User login

Does concurrent use of clopidogrel and PPIs increase CV risk in patients with ACS?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

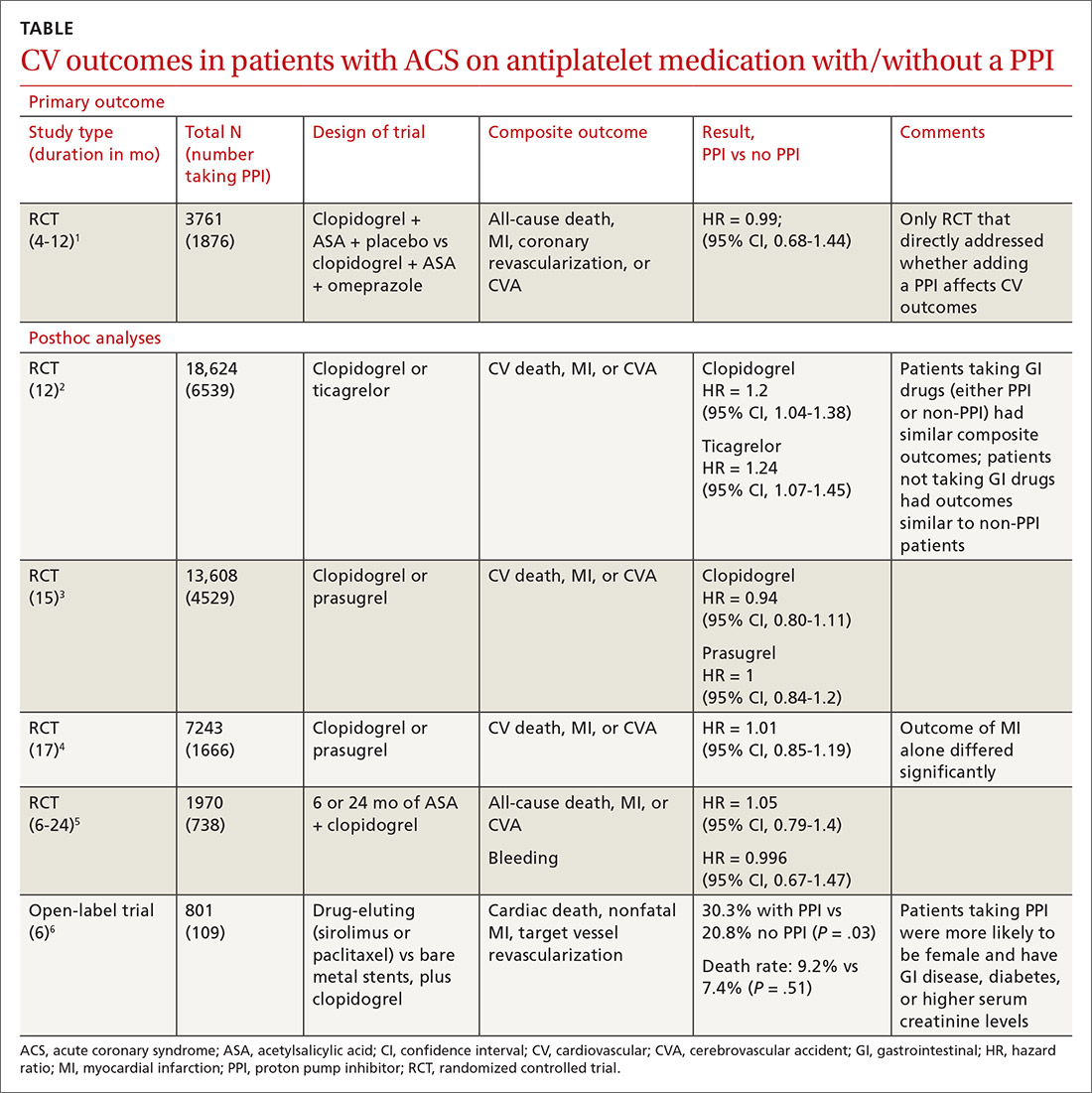

A double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled RCT comparing a combination of clopidogrel, aspirin, and omeprazole with clopidogrel, aspirin, and placebo found no increase in composite CV outcomes with the PPI (TABLE).1 Using a PPI did, however, significantly reduce gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03-0.56).Although several meta-analyses have been conducted, they all rely on this single RCT that directly addresses the question, plus post-hoc analyses of other RCTs.

