User login

Robotic-Assisted Knee Arthroplasty: An Overview

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are 2 reliable treatment options for patients with primary osteoarthritis. Recently published systematic reviews of cohort studies have shown that 10-year survivorship of medial and lateral UKA is 92% and 91%, respectively,1 while 10-year survivorship of TKA in cohort studies is 95%.2 National and annual registries show a similar trend, although the reported survivorship is lower.1,3-7

In order to improve these survivorship rates, the surgical variables that can intraoperatively be controlled by the orthopedic surgeon have been evaluated. These variables include lower leg alignment, soft tissue balance, joint line maintenance, and alignment, size, and fixation of the tibial and femoral component. Several studies have shown that tight control of lower leg alignment,8-14 balancing of the soft tissues,15-19 joint line maintenance,20-23 component alignment,24-28 component size,29-34 and component fixation35-40 can improve the outcomes of UKA and TKA. As a result, over the past 2 decades, several computer-assisted surgery systems have been developed with the goal of more accurate and reliable control of these factors, and thus improved outcomes of knee arthroplasty.

These systems differ with regard to the number and type of variables they control. Computer navigation systems aim to control one or more of these surgical variables, and several meta-analyses have shown that these systems, when compared to conventional surgery, improve mechanical axis accuracy, decrease the risk for mechanical axis outliers, and improve component positioning in TKA41-49 and UKA surgery.50,51 Interestingly, however, meta-analyses have failed to show the expected superiority in clinical outcomes following computer navigation compared to conventional knee arthroplasty.48,52-55 Furthermore, authors have shown that, despite the fact that computer-navigated surgery increases the accuracy of mechanical alignment and surgical cutting, there is still room for improvement.56 As a consequence, robotic-assisted systems have been developed.

Similar to computer navigation, these robotic-assisted systems aim to control the surgical variables; in addition, they aim to improve the surgical precision of the procedure. Interestingly, 2 recent studies have shown that robotic-assisted systems are superior to computer navigation systems with regard to less cutting time and less resection deviations in coronal and sagittal plane in a cadaveric study,57 and shorter total surgery time, more accurate mechanical axis, and shorter hospital stay in a clinical study.58 Although these results are promising, the exact role of robotic surgery in knee arthroplasty remains unclear. In this review, we aim to report the current state of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty by discussing (1) the different robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty systems that are available for UKA and TKA surgery, (2) studies that assessed the role of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty in controlling the aforementioned surgical variables, (3) cadaveric and clinical comparative studies that compared how accurate robotic-assisted and conventional knee surgery control these surgical variables, and (4) studies that assessed the cost-effectiveness of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty surgery.

Robotic-Assisted Knee Arthroplasty Systems

Several systems have been developed over the years for knee arthroplasty, and these are usually defined as active, semi-active, or passive.59 Active systems are capable of performing tasks or processes autonomously under the watchful eye of the surgeon, while passive systems do not perform actions independently but provide the surgeon with information. In semi-active systems, the surgical action is physically constrained in order to follow a predefined strategy.

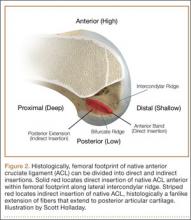

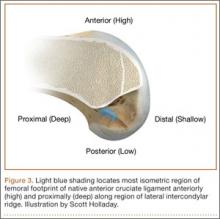

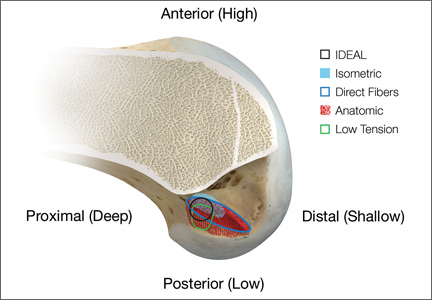

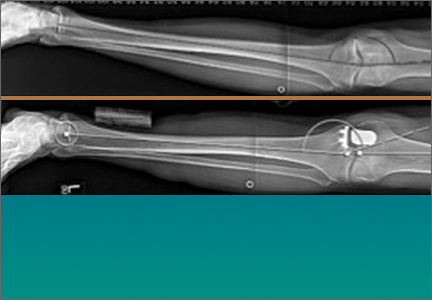

In the United States, 3 robotic systems are FDA-approved for knee arthroplasty. The Stryker/Mako haptic guided robot (Mako Surgical Corp.) was introduced in 2005 and has been used for over 50,000 UKA procedures (Figure 1). There are nearly 300 robotic systems used nationally, as it has 20% of the market share for UKA in the United States. The Mako system is a semi-active tactile robotic system that requires preoperative imaging, after which a preoperative planning is performed. Intraoperatively, the robotic arm is under direct surgeon control and gives real-time tactile feedback during the procedure (Figure 2).

Furthermore, the surgeon can intraoperatively virtually adjust component positioning and alignment and move the knee through the range of motion, after which the system can provide information on alignment, component position, and balance of the soft tissue (eg, if the knee is overtight or lax through the flexion-arch).60 This system has a burr that resects the bone and when the surgeon directs the burr outside the preplanned area, the burr stops and prevents unnecessary and unwanted resections (Figure 3).

The Navio Precision Free-Hand Sculptor (PFS) system (Blue Belt Technologies) has been used for 1500 UKA procedures, with 50 robots in use in the United States (Figure 4). This system is an image-free semi-active robotic system and has the same characteristics as the aforementioned Mako system.61 Finally, the OmniBotic robotic system (Omnilife Science) has been released for TKA and has been used for over 7300 procedures (Figure 5). This system has an automated cutting-guide technique in which the surgeon designs a virtual plan on the computer system. After this, the cutting-guides are placed by the robotic system at the planned location for all 5 femoral cuts (ie, distal, anterior chamfer, anterior, posterior chamfer, and posterior) and the surgeon then makes the final cuts.57,62

Three robotic systems for knee arthroplasty surgery have been used in Europe. The Caspar system (URS Ortho) is an active robotic system in which a computed tomography (CT) scan is performed preoperatively, after which a virtual implantation is performed on the screen. The surgeon can then obtain information on lower leg alignment, gap balancing, and component positioning, and after an operative plan is made, the surgical resections are performed by the robot. Reflective markers are attached to the leg and all robotic movements are monitored using an infrared camera system. Any undesired motion will be detected by this camera system and will stop all movements.63 A second and more frequently reported system in the literature is the active Robodoc surgical system (Curexo Technology Corporation). This system is designed for TKA and total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgery. Although initial studies reported a high incidence of system-related complications in THA,64 the use of this system for TKA has frequently been reported in the literature.56,63,65-69 A third robotic system that has been used in Europe is the Acrobot surgical system (Acrobot Company Ltd), which is an image-based semi-active robotic system70 used for both UKA and TKA surgery.70,71

Accuracy of Controlling Surgical Variables in Robotic-Assisted Knee Arthroplasty

Several studies have assessed the accuracy of robotic-assisted surgery in UKA surgery with regard to control of the aforementioned surgical variables. Pearle and colleagues72 assessed the mechanical axis accuracy of the Mako system in 10 patients undergoing medial UKA robotic-assisted surgery. They reported that the intraoperative registration lasted 7.5 minutes and the duration of time needed for robotic-assisted burring was 34.8 minutes. They compared the actual postoperative alignment at 6 weeks follow-up with the planned lower leg alignment and found that all measurements were within 1.6° of the planned lower leg alignment. Dunbar and colleagues73 assessed the accuracy of component positioning of the Mako system in 20 patients undergoing medial UKA surgery by comparing preoperative and postoperative 3-dimensional CT scans. They found that the femoral component was within 0.8 mm and 0.9° in all directions and that the tibial component was within 0.9 mm and 1.7° in all directions. They concluded that the accuracy of component positioning with the Mako system was excellent. Finally, Plate and colleagues17 assessed the accuracy of soft tissue balancing in the Mako system in 52 patients undergoing medial UKA surgery. They compared the balance plan with the soft tissue balance after implantation and the Mako system quantified soft tissue balance as the amount of mm of the knee being tight or loose at 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°, and 110° of flexion. They found that at all flexion angles the ligament balancing was accurate up to 0.53 mm of the original plan. Furthermore, they noted that in 83% of cases the accuracy was within 1 mm at all flexion angles.

