User login

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

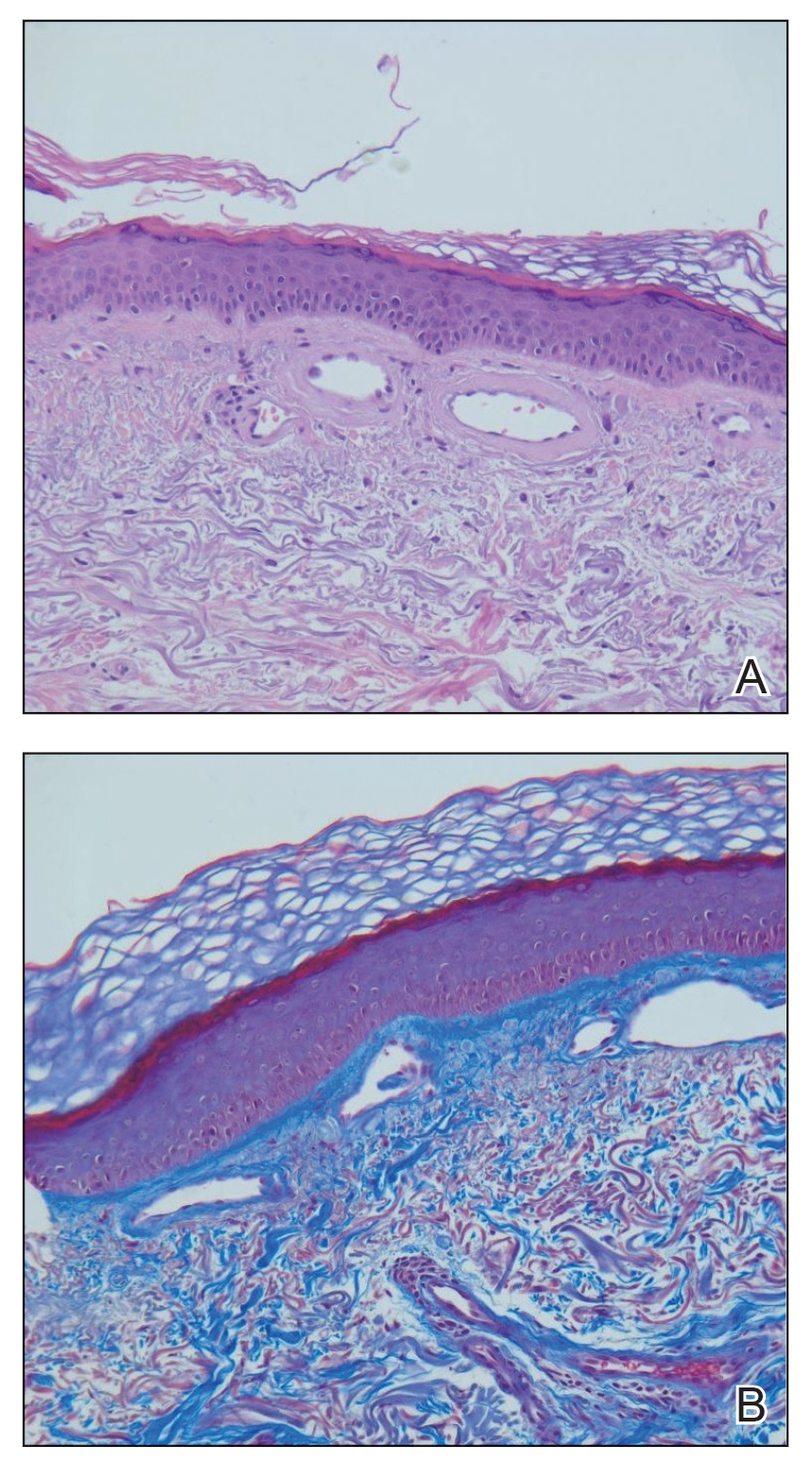

