User login

My wife and I have traveled a number of times as far east as Kyrgyzstan and as far south as Paraguay to participate in short 1- to 2-week medical clinics. When I participated in a week-long medical clinic in Haiti in early 2017, the CEO of the hosting U.S. organization asked, “I wonder if we are doing any good here?” His organization had been to Onaville, Haiti for the last 4-5 years.

So my wife Stacy, a retired licensed practical nurse, and I, a general pediatrician with an interest in severe acute malnutrition, went on a 3-month medical sabbatical to Onaville. We were self-funded, with the exception of our home church in Senoia, Ga., paying the cost of our lodging during that time.

Prior to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the government planned Onaville to be a retirement community area, with a population of only about 1,500, I was told. After the devastating temblor, it became one of several areas where the government sent people displaced from Port-au-Prince. The population today is possibly 250,000 or more.

The poverty in this area has “newer” flavor than areas such as Cité Soleil, which has been there for decades. What we found in Onaville – and probably all of Haiti – is an appalling lack of understanding and appreciation about the nature of malnutrition.

Methods and materials for study

The 1981 World Health Organization’s last printed monograph about severe acute nutrition remains essentially today’s cookbook recipe for treatment. Little seems to have changed since then in the literature I’ve reviewed. It didn’t take long after we started seeing the children in Onaville to shift that interest to something much more serious and widespread.

I wanted to start with basic health assessments in the Onaville children around 5 years and under. These children rarely see a physician, and only about half or so get any vaccine. Most parents do not have any immunization records in their possession to even review.

We decided to measure head size, mid-upper arm circumference, height, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Date of birth was recorded, if known or could at best be closely estimated. Vaccination was recorded as a yes or no response. All children also were examined for evidence of things like swelling, marasmic appearance (wasting, loss of body fat and muscle), yellowed hair, eye findings of vitamin A deficiency, etc. I wanted to get some impression about the health of these children in the same way that most mobile medical clinics do in Haiti.

Being a database programmer since I bought my first computer in 1985, and having written and deployed my office’s current EMR system in 2000, I decided before ever arriving in Haiti to write the software needed for this task. Unlike regular office EMRs, there were some special considerations.

