User login

You have ‘unique expertise’ to treat opioid use disorder in adolescents

ORLANDO – according to a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We pediatricians have some unique skills that can really benefit our community of teens,” said Deepa Camenga, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Compared with some other specialists, who may be more reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine, pediatricians are more comfortable and have systems in place to deal with issues surrounding care coordination, adolescent confidentiality, family reassurance, and managing prescriptions for chronic diseases.“We can use those same skills when we’re caring for people with opioid use disorder,” she said.

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–5), there are 11 criteria for opioid use disorder based on level of physiological dependence, impaired control, social functioning, and risky use. Meeting two or three criteria constitutes mild substance use disorder, while meeting six or more criteria is associated with severe substance use disorder.

Opioid use disorder in adolescents can be characterized by milder symptoms. Adolescents also tend to be in the early stage of this chronic disease when they seek care for opioid use disorder and need to be informed about the seriousness of the disease, Dr. Camenga noted.

“There is a disconnect about the severity of their illness when they present to me,” she said. “This is a disease that we know is chronic, severe – and without treatment – is progressive. We do know it can progress and get worse, and result in death.”

Treatment options for opioid use disorder in adolescents include behavioral interventions such as residential treatment, intensive outpatient (IOP), and partial hospitalization programs and therapy, as well as pharmacologic interventions like clonidine, buprenorphine, and methadone used for detoxification. Buprenorphine/naloxone has been labeled for use by patients 18 years or older; however, three recent randomized controlled trials have studied the effects of the intervention in 16-year-old and 17-year-old patients. In the trials, there were no serious adverse events reported with support of treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks and “many providers are treating up to a year” based on data from observational studies, Dr. Camenga said. Naltrexone also has been indicated for adolescents with opioid use disorder, with feasibility seen in pilot studies.

If you are interested in providing buprenorphine for patients, you need to apply for a Drug Enforcement Administration X-waiver, have access to their state’s prescription-monitoring program, and have a network of behavioral health providers for therapy and counseling, as well as psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment of other psychiatric disorders. Familiarity with naloxone overdose prevention training also is beneficial.

In addition, you must undergo 8 hours of training and apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in general medication settings. You can receive ongoing support after training on the AAP and Providers Clinical Support System websites.

Adolescent patients who receive buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder typically undergo induction for 2 days where they are observed by a nurse or provider followed by weekly or biweekly medication-monitoring visits. It is “highly recommended” adolescents take urine drug screens during these visits but the results do not need to be observed. Many patients begin treatment when they are in IOP care, but some patients are not identified until they’ve had more severe consequences of opioid use disorder. Parents are involved in care by providing transportation and picking up and helping to administer medication, but there are confidential portions of the visits with the patient only.

“Parents have to be intimately involved and aware, and that’s an ideal situation,” Dr. Camenga said.

Dr. Camenga reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – according to a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We pediatricians have some unique skills that can really benefit our community of teens,” said Deepa Camenga, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Compared with some other specialists, who may be more reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine, pediatricians are more comfortable and have systems in place to deal with issues surrounding care coordination, adolescent confidentiality, family reassurance, and managing prescriptions for chronic diseases.“We can use those same skills when we’re caring for people with opioid use disorder,” she said.

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–5), there are 11 criteria for opioid use disorder based on level of physiological dependence, impaired control, social functioning, and risky use. Meeting two or three criteria constitutes mild substance use disorder, while meeting six or more criteria is associated with severe substance use disorder.

Opioid use disorder in adolescents can be characterized by milder symptoms. Adolescents also tend to be in the early stage of this chronic disease when they seek care for opioid use disorder and need to be informed about the seriousness of the disease, Dr. Camenga noted.

“There is a disconnect about the severity of their illness when they present to me,” she said. “This is a disease that we know is chronic, severe – and without treatment – is progressive. We do know it can progress and get worse, and result in death.”

Treatment options for opioid use disorder in adolescents include behavioral interventions such as residential treatment, intensive outpatient (IOP), and partial hospitalization programs and therapy, as well as pharmacologic interventions like clonidine, buprenorphine, and methadone used for detoxification. Buprenorphine/naloxone has been labeled for use by patients 18 years or older; however, three recent randomized controlled trials have studied the effects of the intervention in 16-year-old and 17-year-old patients. In the trials, there were no serious adverse events reported with support of treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks and “many providers are treating up to a year” based on data from observational studies, Dr. Camenga said. Naltrexone also has been indicated for adolescents with opioid use disorder, with feasibility seen in pilot studies.

If you are interested in providing buprenorphine for patients, you need to apply for a Drug Enforcement Administration X-waiver, have access to their state’s prescription-monitoring program, and have a network of behavioral health providers for therapy and counseling, as well as psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment of other psychiatric disorders. Familiarity with naloxone overdose prevention training also is beneficial.

In addition, you must undergo 8 hours of training and apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in general medication settings. You can receive ongoing support after training on the AAP and Providers Clinical Support System websites.

Adolescent patients who receive buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder typically undergo induction for 2 days where they are observed by a nurse or provider followed by weekly or biweekly medication-monitoring visits. It is “highly recommended” adolescents take urine drug screens during these visits but the results do not need to be observed. Many patients begin treatment when they are in IOP care, but some patients are not identified until they’ve had more severe consequences of opioid use disorder. Parents are involved in care by providing transportation and picking up and helping to administer medication, but there are confidential portions of the visits with the patient only.

“Parents have to be intimately involved and aware, and that’s an ideal situation,” Dr. Camenga said.

Dr. Camenga reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – according to a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We pediatricians have some unique skills that can really benefit our community of teens,” said Deepa Camenga, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Compared with some other specialists, who may be more reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine, pediatricians are more comfortable and have systems in place to deal with issues surrounding care coordination, adolescent confidentiality, family reassurance, and managing prescriptions for chronic diseases.“We can use those same skills when we’re caring for people with opioid use disorder,” she said.

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–5), there are 11 criteria for opioid use disorder based on level of physiological dependence, impaired control, social functioning, and risky use. Meeting two or three criteria constitutes mild substance use disorder, while meeting six or more criteria is associated with severe substance use disorder.

Opioid use disorder in adolescents can be characterized by milder symptoms. Adolescents also tend to be in the early stage of this chronic disease when they seek care for opioid use disorder and need to be informed about the seriousness of the disease, Dr. Camenga noted.

“There is a disconnect about the severity of their illness when they present to me,” she said. “This is a disease that we know is chronic, severe – and without treatment – is progressive. We do know it can progress and get worse, and result in death.”

Treatment options for opioid use disorder in adolescents include behavioral interventions such as residential treatment, intensive outpatient (IOP), and partial hospitalization programs and therapy, as well as pharmacologic interventions like clonidine, buprenorphine, and methadone used for detoxification. Buprenorphine/naloxone has been labeled for use by patients 18 years or older; however, three recent randomized controlled trials have studied the effects of the intervention in 16-year-old and 17-year-old patients. In the trials, there were no serious adverse events reported with support of treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks and “many providers are treating up to a year” based on data from observational studies, Dr. Camenga said. Naltrexone also has been indicated for adolescents with opioid use disorder, with feasibility seen in pilot studies.