For the Navio system, Smith and colleagues74 assessed the accuracy of component positioning using 20 synthetic femurs and tibia. They reported a maximum rotational error of 3.2°, an angular error of 1.46° in all orientations, and a maximum translational error of 1.18 mm for both the tibial and femoral implants. Lonner and colleagues75 assessed the accuracy of component positioning in 25 cadaveric specimens. They found similar results as were found in the study of Smith and colleagues74 and concluded that these results were similar to other semi-active robotic systems designed for UKA.

For TKA surgery, Ponder and colleagues76 assessed the accuracy of the OmniBotic system and found that the average error in the anterior-posterior dimension between the targeted and measured cuts was -0.14 mm, and that the standard deviation in guide positioning for the distal, anterior chamfer, and posterior chamfer resections was 0.03° and 0.17 mm. Koenig and colleagues62 assessed the accuracy of the OmniBotic system in the first 100 cases and found that 98% of the cases were within 3° of the neutral mechanical axis. Furthermore, they found a learning curve with regard to tourniquet time between the first and second 10 patients in which they performed robotic-assisted TKA surgery. Siebert and colleagues63 assessed the accuracy of mechanical alignment in the Caspar system in 70 patients treated with the robotic system. They found that the difference between preoperatively planned and postoperatively achieved mechanical alignment was 0.8°. Similarly, Bellemans and colleagues77 assessed mechanical alignment and the positioning and rotation of the tibial and femoral components in a clinical study of 25 cases using the Caspar system. They noted that none of the patients had mechanical alignment, tibial or femoral component positioning, or rotation beyond 1° of the neutral axis. Liow and colleagues56 assessed the accuracy of mechanical axis alignment and component sizing accuracy using the Robodoc system in 25 patients. They reported that the mean postoperative alignment was 0.4° valgus and that all cases were within 3° of the neutral mechanical axis. Furthermore, they reported a mean surgical time of 96 minutes and reported that preoperative planning yielded femoral and tibial component size accuracy of 100%.

These studies have shown that robotic systems for UKA and TKA are accurate in the surgical variables they aim to control. These studies validated tight control of mechanical axis alignment, decrease for outliers, and component positioning and rotation, and also found that the balancing of soft tissues was improved using robotic-assisted surgery.

Robotic-Assisted vs Conventional Knee Arthroplasty

Despite the fact that these systems are accurate in the variables they aim to control, these systems have to be compared to the gold standard of conventional knee arthroplasty. For UKA, Cobb and colleagues70 performed a randomized clinical trial for patients treated undergoing UKA with robotic-assistance of the Acrobot systems compared to conventional UKA and assessed differences in mechanical accuracy. A total of 27 patients were randomly assigned to one of both treatments. They found that in the group of robotic-assisted surgery, 100% of the patients had a mechanical axis within 2° of neutral, while this was only 40% in the conventional UKA groups (difference P < .001). They also assessed the increase in functional outcomes and noted a trend towards improvement in performance with increasing accuracy at 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively. Lonner and colleagues78 also compared the tibial component positioning between robotic-assisted UKA surgery using the Mako system and conventional UKA surgery. The authors found that the variance in tibial slope, in coronal plane of the tibial component, and varus/valgus alignment were all larger with conventional UKA when compared to robotic-assisted UKA. Citak and colleagues79 compared the accuracy of tibial and femoral implant positioning between robotic-assisted surgery using the Mako system and conventional UKA in a cadaveric study. They reported that the root mean square (RMS) error of femoral component was 1.9 mm and 3.7° in robotic-assisted surgery and 5.4 mm and 10.2° for conventional UKA, while the RMS error for tibial component were 1.4 mm and 5.0° for robotic-assisted surgery and 5.7 mm and 19.2° for conventional UKA surgery. MacCallum and colleagues80 compared the tibial base plate position in a prospective clinical study of 177 patients treated with conventional UKA and 87 patients treated with robotic-assisted surgery using the Mako system. They found that surgery with robotic-assistance was more precise in the coronal and sagittal plane and was more accurate in coronal alignment when compared to conventional UKA. Finally, the first results of robotic-assisted UKA surgery have been presented. Coon and colleagues81 reported the preliminary results of a multicenter study of 854 patients and found a survivorship of 98.9% and satisfaction rate of 92% at minimum 2-year follow-up. Comparing these results to other large conventional UKA cohorts82,83 suggests that robotic-assisted surgery may improve survivorship at short-term follow-up. However, comparative studies and studies with longer follow-up are necessary to assess the additional value of robotic-assisted UKA surgery. Due to the relatively new concept of robotic-assisted surgery, these studies have not been performed or published yet.

For TKA, several studies also have compared how these robotic-systems control the surgical variables compared to conventional TKA surgery. Siebert and colleagues63 assessed mechanical axis accuracy and mechanical outliers following robotic-assisted TKA surgery using the Caspar system and conventional TKA surgery. They reported the difference between preoperative planned and postoperative achieved alignment was 0.8° for robotic-assisted surgery and 2.6° for conventional TKA surgery. Furthermore, they showed that 1 patient in the robotic-assisted group (1.4%) and 18 patients in the conventional TKA group (35%) had mechanical alignment greater than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis. Liow and colleagues56 found similar differences in their prospective randomized study in which they reported that 0% outliers greater than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis were found in the robotic-assisted group while 19.4% of the patients in the conventional TKA group had mechanical axis outliers. They also assessed the joint-line outliers in both procedures and found that 3.2% had joint-line outliers greater than 5 mm in the robotic-assisted group compared to 20.6% in the conventional TKA group. Kim and colleagues65 assessed implant accuracy in robotic-assisted surgery using the ROBODOC system and in conventional surgery and reported higher implant accuracy and fewer outliers using robotic-assisted surgery. Moon and colleagues66 compared robotic-assisted TKA surgery using the Robodoc system with conventional TKA surgery in 10 cadavers. They found that robotic-assisted surgery had excellent precision in all planes and had better accuracy in femoral rotation alignment compared to conventional TKA surgery. Park and Lee67 compared Robodoc robotic-assisted TKA surgery with conventional TKA surgery in a randomized clinical trial of 72 patients. They found that robotic-assisted surgery had definitive advantages in preoperative planning, accuracy of the procedure, and postoperative follow-up regarding femoral and tibial component flexion angles. Finally, Song and colleagues68,69 performed 2 randomized clinical trials in which they compared mechanical axis alignment, component positioning, soft tissue balancing, and patient preference between conventional TKA surgery and robotic-assisted surgery using the Robodoc system. In the first study,68 they simultaneously performed robotic-assisted surgery in one leg and conventional TKA surgery in the other leg. They found that robotic-assisted surgery resulted in less outlier in mechanical axis and component positioning. Furthermore, they found at latest follow-up of 2 years that 12 patients preferred the leg treated with robotic-assisted surgery while 6 preferred the conventional leg. Despite this finding, no significant differences in functional outcome scores were detected between both treatment options. Furthermore, they found that flexion-extension balance was achieved in 92% of patients treated with robotic-assisted TKA surgery and in 77% of patients treated with conventional TKA surgery. In the other study,69 the authors found that more patients treated with robotic-assisted surgery had <2 mm flexion-extension gap and more satisfactory posterior cruciate ligament tension when compared to conventional surgery.

These studies have shown that robotic-assisted surgery is accurate in controlling surgical variables, such as mechanical lower leg alignment, maintaining joint-line, implant positioning, and soft tissue balancing. Furthermore, these studies have shown that controlling these variables is better than the current gold standard of manual knee arthroplasty. Until now, not many studies have assessed survivorship of robotic-assisted surgery. Furthermore, no studies have, to our knowledge, compared survivorship of robotic-assisted with conventional knee replacement surgery. Finally, studies comparing functional outcomes following robotic-assisted surgery and conventional knee arthroplasty surgery are frequently underpowered due to their small sample sizes.68,70 Since many studies have shown that the surgical variables are more tightly controlled using robotic-assisted surgery when compared to conventional surgery, large comparative studies are necessary to assess the role of robotic-assisted surgery in functional outcomes and survivorship of UKA and TKA.