Four of 5 analyses find little or no difference in CV outcomes with a PPI

Four of 5 posthoc analyses (which weren’t themselves randomized) of RCTs found unclear or no differences in composite CV outcomes with concurrent use of a PPI and antiplatelet therapy, after multivariate adjustment for differences in populations taking or not taking a PPI.

Posthoc analysis of the largest study found worse CV outcomes for both clopidogrel and ticagrelor with concomitant PPI use.2 However, patients on any GI drugs (PPI or non-PPI) had composite outcomes similar to patients on a PPI (PPI vs non-PPI GI treatment: HR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.79-1.23), and patients not taking GI drugs had fewer composite outcomes compared with patients on a PPI (clopidogrel vs no GI therapy: HR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.49; ticagrelor vs no GI therapy: HR = 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14-1.49). Researchers postulated that because the rate of composite outcomes increased equally for patients on any GI drug, the higher rate of CV adverse events with a PPI might have been related to GI disease rather than PPI use.

A similar posthoc analysis found no differences with or without PPI use among patients with ACS undergoing planned percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and assigned to clopidogrel or prasugrel.3 Researchers performed multivariate adjustment for differences in age, gender, ethnicity, and initial presence of unstable angina/non-ST-elevation MI.

A smaller study also found no significant differences in composite CV outcomes in patients using PPIs.4 Patients did have higher rates of MI (HR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42-0.91), but they were more likely to be older and have a previous diagnosis of non-ST-elevation MI, higher incidence of previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and history of peptic ulcer disease.

The fourth posthoc analysis of an RCT found that concomitant PPI use (91% of patients on lansoprazole) didn’t alter outcomes among patients undergoing PCI and receiving dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin.5 Researchers used a multivariate adjustment for differences in age, gender, and renal function and found no difference in outcomes during the 6-month or 24-month period. PPI prescription was at physician discretion. Researchers didn’t assess for dose-dependent effects of PPI.

A fifth, flawed study finds more adverse events with PPIs

A posthoc analysis of a smaller, open-label trial found increased major adverse cardiac events with PPI use among patients taking clopidogrel after PCI.6 Researchers didn’t adjust for differences in populations at baseline, however, and patients taking PPIs were more likely to be female or older and have diabetes, GI disease, or higher serum creatinine levels.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

The best evidence (a large RCT) found that adding a PPI to antiplatelet therapy didn’t alter CV outcomes in patients with ACS, but it did reduce GI bleeds. Hopefully this will give providers the confidence to use PPIs, if clinically indicated, in patients taking antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel or prasugrel.

1. Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909-1917.

2. Goodman SG, Clare R, Pieper KS, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitor use on cardiovascular outcomes with clopidogrel and ticagrelor: insights from the platelet inhibition and patient outcomes trial. Circulation. 2012;125:978-986.

3. O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374:989-997.

4. Nicolau JC, Bhatt DL, Roe MT, et al. Concomitant proton-pump inhibitor use, platelet activity, and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with prasugrel versus clopidogrel and managed without revascularization: insights from the Targeted Platelet Inhibition to Clarify the Optimal Strategy to Medically Manage Acute Coronary Syndromes trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170:683-694.e3.

5. Gargiulo G, Costa F, Ariotti S, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients treated with a 6- or 24-month dual-antiplatelet therapy duration: insights from the PROlonging Dual-antiplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia studY trial. Am Heart J. 2016;174:95-102.

6. Burkard T, Kaiser CA, Brunner-La Rocca H, et al. Combined clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitor therapy is associated with higher cardiovascular event rates after percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the BASKET trial. J Intern Med. 2012;271:257-263.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled RCT comparing a combination of clopidogrel, aspirin, and omeprazole with clopidogrel, aspirin, and placebo found no increase in composite CV outcomes with the PPI (TABLE).1 Using a PPI did, however, significantly reduce gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03-0.56).Although several meta-analyses have been conducted, they all rely on this single RCT that directly addresses the question, plus post-hoc analyses of other RCTs.

Four of 5 analyses find little or no difference in CV outcomes with a PPI

Four of 5 posthoc analyses (which weren’t themselves randomized) of RCTs found unclear or no differences in composite CV outcomes with concurrent use of a PPI and antiplatelet therapy, after multivariate adjustment for differences in populations taking or not taking a PPI.