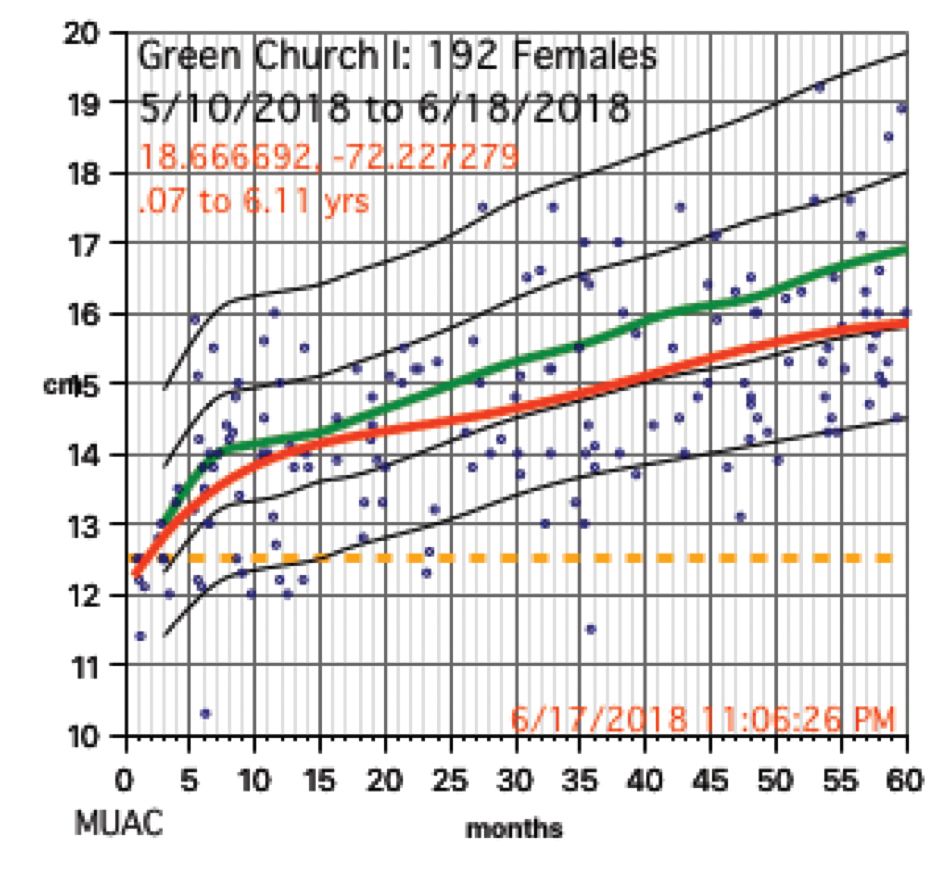

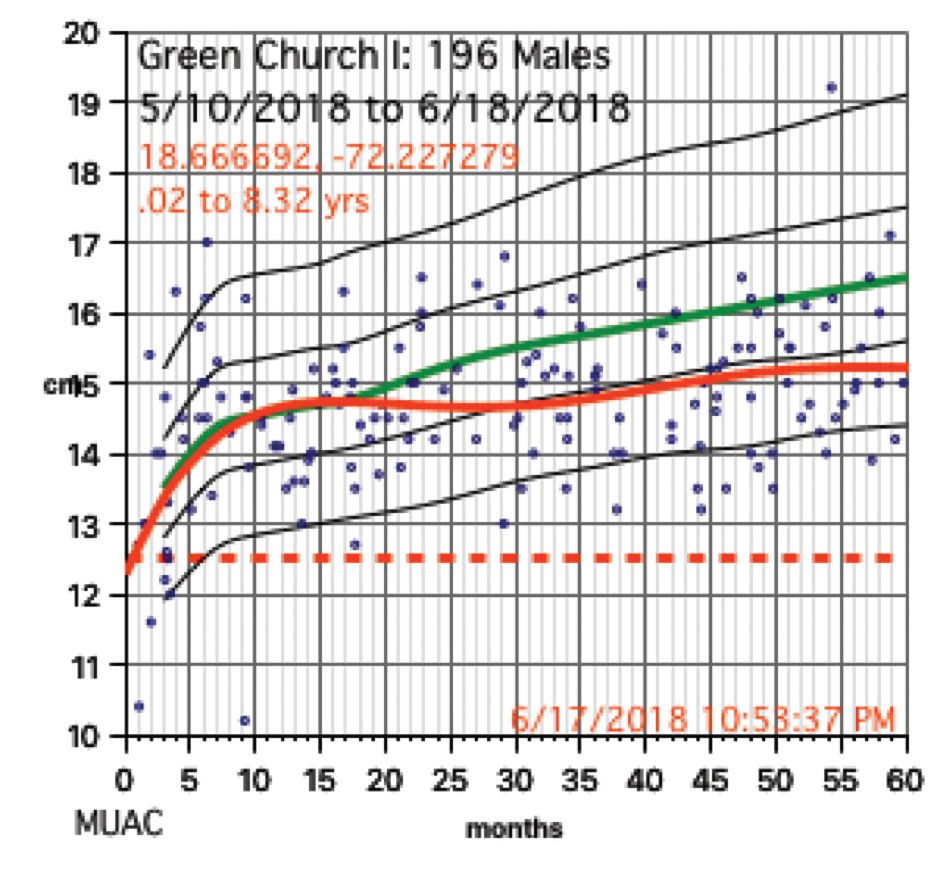

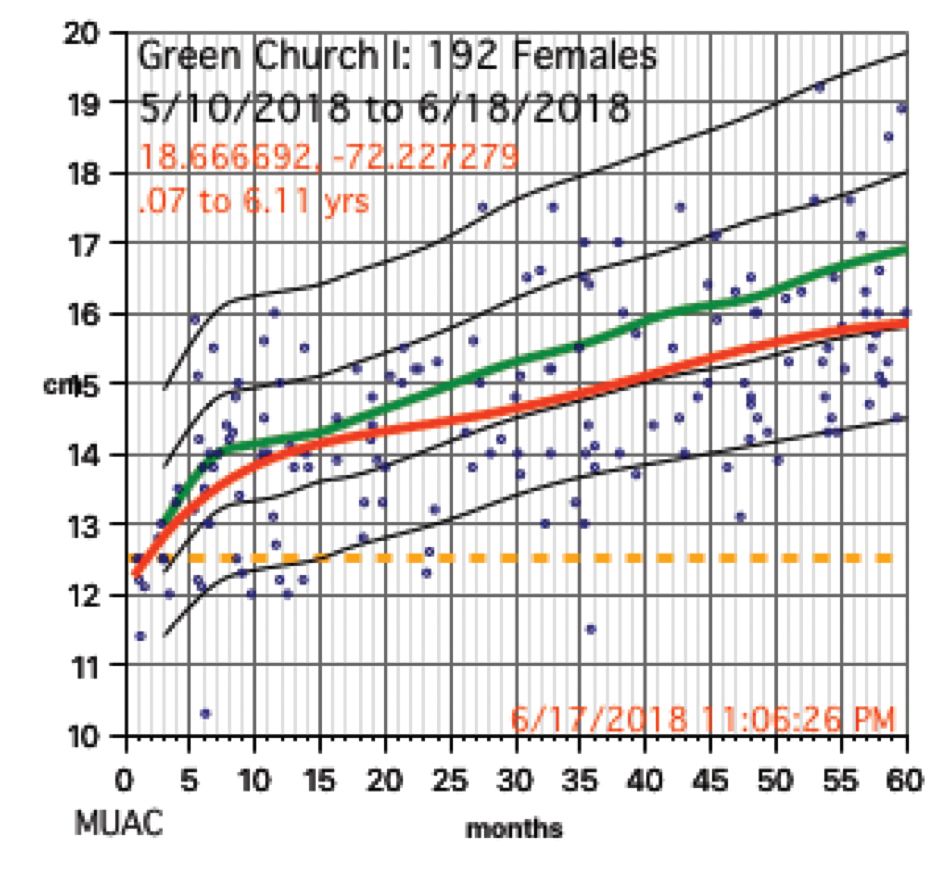

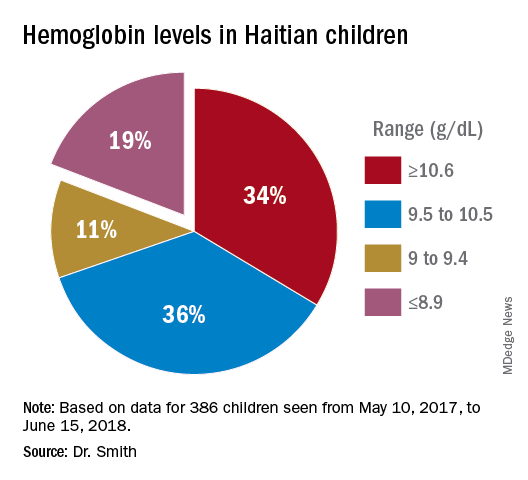

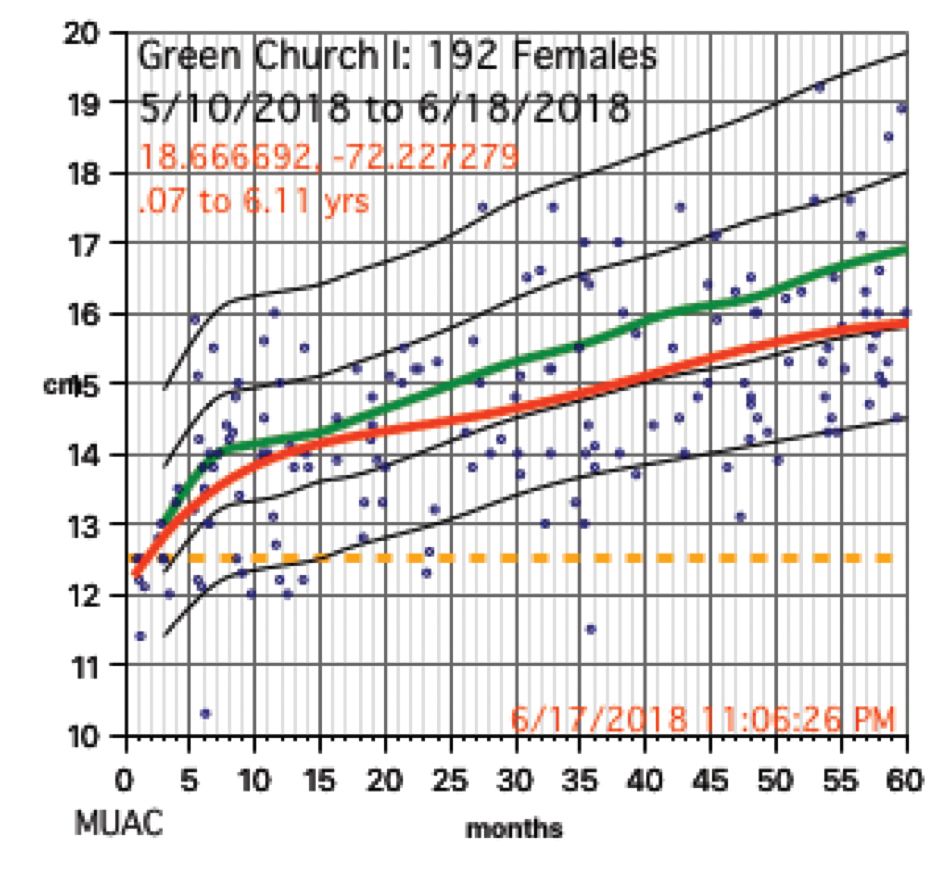

Growth charts needed not only to be generated for individuals, but in aggregate. Hemoglobins levels, too, needed charting. While in the United States, I use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart data, but for Haiti I used WHO growth data. I was able to procure hemoglobin charting data as well. Aggregate data turned out to be key to our conclusions.

We used a regular consumer quality digital bathroom scale for weights. A sewing tape attached with duct tape to a wall or pillar was used to measure height. Standard head circumference tapes were use to measure heads and arms.

