User login

Epilepsy

In epilepsy, brain-responsive stimulation passes long-term tests

Two new long-term studies, one an extension trial and the other an analysis of real-world experience, show that Both studies showed that the benefit from the devices increased over time.

That accruing benefit may be because of improved protocols as clinicians gain experience with the device or because of network remodeling that occurs over time as seizures are controlled. “I think it’s both,” said Martha Morrell, MD, a clinical professor of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University and chief medical officer at NeuroPace, the company that has marketed the device since it gained FDA approval in 2013.

In both studies, the slope of improvement over time was similar, but the real-world study showed greater improvement at the beginning of treatment. “I think the slopes represent physiological changes, but the fact that [the real-world study] starts with better outcomes is, I think, directly attributable to learning. When the long-term study was started in 2004, this had never been done before, and we had to make a highly educated guess about what we should do, and the initial stimulatory parameters were programmed in a way that’s very similar to what was used for movement disorders,” Dr. Morrell said in an interview.

The long-term treatment study appeared online July 20 in the journal Neurology, while the real-world analysis was published July 13 in Epilepsia.

An alternative option

Medications can effectively treat some seizures, but 30%-40% of patients must turn to other options for control. Surgery can sometimes be curative, but is not suitable for some patients. Other stimulation devices include vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which sends pulses from a chest implant to the vagus nerve, reducing epileptic attacks through an unknown mechanism. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) places electrodes that deliver stimulation to the anterior nucleus of the thalamus, which can spread initially localized seizures.

The RNS device consists of a neurostimulator implanted cranially and connected to leads that are placed based on the individual patient’s seizure focus or foci. It also continuously monitors brain activity and delivers stimulation only when its signal suggests the beginning of a seizure.

That capacity for recording is a key benefit because the information can be stored and analyzed, according to Vikram Rao, MD, PhD, a coinvestigator in the real-world trial and an associate professor and the epilepsy division chief at the University of California, San Francisco, which was one of the trial centers. “You know more precisely than we previously did how many seizures a patient is having. Many of our patients are not able to quantify their seizures with perfect accuracy, so we’re better quantifying their seizure burden,” Dr. Rao said in an interview.

The ability to monitor patients can also improve clinical management. Dr. Morrell recounted an elderly patient who for many years has driven 5 hours for appointments. Recently she was able to review his data from the RNS System remotely. She determined that he was doing fine and, after a telephone consultation, told him he didn’t need to come in for a scheduled visit.

Real-world analysis

In the real-world analysis, researchers led by Babak Razavi, PhD, and Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University conducted a chart review of 150 patients at eight centers who underwent treatment with the RNS system between 2013 and 2018. All patients were followed at least 1 year, with a mean of 2.3 years. Patients had a median of 7.7 disabling seizures per month. The mean value was 52 and the numbers ranged from 0.1 to 3,000. A total of 60% had abnormal brain MRI findings.

At 1 year, subjects achieved a mean 67% decrease in seizure frequency (interquartile range, 50%-94%). At 2 years, that grew to 77%; at 3 or more years, 84%. There was no significant difference in seizure reduction at 1 year according to age, age at epilepsy onset, duration of epilepsy, location of seizure foci, presence of brain MRI abnormalities, prior intracranial monitoring, prior epilepsy surgery, or prior VNS treatment. When patients who underwent a resection at the time of RNS placement were excluded, the results were similar. There were no significant differences in outcome by center.

A total of 11.3% of patients experienced a device-related serious adverse event, and 4% developed infections. The rate of infection was not significantly different between patients who had the neurostimulator and leads implanted alone (3.0%) and patients who had intracranial EEG diagnostic monitoring (ICM) electrodes removed at the same time (6.1%; P = .38).

Although about one-third of the patients who started the long-term study dropped out before completion, most were because the participants moved away from treatment centers, according to Dr. Morrell, and other evidence points squarely to patient satisfaction. “At the end of the battery’s longevity, the neurostimulator needs to be replaced. It’s an outpatient, 45-minute procedure. Over 90% of patients chose to have it replaced. It’s not the answer for everybody, but the substantial majority of patients choose to continue,” she said.

Extension trial

The open-label extension trial, led by Dileep Nair, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and Dr. Morrell, followed 230 of the 256 patients who participated in 2-year phase 3 study or feasibility studies, extending device usage to 9 years. A total of 162 completed follow-up (mean, 7.5 years). The median reduction of seizure frequency was 58% at the end of year 3, and 75% by year 9 (P < .0001; Wilcoxon signed rank). Although patient population enrichment could have explained this observation, other analyses confirmed that the improvement was real.

Nearly 75% had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency; 35% had a 90% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Some patients (18.4%) had at least a full year with no seizures, and 62% who had a 1-year seizure-free period experienced no seizures at the latest follow-up. Overall, 21% had no seizures in the last 6 months of follow-up.

For those with a seizure-free period of more than 1 year, the average duration was 3.2 years (range, 1.04-9.6 years). There was no difference in response among patients based on previous antiseizure medication use or previous epilepsy surgery, VNS treatment, or intracranial monitoring, and there were no differences by patient age at enrollment, age of seizure onset, brain imaging abnormality, seizure onset locality, or number of foci.

The researchers noted improvement in overall Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory–89 scores at 1 year (mean, +3.2; P < .0001), which continued through year 9 (mean, +1.9; P < .05). Improvements were also seen in epilepsy targeted (mean, +4.5; P < .001) and cognitive domains (mean, +2.5; P = .005). Risk of infection was 4.1% per procedure, and 12.1% of subjects overall experienced a serious device-related implant infection. Of 35 infections, 16 led to device removal.

The extension study was funded by NeuroPace. NeuroPace supported data entry and institutional review board submission for the real-world trial. Dr. Morrell owns stock and is an employee of NeuroPace. Dr Rao has received support from and/or consulted for NeuroPace.

SOURCE: Nair DR et al. Neurology. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010154. Razavi B et al. Epilepsia. 2020 Jul 13. doi: 10.1111/epi.16593.

Two new long-term studies, one an extension trial and the other an analysis of real-world experience, show that Both studies showed that the benefit from the devices increased over time.

That accruing benefit may be because of improved protocols as clinicians gain experience with the device or because of network remodeling that occurs over time as seizures are controlled. “I think it’s both,” said Martha Morrell, MD, a clinical professor of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University and chief medical officer at NeuroPace, the company that has marketed the device since it gained FDA approval in 2013.

In both studies, the slope of improvement over time was similar, but the real-world study showed greater improvement at the beginning of treatment. “I think the slopes represent physiological changes, but the fact that [the real-world study] starts with better outcomes is, I think, directly attributable to learning. When the long-term study was started in 2004, this had never been done before, and we had to make a highly educated guess about what we should do, and the initial stimulatory parameters were programmed in a way that’s very similar to what was used for movement disorders,” Dr. Morrell said in an interview.

The long-term treatment study appeared online July 20 in the journal Neurology, while the real-world analysis was published July 13 in Epilepsia.

An alternative option

Medications can effectively treat some seizures, but 30%-40% of patients must turn to other options for control. Surgery can sometimes be curative, but is not suitable for some patients. Other stimulation devices include vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which sends pulses from a chest implant to the vagus nerve, reducing epileptic attacks through an unknown mechanism. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) places electrodes that deliver stimulation to the anterior nucleus of the thalamus, which can spread initially localized seizures.

The RNS device consists of a neurostimulator implanted cranially and connected to leads that are placed based on the individual patient’s seizure focus or foci. It also continuously monitors brain activity and delivers stimulation only when its signal suggests the beginning of a seizure.

That capacity for recording is a key benefit because the information can be stored and analyzed, according to Vikram Rao, MD, PhD, a coinvestigator in the real-world trial and an associate professor and the epilepsy division chief at the University of California, San Francisco, which was one of the trial centers. “You know more precisely than we previously did how many seizures a patient is having. Many of our patients are not able to quantify their seizures with perfect accuracy, so we’re better quantifying their seizure burden,” Dr. Rao said in an interview.

The ability to monitor patients can also improve clinical management. Dr. Morrell recounted an elderly patient who for many years has driven 5 hours for appointments. Recently she was able to review his data from the RNS System remotely. She determined that he was doing fine and, after a telephone consultation, told him he didn’t need to come in for a scheduled visit.

