User login

Genesis and exodus of the healthcare industry

He looked upon the earth so filled with misery and pox

On Cro‐Magnon Neurosurgeons taking tumors out with rocks

With the blood banks run by leeches and their pterodactyl nursing

And observed This can't be healthcare these mere creatures are rehearsing

What shall we do when their lifespan will exceed eleven years?

When they no longer drink from toilet pits or make hearts from used pig ears?

There will need to be a better way to care for newer ills

A time when broadband wireless will be cheaper than their pills

He came up with a brilliant plan to revolutionize the health

To advance all medical outcomes and thereby spread the wealth

But for some strange combination of wisdom, luck, and quirk

He devised sufficient stakeholders to ensure this could not work

So a King might hire a knight to wipe out enemies with his lance

Then buy a plan to pay the cost of repairing his chain mail pants

Then along will come men with crosses of Blue who can manage that so much smarter

By inventing rules that convert poor fools from heroic docs to martyrs

He made tiny things that hide in meat and cause nasty cramps and rashes

That leave only the fittest alive to run in the royal 50 yard dashes

He made plants with spikes and purple leaves that can make one very sick

Then companies who turn green goop to gold that can flow thru a needle stick

He made medical schools to teach more tools, taking 10 years from students' lives

Then ruined careers with malpractice fears if they forget to wash their knives.

He made men whose pockets are filled with stuff from frivolous medical suits

When the experts forget the proper dosing of Peruvian medicinal fruits

He made routine birth a hazardous game between midwife, mom, and fetus

He made people who dress in masks and gloves to bravely retrieve and greet us

Then if anything goes wrong because one more time he throws snake eyes on the dice

He made lawyers to ensure that at least someone benefits while everyone else paid the price

Then along came the buildings with gadgets and learning, to find things we can't hope to fix

And those who get paid to know how NOT to pay the providers of care to the sick

He made organized giants that make tablets and gizmos from the minds of the cream of the crop

And made multiple races with all different faces whose subjective complaints will not stop

But alas came the gadgets, the photons and diodes, the software, the web and the data

Then the standards, the knowledge bases, multiuser interfaces, all in perpetual BETA

To automate the arcane, declare real what is feigned, and make INPUT like losing a toe

Then the last fatal strawhe made privacy laws to ensure they can't share what they know

Oh what have I done, this is really no fun, they now live to one hundred and thirty

But there's no more MDs and the few with degrees refuse to get their hands dirty

Next time when I try to take research to practice I'll start with a real I.O.M.

Evidence galore, so when we screw up once more I can put all the blame right on them

He looked upon the earth so filled with misery and pox

On Cro‐Magnon Neurosurgeons taking tumors out with rocks

With the blood banks run by leeches and their pterodactyl nursing

And observed This can't be healthcare these mere creatures are rehearsing

What shall we do when their lifespan will exceed eleven years?

When they no longer drink from toilet pits or make hearts from used pig ears?

There will need to be a better way to care for newer ills

A time when broadband wireless will be cheaper than their pills

He came up with a brilliant plan to revolutionize the health

To advance all medical outcomes and thereby spread the wealth

But for some strange combination of wisdom, luck, and quirk

He devised sufficient stakeholders to ensure this could not work

So a King might hire a knight to wipe out enemies with his lance

Then buy a plan to pay the cost of repairing his chain mail pants

Then along will come men with crosses of Blue who can manage that so much smarter

By inventing rules that convert poor fools from heroic docs to martyrs

He made tiny things that hide in meat and cause nasty cramps and rashes

That leave only the fittest alive to run in the royal 50 yard dashes

He made plants with spikes and purple leaves that can make one very sick

Then companies who turn green goop to gold that can flow thru a needle stick

He made medical schools to teach more tools, taking 10 years from students' lives

Then ruined careers with malpractice fears if they forget to wash their knives.

He made men whose pockets are filled with stuff from frivolous medical suits

When the experts forget the proper dosing of Peruvian medicinal fruits

He made routine birth a hazardous game between midwife, mom, and fetus

He made people who dress in masks and gloves to bravely retrieve and greet us

Then if anything goes wrong because one more time he throws snake eyes on the dice

He made lawyers to ensure that at least someone benefits while everyone else paid the price

Then along came the buildings with gadgets and learning, to find things we can't hope to fix

And those who get paid to know how NOT to pay the providers of care to the sick

He made organized giants that make tablets and gizmos from the minds of the cream of the crop

And made multiple races with all different faces whose subjective complaints will not stop

But alas came the gadgets, the photons and diodes, the software, the web and the data

Then the standards, the knowledge bases, multiuser interfaces, all in perpetual BETA

To automate the arcane, declare real what is feigned, and make INPUT like losing a toe

Then the last fatal strawhe made privacy laws to ensure they can't share what they know

Oh what have I done, this is really no fun, they now live to one hundred and thirty

But there's no more MDs and the few with degrees refuse to get their hands dirty

Next time when I try to take research to practice I'll start with a real I.O.M.

Evidence galore, so when we screw up once more I can put all the blame right on them

He looked upon the earth so filled with misery and pox

On Cro‐Magnon Neurosurgeons taking tumors out with rocks

With the blood banks run by leeches and their pterodactyl nursing

And observed This can't be healthcare these mere creatures are rehearsing

What shall we do when their lifespan will exceed eleven years?

When they no longer drink from toilet pits or make hearts from used pig ears?

There will need to be a better way to care for newer ills

A time when broadband wireless will be cheaper than their pills

He came up with a brilliant plan to revolutionize the health

To advance all medical outcomes and thereby spread the wealth

But for some strange combination of wisdom, luck, and quirk

He devised sufficient stakeholders to ensure this could not work

So a King might hire a knight to wipe out enemies with his lance

Then buy a plan to pay the cost of repairing his chain mail pants

Then along will come men with crosses of Blue who can manage that so much smarter

By inventing rules that convert poor fools from heroic docs to martyrs

He made tiny things that hide in meat and cause nasty cramps and rashes

That leave only the fittest alive to run in the royal 50 yard dashes

He made plants with spikes and purple leaves that can make one very sick

Then companies who turn green goop to gold that can flow thru a needle stick

He made medical schools to teach more tools, taking 10 years from students' lives

Then ruined careers with malpractice fears if they forget to wash their knives.

He made men whose pockets are filled with stuff from frivolous medical suits

When the experts forget the proper dosing of Peruvian medicinal fruits

He made routine birth a hazardous game between midwife, mom, and fetus

He made people who dress in masks and gloves to bravely retrieve and greet us

Then if anything goes wrong because one more time he throws snake eyes on the dice

He made lawyers to ensure that at least someone benefits while everyone else paid the price

Then along came the buildings with gadgets and learning, to find things we can't hope to fix

And those who get paid to know how NOT to pay the providers of care to the sick

He made organized giants that make tablets and gizmos from the minds of the cream of the crop

And made multiple races with all different faces whose subjective complaints will not stop

But alas came the gadgets, the photons and diodes, the software, the web and the data

Then the standards, the knowledge bases, multiuser interfaces, all in perpetual BETA

To automate the arcane, declare real what is feigned, and make INPUT like losing a toe

Then the last fatal strawhe made privacy laws to ensure they can't share what they know

Oh what have I done, this is really no fun, they now live to one hundred and thirty

But there's no more MDs and the few with degrees refuse to get their hands dirty

Next time when I try to take research to practice I'll start with a real I.O.M.

