User login

Recently, I was talking with a colleague who works for a large hospital and health care system. While discussing his experiences over the past five years, he suddenly stopped and blurted out, “I don’t trust this organization. Nobody trusts this organization!”

Taken aback, I asked what made him say that.

First of all, he explained, there is a complete and pervasive lack of transparency as to both short- and long-term goals for the organization. Information is treated as proprietary thinking by nonclinical “corporate folks” and not released to the boots-on-the-ground clinician—which makes it difficult to work toward goals efficiently.

Furthermore, he related, there is consistent failure to provide accurate financial data or any plans to improve the organization’s financial position in the marketplace. This prevents providers from making a positive impact on cost containment. No one is invested. Provider compensation packages are neither universal nor simple. The financial folks devise complex formulas that do not account for the vagaries and complexities of health care. This health care organization views every patient as a Financial Information Number and makes no allowance for the fact that many have complex illnesses requiring significant time and attention.

Lastly, he described a systematic and insidious elimination of support staff at all levels—but particularly bedside nurses. The traditional “nursing safety net”—especially relevant in academic institutions—is in tatters, which threatens to undermine day-to-day success in patient care. Staffing of ancillary providers (those in physical, occupational, or speech-language therapy) has been cut back, which means patients wait longer to see these specialists and primary medical providers are frustrated by the lack of progress their patients make.

Stunned by his comments, I started thinking: How many of us recognize some or all of this description? How many trust the organization we work for? Realizing that a huge percentage of NPs, PAs, and physicians work for large entities, these are important questions.

Trust is central to human interaction on both personal and professional levels. Tschannen-Moran defines it as “one’s willingness to be vulnerable to another, based on the confidence that the other is benevolent, honest, open, reliable, and competent.”1

Continue to: A more focused definition of organizational trust

Organizational trust may require a broader and yet more focused definition—such as that of Cummings and Bromley, who stipulate that trust is a belief, held by an individual or groups of individuals, that another individual or group

- Makes a good faith effort to behave in accordance with any (explicit or implicit) commitments

- Is honest

- Does not take excessive advantage of another, even when the opportunity to do so exists.2

Thus, organizational (or collective) trust refers to the propensity of workgroups, administrators, and employees to trust others within the organization.

But does it really matter if we experience this kind of trust for our employer? Can’t we just show up and do our jobs? Frankly, no (at least, if we truly care about the work that we do).

Research has demonstrated that trust is a critical part of creating a shared vision; employees tend to help one another and work collaboratively when trust is present.3,4 Trust is also the foundation for flexibility and innovation.5 Employees are generally happier, more satisfied, and less stressed in high-trust organizations—and it has been shown that organizations benefit, too.6

By contrast, low-trust organizations usually create barriers to effective performance. In the absence of trust, people create rules and restrictions that mandate how others should act.4 Valuable time is then spent studying, enforcing, discussing, and rewriting rules. This yields low-flexibility results and leaves employees to simply follow and enforce policies. Another outcome is high transaction costs and less efficient work—meaning that processes become slower and more restricted by policies and paperwork.4 Low trust is also a barrier to change.7

Although we recognize organizational trust as an essential component of effective leadership, it remains an issue—one that can make or break an organization’s culture. Lack of trust, particularly between management and employees, creates a hostile work environment in which stress levels are high and productivity is reduced.

Continue to: Three dimensions of trust

There are three dimensions of trust, according to the Grunig Relationship Instrument:

Competence: The belief that an organization has the ability to do what it says it will do (this includes effectiveness and survivability in the marketplace).

Integrity: The belief that an organization is fair and just.

