User login

Diverticulitis: A Primer for Primary Care Providers

CE/CME No: CR-1808

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the pathophysiology of diverticulitis.

• Describe the spectrum of clinical presentations of diverticulitis.

• Understand the diagnostic evaluation of diverticulitis.

• Differentiate the management of uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis.

FACULTY

Priscilla Marsicovetere is Assistant Professor of Medical Education and Surgery, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, and Program Director for the Franklin Pierece University, PA Program, Lebanon, New Hampshire. She practices with Emergency Services of New England, Springfield Hospital, Springfield, Vermont.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through July 31, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

Treatment of this common complication of diverticular disease is predicated on whether the presentation signals uncomplicated or complicated disease. While some uncomplicated cases require hospitalization, many are amenable to primary care outpatient, and often conservative, management. The longstanding practice of antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated cases is now considered a selective, rather than a routine, option.

Diverticular disease is one of the most common conditions in the Western world and one of the most frequent indications for gastrointestinal-related hospitalization.1 It is among the 10 most common diagnoses in patients presenting to the clinic or emergency department with acute abdominal pain.2 Prevalence increases with age: Up to 60% of persons older than 60 are affected.3 The most common complication of diverticular disease is diverticulitis, which occurs in up to 25% of patients.4

The spectrum of clinical presentations of diverticular disease ranges from mild, uncomplicated disease that can be treated in the outpatient setting to complicated disease with sepsis and possible emergent surgical intervention. The traditional approach to diverticulitis has been management with antibiotics and likely sigmoid colectomy, but recent studies support a paradigm shift toward more conservative, nonsurgical treatment.

This article highlights current trends in diagnosis and management of acute diverticulitis.

DEFINITION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

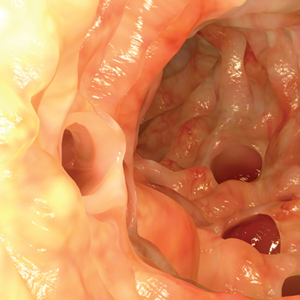

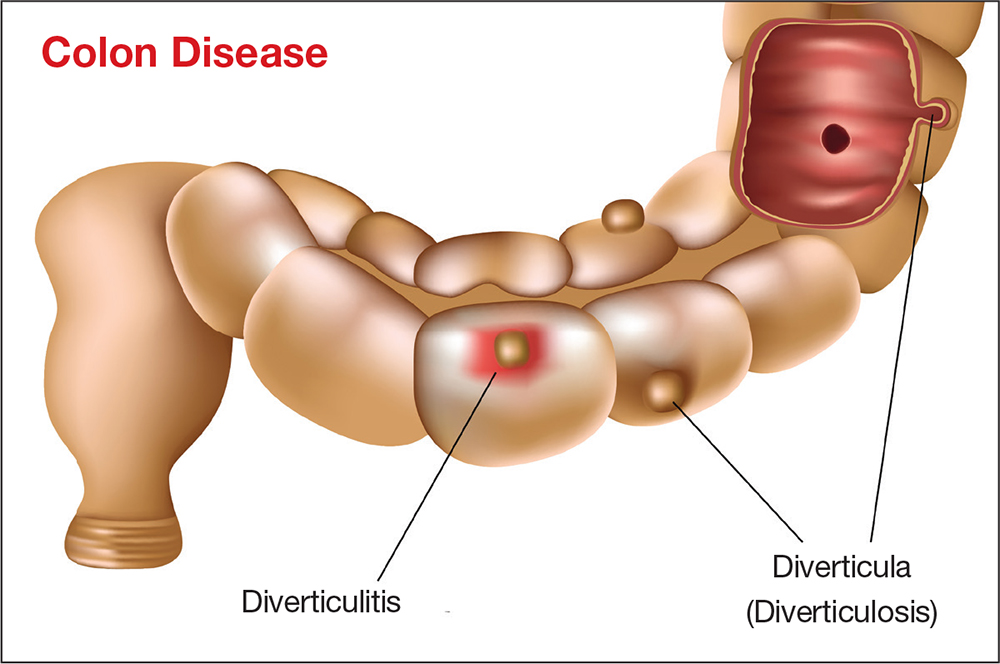

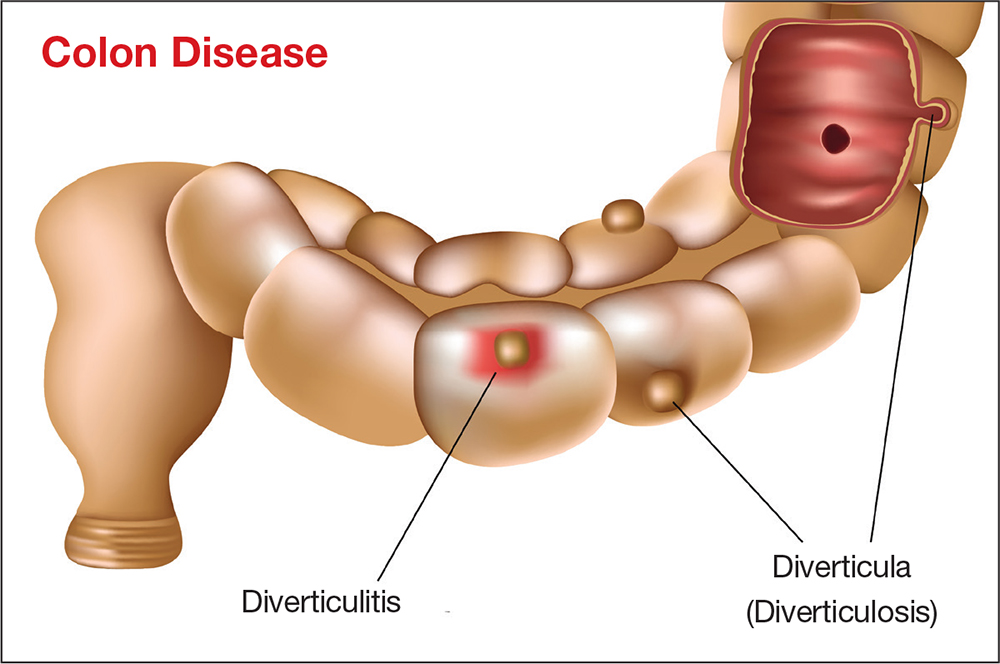

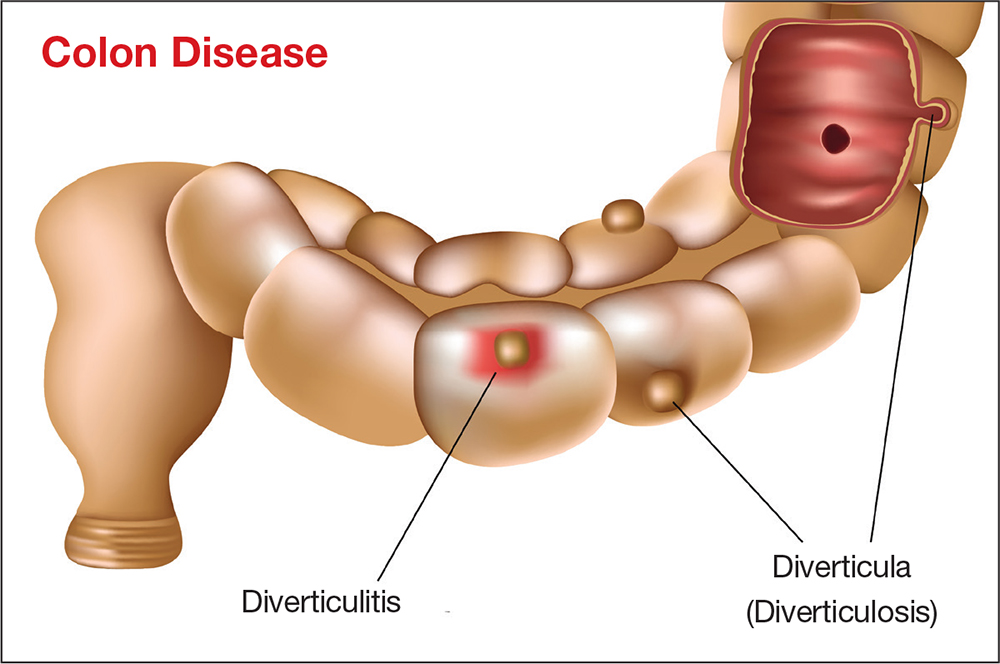

Diverticular disease is marked by sac-like outpouchings, called diverticula, that form at structurally weak points of the colon wall, predominantly in the descending and sigmoid colon.5 The prevalence of diverticular disease is increasing globally, affecting more than 10% of people older than 40, as many as 60% of those older than 60, and more than 70% of people older than 80.1,3 The mean age for hospital admission for acute diverticulitis is 63.3

Worldwide, males and females are affected equally.3 In Western society, the presence of diverticula, also called diverticulosis, is more often left-sided; right-sided disease is more prevalent in Asia.3,5

