User login

Since the first liver transplant (LT) was performed in 1963 by Starzl et al, there have been considerable advances in the field, with improvements in post-transplant survival.1 There are multiple indications for LT, including acute liver failure and index complications of cirrhosis such as ascites, encephalopathy, and hepatopulmonary syndrome.2 Once a patient develops one of these conditions, he/she is evaluated for LT, even as the complications of liver failure are being managed.

Although the number of LTs has risen, the demand for transplant continues to exceed availability. In 2015, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis was the 12th leading cause of death in the United States.3 In 2016, approximately 50% of waitlisted candidates received a transplant.4 There is also a donor shortage. In part, this shortage may be due to longer life spans and the subsequent increase in the age of the potential donor.5 In light of this shortage and increased demand, the pre-LT workup is comprehensive. The pre-transplant assessment typically consists of cardiology, surgery, hepatology, and psychosocial evaluations, and hence requires a team of experts to determine who is an ideal candidate for transplant.

Psychiatrists play a key role in the pre-transplant psychosocial evaluations. This article describes the elements of these evaluations, and what psychiatrists can do to help patients both before and after they undergo LT.

Elements of the pre-transplant evaluation

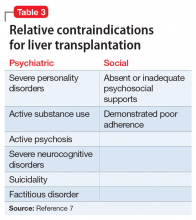

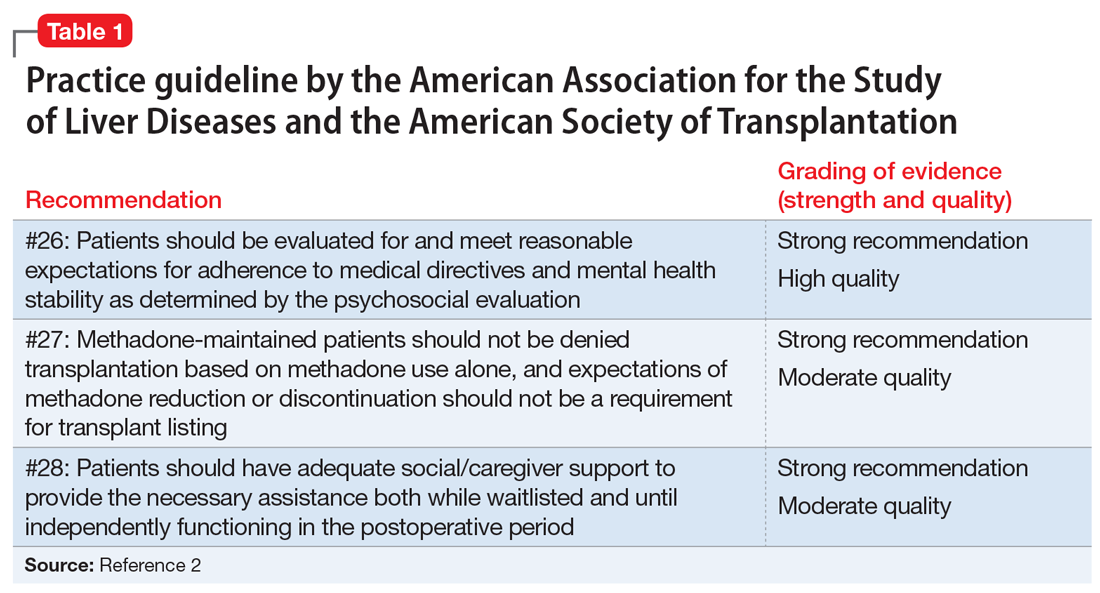

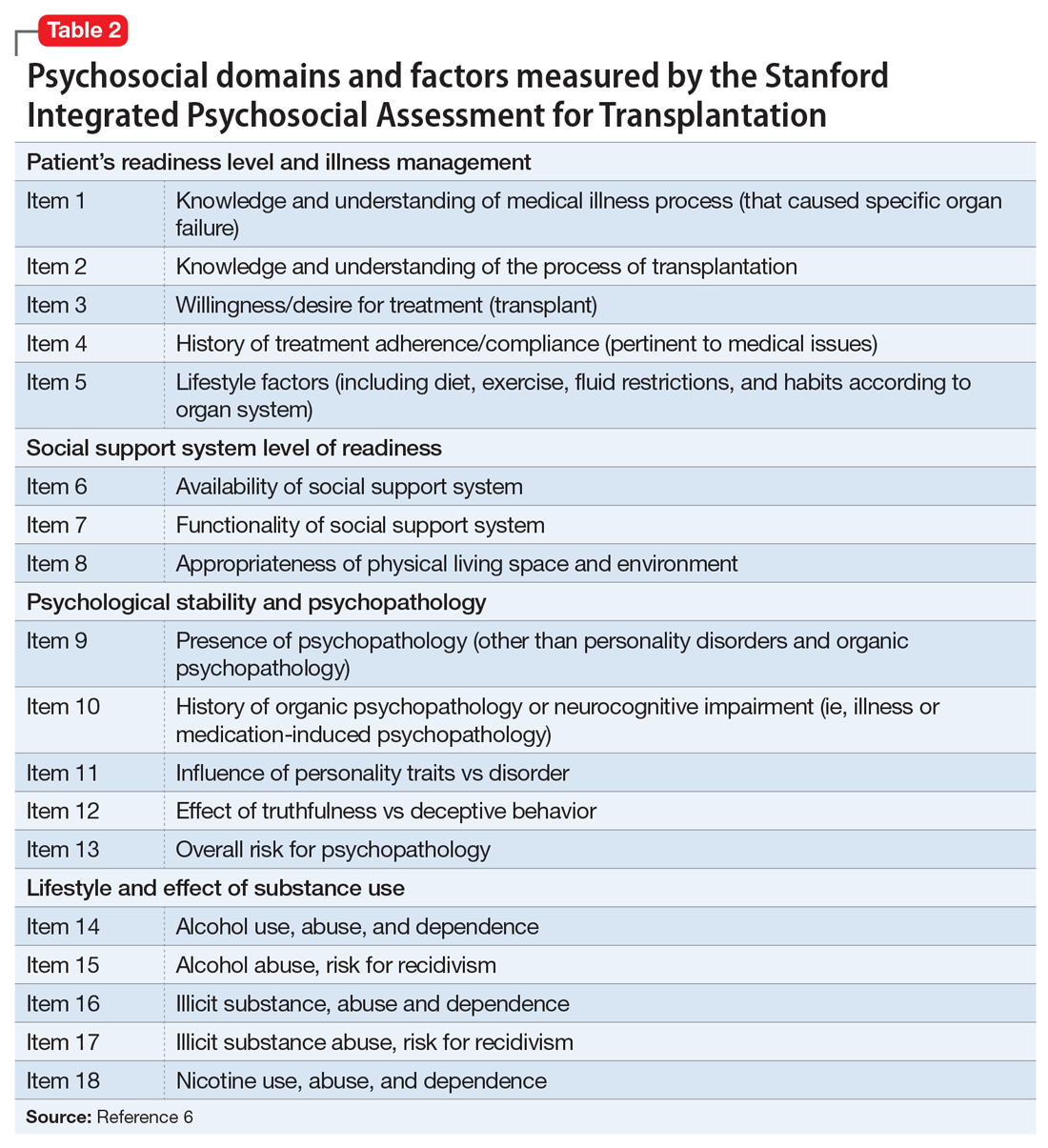

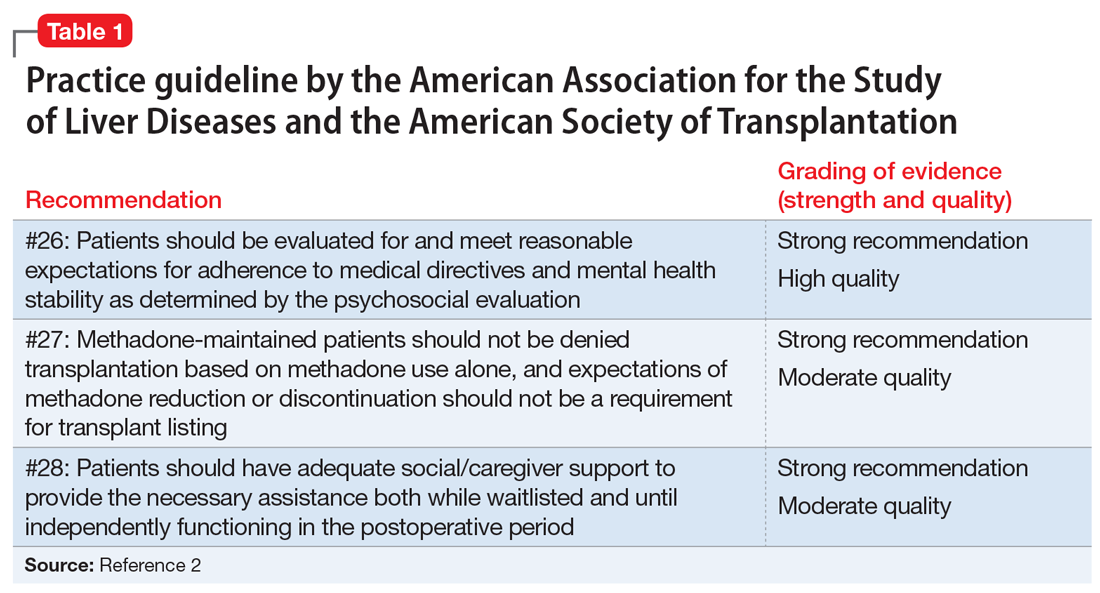

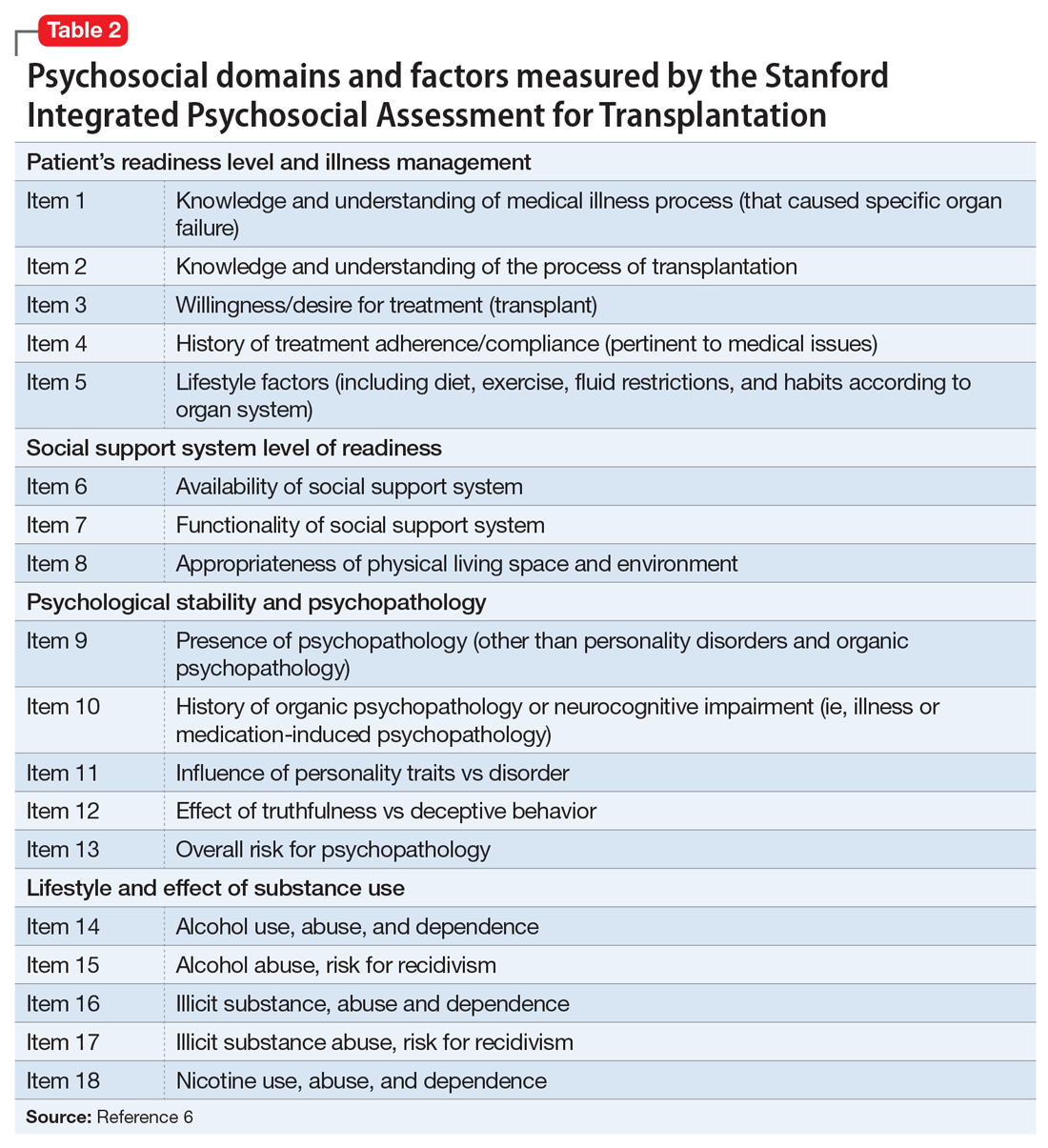

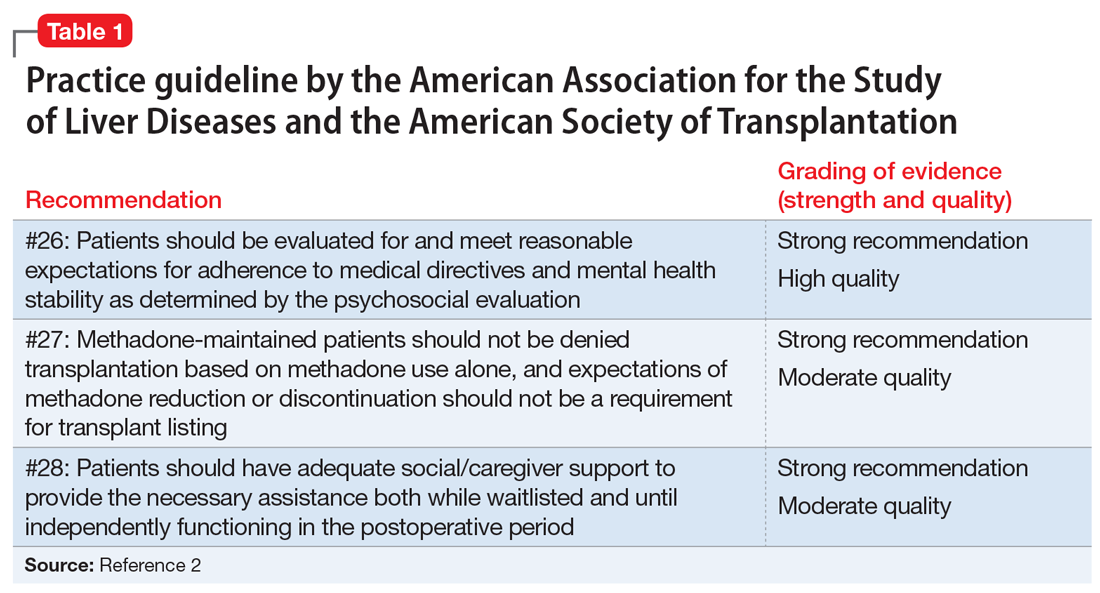

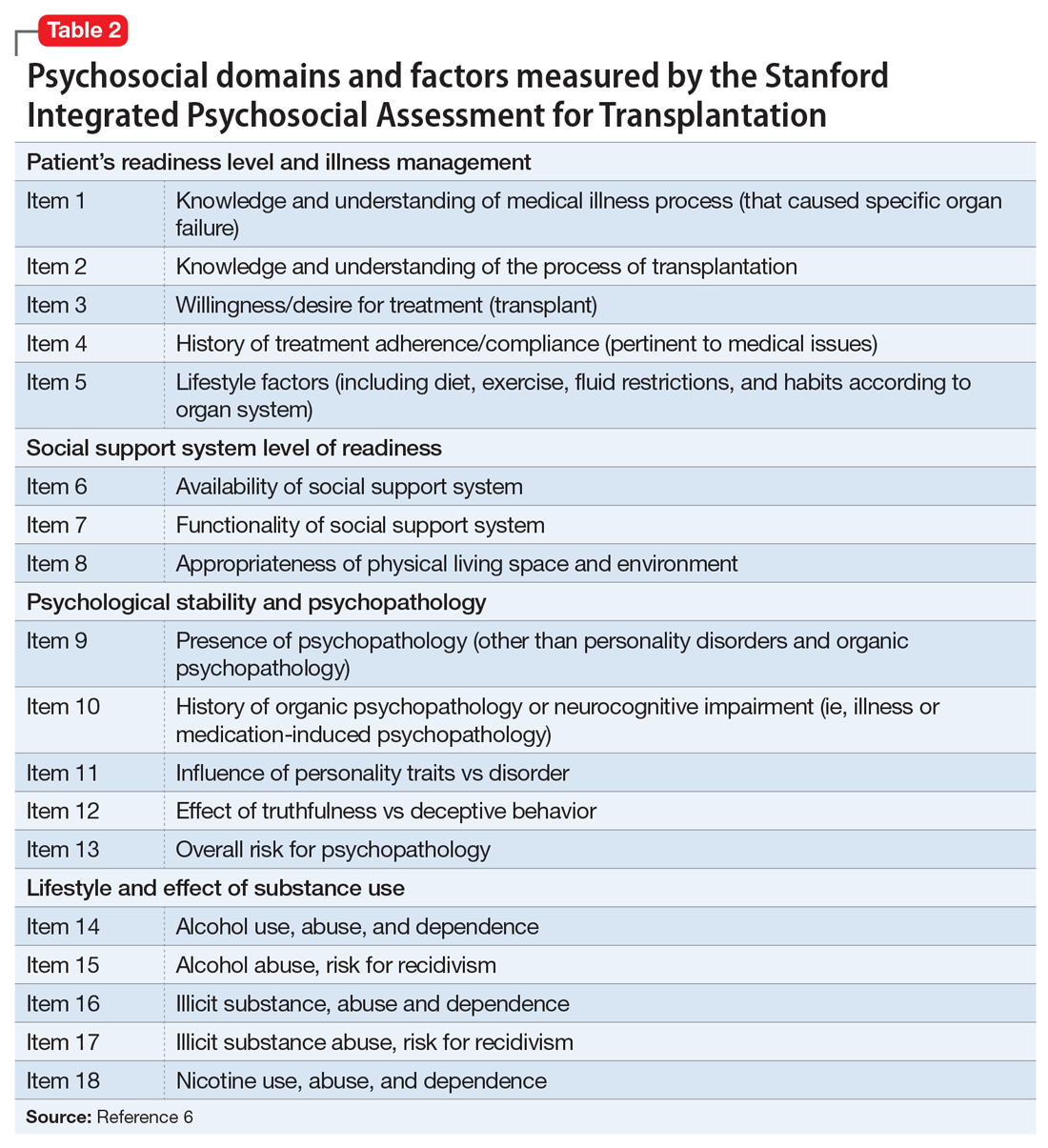

The psychosocial evaluation is a critical component of the pre-transplant assessment. As part of the evaluation, patients are screened for psychosocial limitations that may complicate transplantation, such as demonstrated noncompliance, ongoing alcohol or drug use, and lack of social support (Table 12 ). Other goals of the psychosocial evaluation are to identify in the pre-transplant period patients with possible risk factors, such as substance use or psychiatric disorders, and develop treatment plans to optimize transplant outcomes (Table 26). There are relative contraindications to LT (Table 37) but no absolute psychiatric contraindications, according to the 2013 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) practice guideline for transplantation.2