Real-world analysis

In the real-world analysis, researchers led by Babak Razavi, PhD, and Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University conducted a chart review of 150 patients at eight centers who underwent treatment with the RNS system between 2013 and 2018. All patients were followed at least 1 year, with a mean of 2.3 years. Patients had a median of 7.7 disabling seizures per month. The mean value was 52 and the numbers ranged from 0.1 to 3,000. A total of 60% had abnormal brain MRI findings.

At 1 year, subjects achieved a mean 67% decrease in seizure frequency (interquartile range, 50%-94%). At 2 years, that grew to 77%; at 3 or more years, 84%. There was no significant difference in seizure reduction at 1 year according to age, age at epilepsy onset, duration of epilepsy, location of seizure foci, presence of brain MRI abnormalities, prior intracranial monitoring, prior epilepsy surgery, or prior VNS treatment. When patients who underwent a resection at the time of RNS placement were excluded, the results were similar. There were no significant differences in outcome by center.

A total of 11.3% of patients experienced a device-related serious adverse event, and 4% developed infections. The rate of infection was not significantly different between patients who had the neurostimulator and leads implanted alone (3.0%) and patients who had intracranial EEG diagnostic monitoring (ICM) electrodes removed at the same time (6.1%; P = .38).

Although about one-third of the patients who started the long-term study dropped out before completion, most were because the participants moved away from treatment centers, according to Dr. Morrell, and other evidence points squarely to patient satisfaction. “At the end of the battery’s longevity, the neurostimulator needs to be replaced. It’s an outpatient, 45-minute procedure. Over 90% of patients chose to have it replaced. It’s not the answer for everybody, but the substantial majority of patients choose to continue,” she said.

Extension trial

The open-label extension trial, led by Dileep Nair, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and Dr. Morrell, followed 230 of the 256 patients who participated in 2-year phase 3 study or feasibility studies, extending device usage to 9 years. A total of 162 completed follow-up (mean, 7.5 years). The median reduction of seizure frequency was 58% at the end of year 3, and 75% by year 9 (P < .0001; Wilcoxon signed rank). Although patient population enrichment could have explained this observation, other analyses confirmed that the improvement was real.

Nearly 75% had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency; 35% had a 90% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Some patients (18.4%) had at least a full year with no seizures, and 62% who had a 1-year seizure-free period experienced no seizures at the latest follow-up. Overall, 21% had no seizures in the last 6 months of follow-up.

For those with a seizure-free period of more than 1 year, the average duration was 3.2 years (range, 1.04-9.6 years). There was no difference in response among patients based on previous antiseizure medication use or previous epilepsy surgery, VNS treatment, or intracranial monitoring, and there were no differences by patient age at enrollment, age of seizure onset, brain imaging abnormality, seizure onset locality, or number of foci.

The researchers noted improvement in overall Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory–89 scores at 1 year (mean, +3.2; P < .0001), which continued through year 9 (mean, +1.9; P < .05). Improvements were also seen in epilepsy targeted (mean, +4.5; P < .001) and cognitive domains (mean, +2.5; P = .005). Risk of infection was 4.1% per procedure, and 12.1% of subjects overall experienced a serious device-related implant infection. Of 35 infections, 16 led to device removal.

The extension study was funded by NeuroPace. NeuroPace supported data entry and institutional review board submission for the real-world trial. Dr. Morrell owns stock and is an employee of NeuroPace. Dr Rao has received support from and/or consulted for NeuroPace.

SOURCE: Nair DR et al. Neurology. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010154. Razavi B et al. Epilepsia. 2020 Jul 13. doi: 10.1111/epi.16593.

Two new long-term studies, one an extension trial and the other an analysis of real-world experience, show that Both studies showed that the benefit from the devices increased over time.

That accruing benefit may be because of improved protocols as clinicians gain experience with the device or because of network remodeling that occurs over time as seizures are controlled. “I think it’s both,” said Martha Morrell, MD, a clinical professor of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University and chief medical officer at NeuroPace, the company that has marketed the device since it gained FDA approval in 2013.

In both studies, the slope of improvement over time was similar, but the real-world study showed greater improvement at the beginning of treatment. “I think the slopes represent physiological changes, but the fact that [the real-world study] starts with better outcomes is, I think, directly attributable to learning. When the long-term study was started in 2004, this had never been done before, and we had to make a highly educated guess about what we should do, and the initial stimulatory parameters were programmed in a way that’s very similar to what was used for movement disorders,” Dr. Morrell said in an interview.

The long-term treatment study appeared online July 20 in the journal Neurology, while the real-world analysis was published July 13 in Epilepsia.

An alternative option

Medications can effectively treat some seizures, but 30%-40% of patients must turn to other options for control. Surgery can sometimes be curative, but is not suitable for some patients. Other stimulation devices include vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which sends pulses from a chest implant to the vagus nerve, reducing epileptic attacks through an unknown mechanism. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) places electrodes that deliver stimulation to the anterior nucleus of the thalamus, which can spread initially localized seizures.

The RNS device consists of a neurostimulator implanted cranially and connected to leads that are placed based on the individual patient’s seizure focus or foci. It also continuously monitors brain activity and delivers stimulation only when its signal suggests the beginning of a seizure.

That capacity for recording is a key benefit because the information can be stored and analyzed, according to Vikram Rao, MD, PhD, a coinvestigator in the real-world trial and an associate professor and the epilepsy division chief at the University of California, San Francisco, which was one of the trial centers. “You know more precisely than we previously did how many seizures a patient is having. Many of our patients are not able to quantify their seizures with perfect accuracy, so we’re better quantifying their seizure burden,” Dr. Rao said in an interview.

The ability to monitor patients can also improve clinical management. Dr. Morrell recounted an elderly patient who for many years has driven 5 hours for appointments. Recently she was able to review his data from the RNS System remotely. She determined that he was doing fine and, after a telephone consultation, told him he didn’t need to come in for a scheduled visit.

Real-world analysis

In the real-world analysis, researchers led by Babak Razavi, PhD, and Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University conducted a chart review of 150 patients at eight centers who underwent treatment with the RNS system between 2013 and 2018. All patients were followed at least 1 year, with a mean of 2.3 years. Patients had a median of 7.7 disabling seizures per month. The mean value was 52 and the numbers ranged from 0.1 to 3,000. A total of 60% had abnormal brain MRI findings.

At 1 year, subjects achieved a mean 67% decrease in seizure frequency (interquartile range, 50%-94%). At 2 years, that grew to 77%; at 3 or more years, 84%. There was no significant difference in seizure reduction at 1 year according to age, age at epilepsy onset, duration of epilepsy, location of seizure foci, presence of brain MRI abnormalities, prior intracranial monitoring, prior epilepsy surgery, or prior VNS treatment. When patients who underwent a resection at the time of RNS placement were excluded, the results were similar. There were no significant differences in outcome by center.

A total of 11.3% of patients experienced a device-related serious adverse event, and 4% developed infections. The rate of infection was not significantly different between patients who had the neurostimulator and leads implanted alone (3.0%) and patients who had intracranial EEG diagnostic monitoring (ICM) electrodes removed at the same time (6.1%; P = .38).

Although about one-third of the patients who started the long-term study dropped out before completion, most were because the participants moved away from treatment centers, according to Dr. Morrell, and other evidence points squarely to patient satisfaction. “At the end of the battery’s longevity, the neurostimulator needs to be replaced. It’s an outpatient, 45-minute procedure. Over 90% of patients chose to have it replaced. It’s not the answer for everybody, but the substantial majority of patients choose to continue,” she said.

Extension trial

The open-label extension trial, led by Dileep Nair, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and Dr. Morrell, followed 230 of the 256 patients who participated in 2-year phase 3 study or feasibility studies, extending device usage to 9 years. A total of 162 completed follow-up (mean, 7.5 years). The median reduction of seizure frequency was 58% at the end of year 3, and 75% by year 9 (P < .0001; Wilcoxon signed rank). Although patient population enrichment could have explained this observation, other analyses confirmed that the improvement was real.