Posthoc analysis of the largest study found worse CV outcomes for both clopidogrel and ticagrelor with concomitant PPI use.2 However, patients on any GI drugs (PPI or non-PPI) had composite outcomes similar to patients on a PPI (PPI vs non-PPI GI treatment: HR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.79-1.23), and patients not taking GI drugs had fewer composite outcomes compared with patients on a PPI (clopidogrel vs no GI therapy: HR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.49; ticagrelor vs no GI therapy: HR = 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14-1.49). Researchers postulated that because the rate of composite outcomes increased equally for patients on any GI drug, the higher rate of CV adverse events with a PPI might have been related to GI disease rather than PPI use.

A similar posthoc analysis found no differences with or without PPI use among patients with ACS undergoing planned percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and assigned to clopidogrel or prasugrel.3 Researchers performed multivariate adjustment for differences in age, gender, ethnicity, and initial presence of unstable angina/non-ST-elevation MI.

A smaller study also found no significant differences in composite CV outcomes in patients using PPIs.4 Patients did have higher rates of MI (HR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42-0.91), but they were more likely to be older and have a previous diagnosis of non-ST-elevation MI, higher incidence of previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and history of peptic ulcer disease.

The fourth posthoc analysis of an RCT found that concomitant PPI use (91% of patients on lansoprazole) didn’t alter outcomes among patients undergoing PCI and receiving dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin.5 Researchers used a multivariate adjustment for differences in age, gender, and renal function and found no difference in outcomes during the 6-month or 24-month period. PPI prescription was at physician discretion. Researchers didn’t assess for dose-dependent effects of PPI.

A fifth, flawed study finds more adverse events with PPIs

A posthoc analysis of a smaller, open-label trial found increased major adverse cardiac events with PPI use among patients taking clopidogrel after PCI.6 Researchers didn’t adjust for differences in populations at baseline, however, and patients taking PPIs were more likely to be female or older and have diabetes, GI disease, or higher serum creatinine levels.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

The best evidence (a large RCT) found that adding a PPI to antiplatelet therapy didn’t alter CV outcomes in patients with ACS, but it did reduce GI bleeds. Hopefully this will give providers the confidence to use PPIs, if clinically indicated, in patients taking antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel or prasugrel.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled RCT comparing a combination of clopidogrel, aspirin, and omeprazole with clopidogrel, aspirin, and placebo found no increase in composite CV outcomes with the PPI (TABLE).1 Using a PPI did, however, significantly reduce gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03-0.56).Although several meta-analyses have been conducted, they all rely on this single RCT that directly addresses the question, plus post-hoc analyses of other RCTs.

Four of 5 analyses find little or no difference in CV outcomes with a PPI

Four of 5 posthoc analyses (which weren’t themselves randomized) of RCTs found unclear or no differences in composite CV outcomes with concurrent use of a PPI and antiplatelet therapy, after multivariate adjustment for differences in populations taking or not taking a PPI.

Posthoc analysis of the largest study found worse CV outcomes for both clopidogrel and ticagrelor with concomitant PPI use.2 However, patients on any GI drugs (PPI or non-PPI) had composite outcomes similar to patients on a PPI (PPI vs non-PPI GI treatment: HR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.79-1.23), and patients not taking GI drugs had fewer composite outcomes compared with patients on a PPI (clopidogrel vs no GI therapy: HR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.49; ticagrelor vs no GI therapy: HR = 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14-1.49). Researchers postulated that because the rate of composite outcomes increased equally for patients on any GI drug, the higher rate of CV adverse events with a PPI might have been related to GI disease rather than PPI use.

A similar posthoc analysis found no differences with or without PPI use among patients with ACS undergoing planned percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and assigned to clopidogrel or prasugrel.3 Researchers performed multivariate adjustment for differences in age, gender, ethnicity, and initial presence of unstable angina/non-ST-elevation MI.

A smaller study also found no significant differences in composite CV outcomes in patients using PPIs.4 Patients did have higher rates of MI (HR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42-0.91), but they were more likely to be older and have a previous diagnosis of non-ST-elevation MI, higher incidence of previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and history of peptic ulcer disease.

The fourth posthoc analysis of an RCT found that concomitant PPI use (91% of patients on lansoprazole) didn’t alter outcomes among patients undergoing PCI and receiving dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin.5 Researchers used a multivariate adjustment for differences in age, gender, and renal function and found no difference in outcomes during the 6-month or 24-month period. PPI prescription was at physician discretion. Researchers didn’t assess for dose-dependent effects of PPI.