Adherence. The 2013 AASLD practice guideline states that patients “should be evaluated for and meet reasonable expectations for adherence to medical directives and mental health stability as determined by the psychosocial evaluation.”2 In the transplant setting, adherence is complex. It requires compliance with complicated medication regimens and laboratory testing, frequent follow-up appointments, and close, prompt communication of concerns to the health care team. Patient adherence to medication regimens plays an important role in transplant outcomes.8 In fact, in patients who have undergone renal transplant, nonadherence to therapy is considered the leading cause of avoidable graft failure.9

A retrospective study of adult LT recipients found that pre-transplant chart evidence of nonadherence, such as missed laboratory testing and clinic visits, was a significant predictor of post-transplant nonadherence with immunosuppressant therapy. Pre-transplant unemployment status and a history of substance abuse also were associated with nonadherence.9

Dobbels et al10 found that patients with a self-reported history of pre-transplant non-adherence had a higher risk of being nonadherent with their immunosuppressive therapy after transplant (odd ratio [OR]: 7.9). Their self-report adherence questionnaire included questions that addressed pre-transplant smoking status, alcohol use, and adherence with medication. In this prospective study, researchers also found that patients with a low “conscientiousness” score were at a higher risk for post-transplant medication nonadherence (OR: 0.8).

Continue to: Studies have also found...

Studies have also found that patients with higher education are more at risk for post-transplant medication nonadherence. Higher education may be associated with higher employment status resulting in a busier lifestyle, a known risk factor that may prevent patients from regular medication adherence.11,12 Alternatively, it is possible that higher educated patients are “decisive” nonadherers who prefer independent decision-making regarding their disease and treatment.13

Substance use. The 2013 AASLD practice guideline lists “ongoing alcohol or illicit substance abuse” as one of the contraindications to LT.2 In guidelines from the Austrian Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Graziadei et al14 listed “alcohol addiction without motivation for alcohol abstinence and untreated/ongoing substance abuse” as absolute contraindications and “untreated alcohol abuse and other drug-related addiction” as relative contraindications. Hence, the pre-transplant evaluation should include a thorough substance use history, including duration, amount, previous attempts to quit, and motivation for abstinence.

Substance use history is especially important because alcoholic liver disease is the second most common indication for LT.2 Most LT programs require 6 months of abstinence before a patient can be considered for transplant.15 The 6-month period was based on studies demonstrating that pre-transplant abstinence from alcohol for <6 months is a risk factor for relapse.15 However, this guideline remains controversial because the transplant referral and workup may be delayed as the patient’s liver disease worsens. Other risk factors for substance relapse should also be taken into consideration, such as depression, personality disorders, lack of social support, severity of alcohol use, and family history of alcoholism.16 Lee and Leggio16 developed the Sustained Alcohol Use Post-Liver Transplant (SALT) score to identify patients who were at risk for sustained alcohol use posttransplant. The 4 SALT criteria are:

- >10 drinks per day at initial hospitalization (+4 points)

- multiple prior rehabilitation attempts (+4 points)

- prior alcohol‐related legal issues (+2 points), and

- prior illicit substance abuse (+1 point).

A SALT score can range from 0 to 11. Lee et al17 found a SALT score ≥5 had a 25% positive predictive value (95% confidence interval [CI]: 10% to 47%) and a SALT score of <5 had a 95% negative predictive value (95% CI: 89% to 98%) for sustained alcohol use post‐LT. Thus, the 2013 AASLD guideline cautions against delaying evaluation based on the 6-month abstinence rule, and instead recommends early transplant referral for patients with alcoholic liver disease to encourage such patients to begin addiction treatment.2

As part of the substance use history, it is important to ask about the patient’s smoking history. Approximately 60% of LT candidates have a history of smoking cigarettes.18 Tobacco use history is associated with increased post-transplant vascular complications, such as hepatic artery thrombosis or stenosis, portal vein thrombosis, and deep vein thrombosis.19 The 2013 AASLD guideline recommends that tobacco use should be prohibited in LT candidates.2 Pungpapong et al19 reported that smoking cessation for at least 2 years prior to transplant led to a significantly decreased risk of developing arterial complications, with an absolute risk reduction of approximately 16%.

Continue to: Liver cirrhosis due to...

Liver cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the leading causes for LT. In the United States, HCV is commonly transmitted during injection drug use. According to the 2013 AASLD guideline, ongoing illicit substance use is a relative contraindication to LT.2 It is important to note, however, that methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) is not a contraindication to LT. In fact, the 2013 AASLD guideline recommends that patients receiving MMT should not be required to reduce or stop therapy in order to be listed for transplant.2 Studies have shown that in 80% of patients, tapering MMT leads to illicit opiate relapse.20 Currently, there is no evidence that patients receiving MMT have poorer post-transplant outcomes compared with patients not receiving MMT.21

Whether cannabis use is a relative contraindication to LT remains controversial.22 Possible adverse effects of cannabis use in transplant patients include drug–drug interactions and infections. Hézode et al23 reported that daily cannabis use is significantly associated with an increased fibrosis progression rate in patients with chronic HCV infection. Another recent study found that a history of cannabis use was not associated with worse outcomes among patients on the LT waitlist.24 With the increased legalization of cannabis, more studies are needed to assess ongoing cannabis use in patients on the LT waitlist and post-LT outcomes.

Psychiatric history. When assessing a patient for possible LT, no psychiatric disorder is considered an absolute contraindication. Patients with a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, and those with intellectual disability can have successful, long-term outcomes with proper evaluation and preparation, including social support. However, empirical literature regarding transplant outcomes and predictive factors in patients with serious mental illness is scarce.2

Studies examining the predictive value of pre-transplant depression on post-transplant outcomes have had mixed results.25 Depression may predict lower post-transplant quality of life. Pre-LT suicidal thoughts (as noted on the Beck Depression Inventory, for example) are associated with post-LT depression.25 In contrast, available data show no significant effect of pre-transplant anxiety on post-LT outcomes. Similarly, pre-transplant cognitive performance appears not to predict survival or other post-transplant outcomes, but may predict poorer quality of life after transplant.25

A few psychiatric factors are considered relative contraindications for LT. These include severe personality disorders, active substance use with no motivation for treatment or abstinence, active psychosis, severe neurocognitive disorders, suicidality, and factitious disorder.7

Continue to: Social support

Social support. Assessing a pre-LT patient’s level of social support is an essential part of the psychosocial evaluation. According to the 2013 AASLD guideline, patients should have “adequate” social support both during the waitlist and post-operative periods.2 Lack of partnership is a significant predictor of poor post-transplant outcomes, such as late graft loss.10 Satapathy and Sanyal26 reported that among patients who receive an LT for alcoholic liver disease, those with immediate family support were less likely to relapse to using alcohol after transplant. Poor social support was also a predictor of post-transplant medication nonadherence.10 Thus, the patient needs enough social support to engage in the pre-transplant health care requirements and to participate in post-transplant recommendations until he/she is functioning independently post-transplant.

Screening tools

Various screening tools may be useful in a pre-LT evaluation. Three standardized assessment tools available specifically for pre-transplant psychosocial assessments are the Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (Table 26), the Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Transplantation,27 and the Transplant Evaluation Rating Scale.28 Instruments to aid in the assessment of depression, anxiety, and delirium,29-31 a structured personality assessment,32 coping inventories,33 neuropsychological batteries,34 and others also have been used to evaluate patients before LT. The self-rated Beck Depression Inventory and the clinician-rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale are commonly used.7 Other tools, such as the LEIPAD quality of life instrument and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), have been used to assess for perceived quality of life and psychological distress, respectively.35 These screening tools can be helpful as aids for the pre-LT evaluation; however, diagnoses and treatment plan recommendations require a psychiatric evaluation conducted by a trained clinician.

Treatment after liver transplant

Psychiatric issues. After LT, various psychiatric complications may arise, including (but not limited to) delirium7 and “paradoxical psychiatric syndrome” (PPS).36 Delirium can be managed by administering low-dose antipsychotic medications, limiting the use of benzodiazepines and medications with anticholinergic effects, implementing behavioral interventions (frequent orientation, maintaining sleep/wake cycle, limiting noise, presence of a family member or a sitter at bedside),37 and addressing the underlying etiology. Paradoxical psychiatric syndrome is defined as psychiatric symptoms that occur despite a successful LT. It develops within the first year of transplantation and is characterized by recipients having strong guilt feelings toward their donors.38

Drug interactions. In the post-transplant period, antipsychotics are used for management of delirium and psychosis, antidepressants for anxiety and depression, and benzodiazepines for anxiety and sleep problems.7 Drug–drug interactions between psychotropic medications and the immunosuppressants required after LT must be closely monitored. First-generation antipsychotics should be avoided in post-transplant patients taking tacrolimus due to the increased risk of QTc prolongation. Tacrolimus can also increase the risk of nephrotoxicity when co-administered with lithium. Post-LT patients taking steroids and bupropion have an increased risk of seizure. Carbamazepine may decrease blood levels of cyclosporine due to the induction of hepatic metabolism.39,40 The psychiatrist should review and update the patient’s complete medication list at each visit, checking for possible medication interactions.

