User login

Spring 2021 has arrived with summer quickly approaching. It is our second spring and summer during the pandemic. Travel restrictions have minimally eased for vaccinated adults. However, neither domestic nor international leisure travel is encouraged for anyone. Ironically, air travel is increasing. For many families, it is time to make decisions regarding summer activities. Outdoor activities have been encouraged throughout the pandemic, which makes it a good time to review tick-borne diseases. Depending on your location, your patients may only have to travel as far as their backyard to sustain a tick bite.

Ticks are a group of obligate, bloodsucking arthropods that feed on mammals, birds, and reptiles. There are three families of ticks. Two families, Ixodidae (hard-bodied ticks) and Argasidae (soft-bodied ticks) are responsible for transmitting the most diseases to humans in the United States. Once a tick is infected with a pathogen it usually survives and transmits it to its next host. Ticks efficiently transmit bacteria, spirochetes, protozoa, rickettsiae, nematodes, and toxins to humans during feeding when the site is exposed to infected salivary gland secretions or regurgitated midgut contents. Pathogen transmission can also occur when the feeding site is contaminated by feces or coxal fluid. Sometimes a tick can transmit multiple pathogens. Not all pathogens are infectious (e.g., tick paralysis, which occurs after exposure to a neurotoxin and red meat allergy because of alpha-gal). Ticks require a blood meal to transform to their next stage of development (larva to nymph to adult). Life cycles of hard and soft ticks differ with most hard ticks undergoing a 2-year life cycle and feeding slowly over many days. In contrast, soft ticks feed multiple times often for less than 1 hour and are capable of transmitting diseases in less than 1 minute.