The hemoglobin was measured with a HemoCue Hb 201+ instrument. Size, ruggedness, and cost dictated all our choices because, except for food, we had to carry everything with us. The cost of a new HemoCue was under $400 and each microcuvette test was about $1.50.

Severe anemia

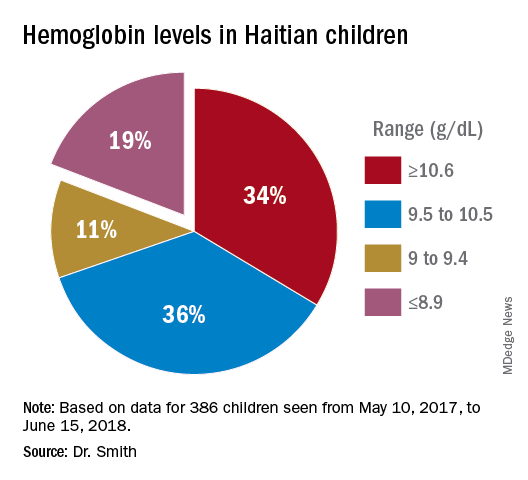

In total, we saw about 386 children, mostly 5 years and under, in Onaville. Toward the end of the 3 months, we were seeing some of those back as follow-ups. One of the first hemoglobins was 4.9 g/dL, with a 5.4 g/dL on repeat. This stunned us. In the first few days, we were seeing what we saw consistently throughout the course of 3 months.

