User login

Surviving the waning days of fee-for-service payments

By now, most gastroenterologists have heard that Medicare and commercial insurers would like to end the traditional method of paying for medical services as they are performed (called "fee-for-service") and make payments contingent on health outcomes of our patients (called "value-based reimbursement"). The AGA has worked diligently to educate members about this new methodology by arguing against payment formulas that are unfair to gastroenterologists and developing tools to help members survive this transition. See "The Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice" at www.gastro.org/practice/roadmap-to-the-future-of-gi. This month, Dr. Spencer Dorn defines, in clear language, each part of Medicare’s value-based payment model. Practices would do well to adapt to this change since it will influence our practice’s financial future.

John I. Allen, M.D., MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

In 2010, a White House Commission reported that "federal health care spending represents our single largest fiscal challenge over the long-run."1 Cost growth has since slowed to the lowest rate in decades,2 yet attempts to rein in costs continue to intensify. Central to this effort is reforming how physicians are paid. Although novel payment models – particularly bundled payments and accountable care organizations – have received the bulk of the attention, over the short term, changes to the fee-for-service (FFS) system will have a far greater effect on most gastroenterologists.3

Fee for service

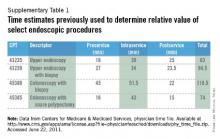

Most physicians are paid under the FFS model, which pays for discrete services rendered. Since 1992 these payments have been linked to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which assigns each service a certain number of relative value units (RVUs), based on geographically adjusted estimates of the work (time and intensity), practice expenses, and malpractice insurance costs associated with providing the service. Critics contend that the fee schedule is distorted and inappropriately favors recently developed procedures over evaluation and management services. In response to these concerns, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has begun to adjust the fee schedule, largely to the detriment of procedural-based specialists such as gastroenterologists.3 For instance, in 2010, CMS eliminated payments for specialist consultations and increased fees for nonconsultative office visits. More recently, the Affordable Care Act included a 10% bonus for primary care evaluation and management services, and directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a formal process to review potentially misvalued codes, including upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasound. Two organizations contracted by CMS currently are studying the times required to perform these procedures. Because time estimates currently used to determine work requirements for these procedures (Supplementary Table 1) are likely shorter than real-world time requirements, Medicare reimbursement for these procedures almost certainly will decrease. With nearly two-thirds of gastrointestinal (GI) practice revenue derived from procedures (particularly colonoscopy), the effects may be severe.4

The fee schedule tells only half the story. Once established, RVUs are multiplied by a conversion factor (CF) to derive the actual dollar payment amount for a given service. This CF is determined through the controversial sustainable growth rate (SGR) mechanism, which was implemented in 1992 to reduce growth in Medicare physician expenditures. The SGR compares actual spending with a target benchmark that is based primarily on growth in the overall economy, as well as estimates of medical inflation, and increases in the number of Medicare beneficiaries.5 If actual spending is less than targeted spending the CF is adjusted upward. Conversely, if actual spending exceeds targeted spending, the CF is adjusted downward and payments are cut, unless Congress intervenes, as it has done each year since 2003, most recently on March 31, 2014, with a doc fix that averted a 30% fee reduction.

No one likes the SGR, especially the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which called it a "fundamentally flawed" mechanism that paradoxically has exacerbated – rather than constrained – cost and volume growth. The challenge is that replacing the SGR will cost between $130 billion and $300 billion. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recommends funding this by freezing current primary care payments, and cutting specialist payments (including gastroenterologists) by 5.9% annually for 3 years and then freezing them for 7 years. In the long term, any grand compromise to fix the SGR may push providers away from FFS to newer payment models, such as bundled payment and shared savings models.6 In the meantime, Medicare, Medicaid, and many private payers have created a series of programs to encourage greater value from the FFS system. We discuss the most noteworthy federal programs later.

Physician Quality Reporting System

Pay-for-performance programs use financial incentives to encourage providers to increase quality or decrease costs.7 Leading the way is Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), through which gastroenterologists can use claims data, electronic health record data, or a qualified registry (American Gastroenterological Association Digestive Health Recognition Program or the American College of Gastroenterology GI Quality Improvement Consortium Registry) to report performance on either three or more individual PQRS measures or one PQRS measures group (collection of related individual measures).8 The number of quality measures, the number of patients on which to report, and the reporting time period vary depending on the reporting mechanism (claims, electronic health record, or registry) and whether reporting is at the individual physician or group level.9 There are individual, gastroenterology-specific measures for screening and surveillance colonoscopy (PQRS Measure 320: appropriate follow-up recommendation after normal colonoscopy in average-risk patients; measure 185: appropriate surveillance interval for patients with a history of adenomatous polyps) and diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C viral infection (measures 83-90). Gastroenterologists also may report on individual measures related to preventive care and screening (measure 128: body mass index screening; measure 226: tobacco screening and cessation intervention) and participation in a quality registry (measure 321). Finally, there is a gastroenterology-specific measures group for inflammatory bowel disease (8 related measures). In 2011, there were 2037 gastroenterologists (26.1% of those eligible) who received $3.5 million in PQRS incentives (median, $1290 per provider; range, $1-$12,950).8 Physicians who participate in PQRS in 2013 and 2014 will receive a 0.5% bonus on Medicare fees (with an additional 0.5% bonus available to those who also successfully complete a Maintenance of Certification program). Starting in 2015, those who do not satisfactorily participate will face a 1.5% penalty, and in 2016 and beyond a 2% penalty.10