If you are interested in providing buprenorphine for patients, you need to apply for a Drug Enforcement Administration X-waiver, have access to their state’s prescription-monitoring program, and have a network of behavioral health providers for therapy and counseling, as well as psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment of other psychiatric disorders. Familiarity with naloxone overdose prevention training also is beneficial.

In addition, you must undergo 8 hours of training and apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in general medication settings. You can receive ongoing support after training on the AAP and Providers Clinical Support System websites.

Adolescent patients who receive buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder typically undergo induction for 2 days where they are observed by a nurse or provider followed by weekly or biweekly medication-monitoring visits. It is “highly recommended” adolescents take urine drug screens during these visits but the results do not need to be observed. Many patients begin treatment when they are in IOP care, but some patients are not identified until they’ve had more severe consequences of opioid use disorder. Parents are involved in care by providing transportation and picking up and helping to administer medication, but there are confidential portions of the visits with the patient only.

“Parents have to be intimately involved and aware, and that’s an ideal situation,” Dr. Camenga said.

Dr. Camenga reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AAP 18

United States must join with world to protect refugee children

ORLANDO – The United States is one of the wealthiest nations on the planet, yet it does not always stand with the rest of the global community in promoting universally accepted principles on the health and well-being of children across the world, particularly refugee children, according to Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Rushton discussed the importance of seeing American exceptionalism for what it is – a flaw rather than a virtue – and joining with the rest of the world in upholding the tenets of the Budapest Declaration On the Rights, Health and Well-being of Children and Youth on the Move.

In the three-page Budapest document, created by the International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health (ISSOP) in October 2017 and endorsed by the AAP, pediatricians from across the world acknowledge the realities of worldwide refugee crises and accept their detailed responsibilities in meeting and advocating for those children’s needs.

Although the current administration’s decision earlier this year to split children from their families at the border caught everyone attention, . He particularly stressed the “importance of working with the global community on clinical services, programs and policy.”

Dr. Rushton, clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and medical director of the Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics network, also discussed the need to commit to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and to join the global community in following the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and the principles in the World Health Organization’s publication, “Nurturing care for early childhood development.”

The former is a “blueprint” to overcoming challenges related to “poverty, inequality, climate, environmental degradation, prosperity and peace and justice” by achieving targets by 2030, and the latter is “a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential.”

“This is our issue as child health professionals. We need to continue applying pressure on our political leaders,” Dr. Rushton told his colleagues. He advocated taking the long view: “Let’s build a system that respects the human rights of all children.”

ORLANDO – The United States is one of the wealthiest nations on the planet, yet it does not always stand with the rest of the global community in promoting universally accepted principles on the health and well-being of children across the world, particularly refugee children, according to Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Rushton discussed the importance of seeing American exceptionalism for what it is – a flaw rather than a virtue – and joining with the rest of the world in upholding the tenets of the Budapest Declaration On the Rights, Health and Well-being of Children and Youth on the Move.

In the three-page Budapest document, created by the International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health (ISSOP) in October 2017 and endorsed by the AAP, pediatricians from across the world acknowledge the realities of worldwide refugee crises and accept their detailed responsibilities in meeting and advocating for those children’s needs.

Although the current administration’s decision earlier this year to split children from their families at the border caught everyone attention, . He particularly stressed the “importance of working with the global community on clinical services, programs and policy.”

Dr. Rushton, clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and medical director of the Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics network, also discussed the need to commit to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and to join the global community in following the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and the principles in the World Health Organization’s publication, “Nurturing care for early childhood development.”

The former is a “blueprint” to overcoming challenges related to “poverty, inequality, climate, environmental degradation, prosperity and peace and justice” by achieving targets by 2030, and the latter is “a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential.”

“This is our issue as child health professionals. We need to continue applying pressure on our political leaders,” Dr. Rushton told his colleagues. He advocated taking the long view: “Let’s build a system that respects the human rights of all children.”

ORLANDO – The United States is one of the wealthiest nations on the planet, yet it does not always stand with the rest of the global community in promoting universally accepted principles on the health and well-being of children across the world, particularly refugee children, according to Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Rushton discussed the importance of seeing American exceptionalism for what it is – a flaw rather than a virtue – and joining with the rest of the world in upholding the tenets of the Budapest Declaration On the Rights, Health and Well-being of Children and Youth on the Move.

In the three-page Budapest document, created by the International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health (ISSOP) in October 2017 and endorsed by the AAP, pediatricians from across the world acknowledge the realities of worldwide refugee crises and accept their detailed responsibilities in meeting and advocating for those children’s needs.

Although the current administration’s decision earlier this year to split children from their families at the border caught everyone attention, . He particularly stressed the “importance of working with the global community on clinical services, programs and policy.”

Dr. Rushton, clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and medical director of the Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics network, also discussed the need to commit to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and to join the global community in following the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and the principles in the World Health Organization’s publication, “Nurturing care for early childhood development.”

The former is a “blueprint” to overcoming challenges related to “poverty, inequality, climate, environmental degradation, prosperity and peace and justice” by achieving targets by 2030, and the latter is “a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential.”

“This is our issue as child health professionals. We need to continue applying pressure on our political leaders,” Dr. Rushton told his colleagues. He advocated taking the long view: “Let’s build a system that respects the human rights of all children.”

REPORTING FROM AAP 2018

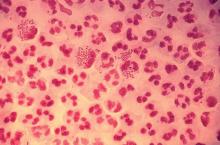

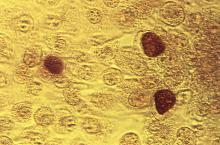

Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

ORLANDO – Consider point-of-care testing and treat potentially infected partners when diagnosing and treating adolescents for STIs, Diane M. Straub, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, adolescents are sometimes reluctant to disclose their full sexual history to their health care provider, which can complicate diagnosis and treatment, noted Dr. Straub, professor of pediatrics at the University of South Florida, Tampa. “That sometimes takes a few questions,” but can be achieved by asking the same questions in different ways and emphasizing the clinical importance of testing.

According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey, 40% of adolescents reported ever having sexual intercourse, with 20% of 9th-grade, 36% of 10th-grade, 47% of 11th-grade, and 57% of 12th-grade students reporting they had sexual intercourse. By gender, 41% of adolescent males and 38% of adolescent females reported ever having sexual intercourse; by race, 39% of white, 41% of Hispanic, and 46% of black participants reported any sexual activity. Overall, 10% of adolescents said they had four or more partners, 3% said they had intercourse before age 13 years, 54% used a condom the last time they had intercourse, and 7% said they were raped.

The rate of STIs in the United States is rising. There has been a sharp increase in the number of combined diagnoses of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia, with an increase from 1.8 million in 2013 to 2.3 million cases in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time period, gonorrhea increased 67% from 333,004 to 555,608 cases, syphilis (primary and secondary) rose 76% from 17,375 to 30,644 cases, and chlamydia increased 22% to 1.7 million cases.

According to a 2013 CDC infographic shown by Dr. Straub, young people in the United States aged 15-24 years old represent 27% of the total sexually active population but account for 50% of new STI cases each year. Persons in this population account for 70% of gonorrhea cases, 63% of chlamydia cases, 49% of human papillomavirus (HPV) cases, 45% of genital herpes cases, and 20% of syphilis cases.

