User login

Mohs Micrographic Surgery for Digital Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

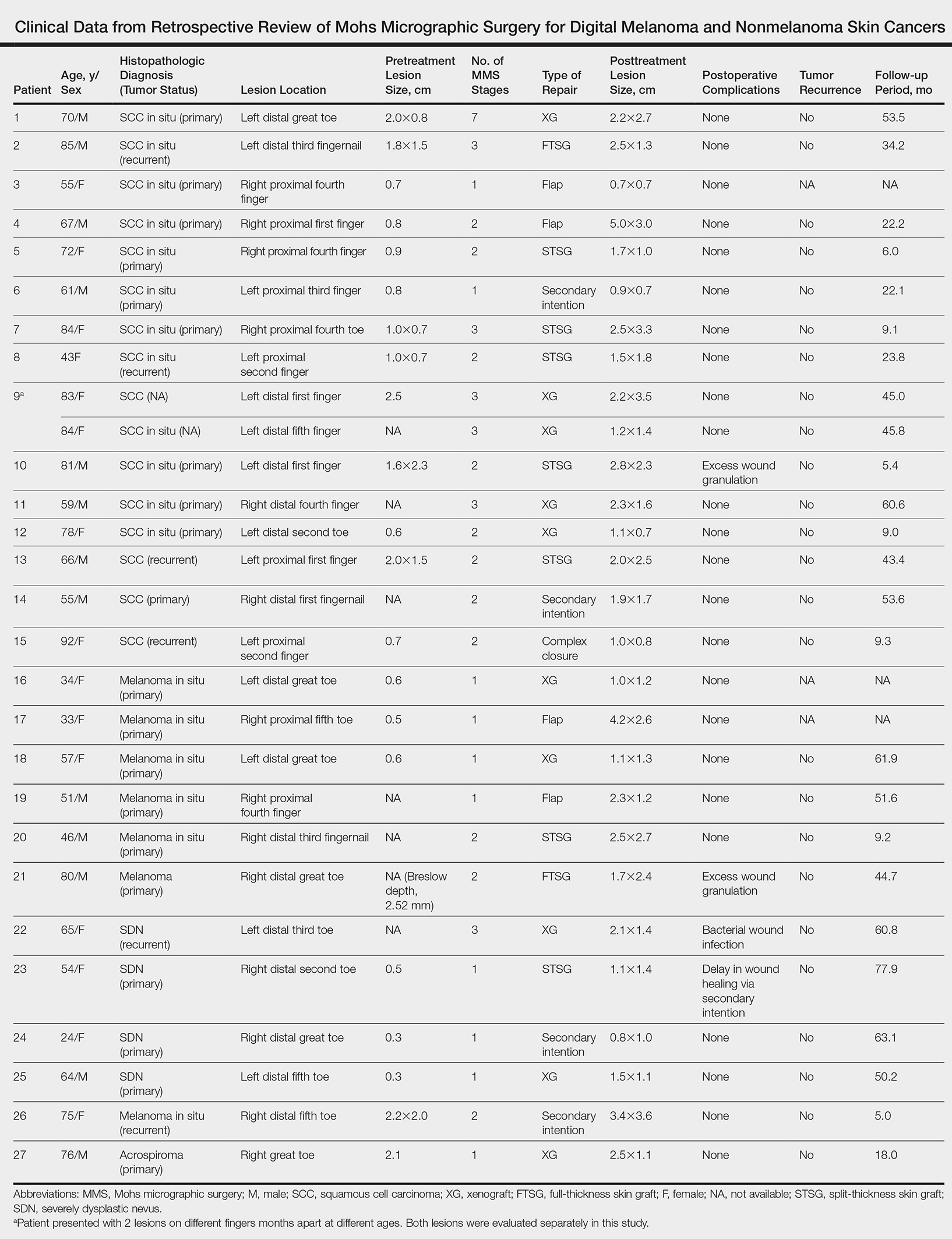

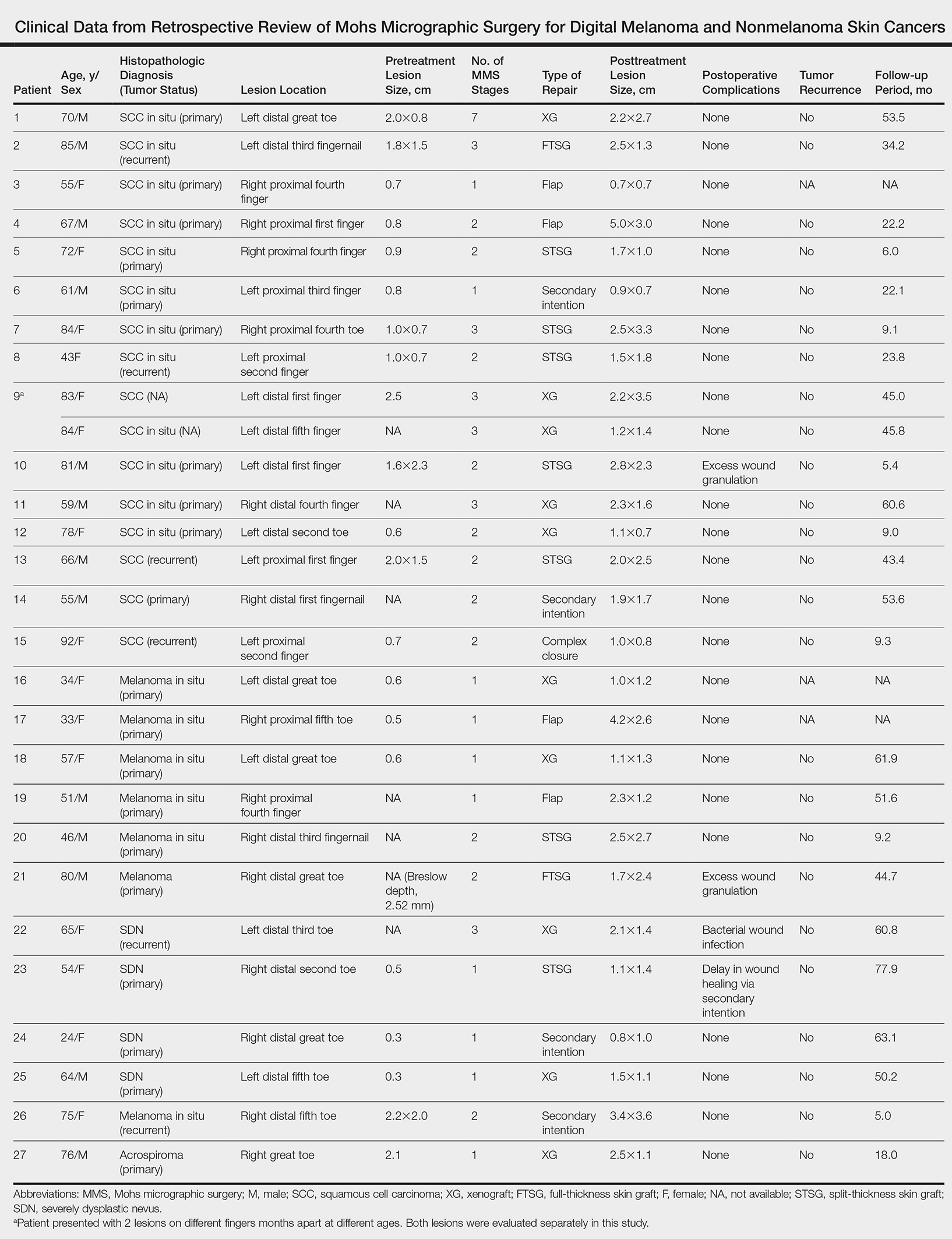

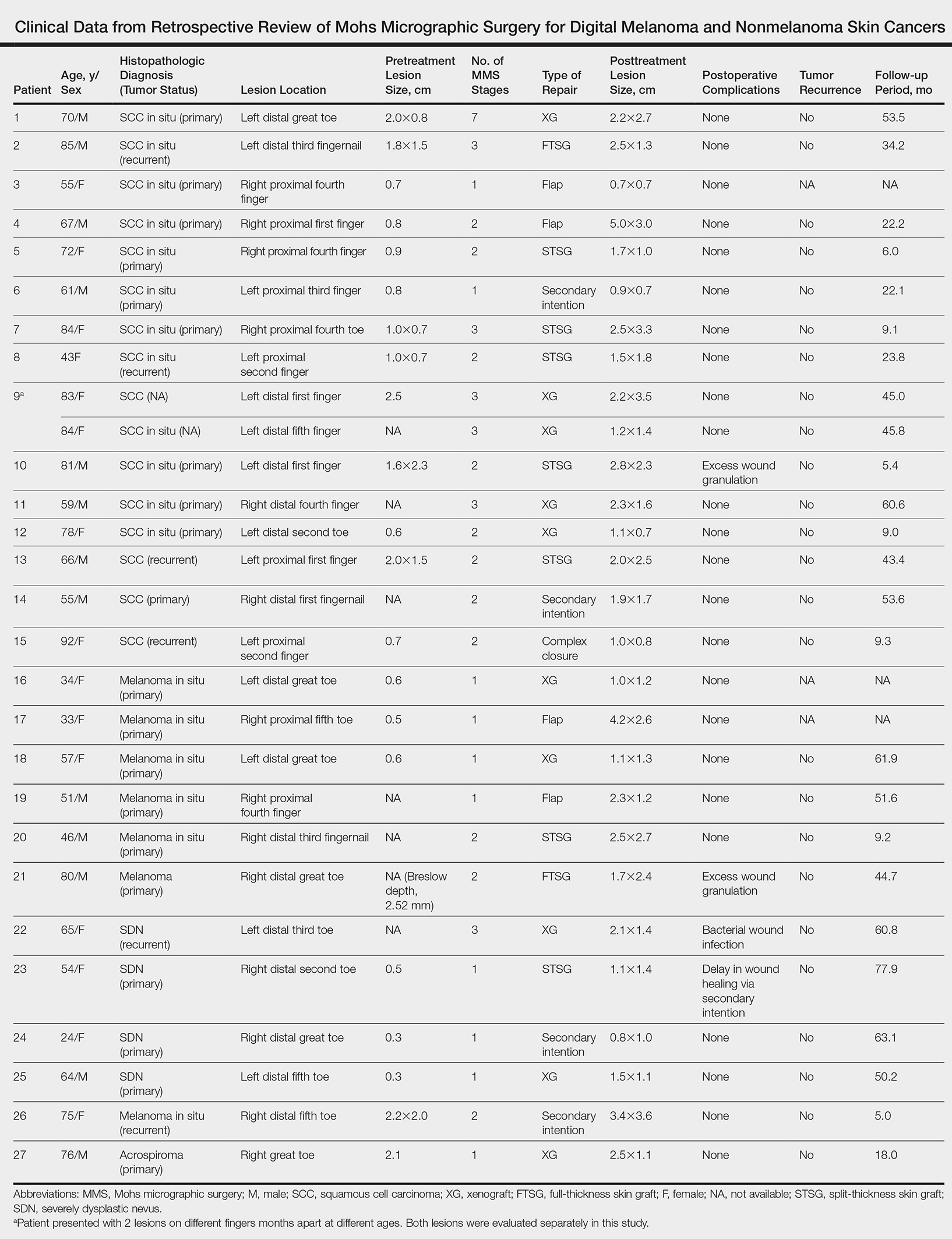

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

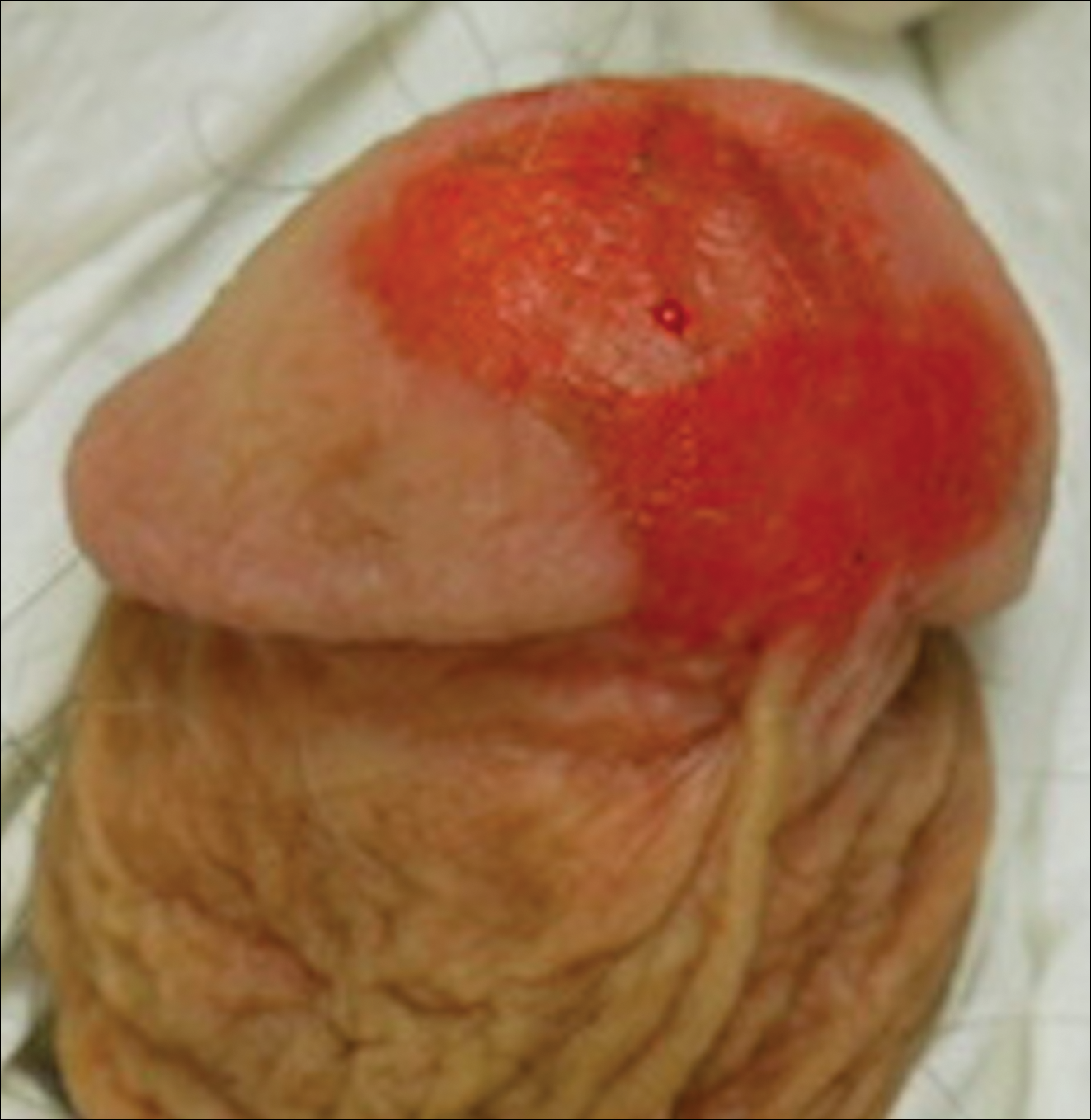

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

Practice Points

- Melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers of the digits traditionally have been treated with wide local surgical excision and even amputation.

- Conservative tissue sparing techniques such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be used to treat digital skin cancers with high cure rates and improved functional and cosmetic results.

Penile Squamous Cell Carcinoma With Urethral Extension Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with considerable urethral extension is uncommon and difficult to manage. It often is resistant to less invasive and nonsurgical treatments and frequently results in partial or total penectomy, which can lead to cosmetic disfigurement, functional issues, and psychological distress. We report a case of penile SCC in situ with considerable urethral extension with a focus of cells suspicious for moderately well-differentiated and invasive SCC that was treated with

Mohs micrographic surgery with distal urethrectomy and reconstruction is a valuable treatment technique for cases of SCC involving the glans penis and distal urethra. It offers equivalent or better overall cure rates compared to more radical interventions. Additionally, preservation of the penis with MMS spares patients from considerable physical and psychosocial morbidity. Our case, along with growing body of literature,1-4 calls on dermatologists and urologists to consider MMS as a treatment for penile SCC with or without urethral involvement.

Case Report

A 61-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a pruritic lesion on the penis that had been present for 6 years. Shave biopsy demonstrated SCC in situ with a focus of cells suspicious for moderately well-differentiated and invasive SCC. Physical examination revealed an ill-defined, 2.2×1.9-cm, pink, eroded plaque involving the tip of the penis and surrounding the external urinary meatus (Figure 1). There was no palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy.

