User login

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 2017 National Conference and Exhibition

Evidence-backed questions can guide a GERD vs. NERD differential diagnosis

CHICAGO – when doing a differential diagnosis. Fortunately, five questions backed by increasing evidence can help you make the call.

“Everyone in the room knows babies puke, and babies can puke a lot,” Barry K. Wershil, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. The approach to diagnosing GERD is age specific. “Kids who puke tend to outgrow it over time. With development, 95% or more are no longer refluxing at 18 months of age.”

“So generally there is no reason to initially refer older children and teenagers to a gastroenterologist,” Dr. Wershil said. “One of the essential things [you] do is consider all the causes of vomiting that are not GERD. If your first go-to is GERD, you’re going to miss other issues.”

Dr. Wershil reviewed the definitions: Gastroesophageal reflux is passage of gastric contents into the esophagus. GERD, on the other hand, is defined by the troublesome symptoms or complications associated with reflux of gastric material into the esophagus. In contrast, NERD is the presence of reflux symptoms with no evidence of mucosal erosion or mucosal breaks.

Considerations backed by evidence

Unfortunately, symptoms alone do not always differentiate erosive versus nonerosive esophagitis, Dr. Wershil said, although recurrent vomiting, poor weight gain, anemia, feeding problems, and respiratory problems can be signs of complicated GERD.

He recommended the following five considerations to distinguish GERD from NERD:

- Is the patient exhibiting normal weight gain? If not, ask questions about how the child is being fed. Have the parents started diluting the formula because they think that will take care of the vomiting? Have they begun limiting the amount of formula after observing that the child throws up at 4 ounces but not at 2 ounces?

- Is the patient bleeding or anemic? Hematemesis is rarely the presentation of infants with GERD, but anemia may be.

- Does the patient have respiratory problems (for example, a history of aspiration, recurring wheezing, or cough)?

- Is the patient neurologically normal? If so, that can present a special class of patients in which vomiting may not be just normal infant vomiting.

- Is the patient older than 2 years? We expect 95% of children to outgrow reflux by 18 months, and most children who have physiological reflux will outgrow it by 2 years.

“Those five questions in 1983 had little evidence, but in 2017 there is more evidence that these are the questions to focus on,” Dr. Wershil said.

The role of diagnostic testing

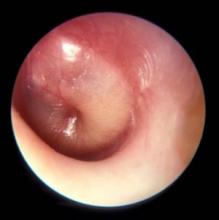

Diagnostic testing, such as pH monitoring, impedance testing, and endoscopy, can be useful in specific situations but carry limitations for widespread use, Dr. Wershil said. “Each test has reasons and limitations.”

An upper GI tract series looks only for anatomic anomalies, for example. pH monitoring is still used in many centers, but in general, impedance monitoring has become more common because it can detect both acid and nonacid reflux: “You can get a very detailed analysis of events happening in the esophagus over time.” One caveat Dr. Wershil added is that, “in some instances, we’re unsure how to define this in the pediatric age ranges we treat.”

Endoscopy has a limited role for the rare patients with mucosal changes or erosive esophagitis, he added. Endoscopy is ordered to detect mucosal changes that confirm esophageal erosion. “In all the kids we scope with positive pH, we rarely find erosive esophagitis,” Dr. Wershil said. “What we find more often is NERD. That really represents more of what we see in our patient population.”

“I hope this information is a good starting point to understand the algorithms that get generated,” Dr. Wershil said.

He recommended an algorithm for gastroesophageal reflux prepared by the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (Pediatrics. 2013 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0421). “I think this information is really solidly grounded in evidence.”

Dr. Wershil is a consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals; is a member of the speakers bureau for Abbott Nutrition, Mead Johnson Nutrition, and Nutricia; and receives funding from the National Institutes of Health Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers.

CHICAGO – when doing a differential diagnosis. Fortunately, five questions backed by increasing evidence can help you make the call.

“Everyone in the room knows babies puke, and babies can puke a lot,” Barry K. Wershil, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. The approach to diagnosing GERD is age specific. “Kids who puke tend to outgrow it over time. With development, 95% or more are no longer refluxing at 18 months of age.”

“So generally there is no reason to initially refer older children and teenagers to a gastroenterologist,” Dr. Wershil said. “One of the essential things [you] do is consider all the causes of vomiting that are not GERD. If your first go-to is GERD, you’re going to miss other issues.”

Dr. Wershil reviewed the definitions: Gastroesophageal reflux is passage of gastric contents into the esophagus. GERD, on the other hand, is defined by the troublesome symptoms or complications associated with reflux of gastric material into the esophagus. In contrast, NERD is the presence of reflux symptoms with no evidence of mucosal erosion or mucosal breaks.

Considerations backed by evidence

Unfortunately, symptoms alone do not always differentiate erosive versus nonerosive esophagitis, Dr. Wershil said, although recurrent vomiting, poor weight gain, anemia, feeding problems, and respiratory problems can be signs of complicated GERD.

He recommended the following five considerations to distinguish GERD from NERD:

- Is the patient exhibiting normal weight gain? If not, ask questions about how the child is being fed. Have the parents started diluting the formula because they think that will take care of the vomiting? Have they begun limiting the amount of formula after observing that the child throws up at 4 ounces but not at 2 ounces?

- Is the patient bleeding or anemic? Hematemesis is rarely the presentation of infants with GERD, but anemia may be.

- Does the patient have respiratory problems (for example, a history of aspiration, recurring wheezing, or cough)?

- Is the patient neurologically normal? If so, that can present a special class of patients in which vomiting may not be just normal infant vomiting.

- Is the patient older than 2 years? We expect 95% of children to outgrow reflux by 18 months, and most children who have physiological reflux will outgrow it by 2 years.

“Those five questions in 1983 had little evidence, but in 2017 there is more evidence that these are the questions to focus on,” Dr. Wershil said.

The role of diagnostic testing

Diagnostic testing, such as pH monitoring, impedance testing, and endoscopy, can be useful in specific situations but carry limitations for widespread use, Dr. Wershil said. “Each test has reasons and limitations.”

An upper GI tract series looks only for anatomic anomalies, for example. pH monitoring is still used in many centers, but in general, impedance monitoring has become more common because it can detect both acid and nonacid reflux: “You can get a very detailed analysis of events happening in the esophagus over time.” One caveat Dr. Wershil added is that, “in some instances, we’re unsure how to define this in the pediatric age ranges we treat.”

Endoscopy has a limited role for the rare patients with mucosal changes or erosive esophagitis, he added. Endoscopy is ordered to detect mucosal changes that confirm esophageal erosion. “In all the kids we scope with positive pH, we rarely find erosive esophagitis,” Dr. Wershil said. “What we find more often is NERD. That really represents more of what we see in our patient population.”

“I hope this information is a good starting point to understand the algorithms that get generated,” Dr. Wershil said.

He recommended an algorithm for gastroesophageal reflux prepared by the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (Pediatrics. 2013 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0421). “I think this information is really solidly grounded in evidence.”

Dr. Wershil is a consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals; is a member of the speakers bureau for Abbott Nutrition, Mead Johnson Nutrition, and Nutricia; and receives funding from the National Institutes of Health Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers.

CHICAGO – when doing a differential diagnosis. Fortunately, five questions backed by increasing evidence can help you make the call.

“Everyone in the room knows babies puke, and babies can puke a lot,” Barry K. Wershil, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. The approach to diagnosing GERD is age specific. “Kids who puke tend to outgrow it over time. With development, 95% or more are no longer refluxing at 18 months of age.”

“So generally there is no reason to initially refer older children and teenagers to a gastroenterologist,” Dr. Wershil said. “One of the essential things [you] do is consider all the causes of vomiting that are not GERD. If your first go-to is GERD, you’re going to miss other issues.”

Dr. Wershil reviewed the definitions: Gastroesophageal reflux is passage of gastric contents into the esophagus. GERD, on the other hand, is defined by the troublesome symptoms or complications associated with reflux of gastric material into the esophagus. In contrast, NERD is the presence of reflux symptoms with no evidence of mucosal erosion or mucosal breaks.

