User login

What makes a quality “quality measure”?

The future of health care is value-based care. If Value equals Quality divided by Cost, then a defined, validated way to measure Quality is paramount to that equation. (Fortunately, Cost comes with convenient measurement units called dollars.) Payers now are asking health care providers to shift from a fee-for-service to a value-based reimbursement structure to encourage providers to deliver the best care at the lowest cost. Providers who can embrace this data-driven paradigm will succeed in this new environment.

So how do we define high-quality care? What makes a good quality measure? How do you actually measure what happens in a clinical encounter that impacts health outcomes?

To answer these questions, organizations have constructed standardized clinical quality measures. Clinical quality measures facilitate value-based care by providing a metric on which to measure a patient’s quality of care. They can be used 1) to decrease the overuse, underuse, and misuse of health care services and 2) to measure patient engagement and satisfaction with care.

What are quality measures?

The Academy of Medicine (formerly named the Institute of Medicine) defines health care quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1

Clearly defined components and terminology. From a quantitative standpoint, quality measures must have a clearly defined numerator and denominator and appropriate inclusions, exclusions, and exceptions. These components need to be expressed clearly in terms of publicly available terminologies, such as ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes or SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms) terms. A measure that asks if “antihypertensive meds” have been given will not nearly be as specific as one that asks if “labetalol IV, or hydralazine IV, or nifedipine SL” has been administered. The decision to tie the data elements in a measure to administrative data, such as ICD codes, or to clinical data, such as SNOMED CT, also affects how these measures can be calculated.

Moving targets. The target of the measure also must carefully be considered. Quality measures can be used to evaluate care across the full range of health care settings—from individual providers, to care teams, to hospitals and hospital systems, to health plans. While some measures easily can be assigned to a specific provider, others are not as straightforward. For example, who gets assigned the cesarean delivery when a midwife turns the case over to an obstetrician?

Timeframe in outcomes measurement. The data infrastructure is currently set up to support measurement of immediate events, 30-day or 90-day episodes, and health insurance plan member years. Longer-term outcomes, such as over 5- and 10- year periods, are out of reach for most measures. To obtain an accurate view of the impact of medical interventions or disease conditions, however, it will be important to follow patients over time. For example, to know the failure rate of intrauterine systems, sterilization, or hormonal contraceptives, it is important to be able to track pregnancy occurrence during use of these methods for longer than 90 days. Failures can occur years after a method is initiated.

Another example is to create a performance measure focused on the overall improvement in quality of life and costs related to different treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding. How does the patient experience vary over time between treatment with hormonal contraception, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy? Which option is most “valuable” over time when the patient experience and the cost are assessed for more than a 90-day episode? These important questions need to be answered as we maneuver into a value-based health system.

Risk adjustment. Quality measures also may need to be risk adjusted. The “My patients are sicker” refrain must be accounted for with full transparency and based on the best available data. Quality measures can be adjusted using an Observed/Expected factor, which helps to account for complicated cases.2

Clearly, social and behavioral determinants of health also play a role in these adjustments, but it can be more challenging to acquire the data elements needed for those types of adjustments. Including these data enables us to evaluate health disparities between populations, both demographically and socioeconomically.3 This is important for future development of minority inclusive quality measures. Some racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer health outcomes from preventable and treatable diseases. Evidence shows that these groups have differences in access to health care, quality of care, and health measures, including life expectancy and maternal mortality. Access to clinical data through quality measures allows for these health disparities to be brought into quantifiable perspective and assists in the development of future incentive programs to combat health inequalities and provide improved delivery of care.

