User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Duration of Adalimumab Therapy in Hidradenitis Suppurativa With and Without Oral Immunosuppressants

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

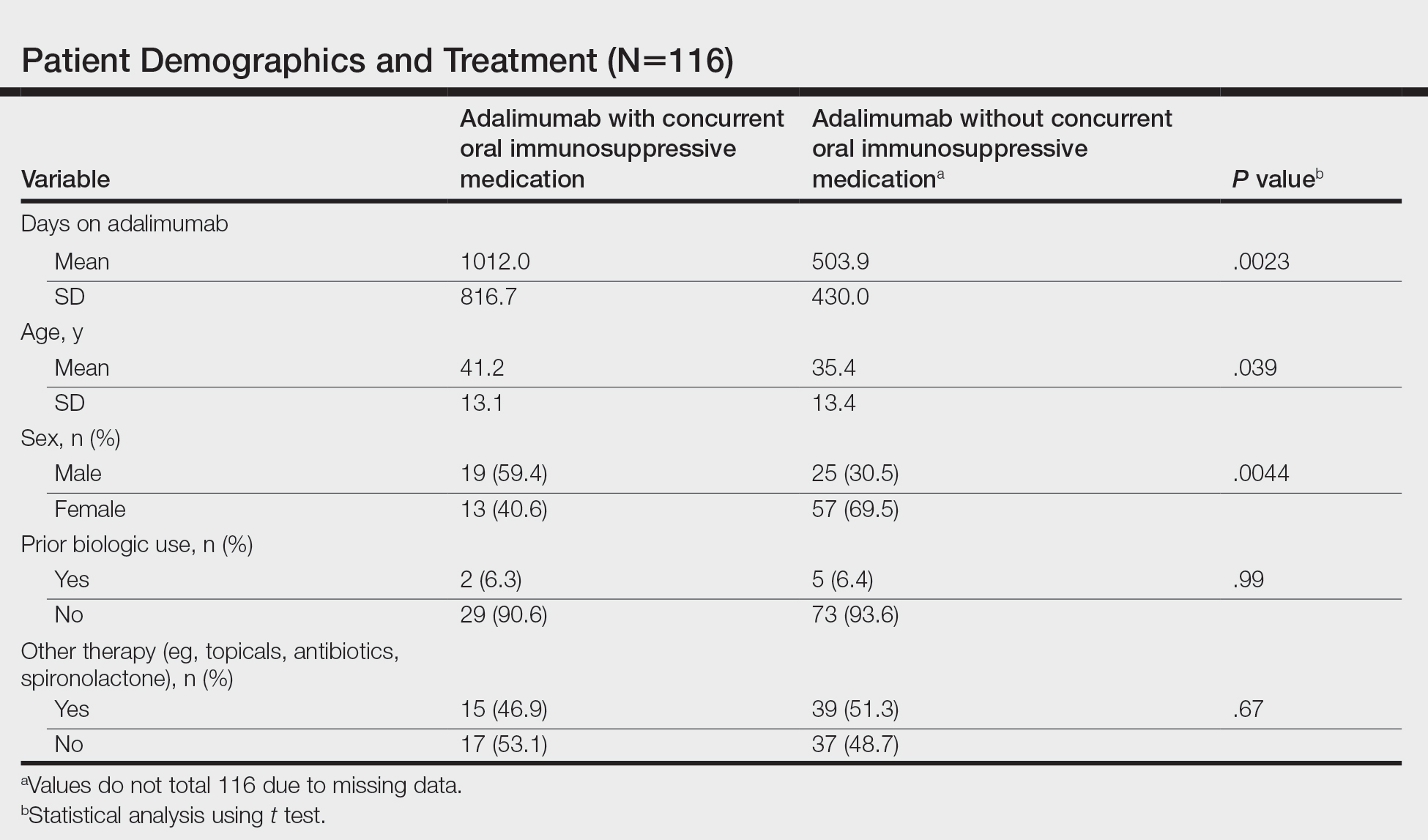

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

Practice Points

- Adalimumab is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), yet many patients on adalimumab do not achieve satisfactory results. New treatment options are in demand for patients affected by HS.

- Although combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil appears to be beneficial in treating other conditions such as psoriasis, these treatments may not have as great a benefit for patients with HS.

Mineral Oil Scabies Preparation From Under the Fingernail

Practice Gap

The Sarcoptes scabiei mite is a microscopic organism that causes scabies in the human host. The scabies mite is highly transmissible, making scabies a common disease in heavily populated areas. The mite survives by burrowing into the epidermis, where it feeds, lays eggs, and defecates.1

The rash in the host represents an allergic reaction to the body of the scabies mite, producing symptoms such as intense itching, rash, and erosions of the skin. The scabies rash tends to occur in warm and occluded areas of the body such as the hands, axillae, groin, buttocks, and feet.1,2

Delaying treatment of scabies can be hazardous because of the risk of rapid spread from one person to another. This rapid spread can be debilitating in specific populations, such as the immunocompromised, elderly, and disabled.