A fifth, flawed study finds more adverse events with PPIs

A posthoc analysis of a smaller, open-label trial found increased major adverse cardiac events with PPI use among patients taking clopidogrel after PCI.6 Researchers didn’t adjust for differences in populations at baseline, however, and patients taking PPIs were more likely to be female or older and have diabetes, GI disease, or higher serum creatinine levels.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

The best evidence (a large RCT) found that adding a PPI to antiplatelet therapy didn’t alter CV outcomes in patients with ACS, but it did reduce GI bleeds. Hopefully this will give providers the confidence to use PPIs, if clinically indicated, in patients taking antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel or prasugrel.

1. Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909-1917.

2. Goodman SG, Clare R, Pieper KS, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitor use on cardiovascular outcomes with clopidogrel and ticagrelor: insights from the platelet inhibition and patient outcomes trial. Circulation. 2012;125:978-986.

3. O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374:989-997.

4. Nicolau JC, Bhatt DL, Roe MT, et al. Concomitant proton-pump inhibitor use, platelet activity, and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with prasugrel versus clopidogrel and managed without revascularization: insights from the Targeted Platelet Inhibition to Clarify the Optimal Strategy to Medically Manage Acute Coronary Syndromes trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170:683-694.e3.

5. Gargiulo G, Costa F, Ariotti S, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients treated with a 6- or 24-month dual-antiplatelet therapy duration: insights from the PROlonging Dual-antiplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia studY trial. Am Heart J. 2016;174:95-102.

6. Burkard T, Kaiser CA, Brunner-La Rocca H, et al. Combined clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitor therapy is associated with higher cardiovascular event rates after percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the BASKET trial. J Intern Med. 2012;271:257-263.

1. Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909-1917.

2. Goodman SG, Clare R, Pieper KS, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitor use on cardiovascular outcomes with clopidogrel and ticagrelor: insights from the platelet inhibition and patient outcomes trial. Circulation. 2012;125:978-986.

3. O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374:989-997.

4. Nicolau JC, Bhatt DL, Roe MT, et al. Concomitant proton-pump inhibitor use, platelet activity, and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with prasugrel versus clopidogrel and managed without revascularization: insights from the Targeted Platelet Inhibition to Clarify the Optimal Strategy to Medically Manage Acute Coronary Syndromes trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170:683-694.e3.

5. Gargiulo G, Costa F, Ariotti S, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients treated with a 6- or 24-month dual-antiplatelet therapy duration: insights from the PROlonging Dual-antiplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia studY trial. Am Heart J. 2016;174:95-102.

6. Burkard T, Kaiser CA, Brunner-La Rocca H, et al. Combined clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitor therapy is associated with higher cardiovascular event rates after percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the BASKET trial. J Intern Med. 2012;271:257-263.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No. Adding a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in patients taking antiplatelet medications such as clopidogrel for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) doesn’t increase the composite risk of cardiovascular (CV) events: CV death, myocardial infarction (MI), and cerebrovascular accident (CVA) (strength of recommendation: B, randomized, controlled trial [RCT] and prepon-derance of posthoc analyses of large RCTs).

Does vitamin D supplementation reduce asthma exacerbations?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

