User login

Can ovulation induction be accelerated in women who have PCOS-related infertility?

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, and expert consensus points to clomiphene as first-line therapy.1

Under the conventional protocol, clomiphene is given early in the follicular phase, with midluteal monitoring for ovulation. If ovulation is not detected, progestin is administered to induce a withdrawal bleed, and the dosage of clomiphene is increased in the next cycle. Under this protocol, the clomiphene regimen can last as long as 90 days.

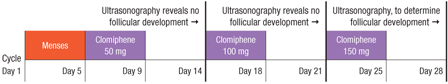

Hurst and colleagues propose a 28-day dosage-escalation method, relying on earlier ultrasonography to document follicular development and, in its absence, immediately “rechallenging” the patient with a higher dosage of clomiphene (FIGURE). They present intriguing data from a small, preliminary case series of 31 subjects who used this stair-step protocol. Seventy-four percent of these women ovulated by the end of the 28-day monitoring period, compared with 34% in 89 days among a historical control group using the traditional protocol.

Although a single stair-step cycle was more expensive than a traditional cycle, it has the potential to be less expensive when the rate of ovulation is taken into account.

FIGURE Stair-step clomiphene protocol skips progestin administration

Accelerated regimen may have a number of negatives

At first glance, what’s not to like about a protocol that increases the likelihood of ovulation with significant savings in time and cost for the patient?

First, there are methodologic concerns when a control group is not studied by means of a randomized, controlled trial—or even at the same center as the treatment arm—but is merely created from published data from a textbook.

Second, the goal of infertility therapy is live birth, not ovulation. Our studies have demonstrated significant differences in fecundity for each successful ovulation using different medications, suggesting that not every ovulation is the same.2 In the study by Hurst and colleagues, fecundity (live birth by ovulation rate) was 13%, compared with 10% using clomiphene in our large, multi-center trial—not much of an improvement, although, admittedly, the study by Hurst and colleagues was underpowered to address this question.2

Third, there are concerns about potential adverse effects of the accelerated clomiphene regimen on the patient or fetus. Clomiphene has a prolonged half-life of 5 to 7 days, with some metabolites persisting for months. What are the cumulative effects of such aggressive dosage escalation over such a short period of time?

The current Clomid package insert recommends a maximum dosage of 500 mg/cycle. A nonresponder in the stair-step protocol could consume 1,500 mg of clomiphene over a 20-day period.

Hurst and colleagues do not mention side effects, but it would be reasonable to expect an increased rate of hot flashes or mood changes. And what about more concerning signs such as visual changes?

Although clomiphene has no known human teratogenic effects (it is listed as pregnancy category “X”), the stair-step protocol could theoretically produce higher levels of fetal metabolites during the period of organ-ogenesis, with unknown effects.

Before we rush to adopt this accelerated regimen, we need studies that better address the maternal–fetal risk–benefit ratio. However, this study does provide evidence that a progestin withdrawal bleed is not mandatory in the nonresponder.—RICHARD S. LEGRO, MD

1. Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:505-522.

2. Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD. Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:551-566.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, and expert consensus points to clomiphene as first-line therapy.1

Under the conventional protocol, clomiphene is given early in the follicular phase, with midluteal monitoring for ovulation. If ovulation is not detected, progestin is administered to induce a withdrawal bleed, and the dosage of clomiphene is increased in the next cycle. Under this protocol, the clomiphene regimen can last as long as 90 days.

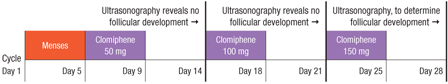

Hurst and colleagues propose a 28-day dosage-escalation method, relying on earlier ultrasonography to document follicular development and, in its absence, immediately “rechallenging” the patient with a higher dosage of clomiphene (FIGURE). They present intriguing data from a small, preliminary case series of 31 subjects who used this stair-step protocol. Seventy-four percent of these women ovulated by the end of the 28-day monitoring period, compared with 34% in 89 days among a historical control group using the traditional protocol.

Although a single stair-step cycle was more expensive than a traditional cycle, it has the potential to be less expensive when the rate of ovulation is taken into account.

FIGURE Stair-step clomiphene protocol skips progestin administration

Accelerated regimen may have a number of negatives

At first glance, what’s not to like about a protocol that increases the likelihood of ovulation with significant savings in time and cost for the patient?

