User login

Dupilumab-Associated Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, was first described in 1964. 1 Since then, several subtypes of SS have been recognized, including classic or idiopathic, which typically follows an acute viral illness; cancer related, typically in the form of a paraneoplastic syndrome; and drug induced. 2 Drug-induced SS is defined by the following: (1) an abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules; (2) histopathologic evidence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; (3) pyrexia above 38 ° C; (4) temporal relationship between drug and clinical presentation or temporally related recurrence after rechallenge; and (5) temporally related resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids. 3 All 5 criteria must be met to make a diagnosis of drug-induced SS. Since these criteria were established by Walker and Cohen, 3 various drugs have been identified as causative agents, including antibiotics, antiepileptics, antiretrovirals, antineoplastic agents, antipsychotics, oral contraceptives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids. 4 W e present a rare case of SS caused by dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody therapy, used in the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma and atopic dermatitis.

Case Report

A 53-year-old woman presented with painful skin lesions, arthralgia, fever, and leukocytosis following initiation of dupilumab. She had a history of adult-onset, severe, persistent eosinophilic asthma, as well as chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, plaque psoriasis, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. She started mepolizumab 3 years prior to the current presentation for persistently uncontrolled asthma with a baseline peripheral eosinophil count of 860 cells/µL. After 3 years of minimal response to mepolizumab, she was started on dupilumab. Within 2 weeks of the first dose of dupilumab, she started experiencing bilateral knee pain. She subsequently developed daily fevers (temperature, 38.3 °C to 39.4 °C), fatigue, and pain in the back of the neck and head. After the second dose of dupilumab, she started experiencing painful skin lesions on the bilateral knuckles, elbows, and abdomen (Figure 1). She had difficulty using her hands and walking secondary to intense arthralgia involving the bilateral finger joints, elbows, and knees. Her primary care physician obtained a laboratory evaluation, which revealed an elevated total white blood cell count of 20×103/mm3 (reference range, 4–11×103/mm3) with 27.5% neutrophils and severely elevated eosinophils above her baseline to 57.3% with an absolute eosinophil count of 11,700 cells/µL (reference range, <400 cells/µL). Further assessment revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 64 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level of 34 mg/dL (reference range, ≤0.80 mg/dL), with negative antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, and Lyme antibody. IgG, IgA, and IgM levels were within reference range, and the IgE level was not elevated above her baseline. She had normal serum tryptase, and a peripheral D816V c-KIT mutation was not detected. She was subsequently hospitalized for further evaluation, at which time there was no fever or localizing infectious signs or symptoms. An infectious evaluation including urinalysis; respiratory swab for adenovirus, coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus/enterovirus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae; Lyme serology; and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no evidence of infection. A parasite evaluation was ordered but was not performed. There was no evidence of malignancy on CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or CT of the head without contrast. A lumbar puncture was considered but was ultimately deferred.