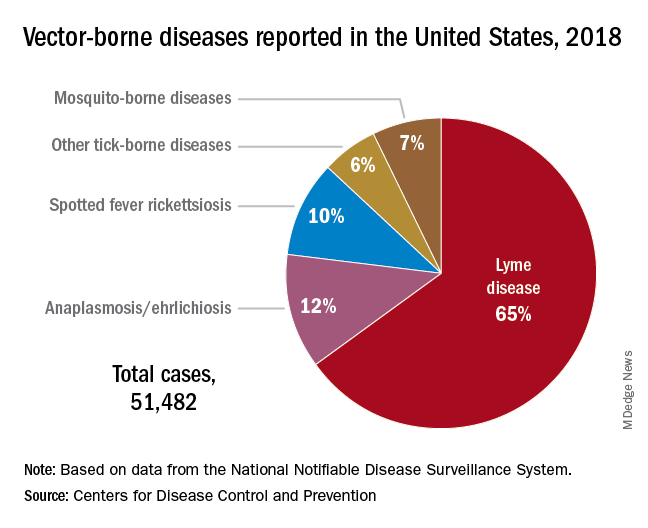

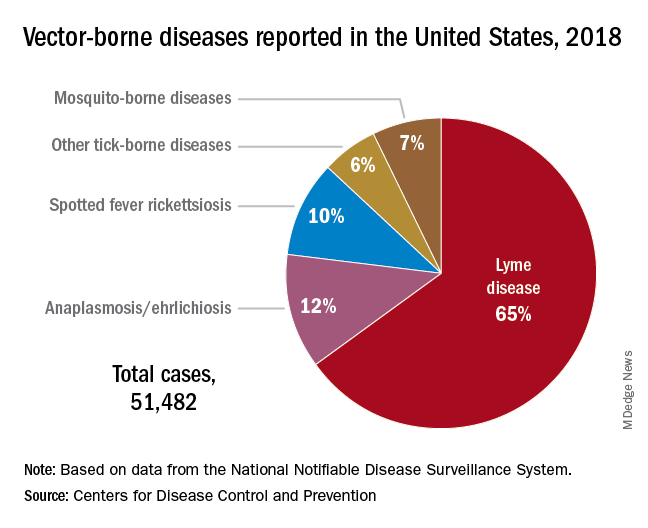

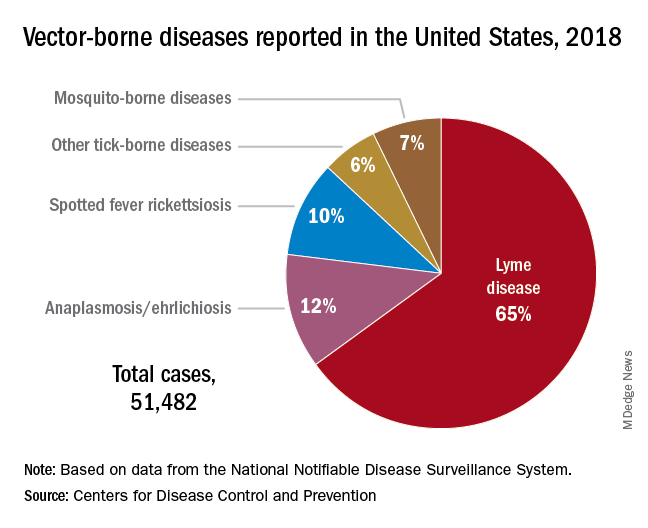

Rocky Mountain spotted fever was the first recognized tick-borne disease (TBD) in humans. Since then, 18 additional pathogens transmitted by ticks have been identified with 40% being described since 1980. The increased discovery of tickborne pathogens has been attributed to physician awareness of TBD and improved diagnostics. The number of cases of TBD has risen yearly. Ticks are responsible for most vector-transmitted diseases in the United States with Lyme disease most frequently reported.

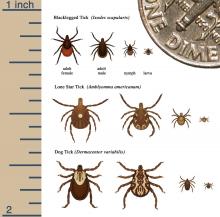

Mosquito transmission accounts for only 7% of vector-borne diseases. Three species of ticks are responsible for most human disease: Ixodes scapularis (Black-legged tick), Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), and Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick). Each is capable of transmitting agents that cause multiple diseases.

Risk for acquisition of a specific disease is dependent upon the type of tick, its geographic location, the season, and duration of the exposure.

Humans are usually incidental hosts. Tick exposure can occur year-round, but tick activity is greatest between April and September. Ticks are generally found near the ground, in brushy or wooded areas. They can climb tall grasses or shrubs and wait for a potential host to brush against them. When this occurs, they seek a site for attachment.

In the absence of a vaccine, prevention of TBD is totally dependent upon your patients/parents understanding of when and where they are at risk for exposure and for us as physicians to know which pathogens can potentially be transmitted by ticks. Data regarding potential exposure risks are based on where a TBD was diagnosed, not necessarily where it was acquired. National maps that illustrate the distribution of medically significant ticks and presence or prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in specific areas within a region previously may have been incomplete or outdated. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiated a national tick surveillance program in 2017; five universities were established as regional centers of excellence to help prevent and rapidly respond to emerging vector-borne diseases across the United States. One goal is to standardize tick surveillance activities at the state level. For state-specific activity go to https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/vital-signs/index.html.

Prevention: Here are a few environmental interventions you can recommend to your patients

- Remove leaf litter, clear tall brush, and grass around the home and at edge of lawns. Mow the lawn frequently.

- Keep playground equipment, decks, and patios away from yard edges and trees.

- Live near a wooded area? Place a 3-ft.-wide barrier of gravel or wood chips between the areas.

- Put up a fence to keep unwanted animals out.

- Keep the yard free of potential hiding place for ticks (e.g., mattresses or furniture).

- Stack wood neatly and in a dry area.

- Use pesticides, but do not rely on them solely to prevent ticks exposure.

Personal interventions for patients when outdoors

- Use Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents. Note: Oil of lemon-, eucalyptus-, and para-menthane-diol–containing products should not be used in children aged3 years or less.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin to repel mosquitoes and ticks.

- Check cloths for ticks. Drying clothes on high heat for 10 minutes will kill ticks. If washing is needed use hot water. Lower temperatures will not kill ticks.