Cost-Effectiveness of Robotic-Assisted Surgery

High initial capital costs of robotic-assisted surgery is one of the factors that constitute a barrier to the widespread implementation of this technique. Multiple authors have suggested that improved implant survivorship afforded by robotic-assisted surgery may justify the expenditure from both societal and provider perspective.84-86 Two studies have performed a cost-effectiveness analysis for UKA surgery. Swank and colleagues84 reviewed the hospital expenditures and profits associated with robot-assisted knee arthroplasty, citing upfront costs of approximately $800,000. The authors estimated a mean per-case contribution profit of $5790 for robotic-assisted UKA, assuming an inpatient-to-outpatient ratio of 1 to 3. Based on this data, Swank and colleagues84 proposed that the capital costs of robotic-assisted UKA may be recovered in as little as 2 years when in the first 3 consecutive years 50, 70, and 90 cases were performed using robotic-assisted UKA. Moschetti and colleagues85 recently published the first formal cost-effectiveness analysis of robotic-assisted compared to manual UKA. The authors used an annual revision risk of 0.55% for the first 2 years following robot-assisted UKA, based on the aforementioned presented data by Coon and colleagues.81 They based their data on the Mako system and assumed an initial capital expenditure of $934,728 with annual servicing costs of 10% (discounted annually) for 4 years thereafter, resulting in a total cost of the robotic system of $1.362 million. These costs were divided by the number of patients estimated to undergo robotic-assisted UKA per year, which was varied to estimate the effect of case volume on cost-effectiveness. The authors reported that robotic-assisted UKA was associated with higher lifetime costs and net utilities compared to manual UKA, at an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $47,180 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) in a high-volume center. This falls well within the societal willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000/QALY. Sensitivity analysis showed that robotic-assisted UKA is cost-effective under the following conditions: (1) centers performing at least 94 cases annually, (2) in patients younger than age 67 years, and (3) 2-year revision rate does not exceed 1.2%. While the results of this initial analysis are promising, follow-up cost-effectiveness analysis studies will be required as long-term survivorship data become available.

Conclusion

Tighter control of intraoperative surgical variables, such as lower leg alignment, soft tissue balance, joint-line maintenance, and component alignment and positioning, have been associated with improved survivorship and functional outcomes. Upon reviewing the available literature on robotic-assisted surgery, it becomes clear that this technique can improve the accuracy of these surgical variables and is superior to conventional manual UKA and TKA. Although larger and comparative survivorship studies are necessary to compare robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty to conventional techniques, the early results and cost-effectiveness analysis seem promising.

1. van der List JP, McDonald LS, Pearle AD. Systematic review of medial versus lateral survivorship in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2015;22(6):454-460.

2. Mont MA, Pivec R, Issa K, Kapadia BH, Maheshwari A, Harwin SF. Long-term implant survivorship of cementless total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Knee Surg. 2014;27(5):369-376.

3. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2014 Australian Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Register. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/documents/10180/172286/Annual%20Report%202014. Accessed April 6, 2016.

4. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2015 Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. http://www.myknee.se/pdf/SVK_2015_Eng_1.0.pdf. Published December 1, 2015. Accessed April 6, 2016.

5. Centre of excellence of joint replacements. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/eng/Report_2010.pdf. Published June 2010. Accessed June 3, 2015.

6. National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. 12th Annual Report 2015. http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Portals/0/Documents/England/Reports/12th%20annual%20report/NJR%20Online%20Annual%20Report%202015.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2016.

7. The New Zealand Joint Registry. Fourteen Year Report January 1999 to December 2012. http://www.nzoa.org.nz/system/files/NJR%2014%20Year%20Report.pdf. Published November 2013. Accessed April 6, 2016.

8. Jeffery RS, Morris RW, Denham RA. Coronal alignment after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(5):709-714.

9. Rand JA, Coventry MB. Ten-year evaluation of geometric total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:168-173.

10. Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:153-156.

11. Ryd L, Lindstrand A, Stenström A, Selvik G. Porous coated anatomic tricompartmental tibial components. The relationship between prosthetic position and micromotion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;251:189-197.

12. van der List JP, Chawla H, Villa JC, Zuiderbaan HA, Pearle AD. Early functional outcome after lateral UKA is sensitive to postoperative lower limb alignment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

13. van der List JP, Zuiderbaan HA, Pearle AD. Why do medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasties fail today? J Arthroplasty. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

14. Vasso M, Del Regno C, D’Amelio A, Viggiano D, Corona K, Schiavone Panni A. Minor varus alignment provides better results than neutral alignment in medial UKA. Knee. 2015;22(2):117-121.

15. Attfield SF, Wilton TJ, Pratt DJ, Sambatakakis A. Soft-tissue balance and recovery of proprioception after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(4):540-545.

16. Pagnano MW, Hanssen AD, Lewallen DG, Stuart MJ. Flexion instability after primary posterior cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:39-46.

17. Plate JF, Mofidi A, Mannava S, et al. Achieving accurate ligament balancing using robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Adv Orthop. 2013;2013:837167.

18. Roche M, Elson L, Anderson C. Dynamic soft tissue balancing in total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):157-165.

19. Wasielewski RC, Galante JO, Leighty RM, Natarajan RN, Rosenberg AG. Wear patterns on retrieved polyethylene tibial inserts and their relationship to technical considerations during total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:31-43.

20. Ji HM, Han J, Jin DS, Seo H, Won YY. Kinematically aligned TKA can align knee joint line to horizontal. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]

21. Khamaisy S, Zuiderbaan HA, van der List JP, Nam D, Pearle AD. Medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty improves congruence and restores joint space width of the lateral compartment. Knee. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]

22. Niinimaki TT, Murray DW, Partanen J, Pajala A, Leppilahti JI. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasties implanted for osteoarthritis with partial loss of joint space have high re-operation rates. Knee. 2011;18(6):432-435.

23. Zuiderbaan HA, Khamaisy S, Thein R, Nawabi DH, Pearle AD. Congruence and joint space width alterations of the medial compartment following lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(1):50-55.

24. Barbadoro P, Ensini A, Leardini A, et al. Tibial component alignment and risk of loosening in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a radiographic and radiostereometric study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(12):3157-3162.

25. Collier MB, Eickmann TH, Sukezaki F, McAuley JP, Engh GA. Patient, implant, and alignment factors associated with revision of medial compartment unicondylar arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6 Suppl 2):108-115.

26. Nedopil AJ, Howell SM, Hull ML. Does malrotation of the tibial and femoral components compromise function in kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty? Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(1):41-50.

27. Rosskopf J, Singh PK, Wolf P, Strauch M, Graichen H. Influence of intentional femoral component flexion in navigated TKA on gap balance and sagittal anatomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(3):687-693.

28. Zihlmann MS, Stacoff A, Romero J, Quervain IK, Stüssi E. Biomechanical background and clinical observations of rotational malalignment in TKA: literature review and consequences. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2005;20(7):661-668.

29. Bonnin MP, Saffarini M, Shepherd D, Bossard N, Dantony E. Oversizing the tibial component in TKAs: incidence, consequences and risk factors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

30. Bonnin MP, Schmidt A, Basiglini L, Bossard N, Dantony E. Mediolateral oversizing influences pain, function, and flexion after TKA. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(10):2314-2324.

31. Chau R, Gulati A, Pandit H, et al. Tibial component overhang following unicompartmental knee replacement--does it matter? Knee. 2009;16(5):310-313.

32. Mueller JK, Wentorf FA, Moore RE. Femoral and tibial insert downsizing increases the laxity envelope in TKA. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(12):3003-3011.

33. Sriphirom P, Raungthong N, Chutchawan P, Thiranon C, Sukandhavesa N. Influence of a secondary downsizing of the femoral component on the extension gap: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2012;35(10 Suppl):56-59.

34. Young SW, Clarke HD, Graves SE, Liu YL, de Steiger RN. Higher rate of revision in PFC sigma primary total knee arthroplasty with mismatch of femoro-tibial component sizes. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(5):813-817.

35. Barink M, Verdonschot N, de Waal Malefijt M. A different fixation of the femoral component in total knee arthroplasty may lead to preservation of femoral bone stock. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2003;217(5):325-332.

36. Eagar P, Hull ML, Howell SM. How the fixation method stiffness and initial tension affect anterior load-displacement of the knee and tension in anterior cruciate ligament grafts: a study in cadaveric knees using a double-loop hamstrings graft. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(3):613-624.