Quality of life. In the first 6 months post-transplant, patients typically experience improved quality of life in both physical and psychological domains. However, this improvement vacillates as the patient adjusts to post-transplant life. A reduction in BSI score 1 year after transplant has been reported. The BSI evaluates psychopathological symptoms, which are early indicators of psychological discomfort. One study noted a reduction in the LEIPAD quality of life score, which measures overall quality of life, 2 years after transplant.35 This decline may reflect the difficulties associated with the new challenges after transplant. Patients may endure both physical changes due to medical complications as well as psychological problems as they adjust to their new bodily integrity, their dependence on medications and medical staff, and other changes in function. Three to 5 years after transplant, patients reached a new psychological stability, with reported improvements in quality of life and decreased psychological distress.35

Continue to: Special populations

Special populations

HCV infection. Recurrent HCV infection and liver disease after transplantation are associated with psychological distress. This is particularly evident in patients 6 months after transplantation. Depression and psychological distress have been reported in male patients with recurrent HCV infection within the first year after transplantation.35

Acetaminophen overdose. Patients who receive a transplant for acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure (ALF) had a greater prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity as reflected by predefined diagnoses, medication, and previous suicide attempts.41 Despite this, outcomes for patients transplanted emergently for acetaminophen-induced ALF were comparable to those transplanted for non-acetaminophen-induced ALF and for chronic liver disease. Multidisciplinary approaches with long-term psychiatric follow-up may contribute to low post-transplant suicide rates and low rates of graft loss because of noncompliance.41

CASE REPORT

A complicated presentation

Ms. A, age 45, a married woman with history of chronic back pain and self-reported bipolar disorder, presented to our hospital with acute liver failure secondary to acetaminophen overdose. Her Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score on presentation was 38 (range: 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating increased likelihood of mortality). Her urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines and opiates. On hospital Day 2, the primary team consulted psychiatry for a pre-transplant evaluation and consideration of suicidality. Hepatology, toxicology, and transplant surgery services also were consulted.

Because Ms. A was intubated for acute respiratory failure, the initial history was gathered from family, a review of the medical record, consultation with her pharmacy, and collateral from her outpatient physician. Ms. A had been taking

Four days before presenting with acute liver failure, Ms. A had visited another hospital for lethargy. Benzodiazepines and opiates were stopped abruptly, and she was discharged with the recommendation to take acetaminophen for her pain. Approximately 24 hours after returning home, Ms. A began having auditory and visual hallucinations, and she did not sleep for days. She continued to complain of pain and was taking acetaminophen as recommended by the outside hospital. Her husband notes that she was intermittently confused. He was unsure how much acetaminophen she was taking.

Continue to: Her family noted...

Her family noted Ms. A had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder “years ago” but was unable to describe any manic episodes, and Ms. A had been treated only with an antidepressant from her primary care physician. She had persistent low mood and increased sleep since developing chronic back pain that severely limited her functioning. Ms. A attempted suicide once years ago by cutting her wrists. She had 2 prior psychiatric hospitalizations for suicidal ideation and the suicide attempt; however, she had not recently voiced suicidal ideation to her husband or family. She was adherent to psychotropic medications and follow-up appointments. Ms. A is a current smoker. She had used marijuana in the past, but her family denies current use, as well as any alcohol use or illicit substance use.

Ms. A’s diagnosis was consistent with tobacco use disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD). She likely developed withdrawal after abrupt cessation of diazepam, which she had been taking as prescribed for years. There was no evidence at the time of her initial psychiatric evaluation that the acetaminophen overdose was a suicide attempt; however, because Ms. A was intubated and sedated at that time, the consultation team recommended direct observation until she could participate in a risk assessment.

For the pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation, our consultation-liaison team noted Ms. A’s history of MDD, with recent active symptoms, chronic pain, and a past suicide attempt. She was a current tobacco smoker, which increases the risk of post-transplant vascular problems. However, she had been adherent to medications and follow-up, had very close family support, and there was no clear evidence that this acetaminophen ingestion was a suicide attempt. We noted that outpatient psychiatric follow-up and better chronic pain management would be helpful post-transplant. We would have to re-evaluate Ms. A when she was medically stable enough to communicate before making any further recommendations. Due to medical complications that developed after our evaluation, the transplant team noted Ms. A was no longer a transplant candidate.

Fortunately, Ms. A recovered with medical management over the next 2 weeks. She denied any suicidal ideation throughout her hospitalization. She was restarted on an antidepressant and received supportive therapy until discharge. Outpatient psychiatry follow-up and pain management was set up before Ms. A was discharged. Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization was not recommended. Per available records, Ms. A followed up with all outpatient appointments, including with her psychiatrist, since discharge.

Avoiding problems, maximizing outcomes

In addition to medical factors, psychosocial factors may affect the success of LT, although empirical data regarding which factors are most predictive of post-transplant outcomes is lacking, especially in patients with serious mental illness. The goals of a psychosocial pre-transplant evaluation are to promote fairness and equal access to care, maximize optimal outcomes, wisely use scarce resources, and ensure that the potential for benefits outweigh surgical risks to the patient. Identifying potential complicating factors (ie, substance abuse, nonadherence, serious psychopathology) can help guide the medical and psychiatric treatment plan and help minimize preventable problems both before and after transplant.42

Continue to: In patients who have...

In patients who have a history of alcohol use and alcohol liver disease, relapse to alcohol is a significant problem. Relapse rates vary from 10% to 30%.7 The duration of abstinence before LT appears to be a poor predictor of abstinence after LT.43 Polysubstance use also adversely affects outcomes in patients with alcohol liver disease. Approximately one-third of patients with polysubstance use who receive a LT relapse to substance use.44 Coffman et al45 showed that the presence of antisocial behavior and eating disorders may increase the risk of relapse after LT.

The psychiatrist’s role in the setting of LT spans from the pre-transplant assessment to post-transplant management and follow-up. Clarifying specific psychiatric diagnoses, psychosocial factors that need to be addressed before transplant, and substance use diagnoses and treatment recommendations can help the transplant team clearly identify modifiable factors that can affect transplant outcomes.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can help patients who are candidates for liver transplantation (LT) by performing a pre-transplant psychosocial assessment to identity factors that might complicate transplantation or recovery. After LT, patients require careful monitoring for psychiatric comorbidities, drug interactions, and other factors that can affect quality of life.

Related Resources

- Beresford TP, Lucey MR. Towards standardizing the alcoholism evaluation of potential liver transplant recipients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(2):135-144.

- Marcangelo MJ, Crone C. Tools, techniques to assess organ transplant candidates. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(9):56-66.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Diazepam • Valium

Hydromorphone • Dilaudid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Tacrolimus • Astagraf XL, Envarsus XR

1. Meirelles Júnior RF, Salvalaggio P, Rezende MB, et al. Liver transplantation: history, outcomes and perspectives [Article in English, Portuguese]. Einstein (São Paulo). 2015;13(1):149-152.

2. Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1144-1165.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. QuickStats: number of deaths from 10 leading causes,* by sex—National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(15):413.

4. Trieu JA, Bilal M, Hmoud B. Factors associated with waiting time on the liver transplant list: an analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31(1):84-89.

5. Neuberger J. An update on liver transplantation: a critical review. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:51-59.

6. Maldonado JR, Dubois HC, David EE, et al. The Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (SIPAT): a new tool for the psychosocial evaluation of pre-transplant candidates. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):123-132.

7. Grover S, Sarkar S. Liver transplant—psychiatric and psychosocial aspects. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2(4):382-392.

8. Burra P, Germani G, Gnoato F, et al. Adherence in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(7):760-770.

9. Lieber SR, Volk ML. Non-adherence and graft failure in adult liver transplant recipients. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(3):824-834.

10. Dobbels F, Vanhaecke J, Dupont L, et al. Pretransplant predictors of posttransplant adherence and clinical outcome: an evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screening. Transplantation. 2009;87(10):1497-1504.

11. De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(4):323.

12. Park DC, Hertzog C, Leventhal H, et al. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients: older is wiser. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(2):172-183.

13. Greenstein S, Siegal B. Compliance and noncompliance in patients with a functioning renal transplant: a multicenter study. Transplantation. 1998;66(12):1718-1726.

14. Graziadei I, Zoller H, Fickert P, et al. Indications for liver transplantation in adults: Recommendations of the Austrian Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology (ÖGGH) in cooperation with the Austrian Society for Transplantation, Transfusion and Genetics (ATX). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128(19):679-690.

15. Addolorato G, Bataller R, Burra P, et al. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Transplantation. 2016;100(5):981-987.

16. Lee MR, Leggio L. Management of alcohol use disorder in patients requiring liver transplant. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(12):1182-1189.

17. Lee BP, Vittinghoff E, Hsu C, et al. Predicting low risk for sustained alcohol use after early liver transplant for acute alcoholic hepatitis: the Sustained Alcohol Use Post-Liver Transplant score. Hepatology. 2019;69(4):1477-1487.

18. DiMartini A, Crone C, Dew MA. Alcohol and substance use in liver transplant patients. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2011;15(4):727-751.

19. Pungpapong S, Manzarbeitia C, Ortiz J, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with an increased incidence of vascular complications after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8(7):582-587.

20. Kreek MJ. Pharmacotherapy of opioid dependence: rationale and update. Regulatory Peptides. 1994;53(suppl 1):S255-S256.

21. Jiao M, Greanya ED, Haque M, et al. Methadone maintenance therapy in liver transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2010;20(3):209-214; quiz 215.

22. Rai HS, Winder GS. Marijuana use and organ transplantation: a review and implications for clinical practice. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(11):91.

23. Hézode C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Nguyen S, et al. Daily cannabis smoking as a risk factor for progression of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;42(1):63-71.

24. Kotwani P, Saxena V, Dodge JL, et al. History of marijuana use does not affect outcomes on the liver transplant waitlist. Transplantation. 2018;102(5):794-802.

25. Fineberg SK, West A, Na PJ, et al. Utility of pretransplant psychological measures to predict posttransplant outcomes in liver transplant patients: a systematic review. Gen Hospl Psychiatry. 2016;40:4-11.