Value-based payment modifier

The Affordable Care Act directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services to implement a budget-neutral value-based payment modifier by 2015. Initially, this modifier will be used to adjust payments made to a select number of large (100-plus providers) practices. Among those practices, those that did not satisfy PQRS requirements 2 years earlier (2013) will suffer 1% cuts to all Medicare payments. Those that satisfied 2013 PQRS will be granted the option of having payment adjusted based on quality and cost.11 By 2017, this payment modifier will be applied to all Medicare physician payments. Higher-value providers will receive across-the-board Medicare bonuses, whereas lower-value providers will be penalized. As part of this program, CMS will provide the practice with Quality Resource and Use Reports that compare the practices’ quality and cost with other similar practices. It is likely that some of the information included in these reports will be made public on the Physician Compare website.

Public reporting: Physician Compare

Still under development, the CMS Physician Compare website currently includes the physician name, specialty, location, medical school, hospital affiliation, and whether they are accepting new Medicare patients. Soon it also will display whether the physician participated in the e-prescribing program and PQRS, and eventually it will report physician performance on certain quality measures. By publicizing performance data CMS hopes to help steer Medicare beneficiaries to higher-value providers. If information alone is not enough, CMS plans to study the effect of providing beneficiaries with financial incentives to use high-quality physicians.12

Meaningful use

The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act authorized the Department of Health & Human Services to establish programs to promote the use of electronic health records. Under this program, eligible providers who meaningfully use certified electronic health records qualify for Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments. Through a series of regulations, CMS since has outlined an evolving, three-stage set of criteria for defining meaningful use. Stage 1 requirements mainly revolve around electronic data capture, with providers required to electronically record key parts of a patient’s history (demographics, vitals, active medications, problem lists, and smoking status), electronically prescribe medications, provide patients with care summary documents, implement at least one decision support tool, and report clinical quality. Stage 2, which starts as early as 2014 for some providers, will include more stringent requirements to improve quality (with clinical quality measures that align with other reporting programs, including PQRS), engage patients, and use clinical decision supports.13 Stage 3, which will start as early as 2017, likely will require providers to measure and improve clinical outcomes, use even more robust clinical decision supports, support patient self-management, and share clinical data through health information exchanges.14 Eligible providers who achieve meaningful use criteria will receive incentive payments for up to 5 years, totaling as much as $44,000 (under Medicare) or $63,750 (under Medicaid). Meanwhile, providers who do not meet meaningful use by 2015 will face a 1% reduction in Medicare payments, which, by 2018, will reach 5%.

Electronic prescribing

Similar to the meaningful use program is a separate initiative to spur electronic prescribing. Physicians who use qualified e-prescription systems to prescribe for at least 10% of Medicare encounters are entitled to a 0.5% bonus in 2013 (although not if they also receive meaningful use bonuses). Meanwhile, penalties (1.5% in 2013 and 2% in 2014) will be levied on those who do not e-prescribe (Table 1). The program ends after 2014.

Conclusions

FFS has been criticized for encouraging quantity over quality, favoring procedures over cognitive services, and fragmenting care.15 The federal government has responded by revaluing the number of RVUs assigned to certain services, and with programs that adjust FFS payments based on the quality and cost of care. Each program starts as voluntary but ultimately becomes mandatory. Under the National Quality Strategy, CMS has begun to align these programs to increase participation and reduce provider burden. For example, PQRS includes all Meaningful Use Clinical Quality Measures, and serves as the basis for the Physician Compare website and the value-based payment modifier.16 The latter may be a way of one day rolling all these programs into the same pot.

Gastroenterologists have long profited from a relatively unbridled FFS system. For most practices, changes to FFS will be quite challenging. However, gastroenterologists who remain in practice cannot ignore this new reality. Potential bonuses and penalties that, at first blush, seem relatively small, will add up quickly (Table 1). In addition, these programs almost certainly will extend beyond Medicare. For example, we expect private payers to use Physician Compare data to create tiered networks. Moving forward, gastroenterologists must measure, report, and improve the quality of their care; nonreporting automatically will be equated with low performance. Meanwhile, GI societies must continue to develop new quality measures that extend beyond colorectal cancer screening, viral hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease to cover other aspects of care. New payment models on the horizon (including bundled payments and shared savings models) will create even tighter linkages between payment and performance measurement.

