User login

Master Class: Office Evaluation for Incontinence

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

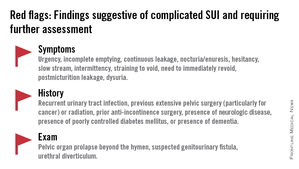

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

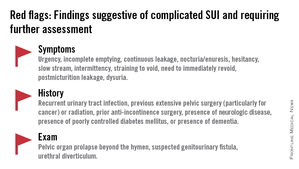

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Master Class: Office evaluation for incontinence

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

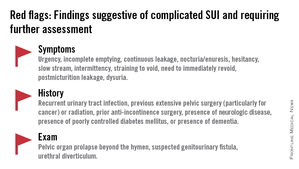

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.