Evidence galore, so when we screw up once more I can put all the blame right on them

Rapid Response: A QI Conundrum

Many in‐hospital cardiac arrests and other adverse events are heralded by warning signs that are evident in the preceding 6 to 8 hours.1 By promptly intervening before further deterioration occurs, rapid response teams (RRTs) are designed to decrease unexpected intensive care unit (ICU) transfers, cardiac arrests, and inpatient mortality. While implementing RRTs is 1 of the 6 initiatives recommended by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,2 data supporting their effectiveness is equivocal.3, 4

In October 2006, at Denver Health Medical Center, an academic, safety net hospital, we initiated a rapid response systemclinical triggers program (RRS‐CTP).5 In our RRS‐CTP, an abrupt change in patient status (Figure 1) triggers a mandatory call by the patient's nurse to the primary team, which is then required to perform an immediate bedside evaluation. By incorporating the primary team into the RRT‐CTP, we sought to preserve as much continuity of care as possible. Also, since the same house staff compose our cardiopulmonary arrest or cor team, and staff the ICUs and non‐ICU hospital wards, we did not feel that creating a separate RRT was an efficient use of resources. Our nurses have undergone extensive education about the necessity of a prompt bedside evaluation and have been instructed and empowered to escalate concerns to senior physicians if needed. We present a case that illustrates challenges to both implementing an RRS and measuring its potential benefits.

Case

A 59‐year‐old woman with a history of bipolar mood disorder was admitted for altered mental status. At presentation, she had signs of acute mania with normal vital signs. After initial laboratory workup, her altered mental status was felt to be multifactorial due to urinary tract infection, hypernatremia (attributed to lithium‐induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus), and acute mania (attributed to medication discontinuation). Because she was slow to recover from the acute mania, her hospital stay was prolonged. From admission, the patient was treated with heparin 5000 units subcutaneously twice daily for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

On hospital day 7, at 21:32, the patient was noted to have asymptomatic tachycardia at 149 beats per minute and a new oxygen requirement of 3 L/minute. The cross‐cover team was called; however, although criteria were met, the RRS‐CTP was not activated and a bedside evaluation was not performed. A chest X‐ray was found to be normal and, with the exception of the oxygen requirement, her vital signs normalized by 23:45. No further diagnostic testing was performed at the time.

The next morning, at 11:58, the patient was found to have a blood pressure of 60/40 mmHg and heart rate of 42 beats per minute. The RRS‐CTP was activated. The primary team arrived at the bedside at 12:00 and found the patient to be alert, oriented, and without complaints. Her respiratory rate was 30/minute, and her oxygen saturation was 86% on 3 L/minute. An arterial blood gas analysis demonstrated acute respiratory alkalosis with hypoxemia and an electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with a new S1Q3T3 pattern. A computed tomography angiogram revealed a large, nearly occlusive pulmonary embolus (PE) filling an enlarged right pulmonary artery, as well as thrombus within the left main pulmonary artery. She was transferred to the medical ICU and alteplase was administered. The patient survived and was discharged in good clinical condition.

Discussion

Despite the strong theoretical benefit of the RRT concept, a recent review by Ranji et al.4 concluded that RRTs had not yet been shown to improve patient outcomes. In contrast to dedicated RRTs, this case illustrates a different type of RRS that was designed to address abrupt changes in patient status, while maintaining continuity of care and efficiently utilizing resources.

If one considers an RRS to have both afferent (criteria recognition) and efferent (RRT or primary team response) limbs, the afferent limb must be consistently activated in order to obtain the efferent limb's response.6 The greatest opportunities to improve RRSs are thought to lie in the afferent limb.3 Our RRS‐CTP was not triggered in 1 of 2 instances in which criteria for mandatory initiation of the system were met. This is consistent with the findings of the Medical Early Response Intervention and Therapy (MERIT) trial, in which RRTs were called in only 41% of the patients meeting criteria and subsequently having adverse events,7 and with the ongoing monitoring of the use of the system at our hospital. Had the cross‐covering team seen the patient at the bedside initially, the PE might have been diagnosed while the patient was hemodynamically stable, giving the patient nearly a 3‐fold lower relative mortality.8 When the RRS‐CTP was activated, a prompt bedside evaluation occurred, allowing for lytic therapy to be administered before cardiopulmonary arrest (attendant mortality of 90%).9

While rapid response criteria were originally based upon published sensitivity analyses, more recent studies suggest that these criteria lack diagnostic accuracy. As demonstrated by Cretikos et al,10 to reach a sensitivity of 70%, the corresponding specificity would be only 86%. Given that the prevalence of adverse events in the MERIT trial was only 0.6%, the resulting positive predictive value (PPV) of rapid response call criteria is 3%. Accordingly, 33 calls would be needed to prevent 1 unplanned ICU transfer, cardiac arrest, or death. Nurses' attempts to minimize false‐positive calls may help explain the low call rates for patients meeting RRT criteria. The 2 avenues to increase the PPV of criteria are:

-

Increase the prevalence of disease in the population screened by risk factor stratification.

-

Increase the specificity of the call criteria, which has been limited by the associated decrease in sensitivity.10

Regarding the efferent response limb of RRS, our case demonstrates that the primary team (rather than a separate group of caregivers), when alerted appropriately, can effectively respond to critical changes in patient status. Accordingly, our data show that since the inception of the program, cardiopulmonary arrests have decreased from a mean of 4.1 per month to 2.3 per month (P = 0.03).

Many clinical trials of RRTs would not capture the success demonstrated in this case. For example, due to the low prevalence of events, the MERIT trial used a composite endpoint that included unplanned ICU transfers, cardiac arrests, and mortality. Because our patient still required an unplanned ICU transfer after being evaluated by the responding team, she would have been counted as a system failure.

Conclusion

While local needs should inform the type of RRS implemented, this case illustrates one of the major obstacles ubiquitous to RRS implementation: failure of system activation. With appropriate activation, an RRS‐CTP can meet RRS goals while maintaining continuity of care and maximizing existing resources. This case also illustrates the difficulty of achieving a statistically relevant outcome, while demonstrating the potential benefits of evolving RRSs.

- ,,,,.Rapid response teams—do they make a difference.Dimens Crit Care Nurs.2007;26(6):253–260.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 5 Million Lives Campaign. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/Campaign.htm?TabId=1IHI. Accessed February2009.

- .The rapid response team paradox: why doesn't anyone call for help?Crit Care Med.2008;36(2):634–636.

- ,,,,.Effects of rapid response systems on clinical outcomes: review and meta‐analyses.J Hosp Med.2007;2:422–432.

- ,,.Clinical triggers and rapid response escalation criteria.Patient Saf Qual Healthc.2007;4(2):12–13. Available at: http://www.psqh.com/archives.html. Accessed February 2009.

- ,,, et al.Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrest.Qual Saf Health Care.2004;13:251–254.

- MERIT Study Investigators.Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial.Lancet.2005;365:2091–2097.

- ,,.Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the international cooperative pulmonary embolism registry (ICOPER).Lancet.1999;353(9162):1386–1389.

- ,,,.Early predictors of mortality for hospitalized patients suffering cardiopulmonary arrest.Chest.1990;97(2):413–419.

- ,,,,,.The objective medical emergency team activation criteria: a case–control study.Resuscitation.2007;73:62–72.