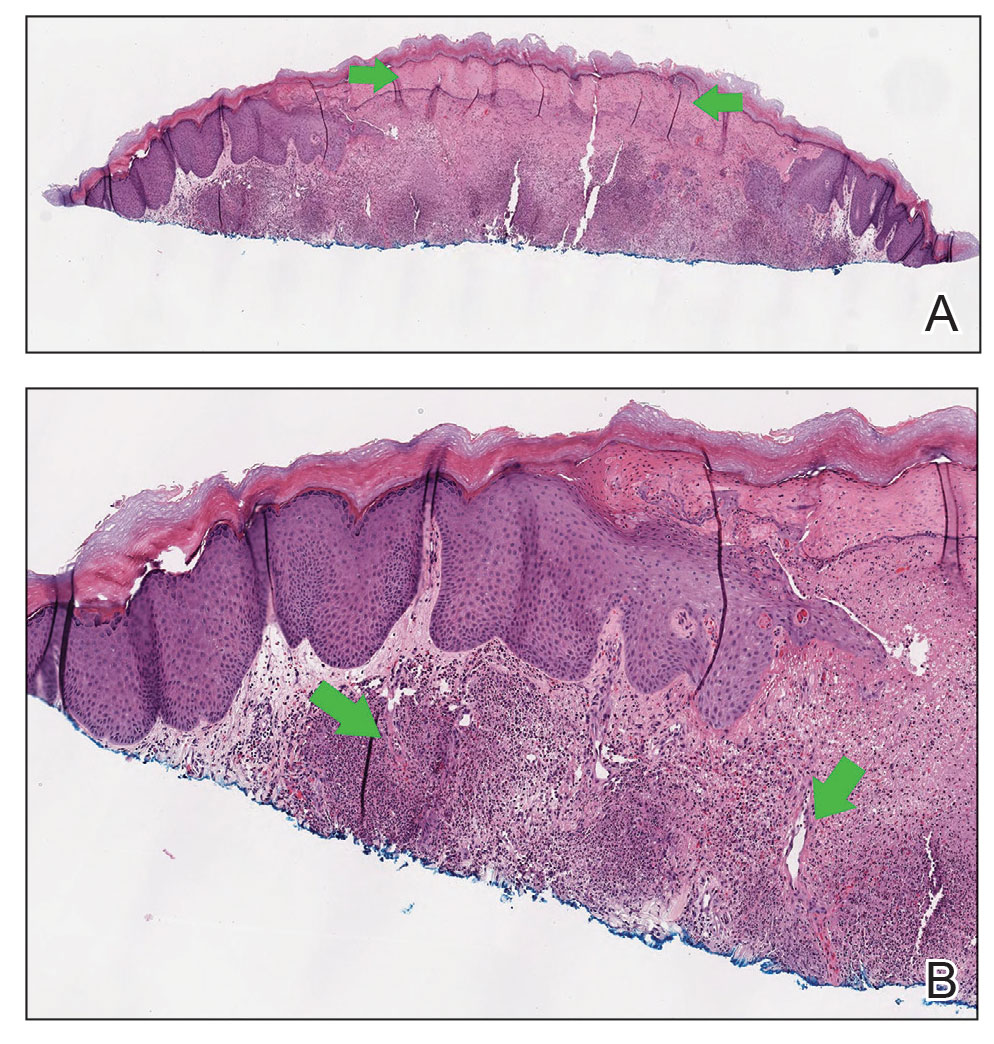

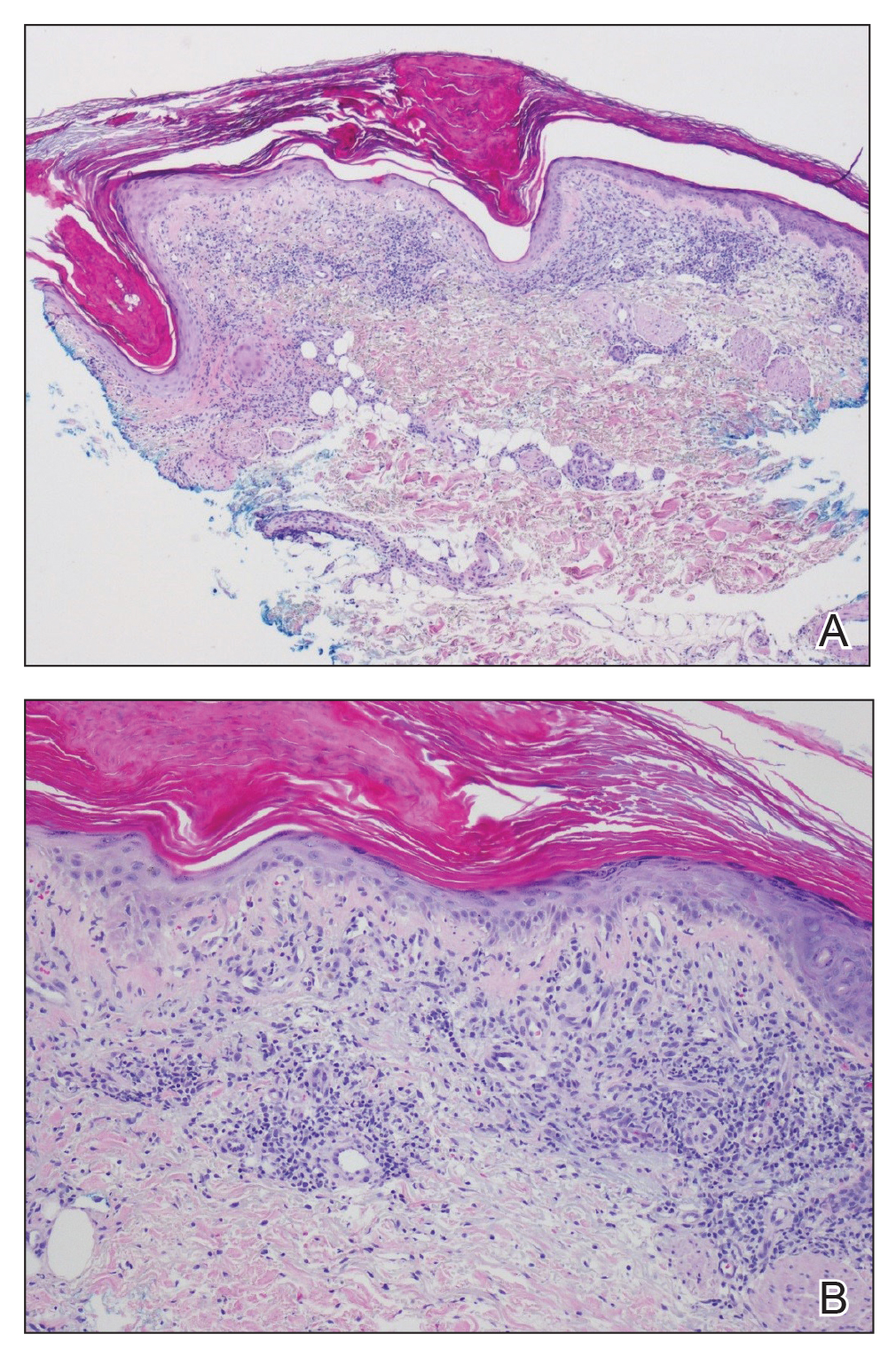

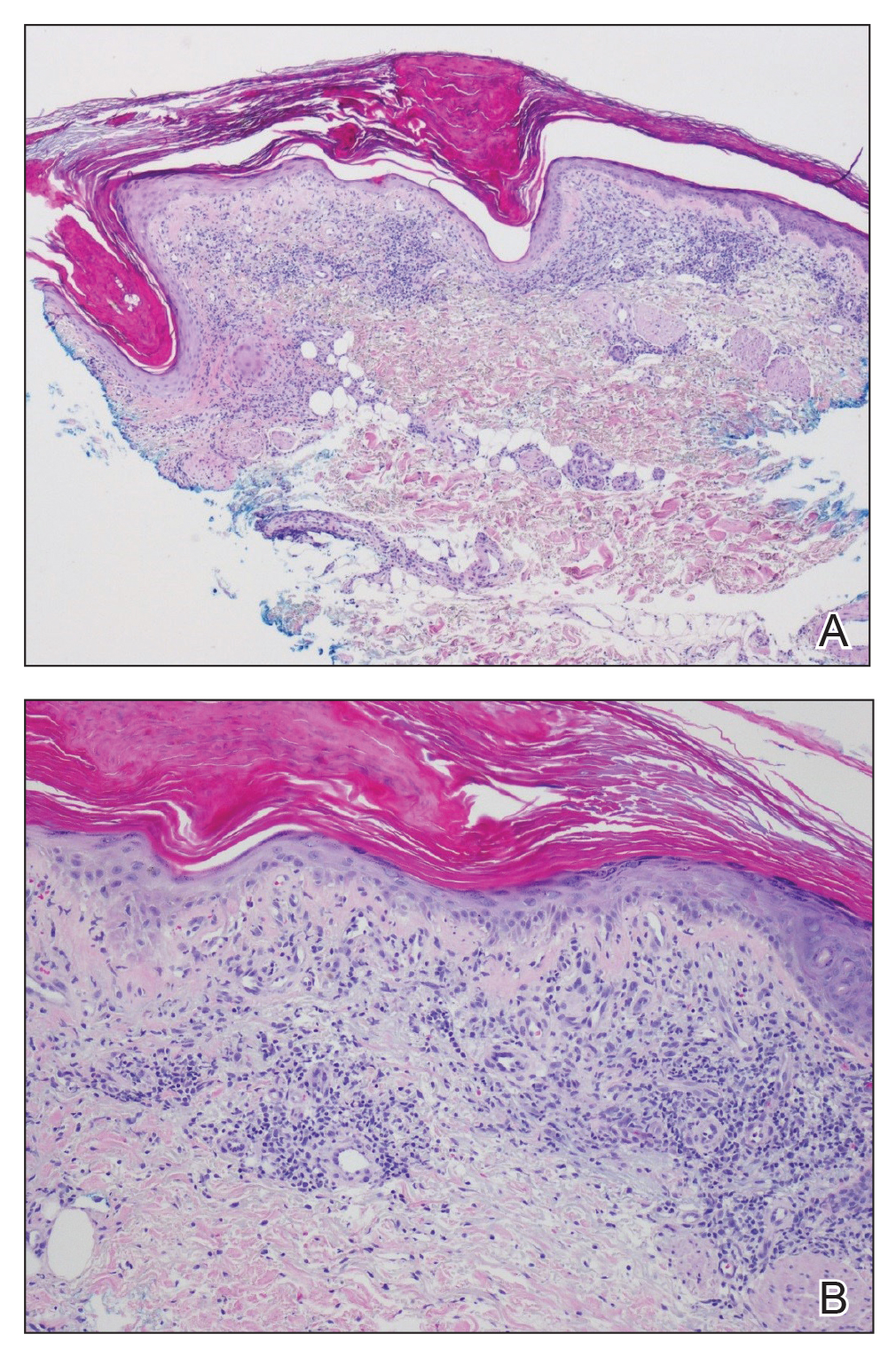

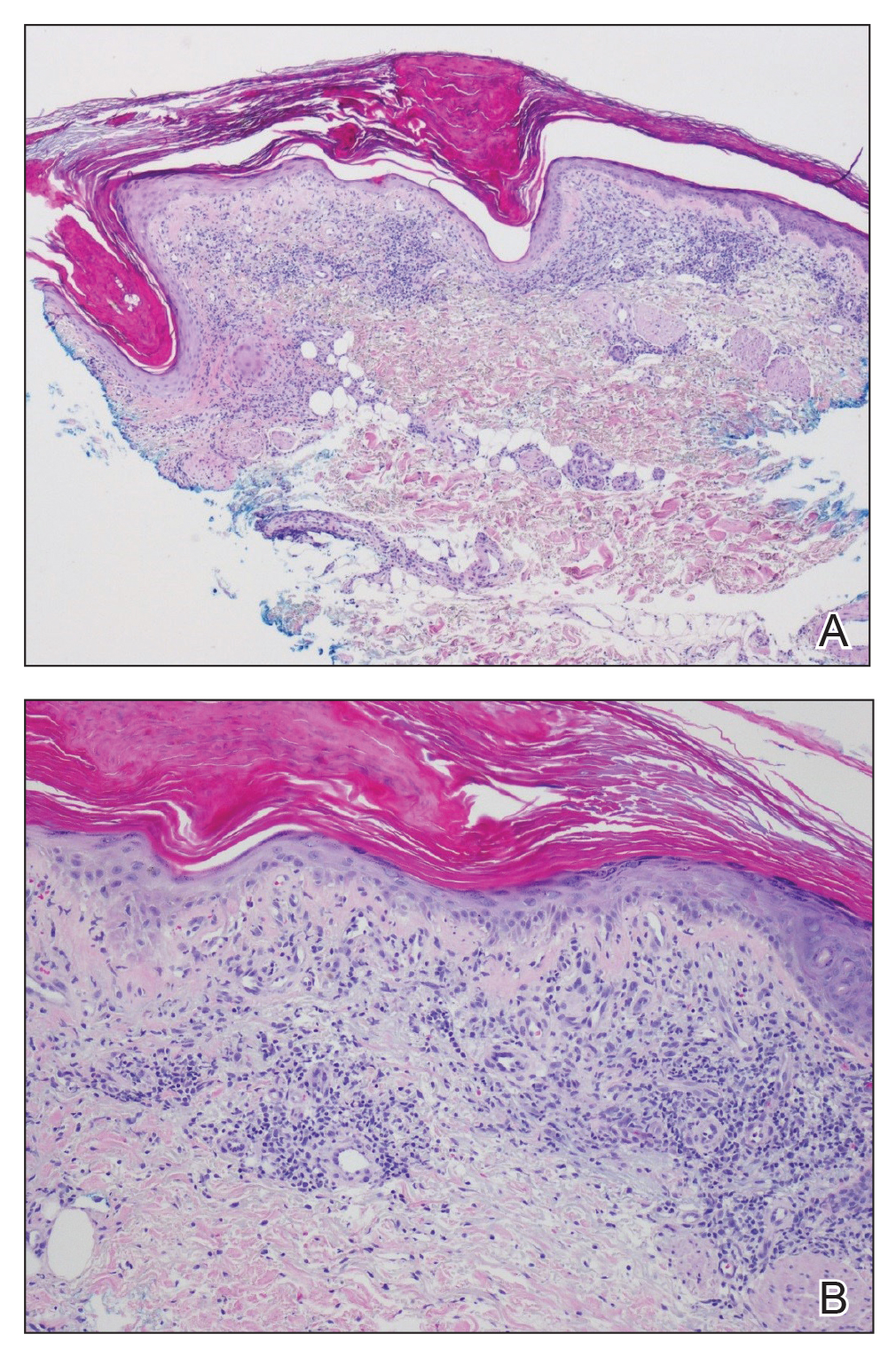

At the current presentation, the patient was following up in the dermatology clinic shortly after discharge. The lesions on the fingers and arms were described by the dermatologist as deep, erythematous, 0.5-cm bullous papules. The differential diagnosis at this time included a cutaneous or systemic infection, vasculitis, drug eruption, or cutaneous manifestation of an autoimmune condition. A shave biopsy of a skin lesion on the right hand demonstrated epidermal necrosis with a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis (Figure 2). There was no evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The histologic differential diagnosis included cutaneous infection, neutrophilic dermatosis of the hand, and SS. Special stains for infectious organisms including Gram, Grocott methenamine-silver, and auramine-rhodamine stains were negative for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial organisms, ruling out cutaneous infection. A diagnosis of drug-induced SS was made based on the histologic findings, diffuse distribution of the lesions, negative infectious evaluation, lack of underlying malignancy or autoimmune conditions, and onset following initiation of dupilumab.

Dupilumab was discontinued, and the patient was started on prednisone with rapid improvement in the symptoms. She underwent a slow taper of the prednisone over approximately 2 months with a slow downtrend of eosinophils. She was transitioned to a different biologic agent, benralizumab, with no further recurrence of the rash or arthralgia.

Comment

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal IgG4 antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling by binding to the IL-4Rα subunit. By blocking IL-4Rα, dupilumab inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine-induced inflammatory responses, including the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, nitric oxide, and IgE. Currently, dupilumab is approved to treat refractory forms of moderate to severe asthma characterized by an eosinophilic phenotype or with corticosteroid-dependent asthma, moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, and eosinophilic esophagitis. The most common adverse events (incidence ≥1%) are injection-site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and eosinophilia.5 Interestingly, our patient did exhibit a high degree of eosinophilia; however, she met all criteria for drug-induced SS, and the skin biopsy was not consistent with an eosinophilic process. Notably, the peripheral neutrophils were not elevated. Neutrophilia often is seen in classic SS but is not required for a diagnosis of drug-induced SS. Rare cases of dupilumab-associated arthritis and serum sickness–like reaction have been described,6-8 but our patient’s presentation was distinct, given other described signs, symptoms, and skin biopsy results. Histopathology results were not consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a potential mimicker of SS. Although the infectious and paraneoplastic evaluation was not exhaustive, the negative imaging from head to pelvis, the lack of recurrence of skin lesions, and the laboratory abnormalities after dupilumab discontinuation supported the conclusion that the culprit was not an infection or underlying malignancy. She had not started any other medications during this time frame, leaving dupilumab as the most likely offending agent. The mechanism for this reaction is not clear. It is possible that inhibition of IL-4 and IL-13 in the T helper 2 (TH2) cell pathway may have led to upregulated IL-17–mediated inflammation9 as well as a neutrophilic process in the skin, but this would not explain the concurrent peripheral eosinophilia that was noted. Further studies are needed to investigate the pathophysiology of SS.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of dupilumab-induced SS. Corticosteroids accompanied by cessation of the medication proved to be an effective treatment.

- Sweet RB. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Jackson K, Bahna SL. Hypersensitivity and adverse reactions to biologics for asthma and allergic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:311-319.

- Willsmore ZN, Woolf RT, Hughes C, et al. Development of inflammatory arthritis and enthesitis in patients on dupilumab: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1068-1070.

- de Wijs LEM, van der Waa JD, de Jong PHP, et al. Acute arthritis and arthralgia as an adverse drug reaction to dupilumab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:262-263.

- Treudler R, Delaroque N, Puder M, et al. Dupilumab-induced serum sickness-like reaction: an unusual adverse effect in a patient with atopic eczema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E30-E32.

- Guenova E, Skabytska Y, Hoetzenecker W, et al. IL-4 abrogates TH17 cell-mediated inflammation by selective silencing of IL-23 in antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2163-2168.