Acknowledgment

The author appreciates the many insights shared by John Allen, Robert Berenson, Laura Clote, Lawrence Kosinski, Kathleen Teixeira, and Elizabeth Wolf.

References

1. The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. The moment of truth. 2010. www.fiscalcommission.gov/sites/fiscalcommission.gov/files/documents/TheMomentofTruth12_1_2010.pdf. Accessed Jan. 3, 2011.

2. Health spending growth near 4 percent for fourth year; price growth at 14-year low. Available at: http://altarum.org/about/news-and-events/health-spending-growth-near-4-percent-for-fourth-year-price-growth-at-14-year-low. Accessed Feb. 10, 2013.

3. Ginsburg P.B. Fee-for-service will remain a feature of major payment reforms, requiring more changes in Medicare physician payment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1977-83.

4. Littenberg G. Where will health care reform take GI practice?. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:396-401e1–2.

5. Congressional Budget Office. The sustainable growth rate formula for setting Medicare’s physician payment rates. Sept. 6, 2006. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/75xx/doc7542/09-07-sgr-brief.pdf. Accessed Feb. 1, 2009.

6. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. 2012. Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar12_EntireReport.pdf. Accessed Feb. 1, 2013.

7. 2010 National P4P Survey. Executive summary. 2010. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/ims/Global/Content/Solutions/Healthcare%20Analytics%20and%20Services/Payer%20Solutions/Survey_Exec_Sum.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System. 2013. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/index.html?redirect=/pqrs. Accessed March 29, 2013.

9. CMS 2012 Physician quality reporting: participation decision tree. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/downloads/2012_PhysQualRptg_DecisionTree11-11-2011.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

10. The Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). 2013. Available at: http://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/cms-physician-qualitative-report-initiative. Accessed March 29, 2013.

11. CMS Proposals for the physician value-based payment modifier under the Medicare physician fee schedule. 2012. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/NPC/Downloads/8-1-12-VBPM-NPC-Presentation.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

12. Physician compare redesign and public reporting webinar. 2013. Available at: http://ebookbrowsee.net/physician-compare-webinar-background-paper-508-compliant-pdf-d440592152. Accessed March 29, 2013.

13. What is meaningful use? Available at: http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/meaningful-use. Accessed March 29, 2013.

14. Marcotte L., Seidman J., Trudel K., et al. Achieving meaningful use of health information technology: a guide for physicians to the EHR incentive programs. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:731-6.

15. Miller H.D. Creating payment systems to accelerate value-driven health care: issues and options for policy reform. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund, 2007.

16. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS physician programs and alignment to date, 2012. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cqi/pcpi-032912-rapp.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

Dr. Dorn, MPH, MHA, is assistant professor of medicine and vice chief of gastroenterology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Center for Functional GI Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Content from this column was originally published in the "Practice Management: The Road Ahead" section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2013;11:1212-5).

"Practice Management Toolbox" provides key information and resources necessary for facing the unique challenges of today’s clinical practices.

Resources for Practical Application: To view additional online resources about this topic and to access our Coding Corner, visit http://www.cghjournal.org/content/practice_management.

By now, most gastroenterologists have heard that Medicare and commercial insurers would like to end the traditional method of paying for medical services as they are performed (called "fee-for-service") and make payments contingent on health outcomes of our patients (called "value-based reimbursement"). The AGA has worked diligently to educate members about this new methodology by arguing against payment formulas that are unfair to gastroenterologists and developing tools to help members survive this transition. See "The Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice" at www.gastro.org/practice/roadmap-to-the-future-of-gi. This month, Dr. Spencer Dorn defines, in clear language, each part of Medicare’s value-based payment model. Practices would do well to adapt to this change since it will influence our practice’s financial future.

John I. Allen, M.D., MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

In 2010, a White House Commission reported that "federal health care spending represents our single largest fiscal challenge over the long-run."1 Cost growth has since slowed to the lowest rate in decades,2 yet attempts to rein in costs continue to intensify. Central to this effort is reforming how physicians are paid. Although novel payment models – particularly bundled payments and accountable care organizations – have received the bulk of the attention, over the short term, changes to the fee-for-service (FFS) system will have a far greater effect on most gastroenterologists.3