26. Satapathy S, Sanyal A. Epidemiology and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(3):221-235.

27. Olbrisch ME, Levenson JL, Hamer R. The PACT: a rating scale for the study of clinical decision making in psychosocial screening of organ transplant candidates. Clin Transplant. 1989;3:164-169.

28. Twillman RK, Manetto C, Wellisch DK, et al. Transplant Evaluation Rating Scale: a revision of the psychosocial levels system for evaluating organ transplant candidates. Psychosomatics. 1993;34(2):144-153.

29. Goodier J. Evaluating Stress:97496. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, eds. Evaluating stress: a book of resources. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press; 1997:29-29.

30. Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin, MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;8(1):77-100.

31. Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, et al. Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98: comparison with the Delirium Rating Scale and the Cognitive Test for Delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):229-242.

32. Cottle WC. The MMPI: a review. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas; 1953.

33. Addison CC, Campbell-Jenkins BW, Sarpong DF, et al. Psychometric Evaluation of a Coping Strategies Inventory Short-Form (CSI-SF) in the Jackson Heart Study Cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2007;4(4):289-295.

34. Mooney S, Hasssanein T, Hilsabeck R, et al. Utility of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) in patients with end-stage liver disease awaiting liver transplant. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(2):175-186.

35. De Bona M, Ponton P, Ermani M, et al. The impact of liver disease and medical complications on quality of life and psychological distress before and after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2000;33(4):609-615.

36. Fukunishi I, Sugawara Y, Takayama T, et al. Psychiatric disorders before and after living-related transplantation. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(4):337-343.

37. Landefeld CS, Palme, RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1338-1344.

38. Fukunishi I, Sugawara Y, Takayama T, et al. Psychiatric problems in living-related transplantation (II): the association between paradoxical psychiatric syndrome and guilt feelings in adult recipients after living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation Proceedings. 2002;34(7):2632-2633.

39. Campana C, Regazzi MB, Buggia I, et al. Clinically significant drug interactions with cyclosporin. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;30(2):141-179.

40. Ozkanlar Y, Nishijima Y, Cunha DD, et al. Acute effects of tacrolimus (FK506) on left ventricular mechanics. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52(4):307-312.

41. Karvellas CJ, Safinia N, Auzinger G, et al. Medical and psychiatric outcomes for patients transplanted for acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: a case-control study. Liver Int. 2010;30(6):826-833.

42. Maldonado J R. I have been asked to work up a patient who requires a liver transplant how should I proceed? FOCUS. 2009;7(3):332-335.

43. Mccallum S, Masterton G. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a systematic review of psychosocial selection criteria. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41(4):358-363.

44. Nickels M, Jain A, Sharma R, et al. Polysubstance abuse in liver transplant patients and its impact on survival outcome. Exp Clin Transplant. 2007;5(2):680-685.

45. Coffman KL, Hoffman A, Sher L, et al. Treatment of the postoperative alcoholic liver transplant recipient with other addictions. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3(3):322-327.

Since the first liver transplant (LT) was performed in 1963 by Starzl et al, there have been considerable advances in the field, with improvements in post-transplant survival.1 There are multiple indications for LT, including acute liver failure and index complications of cirrhosis such as ascites, encephalopathy, and hepatopulmonary syndrome.2 Once a patient develops one of these conditions, he/she is evaluated for LT, even as the complications of liver failure are being managed.

Although the number of LTs has risen, the demand for transplant continues to exceed availability. In 2015, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis was the 12th leading cause of death in the United States.3 In 2016, approximately 50% of waitlisted candidates received a transplant.4 There is also a donor shortage. In part, this shortage may be due to longer life spans and the subsequent increase in the age of the potential donor.5 In light of this shortage and increased demand, the pre-LT workup is comprehensive. The pre-transplant assessment typically consists of cardiology, surgery, hepatology, and psychosocial evaluations, and hence requires a team of experts to determine who is an ideal candidate for transplant.

Psychiatrists play a key role in the pre-transplant psychosocial evaluations. This article describes the elements of these evaluations, and what psychiatrists can do to help patients both before and after they undergo LT.

Elements of the pre-transplant evaluation

The psychosocial evaluation is a critical component of the pre-transplant assessment. As part of the evaluation, patients are screened for psychosocial limitations that may complicate transplantation, such as demonstrated noncompliance, ongoing alcohol or drug use, and lack of social support (Table 12 ). Other goals of the psychosocial evaluation are to identify in the pre-transplant period patients with possible risk factors, such as substance use or psychiatric disorders, and develop treatment plans to optimize transplant outcomes (Table 26). There are relative contraindications to LT (Table 37) but no absolute psychiatric contraindications, according to the 2013 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) practice guideline for transplantation.2

Adherence. The 2013 AASLD practice guideline states that patients “should be evaluated for and meet reasonable expectations for adherence to medical directives and mental health stability as determined by the psychosocial evaluation.”2 In the transplant setting, adherence is complex. It requires compliance with complicated medication regimens and laboratory testing, frequent follow-up appointments, and close, prompt communication of concerns to the health care team. Patient adherence to medication regimens plays an important role in transplant outcomes.8 In fact, in patients who have undergone renal transplant, nonadherence to therapy is considered the leading cause of avoidable graft failure.9

A retrospective study of adult LT recipients found that pre-transplant chart evidence of nonadherence, such as missed laboratory testing and clinic visits, was a significant predictor of post-transplant nonadherence with immunosuppressant therapy. Pre-transplant unemployment status and a history of substance abuse also were associated with nonadherence.9

Dobbels et al10 found that patients with a self-reported history of pre-transplant non-adherence had a higher risk of being nonadherent with their immunosuppressive therapy after transplant (odd ratio [OR]: 7.9). Their self-report adherence questionnaire included questions that addressed pre-transplant smoking status, alcohol use, and adherence with medication. In this prospective study, researchers also found that patients with a low “conscientiousness” score were at a higher risk for post-transplant medication nonadherence (OR: 0.8).

Continue to: Studies have also found...

Studies have also found that patients with higher education are more at risk for post-transplant medication nonadherence. Higher education may be associated with higher employment status resulting in a busier lifestyle, a known risk factor that may prevent patients from regular medication adherence.11,12 Alternatively, it is possible that higher educated patients are “decisive” nonadherers who prefer independent decision-making regarding their disease and treatment.13

Substance use. The 2013 AASLD practice guideline lists “ongoing alcohol or illicit substance abuse” as one of the contraindications to LT.2 In guidelines from the Austrian Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Graziadei et al14 listed “alcohol addiction without motivation for alcohol abstinence and untreated/ongoing substance abuse” as absolute contraindications and “untreated alcohol abuse and other drug-related addiction” as relative contraindications. Hence, the pre-transplant evaluation should include a thorough substance use history, including duration, amount, previous attempts to quit, and motivation for abstinence.

Substance use history is especially important because alcoholic liver disease is the second most common indication for LT.2 Most LT programs require 6 months of abstinence before a patient can be considered for transplant.15 The 6-month period was based on studies demonstrating that pre-transplant abstinence from alcohol for <6 months is a risk factor for relapse.15 However, this guideline remains controversial because the transplant referral and workup may be delayed as the patient’s liver disease worsens. Other risk factors for substance relapse should also be taken into consideration, such as depression, personality disorders, lack of social support, severity of alcohol use, and family history of alcoholism.16 Lee and Leggio16 developed the Sustained Alcohol Use Post-Liver Transplant (SALT) score to identify patients who were at risk for sustained alcohol use posttransplant. The 4 SALT criteria are:

- >10 drinks per day at initial hospitalization (+4 points)

- multiple prior rehabilitation attempts (+4 points)

- prior alcohol‐related legal issues (+2 points), and

- prior illicit substance abuse (+1 point).

A SALT score can range from 0 to 11. Lee et al17 found a SALT score ≥5 had a 25% positive predictive value (95% confidence interval [CI]: 10% to 47%) and a SALT score of <5 had a 95% negative predictive value (95% CI: 89% to 98%) for sustained alcohol use post‐LT. Thus, the 2013 AASLD guideline cautions against delaying evaluation based on the 6-month abstinence rule, and instead recommends early transplant referral for patients with alcoholic liver disease to encourage such patients to begin addiction treatment.2

As part of the substance use history, it is important to ask about the patient’s smoking history. Approximately 60% of LT candidates have a history of smoking cigarettes.18 Tobacco use history is associated with increased post-transplant vascular complications, such as hepatic artery thrombosis or stenosis, portal vein thrombosis, and deep vein thrombosis.19 The 2013 AASLD guideline recommends that tobacco use should be prohibited in LT candidates.2 Pungpapong et al19 reported that smoking cessation for at least 2 years prior to transplant led to a significantly decreased risk of developing arterial complications, with an absolute risk reduction of approximately 16%.

Continue to: Liver cirrhosis due to...

Liver cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the leading causes for LT. In the United States, HCV is commonly transmitted during injection drug use. According to the 2013 AASLD guideline, ongoing illicit substance use is a relative contraindication to LT.2 It is important to note, however, that methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) is not a contraindication to LT. In fact, the 2013 AASLD guideline recommends that patients receiving MMT should not be required to reduce or stop therapy in order to be listed for transplant.2 Studies have shown that in 80% of patients, tapering MMT leads to illicit opiate relapse.20 Currently, there is no evidence that patients receiving MMT have poorer post-transplant outcomes compared with patients not receiving MMT.21

Whether cannabis use is a relative contraindication to LT remains controversial.22 Possible adverse effects of cannabis use in transplant patients include drug–drug interactions and infections. Hézode et al23 reported that daily cannabis use is significantly associated with an increased fibrosis progression rate in patients with chronic HCV infection. Another recent study found that a history of cannabis use was not associated with worse outcomes among patients on the LT waitlist.24 With the increased legalization of cannabis, more studies are needed to assess ongoing cannabis use in patients on the LT waitlist and post-LT outcomes.

