recorded on digital media to allow one to review them frame by frame.

The findings on this phase correlate well with those of manometry.19 This portion of the examination also uses impedance monitoring to assess bolus transfer, an aspect not evaluated by manometry.20,21 Impedance monitoring detects changes in resistance to current flow and correlates well with esophagraphic findings regarding bolus transfer.

While many patients with dysphagia also undergo esophageal manometry, the findings from this phase of the esophagographic examination may be the first indication of an esophageal motility disorder. In fact, this portion of the examination shows the distinct advantage of esophagography over endoscopy as the initial test in patients with dysphagia, as endoscopy may not identify patients with achalasia, especially early on.4

Single-contrast (full-column) phase to detect strictures, rings

The fourth phase of the esophagographic evaluation is the distended, single-contrast examination (Figure 2B). This is performed in the semiprone position with the patient rapidly drinking thin barium. It is done to detect esophageal strictures, rings, and contour abnormalities caused by extrinsic processes. Subtle abnormalities shown by this technique, including benign strictures and rings, are often not visualized with endoscopy.

Mucosal relief phase

The fifth phase is performed with a collapsed esophagus immediately after the distended, single-contrast phase, where spot films are taken of the barium-coated, collapsed esophagus (Figure 2C). This phase is used to evaluate thickened mucosal folds, a common finding in moderate to severe reflux esophagitis.

Reflux evaluation

Provocative maneuvers are used in the sixth phase to elicit gastroesophageal reflux (Figure 2D). With the patient supine, he or she is asked to roll side to side, do a Valsalva maneuver, and do a straight-leg raise. The patient then sips water in the supine position to assess for reflux (the water siphon test). If reflux is seen, the cause, the height of the reflux, and the duration of reflux retention are recorded.

Solid-bolus phase to assess strictures

In the seventh phase, the patient swallows a 13-mm barium tablet (Figure 2E). This allows one to assess the significance of a ring or stricture and to assess if dysphagia symptoms recur as a result of tablet obstruction. Subtle strictures that were not detected during the prior phases can also be detected using a tablet. If obstruction or impaired passage occurs, the site of obstruction and the presence or absence of symptoms are recorded.

Modified esophagography to assess the oropharynx

The final or eighth phase of barium esophagography is called “modified barium esophagography” or the modified barium swallow. However, it may be the first phase of the examination performed or the only portion of the examination performed, or it may not be performed at all.

Modified barium esophagography is used to define the anatomy of the oropharynx and to assess its function in swallowing.12 It may also guide rehabilitation strategies aimed at eliminating a patient’s swallowing symptoms.

Most patients referred for this test have sustained damage to the central nervous system or structures of the oropharynx, such as stroke or radiation therapy for laryngeal cancer. Many have difficulty in starting to swallow, aspirate when they try to swallow, or both.

The final esophagographic report should document the findings of each phase of the examination (Table 2).

WHAT HAPPENED TO OUR PATIENT?

Our patient underwent barium esophagography (Figure 2). A distal mucosal ring that transiently obstructed a 13-mm tablet was found. The patient underwent endoscopy and the ring was dilated. No biopsies were necessary.

- Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Radiologic investigation of dysphagia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990; 154:1157–1163.

- Smith DF, Ott DJ, Gelfand DW, Chen MY. Lower esophageal mucosal ring: correlation of referred symptoms with radiographic findings using a marshmallow bolus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998; 171:1361–1365.

- Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007; 133:1342–1363.

- Spechler SJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology 1999; 117:229–233.

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Appropriate use of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 52:831–837.

- Esfandyari T, Potter JW, Vaezi MF. Dysphagia: a cost analysis of the diagnostic approach. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2733–2737.

- Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA, Patel RS, et al. The yield and the predictors of esophageal pathology when upper endoscopy is used for the initial evaluation of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61:804–808.

- Standards of Practice Committee. Role of endoscopy in the management of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66:219–224.

- Halpert RD, Feczko PJ, Spickler EM, Ackerman LV. Radiological assessment of dysphagia with endoscopic correlation. Radiology 1985; 157:599–602.

- Ott DJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Radiol Clin North Am 1994; 32:1147–1166.

- Ekberg O, Pokieser P. Radiologic evaluation of the dysphagic patient. Eur Radiol 1997; 7:1285–1295.

- Logemann JA. Role of the modified barium swallow in management of patients with dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 116:335–338.

- Baker ME, Rice TW. Radiologic evaluation of the esophagus: methods and value in motility disorders and GERD. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 13:201–225.

- Baker ME, Einstein DM, Herts BR, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: integrating the barium esophagram before and after antire-flux surgery. Radiology 2007; 243:329–339.

- Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Barium esophagography: a study for all seasons. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:11–25.

- deOliveira JM, Birgisson S, Doinoff C, et al. Timed barium swallow: a simple technique for evaluating esophageal emptying in patients with achalasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 169:473–479.

- Kostic SV, Rice TW, Baker ME, et al. Time barium esophagram: a simple physiologic assessment for achalasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 120:935–943.

- Vaezi MF, Baker ME, Achkar E, Richter JE. Timed barium oesophagram: better predictor of long term success after pneumatic dilation in achalasia than symptom assessment. Gut 2002; 50:765–770.

- Hewson EG, Ott DJ, Dalton CB, Chen YM, Wu WC, Richter JE. Manometry and radiology. Complementary studies in the assessment of esophageal motility disorders. Gastroenterology 1990; 98:626–632.