Many in‐hospital cardiac arrests and other adverse events are heralded by warning signs that are evident in the preceding 6 to 8 hours.1 By promptly intervening before further deterioration occurs, rapid response teams (RRTs) are designed to decrease unexpected intensive care unit (ICU) transfers, cardiac arrests, and inpatient mortality. While implementing RRTs is 1 of the 6 initiatives recommended by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,2 data supporting their effectiveness is equivocal.3, 4

In October 2006, at Denver Health Medical Center, an academic, safety net hospital, we initiated a rapid response systemclinical triggers program (RRS‐CTP).5 In our RRS‐CTP, an abrupt change in patient status (Figure 1) triggers a mandatory call by the patient's nurse to the primary team, which is then required to perform an immediate bedside evaluation. By incorporating the primary team into the RRT‐CTP, we sought to preserve as much continuity of care as possible. Also, since the same house staff compose our cardiopulmonary arrest or cor team, and staff the ICUs and non‐ICU hospital wards, we did not feel that creating a separate RRT was an efficient use of resources. Our nurses have undergone extensive education about the necessity of a prompt bedside evaluation and have been instructed and empowered to escalate concerns to senior physicians if needed. We present a case that illustrates challenges to both implementing an RRS and measuring its potential benefits.

Case

A 59‐year‐old woman with a history of bipolar mood disorder was admitted for altered mental status. At presentation, she had signs of acute mania with normal vital signs. After initial laboratory workup, her altered mental status was felt to be multifactorial due to urinary tract infection, hypernatremia (attributed to lithium‐induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus), and acute mania (attributed to medication discontinuation). Because she was slow to recover from the acute mania, her hospital stay was prolonged. From admission, the patient was treated with heparin 5000 units subcutaneously twice daily for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

On hospital day 7, at 21:32, the patient was noted to have asymptomatic tachycardia at 149 beats per minute and a new oxygen requirement of 3 L/minute. The cross‐cover team was called; however, although criteria were met, the RRS‐CTP was not activated and a bedside evaluation was not performed. A chest X‐ray was found to be normal and, with the exception of the oxygen requirement, her vital signs normalized by 23:45. No further diagnostic testing was performed at the time.

The next morning, at 11:58, the patient was found to have a blood pressure of 60/40 mmHg and heart rate of 42 beats per minute. The RRS‐CTP was activated. The primary team arrived at the bedside at 12:00 and found the patient to be alert, oriented, and without complaints. Her respiratory rate was 30/minute, and her oxygen saturation was 86% on 3 L/minute. An arterial blood gas analysis demonstrated acute respiratory alkalosis with hypoxemia and an electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with a new S1Q3T3 pattern. A computed tomography angiogram revealed a large, nearly occlusive pulmonary embolus (PE) filling an enlarged right pulmonary artery, as well as thrombus within the left main pulmonary artery. She was transferred to the medical ICU and alteplase was administered. The patient survived and was discharged in good clinical condition.

Discussion

Despite the strong theoretical benefit of the RRT concept, a recent review by Ranji et al.4 concluded that RRTs had not yet been shown to improve patient outcomes. In contrast to dedicated RRTs, this case illustrates a different type of RRS that was designed to address abrupt changes in patient status, while maintaining continuity of care and efficiently utilizing resources.

If one considers an RRS to have both afferent (criteria recognition) and efferent (RRT or primary team response) limbs, the afferent limb must be consistently activated in order to obtain the efferent limb's response.6 The greatest opportunities to improve RRSs are thought to lie in the afferent limb.3 Our RRS‐CTP was not triggered in 1 of 2 instances in which criteria for mandatory initiation of the system were met. This is consistent with the findings of the Medical Early Response Intervention and Therapy (MERIT) trial, in which RRTs were called in only 41% of the patients meeting criteria and subsequently having adverse events,7 and with the ongoing monitoring of the use of the system at our hospital. Had the cross‐covering team seen the patient at the bedside initially, the PE might have been diagnosed while the patient was hemodynamically stable, giving the patient nearly a 3‐fold lower relative mortality.8 When the RRS‐CTP was activated, a prompt bedside evaluation occurred, allowing for lytic therapy to be administered before cardiopulmonary arrest (attendant mortality of 90%).9

While rapid response criteria were originally based upon published sensitivity analyses, more recent studies suggest that these criteria lack diagnostic accuracy. As demonstrated by Cretikos et al,10 to reach a sensitivity of 70%, the corresponding specificity would be only 86%. Given that the prevalence of adverse events in the MERIT trial was only 0.6%, the resulting positive predictive value (PPV) of rapid response call criteria is 3%. Accordingly, 33 calls would be needed to prevent 1 unplanned ICU transfer, cardiac arrest, or death. Nurses' attempts to minimize false‐positive calls may help explain the low call rates for patients meeting RRT criteria. The 2 avenues to increase the PPV of criteria are:

-

Increase the prevalence of disease in the population screened by risk factor stratification.

-

Increase the specificity of the call criteria, which has been limited by the associated decrease in sensitivity.10

Regarding the efferent response limb of RRS, our case demonstrates that the primary team (rather than a separate group of caregivers), when alerted appropriately, can effectively respond to critical changes in patient status. Accordingly, our data show that since the inception of the program, cardiopulmonary arrests have decreased from a mean of 4.1 per month to 2.3 per month (P = 0.03).

Many clinical trials of RRTs would not capture the success demonstrated in this case. For example, due to the low prevalence of events, the MERIT trial used a composite endpoint that included unplanned ICU transfers, cardiac arrests, and mortality. Because our patient still required an unplanned ICU transfer after being evaluated by the responding team, she would have been counted as a system failure.

Conclusion

While local needs should inform the type of RRS implemented, this case illustrates one of the major obstacles ubiquitous to RRS implementation: failure of system activation. With appropriate activation, an RRS‐CTP can meet RRS goals while maintaining continuity of care and maximizing existing resources. This case also illustrates the difficulty of achieving a statistically relevant outcome, while demonstrating the potential benefits of evolving RRSs.

Many in‐hospital cardiac arrests and other adverse events are heralded by warning signs that are evident in the preceding 6 to 8 hours.1 By promptly intervening before further deterioration occurs, rapid response teams (RRTs) are designed to decrease unexpected intensive care unit (ICU) transfers, cardiac arrests, and inpatient mortality. While implementing RRTs is 1 of the 6 initiatives recommended by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,2 data supporting their effectiveness is equivocal.3, 4

In October 2006, at Denver Health Medical Center, an academic, safety net hospital, we initiated a rapid response systemclinical triggers program (RRS‐CTP).5 In our RRS‐CTP, an abrupt change in patient status (Figure 1) triggers a mandatory call by the patient's nurse to the primary team, which is then required to perform an immediate bedside evaluation. By incorporating the primary team into the RRT‐CTP, we sought to preserve as much continuity of care as possible. Also, since the same house staff compose our cardiopulmonary arrest or cor team, and staff the ICUs and non‐ICU hospital wards, we did not feel that creating a separate RRT was an efficient use of resources. Our nurses have undergone extensive education about the necessity of a prompt bedside evaluation and have been instructed and empowered to escalate concerns to senior physicians if needed. We present a case that illustrates challenges to both implementing an RRS and measuring its potential benefits.

