User login

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 2016 National Conference and Exhibition

Challenges of influenza, measles, pertussis guide outbreak management

SAN FRANCISCO – Recent U.S. outbreaks of pertussis, influenza, and measles have revealed shifts in the diseases’ epidemiology, shifts that pose new prevention and management challenges, explained Yvonne Maldonado, MD, at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Routine immunizations prevent 33,000 child deaths a year in the United States, having reduced vaccine-preventable diseases by more than 90%, but outbreaks still occur, she said. The recent announcement that measles was eliminated from the Western Hemisphere, for example, doesn’t mean we won’t see cases, said Dr. Maldonado, vice chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Maldonado reviewed specific challenges for flu, pertussis, and measles.

Influenza

The biggest challenges with controlling influenza are the failure to vaccinate children and the variable circulating strains each season, which can impact the performance of that year’s vaccine. Those changing strains and other factors also mean that the populations most at risk for serious complications also vary each season.

The two new mechanisms of change in influenza strains are antigenic drift and antigenic shift. Antigenic drift involves mutations that occur during repeated replications in the RNA strains of the virus, shifting its configuration over time so that it may not respond to the same antigens that the original strain responded to. Antigenic shift, however, is responsible for the periodic pandemics, when a complete genetic reassortment abruptly occurs because a new major protein from a strain jumps from an animal population into the human population, forming a new hybrid strain in humans.

Pertussis

Unlike flu, pertussis did become very uncommon because of widespread vaccination up until the early 2000s. But rates have begun to climb again, largely because of problems with the vaccine over time. Until the 1990s, the DTP vaccine, which includes a whole pertussis bacterium, was highly effective at preventing pertussis but could cause febrile seizures, an adverse event that proved too intolerable for many families.

It was replaced with the acellular pertussis vaccine DTaP, but research in the past 5-10 years has revealed that the effectiveness of DTaP and Tdap vaccines wanes much more quickly than anticipated. Subsequently, pertussis rates have almost continuously climbed from the early 2000s through the present, reaching an incidence of more than 100 cases per 100,000 among children younger than 1 year.

One of the biggest challenges now is improving vaccination rates among pregnant women, who were recommended in 2015 to get the Tdap vaccine in every pregnancy so that the newborn would have some passively acquired protection during the first few months of life.

Ongoing outbreaks then become exacerbated by pockets of lower vaccination rates among children in general.

Measles

The only chink in the armor against measles is failure to vaccinate against it, Dr. Maldonado said. Though the disease was eliminated from the United States in 2000, measles cases peaked recently in 2014, when 31 outbreaks involving 667 cases occurred because of imported cases from the Philippines. The next year, 60% of the 189 cases in 2015 resulted from the multistate measles outbreak starting at Disneyland in California.

Most of the individuals in both those years’ outbreaks were not vaccinated or had an unknown vaccination status. Of the 110 individuals with measles in California from the Disneyland outbreak, 45% were not immunized. Twelve were too young for vaccination, but 37 were eligible to have been vaccinated, and 67% of these were not vaccinated because of personal beliefs.

Vaccination rates for measles must be considerably higher, around 92%-94% of the population, to prevent outbreaks than for most other diseases, because the virus is so incredibly contagious.

“Measles is so infectious because it can exist in tiny microdroplets less than 5 mcg that can sit in the air up to 2 hours,” Dr. Maldonado explained. Yet only 92.6% of kindergartners had had both their MMR doses in 2014, compared with the peak of 97% between 2002 to 2007.

When children across all ages who have not received both doses of the vaccine are taken into account, 12.5% of all U.S. children and adolescents are currently susceptible to measles – and a quarter of those aged 3 years and younger are, Maldonado said.

The keys to preventing measles are high national coverage rates, an aggressive public health response (because early diagnosis can limit transmission), and improved implementation of health care worker recommendations.

“We have to keep measles in mind whenever we see fevers and rashes,” Dr. Maldonado cautioned. “Unfortunately, we see fevers and rashes all the time, so what really helps is a history of international travel or a parent with international travel.”

For families planning overseas travel, parents are recommended to give their infants the MMR as young as 6 months. But that dose does not count toward the child’s two doses recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention schedule.

“It’s a very tough call with measles, because we never know when it might pop up,” Dr. Maldonado said. “Measles will be sporadic, but when it happens, it’s a really big deal. You basically have to reach out to your entire patient log for several days before the child came in.”

Managing suspected/confirmed outbreaks

To prepare for and manage suspected outbreaks of an infectious disease, Dr. Maldonado advised taking the following steps:

• Establish a plan for evaluating suspected or confirmed infectious disease outbreaks in your office setting.

• Identify and eliminate the source of the infection, such as providing a separate waiting room for coughing children.

• Prevent additional cases using screening questions at the front desk.

• Provide prompt and consistent ongoing evaluation to prevent or minimize transmission to others.

• Track disease trends and advice from the AAP, CDC, and local county public health officials and disease experts to engage in ongoing surveillance and communication.

• Identify the initial source and route of exposure to understand why an outbreak occurred and how to prevent similar ones in the future.

Dr. Maldonado reporting being a member of a data safety monitoring board for Pfizer.

SAN FRANCISCO – Recent U.S. outbreaks of pertussis, influenza, and measles have revealed shifts in the diseases’ epidemiology, shifts that pose new prevention and management challenges, explained Yvonne Maldonado, MD, at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Routine immunizations prevent 33,000 child deaths a year in the United States, having reduced vaccine-preventable diseases by more than 90%, but outbreaks still occur, she said. The recent announcement that measles was eliminated from the Western Hemisphere, for example, doesn’t mean we won’t see cases, said Dr. Maldonado, vice chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Maldonado reviewed specific challenges for flu, pertussis, and measles.