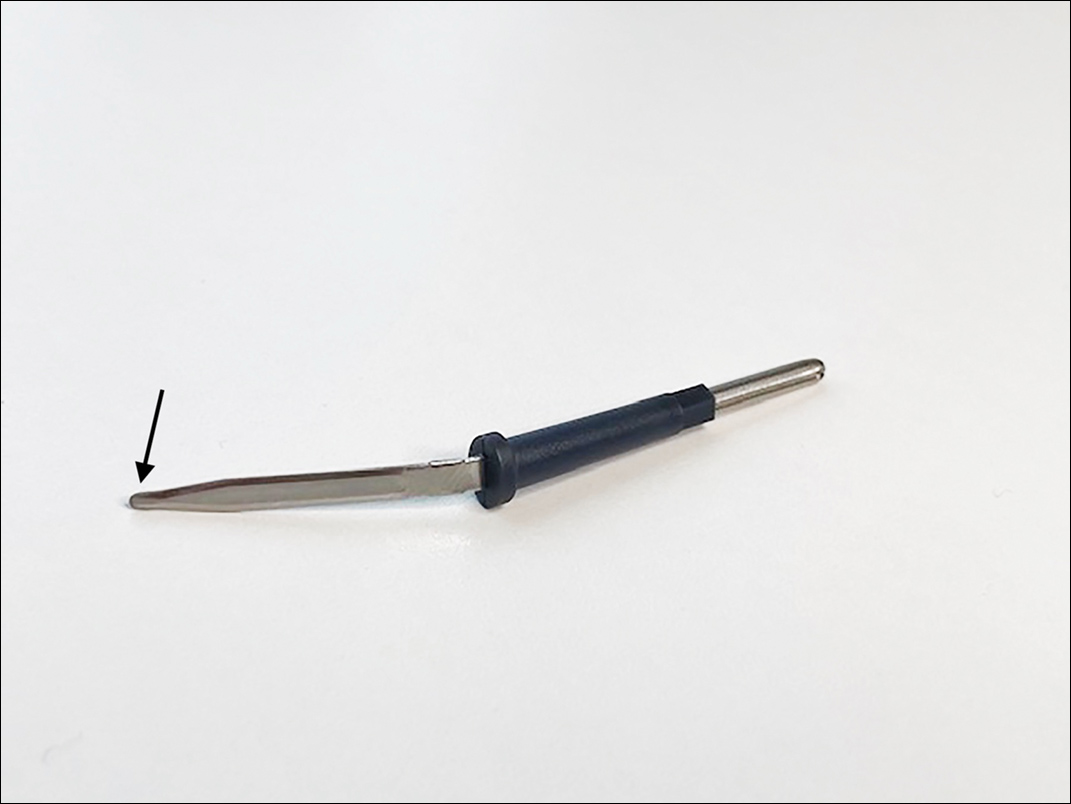

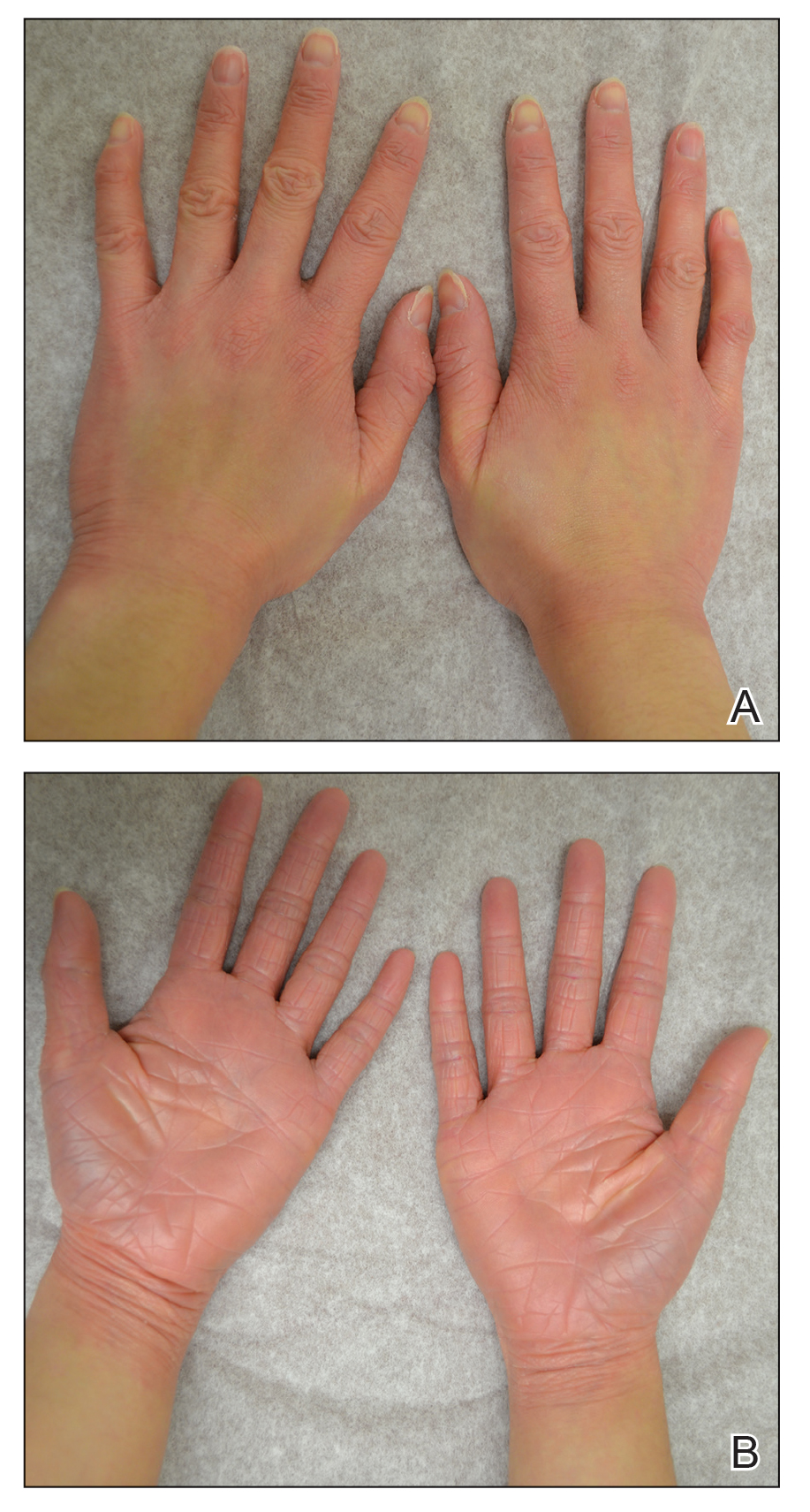

Mineral oil preparation is the classic method used to identify scabies (Figure 1). This method relies on obtaining mites by applying mineral oil to the skin and using a 15-mm blade to scrape off layers of the affected skin. The scraped material is spread onto a microscope slide with mineral oil, a coverslip is applied, and the specimen is analyzed by direct microscopy. This method proves only as effective as knowing where the few mites are located.

At any time, only 10 to 12 mites live on a human host.3 Therefore, it can be challenging to obtain a mite for diagnosis because the location of the skin mites may be unknown. Dermoscopy can be used to locate burrows and other signs of S scabiei. With a dermatoscope, the scabies mite can be identified by the so-called delta-wing jet sign.4

However, dermoscopy is not always successful because extensive hemorrhagic crusting and erosions of the skin secondary to constant scratching can obscure the appearance of burrows and mites. Because patients are constantly scratching areas of irritation, it is possible that S scabiei can be located under the fingernail of the dominant hand.

The Technique

To address this practice gap, a mineral oil scabies preparation can be performed by scraping under the fingernail plate at the level of the hyponychium. Mites might accumulate underneath the fingernails of the dominant hand when patients scratch the area of the skin where S scabiei mites are burrowing and reproducing.

A convenient and painless way to obtain a mineral oil scabies preparation from under the fingernail is to use the tip of a disposable hyfrecator, readily available in most dermatology practices for use in electrosurgery (Figure 2). Using the blunt end of the hyfrecator tip for the mineral oil preparation would be done without attachment to the full apparatus.

The hyponychium of the fingernail is prepared with mineral oil, which aids in collecting and suspending the material obtained from under the nail plate. Using the blunt end of the hyfrecator tip, material from underneath the fingernail is removed using a gentle sweeping motion (Figure 3). The specimen is then analyzed under the microscope similar to a routine mineral oil scabies preparation. This method can be utilized by health care providers for easy and painless diagnosis of scabies.

Practice Implications

Use of a blunt hyfrecator tip to extract S scabiei from underneath the fingernail plate can be used for efficient diagnosis of scabies. This technique can be implemented in any clinic where blunt-tip hyfrecator electrodes are available. Using a gentle sweeping motion, the blunt-tip hyfrecator allows the provider to extract material from under the fingernail for diagnosis. The material obtained is used to prepare a mineral oil scabies preparation for direct microscopic analysis.

This technique can diagnose scabies efficiently, and treatment can be initiated promptly. Use of a disposable blunt-tip hyfrecator for scabies extraction is a novel technique that can be added to the armamentarium of tools to diagnose scabies, which includes traditional mineral oil preparation and dermoscopy.