Case

A 59‐year‐old woman with a history of bipolar mood disorder was admitted for altered mental status. At presentation, she had signs of acute mania with normal vital signs. After initial laboratory workup, her altered mental status was felt to be multifactorial due to urinary tract infection, hypernatremia (attributed to lithium‐induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus), and acute mania (attributed to medication discontinuation). Because she was slow to recover from the acute mania, her hospital stay was prolonged. From admission, the patient was treated with heparin 5000 units subcutaneously twice daily for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

On hospital day 7, at 21:32, the patient was noted to have asymptomatic tachycardia at 149 beats per minute and a new oxygen requirement of 3 L/minute. The cross‐cover team was called; however, although criteria were met, the RRS‐CTP was not activated and a bedside evaluation was not performed. A chest X‐ray was found to be normal and, with the exception of the oxygen requirement, her vital signs normalized by 23:45. No further diagnostic testing was performed at the time.

The next morning, at 11:58, the patient was found to have a blood pressure of 60/40 mmHg and heart rate of 42 beats per minute. The RRS‐CTP was activated. The primary team arrived at the bedside at 12:00 and found the patient to be alert, oriented, and without complaints. Her respiratory rate was 30/minute, and her oxygen saturation was 86% on 3 L/minute. An arterial blood gas analysis demonstrated acute respiratory alkalosis with hypoxemia and an electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with a new S1Q3T3 pattern. A computed tomography angiogram revealed a large, nearly occlusive pulmonary embolus (PE) filling an enlarged right pulmonary artery, as well as thrombus within the left main pulmonary artery. She was transferred to the medical ICU and alteplase was administered. The patient survived and was discharged in good clinical condition.

Discussion

Despite the strong theoretical benefit of the RRT concept, a recent review by Ranji et al.4 concluded that RRTs had not yet been shown to improve patient outcomes. In contrast to dedicated RRTs, this case illustrates a different type of RRS that was designed to address abrupt changes in patient status, while maintaining continuity of care and efficiently utilizing resources.

If one considers an RRS to have both afferent (criteria recognition) and efferent (RRT or primary team response) limbs, the afferent limb must be consistently activated in order to obtain the efferent limb's response.6 The greatest opportunities to improve RRSs are thought to lie in the afferent limb.3 Our RRS‐CTP was not triggered in 1 of 2 instances in which criteria for mandatory initiation of the system were met. This is consistent with the findings of the Medical Early Response Intervention and Therapy (MERIT) trial, in which RRTs were called in only 41% of the patients meeting criteria and subsequently having adverse events,7 and with the ongoing monitoring of the use of the system at our hospital. Had the cross‐covering team seen the patient at the bedside initially, the PE might have been diagnosed while the patient was hemodynamically stable, giving the patient nearly a 3‐fold lower relative mortality.8 When the RRS‐CTP was activated, a prompt bedside evaluation occurred, allowing for lytic therapy to be administered before cardiopulmonary arrest (attendant mortality of 90%).9

While rapid response criteria were originally based upon published sensitivity analyses, more recent studies suggest that these criteria lack diagnostic accuracy. As demonstrated by Cretikos et al,10 to reach a sensitivity of 70%, the corresponding specificity would be only 86%. Given that the prevalence of adverse events in the MERIT trial was only 0.6%, the resulting positive predictive value (PPV) of rapid response call criteria is 3%. Accordingly, 33 calls would be needed to prevent 1 unplanned ICU transfer, cardiac arrest, or death. Nurses' attempts to minimize false‐positive calls may help explain the low call rates for patients meeting RRT criteria. The 2 avenues to increase the PPV of criteria are:

-

Increase the prevalence of disease in the population screened by risk factor stratification.

-

Increase the specificity of the call criteria, which has been limited by the associated decrease in sensitivity.10

Regarding the efferent response limb of RRS, our case demonstrates that the primary team (rather than a separate group of caregivers), when alerted appropriately, can effectively respond to critical changes in patient status. Accordingly, our data show that since the inception of the program, cardiopulmonary arrests have decreased from a mean of 4.1 per month to 2.3 per month (P = 0.03).

Many clinical trials of RRTs would not capture the success demonstrated in this case. For example, due to the low prevalence of events, the MERIT trial used a composite endpoint that included unplanned ICU transfers, cardiac arrests, and mortality. Because our patient still required an unplanned ICU transfer after being evaluated by the responding team, she would have been counted as a system failure.

Conclusion

While local needs should inform the type of RRS implemented, this case illustrates one of the major obstacles ubiquitous to RRS implementation: failure of system activation. With appropriate activation, an RRS‐CTP can meet RRS goals while maintaining continuity of care and maximizing existing resources. This case also illustrates the difficulty of achieving a statistically relevant outcome, while demonstrating the potential benefits of evolving RRSs.

- ,,,,.Rapid response teams—do they make a difference.Dimens Crit Care Nurs.2007;26(6):253–260.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 5 Million Lives Campaign. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/Campaign.htm?TabId=1IHI. Accessed February2009.

- .The rapid response team paradox: why doesn't anyone call for help?Crit Care Med.2008;36(2):634–636.

- ,,,,.Effects of rapid response systems on clinical outcomes: review and meta‐analyses.J Hosp Med.2007;2:422–432.

- ,,.Clinical triggers and rapid response escalation criteria.Patient Saf Qual Healthc.2007;4(2):12–13. Available at: http://www.psqh.com/archives.html. Accessed February 2009.

- ,,, et al.Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrest.Qual Saf Health Care.2004;13:251–254.

- MERIT Study Investigators.Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial.Lancet.2005;365:2091–2097.

- ,,.Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the international cooperative pulmonary embolism registry (ICOPER).Lancet.1999;353(9162):1386–1389.

- ,,,.Early predictors of mortality for hospitalized patients suffering cardiopulmonary arrest.Chest.1990;97(2):413–419.

- ,,,,,.The objective medical emergency team activation criteria: a case–control study.Resuscitation.2007;73:62–72.

- ,,,,.Rapid response teams—do they make a difference.Dimens Crit Care Nurs.2007;26(6):253–260.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 5 Million Lives Campaign. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/Campaign.htm?TabId=1IHI. Accessed February2009.

- .The rapid response team paradox: why doesn't anyone call for help?Crit Care Med.2008;36(2):634–636.

- ,,,,.Effects of rapid response systems on clinical outcomes: review and meta‐analyses.J Hosp Med.2007;2:422–432.

- ,,.Clinical triggers and rapid response escalation criteria.Patient Saf Qual Healthc.2007;4(2):12–13. Available at: http://www.psqh.com/archives.html. Accessed February 2009.

- ,,, et al.Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrest.Qual Saf Health Care.2004;13:251–254.

- MERIT Study Investigators.Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial.Lancet.2005;365:2091–2097.

- ,,.Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the international cooperative pulmonary embolism registry (ICOPER).Lancet.1999;353(9162):1386–1389.

- ,,,.Early predictors of mortality for hospitalized patients suffering cardiopulmonary arrest.Chest.1990;97(2):413–419.

- ,,,,,.The objective medical emergency team activation criteria: a case–control study.Resuscitation.2007;73:62–72.

The Accidental Hospitalist

David Yu, MD, learned early on the value of being flexible. While attending Washington University in St. Louis, he found his calling when he changed his major from economics to biology. When the malpractice insurance crisis forced him to close his private practice, he embraced an opportunity to launch a program devoted to the “newfangled concept” of hospital medicine.

“I’m kind of like the accidental tourist,” says Dr. Yu, medical director of hospitalist services at the 372-bed Decatur Memorial Hospital in Decatur, Ill., and clinical assistant professor of family and community medicine at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine in Carbondale. “I didn’t really go to college with the mind-set of being a doctor, and when I became a doctor, there was no such thing as a hospitalist. … I went where the current took me and, fortunately, here I am.”

Question: What prompted the switch from economics to pre-med/biology?