Influenza

The biggest challenges with controlling influenza are the failure to vaccinate children and the variable circulating strains each season, which can impact the performance of that year’s vaccine. Those changing strains and other factors also mean that the populations most at risk for serious complications also vary each season.

The two new mechanisms of change in influenza strains are antigenic drift and antigenic shift. Antigenic drift involves mutations that occur during repeated replications in the RNA strains of the virus, shifting its configuration over time so that it may not respond to the same antigens that the original strain responded to. Antigenic shift, however, is responsible for the periodic pandemics, when a complete genetic reassortment abruptly occurs because a new major protein from a strain jumps from an animal population into the human population, forming a new hybrid strain in humans.

Pertussis

Unlike flu, pertussis did become very uncommon because of widespread vaccination up until the early 2000s. But rates have begun to climb again, largely because of problems with the vaccine over time. Until the 1990s, the DTP vaccine, which includes a whole pertussis bacterium, was highly effective at preventing pertussis but could cause febrile seizures, an adverse event that proved too intolerable for many families.

It was replaced with the acellular pertussis vaccine DTaP, but research in the past 5-10 years has revealed that the effectiveness of DTaP and Tdap vaccines wanes much more quickly than anticipated. Subsequently, pertussis rates have almost continuously climbed from the early 2000s through the present, reaching an incidence of more than 100 cases per 100,000 among children younger than 1 year.

One of the biggest challenges now is improving vaccination rates among pregnant women, who were recommended in 2015 to get the Tdap vaccine in every pregnancy so that the newborn would have some passively acquired protection during the first few months of life.

Ongoing outbreaks then become exacerbated by pockets of lower vaccination rates among children in general.

Measles

The only chink in the armor against measles is failure to vaccinate against it, Dr. Maldonado said. Though the disease was eliminated from the United States in 2000, measles cases peaked recently in 2014, when 31 outbreaks involving 667 cases occurred because of imported cases from the Philippines. The next year, 60% of the 189 cases in 2015 resulted from the multistate measles outbreak starting at Disneyland in California.

Most of the individuals in both those years’ outbreaks were not vaccinated or had an unknown vaccination status. Of the 110 individuals with measles in California from the Disneyland outbreak, 45% were not immunized. Twelve were too young for vaccination, but 37 were eligible to have been vaccinated, and 67% of these were not vaccinated because of personal beliefs.

Vaccination rates for measles must be considerably higher, around 92%-94% of the population, to prevent outbreaks than for most other diseases, because the virus is so incredibly contagious.

“Measles is so infectious because it can exist in tiny microdroplets less than 5 mcg that can sit in the air up to 2 hours,” Dr. Maldonado explained. Yet only 92.6% of kindergartners had had both their MMR doses in 2014, compared with the peak of 97% between 2002 to 2007.

When children across all ages who have not received both doses of the vaccine are taken into account, 12.5% of all U.S. children and adolescents are currently susceptible to measles – and a quarter of those aged 3 years and younger are, Maldonado said.

The keys to preventing measles are high national coverage rates, an aggressive public health response (because early diagnosis can limit transmission), and improved implementation of health care worker recommendations.

“We have to keep measles in mind whenever we see fevers and rashes,” Dr. Maldonado cautioned. “Unfortunately, we see fevers and rashes all the time, so what really helps is a history of international travel or a parent with international travel.”

For families planning overseas travel, parents are recommended to give their infants the MMR as young as 6 months. But that dose does not count toward the child’s two doses recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention schedule.

“It’s a very tough call with measles, because we never know when it might pop up,” Dr. Maldonado said. “Measles will be sporadic, but when it happens, it’s a really big deal. You basically have to reach out to your entire patient log for several days before the child came in.”

Managing suspected/confirmed outbreaks

To prepare for and manage suspected outbreaks of an infectious disease, Dr. Maldonado advised taking the following steps:

• Establish a plan for evaluating suspected or confirmed infectious disease outbreaks in your office setting.

• Identify and eliminate the source of the infection, such as providing a separate waiting room for coughing children.

• Prevent additional cases using screening questions at the front desk.

• Provide prompt and consistent ongoing evaluation to prevent or minimize transmission to others.

• Track disease trends and advice from the AAP, CDC, and local county public health officials and disease experts to engage in ongoing surveillance and communication.

• Identify the initial source and route of exposure to understand why an outbreak occurred and how to prevent similar ones in the future.

Dr. Maldonado reporting being a member of a data safety monitoring board for Pfizer.

SAN FRANCISCO – Recent U.S. outbreaks of pertussis, influenza, and measles have revealed shifts in the diseases’ epidemiology, shifts that pose new prevention and management challenges, explained Yvonne Maldonado, MD, at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Routine immunizations prevent 33,000 child deaths a year in the United States, having reduced vaccine-preventable diseases by more than 90%, but outbreaks still occur, she said. The recent announcement that measles was eliminated from the Western Hemisphere, for example, doesn’t mean we won’t see cases, said Dr. Maldonado, vice chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Maldonado reviewed specific challenges for flu, pertussis, and measles.

Influenza

The biggest challenges with controlling influenza are the failure to vaccinate children and the variable circulating strains each season, which can impact the performance of that year’s vaccine. Those changing strains and other factors also mean that the populations most at risk for serious complications also vary each season.

The two new mechanisms of change in influenza strains are antigenic drift and antigenic shift. Antigenic drift involves mutations that occur during repeated replications in the RNA strains of the virus, shifting its configuration over time so that it may not respond to the same antigens that the original strain responded to. Antigenic shift, however, is responsible for the periodic pandemics, when a complete genetic reassortment abruptly occurs because a new major protein from a strain jumps from an animal population into the human population, forming a new hybrid strain in humans.

Pertussis

Unlike flu, pertussis did become very uncommon because of widespread vaccination up until the early 2000s. But rates have begun to climb again, largely because of problems with the vaccine over time. Until the 1990s, the DTP vaccine, which includes a whole pertussis bacterium, was highly effective at preventing pertussis but could cause febrile seizures, an adverse event that proved too intolerable for many families.