Fee for service

Most physicians are paid under the FFS model, which pays for discrete services rendered. Since 1992 these payments have been linked to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which assigns each service a certain number of relative value units (RVUs), based on geographically adjusted estimates of the work (time and intensity), practice expenses, and malpractice insurance costs associated with providing the service. Critics contend that the fee schedule is distorted and inappropriately favors recently developed procedures over evaluation and management services. In response to these concerns, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has begun to adjust the fee schedule, largely to the detriment of procedural-based specialists such as gastroenterologists.3 For instance, in 2010, CMS eliminated payments for specialist consultations and increased fees for nonconsultative office visits. More recently, the Affordable Care Act included a 10% bonus for primary care evaluation and management services, and directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a formal process to review potentially misvalued codes, including upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasound. Two organizations contracted by CMS currently are studying the times required to perform these procedures. Because time estimates currently used to determine work requirements for these procedures (Supplementary Table 1) are likely shorter than real-world time requirements, Medicare reimbursement for these procedures almost certainly will decrease. With nearly two-thirds of gastrointestinal (GI) practice revenue derived from procedures (particularly colonoscopy), the effects may be severe.4

The fee schedule tells only half the story. Once established, RVUs are multiplied by a conversion factor (CF) to derive the actual dollar payment amount for a given service. This CF is determined through the controversial sustainable growth rate (SGR) mechanism, which was implemented in 1992 to reduce growth in Medicare physician expenditures. The SGR compares actual spending with a target benchmark that is based primarily on growth in the overall economy, as well as estimates of medical inflation, and increases in the number of Medicare beneficiaries.5 If actual spending is less than targeted spending the CF is adjusted upward. Conversely, if actual spending exceeds targeted spending, the CF is adjusted downward and payments are cut, unless Congress intervenes, as it has done each year since 2003, most recently on March 31, 2014, with a doc fix that averted a 30% fee reduction.

No one likes the SGR, especially the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which called it a "fundamentally flawed" mechanism that paradoxically has exacerbated – rather than constrained – cost and volume growth. The challenge is that replacing the SGR will cost between $130 billion and $300 billion. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recommends funding this by freezing current primary care payments, and cutting specialist payments (including gastroenterologists) by 5.9% annually for 3 years and then freezing them for 7 years. In the long term, any grand compromise to fix the SGR may push providers away from FFS to newer payment models, such as bundled payment and shared savings models.6 In the meantime, Medicare, Medicaid, and many private payers have created a series of programs to encourage greater value from the FFS system. We discuss the most noteworthy federal programs later.

Physician Quality Reporting System

Pay-for-performance programs use financial incentives to encourage providers to increase quality or decrease costs.7 Leading the way is Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), through which gastroenterologists can use claims data, electronic health record data, or a qualified registry (American Gastroenterological Association Digestive Health Recognition Program or the American College of Gastroenterology GI Quality Improvement Consortium Registry) to report performance on either three or more individual PQRS measures or one PQRS measures group (collection of related individual measures).8 The number of quality measures, the number of patients on which to report, and the reporting time period vary depending on the reporting mechanism (claims, electronic health record, or registry) and whether reporting is at the individual physician or group level.9 There are individual, gastroenterology-specific measures for screening and surveillance colonoscopy (PQRS Measure 320: appropriate follow-up recommendation after normal colonoscopy in average-risk patients; measure 185: appropriate surveillance interval for patients with a history of adenomatous polyps) and diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C viral infection (measures 83-90). Gastroenterologists also may report on individual measures related to preventive care and screening (measure 128: body mass index screening; measure 226: tobacco screening and cessation intervention) and participation in a quality registry (measure 321). Finally, there is a gastroenterology-specific measures group for inflammatory bowel disease (8 related measures). In 2011, there were 2037 gastroenterologists (26.1% of those eligible) who received $3.5 million in PQRS incentives (median, $1290 per provider; range, $1-$12,950).8 Physicians who participate in PQRS in 2013 and 2014 will receive a 0.5% bonus on Medicare fees (with an additional 0.5% bonus available to those who also successfully complete a Maintenance of Certification program). Starting in 2015, those who do not satisfactorily participate will face a 1.5% penalty, and in 2016 and beyond a 2% penalty.10

Value-based payment modifier

The Affordable Care Act directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services to implement a budget-neutral value-based payment modifier by 2015. Initially, this modifier will be used to adjust payments made to a select number of large (100-plus providers) practices. Among those practices, those that did not satisfy PQRS requirements 2 years earlier (2013) will suffer 1% cuts to all Medicare payments. Those that satisfied 2013 PQRS will be granted the option of having payment adjusted based on quality and cost.11 By 2017, this payment modifier will be applied to all Medicare physician payments. Higher-value providers will receive across-the-board Medicare bonuses, whereas lower-value providers will be penalized. As part of this program, CMS will provide the practice with Quality Resource and Use Reports that compare the practices’ quality and cost with other similar practices. It is likely that some of the information included in these reports will be made public on the Physician Compare website.

