User login

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

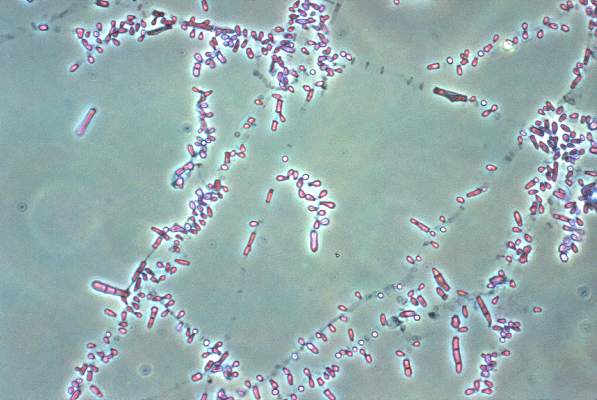

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD 2015