User login

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

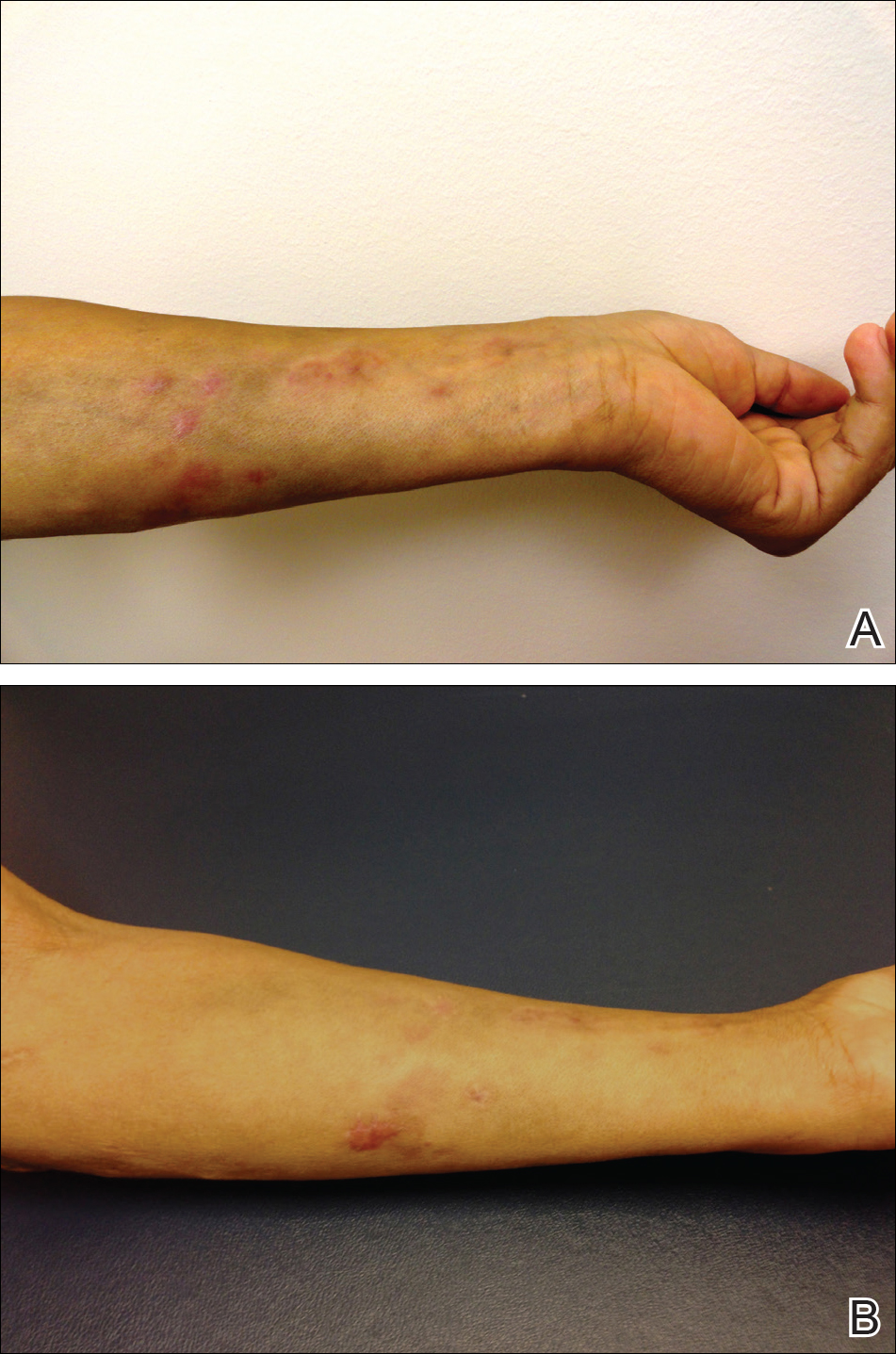

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

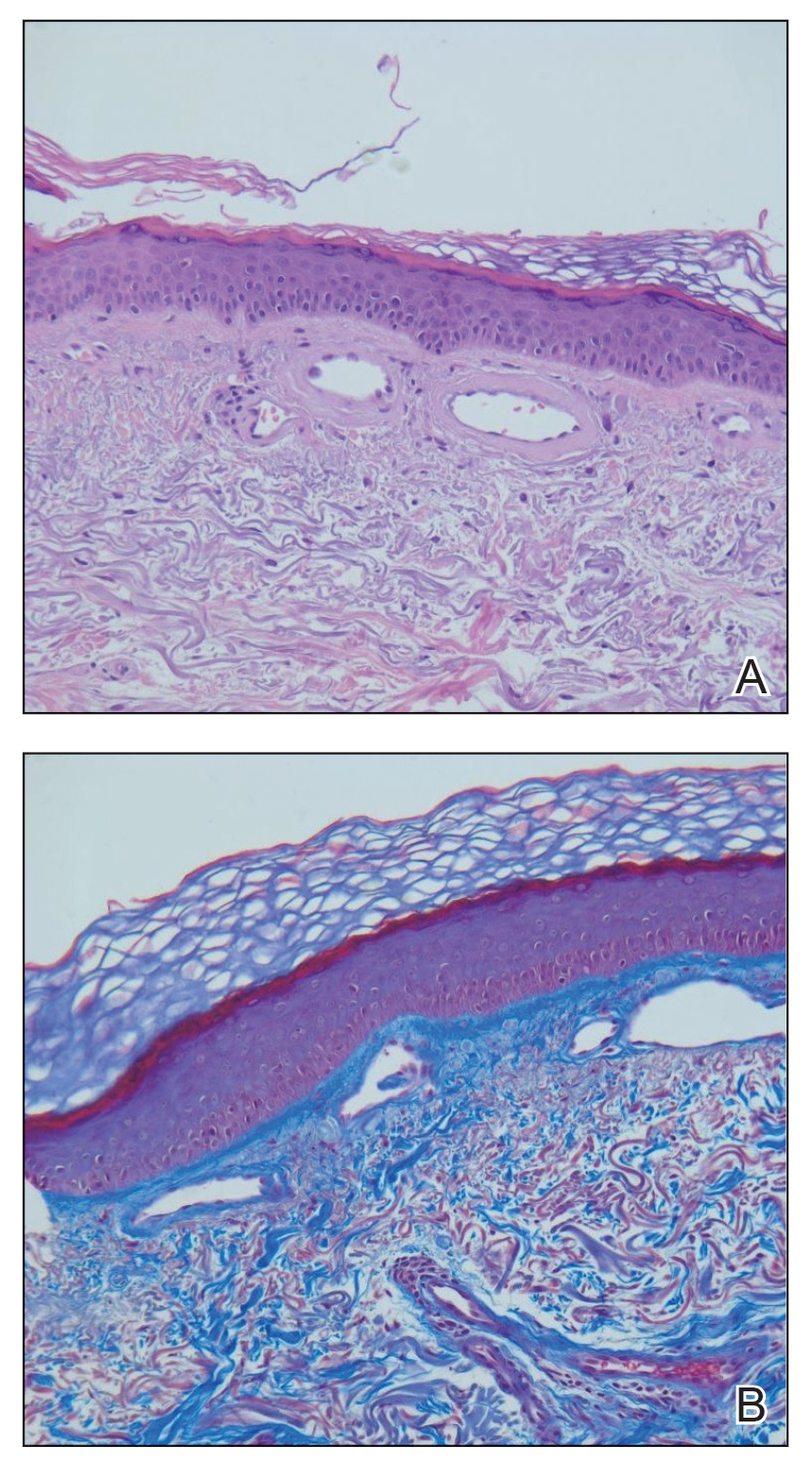

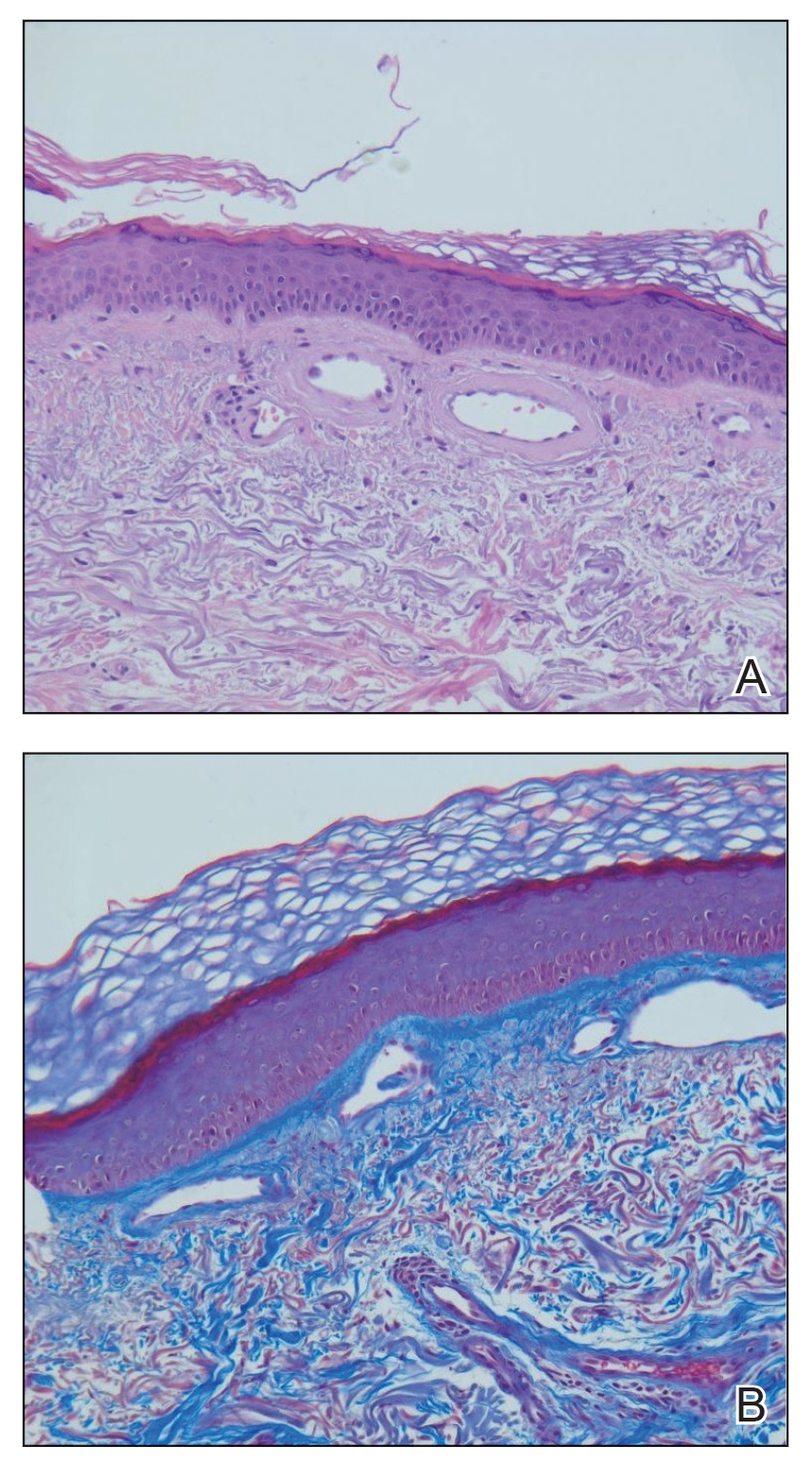

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) should be in the differential diagnosis of widespread telangiectases.

- Biopsy is needed to differentiate between CCV and generalized essential telangiectasia because of their similar clinical features.

- There may be underlying comorbidities associated with CCV, but the exact cause of the condition has yet to be found.

Sporotrichoid Pattern of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus Infection

To the Editor:

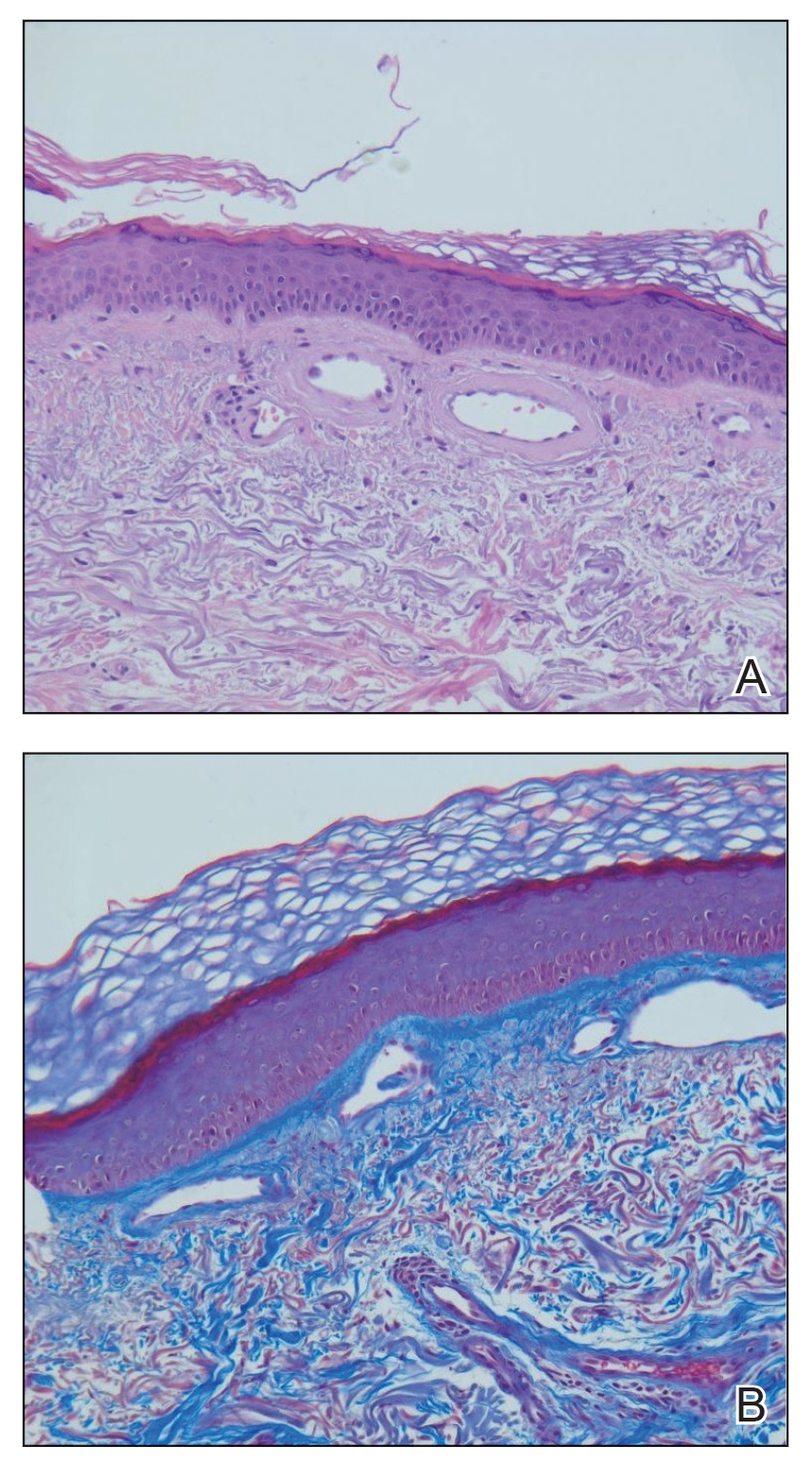

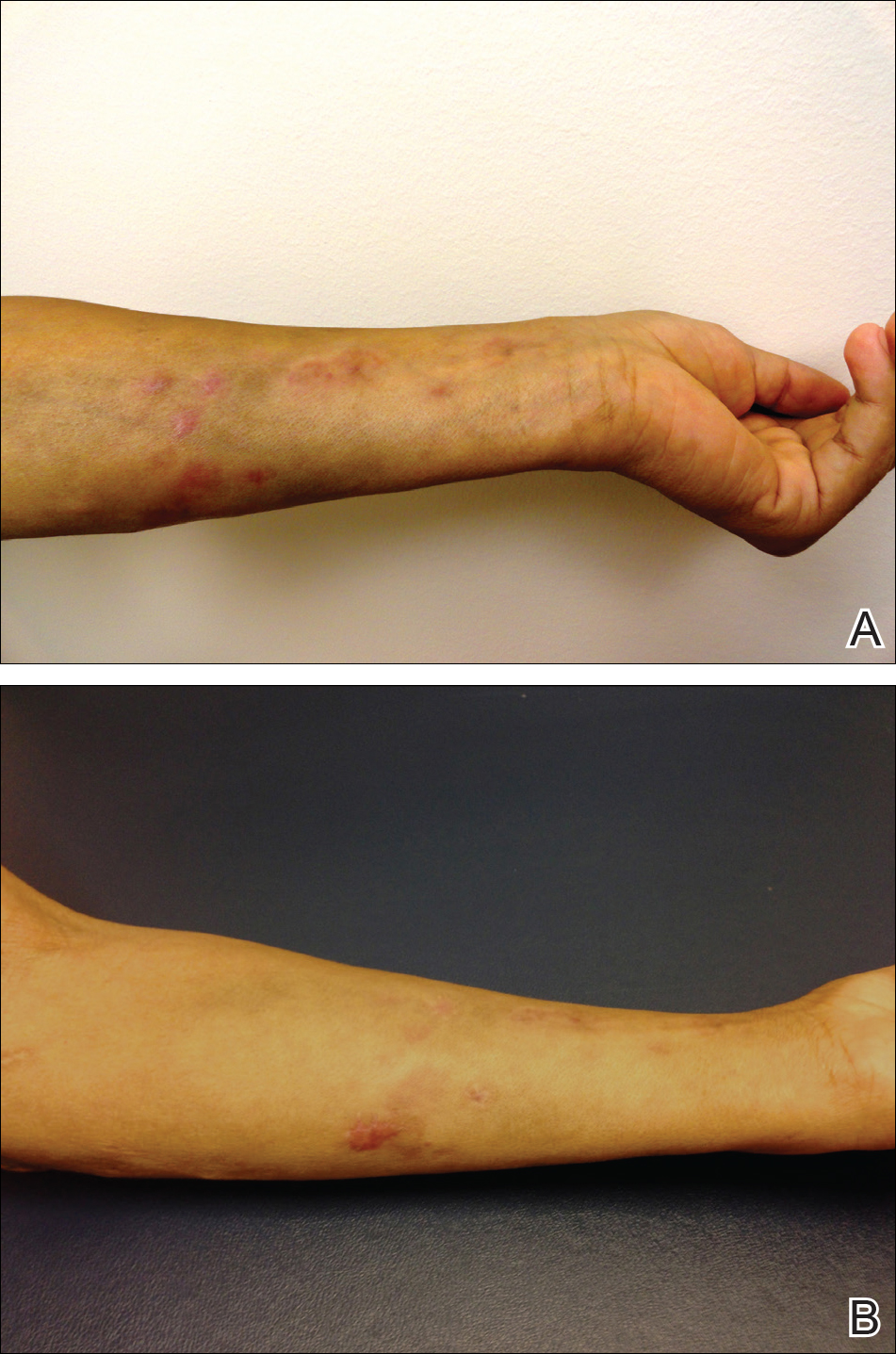

We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern, a rare presentation most often found in immunocompromised patients. A 34-year-old man with lupus nephritis who was taking oral prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine presented with multiple erythematous fluctuant nodules and plaques on the left volar forearm in a sporotrichoid pattern of 3 months’ duration (Figure, A). He denied recent travel, exposure to fish or fish tanks, and penetrating wounds. Punch biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and scarring with negative tissue cultures. Repeat biopsies and cultures were obtained when the lesions increased in number over 2 months.