All sexually active females aged 25 years or younger should be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea, as well as “at-risk” young men who have sex with men (YMSM), Dr. Straub said. All adolescent males and females aged over 13 years should be offered HIV screening, and HIV screening should be discussed “at least once.” And depending on how at risk each subpopulation is, health care providers should be have that conversation and offer screening multiple times.

Women who have sex with women (WSW) are a diverse population and should be treated based on their individual sexual identities, behaviors, and practices. “Most self-identified WSWs report having sex with men, so therefore adolescent WSWs and females with both male and female sex partners might be at increased risk for STIs, such as syphillis, chlamydia, and HPV as well as HIV, so you may want to adjust your screening accordingly,” she said.

Pregnant women, if at risk, should be screened for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

YMSM should have annual screenings for syphilis and HIV, screenings for chlamydia and gonorrhea by infection site; also consider herpes simplex virus serology and anal cytology in these patients, Dr. Straub said. They also should be screened for hepatitis B surface antigen, vaccinated for hepatitis A, hepatitis B and, if using drugs, screened* for hepatitis C virus.

Dr. Straub recommended licensed health care professionals who may treat minor patients review their state’s laws on minors and their legal ability to consent to treatment of STIs without the involvement of their parent or guardian, including disclosure of positive results and in the case of HIV care.

In places where index insured are allowed to find out about any services a beneficiary receives on their insurance, “this is a little problematic, because in some states, this is in direct conflict with the explanation of benefits requirement,” she said. “There are certain ways to get around that, but it’s really important for you to know what the statutes are where you’re practicing and where the breaches of confidentiality [are].”

Expedited partner therapy, or treating one or multiple partners of patients with an STI, is recommended for certain patients and infections, such as male partners of female patients with chlamydia and gonorrhea. While this is recommended less for YMSM because of a higher rate of concurrent infection, “if you have a young person who has partners who are unlikely to have access to care and get treated, it’s recommended you give that treatment to your index patient and to then treat their partners,” Dr. Straub said.

A recent and frequently updated resource on STI treatment can be found at the CDC website.

Dr. Straub reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated 1/11/19.

ORLANDO – Consider point-of-care testing and treat potentially infected partners when diagnosing and treating adolescents for STIs, Diane M. Straub, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, adolescents are sometimes reluctant to disclose their full sexual history to their health care provider, which can complicate diagnosis and treatment, noted Dr. Straub, professor of pediatrics at the University of South Florida, Tampa. “That sometimes takes a few questions,” but can be achieved by asking the same questions in different ways and emphasizing the clinical importance of testing.

According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey, 40% of adolescents reported ever having sexual intercourse, with 20% of 9th-grade, 36% of 10th-grade, 47% of 11th-grade, and 57% of 12th-grade students reporting they had sexual intercourse. By gender, 41% of adolescent males and 38% of adolescent females reported ever having sexual intercourse; by race, 39% of white, 41% of Hispanic, and 46% of black participants reported any sexual activity. Overall, 10% of adolescents said they had four or more partners, 3% said they had intercourse before age 13 years, 54% used a condom the last time they had intercourse, and 7% said they were raped.

The rate of STIs in the United States is rising. There has been a sharp increase in the number of combined diagnoses of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia, with an increase from 1.8 million in 2013 to 2.3 million cases in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time period, gonorrhea increased 67% from 333,004 to 555,608 cases, syphilis (primary and secondary) rose 76% from 17,375 to 30,644 cases, and chlamydia increased 22% to 1.7 million cases.

According to a 2013 CDC infographic shown by Dr. Straub, young people in the United States aged 15-24 years old represent 27% of the total sexually active population but account for 50% of new STI cases each year. Persons in this population account for 70% of gonorrhea cases, 63% of chlamydia cases, 49% of human papillomavirus (HPV) cases, 45% of genital herpes cases, and 20% of syphilis cases.

All sexually active females aged 25 years or younger should be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea, as well as “at-risk” young men who have sex with men (YMSM), Dr. Straub said. All adolescent males and females aged over 13 years should be offered HIV screening, and HIV screening should be discussed “at least once.” And depending on how at risk each subpopulation is, health care providers should be have that conversation and offer screening multiple times.

Women who have sex with women (WSW) are a diverse population and should be treated based on their individual sexual identities, behaviors, and practices. “Most self-identified WSWs report having sex with men, so therefore adolescent WSWs and females with both male and female sex partners might be at increased risk for STIs, such as syphillis, chlamydia, and HPV as well as HIV, so you may want to adjust your screening accordingly,” she said.

Pregnant women, if at risk, should be screened for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

YMSM should have annual screenings for syphilis and HIV, screenings for chlamydia and gonorrhea by infection site; also consider herpes simplex virus serology and anal cytology in these patients, Dr. Straub said. They also should be screened for hepatitis B surface antigen, vaccinated for hepatitis A, hepatitis B and, if using drugs, screened* for hepatitis C virus.

Dr. Straub recommended licensed health care professionals who may treat minor patients review their state’s laws on minors and their legal ability to consent to treatment of STIs without the involvement of their parent or guardian, including disclosure of positive results and in the case of HIV care.

In places where index insured are allowed to find out about any services a beneficiary receives on their insurance, “this is a little problematic, because in some states, this is in direct conflict with the explanation of benefits requirement,” she said. “There are certain ways to get around that, but it’s really important for you to know what the statutes are where you’re practicing and where the breaches of confidentiality [are].”

Expedited partner therapy, or treating one or multiple partners of patients with an STI, is recommended for certain patients and infections, such as male partners of female patients with chlamydia and gonorrhea. While this is recommended less for YMSM because of a higher rate of concurrent infection, “if you have a young person who has partners who are unlikely to have access to care and get treated, it’s recommended you give that treatment to your index patient and to then treat their partners,” Dr. Straub said.

A recent and frequently updated resource on STI treatment can be found at the CDC website.

Dr. Straub reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated 1/11/19.

ORLANDO – Consider point-of-care testing and treat potentially infected partners when diagnosing and treating adolescents for STIs, Diane M. Straub, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, adolescents are sometimes reluctant to disclose their full sexual history to their health care provider, which can complicate diagnosis and treatment, noted Dr. Straub, professor of pediatrics at the University of South Florida, Tampa. “That sometimes takes a few questions,” but can be achieved by asking the same questions in different ways and emphasizing the clinical importance of testing.

According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey, 40% of adolescents reported ever having sexual intercourse, with 20% of 9th-grade, 36% of 10th-grade, 47% of 11th-grade, and 57% of 12th-grade students reporting they had sexual intercourse. By gender, 41% of adolescent males and 38% of adolescent females reported ever having sexual intercourse; by race, 39% of white, 41% of Hispanic, and 46% of black participants reported any sexual activity. Overall, 10% of adolescents said they had four or more partners, 3% said they had intercourse before age 13 years, 54% used a condom the last time they had intercourse, and 7% said they were raped.

The rate of STIs in the United States is rising. There has been a sharp increase in the number of combined diagnoses of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia, with an increase from 1.8 million in 2013 to 2.3 million cases in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time period, gonorrhea increased 67% from 333,004 to 555,608 cases, syphilis (primary and secondary) rose 76% from 17,375 to 30,644 cases, and chlamydia increased 22% to 1.7 million cases.