It was replaced with the acellular pertussis vaccine DTaP, but research in the past 5-10 years has revealed that the effectiveness of DTaP and Tdap vaccines wanes much more quickly than anticipated. Subsequently, pertussis rates have almost continuously climbed from the early 2000s through the present, reaching an incidence of more than 100 cases per 100,000 among children younger than 1 year.

One of the biggest challenges now is improving vaccination rates among pregnant women, who were recommended in 2015 to get the Tdap vaccine in every pregnancy so that the newborn would have some passively acquired protection during the first few months of life.

Ongoing outbreaks then become exacerbated by pockets of lower vaccination rates among children in general.

Measles

The only chink in the armor against measles is failure to vaccinate against it, Dr. Maldonado said. Though the disease was eliminated from the United States in 2000, measles cases peaked recently in 2014, when 31 outbreaks involving 667 cases occurred because of imported cases from the Philippines. The next year, 60% of the 189 cases in 2015 resulted from the multistate measles outbreak starting at Disneyland in California.

Most of the individuals in both those years’ outbreaks were not vaccinated or had an unknown vaccination status. Of the 110 individuals with measles in California from the Disneyland outbreak, 45% were not immunized. Twelve were too young for vaccination, but 37 were eligible to have been vaccinated, and 67% of these were not vaccinated because of personal beliefs.

Vaccination rates for measles must be considerably higher, around 92%-94% of the population, to prevent outbreaks than for most other diseases, because the virus is so incredibly contagious.

“Measles is so infectious because it can exist in tiny microdroplets less than 5 mcg that can sit in the air up to 2 hours,” Dr. Maldonado explained. Yet only 92.6% of kindergartners had had both their MMR doses in 2014, compared with the peak of 97% between 2002 to 2007.

When children across all ages who have not received both doses of the vaccine are taken into account, 12.5% of all U.S. children and adolescents are currently susceptible to measles – and a quarter of those aged 3 years and younger are, Maldonado said.

The keys to preventing measles are high national coverage rates, an aggressive public health response (because early diagnosis can limit transmission), and improved implementation of health care worker recommendations.

“We have to keep measles in mind whenever we see fevers and rashes,” Dr. Maldonado cautioned. “Unfortunately, we see fevers and rashes all the time, so what really helps is a history of international travel or a parent with international travel.”

For families planning overseas travel, parents are recommended to give their infants the MMR as young as 6 months. But that dose does not count toward the child’s two doses recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention schedule.

“It’s a very tough call with measles, because we never know when it might pop up,” Dr. Maldonado said. “Measles will be sporadic, but when it happens, it’s a really big deal. You basically have to reach out to your entire patient log for several days before the child came in.”

Managing suspected/confirmed outbreaks

To prepare for and manage suspected outbreaks of an infectious disease, Dr. Maldonado advised taking the following steps:

• Establish a plan for evaluating suspected or confirmed infectious disease outbreaks in your office setting.

• Identify and eliminate the source of the infection, such as providing a separate waiting room for coughing children.

• Prevent additional cases using screening questions at the front desk.

• Provide prompt and consistent ongoing evaluation to prevent or minimize transmission to others.

• Track disease trends and advice from the AAP, CDC, and local county public health officials and disease experts to engage in ongoing surveillance and communication.

• Identify the initial source and route of exposure to understand why an outbreak occurred and how to prevent similar ones in the future.

Dr. Maldonado reporting being a member of a data safety monitoring board for Pfizer.

FROM AAP 16

New research in otitis media means new controversies

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

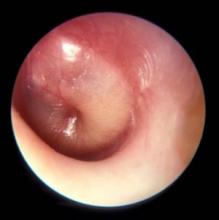

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

Wide spectrum of feeding problems poses challenge for clinicians

SAN FRANCISCO – Clinicians are likely to encounter diverse feeding problems in daily practice that will challenge their diagnostic and treatment acumen, Dr. Irene Chatoor told attendees of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These problems run the gamut from the most prevalent but least serious picky eating, to the least prevalent but most serious feeding disorders, she noted. Correspondingly, management will range from simple reassurance of parents to more intensive behavioral and medical interventions.

Assessment

“When you assess a feeding problem, you have to look at both the mother and father, and the child,” she advised. The parents are evaluated for their feeding style, while the child is evaluated for three feeding problems: limited appetite, selective intake, and fear of feeding (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:344-53).

Clinicians must be alert for organic red flags, such as dysphagia, aspiration, and vomiting, and for behavioral red flags, such as food fixation, abrupt cessation of feeding after a trigger event, and anticipatory gagging. An overarching red flag is failure to thrive.

Sometimes, a child will have both an organic condition and a behavioral feeding disorder at the same time. “It’s very important that you don’t think one excludes the other,” she cautioned.

Diagnosis

“To delineate milder feeding difficulties from feeding disorders, there must be some form of impairment caused by the feeding problem,” Dr. Chatoor commented. “Why is this important? For two reasons. One is for the insurance companies, because they don’t pay unless there is a disorder. And then there is research: you cannot do research unless you clearly define what you are studying.”

Children are considered to have impairment if they have weight loss or growth faltering, considerable nutritional deficiency, or a marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“When we diagnose feeding problems, it is best done with a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. Chatoor maintained. “I have learned many years ago that I’m not effective in helping parents deal with the feeding disorder if they are still in the back of their mind worried that the child has something organically wrong and that’s why the child does not want to eat.”

Accordingly, various team members perform a medical examination, a nutritional assessment, an oral motor and sensory evaluation, and a psychiatric or psychological assessment to identify the root cause or causes of the problem.

