User login

Mohs Micrographic Surgery for Digital Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

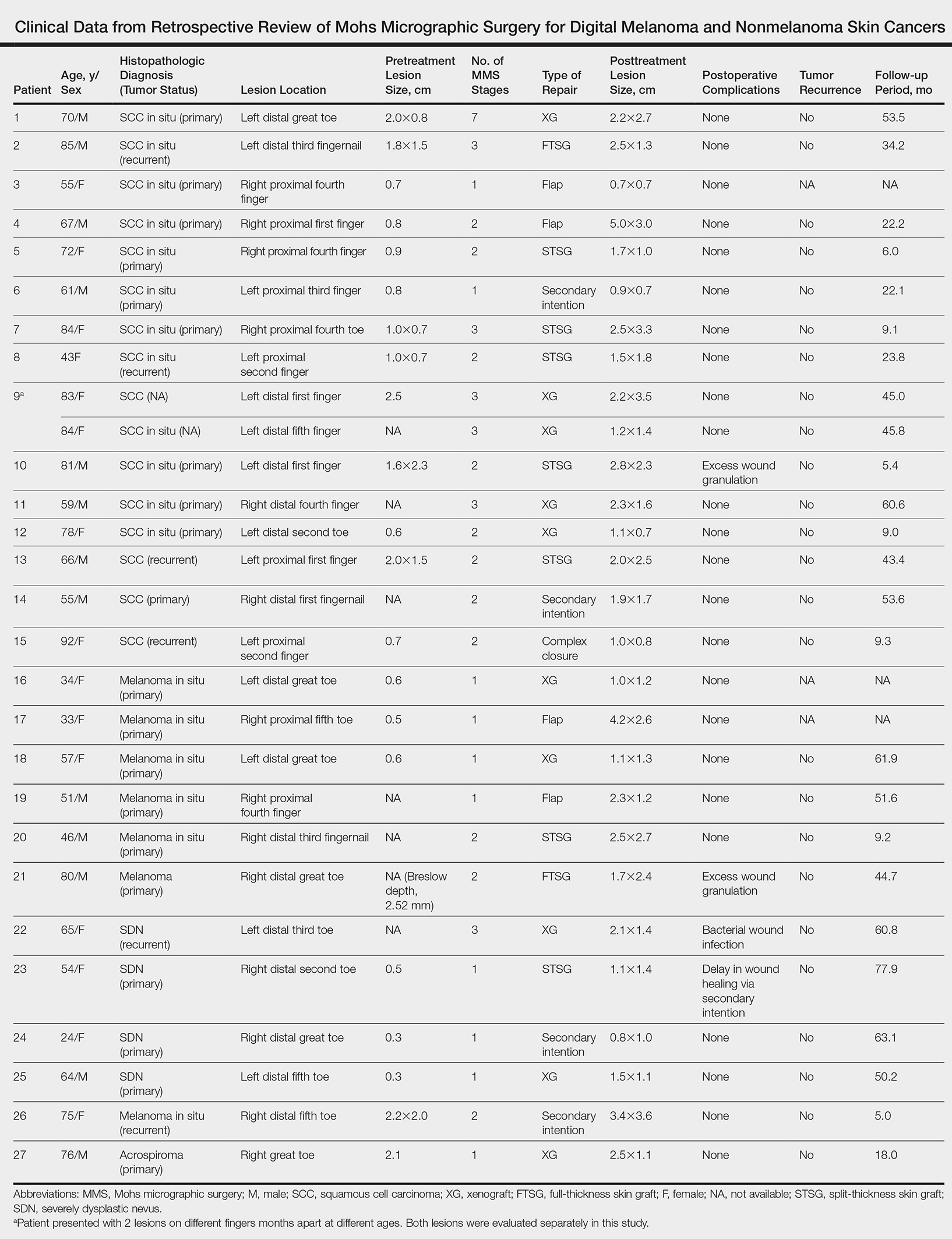

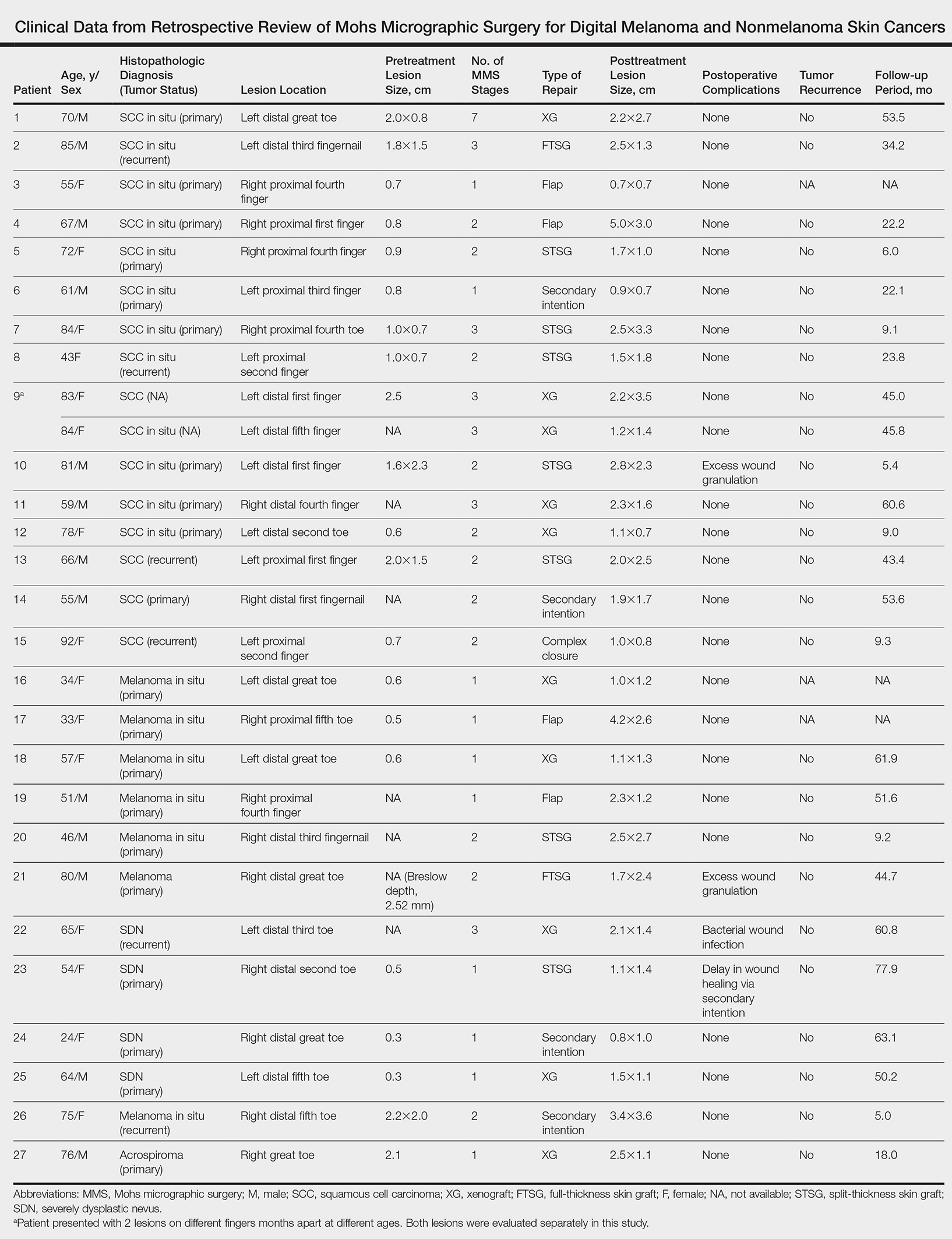

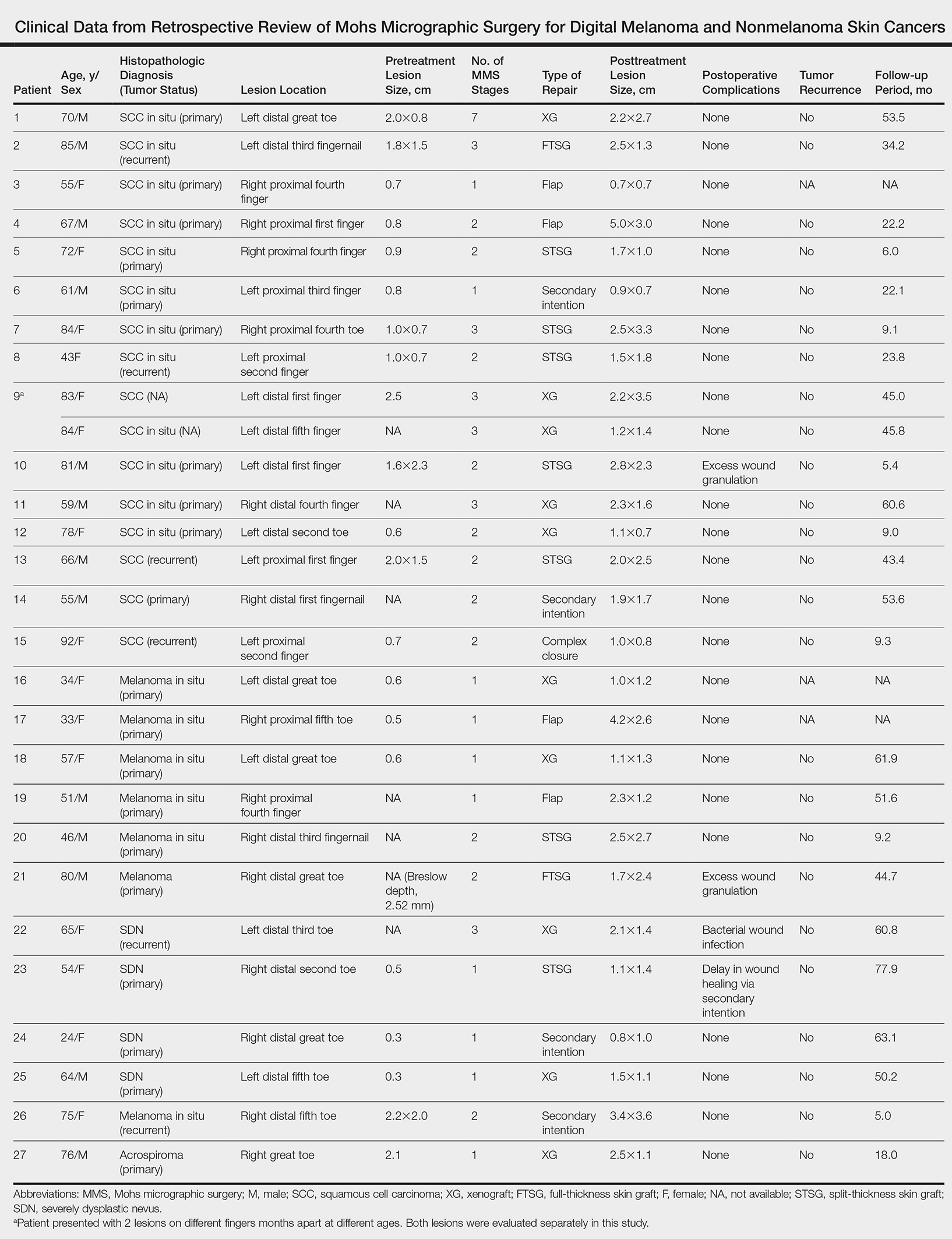

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

Practice Points

- Melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers of the digits traditionally have been treated with wide local surgical excision and even amputation.

- Conservative tissue sparing techniques such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be used to treat digital skin cancers with high cure rates and improved functional and cosmetic results.

Management of Poorly Controlled Indolent Systemic Mastocytosis Using Narrowband UVB Phototherapy

Systemic mastocytosis is a heterogeneous disorder of stem cell origin defined by abnormal hyperplasia and accumulation of mast cells (MCs) in one or more tissues.1,2 The most commonly affected tissues are the bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. Based on a number of major and minor criteria defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), the mastocytoses are subdivided into 7 variants that range from isolated cutaneous involvement to widespread systemic disease.1-4 The most frequently diagnosed subtype is indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM), a chronic disorder characterized by diffuse cutaneous macules and papules as well as bone marrow involvement in the form of multifocal dense infiltrates of MCs that frequently are phenotypically positive for c-KIT and tryptase. Serum tryptase levels are nearly invariably elevated in patients with this condition.1,2

Symptoms of ISM are determined by the intermittent release of histamine and leukotrienes from hyperproliferating MCs as well as IL-6 and eosinophil chemotactic factors. As the burden of MC secretory products increases, patients experience worsening pruritus, flushing, palpitations, vomiting, and anaphylaxis in severe instances.1,2,5 The mainstay of treatment of this condition involves symptom control through the inhibition of MC mediators.1 The majority of patients respond well to antihistamines, antileukotriene agents, and oral corticosteroids during severe episodes of MC degranulation.1,2,5