Considerations backed by evidence

Unfortunately, symptoms alone do not always differentiate erosive versus nonerosive esophagitis, Dr. Wershil said, although recurrent vomiting, poor weight gain, anemia, feeding problems, and respiratory problems can be signs of complicated GERD.

He recommended the following five considerations to distinguish GERD from NERD:

- Is the patient exhibiting normal weight gain? If not, ask questions about how the child is being fed. Have the parents started diluting the formula because they think that will take care of the vomiting? Have they begun limiting the amount of formula after observing that the child throws up at 4 ounces but not at 2 ounces?

- Is the patient bleeding or anemic? Hematemesis is rarely the presentation of infants with GERD, but anemia may be.

- Does the patient have respiratory problems (for example, a history of aspiration, recurring wheezing, or cough)?

- Is the patient neurologically normal? If so, that can present a special class of patients in which vomiting may not be just normal infant vomiting.

- Is the patient older than 2 years? We expect 95% of children to outgrow reflux by 18 months, and most children who have physiological reflux will outgrow it by 2 years.

“Those five questions in 1983 had little evidence, but in 2017 there is more evidence that these are the questions to focus on,” Dr. Wershil said.

The role of diagnostic testing

Diagnostic testing, such as pH monitoring, impedance testing, and endoscopy, can be useful in specific situations but carry limitations for widespread use, Dr. Wershil said. “Each test has reasons and limitations.”

An upper GI tract series looks only for anatomic anomalies, for example. pH monitoring is still used in many centers, but in general, impedance monitoring has become more common because it can detect both acid and nonacid reflux: “You can get a very detailed analysis of events happening in the esophagus over time.” One caveat Dr. Wershil added is that, “in some instances, we’re unsure how to define this in the pediatric age ranges we treat.”

Endoscopy has a limited role for the rare patients with mucosal changes or erosive esophagitis, he added. Endoscopy is ordered to detect mucosal changes that confirm esophageal erosion. “In all the kids we scope with positive pH, we rarely find erosive esophagitis,” Dr. Wershil said. “What we find more often is NERD. That really represents more of what we see in our patient population.”

“I hope this information is a good starting point to understand the algorithms that get generated,” Dr. Wershil said.

He recommended an algorithm for gastroesophageal reflux prepared by the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (Pediatrics. 2013 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0421). “I think this information is really solidly grounded in evidence.”

Dr. Wershil is a consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals; is a member of the speakers bureau for Abbott Nutrition, Mead Johnson Nutrition, and Nutricia; and receives funding from the National Institutes of Health Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

Localized wheezing differs from asthmatic, viral wheezing

CHICAGO – , explained Erik Hysinger, MD, MS, of the division of pulmonary medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Localized wheezing is not consistent with asthmatic or viral wheezing, which is typically diffuse and polyphonic, Dr. Hysinger emphasized at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Localized wheezing is less common than diffuse wheezing and typically has a homophonous sound,” Dr. Hysinger said. It also usually arises from a central airway pathology. “High flow rates create loud amplitude sounds.”

Dr. Hysinger also covered management strategies for focal wheezing, starting with an initial trial of bronchodilators. Any wheezing resulting from a central airway problem, however, isn’t likely to respond to bronchodilators. Standard work-up for any of these causes is usually a chest x-ray, often paired with a bronchoscopy. Persistent wheezing likely needs a chest CT, and many of these conditions will require referral to a subspecialist.

Airway occlusion diagnoses

Four potential causes of an airway blockage are a foreign body, a bronchial cast, mucous plugs, or airway tumors.

A foreign body typically occurs with a cough, wheezing, stridor, and respiratory distress. It is most common in children under age 4 years, usually in those without a history of aspiration, yet providers initially misdiagnose more than 20% of patients with a foreign body. The foreign object – often coins, food, or batteries – frequently ends up in the right main bronchus and may go undetected up to a month, potentially leading to pneumonia, abscess, atelectasis, bronchiectasis, or airway erosion.

An endobronchial cast is rarer than a foreign body, but can be large enough to completely fill a lung with branching mucin, fibrin, and inflammatory cells. The wheezing sounds homophonous, with a barky or brassy cough accompanied by atelectasis. Dr. Hysinger recommended ordering chest x-ray, echocardiogram, and bronchoscopy. Although often idiopathic, these casts also can result from asthma or another disease: neutrophilic inflammation typically indicates a heart condition whereas asthma or influenza leads to eosinophilic inflammation.

Treatment should involve clearing the airway, followed by hypertonic saline, an inhaled tissue plasminogen activator, and a bronchoscopy for extraction.

Although distinct from endobronchial casts, a mucus plug also presents with wheezing, a cough, and atelectasis, and potentially respiratory distress or failure, and hypoxemia. Mucus plugs are diagnosed with a chest x-ray and flexible bronchoscopy, and then treated by removing the plug and clearing the airway, hypertonic saline, and mucolytics.

The rarest cause of an airway blockage is an airway tumor, often mistaken for asthma. Benign causes include papillomatosis, hemangioma, and hamartomas, while potentially malignant causes include a carcinoid, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, inflammatory myofibromas, and granular cell tumors.

In addition to a chest x-ray and bronchoscopy, a chest CT scan plus a biopsy and resection are necessary to diagnose airway tumors. Treatment will depend on the specific type of tumor identified.

“Overall survival is excellent,” Dr. Hysinger said of children with airway tumors.

Airway narrowing diagnoses

Two possible diagnoses for an intrinsic airway narrowing include bronchomalacia, occurring in only 1 of 2,100 children, and bronchial stenosis.

In bronchomalacia – diagnosed primarily with bronchoscopy – the airway collapses from weakening of the cartilage and posterior membrane. Bronchomalacia sounds like homophonous wheezing with a barky or brassy cough, and it’s frequently accompanied by recurrent bronchitis and/or pneumonia. Intervention is rarely necessary when occurring on its own, but severe cases may require endobronchial stents. Dr. Hysinger also recommended considering ipratroprium instead of albuterol.

Bronchial stenosis involves a fixed narrowing of the bronchi and can be congenital – typically occurring with heart disease – or acquired after an intubation and suction trauma or bronchiolitis obliterans (“popcorn lung”). A chest x-ray and bronchoscopy again are standard, but MRI may be necessary as well. Aside from helping the patient clear the airway, bronchial stenosis typically needs limited management unless the patient is symptomatic. In that case, options include balloon dilation, endobronchial stents, or a slide bronchoplasty.

Airway compression diagnoses

An extrinsic airway compression could have a vascular cause or could result from pressure by an extrinsic mass or the axial skeleton.

Vascular compression usually occurs due to abnormal vasculature development, particularly with vascular stents, Dr. Hysinger said. The wheezing presents with stridor, feeding intolerance, recurrent infections, and cyanotic episodes. The work-up should include a chest x-ray, bronchoscopy, and a chest CT and/or MRI. A variety of interventions may be necessary to treat it, including an aortopexy, pulmonary artery trunk–pexy, arterioplasty, vessel implantation, or endobronchial stent. Residual malacia may remain after treatment, however.

The most common reasons for airway compression by some kind of mass is a reactive lymphadenopathy, a tumor, or an infection, including tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. Severe narrowing of the airway can lead to respiratory failure, but because the compression can develop slowly, the wheezing can be mistaken for asthma. In addition to a chest CT and bronchoscopy, a patient will need other work-ups depending on the cause. Possibilities include a biopsy, a gastric aspirate (for tuberculosis), a bronchoalveolar lavage, or antibody titers.

Similarly, because therapeutic intervention requires treating the underlying infection, specific treatments will vary. Tumors typically will need resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation – and, until the airway is fully cleared, the patient may need chronic mechanical ventilation.

Children with severe scoliosis or kyphosis are those most likely to experience airway compression resulting from pressure by the axial skeleton, in which the spine’s curvature directly presses on the airway. In addition to the wheeze, these patients may have respiratory distress or recurrent focal pneumonia, Dr. Hysinger said. The standard work-up involves a chest x-ray, chest CT, spinal MRI, and bronchoscopy.

Consider using spinal rods, but they can both help the condition or potentially exacerbate the compression, Dr. Hysinger said. Either way, children also will need help with airway clearance and coughing.