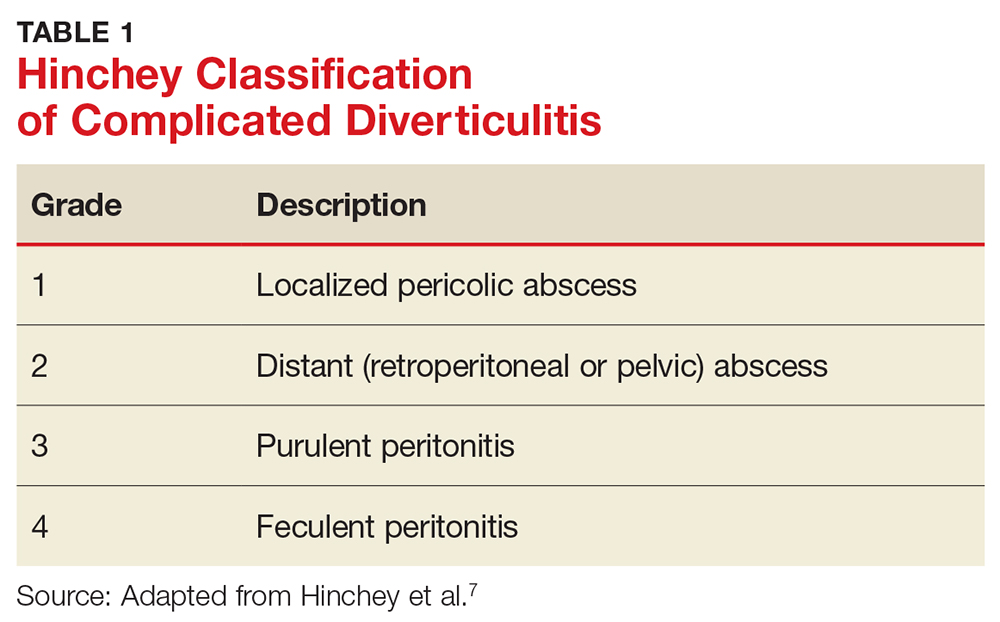

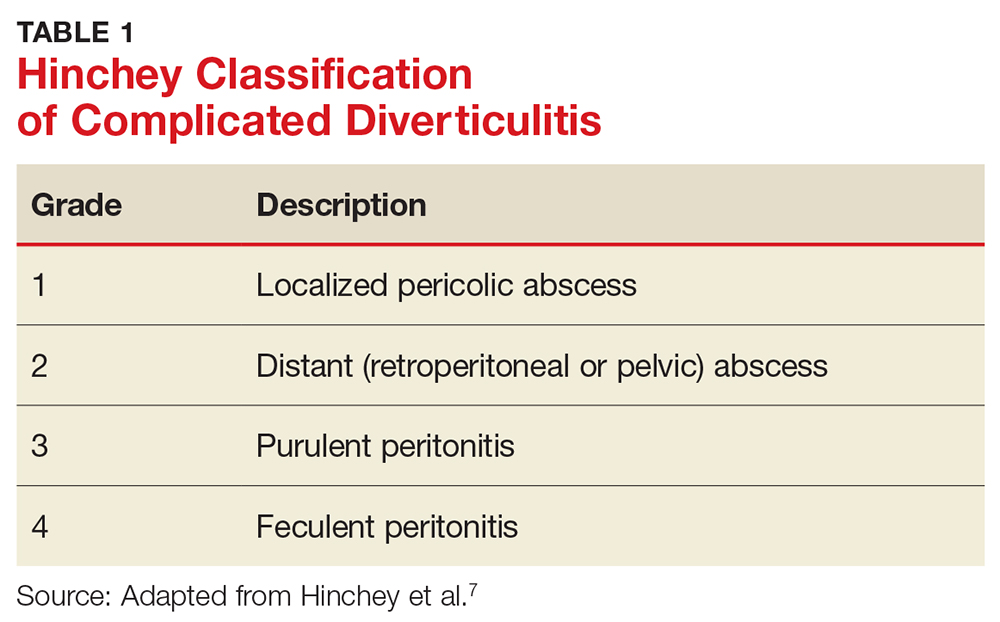

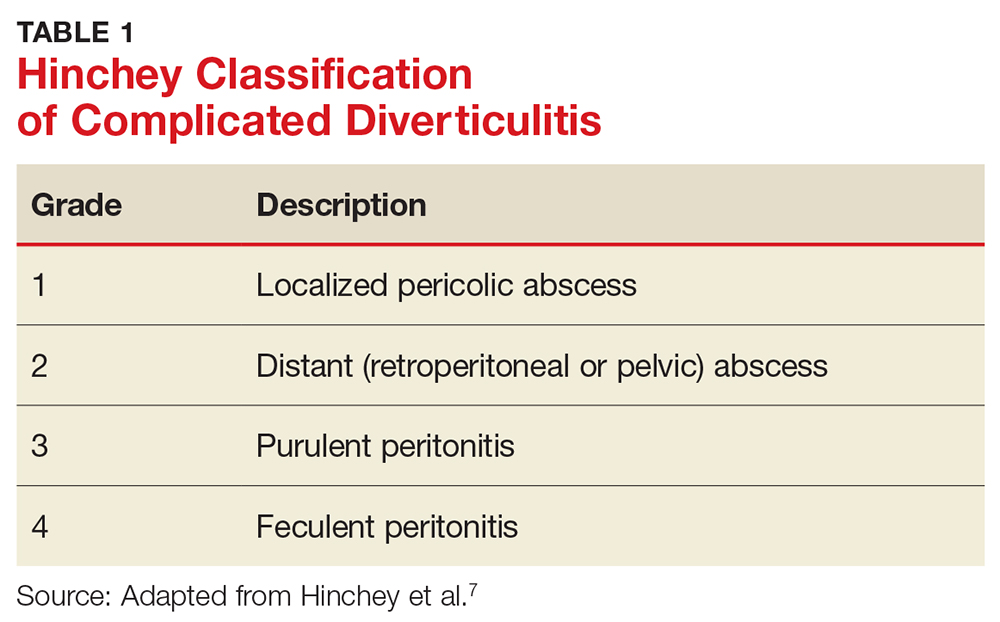

The most common complication of diverticular disease is diverticulitis—inflammation of a diverticulum—which affects 10% to 25% of patients with diverticular disease during their lifetime.4,5 Diverticulitis can be classified as uncomplicated (characterized by colonic wall thickening or pericolic inflammatory changes) or complicated (characterized by abscesses, fistulae, obstruction, or localized or free perforations).1,6 As many as 25% of diverticulitis cases are considered complicated.4,5 The severity of diverticulitis is commonly graded using the Hinchey Classification (Table 1).1,7

Continue to: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Diverticula tend to occur in areas where the colonic wall is weak: namely, between the mesenteric and antimesenteric taeniae, where the vasa recta penetrate the muscle—points of entry of blood vessels through the colonic wall.1,4 The exact pathogenesis of diverticular disease is not completely understood but is thought to be multifactorial. Microscopic studies have shown muscular atrophy at the sites of diverticula, making them more susceptible to mucosal herniation in the setting of increased intraluminal pressure.1 Additional potential contributing factors include alterations in colonic microbiota, muscular dysfunction or dysmotility, lifestyle, and genetics.

Diverticulitis is the result of microscopic and macroscopic perforation of diverticula. Historically, the perforations were thought to result from obstruction of a diverticulum by a fecalith, leading to increased pressure within the outpouching, followed by perforation.3 Such obstruction is now thought to be rare. A more recent theory suggests that increased intraluminal pressure is due to inspissated food particles that lead to erosion of the diverticular wall, causing focal inflammation and necrosis and resulting in perforation.3 Microperforations can easily be contained by surrounding mesenteric fat; however, progression to abscess, fistulization, or intestinal obstruction can occur. Frank bowel wall perforation is not contained by mesenteric fat and can lead quickly to peritonitis and death if not treated emergently.

RISK FACTORS

Dietary fiber

In 1971, Burkitt was the first to posit that diverticular disease developed due to small quantities of fiber in the diet that led to increased intracolonic pressures.8 His theory was based on the observation that residents of several African countries, who ate a high-fiber diet, had a low incidence of diverticular disease. Burkitt hypothesized that this was due to shorter colonic transit time induced by high dietary fiber.

Several studies conducted since Burkitt made his observations have examined the association of dietary fiber and diverticular disease, with conflicting results. In 1998, Aldoori et al found that a low-fiber diet increases the incidence of symptomatic diverticular disease.9 However, in 2012, a large cohort study of patients undergoing colonoscopy found that those who reported the highest fiber intake were at highest risk for diverticulosis.10 In 2013, Peery et al examined the relationship among bowel habits, dietary fiber, and asymptomatic diverticulosis and found that less-frequent bowel movements and hard stools were associated with a decreased risk for diverticulosis.11 In 2017, a prospective cohort study of nearly 50,000 men without a known history of diverticulosis showed that diets high in red meat were associated with a higher incidence of diverticulitis over nearly three decades of follow-up, whereas a diet high in fiber was associated with a decreased incidence of diverticulitis.12

Although no definitive association has been found between dietary fiber intake and risk for diverticulosis, some studies have demonstrated an association between dietary fiber and diverticular complications. In 2014, Crowe et al found that consumption of a high-fiber diet was associated with a lower risk for hospital admission and death from diverticular disease.13 Recent guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) on diverticulitis recommend high dietary fiber intake in patients with a history of acute diverticulitis.14 However, no study has shown a reversal of the process or a reduction in the number of episodes of diverticulitis after adoption of a high-fiber diet.

Continue to: Historically, patients with diverticulitis...

Historically, patients with diverticulitis were advised to avoid eating nuts, corn, popcorn, and seeds to reduce the risk for complications. But studies have found no support for this caution. In a 2008 large, prospective study of men without known diverticular disease, the researchers found no association between nut, corn, or popcorn ingestion and diverticulitis; in fact, increased nut intake was specifically associated with a lower risk for diverticulitis.15

Smoking

Smoking has been linked to diverticulitis and has been associated with a threefold risk for complications, including severe diverticulitis.16,17 An increased risk for recurrent episodes has also been found in smokers following surgical intervention.17

Medications

NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and opioids have been associated with an increased risk for perforated diverticulitis.18,19 A significant association has been found between NSAID use and severity of diverticulitis, including perforation; one study reported a relative risk of 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 10.5 to 1.47) for diverticulitis with regular use of aspirin (≥ 2x/wk).20,21

More frequent steroid use has been found in patients with complicated diverticulitis, compared to patients with uncomplicated disease (7.3% vs 3.3%; P = .015).22 A systematic review of five studies comparing patients with and without steroid use showed significantly higher odds of diverticular perforation in patients taking a steroid.23 Pooled data showed significantly increased odds of perforation and abscess formation with use of an NSAID (odds ratio [OR], 2.49), steroid (OR, 9.08), or opioid (OR, 2.52).22

Continue to: Vitamin D

Vitamin D

In a 2013 retrospective cohort study of 9,116 patients with uncomplicated diverticulosis and 922 patients who developed diverticulitis that required hospitalization, Maguire et al examined the association of prediagnostic serum levels of vitamin D and diverticulitis.24 Among patients with diverticulosis, higher prediagnostic levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D were significantly associated with a lower risk for diverticulitis—indicating that vitamin D deficiency could be involved in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis.

The association between diverticulitis and vitamin D levels was supported by an additional study in 2015, in which the authors investigated the association between ultraviolet (UV) light and diverticulitis.25 They identified nonelective diverticulitis admissions in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database and linked hospital locations to geographic UV data. They examined UV exposure in relation to risk for admission for diverticulitis and found that, compared with high-UV (UV4) areas, low-UV (UV1) areas had a higher rate of diverticulitis (751.8/100,000 admissions, compared with 668.1/100,000 admissions, respectively [P < .001]), diverticular abscess (12.0% compared with 9.7% [P < .001]), and colectomy (13.5% compared with 11.5% [P < .001]). They also observed significant seasonal variation, with a lower rate of diverticulitis in winter (645/100,000 admissions) compared with summer (748/100,000 admissions [P < .001]). Because UV exposure largely determines vitamin D status, these findings are thought to support a role for vitamin D in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis.