When it comes to behavioral etiologies, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) now groups all feeding and eating disorders together in one section, reflecting the fact that disorders starting early in life can and often do track into adolescence and adulthood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The manual also features a new diagnosis, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Key criteria include the presence of an eating or feeding disturbance that cannot be better explained by lack of available food, culturally sanctioned practices, or a concurrent medical condition or another mental disorder.

The child must have a persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, associated with any of four findings: significant weight loss or failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth, significant nutritional deficiencies, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“You need to have at least one but often you have a combination of nutritional and emotional impairment in the same child,” she commented.

ARFID and its treatment

There are three subtypes of ARFID having different features, treatments, and prognosis, although they all share in common food refusal, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The first subtype – apparent lack of interest in eating or food – emerges by 3 years of age, most often during the transition to self-feeding between 9 and 18 months. Affected children refuse to eat an adequate amount of food for at least 1 month, rarely communicate hunger, lack interest in food, and prefer to play or talk. They typically present with growth deficiency.

“If you have a child who refuses to eat, it generates anxiety in the mother. The mother does things she would not normally do with the child who is eating well. She starts to distract, to cajole, to sometimes even force-feed the child,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “And the more she engages in these behaviors, the more resistant the child becomes. So they become trapped in this vicious cycle.”

Treatment is aimed at removing this conflict with three approaches: explaining to parents the infant’s special temperament (notably, high arousal and difficulty turning off excitement); addressing their background, including any eating issues of their own, and difficulty with setting limits; and providing specific feeding guidelines and a time-out procedure.

The guidelines stress regular feeding, withholding of all snacks, keeping the child at the table for 20 to 30 minutes, and not using any distractions or pressure. Also, importantly, the parents should have dinner with their child. “I always tell the parents what is good for the child is good for you. It’s good for your whole family,” she said. “If they have other children, these rules apply to everybody. Young children learn to eat by watching their parents eating.”

With early and consistent use of these interventions, about two-thirds of children outgrow this eating/feeding disturbance by mid-childhood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

Children with the second subtype of ARFID – avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food – consistently refuse to eat certain foods having specific tastes, textures, temperatures, smells, and/or appearances. Onset occurs during the toddler years, when a new or different food is introduced.

“Not only do they refuse the same foods that were aversive, but they also generalize it. So these children are afraid to try other foods and they may end up limiting food groups – they don’t eat any vegetables and some of them don’t eat any meats,” she explained. “They are a challenge because this always causes a nutritional deficiency and they also have problems socially as they get older.”

Treatment varies by age, with gradual desensitization for infants and parent modeling of eating new foods for toddlers. A multifaceted approach is used for preschoolers, combining modeling, giving foods attractive shapes and names, having the child participate in food preparation, and using focused play therapy, such as feeding dolls who are “brave” and try new foods.

Clinicians can explain to affected school-aged children that they are “supertasters,” having more taste buds and therefore experiencing food more intensely, and that they can help their taste buds not react so strongly by starting to eat small amounts of new foods and gradually increasing over time. Parents can let the child make a list of 10 foods they would like to eat, and award them points for “courage” for every bite of a new food they try.

Prognosis of this type of ARFID varies, according to Dr. Chatoor. “Through gradual exposure, young children can expand the variety of foods they eat,” she elaborated. However, “some children become very rigid and brand sensitive in regard to the food they are willing to eat and begin to experience social problems during mid-childhood and adolescence. Some children grow up eating a limited diet, but finding ways to compensate nutritionally and socially.”

Children with the third subtype of ARFID – concern about aversive consequences of eating – have an acute onset of consistent food refusal at any age, from infancy onward, after experiencing a traumatic event or repeated traumatic insults to the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract that trigger distress in the child. These children often have comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or anxiety disorder.

“Treatment involves gradual desensitization to feared objects: the highchair, bib, bottle, or spoon,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “It also involves training of the mother in behavioral techniques to feed the child in spite of the child’s fear and distress.”

Any underlying medical condition causing pain or distress should be treated. Additional measures may include, for example, use of a graduated approach, starting with liquids and progressing to purees, if the child fears solid foods, and prescribing anxiolytic medication in cases of severe anxiety.

Dr. Chatoor disclosed that she has lectured internationally at conferences on feeding disorders that were organized by Abbott Nutrition International and that the company provided a research grant for a study on feeding.

SAN FRANCISCO – Clinicians are likely to encounter diverse feeding problems in daily practice that will challenge their diagnostic and treatment acumen, Dr. Irene Chatoor told attendees of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These problems run the gamut from the most prevalent but least serious picky eating, to the least prevalent but most serious feeding disorders, she noted. Correspondingly, management will range from simple reassurance of parents to more intensive behavioral and medical interventions.

Assessment

“When you assess a feeding problem, you have to look at both the mother and father, and the child,” she advised. The parents are evaluated for their feeding style, while the child is evaluated for three feeding problems: limited appetite, selective intake, and fear of feeding (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:344-53).

Clinicians must be alert for organic red flags, such as dysphagia, aspiration, and vomiting, and for behavioral red flags, such as food fixation, abrupt cessation of feeding after a trigger event, and anticipatory gagging. An overarching red flag is failure to thrive.

Sometimes, a child will have both an organic condition and a behavioral feeding disorder at the same time. “It’s very important that you don’t think one excludes the other,” she cautioned.

Diagnosis

“To delineate milder feeding difficulties from feeding disorders, there must be some form of impairment caused by the feeding problem,” Dr. Chatoor commented. “Why is this important? For two reasons. One is for the insurance companies, because they don’t pay unless there is a disorder. And then there is research: you cannot do research unless you clearly define what you are studying.”

Children are considered to have impairment if they have weight loss or growth faltering, considerable nutritional deficiency, or a marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“When we diagnose feeding problems, it is best done with a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. Chatoor maintained. “I have learned many years ago that I’m not effective in helping parents deal with the feeding disorder if they are still in the back of their mind worried that the child has something organically wrong and that’s why the child does not want to eat.”