First, there are methodologic concerns when a control group is not studied by means of a randomized, controlled trial—or even at the same center as the treatment arm—but is merely created from published data from a textbook.

Second, the goal of infertility therapy is live birth, not ovulation. Our studies have demonstrated significant differences in fecundity for each successful ovulation using different medications, suggesting that not every ovulation is the same.2 In the study by Hurst and colleagues, fecundity (live birth by ovulation rate) was 13%, compared with 10% using clomiphene in our large, multi-center trial—not much of an improvement, although, admittedly, the study by Hurst and colleagues was underpowered to address this question.2

Third, there are concerns about potential adverse effects of the accelerated clomiphene regimen on the patient or fetus. Clomiphene has a prolonged half-life of 5 to 7 days, with some metabolites persisting for months. What are the cumulative effects of such aggressive dosage escalation over such a short period of time?

The current Clomid package insert recommends a maximum dosage of 500 mg/cycle. A nonresponder in the stair-step protocol could consume 1,500 mg of clomiphene over a 20-day period.

Hurst and colleagues do not mention side effects, but it would be reasonable to expect an increased rate of hot flashes or mood changes. And what about more concerning signs such as visual changes?

Although clomiphene has no known human teratogenic effects (it is listed as pregnancy category “X”), the stair-step protocol could theoretically produce higher levels of fetal metabolites during the period of organ-ogenesis, with unknown effects.

Before we rush to adopt this accelerated regimen, we need studies that better address the maternal–fetal risk–benefit ratio. However, this study does provide evidence that a progestin withdrawal bleed is not mandatory in the nonresponder.—RICHARD S. LEGRO, MD

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, and expert consensus points to clomiphene as first-line therapy.1

Under the conventional protocol, clomiphene is given early in the follicular phase, with midluteal monitoring for ovulation. If ovulation is not detected, progestin is administered to induce a withdrawal bleed, and the dosage of clomiphene is increased in the next cycle. Under this protocol, the clomiphene regimen can last as long as 90 days.

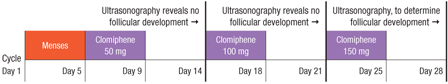

Hurst and colleagues propose a 28-day dosage-escalation method, relying on earlier ultrasonography to document follicular development and, in its absence, immediately “rechallenging” the patient with a higher dosage of clomiphene (FIGURE). They present intriguing data from a small, preliminary case series of 31 subjects who used this stair-step protocol. Seventy-four percent of these women ovulated by the end of the 28-day monitoring period, compared with 34% in 89 days among a historical control group using the traditional protocol.

Although a single stair-step cycle was more expensive than a traditional cycle, it has the potential to be less expensive when the rate of ovulation is taken into account.

FIGURE Stair-step clomiphene protocol skips progestin administration

Accelerated regimen may have a number of negatives

At first glance, what’s not to like about a protocol that increases the likelihood of ovulation with significant savings in time and cost for the patient?

First, there are methodologic concerns when a control group is not studied by means of a randomized, controlled trial—or even at the same center as the treatment arm—but is merely created from published data from a textbook.

Second, the goal of infertility therapy is live birth, not ovulation. Our studies have demonstrated significant differences in fecundity for each successful ovulation using different medications, suggesting that not every ovulation is the same.2 In the study by Hurst and colleagues, fecundity (live birth by ovulation rate) was 13%, compared with 10% using clomiphene in our large, multi-center trial—not much of an improvement, although, admittedly, the study by Hurst and colleagues was underpowered to address this question.2

Third, there are concerns about potential adverse effects of the accelerated clomiphene regimen on the patient or fetus. Clomiphene has a prolonged half-life of 5 to 7 days, with some metabolites persisting for months. What are the cumulative effects of such aggressive dosage escalation over such a short period of time?

The current Clomid package insert recommends a maximum dosage of 500 mg/cycle. A nonresponder in the stair-step protocol could consume 1,500 mg of clomiphene over a 20-day period.

Hurst and colleagues do not mention side effects, but it would be reasonable to expect an increased rate of hot flashes or mood changes. And what about more concerning signs such as visual changes?

Although clomiphene has no known human teratogenic effects (it is listed as pregnancy category “X”), the stair-step protocol could theoretically produce higher levels of fetal metabolites during the period of organ-ogenesis, with unknown effects.

Before we rush to adopt this accelerated regimen, we need studies that better address the maternal–fetal risk–benefit ratio. However, this study does provide evidence that a progestin withdrawal bleed is not mandatory in the nonresponder.—RICHARD S. LEGRO, MD

1. Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:505-522.

2. Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD. Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:551-566.

1. Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:505-522.

2. Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD. Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:551-566.

Q Should all obese women be screened for PCOS?

Expert Commentary

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is often accompanied by obesity, and the obesity epidemic appears to have been accompanied by a PCOS epidemic. Rather than focus on obesity’s effects on PCOS, Àlvarez-Blasco and colleagues looked for stigmata of PCOS in an unselected obese population.

Findings in line with earlier studies

This study adds credence to other investigations that have found women with a metabolic abnormality more likely than an unselected sample of the same population to have PCOS. Another study found a similar prevalence of PCOS—26.7%—among premenopausal women with type 2 diabetes.2

Obesity per se is associated with metabolic abnormalities, and the investigators showed an increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components with increasing obesity among the study cohort. The components of metabolic syndrome are:

- waist circumference >88 cm

- triglyceride level >150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol ≤50 mg/dL

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL

Strengths and weaknesses

The prospective design, size of the cohort, and full phenotyping performed on all subjects are strengths of this study.

The major weakness is the referral bias of a university-based endocrine clinic that is likely to attract women who are obese and also have endocrine abnormalities such as PCOS. (Endocrinology and nutrition are a single medical specialty in Spain.)

The best prevalence study of PCOS in the US general population involved asymptomatic women applying for employment at a university medical center.3 A similar study design and findings would strengthen the investigators’ recommendations to routinely screen for PCOS in an obese population.

This study did not use the revised Rotterdam criteria, which incorporate ultrasonographic size and morphology of the ovaries into the diagnosis. Preliminary studies show that these revised criteria tend to increase the prevalence of PCOS by about 50% among women with oligomenorrhea,4 so Álvarez-Blasco and colleagues likely underdetected PCOS by these criteria.

Bottom line: Screen obese patients for PCOS and metabolic syndrome

This study adds evidence of obesity’s adverse effects on reproduction, and suggests that routine screening of obese women for both PCOS and the metabolic syndrome is a high-yield procedure (25–30% for both).

1. Escobar-Morreale HF, Roldan B, Barrio R, et al. High prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome and hirsutism in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4182-4187.

2. Peppard HR, Marfori J, Iuorno MJ, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome among premenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1050-1052.

3. Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745-2749.

4. Broekmans FJ, Knauff EA, Valkenburg O, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC. PCOS according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria: change in prevalence among WHO-II anovulation and association with metabolic factors. BJOG. 2006;113:1210-1217.

Expert Commentary

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is often accompanied by obesity, and the obesity epidemic appears to have been accompanied by a PCOS epidemic. Rather than focus on obesity’s effects on PCOS, Àlvarez-Blasco and colleagues looked for stigmata of PCOS in an unselected obese population.

Findings in line with earlier studies

This study adds credence to other investigations that have found women with a metabolic abnormality more likely than an unselected sample of the same population to have PCOS. Another study found a similar prevalence of PCOS—26.7%—among premenopausal women with type 2 diabetes.2

Obesity per se is associated with metabolic abnormalities, and the investigators showed an increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components with increasing obesity among the study cohort. The components of metabolic syndrome are:

- waist circumference >88 cm

- triglyceride level >150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol ≤50 mg/dL

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL

Strengths and weaknesses

The prospective design, size of the cohort, and full phenotyping performed on all subjects are strengths of this study.

The major weakness is the referral bias of a university-based endocrine clinic that is likely to attract women who are obese and also have endocrine abnormalities such as PCOS. (Endocrinology and nutrition are a single medical specialty in Spain.)

The best prevalence study of PCOS in the US general population involved asymptomatic women applying for employment at a university medical center.3 A similar study design and findings would strengthen the investigators’ recommendations to routinely screen for PCOS in an obese population.

This study did not use the revised Rotterdam criteria, which incorporate ultrasonographic size and morphology of the ovaries into the diagnosis. Preliminary studies show that these revised criteria tend to increase the prevalence of PCOS by about 50% among women with oligomenorrhea,4 so Álvarez-Blasco and colleagues likely underdetected PCOS by these criteria.

Bottom line: Screen obese patients for PCOS and metabolic syndrome

This study adds evidence of obesity’s adverse effects on reproduction, and suggests that routine screening of obese women for both PCOS and the metabolic syndrome is a high-yield procedure (25–30% for both).

