User login

This past week, I received “appointment reminder” text messages from two separate health care clinics requesting confirmation of my attendance—a practice that has become so commonplace, I didn’t think twice about it. But there was a time, not long ago, when this would’ve seemed like a scenario from the far-off future (like the flying cars on The Jetsons).

Times, they are a-changin’! Clinicians are becoming more electronically skilled and interested in connecting with patients in a more convenient, direct way. Accordingly, they are increasingly willing to embrace the world of social media—something health care institutions evaded for years and even discouraged employees from entering. Today, clinicians are starting to harness the potential of social media to increase health care awareness and improve access to care.

The popularity of social media has grown tremendously in recent years; 72% of US adults now use social media, up from 8% in 2005.1 Facebook—one of the most commonly used social networks, along with LinkedIn and Twitter—surpassed 1 billion users in the third quarter of 2012, making it the first to achieve this milestone.2

And that’s the beauty of social media: It’s a tool that’s all about speeding up and augmenting communication. Active users consider themselves part of a community and therefore tend to trust others within their social media “group.” As a result, patients—especially younger ones—are using social media to make health care decisions. They research and select their clinicians, hospitals, and even courses of treatment (for both themselves and their families) with input from this community.

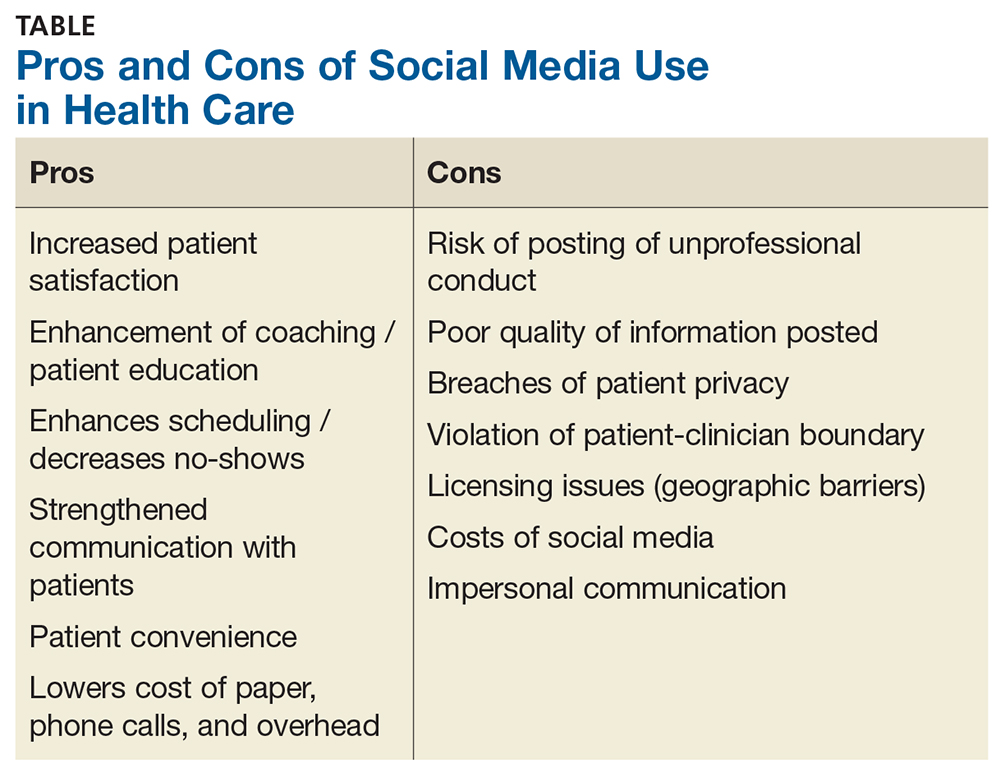

Our patients are social media–savvy and expect us, as clinicians, to be equally skilled. Are we missing an opportunity by opting out of these networks? Or are we rightly avoiding a number of thorny legal and regulatory issues by staying “offline”?