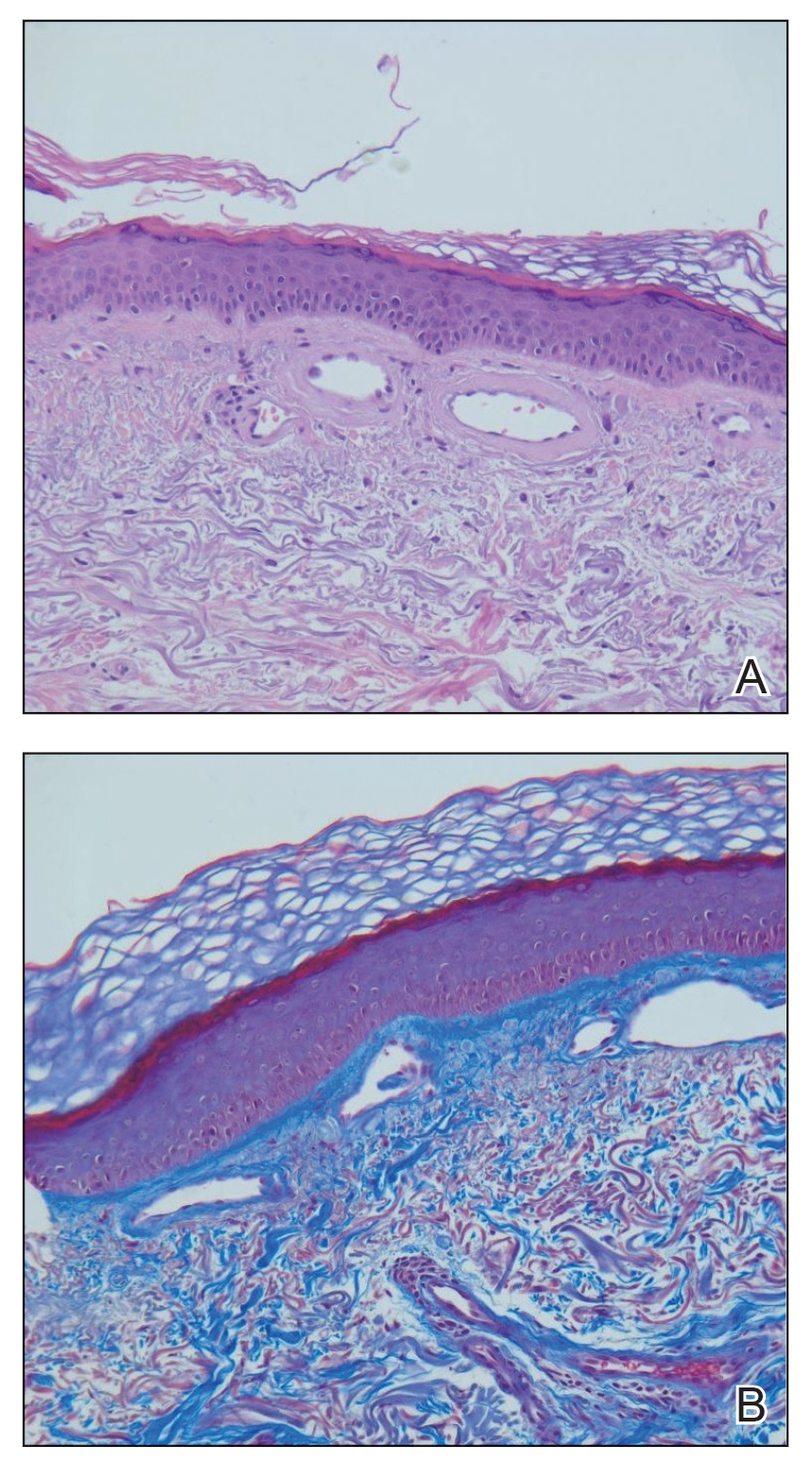

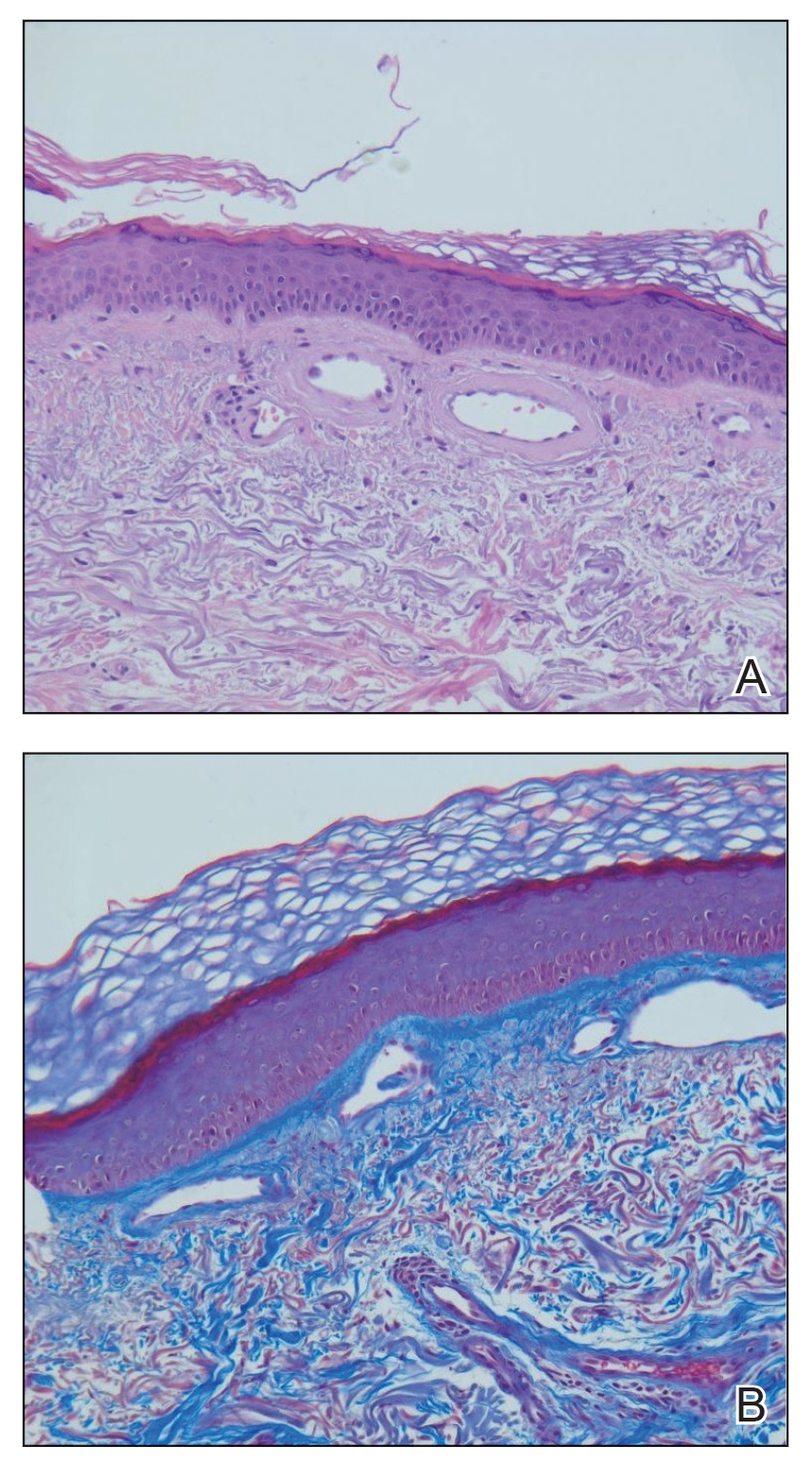

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) should be in the differential diagnosis of widespread telangiectases.