Expert Commentary

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is often accompanied by obesity, and the obesity epidemic appears to have been accompanied by a PCOS epidemic. Rather than focus on obesity’s effects on PCOS, Àlvarez-Blasco and colleagues looked for stigmata of PCOS in an unselected obese population.

Findings in line with earlier studies

This study adds credence to other investigations that have found women with a metabolic abnormality more likely than an unselected sample of the same population to have PCOS. Another study found a similar prevalence of PCOS—26.7%—among premenopausal women with type 2 diabetes.2

Obesity per se is associated with metabolic abnormalities, and the investigators showed an increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components with increasing obesity among the study cohort. The components of metabolic syndrome are:

- waist circumference >88 cm

- triglyceride level >150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol ≤50 mg/dL

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL

Strengths and weaknesses

The prospective design, size of the cohort, and full phenotyping performed on all subjects are strengths of this study.

The major weakness is the referral bias of a university-based endocrine clinic that is likely to attract women who are obese and also have endocrine abnormalities such as PCOS. (Endocrinology and nutrition are a single medical specialty in Spain.)

The best prevalence study of PCOS in the US general population involved asymptomatic women applying for employment at a university medical center.3 A similar study design and findings would strengthen the investigators’ recommendations to routinely screen for PCOS in an obese population.

This study did not use the revised Rotterdam criteria, which incorporate ultrasonographic size and morphology of the ovaries into the diagnosis. Preliminary studies show that these revised criteria tend to increase the prevalence of PCOS by about 50% among women with oligomenorrhea,4 so Álvarez-Blasco and colleagues likely underdetected PCOS by these criteria.

Bottom line: Screen obese patients for PCOS and metabolic syndrome

This study adds evidence of obesity’s adverse effects on reproduction, and suggests that routine screening of obese women for both PCOS and the metabolic syndrome is a high-yield procedure (25–30% for both).

1. Escobar-Morreale HF, Roldan B, Barrio R, et al. High prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome and hirsutism in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4182-4187.

2. Peppard HR, Marfori J, Iuorno MJ, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome among premenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1050-1052.

3. Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745-2749.

4. Broekmans FJ, Knauff EA, Valkenburg O, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC. PCOS according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria: change in prevalence among WHO-II anovulation and association with metabolic factors. BJOG. 2006;113:1210-1217.

1. Escobar-Morreale HF, Roldan B, Barrio R, et al. High prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome and hirsutism in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4182-4187.

2. Peppard HR, Marfori J, Iuorno MJ, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome among premenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1050-1052.

3. Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745-2749.

4. Broekmans FJ, Knauff EA, Valkenburg O, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC. PCOS according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria: change in prevalence among WHO-II anovulation and association with metabolic factors. BJOG. 2006;113:1210-1217.

Q Which drug is best for infertile PCOS patients—clomiphene or metformin?

Expert Commentary

While metaanalysis suggests metformin improves ovulatory frequency in women with PCOS, until now the question of whether it helps achieve and maintain pregnancy has been explored only in small trials. The superiority of metformin for primary treatment of PCOS-related anovulatory infertility over standard-of-care clomiphene citrate was a matter of speculation (partly because metformin therapy was often reserved for “clomiphene failure”).

Palomba et al are to be commended for their study design (double-dummy, double-blind, randomized controlled trial) and choice of pregnancy as the primary outcome—a quantum leap forward for clinical trials involving PCOS. They studied 100 nonobese (BMI

Twice the pregnancy rate

The pregnancy rate after 6 months was significantly higher in the metformin group (69%) than in the clomiphene group (34%), and the abortion rate was significantly lower with metformin (10% versus 38% for clomiphene). There also was a trend toward a better live birth rate with metformin (84% versus 56% with clomiphene).

Intriguingly, ovulation and fecundity rates improved progressively with metformin and were highest during the sixth month of treatment, whereas an opposite trend was noted with clomiphene.

Flaws may limit credibility

Several imperfections mark this trial. Although it was billed as double-dummy, the dummy used for both clomiphene and metformin was described as “polyvitamin tablets similar in appearance to metformin and/or CC.” A true dummy is identical in appearance to the medication; any suggestion that a medication is inactive will lead to unblinding, potentially biasing the results.

Another problem: 10% of metformin patients and 6% of clomiphene patients were excluded from the analyses, in some cases for vague reasons (eg, significant weight loss). An intention-to-treat analysis including all randomized patients would have been more appropriate, although pregnancy rates would have been lower.