Dependability/reliability: The belief that an organization will do what it says it will do (ie, acts consistently and dependably).8

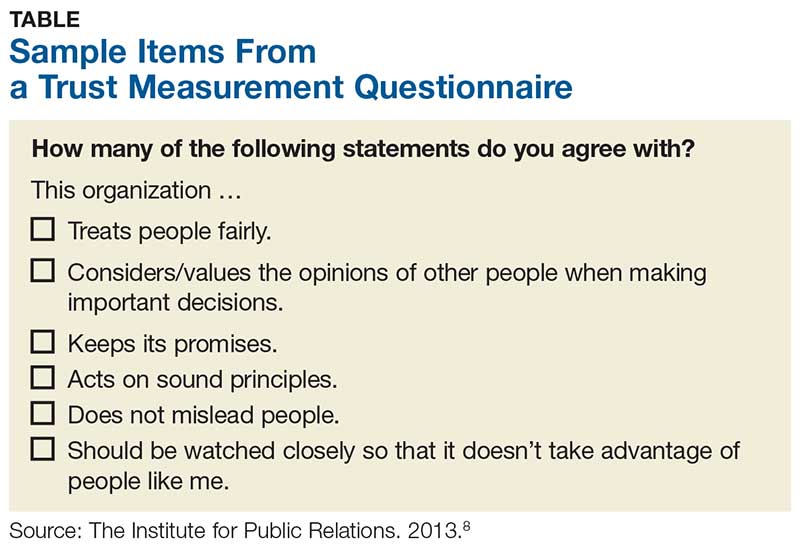

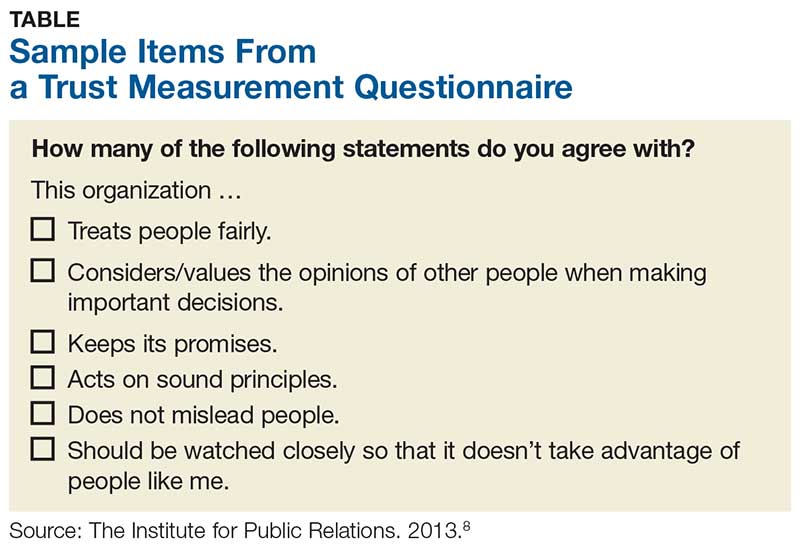

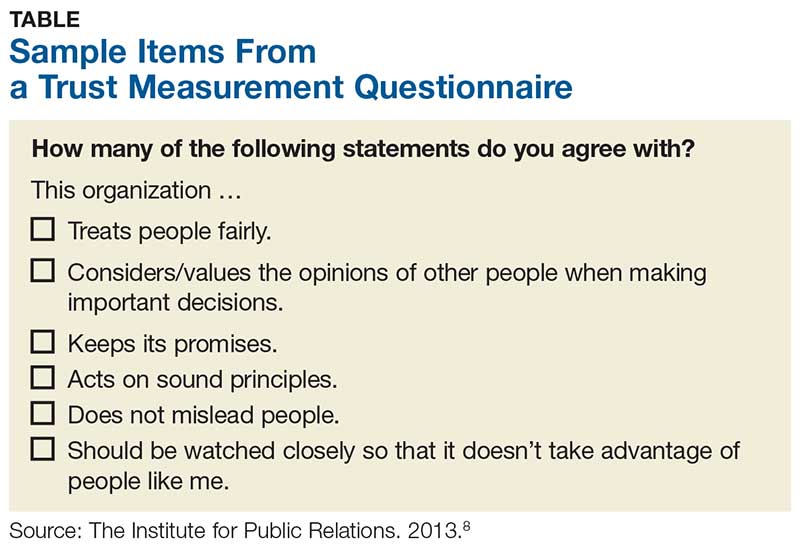

These concepts have been integrated into a “trust measurement questionnaire” that assists in the assessment of an organization’s trustworthiness. While this tool has been used in a variety of industries and has even been used to assess business-to-business relationships, some of the most relevant items for individual employees are outlined in the Table.8

But measuring trust is only effective if it leads to action. Once you’ve realized you don’t trust your employer, what should you do about it? Unfortunately, the answer is often “push for change or leave!” Aside from voicing your concerns or requesting more information (or leaving), the onus is really on the leaders of the organization to improve communication (among other things).