According to a 2013 CDC infographic shown by Dr. Straub, young people in the United States aged 15-24 years old represent 27% of the total sexually active population but account for 50% of new STI cases each year. Persons in this population account for 70% of gonorrhea cases, 63% of chlamydia cases, 49% of human papillomavirus (HPV) cases, 45% of genital herpes cases, and 20% of syphilis cases.

All sexually active females aged 25 years or younger should be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea, as well as “at-risk” young men who have sex with men (YMSM), Dr. Straub said. All adolescent males and females aged over 13 years should be offered HIV screening, and HIV screening should be discussed “at least once.” And depending on how at risk each subpopulation is, health care providers should be have that conversation and offer screening multiple times.

Women who have sex with women (WSW) are a diverse population and should be treated based on their individual sexual identities, behaviors, and practices. “Most self-identified WSWs report having sex with men, so therefore adolescent WSWs and females with both male and female sex partners might be at increased risk for STIs, such as syphillis, chlamydia, and HPV as well as HIV, so you may want to adjust your screening accordingly,” she said.

Pregnant women, if at risk, should be screened for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

YMSM should have annual screenings for syphilis and HIV, screenings for chlamydia and gonorrhea by infection site; also consider herpes simplex virus serology and anal cytology in these patients, Dr. Straub said. They also should be screened for hepatitis B surface antigen, vaccinated for hepatitis A, hepatitis B and, if using drugs, screened* for hepatitis C virus.

Dr. Straub recommended licensed health care professionals who may treat minor patients review their state’s laws on minors and their legal ability to consent to treatment of STIs without the involvement of their parent or guardian, including disclosure of positive results and in the case of HIV care.

In places where index insured are allowed to find out about any services a beneficiary receives on their insurance, “this is a little problematic, because in some states, this is in direct conflict with the explanation of benefits requirement,” she said. “There are certain ways to get around that, but it’s really important for you to know what the statutes are where you’re practicing and where the breaches of confidentiality [are].”

Expedited partner therapy, or treating one or multiple partners of patients with an STI, is recommended for certain patients and infections, such as male partners of female patients with chlamydia and gonorrhea. While this is recommended less for YMSM because of a higher rate of concurrent infection, “if you have a young person who has partners who are unlikely to have access to care and get treated, it’s recommended you give that treatment to your index patient and to then treat their partners,” Dr. Straub said.

A recent and frequently updated resource on STI treatment can be found at the CDC website.

Dr. Straub reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated 1/11/19.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 18

Discussing immunization with vaccine-hesitant parents requires caring, individualized approach

ORLANDO – Putting parents at ease, making vaccination the default option during discussions, appealing to their identity as a good parent, and focusing on positive word choice during discussions are the techniques two pediatricians have recommended using to get vaccine-hesitant parents to immunize their children.

“Your goal is to get parents to immunize their kids,” Katrina Saba, MD, of the Permanente Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., said during an interactive group panel at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Our goal is not to win a debate. You don’t have to correct every mistaken idea.”

“And really importantly, as we know, belief trumps science,” she added. “Their belief is so much stronger than our proof, and their belief will not be changed by evidence.”

Many parents who are vaccine- hesitant also belong to a social network that forms or reinforces their beliefs, and attacking those beliefs is the same as attacking their identity, Dr. Saba noted. “When you attack someone’s identity, you are immediately seen as not like them, and if you’re not like them, you’ve lost your strength in persuading them.”

Dr. Saba; Kenneth Hempstead, MD; and other pediatricians and educators in the Permanente Medical Group developed a framework for pediatricians and educators to talk with their patients about immunization at their center after California passed a law in 2013 that required health care professionals to discuss vaccines with patients and sign off that they had that discussion.

“We felt that, if we were going to be by law required to have that discussion, maybe we needed some new tools to have [the discussion] more effectively,” Dr. Saba said. “Because clearly, [what we were doing ] wasn’t working or there wouldn’t have been a need for that law.”

Dr. Hempstead explained the concerns of three major categories of vaccine-hesitant parents: those patients who are unsure of whether they should vaccinate, parents who wish to delay vaccination, and parents who refuse vaccination of their children.

Each parent requires a different approach for discussing the importance of vaccination based on their level of vaccine hesitancy, he said. For parents who are unsure, they may require general information about the safety and importance of vaccines.

Parents who delay immunization may have less trust in vaccines, have done research in their own social networks, and may present alternatives to a standard immunization schedule or want to omit certain vaccines from their child’s immunization schedule, he noted. Using the analogy of a car seat is one approach to identify the importance of vaccination to these parents: “Waiting to give the shots is like putting your baby in the car seat after you’ve already arrived at the store – the protection isn’t there for the most important part of the journey!”

In cases where parents refuse vaccination, you should not expect to change a parent’s mind in a single visit, but instead focus on building the patient-provider bond. However, presenting information the parent may have already seen, such as vaccination data from the Food and Drug Administration or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, may alienate parents who identify with groups that share vaccine-hesitant viewpoints and erode your ability to persuade a parent’s intent to vaccinate.

A study by Nyhan et al. randomized parents to receive one of four pieces of interventions about the MMR vaccine: information from the CDC explaining the lack of evidence linking autism and the vaccine, information about the dangers of the diseases prevented by the vaccine, images of children who have had diseases prevented by the vaccine, and a “dramatic narrative” from a CDC fact sheet about a child who nearly died of measles. The researchers found no informational intervention helped in persuading to vaccinate in parents who had the “least favorable” attitudes toward the vaccine. And in the case of the dramatic narrative, there was an increased misperception about the MMR vaccine (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e835-e842).

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba outlined four rhetorical devices to include in conversations with patients about vaccination: cognitive ease, natural assumption, appeal to identity, and using advantageous terms.

Cognitive ease

Cognitive ease means creating an environment in which the patient is relaxed, comfortable, and more likely to be agreeable. Recognize when the tone shifts, and strive to maintain this calm and comfortable environment throughout the discussion. “If your blood pressure is coming up, that means theirs is, too,” Dr. Hempstead said.

Natural assumption

How you are offering the vaccination also matters, he added. Rather than asking whether a patient wants to vaccinate (“Have you thought about your flu vaccine this year?”), instead frame the discussion with vaccination as the default option (“Is your child due for a flu vaccination this year? Yes, he is. Let’s get that taken care of today”). Equating inaction with vaccination prevents the risk fallacy phenomenon from occurring in which, when given multiple options, people give equal weight to each option and may choose not to vaccinate, Dr. Hempstead noted.

Dr. Saba cited research that backed this approach. In a study by Opel et al., using a “presumptive” approach instead of a “participatory” approach when discussing a provider’s recommendation to vaccinate helped: The presumptive conversations had an odds ratio of 17.5, compared with the participatory approach. In cases in which parents resisted the provider’s recommendations, 50% of providers persisted with their original recommendations, and 47% of parents who initially resisted the recommendations agreed to vaccinate (Pediatrics. 2013;132[6]:1037-46).

Appeal to identity

Another strategy to use is appealing to the patient’s identity as a good parent and link the concept of vaccination with the good parent identity. Forging a new common identity with the parents through common beliefs – such as recognizing that networks to which parents belong are an important part of his or her identify – and reemphasizing the mutual desire to protect the child is another strategy.