- Banerji A; Canadian Paediatric Society, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Committee. Scabies. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20:395-402. doi:10.1093/pch/20.7.395

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7517.619

- Mellanby K. The development of symptoms, parasitic infection and immunity in human scabies. Parasitology. 1944;35:197-206. doi:10.1017/S0031182000021612

- Fox G. Diagnosis of scabies by dermoscopy [published online February 2, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0279. doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0279

Practice Gap

The Sarcoptes scabiei mite is a microscopic organism that causes scabies in the human host. The scabies mite is highly transmissible, making scabies a common disease in heavily populated areas. The mite survives by burrowing into the epidermis, where it feeds, lays eggs, and defecates.1

The rash in the host represents an allergic reaction to the body of the scabies mite, producing symptoms such as intense itching, rash, and erosions of the skin. The scabies rash tends to occur in warm and occluded areas of the body such as the hands, axillae, groin, buttocks, and feet.1,2

Delaying treatment of scabies can be hazardous because of the risk of rapid spread from one person to another. This rapid spread can be debilitating in specific populations, such as the immunocompromised, elderly, and disabled.

Mineral oil preparation is the classic method used to identify scabies (Figure 1). This method relies on obtaining mites by applying mineral oil to the skin and using a 15-mm blade to scrape off layers of the affected skin. The scraped material is spread onto a microscope slide with mineral oil, a coverslip is applied, and the specimen is analyzed by direct microscopy. This method proves only as effective as knowing where the few mites are located.

At any time, only 10 to 12 mites live on a human host.3 Therefore, it can be challenging to obtain a mite for diagnosis because the location of the skin mites may be unknown. Dermoscopy can be used to locate burrows and other signs of S scabiei. With a dermatoscope, the scabies mite can be identified by the so-called delta-wing jet sign.4

However, dermoscopy is not always successful because extensive hemorrhagic crusting and erosions of the skin secondary to constant scratching can obscure the appearance of burrows and mites. Because patients are constantly scratching areas of irritation, it is possible that S scabiei can be located under the fingernail of the dominant hand.

The Technique

To address this practice gap, a mineral oil scabies preparation can be performed by scraping under the fingernail plate at the level of the hyponychium. Mites might accumulate underneath the fingernails of the dominant hand when patients scratch the area of the skin where S scabiei mites are burrowing and reproducing.

A convenient and painless way to obtain a mineral oil scabies preparation from under the fingernail is to use the tip of a disposable hyfrecator, readily available in most dermatology practices for use in electrosurgery (Figure 2). Using the blunt end of the hyfrecator tip for the mineral oil preparation would be done without attachment to the full apparatus.

The hyponychium of the fingernail is prepared with mineral oil, which aids in collecting and suspending the material obtained from under the nail plate. Using the blunt end of the hyfrecator tip, material from underneath the fingernail is removed using a gentle sweeping motion (Figure 3). The specimen is then analyzed under the microscope similar to a routine mineral oil scabies preparation. This method can be utilized by health care providers for easy and painless diagnosis of scabies.

Practice Implications

Use of a blunt hyfrecator tip to extract S scabiei from underneath the fingernail plate can be used for efficient diagnosis of scabies. This technique can be implemented in any clinic where blunt-tip hyfrecator electrodes are available. Using a gentle sweeping motion, the blunt-tip hyfrecator allows the provider to extract material from under the fingernail for diagnosis. The material obtained is used to prepare a mineral oil scabies preparation for direct microscopic analysis.

This technique can diagnose scabies efficiently, and treatment can be initiated promptly. Use of a disposable blunt-tip hyfrecator for scabies extraction is a novel technique that can be added to the armamentarium of tools to diagnose scabies, which includes traditional mineral oil preparation and dermoscopy.

Practice Gap

The Sarcoptes scabiei mite is a microscopic organism that causes scabies in the human host. The scabies mite is highly transmissible, making scabies a common disease in heavily populated areas. The mite survives by burrowing into the epidermis, where it feeds, lays eggs, and defecates.1

The rash in the host represents an allergic reaction to the body of the scabies mite, producing symptoms such as intense itching, rash, and erosions of the skin. The scabies rash tends to occur in warm and occluded areas of the body such as the hands, axillae, groin, buttocks, and feet.1,2

Delaying treatment of scabies can be hazardous because of the risk of rapid spread from one person to another. This rapid spread can be debilitating in specific populations, such as the immunocompromised, elderly, and disabled.

Mineral oil preparation is the classic method used to identify scabies (Figure 1). This method relies on obtaining mites by applying mineral oil to the skin and using a 15-mm blade to scrape off layers of the affected skin. The scraped material is spread onto a microscope slide with mineral oil, a coverslip is applied, and the specimen is analyzed by direct microscopy. This method proves only as effective as knowing where the few mites are located.

At any time, only 10 to 12 mites live on a human host.3 Therefore, it can be challenging to obtain a mite for diagnosis because the location of the skin mites may be unknown. Dermoscopy can be used to locate burrows and other signs of S scabiei. With a dermatoscope, the scabies mite can be identified by the so-called delta-wing jet sign.4

However, dermoscopy is not always successful because extensive hemorrhagic crusting and erosions of the skin secondary to constant scratching can obscure the appearance of burrows and mites. Because patients are constantly scratching areas of irritation, it is possible that S scabiei can be located under the fingernail of the dominant hand.

The Technique

To address this practice gap, a mineral oil scabies preparation can be performed by scraping under the fingernail plate at the level of the hyponychium. Mites might accumulate underneath the fingernails of the dominant hand when patients scratch the area of the skin where S scabiei mites are burrowing and reproducing.

A convenient and painless way to obtain a mineral oil scabies preparation from under the fingernail is to use the tip of a disposable hyfrecator, readily available in most dermatology practices for use in electrosurgery (Figure 2). Using the blunt end of the hyfrecator tip for the mineral oil preparation would be done without attachment to the full apparatus.

The hyponychium of the fingernail is prepared with mineral oil, which aids in collecting and suspending the material obtained from under the nail plate. Using the blunt end of the hyfrecator tip, material from underneath the fingernail is removed using a gentle sweeping motion (Figure 3). The specimen is then analyzed under the microscope similar to a routine mineral oil scabies preparation. This method can be utilized by health care providers for easy and painless diagnosis of scabies.

Practice Implications

Use of a blunt hyfrecator tip to extract S scabiei from underneath the fingernail plate can be used for efficient diagnosis of scabies. This technique can be implemented in any clinic where blunt-tip hyfrecator electrodes are available. Using a gentle sweeping motion, the blunt-tip hyfrecator allows the provider to extract material from under the fingernail for diagnosis. The material obtained is used to prepare a mineral oil scabies preparation for direct microscopic analysis.

This technique can diagnose scabies efficiently, and treatment can be initiated promptly. Use of a disposable blunt-tip hyfrecator for scabies extraction is a novel technique that can be added to the armamentarium of tools to diagnose scabies, which includes traditional mineral oil preparation and dermoscopy.