Read about how to develop quality measures

Developing quality measures

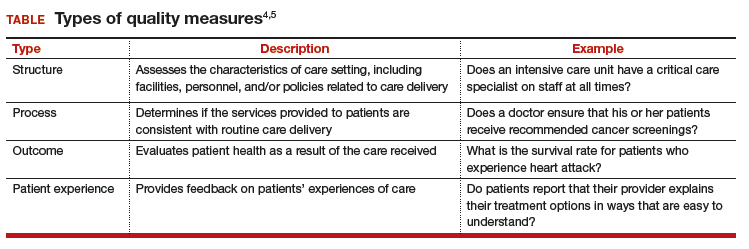

Quality measures generally fall into 4 broad categories: structure, process, outcome, and patient experience (TABLE).4,5 Quality measure development begins with an assessment of the evidence, which is usually derived from clinical guidelines that link a particular process, structure, or outcome with improved patient health or experience of care. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has developed a clinical practice guideline for screening, diagnosing, and managing gestational diabetes. The guideline addresses drug therapies, such as insulin, and alternative treatments, such as nutrition therapy. Much like the process for creating the guideline itself, translating the guideline into a quality measure requires a thoughtful, transparent, and well-defined process.

Role of the quality measure steward. Coordinating the process of translating evidence-based guidelines into quality measures requires a measure steward. Measure stewards usually are government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and/or for-profit companies. During the development process, the steward usually reaches out to additional stakeholders for feedback and consensus. Development process steps include:

- evaluation of the evidence, including the clinical practice guideline(s)

- consensus on the best measurement approach (consider the feasibility of the measurement and how it will be collected)

- development of detailed measure specifications (that is, what will be measured and how)

- feedback on the specifications from stakeholders, including professional societies and patient advocates

- testing of the measure logic and clinical validity against clinical data

- final approval by the measure steward.

Endorsement of quality measures. After a quality measure is developed, it is often endorsed by government agencies, professional societies, and/or consumer groups. Endorsement is a consensus-based process in which stakeholders evaluate a proposed measure based on established standards. Generally, stakeholders include health care professionals, consumers, payers, hospitals, health plans, and government agencies.

Evaluation of quality measures includes these important considerations:

- Are the necessary data fields available in a typical electronic health record (EHR) system?

- What is the data quality for those data fields?

- Can the measure be calculated reliably across different data sets or EHRs?

- Does the measure address one of the National Academy of Medicine quality properties? According to the academy, quality in the context of clinical care can be defined in terms of properties of effectiveness, equity, safety, efficiency, patient centeredness, and timeliness.1

Read about ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

In October 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the final Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Under this rule, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) was created, which was intended to drive “value” rather than “volume” in payment incentives. Measures are critical to defining value-based care. However, the law has limited or no impact on providers who do not care for Medicare patients.

Clinicians eligible to participate in MACRA must bill more than $90,000 a year in Medicare Part B allowed charges and provide care for more than 200 Medicare patients per year.6 This means that the MIPS largely overlooks ObGyns, as the bulk of our patients are insured either by private insurance or by Medicaid. However, maternity care spending is a significant part of both Medicaid and private insurers’ outlay, and both payers are actively considering using value-based financial models that will need to be fed by quality metrics. ACOG wants to be at the forefront of measure development for quality metrics that affect members and has committed resources to formation of a measure development team.

ACOG wants providers to be in control of how their practices are evaluated. For this reason, ACOG is focusing on measures that are based on clinical data entered by providers into an EHR at the point of care. At the same time, ACOG is cognizant of not increasing the documentation burden for providers. Understanding the quality of the data, as opposed to the quality of care, will be a fundamental task for the maternity care registry that ACOG is launching in 2018.

What can ObGyns do?

Quality measures are about more than just money. Public reporting of these measures on government and payer websites may influence public perception of a practice.7 The focus on patient-centered care means that patients have a voice in their care, financially as well as literally, so expect to see increased scrutiny of provider performance by patients as well as payers. One way to measure patient experience of treatments, symptoms, and quality of life is through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Assessing PROMs in routine care ensures that information only the patient can provide is collected and analyzed, thus further enhancing the delivery of care and evaluating how that care is impacting the lives of your patients.