- Imam H, Shay S, Ali A, Baker M. Bolus transit patterns in healthy subjects: a study using simultaneous impedance monitoring, video-esophagram, and esophageal manometry. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005;G1000–G1006.

- Imam H, Baker M, Shay S. Simultaneous barium esophagram, impedance monitoring and manometry in patients with dysphagia due to a tight fundoplication [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:A-639.

- Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Radiologic investigation of dysphagia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990; 154:1157–1163.

- Smith DF, Ott DJ, Gelfand DW, Chen MY. Lower esophageal mucosal ring: correlation of referred symptoms with radiographic findings using a marshmallow bolus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998; 171:1361–1365.

- Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007; 133:1342–1363.

- Spechler SJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology 1999; 117:229–233.

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Appropriate use of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 52:831–837.

- Esfandyari T, Potter JW, Vaezi MF. Dysphagia: a cost analysis of the diagnostic approach. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2733–2737.

- Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA, Patel RS, et al. The yield and the predictors of esophageal pathology when upper endoscopy is used for the initial evaluation of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61:804–808.

- Standards of Practice Committee. Role of endoscopy in the management of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66:219–224.

- Halpert RD, Feczko PJ, Spickler EM, Ackerman LV. Radiological assessment of dysphagia with endoscopic correlation. Radiology 1985; 157:599–602.

- Ott DJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Radiol Clin North Am 1994; 32:1147–1166.

- Ekberg O, Pokieser P. Radiologic evaluation of the dysphagic patient. Eur Radiol 1997; 7:1285–1295.

- Logemann JA. Role of the modified barium swallow in management of patients with dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 116:335–338.

- Baker ME, Rice TW. Radiologic evaluation of the esophagus: methods and value in motility disorders and GERD. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 13:201–225.

- Baker ME, Einstein DM, Herts BR, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: integrating the barium esophagram before and after antire-flux surgery. Radiology 2007; 243:329–339.

- Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Barium esophagography: a study for all seasons. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:11–25.

- deOliveira JM, Birgisson S, Doinoff C, et al. Timed barium swallow: a simple technique for evaluating esophageal emptying in patients with achalasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 169:473–479.

- Kostic SV, Rice TW, Baker ME, et al. Time barium esophagram: a simple physiologic assessment for achalasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 120:935–943.

- Vaezi MF, Baker ME, Achkar E, Richter JE. Timed barium oesophagram: better predictor of long term success after pneumatic dilation in achalasia than symptom assessment. Gut 2002; 50:765–770.

- Hewson EG, Ott DJ, Dalton CB, Chen YM, Wu WC, Richter JE. Manometry and radiology. Complementary studies in the assessment of esophageal motility disorders. Gastroenterology 1990; 98:626–632.

- Imam H, Shay S, Ali A, Baker M. Bolus transit patterns in healthy subjects: a study using simultaneous impedance monitoring, video-esophagram, and esophageal manometry. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005;G1000–G1006.

- Imam H, Baker M, Shay S. Simultaneous barium esophagram, impedance monitoring and manometry in patients with dysphagia due to a tight fundoplication [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:A-639.

KEY POINTS

- Dysphagia can be due to problems in the oropharynx and cervical esophagus or in the distal esophagus.

- Radiologic evaluation of dysphagia has distinct advantages over endoscopy, including its ability to diagnose both structural changes and motility disorders.

- A barium evaluation can include a modified barium-swallowing study to evaluate the oropharynx, barium esophagography to evaluate the esophagus, and a timed study to evaluate esophageal emptying.

- Often, the true cause of dysphagia is best approached with a combination of radiographic and endoscopic studies.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: Emerging concepts of pathogenesis and new treatments

A 25-year-old married white woman presented to a clinic because of pelvic pain. A computed tomographic scan of her abdomen and pelvis without intravenous contrast showed two definite cysts in the right kidney (the larger measuring 2.5 cm) and a 1.5-cm cyst in the left kidney. It also showed several smaller (< 1 cm) areas of low density in both kidneys that suggested cysts. Renal ultrasonography also showed two cysts in the left kidney and one in the right kidney. The kidneys were normal-sized—the right one measured 12.5 cm and the left one 12.7 cm.

She had no family history of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), and renal ultrasonography of her parents showed no cystic disease. She had no history of headache or heart murmur, and her blood pressure was normal. Her kidneys were barely palpable, her liver was not enlarged, and she had no cardiac murmur or click. She was not taking any medications. Her serum creatinine level was 0.7 mg/dL, hemoglobin 14.0 g/dL, and urinalysis normal.

Does this patient have ADPKD? Based on the studies done so far, would genetic testing be useful? If the genetic analysis does show a mutation, what additional information can be derived from the location of that mutation? Can she do anything to improve her prognosis?

ADPKD ACCOUNTS FOR ABOUT 3% OF END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE

ADPKD is the most common of all inherited renal diseases, with 600,000 to 700,000 cases in the United States and about 12.5 million cases worldwide. About 5,000 to 6,000 new cases are diagnosed yearly in the United States, about 40% of them by age 45. Typically, patients with ADPKD have a family history of the disease, but about 5% to 10% do not. In about 50% of cases, ADPKD progresses to end-stage renal disease by age 60, and it accounts for about 3% of cases of end-stage renal disease in the United States.1

CYSTS IN KIDNEYS AND OTHER ORGANS, AND NONCYSTIC FEATURES

In ADPKD, cysts in the kidneys increase in number and size over time, ultimately destroying normal renal tissue. However, renal function remains steady over many years until the kidneys have approximately quadrupled in volume to 1,500 cm3 (normal combined kidney volume is about 250 to 400 cm3), which defines a tipping point beyond which renal function can rapidly decline.2,3 Ultimately, the patient will need renal replacement therapy, ie, dialysis or renal transplantation.