Nearly 75% had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency; 35% had a 90% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Some patients (18.4%) had at least a full year with no seizures, and 62% who had a 1-year seizure-free period experienced no seizures at the latest follow-up. Overall, 21% had no seizures in the last 6 months of follow-up.

For those with a seizure-free period of more than 1 year, the average duration was 3.2 years (range, 1.04-9.6 years). There was no difference in response among patients based on previous antiseizure medication use or previous epilepsy surgery, VNS treatment, or intracranial monitoring, and there were no differences by patient age at enrollment, age of seizure onset, brain imaging abnormality, seizure onset locality, or number of foci.

The researchers noted improvement in overall Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory–89 scores at 1 year (mean, +3.2; P < .0001), which continued through year 9 (mean, +1.9; P < .05). Improvements were also seen in epilepsy targeted (mean, +4.5; P < .001) and cognitive domains (mean, +2.5; P = .005). Risk of infection was 4.1% per procedure, and 12.1% of subjects overall experienced a serious device-related implant infection. Of 35 infections, 16 led to device removal.

The extension study was funded by NeuroPace. NeuroPace supported data entry and institutional review board submission for the real-world trial. Dr. Morrell owns stock and is an employee of NeuroPace. Dr Rao has received support from and/or consulted for NeuroPace.

SOURCE: Nair DR et al. Neurology. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010154. Razavi B et al. Epilepsia. 2020 Jul 13. doi: 10.1111/epi.16593.

FROM EPILEPSIA AND FROM NEUROLOGY

Epilepsy after TBI linked to worse 12-month outcomes

findings from an analysis of a large, prospective database suggest. “We found that patients essentially have a 10-times greater risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy and seizures at 12 months [post injury] if the presenting Glasgow Coma Scale GCS) is less than 8,” said lead author John F. Burke, MD, PhD, University of California, San Francisco, in presenting the findings as part of the virtual annual meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

Assessing risk factors

While posttraumatic epilepsy represents an estimated 20% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy, many questions remain on those most at risk and on the long-term effects of posttraumatic epilepsy on TBI outcomes. To probe those issues, Dr. Burke and colleagues turned to the multicenter TRACK-TBI database, which has prospective, longitudinal data on more than 2,700 patients with traumatic brain injuries and is considered the largest source of prospective data on posttraumatic epilepsy.

Using the criteria of no previous epilepsy and having 12 months of follow-up, the team identified 1,493 patients with TBI. In addition, investigators identified 182 orthopedic controls (included and prospectively followed because they have injuries but not specifically head trauma) and 210 controls who are friends of the patients and who do not have injuries but allow researchers to control for socioeconomic and environmental factors.

Of the 1,493 patients with TBI, 41 (2.7%) were determined to have posttraumatic epilepsy, assessed according to a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke epilepsy screening questionnaire, which is designed to identify patients with posttraumatic epilepsy symptoms. There were no reports of epilepsy symptoms using the screening tool among the controls. Dr. Burke noted that the 2.7% was in agreement with historical reports.

In comparing patients with TBI who did and did not have posttraumatic epilepsy, no differences were observed in the groups in terms of gender, although there was a trend toward younger age among those with PTE (mean age, 35.4 years with posttraumatic injury vs. 41.5 without; P = .05).

A major risk factor for the development of posttraumatic epilepsy was presenting GCS scores. Among those with scores of less than 8, indicative of severe injury, the rate of posttraumatic epilepsy was 6% at 6 months and 12.5% at 12 months. In contrast, those with TBI presenting with GCS scores between 13 and 15, indicative of minor injury, had an incidence of posttraumatic epilepsy of 0.9% at 6 months and 1.4% at 12 months.

Imaging findings in the two groups showed that hemorrhage detected on CT imaging was associated with a significantly higher risk for posttraumatic epilepsy (P < .001).

“The main takeaway is that any hemorrhage in the brain is a major risk factor for developing seizures,” Dr. Burke said. “Whether it is subdural, epidural blood, subarachnoid or contusion, any blood confers a very [high] risk for developing seizures.”

Posttraumatic epilepsy was linked to poorer longer-term outcomes even for patients with lesser injury: Among those with TBI and GCS of 13-15, the mean Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) score at 12 months among those without posttraumatic epilepsy was 7, indicative of a good recovery with minor defects, whereas the mean GOSE score for those with PTE was 4.6, indicative of moderate to severe disability (P < .001).

“It was surprising to us that PTE-positive patients had a very significant decrease in GOSE, compared to PTE-negative patients,” Dr. Burke said. “There was a nearly 2-point drop in the GOSE and that was extremely significant.”

A multivariate analysis showed there was still a significant independent risk for a poor GOSE score with posttraumatic epilepsy after controlling for GCS score, head CT findings, and age (P < .001).

The authors also looked at mood outcomes using the Brief Symptom Inventory–18, which showed significant worse effect in those with posttraumatic epilepsy after multivariate adjustment (P = .01). Additionally, a highly significant worse effect in cognitive outcomes on the Rivermead cognitive metric was observed with posttraumatic epilepsy (P = .001).

“On all metrics tested, posttraumatic epilepsy worsened outcomes,” Dr. Burke said.

He noted that the study has some key limitations, including the 12-month follow-up. A previous study showed a linear increase in posttraumatic follow-up up to 30 years. “The fact that we found 41 patients at 12 months indicates there are probably more that are out there who are going to develop seizures, but because we don’t have the follow-up we can’t look at that.”

Although the screening questionnaires are effective, “the issue is these people are not being seen by an epileptologist or having scalp EEG done, and we need a more accurate way to do this,” he said. A new study, TRACK-TBI EPI, will address those limitations and a host of other issues with a 5-year follow-up.

Capturing the nuances of brain injury

Commenting on the study as a discussant, neurosurgeon Uzma Samadani, MD, PhD, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center and CentraCare in Minneapolis, suggested that the future work should focus on issues including the wide-ranging mechanisms that could explain the seizure activity.

“For example, it’s known that posttraumatic epilepsy or seizures can be triggered by abnormal conductivity due to multiple different mechanisms associated with brain injury, such as endocrine dysfunction, cortical-spreading depression, and many others,” said Dr. Samadani, who has been a researcher on the TRACK-TBI study.

Factors ranging from genetic differences to comorbid conditions such as alcoholism can play a role in brain injury susceptibility, Dr. Samadani added. Furthermore, outcome measures currently available simply may not capture the unknown nuances of brain injury.

“We have to ask, are these an all-or-none phenomena, or is aberrant electrical activity after brain injury a continuum of dysfunction?” Dr. Samadani speculated.

“I would caution that we are likely underestimating the non–easily measurable consequences of brain injury,” she said. “And the better we can quantitate susceptibility, classify the nature of injury and target acute management, the less posttraumatic epilepsy/aberrant electrical activity our patients will have.”

Dr. Burke and Dr. Samadani disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

findings from an analysis of a large, prospective database suggest. “We found that patients essentially have a 10-times greater risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy and seizures at 12 months [post injury] if the presenting Glasgow Coma Scale GCS) is less than 8,” said lead author John F. Burke, MD, PhD, University of California, San Francisco, in presenting the findings as part of the virtual annual meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

Assessing risk factors

While posttraumatic epilepsy represents an estimated 20% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy, many questions remain on those most at risk and on the long-term effects of posttraumatic epilepsy on TBI outcomes. To probe those issues, Dr. Burke and colleagues turned to the multicenter TRACK-TBI database, which has prospective, longitudinal data on more than 2,700 patients with traumatic brain injuries and is considered the largest source of prospective data on posttraumatic epilepsy.

Using the criteria of no previous epilepsy and having 12 months of follow-up, the team identified 1,493 patients with TBI. In addition, investigators identified 182 orthopedic controls (included and prospectively followed because they have injuries but not specifically head trauma) and 210 controls who are friends of the patients and who do not have injuries but allow researchers to control for socioeconomic and environmental factors.

Of the 1,493 patients with TBI, 41 (2.7%) were determined to have posttraumatic epilepsy, assessed according to a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke epilepsy screening questionnaire, which is designed to identify patients with posttraumatic epilepsy symptoms. There were no reports of epilepsy symptoms using the screening tool among the controls. Dr. Burke noted that the 2.7% was in agreement with historical reports.

