User login

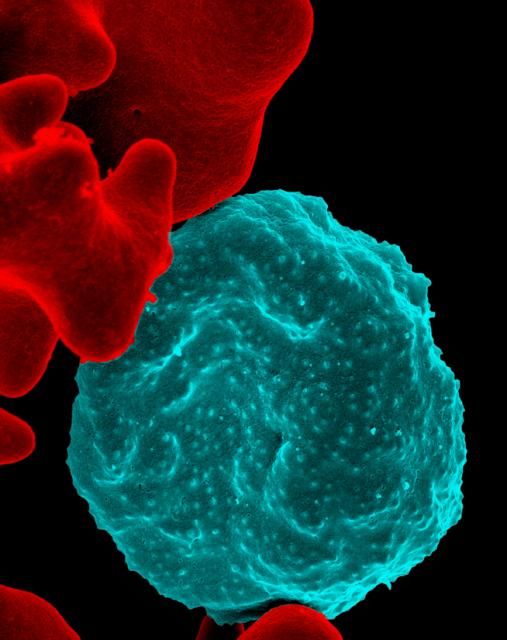

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.