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, was first described in 1964. 1 Since then, several subtypes of SS have been recognized, including classic or idiopathic, which typically follows an acute viral illness; cancer related, typically in the form of a paraneoplastic syndrome; and drug induced. 2 Drug-induced SS is defined by the following: (1) an abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules; (2) histopathologic evidence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; (3) pyrexia above 38 ° C; (4) temporal relationship between drug and clinical presentation or temporally related recurrence after rechallenge; and (5) temporally related resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids. 3 All 5 criteria must be met to make a diagnosis of drug-induced SS. Since these criteria were established by Walker and Cohen, 3 various drugs have been identified as causative agents, including antibiotics, antiepileptics, antiretrovirals, antineoplastic agents, antipsychotics, oral contraceptives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids. 4 W e present a rare case of SS caused by dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody therapy, used in the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma and atopic dermatitis.

Case Report

A 53-year-old woman presented with painful skin lesions, arthralgia, fever, and leukocytosis following initiation of dupilumab. She had a history of adult-onset, severe, persistent eosinophilic asthma, as well as chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, plaque psoriasis, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. She started mepolizumab 3 years prior to the current presentation for persistently uncontrolled asthma with a baseline peripheral eosinophil count of 860 cells/µL. After 3 years of minimal response to mepolizumab, she was started on dupilumab. Within 2 weeks of the first dose of dupilumab, she started experiencing bilateral knee pain. She subsequently developed daily fevers (temperature, 38.3 °C to 39.4 °C), fatigue, and pain in the back of the neck and head. After the second dose of dupilumab, she started experiencing painful skin lesions on the bilateral knuckles, elbows, and abdomen (Figure 1). She had difficulty using her hands and walking secondary to intense arthralgia involving the bilateral finger joints, elbows, and knees. Her primary care physician obtained a laboratory evaluation, which revealed an elevated total white blood cell count of 20×103/mm3 (reference range, 4–11×103/mm3) with 27.5% neutrophils and severely elevated eosinophils above her baseline to 57.3% with an absolute eosinophil count of 11,700 cells/µL (reference range, <400 cells/µL). Further assessment revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 64 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level of 34 mg/dL (reference range, ≤0.80 mg/dL), with negative antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, and Lyme antibody. IgG, IgA, and IgM levels were within reference range, and the IgE level was not elevated above her baseline. She had normal serum tryptase, and a peripheral D816V c-KIT mutation was not detected. She was subsequently hospitalized for further evaluation, at which time there was no fever or localizing infectious signs or symptoms. An infectious evaluation including urinalysis; respiratory swab for adenovirus, coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus/enterovirus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae; Lyme serology; and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no evidence of infection. A parasite evaluation was ordered but was not performed. There was no evidence of malignancy on CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or CT of the head without contrast. A lumbar puncture was considered but was ultimately deferred.

At the current presentation, the patient was following up in the dermatology clinic shortly after discharge. The lesions on the fingers and arms were described by the dermatologist as deep, erythematous, 0.5-cm bullous papules. The differential diagnosis at this time included a cutaneous or systemic infection, vasculitis, drug eruption, or cutaneous manifestation of an autoimmune condition. A shave biopsy of a skin lesion on the right hand demonstrated epidermal necrosis with a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis (Figure 2). There was no evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The histologic differential diagnosis included cutaneous infection, neutrophilic dermatosis of the hand, and SS. Special stains for infectious organisms including Gram, Grocott methenamine-silver, and auramine-rhodamine stains were negative for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial organisms, ruling out cutaneous infection. A diagnosis of drug-induced SS was made based on the histologic findings, diffuse distribution of the lesions, negative infectious evaluation, lack of underlying malignancy or autoimmune conditions, and onset following initiation of dupilumab.