The cysts (kidney and liver) cause discomfort and pain by putting pressure on the abdominal wall, flanks, and back, by impinging on neighboring organs, by bleeding into the cysts, and by the development of kidney stones or infected cysts (which are uncommon, though urinary tract infections themselves are more frequent). Kidney stones occur in about 20% of patients with ADPKD, and uric acid stones are almost as common as calcium oxalate stones. Compression of the iliac vein and inferior vena cava with possible thrombus formation and pulmonary embolism can be caused by enormous enlargement of the cystic kidneys, particularly the right.4 Interestingly, the patients at greatest risk of pulmonary embolism after renal transplantation are those with ADPKD.5

Cysts can also develop in other organs. Liver cysts develop in about 80% of patients. Usually, the cysts do not affect liver function, but because they are substantially estrogen-dependent they can be more of a clinical problem in women. About 10% of patients have cysts in the pancreas, but these are functionally insignificant. Other locations of cysts include the spleen, arachnoid membranes, and seminal vesicles in men.

Intracranial aneurysms are a key noncystic feature, and these are strongly influenced by family history. A patient with ADPKD who has a family member with ADPKD as well as an intracranial aneurysm or subarachnoid hemorrhage has about a 20% chance of having an intracranial aneurysm. A key clinical warning is a “sentinel” or “thunderclap” headache, which patients typically rate as at least a 10 on a scale of 10 in severity. In a patient with ADPKD, this type of headache can signal a leaking aneurysm causing irritation and edema of the surrounding brain tissue that temporarily tamponades the bleeding before the aneurysm actually ruptures. This is a critical period when a patient should immediately obtain emergency care.

Cardiac valve abnormalities occur in about one-third of patients. Most common is mitral valve prolapse, which is usually mild. Abnormalities can also occur in the aortic valve and the left ventricular outflow tract.

Hernias are the third general noncystic feature of ADPKD. Patients with ADPKD have an increased prevalence of umbilical, hiatal, and inguinal hernias, as well as diverticulae of the colon.

DOES THIS PATIENT HAVE ADPKD?

The Ravine ultrasonographic criteria for the diagnosis of ADPKD are based on the patient’s age, family history, and number of cysts (Table 1).6,7 Alternatively, Torres (Vincent E. Torres, personal communication, March 2008) recommends that, in the absence of a family history of ADPKD or other findings to suggest other cystic disease, the diagnosis of ADPKD can be made if the patient has a total of at least 20 renal cysts.

Our patient had only three definite cysts, was 25 years old, and had no family history of ADPKD and so did not technically meet the Ravine criteria of five cysts at this age, or the Torres criteria, for having ADPKD. Nevertheless, because she was concerned about overt disease possibly developing later and about passing on a genetic defect to her future offspring, she decided to undergo genetic testing.

CLINICAL GENETICS OF ADPKD: TWO MAJOR TYPES

There are two major genetic forms of ADPKD, caused by mutations in the genes PKD1 and PKD2.

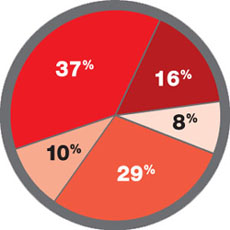

PKD1 has been mapped to the short arm of the 16th chromosome. Its gene product is polycystin 1. Mutations in PKD1 account for about 85% of all cases of polycystic kidney disease. The cysts appear when patients are in their 20s, and the disease progresses relatively rapidly, so that most patients enter end-stage renal disease when they are in their 50s.

PKD2 has been mapped to the long arm of the fourth chromosome. Its product is polycystin 2. PKD2 mutations account for about 15% of all cases of ADPKD, and the disease progresses more slowly, usually with end-stage disease developing when the patients usually are in their 70s.

Screening for mutations by direct DNA sequencing in ADPKD

Genetic testing for PKD1 and PKD2 mutations is available (www.athenadiagnostics.com).8 The Human Gene Mutation Database lists at least 270 different PKD1 mutations and 70 different PKD2 mutations.8 Most are unique to a single family.

Our patient was tested for mutations of the PKD1 and PKD2 genes by polymerase chain reaction amplification and direct DNA sequencing. She was found to possess a DNA sequence variant at a nucleotide position in the PKD1 gene previously reported as a disease-associated mutation. She is therefore likely to be affected with or predisposed to developing ADPKD.

Furthermore, the position of her mutation means she has a worse prognosis. Rossetti et al,9 in a study of 324 PKD1 patients, found that only 19% of those who had mutations in the 5′ region of the gene (ie, at positions below 7,812) still had adequate renal function at 60 years of age, compared with 40% of those with mutations in the 3′ region (P = .025).

Other risk factors for more rapid kidney failure in ADPKD include male sex, onset of hypertension before age 35, gross hematuria before age 30 in men, and, in women, having had three or more pregnancies.

THE ‘TWO-HIT’ HYPOTHESIS

The time of onset and the rate of progression of ADPKD can vary from patient to patient, even in the same family. Besides the factors mentioned above, another reason may be that second mutations (“second hits”) have to occur before the cysts develop.

The first mutation exists in all the kidney tubular cells and is the germline mutation in the PKD gene inherited from the affected parent. This is necessary but not sufficient for cyst formation.