Answer: When I got to the upper-level econ classes, I realized why the economy is the way it is: because nobody can understand how it works. My sister was in medical school. She really liked it and she talked me into it.

Q: You spent nine years in traditional practice. Why did you become a hospitalist?

A: In 2004, my malpractice insurance rate shot up 400% without any active lawsuits, so I had to close my practice. I had the choice of joining another traditional group, or Decatur (Memorial Hospital) was starting a new hospitalist program. To quote “The Godfather,” they made me an offer I couldn’t refuse.

Q: How did your experience in traditional practice prepare you for your role as a hospitalist?

A: I had been surrounded by incredible specialists. I saw how they interacted with me and how they treated my patients. As hospitalists, we are serving our patients, but really our clientele is the physicians we admit for. When I made the switch, I really had an idea of how a hospitalist should serve traditional practice.

Q: What is that service model?

A: It comes down to what I call the three A’s: You have to be available, you have to be able, and you have to be amicable. One of the problems in our field is a lot of hospitalists complain they’re treated like residents. They say they don’t get respect. They feel mistreated. That’s the wrong attitude. You can’t just ask for respect or demand it. You have to develop relationships.

Q: When Decatur’s hospitalist program started, you were on your own. Now there are seven physicians, two physician assistants, and a practice manager. How rewarding has it been to see it grow?

We have to find ways to help hospitalists take more ownership in their patients and their program. ... With our schedule, you can’t pawn off your responsibility to the nocturnist or the weekend guy.

—David Yu, MD, Decatur (Ill.)

Memorial Hospital

A: It’s been very rewarding. I’m honored to have been chosen as a member of Team Hospitalist, and I’m honored to be a committee member for SHM’s Non-Physician Provider Committee. Those are personal honors, but they are reflections on the success of the program. It’s an honor for the entire Decatur Memorial Hospital, and the administration, that a program started four and a half years ago, indirectly, has received national recognition.

Q: You implemented a one-week-on, one-week-off schedule for your hospitalists as a way to decrease signouts. How did that come about?

A: Signouts have been the bane of medical mistakes. Instead of having signouts twice a day, we have one physician on call for that entire week for his or her patients. It’s patient-centric versus schedule-centric. Physicians leave the hospital when their work is done, instead of looking at the clock and waiting to sign out at a certain time like a factory worker. It treats hospitalists not as shift workers but as attending physicians. It gives them due respect that they can manage their own patients responsibly.

Q: Do you think the schedule improves the quality of patient care?

A: The continuity of care is incredible. If you are admitted and discharged between Mondays, you have one hospitalist in charge of your entire case, instead of multiple physicians being on call for you. That increases patient satisfaction, reduces medical errors, and eliminates the need for unnecessary tests when new physicians take over. I’m also a huge believer that scheduling brings out the best and worst in hospitalists.

Q: How does it bring out the best in them?

A: As medical directors, we have to find ways to help hospitalists take more ownership in their patients and their program. If they’re thinking, “My shift is ending and I’m going to be off and I can hand this issue off to the next doctor,” that can have a tremendous effect on the quality of care and the way a hospitalist delivers medicine. With our schedule, you can’t pawn off your responsibility to the nocturnist or the weekend guy. … If something goes wrong or if the ball gets dropped, there’s no one else to blame it on.

Q: You developed a system at Decatur through which patient discharge summaries are sent electronically to primary-care physicians, often before the patient leaves the hospital. Have the primaries been receptive?

A: Absolutely. Communication is the mother’s milk of hospitalists. Some hospitalist programs are very large, they’re very busy, or there’s no incentive for them to do this because they’re the only game in town. But I practice in a mid-size community and I know all of these doctors. My reputation is my bond. I have to provide good service.

Q: What do you enjoy most about your role as a hospitalist?

A: I love solving problems for a patient. I also love how the relationship builds. You introduce yourself to a patient and their family as a hospitalist and they’re thinking, “Who the heck are you?” For a few seconds, it’s like meeting someone on a blind date. And when they’re discharged, they tell you they had a pleasant experience and they appreciate your help. It’s a courtship at a rapid pace.

Q: What do you consider to be your biggest challenge?

A: Recruitment; the administration asking us to take on more responsibilities; burnout. … We’re a typical hospitalist program; I think the problems are pretty universal.

Q: How do you address those challenges?

A: As medical director, you’re always navigating political and personal minefields. It comes back to developing relationships. The only way to earn goodwill is to give and provide service. That’s a problem some hospitalist programs run into. They want to instantly demand respect. You can’t demand it; you have to earn it. Sometimes hospitalists feel dumped on. Those are opportunities … to provide service in a willing and positive way instead of complaining. I’m not saying you have to be a whipping boy, but there are times when you have to give a little to get a little. That’s where the wisdom of the medical director comes in and sets the whole tone.

Q: What’s ahead for the academic side of your career?

A: We’re considering the possibility of starting a family practice fellowship program for attending residents who finish but want to go into the field of hospital medicine and want additional training. It’s not a done deal, but it’s an exciting possibility.

Q: How so?

A: Every medical director says they have a hard time recruiting. One way we can help solve the problem is by producing more hospitalists. We can’t just complain. We have to increase the pool of professionals interested in our model, train them, and get them integrated into our system.

Q: What advice would you give a student who is considering going that route?

A: You have to be a good communicator, you have to enjoy taking care of very sick people, and you have to enjoy solving very complex problems. You can’t just do it for the lifestyle. If you do, you won’t be happy in the long run. If I ask a medical student or resident why they want to be a hospitalist and they say, “I like the one-week-on, one-week-off schedule,” I tell them, “If that’s the reason you’re considering it, you really should reconsider.” TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

David Yu, MD, learned early on the value of being flexible. While attending Washington University in St. Louis, he found his calling when he changed his major from economics to biology. When the malpractice insurance crisis forced him to close his private practice, he embraced an opportunity to launch a program devoted to the “newfangled concept” of hospital medicine.

“I’m kind of like the accidental tourist,” says Dr. Yu, medical director of hospitalist services at the 372-bed Decatur Memorial Hospital in Decatur, Ill., and clinical assistant professor of family and community medicine at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine in Carbondale. “I didn’t really go to college with the mind-set of being a doctor, and when I became a doctor, there was no such thing as a hospitalist. … I went where the current took me and, fortunately, here I am.”

Question: What prompted the switch from economics to pre-med/biology?

Answer: When I got to the upper-level econ classes, I realized why the economy is the way it is: because nobody can understand how it works. My sister was in medical school. She really liked it and she talked me into it.

Q: You spent nine years in traditional practice. Why did you become a hospitalist?

A: In 2004, my malpractice insurance rate shot up 400% without any active lawsuits, so I had to close my practice. I had the choice of joining another traditional group, or Decatur (Memorial Hospital) was starting a new hospitalist program. To quote “The Godfather,” they made me an offer I couldn’t refuse.

Q: How did your experience in traditional practice prepare you for your role as a hospitalist?

A: I had been surrounded by incredible specialists. I saw how they interacted with me and how they treated my patients. As hospitalists, we are serving our patients, but really our clientele is the physicians we admit for. When I made the switch, I really had an idea of how a hospitalist should serve traditional practice.

Q: What is that service model?

A: It comes down to what I call the three A’s: You have to be available, you have to be able, and you have to be amicable. One of the problems in our field is a lot of hospitalists complain they’re treated like residents. They say they don’t get respect. They feel mistreated. That’s the wrong attitude. You can’t just ask for respect or demand it. You have to develop relationships.