Public reporting: Physician Compare

Still under development, the CMS Physician Compare website currently includes the physician name, specialty, location, medical school, hospital affiliation, and whether they are accepting new Medicare patients. Soon it also will display whether the physician participated in the e-prescribing program and PQRS, and eventually it will report physician performance on certain quality measures. By publicizing performance data CMS hopes to help steer Medicare beneficiaries to higher-value providers. If information alone is not enough, CMS plans to study the effect of providing beneficiaries with financial incentives to use high-quality physicians.12

Meaningful use

The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act authorized the Department of Health & Human Services to establish programs to promote the use of electronic health records. Under this program, eligible providers who meaningfully use certified electronic health records qualify for Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments. Through a series of regulations, CMS since has outlined an evolving, three-stage set of criteria for defining meaningful use. Stage 1 requirements mainly revolve around electronic data capture, with providers required to electronically record key parts of a patient’s history (demographics, vitals, active medications, problem lists, and smoking status), electronically prescribe medications, provide patients with care summary documents, implement at least one decision support tool, and report clinical quality. Stage 2, which starts as early as 2014 for some providers, will include more stringent requirements to improve quality (with clinical quality measures that align with other reporting programs, including PQRS), engage patients, and use clinical decision supports.13 Stage 3, which will start as early as 2017, likely will require providers to measure and improve clinical outcomes, use even more robust clinical decision supports, support patient self-management, and share clinical data through health information exchanges.14 Eligible providers who achieve meaningful use criteria will receive incentive payments for up to 5 years, totaling as much as $44,000 (under Medicare) or $63,750 (under Medicaid). Meanwhile, providers who do not meet meaningful use by 2015 will face a 1% reduction in Medicare payments, which, by 2018, will reach 5%.

Electronic prescribing

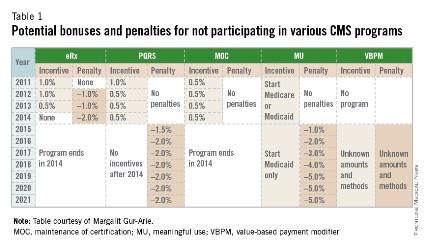

Similar to the meaningful use program is a separate initiative to spur electronic prescribing. Physicians who use qualified e-prescription systems to prescribe for at least 10% of Medicare encounters are entitled to a 0.5% bonus in 2013 (although not if they also receive meaningful use bonuses). Meanwhile, penalties (1.5% in 2013 and 2% in 2014) will be levied on those who do not e-prescribe (Table 1). The program ends after 2014.

Conclusions

FFS has been criticized for encouraging quantity over quality, favoring procedures over cognitive services, and fragmenting care.15 The federal government has responded by revaluing the number of RVUs assigned to certain services, and with programs that adjust FFS payments based on the quality and cost of care. Each program starts as voluntary but ultimately becomes mandatory. Under the National Quality Strategy, CMS has begun to align these programs to increase participation and reduce provider burden. For example, PQRS includes all Meaningful Use Clinical Quality Measures, and serves as the basis for the Physician Compare website and the value-based payment modifier.16 The latter may be a way of one day rolling all these programs into the same pot.

Gastroenterologists have long profited from a relatively unbridled FFS system. For most practices, changes to FFS will be quite challenging. However, gastroenterologists who remain in practice cannot ignore this new reality. Potential bonuses and penalties that, at first blush, seem relatively small, will add up quickly (Table 1). In addition, these programs almost certainly will extend beyond Medicare. For example, we expect private payers to use Physician Compare data to create tiered networks. Moving forward, gastroenterologists must measure, report, and improve the quality of their care; nonreporting automatically will be equated with low performance. Meanwhile, GI societies must continue to develop new quality measures that extend beyond colorectal cancer screening, viral hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease to cover other aspects of care. New payment models on the horizon (including bundled payments and shared savings models) will create even tighter linkages between payment and performance measurement.

Acknowledgment

The author appreciates the many insights shared by John Allen, Robert Berenson, Laura Clote, Lawrence Kosinski, Kathleen Teixeira, and Elizabeth Wolf.

References

1. The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. The moment of truth. 2010. www.fiscalcommission.gov/sites/fiscalcommission.gov/files/documents/TheMomentofTruth12_1_2010.pdf. Accessed Jan. 3, 2011.

2. Health spending growth near 4 percent for fourth year; price growth at 14-year low. Available at: http://altarum.org/about/news-and-events/health-spending-growth-near-4-percent-for-fourth-year-price-growth-at-14-year-low. Accessed Feb. 10, 2013.

3. Ginsburg P.B. Fee-for-service will remain a feature of major payment reforms, requiring more changes in Medicare physician payment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1977-83.

4. Littenberg G. Where will health care reform take GI practice?. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:396-401e1–2.

5. Congressional Budget Office. The sustainable growth rate formula for setting Medicare’s physician payment rates. Sept. 6, 2006. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/75xx/doc7542/09-07-sgr-brief.pdf. Accessed Feb. 1, 2009.

6. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. 2012. Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar12_EntireReport.pdf. Accessed Feb. 1, 2013.