Accordingly, various team members perform a medical examination, a nutritional assessment, an oral motor and sensory evaluation, and a psychiatric or psychological assessment to identify the root cause or causes of the problem.

When it comes to behavioral etiologies, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) now groups all feeding and eating disorders together in one section, reflecting the fact that disorders starting early in life can and often do track into adolescence and adulthood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The manual also features a new diagnosis, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Key criteria include the presence of an eating or feeding disturbance that cannot be better explained by lack of available food, culturally sanctioned practices, or a concurrent medical condition or another mental disorder.

The child must have a persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, associated with any of four findings: significant weight loss or failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth, significant nutritional deficiencies, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“You need to have at least one but often you have a combination of nutritional and emotional impairment in the same child,” she commented.

ARFID and its treatment

There are three subtypes of ARFID having different features, treatments, and prognosis, although they all share in common food refusal, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The first subtype – apparent lack of interest in eating or food – emerges by 3 years of age, most often during the transition to self-feeding between 9 and 18 months. Affected children refuse to eat an adequate amount of food for at least 1 month, rarely communicate hunger, lack interest in food, and prefer to play or talk. They typically present with growth deficiency.

“If you have a child who refuses to eat, it generates anxiety in the mother. The mother does things she would not normally do with the child who is eating well. She starts to distract, to cajole, to sometimes even force-feed the child,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “And the more she engages in these behaviors, the more resistant the child becomes. So they become trapped in this vicious cycle.”

Treatment is aimed at removing this conflict with three approaches: explaining to parents the infant’s special temperament (notably, high arousal and difficulty turning off excitement); addressing their background, including any eating issues of their own, and difficulty with setting limits; and providing specific feeding guidelines and a time-out procedure.

The guidelines stress regular feeding, withholding of all snacks, keeping the child at the table for 20 to 30 minutes, and not using any distractions or pressure. Also, importantly, the parents should have dinner with their child. “I always tell the parents what is good for the child is good for you. It’s good for your whole family,” she said. “If they have other children, these rules apply to everybody. Young children learn to eat by watching their parents eating.”

With early and consistent use of these interventions, about two-thirds of children outgrow this eating/feeding disturbance by mid-childhood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

Children with the second subtype of ARFID – avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food – consistently refuse to eat certain foods having specific tastes, textures, temperatures, smells, and/or appearances. Onset occurs during the toddler years, when a new or different food is introduced.

“Not only do they refuse the same foods that were aversive, but they also generalize it. So these children are afraid to try other foods and they may end up limiting food groups – they don’t eat any vegetables and some of them don’t eat any meats,” she explained. “They are a challenge because this always causes a nutritional deficiency and they also have problems socially as they get older.”

Treatment varies by age, with gradual desensitization for infants and parent modeling of eating new foods for toddlers. A multifaceted approach is used for preschoolers, combining modeling, giving foods attractive shapes and names, having the child participate in food preparation, and using focused play therapy, such as feeding dolls who are “brave” and try new foods.

Clinicians can explain to affected school-aged children that they are “supertasters,” having more taste buds and therefore experiencing food more intensely, and that they can help their taste buds not react so strongly by starting to eat small amounts of new foods and gradually increasing over time. Parents can let the child make a list of 10 foods they would like to eat, and award them points for “courage” for every bite of a new food they try.

Prognosis of this type of ARFID varies, according to Dr. Chatoor. “Through gradual exposure, young children can expand the variety of foods they eat,” she elaborated. However, “some children become very rigid and brand sensitive in regard to the food they are willing to eat and begin to experience social problems during mid-childhood and adolescence. Some children grow up eating a limited diet, but finding ways to compensate nutritionally and socially.”

Children with the third subtype of ARFID – concern about aversive consequences of eating – have an acute onset of consistent food refusal at any age, from infancy onward, after experiencing a traumatic event or repeated traumatic insults to the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract that trigger distress in the child. These children often have comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or anxiety disorder.

“Treatment involves gradual desensitization to feared objects: the highchair, bib, bottle, or spoon,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “It also involves training of the mother in behavioral techniques to feed the child in spite of the child’s fear and distress.”

Any underlying medical condition causing pain or distress should be treated. Additional measures may include, for example, use of a graduated approach, starting with liquids and progressing to purees, if the child fears solid foods, and prescribing anxiolytic medication in cases of severe anxiety.

Dr. Chatoor disclosed that she has lectured internationally at conferences on feeding disorders that were organized by Abbott Nutrition International and that the company provided a research grant for a study on feeding.

SAN FRANCISCO – Clinicians are likely to encounter diverse feeding problems in daily practice that will challenge their diagnostic and treatment acumen, Dr. Irene Chatoor told attendees of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These problems run the gamut from the most prevalent but least serious picky eating, to the least prevalent but most serious feeding disorders, she noted. Correspondingly, management will range from simple reassurance of parents to more intensive behavioral and medical interventions.

Assessment

“When you assess a feeding problem, you have to look at both the mother and father, and the child,” she advised. The parents are evaluated for their feeding style, while the child is evaluated for three feeding problems: limited appetite, selective intake, and fear of feeding (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:344-53).

Clinicians must be alert for organic red flags, such as dysphagia, aspiration, and vomiting, and for behavioral red flags, such as food fixation, abrupt cessation of feeding after a trigger event, and anticipatory gagging. An overarching red flag is failure to thrive.

Sometimes, a child will have both an organic condition and a behavioral feeding disorder at the same time. “It’s very important that you don’t think one excludes the other,” she cautioned.

Diagnosis

“To delineate milder feeding difficulties from feeding disorders, there must be some form of impairment caused by the feeding problem,” Dr. Chatoor commented. “Why is this important? For two reasons. One is for the insurance companies, because they don’t pay unless there is a disorder. And then there is research: you cannot do research unless you clearly define what you are studying.”