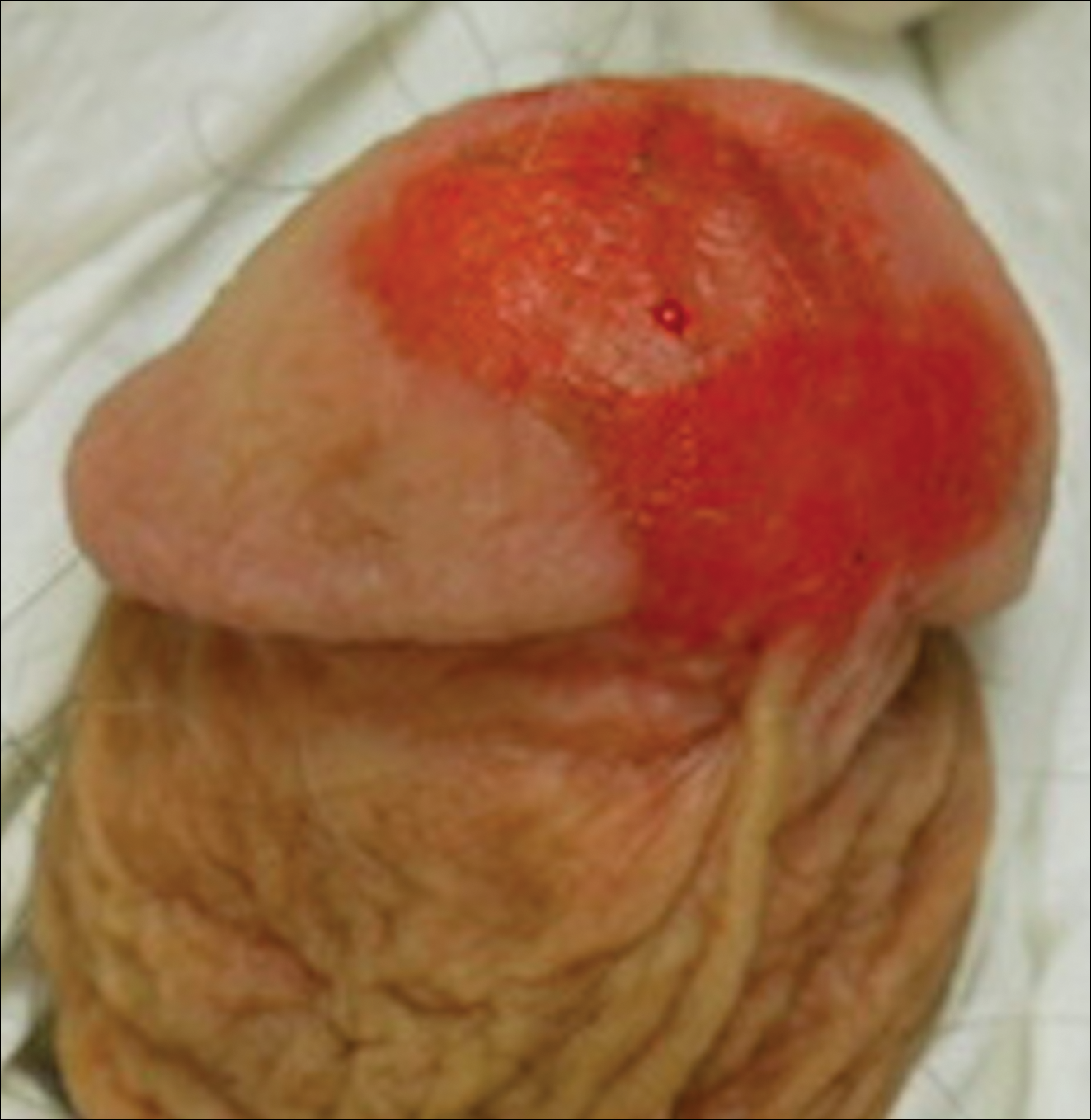

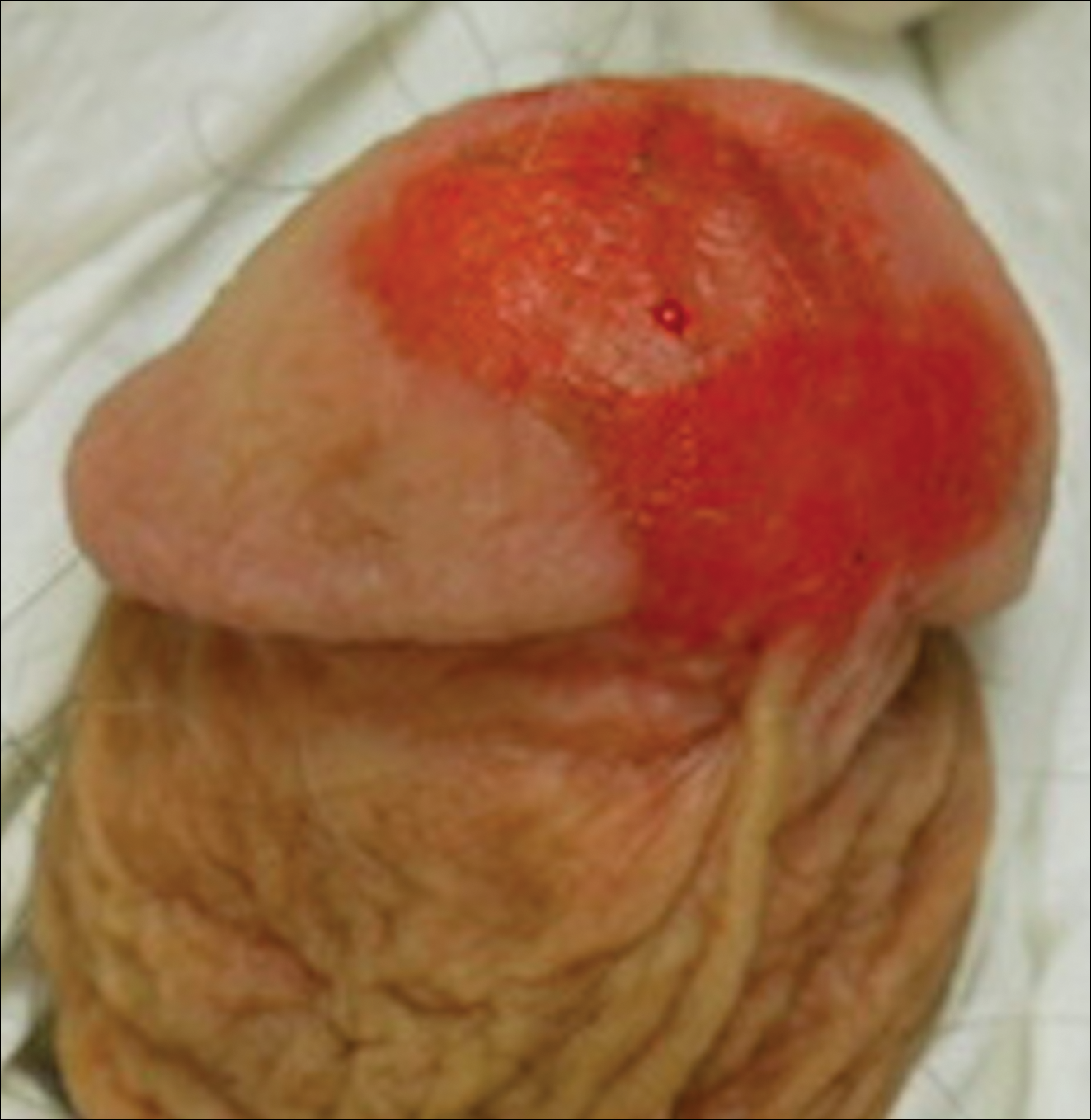

Distal penectomy and lymph node biopsy was recommended following evaluation by the urologic oncology department, but the patient declined these interventions and presented to our dermatology department (A.H.) for a second opinion. The tumor, including the invasive perineural portion, was removed using MMS several weeks after initially presenting to urologic oncology. Ventral meatotomy allowed access to the SCC in situ portion extending proximally up the pendulous urethra (Figure 2). Clear margins were obtained after the eighth stage of MMS, which required removal of 4 to 5 cm of the distal urethra (Figure 3). Reconstruction of the wound required urethral advancement, urethrostomy, and meatoplasty. A positive outcome was achieved with preservation of the length and shape of the penis as well as the cosmetic appearance of the glans penis (Figure 4). The patient was satisfied with the outcome. At 49 months’ follow-up, no evidence of local recurrence or disease progression was noted, and the distal urethrostomy remained intact and functional.

Comment

Penile SCC is a rare malignancy that represents between 0.4% and 0.6% of all malignant tumors in the United States and occurs most commonly in men aged 50 to 70 years.4 The incidence is higher in developing countries, approaching 10% of malignancies in men. It occurs most commonly on the glans penis, prepuce, and coronal sulcus, and has multiple possible appearances, including erythematous and indurated, warty and exophytic, or flat and ulcerated lesions.5 Some reports indicate that more than 40% of penile SCCs are attributable to human papilloma virus,6 while lack of circumcision, chronic inflammation, poor hygiene, balanitis xerotica obliterans, penile trauma, human immunodeficiency virus, UVA treatment of penile psoriasis, and tobacco use are known risk factors.5

Invasive penile SCC generally is treated with penectomy (partial or total), radiation therapy, or MMS; SCC in situ can be treated with topical chemotherapy, laser therapy, and wide local excision (2-cm margins) including circumcision, complete glansectomy, or MMS.5 Squamous cell carcinoma in situ with urethral involvement treated with nonsurgical therapies is associated with higher recurrence rates, ultimately necessitating more aggressive treatments, most commonly partial penectomy.7 The high local recurrence rate of SCC in situ with urethral involvement treated with nonsurgical therapies reflects the fact that determining the presence of urethral extension is difficult and, if present, is inherently inaccessible to these local therapies because the urethra is not an outward-facing tissue surface; MMS represents one possible solution to these issues.