The transition from fee-for-service to a value-based system will not happen overnight, but it will happen. This transition—from being paid for the quantity of documentation to the quality of documentation—will require some change management, rethinking of workflows, and better documentation tools (such as apps instead of EHR customization).

Many in the medical profession are actively exploring these changes and new developments. These changes are too important to leave to administrators, coders, scribes, app developers, and policy makers. Someone in your practice, hospital, or health system is working on these issues today. Tomorrow, you need to be at the table. The voices of practicing ObGyns are critical as we work to address the current challenging environment in which we spend more per capita than any other nation with far inferior results. Measures that matter to us and to our patients will help us provide better and more cost-effective care that payers and patients value.8

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Updated January 2, 2018. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Selecting quality and resource use measures: a decision guide for community quality collaboratives. Part 2. Introduction to measures of quality (continued). https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/perfmeasguide/perfmeaspt2a.html. Reviewed 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Thomas SB, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2050.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Types of quality measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/talkingquality/create/types.html. Reviewed 2011. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. Reviewed November 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Payment-Program/resource-library/QPP-Year-2-Final-Rule-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Published December 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz, A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1531–1541.

- Tooker J. The importance of measuring quality and performance in healthcare. MedGenMed. 2005;7(2):49.

The future of health care is value-based care. If Value equals Quality divided by Cost, then a defined, validated way to measure Quality is paramount to that equation. (Fortunately, Cost comes with convenient measurement units called dollars.) Payers now are asking health care providers to shift from a fee-for-service to a value-based reimbursement structure to encourage providers to deliver the best care at the lowest cost. Providers who can embrace this data-driven paradigm will succeed in this new environment.

So how do we define high-quality care? What makes a good quality measure? How do you actually measure what happens in a clinical encounter that impacts health outcomes?

To answer these questions, organizations have constructed standardized clinical quality measures. Clinical quality measures facilitate value-based care by providing a metric on which to measure a patient’s quality of care. They can be used 1) to decrease the overuse, underuse, and misuse of health care services and 2) to measure patient engagement and satisfaction with care.

What are quality measures?

The Academy of Medicine (formerly named the Institute of Medicine) defines health care quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1

Clearly defined components and terminology. From a quantitative standpoint, quality measures must have a clearly defined numerator and denominator and appropriate inclusions, exclusions, and exceptions. These components need to be expressed clearly in terms of publicly available terminologies, such as ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes or SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms) terms. A measure that asks if “antihypertensive meds” have been given will not nearly be as specific as one that asks if “labetalol IV, or hydralazine IV, or nifedipine SL” has been administered. The decision to tie the data elements in a measure to administrative data, such as ICD codes, or to clinical data, such as SNOMED CT, also affects how these measures can be calculated.

Moving targets. The target of the measure also must carefully be considered. Quality measures can be used to evaluate care across the full range of health care settings—from individual providers, to care teams, to hospitals and hospital systems, to health plans. While some measures easily can be assigned to a specific provider, others are not as straightforward. For example, who gets assigned the cesarean delivery when a midwife turns the case over to an obstetrician?

Timeframe in outcomes measurement. The data infrastructure is currently set up to support measurement of immediate events, 30-day or 90-day episodes, and health insurance plan member years. Longer-term outcomes, such as over 5- and 10- year periods, are out of reach for most measures. To obtain an accurate view of the impact of medical interventions or disease conditions, however, it will be important to follow patients over time. For example, to know the failure rate of intrauterine systems, sterilization, or hormonal contraceptives, it is important to be able to track pregnancy occurrence during use of these methods for longer than 90 days. Failures can occur years after a method is initiated.

Another example is to create a performance measure focused on the overall improvement in quality of life and costs related to different treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding. How does the patient experience vary over time between treatment with hormonal contraception, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy? Which option is most “valuable” over time when the patient experience and the cost are assessed for more than a 90-day episode? These important questions need to be answered as we maneuver into a value-based health system.