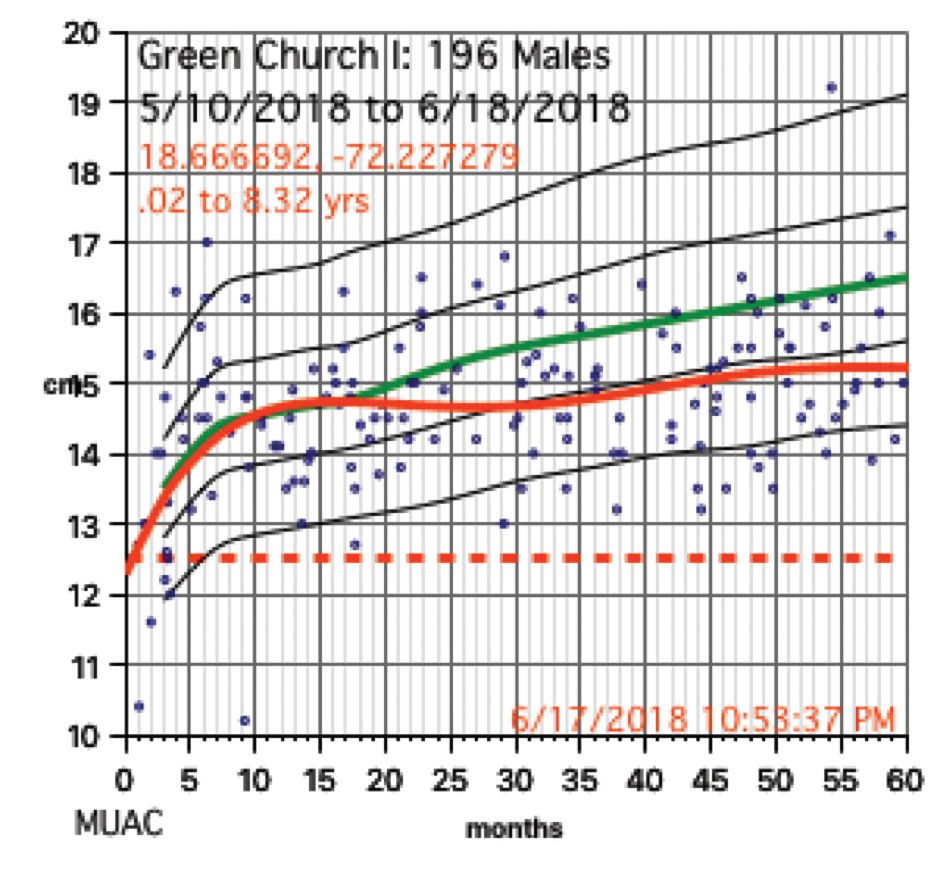

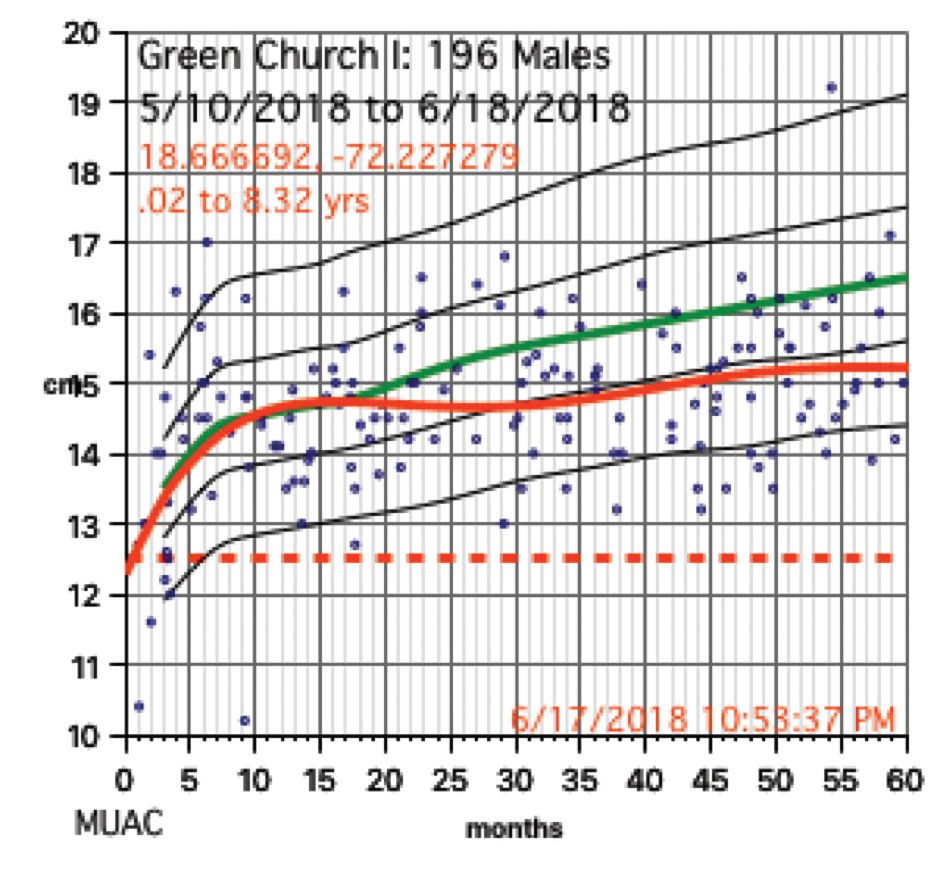

About 19% of these children had hemoglobins from below 9.0 g/dL to below 6 g/dL. More importantly, there was little on physical exam that would trigger one to do a hemoglobin. Low hemoglobins were not associated with yellow-orange hair. No cases of the swelling of kwashiorkor or pencil-like frames of marasmus were seen.