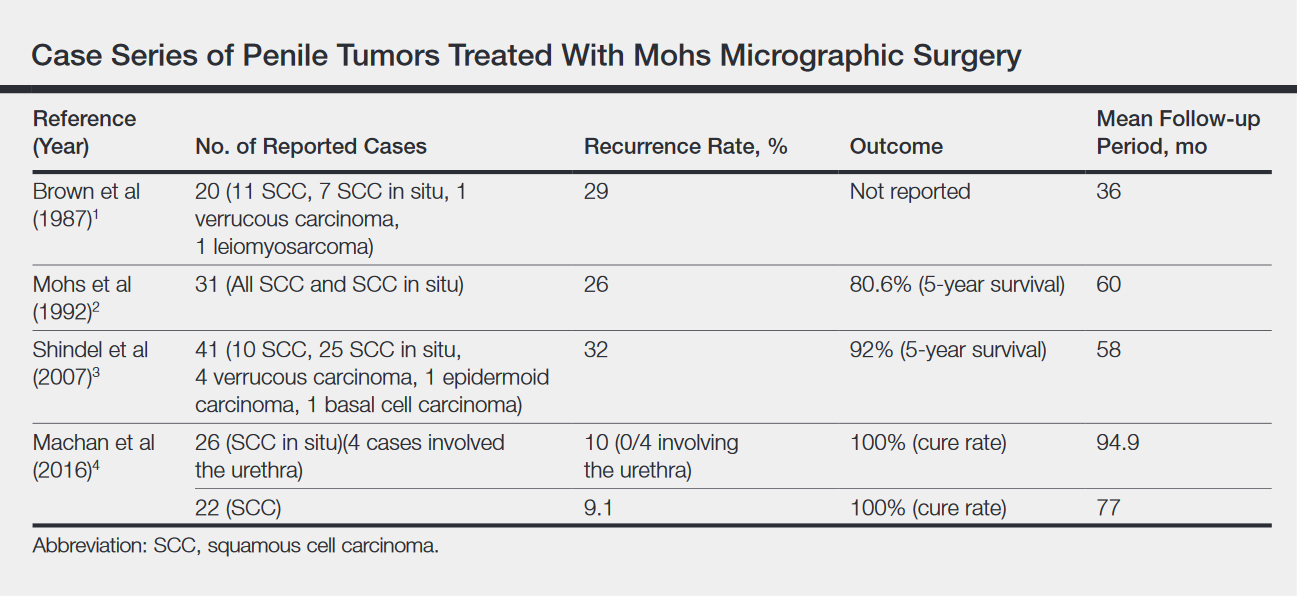

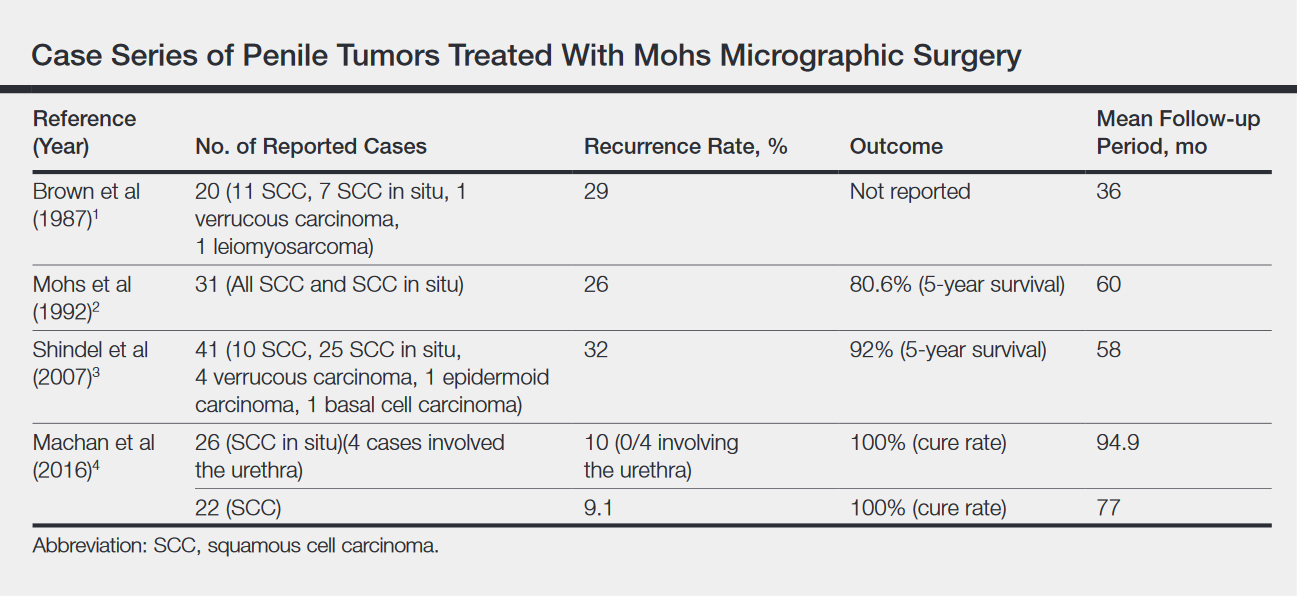

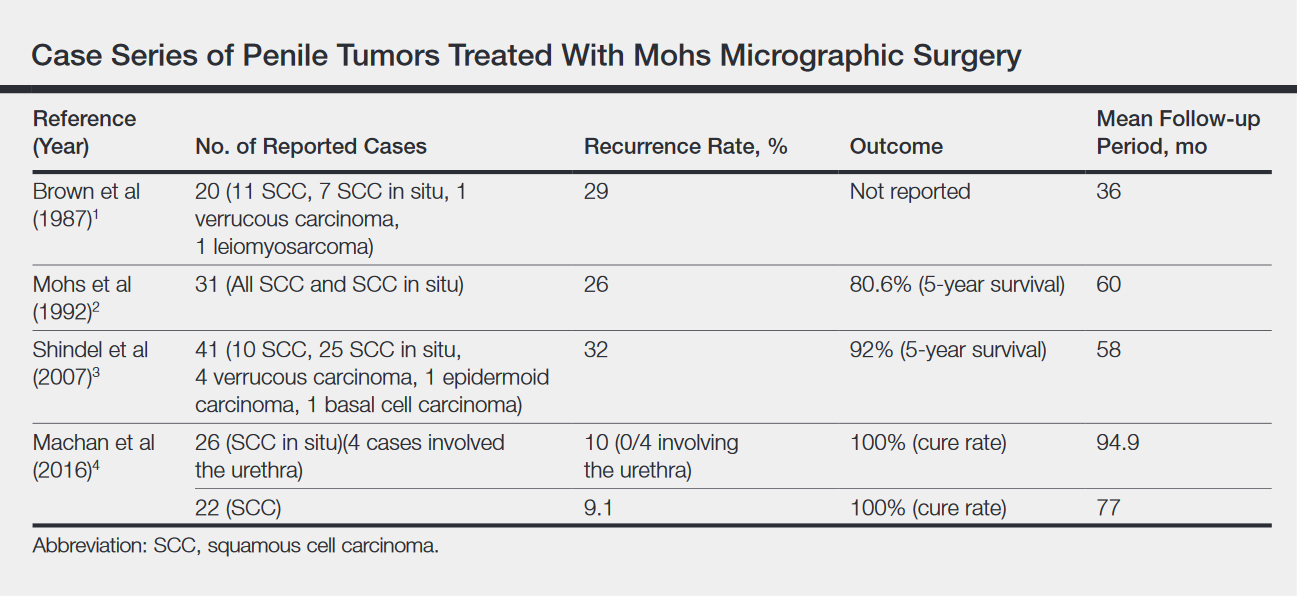

Across all treatment modalities, the most prognostic factor of cancer-specific survival in patients with penile SCC is pelvic lymph node involvement. Some reports cite 5-year survival rates as low as 0% in the setting of pelvic lymph node involvement,5 whereas others had cited rates of 29% to 40%4; 5-year survival rates of higher than 85% have been reported in node-negative patients.4 Recurrence rates vary widely by treatment modality, ranging from less than 10% with partial penectomy and long-term follow-up8 and up to 50% within 2 years with penile-preserving approaches (eg, topical chemotherapy, laser therapy, radiotherapy).5 Multiple case series of penile cancer (the most common of which was SCC/SCC in situ) treated with MMS report comparable and at times superior survival and recurrence data (Table).1-4 Slightly higher recurrences of penile SCC treated with MMS compared to penectomy have been reported, along with considerably higher recurrence rates compared to nonpenile cutaneous SCC treated with MMS (reported to be less than 3%).4 The elastic and expansile nature of penile tissue may lead to distortion from swelling/local anesthesia when taking individual Mohs layers. Additionally, as a large percentage of penile SCCs are attributable to human papillomavirus, difficulty in detecting human papilloma virus–infected cells (which may have oncogenic potential) with the naked eye or histologically with typical staining techniques may help explain the higher recurrence rate of penile SCC treated with MMS compared to penectomy. Despite the higher recurrence rates, survival is comparable or higher in cases treated with MMS (Table).

Partial penectomy also has a negative impact on health-related quality of life. Kieffer et al9 compared the impact of penile-sparing surgery (PSS)(including MMS) versus partial or total penectomy on sexual function and health-related quality of life in 90 patients with penile cancer. Although the association between the extent of surgery (partial penectomy/total penectomy/PSS) surgery type and extent and most outcome measures was not statistically significant, partial penectomy was associated with significantly more problems with orgasm (P=.031), concerns about appearance (P=.008), interference in daily life (P=.032), and urinary function (P<.0001) when compared to patients treated with PSS.9 Although this study included only laser/local excision with or without circumcision or glans penis amputation with or without reconstruction as PSSs and did not explicitly include MMS, MMS is clearly a tissue-sparing technique and the study results are generaliz

Conclusion

Penile SCC with considerable urethral extension is uncommon, difficult to manage, and often is resistant to less invasive and nonsurgical treatments. As a result, partial or total penectomy is sometimes necessary. Such cases benefit from MMS with distal urethrectomy and reconstruction because MMS provides equivalent or better overall cure rates compared to more radical interventions.1-4 Importantly, preservation of the penis with MMS can spare patients considerable physical and psychosocial morbidity. Partial penectomy is associated with more health-related quality-of-life problems with orgasm, concerns about appearance, interference in daily life, and urinary function compared to PSSs such as MMS.9 This case, and a growing body of literature, are a call to dermatologists and urologists to consider MMS as a treatment for penile SCC, even with involvement of the urethra.

- Brown MD, Zachary CB, Grekin RC, et al. Penile tumors: their management by Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1163-1167.