Using advantageous terms

Positive terms, such as “protection,” “health,” “safety,” and “what’s best,” are much better words to use in conversation with parents and have more staying power than negative terms, like “autism” and “side effects,” Dr. Hempstead said.

“Stay with positive messaging,” he said. “Immediately coming back to the positive impact of this vaccine, why we care so much, why we’re doing this vaccine, is absolutely critical.”

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Putting parents at ease, making vaccination the default option during discussions, appealing to their identity as a good parent, and focusing on positive word choice during discussions are the techniques two pediatricians have recommended using to get vaccine-hesitant parents to immunize their children.

“Your goal is to get parents to immunize their kids,” Katrina Saba, MD, of the Permanente Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., said during an interactive group panel at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Our goal is not to win a debate. You don’t have to correct every mistaken idea.”

“And really importantly, as we know, belief trumps science,” she added. “Their belief is so much stronger than our proof, and their belief will not be changed by evidence.”

Many parents who are vaccine- hesitant also belong to a social network that forms or reinforces their beliefs, and attacking those beliefs is the same as attacking their identity, Dr. Saba noted. “When you attack someone’s identity, you are immediately seen as not like them, and if you’re not like them, you’ve lost your strength in persuading them.”

Dr. Saba; Kenneth Hempstead, MD; and other pediatricians and educators in the Permanente Medical Group developed a framework for pediatricians and educators to talk with their patients about immunization at their center after California passed a law in 2013 that required health care professionals to discuss vaccines with patients and sign off that they had that discussion.

“We felt that, if we were going to be by law required to have that discussion, maybe we needed some new tools to have [the discussion] more effectively,” Dr. Saba said. “Because clearly, [what we were doing ] wasn’t working or there wouldn’t have been a need for that law.”

Dr. Hempstead explained the concerns of three major categories of vaccine-hesitant parents: those patients who are unsure of whether they should vaccinate, parents who wish to delay vaccination, and parents who refuse vaccination of their children.

Each parent requires a different approach for discussing the importance of vaccination based on their level of vaccine hesitancy, he said. For parents who are unsure, they may require general information about the safety and importance of vaccines.

Parents who delay immunization may have less trust in vaccines, have done research in their own social networks, and may present alternatives to a standard immunization schedule or want to omit certain vaccines from their child’s immunization schedule, he noted. Using the analogy of a car seat is one approach to identify the importance of vaccination to these parents: “Waiting to give the shots is like putting your baby in the car seat after you’ve already arrived at the store – the protection isn’t there for the most important part of the journey!”

In cases where parents refuse vaccination, you should not expect to change a parent’s mind in a single visit, but instead focus on building the patient-provider bond. However, presenting information the parent may have already seen, such as vaccination data from the Food and Drug Administration or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, may alienate parents who identify with groups that share vaccine-hesitant viewpoints and erode your ability to persuade a parent’s intent to vaccinate.

A study by Nyhan et al. randomized parents to receive one of four pieces of interventions about the MMR vaccine: information from the CDC explaining the lack of evidence linking autism and the vaccine, information about the dangers of the diseases prevented by the vaccine, images of children who have had diseases prevented by the vaccine, and a “dramatic narrative” from a CDC fact sheet about a child who nearly died of measles. The researchers found no informational intervention helped in persuading to vaccinate in parents who had the “least favorable” attitudes toward the vaccine. And in the case of the dramatic narrative, there was an increased misperception about the MMR vaccine (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e835-e842).

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba outlined four rhetorical devices to include in conversations with patients about vaccination: cognitive ease, natural assumption, appeal to identity, and using advantageous terms.

Cognitive ease

Cognitive ease means creating an environment in which the patient is relaxed, comfortable, and more likely to be agreeable. Recognize when the tone shifts, and strive to maintain this calm and comfortable environment throughout the discussion. “If your blood pressure is coming up, that means theirs is, too,” Dr. Hempstead said.

Natural assumption

How you are offering the vaccination also matters, he added. Rather than asking whether a patient wants to vaccinate (“Have you thought about your flu vaccine this year?”), instead frame the discussion with vaccination as the default option (“Is your child due for a flu vaccination this year? Yes, he is. Let’s get that taken care of today”). Equating inaction with vaccination prevents the risk fallacy phenomenon from occurring in which, when given multiple options, people give equal weight to each option and may choose not to vaccinate, Dr. Hempstead noted.

Dr. Saba cited research that backed this approach. In a study by Opel et al., using a “presumptive” approach instead of a “participatory” approach when discussing a provider’s recommendation to vaccinate helped: The presumptive conversations had an odds ratio of 17.5, compared with the participatory approach. In cases in which parents resisted the provider’s recommendations, 50% of providers persisted with their original recommendations, and 47% of parents who initially resisted the recommendations agreed to vaccinate (Pediatrics. 2013;132[6]:1037-46).

Appeal to identity

Another strategy to use is appealing to the patient’s identity as a good parent and link the concept of vaccination with the good parent identity. Forging a new common identity with the parents through common beliefs – such as recognizing that networks to which parents belong are an important part of his or her identify – and reemphasizing the mutual desire to protect the child is another strategy.

Using advantageous terms

Positive terms, such as “protection,” “health,” “safety,” and “what’s best,” are much better words to use in conversation with parents and have more staying power than negative terms, like “autism” and “side effects,” Dr. Hempstead said.

“Stay with positive messaging,” he said. “Immediately coming back to the positive impact of this vaccine, why we care so much, why we’re doing this vaccine, is absolutely critical.”

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Putting parents at ease, making vaccination the default option during discussions, appealing to their identity as a good parent, and focusing on positive word choice during discussions are the techniques two pediatricians have recommended using to get vaccine-hesitant parents to immunize their children.

“Your goal is to get parents to immunize their kids,” Katrina Saba, MD, of the Permanente Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., said during an interactive group panel at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Our goal is not to win a debate. You don’t have to correct every mistaken idea.”

“And really importantly, as we know, belief trumps science,” she added. “Their belief is so much stronger than our proof, and their belief will not be changed by evidence.”

Many parents who are vaccine- hesitant also belong to a social network that forms or reinforces their beliefs, and attacking those beliefs is the same as attacking their identity, Dr. Saba noted. “When you attack someone’s identity, you are immediately seen as not like them, and if you’re not like them, you’ve lost your strength in persuading them.”

Dr. Saba; Kenneth Hempstead, MD; and other pediatricians and educators in the Permanente Medical Group developed a framework for pediatricians and educators to talk with their patients about immunization at their center after California passed a law in 2013 that required health care professionals to discuss vaccines with patients and sign off that they had that discussion.

“We felt that, if we were going to be by law required to have that discussion, maybe we needed some new tools to have [the discussion] more effectively,” Dr. Saba said. “Because clearly, [what we were doing ] wasn’t working or there wouldn’t have been a need for that law.”

Dr. Hempstead explained the concerns of three major categories of vaccine-hesitant parents: those patients who are unsure of whether they should vaccinate, parents who wish to delay vaccination, and parents who refuse vaccination of their children.

Each parent requires a different approach for discussing the importance of vaccination based on their level of vaccine hesitancy, he said. For parents who are unsure, they may require general information about the safety and importance of vaccines.