In comparing patients with TBI who did and did not have posttraumatic epilepsy, no differences were observed in the groups in terms of gender, although there was a trend toward younger age among those with PTE (mean age, 35.4 years with posttraumatic injury vs. 41.5 without; P = .05).

A major risk factor for the development of posttraumatic epilepsy was presenting GCS scores. Among those with scores of less than 8, indicative of severe injury, the rate of posttraumatic epilepsy was 6% at 6 months and 12.5% at 12 months. In contrast, those with TBI presenting with GCS scores between 13 and 15, indicative of minor injury, had an incidence of posttraumatic epilepsy of 0.9% at 6 months and 1.4% at 12 months.

Imaging findings in the two groups showed that hemorrhage detected on CT imaging was associated with a significantly higher risk for posttraumatic epilepsy (P < .001).

“The main takeaway is that any hemorrhage in the brain is a major risk factor for developing seizures,” Dr. Burke said. “Whether it is subdural, epidural blood, subarachnoid or contusion, any blood confers a very [high] risk for developing seizures.”

Posttraumatic epilepsy was linked to poorer longer-term outcomes even for patients with lesser injury: Among those with TBI and GCS of 13-15, the mean Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) score at 12 months among those without posttraumatic epilepsy was 7, indicative of a good recovery with minor defects, whereas the mean GOSE score for those with PTE was 4.6, indicative of moderate to severe disability (P < .001).

“It was surprising to us that PTE-positive patients had a very significant decrease in GOSE, compared to PTE-negative patients,” Dr. Burke said. “There was a nearly 2-point drop in the GOSE and that was extremely significant.”

A multivariate analysis showed there was still a significant independent risk for a poor GOSE score with posttraumatic epilepsy after controlling for GCS score, head CT findings, and age (P < .001).

The authors also looked at mood outcomes using the Brief Symptom Inventory–18, which showed significant worse effect in those with posttraumatic epilepsy after multivariate adjustment (P = .01). Additionally, a highly significant worse effect in cognitive outcomes on the Rivermead cognitive metric was observed with posttraumatic epilepsy (P = .001).

“On all metrics tested, posttraumatic epilepsy worsened outcomes,” Dr. Burke said.

He noted that the study has some key limitations, including the 12-month follow-up. A previous study showed a linear increase in posttraumatic follow-up up to 30 years. “The fact that we found 41 patients at 12 months indicates there are probably more that are out there who are going to develop seizures, but because we don’t have the follow-up we can’t look at that.”

Although the screening questionnaires are effective, “the issue is these people are not being seen by an epileptologist or having scalp EEG done, and we need a more accurate way to do this,” he said. A new study, TRACK-TBI EPI, will address those limitations and a host of other issues with a 5-year follow-up.

Capturing the nuances of brain injury

Commenting on the study as a discussant, neurosurgeon Uzma Samadani, MD, PhD, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center and CentraCare in Minneapolis, suggested that the future work should focus on issues including the wide-ranging mechanisms that could explain the seizure activity.

“For example, it’s known that posttraumatic epilepsy or seizures can be triggered by abnormal conductivity due to multiple different mechanisms associated with brain injury, such as endocrine dysfunction, cortical-spreading depression, and many others,” said Dr. Samadani, who has been a researcher on the TRACK-TBI study.

Factors ranging from genetic differences to comorbid conditions such as alcoholism can play a role in brain injury susceptibility, Dr. Samadani added. Furthermore, outcome measures currently available simply may not capture the unknown nuances of brain injury.

“We have to ask, are these an all-or-none phenomena, or is aberrant electrical activity after brain injury a continuum of dysfunction?” Dr. Samadani speculated.

“I would caution that we are likely underestimating the non–easily measurable consequences of brain injury,” she said. “And the better we can quantitate susceptibility, classify the nature of injury and target acute management, the less posttraumatic epilepsy/aberrant electrical activity our patients will have.”

Dr. Burke and Dr. Samadani disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

findings from an analysis of a large, prospective database suggest. “We found that patients essentially have a 10-times greater risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy and seizures at 12 months [post injury] if the presenting Glasgow Coma Scale GCS) is less than 8,” said lead author John F. Burke, MD, PhD, University of California, San Francisco, in presenting the findings as part of the virtual annual meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

Assessing risk factors

While posttraumatic epilepsy represents an estimated 20% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy, many questions remain on those most at risk and on the long-term effects of posttraumatic epilepsy on TBI outcomes. To probe those issues, Dr. Burke and colleagues turned to the multicenter TRACK-TBI database, which has prospective, longitudinal data on more than 2,700 patients with traumatic brain injuries and is considered the largest source of prospective data on posttraumatic epilepsy.

Using the criteria of no previous epilepsy and having 12 months of follow-up, the team identified 1,493 patients with TBI. In addition, investigators identified 182 orthopedic controls (included and prospectively followed because they have injuries but not specifically head trauma) and 210 controls who are friends of the patients and who do not have injuries but allow researchers to control for socioeconomic and environmental factors.

Of the 1,493 patients with TBI, 41 (2.7%) were determined to have posttraumatic epilepsy, assessed according to a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke epilepsy screening questionnaire, which is designed to identify patients with posttraumatic epilepsy symptoms. There were no reports of epilepsy symptoms using the screening tool among the controls. Dr. Burke noted that the 2.7% was in agreement with historical reports.

In comparing patients with TBI who did and did not have posttraumatic epilepsy, no differences were observed in the groups in terms of gender, although there was a trend toward younger age among those with PTE (mean age, 35.4 years with posttraumatic injury vs. 41.5 without; P = .05).

A major risk factor for the development of posttraumatic epilepsy was presenting GCS scores. Among those with scores of less than 8, indicative of severe injury, the rate of posttraumatic epilepsy was 6% at 6 months and 12.5% at 12 months. In contrast, those with TBI presenting with GCS scores between 13 and 15, indicative of minor injury, had an incidence of posttraumatic epilepsy of 0.9% at 6 months and 1.4% at 12 months.

Imaging findings in the two groups showed that hemorrhage detected on CT imaging was associated with a significantly higher risk for posttraumatic epilepsy (P < .001).

“The main takeaway is that any hemorrhage in the brain is a major risk factor for developing seizures,” Dr. Burke said. “Whether it is subdural, epidural blood, subarachnoid or contusion, any blood confers a very [high] risk for developing seizures.”

Posttraumatic epilepsy was linked to poorer longer-term outcomes even for patients with lesser injury: Among those with TBI and GCS of 13-15, the mean Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) score at 12 months among those without posttraumatic epilepsy was 7, indicative of a good recovery with minor defects, whereas the mean GOSE score for those with PTE was 4.6, indicative of moderate to severe disability (P < .001).

“It was surprising to us that PTE-positive patients had a very significant decrease in GOSE, compared to PTE-negative patients,” Dr. Burke said. “There was a nearly 2-point drop in the GOSE and that was extremely significant.”

A multivariate analysis showed there was still a significant independent risk for a poor GOSE score with posttraumatic epilepsy after controlling for GCS score, head CT findings, and age (P < .001).

The authors also looked at mood outcomes using the Brief Symptom Inventory–18, which showed significant worse effect in those with posttraumatic epilepsy after multivariate adjustment (P = .01). Additionally, a highly significant worse effect in cognitive outcomes on the Rivermead cognitive metric was observed with posttraumatic epilepsy (P = .001).

“On all metrics tested, posttraumatic epilepsy worsened outcomes,” Dr. Burke said.

He noted that the study has some key limitations, including the 12-month follow-up. A previous study showed a linear increase in posttraumatic follow-up up to 30 years. “The fact that we found 41 patients at 12 months indicates there are probably more that are out there who are going to develop seizures, but because we don’t have the follow-up we can’t look at that.”

Although the screening questionnaires are effective, “the issue is these people are not being seen by an epileptologist or having scalp EEG done, and we need a more accurate way to do this,” he said. A new study, TRACK-TBI EPI, will address those limitations and a host of other issues with a 5-year follow-up.

Capturing the nuances of brain injury

Commenting on the study as a discussant, neurosurgeon Uzma Samadani, MD, PhD, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center and CentraCare in Minneapolis, suggested that the future work should focus on issues including the wide-ranging mechanisms that could explain the seizure activity.