The second hit is a somatic mutation in an individual tubular cell that inactivates to varying degrees the unaffected gene from the normal parent. It is these second hits that allow abnormal focal (monoclonal) proliferation of renal tubular cells and cyst formation (reviewed by Arnaout10 and by Pei11). There is no way to predict these second hits, and their identity is unknown.

Other genetic variations may occur, such as transheterozygous mutations, in which a person may have a mutation of PKD1 as well as PKD2.

Germline mutations of PKD1 or PKD2 combined with somatic mutations of the normal paired chromosome depress levels of their normal gene products (polycystin 1 and polycystin 2) to the point that cysts develop.

The timing and frequency of these second hits blur the distinction between the time course for the progression of PKD1 and PKD2 disease, and can accelerate the course of both.

BASIC RESEARCH POINTS THE WAY TO TREATMENTS FOR ADPKD

Polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 are the normal gene products of the genes which, when mutated, are responsible for PKD1 and PKD2, respectively. Research into the structure and function of the polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 proteins—and what goes wrong when they are not produced in sufficient quantity or accurately—is pointing the way to possible treatments for ADPKD.

When the polycystins are not functioning, as in ADPKD, these proliferative pathways are unopposed. However, proliferation can be countered in other ways. One of the prime movers of cell proliferation, acting through adenylyl cyclase and cAMP, is vasopressin. In genetically produced polycystic animals, two antagonists of the vasopressin V2 receptor (VPV2R), OPC31260 and OPC41061 (tolvaptan), decreased cAMP and ERK, prevented or reduced renal cysts, and preserved renal function.15,16 Not surprisingly, simply increasing water intake decreases vasopressin production and the development of polycystic kidney disease in rats.17 Definitive proof of the role of vasopressin in causing cyst formation was achieved by crossing PCK rats (genetically destined to develop polycystic kidneys) with Brattleboro rats (totally lacking vasopressin) in order to generate rats with polycystic kidneys and varying amounts of vasopressin.18 PCK animals with no vasopressin had virtually no cAMP or renal cysts, whereas PCK animals with increasing amounts of vasopressin had progressively larger kidneys with more numerous cysts. Administration of synthetic vasopressin to PCK rats that totally lacked vasopressin re-created the full cystic disease.

Normally, cAMP is broken down by phosphodiesterases. Caffeine and methylxanthine products such as theophylline interfere with phosphodiesterase activity, raise cAMP in epithelial cell cultures from patients with ADPKD,19 and increase cyst formation in canine kidney cell cultures.20 One could infer that caffeine-containing drinks and foods would be undesirable for ADPKD patients.

The absence of polycystin permits excessive kinase activity in the mTOR pathway and the development of renal cysts.14 The mTOR system can be blocked by rapamycin (sirolimus, Rapamune). Wahl et al21 found that inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin slows PKD progression in rats. In a prospective study in humans, rapamycin reduced polycystic liver volumes in ADPKD renal transplant recipients.22

Rapamycin, however, can have significant side effects that include hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, leukopenia, oral ulcers, impaired wound healing, proteinuria, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, interstitial pneumonia, infection, and venous thrombosis. Many of these appear to be dose-related and can generally be reversed by stopping or reducing the dose. However, this drug is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of ADPKD, and we absolutely do not advocate using it “off-label.”

What does this mean for our patient?

Although these results were derived primarily from animal experiments, they do provide a substantial rationale for advising our patient to:

Drink approximately 3 L of water throughout the day right up to bedtime in order to suppress vasopressin secretion and the stimulation of cAMP. This should be done under a doctor’s direction and with regular monitoring.15,17,18,23

Avoid caffeine and methylxanthines because they block phosphodiesterase, thereby leaving more cAMP to stimulate cyst formation.19,20

Follow a low-sodium diet (< 2,300 mg/day), which, while helping to control hypertension and kidney stone formation, may also help to maintain smaller cysts and kidneys. Keith et al,24 in an experiment in rats, found that the greater the sodium content of the rats’ diet, the greater the cyst sizes and kidney volumes by the end of 3 months.

Consider participating in a study. Several clinical treatment studies in ADPKD are currently enrolling patients who qualify:

- The Halt Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease (HALT PKD) study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is comparing the combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) vs an ACE inhibitor plus placebo. Participating centers are Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Cleveland Clinic, Emory University, Mayo Clinic, Tufts-New England Medical Center, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, and University of Kansas Medical Center. This study involves approximately 1,020 patients nationwide.

- The Tolvaptan Efficacy and Safety in Management of Polycystic Disease and its Outcomes (TEMPO) study plans to enroll approximately 1,500 patients.

- Rapamycin is being studied in a pilot study at Cleveland Clinic and in another study in Zurich, Switzerland.

- A study of everolimus, a shorter-acting mTOR inhibitor, is beginning.

- A study of somatostatin is under way in Italy.

HYPERTENSION AND ADPKD

Uncontrolled hypertension is a key factor in the rate of progression of kidney disease in general and ADPKD in particular. It needs to be effectively treated. The target blood pressure should be in the range of 110 to 130 mm Hg systolic and 70 to 80 mm Hg diastolic.

Hypertension develops at least in part because the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is up-regulated in ADPKD due to renal cysts compressing and stretching blood vessels.25 Synthesis of immunoreactive renin, which normally takes place in the juxtaglomerular apparatus, shifts to the walls of the arterioles. There is also ectopic renin synthesis in the epithelium of dilated tubules and cysts. Greater renin production causes increases in angiotensin II and vasoconstriction, in aldosterone and sodium retention, and both angiotensin II and aldosterone can cause fibrosis and mitogenesis, which enhance cyst formation.