Parents who delay immunization may have less trust in vaccines, have done research in their own social networks, and may present alternatives to a standard immunization schedule or want to omit certain vaccines from their child’s immunization schedule, he noted. Using the analogy of a car seat is one approach to identify the importance of vaccination to these parents: “Waiting to give the shots is like putting your baby in the car seat after you’ve already arrived at the store – the protection isn’t there for the most important part of the journey!”

In cases where parents refuse vaccination, you should not expect to change a parent’s mind in a single visit, but instead focus on building the patient-provider bond. However, presenting information the parent may have already seen, such as vaccination data from the Food and Drug Administration or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, may alienate parents who identify with groups that share vaccine-hesitant viewpoints and erode your ability to persuade a parent’s intent to vaccinate.

A study by Nyhan et al. randomized parents to receive one of four pieces of interventions about the MMR vaccine: information from the CDC explaining the lack of evidence linking autism and the vaccine, information about the dangers of the diseases prevented by the vaccine, images of children who have had diseases prevented by the vaccine, and a “dramatic narrative” from a CDC fact sheet about a child who nearly died of measles. The researchers found no informational intervention helped in persuading to vaccinate in parents who had the “least favorable” attitudes toward the vaccine. And in the case of the dramatic narrative, there was an increased misperception about the MMR vaccine (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e835-e842).

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba outlined four rhetorical devices to include in conversations with patients about vaccination: cognitive ease, natural assumption, appeal to identity, and using advantageous terms.

Cognitive ease

Cognitive ease means creating an environment in which the patient is relaxed, comfortable, and more likely to be agreeable. Recognize when the tone shifts, and strive to maintain this calm and comfortable environment throughout the discussion. “If your blood pressure is coming up, that means theirs is, too,” Dr. Hempstead said.

Natural assumption

How you are offering the vaccination also matters, he added. Rather than asking whether a patient wants to vaccinate (“Have you thought about your flu vaccine this year?”), instead frame the discussion with vaccination as the default option (“Is your child due for a flu vaccination this year? Yes, he is. Let’s get that taken care of today”). Equating inaction with vaccination prevents the risk fallacy phenomenon from occurring in which, when given multiple options, people give equal weight to each option and may choose not to vaccinate, Dr. Hempstead noted.

Dr. Saba cited research that backed this approach. In a study by Opel et al., using a “presumptive” approach instead of a “participatory” approach when discussing a provider’s recommendation to vaccinate helped: The presumptive conversations had an odds ratio of 17.5, compared with the participatory approach. In cases in which parents resisted the provider’s recommendations, 50% of providers persisted with their original recommendations, and 47% of parents who initially resisted the recommendations agreed to vaccinate (Pediatrics. 2013;132[6]:1037-46).

Appeal to identity

Another strategy to use is appealing to the patient’s identity as a good parent and link the concept of vaccination with the good parent identity. Forging a new common identity with the parents through common beliefs – such as recognizing that networks to which parents belong are an important part of his or her identify – and reemphasizing the mutual desire to protect the child is another strategy.

Using advantageous terms

Positive terms, such as “protection,” “health,” “safety,” and “what’s best,” are much better words to use in conversation with parents and have more staying power than negative terms, like “autism” and “side effects,” Dr. Hempstead said.

“Stay with positive messaging,” he said. “Immediately coming back to the positive impact of this vaccine, why we care so much, why we’re doing this vaccine, is absolutely critical.”

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 18

Many teens don’t know e-cigarettes contain nicotine

ORLANDO – Flavoring and lack of Food and Drug Administration regulation of e-cigarettes has led to more children and adolescents using these devices, according to American Academy of Pediatrics President Colleen A. Kraft, MD.

In an interview, Dr. Kraft said the FDA should regulate these products and limit their purchase to adults who are at least 21 years old. E-cigarettes were initially intended as an aid for adults to reduce their cigarette use, but the addition of flavoring has attracted children and adolescents to the devices, Dr. Kraft noted.

“When you have these devices that have flavors like gummy bear and cotton candy and bubblegum, you are marketing to children, and we are calling out the FDA because they could actually stop this today,” she said. In fact, Dr. Kraft added, many children and adolescents don’t even realize that e-cigarettes contain nicotine.

Dr. Kraft reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Flavoring and lack of Food and Drug Administration regulation of e-cigarettes has led to more children and adolescents using these devices, according to American Academy of Pediatrics President Colleen A. Kraft, MD.

In an interview, Dr. Kraft said the FDA should regulate these products and limit their purchase to adults who are at least 21 years old. E-cigarettes were initially intended as an aid for adults to reduce their cigarette use, but the addition of flavoring has attracted children and adolescents to the devices, Dr. Kraft noted.

“When you have these devices that have flavors like gummy bear and cotton candy and bubblegum, you are marketing to children, and we are calling out the FDA because they could actually stop this today,” she said. In fact, Dr. Kraft added, many children and adolescents don’t even realize that e-cigarettes contain nicotine.

Dr. Kraft reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Flavoring and lack of Food and Drug Administration regulation of e-cigarettes has led to more children and adolescents using these devices, according to American Academy of Pediatrics President Colleen A. Kraft, MD.

In an interview, Dr. Kraft said the FDA should regulate these products and limit their purchase to adults who are at least 21 years old. E-cigarettes were initially intended as an aid for adults to reduce their cigarette use, but the addition of flavoring has attracted children and adolescents to the devices, Dr. Kraft noted.

“When you have these devices that have flavors like gummy bear and cotton candy and bubblegum, you are marketing to children, and we are calling out the FDA because they could actually stop this today,” she said. In fact, Dr. Kraft added, many children and adolescents don’t even realize that e-cigarettes contain nicotine.

Dr. Kraft reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AAP 2018

Communicate with Millennials using their preferred methods

ORLANDO – Pediatricians can learn from how Millennials use services and purchase products from popular companies, such as Amazon Alexa, Warby Parker, Instagram, and Snapchat, and use that information to connect with Millennial parents and children in their practice, Kristopher Jones, JD, MS, said.

In a video interview, Mr. Jones explained how Amazon Alexa uses structured data as recommendations when users make queries of the service; for example, a Millennial might make a choice to book an appointment with a pediatrician based on the results Amazon Alexa displays, such as an office’s available hours. An office that is not optimized to appear in those results would be missed by those potential patients.

Warby Parker has a digital-first strategy focused on convenience, ease of use, and an emphasis on mission; one opportunity for pediatricians in this area is to be more overt about which causes they are supporting, Mr. Jones said. In the case of Instagram and Snapchat, pediatricians should consider creating a presence on these platforms and focusing on less text-heavy content to appeal to Millennials.

“It’s a really, really important opportunity to be able to meet the Millennials where they want to be met, and that means developing strategies to leveraging pictures and videos and other forms of Millennial content to communicate with them,” he said.

Mr. Jones reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Pediatricians can learn from how Millennials use services and purchase products from popular companies, such as Amazon Alexa, Warby Parker, Instagram, and Snapchat, and use that information to connect with Millennial parents and children in their practice, Kristopher Jones, JD, MS, said.