Finally, this comparatively large sample size is not nearly large enough to detect a significant difference in the ultimate pregnancy goal: a live birth.

Metformin best in nonobese women

This study reinforces the use of metformin as first-line therapy for PCOS in nonobese women with anovulatory infertility. It is too soon to extrapolate results to an obese PCOS population, which is more characteristic of the United States.

Expert Commentary

While metaanalysis suggests metformin improves ovulatory frequency in women with PCOS, until now the question of whether it helps achieve and maintain pregnancy has been explored only in small trials. The superiority of metformin for primary treatment of PCOS-related anovulatory infertility over standard-of-care clomiphene citrate was a matter of speculation (partly because metformin therapy was often reserved for “clomiphene failure”).

Palomba et al are to be commended for their study design (double-dummy, double-blind, randomized controlled trial) and choice of pregnancy as the primary outcome—a quantum leap forward for clinical trials involving PCOS. They studied 100 nonobese (BMI

Twice the pregnancy rate

The pregnancy rate after 6 months was significantly higher in the metformin group (69%) than in the clomiphene group (34%), and the abortion rate was significantly lower with metformin (10% versus 38% for clomiphene). There also was a trend toward a better live birth rate with metformin (84% versus 56% with clomiphene).

Intriguingly, ovulation and fecundity rates improved progressively with metformin and were highest during the sixth month of treatment, whereas an opposite trend was noted with clomiphene.

Flaws may limit credibility

Several imperfections mark this trial. Although it was billed as double-dummy, the dummy used for both clomiphene and metformin was described as “polyvitamin tablets similar in appearance to metformin and/or CC.” A true dummy is identical in appearance to the medication; any suggestion that a medication is inactive will lead to unblinding, potentially biasing the results.

Another problem: 10% of metformin patients and 6% of clomiphene patients were excluded from the analyses, in some cases for vague reasons (eg, significant weight loss). An intention-to-treat analysis including all randomized patients would have been more appropriate, although pregnancy rates would have been lower.

Finally, this comparatively large sample size is not nearly large enough to detect a significant difference in the ultimate pregnancy goal: a live birth.

Metformin best in nonobese women

This study reinforces the use of metformin as first-line therapy for PCOS in nonobese women with anovulatory infertility. It is too soon to extrapolate results to an obese PCOS population, which is more characteristic of the United States.

Expert Commentary

While metaanalysis suggests metformin improves ovulatory frequency in women with PCOS, until now the question of whether it helps achieve and maintain pregnancy has been explored only in small trials. The superiority of metformin for primary treatment of PCOS-related anovulatory infertility over standard-of-care clomiphene citrate was a matter of speculation (partly because metformin therapy was often reserved for “clomiphene failure”).

Palomba et al are to be commended for their study design (double-dummy, double-blind, randomized controlled trial) and choice of pregnancy as the primary outcome—a quantum leap forward for clinical trials involving PCOS. They studied 100 nonobese (BMI

Twice the pregnancy rate

The pregnancy rate after 6 months was significantly higher in the metformin group (69%) than in the clomiphene group (34%), and the abortion rate was significantly lower with metformin (10% versus 38% for clomiphene). There also was a trend toward a better live birth rate with metformin (84% versus 56% with clomiphene).

Intriguingly, ovulation and fecundity rates improved progressively with metformin and were highest during the sixth month of treatment, whereas an opposite trend was noted with clomiphene.

Flaws may limit credibility

Several imperfections mark this trial. Although it was billed as double-dummy, the dummy used for both clomiphene and metformin was described as “polyvitamin tablets similar in appearance to metformin and/or CC.” A true dummy is identical in appearance to the medication; any suggestion that a medication is inactive will lead to unblinding, potentially biasing the results.

Another problem: 10% of metformin patients and 6% of clomiphene patients were excluded from the analyses, in some cases for vague reasons (eg, significant weight loss). An intention-to-treat analysis including all randomized patients would have been more appropriate, although pregnancy rates would have been lower.

Finally, this comparatively large sample size is not nearly large enough to detect a significant difference in the ultimate pregnancy goal: a live birth.

Metformin best in nonobese women

This study reinforces the use of metformin as first-line therapy for PCOS in nonobese women with anovulatory infertility. It is too soon to extrapolate results to an obese PCOS population, which is more characteristic of the United States.