Severe chronic malnutrition

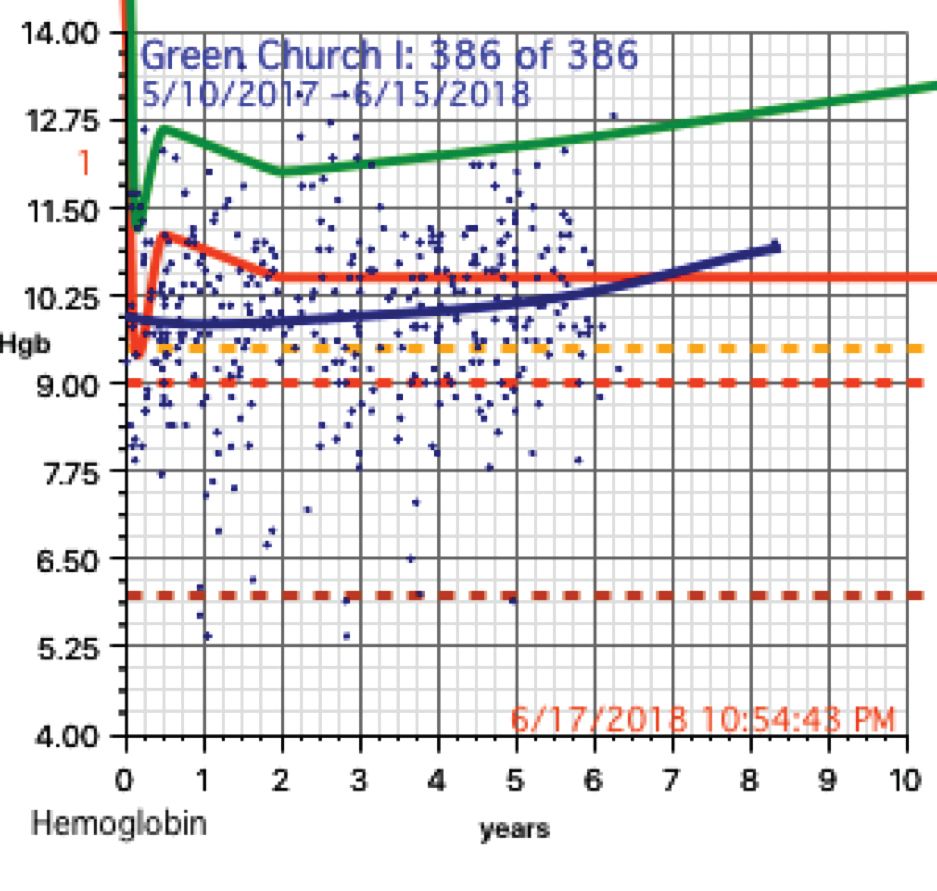

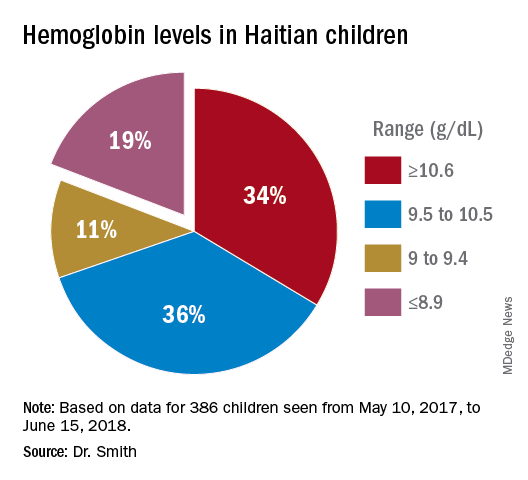

The scatter charts are very telling and the hemoglobin graphs are explosive. What is demonstrated is that this recent population is slowly starving to death. How can the hemoglobins be so very low in comparison to the only slightly lowered mean averages (the solid red line)?

In over 3 decades of pediatric medicine, I rarely have seen children in the United States with hemoglobins below 9.5 g/dL. Often they have other illnesses that clearly point to the cause. Could the 19% of children with severely lowered hemoglobins (below 9.0 g/dL) be caused by sickle cell disease or something else in these Haitian children?

A search for articles where sickle cell was studied revealed a study done at St. Damien Pediatrics Hospital in Port-au-Prince (Blood. 2012;120:4235). The overall incidence of sickle cell disease was this: “Of the 2,258 samples tested, 247 had HbS, fifty-seven had HbC, ten had HbSS, and three had HbSC.” Only 0.57% of these children had sickle or sickle-C disease where one could expect hemoglobins to be as low as in the children of Onaville. Applying that percentage to the 386 children we saw would account for about only 2 children who might have sickling anemia. Yet we had 73 children in our study with severely lowered hemoglobins below 9.0 g/dL. If you estimate that half of the 250,000 people in Onaville are children, that extrapolates to over 47,000 with severe anemia! I think that a study larger than ours needs to be done to better assess that, however.

My best thought is that these children who have little external evidence of abnormality and mildly lowered growth data represent a type of malnutrition that has not been defined, much less addressed. I call this severe chronic malnutrition. The very low hemoglobins indicate to me that this is not simply a lack of iron – although certainly that is a factor – but rather that these children are in a state of chronic protein deprivation. They represent a large pool of children who exist between those with normal nutritional states and those with the kwashiorkor or marasmus of severe acute malnutrition.

A search of the 69,823 ICD-10 codes in my database for “malnutrition” only turns up the ill-defined terms, “Unspecified severe protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Moderate, and Mild protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Unspecified protein-calorie malnutrition,” and “Sequelae of protein-calorie malnutrition.” Whatever each of those means is purely subjective in my opinion.

Without a clear understanding or definition of what is severe chronic malnutrition, we are like the Titanic trying to avoid icebergs on a moonless night. I think we must define severe chronic malnutrition before we really can understand the pathophysiology and treatment of severe acute malnutrition.