Dr. Hysinger concluded by reviewing what you may consider changing in your current practice, including the initial trial of bronchodilators, a chest x-ray, and a subspecialist referral.

No funding was used for this presentation, and Dr. Hysinger reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – , explained Erik Hysinger, MD, MS, of the division of pulmonary medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Localized wheezing is not consistent with asthmatic or viral wheezing, which is typically diffuse and polyphonic, Dr. Hysinger emphasized at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Localized wheezing is less common than diffuse wheezing and typically has a homophonous sound,” Dr. Hysinger said. It also usually arises from a central airway pathology. “High flow rates create loud amplitude sounds.”

Dr. Hysinger also covered management strategies for focal wheezing, starting with an initial trial of bronchodilators. Any wheezing resulting from a central airway problem, however, isn’t likely to respond to bronchodilators. Standard work-up for any of these causes is usually a chest x-ray, often paired with a bronchoscopy. Persistent wheezing likely needs a chest CT, and many of these conditions will require referral to a subspecialist.

Airway occlusion diagnoses

Four potential causes of an airway blockage are a foreign body, a bronchial cast, mucous plugs, or airway tumors.

A foreign body typically occurs with a cough, wheezing, stridor, and respiratory distress. It is most common in children under age 4 years, usually in those without a history of aspiration, yet providers initially misdiagnose more than 20% of patients with a foreign body. The foreign object – often coins, food, or batteries – frequently ends up in the right main bronchus and may go undetected up to a month, potentially leading to pneumonia, abscess, atelectasis, bronchiectasis, or airway erosion.

An endobronchial cast is rarer than a foreign body, but can be large enough to completely fill a lung with branching mucin, fibrin, and inflammatory cells. The wheezing sounds homophonous, with a barky or brassy cough accompanied by atelectasis. Dr. Hysinger recommended ordering chest x-ray, echocardiogram, and bronchoscopy. Although often idiopathic, these casts also can result from asthma or another disease: neutrophilic inflammation typically indicates a heart condition whereas asthma or influenza leads to eosinophilic inflammation.

Treatment should involve clearing the airway, followed by hypertonic saline, an inhaled tissue plasminogen activator, and a bronchoscopy for extraction.

Although distinct from endobronchial casts, a mucus plug also presents with wheezing, a cough, and atelectasis, and potentially respiratory distress or failure, and hypoxemia. Mucus plugs are diagnosed with a chest x-ray and flexible bronchoscopy, and then treated by removing the plug and clearing the airway, hypertonic saline, and mucolytics.

The rarest cause of an airway blockage is an airway tumor, often mistaken for asthma. Benign causes include papillomatosis, hemangioma, and hamartomas, while potentially malignant causes include a carcinoid, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, inflammatory myofibromas, and granular cell tumors.

In addition to a chest x-ray and bronchoscopy, a chest CT scan plus a biopsy and resection are necessary to diagnose airway tumors. Treatment will depend on the specific type of tumor identified.

“Overall survival is excellent,” Dr. Hysinger said of children with airway tumors.

Airway narrowing diagnoses

Two possible diagnoses for an intrinsic airway narrowing include bronchomalacia, occurring in only 1 of 2,100 children, and bronchial stenosis.

In bronchomalacia – diagnosed primarily with bronchoscopy – the airway collapses from weakening of the cartilage and posterior membrane. Bronchomalacia sounds like homophonous wheezing with a barky or brassy cough, and it’s frequently accompanied by recurrent bronchitis and/or pneumonia. Intervention is rarely necessary when occurring on its own, but severe cases may require endobronchial stents. Dr. Hysinger also recommended considering ipratroprium instead of albuterol.

Bronchial stenosis involves a fixed narrowing of the bronchi and can be congenital – typically occurring with heart disease – or acquired after an intubation and suction trauma or bronchiolitis obliterans (“popcorn lung”). A chest x-ray and bronchoscopy again are standard, but MRI may be necessary as well. Aside from helping the patient clear the airway, bronchial stenosis typically needs limited management unless the patient is symptomatic. In that case, options include balloon dilation, endobronchial stents, or a slide bronchoplasty.

Airway compression diagnoses

An extrinsic airway compression could have a vascular cause or could result from pressure by an extrinsic mass or the axial skeleton.

Vascular compression usually occurs due to abnormal vasculature development, particularly with vascular stents, Dr. Hysinger said. The wheezing presents with stridor, feeding intolerance, recurrent infections, and cyanotic episodes. The work-up should include a chest x-ray, bronchoscopy, and a chest CT and/or MRI. A variety of interventions may be necessary to treat it, including an aortopexy, pulmonary artery trunk–pexy, arterioplasty, vessel implantation, or endobronchial stent. Residual malacia may remain after treatment, however.

The most common reasons for airway compression by some kind of mass is a reactive lymphadenopathy, a tumor, or an infection, including tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. Severe narrowing of the airway can lead to respiratory failure, but because the compression can develop slowly, the wheezing can be mistaken for asthma. In addition to a chest CT and bronchoscopy, a patient will need other work-ups depending on the cause. Possibilities include a biopsy, a gastric aspirate (for tuberculosis), a bronchoalveolar lavage, or antibody titers.

Similarly, because therapeutic intervention requires treating the underlying infection, specific treatments will vary. Tumors typically will need resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation – and, until the airway is fully cleared, the patient may need chronic mechanical ventilation.

Children with severe scoliosis or kyphosis are those most likely to experience airway compression resulting from pressure by the axial skeleton, in which the spine’s curvature directly presses on the airway. In addition to the wheeze, these patients may have respiratory distress or recurrent focal pneumonia, Dr. Hysinger said. The standard work-up involves a chest x-ray, chest CT, spinal MRI, and bronchoscopy.

Consider using spinal rods, but they can both help the condition or potentially exacerbate the compression, Dr. Hysinger said. Either way, children also will need help with airway clearance and coughing.

Dr. Hysinger concluded by reviewing what you may consider changing in your current practice, including the initial trial of bronchodilators, a chest x-ray, and a subspecialist referral.

No funding was used for this presentation, and Dr. Hysinger reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – , explained Erik Hysinger, MD, MS, of the division of pulmonary medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Localized wheezing is not consistent with asthmatic or viral wheezing, which is typically diffuse and polyphonic, Dr. Hysinger emphasized at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Localized wheezing is less common than diffuse wheezing and typically has a homophonous sound,” Dr. Hysinger said. It also usually arises from a central airway pathology. “High flow rates create loud amplitude sounds.”

Dr. Hysinger also covered management strategies for focal wheezing, starting with an initial trial of bronchodilators. Any wheezing resulting from a central airway problem, however, isn’t likely to respond to bronchodilators. Standard work-up for any of these causes is usually a chest x-ray, often paired with a bronchoscopy. Persistent wheezing likely needs a chest CT, and many of these conditions will require referral to a subspecialist.

Airway occlusion diagnoses

Four potential causes of an airway blockage are a foreign body, a bronchial cast, mucous plugs, or airway tumors.

A foreign body typically occurs with a cough, wheezing, stridor, and respiratory distress. It is most common in children under age 4 years, usually in those without a history of aspiration, yet providers initially misdiagnose more than 20% of patients with a foreign body. The foreign object – often coins, food, or batteries – frequently ends up in the right main bronchus and may go undetected up to a month, potentially leading to pneumonia, abscess, atelectasis, bronchiectasis, or airway erosion.

An endobronchial cast is rarer than a foreign body, but can be large enough to completely fill a lung with branching mucin, fibrin, and inflammatory cells. The wheezing sounds homophonous, with a barky or brassy cough accompanied by atelectasis. Dr. Hysinger recommended ordering chest x-ray, echocardiogram, and bronchoscopy. Although often idiopathic, these casts also can result from asthma or another disease: neutrophilic inflammation typically indicates a heart condition whereas asthma or influenza leads to eosinophilic inflammation.

Treatment should involve clearing the airway, followed by hypertonic saline, an inhaled tissue plasminogen activator, and a bronchoscopy for extraction.