7. 2010 National P4P Survey. Executive summary. 2010. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/ims/Global/Content/Solutions/Healthcare%20Analytics%20and%20Services/Payer%20Solutions/Survey_Exec_Sum.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System. 2013. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/index.html?redirect=/pqrs. Accessed March 29, 2013.

9. CMS 2012 Physician quality reporting: participation decision tree. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/downloads/2012_PhysQualRptg_DecisionTree11-11-2011.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

10. The Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). 2013. Available at: http://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/cms-physician-qualitative-report-initiative. Accessed March 29, 2013.

11. CMS Proposals for the physician value-based payment modifier under the Medicare physician fee schedule. 2012. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/NPC/Downloads/8-1-12-VBPM-NPC-Presentation.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

12. Physician compare redesign and public reporting webinar. 2013. Available at: http://ebookbrowsee.net/physician-compare-webinar-background-paper-508-compliant-pdf-d440592152. Accessed March 29, 2013.

13. What is meaningful use? Available at: http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/meaningful-use. Accessed March 29, 2013.

14. Marcotte L., Seidman J., Trudel K., et al. Achieving meaningful use of health information technology: a guide for physicians to the EHR incentive programs. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:731-6.

15. Miller H.D. Creating payment systems to accelerate value-driven health care: issues and options for policy reform. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund, 2007.

16. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS physician programs and alignment to date, 2012. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cqi/pcpi-032912-rapp.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

Dr. Dorn, MPH, MHA, is assistant professor of medicine and vice chief of gastroenterology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Center for Functional GI Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Content from this column was originally published in the "Practice Management: The Road Ahead" section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2013;11:1212-5).

"Practice Management Toolbox" provides key information and resources necessary for facing the unique challenges of today’s clinical practices.

Resources for Practical Application: To view additional online resources about this topic and to access our Coding Corner, visit http://www.cghjournal.org/content/practice_management.

By now, most gastroenterologists have heard that Medicare and commercial insurers would like to end the traditional method of paying for medical services as they are performed (called "fee-for-service") and make payments contingent on health outcomes of our patients (called "value-based reimbursement"). The AGA has worked diligently to educate members about this new methodology by arguing against payment formulas that are unfair to gastroenterologists and developing tools to help members survive this transition. See "The Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice" at www.gastro.org/practice/roadmap-to-the-future-of-gi. This month, Dr. Spencer Dorn defines, in clear language, each part of Medicare’s value-based payment model. Practices would do well to adapt to this change since it will influence our practice’s financial future.

John I. Allen, M.D., MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

In 2010, a White House Commission reported that "federal health care spending represents our single largest fiscal challenge over the long-run."1 Cost growth has since slowed to the lowest rate in decades,2 yet attempts to rein in costs continue to intensify. Central to this effort is reforming how physicians are paid. Although novel payment models – particularly bundled payments and accountable care organizations – have received the bulk of the attention, over the short term, changes to the fee-for-service (FFS) system will have a far greater effect on most gastroenterologists.3

Fee for service

Most physicians are paid under the FFS model, which pays for discrete services rendered. Since 1992 these payments have been linked to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which assigns each service a certain number of relative value units (RVUs), based on geographically adjusted estimates of the work (time and intensity), practice expenses, and malpractice insurance costs associated with providing the service. Critics contend that the fee schedule is distorted and inappropriately favors recently developed procedures over evaluation and management services. In response to these concerns, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has begun to adjust the fee schedule, largely to the detriment of procedural-based specialists such as gastroenterologists.3 For instance, in 2010, CMS eliminated payments for specialist consultations and increased fees for nonconsultative office visits. More recently, the Affordable Care Act included a 10% bonus for primary care evaluation and management services, and directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a formal process to review potentially misvalued codes, including upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasound. Two organizations contracted by CMS currently are studying the times required to perform these procedures. Because time estimates currently used to determine work requirements for these procedures (Supplementary Table 1) are likely shorter than real-world time requirements, Medicare reimbursement for these procedures almost certainly will decrease. With nearly two-thirds of gastrointestinal (GI) practice revenue derived from procedures (particularly colonoscopy), the effects may be severe.4

The fee schedule tells only half the story. Once established, RVUs are multiplied by a conversion factor (CF) to derive the actual dollar payment amount for a given service. This CF is determined through the controversial sustainable growth rate (SGR) mechanism, which was implemented in 1992 to reduce growth in Medicare physician expenditures. The SGR compares actual spending with a target benchmark that is based primarily on growth in the overall economy, as well as estimates of medical inflation, and increases in the number of Medicare beneficiaries.5 If actual spending is less than targeted spending the CF is adjusted upward. Conversely, if actual spending exceeds targeted spending, the CF is adjusted downward and payments are cut, unless Congress intervenes, as it has done each year since 2003, most recently on March 31, 2014, with a doc fix that averted a 30% fee reduction.