Risk adjustment. Quality measures also may need to be risk adjusted. The “My patients are sicker” refrain must be accounted for with full transparency and based on the best available data. Quality measures can be adjusted using an Observed/Expected factor, which helps to account for complicated cases.2

Clearly, social and behavioral determinants of health also play a role in these adjustments, but it can be more challenging to acquire the data elements needed for those types of adjustments. Including these data enables us to evaluate health disparities between populations, both demographically and socioeconomically.3 This is important for future development of minority inclusive quality measures. Some racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer health outcomes from preventable and treatable diseases. Evidence shows that these groups have differences in access to health care, quality of care, and health measures, including life expectancy and maternal mortality. Access to clinical data through quality measures allows for these health disparities to be brought into quantifiable perspective and assists in the development of future incentive programs to combat health inequalities and provide improved delivery of care.

Read about how to develop quality measures

Developing quality measures

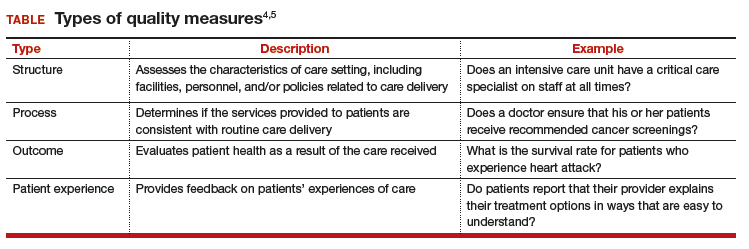

Quality measures generally fall into 4 broad categories: structure, process, outcome, and patient experience (TABLE).4,5 Quality measure development begins with an assessment of the evidence, which is usually derived from clinical guidelines that link a particular process, structure, or outcome with improved patient health or experience of care. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has developed a clinical practice guideline for screening, diagnosing, and managing gestational diabetes. The guideline addresses drug therapies, such as insulin, and alternative treatments, such as nutrition therapy. Much like the process for creating the guideline itself, translating the guideline into a quality measure requires a thoughtful, transparent, and well-defined process.

Role of the quality measure steward. Coordinating the process of translating evidence-based guidelines into quality measures requires a measure steward. Measure stewards usually are government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and/or for-profit companies. During the development process, the steward usually reaches out to additional stakeholders for feedback and consensus. Development process steps include:

- evaluation of the evidence, including the clinical practice guideline(s)

- consensus on the best measurement approach (consider the feasibility of the measurement and how it will be collected)

- development of detailed measure specifications (that is, what will be measured and how)

- feedback on the specifications from stakeholders, including professional societies and patient advocates

- testing of the measure logic and clinical validity against clinical data

- final approval by the measure steward.

Endorsement of quality measures. After a quality measure is developed, it is often endorsed by government agencies, professional societies, and/or consumer groups. Endorsement is a consensus-based process in which stakeholders evaluate a proposed measure based on established standards. Generally, stakeholders include health care professionals, consumers, payers, hospitals, health plans, and government agencies.

Evaluation of quality measures includes these important considerations:

- Are the necessary data fields available in a typical electronic health record (EHR) system?

- What is the data quality for those data fields?

- Can the measure be calculated reliably across different data sets or EHRs?

- Does the measure address one of the National Academy of Medicine quality properties? According to the academy, quality in the context of clinical care can be defined in terms of properties of effectiveness, equity, safety, efficiency, patient centeredness, and timeliness.1

Read about ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

In October 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the final Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Under this rule, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) was created, which was intended to drive “value” rather than “volume” in payment incentives. Measures are critical to defining value-based care. However, the law has limited or no impact on providers who do not care for Medicare patients.