“For example, it’s known that posttraumatic epilepsy or seizures can be triggered by abnormal conductivity due to multiple different mechanisms associated with brain injury, such as endocrine dysfunction, cortical-spreading depression, and many others,” said Dr. Samadani, who has been a researcher on the TRACK-TBI study.

Factors ranging from genetic differences to comorbid conditions such as alcoholism can play a role in brain injury susceptibility, Dr. Samadani added. Furthermore, outcome measures currently available simply may not capture the unknown nuances of brain injury.

“We have to ask, are these an all-or-none phenomena, or is aberrant electrical activity after brain injury a continuum of dysfunction?” Dr. Samadani speculated.

“I would caution that we are likely underestimating the non–easily measurable consequences of brain injury,” she said. “And the better we can quantitate susceptibility, classify the nature of injury and target acute management, the less posttraumatic epilepsy/aberrant electrical activity our patients will have.”

Dr. Burke and Dr. Samadani disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AANS 2020

FDA approves new treatment for Dravet syndrome

Dravet syndrome is a rare childhood-onset epilepsy characterized by frequent, drug-resistant convulsive seizures that may contribute to intellectual disability and impairments in motor control, behavior, and cognition, as well as an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Dravet syndrome takes a “tremendous toll on both patients and their families. Fintepla offers an additional effective treatment option for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome,” Billy Dunn, MD, director, Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

The FDA approved fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome based on the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials involving children ages 2 to 18 years with Dravet syndrome.

In both studies, children treated with fenfluramine experienced significantly greater reductions in the frequency of convulsive seizures than did their peers who received placebo. These reductions occurred within 3 to 4 weeks, and remained generally consistent over the 14- to 15-week treatment periods, the FDA said.

“There remains a huge unmet need for the many Dravet syndrome patients who continue to experience frequent severe seizures even while taking one or more of the currently available antiseizure medications,” Joseph Sullivan, MD, who worked on the fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome studies, said in a news release.

Given the “profound reductions” in convulsive seizure frequency seen in the clinical trials, combined with the “ongoing, robust safety monitoring,” fenfluramine offers “an extremely important treatment option for Dravet syndrome patients,” said Dr. Sullivan, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center of Excellence at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Fenfluramine is an anorectic agent that was used to treat obesity until it was removed from the market in 1997 over reports of increased risk of valvular heart disease when prescribed in higher doses and most often when prescribed with phentermine. The combination of the two drugs was known as fen-phen.

In the clinical trials of Dravet syndrome, the most common adverse reactions were decreased appetite; somnolence, sedation, lethargy; diarrhea; constipation; abnormal echocardiogram; fatigue, malaise, asthenia; ataxia, balance disorder, gait disturbance; increased blood pressure; drooling, salivary hypersecretion; pyrexia; upper respiratory tract infection; vomiting; decreased weight; fall; and status epilepticus.

The Fintepla label has a boxed warning stating that the drug is associated with valvular heart disease (VHD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Due to these risks, patients must undergo echocardiography before treatment, every 6 months during treatment, and once 3 to 6 months after treatment is stopped.

If signs of VHD, PAH, or other cardiac abnormalities are present, clinicians should weigh the benefits and risks of continuing treatment with Fintepla, the FDA said.

Fintepla is available only through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program, which requires physicians who prescribe the drug and pharmacies that dispense it to be certified in the Fintepla REMS and that patients be enrolled in the program.

As part of the REMS requirements, prescribers and patients must adhere to the required cardiac monitoring to receive the drug.

Fintepla will be available to certified prescribers in the United States in July. Zogenix is launching Zogenix Central, a comprehensive support service that will provide ongoing product assistance to patients, caregivers, and their medical teams. Further information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dravet syndrome is a rare childhood-onset epilepsy characterized by frequent, drug-resistant convulsive seizures that may contribute to intellectual disability and impairments in motor control, behavior, and cognition, as well as an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Dravet syndrome takes a “tremendous toll on both patients and their families. Fintepla offers an additional effective treatment option for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome,” Billy Dunn, MD, director, Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

The FDA approved fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome based on the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials involving children ages 2 to 18 years with Dravet syndrome.

In both studies, children treated with fenfluramine experienced significantly greater reductions in the frequency of convulsive seizures than did their peers who received placebo. These reductions occurred within 3 to 4 weeks, and remained generally consistent over the 14- to 15-week treatment periods, the FDA said.

“There remains a huge unmet need for the many Dravet syndrome patients who continue to experience frequent severe seizures even while taking one or more of the currently available antiseizure medications,” Joseph Sullivan, MD, who worked on the fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome studies, said in a news release.

Given the “profound reductions” in convulsive seizure frequency seen in the clinical trials, combined with the “ongoing, robust safety monitoring,” fenfluramine offers “an extremely important treatment option for Dravet syndrome patients,” said Dr. Sullivan, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center of Excellence at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Fenfluramine is an anorectic agent that was used to treat obesity until it was removed from the market in 1997 over reports of increased risk of valvular heart disease when prescribed in higher doses and most often when prescribed with phentermine. The combination of the two drugs was known as fen-phen.

In the clinical trials of Dravet syndrome, the most common adverse reactions were decreased appetite; somnolence, sedation, lethargy; diarrhea; constipation; abnormal echocardiogram; fatigue, malaise, asthenia; ataxia, balance disorder, gait disturbance; increased blood pressure; drooling, salivary hypersecretion; pyrexia; upper respiratory tract infection; vomiting; decreased weight; fall; and status epilepticus.

The Fintepla label has a boxed warning stating that the drug is associated with valvular heart disease (VHD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Due to these risks, patients must undergo echocardiography before treatment, every 6 months during treatment, and once 3 to 6 months after treatment is stopped.

If signs of VHD, PAH, or other cardiac abnormalities are present, clinicians should weigh the benefits and risks of continuing treatment with Fintepla, the FDA said.

Fintepla is available only through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program, which requires physicians who prescribe the drug and pharmacies that dispense it to be certified in the Fintepla REMS and that patients be enrolled in the program.

As part of the REMS requirements, prescribers and patients must adhere to the required cardiac monitoring to receive the drug.

Fintepla will be available to certified prescribers in the United States in July. Zogenix is launching Zogenix Central, a comprehensive support service that will provide ongoing product assistance to patients, caregivers, and their medical teams. Further information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dravet syndrome is a rare childhood-onset epilepsy characterized by frequent, drug-resistant convulsive seizures that may contribute to intellectual disability and impairments in motor control, behavior, and cognition, as well as an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Dravet syndrome takes a “tremendous toll on both patients and their families. Fintepla offers an additional effective treatment option for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome,” Billy Dunn, MD, director, Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

The FDA approved fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome based on the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials involving children ages 2 to 18 years with Dravet syndrome.

In both studies, children treated with fenfluramine experienced significantly greater reductions in the frequency of convulsive seizures than did their peers who received placebo. These reductions occurred within 3 to 4 weeks, and remained generally consistent over the 14- to 15-week treatment periods, the FDA said.

“There remains a huge unmet need for the many Dravet syndrome patients who continue to experience frequent severe seizures even while taking one or more of the currently available antiseizure medications,” Joseph Sullivan, MD, who worked on the fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome studies, said in a news release.

Given the “profound reductions” in convulsive seizure frequency seen in the clinical trials, combined with the “ongoing, robust safety monitoring,” fenfluramine offers “an extremely important treatment option for Dravet syndrome patients,” said Dr. Sullivan, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center of Excellence at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Fenfluramine is an anorectic agent that was used to treat obesity until it was removed from the market in 1997 over reports of increased risk of valvular heart disease when prescribed in higher doses and most often when prescribed with phentermine. The combination of the two drugs was known as fen-phen.

In the clinical trials of Dravet syndrome, the most common adverse reactions were decreased appetite; somnolence, sedation, lethargy; diarrhea; constipation; abnormal echocardiogram; fatigue, malaise, asthenia; ataxia, balance disorder, gait disturbance; increased blood pressure; drooling, salivary hypersecretion; pyrexia; upper respiratory tract infection; vomiting; decreased weight; fall; and status epilepticus.