Q: When Decatur’s hospitalist program started, you were on your own. Now there are seven physicians, two physician assistants, and a practice manager. How rewarding has it been to see it grow?

We have to find ways to help hospitalists take more ownership in their patients and their program. ... With our schedule, you can’t pawn off your responsibility to the nocturnist or the weekend guy.

—David Yu, MD, Decatur (Ill.)

Memorial Hospital

A: It’s been very rewarding. I’m honored to have been chosen as a member of Team Hospitalist, and I’m honored to be a committee member for SHM’s Non-Physician Provider Committee. Those are personal honors, but they are reflections on the success of the program. It’s an honor for the entire Decatur Memorial Hospital, and the administration, that a program started four and a half years ago, indirectly, has received national recognition.

Q: You implemented a one-week-on, one-week-off schedule for your hospitalists as a way to decrease signouts. How did that come about?

A: Signouts have been the bane of medical mistakes. Instead of having signouts twice a day, we have one physician on call for that entire week for his or her patients. It’s patient-centric versus schedule-centric. Physicians leave the hospital when their work is done, instead of looking at the clock and waiting to sign out at a certain time like a factory worker. It treats hospitalists not as shift workers but as attending physicians. It gives them due respect that they can manage their own patients responsibly.

Q: Do you think the schedule improves the quality of patient care?

A: The continuity of care is incredible. If you are admitted and discharged between Mondays, you have one hospitalist in charge of your entire case, instead of multiple physicians being on call for you. That increases patient satisfaction, reduces medical errors, and eliminates the need for unnecessary tests when new physicians take over. I’m also a huge believer that scheduling brings out the best and worst in hospitalists.

Q: How does it bring out the best in them?

A: As medical directors, we have to find ways to help hospitalists take more ownership in their patients and their program. If they’re thinking, “My shift is ending and I’m going to be off and I can hand this issue off to the next doctor,” that can have a tremendous effect on the quality of care and the way a hospitalist delivers medicine. With our schedule, you can’t pawn off your responsibility to the nocturnist or the weekend guy. … If something goes wrong or if the ball gets dropped, there’s no one else to blame it on.

Q: You developed a system at Decatur through which patient discharge summaries are sent electronically to primary-care physicians, often before the patient leaves the hospital. Have the primaries been receptive?

A: Absolutely. Communication is the mother’s milk of hospitalists. Some hospitalist programs are very large, they’re very busy, or there’s no incentive for them to do this because they’re the only game in town. But I practice in a mid-size community and I know all of these doctors. My reputation is my bond. I have to provide good service.

Q: What do you enjoy most about your role as a hospitalist?

A: I love solving problems for a patient. I also love how the relationship builds. You introduce yourself to a patient and their family as a hospitalist and they’re thinking, “Who the heck are you?” For a few seconds, it’s like meeting someone on a blind date. And when they’re discharged, they tell you they had a pleasant experience and they appreciate your help. It’s a courtship at a rapid pace.

Q: What do you consider to be your biggest challenge?

A: Recruitment; the administration asking us to take on more responsibilities; burnout. … We’re a typical hospitalist program; I think the problems are pretty universal.

Q: How do you address those challenges?

A: As medical director, you’re always navigating political and personal minefields. It comes back to developing relationships. The only way to earn goodwill is to give and provide service. That’s a problem some hospitalist programs run into. They want to instantly demand respect. You can’t demand it; you have to earn it. Sometimes hospitalists feel dumped on. Those are opportunities … to provide service in a willing and positive way instead of complaining. I’m not saying you have to be a whipping boy, but there are times when you have to give a little to get a little. That’s where the wisdom of the medical director comes in and sets the whole tone.

Q: What’s ahead for the academic side of your career?

A: We’re considering the possibility of starting a family practice fellowship program for attending residents who finish but want to go into the field of hospital medicine and want additional training. It’s not a done deal, but it’s an exciting possibility.

Q: How so?

A: Every medical director says they have a hard time recruiting. One way we can help solve the problem is by producing more hospitalists. We can’t just complain. We have to increase the pool of professionals interested in our model, train them, and get them integrated into our system.

Q: What advice would you give a student who is considering going that route?

A: You have to be a good communicator, you have to enjoy taking care of very sick people, and you have to enjoy solving very complex problems. You can’t just do it for the lifestyle. If you do, you won’t be happy in the long run. If I ask a medical student or resident why they want to be a hospitalist and they say, “I like the one-week-on, one-week-off schedule,” I tell them, “If that’s the reason you’re considering it, you really should reconsider.” TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

David Yu, MD, learned early on the value of being flexible. While attending Washington University in St. Louis, he found his calling when he changed his major from economics to biology. When the malpractice insurance crisis forced him to close his private practice, he embraced an opportunity to launch a program devoted to the “newfangled concept” of hospital medicine.

“I’m kind of like the accidental tourist,” says Dr. Yu, medical director of hospitalist services at the 372-bed Decatur Memorial Hospital in Decatur, Ill., and clinical assistant professor of family and community medicine at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine in Carbondale. “I didn’t really go to college with the mind-set of being a doctor, and when I became a doctor, there was no such thing as a hospitalist. … I went where the current took me and, fortunately, here I am.”

Question: What prompted the switch from economics to pre-med/biology?

Answer: When I got to the upper-level econ classes, I realized why the economy is the way it is: because nobody can understand how it works. My sister was in medical school. She really liked it and she talked me into it.

Q: You spent nine years in traditional practice. Why did you become a hospitalist?

A: In 2004, my malpractice insurance rate shot up 400% without any active lawsuits, so I had to close my practice. I had the choice of joining another traditional group, or Decatur (Memorial Hospital) was starting a new hospitalist program. To quote “The Godfather,” they made me an offer I couldn’t refuse.

Q: How did your experience in traditional practice prepare you for your role as a hospitalist?

A: I had been surrounded by incredible specialists. I saw how they interacted with me and how they treated my patients. As hospitalists, we are serving our patients, but really our clientele is the physicians we admit for. When I made the switch, I really had an idea of how a hospitalist should serve traditional practice.

Q: What is that service model?

A: It comes down to what I call the three A’s: You have to be available, you have to be able, and you have to be amicable. One of the problems in our field is a lot of hospitalists complain they’re treated like residents. They say they don’t get respect. They feel mistreated. That’s the wrong attitude. You can’t just ask for respect or demand it. You have to develop relationships.

Q: When Decatur’s hospitalist program started, you were on your own. Now there are seven physicians, two physician assistants, and a practice manager. How rewarding has it been to see it grow?

We have to find ways to help hospitalists take more ownership in their patients and their program. ... With our schedule, you can’t pawn off your responsibility to the nocturnist or the weekend guy.

—David Yu, MD, Decatur (Ill.)

Memorial Hospital

A: It’s been very rewarding. I’m honored to have been chosen as a member of Team Hospitalist, and I’m honored to be a committee member for SHM’s Non-Physician Provider Committee. Those are personal honors, but they are reflections on the success of the program. It’s an honor for the entire Decatur Memorial Hospital, and the administration, that a program started four and a half years ago, indirectly, has received national recognition.

Q: You implemented a one-week-on, one-week-off schedule for your hospitalists as a way to decrease signouts. How did that come about?