In a video interview, Mr. Jones explained how Amazon Alexa uses structured data as recommendations when users make queries of the service; for example, a Millennial might make a choice to book an appointment with a pediatrician based on the results Amazon Alexa displays, such as an office’s available hours. An office that is not optimized to appear in those results would be missed by those potential patients.

Warby Parker has a digital-first strategy focused on convenience, ease of use, and an emphasis on mission; one opportunity for pediatricians in this area is to be more overt about which causes they are supporting, Mr. Jones said. In the case of Instagram and Snapchat, pediatricians should consider creating a presence on these platforms and focusing on less text-heavy content to appeal to Millennials.

“It’s a really, really important opportunity to be able to meet the Millennials where they want to be met, and that means developing strategies to leveraging pictures and videos and other forms of Millennial content to communicate with them,” he said.

Mr. Jones reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Pediatricians can learn from how Millennials use services and purchase products from popular companies, such as Amazon Alexa, Warby Parker, Instagram, and Snapchat, and use that information to connect with Millennial parents and children in their practice, Kristopher Jones, JD, MS, said.

In a video interview, Mr. Jones explained how Amazon Alexa uses structured data as recommendations when users make queries of the service; for example, a Millennial might make a choice to book an appointment with a pediatrician based on the results Amazon Alexa displays, such as an office’s available hours. An office that is not optimized to appear in those results would be missed by those potential patients.

Warby Parker has a digital-first strategy focused on convenience, ease of use, and an emphasis on mission; one opportunity for pediatricians in this area is to be more overt about which causes they are supporting, Mr. Jones said. In the case of Instagram and Snapchat, pediatricians should consider creating a presence on these platforms and focusing on less text-heavy content to appeal to Millennials.

“It’s a really, really important opportunity to be able to meet the Millennials where they want to be met, and that means developing strategies to leveraging pictures and videos and other forms of Millennial content to communicate with them,” he said.

Mr. Jones reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AAP 2018

AAP strengthens stance against corporal punishment

ORLANDO – The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a new policy statement taking a stronger stance against corporal punishment, including spanking, 20 years after releasing its last position statement on effective discipline.

The 1998 policy statement discouraged the use of corporal punishment and encouraged parents to seek other ways to discipline their children, while the latest statement goes further, citing the latest research showing corporal punishment’s harmful effects on children and encouraging pediatricians to counsel parents about the harms of corporal punishment and offer alternative forms of discipline. The 2018 policy statement will be published in the December issue of Pediatrics.

Support for corporal punishment, such as spanking, is declining. According to the Child Trends data bank, 76% of men and 66% of women supported spanking in some cases, compared with 84% of men and 82% of women in 1986. In its latest statement, the AAP noted that 6% of pediatricians (92% in primary care) supported spanking in a 2016 survey of 787 pediatricians.

In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Ryan D. Brown, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, noted that studies have shown children who are spanked are more likely to exhibit mental health problems, antisocial behavior, aggression, negative relationships with a parent, low self-esteem, externalizing behavior such as acting out, substance abuse, low moral internalization, and are more likely to be victims of physical abuse. He cited a study showing that children who were spanked one time per month had a 14%-19% reduction in the decision making area of their brains (Neuroimage. 2009 Aug;47 Suppl 2:T66-T71) and another study showing that children spanked aged between 2 and 9 years had 2.8-5.0 fewer IQ points than children who were not spanked (J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2009 Jul 22;18[5]:459-83).

Science has shown that there are more effective ways of disciplining children, and pediatricians are the experts who can explain the difference between discipline and punishment. Parents can use discipline as a teaching opportunity while corporal punishment inflicts physical pain on children with the intent to modify behavior. However, this does not train children to learn. “We want to teach our children to grow,” Dr. Brown said.

He pointed out the AAP’s policy on ipecac syrup and erythromycin/sulfafurazole for otitis media as examples of recommendations changing when more scientific data becomes available.

“[W]hen we get parents that say, ‘You know what? I was spanked as a kid and I turned out okay,’ I said, ‘You know, I rode in a car without a seat belt, but science has shown seat belts are effective,’ ” Dr. Brown said.

Instead of spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, parents should practice positive parenting, such as telling a child when they are being “good,” so children understand what good behavior looks like to build up self-esteem. Parents also should play with their children daily and provide simple, easy-to-understand commands. “Interact with the kids so they can see what is good behavior,” he said.

Disciplining children should be swift, age appropriate relative to mental rather than chronological age, and the discipline should “fit the crime,” Dr. Brown said. Parents also should not discipline a child in accidental situations, such as dropping a glass when helping clean up the dinner table, he added.

“The only time I kind of say that [discipline] should be delayed is in kids [who] understand the delay,” such as teenagers, Dr. Brown added.

Pediatricians can implement the new guidelines in their practices by providing resources to parents about alternative forms of discipline, such as the AAP sites HealthyChildren.org and Connected Kids, training office staff in diffusing stressful situations between a caregiver and a child, and making their office a “no hit zone” for caregivers and children.

Dr. Brown reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a new policy statement taking a stronger stance against corporal punishment, including spanking, 20 years after releasing its last position statement on effective discipline.

The 1998 policy statement discouraged the use of corporal punishment and encouraged parents to seek other ways to discipline their children, while the latest statement goes further, citing the latest research showing corporal punishment’s harmful effects on children and encouraging pediatricians to counsel parents about the harms of corporal punishment and offer alternative forms of discipline. The 2018 policy statement will be published in the December issue of Pediatrics.

Support for corporal punishment, such as spanking, is declining. According to the Child Trends data bank, 76% of men and 66% of women supported spanking in some cases, compared with 84% of men and 82% of women in 1986. In its latest statement, the AAP noted that 6% of pediatricians (92% in primary care) supported spanking in a 2016 survey of 787 pediatricians.

In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Ryan D. Brown, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, noted that studies have shown children who are spanked are more likely to exhibit mental health problems, antisocial behavior, aggression, negative relationships with a parent, low self-esteem, externalizing behavior such as acting out, substance abuse, low moral internalization, and are more likely to be victims of physical abuse. He cited a study showing that children who were spanked one time per month had a 14%-19% reduction in the decision making area of their brains (Neuroimage. 2009 Aug;47 Suppl 2:T66-T71) and another study showing that children spanked aged between 2 and 9 years had 2.8-5.0 fewer IQ points than children who were not spanked (J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2009 Jul 22;18[5]:459-83).

Science has shown that there are more effective ways of disciplining children, and pediatricians are the experts who can explain the difference between discipline and punishment. Parents can use discipline as a teaching opportunity while corporal punishment inflicts physical pain on children with the intent to modify behavior. However, this does not train children to learn. “We want to teach our children to grow,” Dr. Brown said.

He pointed out the AAP’s policy on ipecac syrup and erythromycin/sulfafurazole for otitis media as examples of recommendations changing when more scientific data becomes available.

“[W]hen we get parents that say, ‘You know what? I was spanked as a kid and I turned out okay,’ I said, ‘You know, I rode in a car without a seat belt, but science has shown seat belts are effective,’ ” Dr. Brown said.

Instead of spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, parents should practice positive parenting, such as telling a child when they are being “good,” so children understand what good behavior looks like to build up self-esteem. Parents also should play with their children daily and provide simple, easy-to-understand commands. “Interact with the kids so they can see what is good behavior,” he said.