37. Fricka KB, Sritulanondha S, McAsey CJ. To cement or not? Two-year results of a prospective, randomized study comparing cemented vs. cementless total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 Suppl):55-58.

38. Kendrick BJ, Kaptein BL, Valstar ER, et al. Cemented versus cementless Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty using radiostereometric analysis: a randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(2):185-191.

39. Kim TK, Chang CB, Kang YG, Chung BJ, Cho HJ, Seong SC. Execution accuracy of bone resection and implant fixation in computer assisted minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2010;17(1):23-28.

40. Whiteside LA. Making your next unicompartmental knee arthroplasty last: three keys to success. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(4 Suppl 2):2-3.

41. Bauwens K, Matthes G, Wich M, et al. Navigated total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(2):261-269.

42. Brin YS, Nikolaou VS, Joseph L, Zukor DJ, Antoniou J. Imageless computer assisted versus conventional total knee replacement. A Bayesian meta-analysis of 23 comparative studies. Int Orthop. 2011;35(3):331-339.

43. Cheng T, Zhang G, Zhang X. Imageless navigation system does not improve component rotational alignment in total knee arthroplasty. J Surg Res. 2011;171(2):590-600.

44. Conteduca F, Iorio R, Mazza D, Ferretti A. Patient-specific instruments in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2014;38(2):259-265.

45. Fu Y, Wang M, Liu Y, Fu Q. Alignment outcomes in navigated total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(6):1075-1082.

46. Hetaimish BM, Khan MM, Simunovic N, Al-Harbi HH, Bhandari M, Zalzal PK. Meta-analysis of navigation vs conventional total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1177-1182.

47. Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(8):1097-1106.

48. Moskal JT, Capps SG, Mann JW, Scanelli JA. Navigated versus conventional total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2014;27(3):235-248.

49. Shi J, Wei Y, Wang S, et al. Computer navigation and total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2014;37(1):e39-e43.

50. Nair R, Tripathy G, Deysine GR. Computer navigation systems in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Am J Orthop. 2014;43(6):256-261.

51. Weber P, Crispin A, Schmidutz F, et al. Improved accuracy in computer-assisted unicondylar knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(11):2453-2461.

52. Alcelik IA, Blomfield MI, Diana G, Gibbon AJ, Carrington N, Burr S. A comparison of short-term outcomes of minimally invasive computer-assisted vs minimally invasive conventional instrumentation for primary total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(2):410-418.

53. Cheng T, Pan XY, Mao X, Zhang GY, Zhang XL. Little clinical advantage of computer-assisted navigation over conventional instrumentation in primary total knee arthroplasty at early follow-up. Knee. 2012;19(4):237-245.

54. Rebal BA, Babatunde OM, Lee JH, Geller JA, Patrick DA Jr, Macaulay W. Imageless computer navigation in total knee arthroplasty provides superior short term functional outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):938-944.

55. Zamora LA, Humphreys KJ, Watt AM, Forel D, Cameron AL. Systematic review of computer-navigated total knee arthroplasty. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83(1-2):22-30.

56. Liow MH, Xia Z, Wong MK, Tay KJ, Yeo SJ, Chin PL. Robot-assisted total knee arthroplasty accurately restores the joint line and mechanical axis. A prospective randomised study. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(12):2373-2377.

57. Koulalis D, O’Loughlin PF, Plaskos C, Kendoff D, Cross MB, Pearle AD. Sequential versus automated cutting guides in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2011;18(6):436-442.

58. Clark TC, Schmidt FH. Robot-assisted navigation versus computer-assisted navigation in primary total knee arthroplasty: efficiency and accuracy. ISRN Orthop. 2013;2013:794827.

59. DiGioia AM 3rd, Jaramaz B, Colgan BD. Computer assisted orthopaedic surgery. Image guided and robotic assistive technologies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998(354):8-16.

60. Conditt MA, Roche MW. Minimally invasive robotic-arm-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91 Suppl 1:63-68.

61. Lonner JH. Robotically assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with a handheld image-free sculpting tool. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(1):29-40.

62. Koenig JA, Suero EM, Plaskos C. Surgical accuracy and efficiency of computer-navigated TKA with a robotic cutting guide–report on the first 100 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94-B(SUPP XLIV):103. Available at: http://www.bjjprocs.boneandjoint.org.uk/content/94-B/SUPP_XLIV/103. Accessed April 6, 2016.

63. Siebert W, Mai S, Kober R, Heeckt PF. Technique and first clinical results of robot-assisted total knee replacement. Knee. 2002;9(3):173-180.

64. Schulz AP, Seide K, Queitsch C, et al. Results of total hip replacement using the Robodoc surgical assistant system: clinical outcome and evaluation of complications for 97 procedures. Int J Med Robot. 2007;3(4):301-306.

65. Kim SM, Park YS, Ha CW, Lim SJ, Moon YW. Robot-assisted implantation improves the precision of component position in minimally invasive TKA. Orthopedics. 2012;35(9):e1334-e1339.

66. Moon YW, Ha CW, Do KH, et al. Comparison of robot-assisted and conventional total knee arthroplasty: a controlled cadaver study using multiparameter quantitative three-dimensional CT assessment of alignment. Comput Aided Surg. 2012;17(2):86-95.

67. Park SE, Lee CT. Comparison of robotic-assisted and conventional manual implantation of a primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(7):1054-1059.

68. Song EK, Seon JK, Park SJ, Jung WB, Park HW, Lee GW. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty with robotic and conventional techniques: a prospective, randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(7):1069-1076.

69. Song EK, Seon JK, Yim JH, Netravali NA, Bargar WL. Robotic-assisted TKA reduces postoperative alignment outliers and improves gap balance compared to conventional TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):118-126.

70. Cobb J, Henckel J, Gomes P, et al. Hands-on robotic unicompartmental knee replacement: a prospective, randomised controlled study of the acrobot system. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(2):188-197.

71. Jakopec M, Harris SJ, Rodriguez y Baena F, Gomes P, Cobb J, Davies BL. The first clinical application of a “hands-on” robotic knee surgery system. Comput Aided Surg. 2001;6(6):329-339.

72. Pearle AD, O’Loughlin PF, Kendoff DO. Robot-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(2):230-237.

73. Dunbar NJ, Roche MW, Park BH, Branch SH, Conditt MA, Banks SA. Accuracy of dynamic tactile-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):803-808.e1.

74. Smith JR, Riches PE, Rowe PJ. Accuracy of a freehand sculpting tool for unicondylar knee replacement. Int J Med Robot. 2014;10(2):162-169.

75. Lonner JH, Smith JR, Picard F, Hamlin B, Rowe PJ, Riches PE. High degree of accuracy of a novel image-free handheld robot for unicondylar knee arthroplasty in a cadaveric study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):206-212.

76. Ponder C, Plaskos C, Cheal E. Press-fit total knee arthroplasty with a robotic-cutting guide: proof of concept and initial clinical experience. Bone & Joint Journal Orthopaedic Proceedings Supplement. 2013;95(SUPP 28):61. Available at: http://www.bjjprocs.boneandjoint.org.uk/content/95-B/SUPP_28/61.abstract. Accessed April 6, 2016.

77. Bellemans J, Vandenneucker H, Vanlauwe J. Robot-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:111-116.

78. Lonner JH, John TK, Conditt MA. Robotic arm-assisted UKA improves tibial component alignment: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):141-146.

79. Citak M, Suero EM, Citak M, et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: is robotic technology more accurate than conventional technique? Knee. 2013;20(4):268-271.

80. MacCallum KP, Danoff JR, Geller JA. Tibial baseplate positioning in robotic-assisted and conventional unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26(1):93-98.

81. Coon T, Roche M, Pearle AD, Dounchis J, Borus T, Buechel F Jr. Two year survivorship of robotically guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Paper presented at: International Society for Technology in Arthroplasty 26th Annual Congress; October 16-19, 2013; Palm Beach, FL.

82. Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill HS, Barker K, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Minimally invasive Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee replacement: results of 1000 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(2):198-204.

83. Yoshida K, Tada M, Yoshida H, Takei S, Fukuoka S, Nakamura H. Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in Japan--clinical results in greater than one thousand cases over ten years. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9 Suppl):168-171.