A: Signouts have been the bane of medical mistakes. Instead of having signouts twice a day, we have one physician on call for that entire week for his or her patients. It’s patient-centric versus schedule-centric. Physicians leave the hospital when their work is done, instead of looking at the clock and waiting to sign out at a certain time like a factory worker. It treats hospitalists not as shift workers but as attending physicians. It gives them due respect that they can manage their own patients responsibly.

Q: Do you think the schedule improves the quality of patient care?

A: The continuity of care is incredible. If you are admitted and discharged between Mondays, you have one hospitalist in charge of your entire case, instead of multiple physicians being on call for you. That increases patient satisfaction, reduces medical errors, and eliminates the need for unnecessary tests when new physicians take over. I’m also a huge believer that scheduling brings out the best and worst in hospitalists.

Q: How does it bring out the best in them?

A: As medical directors, we have to find ways to help hospitalists take more ownership in their patients and their program. If they’re thinking, “My shift is ending and I’m going to be off and I can hand this issue off to the next doctor,” that can have a tremendous effect on the quality of care and the way a hospitalist delivers medicine. With our schedule, you can’t pawn off your responsibility to the nocturnist or the weekend guy. … If something goes wrong or if the ball gets dropped, there’s no one else to blame it on.

Q: You developed a system at Decatur through which patient discharge summaries are sent electronically to primary-care physicians, often before the patient leaves the hospital. Have the primaries been receptive?

A: Absolutely. Communication is the mother’s milk of hospitalists. Some hospitalist programs are very large, they’re very busy, or there’s no incentive for them to do this because they’re the only game in town. But I practice in a mid-size community and I know all of these doctors. My reputation is my bond. I have to provide good service.

Q: What do you enjoy most about your role as a hospitalist?

A: I love solving problems for a patient. I also love how the relationship builds. You introduce yourself to a patient and their family as a hospitalist and they’re thinking, “Who the heck are you?” For a few seconds, it’s like meeting someone on a blind date. And when they’re discharged, they tell you they had a pleasant experience and they appreciate your help. It’s a courtship at a rapid pace.

Q: What do you consider to be your biggest challenge?

A: Recruitment; the administration asking us to take on more responsibilities; burnout. … We’re a typical hospitalist program; I think the problems are pretty universal.

Q: How do you address those challenges?

A: As medical director, you’re always navigating political and personal minefields. It comes back to developing relationships. The only way to earn goodwill is to give and provide service. That’s a problem some hospitalist programs run into. They want to instantly demand respect. You can’t demand it; you have to earn it. Sometimes hospitalists feel dumped on. Those are opportunities … to provide service in a willing and positive way instead of complaining. I’m not saying you have to be a whipping boy, but there are times when you have to give a little to get a little. That’s where the wisdom of the medical director comes in and sets the whole tone.

Q: What’s ahead for the academic side of your career?

A: We’re considering the possibility of starting a family practice fellowship program for attending residents who finish but want to go into the field of hospital medicine and want additional training. It’s not a done deal, but it’s an exciting possibility.

Q: How so?

A: Every medical director says they have a hard time recruiting. One way we can help solve the problem is by producing more hospitalists. We can’t just complain. We have to increase the pool of professionals interested in our model, train them, and get them integrated into our system.

Q: What advice would you give a student who is considering going that route?

A: You have to be a good communicator, you have to enjoy taking care of very sick people, and you have to enjoy solving very complex problems. You can’t just do it for the lifestyle. If you do, you won’t be happy in the long run. If I ask a medical student or resident why they want to be a hospitalist and they say, “I like the one-week-on, one-week-off schedule,” I tell them, “If that’s the reason you’re considering it, you really should reconsider.” TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Palliative-Care Payment

Many hospitalists provide palliative-care services to patients at the request of physicians within their own groups or from other specialists. Varying factors affect how hospitalists report these services—namely, the nature of the request and the type of service provided. Palliative-care programs can be quite costly as they involve several team members and a substantial amount of time delivering these services. Capturing services appropriately and obtaining reimbursement to help continue program initiatives is pertinent.

Nature of the Request

Members of a palliative-care team often are called on to provide management options to assist in reducing pain and suffering associated with both terminal and nonterminal disease, thereby improving a patient’s quality of life. When a palliative-care specialist is asked to provide an opinion or advice, the initial service could qualify as a consultation. However, all requirements must be met in order to report the service as an inpatient consultation (codes 99251-99255).

There must be a written request from a qualified healthcare provider involved in the patient’s care (e.g., a physician, resident, or nurse practitioner). In the inpatient setting, this request can be documented as a physician order or in the assessment of the requesting provider’s progress note. Standing orders for consultation are not permitted. Ideally, the requesting provider should identify the reason for a consult to support the medical necessity of the service.

Additionally, the palliative-care physician renders and documents the service, then reports findings to the requesting physician. The consultant’s required written report does not have to be sent separately to the requesting physician. Because the requesting physician and the consultant share a common medical record in an inpatient setting, the consultant’s inpatient progress note suffices the “written report” requirement.

One concern about billing consultations involves the nature of the request. If the requesting physician documents the need for an opinion or advice from the palliative-care specialist, the service can be reported as a consultation. If, however, the request states consult for “medical management” or “palliative management,” it’s less likely that payors will consider the service a consultation. In the latter situation, it appears as if the requesting physician is not seeking an opinion or advice from the consultant to incorporate into his own plan of care for the patient and would rather the consultant take over that portion of patient care.

Recently revised billing policies prevent the consultant from billing consults under these circumstances. Without a sufficient request for consultation, the palliative-care specialist can only report “subsequent” hospital care services.1 Language that better supports the consultative nature of the request is:

- Consult for an opinion or advice on palliative measures;

- Consult for evaluation of palliative options; and

- Consult palliative care for treatment options.

Proper Documentation

The requesting physician can be in the same or different provider group as the consultant. The consultant must possess expertise in an area beyond that of the requesting provider. Because the specialty designation for most hospitalists is internal medicine, palliative-care claims could be scrutinized more closely. This does not necessarily occur when the requesting provider has a different two-digit specialty designation (e.g., internal medicine and gastroenterology).2 Scrutiny is more likely to occur when the requesting provider has the same internal-medicine designation as the palliative-care consultant, even if they are in different provider groups.

Payor concern escalates when physicians of the same designated specialty submit claims for the same patient on the same date. Having different primary diagnosis codes attached to each visit level does not necessarily help. The payor is likely to deny the second claim received, pending a review of documentation. If this happens, the provider who received the denial should submit a copy of both progress notes for the date in question. Hopefully, the distinction between the services is demonstrated in the documentation.

Service Type

Palliative services might involve obtaining and documenting the standard key components for visit-level selection: history, exam, and medical decision-making.3 However, the palliative-care specialist might spend more time providing counseling or coordination of care for a patient and family. When this occurs, the palliative-care specialist should not forget about the guidelines for reporting time-based services.4 Inpatient services may be reported on the basis of time, as long as a face-to-face service between the provider and the patient occurs. Consider the total time spent face to face with the patient, and the time spent obtaining, discussing, and coordinating patient care, while you are in the patient’s unit or floor.

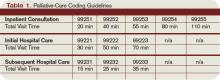

As a reminder, document the total time, the amount of time spent counseling, and the details of discussion and coordination. The physician may count the time spent counseling the patient’s family regarding the treatment and care, as long as the focus is not emotional support for the family, the meeting takes place in the patient’s unit or floor, and the patient is present, unless there is medically supported reason for which the patient is unable to participate (e.g., cognitive impairment). The palliative-care specialist can then select the visit level based on time.5 (See Table 1, above.) TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26, Section 10.8. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

5. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2008.