Unfortunately, some patients are unable to achieve adequate symptom control through the use of mediator-targeting treatments alone. In these cases, physicians often are faced with the following treatment dilemma: Either attempt to use therapies such as interferon alfa, which is cytoreductive to MCs, or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine to reduce the overall MC burden, or turn to newer nonimmunosuppressive second-line options. We present the case of a patient with chronic ISM with progressive cutaneous lesions and poorly controlled pruritus that was previously managed with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines who responded favorably to treatment with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy.

Case Report

A 57-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of widespread red-brown macules and papules on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. The lesions were intermittently pruritic, a symptom that was exacerbated on sun and heat exposure. A skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 9 years prior confirmed the presence of mastocytosis. The patient was originally treated with triamcinolone cream and oral antihistamines, which controlled her symptoms successfully for nearly a decade.

At the current presentation, the patient reported increasingly severe pruritus and lesional spread to the neck and face of 15 months’ duration. She denied any symptoms of flushing, diarrhea, syncopal episodes, or lightheadedness. Physical examination revealed a well-appearing middle-aged woman with multiple 3- to 8-mm, red-brown, blanchable macules and papules with areas coalescing into plaques that primarily involved the legs (Figure 1A); arms; back; and to a lesser extent the abdomen, neck, and face. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory results revealed a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic profile within reference range; however, the serum tryptase level was elevated at 65 ng/mL (reference range, <11.4 ng/mL). A positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan was negative, as well as a c-KIT mutation analysis. A review of the skin biopsy from 9 years prior demonstrated slight acanthosis with dermal proliferation of mononuclear cells (Figure 2A), some of which had abundant cytoplasm and oval-shaped nuclei. There were few eosinophils and marked dermal telangiectasias. Giemsa stain revealed increased numbers of MCs in the upper dermis (Figure 2B). A bone marrow biopsy performed 9 years later showed multifocal lesions composed of MCs with associated lymphoid aggregates without notable myelodyspoiesis (or myeloproliferative neoplasm). These features were all consistent with WHO criteria for ISM. Based on the most current clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with category IB ISM.

The patient’s symptoms had remained stable for 9 years with a regimen of triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, doxepin cream 5% daily as needed, and oral fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient continues to use topical steroids and oral antihistamines. Due to inadequate symptom control, breakthrough pruritus, and the development of new skin lesions on the head and neck, she was started on NB-UVB treatment 2 months after presentation. The patient’s symptoms and the extent of cutaneous maculopapular lesions improved after 20 light treatments (Figure 1B), with even more dramatic results after 40 cycles of therapy (Figure 1C). Overall, the lower legs have proved most recalcitrant to this treatment modality. She is currently continuing to receive NB-UVB treatment twice weekly.