- Biopsy is needed to differentiate between CCV and generalized essential telangiectasia because of their similar clinical features.

- There may be underlying comorbidities associated with CCV, but the exact cause of the condition has yet to be found.

Acute Serpiginous Rash

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Three punch biopsies were obtained. Spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils was seen. There was a single specimen of tissue that showed a possible intraepidermal larva with a tract in the epidermis. The differential diagnosis included allergic contact dermatitis and arthropod bite eruption, among others, but clinical correlation made cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) the likely diagnosis.

The patient was treated empirically with albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 days. In addition, he was prescribed triamcinolone for symptomatic relief and remained asymptomatic for 8 weeks at which time he presented again to the dermatology clinic with a similar rash in the same distribution. He was treated with a repeat course of albendazole and further educated on the etiology of the infection. The patient has not exhibited a recurrence after treatment of the second episode of CLM.

Cutaneous larva migrans is a dermatosis of the skin caused by the larvae of parasitic nematodes from the hookworm family, most commonly Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliense.1,2 These hookworms thrive in warm moist climates and are most frequently found in tropical coastal regions. They normally inhabit the intestines of animals such as dogs and cats and are transmitted to soil and sand via feces. Humans become accidental hosts through contact with the contaminated sand or soil3; however, the larvae are unable to penetrate deeper than the upper dermis of the skin in humans, subsequently limiting the infection. Because humans are accidental hosts, the larvae are unable to complete their life cycle and larval death occurs within weeks to months after the initial infection3; thus treatment may be unnecessary unless complications arise.

Cutaneous larva migrans is most commonly observed in travelers or inhabitants of tropical coastal regions but can occur anywhere in the world.1 Clinically, CLM presents as an enlarging, intensely pruritic, erythematous linear or serpiginous tract,3 most commonly on the hands, feet, abdomen, and buttocks.1 Complications may include allergic reactions, secondary bacterial infections, and hookworm folliculitis.4 Although rare, migration to the intestinal tract5 and/or hematological spread with Löffler syndrome has been described.6 Although this dermatological disease has been well described in the medical literature, it is not well recognized by Western physicians and is consequently either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.4 Although the infection is usually self-limiting without treatment, the risk for prolonged active disease may occur, with 1 reported case lasting up to 18 months.4,5 The first indicator of CLM is intense pruritus localized to the site of infection.4 As the larvae migrate or creep, they create a lesion that may appear edematous with vesiculobullous lesions that are either serpiginous or linear.4 The differential diagnosis may include fungal infection, bacterial infection, and atypical herpes simplex infections; however, the key finding in CLM is the presence of undulating tracts localized to the borders of the lesion.2 Patients may report experiencing a stinging sensation prior to the formation of the erythematous scaly papule,5 which is attributed to the initial penetration of the larva into the skin. This development, accompanied with a history of travel to tropical or subtropical regions, should elicit CLM as a likely diagnosis. Because hookworms are a type of helminth, they likely elicit an eosinophilic immune response and thus peripheral eosinophilia may be present.5

Effective treatment of CLM is accomplished with oral albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 to 7 days.2,7 Alternatively, oral ivermectin, topical thiabendazole, and cryosurgery can be used,2 though albendazole currently is the preferred treatment of CLM.7

- Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM, et al. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:799-807.

- Roest MA, Ratnavel R. Cutaneous larva migrans contracted in England: a reminder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:389-390.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:434-437.

- Hochedez P, Caumes E. Hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. J Travel Med. 2007;14:326-333.

- Bravo F, Sanchez MR. New and re-emerging cutaneous infectious diseases in Latin America and other geographic areas. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:655-668, viii.

- Guill MA, Odom RB. Larva migrans complicated by Loeffler’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1525-1526.