Genetics

Two studies found an association between genetics and diverticular disease. A 2012 study using The Swedish Twin Registry found that if one twin is affected with the disease, the odds that the other will be affected was 7.15 in monozygotic (identical) twins and 3.20 in dizygotic (fraternal) twins.26 A 2013 Danish twin study found a relative risk of 2.92 in twin siblings compared to the general population.27 Both studies estimated the genetic contribution to diverticular disease to be 40% to 50%.26,27

Obesity

Several large prospective studies have shown a positive association between high BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio and risk for diverticulitis.4 A BMI > 30 was found to increase the relative risk of acute diverticulitis by 1.78, compared with a normal BMI.17 In a large, prospective, population-based cohort study in 2016, Jamal Talabani et al found that obese persons had twice the risk for admission for acute colonic diverticulitis than normal-weight persons did.28 Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio were also independently associated with risk for diverticulitis. The pathophysiology of the associations is not clearly understood but may involve pro-inflammatory changes of adipose tissue, which secrete cytokines that promote an inflammatory response, and changes in gut microbiota.4,12

Physical activity

Data on the association of physical activity and diverticulitis is inconsistent. Some studies have found as much as a 25% decrease in the risk for diverticulitis with increased physical activity; more recent studies (2013 and 2016), on the other hand, found no association between diverticulosis and physical activity.11,17,19,28

Continue to: CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of diverticulitis typically depends on the severity of inflammation and the presence (or absence) of complications. The most common presenting symptom is left lower-quadrant abdominal pain, which occurs in approximately 70% of cases and lasts for longer than 24 hours.29 Fever (usually < 102°F), leukocytosis, nausea, vomiting, and changes in bowel function may also be present.1,30,31 Approximately 50% of patients report constipation in diverticular disease; 20% to 35% report diarrhea.5

Patients may also report dysuria, secondary to irritation of the bladder by an inflamed segment of colon.3,17 Patients may report fecaluria, pneumaturia, or pyuria, which indicate a colovesical fistula.1 Passage of feces or flatus through the vagina indicates a colovaginal fistula.