- Do daily body checks for ticks after coming indoors.

- Check pets for ticks.

Tick removal

- Take tweezers, grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull upward. Do not twist or jerk the tick. Place in a container. Ideally submit for species identification.

- After removal, clean the bite area with alcohol or soap and water.

- Never crush a tick with your fingers.

When should you include TBD in your differential for a sick child?

Headache, fever, arthralgia, and rash are symptoms for several infectious diseases. Obtaining a history of recent activities, tick bite, or travel to areas where these diseases are more prevalent is important. You must have a high index of suspicion. Clinical and laboratory clues may help.

Delay in treatment is more detrimental. If you suspect rickettsia, ehrlichiosis, or anaplasmosis, doxycycline should be started promptly regardless of age. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended.

The United States recognizes it is not adequately prepared to address the continuing rise of vector-borne diseases. In response, on Jan. 20, 2021, the CDC’s division of vector-borne diseases with input from five federal departments and the EPA developed a joint National Public Health Framework for the Prevention and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases in Humans to tackle issues including risk, detection, diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of TBD. Stay tuned.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Spring 2021 has arrived with summer quickly approaching. It is our second spring and summer during the pandemic. Travel restrictions have minimally eased for vaccinated adults. However, neither domestic nor international leisure travel is encouraged for anyone. Ironically, air travel is increasing. For many families, it is time to make decisions regarding summer activities. Outdoor activities have been encouraged throughout the pandemic, which makes it a good time to review tick-borne diseases. Depending on your location, your patients may only have to travel as far as their backyard to sustain a tick bite.

Ticks are a group of obligate, bloodsucking arthropods that feed on mammals, birds, and reptiles. There are three families of ticks. Two families, Ixodidae (hard-bodied ticks) and Argasidae (soft-bodied ticks) are responsible for transmitting the most diseases to humans in the United States. Once a tick is infected with a pathogen it usually survives and transmits it to its next host. Ticks efficiently transmit bacteria, spirochetes, protozoa, rickettsiae, nematodes, and toxins to humans during feeding when the site is exposed to infected salivary gland secretions or regurgitated midgut contents. Pathogen transmission can also occur when the feeding site is contaminated by feces or coxal fluid. Sometimes a tick can transmit multiple pathogens. Not all pathogens are infectious (e.g., tick paralysis, which occurs after exposure to a neurotoxin and red meat allergy because of alpha-gal). Ticks require a blood meal to transform to their next stage of development (larva to nymph to adult). Life cycles of hard and soft ticks differ with most hard ticks undergoing a 2-year life cycle and feeding slowly over many days. In contrast, soft ticks feed multiple times often for less than 1 hour and are capable of transmitting diseases in less than 1 minute.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever was the first recognized tick-borne disease (TBD) in humans. Since then, 18 additional pathogens transmitted by ticks have been identified with 40% being described since 1980. The increased discovery of tickborne pathogens has been attributed to physician awareness of TBD and improved diagnostics. The number of cases of TBD has risen yearly. Ticks are responsible for most vector-transmitted diseases in the United States with Lyme disease most frequently reported.

Mosquito transmission accounts for only 7% of vector-borne diseases. Three species of ticks are responsible for most human disease: Ixodes scapularis (Black-legged tick), Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), and Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick). Each is capable of transmitting agents that cause multiple diseases.

Risk for acquisition of a specific disease is dependent upon the type of tick, its geographic location, the season, and duration of the exposure.

Humans are usually incidental hosts. Tick exposure can occur year-round, but tick activity is greatest between April and September. Ticks are generally found near the ground, in brushy or wooded areas. They can climb tall grasses or shrubs and wait for a potential host to brush against them. When this occurs, they seek a site for attachment.