Dupilumab was discontinued, and the patient was started on prednisone with rapid improvement in the symptoms. She underwent a slow taper of the prednisone over approximately 2 months with a slow downtrend of eosinophils. She was transitioned to a different biologic agent, benralizumab, with no further recurrence of the rash or arthralgia.

Comment

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal IgG4 antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling by binding to the IL-4Rα subunit. By blocking IL-4Rα, dupilumab inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine-induced inflammatory responses, including the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, nitric oxide, and IgE. Currently, dupilumab is approved to treat refractory forms of moderate to severe asthma characterized by an eosinophilic phenotype or with corticosteroid-dependent asthma, moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, and eosinophilic esophagitis. The most common adverse events (incidence ≥1%) are injection-site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and eosinophilia.5 Interestingly, our patient did exhibit a high degree of eosinophilia; however, she met all criteria for drug-induced SS, and the skin biopsy was not consistent with an eosinophilic process. Notably, the peripheral neutrophils were not elevated. Neutrophilia often is seen in classic SS but is not required for a diagnosis of drug-induced SS. Rare cases of dupilumab-associated arthritis and serum sickness–like reaction have been described,6-8 but our patient’s presentation was distinct, given other described signs, symptoms, and skin biopsy results. Histopathology results were not consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a potential mimicker of SS. Although the infectious and paraneoplastic evaluation was not exhaustive, the negative imaging from head to pelvis, the lack of recurrence of skin lesions, and the laboratory abnormalities after dupilumab discontinuation supported the conclusion that the culprit was not an infection or underlying malignancy. She had not started any other medications during this time frame, leaving dupilumab as the most likely offending agent. The mechanism for this reaction is not clear. It is possible that inhibition of IL-4 and IL-13 in the T helper 2 (TH2) cell pathway may have led to upregulated IL-17–mediated inflammation9 as well as a neutrophilic process in the skin, but this would not explain the concurrent peripheral eosinophilia that was noted. Further studies are needed to investigate the pathophysiology of SS.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of dupilumab-induced SS. Corticosteroids accompanied by cessation of the medication proved to be an effective treatment.

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, was first described in 1964. 1 Since then, several subtypes of SS have been recognized, including classic or idiopathic, which typically follows an acute viral illness; cancer related, typically in the form of a paraneoplastic syndrome; and drug induced. 2 Drug-induced SS is defined by the following: (1) an abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules; (2) histopathologic evidence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; (3) pyrexia above 38 ° C; (4) temporal relationship between drug and clinical presentation or temporally related recurrence after rechallenge; and (5) temporally related resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids. 3 All 5 criteria must be met to make a diagnosis of drug-induced SS. Since these criteria were established by Walker and Cohen, 3 various drugs have been identified as causative agents, including antibiotics, antiepileptics, antiretrovirals, antineoplastic agents, antipsychotics, oral contraceptives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids. 4 W e present a rare case of SS caused by dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody therapy, used in the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma and atopic dermatitis.

Case Report

A 53-year-old woman presented with painful skin lesions, arthralgia, fever, and leukocytosis following initiation of dupilumab. She had a history of adult-onset, severe, persistent eosinophilic asthma, as well as chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, plaque psoriasis, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. She started mepolizumab 3 years prior to the current presentation for persistently uncontrolled asthma with a baseline peripheral eosinophil count of 860 cells/µL. After 3 years of minimal response to mepolizumab, she was started on dupilumab. Within 2 weeks of the first dose of dupilumab, she started experiencing bilateral knee pain. She subsequently developed daily fevers (temperature, 38.3 °C to 39.4 °C), fatigue, and pain in the back of the neck and head. After the second dose of dupilumab, she started experiencing painful skin lesions on the bilateral knuckles, elbows, and abdomen (Figure 1). She had difficulty using her hands and walking secondary to intense arthralgia involving the bilateral finger joints, elbows, and knees. Her primary care physician obtained a laboratory evaluation, which revealed an elevated total white blood cell count of 20×103/mm3 (reference range, 4–11×103/mm3) with 27.5% neutrophils and severely elevated eosinophils above her baseline to 57.3% with an absolute eosinophil count of 11,700 cells/µL (reference range, <400 cells/µL). Further assessment revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 64 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level of 34 mg/dL (reference range, ≤0.80 mg/dL), with negative antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, and Lyme antibody. IgG, IgA, and IgM levels were within reference range, and the IgE level was not elevated above her baseline. She had normal serum tryptase, and a peripheral D816V c-KIT mutation was not detected. She was subsequently hospitalized for further evaluation, at which time there was no fever or localizing infectious signs or symptoms. An infectious evaluation including urinalysis; respiratory swab for adenovirus, coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus/enterovirus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae; Lyme serology; and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no evidence of infection. A parasite evaluation was ordered but was not performed. There was no evidence of malignancy on CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or CT of the head without contrast. A lumbar puncture was considered but was ultimately deferred.

At the current presentation, the patient was following up in the dermatology clinic shortly after discharge. The lesions on the fingers and arms were described by the dermatologist as deep, erythematous, 0.5-cm bullous papules. The differential diagnosis at this time included a cutaneous or systemic infection, vasculitis, drug eruption, or cutaneous manifestation of an autoimmune condition. A shave biopsy of a skin lesion on the right hand demonstrated epidermal necrosis with a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis (Figure 2). There was no evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The histologic differential diagnosis included cutaneous infection, neutrophilic dermatosis of the hand, and SS. Special stains for infectious organisms including Gram, Grocott methenamine-silver, and auramine-rhodamine stains were negative for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial organisms, ruling out cutaneous infection. A diagnosis of drug-induced SS was made based on the histologic findings, diffuse distribution of the lesions, negative infectious evaluation, lack of underlying malignancy or autoimmune conditions, and onset following initiation of dupilumab.

Dupilumab was discontinued, and the patient was started on prednisone with rapid improvement in the symptoms. She underwent a slow taper of the prednisone over approximately 2 months with a slow downtrend of eosinophils. She was transitioned to a different biologic agent, benralizumab, with no further recurrence of the rash or arthralgia.

Comment

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal IgG4 antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling by binding to the IL-4Rα subunit. By blocking IL-4Rα, dupilumab inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine-induced inflammatory responses, including the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, nitric oxide, and IgE. Currently, dupilumab is approved to treat refractory forms of moderate to severe asthma characterized by an eosinophilic phenotype or with corticosteroid-dependent asthma, moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, and eosinophilic esophagitis. The most common adverse events (incidence ≥1%) are injection-site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and eosinophilia.5 Interestingly, our patient did exhibit a high degree of eosinophilia; however, she met all criteria for drug-induced SS, and the skin biopsy was not consistent with an eosinophilic process. Notably, the peripheral neutrophils were not elevated. Neutrophilia often is seen in classic SS but is not required for a diagnosis of drug-induced SS. Rare cases of dupilumab-associated arthritis and serum sickness–like reaction have been described,6-8 but our patient’s presentation was distinct, given other described signs, symptoms, and skin biopsy results. Histopathology results were not consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a potential mimicker of SS. Although the infectious and paraneoplastic evaluation was not exhaustive, the negative imaging from head to pelvis, the lack of recurrence of skin lesions, and the laboratory abnormalities after dupilumab discontinuation supported the conclusion that the culprit was not an infection or underlying malignancy. She had not started any other medications during this time frame, leaving dupilumab as the most likely offending agent. The mechanism for this reaction is not clear. It is possible that inhibition of IL-4 and IL-13 in the T helper 2 (TH2) cell pathway may have led to upregulated IL-17–mediated inflammation9 as well as a neutrophilic process in the skin, but this would not explain the concurrent peripheral eosinophilia that was noted. Further studies are needed to investigate the pathophysiology of SS.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of dupilumab-induced SS. Corticosteroids accompanied by cessation of the medication proved to be an effective treatment.

- Sweet RB. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Jackson K, Bahna SL. Hypersensitivity and adverse reactions to biologics for asthma and allergic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:311-319.