Psychiatric history. When assessing a patient for possible LT, no psychiatric disorder is considered an absolute contraindication. Patients with a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, and those with intellectual disability can have successful, long-term outcomes with proper evaluation and preparation, including social support. However, empirical literature regarding transplant outcomes and predictive factors in patients with serious mental illness is scarce.2

Studies examining the predictive value of pre-transplant depression on post-transplant outcomes have had mixed results.25 Depression may predict lower post-transplant quality of life. Pre-LT suicidal thoughts (as noted on the Beck Depression Inventory, for example) are associated with post-LT depression.25 In contrast, available data show no significant effect of pre-transplant anxiety on post-LT outcomes. Similarly, pre-transplant cognitive performance appears not to predict survival or other post-transplant outcomes, but may predict poorer quality of life after transplant.25

A few psychiatric factors are considered relative contraindications for LT. These include severe personality disorders, active substance use with no motivation for treatment or abstinence, active psychosis, severe neurocognitive disorders, suicidality, and factitious disorder.7

Continue to: Social support

Social support. Assessing a pre-LT patient’s level of social support is an essential part of the psychosocial evaluation. According to the 2013 AASLD guideline, patients should have “adequate” social support both during the waitlist and post-operative periods.2 Lack of partnership is a significant predictor of poor post-transplant outcomes, such as late graft loss.10 Satapathy and Sanyal26 reported that among patients who receive an LT for alcoholic liver disease, those with immediate family support were less likely to relapse to using alcohol after transplant. Poor social support was also a predictor of post-transplant medication nonadherence.10 Thus, the patient needs enough social support to engage in the pre-transplant health care requirements and to participate in post-transplant recommendations until he/she is functioning independently post-transplant.

Screening tools

Various screening tools may be useful in a pre-LT evaluation. Three standardized assessment tools available specifically for pre-transplant psychosocial assessments are the Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (Table 26), the Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Transplantation,27 and the Transplant Evaluation Rating Scale.28 Instruments to aid in the assessment of depression, anxiety, and delirium,29-31 a structured personality assessment,32 coping inventories,33 neuropsychological batteries,34 and others also have been used to evaluate patients before LT. The self-rated Beck Depression Inventory and the clinician-rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale are commonly used.7 Other tools, such as the LEIPAD quality of life instrument and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), have been used to assess for perceived quality of life and psychological distress, respectively.35 These screening tools can be helpful as aids for the pre-LT evaluation; however, diagnoses and treatment plan recommendations require a psychiatric evaluation conducted by a trained clinician.

Treatment after liver transplant

Psychiatric issues. After LT, various psychiatric complications may arise, including (but not limited to) delirium7 and “paradoxical psychiatric syndrome” (PPS).36 Delirium can be managed by administering low-dose antipsychotic medications, limiting the use of benzodiazepines and medications with anticholinergic effects, implementing behavioral interventions (frequent orientation, maintaining sleep/wake cycle, limiting noise, presence of a family member or a sitter at bedside),37 and addressing the underlying etiology. Paradoxical psychiatric syndrome is defined as psychiatric symptoms that occur despite a successful LT. It develops within the first year of transplantation and is characterized by recipients having strong guilt feelings toward their donors.38

Drug interactions. In the post-transplant period, antipsychotics are used for management of delirium and psychosis, antidepressants for anxiety and depression, and benzodiazepines for anxiety and sleep problems.7 Drug–drug interactions between psychotropic medications and the immunosuppressants required after LT must be closely monitored. First-generation antipsychotics should be avoided in post-transplant patients taking tacrolimus due to the increased risk of QTc prolongation. Tacrolimus can also increase the risk of nephrotoxicity when co-administered with lithium. Post-LT patients taking steroids and bupropion have an increased risk of seizure. Carbamazepine may decrease blood levels of cyclosporine due to the induction of hepatic metabolism.39,40 The psychiatrist should review and update the patient’s complete medication list at each visit, checking for possible medication interactions.

Quality of life. In the first 6 months post-transplant, patients typically experience improved quality of life in both physical and psychological domains. However, this improvement vacillates as the patient adjusts to post-transplant life. A reduction in BSI score 1 year after transplant has been reported. The BSI evaluates psychopathological symptoms, which are early indicators of psychological discomfort. One study noted a reduction in the LEIPAD quality of life score, which measures overall quality of life, 2 years after transplant.35 This decline may reflect the difficulties associated with the new challenges after transplant. Patients may endure both physical changes due to medical complications as well as psychological problems as they adjust to their new bodily integrity, their dependence on medications and medical staff, and other changes in function. Three to 5 years after transplant, patients reached a new psychological stability, with reported improvements in quality of life and decreased psychological distress.35

Continue to: Special populations

Special populations

HCV infection. Recurrent HCV infection and liver disease after transplantation are associated with psychological distress. This is particularly evident in patients 6 months after transplantation. Depression and psychological distress have been reported in male patients with recurrent HCV infection within the first year after transplantation.35

Acetaminophen overdose. Patients who receive a transplant for acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure (ALF) had a greater prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity as reflected by predefined diagnoses, medication, and previous suicide attempts.41 Despite this, outcomes for patients transplanted emergently for acetaminophen-induced ALF were comparable to those transplanted for non-acetaminophen-induced ALF and for chronic liver disease. Multidisciplinary approaches with long-term psychiatric follow-up may contribute to low post-transplant suicide rates and low rates of graft loss because of noncompliance.41

CASE REPORT

A complicated presentation

Ms. A, age 45, a married woman with history of chronic back pain and self-reported bipolar disorder, presented to our hospital with acute liver failure secondary to acetaminophen overdose. Her Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score on presentation was 38 (range: 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating increased likelihood of mortality). Her urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines and opiates. On hospital Day 2, the primary team consulted psychiatry for a pre-transplant evaluation and consideration of suicidality. Hepatology, toxicology, and transplant surgery services also were consulted.

Because Ms. A was intubated for acute respiratory failure, the initial history was gathered from family, a review of the medical record, consultation with her pharmacy, and collateral from her outpatient physician. Ms. A had been taking

Four days before presenting with acute liver failure, Ms. A had visited another hospital for lethargy. Benzodiazepines and opiates were stopped abruptly, and she was discharged with the recommendation to take acetaminophen for her pain. Approximately 24 hours after returning home, Ms. A began having auditory and visual hallucinations, and she did not sleep for days. She continued to complain of pain and was taking acetaminophen as recommended by the outside hospital. Her husband notes that she was intermittently confused. He was unsure how much acetaminophen she was taking.

Continue to: Her family noted...

Her family noted Ms. A had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder “years ago” but was unable to describe any manic episodes, and Ms. A had been treated only with an antidepressant from her primary care physician. She had persistent low mood and increased sleep since developing chronic back pain that severely limited her functioning. Ms. A attempted suicide once years ago by cutting her wrists. She had 2 prior psychiatric hospitalizations for suicidal ideation and the suicide attempt; however, she had not recently voiced suicidal ideation to her husband or family. She was adherent to psychotropic medications and follow-up appointments. Ms. A is a current smoker. She had used marijuana in the past, but her family denies current use, as well as any alcohol use or illicit substance use.

Ms. A’s diagnosis was consistent with tobacco use disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD). She likely developed withdrawal after abrupt cessation of diazepam, which she had been taking as prescribed for years. There was no evidence at the time of her initial psychiatric evaluation that the acetaminophen overdose was a suicide attempt; however, because Ms. A was intubated and sedated at that time, the consultation team recommended direct observation until she could participate in a risk assessment.

For the pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation, our consultation-liaison team noted Ms. A’s history of MDD, with recent active symptoms, chronic pain, and a past suicide attempt. She was a current tobacco smoker, which increases the risk of post-transplant vascular problems. However, she had been adherent to medications and follow-up, had very close family support, and there was no clear evidence that this acetaminophen ingestion was a suicide attempt. We noted that outpatient psychiatric follow-up and better chronic pain management would be helpful post-transplant. We would have to re-evaluate Ms. A when she was medically stable enough to communicate before making any further recommendations. Due to medical complications that developed after our evaluation, the transplant team noted Ms. A was no longer a transplant candidate.

Fortunately, Ms. A recovered with medical management over the next 2 weeks. She denied any suicidal ideation throughout her hospitalization. She was restarted on an antidepressant and received supportive therapy until discharge. Outpatient psychiatry follow-up and pain management was set up before Ms. A was discharged. Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization was not recommended. Per available records, Ms. A followed up with all outpatient appointments, including with her psychiatrist, since discharge.

Avoiding problems, maximizing outcomes

In addition to medical factors, psychosocial factors may affect the success of LT, although empirical data regarding which factors are most predictive of post-transplant outcomes is lacking, especially in patients with serious mental illness. The goals of a psychosocial pre-transplant evaluation are to promote fairness and equal access to care, maximize optimal outcomes, wisely use scarce resources, and ensure that the potential for benefits outweigh surgical risks to the patient. Identifying potential complicating factors (ie, substance abuse, nonadherence, serious psychopathology) can help guide the medical and psychiatric treatment plan and help minimize preventable problems both before and after transplant.42

Continue to: In patients who have...

In patients who have a history of alcohol use and alcohol liver disease, relapse to alcohol is a significant problem. Relapse rates vary from 10% to 30%.7 The duration of abstinence before LT appears to be a poor predictor of abstinence after LT.43 Polysubstance use also adversely affects outcomes in patients with alcohol liver disease. Approximately one-third of patients with polysubstance use who receive a LT relapse to substance use.44 Coffman et al45 showed that the presence of antisocial behavior and eating disorders may increase the risk of relapse after LT.

The psychiatrist’s role in the setting of LT spans from the pre-transplant assessment to post-transplant management and follow-up. Clarifying specific psychiatric diagnoses, psychosocial factors that need to be addressed before transplant, and substance use diagnoses and treatment recommendations can help the transplant team clearly identify modifiable factors that can affect transplant outcomes.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can help patients who are candidates for liver transplantation (LT) by performing a pre-transplant psychosocial assessment to identity factors that might complicate transplantation or recovery. After LT, patients require careful monitoring for psychiatric comorbidities, drug interactions, and other factors that can affect quality of life.