Continue to: 7 ways leaders can improve trust within their organization

According to Gleeson, there are seven ways leaders can improve trust within their organization, which include

- Having the right people in the right job, since trust must be demonstrated from top to bottom and vice versa

- Being transparent

- Sharing information with all vested parties, from industry partners to customers to employees

- Providing resources to all parties in an equitable manner

- Offering feedback to employees at all levels, perhaps through regular “status update” meetings

- Facing challenges head-on, using teamwork to promote trust and positive attitudes

- Leading by example—the organization’s values and mission should be exemplified by everyone.9

If we want to be leaders, not only within our professions but within our workplaces, we must nurture the ideas of trust, transparency, and communication. I am very interested in hearing from you about organizations that you feel are trustworthy and what makes them so—and what experiences you’ve had that led you to avoid or leave employment situations (you need not “name names,” of course). You can reach me at PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

1. Tschannen-Moran M. Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

2. Cummings LL, Bromley P. The organizational trust inventory (OTI): development and validation. In: Kramer R, Tyler E, eds. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996:302, 330, 429.

3. Roueche JE, Baker GA, Rose RR, eds. Shared Vision: Transformational Leadership in American Community Colleges. Washington, DC: American Association of Community and Junior Colleges; 1989.

4. Henkin AB, Dee JR. The power of trust: teams and collective action in self-managed schools. J School Leadership. 2001;11(1):48-62.

5. Dervitsiotis KN. Building trust for excellence in performance and adaptation to change. Total Qual Manage Bus Excellence. 2006;17(7):795-810.

6. Costa AC, Roe RA, Taillieu T. Trust within teams: the relation with performance effectiveness. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2001;10(3):225.

7. Kesler R, Perry C, Shay G. So they are resistant to change? Strategies for moving an immovable object. In: The Olympics of Leadership: Overcoming Obstacles, Balancing Skills, Taking Risks: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the National Community College Chair Academy (5th, Phoenix, Arizona, February 14-17, 1996). Mesa, AZ: National Community College Chair Academy; 1996.

8. The Institute for Public Relations Commission on PR Measurement and Evaluation, University of Florida. Guidelines for measuring trust in organizations. 2013. http://painepublishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Grunig-relationship-instrument.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2018.

9. Gleeson B. 7 ways leaders can improve trust within their organizations. Published June 24, 2015. Inc.com. www.inc.com/brent-gleeson/7-ways-leaders-can-improve-trust-within-their-organizations.html. Accessed March 13, 2018.

Recently, I was talking with a colleague who works for a large hospital and health care system. While discussing his experiences over the past five years, he suddenly stopped and blurted out, “I don’t trust this organization. Nobody trusts this organization!”

Taken aback, I asked what made him say that.

First of all, he explained, there is a complete and pervasive lack of transparency as to both short- and long-term goals for the organization. Information is treated as proprietary thinking by nonclinical “corporate folks” and not released to the boots-on-the-ground clinician—which makes it difficult to work toward goals efficiently.

Furthermore, he related, there is consistent failure to provide accurate financial data or any plans to improve the organization’s financial position in the marketplace. This prevents providers from making a positive impact on cost containment. No one is invested. Provider compensation packages are neither universal nor simple. The financial folks devise complex formulas that do not account for the vagaries and complexities of health care. This health care organization views every patient as a Financial Information Number and makes no allowance for the fact that many have complex illnesses requiring significant time and attention.

Lastly, he described a systematic and insidious elimination of support staff at all levels—but particularly bedside nurses. The traditional “nursing safety net”—especially relevant in academic institutions—is in tatters, which threatens to undermine day-to-day success in patient care. Staffing of ancillary providers (those in physical, occupational, or speech-language therapy) has been cut back, which means patients wait longer to see these specialists and primary medical providers are frustrated by the lack of progress their patients make.