- Willsmore ZN, Woolf RT, Hughes C, et al. Development of inflammatory arthritis and enthesitis in patients on dupilumab: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1068-1070.

- de Wijs LEM, van der Waa JD, de Jong PHP, et al. Acute arthritis and arthralgia as an adverse drug reaction to dupilumab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:262-263.

- Treudler R, Delaroque N, Puder M, et al. Dupilumab-induced serum sickness-like reaction: an unusual adverse effect in a patient with atopic eczema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E30-E32.

- Guenova E, Skabytska Y, Hoetzenecker W, et al. IL-4 abrogates TH17 cell-mediated inflammation by selective silencing of IL-23 in antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2163-2168.

- Sweet RB. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Jackson K, Bahna SL. Hypersensitivity and adverse reactions to biologics for asthma and allergic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:311-319.

- Willsmore ZN, Woolf RT, Hughes C, et al. Development of inflammatory arthritis and enthesitis in patients on dupilumab: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1068-1070.

- de Wijs LEM, van der Waa JD, de Jong PHP, et al. Acute arthritis and arthralgia as an adverse drug reaction to dupilumab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:262-263.

- Treudler R, Delaroque N, Puder M, et al. Dupilumab-induced serum sickness-like reaction: an unusual adverse effect in a patient with atopic eczema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E30-E32.

- Guenova E, Skabytska Y, Hoetzenecker W, et al. IL-4 abrogates TH17 cell-mediated inflammation by selective silencing of IL-23 in antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2163-2168.

Practice Points

- Prescribers of dupilumab should be aware that Sweet syndrome is a potential adverse reaction.

- Sweet syndrome should be suspected if there is abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules accompanied by pyrexia following injection of dupilumab. Biopsy of the nodules should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis.

- Systemic corticosteroids with cessation of dupilumab are effective treatments.

- Following treatment, dupilumab should not be reinitiated, and alternative therapies should be used.

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus–like Isotopic Response to Herpes Zoster Infection

To the Editor:

Wolf isotopic response describes the development of a skin disorder at the site of another healed and unrelated skin disease. Skin disorders presenting as isotopic responses have included inflammatory, malignant, granulomatous, and infectious processes. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a rare isotopic response. We report a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that presented at the site of a recent herpes zoster infection in a liver transplant recipient.