Comment

Systemic mastocytosis is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by the proliferation and accumulation of atypical MCs in tissues, principally in the bone marrow and skin, though involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymphatic system also have been reported.1,2,6 The WHO classification of mastocytosis divides this condition into 7 subtypes.4 Indolent systemic mastocytosis is the most common variant.2,6 The etiology of ISM is not fully understood, but there is evidence suggesting that an activating mutation of KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase, KIT (usually D816V), present in the MCs of nearly 80% of patients with ISM may be involved.1,3-5,7 Patients occasionally present with predominantly cutaneous findings but typically seek medical attention due to the recurrent systemic symptoms of the disease (eg, pruritus, flushing, syncope, palpitations, headache, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), which are related to the release of MC mediators.1,2

The management of ISM is complex and based primarily on symptom reduction without alteration of disease course.1,2,5,7 Patients should avoid symptom triggers such as heat, humidity, emotional and physical stress, alcohol, and certain medications (ie, aspirin, opioids, radiocontrast agents).7 Patients are initially treated with histamine H1- and H2-receptor antagonists to alleviate MC mediator release symptoms.1,2,8 Although H1 blockers are most effective in mitigating cutaneous symptoms and limiting pruritus, H2 blockers are used to control gastric hypersecretion and dyspepsia.2 Proton pump inhibitors are useful in patients with peptic ulcer disease who are unresponsive to H2-receptor antagonist therapy.2,7 Cromolyn sodium and ketotifen fumarate are MC stabilizers that help prevent degranulation, which is helpful in relieving most major ISM symptoms. Leukotriene antagonists, such as zafirlukast, montelukast sodium, or zileuton, also may be employed to target the proinflammatory and pruritogenic leukotrienes, also products of the MC protein.2,7 Imatinib mesylate and masitinib mesylate, both tyrosine kinase inhibitors, have been shown to improve symptoms and reduce MC mediator levels in ISM; however, most patients harbor the resistant KIT D816V mutation, which limits the utility of this medication.Patients with sensitive KIT mutations or those who have the wild-type KIT D816 mutation may be more appropriate candidates for imatinib or masitinib therapy, which can ameliorate symptoms of flushing, pruritus, and depression.7-10 Treatment with omalizumab, a humanized murine anti-IgE monoclonal antibody, can be effective in treating recurrent, treatment-refractory anaphylaxis in ISM patients.5,7

Symptoms unresponsive to these therapies can be effectively treated with a short course of oral corticosteroids,6,7 while MC cytoreductive therapies such as interferon alfa or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (cladribine/2-CdA) are reserved for refractory cases.2,7 Alternative therapies such as NB-UVB2 or psoralen plus UVA phototherapy11 also have demonstrated success in treating ISM symptoms. In the past, NB-UVB has shown efficacy in controlling pruriginous conditions ranging from chronic urticaria12,13 to atopic dermatitis14 to psoriasis.15 This evidence has spurred studies to evaluate if NB-UVB has a role in the management of uncontrolled cases of cutaneous and ISM.2,13,16,17 To date, the evidence has been promising. The majority of patients treated with this regimen report subjective reduction in pruritus in addition to clinical cutaneous disease burden.2,11 Also, laboratory analysis demonstrates decreased levels of tryptase in patients utilizing NB-UVB phototherapy.2 Thus far, the use of NB-UVB phototherapy in the treatment of pruriginous disorders such as ISM has not been associated with any severe side effects such as increased rates of anaphylaxis, though some research has suggested that this therapy may lower the threshold for patients to develop symptomatic dermographism.12 Overall, patients treated with NB-UVB phototherapy report improved quality of life related to more effective symptom control.16

Although ISM is currently considered an incurable chronic condition,6 this case illustrates that symptomatic management is possible, even in cases of long-standing, severe disease. Patients should still be encouraged to avoid triggering factors and be vigilant in preventing potential anaphylaxis. However, NB-UVB phototherapy provides a supplemental or alternative treatment choice when other therapies have failed. We hope that the success of NB-UVB demonstrated in this case provides further evidence that this light-based therapy is a valuable treatment option in mastocytosis patients with unremitting or poorly controlled symptoms.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier; 2012.

- Brazzelli V, Grasso V, Manna G, et al. Indolent systemic mastocytosis treated with narrow-band UVB phototherapy: study of five cases [published online May 13, 2011]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:465-469.

- Pardanani A, Lim KH, Lasho TL, et al. WHO subvariants of indolent mastocytosis: clinical details and prognostic evaluation in 159 consecutive adults. Blood. 2010;115:150-151.

- Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes [published online April 8, 2009]. Blood. 2009;114:937-951.

- Wolff K, Komar M, Petzelbauer P. Clinical and histopathological aspects of cutaneous mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:519-528.

- Marone G, Spadaro G, Granata F, et al. Treatment of mastocytosis: pharmacologic basis and current concepts. Leuk Res. 2001;25:583-594.

- Pardanani A. How I treat patients with indolent and smoldering mastocytosis (rare conditions but difficult to manage)[published online February 20, 2013]. Blood. 2013;121:3085-3094.

- Hartmann K, Henz BM. Mastocytosis: recent advances in defining the disease. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:682-695.

- Vega-Ruiz A, Cortes JE, Sever M, et al. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate as therapy for patients with systemic mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1481-1484.

- Lortholary O, Chandesris MO, Bulai Livideanu C, et al. Masitinib for treatment of severely symptomatic indolent systemic mastocytosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389:612-620.