Many clinicians believe that the dependability of social media can drive better quality of care. In fact, 60% of physicians are in favor of interacting with patients on social media for patient education, health monitoring, medication adherence, and promotion of behavioral change.4 And in a 2012 study, 56% of patients reported wanting clinicians to use “social media” (which included email) to set appointments, report diagnostic test results, send prescription notifications, provide health information, and answer questions.5

Social media provides a platform for the public, patients, and health care professionals to communicate about health issues and (possibly) improve health outcomes. It can be used for professional networking, education, organizational promotion, patient care, patient education, and public health programs.6 So, where’s the downside?

As use of social media increases, particularly in the health care industry, the risks for legal implications and noncompliance also rise. Numerous federal and state rules and regulations govern communication within the health care industry. One of the main challenges health care organizations face is the protection of the privacy of patient information (ie, HIPAA). To this end, organizations must exhibit that they are managing the activities of employees who have access to patient information (which includes social media use). Institutions planning to use social media also need to ensure that their electronic records are complete, secure, and tamper-proof for record retention and audit purposes. Noncompliance with health care regulations can not only damage the reputation of an institution, it can also impact the bottom line.

In addition, health care providers must consider legal issues related to patient privacy, litigation, and licensing before using social media. Federal and state privacy laws limit providers’ ability to interact with patients through social media, because anything that can be used to identify a patient

It’s no wonder some providers are leery of connecting with patients via social media. Many of them, however, have tested the waters by using social networks to connect with colleagues and peers, often sharing medical knowledge and opinions this way.

As social media has evolved, medically focused professional communities have been established. One example is SERMO, a popular, private, physician-only social network. SERMO (www.sermo.com/what-is-sermo/overview) is a virtual doctors’ lounge with more than 800,000 verified and credentialed physician members; it includes physicians from 150 countries, with plans for continued expansion. Another, the Medical Directors Forum (https://medicaldirectorsforum.com/site), is a verified, secure, closed-loop environment for peer-to-peer interaction between medical directors, which features discussion groups, calendar postings, and alerts. Finally, Doximity (www.doximity.com/review) is a social network for physicians, NPs, and PAs, which allows clinicians to call patients (with the physician’s office number displayed on caller ID), review pertinent medical articles, communicate with colleagues, and even fax and/or email documents. Additionally, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), the American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA), and Clinician Reviews all have accounts on Facebook and Twitter, among other social media sites.

When it comes down to it, if used wisely, social media has the potential to promote individual and public health, as well as professional development and advancement. But carelessness can result in legal, ethical, and logistical issues, causing serious ramifications for the clinician—and possibly even the practice. So, which side of the social media debate are you on? Send your tips—or warnings—about integrating social media into your workplace to PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com

1. Antheunis ML, Tates K, Nieboer TE. Patients’ and health professionals’ use of social media in healthcare: motives, barriers, and expectations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):426-431.

2. Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horiz. 2010;53:59-68.

3. Statistica. Number of Facebook users worldwide as of 3rd quarter 2017 (in millions). www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/. Accessed November 16, 2017.

4. Househ M. The use of social media in healthcare: organizational, clinic, and patient perspectives. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;183:244-248.

5. Fisher J, Clayton M. Who gives a tweet: assessing patients’ interest in the use of social media for health care. Worldviews on Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9(2):100-108.

6. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499, 520.

This past week, I received “appointment reminder” text messages from two separate health care clinics requesting confirmation of my attendance—a practice that has become so commonplace, I didn’t think twice about it. But there was a time, not long ago, when this would’ve seemed like a scenario from the far-off future (like the flying cars on The Jetsons).

Times, they are a-changin’! Clinicians are becoming more electronically skilled and interested in connecting with patients in a more convenient, direct way. Accordingly, they are increasingly willing to embrace the world of social media—something health care institutions evaded for years and even discouraged employees from entering. Today, clinicians are starting to harness the potential of social media to increase health care awareness and improve access to care.

The popularity of social media has grown tremendously in recent years; 72% of US adults now use social media, up from 8% in 2005.1 Facebook—one of the most commonly used social networks, along with LinkedIn and Twitter—surpassed 1 billion users in the third quarter of 2012, making it the first to achieve this milestone.2

And that’s the beauty of social media: It’s a tool that’s all about speeding up and augmenting communication. Active users consider themselves part of a community and therefore tend to trust others within their social media “group.” As a result, patients—especially younger ones—are using social media to make health care decisions. They research and select their clinicians, hospitals, and even courses of treatment (for both themselves and their families) with input from this community.