No one likes the SGR, especially the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which called it a "fundamentally flawed" mechanism that paradoxically has exacerbated – rather than constrained – cost and volume growth. The challenge is that replacing the SGR will cost between $130 billion and $300 billion. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recommends funding this by freezing current primary care payments, and cutting specialist payments (including gastroenterologists) by 5.9% annually for 3 years and then freezing them for 7 years. In the long term, any grand compromise to fix the SGR may push providers away from FFS to newer payment models, such as bundled payment and shared savings models.6 In the meantime, Medicare, Medicaid, and many private payers have created a series of programs to encourage greater value from the FFS system. We discuss the most noteworthy federal programs later.

Physician Quality Reporting System

Pay-for-performance programs use financial incentives to encourage providers to increase quality or decrease costs.7 Leading the way is Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), through which gastroenterologists can use claims data, electronic health record data, or a qualified registry (American Gastroenterological Association Digestive Health Recognition Program or the American College of Gastroenterology GI Quality Improvement Consortium Registry) to report performance on either three or more individual PQRS measures or one PQRS measures group (collection of related individual measures).8 The number of quality measures, the number of patients on which to report, and the reporting time period vary depending on the reporting mechanism (claims, electronic health record, or registry) and whether reporting is at the individual physician or group level.9 There are individual, gastroenterology-specific measures for screening and surveillance colonoscopy (PQRS Measure 320: appropriate follow-up recommendation after normal colonoscopy in average-risk patients; measure 185: appropriate surveillance interval for patients with a history of adenomatous polyps) and diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C viral infection (measures 83-90). Gastroenterologists also may report on individual measures related to preventive care and screening (measure 128: body mass index screening; measure 226: tobacco screening and cessation intervention) and participation in a quality registry (measure 321). Finally, there is a gastroenterology-specific measures group for inflammatory bowel disease (8 related measures). In 2011, there were 2037 gastroenterologists (26.1% of those eligible) who received $3.5 million in PQRS incentives (median, $1290 per provider; range, $1-$12,950).8 Physicians who participate in PQRS in 2013 and 2014 will receive a 0.5% bonus on Medicare fees (with an additional 0.5% bonus available to those who also successfully complete a Maintenance of Certification program). Starting in 2015, those who do not satisfactorily participate will face a 1.5% penalty, and in 2016 and beyond a 2% penalty.10

Value-based payment modifier

The Affordable Care Act directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services to implement a budget-neutral value-based payment modifier by 2015. Initially, this modifier will be used to adjust payments made to a select number of large (100-plus providers) practices. Among those practices, those that did not satisfy PQRS requirements 2 years earlier (2013) will suffer 1% cuts to all Medicare payments. Those that satisfied 2013 PQRS will be granted the option of having payment adjusted based on quality and cost.11 By 2017, this payment modifier will be applied to all Medicare physician payments. Higher-value providers will receive across-the-board Medicare bonuses, whereas lower-value providers will be penalized. As part of this program, CMS will provide the practice with Quality Resource and Use Reports that compare the practices’ quality and cost with other similar practices. It is likely that some of the information included in these reports will be made public on the Physician Compare website.

Public reporting: Physician Compare

Still under development, the CMS Physician Compare website currently includes the physician name, specialty, location, medical school, hospital affiliation, and whether they are accepting new Medicare patients. Soon it also will display whether the physician participated in the e-prescribing program and PQRS, and eventually it will report physician performance on certain quality measures. By publicizing performance data CMS hopes to help steer Medicare beneficiaries to higher-value providers. If information alone is not enough, CMS plans to study the effect of providing beneficiaries with financial incentives to use high-quality physicians.12

Meaningful use

The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act authorized the Department of Health & Human Services to establish programs to promote the use of electronic health records. Under this program, eligible providers who meaningfully use certified electronic health records qualify for Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments. Through a series of regulations, CMS since has outlined an evolving, three-stage set of criteria for defining meaningful use. Stage 1 requirements mainly revolve around electronic data capture, with providers required to electronically record key parts of a patient’s history (demographics, vitals, active medications, problem lists, and smoking status), electronically prescribe medications, provide patients with care summary documents, implement at least one decision support tool, and report clinical quality. Stage 2, which starts as early as 2014 for some providers, will include more stringent requirements to improve quality (with clinical quality measures that align with other reporting programs, including PQRS), engage patients, and use clinical decision supports.13 Stage 3, which will start as early as 2017, likely will require providers to measure and improve clinical outcomes, use even more robust clinical decision supports, support patient self-management, and share clinical data through health information exchanges.14 Eligible providers who achieve meaningful use criteria will receive incentive payments for up to 5 years, totaling as much as $44,000 (under Medicare) or $63,750 (under Medicaid). Meanwhile, providers who do not meet meaningful use by 2015 will face a 1% reduction in Medicare payments, which, by 2018, will reach 5%.