Children are considered to have impairment if they have weight loss or growth faltering, considerable nutritional deficiency, or a marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“When we diagnose feeding problems, it is best done with a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. Chatoor maintained. “I have learned many years ago that I’m not effective in helping parents deal with the feeding disorder if they are still in the back of their mind worried that the child has something organically wrong and that’s why the child does not want to eat.”

Accordingly, various team members perform a medical examination, a nutritional assessment, an oral motor and sensory evaluation, and a psychiatric or psychological assessment to identify the root cause or causes of the problem.

When it comes to behavioral etiologies, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) now groups all feeding and eating disorders together in one section, reflecting the fact that disorders starting early in life can and often do track into adolescence and adulthood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The manual also features a new diagnosis, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Key criteria include the presence of an eating or feeding disturbance that cannot be better explained by lack of available food, culturally sanctioned practices, or a concurrent medical condition or another mental disorder.

The child must have a persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, associated with any of four findings: significant weight loss or failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth, significant nutritional deficiencies, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“You need to have at least one but often you have a combination of nutritional and emotional impairment in the same child,” she commented.

ARFID and its treatment

There are three subtypes of ARFID having different features, treatments, and prognosis, although they all share in common food refusal, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The first subtype – apparent lack of interest in eating or food – emerges by 3 years of age, most often during the transition to self-feeding between 9 and 18 months. Affected children refuse to eat an adequate amount of food for at least 1 month, rarely communicate hunger, lack interest in food, and prefer to play or talk. They typically present with growth deficiency.

“If you have a child who refuses to eat, it generates anxiety in the mother. The mother does things she would not normally do with the child who is eating well. She starts to distract, to cajole, to sometimes even force-feed the child,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “And the more she engages in these behaviors, the more resistant the child becomes. So they become trapped in this vicious cycle.”

Treatment is aimed at removing this conflict with three approaches: explaining to parents the infant’s special temperament (notably, high arousal and difficulty turning off excitement); addressing their background, including any eating issues of their own, and difficulty with setting limits; and providing specific feeding guidelines and a time-out procedure.

The guidelines stress regular feeding, withholding of all snacks, keeping the child at the table for 20 to 30 minutes, and not using any distractions or pressure. Also, importantly, the parents should have dinner with their child. “I always tell the parents what is good for the child is good for you. It’s good for your whole family,” she said. “If they have other children, these rules apply to everybody. Young children learn to eat by watching their parents eating.”

With early and consistent use of these interventions, about two-thirds of children outgrow this eating/feeding disturbance by mid-childhood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

Children with the second subtype of ARFID – avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food – consistently refuse to eat certain foods having specific tastes, textures, temperatures, smells, and/or appearances. Onset occurs during the toddler years, when a new or different food is introduced.

“Not only do they refuse the same foods that were aversive, but they also generalize it. So these children are afraid to try other foods and they may end up limiting food groups – they don’t eat any vegetables and some of them don’t eat any meats,” she explained. “They are a challenge because this always causes a nutritional deficiency and they also have problems socially as they get older.”

Treatment varies by age, with gradual desensitization for infants and parent modeling of eating new foods for toddlers. A multifaceted approach is used for preschoolers, combining modeling, giving foods attractive shapes and names, having the child participate in food preparation, and using focused play therapy, such as feeding dolls who are “brave” and try new foods.

Clinicians can explain to affected school-aged children that they are “supertasters,” having more taste buds and therefore experiencing food more intensely, and that they can help their taste buds not react so strongly by starting to eat small amounts of new foods and gradually increasing over time. Parents can let the child make a list of 10 foods they would like to eat, and award them points for “courage” for every bite of a new food they try.

Prognosis of this type of ARFID varies, according to Dr. Chatoor. “Through gradual exposure, young children can expand the variety of foods they eat,” she elaborated. However, “some children become very rigid and brand sensitive in regard to the food they are willing to eat and begin to experience social problems during mid-childhood and adolescence. Some children grow up eating a limited diet, but finding ways to compensate nutritionally and socially.”

Children with the third subtype of ARFID – concern about aversive consequences of eating – have an acute onset of consistent food refusal at any age, from infancy onward, after experiencing a traumatic event or repeated traumatic insults to the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract that trigger distress in the child. These children often have comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or anxiety disorder.

“Treatment involves gradual desensitization to feared objects: the highchair, bib, bottle, or spoon,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “It also involves training of the mother in behavioral techniques to feed the child in spite of the child’s fear and distress.”

Any underlying medical condition causing pain or distress should be treated. Additional measures may include, for example, use of a graduated approach, starting with liquids and progressing to purees, if the child fears solid foods, and prescribing anxiolytic medication in cases of severe anxiety.

Dr. Chatoor disclosed that she has lectured internationally at conferences on feeding disorders that were organized by Abbott Nutrition International and that the company provided a research grant for a study on feeding.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 16

Pornography warps children’s concept of sex, sexual identity

SAN FRANCISCO – The pornography industry has taken over children’s sense of self and sexuality and warped their concept of what sex and a sexual identity is, said Gail Dines, PhD.

She challenged pediatricians to shape policy and help parents in wrangling back that control in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The culprit, Dr. Dines charged, is the multibillion-dollar porn industry that exploded around the year 2000 with the Internet. Then, in 2011, the business model shifted to free pornography to hook young boys in their adolescence and hopefully maintain them as customers after age 18 when they could get their own credit cards.

The average age of a boy’s first encounter with pornography is age 11, explained Dr. Dines, a professor of sociology and women’s studies at Wheelock College in Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Instead of a father’s Playboy featuring a naked woman in a cornfield, as many male pediatricians in the room might have been introduced to pornography or sexuality, today’s youth are introduced via the brutalization and dehumanization of women, she said. Such experiences traumatize the children viewing them, who become confused about who they are if they are masturbating to images and video of sexual violence, and then they enter a cycle of retraumatization that engenders shame while bringing children back to those sites again and again.