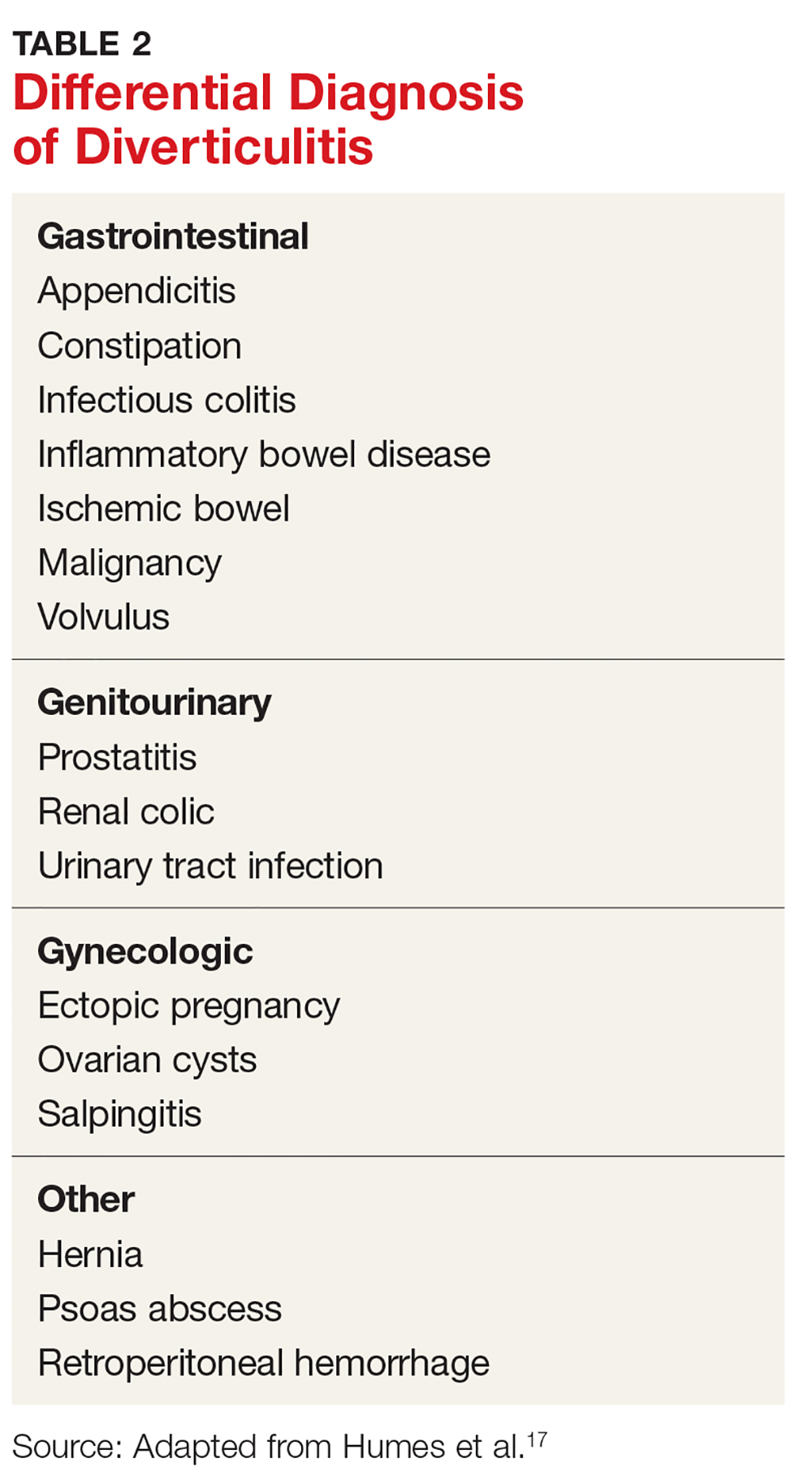

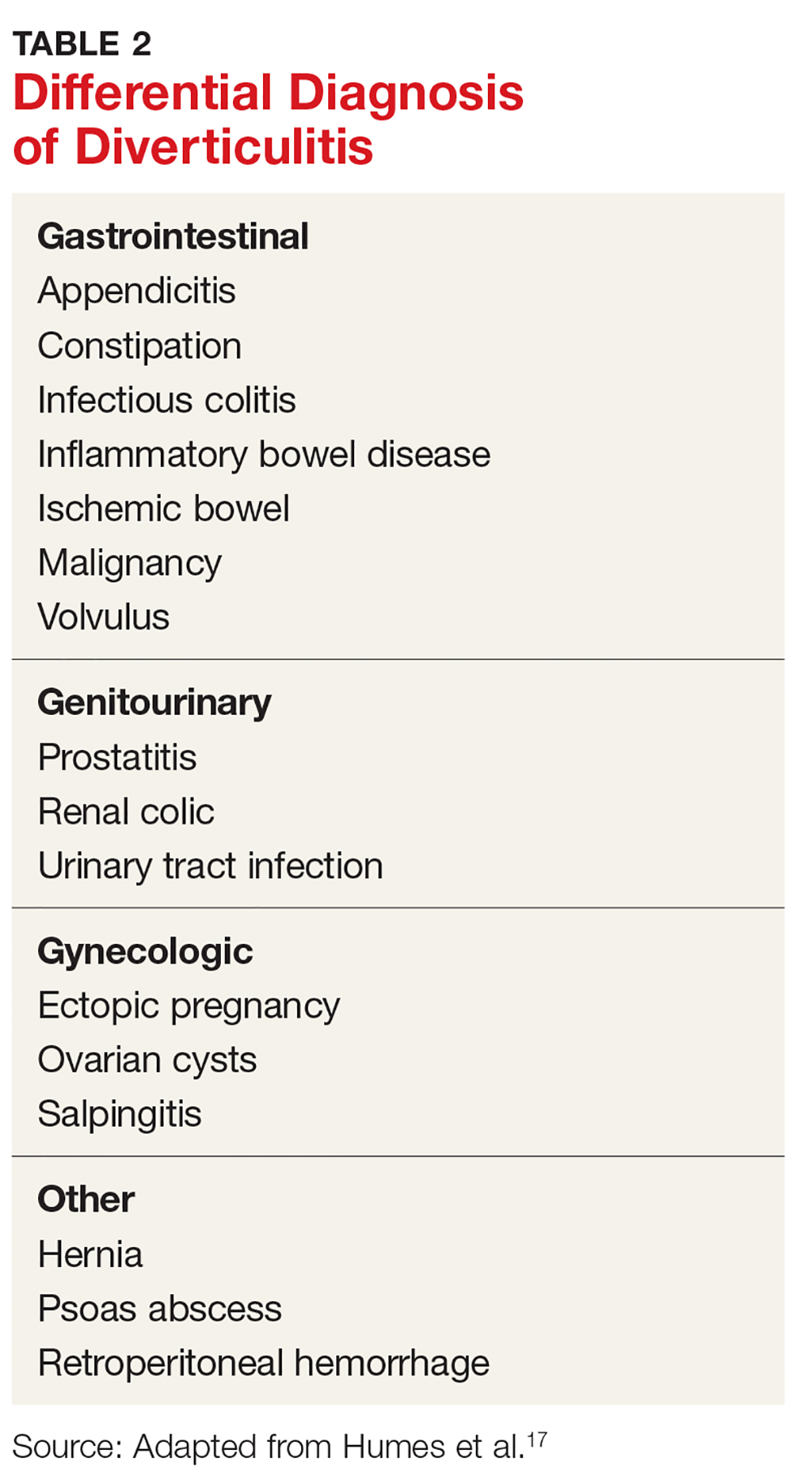

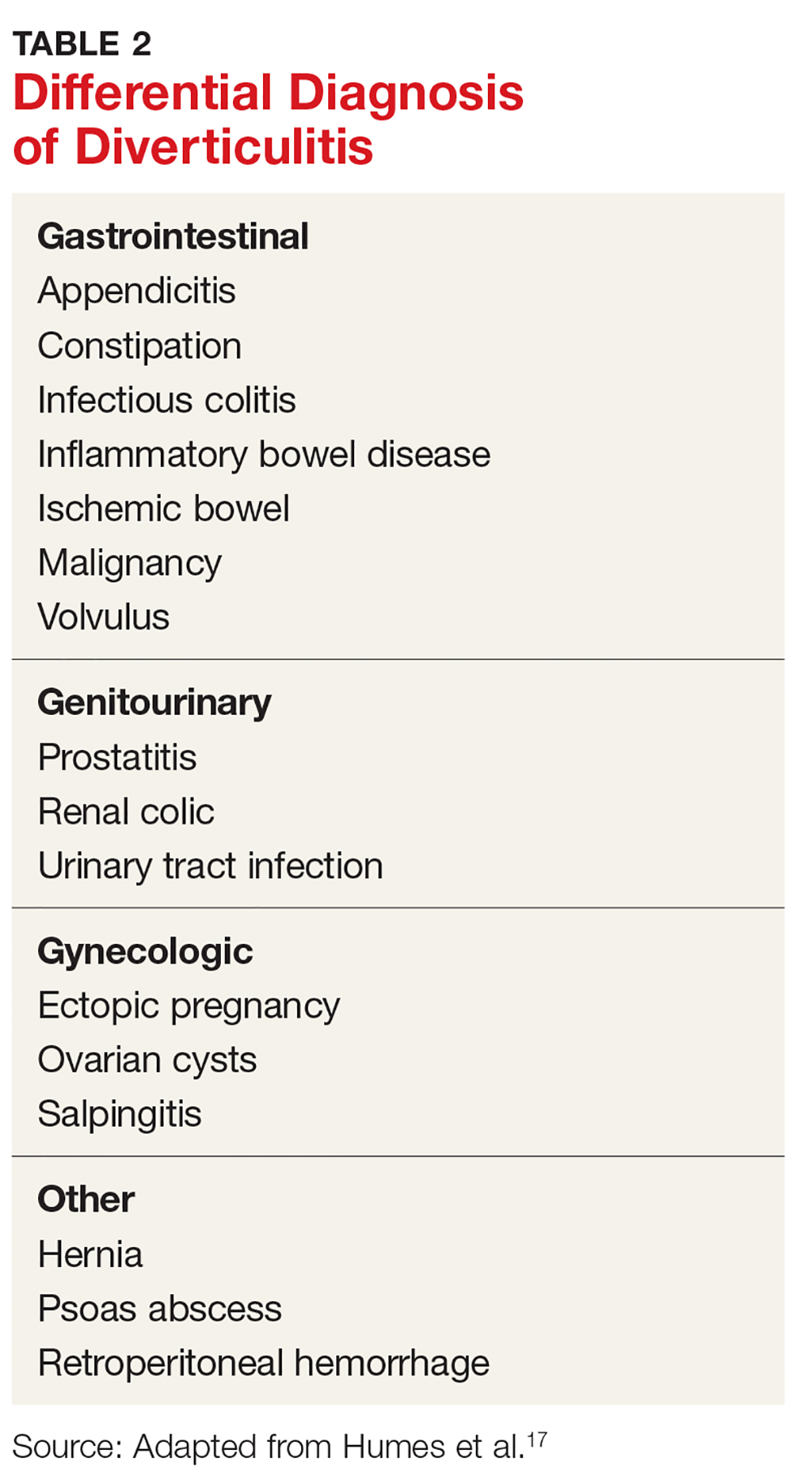

The differential diagnosis of diverticulitis is listed in Table 2.17

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination in diverticulitis will almost always elicit tenderness to palpation over the area of inflammation, typically in the left lower quadrant. This is due to irritation of the peritoneum.3 A palpable mass may be present in as many as 20% of patients if an abscess is present. Bowel sounds may be hypoactive or hyperactive if there is a bowel obstruction.17 In cases of frank bowel-wall perforation, patients can present with peritoneal signs of rigidity, guarding, and rebound tenderness.3,31 Tachycardia, hypotension, and shock are rare but possible findings. Digital rectal examination may reveal tenderness or a mass if a pelvic abscess is present.17,31

DIAGNOSTICS

The diagnosis of acute diverticulitis can often be made clinically, based on the history and physical examination. Because clinical diagnosis can be inaccurate in as many as 68% of cases, however, laboratory testing and imaging play an important role in diagnosis.3

Continue to: Clinical laboratory studies

Clinical laboratory studies

Because leukocytosis is present in approximately one-half of patients with diverticulitis, a complete blood count (CBC) should be obtained; that recommendation notwithstanding, approximately one-half of patients with diverticulitis have a normal white blood cell count.29,30 A urine test of human chorionic gonadotropin should be ordered to exclude pregnancy in all premenopausal and perimenopausal women, particularly if antibiotics, imaging, or surgery are being considered.31 Urinalysis can assess for urinary tract infection.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the utility of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the workup of acute diverticulitis. In general, patients with a complicated episode will present with a significantly higher CRP level than that of uncomplicated disease.32 Kechagias et al found that the CRP level at initial evaluation may be helpful in predicting the clinical severity of the attack. A CRP level > 170 mg/L has been found to have a greater probability of severe disease, warranting CT and referral for hospitalization.33 A low CRP level was more likely to herald a mild course of disease that is amenable to outpatient antibiotic management or supportive care. This finding is consistent with previous reports of the association between CRP levels of 90 to 200 mg/L and the severity of diverticulitis.32,34

Imaging

Abdominopelvic CT with intravenous (IV) contrast. This imaging study is the gold standard diagnostic tool for diverticulitis, with sensitivity as high as 97%.3 CT can distinguish diverticulitis from other conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (based on a history of symptoms and the absence of CT findings), gastroenteritis, and gynecologic disease. It can also distinguish between uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis and therefore guide therapeutic interventions, such as percutaneous drainage of an intra-abdominal abscess. CT findings associated with uncomplicated diverticulitis include colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fluid and inflammatory changes, such as fat stranding. CT findings associated with complicated disease include abscess (paracolonic or pelvic), peritonitis (purulent or feculent), phlegmon, perforation, fistula, and obstruction.1,3

Ultrasonography (US) can also be used in the assessment of diverticulitis, although it has lower sensitivity (approximately 61% to 84%) than CT and is inferior to CT for showing the extent of large abscesses or free air.3,18,30 A typical US finding in acute diverticulitis is a thickened loop of bowel with a target-like appearance.17 Findings are highly operator-dependent, however, and accuracy is diminished in obese patients. US may be a good option for pregnant women to avoid ionizing radiation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another option for imaging in diverticulitis but is not routinely recommended. It provides excellent soft-tissue detail and does not deliver ionizing radiation, but it is not as sensitive as CT for identifying free air.18,31 Furthermore, MRI requires prolonged examination time, which may not be tolerated by acutely ill patients, and is not an option for patients with certain types of surgical clips, metallic fragments, or a cardiac pacemaker.

Continue to: Abdominal radiography...

Abdominal radiography is useful to show free air, which would indicate perforation, and to show nonspecific abnormalities, such as bowel-gas patterns.31

MANAGEMENT

For decades, patients with diverticulitis were managed with antibiotics to cover colonic flora; many underwent urgent or emergent surgery to remove the affected segment of colon. Over the years, however, the treatment paradigm has shifted from such invasive management toward a nonsurgical approach—often, with equivalent or superior outcomes. More and more, management of diverticulitis is dictated by disease presentation: namely, whether disease is uncomplicated or complicated.1

Current guidelines recommend hospitalization, with possible surgical intervention, in complicated disease (free perforation, large abscesses, fistula, obstruction, stricture) and in patients who cannot tolerate oral hydration, who have a relevant comorbidity, or who do not have adequate support at home.35 Uncomplicated cases may also require hospitalization if certain criteria for admission are met: immunosuppression, severe or persistent abdominal pain, inability to tolerate oral intake, and significant comorbidity.5

Absent these criteria, outpatient management of uncomplicated diverticulitis is appropriate. After the treatment setting is determined, choice of intervention and length of treatment should be addressed.

Nonpharmacotherapeutic management

Dietary restrictions, from a full liquid diet to complete bowel rest, have been recommended for the management of acute diverticulitis. This recommendation is not supported by the literature, however. At least two studies have shown no association between an unrestricted diet and an increase in diverticular complications. In a 2013 retrospective cohort study, no increase in diverticular perforation or abscess was found with a diet of solid food compared to a liquid diet, a clear liquid diet, or no food by mouth.36 In a more recent (2017) prospective cohort study of 86 patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis, all of whom were on an unrestricted diet, only 8% developed complications.37

Continue to: There is no high-quality evidence for...

There is no high-quality evidence for instituting dietary restrictions in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. As such, permitting oral intake as tolerated is a reasonable option.

Pharmacotherapy

Antibiotics have long been the cornerstone of pharmacotherapy for acute diverticulitis, covering gram-negative rods and anaerobes. The rationale for such management is the long-held belief that diverticulitis is caused by an infectious process.38 Common outpatient regimens include

- Ciprofloxacin (500 mg every 12 h) plus metronidazole (500 mg every 8 h)

- Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (1 double-strength tablet every 12 h) plus metronidazole (500 mg every 8 h)

- Amoxicillin (875 mg)–clavulanate (1 tablet every 8 h) or extended-release amoxicillin–clavulanate (2 tablets every 12 h)

- Moxifloxacin (400 mg/d; for patients who cannot tolerate metronidazole or ß-lactam antibiotics).

Providers should always consult their local antibiogram to avoid prescribing antibiotics to which bacterial resistance exceeds 10%.

Despite widespread use of antibiotics for diverticulitis, multiple studies in recent years have shown no benefit to their use for uncomplicated cases. In 2012, Chabok et al investigated the need for antibiotic therapy to treat acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and found no statistically significant difference in outcome among patients treated with antibiotics and those managed conservatively.39 In 2014, Isacson et al performed a retrospective population-based cohort study to assess the applicability of a selective “no antibiotic” policy and its consequences in terms of complications and recurrence; the authors found that withholding antibiotics was safe and did not result in a higher complication or recurrence rate.40 Furthermore, in a 2017 multicenter study, Daniels et al conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing observation and antibiotic treatment for a first episode of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis in 528 patients and found no prolongation of recovery time, no increased rate of complications, and no need for surgical intervention in patients who were not treated with antibiotics.41

These studies are in agreement with the most recent AGA guidelines, which recommend selective, rather than routine, use of antibiotics for acute diverticulitis.14 This shift in approach may be due, in part, to a change in understanding of the etiology of the disease—from an infectious process to more of an inflammatory process.38

Continue to: For patients who require inpatient management of diverticulitis...

For patients who require inpatient management of diverticulitis, treatment typically involves IV antibiotics, fluids, and analgesics. Surgical treatment may be appropriate (see “Surgical treatment”).

Other agents used to manage diverticulitis include three that lack either strong or any data at all showing efficacy. The most recent AGA guidelines recommend against their use for this indication14:

Rifaximin. Two recent observational cohort studies, one from 2013 and the other from 2017, compared this poorly absorbed oral antibiotic with mesalamine to placebo or no treatment at all.42 Neither provided evidence that rifaximin treats or prevents diverticulitis.