- Banerji A; Canadian Paediatric Society, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Committee. Scabies. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20:395-402. doi:10.1093/pch/20.7.395

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7517.619

- Mellanby K. The development of symptoms, parasitic infection and immunity in human scabies. Parasitology. 1944;35:197-206. doi:10.1017/S0031182000021612

- Fox G. Diagnosis of scabies by dermoscopy [published online February 2, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0279. doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0279

- Banerji A; Canadian Paediatric Society, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Committee. Scabies. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20:395-402. doi:10.1093/pch/20.7.395

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7517.619

- Mellanby K. The development of symptoms, parasitic infection and immunity in human scabies. Parasitology. 1944;35:197-206. doi:10.1017/S0031182000021612

- Fox G. Diagnosis of scabies by dermoscopy [published online February 2, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0279. doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0279

Cutaneous Manifestations and Clinical Disparities in Patients Without Housing

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

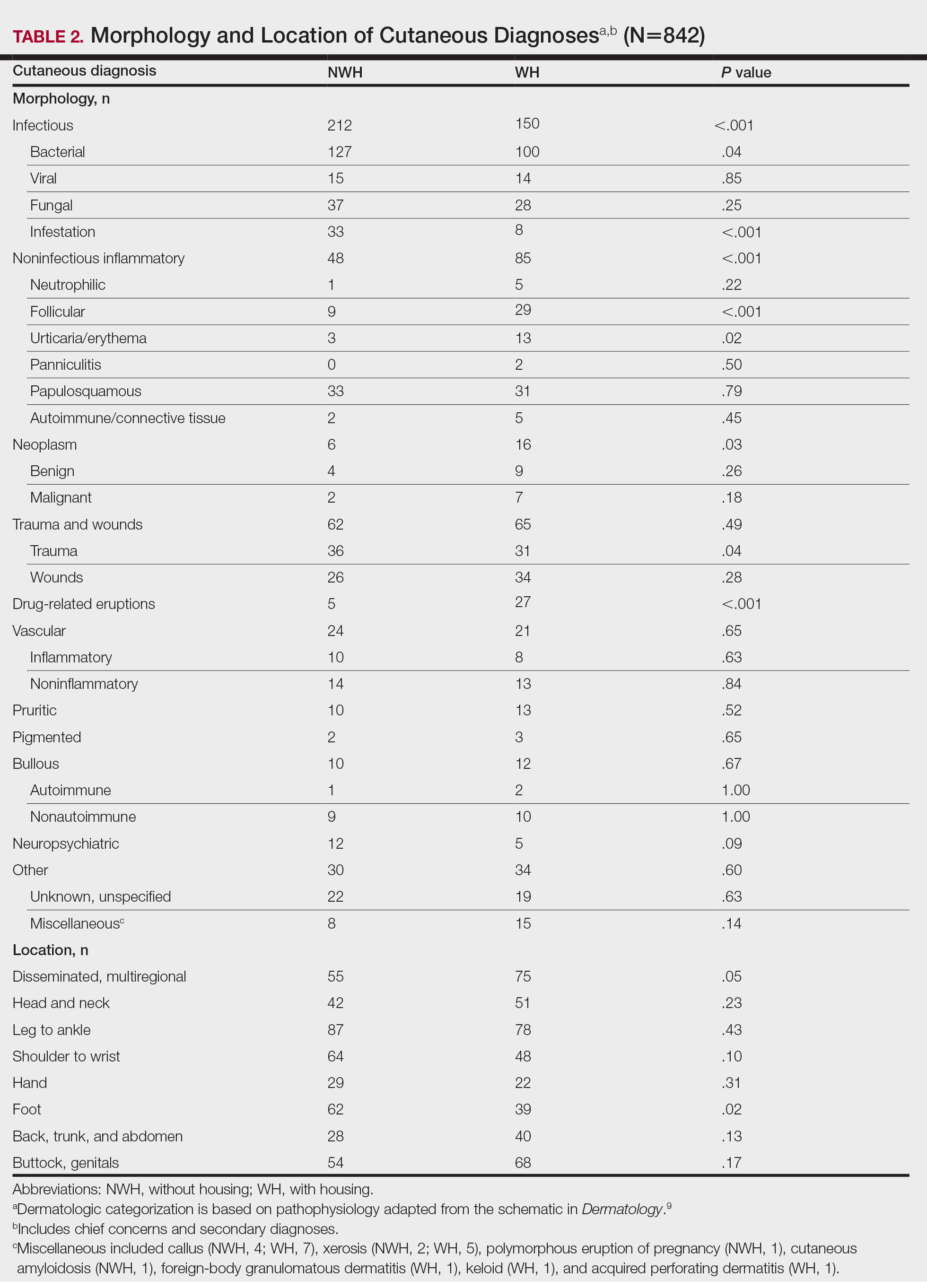

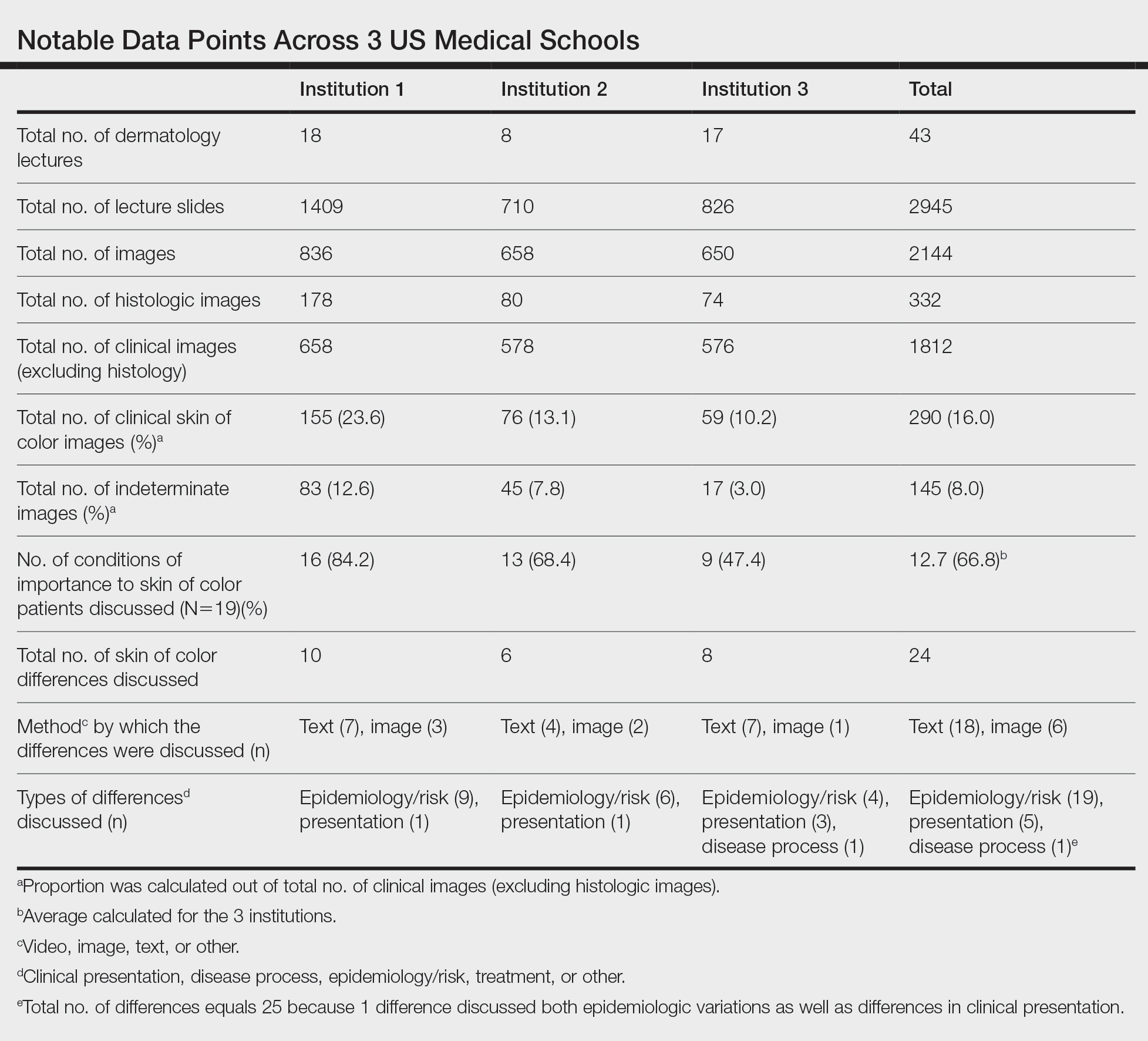

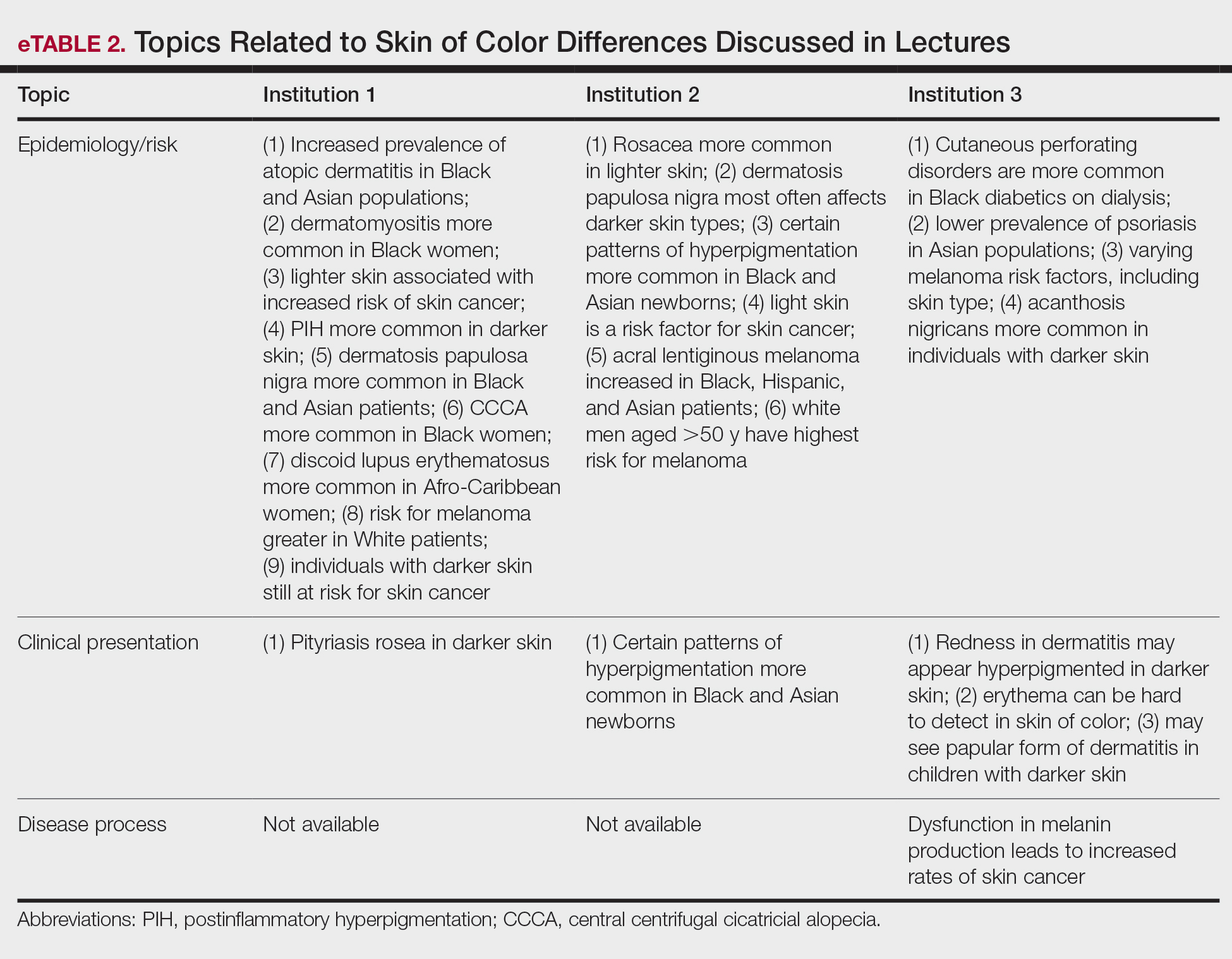

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

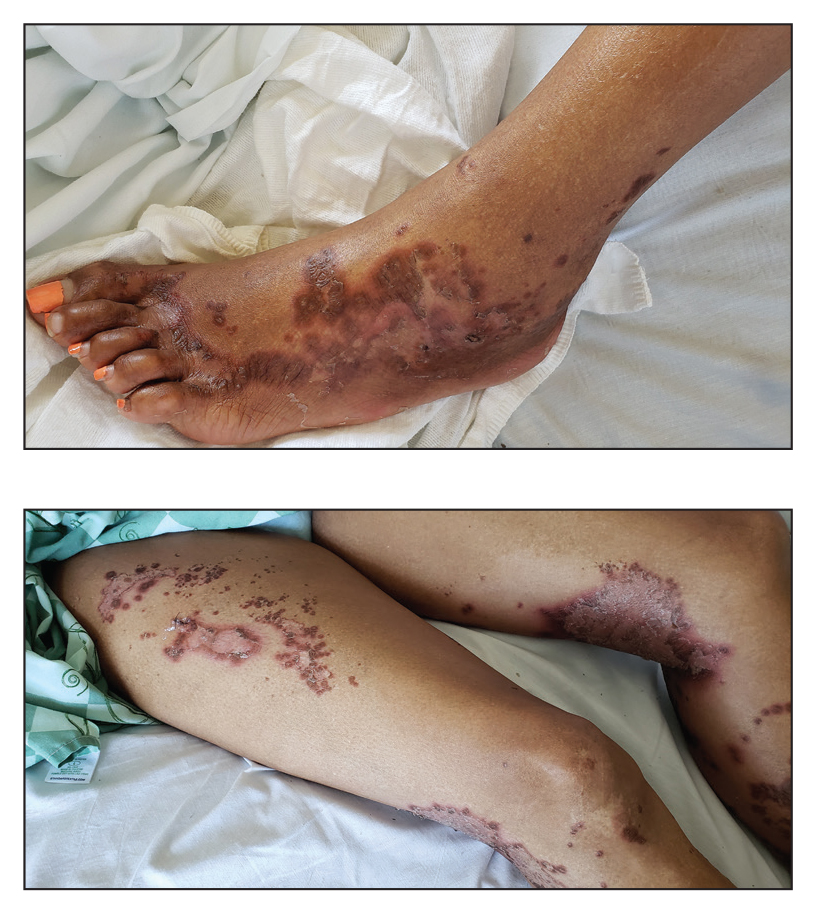

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

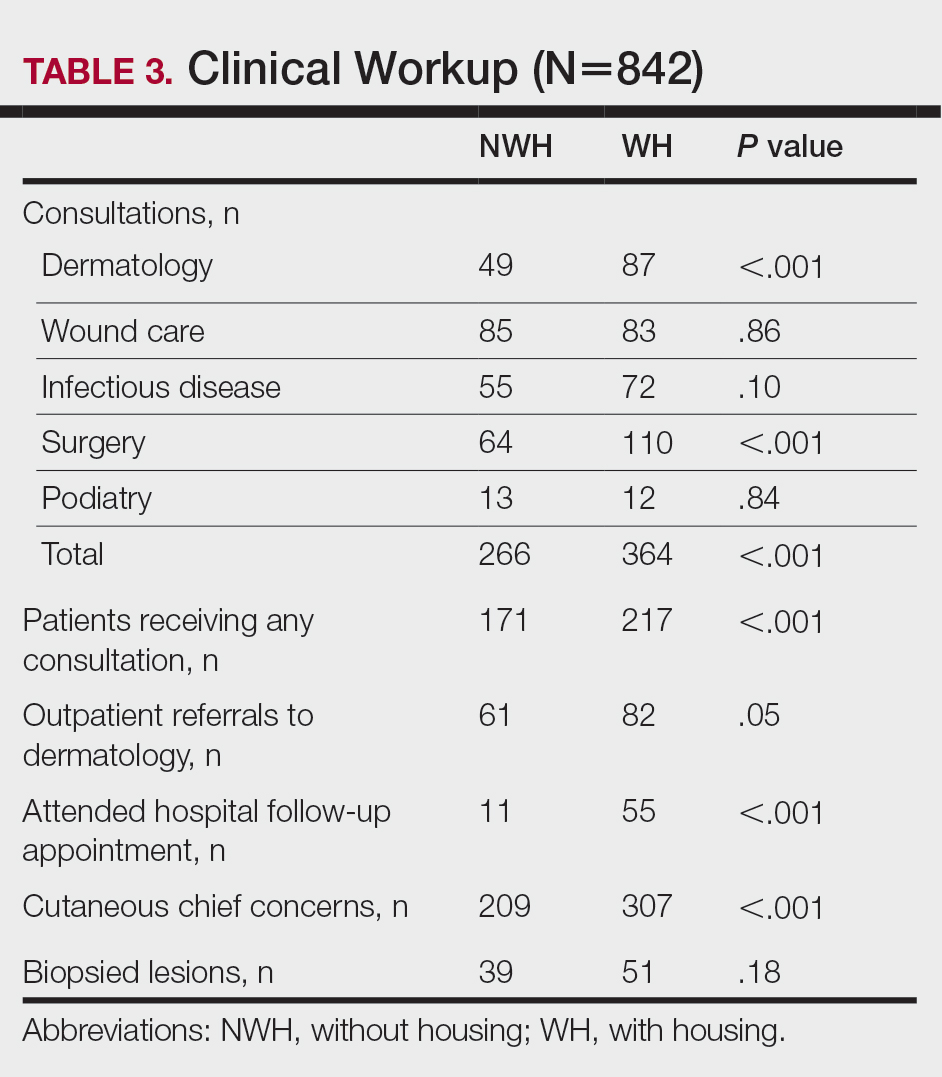

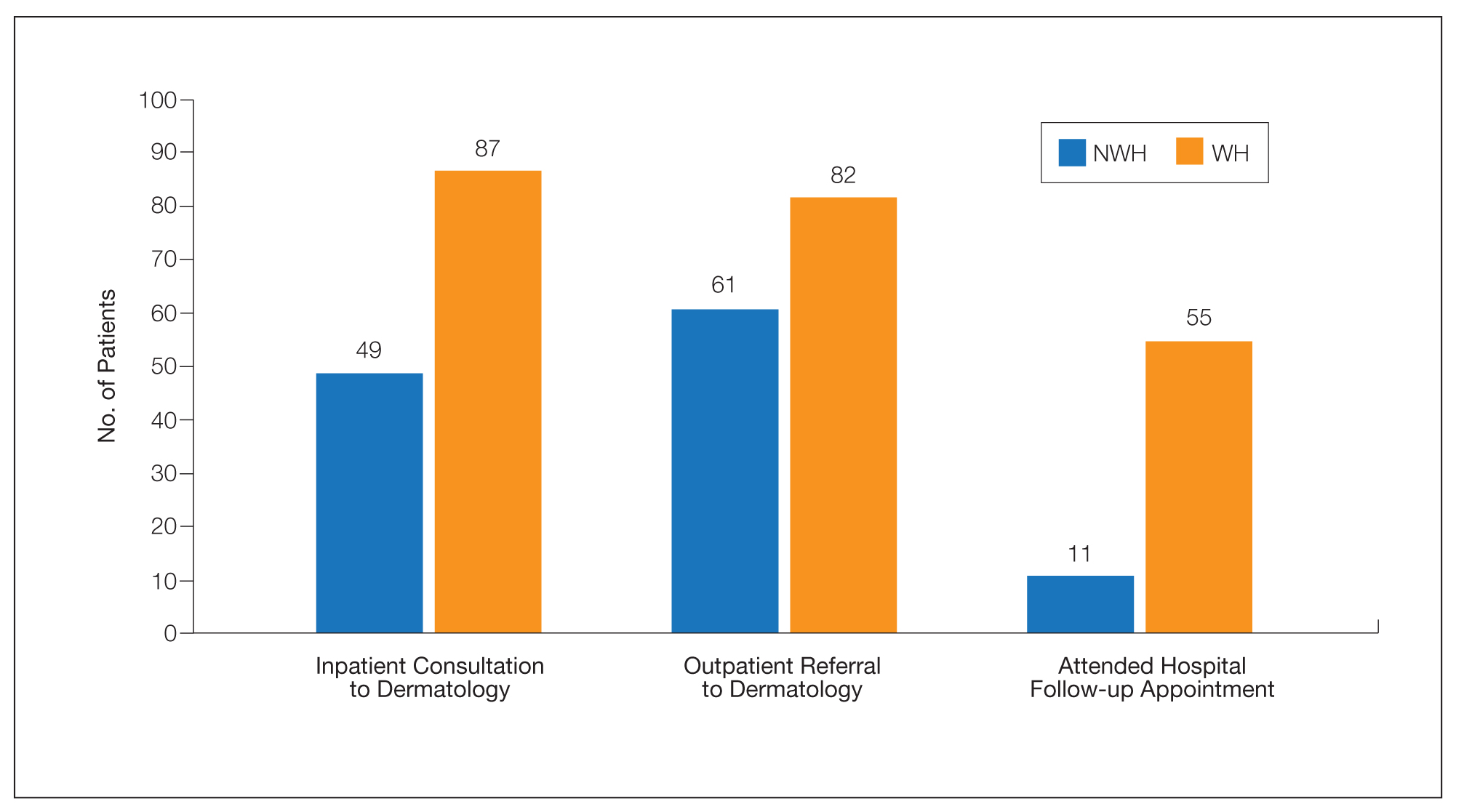

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

Practice Points

- Dermatologic disease in patients without housing (NWH) is characterized by more infectious concerns and fewer follicular and urticarial noninfectious inflammatory eruptions compared with matched controls of those with housing.