The Fintepla label has a boxed warning stating that the drug is associated with valvular heart disease (VHD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Due to these risks, patients must undergo echocardiography before treatment, every 6 months during treatment, and once 3 to 6 months after treatment is stopped.

If signs of VHD, PAH, or other cardiac abnormalities are present, clinicians should weigh the benefits and risks of continuing treatment with Fintepla, the FDA said.

Fintepla is available only through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program, which requires physicians who prescribe the drug and pharmacies that dispense it to be certified in the Fintepla REMS and that patients be enrolled in the program.

As part of the REMS requirements, prescribers and patients must adhere to the required cardiac monitoring to receive the drug.

Fintepla will be available to certified prescribers in the United States in July. Zogenix is launching Zogenix Central, a comprehensive support service that will provide ongoing product assistance to patients, caregivers, and their medical teams. Further information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most adult epilepsy-related deaths could be avoided

The research shows that such avoidable deaths “remain common and have not declined over time, despite advances in treatment,” Gashirai Mbizvo, MBChB, PhD, clinical research fellow, Muir Maxwell Epilepsy Center, the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, told a press briefing.

The findings were presented at the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) 2020, which is being conducted as a virtual/online meeting because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As his PhD dissertation, Dr. Mbizvo is investigating the rates, causes, and risk factors for epilepsy-related deaths and the percentage of these that are potentially avoidable.

The National Health Service of Scotland contains various linked administrative data sets. Each resident of Scotland has a unique identifier that facilitates investigations across the health system.

Dr. Mbizvo investigated adults and adolescents aged 16 years and older who died because of epilepsy during 2009-2016. He compared this group to patients of similar age who were living with epilepsy to identify risk factors that might help focus resources. During the study period, 2,149 epilepsy-related deaths occurred. Nearly 60% involved at least one seizure-related hospital admission.

Heavy burden

Of the patients who died because of epilepsy, 24% were seen in an outpatient neurologic clinic. “So there’s this heavy burden of admissions not translating to neurology follow-up,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

During the study period, there was no reduction in mortality “despite advances in medical care,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Younger people with epilepsy were found to be more likely to die. The standardized mortality rate was 6/100,000 (95% confidence interval, 2.3-9.7) among those aged 16-24 years. By contrast, among those aged 45-54 years, the rate was 2/100,000 (95% CI, 1.1-2.1); it was lower in older age groups.

“The overall mortality is not reducing; people are dying young, and neurologists are really not getting involved,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

Among the almost 600 deaths of those aged 16-54 years, 58% were from Scotland’s “most deprived areas,” he noted.

From medical records and antiepileptic drug (AED) use, Dr. Mbizvo looked for risk factors that may have contributed to these epilepsy-related deaths. The most common cause of death in the group aged 16- 54 years was sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), followed by respiratory disorders, such as aspiration pneumonia.

“We think this should be avoidable, in the sense that these are people that could perhaps be targeted early with, for example, antibiotics,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

The next most common cause of death was circulatory disease, largely cardiac arrest.

“The idea is that electroexcitation – an abnormality in the brain – and the heart are related, and maybe that’s translating to a risk of death,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Worrisome group

Mental and behavioral disorders, largely alcohol related, were the next most common cause of death.

“This is a group I worry about,” said Dr. Mbizvo. “I think they’re seen in the acute services and discharged as alcohol-withdrawal seizures. It’s possible that some have epilepsy and are never referred to a neurologist, and this may translate into increased mortality.”

Dr. Mbizvo is analyzing how these results differ from what is seen in the general population of Scotland among those younger than 75 years.

The top cause of death in the general population is neoplasm of the lungs. Aspiration of the lung is near the top for those who died from epilepsy, but the mechanisms leading to lung-related deaths in these populations may differ, said Dr. Mbizvo.

By applying coding methodology from fields unrelated to epilepsy where this approach has been tried, he determined that 78% of epilepsy-related deaths among those younger than 55 years were potentially avoidable.

“As a method, this is still in its infancy and will require validation, but we see this as a start,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

He provided examples from medical records that illustrate avoidable factors that could contribute to death. These included cases in which patients were discharged with the wrong dose of AED and in which patients drowned in a bath after having not been appropriately educated about seizure safety.

Can’t plug in

Patients with a first seizure are typically referred quickly to an appropriate service, but Dr. Mbizvo is concerned about those with chronic, stable epilepsy. “These people may at some point decompensate, and there’s no channel to plug them back into neurology services to make it easy for them to access a neurologist,” he said.

Currently, experts tell discharged patients to call if a problem occurs, but the system “is rather ad hoc,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Because of the COVID-19 crisis, the use of telemedicine is increasing. This is helping to improve the system. “We may be able to build a virtual community for people who are on antiepileptic drugs and who suddenly begin to experience seizures again, to enable them to quickly get help, alongside a defined pathway to an epilepsy specialist,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

He hopes to develop a risk index for epilepsy patients similar to one used in cardiology that assesses risks such as smoking, high cholesterol level, and obesity. Although such a risk score might be similar to the SUDEP risk indices being developed, it will take into account death from any epilepsy-related cause, said Dr. Mbizvo. “Having not yet completed the analysis, I’m not sure which aspects will confer the greatest risk,” he said.

He added that, anecdotally, he has noticed a slight trend toward high mortality among patients with epilepsy who present multiple times at emergency departments in a year.

If this trend is statistically valid, “it could help create a traffic light flagging system on A&Es [accident and emergency departments] in which individuals with epilepsy who, for example, have two or more attendances to A&E in a year become flagged as high risk of death and are plugged into a rapid access epilepsy specialist clinic,” he said.

For their part, neurologists should recognize drug-resistant epilepsy early and refer such patients for assessment for resective surgery. If successful, such surgery reduces the risk for premature mortality, said Dr. Mbizvo.

Patients should not become discouraged by drug resistance, either. Research shows that, with careful reassessment of epilepsy type and drug changes, some patients whose condition is thought to be intractable could experience significant improvement in seizure frequency or seizures could be stopped.

“We need to talk to our patients more about the importance of adherence and encourage them to be honest with us if they don’t like the drugs we’re giving them and, as a result, are not taking them as recommended,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

Physicians also need to screen for mood disorders, especially suicidal ideation. Increasingly, specialists are recognizing mental health as an important area of epilepsy care.

They should also conduct a “safety briefing” perhaps twice a year in which they discuss, for example, SUDEP risk, driving concerns, showering instead of bathing, ensuring that a life guard is present at a swimming pool, and other measures.

Commenting on the study, Josemir W. (Ley) Sander, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and clinical epilepsy at University College London, said he welcomes any effort that highlights the problem of premature death among people with epilepsy and that offers possible ways to mitigate it.

Although the study “shows that premature death among people with epilepsy is a major issue,” many health care providers are not fully aware of the extent of this problem, said Dr. Sander. “For many, epilepsy is just a benign condition in which people have seizures,” he said. A risk score that could identify those at high risk for death and establishing preventive measures “would go a long way to decrease the burden of epilepsy,” he noted.

The study was supported by Epilepsy Research UK and the Juliet Bergqvist Memorial Fund. Dr. Mbizvo and Dr. Sander have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The research shows that such avoidable deaths “remain common and have not declined over time, despite advances in treatment,” Gashirai Mbizvo, MBChB, PhD, clinical research fellow, Muir Maxwell Epilepsy Center, the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, told a press briefing.

The findings were presented at the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) 2020, which is being conducted as a virtual/online meeting because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As his PhD dissertation, Dr. Mbizvo is investigating the rates, causes, and risk factors for epilepsy-related deaths and the percentage of these that are potentially avoidable.

The National Health Service of Scotland contains various linked administrative data sets. Each resident of Scotland has a unique identifier that facilitates investigations across the health system.

Dr. Mbizvo investigated adults and adolescents aged 16 years and older who died because of epilepsy during 2009-2016. He compared this group to patients of similar age who were living with epilepsy to identify risk factors that might help focus resources. During the study period, 2,149 epilepsy-related deaths occurred. Nearly 60% involved at least one seizure-related hospital admission.