Electronic prescribing

Similar to the meaningful use program is a separate initiative to spur electronic prescribing. Physicians who use qualified e-prescription systems to prescribe for at least 10% of Medicare encounters are entitled to a 0.5% bonus in 2013 (although not if they also receive meaningful use bonuses). Meanwhile, penalties (1.5% in 2013 and 2% in 2014) will be levied on those who do not e-prescribe (Table 1). The program ends after 2014.

Conclusions

FFS has been criticized for encouraging quantity over quality, favoring procedures over cognitive services, and fragmenting care.15 The federal government has responded by revaluing the number of RVUs assigned to certain services, and with programs that adjust FFS payments based on the quality and cost of care. Each program starts as voluntary but ultimately becomes mandatory. Under the National Quality Strategy, CMS has begun to align these programs to increase participation and reduce provider burden. For example, PQRS includes all Meaningful Use Clinical Quality Measures, and serves as the basis for the Physician Compare website and the value-based payment modifier.16 The latter may be a way of one day rolling all these programs into the same pot.

Gastroenterologists have long profited from a relatively unbridled FFS system. For most practices, changes to FFS will be quite challenging. However, gastroenterologists who remain in practice cannot ignore this new reality. Potential bonuses and penalties that, at first blush, seem relatively small, will add up quickly (Table 1). In addition, these programs almost certainly will extend beyond Medicare. For example, we expect private payers to use Physician Compare data to create tiered networks. Moving forward, gastroenterologists must measure, report, and improve the quality of their care; nonreporting automatically will be equated with low performance. Meanwhile, GI societies must continue to develop new quality measures that extend beyond colorectal cancer screening, viral hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease to cover other aspects of care. New payment models on the horizon (including bundled payments and shared savings models) will create even tighter linkages between payment and performance measurement.

Acknowledgment

The author appreciates the many insights shared by John Allen, Robert Berenson, Laura Clote, Lawrence Kosinski, Kathleen Teixeira, and Elizabeth Wolf.

References

1. The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. The moment of truth. 2010. www.fiscalcommission.gov/sites/fiscalcommission.gov/files/documents/TheMomentofTruth12_1_2010.pdf. Accessed Jan. 3, 2011.

2. Health spending growth near 4 percent for fourth year; price growth at 14-year low. Available at: http://altarum.org/about/news-and-events/health-spending-growth-near-4-percent-for-fourth-year-price-growth-at-14-year-low. Accessed Feb. 10, 2013.

3. Ginsburg P.B. Fee-for-service will remain a feature of major payment reforms, requiring more changes in Medicare physician payment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1977-83.

4. Littenberg G. Where will health care reform take GI practice?. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:396-401e1–2.

5. Congressional Budget Office. The sustainable growth rate formula for setting Medicare’s physician payment rates. Sept. 6, 2006. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/75xx/doc7542/09-07-sgr-brief.pdf. Accessed Feb. 1, 2009.

6. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. 2012. Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar12_EntireReport.pdf. Accessed Feb. 1, 2013.

7. 2010 National P4P Survey. Executive summary. 2010. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/ims/Global/Content/Solutions/Healthcare%20Analytics%20and%20Services/Payer%20Solutions/Survey_Exec_Sum.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System. 2013. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/index.html?redirect=/pqrs. Accessed March 29, 2013.

9. CMS 2012 Physician quality reporting: participation decision tree. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/downloads/2012_PhysQualRptg_DecisionTree11-11-2011.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

10. The Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). 2013. Available at: http://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/cms-physician-qualitative-report-initiative. Accessed March 29, 2013.

11. CMS Proposals for the physician value-based payment modifier under the Medicare physician fee schedule. 2012. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/NPC/Downloads/8-1-12-VBPM-NPC-Presentation.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

12. Physician compare redesign and public reporting webinar. 2013. Available at: http://ebookbrowsee.net/physician-compare-webinar-background-paper-508-compliant-pdf-d440592152. Accessed March 29, 2013.

13. What is meaningful use? Available at: http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/meaningful-use. Accessed March 29, 2013.

14. Marcotte L., Seidman J., Trudel K., et al. Achieving meaningful use of health information technology: a guide for physicians to the EHR incentive programs. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:731-6.

15. Miller H.D. Creating payment systems to accelerate value-driven health care: issues and options for policy reform. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund, 2007.

16. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS physician programs and alignment to date, 2012. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cqi/pcpi-032912-rapp.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2013.

Dr. Dorn, MPH, MHA, is assistant professor of medicine and vice chief of gastroenterology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Center for Functional GI Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Content from this column was originally published in the "Practice Management: The Road Ahead" section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2013;11:1212-5).

"Practice Management Toolbox" provides key information and resources necessary for facing the unique challenges of today’s clinical practices.

Resources for Practical Application: To view additional online resources about this topic and to access our Coding Corner, visit http://www.cghjournal.org/content/practice_management.