Mesalamine. This anti-inflammatory has also been studied to prevent recurrence of diverticulitis. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of 1,182 patients, Raskin et al found that mesalamine did not reduce the rate of recurrence of diverticulitis, time to recurrence, or the number of patients requiring surgery.43 This conclusion was reiterated by a 2016 meta-analysis that found no evidence to support use of mesalamine in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence.44

Probiotics. Despite multiple studies undertaken to assess the efficacy of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of diverticular disease, strong data supporting their use are sparse. In 2016, Lahner et al examined 11 studies in which various probiotics were used to treat diverticular disease and found that, although there was a weak positive trend in the reduction and remission of abdominal symptoms, the evidence was not strong enough to recommend their routine use in managing the disease.45

Continue to: Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment

Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis can be treated nonsurgically in nearly all patients, regardless of whether treatment occurs in the inpatient or outpatient setting. For complicated disease, however, approximately 15% to 25% of patients require surgery. The main indication for emergent or urgent surgical intervention is colonic perforation, which can lead to acute peritonitis, sepsis, and associated morbidity and mortality.29

The decision to perform elective surgery should be made case by case, not routinely—such as after a recurrent episode of diverticulitis, when there has been a complication, or in young patients (< 50 years).1,11 Immunocompromised patients (transplant recipients, patients taking steroids chronically, and patients with HIV infection who have a CD4 count < 200 cells/μL) can present with more virulent episodes of diverticulitis, have a higher incidence of perforation and fecal peritonitis, and have a greater likelihood of failure of nonsurgical management.1 Surgical intervention after the first episode of diverticulitis in these patients should therefore be considered.

In 2014, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) recommended the laparoscopic Hartmann procedure (primary resection of the affected segment of colon, with end colostomy, followed by colostomy closure) as the gold standard for the treatment of acute perforated diverticular disease when surgery is required.46

COLONOSCOPY AFTER DIVERTICULITIS

Although endoscopy is to be avoided during acute diverticulitis because of the risk for perforation, it is recommended six to eight weeks after the acute episode has resolved to rule out malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and colitis.1,3 Interestingly, in 2015, Daniels et al compared the colonoscopic detection rate of advanced colonic neoplasia in patients with a first episode of acute diverticulitis and in patients undergoing initial screening for colorectal cancer, and found no significant difference in the detection rate between the two groups.47 The authors concluded that routine colonoscopic follow-up after an episode of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis could be eliminated and that those patients could be screened according to routine guidelines.

Lau et al found a number of cancers and other significant lesions on colonoscopy performed after an episode of acute diverticulitis, with a 2.1% prevalence of colorectal cancer within one year after CT-proven diverticulitis, and an increase in the prevalence of abscess, local perforation, and fistula.48 Their study excluded patients who had had a colonoscopy within one year, however. They therefore recommended performing colonoscopy only for patients who have not had a recent colonoscopic exam. This recommendation is in accord with the most recent AGA and ASCRS guidelines. If a patient has had a recent colonoscopy prior to an acute episode of diverticulitis, the value of repeating the study after the episode resolves is unclear.

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

As this article shows, the spectrum of clinical presentations for diverticulitis is broad, and management most often requires a case-by-case approach. Treatment is dictated by whether disease presentation is uncomplicated or complicated; outpatient management is appropriate for uncomplicated cases in the absence of specific criteria for hospitalization. Recent evidence supports a paradigm shift away from mandatory dietary restriction and routine antibiotic use.

1. Deery SE, Hodin RA. Management of diverticulitis in 2017. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(10):1732-1741.

2. Boermeester M, Humes D, Velmahos G, et al. Contemporary review of risk-stratified management in acute uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis. World J Surg. 2016;40(10):2537-2545.

3. Linzay C, Pandit S. Diverticulitis, acute. [Updated 2017 Nov 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018- Jan.

4. Rezapour M, Ali S, Stollman N. Diverticular disease: an update on pathogenesis and management. Gut Liver. 2018;12(2):125-132.

5. Mayl J, Marchenko M, Frierson E. Management of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis may exclude antibiotic therapy. Cureus. 2017;9(5):e1250.

6. Chung BH, Ha GW, Lee MR, Kim JH. Management of colonic diverticulitis tailored to location and severity: comparison of the right and the left colon. Ann Coloproctol. 2016;32(6):228-233.

7. Hinchey EJ, Schaal PG, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg. 1978;12:85-109.

8. Burkitt DP. Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1971;28(1):3-13.

9. Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rockett HR, et al. A prospective study of dietary fiber types and symptomatic diverticular disease in men. J Nutr. 1998;128(4):714-719.

10. Peery AF, Barrett PR, Park D, et al. A high-fiber diet does not protect against asymptomatic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):266-272.

11. Peery AF, Sandler RS, Ahnen DJ, et al. Constipation and a low-fiber diet are not associated with diverticulosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(12):1622-1627.

12. Strate LL, Keeley BR, Cao Y, et al. Western dietary pattern increases, whereas prudent dietary pattern decreases, risk of incident diverticulitis in a prospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1023-1030.

13. Crowe FL, Balkwill A, Cairns BJ, et al; Million Women Study Collaborators. Source of dietary fibre and diverticular disease incidence: a prospective study of UK women. Gut. 2014;63(9):1450-1456.

14. Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the management of acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterology 2015;149(7):1944-1949.

15. Strate LL, Liu YL, Syngal S, et al. Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA. 2008;300(8):907-914.

16. Hjern F, Wolk A, Håkansson N. Smoking and the risk of diverticular disease in women. Br J Surg. 2011;98(7):997-1002.

17. Humes DJ, Spiller RC. Review article: The pathogenesis and management of acute colonic diverticulitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(4):359-370.

18. Moubax K, Urbain D. Diverticulitis: new insights on the traditional point of view. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2015;78(1):38-48.

19. Morris AM, Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM, Hendren S. Sigmoid diverticulitis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014; 311(3):287-297.

20. Tan JP, Barazanchi AW, Singh PP, et al. Predictors of acute diverticulitis severity: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2016;26:43-52.

21. Strate LL, Liu YL, Huang ES, et al. Use of aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increases risk for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):1427-1433.

22. Nizri E, Spring S, Ben-Yehuda A, et al. C-reactive protein as a marker of complicated diverticulitis in patients on anti-inflammatory medications. Tech Coloproctol. 2014; 18(2):145-149.

23. Kvasnovsky CL, Papagrigoriadis S, Bjarnason I. Increased diverticular complications with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and other medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2014; 16(6):O189-O196.

24. Maguire LH, Song M, Strate LL, et al. Higher serum levels of vitamin D are associated with a reduced risk of diverticulitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(12):1631-1635.

25. Maguire LH, Song M, Strate LL, et al. Association of geographic and seasonal variation with diverticulitis admissions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):74-77.

26. Granlund J, Svensson T, Olén O, et al. The genetic influence on diverticular disease—a twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(9):1103-1107.

27. Strate LL, Erichsen R, Baron JA, et al. Heritability and familial aggregation of diverticular disease: a population-based study of twins and siblings. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(4):736-742.

28. Jamal Talabani A, Lydersen S, Ness-Jensen E, et al. Risk factors of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in a population-based cohort study: The North Trondelag Health Study, Norway. World J Gastroenterol. 2016; 22(48):10663-10672.

29. Horesh N, Wasserberg N, Zbar AP, et al. Changing paradigms in the management of diverticulitis. Int J Surg. 2016(33 pt A):146-150.

30. McSweeney W, Srinath H. Diverticular disease practice points. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46(11):829-832.

31. Wilkins T, Embry K, George R. Diagnosis and management of acute diverticulitis. Am Fam Physician. 2013; 87(9):612-620.

32. van de Wall BJ, Draaisma WA, van der Kaaij RT, et al. The value of inflammation markers and body temperature in acute diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(5):621-626.

33. Kechagias A, Rautio T, Kechagias G, Mäkelä J. The role of C-reactive protein in the prediction of the clinical severity of acute diverticulitis. Am Surg. 2014;80(4):391-395.

34. Bolkenstein HE, van de Wall BJM, Consten ECJ, et al. Risk factors for complicated diverticulitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017; 32(10):1375-1383.

35. Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(3):284-294.

36. van de Wall BJ, Draaisma WA, van Iersel JJ, et al. Dietary restrictions for acute diverticulitis: evidence-based or expert opinion? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(9):1287-1293.

37. Stam MA, Draaisma WA, van de Wall BJ, et al. An unrestricted diet for uncomplicated diverticulitis is safe: results of a prospective diverticulitis diet study. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19(4):372-377.

38. Khan DZ, Kelly ME, O’Reilly J, et al. A national evaluation of the management practices of acute diverticulitis. Surgeon. 2017;15(4):206-210.

39. Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, et al; AVOD Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99(4):532-539.

40. Isacson D, Andreasson K, Nikberg M, et al. No antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: does it work? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(12):1441-1446.

41. Daniels L, Ünlü Ç, de Korte N, et al; Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of observational versus antibiotic treatment for a first episode of CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104(1):52-61.

42. van Dijk S, Rottier SJ, van Geloven AAW, Boermeester MA. Conservative treatment of acute colonic diverticulitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2017;19(11):44.

43. Raskin J, Kamm M, Jamal M, Howden CW. Mesalamine did not prevent recurrent diverticulitis in phase 3 controlled trials. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:793-802.

44. Kahn M, Ali B, Lee W, et al. Mesalamine does not help prevent recurrent acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):579-581.

45. Lahner E, Bellisario C, Hassan C, et al. Probiotics in the treatment of diverticular disease. A systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2016;25(1):79-86.

46. Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(3):284-294.

47. Daniels I, Ünlü Ç, de Wijkerslooth TR, et al. Yield of colonoscopy after recent CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis: a comparative cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(9):2605-2613.

48. Lau KC, Spilsbury K, Farooque Y, et al. Is colonoscopy still mandatory after a CT diagnosis of left-sided diverticulitis: can colorectal cancer be confidently excluded? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(10):1265-1270.

CE/CME No: CR-1808

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the pathophysiology of diverticulitis.

• Describe the spectrum of clinical presentations of diverticulitis.

• Understand the diagnostic evaluation of diverticulitis.

• Differentiate the management of uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis.

FACULTY

Priscilla Marsicovetere is Assistant Professor of Medical Education and Surgery, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, and Program Director for the Franklin Pierece University, PA Program, Lebanon, New Hampshire. She practices with Emergency Services of New England, Springfield Hospital, Springfield, Vermont.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through July 31, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

Treatment of this common complication of diverticular disease is predicated on whether the presentation signals uncomplicated or complicated disease. While some uncomplicated cases require hospitalization, many are amenable to primary care outpatient, and often conservative, management. The longstanding practice of antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated cases is now considered a selective, rather than a routine, option.