Heavy burden

Of the patients who died because of epilepsy, 24% were seen in an outpatient neurologic clinic. “So there’s this heavy burden of admissions not translating to neurology follow-up,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

During the study period, there was no reduction in mortality “despite advances in medical care,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Younger people with epilepsy were found to be more likely to die. The standardized mortality rate was 6/100,000 (95% confidence interval, 2.3-9.7) among those aged 16-24 years. By contrast, among those aged 45-54 years, the rate was 2/100,000 (95% CI, 1.1-2.1); it was lower in older age groups.

“The overall mortality is not reducing; people are dying young, and neurologists are really not getting involved,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

Among the almost 600 deaths of those aged 16-54 years, 58% were from Scotland’s “most deprived areas,” he noted.

From medical records and antiepileptic drug (AED) use, Dr. Mbizvo looked for risk factors that may have contributed to these epilepsy-related deaths. The most common cause of death in the group aged 16- 54 years was sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), followed by respiratory disorders, such as aspiration pneumonia.

“We think this should be avoidable, in the sense that these are people that could perhaps be targeted early with, for example, antibiotics,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

The next most common cause of death was circulatory disease, largely cardiac arrest.

“The idea is that electroexcitation – an abnormality in the brain – and the heart are related, and maybe that’s translating to a risk of death,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Worrisome group

Mental and behavioral disorders, largely alcohol related, were the next most common cause of death.

“This is a group I worry about,” said Dr. Mbizvo. “I think they’re seen in the acute services and discharged as alcohol-withdrawal seizures. It’s possible that some have epilepsy and are never referred to a neurologist, and this may translate into increased mortality.”

Dr. Mbizvo is analyzing how these results differ from what is seen in the general population of Scotland among those younger than 75 years.

The top cause of death in the general population is neoplasm of the lungs. Aspiration of the lung is near the top for those who died from epilepsy, but the mechanisms leading to lung-related deaths in these populations may differ, said Dr. Mbizvo.

By applying coding methodology from fields unrelated to epilepsy where this approach has been tried, he determined that 78% of epilepsy-related deaths among those younger than 55 years were potentially avoidable.

“As a method, this is still in its infancy and will require validation, but we see this as a start,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

He provided examples from medical records that illustrate avoidable factors that could contribute to death. These included cases in which patients were discharged with the wrong dose of AED and in which patients drowned in a bath after having not been appropriately educated about seizure safety.

Can’t plug in

Patients with a first seizure are typically referred quickly to an appropriate service, but Dr. Mbizvo is concerned about those with chronic, stable epilepsy. “These people may at some point decompensate, and there’s no channel to plug them back into neurology services to make it easy for them to access a neurologist,” he said.

Currently, experts tell discharged patients to call if a problem occurs, but the system “is rather ad hoc,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Because of the COVID-19 crisis, the use of telemedicine is increasing. This is helping to improve the system. “We may be able to build a virtual community for people who are on antiepileptic drugs and who suddenly begin to experience seizures again, to enable them to quickly get help, alongside a defined pathway to an epilepsy specialist,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

He hopes to develop a risk index for epilepsy patients similar to one used in cardiology that assesses risks such as smoking, high cholesterol level, and obesity. Although such a risk score might be similar to the SUDEP risk indices being developed, it will take into account death from any epilepsy-related cause, said Dr. Mbizvo. “Having not yet completed the analysis, I’m not sure which aspects will confer the greatest risk,” he said.

He added that, anecdotally, he has noticed a slight trend toward high mortality among patients with epilepsy who present multiple times at emergency departments in a year.

If this trend is statistically valid, “it could help create a traffic light flagging system on A&Es [accident and emergency departments] in which individuals with epilepsy who, for example, have two or more attendances to A&E in a year become flagged as high risk of death and are plugged into a rapid access epilepsy specialist clinic,” he said.

For their part, neurologists should recognize drug-resistant epilepsy early and refer such patients for assessment for resective surgery. If successful, such surgery reduces the risk for premature mortality, said Dr. Mbizvo.

Patients should not become discouraged by drug resistance, either. Research shows that, with careful reassessment of epilepsy type and drug changes, some patients whose condition is thought to be intractable could experience significant improvement in seizure frequency or seizures could be stopped.

“We need to talk to our patients more about the importance of adherence and encourage them to be honest with us if they don’t like the drugs we’re giving them and, as a result, are not taking them as recommended,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

Physicians also need to screen for mood disorders, especially suicidal ideation. Increasingly, specialists are recognizing mental health as an important area of epilepsy care.

They should also conduct a “safety briefing” perhaps twice a year in which they discuss, for example, SUDEP risk, driving concerns, showering instead of bathing, ensuring that a life guard is present at a swimming pool, and other measures.

Commenting on the study, Josemir W. (Ley) Sander, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and clinical epilepsy at University College London, said he welcomes any effort that highlights the problem of premature death among people with epilepsy and that offers possible ways to mitigate it.

Although the study “shows that premature death among people with epilepsy is a major issue,” many health care providers are not fully aware of the extent of this problem, said Dr. Sander. “For many, epilepsy is just a benign condition in which people have seizures,” he said. A risk score that could identify those at high risk for death and establishing preventive measures “would go a long way to decrease the burden of epilepsy,” he noted.

The study was supported by Epilepsy Research UK and the Juliet Bergqvist Memorial Fund. Dr. Mbizvo and Dr. Sander have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The research shows that such avoidable deaths “remain common and have not declined over time, despite advances in treatment,” Gashirai Mbizvo, MBChB, PhD, clinical research fellow, Muir Maxwell Epilepsy Center, the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, told a press briefing.

The findings were presented at the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) 2020, which is being conducted as a virtual/online meeting because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As his PhD dissertation, Dr. Mbizvo is investigating the rates, causes, and risk factors for epilepsy-related deaths and the percentage of these that are potentially avoidable.

The National Health Service of Scotland contains various linked administrative data sets. Each resident of Scotland has a unique identifier that facilitates investigations across the health system.

Dr. Mbizvo investigated adults and adolescents aged 16 years and older who died because of epilepsy during 2009-2016. He compared this group to patients of similar age who were living with epilepsy to identify risk factors that might help focus resources. During the study period, 2,149 epilepsy-related deaths occurred. Nearly 60% involved at least one seizure-related hospital admission.

Heavy burden

Of the patients who died because of epilepsy, 24% were seen in an outpatient neurologic clinic. “So there’s this heavy burden of admissions not translating to neurology follow-up,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

During the study period, there was no reduction in mortality “despite advances in medical care,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Younger people with epilepsy were found to be more likely to die. The standardized mortality rate was 6/100,000 (95% confidence interval, 2.3-9.7) among those aged 16-24 years. By contrast, among those aged 45-54 years, the rate was 2/100,000 (95% CI, 1.1-2.1); it was lower in older age groups.

“The overall mortality is not reducing; people are dying young, and neurologists are really not getting involved,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

Among the almost 600 deaths of those aged 16-54 years, 58% were from Scotland’s “most deprived areas,” he noted.

From medical records and antiepileptic drug (AED) use, Dr. Mbizvo looked for risk factors that may have contributed to these epilepsy-related deaths. The most common cause of death in the group aged 16- 54 years was sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), followed by respiratory disorders, such as aspiration pneumonia.

“We think this should be avoidable, in the sense that these are people that could perhaps be targeted early with, for example, antibiotics,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

The next most common cause of death was circulatory disease, largely cardiac arrest.

“The idea is that electroexcitation – an abnormality in the brain – and the heart are related, and maybe that’s translating to a risk of death,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Worrisome group

Mental and behavioral disorders, largely alcohol related, were the next most common cause of death.

“This is a group I worry about,” said Dr. Mbizvo. “I think they’re seen in the acute services and discharged as alcohol-withdrawal seizures. It’s possible that some have epilepsy and are never referred to a neurologist, and this may translate into increased mortality.”

Dr. Mbizvo is analyzing how these results differ from what is seen in the general population of Scotland among those younger than 75 years.

The top cause of death in the general population is neoplasm of the lungs. Aspiration of the lung is near the top for those who died from epilepsy, but the mechanisms leading to lung-related deaths in these populations may differ, said Dr. Mbizvo.

By applying coding methodology from fields unrelated to epilepsy where this approach has been tried, he determined that 78% of epilepsy-related deaths among those younger than 55 years were potentially avoidable.