In the absence of a vaccine, prevention of TBD is totally dependent upon your patients/parents understanding of when and where they are at risk for exposure and for us as physicians to know which pathogens can potentially be transmitted by ticks. Data regarding potential exposure risks are based on where a TBD was diagnosed, not necessarily where it was acquired. National maps that illustrate the distribution of medically significant ticks and presence or prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in specific areas within a region previously may have been incomplete or outdated. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiated a national tick surveillance program in 2017; five universities were established as regional centers of excellence to help prevent and rapidly respond to emerging vector-borne diseases across the United States. One goal is to standardize tick surveillance activities at the state level. For state-specific activity go to https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/vital-signs/index.html.

Prevention: Here are a few environmental interventions you can recommend to your patients

- Remove leaf litter, clear tall brush, and grass around the home and at edge of lawns. Mow the lawn frequently.

- Keep playground equipment, decks, and patios away from yard edges and trees.

- Live near a wooded area? Place a 3-ft.-wide barrier of gravel or wood chips between the areas.

- Put up a fence to keep unwanted animals out.

- Keep the yard free of potential hiding place for ticks (e.g., mattresses or furniture).

- Stack wood neatly and in a dry area.

- Use pesticides, but do not rely on them solely to prevent ticks exposure.

Personal interventions for patients when outdoors

- Use Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents. Note: Oil of lemon-, eucalyptus-, and para-menthane-diol–containing products should not be used in children aged3 years or less.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin to repel mosquitoes and ticks.

- Check cloths for ticks. Drying clothes on high heat for 10 minutes will kill ticks. If washing is needed use hot water. Lower temperatures will not kill ticks.

- Do daily body checks for ticks after coming indoors.

- Check pets for ticks.

Tick removal

- Take tweezers, grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull upward. Do not twist or jerk the tick. Place in a container. Ideally submit for species identification.

- After removal, clean the bite area with alcohol or soap and water.

- Never crush a tick with your fingers.

When should you include TBD in your differential for a sick child?

Headache, fever, arthralgia, and rash are symptoms for several infectious diseases. Obtaining a history of recent activities, tick bite, or travel to areas where these diseases are more prevalent is important. You must have a high index of suspicion. Clinical and laboratory clues may help.

Delay in treatment is more detrimental. If you suspect rickettsia, ehrlichiosis, or anaplasmosis, doxycycline should be started promptly regardless of age. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended.

The United States recognizes it is not adequately prepared to address the continuing rise of vector-borne diseases. In response, on Jan. 20, 2021, the CDC’s division of vector-borne diseases with input from five federal departments and the EPA developed a joint National Public Health Framework for the Prevention and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases in Humans to tackle issues including risk, detection, diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of TBD. Stay tuned.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Spring 2021 has arrived with summer quickly approaching. It is our second spring and summer during the pandemic. Travel restrictions have minimally eased for vaccinated adults. However, neither domestic nor international leisure travel is encouraged for anyone. Ironically, air travel is increasing. For many families, it is time to make decisions regarding summer activities. Outdoor activities have been encouraged throughout the pandemic, which makes it a good time to review tick-borne diseases. Depending on your location, your patients may only have to travel as far as their backyard to sustain a tick bite.

Ticks are a group of obligate, bloodsucking arthropods that feed on mammals, birds, and reptiles. There are three families of ticks. Two families, Ixodidae (hard-bodied ticks) and Argasidae (soft-bodied ticks) are responsible for transmitting the most diseases to humans in the United States. Once a tick is infected with a pathogen it usually survives and transmits it to its next host. Ticks efficiently transmit bacteria, spirochetes, protozoa, rickettsiae, nematodes, and toxins to humans during feeding when the site is exposed to infected salivary gland secretions or regurgitated midgut contents. Pathogen transmission can also occur when the feeding site is contaminated by feces or coxal fluid. Sometimes a tick can transmit multiple pathogens. Not all pathogens are infectious (e.g., tick paralysis, which occurs after exposure to a neurotoxin and red meat allergy because of alpha-gal). Ticks require a blood meal to transform to their next stage of development (larva to nymph to adult). Life cycles of hard and soft ticks differ with most hard ticks undergoing a 2-year life cycle and feeding slowly over many days. In contrast, soft ticks feed multiple times often for less than 1 hour and are capable of transmitting diseases in less than 1 minute.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever was the first recognized tick-borne disease (TBD) in humans. Since then, 18 additional pathogens transmitted by ticks have been identified with 40% being described since 1980. The increased discovery of tickborne pathogens has been attributed to physician awareness of TBD and improved diagnostics. The number of cases of TBD has risen yearly. Ticks are responsible for most vector-transmitted diseases in the United States with Lyme disease most frequently reported.