ACE inhibitors partially reverse the decrease in renal blood flow, renal vascular resistance, and the increase in filtration fraction. However, because some angiotensin II is also produced by an ACE-independent pathway via a chymase-like enzyme, ARBs may have a broader role in treating ADPKD.

In experimental rats with polycystic kidney disease, Keith et al24 found that blood pressure, kidney weight, plasma creatinine, and histology score (reflecting the volume of cysts as a percentage of the cortex) were all lower in animals receiving the ACE inhibitor enalapril (Vasotec) or the ARB losartan (Cozaar) than in controls or those receiving hydralazine. They also reported that the number of cysts and the size of the kidneys increased as the amount of sodium in the animals’ drinking water increased.

The potential benefits of giving ACE inhibitors or ARBs to interrupt the RAAS in polycystic disease include reduced intraglomerular pressure, reduced renal vasoconstriction (and consequently, increased renal blood flow), less proteinuria, and decreased production of transforming growth factor beta with less fibrosis. In addition, Schrier et al26 found that “rigorous blood pressure control” (goal < 120/80 mm Hg) led to a greater reduction in left ventricular mass index over time than did standard blood pressure control (goal 135–140/85–90 mm Hg) in patients with ADPKD, and that treatment with enalapril led to a greater reduction than with amlodipine (Norvasc), a calcium channel blocker.

The renal risks of ACE inhibitors include ischemia from further reduction in renal blood flow (which is already compromised by expanding cysts), hyperkalemia, and reversible renal failure that can typically be avoided by judicious dosing and monitoring.27 In addition, these drugs have the well-known side effects of cough and angioedema, and they should be avoided in pregnancy.

If diuretics are used, hypokalemia should be avoided because of both clinical and experimental evidence that it promotes cyst development. In patients who have hyperaldosteronism and hypokalemia, the degree of cyst formation in their kidneys is much greater than in other forms of hypertension. Hypokalemia has also been shown to increase cyst formation in rat models.

What does this mean for our patient?

When hypertension develops in an ADPKD patient, it would probably be best treated with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB. However, should our patient become pregnant, these drugs are to be avoided. Children of a parent with ADPKD have a 50:50 chance of having ADPKD. Genetic counseling may be advisable.

Chapman et al28 found that pregnant women with ADPKD have a significantly higher frequency of maternal complications (particularly hypertension, edema, and preeclampsia) than patients without ADPKD (35% vs 19%, P < .001). Normotensive women with ADPKD and serum creatinine levels of 1.2 mg/dL or less typically had successful, uncomplicated pregnancies. However, 16% of normotensive ADPKD women developed new-onset hypertension in pregnancy and 11% developed preeclampsia; these patients were more likely to develop chronic hypertension. Preeclampsia developed in 7 (54%) of 13 hypertensive women with ADPKD vs 13 (8%) of 157 normotensive ADPKD women. Moreover, 4 (80%) of 5 women with ADPKD who had prepregnancy serum creatinine levels higher than 1.2 mg/dL developed end-stage renal disease 15 years earlier than the general ADPKD population. Overall fetal complication rates were similar in those with or without ADPKD (32.6% vs 26.2%), but fetal prematurity due to preeclampsia was increased significantly (28% vs 10%, P < .01).28

The authors concluded that hypertensive ADPKD women are at high risk of fetal and maternal complications and measures should be taken to prevent the development of preeclampsia in these women.

In conclusion, the patient with ADPKD can present many therapeutic challenges. Fortunately, new treatment approaches combined with established ones should begin to have a favorable impact on outcomes.

- US Renal Data Services. Table A.1, Incident counts of reported ESRD: all patients. USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report, Vol. 3, page 7.

- Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, et al; CRISP Investigators. Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2122–2130.

- Grantham JJ, Cook LT, Torres VE, et al. Determinants of renal volume in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2008; 73:108–116.

- O’Sullivan DA, Torres VE, Heit JA, Liggett S, King BF. Compression of the inferior vena cava by right renal cysts: an unusual cause of IVC and/or iliofemoral thrombosis with pulmonary embolism in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol 1998; 49:332–334.

- Tveit DP, Hypolite I, Bucci J, et al. Risk factors for hospitalizations resulting from pulmonary embolism after renal transplantation in the United States. J Nephrol 2001; 14:361–368.

- Ravine D, Gibson RN, Walker RG, Sheffield LJ, Kincaid-Smith P, Danks DM. Evaluation of ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease 1. Lancet 1994; 343:824–827.

- Rizk D, Chapman AB. Cystic and inherited kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 42:1305–1317.

- Rossetti S, Consugar MB, Chapman AB, et al. Comprehensive molecular diagnostics in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18:2143–2160.

- Rossetti S, Burton S, Strmecki L, et al. The position of the polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene mutation correlates with the severity of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:1230–1237.

- Arnaout MA. Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Annu Rev Med 2001; 52:93–123.

- Pei Y. A “two-hit” model of cystogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? Trends Mol Med 2001; 7:151–156.

- Nauli S, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet 2003; 33:129–137.

- Yamaguchi T, Wallace DP, Magenheimer BS, Hempson SJ, Grantham JJ, Calvet JP. Calcium restriction allows cAMP activation of the B-Raf/ERK pathway, switching cells to a cAMP-dependent growth-stimulated phenotype. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:40419–40430.