84. Swank ML, Alkire M, Conditt M, Lonner JH. Technology and cost-effectiveness in knee arthroplasty: computer navigation and robotics. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(2 Suppl):32-36.

85. Moschetti WE, Konopka JF, Rubash HE, Genuario JW. Can robot-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty be cost-effective? A markovdecision analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

86. Thienpont E. Improving Accuracy in Knee Arthroplasty. 1st ed. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2012.

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are 2 reliable treatment options for patients with primary osteoarthritis. Recently published systematic reviews of cohort studies have shown that 10-year survivorship of medial and lateral UKA is 92% and 91%, respectively,1 while 10-year survivorship of TKA in cohort studies is 95%.2 National and annual registries show a similar trend, although the reported survivorship is lower.1,3-7

In order to improve these survivorship rates, the surgical variables that can intraoperatively be controlled by the orthopedic surgeon have been evaluated. These variables include lower leg alignment, soft tissue balance, joint line maintenance, and alignment, size, and fixation of the tibial and femoral component. Several studies have shown that tight control of lower leg alignment,8-14 balancing of the soft tissues,15-19 joint line maintenance,20-23 component alignment,24-28 component size,29-34 and component fixation35-40 can improve the outcomes of UKA and TKA. As a result, over the past 2 decades, several computer-assisted surgery systems have been developed with the goal of more accurate and reliable control of these factors, and thus improved outcomes of knee arthroplasty.

These systems differ with regard to the number and type of variables they control. Computer navigation systems aim to control one or more of these surgical variables, and several meta-analyses have shown that these systems, when compared to conventional surgery, improve mechanical axis accuracy, decrease the risk for mechanical axis outliers, and improve component positioning in TKA41-49 and UKA surgery.50,51 Interestingly, however, meta-analyses have failed to show the expected superiority in clinical outcomes following computer navigation compared to conventional knee arthroplasty.48,52-55 Furthermore, authors have shown that, despite the fact that computer-navigated surgery increases the accuracy of mechanical alignment and surgical cutting, there is still room for improvement.56 As a consequence, robotic-assisted systems have been developed.

Similar to computer navigation, these robotic-assisted systems aim to control the surgical variables; in addition, they aim to improve the surgical precision of the procedure. Interestingly, 2 recent studies have shown that robotic-assisted systems are superior to computer navigation systems with regard to less cutting time and less resection deviations in coronal and sagittal plane in a cadaveric study,57 and shorter total surgery time, more accurate mechanical axis, and shorter hospital stay in a clinical study.58 Although these results are promising, the exact role of robotic surgery in knee arthroplasty remains unclear. In this review, we aim to report the current state of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty by discussing (1) the different robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty systems that are available for UKA and TKA surgery, (2) studies that assessed the role of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty in controlling the aforementioned surgical variables, (3) cadaveric and clinical comparative studies that compared how accurate robotic-assisted and conventional knee surgery control these surgical variables, and (4) studies that assessed the cost-effectiveness of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty surgery.

Robotic-Assisted Knee Arthroplasty Systems

Several systems have been developed over the years for knee arthroplasty, and these are usually defined as active, semi-active, or passive.59 Active systems are capable of performing tasks or processes autonomously under the watchful eye of the surgeon, while passive systems do not perform actions independently but provide the surgeon with information. In semi-active systems, the surgical action is physically constrained in order to follow a predefined strategy.

In the United States, 3 robotic systems are FDA-approved for knee arthroplasty. The Stryker/Mako haptic guided robot (Mako Surgical Corp.) was introduced in 2005 and has been used for over 50,000 UKA procedures (Figure 1). There are nearly 300 robotic systems used nationally, as it has 20% of the market share for UKA in the United States. The Mako system is a semi-active tactile robotic system that requires preoperative imaging, after which a preoperative planning is performed. Intraoperatively, the robotic arm is under direct surgeon control and gives real-time tactile feedback during the procedure (Figure 2).

Furthermore, the surgeon can intraoperatively virtually adjust component positioning and alignment and move the knee through the range of motion, after which the system can provide information on alignment, component position, and balance of the soft tissue (eg, if the knee is overtight or lax through the flexion-arch).60 This system has a burr that resects the bone and when the surgeon directs the burr outside the preplanned area, the burr stops and prevents unnecessary and unwanted resections (Figure 3).

The Navio Precision Free-Hand Sculptor (PFS) system (Blue Belt Technologies) has been used for 1500 UKA procedures, with 50 robots in use in the United States (Figure 4). This system is an image-free semi-active robotic system and has the same characteristics as the aforementioned Mako system.61 Finally, the OmniBotic robotic system (Omnilife Science) has been released for TKA and has been used for over 7300 procedures (Figure 5). This system has an automated cutting-guide technique in which the surgeon designs a virtual plan on the computer system. After this, the cutting-guides are placed by the robotic system at the planned location for all 5 femoral cuts (ie, distal, anterior chamfer, anterior, posterior chamfer, and posterior) and the surgeon then makes the final cuts.57,62

Three robotic systems for knee arthroplasty surgery have been used in Europe. The Caspar system (URS Ortho) is an active robotic system in which a computed tomography (CT) scan is performed preoperatively, after which a virtual implantation is performed on the screen. The surgeon can then obtain information on lower leg alignment, gap balancing, and component positioning, and after an operative plan is made, the surgical resections are performed by the robot. Reflective markers are attached to the leg and all robotic movements are monitored using an infrared camera system. Any undesired motion will be detected by this camera system and will stop all movements.63 A second and more frequently reported system in the literature is the active Robodoc surgical system (Curexo Technology Corporation). This system is designed for TKA and total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgery. Although initial studies reported a high incidence of system-related complications in THA,64 the use of this system for TKA has frequently been reported in the literature.56,63,65-69 A third robotic system that has been used in Europe is the Acrobot surgical system (Acrobot Company Ltd), which is an image-based semi-active robotic system70 used for both UKA and TKA surgery.70,71

Accuracy of Controlling Surgical Variables in Robotic-Assisted Knee Arthroplasty

Several studies have assessed the accuracy of robotic-assisted surgery in UKA surgery with regard to control of the aforementioned surgical variables. Pearle and colleagues72 assessed the mechanical axis accuracy of the Mako system in 10 patients undergoing medial UKA robotic-assisted surgery. They reported that the intraoperative registration lasted 7.5 minutes and the duration of time needed for robotic-assisted burring was 34.8 minutes. They compared the actual postoperative alignment at 6 weeks follow-up with the planned lower leg alignment and found that all measurements were within 1.6° of the planned lower leg alignment. Dunbar and colleagues73 assessed the accuracy of component positioning of the Mako system in 20 patients undergoing medial UKA surgery by comparing preoperative and postoperative 3-dimensional CT scans. They found that the femoral component was within 0.8 mm and 0.9° in all directions and that the tibial component was within 0.9 mm and 1.7° in all directions. They concluded that the accuracy of component positioning with the Mako system was excellent. Finally, Plate and colleagues17 assessed the accuracy of soft tissue balancing in the Mako system in 52 patients undergoing medial UKA surgery. They compared the balance plan with the soft tissue balance after implantation and the Mako system quantified soft tissue balance as the amount of mm of the knee being tight or loose at 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°, and 110° of flexion. They found that at all flexion angles the ligament balancing was accurate up to 0.53 mm of the original plan. Furthermore, they noted that in 83% of cases the accuracy was within 1 mm at all flexion angles.

For the Navio system, Smith and colleagues74 assessed the accuracy of component positioning using 20 synthetic femurs and tibia. They reported a maximum rotational error of 3.2°, an angular error of 1.46° in all orientations, and a maximum translational error of 1.18 mm for both the tibial and femoral implants. Lonner and colleagues75 assessed the accuracy of component positioning in 25 cadaveric specimens. They found similar results as were found in the study of Smith and colleagues74 and concluded that these results were similar to other semi-active robotic systems designed for UKA.