Mosquito transmission accounts for only 7% of vector-borne diseases. Three species of ticks are responsible for most human disease: Ixodes scapularis (Black-legged tick), Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), and Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick). Each is capable of transmitting agents that cause multiple diseases.

Risk for acquisition of a specific disease is dependent upon the type of tick, its geographic location, the season, and duration of the exposure.

Humans are usually incidental hosts. Tick exposure can occur year-round, but tick activity is greatest between April and September. Ticks are generally found near the ground, in brushy or wooded areas. They can climb tall grasses or shrubs and wait for a potential host to brush against them. When this occurs, they seek a site for attachment.

In the absence of a vaccine, prevention of TBD is totally dependent upon your patients/parents understanding of when and where they are at risk for exposure and for us as physicians to know which pathogens can potentially be transmitted by ticks. Data regarding potential exposure risks are based on where a TBD was diagnosed, not necessarily where it was acquired. National maps that illustrate the distribution of medically significant ticks and presence or prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in specific areas within a region previously may have been incomplete or outdated. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiated a national tick surveillance program in 2017; five universities were established as regional centers of excellence to help prevent and rapidly respond to emerging vector-borne diseases across the United States. One goal is to standardize tick surveillance activities at the state level. For state-specific activity go to https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/vital-signs/index.html.

Prevention: Here are a few environmental interventions you can recommend to your patients

- Remove leaf litter, clear tall brush, and grass around the home and at edge of lawns. Mow the lawn frequently.

- Keep playground equipment, decks, and patios away from yard edges and trees.

- Live near a wooded area? Place a 3-ft.-wide barrier of gravel or wood chips between the areas.

- Put up a fence to keep unwanted animals out.

- Keep the yard free of potential hiding place for ticks (e.g., mattresses or furniture).

- Stack wood neatly and in a dry area.

- Use pesticides, but do not rely on them solely to prevent ticks exposure.

Personal interventions for patients when outdoors

- Use Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents. Note: Oil of lemon-, eucalyptus-, and para-menthane-diol–containing products should not be used in children aged3 years or less.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin to repel mosquitoes and ticks.

- Check cloths for ticks. Drying clothes on high heat for 10 minutes will kill ticks. If washing is needed use hot water. Lower temperatures will not kill ticks.

- Do daily body checks for ticks after coming indoors.

- Check pets for ticks.

Tick removal

- Take tweezers, grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull upward. Do not twist or jerk the tick. Place in a container. Ideally submit for species identification.

- After removal, clean the bite area with alcohol or soap and water.

- Never crush a tick with your fingers.

When should you include TBD in your differential for a sick child?

Headache, fever, arthralgia, and rash are symptoms for several infectious diseases. Obtaining a history of recent activities, tick bite, or travel to areas where these diseases are more prevalent is important. You must have a high index of suspicion. Clinical and laboratory clues may help.

Delay in treatment is more detrimental. If you suspect rickettsia, ehrlichiosis, or anaplasmosis, doxycycline should be started promptly regardless of age. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended.

The United States recognizes it is not adequately prepared to address the continuing rise of vector-borne diseases. In response, on Jan. 20, 2021, the CDC’s division of vector-borne diseases with input from five federal departments and the EPA developed a joint National Public Health Framework for the Prevention and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases in Humans to tackle issues including risk, detection, diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of TBD. Stay tuned.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.