- Shillingford JM, Murcia NS, Larson CH, et al. The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:5466–5471.

- Wang X, Gattone V, Harris PC, Torres VE. Effectiveness of vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists OPC-31260 and OPC-41061 on polycystic kidney disease development in the PCK rat. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16:846–851.

- Gattone VH, Wang X, Harris PC, Torres VE. Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med 2003; 9:1323–1326.

- Nagao S, Nishii K, Katsuvama M, et al. Increased water intake decreases progression of polycystic kidney disease in the PCK rat. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:2220–2227.

- Wang W, Wu Y, Ward CJ, Harris PC, Torres VE. Vasopressin directly regulates cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19:102–108.

- Belibi FA, Wallace DP, Yamaguchi T, Christensen M, Reif G, Grantham JJ. The effect of caffeine on renal epithelial cells from patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:2723–2729.

- Mangoo-Karim R, Uchich M, Lechene C, Grantham JJ. Renal epithelial cyst formation and enlargement in vitro: dependence on cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989; 86:6007–6011.

- Wahl PR, Serra AL, Le Hir M, Molle KD, Hall MN, Wuthrich RP. Inhibition of mTOR with sirolimus slows disease progression in Han:SPRD rats with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:598–604.

- Qian Q, Du H, King BF, Kumar S, Dean PG, Cosio FG, Torres VE. Sirolimus reduces polycystic liver volume in ADPKD patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19:631–638.

- Grantham JJ. Therapy for polycystic kidney disease? It’s water, stupid! J Am Soc Nephrol 2008: 12:1–2.

- Keith DS, Torres VE, Johnson CM, Holley KE. Effect of sodium chloride, enalapril, and losartan on the development of polycystic kidney disease in Han:SPRD rats. Am J Kidney Dis 1994; 24:491–498.

- Ecder T, Schrier RW. Hypertension in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: early occurrence and unique aspects. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12:194–200.

- Schrier R, McFann K, Johnson A, et al. Cardiac and renal effects of standard versus rigorous blood pressure control in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: results of a seven-year prospective randomized study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:1733–1739.

- Chapman AB, Gabow PA, Schrier RW. Reversible renal failure associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in polycystic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:769–773.

- Chapman AB, Johnson AM, Gabow PA. Pregnancy outcome and its relationship to progression of renal failure in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 1994; 5:1178–1185.

A 25-year-old married white woman presented to a clinic because of pelvic pain. A computed tomographic scan of her abdomen and pelvis without intravenous contrast showed two definite cysts in the right kidney (the larger measuring 2.5 cm) and a 1.5-cm cyst in the left kidney. It also showed several smaller (< 1 cm) areas of low density in both kidneys that suggested cysts. Renal ultrasonography also showed two cysts in the left kidney and one in the right kidney. The kidneys were normal-sized—the right one measured 12.5 cm and the left one 12.7 cm.

She had no family history of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), and renal ultrasonography of her parents showed no cystic disease. She had no history of headache or heart murmur, and her blood pressure was normal. Her kidneys were barely palpable, her liver was not enlarged, and she had no cardiac murmur or click. She was not taking any medications. Her serum creatinine level was 0.7 mg/dL, hemoglobin 14.0 g/dL, and urinalysis normal.

Does this patient have ADPKD? Based on the studies done so far, would genetic testing be useful? If the genetic analysis does show a mutation, what additional information can be derived from the location of that mutation? Can she do anything to improve her prognosis?

ADPKD ACCOUNTS FOR ABOUT 3% OF END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE

ADPKD is the most common of all inherited renal diseases, with 600,000 to 700,000 cases in the United States and about 12.5 million cases worldwide. About 5,000 to 6,000 new cases are diagnosed yearly in the United States, about 40% of them by age 45. Typically, patients with ADPKD have a family history of the disease, but about 5% to 10% do not. In about 50% of cases, ADPKD progresses to end-stage renal disease by age 60, and it accounts for about 3% of cases of end-stage renal disease in the United States.1