Stunned by his comments, I started thinking: How many of us recognize some or all of this description? How many trust the organization we work for? Realizing that a huge percentage of NPs, PAs, and physicians work for large entities, these are important questions.

Trust is central to human interaction on both personal and professional levels. Tschannen-Moran defines it as “one’s willingness to be vulnerable to another, based on the confidence that the other is benevolent, honest, open, reliable, and competent.”1

Continue to: A more focused definition of organizational trust

Organizational trust may require a broader and yet more focused definition—such as that of Cummings and Bromley, who stipulate that trust is a belief, held by an individual or groups of individuals, that another individual or group

- Makes a good faith effort to behave in accordance with any (explicit or implicit) commitments

- Is honest

- Does not take excessive advantage of another, even when the opportunity to do so exists.2

Thus, organizational (or collective) trust refers to the propensity of workgroups, administrators, and employees to trust others within the organization.

But does it really matter if we experience this kind of trust for our employer? Can’t we just show up and do our jobs? Frankly, no (at least, if we truly care about the work that we do).

Research has demonstrated that trust is a critical part of creating a shared vision; employees tend to help one another and work collaboratively when trust is present.3,4 Trust is also the foundation for flexibility and innovation.5 Employees are generally happier, more satisfied, and less stressed in high-trust organizations—and it has been shown that organizations benefit, too.6

By contrast, low-trust organizations usually create barriers to effective performance. In the absence of trust, people create rules and restrictions that mandate how others should act.4 Valuable time is then spent studying, enforcing, discussing, and rewriting rules. This yields low-flexibility results and leaves employees to simply follow and enforce policies. Another outcome is high transaction costs and less efficient work—meaning that processes become slower and more restricted by policies and paperwork.4 Low trust is also a barrier to change.7

Although we recognize organizational trust as an essential component of effective leadership, it remains an issue—one that can make or break an organization’s culture. Lack of trust, particularly between management and employees, creates a hostile work environment in which stress levels are high and productivity is reduced.

Continue to: Three dimensions of trust

There are three dimensions of trust, according to the Grunig Relationship Instrument:

Competence: The belief that an organization has the ability to do what it says it will do (this includes effectiveness and survivability in the marketplace).

Integrity: The belief that an organization is fair and just.

Dependability/reliability: The belief that an organization will do what it says it will do (ie, acts consistently and dependably).8

These concepts have been integrated into a “trust measurement questionnaire” that assists in the assessment of an organization’s trustworthiness. While this tool has been used in a variety of industries and has even been used to assess business-to-business relationships, some of the most relevant items for individual employees are outlined in the Table.8

But measuring trust is only effective if it leads to action. Once you’ve realized you don’t trust your employer, what should you do about it? Unfortunately, the answer is often “push for change or leave!” Aside from voicing your concerns or requesting more information (or leaving), the onus is really on the leaders of the organization to improve communication (among other things).

Continue to: 7 ways leaders can improve trust within their organization

According to Gleeson, there are seven ways leaders can improve trust within their organization, which include

- Having the right people in the right job, since trust must be demonstrated from top to bottom and vice versa

- Being transparent

- Sharing information with all vested parties, from industry partners to customers to employees

- Providing resources to all parties in an equitable manner

- Offering feedback to employees at all levels, perhaps through regular “status update” meetings

- Facing challenges head-on, using teamwork to promote trust and positive attitudes

- Leading by example—the organization’s values and mission should be exemplified by everyone.9

If we want to be leaders, not only within our professions but within our workplaces, we must nurture the ideas of trust, transparency, and communication. I am very interested in hearing from you about organizations that you feel are trustworthy and what makes them so—and what experiences you’ve had that led you to avoid or leave employment situations (you need not “name names,” of course). You can reach me at PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

Recently, I was talking with a colleague who works for a large hospital and health care system. While discussing his experiences over the past five years, he suddenly stopped and blurted out, “I don’t trust this organization. Nobody trusts this organization!”