- Godt O, Proksch E, Streit V, et al. Short-and long-term effectiveness of oral and bath PUVA therapy in urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. Dermatology. 1997;1:35-39.

- Berroeta L, Clark C, Ibbotson SH, et al. Narrow-band (TL-01) ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:91-99.

- Engin B, Ozdemir M, Balevi A, et al. Treatment of chronic urticaria with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;3:247-251.

- Meduri NB, Vandergriff T, Rasmussen H, et al. Phototherapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systemic review. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:106-112.

- Nguyen T, Gattu S, Pugashetti R, et al. Practice of phototherapy in the treatment of moderate-to severe psoriasis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2009;38:59-78.

- Brazzelli V, Grassi S, Merante S, et al. Narrow-band UVB phototherapy and psoralen-ultraviolet A photochemotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous mastocytosis: a study in 20 patients. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2016;32:238-246.

- Prignano F, Troiano M, Lotti T. Cutaneous mastocytosis: successful treatment with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:914-915.

Systemic mastocytosis is a heterogeneous disorder of stem cell origin defined by abnormal hyperplasia and accumulation of mast cells (MCs) in one or more tissues.1,2 The most commonly affected tissues are the bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. Based on a number of major and minor criteria defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), the mastocytoses are subdivided into 7 variants that range from isolated cutaneous involvement to widespread systemic disease.1-4 The most frequently diagnosed subtype is indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM), a chronic disorder characterized by diffuse cutaneous macules and papules as well as bone marrow involvement in the form of multifocal dense infiltrates of MCs that frequently are phenotypically positive for c-KIT and tryptase. Serum tryptase levels are nearly invariably elevated in patients with this condition.1,2

Symptoms of ISM are determined by the intermittent release of histamine and leukotrienes from hyperproliferating MCs as well as IL-6 and eosinophil chemotactic factors. As the burden of MC secretory products increases, patients experience worsening pruritus, flushing, palpitations, vomiting, and anaphylaxis in severe instances.1,2,5 The mainstay of treatment of this condition involves symptom control through the inhibition of MC mediators.1 The majority of patients respond well to antihistamines, antileukotriene agents, and oral corticosteroids during severe episodes of MC degranulation.1,2,5

Unfortunately, some patients are unable to achieve adequate symptom control through the use of mediator-targeting treatments alone. In these cases, physicians often are faced with the following treatment dilemma: Either attempt to use therapies such as interferon alfa, which is cytoreductive to MCs, or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine to reduce the overall MC burden, or turn to newer nonimmunosuppressive second-line options. We present the case of a patient with chronic ISM with progressive cutaneous lesions and poorly controlled pruritus that was previously managed with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines who responded favorably to treatment with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy.

Case Report

A 57-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of widespread red-brown macules and papules on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. The lesions were intermittently pruritic, a symptom that was exacerbated on sun and heat exposure. A skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 9 years prior confirmed the presence of mastocytosis. The patient was originally treated with triamcinolone cream and oral antihistamines, which controlled her symptoms successfully for nearly a decade.

At the current presentation, the patient reported increasingly severe pruritus and lesional spread to the neck and face of 15 months’ duration. She denied any symptoms of flushing, diarrhea, syncopal episodes, or lightheadedness. Physical examination revealed a well-appearing middle-aged woman with multiple 3- to 8-mm, red-brown, blanchable macules and papules with areas coalescing into plaques that primarily involved the legs (Figure 1A); arms; back; and to a lesser extent the abdomen, neck, and face. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory results revealed a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic profile within reference range; however, the serum tryptase level was elevated at 65 ng/mL (reference range, <11.4 ng/mL). A positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan was negative, as well as a c-KIT mutation analysis. A review of the skin biopsy from 9 years prior demonstrated slight acanthosis with dermal proliferation of mononuclear cells (Figure 2A), some of which had abundant cytoplasm and oval-shaped nuclei. There were few eosinophils and marked dermal telangiectasias. Giemsa stain revealed increased numbers of MCs in the upper dermis (Figure 2B). A bone marrow biopsy performed 9 years later showed multifocal lesions composed of MCs with associated lymphoid aggregates without notable myelodyspoiesis (or myeloproliferative neoplasm). These features were all consistent with WHO criteria for ISM. Based on the most current clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with category IB ISM.

The patient’s symptoms had remained stable for 9 years with a regimen of triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, doxepin cream 5% daily as needed, and oral fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient continues to use topical steroids and oral antihistamines. Due to inadequate symptom control, breakthrough pruritus, and the development of new skin lesions on the head and neck, she was started on NB-UVB treatment 2 months after presentation. The patient’s symptoms and the extent of cutaneous maculopapular lesions improved after 20 light treatments (Figure 1B), with even more dramatic results after 40 cycles of therapy (Figure 1C). Overall, the lower legs have proved most recalcitrant to this treatment modality. She is currently continuing to receive NB-UVB treatment twice weekly.