Although distinct from endobronchial casts, a mucus plug also presents with wheezing, a cough, and atelectasis, and potentially respiratory distress or failure, and hypoxemia. Mucus plugs are diagnosed with a chest x-ray and flexible bronchoscopy, and then treated by removing the plug and clearing the airway, hypertonic saline, and mucolytics.

The rarest cause of an airway blockage is an airway tumor, often mistaken for asthma. Benign causes include papillomatosis, hemangioma, and hamartomas, while potentially malignant causes include a carcinoid, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, inflammatory myofibromas, and granular cell tumors.

In addition to a chest x-ray and bronchoscopy, a chest CT scan plus a biopsy and resection are necessary to diagnose airway tumors. Treatment will depend on the specific type of tumor identified.

“Overall survival is excellent,” Dr. Hysinger said of children with airway tumors.

Airway narrowing diagnoses

Two possible diagnoses for an intrinsic airway narrowing include bronchomalacia, occurring in only 1 of 2,100 children, and bronchial stenosis.

In bronchomalacia – diagnosed primarily with bronchoscopy – the airway collapses from weakening of the cartilage and posterior membrane. Bronchomalacia sounds like homophonous wheezing with a barky or brassy cough, and it’s frequently accompanied by recurrent bronchitis and/or pneumonia. Intervention is rarely necessary when occurring on its own, but severe cases may require endobronchial stents. Dr. Hysinger also recommended considering ipratroprium instead of albuterol.

Bronchial stenosis involves a fixed narrowing of the bronchi and can be congenital – typically occurring with heart disease – or acquired after an intubation and suction trauma or bronchiolitis obliterans (“popcorn lung”). A chest x-ray and bronchoscopy again are standard, but MRI may be necessary as well. Aside from helping the patient clear the airway, bronchial stenosis typically needs limited management unless the patient is symptomatic. In that case, options include balloon dilation, endobronchial stents, or a slide bronchoplasty.

Airway compression diagnoses

An extrinsic airway compression could have a vascular cause or could result from pressure by an extrinsic mass or the axial skeleton.

Vascular compression usually occurs due to abnormal vasculature development, particularly with vascular stents, Dr. Hysinger said. The wheezing presents with stridor, feeding intolerance, recurrent infections, and cyanotic episodes. The work-up should include a chest x-ray, bronchoscopy, and a chest CT and/or MRI. A variety of interventions may be necessary to treat it, including an aortopexy, pulmonary artery trunk–pexy, arterioplasty, vessel implantation, or endobronchial stent. Residual malacia may remain after treatment, however.

The most common reasons for airway compression by some kind of mass is a reactive lymphadenopathy, a tumor, or an infection, including tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. Severe narrowing of the airway can lead to respiratory failure, but because the compression can develop slowly, the wheezing can be mistaken for asthma. In addition to a chest CT and bronchoscopy, a patient will need other work-ups depending on the cause. Possibilities include a biopsy, a gastric aspirate (for tuberculosis), a bronchoalveolar lavage, or antibody titers.

Similarly, because therapeutic intervention requires treating the underlying infection, specific treatments will vary. Tumors typically will need resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation – and, until the airway is fully cleared, the patient may need chronic mechanical ventilation.

Children with severe scoliosis or kyphosis are those most likely to experience airway compression resulting from pressure by the axial skeleton, in which the spine’s curvature directly presses on the airway. In addition to the wheeze, these patients may have respiratory distress or recurrent focal pneumonia, Dr. Hysinger said. The standard work-up involves a chest x-ray, chest CT, spinal MRI, and bronchoscopy.

Consider using spinal rods, but they can both help the condition or potentially exacerbate the compression, Dr. Hysinger said. Either way, children also will need help with airway clearance and coughing.

Dr. Hysinger concluded by reviewing what you may consider changing in your current practice, including the initial trial of bronchodilators, a chest x-ray, and a subspecialist referral.

No funding was used for this presentation, and Dr. Hysinger reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

Sorting out syncope signs and symptoms in kids remains essential

CHICAGO – Syncope often is misdiagnosed in pediatric patients complaining of chest pain, and a new guideline released in 2017 could guide clinicians toward a more accurate differential diagnosis and help them know when immediate referral to cardiology or the emergency department is warranted.

“There are recent guidelines published this year which are helpful,” said Dr. Barbara Deal, the Getz Professor of Cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago. “,” which is defined as transient loss of consciousness.

“Once you establish it is a simple vasovagal [cause], you need to educate patients on conditions that would promote this and the need to be anticipatory,” Dr. Deal said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Further testing with an echo[cardiogram] should be done if you suspect heart disease or a rhythm disorder.”

Chest pain and syncope are common complaints that can lead to significant anxiety for patients, parents, and pediatric providers. The greatest cause of this anxiety is the prospect of a fatal or near-fatal event. An abnormal cardiac examination, any associated palpitations, and a history of urinary incontinence or traumatic injury are reasons to worry, she said. “Any of these should prompt an urgent consult to cardiology or the emergency department.”

Cardiac causes of chest pain include reflex or vasovagal syncope or even a more serious cardiac cause, such as arrhythmic or structural issues, Dr. Deal said. Symptoms that appear with exertion or stress also are very worrisome. “You would know if they have a heart murmur or stenosis – it’s these other things that don’t present with a cardiac abnormality: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy,” she said. “If they have symptoms on exertion, pay attention. This is not good.”

Syncope often is misdiagnosed, Dr. Deal said. Approximately 35%-48% of patients classified as having syncope do not have actual syncope;rather they experience dizziness rather than a loss of consciousness. In a study of 194 children, for example, the leading etiologies diagnosed after evaluation for syncope included simple fainting in 49%, a vasopressor/vasovagal response in 14%, and possible seizure in 14% (J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29[6]:1039-45). Seven percent were diagnosed with syncope not otherwise specified in this series. Some other causes included psychogenic or orthostatic ones, hyperventilation, dysmenorrhea, vertigo, dehydration, trauma, stress, exhaustion, or an infectious condition.*

“When should you be thinking life-threatening syncope?” Dr. Deal asked. Arrhythmic disorders that are heritable, such as an ion channelopathy, are an example. “They don’t always feel the racing heartbeat, but they feel something is not right; they feel a sense of impending doom. Some families report signs during exercise like swimming, seizures, gargling noises, or unusual symptoms on awakening.”

Dr. Deal noted that ages 3-24 years are “the problem territory for cardiac arrest.” In this age group, 43%-55% of cardiac arrests are associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias; about one in three will have prior syncope. “These causes are not detectable on physical examination and often are not detectable with ECG only,” adding to the differential diagnosis challenges.*

Refer to a pediatric cardiologist

For this reason and others, referral to a pediatric cardiologist is indicated instead of a consult with an adult cardiologist, Dr. Deal said. “You know how your kids will start with ‘no offense.’ Like, ‘no offense, Mom, but your hair looks awful.’ With moderate offense intended, having an adult cardiologist read a pediatric ECG and clear them is not adequate. They will be looking for ischemia or A-fib [atrial fibrillation]; they’re not looking for long QT syndrome, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, or abnormal T waves.”

Early detection of long QT syndrome is optimal, Dr. Deal said, because symptom onset often is between infancy and age 7 years. In addition, mortality is highest in the first 2 decades of life. “I think this could be why adult cardiologists are not as concerned as we are,” Dr. Deal said. “The bad ones die before they reach adulthood.”

Ruling out a cardiac cause

The 2017 joint guideline defined syncope as a transient loss of consciousness. “By definition, you pass out, you’re not aware of where you are, and you cannot hear,” Dr. Deal said. If a patient reports they could hear people talking, they may have lost postural tone, but they did not have syncope, she added.

“Sometimes, we see teenagers who are said to pass out and are unresponsive for 5 minutes, 10 minutes, or 20 minutes. I’m usually relieved to hear that because that gets cardiac off the hook,” Dr. Deal said. “There is nothing cardiac that makes you pass out for 20 minutes, unless people are resuscitating you.” She added, “I’m not suggesting it’s not a significant problem that you need to get to the bottom of.”

Noncardiac etiologies can be neurologic, metabolic, drug-induced, or psychogenic. “This is where the detective work comes in.”

Keep clinical suspicion high for psychogenic syncope, Dr. Deal said. Psychogenic episodes stem from significant psychological stress, often something so profoundly bothersome that they cannot cope, such as sexual abuse.