Many hospitalists provide palliative-care services to patients at the request of physicians within their own groups or from other specialists. Varying factors affect how hospitalists report these services—namely, the nature of the request and the type of service provided. Palliative-care programs can be quite costly as they involve several team members and a substantial amount of time delivering these services. Capturing services appropriately and obtaining reimbursement to help continue program initiatives is pertinent.

Nature of the Request

Members of a palliative-care team often are called on to provide management options to assist in reducing pain and suffering associated with both terminal and nonterminal disease, thereby improving a patient’s quality of life. When a palliative-care specialist is asked to provide an opinion or advice, the initial service could qualify as a consultation. However, all requirements must be met in order to report the service as an inpatient consultation (codes 99251-99255).

There must be a written request from a qualified healthcare provider involved in the patient’s care (e.g., a physician, resident, or nurse practitioner). In the inpatient setting, this request can be documented as a physician order or in the assessment of the requesting provider’s progress note. Standing orders for consultation are not permitted. Ideally, the requesting provider should identify the reason for a consult to support the medical necessity of the service.

Additionally, the palliative-care physician renders and documents the service, then reports findings to the requesting physician. The consultant’s required written report does not have to be sent separately to the requesting physician. Because the requesting physician and the consultant share a common medical record in an inpatient setting, the consultant’s inpatient progress note suffices the “written report” requirement.

One concern about billing consultations involves the nature of the request. If the requesting physician documents the need for an opinion or advice from the palliative-care specialist, the service can be reported as a consultation. If, however, the request states consult for “medical management” or “palliative management,” it’s less likely that payors will consider the service a consultation. In the latter situation, it appears as if the requesting physician is not seeking an opinion or advice from the consultant to incorporate into his own plan of care for the patient and would rather the consultant take over that portion of patient care.

Recently revised billing policies prevent the consultant from billing consults under these circumstances. Without a sufficient request for consultation, the palliative-care specialist can only report “subsequent” hospital care services.1 Language that better supports the consultative nature of the request is:

- Consult for an opinion or advice on palliative measures;

- Consult for evaluation of palliative options; and

- Consult palliative care for treatment options.

Proper Documentation

The requesting physician can be in the same or different provider group as the consultant. The consultant must possess expertise in an area beyond that of the requesting provider. Because the specialty designation for most hospitalists is internal medicine, palliative-care claims could be scrutinized more closely. This does not necessarily occur when the requesting provider has a different two-digit specialty designation (e.g., internal medicine and gastroenterology).2 Scrutiny is more likely to occur when the requesting provider has the same internal-medicine designation as the palliative-care consultant, even if they are in different provider groups.

Payor concern escalates when physicians of the same designated specialty submit claims for the same patient on the same date. Having different primary diagnosis codes attached to each visit level does not necessarily help. The payor is likely to deny the second claim received, pending a review of documentation. If this happens, the provider who received the denial should submit a copy of both progress notes for the date in question. Hopefully, the distinction between the services is demonstrated in the documentation.

Service Type

Palliative services might involve obtaining and documenting the standard key components for visit-level selection: history, exam, and medical decision-making.3 However, the palliative-care specialist might spend more time providing counseling or coordination of care for a patient and family. When this occurs, the palliative-care specialist should not forget about the guidelines for reporting time-based services.4 Inpatient services may be reported on the basis of time, as long as a face-to-face service between the provider and the patient occurs. Consider the total time spent face to face with the patient, and the time spent obtaining, discussing, and coordinating patient care, while you are in the patient’s unit or floor.

As a reminder, document the total time, the amount of time spent counseling, and the details of discussion and coordination. The physician may count the time spent counseling the patient’s family regarding the treatment and care, as long as the focus is not emotional support for the family, the meeting takes place in the patient’s unit or floor, and the patient is present, unless there is medically supported reason for which the patient is unable to participate (e.g., cognitive impairment). The palliative-care specialist can then select the visit level based on time.5 (See Table 1, above.) TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26, Section 10.8. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

5. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2008.

Many hospitalists provide palliative-care services to patients at the request of physicians within their own groups or from other specialists. Varying factors affect how hospitalists report these services—namely, the nature of the request and the type of service provided. Palliative-care programs can be quite costly as they involve several team members and a substantial amount of time delivering these services. Capturing services appropriately and obtaining reimbursement to help continue program initiatives is pertinent.

Nature of the Request

Members of a palliative-care team often are called on to provide management options to assist in reducing pain and suffering associated with both terminal and nonterminal disease, thereby improving a patient’s quality of life. When a palliative-care specialist is asked to provide an opinion or advice, the initial service could qualify as a consultation. However, all requirements must be met in order to report the service as an inpatient consultation (codes 99251-99255).

There must be a written request from a qualified healthcare provider involved in the patient’s care (e.g., a physician, resident, or nurse practitioner). In the inpatient setting, this request can be documented as a physician order or in the assessment of the requesting provider’s progress note. Standing orders for consultation are not permitted. Ideally, the requesting provider should identify the reason for a consult to support the medical necessity of the service.

Additionally, the palliative-care physician renders and documents the service, then reports findings to the requesting physician. The consultant’s required written report does not have to be sent separately to the requesting physician. Because the requesting physician and the consultant share a common medical record in an inpatient setting, the consultant’s inpatient progress note suffices the “written report” requirement.

One concern about billing consultations involves the nature of the request. If the requesting physician documents the need for an opinion or advice from the palliative-care specialist, the service can be reported as a consultation. If, however, the request states consult for “medical management” or “palliative management,” it’s less likely that payors will consider the service a consultation. In the latter situation, it appears as if the requesting physician is not seeking an opinion or advice from the consultant to incorporate into his own plan of care for the patient and would rather the consultant take over that portion of patient care.

Recently revised billing policies prevent the consultant from billing consults under these circumstances. Without a sufficient request for consultation, the palliative-care specialist can only report “subsequent” hospital care services.1 Language that better supports the consultative nature of the request is:

- Consult for an opinion or advice on palliative measures;

- Consult for evaluation of palliative options; and

- Consult palliative care for treatment options.

Proper Documentation

The requesting physician can be in the same or different provider group as the consultant. The consultant must possess expertise in an area beyond that of the requesting provider. Because the specialty designation for most hospitalists is internal medicine, palliative-care claims could be scrutinized more closely. This does not necessarily occur when the requesting provider has a different two-digit specialty designation (e.g., internal medicine and gastroenterology).2 Scrutiny is more likely to occur when the requesting provider has the same internal-medicine designation as the palliative-care consultant, even if they are in different provider groups.

Payor concern escalates when physicians of the same designated specialty submit claims for the same patient on the same date. Having different primary diagnosis codes attached to each visit level does not necessarily help. The payor is likely to deny the second claim received, pending a review of documentation. If this happens, the provider who received the denial should submit a copy of both progress notes for the date in question. Hopefully, the distinction between the services is demonstrated in the documentation.

Service Type

Palliative services might involve obtaining and documenting the standard key components for visit-level selection: history, exam, and medical decision-making.3 However, the palliative-care specialist might spend more time providing counseling or coordination of care for a patient and family. When this occurs, the palliative-care specialist should not forget about the guidelines for reporting time-based services.4 Inpatient services may be reported on the basis of time, as long as a face-to-face service between the provider and the patient occurs. Consider the total time spent face to face with the patient, and the time spent obtaining, discussing, and coordinating patient care, while you are in the patient’s unit or floor.