Clinicians eligible to participate in MACRA must bill more than $90,000 a year in Medicare Part B allowed charges and provide care for more than 200 Medicare patients per year.6 This means that the MIPS largely overlooks ObGyns, as the bulk of our patients are insured either by private insurance or by Medicaid. However, maternity care spending is a significant part of both Medicaid and private insurers’ outlay, and both payers are actively considering using value-based financial models that will need to be fed by quality metrics. ACOG wants to be at the forefront of measure development for quality metrics that affect members and has committed resources to formation of a measure development team.

ACOG wants providers to be in control of how their practices are evaluated. For this reason, ACOG is focusing on measures that are based on clinical data entered by providers into an EHR at the point of care. At the same time, ACOG is cognizant of not increasing the documentation burden for providers. Understanding the quality of the data, as opposed to the quality of care, will be a fundamental task for the maternity care registry that ACOG is launching in 2018.

What can ObGyns do?

Quality measures are about more than just money. Public reporting of these measures on government and payer websites may influence public perception of a practice.7 The focus on patient-centered care means that patients have a voice in their care, financially as well as literally, so expect to see increased scrutiny of provider performance by patients as well as payers. One way to measure patient experience of treatments, symptoms, and quality of life is through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Assessing PROMs in routine care ensures that information only the patient can provide is collected and analyzed, thus further enhancing the delivery of care and evaluating how that care is impacting the lives of your patients.

The transition from fee-for-service to a value-based system will not happen overnight, but it will happen. This transition—from being paid for the quantity of documentation to the quality of documentation—will require some change management, rethinking of workflows, and better documentation tools (such as apps instead of EHR customization).

Many in the medical profession are actively exploring these changes and new developments. These changes are too important to leave to administrators, coders, scribes, app developers, and policy makers. Someone in your practice, hospital, or health system is working on these issues today. Tomorrow, you need to be at the table. The voices of practicing ObGyns are critical as we work to address the current challenging environment in which we spend more per capita than any other nation with far inferior results. Measures that matter to us and to our patients will help us provide better and more cost-effective care that payers and patients value.8

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The future of health care is value-based care. If Value equals Quality divided by Cost, then a defined, validated way to measure Quality is paramount to that equation. (Fortunately, Cost comes with convenient measurement units called dollars.) Payers now are asking health care providers to shift from a fee-for-service to a value-based reimbursement structure to encourage providers to deliver the best care at the lowest cost. Providers who can embrace this data-driven paradigm will succeed in this new environment.

So how do we define high-quality care? What makes a good quality measure? How do you actually measure what happens in a clinical encounter that impacts health outcomes?

To answer these questions, organizations have constructed standardized clinical quality measures. Clinical quality measures facilitate value-based care by providing a metric on which to measure a patient’s quality of care. They can be used 1) to decrease the overuse, underuse, and misuse of health care services and 2) to measure patient engagement and satisfaction with care.

What are quality measures?

The Academy of Medicine (formerly named the Institute of Medicine) defines health care quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1

Clearly defined components and terminology. From a quantitative standpoint, quality measures must have a clearly defined numerator and denominator and appropriate inclusions, exclusions, and exceptions. These components need to be expressed clearly in terms of publicly available terminologies, such as ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes or SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms) terms. A measure that asks if “antihypertensive meds” have been given will not nearly be as specific as one that asks if “labetalol IV, or hydralazine IV, or nifedipine SL” has been administered. The decision to tie the data elements in a measure to administrative data, such as ICD codes, or to clinical data, such as SNOMED CT, also affects how these measures can be calculated.

Moving targets. The target of the measure also must carefully be considered. Quality measures can be used to evaluate care across the full range of health care settings—from individual providers, to care teams, to hospitals and hospital systems, to health plans. While some measures easily can be assigned to a specific provider, others are not as straightforward. For example, who gets assigned the cesarean delivery when a midwife turns the case over to an obstetrician?