A helpful tip for diagnosing the less worrisome vasovagal syncope is asking whether a patient was sitting to standing or standing a long time before an episode, Dr. Deal said. “A common complaint is that the family went to airport, got up early, didn’t eat, and ended up standing for a long time. Kids will say they don’t feel well, they fall down, and all hell breaks loose.” Other causes of vasovagal syncope include stress, pain, or a situational trigger, for example, when a person faints during a blood draw or immunization.

The 2017 guideline also set forth the evidence behind various medications used to lower the risk of syncope. However, Dr. Deal said, “If syncope only happens every 3 years when you go to an airport, it’s probably not worth daily therapy to prevent that.”

‘The world’s most boring test’

For the most part, lifestyle measures should work to address vasovagal syncope. A tilt table test can be useful to aid the differential diagnosis, but it’s recommended only when the etiology is unclear, Dr. Deal said. On the plus side, the tilt table test allows clinicians to reproduce symptoms in a controlled environment. On the downside, she added, “It’s the world’s most boring test. It’s a challenge for the cardiologist to stay awake. It’s very boring, until all hell breaks loose.”

“I find this helpful in the setting of kids with seizures and for kids with this atypical syncope where you just cannot convince the family that these 20-minute episodes of loss of consciousness are not near-death episodes.”

Dr. Deal had no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 10/25/2017.

CHICAGO – Syncope often is misdiagnosed in pediatric patients complaining of chest pain, and a new guideline released in 2017 could guide clinicians toward a more accurate differential diagnosis and help them know when immediate referral to cardiology or the emergency department is warranted.

“There are recent guidelines published this year which are helpful,” said Dr. Barbara Deal, the Getz Professor of Cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago. “,” which is defined as transient loss of consciousness.

“Once you establish it is a simple vasovagal [cause], you need to educate patients on conditions that would promote this and the need to be anticipatory,” Dr. Deal said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Further testing with an echo[cardiogram] should be done if you suspect heart disease or a rhythm disorder.”

Chest pain and syncope are common complaints that can lead to significant anxiety for patients, parents, and pediatric providers. The greatest cause of this anxiety is the prospect of a fatal or near-fatal event. An abnormal cardiac examination, any associated palpitations, and a history of urinary incontinence or traumatic injury are reasons to worry, she said. “Any of these should prompt an urgent consult to cardiology or the emergency department.”

Cardiac causes of chest pain include reflex or vasovagal syncope or even a more serious cardiac cause, such as arrhythmic or structural issues, Dr. Deal said. Symptoms that appear with exertion or stress also are very worrisome. “You would know if they have a heart murmur or stenosis – it’s these other things that don’t present with a cardiac abnormality: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy,” she said. “If they have symptoms on exertion, pay attention. This is not good.”

Syncope often is misdiagnosed, Dr. Deal said. Approximately 35%-48% of patients classified as having syncope do not have actual syncope;rather they experience dizziness rather than a loss of consciousness. In a study of 194 children, for example, the leading etiologies diagnosed after evaluation for syncope included simple fainting in 49%, a vasopressor/vasovagal response in 14%, and possible seizure in 14% (J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29[6]:1039-45). Seven percent were diagnosed with syncope not otherwise specified in this series. Some other causes included psychogenic or orthostatic ones, hyperventilation, dysmenorrhea, vertigo, dehydration, trauma, stress, exhaustion, or an infectious condition.*

“When should you be thinking life-threatening syncope?” Dr. Deal asked. Arrhythmic disorders that are heritable, such as an ion channelopathy, are an example. “They don’t always feel the racing heartbeat, but they feel something is not right; they feel a sense of impending doom. Some families report signs during exercise like swimming, seizures, gargling noises, or unusual symptoms on awakening.”

Dr. Deal noted that ages 3-24 years are “the problem territory for cardiac arrest.” In this age group, 43%-55% of cardiac arrests are associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias; about one in three will have prior syncope. “These causes are not detectable on physical examination and often are not detectable with ECG only,” adding to the differential diagnosis challenges.*

Refer to a pediatric cardiologist

For this reason and others, referral to a pediatric cardiologist is indicated instead of a consult with an adult cardiologist, Dr. Deal said. “You know how your kids will start with ‘no offense.’ Like, ‘no offense, Mom, but your hair looks awful.’ With moderate offense intended, having an adult cardiologist read a pediatric ECG and clear them is not adequate. They will be looking for ischemia or A-fib [atrial fibrillation]; they’re not looking for long QT syndrome, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, or abnormal T waves.”

Early detection of long QT syndrome is optimal, Dr. Deal said, because symptom onset often is between infancy and age 7 years. In addition, mortality is highest in the first 2 decades of life. “I think this could be why adult cardiologists are not as concerned as we are,” Dr. Deal said. “The bad ones die before they reach adulthood.”

Ruling out a cardiac cause

The 2017 joint guideline defined syncope as a transient loss of consciousness. “By definition, you pass out, you’re not aware of where you are, and you cannot hear,” Dr. Deal said. If a patient reports they could hear people talking, they may have lost postural tone, but they did not have syncope, she added.

“Sometimes, we see teenagers who are said to pass out and are unresponsive for 5 minutes, 10 minutes, or 20 minutes. I’m usually relieved to hear that because that gets cardiac off the hook,” Dr. Deal said. “There is nothing cardiac that makes you pass out for 20 minutes, unless people are resuscitating you.” She added, “I’m not suggesting it’s not a significant problem that you need to get to the bottom of.”

Noncardiac etiologies can be neurologic, metabolic, drug-induced, or psychogenic. “This is where the detective work comes in.”

Keep clinical suspicion high for psychogenic syncope, Dr. Deal said. Psychogenic episodes stem from significant psychological stress, often something so profoundly bothersome that they cannot cope, such as sexual abuse.

A helpful tip for diagnosing the less worrisome vasovagal syncope is asking whether a patient was sitting to standing or standing a long time before an episode, Dr. Deal said. “A common complaint is that the family went to airport, got up early, didn’t eat, and ended up standing for a long time. Kids will say they don’t feel well, they fall down, and all hell breaks loose.” Other causes of vasovagal syncope include stress, pain, or a situational trigger, for example, when a person faints during a blood draw or immunization.

The 2017 guideline also set forth the evidence behind various medications used to lower the risk of syncope. However, Dr. Deal said, “If syncope only happens every 3 years when you go to an airport, it’s probably not worth daily therapy to prevent that.”

‘The world’s most boring test’

For the most part, lifestyle measures should work to address vasovagal syncope. A tilt table test can be useful to aid the differential diagnosis, but it’s recommended only when the etiology is unclear, Dr. Deal said. On the plus side, the tilt table test allows clinicians to reproduce symptoms in a controlled environment. On the downside, she added, “It’s the world’s most boring test. It’s a challenge for the cardiologist to stay awake. It’s very boring, until all hell breaks loose.”

“I find this helpful in the setting of kids with seizures and for kids with this atypical syncope where you just cannot convince the family that these 20-minute episodes of loss of consciousness are not near-death episodes.”

Dr. Deal had no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 10/25/2017.

CHICAGO – Syncope often is misdiagnosed in pediatric patients complaining of chest pain, and a new guideline released in 2017 could guide clinicians toward a more accurate differential diagnosis and help them know when immediate referral to cardiology or the emergency department is warranted.

“There are recent guidelines published this year which are helpful,” said Dr. Barbara Deal, the Getz Professor of Cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago. “,” which is defined as transient loss of consciousness.

“Once you establish it is a simple vasovagal [cause], you need to educate patients on conditions that would promote this and the need to be anticipatory,” Dr. Deal said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Further testing with an echo[cardiogram] should be done if you suspect heart disease or a rhythm disorder.”

Chest pain and syncope are common complaints that can lead to significant anxiety for patients, parents, and pediatric providers. The greatest cause of this anxiety is the prospect of a fatal or near-fatal event. An abnormal cardiac examination, any associated palpitations, and a history of urinary incontinence or traumatic injury are reasons to worry, she said. “Any of these should prompt an urgent consult to cardiology or the emergency department.”