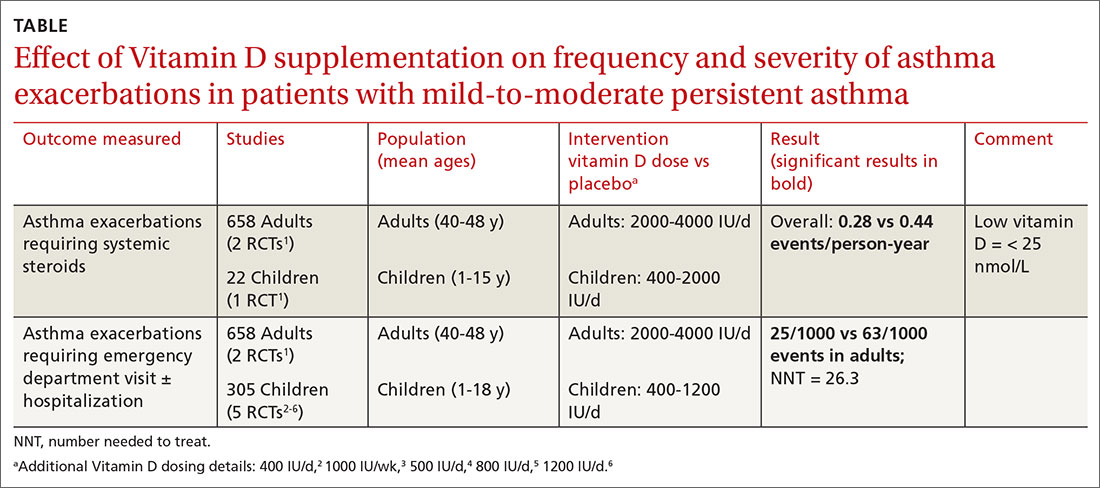

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, to some extent it does, and primarily in patients with low vitamin D levels. Supplementation reduces asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids by 30% overall in adults and children with mild-to-moderate asthma (number needed to treat [NNT] = 7.7). The outcome is driven by the effect in patients with vitamin D levels < 25 nmol/L (NNT = 4.3), however; supplementation doesn’t decrease exacerbations in patients with higher levels. Supplementation also reduces, by a smaller amount (NNT = 26.3), the odds of exacerbations requiring emergency department care or hospitalization (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

In children, vitamin D supplementation may also reduce exacerbations and improve symptom scores (SOR: C, low-quality RCTs).

Vitamin D doesn’t improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or standardized asthma control test scores. Also, it isn’t associated with serious adverse effects (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Do prophylactic antipyretics reduce vaccination-associated symptoms in children?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of 13 RCTs (5077 patients) compared the effects of a prophylactic antipyretic (acetaminophen or ibuprofen, doses and schedules not described) with placebo in healthy children 6 years or younger undergoing routine childhood immunizations.1 Trials examined various schedules and combinations of vaccines. Researchers defined febrile reactions as a temperature of 38°C or higher and categorized pain as: none, mild (reaction to touch over vaccine site), moderate (protesting to limb movement), or severe (resisting limb movement).

Acetaminophen works better than ibuprofen for both fever and pain

Acetaminophen prophylaxis resulted in fewer febrile reactions in the first 24 to 48 hours after vaccine administration than placebo following both primary (odds ratio [OR] = 0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.48) and booster vaccinations (OR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.93). Acetaminophen also reduced pain of all grades (primary vaccination: OR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.7; booster vaccination: OR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.48-0.84).

In contrast, ibuprofen prophylaxis had no effect on early febrile reactions for either primary or booster vaccinations. It reduced pain of all grades after primary vaccination (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49-0.88) but not after boosters (OR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.59-1.81).

Reduced antibody response doesn’t affect seroprotective levels

Acetaminophen also generally reduced the antibody response compared with placebo (assessed using the geometric mean concentration [GMC], a statistical technique for comparing values that change logarithmically).1 GMC results are difficult to interpret clinically, however, and they differed by vaccine, antigen, and primary or booster vaccination status.

Nevertheless, patients mounted seroprotective antibody levels with or without acetaminophen prophylaxis, and the nasopharyngeal carriage rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae didn’t change. Researchers didn’t publish the antibody responses to ibuprofen, nor did they track actual infection rates.

How do antipyretics work with newer combination vaccines?

A subsequent trial evaluated the immune response in 908 children receiving newer combination vaccines (DTaP/HBV/IPV/Hib and PCV13) who were randomized to 5 groups: acetaminophen 15 mg/kg at vaccination and 6 to 8 hours later; acetaminophen 15 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg/dose at vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; and placebo.2

Patients received age-appropriate vaccination and their assigned antipyretic (or placebo) at 2, 3, 4 and 12 months of age. Researchers measured the immune response at 5 and 13 months of age.

Continue to: Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group...

Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group had fever on Day 1 or 2 after vaccination, compared with 10% to 20% of the placebo group (no P value given). Antipyretic use produced lower antibody GMC responses for antipertussis and antitetanus vaccines at 5 months but not at 13 months. Patients achieved the prespecified effective antibody levels at both 5 and 13 months, regardless of intervention.