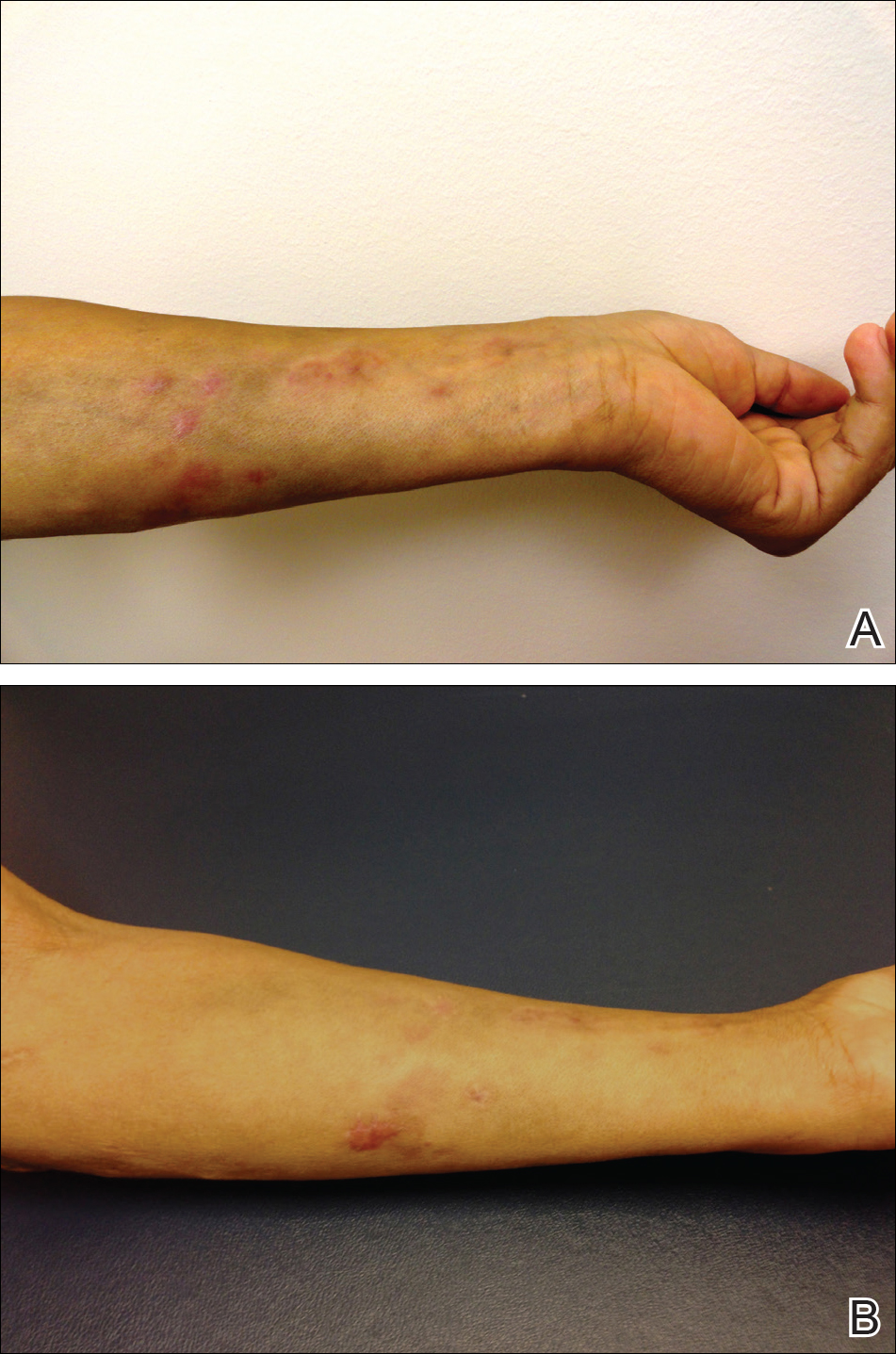

Final biopsy showed upper dermal granulomatous inflammation with karyorrhectic debris, suggesting infection, and acid-fast bacilli. Culture grew M chelonae-abscessus on Löwenstein-Jensen agar at 37°C and blood culture media from which the complex was identified using high-performance liquid chromatography. Empiric therapy with renal dosing based on the Infectious Diseases Society of America statement of susceptibilities1 was initiated with clarithromycin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin for 4 months. Furthermore, the prednisone dose was tapered to 7.5 mg daily. Two months later, the lesions regressed and ciprofloxacin was discontinued (Figure, B).