“Hence, in the business model of free porn, you are building in trauma, which is building in addiction,” Dr. Dines said. The effects of this exposure and addiction, based on decades of research, include limited capacity for intimacy, a greater likelihood of using coercive tactics for sex, decreased empathy for rape victims, increased depression and anxiety, and, most recently, rates of erectile dysfunction in males aged 15-27 that mirror the rates in those aged 27-35.

“We have never brought up boys with access to hard core pornography 24-7,” Dr. Dines said. The best way to tackle hard-core pornography is a public health model that educates parents and pediatricians who can band together to raise awareness. Her organization, Culture Reframed, is attempting to do precisely that.

Dr. Dines founded the nonprofit Culture Reframed, which attempts to counter the effects of the pornography industry and media sexuality. Her presentation used no external funding.

SAN FRANCISCO – The pornography industry has taken over children’s sense of self and sexuality and warped their concept of what sex and a sexual identity is, said Gail Dines, PhD.

She challenged pediatricians to shape policy and help parents in wrangling back that control in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The culprit, Dr. Dines charged, is the multibillion-dollar porn industry that exploded around the year 2000 with the Internet. Then, in 2011, the business model shifted to free pornography to hook young boys in their adolescence and hopefully maintain them as customers after age 18 when they could get their own credit cards.

The average age of a boy’s first encounter with pornography is age 11, explained Dr. Dines, a professor of sociology and women’s studies at Wheelock College in Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Instead of a father’s Playboy featuring a naked woman in a cornfield, as many male pediatricians in the room might have been introduced to pornography or sexuality, today’s youth are introduced via the brutalization and dehumanization of women, she said. Such experiences traumatize the children viewing them, who become confused about who they are if they are masturbating to images and video of sexual violence, and then they enter a cycle of retraumatization that engenders shame while bringing children back to those sites again and again.

“Hence, in the business model of free porn, you are building in trauma, which is building in addiction,” Dr. Dines said. The effects of this exposure and addiction, based on decades of research, include limited capacity for intimacy, a greater likelihood of using coercive tactics for sex, decreased empathy for rape victims, increased depression and anxiety, and, most recently, rates of erectile dysfunction in males aged 15-27 that mirror the rates in those aged 27-35.

“We have never brought up boys with access to hard core pornography 24-7,” Dr. Dines said. The best way to tackle hard-core pornography is a public health model that educates parents and pediatricians who can band together to raise awareness. Her organization, Culture Reframed, is attempting to do precisely that.

Dr. Dines founded the nonprofit Culture Reframed, which attempts to counter the effects of the pornography industry and media sexuality. Her presentation used no external funding.

SAN FRANCISCO – The pornography industry has taken over children’s sense of self and sexuality and warped their concept of what sex and a sexual identity is, said Gail Dines, PhD.

She challenged pediatricians to shape policy and help parents in wrangling back that control in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The culprit, Dr. Dines charged, is the multibillion-dollar porn industry that exploded around the year 2000 with the Internet. Then, in 2011, the business model shifted to free pornography to hook young boys in their adolescence and hopefully maintain them as customers after age 18 when they could get their own credit cards.

The average age of a boy’s first encounter with pornography is age 11, explained Dr. Dines, a professor of sociology and women’s studies at Wheelock College in Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Instead of a father’s Playboy featuring a naked woman in a cornfield, as many male pediatricians in the room might have been introduced to pornography or sexuality, today’s youth are introduced via the brutalization and dehumanization of women, she said. Such experiences traumatize the children viewing them, who become confused about who they are if they are masturbating to images and video of sexual violence, and then they enter a cycle of retraumatization that engenders shame while bringing children back to those sites again and again.

“Hence, in the business model of free porn, you are building in trauma, which is building in addiction,” Dr. Dines said. The effects of this exposure and addiction, based on decades of research, include limited capacity for intimacy, a greater likelihood of using coercive tactics for sex, decreased empathy for rape victims, increased depression and anxiety, and, most recently, rates of erectile dysfunction in males aged 15-27 that mirror the rates in those aged 27-35.

“We have never brought up boys with access to hard core pornography 24-7,” Dr. Dines said. The best way to tackle hard-core pornography is a public health model that educates parents and pediatricians who can band together to raise awareness. Her organization, Culture Reframed, is attempting to do precisely that.

Dr. Dines founded the nonprofit Culture Reframed, which attempts to counter the effects of the pornography industry and media sexuality. Her presentation used no external funding.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 16

Mental health integration into pediatric primary care offers multiple benefits

SAN FRANCISCO – Integrating pediatric mental health care into your primary care office can be an effective way to ensure your patients get the care they really need – and it’s easier than you think.

That’s the message Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, delivered to a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

He noted that depression and anxiety are among the top five conditions driving overall health costs in the United States, and a 1999 Surgeon General’s Report found that one in five children have a diagnosable mental disorder – but only a fifth to a quarter of these children receive treatment. The rub is that treatment is highly successful; it’s just difficult to access for many families, so making it a part of a child’s medical home just makes sense, Dr. Rabinowitz said.

To drive home his point, he described a case of a depressed adolescent with cutting and suicidal ideation, and the steps he would need to take without integration: find out their insurance, get a list of covered mental health professionals, refer to someone he may or may not heard of, and then rarely receive follow-up reports, much less confirmation the patient had gone to the appointment. With integrated care, parents can make appointments on their way out, he can read the psychologist’s report immediately after the visit, and he can drop in to say hello during the child’s mental health appointment.

“Sometimes there’s a question abut a medication or something, and sometimes it’s an inopportune moment if the child is sad or crying, but generally it seems to be pretty popular,” he said.