Antipyretics don’t affect immune response with inactivated flu vaccine

A 2017 RCT investigated the effect of either prophylactic acetaminophen (15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) or ibuprofen (10 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) on immune response in children receiving inactivated influenza vaccine.3 Researchers randomized 142 children into 3 treatment groups (acetaminophen, 59 children; ibuprofen, 24 children; placebo, 59 children). They defined seroconversion as a hemagglutinin inhibition assay titer of 1:40 postvaccination (if baseline titer was less than 1:10) or a 4-fold rise (if the baseline titer was ≥ 1:10).

All interventions resulted in similar seroconversion rates for all A or B influenza strains investigated. Vaccine protection-level responses ranged from 9% for B/Phuket to 100% for A/Switzerland. The trial didn’t report febrile reactions or infection rates.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2017, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) issued guidelines generally discouraging the use of antipyretics at the time of vaccination, but allowing their use later for local discomfort or fever that might arise after vaccination. The guidelines also noted that antipyretics at the time of vaccination didn’t reduce the risk of febrile seizures.4

Editor’s takeaway

Although ACIP doesn’t encourage giving antipyretics with vaccines, moderate-quality evidence suggests that prophylactic acetaminophen reduces fever and pain after immunizations by a reasonable amount without an apparent clinical downside.

1. Das RR, Panigrahi I, Naik SS. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106629.

2. Wysocki J, Center, KJ, Brzostek J, et al. A randomized study of fever prophylaxis and the immunogenicity of routine pediatric vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35:1926-1935.

3. Walter EB, Hornok CP, Grohskopf L, et al. The effect of antipyretics on immune response and fever following receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6664–6671.

4. Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of 13 RCTs (5077 patients) compared the effects of a prophylactic antipyretic (acetaminophen or ibuprofen, doses and schedules not described) with placebo in healthy children 6 years or younger undergoing routine childhood immunizations.1 Trials examined various schedules and combinations of vaccines. Researchers defined febrile reactions as a temperature of 38°C or higher and categorized pain as: none, mild (reaction to touch over vaccine site), moderate (protesting to limb movement), or severe (resisting limb movement).

Acetaminophen works better than ibuprofen for both fever and pain

Acetaminophen prophylaxis resulted in fewer febrile reactions in the first 24 to 48 hours after vaccine administration than placebo following both primary (odds ratio [OR] = 0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.48) and booster vaccinations (OR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.93). Acetaminophen also reduced pain of all grades (primary vaccination: OR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.7; booster vaccination: OR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.48-0.84).

In contrast, ibuprofen prophylaxis had no effect on early febrile reactions for either primary or booster vaccinations. It reduced pain of all grades after primary vaccination (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49-0.88) but not after boosters (OR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.59-1.81).

Reduced antibody response doesn’t affect seroprotective levels

Acetaminophen also generally reduced the antibody response compared with placebo (assessed using the geometric mean concentration [GMC], a statistical technique for comparing values that change logarithmically).1 GMC results are difficult to interpret clinically, however, and they differed by vaccine, antigen, and primary or booster vaccination status.

Nevertheless, patients mounted seroprotective antibody levels with or without acetaminophen prophylaxis, and the nasopharyngeal carriage rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae didn’t change. Researchers didn’t publish the antibody responses to ibuprofen, nor did they track actual infection rates.

How do antipyretics work with newer combination vaccines?

A subsequent trial evaluated the immune response in 908 children receiving newer combination vaccines (DTaP/HBV/IPV/Hib and PCV13) who were randomized to 5 groups: acetaminophen 15 mg/kg at vaccination and 6 to 8 hours later; acetaminophen 15 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg/dose at vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; and placebo.2

Patients received age-appropriate vaccination and their assigned antipyretic (or placebo) at 2, 3, 4 and 12 months of age. Researchers measured the immune response at 5 and 13 months of age.

Continue to: Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group...

Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group had fever on Day 1 or 2 after vaccination, compared with 10% to 20% of the placebo group (no P value given). Antipyretic use produced lower antibody GMC responses for antipertussis and antitetanus vaccines at 5 months but not at 13 months. Patients achieved the prespecified effective antibody levels at both 5 and 13 months, regardless of intervention.

Antipyretics don’t affect immune response with inactivated flu vaccine

A 2017 RCT investigated the effect of either prophylactic acetaminophen (15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) or ibuprofen (10 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) on immune response in children receiving inactivated influenza vaccine.3 Researchers randomized 142 children into 3 treatment groups (acetaminophen, 59 children; ibuprofen, 24 children; placebo, 59 children). They defined seroconversion as a hemagglutinin inhibition assay titer of 1:40 postvaccination (if baseline titer was less than 1:10) or a 4-fold rise (if the baseline titer was ≥ 1:10).