- Mohs FE, Snow SN, Larson PO. Mohs micrographic surgery for penile tumors. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:291-304.

- Shindel AW, Mann MW, Lev RY, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for penile cancer: management and long-term followup. J Urol. 2007;178:1980-1985.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

- Spiess PE, Horenblas S, Pagliaro LC, et al. Current concepts in penile cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:617-624.

- Hernandez BY, Barnholtz-Sloan J, German RR, et al. Burden of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in the United States, 1998-2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 suppl):2883-2891.

- Nash PA, Bihrle R, Gleason PE, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and distal urethrectomy with immediate urethral reconstruction for glanular carcinoma in situ with significant urethral extension. Urology. 1996;47:108-110.

- Djordjevic ML, Palminteri E, Martins F. Male genital reconstruction for the penile cancer survivor. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:427-433.

- Kieffer JM, Djajadiningrat RS, van Muilekom EA, et al. Quality of life for patients treated for penile cancer. J Urol. 2014;192:1105-1110.

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with considerable urethral extension is uncommon and difficult to manage. It often is resistant to less invasive and nonsurgical treatments and frequently results in partial or total penectomy, which can lead to cosmetic disfigurement, functional issues, and psychological distress. We report a case of penile SCC in situ with considerable urethral extension with a focus of cells suspicious for moderately well-differentiated and invasive SCC that was treated with

Mohs micrographic surgery with distal urethrectomy and reconstruction is a valuable treatment technique for cases of SCC involving the glans penis and distal urethra. It offers equivalent or better overall cure rates compared to more radical interventions. Additionally, preservation of the penis with MMS spares patients from considerable physical and psychosocial morbidity. Our case, along with growing body of literature,1-4 calls on dermatologists and urologists to consider MMS as a treatment for penile SCC with or without urethral involvement.

Case Report

A 61-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a pruritic lesion on the penis that had been present for 6 years. Shave biopsy demonstrated SCC in situ with a focus of cells suspicious for moderately well-differentiated and invasive SCC. Physical examination revealed an ill-defined, 2.2×1.9-cm, pink, eroded plaque involving the tip of the penis and surrounding the external urinary meatus (Figure 1). There was no palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Distal penectomy and lymph node biopsy was recommended following evaluation by the urologic oncology department, but the patient declined these interventions and presented to our dermatology department (A.H.) for a second opinion. The tumor, including the invasive perineural portion, was removed using MMS several weeks after initially presenting to urologic oncology. Ventral meatotomy allowed access to the SCC in situ portion extending proximally up the pendulous urethra (Figure 2). Clear margins were obtained after the eighth stage of MMS, which required removal of 4 to 5 cm of the distal urethra (Figure 3). Reconstruction of the wound required urethral advancement, urethrostomy, and meatoplasty. A positive outcome was achieved with preservation of the length and shape of the penis as well as the cosmetic appearance of the glans penis (Figure 4). The patient was satisfied with the outcome. At 49 months’ follow-up, no evidence of local recurrence or disease progression was noted, and the distal urethrostomy remained intact and functional.