Timeframe in outcomes measurement. The data infrastructure is currently set up to support measurement of immediate events, 30-day or 90-day episodes, and health insurance plan member years. Longer-term outcomes, such as over 5- and 10- year periods, are out of reach for most measures. To obtain an accurate view of the impact of medical interventions or disease conditions, however, it will be important to follow patients over time. For example, to know the failure rate of intrauterine systems, sterilization, or hormonal contraceptives, it is important to be able to track pregnancy occurrence during use of these methods for longer than 90 days. Failures can occur years after a method is initiated.

Another example is to create a performance measure focused on the overall improvement in quality of life and costs related to different treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding. How does the patient experience vary over time between treatment with hormonal contraception, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy? Which option is most “valuable” over time when the patient experience and the cost are assessed for more than a 90-day episode? These important questions need to be answered as we maneuver into a value-based health system.

Risk adjustment. Quality measures also may need to be risk adjusted. The “My patients are sicker” refrain must be accounted for with full transparency and based on the best available data. Quality measures can be adjusted using an Observed/Expected factor, which helps to account for complicated cases.2

Clearly, social and behavioral determinants of health also play a role in these adjustments, but it can be more challenging to acquire the data elements needed for those types of adjustments. Including these data enables us to evaluate health disparities between populations, both demographically and socioeconomically.3 This is important for future development of minority inclusive quality measures. Some racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer health outcomes from preventable and treatable diseases. Evidence shows that these groups have differences in access to health care, quality of care, and health measures, including life expectancy and maternal mortality. Access to clinical data through quality measures allows for these health disparities to be brought into quantifiable perspective and assists in the development of future incentive programs to combat health inequalities and provide improved delivery of care.

Read about how to develop quality measures

Developing quality measures

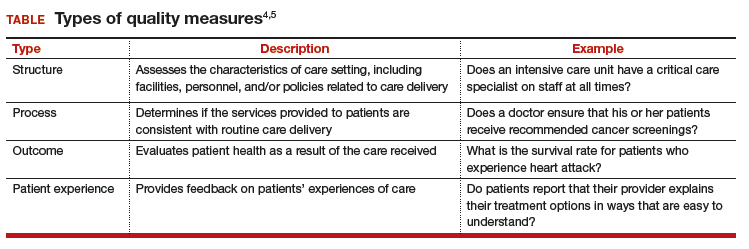

Quality measures generally fall into 4 broad categories: structure, process, outcome, and patient experience (TABLE).4,5 Quality measure development begins with an assessment of the evidence, which is usually derived from clinical guidelines that link a particular process, structure, or outcome with improved patient health or experience of care. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has developed a clinical practice guideline for screening, diagnosing, and managing gestational diabetes. The guideline addresses drug therapies, such as insulin, and alternative treatments, such as nutrition therapy. Much like the process for creating the guideline itself, translating the guideline into a quality measure requires a thoughtful, transparent, and well-defined process.

Role of the quality measure steward. Coordinating the process of translating evidence-based guidelines into quality measures requires a measure steward. Measure stewards usually are government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and/or for-profit companies. During the development process, the steward usually reaches out to additional stakeholders for feedback and consensus. Development process steps include:

- evaluation of the evidence, including the clinical practice guideline(s)

- consensus on the best measurement approach (consider the feasibility of the measurement and how it will be collected)

- development of detailed measure specifications (that is, what will be measured and how)

- feedback on the specifications from stakeholders, including professional societies and patient advocates

- testing of the measure logic and clinical validity against clinical data

- final approval by the measure steward.

Endorsement of quality measures. After a quality measure is developed, it is often endorsed by government agencies, professional societies, and/or consumer groups. Endorsement is a consensus-based process in which stakeholders evaluate a proposed measure based on established standards. Generally, stakeholders include health care professionals, consumers, payers, hospitals, health plans, and government agencies.

Evaluation of quality measures includes these important considerations:

- Are the necessary data fields available in a typical electronic health record (EHR) system?

- What is the data quality for those data fields?

- Can the measure be calculated reliably across different data sets or EHRs?