The WHO published its last printed monograph, “The treatment and management of severe acute protein-energy malnutrition,” in 1981. This publication is essentially a cookbook approach for what to do, with no clear presentation of the chemical processes and medicine involved. The primary focus for the WHO is mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height. Reading this document might lead one to believe that all malnutrition is acutely severe. It is most certainly not.

Conclusion

The answer to why some children show the swelling of kwashiorkor and some show marasmus probably will not be found in the study of severe acute malnutrition or refeeding syndrome alone. We must go far beyond the WHO’s cookbook recipe.

I think we must start with the study, definition, and treatment of severe chronic malnutrition.

While in Haiti, we shared these data with three organization that are working to provide nutrition in a starving nation. Together, the Baptist Haiti Mission, Mission of Hope Haiti, and Trinity Hope may well be supplying 175,000 meals a day through school lunches and other avenues throughout the country. Their response was telling. Those at Baptist Haiti Mission, an organization with a presence of almost 80 years there, told us that this information was a “big deal.”

The issue for them is the answer to the question, “How can we tell if we are doing any good in our feeding programs?” A lot of money is being thrown into nutrition without tangible ways to assess impact. Clearly parameters such as mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height that WHO advocates is not adequate, as our plots revealed.

We think that a simple, cheap, hemoglobin finger stick can tell us who is falling through the cracks into severe chronic malnutrition and those at risk for severe acute malnutrition. I am an advocate for instituting hemoglobin surveillance as part of all feeding programs. Then we can come up with the cheapest and most effective in-country mechanisms to treat these children.

Indeed that is our next step in working in Haiti.

Dr. Smith is a board certified pediatrician working in McDonough, Ga., with an interest in malnutrition among the children of Haiti. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

My wife and I have traveled a number of times as far east as Kyrgyzstan and as far south as Paraguay to participate in short 1- to 2-week medical clinics. When I participated in a week-long medical clinic in Haiti in early 2017, the CEO of the hosting U.S. organization asked, “I wonder if we are doing any good here?” His organization had been to Onaville, Haiti for the last 4-5 years.

So my wife Stacy, a retired licensed practical nurse, and I, a general pediatrician with an interest in severe acute malnutrition, went on a 3-month medical sabbatical to Onaville. We were self-funded, with the exception of our home church in Senoia, Ga., paying the cost of our lodging during that time.

Prior to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the government planned Onaville to be a retirement community area, with a population of only about 1,500, I was told. After the devastating temblor, it became one of several areas where the government sent people displaced from Port-au-Prince. The population today is possibly 250,000 or more.

The poverty in this area has “newer” flavor than areas such as Cité Soleil, which has been there for decades. What we found in Onaville – and probably all of Haiti – is an appalling lack of understanding and appreciation about the nature of malnutrition.

Methods and materials for study

The 1981 World Health Organization’s last printed monograph about severe acute nutrition remains essentially today’s cookbook recipe for treatment. Little seems to have changed since then in the literature I’ve reviewed. It didn’t take long after we started seeing the children in Onaville to shift that interest to something much more serious and widespread.

I wanted to start with basic health assessments in the Onaville children around 5 years and under. These children rarely see a physician, and only about half or so get any vaccine. Most parents do not have any immunization records in their possession to even review.

We decided to measure head size, mid-upper arm circumference, height, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Date of birth was recorded, if known or could at best be closely estimated. Vaccination was recorded as a yes or no response. All children also were examined for evidence of things like swelling, marasmic appearance (wasting, loss of body fat and muscle), yellowed hair, eye findings of vitamin A deficiency, etc. I wanted to get some impression about the health of these children in the same way that most mobile medical clinics do in Haiti.

Being a database programmer since I bought my first computer in 1985, and having written and deployed my office’s current EMR system in 2000, I decided before ever arriving in Haiti to write the software needed for this task. Unlike regular office EMRs, there were some special considerations.

Growth charts needed not only to be generated for individuals, but in aggregate. Hemoglobins levels, too, needed charting. While in the United States, I use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart data, but for Haiti I used WHO growth data. I was able to procure hemoglobin charting data as well. Aggregate data turned out to be key to our conclusions.

We used a regular consumer quality digital bathroom scale for weights. A sewing tape attached with duct tape to a wall or pillar was used to measure height. Standard head circumference tapes were use to measure heads and arms.

The hemoglobin was measured with a HemoCue Hb 201+ instrument. Size, ruggedness, and cost dictated all our choices because, except for food, we had to carry everything with us. The cost of a new HemoCue was under $400 and each microcuvette test was about $1.50.

Severe anemia

In total, we saw about 386 children, mostly 5 years and under, in Onaville. Toward the end of the 3 months, we were seeing some of those back as follow-ups. One of the first hemoglobins was 4.9 g/dL, with a 5.4 g/dL on repeat. This stunned us. In the first few days, we were seeing what we saw consistently throughout the course of 3 months.

About 19% of these children had hemoglobins from below 9.0 g/dL to below 6 g/dL. More importantly, there was little on physical exam that would trigger one to do a hemoglobin. Low hemoglobins were not associated with yellow-orange hair. No cases of the swelling of kwashiorkor or pencil-like frames of marasmus were seen.

Severe chronic malnutrition

The scatter charts are very telling and the hemoglobin graphs are explosive. What is demonstrated is that this recent population is slowly starving to death. How can the hemoglobins be so very low in comparison to the only slightly lowered mean averages (the solid red line)?

In over 3 decades of pediatric medicine, I rarely have seen children in the United States with hemoglobins below 9.5 g/dL. Often they have other illnesses that clearly point to the cause. Could the 19% of children with severely lowered hemoglobins (below 9.0 g/dL) be caused by sickle cell disease or something else in these Haitian children?