For TKA surgery, Ponder and colleagues76 assessed the accuracy of the OmniBotic system and found that the average error in the anterior-posterior dimension between the targeted and measured cuts was -0.14 mm, and that the standard deviation in guide positioning for the distal, anterior chamfer, and posterior chamfer resections was 0.03° and 0.17 mm. Koenig and colleagues62 assessed the accuracy of the OmniBotic system in the first 100 cases and found that 98% of the cases were within 3° of the neutral mechanical axis. Furthermore, they found a learning curve with regard to tourniquet time between the first and second 10 patients in which they performed robotic-assisted TKA surgery. Siebert and colleagues63 assessed the accuracy of mechanical alignment in the Caspar system in 70 patients treated with the robotic system. They found that the difference between preoperatively planned and postoperatively achieved mechanical alignment was 0.8°. Similarly, Bellemans and colleagues77 assessed mechanical alignment and the positioning and rotation of the tibial and femoral components in a clinical study of 25 cases using the Caspar system. They noted that none of the patients had mechanical alignment, tibial or femoral component positioning, or rotation beyond 1° of the neutral axis. Liow and colleagues56 assessed the accuracy of mechanical axis alignment and component sizing accuracy using the Robodoc system in 25 patients. They reported that the mean postoperative alignment was 0.4° valgus and that all cases were within 3° of the neutral mechanical axis. Furthermore, they reported a mean surgical time of 96 minutes and reported that preoperative planning yielded femoral and tibial component size accuracy of 100%.

These studies have shown that robotic systems for UKA and TKA are accurate in the surgical variables they aim to control. These studies validated tight control of mechanical axis alignment, decrease for outliers, and component positioning and rotation, and also found that the balancing of soft tissues was improved using robotic-assisted surgery.

Robotic-Assisted vs Conventional Knee Arthroplasty

Despite the fact that these systems are accurate in the variables they aim to control, these systems have to be compared to the gold standard of conventional knee arthroplasty. For UKA, Cobb and colleagues70 performed a randomized clinical trial for patients treated undergoing UKA with robotic-assistance of the Acrobot systems compared to conventional UKA and assessed differences in mechanical accuracy. A total of 27 patients were randomly assigned to one of both treatments. They found that in the group of robotic-assisted surgery, 100% of the patients had a mechanical axis within 2° of neutral, while this was only 40% in the conventional UKA groups (difference P < .001). They also assessed the increase in functional outcomes and noted a trend towards improvement in performance with increasing accuracy at 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively. Lonner and colleagues78 also compared the tibial component positioning between robotic-assisted UKA surgery using the Mako system and conventional UKA surgery. The authors found that the variance in tibial slope, in coronal plane of the tibial component, and varus/valgus alignment were all larger with conventional UKA when compared to robotic-assisted UKA. Citak and colleagues79 compared the accuracy of tibial and femoral implant positioning between robotic-assisted surgery using the Mako system and conventional UKA in a cadaveric study. They reported that the root mean square (RMS) error of femoral component was 1.9 mm and 3.7° in robotic-assisted surgery and 5.4 mm and 10.2° for conventional UKA, while the RMS error for tibial component were 1.4 mm and 5.0° for robotic-assisted surgery and 5.7 mm and 19.2° for conventional UKA surgery. MacCallum and colleagues80 compared the tibial base plate position in a prospective clinical study of 177 patients treated with conventional UKA and 87 patients treated with robotic-assisted surgery using the Mako system. They found that surgery with robotic-assistance was more precise in the coronal and sagittal plane and was more accurate in coronal alignment when compared to conventional UKA. Finally, the first results of robotic-assisted UKA surgery have been presented. Coon and colleagues81 reported the preliminary results of a multicenter study of 854 patients and found a survivorship of 98.9% and satisfaction rate of 92% at minimum 2-year follow-up. Comparing these results to other large conventional UKA cohorts82,83 suggests that robotic-assisted surgery may improve survivorship at short-term follow-up. However, comparative studies and studies with longer follow-up are necessary to assess the additional value of robotic-assisted UKA surgery. Due to the relatively new concept of robotic-assisted surgery, these studies have not been performed or published yet.

For TKA, several studies also have compared how these robotic-systems control the surgical variables compared to conventional TKA surgery. Siebert and colleagues63 assessed mechanical axis accuracy and mechanical outliers following robotic-assisted TKA surgery using the Caspar system and conventional TKA surgery. They reported the difference between preoperative planned and postoperative achieved alignment was 0.8° for robotic-assisted surgery and 2.6° for conventional TKA surgery. Furthermore, they showed that 1 patient in the robotic-assisted group (1.4%) and 18 patients in the conventional TKA group (35%) had mechanical alignment greater than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis. Liow and colleagues56 found similar differences in their prospective randomized study in which they reported that 0% outliers greater than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis were found in the robotic-assisted group while 19.4% of the patients in the conventional TKA group had mechanical axis outliers. They also assessed the joint-line outliers in both procedures and found that 3.2% had joint-line outliers greater than 5 mm in the robotic-assisted group compared to 20.6% in the conventional TKA group. Kim and colleagues65 assessed implant accuracy in robotic-assisted surgery using the ROBODOC system and in conventional surgery and reported higher implant accuracy and fewer outliers using robotic-assisted surgery. Moon and colleagues66 compared robotic-assisted TKA surgery using the Robodoc system with conventional TKA surgery in 10 cadavers. They found that robotic-assisted surgery had excellent precision in all planes and had better accuracy in femoral rotation alignment compared to conventional TKA surgery. Park and Lee67 compared Robodoc robotic-assisted TKA surgery with conventional TKA surgery in a randomized clinical trial of 72 patients. They found that robotic-assisted surgery had definitive advantages in preoperative planning, accuracy of the procedure, and postoperative follow-up regarding femoral and tibial component flexion angles. Finally, Song and colleagues68,69 performed 2 randomized clinical trials in which they compared mechanical axis alignment, component positioning, soft tissue balancing, and patient preference between conventional TKA surgery and robotic-assisted surgery using the Robodoc system. In the first study,68 they simultaneously performed robotic-assisted surgery in one leg and conventional TKA surgery in the other leg. They found that robotic-assisted surgery resulted in less outlier in mechanical axis and component positioning. Furthermore, they found at latest follow-up of 2 years that 12 patients preferred the leg treated with robotic-assisted surgery while 6 preferred the conventional leg. Despite this finding, no significant differences in functional outcome scores were detected between both treatment options. Furthermore, they found that flexion-extension balance was achieved in 92% of patients treated with robotic-assisted TKA surgery and in 77% of patients treated with conventional TKA surgery. In the other study,69 the authors found that more patients treated with robotic-assisted surgery had <2 mm flexion-extension gap and more satisfactory posterior cruciate ligament tension when compared to conventional surgery.

These studies have shown that robotic-assisted surgery is accurate in controlling surgical variables, such as mechanical lower leg alignment, maintaining joint-line, implant positioning, and soft tissue balancing. Furthermore, these studies have shown that controlling these variables is better than the current gold standard of manual knee arthroplasty. Until now, not many studies have assessed survivorship of robotic-assisted surgery. Furthermore, no studies have, to our knowledge, compared survivorship of robotic-assisted with conventional knee replacement surgery. Finally, studies comparing functional outcomes following robotic-assisted surgery and conventional knee arthroplasty surgery are frequently underpowered due to their small sample sizes.68,70 Since many studies have shown that the surgical variables are more tightly controlled using robotic-assisted surgery when compared to conventional surgery, large comparative studies are necessary to assess the role of robotic-assisted surgery in functional outcomes and survivorship of UKA and TKA.

Cost-Effectiveness of Robotic-Assisted Surgery

High initial capital costs of robotic-assisted surgery is one of the factors that constitute a barrier to the widespread implementation of this technique. Multiple authors have suggested that improved implant survivorship afforded by robotic-assisted surgery may justify the expenditure from both societal and provider perspective.84-86 Two studies have performed a cost-effectiveness analysis for UKA surgery. Swank and colleagues84 reviewed the hospital expenditures and profits associated with robot-assisted knee arthroplasty, citing upfront costs of approximately $800,000. The authors estimated a mean per-case contribution profit of $5790 for robotic-assisted UKA, assuming an inpatient-to-outpatient ratio of 1 to 3. Based on this data, Swank and colleagues84 proposed that the capital costs of robotic-assisted UKA may be recovered in as little as 2 years when in the first 3 consecutive years 50, 70, and 90 cases were performed using robotic-assisted UKA. Moschetti and colleagues85 recently published the first formal cost-effectiveness analysis of robotic-assisted compared to manual UKA. The authors used an annual revision risk of 0.55% for the first 2 years following robot-assisted UKA, based on the aforementioned presented data by Coon and colleagues.81 They based their data on the Mako system and assumed an initial capital expenditure of $934,728 with annual servicing costs of 10% (discounted annually) for 4 years thereafter, resulting in a total cost of the robotic system of $1.362 million. These costs were divided by the number of patients estimated to undergo robotic-assisted UKA per year, which was varied to estimate the effect of case volume on cost-effectiveness. The authors reported that robotic-assisted UKA was associated with higher lifetime costs and net utilities compared to manual UKA, at an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $47,180 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) in a high-volume center. This falls well within the societal willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000/QALY. Sensitivity analysis showed that robotic-assisted UKA is cost-effective under the following conditions: (1) centers performing at least 94 cases annually, (2) in patients younger than age 67 years, and (3) 2-year revision rate does not exceed 1.2%. While the results of this initial analysis are promising, follow-up cost-effectiveness analysis studies will be required as long-term survivorship data become available.