Diverticular disease is one of the most common conditions in the Western world and one of the most frequent indications for gastrointestinal-related hospitalization.1 It is among the 10 most common diagnoses in patients presenting to the clinic or emergency department with acute abdominal pain.2 Prevalence increases with age: Up to 60% of persons older than 60 are affected.3 The most common complication of diverticular disease is diverticulitis, which occurs in up to 25% of patients.4

The spectrum of clinical presentations of diverticular disease ranges from mild, uncomplicated disease that can be treated in the outpatient setting to complicated disease with sepsis and possible emergent surgical intervention. The traditional approach to diverticulitis has been management with antibiotics and likely sigmoid colectomy, but recent studies support a paradigm shift toward more conservative, nonsurgical treatment.

This article highlights current trends in diagnosis and management of acute diverticulitis.

DEFINITION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Diverticular disease is marked by sac-like outpouchings, called diverticula, that form at structurally weak points of the colon wall, predominantly in the descending and sigmoid colon.5 The prevalence of diverticular disease is increasing globally, affecting more than 10% of people older than 40, as many as 60% of those older than 60, and more than 70% of people older than 80.1,3 The mean age for hospital admission for acute diverticulitis is 63.3

Worldwide, males and females are affected equally.3 In Western society, the presence of diverticula, also called diverticulosis, is more often left-sided; right-sided disease is more prevalent in Asia.3,5

The most common complication of diverticular disease is diverticulitis—inflammation of a diverticulum—which affects 10% to 25% of patients with diverticular disease during their lifetime.4,5 Diverticulitis can be classified as uncomplicated (characterized by colonic wall thickening or pericolic inflammatory changes) or complicated (characterized by abscesses, fistulae, obstruction, or localized or free perforations).1,6 As many as 25% of diverticulitis cases are considered complicated.4,5 The severity of diverticulitis is commonly graded using the Hinchey Classification (Table 1).1,7

Continue to: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Diverticula tend to occur in areas where the colonic wall is weak: namely, between the mesenteric and antimesenteric taeniae, where the vasa recta penetrate the muscle—points of entry of blood vessels through the colonic wall.1,4 The exact pathogenesis of diverticular disease is not completely understood but is thought to be multifactorial. Microscopic studies have shown muscular atrophy at the sites of diverticula, making them more susceptible to mucosal herniation in the setting of increased intraluminal pressure.1 Additional potential contributing factors include alterations in colonic microbiota, muscular dysfunction or dysmotility, lifestyle, and genetics.

Diverticulitis is the result of microscopic and macroscopic perforation of diverticula. Historically, the perforations were thought to result from obstruction of a diverticulum by a fecalith, leading to increased pressure within the outpouching, followed by perforation.3 Such obstruction is now thought to be rare. A more recent theory suggests that increased intraluminal pressure is due to inspissated food particles that lead to erosion of the diverticular wall, causing focal inflammation and necrosis and resulting in perforation.3 Microperforations can easily be contained by surrounding mesenteric fat; however, progression to abscess, fistulization, or intestinal obstruction can occur. Frank bowel wall perforation is not contained by mesenteric fat and can lead quickly to peritonitis and death if not treated emergently.

RISK FACTORS

Dietary fiber

In 1971, Burkitt was the first to posit that diverticular disease developed due to small quantities of fiber in the diet that led to increased intracolonic pressures.8 His theory was based on the observation that residents of several African countries, who ate a high-fiber diet, had a low incidence of diverticular disease. Burkitt hypothesized that this was due to shorter colonic transit time induced by high dietary fiber.

Several studies conducted since Burkitt made his observations have examined the association of dietary fiber and diverticular disease, with conflicting results. In 1998, Aldoori et al found that a low-fiber diet increases the incidence of symptomatic diverticular disease.9 However, in 2012, a large cohort study of patients undergoing colonoscopy found that those who reported the highest fiber intake were at highest risk for diverticulosis.10 In 2013, Peery et al examined the relationship among bowel habits, dietary fiber, and asymptomatic diverticulosis and found that less-frequent bowel movements and hard stools were associated with a decreased risk for diverticulosis.11 In 2017, a prospective cohort study of nearly 50,000 men without a known history of diverticulosis showed that diets high in red meat were associated with a higher incidence of diverticulitis over nearly three decades of follow-up, whereas a diet high in fiber was associated with a decreased incidence of diverticulitis.12

Although no definitive association has been found between dietary fiber intake and risk for diverticulosis, some studies have demonstrated an association between dietary fiber and diverticular complications. In 2014, Crowe et al found that consumption of a high-fiber diet was associated with a lower risk for hospital admission and death from diverticular disease.13 Recent guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) on diverticulitis recommend high dietary fiber intake in patients with a history of acute diverticulitis.14 However, no study has shown a reversal of the process or a reduction in the number of episodes of diverticulitis after adoption of a high-fiber diet.

Continue to: Historically, patients with diverticulitis...

Historically, patients with diverticulitis were advised to avoid eating nuts, corn, popcorn, and seeds to reduce the risk for complications. But studies have found no support for this caution. In a 2008 large, prospective study of men without known diverticular disease, the researchers found no association between nut, corn, or popcorn ingestion and diverticulitis; in fact, increased nut intake was specifically associated with a lower risk for diverticulitis.15

Smoking

Smoking has been linked to diverticulitis and has been associated with a threefold risk for complications, including severe diverticulitis.16,17 An increased risk for recurrent episodes has also been found in smokers following surgical intervention.17

Medications

NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and opioids have been associated with an increased risk for perforated diverticulitis.18,19 A significant association has been found between NSAID use and severity of diverticulitis, including perforation; one study reported a relative risk of 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 10.5 to 1.47) for diverticulitis with regular use of aspirin (≥ 2x/wk).20,21

More frequent steroid use has been found in patients with complicated diverticulitis, compared to patients with uncomplicated disease (7.3% vs 3.3%; P = .015).22 A systematic review of five studies comparing patients with and without steroid use showed significantly higher odds of diverticular perforation in patients taking a steroid.23 Pooled data showed significantly increased odds of perforation and abscess formation with use of an NSAID (odds ratio [OR], 2.49), steroid (OR, 9.08), or opioid (OR, 2.52).22

Continue to: Vitamin D

Vitamin D

In a 2013 retrospective cohort study of 9,116 patients with uncomplicated diverticulosis and 922 patients who developed diverticulitis that required hospitalization, Maguire et al examined the association of prediagnostic serum levels of vitamin D and diverticulitis.24 Among patients with diverticulosis, higher prediagnostic levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D were significantly associated with a lower risk for diverticulitis—indicating that vitamin D deficiency could be involved in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis.

The association between diverticulitis and vitamin D levels was supported by an additional study in 2015, in which the authors investigated the association between ultraviolet (UV) light and diverticulitis.25 They identified nonelective diverticulitis admissions in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database and linked hospital locations to geographic UV data. They examined UV exposure in relation to risk for admission for diverticulitis and found that, compared with high-UV (UV4) areas, low-UV (UV1) areas had a higher rate of diverticulitis (751.8/100,000 admissions, compared with 668.1/100,000 admissions, respectively [P < .001]), diverticular abscess (12.0% compared with 9.7% [P < .001]), and colectomy (13.5% compared with 11.5% [P < .001]). They also observed significant seasonal variation, with a lower rate of diverticulitis in winter (645/100,000 admissions) compared with summer (748/100,000 admissions [P < .001]). Because UV exposure largely determines vitamin D status, these findings are thought to support a role for vitamin D in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis.

Genetics

Two studies found an association between genetics and diverticular disease. A 2012 study using The Swedish Twin Registry found that if one twin is affected with the disease, the odds that the other will be affected was 7.15 in monozygotic (identical) twins and 3.20 in dizygotic (fraternal) twins.26 A 2013 Danish twin study found a relative risk of 2.92 in twin siblings compared to the general population.27 Both studies estimated the genetic contribution to diverticular disease to be 40% to 50%.26,27

Obesity

Several large prospective studies have shown a positive association between high BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio and risk for diverticulitis.4 A BMI > 30 was found to increase the relative risk of acute diverticulitis by 1.78, compared with a normal BMI.17 In a large, prospective, population-based cohort study in 2016, Jamal Talabani et al found that obese persons had twice the risk for admission for acute colonic diverticulitis than normal-weight persons did.28 Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio were also independently associated with risk for diverticulitis. The pathophysiology of the associations is not clearly understood but may involve pro-inflammatory changes of adipose tissue, which secrete cytokines that promote an inflammatory response, and changes in gut microbiota.4,12

Physical activity

Data on the association of physical activity and diverticulitis is inconsistent. Some studies have found as much as a 25% decrease in the risk for diverticulitis with increased physical activity; more recent studies (2013 and 2016), on the other hand, found no association between diverticulosis and physical activity.11,17,19,28

Continue to: CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of diverticulitis typically depends on the severity of inflammation and the presence (or absence) of complications. The most common presenting symptom is left lower-quadrant abdominal pain, which occurs in approximately 70% of cases and lasts for longer than 24 hours.29 Fever (usually < 102°F), leukocytosis, nausea, vomiting, and changes in bowel function may also be present.1,30,31 Approximately 50% of patients report constipation in diverticular disease; 20% to 35% report diarrhea.5

Patients may also report dysuria, secondary to irritation of the bladder by an inflamed segment of colon.3,17 Patients may report fecaluria, pneumaturia, or pyuria, which indicate a colovesical fistula.1 Passage of feces or flatus through the vagina indicates a colovaginal fistula.