Comment

Systemic mastocytosis is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by the proliferation and accumulation of atypical MCs in tissues, principally in the bone marrow and skin, though involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymphatic system also have been reported.1,2,6 The WHO classification of mastocytosis divides this condition into 7 subtypes.4 Indolent systemic mastocytosis is the most common variant.2,6 The etiology of ISM is not fully understood, but there is evidence suggesting that an activating mutation of KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase, KIT (usually D816V), present in the MCs of nearly 80% of patients with ISM may be involved.1,3-5,7 Patients occasionally present with predominantly cutaneous findings but typically seek medical attention due to the recurrent systemic symptoms of the disease (eg, pruritus, flushing, syncope, palpitations, headache, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), which are related to the release of MC mediators.1,2

The management of ISM is complex and based primarily on symptom reduction without alteration of disease course.1,2,5,7 Patients should avoid symptom triggers such as heat, humidity, emotional and physical stress, alcohol, and certain medications (ie, aspirin, opioids, radiocontrast agents).7 Patients are initially treated with histamine H1- and H2-receptor antagonists to alleviate MC mediator release symptoms.1,2,8 Although H1 blockers are most effective in mitigating cutaneous symptoms and limiting pruritus, H2 blockers are used to control gastric hypersecretion and dyspepsia.2 Proton pump inhibitors are useful in patients with peptic ulcer disease who are unresponsive to H2-receptor antagonist therapy.2,7 Cromolyn sodium and ketotifen fumarate are MC stabilizers that help prevent degranulation, which is helpful in relieving most major ISM symptoms. Leukotriene antagonists, such as zafirlukast, montelukast sodium, or zileuton, also may be employed to target the proinflammatory and pruritogenic leukotrienes, also products of the MC protein.2,7 Imatinib mesylate and masitinib mesylate, both tyrosine kinase inhibitors, have been shown to improve symptoms and reduce MC mediator levels in ISM; however, most patients harbor the resistant KIT D816V mutation, which limits the utility of this medication.Patients with sensitive KIT mutations or those who have the wild-type KIT D816 mutation may be more appropriate candidates for imatinib or masitinib therapy, which can ameliorate symptoms of flushing, pruritus, and depression.7-10 Treatment with omalizumab, a humanized murine anti-IgE monoclonal antibody, can be effective in treating recurrent, treatment-refractory anaphylaxis in ISM patients.5,7

Symptoms unresponsive to these therapies can be effectively treated with a short course of oral corticosteroids,6,7 while MC cytoreductive therapies such as interferon alfa or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (cladribine/2-CdA) are reserved for refractory cases.2,7 Alternative therapies such as NB-UVB2 or psoralen plus UVA phototherapy11 also have demonstrated success in treating ISM symptoms. In the past, NB-UVB has shown efficacy in controlling pruriginous conditions ranging from chronic urticaria12,13 to atopic dermatitis14 to psoriasis.15 This evidence has spurred studies to evaluate if NB-UVB has a role in the management of uncontrolled cases of cutaneous and ISM.2,13,16,17 To date, the evidence has been promising. The majority of patients treated with this regimen report subjective reduction in pruritus in addition to clinical cutaneous disease burden.2,11 Also, laboratory analysis demonstrates decreased levels of tryptase in patients utilizing NB-UVB phototherapy.2 Thus far, the use of NB-UVB phototherapy in the treatment of pruriginous disorders such as ISM has not been associated with any severe side effects such as increased rates of anaphylaxis, though some research has suggested that this therapy may lower the threshold for patients to develop symptomatic dermographism.12 Overall, patients treated with NB-UVB phototherapy report improved quality of life related to more effective symptom control.16

Although ISM is currently considered an incurable chronic condition,6 this case illustrates that symptomatic management is possible, even in cases of long-standing, severe disease. Patients should still be encouraged to avoid triggering factors and be vigilant in preventing potential anaphylaxis. However, NB-UVB phototherapy provides a supplemental or alternative treatment choice when other therapies have failed. We hope that the success of NB-UVB demonstrated in this case provides further evidence that this light-based therapy is a valuable treatment option in mastocytosis patients with unremitting or poorly controlled symptoms.

Systemic mastocytosis is a heterogeneous disorder of stem cell origin defined by abnormal hyperplasia and accumulation of mast cells (MCs) in one or more tissues.1,2 The most commonly affected tissues are the bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. Based on a number of major and minor criteria defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), the mastocytoses are subdivided into 7 variants that range from isolated cutaneous involvement to widespread systemic disease.1-4 The most frequently diagnosed subtype is indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM), a chronic disorder characterized by diffuse cutaneous macules and papules as well as bone marrow involvement in the form of multifocal dense infiltrates of MCs that frequently are phenotypically positive for c-KIT and tryptase. Serum tryptase levels are nearly invariably elevated in patients with this condition.1,2

Symptoms of ISM are determined by the intermittent release of histamine and leukotrienes from hyperproliferating MCs as well as IL-6 and eosinophil chemotactic factors. As the burden of MC secretory products increases, patients experience worsening pruritus, flushing, palpitations, vomiting, and anaphylaxis in severe instances.1,2,5 The mainstay of treatment of this condition involves symptom control through the inhibition of MC mediators.1 The majority of patients respond well to antihistamines, antileukotriene agents, and oral corticosteroids during severe episodes of MC degranulation.1,2,5

Unfortunately, some patients are unable to achieve adequate symptom control through the use of mediator-targeting treatments alone. In these cases, physicians often are faced with the following treatment dilemma: Either attempt to use therapies such as interferon alfa, which is cytoreductive to MCs, or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine to reduce the overall MC burden, or turn to newer nonimmunosuppressive second-line options. We present the case of a patient with chronic ISM with progressive cutaneous lesions and poorly controlled pruritus that was previously managed with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines who responded favorably to treatment with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy.