Conclusion

Tighter control of intraoperative surgical variables, such as lower leg alignment, soft tissue balance, joint-line maintenance, and component alignment and positioning, have been associated with improved survivorship and functional outcomes. Upon reviewing the available literature on robotic-assisted surgery, it becomes clear that this technique can improve the accuracy of these surgical variables and is superior to conventional manual UKA and TKA. Although larger and comparative survivorship studies are necessary to compare robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty to conventional techniques, the early results and cost-effectiveness analysis seem promising.

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are 2 reliable treatment options for patients with primary osteoarthritis. Recently published systematic reviews of cohort studies have shown that 10-year survivorship of medial and lateral UKA is 92% and 91%, respectively,1 while 10-year survivorship of TKA in cohort studies is 95%.2 National and annual registries show a similar trend, although the reported survivorship is lower.1,3-7

In order to improve these survivorship rates, the surgical variables that can intraoperatively be controlled by the orthopedic surgeon have been evaluated. These variables include lower leg alignment, soft tissue balance, joint line maintenance, and alignment, size, and fixation of the tibial and femoral component. Several studies have shown that tight control of lower leg alignment,8-14 balancing of the soft tissues,15-19 joint line maintenance,20-23 component alignment,24-28 component size,29-34 and component fixation35-40 can improve the outcomes of UKA and TKA. As a result, over the past 2 decades, several computer-assisted surgery systems have been developed with the goal of more accurate and reliable control of these factors, and thus improved outcomes of knee arthroplasty.

These systems differ with regard to the number and type of variables they control. Computer navigation systems aim to control one or more of these surgical variables, and several meta-analyses have shown that these systems, when compared to conventional surgery, improve mechanical axis accuracy, decrease the risk for mechanical axis outliers, and improve component positioning in TKA41-49 and UKA surgery.50,51 Interestingly, however, meta-analyses have failed to show the expected superiority in clinical outcomes following computer navigation compared to conventional knee arthroplasty.48,52-55 Furthermore, authors have shown that, despite the fact that computer-navigated surgery increases the accuracy of mechanical alignment and surgical cutting, there is still room for improvement.56 As a consequence, robotic-assisted systems have been developed.

Similar to computer navigation, these robotic-assisted systems aim to control the surgical variables; in addition, they aim to improve the surgical precision of the procedure. Interestingly, 2 recent studies have shown that robotic-assisted systems are superior to computer navigation systems with regard to less cutting time and less resection deviations in coronal and sagittal plane in a cadaveric study,57 and shorter total surgery time, more accurate mechanical axis, and shorter hospital stay in a clinical study.58 Although these results are promising, the exact role of robotic surgery in knee arthroplasty remains unclear. In this review, we aim to report the current state of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty by discussing (1) the different robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty systems that are available for UKA and TKA surgery, (2) studies that assessed the role of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty in controlling the aforementioned surgical variables, (3) cadaveric and clinical comparative studies that compared how accurate robotic-assisted and conventional knee surgery control these surgical variables, and (4) studies that assessed the cost-effectiveness of robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty surgery.

Robotic-Assisted Knee Arthroplasty Systems

Several systems have been developed over the years for knee arthroplasty, and these are usually defined as active, semi-active, or passive.59 Active systems are capable of performing tasks or processes autonomously under the watchful eye of the surgeon, while passive systems do not perform actions independently but provide the surgeon with information. In semi-active systems, the surgical action is physically constrained in order to follow a predefined strategy.

In the United States, 3 robotic systems are FDA-approved for knee arthroplasty. The Stryker/Mako haptic guided robot (Mako Surgical Corp.) was introduced in 2005 and has been used for over 50,000 UKA procedures (Figure 1). There are nearly 300 robotic systems used nationally, as it has 20% of the market share for UKA in the United States. The Mako system is a semi-active tactile robotic system that requires preoperative imaging, after which a preoperative planning is performed. Intraoperatively, the robotic arm is under direct surgeon control and gives real-time tactile feedback during the procedure (Figure 2).

Furthermore, the surgeon can intraoperatively virtually adjust component positioning and alignment and move the knee through the range of motion, after which the system can provide information on alignment, component position, and balance of the soft tissue (eg, if the knee is overtight or lax through the flexion-arch).60 This system has a burr that resects the bone and when the surgeon directs the burr outside the preplanned area, the burr stops and prevents unnecessary and unwanted resections (Figure 3).

The Navio Precision Free-Hand Sculptor (PFS) system (Blue Belt Technologies) has been used for 1500 UKA procedures, with 50 robots in use in the United States (Figure 4). This system is an image-free semi-active robotic system and has the same characteristics as the aforementioned Mako system.61 Finally, the OmniBotic robotic system (Omnilife Science) has been released for TKA and has been used for over 7300 procedures (Figure 5). This system has an automated cutting-guide technique in which the surgeon designs a virtual plan on the computer system. After this, the cutting-guides are placed by the robotic system at the planned location for all 5 femoral cuts (ie, distal, anterior chamfer, anterior, posterior chamfer, and posterior) and the surgeon then makes the final cuts.57,62

Three robotic systems for knee arthroplasty surgery have been used in Europe. The Caspar system (URS Ortho) is an active robotic system in which a computed tomography (CT) scan is performed preoperatively, after which a virtual implantation is performed on the screen. The surgeon can then obtain information on lower leg alignment, gap balancing, and component positioning, and after an operative plan is made, the surgical resections are performed by the robot. Reflective markers are attached to the leg and all robotic movements are monitored using an infrared camera system. Any undesired motion will be detected by this camera system and will stop all movements.63 A second and more frequently reported system in the literature is the active Robodoc surgical system (Curexo Technology Corporation). This system is designed for TKA and total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgery. Although initial studies reported a high incidence of system-related complications in THA,64 the use of this system for TKA has frequently been reported in the literature.56,63,65-69 A third robotic system that has been used in Europe is the Acrobot surgical system (Acrobot Company Ltd), which is an image-based semi-active robotic system70 used for both UKA and TKA surgery.70,71

Accuracy of Controlling Surgical Variables in Robotic-Assisted Knee Arthroplasty

Several studies have assessed the accuracy of robotic-assisted surgery in UKA surgery with regard to control of the aforementioned surgical variables. Pearle and colleagues72 assessed the mechanical axis accuracy of the Mako system in 10 patients undergoing medial UKA robotic-assisted surgery. They reported that the intraoperative registration lasted 7.5 minutes and the duration of time needed for robotic-assisted burring was 34.8 minutes. They compared the actual postoperative alignment at 6 weeks follow-up with the planned lower leg alignment and found that all measurements were within 1.6° of the planned lower leg alignment. Dunbar and colleagues73 assessed the accuracy of component positioning of the Mako system in 20 patients undergoing medial UKA surgery by comparing preoperative and postoperative 3-dimensional CT scans. They found that the femoral component was within 0.8 mm and 0.9° in all directions and that the tibial component was within 0.9 mm and 1.7° in all directions. They concluded that the accuracy of component positioning with the Mako system was excellent. Finally, Plate and colleagues17 assessed the accuracy of soft tissue balancing in the Mako system in 52 patients undergoing medial UKA surgery. They compared the balance plan with the soft tissue balance after implantation and the Mako system quantified soft tissue balance as the amount of mm of the knee being tight or loose at 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°, and 110° of flexion. They found that at all flexion angles the ligament balancing was accurate up to 0.53 mm of the original plan. Furthermore, they noted that in 83% of cases the accuracy was within 1 mm at all flexion angles.