Cardiac causes of chest pain include reflex or vasovagal syncope or even a more serious cardiac cause, such as arrhythmic or structural issues, Dr. Deal said. Symptoms that appear with exertion or stress also are very worrisome. “You would know if they have a heart murmur or stenosis – it’s these other things that don’t present with a cardiac abnormality: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy,” she said. “If they have symptoms on exertion, pay attention. This is not good.”

Syncope often is misdiagnosed, Dr. Deal said. Approximately 35%-48% of patients classified as having syncope do not have actual syncope;rather they experience dizziness rather than a loss of consciousness. In a study of 194 children, for example, the leading etiologies diagnosed after evaluation for syncope included simple fainting in 49%, a vasopressor/vasovagal response in 14%, and possible seizure in 14% (J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29[6]:1039-45). Seven percent were diagnosed with syncope not otherwise specified in this series. Some other causes included psychogenic or orthostatic ones, hyperventilation, dysmenorrhea, vertigo, dehydration, trauma, stress, exhaustion, or an infectious condition.*

“When should you be thinking life-threatening syncope?” Dr. Deal asked. Arrhythmic disorders that are heritable, such as an ion channelopathy, are an example. “They don’t always feel the racing heartbeat, but they feel something is not right; they feel a sense of impending doom. Some families report signs during exercise like swimming, seizures, gargling noises, or unusual symptoms on awakening.”

Dr. Deal noted that ages 3-24 years are “the problem territory for cardiac arrest.” In this age group, 43%-55% of cardiac arrests are associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias; about one in three will have prior syncope. “These causes are not detectable on physical examination and often are not detectable with ECG only,” adding to the differential diagnosis challenges.*

Refer to a pediatric cardiologist

For this reason and others, referral to a pediatric cardiologist is indicated instead of a consult with an adult cardiologist, Dr. Deal said. “You know how your kids will start with ‘no offense.’ Like, ‘no offense, Mom, but your hair looks awful.’ With moderate offense intended, having an adult cardiologist read a pediatric ECG and clear them is not adequate. They will be looking for ischemia or A-fib [atrial fibrillation]; they’re not looking for long QT syndrome, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, or abnormal T waves.”

Early detection of long QT syndrome is optimal, Dr. Deal said, because symptom onset often is between infancy and age 7 years. In addition, mortality is highest in the first 2 decades of life. “I think this could be why adult cardiologists are not as concerned as we are,” Dr. Deal said. “The bad ones die before they reach adulthood.”

Ruling out a cardiac cause

The 2017 joint guideline defined syncope as a transient loss of consciousness. “By definition, you pass out, you’re not aware of where you are, and you cannot hear,” Dr. Deal said. If a patient reports they could hear people talking, they may have lost postural tone, but they did not have syncope, she added.

“Sometimes, we see teenagers who are said to pass out and are unresponsive for 5 minutes, 10 minutes, or 20 minutes. I’m usually relieved to hear that because that gets cardiac off the hook,” Dr. Deal said. “There is nothing cardiac that makes you pass out for 20 minutes, unless people are resuscitating you.” She added, “I’m not suggesting it’s not a significant problem that you need to get to the bottom of.”

Noncardiac etiologies can be neurologic, metabolic, drug-induced, or psychogenic. “This is where the detective work comes in.”

Keep clinical suspicion high for psychogenic syncope, Dr. Deal said. Psychogenic episodes stem from significant psychological stress, often something so profoundly bothersome that they cannot cope, such as sexual abuse.

A helpful tip for diagnosing the less worrisome vasovagal syncope is asking whether a patient was sitting to standing or standing a long time before an episode, Dr. Deal said. “A common complaint is that the family went to airport, got up early, didn’t eat, and ended up standing for a long time. Kids will say they don’t feel well, they fall down, and all hell breaks loose.” Other causes of vasovagal syncope include stress, pain, or a situational trigger, for example, when a person faints during a blood draw or immunization.

The 2017 guideline also set forth the evidence behind various medications used to lower the risk of syncope. However, Dr. Deal said, “If syncope only happens every 3 years when you go to an airport, it’s probably not worth daily therapy to prevent that.”

‘The world’s most boring test’

For the most part, lifestyle measures should work to address vasovagal syncope. A tilt table test can be useful to aid the differential diagnosis, but it’s recommended only when the etiology is unclear, Dr. Deal said. On the plus side, the tilt table test allows clinicians to reproduce symptoms in a controlled environment. On the downside, she added, “It’s the world’s most boring test. It’s a challenge for the cardiologist to stay awake. It’s very boring, until all hell breaks loose.”

“I find this helpful in the setting of kids with seizures and for kids with this atypical syncope where you just cannot convince the family that these 20-minute episodes of loss of consciousness are not near-death episodes.”

Dr. Deal had no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 10/25/2017.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

Evidence is mixed on probiotics in pediatric patients

CHICAGO – Outside of that, things are less clear.

“In terms of diarrhea, the evidence is positive, but probiotics only provide about 25 hours of benefit. And treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea is really dependent on patient adherence,” said Michael D. Cabana, MD. When it comes to treating colic, there is a particular probiotic that looks promising, he added, but the research so far demonstrating effectiveness is limited to breastfed babies. Also, the probiotic therapy appears to work best when started relatively early.

You are very likely to be asked your take on probiotics for a wide range of conditions, Dr. Cabana said, Overall, however, skepticism is warranted. Advise patients and families to be aware of advertising that promotes many different products as “probiotic,” especially around claims of improved “gut health” or “balanced microbiota.” He emphasized: “Make sure what your patients are using has some evidence behind it.”

Knowing the particular probiotic strain is essential to researching the evidence around its use, said Dr. Cabana, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco. “I used the Canis familiaris example. All dogs are C. familiaris. But there are different breeds. You want to make sure you match the right breed to the task. If you were in an avalanche in the Swiss Alps, you would want a St. Bernard to rescue you, not a Chihuahua,” he said. “Similarly, when you are using probiotics you want to make sure you have the right strain, not just the genus and species.” For example, if a product label states it contains Bifidobacterium breve C50, the “C50” is the strain.

Another tip is to look for labeling that lists probiotic concentrations in colony-forming units or CFUs, Dr. Cabana said. He’s seen concentrations listed in mg, a red flag that a product is not legitimate.

Families also might ask if it’s better to take a probiotic supplement or choose food that contains probiotics. “Food products offer additional nutritional benefits, but you can give a relatively higher dose with supplements with a much lower volume ingested,” Dr. Cabana said. “And supplements theoretically provide a more consistent dose.” Speaking of dose, it’s difficult to counsel patients on dosing and frequency in general because probiotics really vary by the indication and formulation.

“As a pediatrician, I also get this question: Should kids get a lower dose of probiotic?” Dr. Cabana said. There are no known reports of toxicity associated with probiotic use in either adults or children, he said. “Unless a dose modification has been documented in a clinical trial, it is not clear that this is necessary. You’re just giving less of the probiotic.”

Treating diarrhea and antibiotic-associated diarrhea

When it comes to probiotics for treating acute diarrhea in children, “the literature is actually fairly good here,” Dr. Cabana said. More than 60 studies with an excess of 8,000 participants, the majority with rotavirus infection, suggests probiotics are not associated with any adverse effects and generally shorten duration of diarrhea.

In fact, Dr. Cabana added, multiple meta-analyses support a shorter course of diarrhea. He added, “Look at the units here – it’s hours, not days. You can treat, but on average it’s only 25 hours.” He added that a day less of diarrhea can be significant for patients and parents, however.

In another meta-analysis probiotics, particularly Lactobacillus strains, were analyzed for prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (JAMA. 2012 May 9;307[18]:1959-69). Researchers assessed 63 randomized controlled trials with nearly 12,000 participants. The pooled results showed a statistically significant positive reduction in antibiotic-associated diarrhea (relative risk, 0.58; P less than .001). “Note the number needed to treat to see the effect is 13, so it won’t work in every patient,” Dr. Cabana said.

“So prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea is well documented. However, it’s also highly dependent on patent adherence,” he emphasized.