The differential diagnosis of diverticulitis is listed in Table 2.17

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination in diverticulitis will almost always elicit tenderness to palpation over the area of inflammation, typically in the left lower quadrant. This is due to irritation of the peritoneum.3 A palpable mass may be present in as many as 20% of patients if an abscess is present. Bowel sounds may be hypoactive or hyperactive if there is a bowel obstruction.17 In cases of frank bowel-wall perforation, patients can present with peritoneal signs of rigidity, guarding, and rebound tenderness.3,31 Tachycardia, hypotension, and shock are rare but possible findings. Digital rectal examination may reveal tenderness or a mass if a pelvic abscess is present.17,31

DIAGNOSTICS

The diagnosis of acute diverticulitis can often be made clinically, based on the history and physical examination. Because clinical diagnosis can be inaccurate in as many as 68% of cases, however, laboratory testing and imaging play an important role in diagnosis.3

Continue to: Clinical laboratory studies

Clinical laboratory studies

Because leukocytosis is present in approximately one-half of patients with diverticulitis, a complete blood count (CBC) should be obtained; that recommendation notwithstanding, approximately one-half of patients with diverticulitis have a normal white blood cell count.29,30 A urine test of human chorionic gonadotropin should be ordered to exclude pregnancy in all premenopausal and perimenopausal women, particularly if antibiotics, imaging, or surgery are being considered.31 Urinalysis can assess for urinary tract infection.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the utility of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the workup of acute diverticulitis. In general, patients with a complicated episode will present with a significantly higher CRP level than that of uncomplicated disease.32 Kechagias et al found that the CRP level at initial evaluation may be helpful in predicting the clinical severity of the attack. A CRP level > 170 mg/L has been found to have a greater probability of severe disease, warranting CT and referral for hospitalization.33 A low CRP level was more likely to herald a mild course of disease that is amenable to outpatient antibiotic management or supportive care. This finding is consistent with previous reports of the association between CRP levels of 90 to 200 mg/L and the severity of diverticulitis.32,34

Imaging

Abdominopelvic CT with intravenous (IV) contrast. This imaging study is the gold standard diagnostic tool for diverticulitis, with sensitivity as high as 97%.3 CT can distinguish diverticulitis from other conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (based on a history of symptoms and the absence of CT findings), gastroenteritis, and gynecologic disease. It can also distinguish between uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis and therefore guide therapeutic interventions, such as percutaneous drainage of an intra-abdominal abscess. CT findings associated with uncomplicated diverticulitis include colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fluid and inflammatory changes, such as fat stranding. CT findings associated with complicated disease include abscess (paracolonic or pelvic), peritonitis (purulent or feculent), phlegmon, perforation, fistula, and obstruction.1,3

Ultrasonography (US) can also be used in the assessment of diverticulitis, although it has lower sensitivity (approximately 61% to 84%) than CT and is inferior to CT for showing the extent of large abscesses or free air.3,18,30 A typical US finding in acute diverticulitis is a thickened loop of bowel with a target-like appearance.17 Findings are highly operator-dependent, however, and accuracy is diminished in obese patients. US may be a good option for pregnant women to avoid ionizing radiation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another option for imaging in diverticulitis but is not routinely recommended. It provides excellent soft-tissue detail and does not deliver ionizing radiation, but it is not as sensitive as CT for identifying free air.18,31 Furthermore, MRI requires prolonged examination time, which may not be tolerated by acutely ill patients, and is not an option for patients with certain types of surgical clips, metallic fragments, or a cardiac pacemaker.

Continue to: Abdominal radiography...

Abdominal radiography is useful to show free air, which would indicate perforation, and to show nonspecific abnormalities, such as bowel-gas patterns.31

MANAGEMENT

For decades, patients with diverticulitis were managed with antibiotics to cover colonic flora; many underwent urgent or emergent surgery to remove the affected segment of colon. Over the years, however, the treatment paradigm has shifted from such invasive management toward a nonsurgical approach—often, with equivalent or superior outcomes. More and more, management of diverticulitis is dictated by disease presentation: namely, whether disease is uncomplicated or complicated.1

Current guidelines recommend hospitalization, with possible surgical intervention, in complicated disease (free perforation, large abscesses, fistula, obstruction, stricture) and in patients who cannot tolerate oral hydration, who have a relevant comorbidity, or who do not have adequate support at home.35 Uncomplicated cases may also require hospitalization if certain criteria for admission are met: immunosuppression, severe or persistent abdominal pain, inability to tolerate oral intake, and significant comorbidity.5

Absent these criteria, outpatient management of uncomplicated diverticulitis is appropriate. After the treatment setting is determined, choice of intervention and length of treatment should be addressed.

Nonpharmacotherapeutic management

Dietary restrictions, from a full liquid diet to complete bowel rest, have been recommended for the management of acute diverticulitis. This recommendation is not supported by the literature, however. At least two studies have shown no association between an unrestricted diet and an increase in diverticular complications. In a 2013 retrospective cohort study, no increase in diverticular perforation or abscess was found with a diet of solid food compared to a liquid diet, a clear liquid diet, or no food by mouth.36 In a more recent (2017) prospective cohort study of 86 patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis, all of whom were on an unrestricted diet, only 8% developed complications.37

Continue to: There is no high-quality evidence for...

There is no high-quality evidence for instituting dietary restrictions in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. As such, permitting oral intake as tolerated is a reasonable option.

Pharmacotherapy

Antibiotics have long been the cornerstone of pharmacotherapy for acute diverticulitis, covering gram-negative rods and anaerobes. The rationale for such management is the long-held belief that diverticulitis is caused by an infectious process.38 Common outpatient regimens include

- Ciprofloxacin (500 mg every 12 h) plus metronidazole (500 mg every 8 h)

- Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (1 double-strength tablet every 12 h) plus metronidazole (500 mg every 8 h)

- Amoxicillin (875 mg)–clavulanate (1 tablet every 8 h) or extended-release amoxicillin–clavulanate (2 tablets every 12 h)

- Moxifloxacin (400 mg/d; for patients who cannot tolerate metronidazole or ß-lactam antibiotics).

Providers should always consult their local antibiogram to avoid prescribing antibiotics to which bacterial resistance exceeds 10%.

Despite widespread use of antibiotics for diverticulitis, multiple studies in recent years have shown no benefit to their use for uncomplicated cases. In 2012, Chabok et al investigated the need for antibiotic therapy to treat acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and found no statistically significant difference in outcome among patients treated with antibiotics and those managed conservatively.39 In 2014, Isacson et al performed a retrospective population-based cohort study to assess the applicability of a selective “no antibiotic” policy and its consequences in terms of complications and recurrence; the authors found that withholding antibiotics was safe and did not result in a higher complication or recurrence rate.40 Furthermore, in a 2017 multicenter study, Daniels et al conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing observation and antibiotic treatment for a first episode of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis in 528 patients and found no prolongation of recovery time, no increased rate of complications, and no need for surgical intervention in patients who were not treated with antibiotics.41

These studies are in agreement with the most recent AGA guidelines, which recommend selective, rather than routine, use of antibiotics for acute diverticulitis.14 This shift in approach may be due, in part, to a change in understanding of the etiology of the disease—from an infectious process to more of an inflammatory process.38

Continue to: For patients who require inpatient management of diverticulitis...

For patients who require inpatient management of diverticulitis, treatment typically involves IV antibiotics, fluids, and analgesics. Surgical treatment may be appropriate (see “Surgical treatment”).

Other agents used to manage diverticulitis include three that lack either strong or any data at all showing efficacy. The most recent AGA guidelines recommend against their use for this indication14:

Rifaximin. Two recent observational cohort studies, one from 2013 and the other from 2017, compared this poorly absorbed oral antibiotic with mesalamine to placebo or no treatment at all.42 Neither provided evidence that rifaximin treats or prevents diverticulitis.

Mesalamine. This anti-inflammatory has also been studied to prevent recurrence of diverticulitis. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of 1,182 patients, Raskin et al found that mesalamine did not reduce the rate of recurrence of diverticulitis, time to recurrence, or the number of patients requiring surgery.43 This conclusion was reiterated by a 2016 meta-analysis that found no evidence to support use of mesalamine in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence.44

Probiotics. Despite multiple studies undertaken to assess the efficacy of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of diverticular disease, strong data supporting their use are sparse. In 2016, Lahner et al examined 11 studies in which various probiotics were used to treat diverticular disease and found that, although there was a weak positive trend in the reduction and remission of abdominal symptoms, the evidence was not strong enough to recommend their routine use in managing the disease.45

Continue to: Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment

Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis can be treated nonsurgically in nearly all patients, regardless of whether treatment occurs in the inpatient or outpatient setting. For complicated disease, however, approximately 15% to 25% of patients require surgery. The main indication for emergent or urgent surgical intervention is colonic perforation, which can lead to acute peritonitis, sepsis, and associated morbidity and mortality.29

The decision to perform elective surgery should be made case by case, not routinely—such as after a recurrent episode of diverticulitis, when there has been a complication, or in young patients (< 50 years).1,11 Immunocompromised patients (transplant recipients, patients taking steroids chronically, and patients with HIV infection who have a CD4 count < 200 cells/μL) can present with more virulent episodes of diverticulitis, have a higher incidence of perforation and fecal peritonitis, and have a greater likelihood of failure of nonsurgical management.1 Surgical intervention after the first episode of diverticulitis in these patients should therefore be considered.

In 2014, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) recommended the laparoscopic Hartmann procedure (primary resection of the affected segment of colon, with end colostomy, followed by colostomy closure) as the gold standard for the treatment of acute perforated diverticular disease when surgery is required.46

COLONOSCOPY AFTER DIVERTICULITIS

Although endoscopy is to be avoided during acute diverticulitis because of the risk for perforation, it is recommended six to eight weeks after the acute episode has resolved to rule out malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and colitis.1,3 Interestingly, in 2015, Daniels et al compared the colonoscopic detection rate of advanced colonic neoplasia in patients with a first episode of acute diverticulitis and in patients undergoing initial screening for colorectal cancer, and found no significant difference in the detection rate between the two groups.47 The authors concluded that routine colonoscopic follow-up after an episode of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis could be eliminated and that those patients could be screened according to routine guidelines.

Lau et al found a number of cancers and other significant lesions on colonoscopy performed after an episode of acute diverticulitis, with a 2.1% prevalence of colorectal cancer within one year after CT-proven diverticulitis, and an increase in the prevalence of abscess, local perforation, and fistula.48 Their study excluded patients who had had a colonoscopy within one year, however. They therefore recommended performing colonoscopy only for patients who have not had a recent colonoscopic exam. This recommendation is in accord with the most recent AGA and ASCRS guidelines. If a patient has had a recent colonoscopy prior to an acute episode of diverticulitis, the value of repeating the study after the episode resolves is unclear.

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

As this article shows, the spectrum of clinical presentations for diverticulitis is broad, and management most often requires a case-by-case approach. Treatment is dictated by whether disease presentation is uncomplicated or complicated; outpatient management is appropriate for uncomplicated cases in the absence of specific criteria for hospitalization. Recent evidence supports a paradigm shift away from mandatory dietary restriction and routine antibiotic use.

CE/CME No: CR-1808

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the pathophysiology of diverticulitis.

• Describe the spectrum of clinical presentations of diverticulitis.

• Understand the diagnostic evaluation of diverticulitis.

• Differentiate the management of uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis.