Taken aback, I asked what made him say that.

First of all, he explained, there is a complete and pervasive lack of transparency as to both short- and long-term goals for the organization. Information is treated as proprietary thinking by nonclinical “corporate folks” and not released to the boots-on-the-ground clinician—which makes it difficult to work toward goals efficiently.

Furthermore, he related, there is consistent failure to provide accurate financial data or any plans to improve the organization’s financial position in the marketplace. This prevents providers from making a positive impact on cost containment. No one is invested. Provider compensation packages are neither universal nor simple. The financial folks devise complex formulas that do not account for the vagaries and complexities of health care. This health care organization views every patient as a Financial Information Number and makes no allowance for the fact that many have complex illnesses requiring significant time and attention.

Lastly, he described a systematic and insidious elimination of support staff at all levels—but particularly bedside nurses. The traditional “nursing safety net”—especially relevant in academic institutions—is in tatters, which threatens to undermine day-to-day success in patient care. Staffing of ancillary providers (those in physical, occupational, or speech-language therapy) has been cut back, which means patients wait longer to see these specialists and primary medical providers are frustrated by the lack of progress their patients make.

Stunned by his comments, I started thinking: How many of us recognize some or all of this description? How many trust the organization we work for? Realizing that a huge percentage of NPs, PAs, and physicians work for large entities, these are important questions.

Trust is central to human interaction on both personal and professional levels. Tschannen-Moran defines it as “one’s willingness to be vulnerable to another, based on the confidence that the other is benevolent, honest, open, reliable, and competent.”1

Continue to: A more focused definition of organizational trust

Organizational trust may require a broader and yet more focused definition—such as that of Cummings and Bromley, who stipulate that trust is a belief, held by an individual or groups of individuals, that another individual or group

- Makes a good faith effort to behave in accordance with any (explicit or implicit) commitments

- Is honest

- Does not take excessive advantage of another, even when the opportunity to do so exists.2

Thus, organizational (or collective) trust refers to the propensity of workgroups, administrators, and employees to trust others within the organization.

But does it really matter if we experience this kind of trust for our employer? Can’t we just show up and do our jobs? Frankly, no (at least, if we truly care about the work that we do).

Research has demonstrated that trust is a critical part of creating a shared vision; employees tend to help one another and work collaboratively when trust is present.3,4 Trust is also the foundation for flexibility and innovation.5 Employees are generally happier, more satisfied, and less stressed in high-trust organizations—and it has been shown that organizations benefit, too.6

By contrast, low-trust organizations usually create barriers to effective performance. In the absence of trust, people create rules and restrictions that mandate how others should act.4 Valuable time is then spent studying, enforcing, discussing, and rewriting rules. This yields low-flexibility results and leaves employees to simply follow and enforce policies. Another outcome is high transaction costs and less efficient work—meaning that processes become slower and more restricted by policies and paperwork.4 Low trust is also a barrier to change.7

Although we recognize organizational trust as an essential component of effective leadership, it remains an issue—one that can make or break an organization’s culture. Lack of trust, particularly between management and employees, creates a hostile work environment in which stress levels are high and productivity is reduced.

Continue to: Three dimensions of trust

There are three dimensions of trust, according to the Grunig Relationship Instrument:

Competence: The belief that an organization has the ability to do what it says it will do (this includes effectiveness and survivability in the marketplace).

Integrity: The belief that an organization is fair and just.

Dependability/reliability: The belief that an organization will do what it says it will do (ie, acts consistently and dependably).8

These concepts have been integrated into a “trust measurement questionnaire” that assists in the assessment of an organization’s trustworthiness. While this tool has been used in a variety of industries and has even been used to assess business-to-business relationships, some of the most relevant items for individual employees are outlined in the Table.8

But measuring trust is only effective if it leads to action. Once you’ve realized you don’t trust your employer, what should you do about it? Unfortunately, the answer is often “push for change or leave!” Aside from voicing your concerns or requesting more information (or leaving), the onus is really on the leaders of the organization to improve communication (among other things).