The clinical evidence on colic

For treating babies with colic, the best evidence is behind use of Lactobacilus reuteri DSM 17938, Dr. Cabana said. It tends to work best in breastfed infants, babies not on any gastrointestinal meds, and babies that start therapy early in the course of symptoms. “Use in formula-fed infants is unknown, because there are not enough data so far,” he said.

In some cases, during a prenatal visit, soon-to-be-parents will ask if they should start a probiotic to prevent colic. Dr. Cabana has seen only one prophylaxis study for this indication (JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Mar;168[3]:228-33). In the study, 589 infants were randomly allocated to take L. reuteri DSM 17938 or placebo daily for 90 days. At 3 months of age, the researchers discovered a significantly shorter mean duration of daily crying in the probiotic group (38 vs. 71 minutes; P less than .01).

What’s known about efficacy for eczema

The evidence for treating a child who presents with eczema with probiotics does not support efficacy in general, Dr. Cabana said. And the evidence on prevention of atopic eczema is mixed.

For example, in a randomized, controlled study from Finland, investigators randomized mothers to receive Lactobacillus GG or placebo during the prenatal period (Lancet. 2001;357:1076-9). Of 132 of the children, 35% were later diagnosed with atopic eczema, and the rate in the probiotic group, 23%, was half the 46% rate in the placebo group.

In contrast, researchers found no benefit regarding prevention of atopic dermatitis when 105 pregnant women were randomized to Lactobacillus GG or placebo. At the age of 2 years, atopic dermatitis was diagnosed in 28% of the 50 children in the probiotic group and 27.3% of the 44 in the placebo group (Pediatrics. 2008;121:e850-6).

The region of Germany where the study was conducted was rural/agricultural, so the diet could be different, Dr. Cabana said. Also, the median duration of breastfeeding differed between the Finnish and German study population, 6.8 months versus 9.2 months, respectively. “So that could potentially explain it, or there are just differences that cannot be explained.”

For more information, Dr. Cabana recommended information provided by the International Scientific Association of Prebiotics & Probiotics (https://isappscience.org/infographics/). The association’s website has easy to understand infographics including: What are probiotics and what can they do for you?; What’s so special about fermented foods?; and How do you read a probiotic label?

Dr. Cabana reported he receives research support from the National Institutes of Health, Wyeth Nutrition, and Nestle; is on the speakers bureau for Merck; owns stocks or bonds in Abbot and AbbVie; and is a consultant for Mead Johnson, Abbott, Genentech, Biogaia, General Mills, and Nestle.

CHICAGO – Outside of that, things are less clear.

“In terms of diarrhea, the evidence is positive, but probiotics only provide about 25 hours of benefit. And treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea is really dependent on patient adherence,” said Michael D. Cabana, MD. When it comes to treating colic, there is a particular probiotic that looks promising, he added, but the research so far demonstrating effectiveness is limited to breastfed babies. Also, the probiotic therapy appears to work best when started relatively early.

You are very likely to be asked your take on probiotics for a wide range of conditions, Dr. Cabana said, Overall, however, skepticism is warranted. Advise patients and families to be aware of advertising that promotes many different products as “probiotic,” especially around claims of improved “gut health” or “balanced microbiota.” He emphasized: “Make sure what your patients are using has some evidence behind it.”

Knowing the particular probiotic strain is essential to researching the evidence around its use, said Dr. Cabana, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco. “I used the Canis familiaris example. All dogs are C. familiaris. But there are different breeds. You want to make sure you match the right breed to the task. If you were in an avalanche in the Swiss Alps, you would want a St. Bernard to rescue you, not a Chihuahua,” he said. “Similarly, when you are using probiotics you want to make sure you have the right strain, not just the genus and species.” For example, if a product label states it contains Bifidobacterium breve C50, the “C50” is the strain.

Another tip is to look for labeling that lists probiotic concentrations in colony-forming units or CFUs, Dr. Cabana said. He’s seen concentrations listed in mg, a red flag that a product is not legitimate.

Families also might ask if it’s better to take a probiotic supplement or choose food that contains probiotics. “Food products offer additional nutritional benefits, but you can give a relatively higher dose with supplements with a much lower volume ingested,” Dr. Cabana said. “And supplements theoretically provide a more consistent dose.” Speaking of dose, it’s difficult to counsel patients on dosing and frequency in general because probiotics really vary by the indication and formulation.

“As a pediatrician, I also get this question: Should kids get a lower dose of probiotic?” Dr. Cabana said. There are no known reports of toxicity associated with probiotic use in either adults or children, he said. “Unless a dose modification has been documented in a clinical trial, it is not clear that this is necessary. You’re just giving less of the probiotic.”

Treating diarrhea and antibiotic-associated diarrhea

When it comes to probiotics for treating acute diarrhea in children, “the literature is actually fairly good here,” Dr. Cabana said. More than 60 studies with an excess of 8,000 participants, the majority with rotavirus infection, suggests probiotics are not associated with any adverse effects and generally shorten duration of diarrhea.

In fact, Dr. Cabana added, multiple meta-analyses support a shorter course of diarrhea. He added, “Look at the units here – it’s hours, not days. You can treat, but on average it’s only 25 hours.” He added that a day less of diarrhea can be significant for patients and parents, however.

In another meta-analysis probiotics, particularly Lactobacillus strains, were analyzed for prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (JAMA. 2012 May 9;307[18]:1959-69). Researchers assessed 63 randomized controlled trials with nearly 12,000 participants. The pooled results showed a statistically significant positive reduction in antibiotic-associated diarrhea (relative risk, 0.58; P less than .001). “Note the number needed to treat to see the effect is 13, so it won’t work in every patient,” Dr. Cabana said.

“So prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea is well documented. However, it’s also highly dependent on patent adherence,” he emphasized.

The clinical evidence on colic

For treating babies with colic, the best evidence is behind use of Lactobacilus reuteri DSM 17938, Dr. Cabana said. It tends to work best in breastfed infants, babies not on any gastrointestinal meds, and babies that start therapy early in the course of symptoms. “Use in formula-fed infants is unknown, because there are not enough data so far,” he said.

In some cases, during a prenatal visit, soon-to-be-parents will ask if they should start a probiotic to prevent colic. Dr. Cabana has seen only one prophylaxis study for this indication (JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Mar;168[3]:228-33). In the study, 589 infants were randomly allocated to take L. reuteri DSM 17938 or placebo daily for 90 days. At 3 months of age, the researchers discovered a significantly shorter mean duration of daily crying in the probiotic group (38 vs. 71 minutes; P less than .01).

What’s known about efficacy for eczema

The evidence for treating a child who presents with eczema with probiotics does not support efficacy in general, Dr. Cabana said. And the evidence on prevention of atopic eczema is mixed.

For example, in a randomized, controlled study from Finland, investigators randomized mothers to receive Lactobacillus GG or placebo during the prenatal period (Lancet. 2001;357:1076-9). Of 132 of the children, 35% were later diagnosed with atopic eczema, and the rate in the probiotic group, 23%, was half the 46% rate in the placebo group.

In contrast, researchers found no benefit regarding prevention of atopic dermatitis when 105 pregnant women were randomized to Lactobacillus GG or placebo. At the age of 2 years, atopic dermatitis was diagnosed in 28% of the 50 children in the probiotic group and 27.3% of the 44 in the placebo group (Pediatrics. 2008;121:e850-6).

The region of Germany where the study was conducted was rural/agricultural, so the diet could be different, Dr. Cabana said. Also, the median duration of breastfeeding differed between the Finnish and German study population, 6.8 months versus 9.2 months, respectively. “So that could potentially explain it, or there are just differences that cannot be explained.”

For more information, Dr. Cabana recommended information provided by the International Scientific Association of Prebiotics & Probiotics (https://isappscience.org/infographics/). The association’s website has easy to understand infographics including: What are probiotics and what can they do for you?; What’s so special about fermented foods?; and How do you read a probiotic label?

Dr. Cabana reported he receives research support from the National Institutes of Health, Wyeth Nutrition, and Nestle; is on the speakers bureau for Merck; owns stocks or bonds in Abbot and AbbVie; and is a consultant for Mead Johnson, Abbott, Genentech, Biogaia, General Mills, and Nestle.