Case Report

A 57-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of widespread red-brown macules and papules on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. The lesions were intermittently pruritic, a symptom that was exacerbated on sun and heat exposure. A skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 9 years prior confirmed the presence of mastocytosis. The patient was originally treated with triamcinolone cream and oral antihistamines, which controlled her symptoms successfully for nearly a decade.

At the current presentation, the patient reported increasingly severe pruritus and lesional spread to the neck and face of 15 months’ duration. She denied any symptoms of flushing, diarrhea, syncopal episodes, or lightheadedness. Physical examination revealed a well-appearing middle-aged woman with multiple 3- to 8-mm, red-brown, blanchable macules and papules with areas coalescing into plaques that primarily involved the legs (Figure 1A); arms; back; and to a lesser extent the abdomen, neck, and face. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory results revealed a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic profile within reference range; however, the serum tryptase level was elevated at 65 ng/mL (reference range, <11.4 ng/mL). A positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan was negative, as well as a c-KIT mutation analysis. A review of the skin biopsy from 9 years prior demonstrated slight acanthosis with dermal proliferation of mononuclear cells (Figure 2A), some of which had abundant cytoplasm and oval-shaped nuclei. There were few eosinophils and marked dermal telangiectasias. Giemsa stain revealed increased numbers of MCs in the upper dermis (Figure 2B). A bone marrow biopsy performed 9 years later showed multifocal lesions composed of MCs with associated lymphoid aggregates without notable myelodyspoiesis (or myeloproliferative neoplasm). These features were all consistent with WHO criteria for ISM. Based on the most current clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with category IB ISM.

The patient’s symptoms had remained stable for 9 years with a regimen of triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, doxepin cream 5% daily as needed, and oral fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient continues to use topical steroids and oral antihistamines. Due to inadequate symptom control, breakthrough pruritus, and the development of new skin lesions on the head and neck, she was started on NB-UVB treatment 2 months after presentation. The patient’s symptoms and the extent of cutaneous maculopapular lesions improved after 20 light treatments (Figure 1B), with even more dramatic results after 40 cycles of therapy (Figure 1C). Overall, the lower legs have proved most recalcitrant to this treatment modality. She is currently continuing to receive NB-UVB treatment twice weekly.

Comment

Systemic mastocytosis is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by the proliferation and accumulation of atypical MCs in tissues, principally in the bone marrow and skin, though involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymphatic system also have been reported.1,2,6 The WHO classification of mastocytosis divides this condition into 7 subtypes.4 Indolent systemic mastocytosis is the most common variant.2,6 The etiology of ISM is not fully understood, but there is evidence suggesting that an activating mutation of KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase, KIT (usually D816V), present in the MCs of nearly 80% of patients with ISM may be involved.1,3-5,7 Patients occasionally present with predominantly cutaneous findings but typically seek medical attention due to the recurrent systemic symptoms of the disease (eg, pruritus, flushing, syncope, palpitations, headache, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), which are related to the release of MC mediators.1,2

The management of ISM is complex and based primarily on symptom reduction without alteration of disease course.1,2,5,7 Patients should avoid symptom triggers such as heat, humidity, emotional and physical stress, alcohol, and certain medications (ie, aspirin, opioids, radiocontrast agents).7 Patients are initially treated with histamine H1- and H2-receptor antagonists to alleviate MC mediator release symptoms.1,2,8 Although H1 blockers are most effective in mitigating cutaneous symptoms and limiting pruritus, H2 blockers are used to control gastric hypersecretion and dyspepsia.2 Proton pump inhibitors are useful in patients with peptic ulcer disease who are unresponsive to H2-receptor antagonist therapy.2,7 Cromolyn sodium and ketotifen fumarate are MC stabilizers that help prevent degranulation, which is helpful in relieving most major ISM symptoms. Leukotriene antagonists, such as zafirlukast, montelukast sodium, or zileuton, also may be employed to target the proinflammatory and pruritogenic leukotrienes, also products of the MC protein.2,7 Imatinib mesylate and masitinib mesylate, both tyrosine kinase inhibitors, have been shown to improve symptoms and reduce MC mediator levels in ISM; however, most patients harbor the resistant KIT D816V mutation, which limits the utility of this medication.Patients with sensitive KIT mutations or those who have the wild-type KIT D816 mutation may be more appropriate candidates for imatinib or masitinib therapy, which can ameliorate symptoms of flushing, pruritus, and depression.7-10 Treatment with omalizumab, a humanized murine anti-IgE monoclonal antibody, can be effective in treating recurrent, treatment-refractory anaphylaxis in ISM patients.5,7

Symptoms unresponsive to these therapies can be effectively treated with a short course of oral corticosteroids,6,7 while MC cytoreductive therapies such as interferon alfa or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (cladribine/2-CdA) are reserved for refractory cases.2,7 Alternative therapies such as NB-UVB2 or psoralen plus UVA phototherapy11 also have demonstrated success in treating ISM symptoms. In the past, NB-UVB has shown efficacy in controlling pruriginous conditions ranging from chronic urticaria12,13 to atopic dermatitis14 to psoriasis.15 This evidence has spurred studies to evaluate if NB-UVB has a role in the management of uncontrolled cases of cutaneous and ISM.2,13,16,17 To date, the evidence has been promising. The majority of patients treated with this regimen report subjective reduction in pruritus in addition to clinical cutaneous disease burden.2,11 Also, laboratory analysis demonstrates decreased levels of tryptase in patients utilizing NB-UVB phototherapy.2 Thus far, the use of NB-UVB phototherapy in the treatment of pruriginous disorders such as ISM has not been associated with any severe side effects such as increased rates of anaphylaxis, though some research has suggested that this therapy may lower the threshold for patients to develop symptomatic dermographism.12 Overall, patients treated with NB-UVB phototherapy report improved quality of life related to more effective symptom control.16