All interventions resulted in similar seroconversion rates for all A or B influenza strains investigated. Vaccine protection-level responses ranged from 9% for B/Phuket to 100% for A/Switzerland. The trial didn’t report febrile reactions or infection rates.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2017, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) issued guidelines generally discouraging the use of antipyretics at the time of vaccination, but allowing their use later for local discomfort or fever that might arise after vaccination. The guidelines also noted that antipyretics at the time of vaccination didn’t reduce the risk of febrile seizures.4

Editor’s takeaway

Although ACIP doesn’t encourage giving antipyretics with vaccines, moderate-quality evidence suggests that prophylactic acetaminophen reduces fever and pain after immunizations by a reasonable amount without an apparent clinical downside.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of 13 RCTs (5077 patients) compared the effects of a prophylactic antipyretic (acetaminophen or ibuprofen, doses and schedules not described) with placebo in healthy children 6 years or younger undergoing routine childhood immunizations.1 Trials examined various schedules and combinations of vaccines. Researchers defined febrile reactions as a temperature of 38°C or higher and categorized pain as: none, mild (reaction to touch over vaccine site), moderate (protesting to limb movement), or severe (resisting limb movement).

Acetaminophen works better than ibuprofen for both fever and pain

Acetaminophen prophylaxis resulted in fewer febrile reactions in the first 24 to 48 hours after vaccine administration than placebo following both primary (odds ratio [OR] = 0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.48) and booster vaccinations (OR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.93). Acetaminophen also reduced pain of all grades (primary vaccination: OR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.7; booster vaccination: OR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.48-0.84).

In contrast, ibuprofen prophylaxis had no effect on early febrile reactions for either primary or booster vaccinations. It reduced pain of all grades after primary vaccination (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49-0.88) but not after boosters (OR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.59-1.81).

Reduced antibody response doesn’t affect seroprotective levels

Acetaminophen also generally reduced the antibody response compared with placebo (assessed using the geometric mean concentration [GMC], a statistical technique for comparing values that change logarithmically).1 GMC results are difficult to interpret clinically, however, and they differed by vaccine, antigen, and primary or booster vaccination status.

Nevertheless, patients mounted seroprotective antibody levels with or without acetaminophen prophylaxis, and the nasopharyngeal carriage rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae didn’t change. Researchers didn’t publish the antibody responses to ibuprofen, nor did they track actual infection rates.

How do antipyretics work with newer combination vaccines?

A subsequent trial evaluated the immune response in 908 children receiving newer combination vaccines (DTaP/HBV/IPV/Hib and PCV13) who were randomized to 5 groups: acetaminophen 15 mg/kg at vaccination and 6 to 8 hours later; acetaminophen 15 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg/dose at vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; and placebo.2

Patients received age-appropriate vaccination and their assigned antipyretic (or placebo) at 2, 3, 4 and 12 months of age. Researchers measured the immune response at 5 and 13 months of age.

Continue to: Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group...

Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group had fever on Day 1 or 2 after vaccination, compared with 10% to 20% of the placebo group (no P value given). Antipyretic use produced lower antibody GMC responses for antipertussis and antitetanus vaccines at 5 months but not at 13 months. Patients achieved the prespecified effective antibody levels at both 5 and 13 months, regardless of intervention.

Antipyretics don’t affect immune response with inactivated flu vaccine

A 2017 RCT investigated the effect of either prophylactic acetaminophen (15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) or ibuprofen (10 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) on immune response in children receiving inactivated influenza vaccine.3 Researchers randomized 142 children into 3 treatment groups (acetaminophen, 59 children; ibuprofen, 24 children; placebo, 59 children). They defined seroconversion as a hemagglutinin inhibition assay titer of 1:40 postvaccination (if baseline titer was less than 1:10) or a 4-fold rise (if the baseline titer was ≥ 1:10).