A search for articles where sickle cell was studied revealed a study done at St. Damien Pediatrics Hospital in Port-au-Prince (Blood. 2012;120:4235). The overall incidence of sickle cell disease was this: “Of the 2,258 samples tested, 247 had HbS, fifty-seven had HbC, ten had HbSS, and three had HbSC.” Only 0.57% of these children had sickle or sickle-C disease where one could expect hemoglobins to be as low as in the children of Onaville. Applying that percentage to the 386 children we saw would account for about only 2 children who might have sickling anemia. Yet we had 73 children in our study with severely lowered hemoglobins below 9.0 g/dL. If you estimate that half of the 250,000 people in Onaville are children, that extrapolates to over 47,000 with severe anemia! I think that a study larger than ours needs to be done to better assess that, however.

My best thought is that these children who have little external evidence of abnormality and mildly lowered growth data represent a type of malnutrition that has not been defined, much less addressed. I call this severe chronic malnutrition. The very low hemoglobins indicate to me that this is not simply a lack of iron – although certainly that is a factor – but rather that these children are in a state of chronic protein deprivation. They represent a large pool of children who exist between those with normal nutritional states and those with the kwashiorkor or marasmus of severe acute malnutrition.

A search of the 69,823 ICD-10 codes in my database for “malnutrition” only turns up the ill-defined terms, “Unspecified severe protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Moderate, and Mild protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Unspecified protein-calorie malnutrition,” and “Sequelae of protein-calorie malnutrition.” Whatever each of those means is purely subjective in my opinion.

Without a clear understanding or definition of what is severe chronic malnutrition, we are like the Titanic trying to avoid icebergs on a moonless night. I think we must define severe chronic malnutrition before we really can understand the pathophysiology and treatment of severe acute malnutrition.

The WHO published its last printed monograph, “The treatment and management of severe acute protein-energy malnutrition,” in 1981. This publication is essentially a cookbook approach for what to do, with no clear presentation of the chemical processes and medicine involved. The primary focus for the WHO is mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height. Reading this document might lead one to believe that all malnutrition is acutely severe. It is most certainly not.

Conclusion

The answer to why some children show the swelling of kwashiorkor and some show marasmus probably will not be found in the study of severe acute malnutrition or refeeding syndrome alone. We must go far beyond the WHO’s cookbook recipe.

I think we must start with the study, definition, and treatment of severe chronic malnutrition.

While in Haiti, we shared these data with three organization that are working to provide nutrition in a starving nation. Together, the Baptist Haiti Mission, Mission of Hope Haiti, and Trinity Hope may well be supplying 175,000 meals a day through school lunches and other avenues throughout the country. Their response was telling. Those at Baptist Haiti Mission, an organization with a presence of almost 80 years there, told us that this information was a “big deal.”

The issue for them is the answer to the question, “How can we tell if we are doing any good in our feeding programs?” A lot of money is being thrown into nutrition without tangible ways to assess impact. Clearly parameters such as mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height that WHO advocates is not adequate, as our plots revealed.

We think that a simple, cheap, hemoglobin finger stick can tell us who is falling through the cracks into severe chronic malnutrition and those at risk for severe acute malnutrition. I am an advocate for instituting hemoglobin surveillance as part of all feeding programs. Then we can come up with the cheapest and most effective in-country mechanisms to treat these children.

Indeed that is our next step in working in Haiti.

Dr. Smith is a board certified pediatrician working in McDonough, Ga., with an interest in malnutrition among the children of Haiti. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

My wife and I have traveled a number of times as far east as Kyrgyzstan and as far south as Paraguay to participate in short 1- to 2-week medical clinics. When I participated in a week-long medical clinic in Haiti in early 2017, the CEO of the hosting U.S. organization asked, “I wonder if we are doing any good here?” His organization had been to Onaville, Haiti for the last 4-5 years.

So my wife Stacy, a retired licensed practical nurse, and I, a general pediatrician with an interest in severe acute malnutrition, went on a 3-month medical sabbatical to Onaville. We were self-funded, with the exception of our home church in Senoia, Ga., paying the cost of our lodging during that time.

Prior to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the government planned Onaville to be a retirement community area, with a population of only about 1,500, I was told. After the devastating temblor, it became one of several areas where the government sent people displaced from Port-au-Prince. The population today is possibly 250,000 or more.

The poverty in this area has “newer” flavor than areas such as Cité Soleil, which has been there for decades. What we found in Onaville – and probably all of Haiti – is an appalling lack of understanding and appreciation about the nature of malnutrition.

Methods and materials for study

The 1981 World Health Organization’s last printed monograph about severe acute nutrition remains essentially today’s cookbook recipe for treatment. Little seems to have changed since then in the literature I’ve reviewed. It didn’t take long after we started seeing the children in Onaville to shift that interest to something much more serious and widespread.

I wanted to start with basic health assessments in the Onaville children around 5 years and under. These children rarely see a physician, and only about half or so get any vaccine. Most parents do not have any immunization records in their possession to even review.

We decided to measure head size, mid-upper arm circumference, height, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Date of birth was recorded, if known or could at best be closely estimated. Vaccination was recorded as a yes or no response. All children also were examined for evidence of things like swelling, marasmic appearance (wasting, loss of body fat and muscle), yellowed hair, eye findings of vitamin A deficiency, etc. I wanted to get some impression about the health of these children in the same way that most mobile medical clinics do in Haiti.