Related Resources

- Beresford TP, Lucey MR. Towards standardizing the alcoholism evaluation of potential liver transplant recipients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(2):135-144.

- Marcangelo MJ, Crone C. Tools, techniques to assess organ transplant candidates. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(9):56-66.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Diazepam • Valium

Hydromorphone • Dilaudid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Tacrolimus • Astagraf XL, Envarsus XR

Since the first liver transplant (LT) was performed in 1963 by Starzl et al, there have been considerable advances in the field, with improvements in post-transplant survival.1 There are multiple indications for LT, including acute liver failure and index complications of cirrhosis such as ascites, encephalopathy, and hepatopulmonary syndrome.2 Once a patient develops one of these conditions, he/she is evaluated for LT, even as the complications of liver failure are being managed.

Although the number of LTs has risen, the demand for transplant continues to exceed availability. In 2015, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis was the 12th leading cause of death in the United States.3 In 2016, approximately 50% of waitlisted candidates received a transplant.4 There is also a donor shortage. In part, this shortage may be due to longer life spans and the subsequent increase in the age of the potential donor.5 In light of this shortage and increased demand, the pre-LT workup is comprehensive. The pre-transplant assessment typically consists of cardiology, surgery, hepatology, and psychosocial evaluations, and hence requires a team of experts to determine who is an ideal candidate for transplant.

Psychiatrists play a key role in the pre-transplant psychosocial evaluations. This article describes the elements of these evaluations, and what psychiatrists can do to help patients both before and after they undergo LT.

Elements of the pre-transplant evaluation

The psychosocial evaluation is a critical component of the pre-transplant assessment. As part of the evaluation, patients are screened for psychosocial limitations that may complicate transplantation, such as demonstrated noncompliance, ongoing alcohol or drug use, and lack of social support (Table 12 ). Other goals of the psychosocial evaluation are to identify in the pre-transplant period patients with possible risk factors, such as substance use or psychiatric disorders, and develop treatment plans to optimize transplant outcomes (Table 26). There are relative contraindications to LT (Table 37) but no absolute psychiatric contraindications, according to the 2013 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) practice guideline for transplantation.2

Adherence. The 2013 AASLD practice guideline states that patients “should be evaluated for and meet reasonable expectations for adherence to medical directives and mental health stability as determined by the psychosocial evaluation.”2 In the transplant setting, adherence is complex. It requires compliance with complicated medication regimens and laboratory testing, frequent follow-up appointments, and close, prompt communication of concerns to the health care team. Patient adherence to medication regimens plays an important role in transplant outcomes.8 In fact, in patients who have undergone renal transplant, nonadherence to therapy is considered the leading cause of avoidable graft failure.9

A retrospective study of adult LT recipients found that pre-transplant chart evidence of nonadherence, such as missed laboratory testing and clinic visits, was a significant predictor of post-transplant nonadherence with immunosuppressant therapy. Pre-transplant unemployment status and a history of substance abuse also were associated with nonadherence.9

Dobbels et al10 found that patients with a self-reported history of pre-transplant non-adherence had a higher risk of being nonadherent with their immunosuppressive therapy after transplant (odd ratio [OR]: 7.9). Their self-report adherence questionnaire included questions that addressed pre-transplant smoking status, alcohol use, and adherence with medication. In this prospective study, researchers also found that patients with a low “conscientiousness” score were at a higher risk for post-transplant medication nonadherence (OR: 0.8).

Continue to: Studies have also found...

Studies have also found that patients with higher education are more at risk for post-transplant medication nonadherence. Higher education may be associated with higher employment status resulting in a busier lifestyle, a known risk factor that may prevent patients from regular medication adherence.11,12 Alternatively, it is possible that higher educated patients are “decisive” nonadherers who prefer independent decision-making regarding their disease and treatment.13

Substance use. The 2013 AASLD practice guideline lists “ongoing alcohol or illicit substance abuse” as one of the contraindications to LT.2 In guidelines from the Austrian Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Graziadei et al14 listed “alcohol addiction without motivation for alcohol abstinence and untreated/ongoing substance abuse” as absolute contraindications and “untreated alcohol abuse and other drug-related addiction” as relative contraindications. Hence, the pre-transplant evaluation should include a thorough substance use history, including duration, amount, previous attempts to quit, and motivation for abstinence.

Substance use history is especially important because alcoholic liver disease is the second most common indication for LT.2 Most LT programs require 6 months of abstinence before a patient can be considered for transplant.15 The 6-month period was based on studies demonstrating that pre-transplant abstinence from alcohol for <6 months is a risk factor for relapse.15 However, this guideline remains controversial because the transplant referral and workup may be delayed as the patient’s liver disease worsens. Other risk factors for substance relapse should also be taken into consideration, such as depression, personality disorders, lack of social support, severity of alcohol use, and family history of alcoholism.16 Lee and Leggio16 developed the Sustained Alcohol Use Post-Liver Transplant (SALT) score to identify patients who were at risk for sustained alcohol use posttransplant. The 4 SALT criteria are:

- >10 drinks per day at initial hospitalization (+4 points)

- multiple prior rehabilitation attempts (+4 points)

- prior alcohol‐related legal issues (+2 points), and

- prior illicit substance abuse (+1 point).

A SALT score can range from 0 to 11. Lee et al17 found a SALT score ≥5 had a 25% positive predictive value (95% confidence interval [CI]: 10% to 47%) and a SALT score of <5 had a 95% negative predictive value (95% CI: 89% to 98%) for sustained alcohol use post‐LT. Thus, the 2013 AASLD guideline cautions against delaying evaluation based on the 6-month abstinence rule, and instead recommends early transplant referral for patients with alcoholic liver disease to encourage such patients to begin addiction treatment.2

As part of the substance use history, it is important to ask about the patient’s smoking history. Approximately 60% of LT candidates have a history of smoking cigarettes.18 Tobacco use history is associated with increased post-transplant vascular complications, such as hepatic artery thrombosis or stenosis, portal vein thrombosis, and deep vein thrombosis.19 The 2013 AASLD guideline recommends that tobacco use should be prohibited in LT candidates.2 Pungpapong et al19 reported that smoking cessation for at least 2 years prior to transplant led to a significantly decreased risk of developing arterial complications, with an absolute risk reduction of approximately 16%.

Continue to: Liver cirrhosis due to...

Liver cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the leading causes for LT. In the United States, HCV is commonly transmitted during injection drug use. According to the 2013 AASLD guideline, ongoing illicit substance use is a relative contraindication to LT.2 It is important to note, however, that methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) is not a contraindication to LT. In fact, the 2013 AASLD guideline recommends that patients receiving MMT should not be required to reduce or stop therapy in order to be listed for transplant.2 Studies have shown that in 80% of patients, tapering MMT leads to illicit opiate relapse.20 Currently, there is no evidence that patients receiving MMT have poorer post-transplant outcomes compared with patients not receiving MMT.21

Whether cannabis use is a relative contraindication to LT remains controversial.22 Possible adverse effects of cannabis use in transplant patients include drug–drug interactions and infections. Hézode et al23 reported that daily cannabis use is significantly associated with an increased fibrosis progression rate in patients with chronic HCV infection. Another recent study found that a history of cannabis use was not associated with worse outcomes among patients on the LT waitlist.24 With the increased legalization of cannabis, more studies are needed to assess ongoing cannabis use in patients on the LT waitlist and post-LT outcomes.

Psychiatric history. When assessing a patient for possible LT, no psychiatric disorder is considered an absolute contraindication. Patients with a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, and those with intellectual disability can have successful, long-term outcomes with proper evaluation and preparation, including social support. However, empirical literature regarding transplant outcomes and predictive factors in patients with serious mental illness is scarce.2

Studies examining the predictive value of pre-transplant depression on post-transplant outcomes have had mixed results.25 Depression may predict lower post-transplant quality of life. Pre-LT suicidal thoughts (as noted on the Beck Depression Inventory, for example) are associated with post-LT depression.25 In contrast, available data show no significant effect of pre-transplant anxiety on post-LT outcomes. Similarly, pre-transplant cognitive performance appears not to predict survival or other post-transplant outcomes, but may predict poorer quality of life after transplant.25

A few psychiatric factors are considered relative contraindications for LT. These include severe personality disorders, active substance use with no motivation for treatment or abstinence, active psychosis, severe neurocognitive disorders, suicidality, and factitious disorder.7

Continue to: Social support

Social support. Assessing a pre-LT patient’s level of social support is an essential part of the psychosocial evaluation. According to the 2013 AASLD guideline, patients should have “adequate” social support both during the waitlist and post-operative periods.2 Lack of partnership is a significant predictor of poor post-transplant outcomes, such as late graft loss.10 Satapathy and Sanyal26 reported that among patients who receive an LT for alcoholic liver disease, those with immediate family support were less likely to relapse to using alcohol after transplant. Poor social support was also a predictor of post-transplant medication nonadherence.10 Thus, the patient needs enough social support to engage in the pre-transplant health care requirements and to participate in post-transplant recommendations until he/she is functioning independently post-transplant.

Screening tools

Various screening tools may be useful in a pre-LT evaluation. Three standardized assessment tools available specifically for pre-transplant psychosocial assessments are the Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (Table 26), the Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Transplantation,27 and the Transplant Evaluation Rating Scale.28 Instruments to aid in the assessment of depression, anxiety, and delirium,29-31 a structured personality assessment,32 coping inventories,33 neuropsychological batteries,34 and others also have been used to evaluate patients before LT. The self-rated Beck Depression Inventory and the clinician-rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale are commonly used.7 Other tools, such as the LEIPAD quality of life instrument and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), have been used to assess for perceived quality of life and psychological distress, respectively.35 These screening tools can be helpful as aids for the pre-LT evaluation; however, diagnoses and treatment plan recommendations require a psychiatric evaluation conducted by a trained clinician.