CYSTS IN KIDNEYS AND OTHER ORGANS, AND NONCYSTIC FEATURES

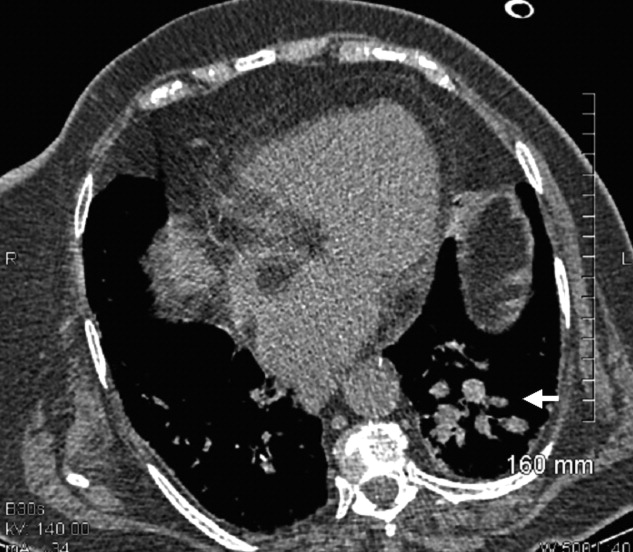

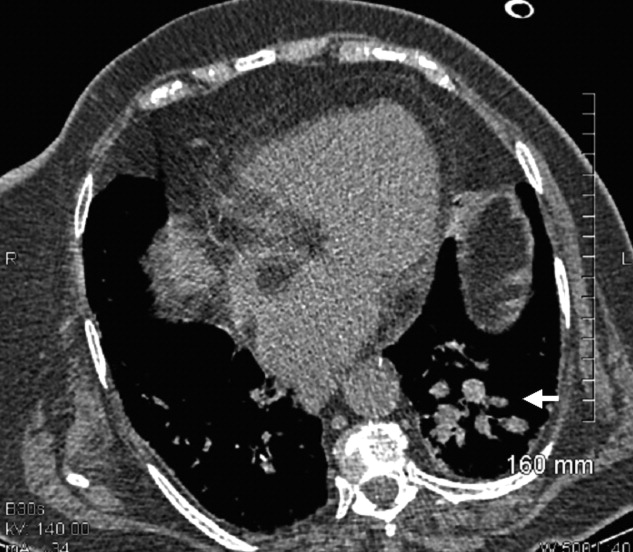

In ADPKD, cysts in the kidneys increase in number and size over time, ultimately destroying normal renal tissue. However, renal function remains steady over many years until the kidneys have approximately quadrupled in volume to 1,500 cm3 (normal combined kidney volume is about 250 to 400 cm3), which defines a tipping point beyond which renal function can rapidly decline.2,3 Ultimately, the patient will need renal replacement therapy, ie, dialysis or renal transplantation.

The cysts (kidney and liver) cause discomfort and pain by putting pressure on the abdominal wall, flanks, and back, by impinging on neighboring organs, by bleeding into the cysts, and by the development of kidney stones or infected cysts (which are uncommon, though urinary tract infections themselves are more frequent). Kidney stones occur in about 20% of patients with ADPKD, and uric acid stones are almost as common as calcium oxalate stones. Compression of the iliac vein and inferior vena cava with possible thrombus formation and pulmonary embolism can be caused by enormous enlargement of the cystic kidneys, particularly the right.4 Interestingly, the patients at greatest risk of pulmonary embolism after renal transplantation are those with ADPKD.5

Cysts can also develop in other organs. Liver cysts develop in about 80% of patients. Usually, the cysts do not affect liver function, but because they are substantially estrogen-dependent they can be more of a clinical problem in women. About 10% of patients have cysts in the pancreas, but these are functionally insignificant. Other locations of cysts include the spleen, arachnoid membranes, and seminal vesicles in men.

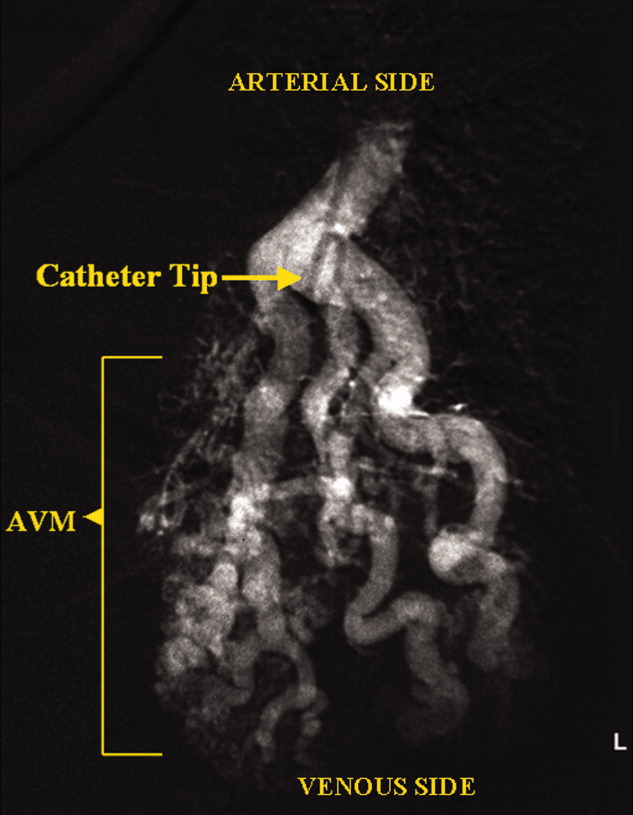

Intracranial aneurysms are a key noncystic feature, and these are strongly influenced by family history. A patient with ADPKD who has a family member with ADPKD as well as an intracranial aneurysm or subarachnoid hemorrhage has about a 20% chance of having an intracranial aneurysm. A key clinical warning is a “sentinel” or “thunderclap” headache, which patients typically rate as at least a 10 on a scale of 10 in severity. In a patient with ADPKD, this type of headache can signal a leaking aneurysm causing irritation and edema of the surrounding brain tissue that temporarily tamponades the bleeding before the aneurysm actually ruptures. This is a critical period when a patient should immediately obtain emergency care.

Cardiac valve abnormalities occur in about one-third of patients. Most common is mitral valve prolapse, which is usually mild. Abnormalities can also occur in the aortic valve and the left ventricular outflow tract.

Hernias are the third general noncystic feature of ADPKD. Patients with ADPKD have an increased prevalence of umbilical, hiatal, and inguinal hernias, as well as diverticulae of the colon.

DOES THIS PATIENT HAVE ADPKD?

The Ravine ultrasonographic criteria for the diagnosis of ADPKD are based on the patient’s age, family history, and number of cysts (Table 1).6,7 Alternatively, Torres (Vincent E. Torres, personal communication, March 2008) recommends that, in the absence of a family history of ADPKD or other findings to suggest other cystic disease, the diagnosis of ADPKD can be made if the patient has a total of at least 20 renal cysts.