CHICAGO – Outside of that, things are less clear.

“In terms of diarrhea, the evidence is positive, but probiotics only provide about 25 hours of benefit. And treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea is really dependent on patient adherence,” said Michael D. Cabana, MD. When it comes to treating colic, there is a particular probiotic that looks promising, he added, but the research so far demonstrating effectiveness is limited to breastfed babies. Also, the probiotic therapy appears to work best when started relatively early.

You are very likely to be asked your take on probiotics for a wide range of conditions, Dr. Cabana said, Overall, however, skepticism is warranted. Advise patients and families to be aware of advertising that promotes many different products as “probiotic,” especially around claims of improved “gut health” or “balanced microbiota.” He emphasized: “Make sure what your patients are using has some evidence behind it.”

Knowing the particular probiotic strain is essential to researching the evidence around its use, said Dr. Cabana, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco. “I used the Canis familiaris example. All dogs are C. familiaris. But there are different breeds. You want to make sure you match the right breed to the task. If you were in an avalanche in the Swiss Alps, you would want a St. Bernard to rescue you, not a Chihuahua,” he said. “Similarly, when you are using probiotics you want to make sure you have the right strain, not just the genus and species.” For example, if a product label states it contains Bifidobacterium breve C50, the “C50” is the strain.

Another tip is to look for labeling that lists probiotic concentrations in colony-forming units or CFUs, Dr. Cabana said. He’s seen concentrations listed in mg, a red flag that a product is not legitimate.

Families also might ask if it’s better to take a probiotic supplement or choose food that contains probiotics. “Food products offer additional nutritional benefits, but you can give a relatively higher dose with supplements with a much lower volume ingested,” Dr. Cabana said. “And supplements theoretically provide a more consistent dose.” Speaking of dose, it’s difficult to counsel patients on dosing and frequency in general because probiotics really vary by the indication and formulation.

“As a pediatrician, I also get this question: Should kids get a lower dose of probiotic?” Dr. Cabana said. There are no known reports of toxicity associated with probiotic use in either adults or children, he said. “Unless a dose modification has been documented in a clinical trial, it is not clear that this is necessary. You’re just giving less of the probiotic.”

Treating diarrhea and antibiotic-associated diarrhea

When it comes to probiotics for treating acute diarrhea in children, “the literature is actually fairly good here,” Dr. Cabana said. More than 60 studies with an excess of 8,000 participants, the majority with rotavirus infection, suggests probiotics are not associated with any adverse effects and generally shorten duration of diarrhea.

In fact, Dr. Cabana added, multiple meta-analyses support a shorter course of diarrhea. He added, “Look at the units here – it’s hours, not days. You can treat, but on average it’s only 25 hours.” He added that a day less of diarrhea can be significant for patients and parents, however.

In another meta-analysis probiotics, particularly Lactobacillus strains, were analyzed for prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (JAMA. 2012 May 9;307[18]:1959-69). Researchers assessed 63 randomized controlled trials with nearly 12,000 participants. The pooled results showed a statistically significant positive reduction in antibiotic-associated diarrhea (relative risk, 0.58; P less than .001). “Note the number needed to treat to see the effect is 13, so it won’t work in every patient,” Dr. Cabana said.

“So prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea is well documented. However, it’s also highly dependent on patent adherence,” he emphasized.

The clinical evidence on colic

For treating babies with colic, the best evidence is behind use of Lactobacilus reuteri DSM 17938, Dr. Cabana said. It tends to work best in breastfed infants, babies not on any gastrointestinal meds, and babies that start therapy early in the course of symptoms. “Use in formula-fed infants is unknown, because there are not enough data so far,” he said.

In some cases, during a prenatal visit, soon-to-be-parents will ask if they should start a probiotic to prevent colic. Dr. Cabana has seen only one prophylaxis study for this indication (JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Mar;168[3]:228-33). In the study, 589 infants were randomly allocated to take L. reuteri DSM 17938 or placebo daily for 90 days. At 3 months of age, the researchers discovered a significantly shorter mean duration of daily crying in the probiotic group (38 vs. 71 minutes; P less than .01).

What’s known about efficacy for eczema

The evidence for treating a child who presents with eczema with probiotics does not support efficacy in general, Dr. Cabana said. And the evidence on prevention of atopic eczema is mixed.

For example, in a randomized, controlled study from Finland, investigators randomized mothers to receive Lactobacillus GG or placebo during the prenatal period (Lancet. 2001;357:1076-9). Of 132 of the children, 35% were later diagnosed with atopic eczema, and the rate in the probiotic group, 23%, was half the 46% rate in the placebo group.

In contrast, researchers found no benefit regarding prevention of atopic dermatitis when 105 pregnant women were randomized to Lactobacillus GG or placebo. At the age of 2 years, atopic dermatitis was diagnosed in 28% of the 50 children in the probiotic group and 27.3% of the 44 in the placebo group (Pediatrics. 2008;121:e850-6).

The region of Germany where the study was conducted was rural/agricultural, so the diet could be different, Dr. Cabana said. Also, the median duration of breastfeeding differed between the Finnish and German study population, 6.8 months versus 9.2 months, respectively. “So that could potentially explain it, or there are just differences that cannot be explained.”

For more information, Dr. Cabana recommended information provided by the International Scientific Association of Prebiotics & Probiotics (https://isappscience.org/infographics/). The association’s website has easy to understand infographics including: What are probiotics and what can they do for you?; What’s so special about fermented foods?; and How do you read a probiotic label?

Dr. Cabana reported he receives research support from the National Institutes of Health, Wyeth Nutrition, and Nestle; is on the speakers bureau for Merck; owns stocks or bonds in Abbot and AbbVie; and is a consultant for Mead Johnson, Abbott, Genentech, Biogaia, General Mills, and Nestle.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

Treatment of hemangioma with brand-name propranolol tied to fewer dosing errors

CHICAGO – Among physicians using generic propranolol to treat infantile hemangioma, 30% reported at least one patient experienced a miscalculation dosing error, a new survey showed. Among respondents who prescribed Hemangeol (Pierre Fabre Pharmaceuticals), 10% reported a similar error. The errors were made by either a provider or caregiver.

Confusion may have contributed to a second source of errors, said Elaine Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at St. Louis University in Missouri. Generic propranolol is supplied as a 20-mg/5-mL oral solution and a 40-mg/5-mL oral solution. “Any time you have more than one formulation, it’s a nidus for dispensing error by the pharmacy.”

“So if a doctor prescribes [the lower dose], which is what we always do for safety, and they get 40 [mg], the [patient] can become hypoglycemic, hypotensive, or bradycardic,” Dr. Siegfried said. “That’s not good.”

Dr. Siegfried and colleagues assessed survey responses from 223 physicians. The majority, 90%, reported prescribing generic propranolol to treat infantile hemangioma in the past. Sixty-percent reported also prescribing the brand name formulation approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2014. Most of those who completed the survey, 70%, were pediatric dermatologists; general dermatologists, pediatric otolaryngologists, and other specialists also participated.

A total of 18% of physicians surveyed reported a dispensing error associated with use of generic propranolol. Dr. Siegfried said such errors are not possible with the branded formulation because it is available only in a single concentration, a 4.28 mg/mL oral solution. She added that one central specialty pharmacy dispenses Hemangeol, further reducing the likelihood of errors.

Addressing cost concerns

“When this [branded] drug became available, I wondered why everyone was not prescribing it,” Dr. Siegfried said.

“One of the pushbacks with this drug is that people didn’t want to prescribe it because they thought it was too expensive.” She acknowledged the higher cost, but added the manufacturer has a program to provide the agent free-of-charge to families without health insurance who cannot afford the medicine. She added, “People with private insurance do have higher copays, but insurance generally pays for most of it, depending on the plan.”

Dr. Siegfried also emphasized that the manufacturer invested considerable time and money to bring the agent and its specific pediatric indication to market, generating scientific data on its safety and efficacy along the way. In contrast, generic propranolol has been available in the United States for decades as a beta-blocker. The discovery that the agent also could effectively treat infantile hemangioma was serendipitous, not based on preclinical efficacy, safety, or dosing studies.