Treatment after liver transplant

Psychiatric issues. After LT, various psychiatric complications may arise, including (but not limited to) delirium7 and “paradoxical psychiatric syndrome” (PPS).36 Delirium can be managed by administering low-dose antipsychotic medications, limiting the use of benzodiazepines and medications with anticholinergic effects, implementing behavioral interventions (frequent orientation, maintaining sleep/wake cycle, limiting noise, presence of a family member or a sitter at bedside),37 and addressing the underlying etiology. Paradoxical psychiatric syndrome is defined as psychiatric symptoms that occur despite a successful LT. It develops within the first year of transplantation and is characterized by recipients having strong guilt feelings toward their donors.38

Drug interactions. In the post-transplant period, antipsychotics are used for management of delirium and psychosis, antidepressants for anxiety and depression, and benzodiazepines for anxiety and sleep problems.7 Drug–drug interactions between psychotropic medications and the immunosuppressants required after LT must be closely monitored. First-generation antipsychotics should be avoided in post-transplant patients taking tacrolimus due to the increased risk of QTc prolongation. Tacrolimus can also increase the risk of nephrotoxicity when co-administered with lithium. Post-LT patients taking steroids and bupropion have an increased risk of seizure. Carbamazepine may decrease blood levels of cyclosporine due to the induction of hepatic metabolism.39,40 The psychiatrist should review and update the patient’s complete medication list at each visit, checking for possible medication interactions.

Quality of life. In the first 6 months post-transplant, patients typically experience improved quality of life in both physical and psychological domains. However, this improvement vacillates as the patient adjusts to post-transplant life. A reduction in BSI score 1 year after transplant has been reported. The BSI evaluates psychopathological symptoms, which are early indicators of psychological discomfort. One study noted a reduction in the LEIPAD quality of life score, which measures overall quality of life, 2 years after transplant.35 This decline may reflect the difficulties associated with the new challenges after transplant. Patients may endure both physical changes due to medical complications as well as psychological problems as they adjust to their new bodily integrity, their dependence on medications and medical staff, and other changes in function. Three to 5 years after transplant, patients reached a new psychological stability, with reported improvements in quality of life and decreased psychological distress.35

Continue to: Special populations

Special populations

HCV infection. Recurrent HCV infection and liver disease after transplantation are associated with psychological distress. This is particularly evident in patients 6 months after transplantation. Depression and psychological distress have been reported in male patients with recurrent HCV infection within the first year after transplantation.35

Acetaminophen overdose. Patients who receive a transplant for acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure (ALF) had a greater prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity as reflected by predefined diagnoses, medication, and previous suicide attempts.41 Despite this, outcomes for patients transplanted emergently for acetaminophen-induced ALF were comparable to those transplanted for non-acetaminophen-induced ALF and for chronic liver disease. Multidisciplinary approaches with long-term psychiatric follow-up may contribute to low post-transplant suicide rates and low rates of graft loss because of noncompliance.41

CASE REPORT

A complicated presentation

Ms. A, age 45, a married woman with history of chronic back pain and self-reported bipolar disorder, presented to our hospital with acute liver failure secondary to acetaminophen overdose. Her Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score on presentation was 38 (range: 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating increased likelihood of mortality). Her urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines and opiates. On hospital Day 2, the primary team consulted psychiatry for a pre-transplant evaluation and consideration of suicidality. Hepatology, toxicology, and transplant surgery services also were consulted.

Because Ms. A was intubated for acute respiratory failure, the initial history was gathered from family, a review of the medical record, consultation with her pharmacy, and collateral from her outpatient physician. Ms. A had been taking

Four days before presenting with acute liver failure, Ms. A had visited another hospital for lethargy. Benzodiazepines and opiates were stopped abruptly, and she was discharged with the recommendation to take acetaminophen for her pain. Approximately 24 hours after returning home, Ms. A began having auditory and visual hallucinations, and she did not sleep for days. She continued to complain of pain and was taking acetaminophen as recommended by the outside hospital. Her husband notes that she was intermittently confused. He was unsure how much acetaminophen she was taking.

Continue to: Her family noted...

Her family noted Ms. A had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder “years ago” but was unable to describe any manic episodes, and Ms. A had been treated only with an antidepressant from her primary care physician. She had persistent low mood and increased sleep since developing chronic back pain that severely limited her functioning. Ms. A attempted suicide once years ago by cutting her wrists. She had 2 prior psychiatric hospitalizations for suicidal ideation and the suicide attempt; however, she had not recently voiced suicidal ideation to her husband or family. She was adherent to psychotropic medications and follow-up appointments. Ms. A is a current smoker. She had used marijuana in the past, but her family denies current use, as well as any alcohol use or illicit substance use.

Ms. A’s diagnosis was consistent with tobacco use disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD). She likely developed withdrawal after abrupt cessation of diazepam, which she had been taking as prescribed for years. There was no evidence at the time of her initial psychiatric evaluation that the acetaminophen overdose was a suicide attempt; however, because Ms. A was intubated and sedated at that time, the consultation team recommended direct observation until she could participate in a risk assessment.

For the pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation, our consultation-liaison team noted Ms. A’s history of MDD, with recent active symptoms, chronic pain, and a past suicide attempt. She was a current tobacco smoker, which increases the risk of post-transplant vascular problems. However, she had been adherent to medications and follow-up, had very close family support, and there was no clear evidence that this acetaminophen ingestion was a suicide attempt. We noted that outpatient psychiatric follow-up and better chronic pain management would be helpful post-transplant. We would have to re-evaluate Ms. A when she was medically stable enough to communicate before making any further recommendations. Due to medical complications that developed after our evaluation, the transplant team noted Ms. A was no longer a transplant candidate.

Fortunately, Ms. A recovered with medical management over the next 2 weeks. She denied any suicidal ideation throughout her hospitalization. She was restarted on an antidepressant and received supportive therapy until discharge. Outpatient psychiatry follow-up and pain management was set up before Ms. A was discharged. Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization was not recommended. Per available records, Ms. A followed up with all outpatient appointments, including with her psychiatrist, since discharge.

Avoiding problems, maximizing outcomes

In addition to medical factors, psychosocial factors may affect the success of LT, although empirical data regarding which factors are most predictive of post-transplant outcomes is lacking, especially in patients with serious mental illness. The goals of a psychosocial pre-transplant evaluation are to promote fairness and equal access to care, maximize optimal outcomes, wisely use scarce resources, and ensure that the potential for benefits outweigh surgical risks to the patient. Identifying potential complicating factors (ie, substance abuse, nonadherence, serious psychopathology) can help guide the medical and psychiatric treatment plan and help minimize preventable problems both before and after transplant.42

Continue to: In patients who have...

In patients who have a history of alcohol use and alcohol liver disease, relapse to alcohol is a significant problem. Relapse rates vary from 10% to 30%.7 The duration of abstinence before LT appears to be a poor predictor of abstinence after LT.43 Polysubstance use also adversely affects outcomes in patients with alcohol liver disease. Approximately one-third of patients with polysubstance use who receive a LT relapse to substance use.44 Coffman et al45 showed that the presence of antisocial behavior and eating disorders may increase the risk of relapse after LT.

The psychiatrist’s role in the setting of LT spans from the pre-transplant assessment to post-transplant management and follow-up. Clarifying specific psychiatric diagnoses, psychosocial factors that need to be addressed before transplant, and substance use diagnoses and treatment recommendations can help the transplant team clearly identify modifiable factors that can affect transplant outcomes.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can help patients who are candidates for liver transplantation (LT) by performing a pre-transplant psychosocial assessment to identity factors that might complicate transplantation or recovery. After LT, patients require careful monitoring for psychiatric comorbidities, drug interactions, and other factors that can affect quality of life.

Related Resources

- Beresford TP, Lucey MR. Towards standardizing the alcoholism evaluation of potential liver transplant recipients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(2):135-144.

- Marcangelo MJ, Crone C. Tools, techniques to assess organ transplant candidates. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(9):56-66.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Diazepam • Valium

Hydromorphone • Dilaudid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Tacrolimus • Astagraf XL, Envarsus XR

1. Meirelles Júnior RF, Salvalaggio P, Rezende MB, et al. Liver transplantation: history, outcomes and perspectives [Article in English, Portuguese]. Einstein (São Paulo). 2015;13(1):149-152.

2. Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1144-1165.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. QuickStats: number of deaths from 10 leading causes,* by sex—National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(15):413.

4. Trieu JA, Bilal M, Hmoud B. Factors associated with waiting time on the liver transplant list: an analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31(1):84-89.

5. Neuberger J. An update on liver transplantation: a critical review. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:51-59.

6. Maldonado JR, Dubois HC, David EE, et al. The Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (SIPAT): a new tool for the psychosocial evaluation of pre-transplant candidates. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):123-132.

7. Grover S, Sarkar S. Liver transplant—psychiatric and psychosocial aspects. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2(4):382-392.

8. Burra P, Germani G, Gnoato F, et al. Adherence in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(7):760-770.

9. Lieber SR, Volk ML. Non-adherence and graft failure in adult liver transplant recipients. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(3):824-834.

10. Dobbels F, Vanhaecke J, Dupont L, et al. Pretransplant predictors of posttransplant adherence and clinical outcome: an evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screening. Transplantation. 2009;87(10):1497-1504.

11. De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(4):323.

12. Park DC, Hertzog C, Leventhal H, et al. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients: older is wiser. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(2):172-183.

13. Greenstein S, Siegal B. Compliance and noncompliance in patients with a functioning renal transplant: a multicenter study. Transplantation. 1998;66(12):1718-1726.