Continue to: 7 ways leaders can improve trust within their organization

According to Gleeson, there are seven ways leaders can improve trust within their organization, which include

- Having the right people in the right job, since trust must be demonstrated from top to bottom and vice versa

- Being transparent

- Sharing information with all vested parties, from industry partners to customers to employees

- Providing resources to all parties in an equitable manner

- Offering feedback to employees at all levels, perhaps through regular “status update” meetings

- Facing challenges head-on, using teamwork to promote trust and positive attitudes

- Leading by example—the organization’s values and mission should be exemplified by everyone.9

If we want to be leaders, not only within our professions but within our workplaces, we must nurture the ideas of trust, transparency, and communication. I am very interested in hearing from you about organizations that you feel are trustworthy and what makes them so—and what experiences you’ve had that led you to avoid or leave employment situations (you need not “name names,” of course). You can reach me at PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

1. Tschannen-Moran M. Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

2. Cummings LL, Bromley P. The organizational trust inventory (OTI): development and validation. In: Kramer R, Tyler E, eds. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996:302, 330, 429.

3. Roueche JE, Baker GA, Rose RR, eds. Shared Vision: Transformational Leadership in American Community Colleges. Washington, DC: American Association of Community and Junior Colleges; 1989.

4. Henkin AB, Dee JR. The power of trust: teams and collective action in self-managed schools. J School Leadership. 2001;11(1):48-62.

5. Dervitsiotis KN. Building trust for excellence in performance and adaptation to change. Total Qual Manage Bus Excellence. 2006;17(7):795-810.

6. Costa AC, Roe RA, Taillieu T. Trust within teams: the relation with performance effectiveness. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2001;10(3):225.

7. Kesler R, Perry C, Shay G. So they are resistant to change? Strategies for moving an immovable object. In: The Olympics of Leadership: Overcoming Obstacles, Balancing Skills, Taking Risks: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the National Community College Chair Academy (5th, Phoenix, Arizona, February 14-17, 1996). Mesa, AZ: National Community College Chair Academy; 1996.

8. The Institute for Public Relations Commission on PR Measurement and Evaluation, University of Florida. Guidelines for measuring trust in organizations. 2013. http://painepublishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Grunig-relationship-instrument.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2018.

9. Gleeson B. 7 ways leaders can improve trust within their organizations. Published June 24, 2015. Inc.com. www.inc.com/brent-gleeson/7-ways-leaders-can-improve-trust-within-their-organizations.html. Accessed March 13, 2018.

1. Tschannen-Moran M. Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

2. Cummings LL, Bromley P. The organizational trust inventory (OTI): development and validation. In: Kramer R, Tyler E, eds. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996:302, 330, 429.

3. Roueche JE, Baker GA, Rose RR, eds. Shared Vision: Transformational Leadership in American Community Colleges. Washington, DC: American Association of Community and Junior Colleges; 1989.

4. Henkin AB, Dee JR. The power of trust: teams and collective action in self-managed schools. J School Leadership. 2001;11(1):48-62.

5. Dervitsiotis KN. Building trust for excellence in performance and adaptation to change. Total Qual Manage Bus Excellence. 2006;17(7):795-810.

6. Costa AC, Roe RA, Taillieu T. Trust within teams: the relation with performance effectiveness. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2001;10(3):225.

7. Kesler R, Perry C, Shay G. So they are resistant to change? Strategies for moving an immovable object. In: The Olympics of Leadership: Overcoming Obstacles, Balancing Skills, Taking Risks: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the National Community College Chair Academy (5th, Phoenix, Arizona, February 14-17, 1996). Mesa, AZ: National Community College Chair Academy; 1996.

8. The Institute for Public Relations Commission on PR Measurement and Evaluation, University of Florida. Guidelines for measuring trust in organizations. 2013. http://painepublishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Grunig-relationship-instrument.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2018.

9. Gleeson B. 7 ways leaders can improve trust within their organizations. Published June 24, 2015. Inc.com. www.inc.com/brent-gleeson/7-ways-leaders-can-improve-trust-within-their-organizations.html. Accessed March 13, 2018.