Taking steps toward integration

If providers are interesting in exploring the possibility of integration, they need to consider and decide on several issues before taking any concrete steps, Dr. Rabinowitz said. One is the type of arrangement that would work best for your practice: hiring on mental health professionals as employees of the practice, hiring independent contractors, coordinating a space share agreement or creating an out-of-office agreement.

“In our practice, psychologists are employees of the practice, but there are other arrangements,” he said, and some may depend on what is easiest based on state law or billing procedures.

The next question is what kind of provider(s) you would hire. His office has child psychologists with a PhD and postdoctorate fellowships working with children, but other possibilities include social workers, licensed counselors, psychiatric nurse practitioners, or psychiatrists.

Another consideration is what diagnoses your office will handle because it’s not possible to see everything. His practice sees patients in-house for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, anxiety, drug counseling, and behavioral and adjustment disorders. They choose to refer out educational testing, autism, difficult divorce cases, and complex cases that require more than 20 sessions. They refer out divorce cases because they frequently require specialized knowledge and a lot of court time and phone calls. Aside from ADHD evaluations, his office does not see the staff’s children.

Providers also should consider options for adapting their physical space to accommodate integration. His practice converted an exam room into a consultation room, making it homier with a throw rug, soft chairs, a painted wall, and office decor.

Establishing effective protocols with integration

The next step after providers decide to integrate is to determine the office protocols that govern what forms get used, who can schedule appointments and how long they last, billing, and similar procedures.

“You need to have certain protocols, and some of these things you don’t think about it until you start doing it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. Should mental health appointments be 50 minutes, for example, or 20 to 25 minutes? His office has gradually shrunk these appointments from 50 to 30 minutes, but they give psychologists an hour of time each day for follow-up phone calls.

Forms to consider developing include a disclosure form, notice of privacy practices, late cancel/no show policy, financial policy, and a summary of parent concerns. His office’s charting includes an extensive intake form with medical, treatment, family, and social history, an intake summary, and a progress note.

It’s with reimbursement, of course, that providers will need to do the most research, particularly with regard to their state’s laws and in looking for grants to provide funding – which is more available than many realize.

“Money is often out there if you look for it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.” Mental health is an area where no one is really against it: You get together the NRA (National Rifle Association) and the anti-gun movement, and they are both for it.”

Planning for reimbursement challenges

Reimbursement barriers can include lack of payment if mental health codes are used instead of pediatrics ones (depending on the practice arrangement), lack of “incident to” payments, same day billing of physical and mental health appointments, reimbursement for screening, and lack of payment for non–face-to-face services. Although a concierge or fee-for-service option solves many of these, it excludes Medicaid patients and is an economic barrier for many families.

Mental health networks offer a different route, but they can involve poor reimbursement and an additional layer of administration, which makes financial integration more viable as long as providers investigate their options.

“It’s going to be a regional variation, and you need to look at state rules and regulations,” Dr. Rabinowitz said, explaining that his office then sought insurance contracts to include mental health care reimbursement through their office and then sought the same from Medicaid.

“We weren’t about to see Medicaid patients for fear of an audit unless we got written permission, but we got that,” he said. His office simply asked for it and received in writing a letter starting as follows: “Under Department policy, they (our psychologists) may submit E&M claims to Medicaid under a supervising physician’s billing ID. It is not mandatory they be credentialed into a BHO (Behavioral Healthcare Options) network…”

He also noted that his state allows inclusion of psychologists on medical malpractice insurance policies, which is far less expensive for mental health professionals, compared with medical doctors.

Ultimately, the result of mental health integration into primary care practices is greater satisfaction among patients and pediatricians as well as potentially better health outcomes, Dr. Rabinowitz said. An in-house patient satisfaction survey his office conducted found that 91% of parents felt it was convenient for their child to receive mental health services at the same location as medical care, and 90% were satisfied with their care. Only 9% cited barriers to their child seeing a psychologist at their office, and 89% found the services beneficial for their child. Similarly, providers find integration more convenient, easier for follow-up, less stressful, and more efficient while improving communication, confidence, and follow-up.

Dr. Rabinowitz reported no disclosures. No external funding was used for the presentation.

SAN FRANCISCO – Integrating pediatric mental health care into your primary care office can be an effective way to ensure your patients get the care they really need – and it’s easier than you think.

That’s the message Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, delivered to a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

He noted that depression and anxiety are among the top five conditions driving overall health costs in the United States, and a 1999 Surgeon General’s Report found that one in five children have a diagnosable mental disorder – but only a fifth to a quarter of these children receive treatment. The rub is that treatment is highly successful; it’s just difficult to access for many families, so making it a part of a child’s medical home just makes sense, Dr. Rabinowitz said.

To drive home his point, he described a case of a depressed adolescent with cutting and suicidal ideation, and the steps he would need to take without integration: find out their insurance, get a list of covered mental health professionals, refer to someone he may or may not heard of, and then rarely receive follow-up reports, much less confirmation the patient had gone to the appointment. With integrated care, parents can make appointments on their way out, he can read the psychologist’s report immediately after the visit, and he can drop in to say hello during the child’s mental health appointment.

“Sometimes there’s a question abut a medication or something, and sometimes it’s an inopportune moment if the child is sad or crying, but generally it seems to be pretty popular,” he said.

Taking steps toward integration

If providers are interesting in exploring the possibility of integration, they need to consider and decide on several issues before taking any concrete steps, Dr. Rabinowitz said. One is the type of arrangement that would work best for your practice: hiring on mental health professionals as employees of the practice, hiring independent contractors, coordinating a space share agreement or creating an out-of-office agreement.

“In our practice, psychologists are employees of the practice, but there are other arrangements,” he said, and some may depend on what is easiest based on state law or billing procedures.

The next question is what kind of provider(s) you would hire. His office has child psychologists with a PhD and postdoctorate fellowships working with children, but other possibilities include social workers, licensed counselors, psychiatric nurse practitioners, or psychiatrists.