“As a method, this is still in its infancy and will require validation, but we see this as a start,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

He provided examples from medical records that illustrate avoidable factors that could contribute to death. These included cases in which patients were discharged with the wrong dose of AED and in which patients drowned in a bath after having not been appropriately educated about seizure safety.

Can’t plug in

Patients with a first seizure are typically referred quickly to an appropriate service, but Dr. Mbizvo is concerned about those with chronic, stable epilepsy. “These people may at some point decompensate, and there’s no channel to plug them back into neurology services to make it easy for them to access a neurologist,” he said.

Currently, experts tell discharged patients to call if a problem occurs, but the system “is rather ad hoc,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

Because of the COVID-19 crisis, the use of telemedicine is increasing. This is helping to improve the system. “We may be able to build a virtual community for people who are on antiepileptic drugs and who suddenly begin to experience seizures again, to enable them to quickly get help, alongside a defined pathway to an epilepsy specialist,” said Dr. Mbizvo.

He hopes to develop a risk index for epilepsy patients similar to one used in cardiology that assesses risks such as smoking, high cholesterol level, and obesity. Although such a risk score might be similar to the SUDEP risk indices being developed, it will take into account death from any epilepsy-related cause, said Dr. Mbizvo. “Having not yet completed the analysis, I’m not sure which aspects will confer the greatest risk,” he said.

He added that, anecdotally, he has noticed a slight trend toward high mortality among patients with epilepsy who present multiple times at emergency departments in a year.

If this trend is statistically valid, “it could help create a traffic light flagging system on A&Es [accident and emergency departments] in which individuals with epilepsy who, for example, have two or more attendances to A&E in a year become flagged as high risk of death and are plugged into a rapid access epilepsy specialist clinic,” he said.

For their part, neurologists should recognize drug-resistant epilepsy early and refer such patients for assessment for resective surgery. If successful, such surgery reduces the risk for premature mortality, said Dr. Mbizvo.

Patients should not become discouraged by drug resistance, either. Research shows that, with careful reassessment of epilepsy type and drug changes, some patients whose condition is thought to be intractable could experience significant improvement in seizure frequency or seizures could be stopped.

“We need to talk to our patients more about the importance of adherence and encourage them to be honest with us if they don’t like the drugs we’re giving them and, as a result, are not taking them as recommended,” Dr. Mbizvo said.

Physicians also need to screen for mood disorders, especially suicidal ideation. Increasingly, specialists are recognizing mental health as an important area of epilepsy care.

They should also conduct a “safety briefing” perhaps twice a year in which they discuss, for example, SUDEP risk, driving concerns, showering instead of bathing, ensuring that a life guard is present at a swimming pool, and other measures.

Commenting on the study, Josemir W. (Ley) Sander, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and clinical epilepsy at University College London, said he welcomes any effort that highlights the problem of premature death among people with epilepsy and that offers possible ways to mitigate it.

Although the study “shows that premature death among people with epilepsy is a major issue,” many health care providers are not fully aware of the extent of this problem, said Dr. Sander. “For many, epilepsy is just a benign condition in which people have seizures,” he said. A risk score that could identify those at high risk for death and establishing preventive measures “would go a long way to decrease the burden of epilepsy,” he noted.

The study was supported by Epilepsy Research UK and the Juliet Bergqvist Memorial Fund. Dr. Mbizvo and Dr. Sander have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EAN 2020

Neurologists’ pay gets a boost, most happy with career choice

findings from the newly released Medscape Neurologist Compensation Report 2020 show.

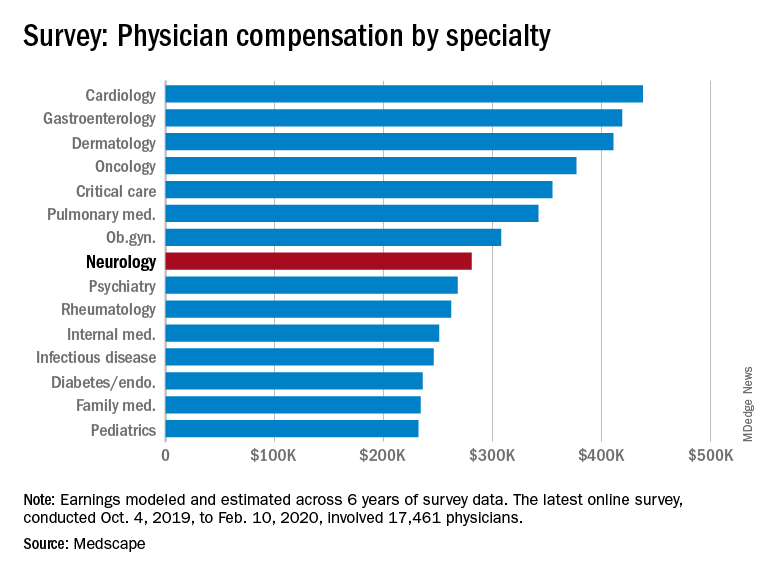

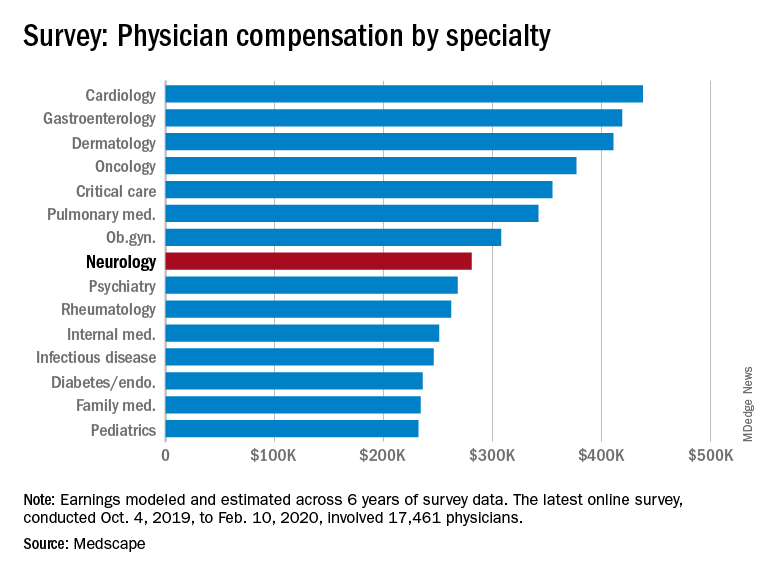

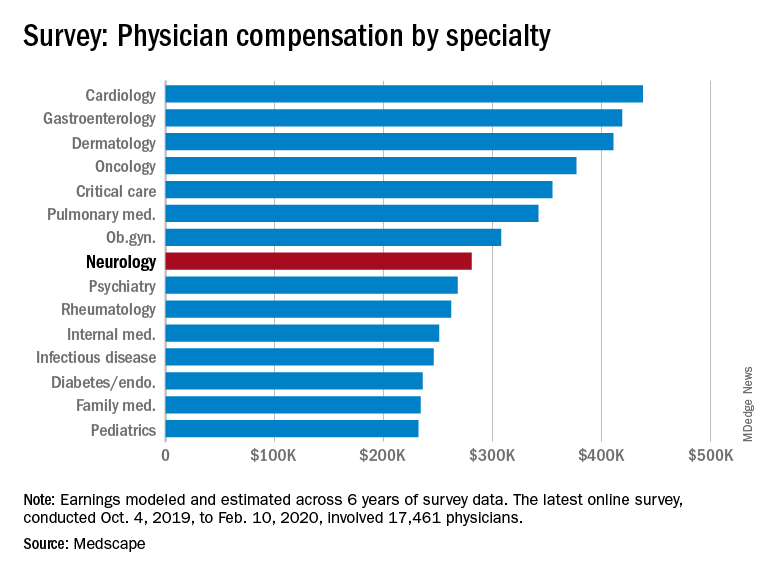

Neurologists’ average annual income this year rose to $280,000, up from $267,000 last year. More than half of neurologists (53%) feel fairly compensated, similar to last year’s percentage.

Neurologists are below the middle earners of all physician specialties. At $280,000 in annual compensation for patient care, neurologists rank ninth from the bottom, just below allergists/immunologists ($301,000) but ahead of psychiatrists ($268,000), rheumatologists ($262,000), and internists ($251,000).