Our patient had only three definite cysts, was 25 years old, and had no family history of ADPKD and so did not technically meet the Ravine criteria of five cysts at this age, or the Torres criteria, for having ADPKD. Nevertheless, because she was concerned about overt disease possibly developing later and about passing on a genetic defect to her future offspring, she decided to undergo genetic testing.

CLINICAL GENETICS OF ADPKD: TWO MAJOR TYPES

There are two major genetic forms of ADPKD, caused by mutations in the genes PKD1 and PKD2.

PKD1 has been mapped to the short arm of the 16th chromosome. Its gene product is polycystin 1. Mutations in PKD1 account for about 85% of all cases of polycystic kidney disease. The cysts appear when patients are in their 20s, and the disease progresses relatively rapidly, so that most patients enter end-stage renal disease when they are in their 50s.

PKD2 has been mapped to the long arm of the fourth chromosome. Its product is polycystin 2. PKD2 mutations account for about 15% of all cases of ADPKD, and the disease progresses more slowly, usually with end-stage disease developing when the patients usually are in their 70s.

Screening for mutations by direct DNA sequencing in ADPKD

Genetic testing for PKD1 and PKD2 mutations is available (www.athenadiagnostics.com).8 The Human Gene Mutation Database lists at least 270 different PKD1 mutations and 70 different PKD2 mutations.8 Most are unique to a single family.

Our patient was tested for mutations of the PKD1 and PKD2 genes by polymerase chain reaction amplification and direct DNA sequencing. She was found to possess a DNA sequence variant at a nucleotide position in the PKD1 gene previously reported as a disease-associated mutation. She is therefore likely to be affected with or predisposed to developing ADPKD.

Furthermore, the position of her mutation means she has a worse prognosis. Rossetti et al,9 in a study of 324 PKD1 patients, found that only 19% of those who had mutations in the 5′ region of the gene (ie, at positions below 7,812) still had adequate renal function at 60 years of age, compared with 40% of those with mutations in the 3′ region (P = .025).

Other risk factors for more rapid kidney failure in ADPKD include male sex, onset of hypertension before age 35, gross hematuria before age 30 in men, and, in women, having had three or more pregnancies.

THE ‘TWO-HIT’ HYPOTHESIS

The time of onset and the rate of progression of ADPKD can vary from patient to patient, even in the same family. Besides the factors mentioned above, another reason may be that second mutations (“second hits”) have to occur before the cysts develop.

The first mutation exists in all the kidney tubular cells and is the germline mutation in the PKD gene inherited from the affected parent. This is necessary but not sufficient for cyst formation.

The second hit is a somatic mutation in an individual tubular cell that inactivates to varying degrees the unaffected gene from the normal parent. It is these second hits that allow abnormal focal (monoclonal) proliferation of renal tubular cells and cyst formation (reviewed by Arnaout10 and by Pei11). There is no way to predict these second hits, and their identity is unknown.

Other genetic variations may occur, such as transheterozygous mutations, in which a person may have a mutation of PKD1 as well as PKD2.

Germline mutations of PKD1 or PKD2 combined with somatic mutations of the normal paired chromosome depress levels of their normal gene products (polycystin 1 and polycystin 2) to the point that cysts develop.

The timing and frequency of these second hits blur the distinction between the time course for the progression of PKD1 and PKD2 disease, and can accelerate the course of both.

BASIC RESEARCH POINTS THE WAY TO TREATMENTS FOR ADPKD

Polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 are the normal gene products of the genes which, when mutated, are responsible for PKD1 and PKD2, respectively. Research into the structure and function of the polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 proteins—and what goes wrong when they are not produced in sufficient quantity or accurately—is pointing the way to possible treatments for ADPKD.

When the polycystins are not functioning, as in ADPKD, these proliferative pathways are unopposed. However, proliferation can be countered in other ways. One of the prime movers of cell proliferation, acting through adenylyl cyclase and cAMP, is vasopressin. In genetically produced polycystic animals, two antagonists of the vasopressin V2 receptor (VPV2R), OPC31260 and OPC41061 (tolvaptan), decreased cAMP and ERK, prevented or reduced renal cysts, and preserved renal function.15,16 Not surprisingly, simply increasing water intake decreases vasopressin production and the development of polycystic kidney disease in rats.17 Definitive proof of the role of vasopressin in causing cyst formation was achieved by crossing PCK rats (genetically destined to develop polycystic kidneys) with Brattleboro rats (totally lacking vasopressin) in order to generate rats with polycystic kidneys and varying amounts of vasopressin.18 PCK animals with no vasopressin had virtually no cAMP or renal cysts, whereas PCK animals with increasing amounts of vasopressin had progressively larger kidneys with more numerous cysts. Administration of synthetic vasopressin to PCK rats that totally lacked vasopressin re-created the full cystic disease.

Normally, cAMP is broken down by phosphodiesterases. Caffeine and methylxanthine products such as theophylline interfere with phosphodiesterase activity, raise cAMP in epithelial cell cultures from patients with ADPKD,19 and increase cyst formation in canine kidney cell cultures.20 One could infer that caffeine-containing drinks and foods would be undesirable for ADPKD patients.

The absence of polycystin permits excessive kinase activity in the mTOR pathway and the development of renal cysts.14 The mTOR system can be blocked by rapamycin (sirolimus, Rapamune). Wahl et al21 found that inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin slows PKD progression in rats. In a prospective study in humans, rapamycin reduced polycystic liver volumes in ADPKD renal transplant recipients.22