Our patients are social media–savvy and expect us, as clinicians, to be equally skilled. Are we missing an opportunity by opting out of these networks? Or are we rightly avoiding a number of thorny legal and regulatory issues by staying “offline”?

Many clinicians believe that the dependability of social media can drive better quality of care. In fact, 60% of physicians are in favor of interacting with patients on social media for patient education, health monitoring, medication adherence, and promotion of behavioral change.4 And in a 2012 study, 56% of patients reported wanting clinicians to use “social media” (which included email) to set appointments, report diagnostic test results, send prescription notifications, provide health information, and answer questions.5

Social media provides a platform for the public, patients, and health care professionals to communicate about health issues and (possibly) improve health outcomes. It can be used for professional networking, education, organizational promotion, patient care, patient education, and public health programs.6 So, where’s the downside?

As use of social media increases, particularly in the health care industry, the risks for legal implications and noncompliance also rise. Numerous federal and state rules and regulations govern communication within the health care industry. One of the main challenges health care organizations face is the protection of the privacy of patient information (ie, HIPAA). To this end, organizations must exhibit that they are managing the activities of employees who have access to patient information (which includes social media use). Institutions planning to use social media also need to ensure that their electronic records are complete, secure, and tamper-proof for record retention and audit purposes. Noncompliance with health care regulations can not only damage the reputation of an institution, it can also impact the bottom line.

In addition, health care providers must consider legal issues related to patient privacy, litigation, and licensing before using social media. Federal and state privacy laws limit providers’ ability to interact with patients through social media, because anything that can be used to identify a patient

It’s no wonder some providers are leery of connecting with patients via social media. Many of them, however, have tested the waters by using social networks to connect with colleagues and peers, often sharing medical knowledge and opinions this way.

As social media has evolved, medically focused professional communities have been established. One example is SERMO, a popular, private, physician-only social network. SERMO (www.sermo.com/what-is-sermo/overview) is a virtual doctors’ lounge with more than 800,000 verified and credentialed physician members; it includes physicians from 150 countries, with plans for continued expansion. Another, the Medical Directors Forum (https://medicaldirectorsforum.com/site), is a verified, secure, closed-loop environment for peer-to-peer interaction between medical directors, which features discussion groups, calendar postings, and alerts. Finally, Doximity (www.doximity.com/review) is a social network for physicians, NPs, and PAs, which allows clinicians to call patients (with the physician’s office number displayed on caller ID), review pertinent medical articles, communicate with colleagues, and even fax and/or email documents. Additionally, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), the American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA), and Clinician Reviews all have accounts on Facebook and Twitter, among other social media sites.

When it comes down to it, if used wisely, social media has the potential to promote individual and public health, as well as professional development and advancement. But carelessness can result in legal, ethical, and logistical issues, causing serious ramifications for the clinician—and possibly even the practice. So, which side of the social media debate are you on? Send your tips—or warnings—about integrating social media into your workplace to PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com

This past week, I received “appointment reminder” text messages from two separate health care clinics requesting confirmation of my attendance—a practice that has become so commonplace, I didn’t think twice about it. But there was a time, not long ago, when this would’ve seemed like a scenario from the far-off future (like the flying cars on The Jetsons).

Times, they are a-changin’! Clinicians are becoming more electronically skilled and interested in connecting with patients in a more convenient, direct way. Accordingly, they are increasingly willing to embrace the world of social media—something health care institutions evaded for years and even discouraged employees from entering. Today, clinicians are starting to harness the potential of social media to increase health care awareness and improve access to care.

The popularity of social media has grown tremendously in recent years; 72% of US adults now use social media, up from 8% in 2005.1 Facebook—one of the most commonly used social networks, along with LinkedIn and Twitter—surpassed 1 billion users in the third quarter of 2012, making it the first to achieve this milestone.2

And that’s the beauty of social media: It’s a tool that’s all about speeding up and augmenting communication. Active users consider themselves part of a community and therefore tend to trust others within their social media “group.” As a result, patients—especially younger ones—are using social media to make health care decisions. They research and select their clinicians, hospitals, and even courses of treatment (for both themselves and their families) with input from this community.