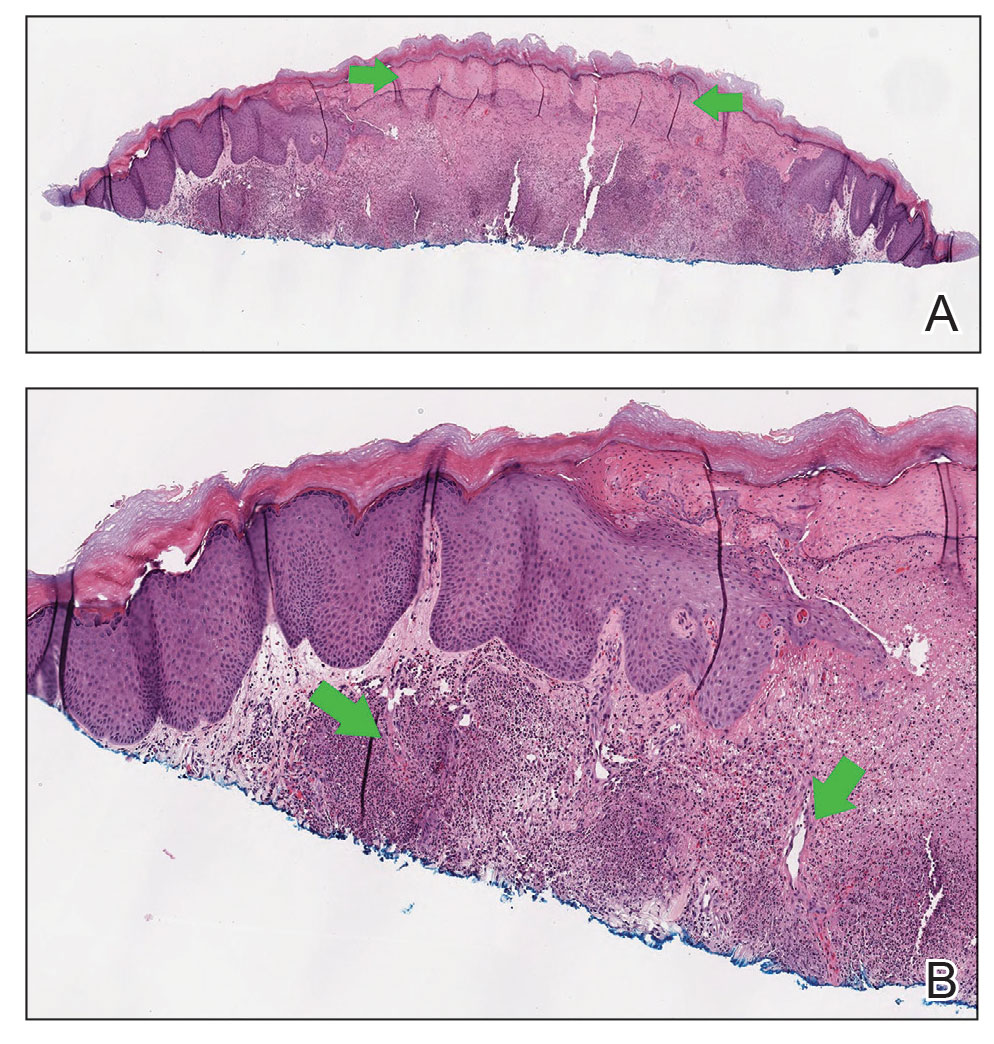

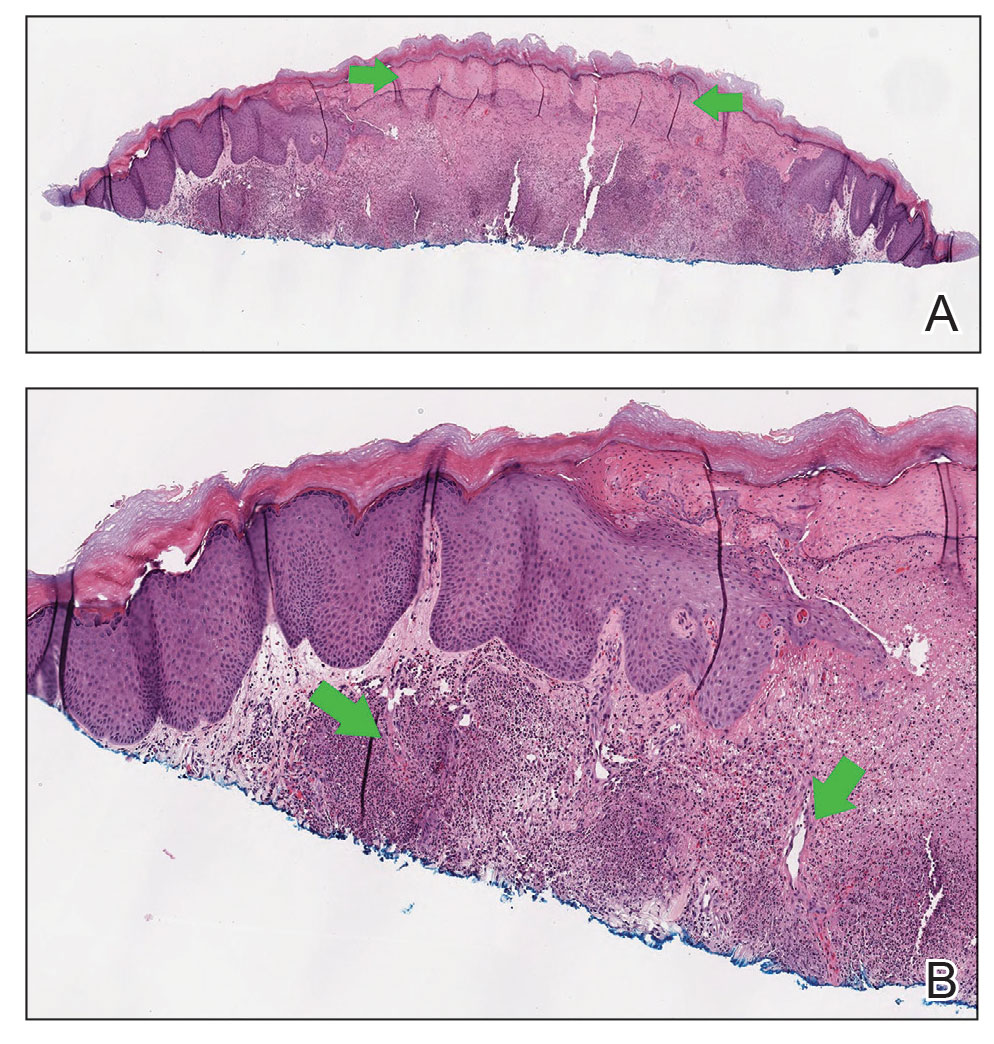

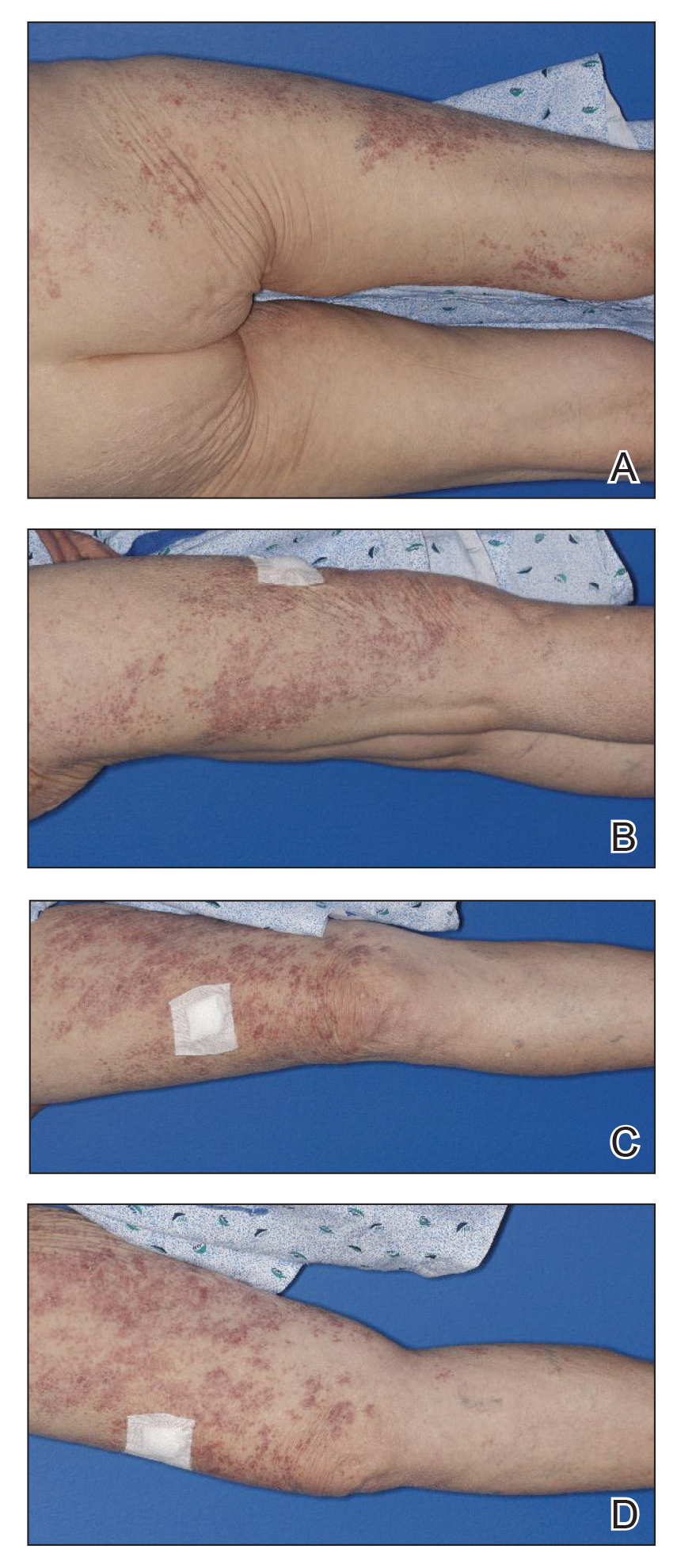

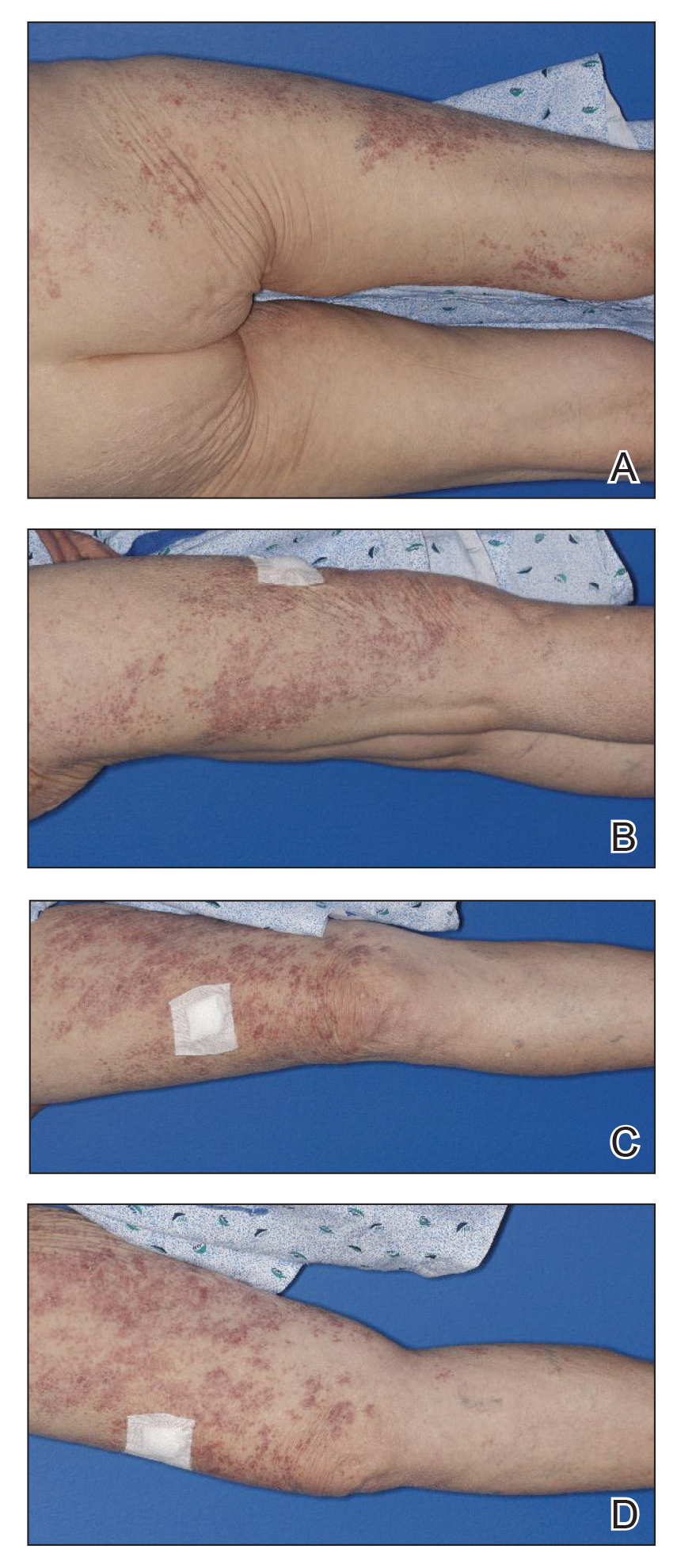

A 74-year-old immunocompromised woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the right leg. She was being treated with maintenance valganciclovir due to cytomegalovirus viremia, as well as tacrolimus, azathioprine, and prednisone following liver transplantation due to autoimmune hepatitis for 8 months prior to presentation. Eighteen days prior to the current presentation, she was clinically diagnosed with herpes zoster. As the grouped vesicles from the herpes zoster resolved, she developed pink scaly papules in the same distribution as the original vesicular eruption.