The sporotrichoid spread of nodules suggests infection with mycobacteria, Sporothrix schenckii, Leishmania, Francisella tularensis, or Nocardia. Most cultures for nontuberculous mycobacteria will grow on Löwenstein-Jensen agar between 28°C and 37°C. Runyon rapidly growing (group IV) mycobacteria are defined by their ubiquitous presence in the environment and ability to develop colonies in 7 days.2 Cutaneous infections are increasing in prevalence, as reported in a retrospective study spanning nearly 30 years.3 The presentation is variable but often includes the distal extremities and usually is a nodule, ulcer, or abscess at a single site; a sporotrichoid pattern is more rare. Preceding skin trauma is the major risk factor for immunocompetent hosts, and the infection can spontaneously resolve in 8 to 12 months.1 In contrast, immunosuppressed patients may have no known source of infection and often have a progressive course with an increasing number of lesions and increased time until clearance.4

It is difficult to differentiate M chelonae and M abscessus based on growth characteristics, and they share the same 16S ribosomal RNA sequence commonly used to differentiate other mycobacterial species.2 Mycobacterium abscessus can be more difficult to treat, thus distinction via polymerase chain reaction of the heat-shock protein 65 gene, hsp65, can be valuable in cases recalcitrant to initial therapy.1

The likelihood of M chelonae and M abscessus isolates to be initially sensitive to clarithromycin is 100%,1 and this antibiotic remains the cornerstone of therapy. A clinical trial of treatments for M chelonae-abscessus found that clarithromycin monotherapy can be successful or complicated by resistance5; therefore, multidrug therapy is recommended. The antibiotic regimen for our patient was chosen to limit renal toxicity.

In summary, we report a case of M chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern in a patient with lupus nephritis on immunosuppressive drugs. As the incidence of rapidly growing mycobacterial cutaneous infections rises, dermatologists must be aware of this pattern of infection.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections due to rapidly-growing Mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1756-1763.

- Wentworth AB, Drage LA, Wengenack NL, et al. Increased incidence of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, 1980 to 2009: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:38-45.

- Lee WJ, Kang SM, Sung H, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Dermatol. 2010:37:965-972.

- Wallace RJ, Tanner D, Brennan PJ, et al. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:482-486.

To the Editor:

We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern, a rare presentation most often found in immunocompromised patients. A 34-year-old man with lupus nephritis who was taking oral prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine presented with multiple erythematous fluctuant nodules and plaques on the left volar forearm in a sporotrichoid pattern of 3 months’ duration (Figure, A). He denied recent travel, exposure to fish or fish tanks, and penetrating wounds. Punch biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and scarring with negative tissue cultures. Repeat biopsies and cultures were obtained when the lesions increased in number over 2 months.

Final biopsy showed upper dermal granulomatous inflammation with karyorrhectic debris, suggesting infection, and acid-fast bacilli. Culture grew M chelonae-abscessus on Löwenstein-Jensen agar at 37°C and blood culture media from which the complex was identified using high-performance liquid chromatography. Empiric therapy with renal dosing based on the Infectious Diseases Society of America statement of susceptibilities1 was initiated with clarithromycin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin for 4 months. Furthermore, the prednisone dose was tapered to 7.5 mg daily. Two months later, the lesions regressed and ciprofloxacin was discontinued (Figure, B).

The sporotrichoid spread of nodules suggests infection with mycobacteria, Sporothrix schenckii, Leishmania, Francisella tularensis, or Nocardia. Most cultures for nontuberculous mycobacteria will grow on Löwenstein-Jensen agar between 28°C and 37°C. Runyon rapidly growing (group IV) mycobacteria are defined by their ubiquitous presence in the environment and ability to develop colonies in 7 days.2 Cutaneous infections are increasing in prevalence, as reported in a retrospective study spanning nearly 30 years.3 The presentation is variable but often includes the distal extremities and usually is a nodule, ulcer, or abscess at a single site; a sporotrichoid pattern is more rare. Preceding skin trauma is the major risk factor for immunocompetent hosts, and the infection can spontaneously resolve in 8 to 12 months.1 In contrast, immunosuppressed patients may have no known source of infection and often have a progressive course with an increasing number of lesions and increased time until clearance.4

It is difficult to differentiate M chelonae and M abscessus based on growth characteristics, and they share the same 16S ribosomal RNA sequence commonly used to differentiate other mycobacterial species.2 Mycobacterium abscessus can be more difficult to treat, thus distinction via polymerase chain reaction of the heat-shock protein 65 gene, hsp65, can be valuable in cases recalcitrant to initial therapy.1

The likelihood of M chelonae and M abscessus isolates to be initially sensitive to clarithromycin is 100%,1 and this antibiotic remains the cornerstone of therapy. A clinical trial of treatments for M chelonae-abscessus found that clarithromycin monotherapy can be successful or complicated by resistance5; therefore, multidrug therapy is recommended. The antibiotic regimen for our patient was chosen to limit renal toxicity.