Being a database programmer since I bought my first computer in 1985, and having written and deployed my office’s current EMR system in 2000, I decided before ever arriving in Haiti to write the software needed for this task. Unlike regular office EMRs, there were some special considerations.

Growth charts needed not only to be generated for individuals, but in aggregate. Hemoglobins levels, too, needed charting. While in the United States, I use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart data, but for Haiti I used WHO growth data. I was able to procure hemoglobin charting data as well. Aggregate data turned out to be key to our conclusions.

We used a regular consumer quality digital bathroom scale for weights. A sewing tape attached with duct tape to a wall or pillar was used to measure height. Standard head circumference tapes were use to measure heads and arms.

The hemoglobin was measured with a HemoCue Hb 201+ instrument. Size, ruggedness, and cost dictated all our choices because, except for food, we had to carry everything with us. The cost of a new HemoCue was under $400 and each microcuvette test was about $1.50.

Severe anemia

In total, we saw about 386 children, mostly 5 years and under, in Onaville. Toward the end of the 3 months, we were seeing some of those back as follow-ups. One of the first hemoglobins was 4.9 g/dL, with a 5.4 g/dL on repeat. This stunned us. In the first few days, we were seeing what we saw consistently throughout the course of 3 months.

About 19% of these children had hemoglobins from below 9.0 g/dL to below 6 g/dL. More importantly, there was little on physical exam that would trigger one to do a hemoglobin. Low hemoglobins were not associated with yellow-orange hair. No cases of the swelling of kwashiorkor or pencil-like frames of marasmus were seen.

Severe chronic malnutrition

The scatter charts are very telling and the hemoglobin graphs are explosive. What is demonstrated is that this recent population is slowly starving to death. How can the hemoglobins be so very low in comparison to the only slightly lowered mean averages (the solid red line)?

In over 3 decades of pediatric medicine, I rarely have seen children in the United States with hemoglobins below 9.5 g/dL. Often they have other illnesses that clearly point to the cause. Could the 19% of children with severely lowered hemoglobins (below 9.0 g/dL) be caused by sickle cell disease or something else in these Haitian children?

A search for articles where sickle cell was studied revealed a study done at St. Damien Pediatrics Hospital in Port-au-Prince (Blood. 2012;120:4235). The overall incidence of sickle cell disease was this: “Of the 2,258 samples tested, 247 had HbS, fifty-seven had HbC, ten had HbSS, and three had HbSC.” Only 0.57% of these children had sickle or sickle-C disease where one could expect hemoglobins to be as low as in the children of Onaville. Applying that percentage to the 386 children we saw would account for about only 2 children who might have sickling anemia. Yet we had 73 children in our study with severely lowered hemoglobins below 9.0 g/dL. If you estimate that half of the 250,000 people in Onaville are children, that extrapolates to over 47,000 with severe anemia! I think that a study larger than ours needs to be done to better assess that, however.

My best thought is that these children who have little external evidence of abnormality and mildly lowered growth data represent a type of malnutrition that has not been defined, much less addressed. I call this severe chronic malnutrition. The very low hemoglobins indicate to me that this is not simply a lack of iron – although certainly that is a factor – but rather that these children are in a state of chronic protein deprivation. They represent a large pool of children who exist between those with normal nutritional states and those with the kwashiorkor or marasmus of severe acute malnutrition.

A search of the 69,823 ICD-10 codes in my database for “malnutrition” only turns up the ill-defined terms, “Unspecified severe protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Moderate, and Mild protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Unspecified protein-calorie malnutrition,” and “Sequelae of protein-calorie malnutrition.” Whatever each of those means is purely subjective in my opinion.

Without a clear understanding or definition of what is severe chronic malnutrition, we are like the Titanic trying to avoid icebergs on a moonless night. I think we must define severe chronic malnutrition before we really can understand the pathophysiology and treatment of severe acute malnutrition.

The WHO published its last printed monograph, “The treatment and management of severe acute protein-energy malnutrition,” in 1981. This publication is essentially a cookbook approach for what to do, with no clear presentation of the chemical processes and medicine involved. The primary focus for the WHO is mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height. Reading this document might lead one to believe that all malnutrition is acutely severe. It is most certainly not.

Conclusion

The answer to why some children show the swelling of kwashiorkor and some show marasmus probably will not be found in the study of severe acute malnutrition or refeeding syndrome alone. We must go far beyond the WHO’s cookbook recipe.

I think we must start with the study, definition, and treatment of severe chronic malnutrition.

While in Haiti, we shared these data with three organization that are working to provide nutrition in a starving nation. Together, the Baptist Haiti Mission, Mission of Hope Haiti, and Trinity Hope may well be supplying 175,000 meals a day through school lunches and other avenues throughout the country. Their response was telling. Those at Baptist Haiti Mission, an organization with a presence of almost 80 years there, told us that this information was a “big deal.”

The issue for them is the answer to the question, “How can we tell if we are doing any good in our feeding programs?” A lot of money is being thrown into nutrition without tangible ways to assess impact. Clearly parameters such as mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height that WHO advocates is not adequate, as our plots revealed.

We think that a simple, cheap, hemoglobin finger stick can tell us who is falling through the cracks into severe chronic malnutrition and those at risk for severe acute malnutrition. I am an advocate for instituting hemoglobin surveillance as part of all feeding programs. Then we can come up with the cheapest and most effective in-country mechanisms to treat these children.

Indeed that is our next step in working in Haiti.

Dr. Smith is a board certified pediatrician working in McDonough, Ga., with an interest in malnutrition among the children of Haiti. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.