Although ISM is currently considered an incurable chronic condition,6 this case illustrates that symptomatic management is possible, even in cases of long-standing, severe disease. Patients should still be encouraged to avoid triggering factors and be vigilant in preventing potential anaphylaxis. However, NB-UVB phototherapy provides a supplemental or alternative treatment choice when other therapies have failed. We hope that the success of NB-UVB demonstrated in this case provides further evidence that this light-based therapy is a valuable treatment option in mastocytosis patients with unremitting or poorly controlled symptoms.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier; 2012.

- Brazzelli V, Grasso V, Manna G, et al. Indolent systemic mastocytosis treated with narrow-band UVB phototherapy: study of five cases [published online May 13, 2011]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:465-469.

- Pardanani A, Lim KH, Lasho TL, et al. WHO subvariants of indolent mastocytosis: clinical details and prognostic evaluation in 159 consecutive adults. Blood. 2010;115:150-151.

- Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes [published online April 8, 2009]. Blood. 2009;114:937-951.

- Wolff K, Komar M, Petzelbauer P. Clinical and histopathological aspects of cutaneous mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:519-528.

- Marone G, Spadaro G, Granata F, et al. Treatment of mastocytosis: pharmacologic basis and current concepts. Leuk Res. 2001;25:583-594.

- Pardanani A. How I treat patients with indolent and smoldering mastocytosis (rare conditions but difficult to manage)[published online February 20, 2013]. Blood. 2013;121:3085-3094.

- Hartmann K, Henz BM. Mastocytosis: recent advances in defining the disease. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:682-695.

- Vega-Ruiz A, Cortes JE, Sever M, et al. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate as therapy for patients with systemic mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1481-1484.

- Lortholary O, Chandesris MO, Bulai Livideanu C, et al. Masitinib for treatment of severely symptomatic indolent systemic mastocytosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389:612-620.

- Godt O, Proksch E, Streit V, et al. Short-and long-term effectiveness of oral and bath PUVA therapy in urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. Dermatology. 1997;1:35-39.

- Berroeta L, Clark C, Ibbotson SH, et al. Narrow-band (TL-01) ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:91-99.

- Engin B, Ozdemir M, Balevi A, et al. Treatment of chronic urticaria with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;3:247-251.

- Meduri NB, Vandergriff T, Rasmussen H, et al. Phototherapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systemic review. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:106-112.

- Nguyen T, Gattu S, Pugashetti R, et al. Practice of phototherapy in the treatment of moderate-to severe psoriasis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2009;38:59-78.

- Brazzelli V, Grassi S, Merante S, et al. Narrow-band UVB phototherapy and psoralen-ultraviolet A photochemotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous mastocytosis: a study in 20 patients. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2016;32:238-246.

- Prignano F, Troiano M, Lotti T. Cutaneous mastocytosis: successful treatment with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:914-915.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier; 2012.

- Brazzelli V, Grasso V, Manna G, et al. Indolent systemic mastocytosis treated with narrow-band UVB phototherapy: study of five cases [published online May 13, 2011]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:465-469.

- Pardanani A, Lim KH, Lasho TL, et al. WHO subvariants of indolent mastocytosis: clinical details and prognostic evaluation in 159 consecutive adults. Blood. 2010;115:150-151.

- Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes [published online April 8, 2009]. Blood. 2009;114:937-951.

- Wolff K, Komar M, Petzelbauer P. Clinical and histopathological aspects of cutaneous mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:519-528.

- Marone G, Spadaro G, Granata F, et al. Treatment of mastocytosis: pharmacologic basis and current concepts. Leuk Res. 2001;25:583-594.

- Pardanani A. How I treat patients with indolent and smoldering mastocytosis (rare conditions but difficult to manage)[published online February 20, 2013]. Blood. 2013;121:3085-3094.

- Hartmann K, Henz BM. Mastocytosis: recent advances in defining the disease. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:682-695.

- Vega-Ruiz A, Cortes JE, Sever M, et al. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate as therapy for patients with systemic mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1481-1484.

- Lortholary O, Chandesris MO, Bulai Livideanu C, et al. Masitinib for treatment of severely symptomatic indolent systemic mastocytosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389:612-620.

- Godt O, Proksch E, Streit V, et al. Short-and long-term effectiveness of oral and bath PUVA therapy in urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. Dermatology. 1997;1:35-39.

- Berroeta L, Clark C, Ibbotson SH, et al. Narrow-band (TL-01) ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:91-99.

- Engin B, Ozdemir M, Balevi A, et al. Treatment of chronic urticaria with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;3:247-251.

- Meduri NB, Vandergriff T, Rasmussen H, et al. Phototherapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systemic review. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:106-112.

- Nguyen T, Gattu S, Pugashetti R, et al. Practice of phototherapy in the treatment of moderate-to severe psoriasis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2009;38:59-78.