In summary, we report a case of M chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern in a patient with lupus nephritis on immunosuppressive drugs. As the incidence of rapidly growing mycobacterial cutaneous infections rises, dermatologists must be aware of this pattern of infection.

To the Editor:

We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern, a rare presentation most often found in immunocompromised patients. A 34-year-old man with lupus nephritis who was taking oral prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine presented with multiple erythematous fluctuant nodules and plaques on the left volar forearm in a sporotrichoid pattern of 3 months’ duration (Figure, A). He denied recent travel, exposure to fish or fish tanks, and penetrating wounds. Punch biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and scarring with negative tissue cultures. Repeat biopsies and cultures were obtained when the lesions increased in number over 2 months.

Final biopsy showed upper dermal granulomatous inflammation with karyorrhectic debris, suggesting infection, and acid-fast bacilli. Culture grew M chelonae-abscessus on Löwenstein-Jensen agar at 37°C and blood culture media from which the complex was identified using high-performance liquid chromatography. Empiric therapy with renal dosing based on the Infectious Diseases Society of America statement of susceptibilities1 was initiated with clarithromycin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin for 4 months. Furthermore, the prednisone dose was tapered to 7.5 mg daily. Two months later, the lesions regressed and ciprofloxacin was discontinued (Figure, B).

The sporotrichoid spread of nodules suggests infection with mycobacteria, Sporothrix schenckii, Leishmania, Francisella tularensis, or Nocardia. Most cultures for nontuberculous mycobacteria will grow on Löwenstein-Jensen agar between 28°C and 37°C. Runyon rapidly growing (group IV) mycobacteria are defined by their ubiquitous presence in the environment and ability to develop colonies in 7 days.2 Cutaneous infections are increasing in prevalence, as reported in a retrospective study spanning nearly 30 years.3 The presentation is variable but often includes the distal extremities and usually is a nodule, ulcer, or abscess at a single site; a sporotrichoid pattern is more rare. Preceding skin trauma is the major risk factor for immunocompetent hosts, and the infection can spontaneously resolve in 8 to 12 months.1 In contrast, immunosuppressed patients may have no known source of infection and often have a progressive course with an increasing number of lesions and increased time until clearance.4

It is difficult to differentiate M chelonae and M abscessus based on growth characteristics, and they share the same 16S ribosomal RNA sequence commonly used to differentiate other mycobacterial species.2 Mycobacterium abscessus can be more difficult to treat, thus distinction via polymerase chain reaction of the heat-shock protein 65 gene, hsp65, can be valuable in cases recalcitrant to initial therapy.1

The likelihood of M chelonae and M abscessus isolates to be initially sensitive to clarithromycin is 100%,1 and this antibiotic remains the cornerstone of therapy. A clinical trial of treatments for M chelonae-abscessus found that clarithromycin monotherapy can be successful or complicated by resistance5; therefore, multidrug therapy is recommended. The antibiotic regimen for our patient was chosen to limit renal toxicity.

In summary, we report a case of M chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern in a patient with lupus nephritis on immunosuppressive drugs. As the incidence of rapidly growing mycobacterial cutaneous infections rises, dermatologists must be aware of this pattern of infection.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections due to rapidly-growing Mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1756-1763.

- Wentworth AB, Drage LA, Wengenack NL, et al. Increased incidence of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, 1980 to 2009: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:38-45.

- Lee WJ, Kang SM, Sung H, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Dermatol. 2010:37:965-972.

- Wallace RJ, Tanner D, Brennan PJ, et al. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:482-486.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections due to rapidly-growing Mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1756-1763.

- Wentworth AB, Drage LA, Wengenack NL, et al. Increased incidence of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, 1980 to 2009: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:38-45.

- Lee WJ, Kang SM, Sung H, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Dermatol. 2010:37:965-972.

- Wallace RJ, Tanner D, Brennan PJ, et al. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:482-486.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should consider atypical mycobacterial infections, including rapidly growing mycobacteria, in the differential diagnosis for lesions with sporotrichoid-pattern spread.

- Multidrug therapy often is required for treatment of infection caused by Mycobacteria chelonae-abscessus complex.