Disciplining children should be swift, age appropriate relative to mental rather than chronological age, and the discipline should “fit the crime,” Dr. Brown said. Parents also should not discipline a child in accidental situations, such as dropping a glass when helping clean up the dinner table, he added.

“The only time I kind of say that [discipline] should be delayed is in kids [who] understand the delay,” such as teenagers, Dr. Brown added.

Pediatricians can implement the new guidelines in their practices by providing resources to parents about alternative forms of discipline, such as the AAP sites HealthyChildren.org and Connected Kids, training office staff in diffusing stressful situations between a caregiver and a child, and making their office a “no hit zone” for caregivers and children.

Dr. Brown reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a new policy statement taking a stronger stance against corporal punishment, including spanking, 20 years after releasing its last position statement on effective discipline.

The 1998 policy statement discouraged the use of corporal punishment and encouraged parents to seek other ways to discipline their children, while the latest statement goes further, citing the latest research showing corporal punishment’s harmful effects on children and encouraging pediatricians to counsel parents about the harms of corporal punishment and offer alternative forms of discipline. The 2018 policy statement will be published in the December issue of Pediatrics.

Support for corporal punishment, such as spanking, is declining. According to the Child Trends data bank, 76% of men and 66% of women supported spanking in some cases, compared with 84% of men and 82% of women in 1986. In its latest statement, the AAP noted that 6% of pediatricians (92% in primary care) supported spanking in a 2016 survey of 787 pediatricians.

In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Ryan D. Brown, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, noted that studies have shown children who are spanked are more likely to exhibit mental health problems, antisocial behavior, aggression, negative relationships with a parent, low self-esteem, externalizing behavior such as acting out, substance abuse, low moral internalization, and are more likely to be victims of physical abuse. He cited a study showing that children who were spanked one time per month had a 14%-19% reduction in the decision making area of their brains (Neuroimage. 2009 Aug;47 Suppl 2:T66-T71) and another study showing that children spanked aged between 2 and 9 years had 2.8-5.0 fewer IQ points than children who were not spanked (J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2009 Jul 22;18[5]:459-83).

Science has shown that there are more effective ways of disciplining children, and pediatricians are the experts who can explain the difference between discipline and punishment. Parents can use discipline as a teaching opportunity while corporal punishment inflicts physical pain on children with the intent to modify behavior. However, this does not train children to learn. “We want to teach our children to grow,” Dr. Brown said.

He pointed out the AAP’s policy on ipecac syrup and erythromycin/sulfafurazole for otitis media as examples of recommendations changing when more scientific data becomes available.

“[W]hen we get parents that say, ‘You know what? I was spanked as a kid and I turned out okay,’ I said, ‘You know, I rode in a car without a seat belt, but science has shown seat belts are effective,’ ” Dr. Brown said.

Instead of spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, parents should practice positive parenting, such as telling a child when they are being “good,” so children understand what good behavior looks like to build up self-esteem. Parents also should play with their children daily and provide simple, easy-to-understand commands. “Interact with the kids so they can see what is good behavior,” he said.

Disciplining children should be swift, age appropriate relative to mental rather than chronological age, and the discipline should “fit the crime,” Dr. Brown said. Parents also should not discipline a child in accidental situations, such as dropping a glass when helping clean up the dinner table, he added.

“The only time I kind of say that [discipline] should be delayed is in kids [who] understand the delay,” such as teenagers, Dr. Brown added.

Pediatricians can implement the new guidelines in their practices by providing resources to parents about alternative forms of discipline, such as the AAP sites HealthyChildren.org and Connected Kids, training office staff in diffusing stressful situations between a caregiver and a child, and making their office a “no hit zone” for caregivers and children.

Dr. Brown reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AAP 2018

Most kids can’t tell real firearms from toy guns

ORLANDO – Less than half of children could identify a real gun from a toy gun in photos, regardless of whether their parents owned a gun or had talked to them about firearm safety, according to a new study.

“That is very concerning to us because a large percentage of these parents are actually storing their firearms insecurely and then their children cannot tell the difference,” study investigator Kiesha Fraser Doh, MD, reported at the annual conference of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Fraser Doh, assistant professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine physician at Emory University School of Medicine and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta said she was inspired to conduct this study after she noticed she was seeing approximately one firearm injury in children about every 2½ weeks in her institution. She also realized that her own child frequently went on play dates, but she did not always think to ask about firearms in the home of the friends her child visited.

An estimated one in three U.S. children live in homes with a firearm, she explained, and many of these guns are left loaded and/or unlocked.

The researchers enrolled a convenience sample of 297 English-speaking caregivers who presented at one of three pediatrics EDs over 3 months. Two were suburban departments, and one was urban.

Overall, most respondents (79%) were female and 56% were black, while 33% were white. Most of the caregivers responding had some college education (72%), and just over half (51%) had an income greater than $50,000.

The researchers asked caregivers whether they had guns in their own home and whether their child had access to firearms in their own or other homes. They also asked if their child played with toy guns and whether they believed their child could tell the difference between a real gun and a toy one.

Compared with those who did not own guns, gun owners were significantly more likely to be white and have both an income over $50,000 and some college education.

Meanwhile, researchers showed the children, aged 7-17 years, photos of a toy gun and a real gun and asked which was which.

A quarter of the caregivers (25%) owned guns, and half of them (50%) allowed their children to play with guns, compared with 26% of the non-gun owners.

In addition, 86% of the gun owners had discussed gun safety with their children, and the same proportion believed their children could correctly distinguish between a real gun and a toy gun.

By comparison, 58% of the non-gun owners had discussed gun safety with their children, and the same percentage believed their children could tell the difference between real and fake guns.

The children’s confidence in being able to tell the difference was similar regardless of whether their parents owned guns (79%) or didn’t (76%).

Yet less than half of all children correctly identified the real gun in the photos: 39% of the gun owners’ children and 42% of the non-gun owners’ children correctly pointed out the real gun, a nonsignificant difference.

Throughout the entire sample, more than 8 in 10 respondents, both gun owners (86%) and not (84%), believed there should be a law that requires caregivers to store their guns safely. A similar proportion (85% of gun owners and 80% of non-gun owners) believed legal penalties should exist for caregivers “if a child encounters an unsecured firearm.”

Overall, 5% of the respondents (14% of gun owners and 4% of non-gun owners) believed their child could get a gun within 24 hours if desired.

“So what does this mean to us as clinicians? It behooves [pediatricians] to actually continue to educate families at well-child visits on the guidelines about how to store firearms safely, locked up, unloaded, separate from ammunition,” Dr. Fraser Doh said. “On the flip side, parents need to be asking about the presence of firearms in the homes their children visit and also make sure that they’re storing their weapons safety.”

Dr. Fraser Doh said she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Less than half of children could distinguish between photos of a real gun versus pictures of a toy gun.

Major finding: 39% of the gun owners’ children and 42% of the non–gun owners’ children correctly identified the photo of a real gun versus a toy gun.

Study details: The findings are based on a study involving 297 English-speaking children, aged 7-17 years, and their parents.

Key clinical point: Less than half of children could distinguish between photos of a real gun versus pictures of a toy gun.

Major finding: 39% of the gun owners’ children and 42% of the non–gun owners’ children correctly identified the photo of a real gun versus a toy gun.