Comment

Penile SCC is a rare malignancy that represents between 0.4% and 0.6% of all malignant tumors in the United States and occurs most commonly in men aged 50 to 70 years.4 The incidence is higher in developing countries, approaching 10% of malignancies in men. It occurs most commonly on the glans penis, prepuce, and coronal sulcus, and has multiple possible appearances, including erythematous and indurated, warty and exophytic, or flat and ulcerated lesions.5 Some reports indicate that more than 40% of penile SCCs are attributable to human papilloma virus,6 while lack of circumcision, chronic inflammation, poor hygiene, balanitis xerotica obliterans, penile trauma, human immunodeficiency virus, UVA treatment of penile psoriasis, and tobacco use are known risk factors.5

Invasive penile SCC generally is treated with penectomy (partial or total), radiation therapy, or MMS; SCC in situ can be treated with topical chemotherapy, laser therapy, and wide local excision (2-cm margins) including circumcision, complete glansectomy, or MMS.5 Squamous cell carcinoma in situ with urethral involvement treated with nonsurgical therapies is associated with higher recurrence rates, ultimately necessitating more aggressive treatments, most commonly partial penectomy.7 The high local recurrence rate of SCC in situ with urethral involvement treated with nonsurgical therapies reflects the fact that determining the presence of urethral extension is difficult and, if present, is inherently inaccessible to these local therapies because the urethra is not an outward-facing tissue surface; MMS represents one possible solution to these issues.

Across all treatment modalities, the most prognostic factor of cancer-specific survival in patients with penile SCC is pelvic lymph node involvement. Some reports cite 5-year survival rates as low as 0% in the setting of pelvic lymph node involvement,5 whereas others had cited rates of 29% to 40%4; 5-year survival rates of higher than 85% have been reported in node-negative patients.4 Recurrence rates vary widely by treatment modality, ranging from less than 10% with partial penectomy and long-term follow-up8 and up to 50% within 2 years with penile-preserving approaches (eg, topical chemotherapy, laser therapy, radiotherapy).5 Multiple case series of penile cancer (the most common of which was SCC/SCC in situ) treated with MMS report comparable and at times superior survival and recurrence data (Table).1-4 Slightly higher recurrences of penile SCC treated with MMS compared to penectomy have been reported, along with considerably higher recurrence rates compared to nonpenile cutaneous SCC treated with MMS (reported to be less than 3%).4 The elastic and expansile nature of penile tissue may lead to distortion from swelling/local anesthesia when taking individual Mohs layers. Additionally, as a large percentage of penile SCCs are attributable to human papillomavirus, difficulty in detecting human papilloma virus–infected cells (which may have oncogenic potential) with the naked eye or histologically with typical staining techniques may help explain the higher recurrence rate of penile SCC treated with MMS compared to penectomy. Despite the higher recurrence rates, survival is comparable or higher in cases treated with MMS (Table).

Partial penectomy also has a negative impact on health-related quality of life. Kieffer et al9 compared the impact of penile-sparing surgery (PSS)(including MMS) versus partial or total penectomy on sexual function and health-related quality of life in 90 patients with penile cancer. Although the association between the extent of surgery (partial penectomy/total penectomy/PSS) surgery type and extent and most outcome measures was not statistically significant, partial penectomy was associated with significantly more problems with orgasm (P=.031), concerns about appearance (P=.008), interference in daily life (P=.032), and urinary function (P<.0001) when compared to patients treated with PSS.9 Although this study included only laser/local excision with or without circumcision or glans penis amputation with or without reconstruction as PSSs and did not explicitly include MMS, MMS is clearly a tissue-sparing technique and the study results are generaliz

Conclusion

Penile SCC with considerable urethral extension is uncommon, difficult to manage, and often is resistant to less invasive and nonsurgical treatments. As a result, partial or total penectomy is sometimes necessary. Such cases benefit from MMS with distal urethrectomy and reconstruction because MMS provides equivalent or better overall cure rates compared to more radical interventions.1-4 Importantly, preservation of the penis with MMS can spare patients considerable physical and psychosocial morbidity. Partial penectomy is associated with more health-related quality-of-life problems with orgasm, concerns about appearance, interference in daily life, and urinary function compared to PSSs such as MMS.9 This case, and a growing body of literature, are a call to dermatologists and urologists to consider MMS as a treatment for penile SCC, even with involvement of the urethra.

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with considerable urethral extension is uncommon and difficult to manage. It often is resistant to less invasive and nonsurgical treatments and frequently results in partial or total penectomy, which can lead to cosmetic disfigurement, functional issues, and psychological distress. We report a case of penile SCC in situ with considerable urethral extension with a focus of cells suspicious for moderately well-differentiated and invasive SCC that was treated with

Mohs micrographic surgery with distal urethrectomy and reconstruction is a valuable treatment technique for cases of SCC involving the glans penis and distal urethra. It offers equivalent or better overall cure rates compared to more radical interventions. Additionally, preservation of the penis with MMS spares patients from considerable physical and psychosocial morbidity. Our case, along with growing body of literature,1-4 calls on dermatologists and urologists to consider MMS as a treatment for penile SCC with or without urethral involvement.

Case Report

A 61-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a pruritic lesion on the penis that had been present for 6 years. Shave biopsy demonstrated SCC in situ with a focus of cells suspicious for moderately well-differentiated and invasive SCC. Physical examination revealed an ill-defined, 2.2×1.9-cm, pink, eroded plaque involving the tip of the penis and surrounding the external urinary meatus (Figure 1). There was no palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Distal penectomy and lymph node biopsy was recommended following evaluation by the urologic oncology department, but the patient declined these interventions and presented to our dermatology department (A.H.) for a second opinion. The tumor, including the invasive perineural portion, was removed using MMS several weeks after initially presenting to urologic oncology. Ventral meatotomy allowed access to the SCC in situ portion extending proximally up the pendulous urethra (Figure 2). Clear margins were obtained after the eighth stage of MMS, which required removal of 4 to 5 cm of the distal urethra (Figure 3). Reconstruction of the wound required urethral advancement, urethrostomy, and meatoplasty. A positive outcome was achieved with preservation of the length and shape of the penis as well as the cosmetic appearance of the glans penis (Figure 4). The patient was satisfied with the outcome. At 49 months’ follow-up, no evidence of local recurrence or disease progression was noted, and the distal urethrostomy remained intact and functional.