FACULTY

Priscilla Marsicovetere is Assistant Professor of Medical Education and Surgery, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, and Program Director for the Franklin Pierece University, PA Program, Lebanon, New Hampshire. She practices with Emergency Services of New England, Springfield Hospital, Springfield, Vermont.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through July 31, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

Treatment of this common complication of diverticular disease is predicated on whether the presentation signals uncomplicated or complicated disease. While some uncomplicated cases require hospitalization, many are amenable to primary care outpatient, and often conservative, management. The longstanding practice of antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated cases is now considered a selective, rather than a routine, option.

Diverticular disease is one of the most common conditions in the Western world and one of the most frequent indications for gastrointestinal-related hospitalization.1 It is among the 10 most common diagnoses in patients presenting to the clinic or emergency department with acute abdominal pain.2 Prevalence increases with age: Up to 60% of persons older than 60 are affected.3 The most common complication of diverticular disease is diverticulitis, which occurs in up to 25% of patients.4

The spectrum of clinical presentations of diverticular disease ranges from mild, uncomplicated disease that can be treated in the outpatient setting to complicated disease with sepsis and possible emergent surgical intervention. The traditional approach to diverticulitis has been management with antibiotics and likely sigmoid colectomy, but recent studies support a paradigm shift toward more conservative, nonsurgical treatment.

This article highlights current trends in diagnosis and management of acute diverticulitis.

DEFINITION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Diverticular disease is marked by sac-like outpouchings, called diverticula, that form at structurally weak points of the colon wall, predominantly in the descending and sigmoid colon.5 The prevalence of diverticular disease is increasing globally, affecting more than 10% of people older than 40, as many as 60% of those older than 60, and more than 70% of people older than 80.1,3 The mean age for hospital admission for acute diverticulitis is 63.3

Worldwide, males and females are affected equally.3 In Western society, the presence of diverticula, also called diverticulosis, is more often left-sided; right-sided disease is more prevalent in Asia.3,5

The most common complication of diverticular disease is diverticulitis—inflammation of a diverticulum—which affects 10% to 25% of patients with diverticular disease during their lifetime.4,5 Diverticulitis can be classified as uncomplicated (characterized by colonic wall thickening or pericolic inflammatory changes) or complicated (characterized by abscesses, fistulae, obstruction, or localized or free perforations).1,6 As many as 25% of diverticulitis cases are considered complicated.4,5 The severity of diverticulitis is commonly graded using the Hinchey Classification (Table 1).1,7

Continue to: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Diverticula tend to occur in areas where the colonic wall is weak: namely, between the mesenteric and antimesenteric taeniae, where the vasa recta penetrate the muscle—points of entry of blood vessels through the colonic wall.1,4 The exact pathogenesis of diverticular disease is not completely understood but is thought to be multifactorial. Microscopic studies have shown muscular atrophy at the sites of diverticula, making them more susceptible to mucosal herniation in the setting of increased intraluminal pressure.1 Additional potential contributing factors include alterations in colonic microbiota, muscular dysfunction or dysmotility, lifestyle, and genetics.

Diverticulitis is the result of microscopic and macroscopic perforation of diverticula. Historically, the perforations were thought to result from obstruction of a diverticulum by a fecalith, leading to increased pressure within the outpouching, followed by perforation.3 Such obstruction is now thought to be rare. A more recent theory suggests that increased intraluminal pressure is due to inspissated food particles that lead to erosion of the diverticular wall, causing focal inflammation and necrosis and resulting in perforation.3 Microperforations can easily be contained by surrounding mesenteric fat; however, progression to abscess, fistulization, or intestinal obstruction can occur. Frank bowel wall perforation is not contained by mesenteric fat and can lead quickly to peritonitis and death if not treated emergently.

RISK FACTORS

Dietary fiber

In 1971, Burkitt was the first to posit that diverticular disease developed due to small quantities of fiber in the diet that led to increased intracolonic pressures.8 His theory was based on the observation that residents of several African countries, who ate a high-fiber diet, had a low incidence of diverticular disease. Burkitt hypothesized that this was due to shorter colonic transit time induced by high dietary fiber.

Several studies conducted since Burkitt made his observations have examined the association of dietary fiber and diverticular disease, with conflicting results. In 1998, Aldoori et al found that a low-fiber diet increases the incidence of symptomatic diverticular disease.9 However, in 2012, a large cohort study of patients undergoing colonoscopy found that those who reported the highest fiber intake were at highest risk for diverticulosis.10 In 2013, Peery et al examined the relationship among bowel habits, dietary fiber, and asymptomatic diverticulosis and found that less-frequent bowel movements and hard stools were associated with a decreased risk for diverticulosis.11 In 2017, a prospective cohort study of nearly 50,000 men without a known history of diverticulosis showed that diets high in red meat were associated with a higher incidence of diverticulitis over nearly three decades of follow-up, whereas a diet high in fiber was associated with a decreased incidence of diverticulitis.12

Although no definitive association has been found between dietary fiber intake and risk for diverticulosis, some studies have demonstrated an association between dietary fiber and diverticular complications. In 2014, Crowe et al found that consumption of a high-fiber diet was associated with a lower risk for hospital admission and death from diverticular disease.13 Recent guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) on diverticulitis recommend high dietary fiber intake in patients with a history of acute diverticulitis.14 However, no study has shown a reversal of the process or a reduction in the number of episodes of diverticulitis after adoption of a high-fiber diet.

Continue to: Historically, patients with diverticulitis...

Historically, patients with diverticulitis were advised to avoid eating nuts, corn, popcorn, and seeds to reduce the risk for complications. But studies have found no support for this caution. In a 2008 large, prospective study of men without known diverticular disease, the researchers found no association between nut, corn, or popcorn ingestion and diverticulitis; in fact, increased nut intake was specifically associated with a lower risk for diverticulitis.15

Smoking

Smoking has been linked to diverticulitis and has been associated with a threefold risk for complications, including severe diverticulitis.16,17 An increased risk for recurrent episodes has also been found in smokers following surgical intervention.17

Medications

NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and opioids have been associated with an increased risk for perforated diverticulitis.18,19 A significant association has been found between NSAID use and severity of diverticulitis, including perforation; one study reported a relative risk of 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 10.5 to 1.47) for diverticulitis with regular use of aspirin (≥ 2x/wk).20,21

More frequent steroid use has been found in patients with complicated diverticulitis, compared to patients with uncomplicated disease (7.3% vs 3.3%; P = .015).22 A systematic review of five studies comparing patients with and without steroid use showed significantly higher odds of diverticular perforation in patients taking a steroid.23 Pooled data showed significantly increased odds of perforation and abscess formation with use of an NSAID (odds ratio [OR], 2.49), steroid (OR, 9.08), or opioid (OR, 2.52).22

Continue to: Vitamin D

Vitamin D

In a 2013 retrospective cohort study of 9,116 patients with uncomplicated diverticulosis and 922 patients who developed diverticulitis that required hospitalization, Maguire et al examined the association of prediagnostic serum levels of vitamin D and diverticulitis.24 Among patients with diverticulosis, higher prediagnostic levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D were significantly associated with a lower risk for diverticulitis—indicating that vitamin D deficiency could be involved in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis.

The association between diverticulitis and vitamin D levels was supported by an additional study in 2015, in which the authors investigated the association between ultraviolet (UV) light and diverticulitis.25 They identified nonelective diverticulitis admissions in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database and linked hospital locations to geographic UV data. They examined UV exposure in relation to risk for admission for diverticulitis and found that, compared with high-UV (UV4) areas, low-UV (UV1) areas had a higher rate of diverticulitis (751.8/100,000 admissions, compared with 668.1/100,000 admissions, respectively [P < .001]), diverticular abscess (12.0% compared with 9.7% [P < .001]), and colectomy (13.5% compared with 11.5% [P < .001]). They also observed significant seasonal variation, with a lower rate of diverticulitis in winter (645/100,000 admissions) compared with summer (748/100,000 admissions [P < .001]). Because UV exposure largely determines vitamin D status, these findings are thought to support a role for vitamin D in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis.

Genetics

Two studies found an association between genetics and diverticular disease. A 2012 study using The Swedish Twin Registry found that if one twin is affected with the disease, the odds that the other will be affected was 7.15 in monozygotic (identical) twins and 3.20 in dizygotic (fraternal) twins.26 A 2013 Danish twin study found a relative risk of 2.92 in twin siblings compared to the general population.27 Both studies estimated the genetic contribution to diverticular disease to be 40% to 50%.26,27

Obesity

Several large prospective studies have shown a positive association between high BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio and risk for diverticulitis.4 A BMI > 30 was found to increase the relative risk of acute diverticulitis by 1.78, compared with a normal BMI.17 In a large, prospective, population-based cohort study in 2016, Jamal Talabani et al found that obese persons had twice the risk for admission for acute colonic diverticulitis than normal-weight persons did.28 Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio were also independently associated with risk for diverticulitis. The pathophysiology of the associations is not clearly understood but may involve pro-inflammatory changes of adipose tissue, which secrete cytokines that promote an inflammatory response, and changes in gut microbiota.4,12

Physical activity

Data on the association of physical activity and diverticulitis is inconsistent. Some studies have found as much as a 25% decrease in the risk for diverticulitis with increased physical activity; more recent studies (2013 and 2016), on the other hand, found no association between diverticulosis and physical activity.11,17,19,28

Continue to: CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of diverticulitis typically depends on the severity of inflammation and the presence (or absence) of complications. The most common presenting symptom is left lower-quadrant abdominal pain, which occurs in approximately 70% of cases and lasts for longer than 24 hours.29 Fever (usually < 102°F), leukocytosis, nausea, vomiting, and changes in bowel function may also be present.1,30,31 Approximately 50% of patients report constipation in diverticular disease; 20% to 35% report diarrhea.5

Patients may also report dysuria, secondary to irritation of the bladder by an inflamed segment of colon.3,17 Patients may report fecaluria, pneumaturia, or pyuria, which indicate a colovesical fistula.1 Passage of feces or flatus through the vagina indicates a colovaginal fistula.

The differential diagnosis of diverticulitis is listed in Table 2.17

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination in diverticulitis will almost always elicit tenderness to palpation over the area of inflammation, typically in the left lower quadrant. This is due to irritation of the peritoneum.3 A palpable mass may be present in as many as 20% of patients if an abscess is present. Bowel sounds may be hypoactive or hyperactive if there is a bowel obstruction.17 In cases of frank bowel-wall perforation, patients can present with peritoneal signs of rigidity, guarding, and rebound tenderness.3,31 Tachycardia, hypotension, and shock are rare but possible findings. Digital rectal examination may reveal tenderness or a mass if a pelvic abscess is present.17,31

DIAGNOSTICS