All interventions resulted in similar seroconversion rates for all A or B influenza strains investigated. Vaccine protection-level responses ranged from 9% for B/Phuket to 100% for A/Switzerland. The trial didn’t report febrile reactions or infection rates.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2017, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) issued guidelines generally discouraging the use of antipyretics at the time of vaccination, but allowing their use later for local discomfort or fever that might arise after vaccination. The guidelines also noted that antipyretics at the time of vaccination didn’t reduce the risk of febrile seizures.4

Editor’s takeaway

Although ACIP doesn’t encourage giving antipyretics with vaccines, moderate-quality evidence suggests that prophylactic acetaminophen reduces fever and pain after immunizations by a reasonable amount without an apparent clinical downside.

1. Das RR, Panigrahi I, Naik SS. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106629.

2. Wysocki J, Center, KJ, Brzostek J, et al. A randomized study of fever prophylaxis and the immunogenicity of routine pediatric vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35:1926-1935.

3. Walter EB, Hornok CP, Grohskopf L, et al. The effect of antipyretics on immune response and fever following receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6664–6671.

4. Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

1. Das RR, Panigrahi I, Naik SS. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106629.

2. Wysocki J, Center, KJ, Brzostek J, et al. A randomized study of fever prophylaxis and the immunogenicity of routine pediatric vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35:1926-1935.

3. Walter EB, Hornok CP, Grohskopf L, et al. The effect of antipyretics on immune response and fever following receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6664–6671.

4. Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes for acetaminophen, not so much for ibuprofen. Prophylactic acetaminophen reduces the odds of febrile reactions in the first 48 hours after vaccination by 40% to 65% and pain of all grades by 36% to 43%. In contrast, prophylactic ibuprofen reduces pain of all grades by 34% only after primary vaccination and doesn’t alter pain after boosters. Nor does it alter early febrile reactions (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [RCTs] with moderate-to-high risk of bias).

Prophylactic administration of acetaminophen or ibuprofen is associated with a reduction in antibody response to the primary vaccine series and to influenza vaccine, but antibody responses still achieve seroprotective levels (SOR: C, bench research).

Does screening by primary care providers effectively detect melanoma and other skin cancers?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Possibly. No trials have directly assessed detection of melanoma and other skin cancers by primary care providers.

Training a group comprised largely of primary care physicians to perform skin cancer screening was associated with a 41% increase in skin cancer diagnoses but no change in melanoma mortality.

Visual screening for melanoma by primary care physicians is 40% sensitive and 86% specific (compared with 49% and 98%, respectively, for dermatologists and plastic surgeons).

Melanomas found by visual screening are 38% more likely to be thin (≤ 0.75 mm) than melanomas discovered without screening, which correlates with improved outcomes.

Visual skin cancer screening overall is associated with false-positive rates as follows: 28 biopsies for each melanoma detected, 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma, and 28 to 56 biopsies for squamous cell carcinoma. False-positive rates are higher for women—as much as double the rate for men—and younger patients—as much as 20-fold the rate for older patients (strength of recommendations for all foregoing statements: B, cohort studies).

Do group visits improve HbA1c more than individual visits in patients with T2DM?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2012 systematic review of 21 RCTs examined the effect of group-based diabetes education on HbA1c in 2833 adults with T2DM.1 Intervention groups participated in at least 1 group session lasting an hour led by a health professional or team (eg, physician, nurse, diabetes educator); controls received usual care. Most trials involved 6 to 20 hours of group-based education delivered over 1 to 10 months, although some trials continued the intervention for as long as 24 months. The mean HbA1c at baseline across all patients was 8.23%.

Professional-led group visitsimprove HbA1c

Group education resulted in a significant reduction in HbA1c compared with controls at 6 months (13 trials; 1883 patients; mean difference [MD]=−0.44%; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.69 to −0.19), 12 months (11 studies; 1503 patients; MD=−0.46%; 95% CI, −0.74 to −0.18), and 24 months (3 studies; 397 patients; MD=−0.87%; 95% CI, −1.25 to −0.49). The trials had high heterogeneity, except for the 3 trials with a 24-month end-point (I2 = 0). Most studies had a moderate or high risk of bias.

A larger 2017 meta-analysis enrolling 8533 adults with T2DM came to similar conclusions, although it included a small number of nonrandomized trials (40 RCTs, 3 cluster RCTs, and 4 controlled clinical trials).2 Thirteen of the RCTs overlapped with the previously described systematic review.1 Interventions had to include at least 1 group session with 4 or more adult patients lasting at least 1 hour. In most studies, interventions continued between 4 and 12 months, although some ran 60 months. Controls received usual care. The mean HbA1c at baseline across all patients was 8.3%.