- Patients with housing more frequently presented with cutaneous chief concerns and received more consultations while in the hospital.

- This study uncovered notable pathological and clinical differences in treating dermatologic conditions in NWH patients.

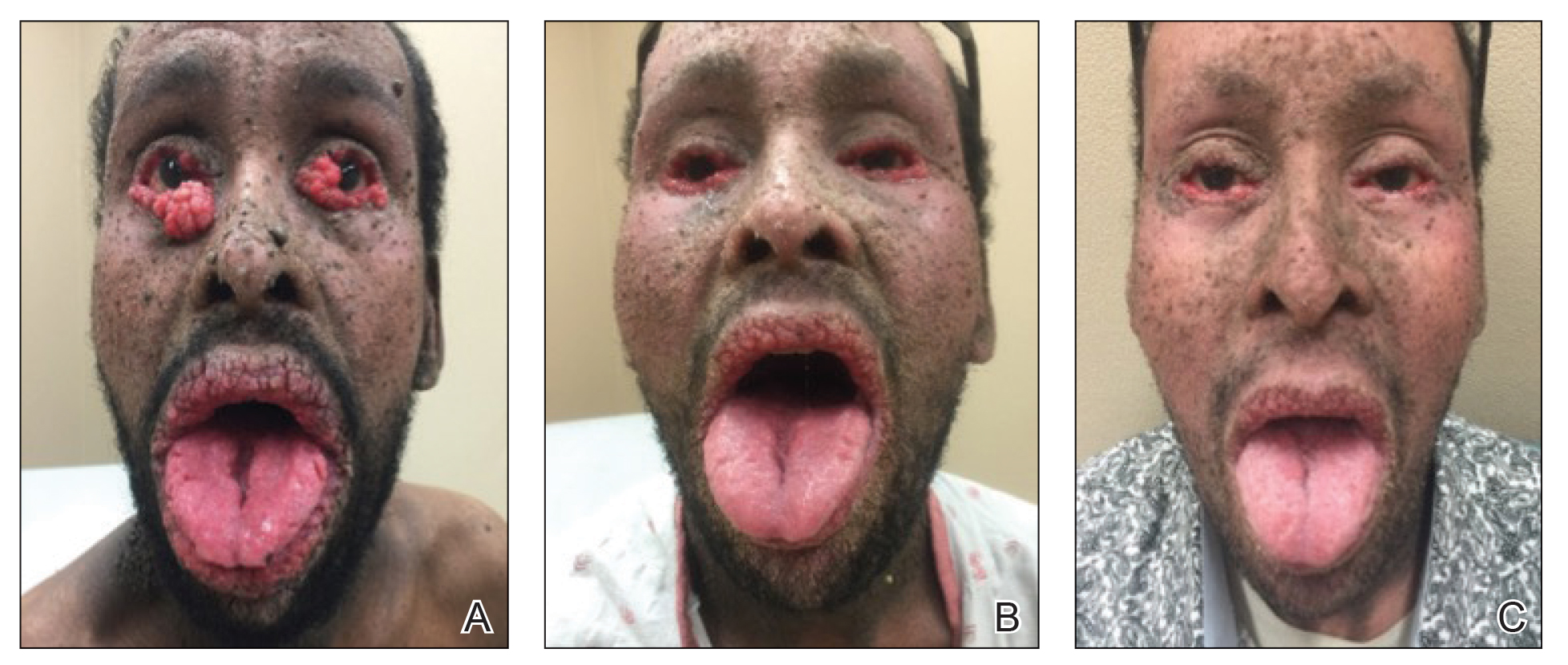

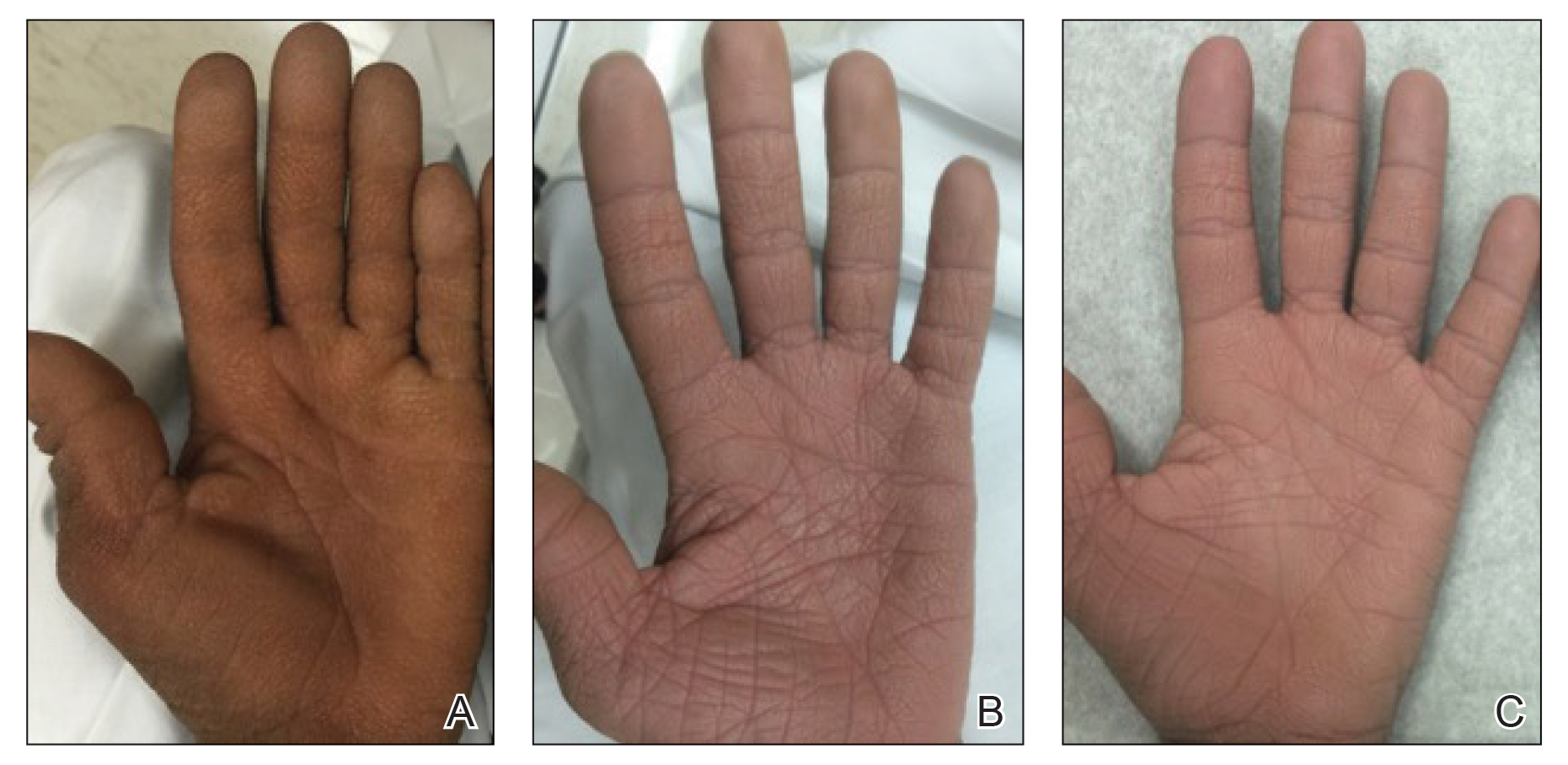

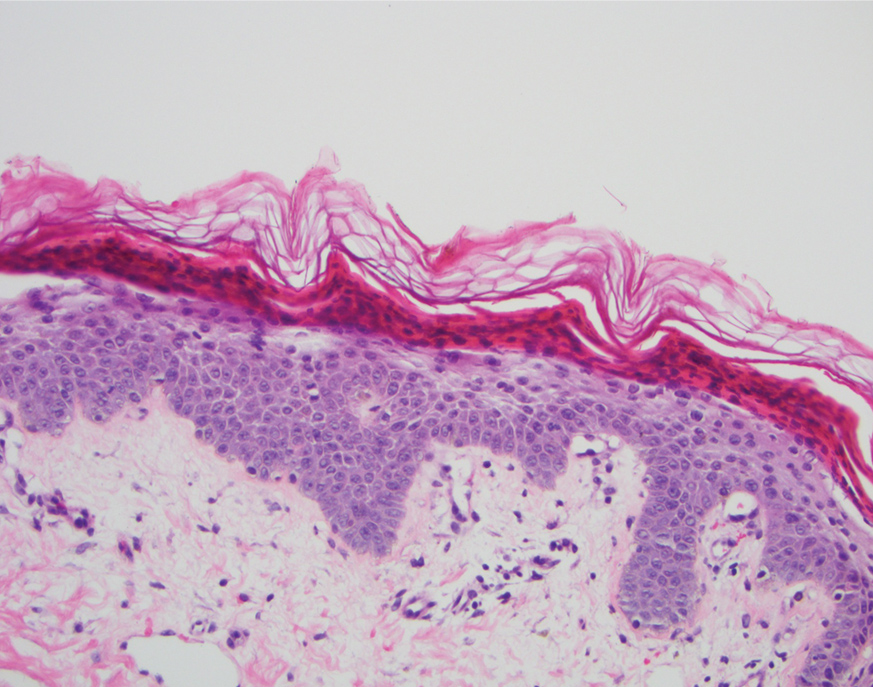

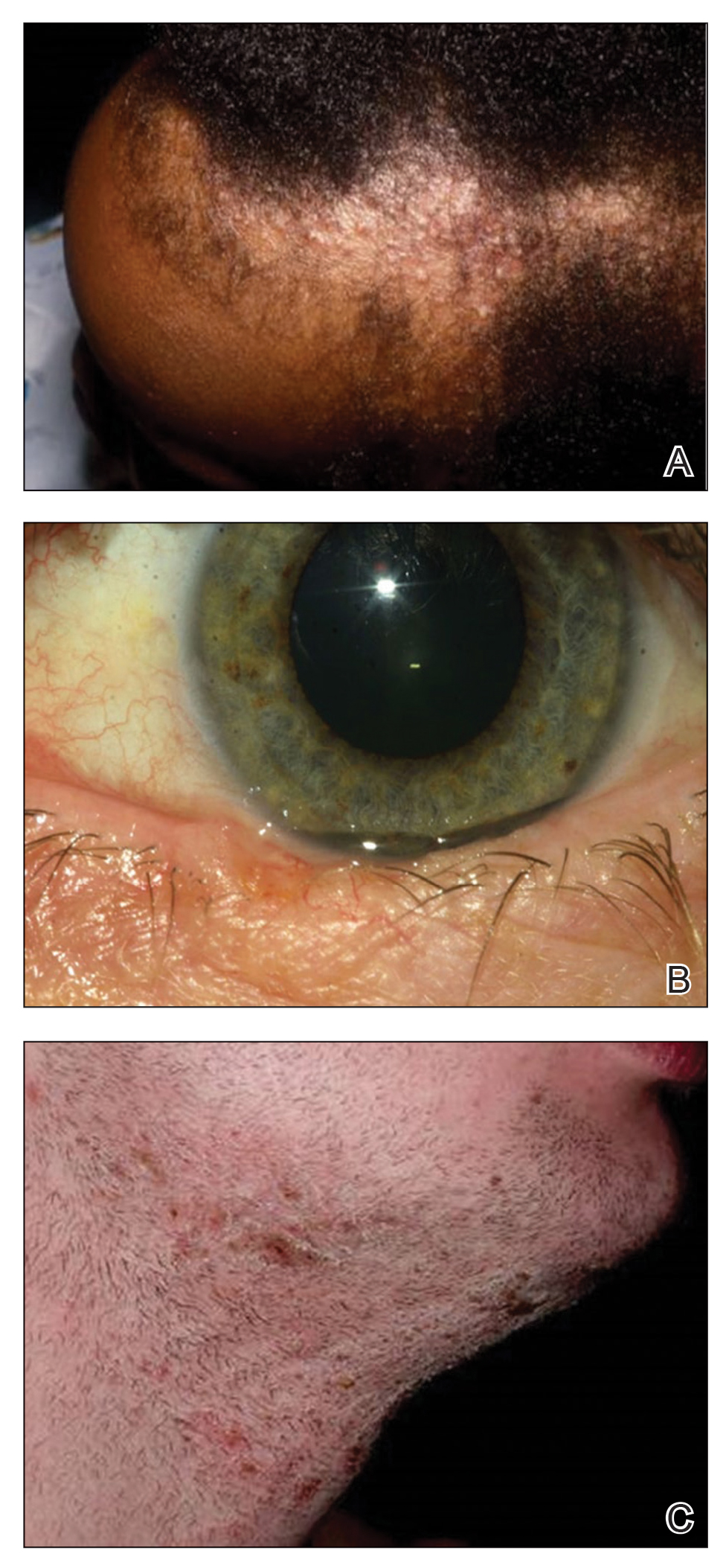

Acyclovir-Resistant Cutaneous Herpes Simplex Virus in DOCK8 Deficiency

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.