For the Navio system, Smith and colleagues74 assessed the accuracy of component positioning using 20 synthetic femurs and tibia. They reported a maximum rotational error of 3.2°, an angular error of 1.46° in all orientations, and a maximum translational error of 1.18 mm for both the tibial and femoral implants. Lonner and colleagues75 assessed the accuracy of component positioning in 25 cadaveric specimens. They found similar results as were found in the study of Smith and colleagues74 and concluded that these results were similar to other semi-active robotic systems designed for UKA.

For TKA surgery, Ponder and colleagues76 assessed the accuracy of the OmniBotic system and found that the average error in the anterior-posterior dimension between the targeted and measured cuts was -0.14 mm, and that the standard deviation in guide positioning for the distal, anterior chamfer, and posterior chamfer resections was 0.03° and 0.17 mm. Koenig and colleagues62 assessed the accuracy of the OmniBotic system in the first 100 cases and found that 98% of the cases were within 3° of the neutral mechanical axis. Furthermore, they found a learning curve with regard to tourniquet time between the first and second 10 patients in which they performed robotic-assisted TKA surgery. Siebert and colleagues63 assessed the accuracy of mechanical alignment in the Caspar system in 70 patients treated with the robotic system. They found that the difference between preoperatively planned and postoperatively achieved mechanical alignment was 0.8°. Similarly, Bellemans and colleagues77 assessed mechanical alignment and the positioning and rotation of the tibial and femoral components in a clinical study of 25 cases using the Caspar system. They noted that none of the patients had mechanical alignment, tibial or femoral component positioning, or rotation beyond 1° of the neutral axis. Liow and colleagues56 assessed the accuracy of mechanical axis alignment and component sizing accuracy using the Robodoc system in 25 patients. They reported that the mean postoperative alignment was 0.4° valgus and that all cases were within 3° of the neutral mechanical axis. Furthermore, they reported a mean surgical time of 96 minutes and reported that preoperative planning yielded femoral and tibial component size accuracy of 100%.

These studies have shown that robotic systems for UKA and TKA are accurate in the surgical variables they aim to control. These studies validated tight control of mechanical axis alignment, decrease for outliers, and component positioning and rotation, and also found that the balancing of soft tissues was improved using robotic-assisted surgery.

Robotic-Assisted vs Conventional Knee Arthroplasty

Despite the fact that these systems are accurate in the variables they aim to control, these systems have to be compared to the gold standard of conventional knee arthroplasty. For UKA, Cobb and colleagues70 performed a randomized clinical trial for patients treated undergoing UKA with robotic-assistance of the Acrobot systems compared to conventional UKA and assessed differences in mechanical accuracy. A total of 27 patients were randomly assigned to one of both treatments. They found that in the group of robotic-assisted surgery, 100% of the patients had a mechanical axis within 2° of neutral, while this was only 40% in the conventional UKA groups (difference P < .001). They also assessed the increase in functional outcomes and noted a trend towards improvement in performance with increasing accuracy at 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively. Lonner and colleagues78 also compared the tibial component positioning between robotic-assisted UKA surgery using the Mako system and conventional UKA surgery. The authors found that the variance in tibial slope, in coronal plane of the tibial component, and varus/valgus alignment were all larger with conventional UKA when compared to robotic-assisted UKA. Citak and colleagues79 compared the accuracy of tibial and femoral implant positioning between robotic-assisted surgery using the Mako system and conventional UKA in a cadaveric study. They reported that the root mean square (RMS) error of femoral component was 1.9 mm and 3.7° in robotic-assisted surgery and 5.4 mm and 10.2° for conventional UKA, while the RMS error for tibial component were 1.4 mm and 5.0° for robotic-assisted surgery and 5.7 mm and 19.2° for conventional UKA surgery. MacCallum and colleagues80 compared the tibial base plate position in a prospective clinical study of 177 patients treated with conventional UKA and 87 patients treated with robotic-assisted surgery using the Mako system. They found that surgery with robotic-assistance was more precise in the coronal and sagittal plane and was more accurate in coronal alignment when compared to conventional UKA. Finally, the first results of robotic-assisted UKA surgery have been presented. Coon and colleagues81 reported the preliminary results of a multicenter study of 854 patients and found a survivorship of 98.9% and satisfaction rate of 92% at minimum 2-year follow-up. Comparing these results to other large conventional UKA cohorts82,83 suggests that robotic-assisted surgery may improve survivorship at short-term follow-up. However, comparative studies and studies with longer follow-up are necessary to assess the additional value of robotic-assisted UKA surgery. Due to the relatively new concept of robotic-assisted surgery, these studies have not been performed or published yet.

For TKA, several studies also have compared how these robotic-systems control the surgical variables compared to conventional TKA surgery. Siebert and colleagues63 assessed mechanical axis accuracy and mechanical outliers following robotic-assisted TKA surgery using the Caspar system and conventional TKA surgery. They reported the difference between preoperative planned and postoperative achieved alignment was 0.8° for robotic-assisted surgery and 2.6° for conventional TKA surgery. Furthermore, they showed that 1 patient in the robotic-assisted group (1.4%) and 18 patients in the conventional TKA group (35%) had mechanical alignment greater than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis. Liow and colleagues56 found similar differences in their prospective randomized study in which they reported that 0% outliers greater than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis were found in the robotic-assisted group while 19.4% of the patients in the conventional TKA group had mechanical axis outliers. They also assessed the joint-line outliers in both procedures and found that 3.2% had joint-line outliers greater than 5 mm in the robotic-assisted group compared to 20.6% in the conventional TKA group. Kim and colleagues65 assessed implant accuracy in robotic-assisted surgery using the ROBODOC system and in conventional surgery and reported higher implant accuracy and fewer outliers using robotic-assisted surgery. Moon and colleagues66 compared robotic-assisted TKA surgery using the Robodoc system with conventional TKA surgery in 10 cadavers. They found that robotic-assisted surgery had excellent precision in all planes and had better accuracy in femoral rotation alignment compared to conventional TKA surgery. Park and Lee67 compared Robodoc robotic-assisted TKA surgery with conventional TKA surgery in a randomized clinical trial of 72 patients. They found that robotic-assisted surgery had definitive advantages in preoperative planning, accuracy of the procedure, and postoperative follow-up regarding femoral and tibial component flexion angles. Finally, Song and colleagues68,69 performed 2 randomized clinical trials in which they compared mechanical axis alignment, component positioning, soft tissue balancing, and patient preference between conventional TKA surgery and robotic-assisted surgery using the Robodoc system. In the first study,68 they simultaneously performed robotic-assisted surgery in one leg and conventional TKA surgery in the other leg. They found that robotic-assisted surgery resulted in less outlier in mechanical axis and component positioning. Furthermore, they found at latest follow-up of 2 years that 12 patients preferred the leg treated with robotic-assisted surgery while 6 preferred the conventional leg. Despite this finding, no significant differences in functional outcome scores were detected between both treatment options. Furthermore, they found that flexion-extension balance was achieved in 92% of patients treated with robotic-assisted TKA surgery and in 77% of patients treated with conventional TKA surgery. In the other study,69 the authors found that more patients treated with robotic-assisted surgery had <2 mm flexion-extension gap and more satisfactory posterior cruciate ligament tension when compared to conventional surgery.

These studies have shown that robotic-assisted surgery is accurate in controlling surgical variables, such as mechanical lower leg alignment, maintaining joint-line, implant positioning, and soft tissue balancing. Furthermore, these studies have shown that controlling these variables is better than the current gold standard of manual knee arthroplasty. Until now, not many studies have assessed survivorship of robotic-assisted surgery. Furthermore, no studies have, to our knowledge, compared survivorship of robotic-assisted with conventional knee replacement surgery. Finally, studies comparing functional outcomes following robotic-assisted surgery and conventional knee arthroplasty surgery are frequently underpowered due to their small sample sizes.68,70 Since many studies have shown that the surgical variables are more tightly controlled using robotic-assisted surgery when compared to conventional surgery, large comparative studies are necessary to assess the role of robotic-assisted surgery in functional outcomes and survivorship of UKA and TKA.

Cost-Effectiveness of Robotic-Assisted Surgery