- Does the measure address one of the National Academy of Medicine quality properties? According to the academy, quality in the context of clinical care can be defined in terms of properties of effectiveness, equity, safety, efficiency, patient centeredness, and timeliness.1

Read about ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

In October 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the final Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Under this rule, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) was created, which was intended to drive “value” rather than “volume” in payment incentives. Measures are critical to defining value-based care. However, the law has limited or no impact on providers who do not care for Medicare patients.

Clinicians eligible to participate in MACRA must bill more than $90,000 a year in Medicare Part B allowed charges and provide care for more than 200 Medicare patients per year.6 This means that the MIPS largely overlooks ObGyns, as the bulk of our patients are insured either by private insurance or by Medicaid. However, maternity care spending is a significant part of both Medicaid and private insurers’ outlay, and both payers are actively considering using value-based financial models that will need to be fed by quality metrics. ACOG wants to be at the forefront of measure development for quality metrics that affect members and has committed resources to formation of a measure development team.

ACOG wants providers to be in control of how their practices are evaluated. For this reason, ACOG is focusing on measures that are based on clinical data entered by providers into an EHR at the point of care. At the same time, ACOG is cognizant of not increasing the documentation burden for providers. Understanding the quality of the data, as opposed to the quality of care, will be a fundamental task for the maternity care registry that ACOG is launching in 2018.

What can ObGyns do?

Quality measures are about more than just money. Public reporting of these measures on government and payer websites may influence public perception of a practice.7 The focus on patient-centered care means that patients have a voice in their care, financially as well as literally, so expect to see increased scrutiny of provider performance by patients as well as payers. One way to measure patient experience of treatments, symptoms, and quality of life is through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Assessing PROMs in routine care ensures that information only the patient can provide is collected and analyzed, thus further enhancing the delivery of care and evaluating how that care is impacting the lives of your patients.

The transition from fee-for-service to a value-based system will not happen overnight, but it will happen. This transition—from being paid for the quantity of documentation to the quality of documentation—will require some change management, rethinking of workflows, and better documentation tools (such as apps instead of EHR customization).

Many in the medical profession are actively exploring these changes and new developments. These changes are too important to leave to administrators, coders, scribes, app developers, and policy makers. Someone in your practice, hospital, or health system is working on these issues today. Tomorrow, you need to be at the table. The voices of practicing ObGyns are critical as we work to address the current challenging environment in which we spend more per capita than any other nation with far inferior results. Measures that matter to us and to our patients will help us provide better and more cost-effective care that payers and patients value.8

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Updated January 2, 2018. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Selecting quality and resource use measures: a decision guide for community quality collaboratives. Part 2. Introduction to measures of quality (continued). https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/perfmeasguide/perfmeaspt2a.html. Reviewed 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Thomas SB, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2050.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Types of quality measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/talkingquality/create/types.html. Reviewed 2011. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. Reviewed November 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Payment-Program/resource-library/QPP-Year-2-Final-Rule-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Published December 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz, A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1531–1541.

- Tooker J. The importance of measuring quality and performance in healthcare. MedGenMed. 2005;7(2):49.

- National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Updated January 2, 2018. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Selecting quality and resource use measures: a decision guide for community quality collaboratives. Part 2. Introduction to measures of quality (continued). https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/perfmeasguide/perfmeaspt2a.html. Reviewed 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Thomas SB, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2050.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Types of quality measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/talkingquality/create/types.html. Reviewed 2011. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. Reviewed November 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Payment-Program/resource-library/QPP-Year-2-Final-Rule-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Published December 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz, A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1531–1541.

- Tooker J. The importance of measuring quality and performance in healthcare. MedGenMed. 2005;7(2):49.

Read all parts of this series

PART 1 Value-based payment: What does it mean and how can ObGyns get out ahead

PART 2 What makes a “quality” quality measure?

PART 3 The role of patient-reported outcomes in women’s health

PART 4 It costs what?! How we can educate residents and students on how much things cost