Our patients are social media–savvy and expect us, as clinicians, to be equally skilled. Are we missing an opportunity by opting out of these networks? Or are we rightly avoiding a number of thorny legal and regulatory issues by staying “offline”?

Many clinicians believe that the dependability of social media can drive better quality of care. In fact, 60% of physicians are in favor of interacting with patients on social media for patient education, health monitoring, medication adherence, and promotion of behavioral change.4 And in a 2012 study, 56% of patients reported wanting clinicians to use “social media” (which included email) to set appointments, report diagnostic test results, send prescription notifications, provide health information, and answer questions.5

Social media provides a platform for the public, patients, and health care professionals to communicate about health issues and (possibly) improve health outcomes. It can be used for professional networking, education, organizational promotion, patient care, patient education, and public health programs.6 So, where’s the downside?

As use of social media increases, particularly in the health care industry, the risks for legal implications and noncompliance also rise. Numerous federal and state rules and regulations govern communication within the health care industry. One of the main challenges health care organizations face is the protection of the privacy of patient information (ie, HIPAA). To this end, organizations must exhibit that they are managing the activities of employees who have access to patient information (which includes social media use). Institutions planning to use social media also need to ensure that their electronic records are complete, secure, and tamper-proof for record retention and audit purposes. Noncompliance with health care regulations can not only damage the reputation of an institution, it can also impact the bottom line.

In addition, health care providers must consider legal issues related to patient privacy, litigation, and licensing before using social media. Federal and state privacy laws limit providers’ ability to interact with patients through social media, because anything that can be used to identify a patient

It’s no wonder some providers are leery of connecting with patients via social media. Many of them, however, have tested the waters by using social networks to connect with colleagues and peers, often sharing medical knowledge and opinions this way.

As social media has evolved, medically focused professional communities have been established. One example is SERMO, a popular, private, physician-only social network. SERMO (www.sermo.com/what-is-sermo/overview) is a virtual doctors’ lounge with more than 800,000 verified and credentialed physician members; it includes physicians from 150 countries, with plans for continued expansion. Another, the Medical Directors Forum (https://medicaldirectorsforum.com/site), is a verified, secure, closed-loop environment for peer-to-peer interaction between medical directors, which features discussion groups, calendar postings, and alerts. Finally, Doximity (www.doximity.com/review) is a social network for physicians, NPs, and PAs, which allows clinicians to call patients (with the physician’s office number displayed on caller ID), review pertinent medical articles, communicate with colleagues, and even fax and/or email documents. Additionally, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), the American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA), and Clinician Reviews all have accounts on Facebook and Twitter, among other social media sites.

When it comes down to it, if used wisely, social media has the potential to promote individual and public health, as well as professional development and advancement. But carelessness can result in legal, ethical, and logistical issues, causing serious ramifications for the clinician—and possibly even the practice. So, which side of the social media debate are you on? Send your tips—or warnings—about integrating social media into your workplace to PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com

1. Antheunis ML, Tates K, Nieboer TE. Patients’ and health professionals’ use of social media in healthcare: motives, barriers, and expectations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):426-431.

2. Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horiz. 2010;53:59-68.

3. Statistica. Number of Facebook users worldwide as of 3rd quarter 2017 (in millions). www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/. Accessed November 16, 2017.

4. Househ M. The use of social media in healthcare: organizational, clinic, and patient perspectives. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;183:244-248.

5. Fisher J, Clayton M. Who gives a tweet: assessing patients’ interest in the use of social media for health care. Worldviews on Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9(2):100-108.

6. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499, 520.

1. Antheunis ML, Tates K, Nieboer TE. Patients’ and health professionals’ use of social media in healthcare: motives, barriers, and expectations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):426-431.

2. Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horiz. 2010;53:59-68.

3. Statistica. Number of Facebook users worldwide as of 3rd quarter 2017 (in millions). www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/. Accessed November 16, 2017.

4. Househ M. The use of social media in healthcare: organizational, clinic, and patient perspectives. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;183:244-248.

5. Fisher J, Clayton M. Who gives a tweet: assessing patients’ interest in the use of social media for health care. Worldviews on Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9(2):100-108.

6. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499, 520.