Comment

Penile SCC is a rare malignancy that represents between 0.4% and 0.6% of all malignant tumors in the United States and occurs most commonly in men aged 50 to 70 years.4 The incidence is higher in developing countries, approaching 10% of malignancies in men. It occurs most commonly on the glans penis, prepuce, and coronal sulcus, and has multiple possible appearances, including erythematous and indurated, warty and exophytic, or flat and ulcerated lesions.5 Some reports indicate that more than 40% of penile SCCs are attributable to human papilloma virus,6 while lack of circumcision, chronic inflammation, poor hygiene, balanitis xerotica obliterans, penile trauma, human immunodeficiency virus, UVA treatment of penile psoriasis, and tobacco use are known risk factors.5

Invasive penile SCC generally is treated with penectomy (partial or total), radiation therapy, or MMS; SCC in situ can be treated with topical chemotherapy, laser therapy, and wide local excision (2-cm margins) including circumcision, complete glansectomy, or MMS.5 Squamous cell carcinoma in situ with urethral involvement treated with nonsurgical therapies is associated with higher recurrence rates, ultimately necessitating more aggressive treatments, most commonly partial penectomy.7 The high local recurrence rate of SCC in situ with urethral involvement treated with nonsurgical therapies reflects the fact that determining the presence of urethral extension is difficult and, if present, is inherently inaccessible to these local therapies because the urethra is not an outward-facing tissue surface; MMS represents one possible solution to these issues.

Across all treatment modalities, the most prognostic factor of cancer-specific survival in patients with penile SCC is pelvic lymph node involvement. Some reports cite 5-year survival rates as low as 0% in the setting of pelvic lymph node involvement,5 whereas others had cited rates of 29% to 40%4; 5-year survival rates of higher than 85% have been reported in node-negative patients.4 Recurrence rates vary widely by treatment modality, ranging from less than 10% with partial penectomy and long-term follow-up8 and up to 50% within 2 years with penile-preserving approaches (eg, topical chemotherapy, laser therapy, radiotherapy).5 Multiple case series of penile cancer (the most common of which was SCC/SCC in situ) treated with MMS report comparable and at times superior survival and recurrence data (Table).1-4 Slightly higher recurrences of penile SCC treated with MMS compared to penectomy have been reported, along with considerably higher recurrence rates compared to nonpenile cutaneous SCC treated with MMS (reported to be less than 3%).4 The elastic and expansile nature of penile tissue may lead to distortion from swelling/local anesthesia when taking individual Mohs layers. Additionally, as a large percentage of penile SCCs are attributable to human papillomavirus, difficulty in detecting human papilloma virus–infected cells (which may have oncogenic potential) with the naked eye or histologically with typical staining techniques may help explain the higher recurrence rate of penile SCC treated with MMS compared to penectomy. Despite the higher recurrence rates, survival is comparable or higher in cases treated with MMS (Table).

Partial penectomy also has a negative impact on health-related quality of life. Kieffer et al9 compared the impact of penile-sparing surgery (PSS)(including MMS) versus partial or total penectomy on sexual function and health-related quality of life in 90 patients with penile cancer. Although the association between the extent of surgery (partial penectomy/total penectomy/PSS) surgery type and extent and most outcome measures was not statistically significant, partial penectomy was associated with significantly more problems with orgasm (P=.031), concerns about appearance (P=.008), interference in daily life (P=.032), and urinary function (P<.0001) when compared to patients treated with PSS.9 Although this study included only laser/local excision with or without circumcision or glans penis amputation with or without reconstruction as PSSs and did not explicitly include MMS, MMS is clearly a tissue-sparing technique and the study results are generaliz

Conclusion

Penile SCC with considerable urethral extension is uncommon, difficult to manage, and often is resistant to less invasive and nonsurgical treatments. As a result, partial or total penectomy is sometimes necessary. Such cases benefit from MMS with distal urethrectomy and reconstruction because MMS provides equivalent or better overall cure rates compared to more radical interventions.1-4 Importantly, preservation of the penis with MMS can spare patients considerable physical and psychosocial morbidity. Partial penectomy is associated with more health-related quality-of-life problems with orgasm, concerns about appearance, interference in daily life, and urinary function compared to PSSs such as MMS.9 This case, and a growing body of literature, are a call to dermatologists and urologists to consider MMS as a treatment for penile SCC, even with involvement of the urethra.

- Brown MD, Zachary CB, Grekin RC, et al. Penile tumors: their management by Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1163-1167.

- Mohs FE, Snow SN, Larson PO. Mohs micrographic surgery for penile tumors. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:291-304.

- Shindel AW, Mann MW, Lev RY, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for penile cancer: management and long-term followup. J Urol. 2007;178:1980-1985.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

- Spiess PE, Horenblas S, Pagliaro LC, et al. Current concepts in penile cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:617-624.

- Hernandez BY, Barnholtz-Sloan J, German RR, et al. Burden of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in the United States, 1998-2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 suppl):2883-2891.

- Nash PA, Bihrle R, Gleason PE, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and distal urethrectomy with immediate urethral reconstruction for glanular carcinoma in situ with significant urethral extension. Urology. 1996;47:108-110.

- Djordjevic ML, Palminteri E, Martins F. Male genital reconstruction for the penile cancer survivor. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:427-433.

- Kieffer JM, Djajadiningrat RS, van Muilekom EA, et al. Quality of life for patients treated for penile cancer. J Urol. 2014;192:1105-1110.

- Brown MD, Zachary CB, Grekin RC, et al. Penile tumors: their management by Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1163-1167.

- Mohs FE, Snow SN, Larson PO. Mohs micrographic surgery for penile tumors. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:291-304.

- Shindel AW, Mann MW, Lev RY, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for penile cancer: management and long-term followup. J Urol. 2007;178:1980-1985.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

- Spiess PE, Horenblas S, Pagliaro LC, et al. Current concepts in penile cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:617-624.

- Hernandez BY, Barnholtz-Sloan J, German RR, et al. Burden of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in the United States, 1998-2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 suppl):2883-2891.

- Nash PA, Bihrle R, Gleason PE, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and distal urethrectomy with immediate urethral reconstruction for glanular carcinoma in situ with significant urethral extension. Urology. 1996;47:108-110.

- Djordjevic ML, Palminteri E, Martins F. Male genital reconstruction for the penile cancer survivor. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:427-433.

- Kieffer JM, Djajadiningrat RS, van Muilekom EA, et al. Quality of life for patients treated for penile cancer. J Urol. 2014;192:1105-1110.

Resident Pearl

- Penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) often is treated with partial or total penectomy, especially when there is urethral extension. Mohs micrographic surgery for penile SCC results in equivalent or better overall cure rates and decreases morbidity.