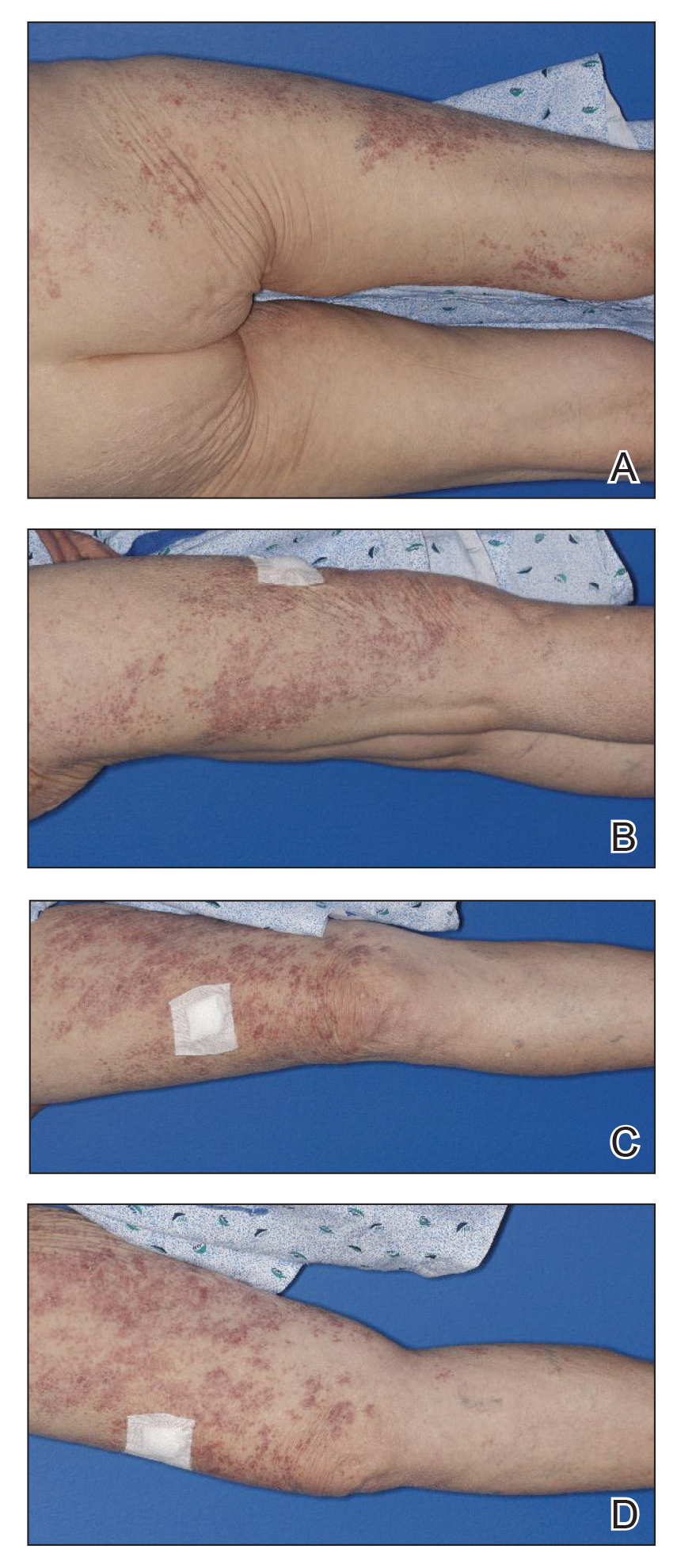

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, 2- to 3-mm, scaly papules that coalesced into small plaques with serous crusts; they originated above the supragluteal cleft and extended rightward in the L3 and L4 dermatomes to the right knee (Figure 1). A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right anterior thigh. Histologic analysis revealed interface lymphocytic inflammation with squamatization of basal keratinocytes, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging by keratin (Figure 2). There was a moderately intense perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate of mature lymphocytes with rare eosinophils within the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. There was no evidence of a viral cytopathic effect, and an immunohistochemical stain for varicella-zoster virus protein was negative. The histologic findings were suggestive of cutaneous involvement by DLE. A diagnosis of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like Wolf isotopic response was made, and the patient’s rash resolved with the use of triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied twice daily for 2 weeks. At 6-week follow-up, there were postinflammatory pigmentation changes at the sites of the prior rash and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Recent antinuclear antibody screening was negative, coupled with the patient’s lack of systemic symptoms and quick resolution of rash, indicating that additional testing for systemic lupus was not warranted.

Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder. The second disease may appear within days to years after the primary disease subsides and is clearly differentiated from the isomorphic response of the Koebner phenomenon, which describes an established skin disorder appearing at a previously uninvolved anatomic site following trauma.1 As in our case, the initial cutaneous eruption resulting in a subsequent Wolf isotopic response frequently is herpes zoster and less commonly is herpes simplex virus.2 The most common reported isotopic response is a granulomatous reaction.2 Rare reports of leukemic infiltration, lymphoma, lichen planus, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus, lichen simplex chronicus, contact dermatitis, xanthomatous changes, malignant tumors, cutaneous graft-vs-host disease, pityriasis rosea, erythema annulare centrifugum, and other infectious-based isotopic responses exist.2-6

Our patient presented with Wolf isotopic response that histologically mimicked DLE. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotopic response and lupus revealed only 3 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as an isotopic response in the English-language literature. One of those cases occurred in a patient with preexisting systemic lupus erythematosus, making a diagnosis of Koebner isomorphic phenomenon more appropriate than an isotopic response at the site of prior herpes zoster infection.7 The remaining 2 cases were clinically defined DLE lesions occurring at sites of prior infection—cutaneous leishmaniasis and herpes zoster—in patients without a prior history of cutaneous or systemic lupus erythematosus.8,9 The latter case of DLE-like isotopic response occurring after herpes zoster infection was further complicated by local injections at the zoster site for herpes-related local pain. Injection sites are reported as a distinct nidus for Wolf isotopic response.9

The pathogenesis of Wolf isotopic response is unclear. Possible explanations include local interactions between persistent viral particles at prior herpes infection sites, vascular injury, neural injury, and an altered immune response.1,5,6,10 The destruction of sensory nerve fibers by herpesviruses cause the release of neuropeptides that then modulate the local immune system and angiogenic responses.5,6 Our patient’s immunocompromised state may have further propagated a local altered immune cell infiltrate at the site of the isotopic response. Despite its unclear etiology, Wolf isotopic response should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with a dermatomal eruption at the site of a prior cutaneous infection, particularly after infection with herpes zoster. Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses with an excellent prognosis.11

We present a case of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that occurred at the site of a recent herpes zoster eruption in an immunocompromised patient without prior history of systemic or cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinical recognition of Wolf isotopic response is important for accurate histopathologic diagnosis and management. Continued investigation into the underlying pathogenesis should be performed to fully understand and better treat this process.

- Sharma RC, Sharma NL, Mahajan V, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: herpes simplex appearing on scrofuloderma scar. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:664-666.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. “Wolf’s isotopic response”: the originators speak their mind and set the record straight. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:416-418.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:110-113.

- Bardazzi F, Giacomini F, Savoia F, et al. Discoid chronic lupus erythematosus at the site of a previously healed cutaneous leishmaniasis: an example of isotopic response. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:44-46.

- Parimalam K, Kumar D, Thomas J. Discoid lupus erythematosis occurring as an isotopic response. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:50-51.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al. Viral diseases. In: James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020:362-420.

To the Editor:

Wolf isotopic response describes the development of a skin disorder at the site of another healed and unrelated skin disease. Skin disorders presenting as isotopic responses have included inflammatory, malignant, granulomatous, and infectious processes. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a rare isotopic response. We report a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that presented at the site of a recent herpes zoster infection in a liver transplant recipient.

A 74-year-old immunocompromised woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the right leg. She was being treated with maintenance valganciclovir due to cytomegalovirus viremia, as well as tacrolimus, azathioprine, and prednisone following liver transplantation due to autoimmune hepatitis for 8 months prior to presentation. Eighteen days prior to the current presentation, she was clinically diagnosed with herpes zoster. As the grouped vesicles from the herpes zoster resolved, she developed pink scaly papules in the same distribution as the original vesicular eruption.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, 2- to 3-mm, scaly papules that coalesced into small plaques with serous crusts; they originated above the supragluteal cleft and extended rightward in the L3 and L4 dermatomes to the right knee (Figure 1). A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right anterior thigh. Histologic analysis revealed interface lymphocytic inflammation with squamatization of basal keratinocytes, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging by keratin (Figure 2). There was a moderately intense perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate of mature lymphocytes with rare eosinophils within the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. There was no evidence of a viral cytopathic effect, and an immunohistochemical stain for varicella-zoster virus protein was negative. The histologic findings were suggestive of cutaneous involvement by DLE. A diagnosis of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like Wolf isotopic response was made, and the patient’s rash resolved with the use of triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied twice daily for 2 weeks. At 6-week follow-up, there were postinflammatory pigmentation changes at the sites of the prior rash and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Recent antinuclear antibody screening was negative, coupled with the patient’s lack of systemic symptoms and quick resolution of rash, indicating that additional testing for systemic lupus was not warranted.

Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder. The second disease may appear within days to years after the primary disease subsides and is clearly differentiated from the isomorphic response of the Koebner phenomenon, which describes an established skin disorder appearing at a previously uninvolved anatomic site following trauma.1 As in our case, the initial cutaneous eruption resulting in a subsequent Wolf isotopic response frequently is herpes zoster and less commonly is herpes simplex virus.2 The most common reported isotopic response is a granulomatous reaction.2 Rare reports of leukemic infiltration, lymphoma, lichen planus, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus, lichen simplex chronicus, contact dermatitis, xanthomatous changes, malignant tumors, cutaneous graft-vs-host disease, pityriasis rosea, erythema annulare centrifugum, and other infectious-based isotopic responses exist.2-6

Our patient presented with Wolf isotopic response that histologically mimicked DLE. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotopic response and lupus revealed only 3 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as an isotopic response in the English-language literature. One of those cases occurred in a patient with preexisting systemic lupus erythematosus, making a diagnosis of Koebner isomorphic phenomenon more appropriate than an isotopic response at the site of prior herpes zoster infection.7 The remaining 2 cases were clinically defined DLE lesions occurring at sites of prior infection—cutaneous leishmaniasis and herpes zoster—in patients without a prior history of cutaneous or systemic lupus erythematosus.8,9 The latter case of DLE-like isotopic response occurring after herpes zoster infection was further complicated by local injections at the zoster site for herpes-related local pain. Injection sites are reported as a distinct nidus for Wolf isotopic response.9

The pathogenesis of Wolf isotopic response is unclear. Possible explanations include local interactions between persistent viral particles at prior herpes infection sites, vascular injury, neural injury, and an altered immune response.1,5,6,10 The destruction of sensory nerve fibers by herpesviruses cause the release of neuropeptides that then modulate the local immune system and angiogenic responses.5,6 Our patient’s immunocompromised state may have further propagated a local altered immune cell infiltrate at the site of the isotopic response. Despite its unclear etiology, Wolf isotopic response should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with a dermatomal eruption at the site of a prior cutaneous infection, particularly after infection with herpes zoster. Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses with an excellent prognosis.11

We present a case of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that occurred at the site of a recent herpes zoster eruption in an immunocompromised patient without prior history of systemic or cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinical recognition of Wolf isotopic response is important for accurate histopathologic diagnosis and management. Continued investigation into the underlying pathogenesis should be performed to fully understand and better treat this process.

To the Editor:

Wolf isotopic response describes the development of a skin disorder at the site of another healed and unrelated skin disease. Skin disorders presenting as isotopic responses have included inflammatory, malignant, granulomatous, and infectious processes. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a rare isotopic response. We report a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that presented at the site of a recent herpes zoster infection in a liver transplant recipient.

A 74-year-old immunocompromised woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the right leg. She was being treated with maintenance valganciclovir due to cytomegalovirus viremia, as well as tacrolimus, azathioprine, and prednisone following liver transplantation due to autoimmune hepatitis for 8 months prior to presentation. Eighteen days prior to the current presentation, she was clinically diagnosed with herpes zoster. As the grouped vesicles from the herpes zoster resolved, she developed pink scaly papules in the same distribution as the original vesicular eruption.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, 2- to 3-mm, scaly papules that coalesced into small plaques with serous crusts; they originated above the supragluteal cleft and extended rightward in the L3 and L4 dermatomes to the right knee (Figure 1). A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right anterior thigh. Histologic analysis revealed interface lymphocytic inflammation with squamatization of basal keratinocytes, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging by keratin (Figure 2). There was a moderately intense perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate of mature lymphocytes with rare eosinophils within the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. There was no evidence of a viral cytopathic effect, and an immunohistochemical stain for varicella-zoster virus protein was negative. The histologic findings were suggestive of cutaneous involvement by DLE. A diagnosis of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like Wolf isotopic response was made, and the patient’s rash resolved with the use of triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied twice daily for 2 weeks. At 6-week follow-up, there were postinflammatory pigmentation changes at the sites of the prior rash and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Recent antinuclear antibody screening was negative, coupled with the patient’s lack of systemic symptoms and quick resolution of rash, indicating that additional testing for systemic lupus was not warranted.

Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder. The second disease may appear within days to years after the primary disease subsides and is clearly differentiated from the isomorphic response of the Koebner phenomenon, which describes an established skin disorder appearing at a previously uninvolved anatomic site following trauma.1 As in our case, the initial cutaneous eruption resulting in a subsequent Wolf isotopic response frequently is herpes zoster and less commonly is herpes simplex virus.2 The most common reported isotopic response is a granulomatous reaction.2 Rare reports of leukemic infiltration, lymphoma, lichen planus, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus, lichen simplex chronicus, contact dermatitis, xanthomatous changes, malignant tumors, cutaneous graft-vs-host disease, pityriasis rosea, erythema annulare centrifugum, and other infectious-based isotopic responses exist.2-6

Our patient presented with Wolf isotopic response that histologically mimicked DLE. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotopic response and lupus revealed only 3 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as an isotopic response in the English-language literature. One of those cases occurred in a patient with preexisting systemic lupus erythematosus, making a diagnosis of Koebner isomorphic phenomenon more appropriate than an isotopic response at the site of prior herpes zoster infection.7 The remaining 2 cases were clinically defined DLE lesions occurring at sites of prior infection—cutaneous leishmaniasis and herpes zoster—in patients without a prior history of cutaneous or systemic lupus erythematosus.8,9 The latter case of DLE-like isotopic response occurring after herpes zoster infection was further complicated by local injections at the zoster site for herpes-related local pain. Injection sites are reported as a distinct nidus for Wolf isotopic response.9

The pathogenesis of Wolf isotopic response is unclear. Possible explanations include local interactions between persistent viral particles at prior herpes infection sites, vascular injury, neural injury, and an altered immune response.1,5,6,10 The destruction of sensory nerve fibers by herpesviruses cause the release of neuropeptides that then modulate the local immune system and angiogenic responses.5,6 Our patient’s immunocompromised state may have further propagated a local altered immune cell infiltrate at the site of the isotopic response. Despite its unclear etiology, Wolf isotopic response should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with a dermatomal eruption at the site of a prior cutaneous infection, particularly after infection with herpes zoster. Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses with an excellent prognosis.11

We present a case of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that occurred at the site of a recent herpes zoster eruption in an immunocompromised patient without prior history of systemic or cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinical recognition of Wolf isotopic response is important for accurate histopathologic diagnosis and management. Continued investigation into the underlying pathogenesis should be performed to fully understand and better treat this process.

- Sharma RC, Sharma NL, Mahajan V, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: herpes simplex appearing on scrofuloderma scar. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:664-666.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. “Wolf’s isotopic response”: the originators speak their mind and set the record straight. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:416-418.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:110-113.

- Bardazzi F, Giacomini F, Savoia F, et al. Discoid chronic lupus erythematosus at the site of a previously healed cutaneous leishmaniasis: an example of isotopic response. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:44-46.

- Parimalam K, Kumar D, Thomas J. Discoid lupus erythematosis occurring as an isotopic response. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:50-51.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al. Viral diseases. In: James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020:362-420.

- Sharma RC, Sharma NL, Mahajan V, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: herpes simplex appearing on scrofuloderma scar. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:664-666.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. “Wolf’s isotopic response”: the originators speak their mind and set the record straight. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:416-418.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:110-113.

- Bardazzi F, Giacomini F, Savoia F, et al. Discoid chronic lupus erythematosus at the site of a previously healed cutaneous leishmaniasis: an example of isotopic response. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:44-46.

- Parimalam K, Kumar D, Thomas J. Discoid lupus erythematosis occurring as an isotopic response. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:50-51.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al. Viral diseases. In: James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020:362-420.

Practice Points

- Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin condition at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder; a granulomatous reaction is a commonly reported isotopic response.

- Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses.