User login

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, and expert consensus points to clomiphene as first-line therapy.1

Under the conventional protocol, clomiphene is given early in the follicular phase, with midluteal monitoring for ovulation. If ovulation is not detected, progestin is administered to induce a withdrawal bleed, and the dosage of clomiphene is increased in the next cycle. Under this protocol, the clomiphene regimen can last as long as 90 days.

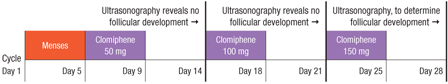

Hurst and colleagues propose a 28-day dosage-escalation method, relying on earlier ultrasonography to document follicular development and, in its absence, immediately “rechallenging” the patient with a higher dosage of clomiphene (FIGURE). They present intriguing data from a small, preliminary case series of 31 subjects who used this stair-step protocol. Seventy-four percent of these women ovulated by the end of the 28-day monitoring period, compared with 34% in 89 days among a historical control group using the traditional protocol.

Although a single stair-step cycle was more expensive than a traditional cycle, it has the potential to be less expensive when the rate of ovulation is taken into account.

FIGURE Stair-step clomiphene protocol skips progestin administration

Accelerated regimen may have a number of negatives

At first glance, what’s not to like about a protocol that increases the likelihood of ovulation with significant savings in time and cost for the patient?

First, there are methodologic concerns when a control group is not studied by means of a randomized, controlled trial—or even at the same center as the treatment arm—but is merely created from published data from a textbook.

Second, the goal of infertility therapy is live birth, not ovulation. Our studies have demonstrated significant differences in fecundity for each successful ovulation using different medications, suggesting that not every ovulation is the same.2 In the study by Hurst and colleagues, fecundity (live birth by ovulation rate) was 13%, compared with 10% using clomiphene in our large, multi-center trial—not much of an improvement, although, admittedly, the study by Hurst and colleagues was underpowered to address this question.2

Third, there are concerns about potential adverse effects of the accelerated clomiphene regimen on the patient or fetus. Clomiphene has a prolonged half-life of 5 to 7 days, with some metabolites persisting for months. What are the cumulative effects of such aggressive dosage escalation over such a short period of time?

The current Clomid package insert recommends a maximum dosage of 500 mg/cycle. A nonresponder in the stair-step protocol could consume 1,500 mg of clomiphene over a 20-day period.

Hurst and colleagues do not mention side effects, but it would be reasonable to expect an increased rate of hot flashes or mood changes. And what about more concerning signs such as visual changes?

Although clomiphene has no known human teratogenic effects (it is listed as pregnancy category “X”), the stair-step protocol could theoretically produce higher levels of fetal metabolites during the period of organ-ogenesis, with unknown effects.

Before we rush to adopt this accelerated regimen, we need studies that better address the maternal–fetal risk–benefit ratio. However, this study does provide evidence that a progestin withdrawal bleed is not mandatory in the nonresponder.—RICHARD S. LEGRO, MD

1. Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:505-522.

2. Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD. Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:551-566.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, and expert consensus points to clomiphene as first-line therapy.1

Under the conventional protocol, clomiphene is given early in the follicular phase, with midluteal monitoring for ovulation. If ovulation is not detected, progestin is administered to induce a withdrawal bleed, and the dosage of clomiphene is increased in the next cycle. Under this protocol, the clomiphene regimen can last as long as 90 days.

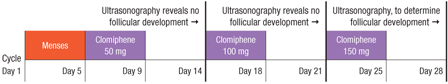

Hurst and colleagues propose a 28-day dosage-escalation method, relying on earlier ultrasonography to document follicular development and, in its absence, immediately “rechallenging” the patient with a higher dosage of clomiphene (FIGURE). They present intriguing data from a small, preliminary case series of 31 subjects who used this stair-step protocol. Seventy-four percent of these women ovulated by the end of the 28-day monitoring period, compared with 34% in 89 days among a historical control group using the traditional protocol.

Although a single stair-step cycle was more expensive than a traditional cycle, it has the potential to be less expensive when the rate of ovulation is taken into account.

FIGURE Stair-step clomiphene protocol skips progestin administration

Accelerated regimen may have a number of negatives

At first glance, what’s not to like about a protocol that increases the likelihood of ovulation with significant savings in time and cost for the patient?

First, there are methodologic concerns when a control group is not studied by means of a randomized, controlled trial—or even at the same center as the treatment arm—but is merely created from published data from a textbook.

Second, the goal of infertility therapy is live birth, not ovulation. Our studies have demonstrated significant differences in fecundity for each successful ovulation using different medications, suggesting that not every ovulation is the same.2 In the study by Hurst and colleagues, fecundity (live birth by ovulation rate) was 13%, compared with 10% using clomiphene in our large, multi-center trial—not much of an improvement, although, admittedly, the study by Hurst and colleagues was underpowered to address this question.2

Third, there are concerns about potential adverse effects of the accelerated clomiphene regimen on the patient or fetus. Clomiphene has a prolonged half-life of 5 to 7 days, with some metabolites persisting for months. What are the cumulative effects of such aggressive dosage escalation over such a short period of time?

The current Clomid package insert recommends a maximum dosage of 500 mg/cycle. A nonresponder in the stair-step protocol could consume 1,500 mg of clomiphene over a 20-day period.

Hurst and colleagues do not mention side effects, but it would be reasonable to expect an increased rate of hot flashes or mood changes. And what about more concerning signs such as visual changes?

Although clomiphene has no known human teratogenic effects (it is listed as pregnancy category “X”), the stair-step protocol could theoretically produce higher levels of fetal metabolites during the period of organ-ogenesis, with unknown effects.

Before we rush to adopt this accelerated regimen, we need studies that better address the maternal–fetal risk–benefit ratio. However, this study does provide evidence that a progestin withdrawal bleed is not mandatory in the nonresponder.—RICHARD S. LEGRO, MD

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, and expert consensus points to clomiphene as first-line therapy.1

Under the conventional protocol, clomiphene is given early in the follicular phase, with midluteal monitoring for ovulation. If ovulation is not detected, progestin is administered to induce a withdrawal bleed, and the dosage of clomiphene is increased in the next cycle. Under this protocol, the clomiphene regimen can last as long as 90 days.

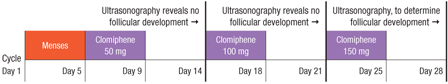

Hurst and colleagues propose a 28-day dosage-escalation method, relying on earlier ultrasonography to document follicular development and, in its absence, immediately “rechallenging” the patient with a higher dosage of clomiphene (FIGURE). They present intriguing data from a small, preliminary case series of 31 subjects who used this stair-step protocol. Seventy-four percent of these women ovulated by the end of the 28-day monitoring period, compared with 34% in 89 days among a historical control group using the traditional protocol.

Although a single stair-step cycle was more expensive than a traditional cycle, it has the potential to be less expensive when the rate of ovulation is taken into account.

FIGURE Stair-step clomiphene protocol skips progestin administration

Accelerated regimen may have a number of negatives

At first glance, what’s not to like about a protocol that increases the likelihood of ovulation with significant savings in time and cost for the patient?

First, there are methodologic concerns when a control group is not studied by means of a randomized, controlled trial—or even at the same center as the treatment arm—but is merely created from published data from a textbook.

Second, the goal of infertility therapy is live birth, not ovulation. Our studies have demonstrated significant differences in fecundity for each successful ovulation using different medications, suggesting that not every ovulation is the same.2 In the study by Hurst and colleagues, fecundity (live birth by ovulation rate) was 13%, compared with 10% using clomiphene in our large, multi-center trial—not much of an improvement, although, admittedly, the study by Hurst and colleagues was underpowered to address this question.2

Third, there are concerns about potential adverse effects of the accelerated clomiphene regimen on the patient or fetus. Clomiphene has a prolonged half-life of 5 to 7 days, with some metabolites persisting for months. What are the cumulative effects of such aggressive dosage escalation over such a short period of time?

The current Clomid package insert recommends a maximum dosage of 500 mg/cycle. A nonresponder in the stair-step protocol could consume 1,500 mg of clomiphene over a 20-day period.

Hurst and colleagues do not mention side effects, but it would be reasonable to expect an increased rate of hot flashes or mood changes. And what about more concerning signs such as visual changes?

Although clomiphene has no known human teratogenic effects (it is listed as pregnancy category “X”), the stair-step protocol could theoretically produce higher levels of fetal metabolites during the period of organ-ogenesis, with unknown effects.

Before we rush to adopt this accelerated regimen, we need studies that better address the maternal–fetal risk–benefit ratio. However, this study does provide evidence that a progestin withdrawal bleed is not mandatory in the nonresponder.—RICHARD S. LEGRO, MD

1. Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:505-522.

2. Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD. Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:551-566.

1. Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:505-522.

2. Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD. Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:551-566.