- Caumes E. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:811-814.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Three punch biopsies were obtained. Spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils was seen. There was a single specimen of tissue that showed a possible intraepidermal larva with a tract in the epidermis. The differential diagnosis included allergic contact dermatitis and arthropod bite eruption, among others, but clinical correlation made cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) the likely diagnosis.

The patient was treated empirically with albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 days. In addition, he was prescribed triamcinolone for symptomatic relief and remained asymptomatic for 8 weeks at which time he presented again to the dermatology clinic with a similar rash in the same distribution. He was treated with a repeat course of albendazole and further educated on the etiology of the infection. The patient has not exhibited a recurrence after treatment of the second episode of CLM.

Cutaneous larva migrans is a dermatosis of the skin caused by the larvae of parasitic nematodes from the hookworm family, most commonly Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliense.1,2 These hookworms thrive in warm moist climates and are most frequently found in tropical coastal regions. They normally inhabit the intestines of animals such as dogs and cats and are transmitted to soil and sand via feces. Humans become accidental hosts through contact with the contaminated sand or soil3; however, the larvae are unable to penetrate deeper than the upper dermis of the skin in humans, subsequently limiting the infection. Because humans are accidental hosts, the larvae are unable to complete their life cycle and larval death occurs within weeks to months after the initial infection3; thus treatment may be unnecessary unless complications arise.

Cutaneous larva migrans is most commonly observed in travelers or inhabitants of tropical coastal regions but can occur anywhere in the world.1 Clinically, CLM presents as an enlarging, intensely pruritic, erythematous linear or serpiginous tract,3 most commonly on the hands, feet, abdomen, and buttocks.1 Complications may include allergic reactions, secondary bacterial infections, and hookworm folliculitis.4 Although rare, migration to the intestinal tract5 and/or hematological spread with Löffler syndrome has been described.6 Although this dermatological disease has been well described in the medical literature, it is not well recognized by Western physicians and is consequently either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.4 Although the infection is usually self-limiting without treatment, the risk for prolonged active disease may occur, with 1 reported case lasting up to 18 months.4,5 The first indicator of CLM is intense pruritus localized to the site of infection.4 As the larvae migrate or creep, they create a lesion that may appear edematous with vesiculobullous lesions that are either serpiginous or linear.4 The differential diagnosis may include fungal infection, bacterial infection, and atypical herpes simplex infections; however, the key finding in CLM is the presence of undulating tracts localized to the borders of the lesion.2 Patients may report experiencing a stinging sensation prior to the formation of the erythematous scaly papule,5 which is attributed to the initial penetration of the larva into the skin. This development, accompanied with a history of travel to tropical or subtropical regions, should elicit CLM as a likely diagnosis. Because hookworms are a type of helminth, they likely elicit an eosinophilic immune response and thus peripheral eosinophilia may be present.5

Effective treatment of CLM is accomplished with oral albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 to 7 days.2,7 Alternatively, oral ivermectin, topical thiabendazole, and cryosurgery can be used,2 though albendazole currently is the preferred treatment of CLM.7

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Three punch biopsies were obtained. Spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils was seen. There was a single specimen of tissue that showed a possible intraepidermal larva with a tract in the epidermis. The differential diagnosis included allergic contact dermatitis and arthropod bite eruption, among others, but clinical correlation made cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) the likely diagnosis.

The patient was treated empirically with albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 days. In addition, he was prescribed triamcinolone for symptomatic relief and remained asymptomatic for 8 weeks at which time he presented again to the dermatology clinic with a similar rash in the same distribution. He was treated with a repeat course of albendazole and further educated on the etiology of the infection. The patient has not exhibited a recurrence after treatment of the second episode of CLM.

Cutaneous larva migrans is a dermatosis of the skin caused by the larvae of parasitic nematodes from the hookworm family, most commonly Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliense.1,2 These hookworms thrive in warm moist climates and are most frequently found in tropical coastal regions. They normally inhabit the intestines of animals such as dogs and cats and are transmitted to soil and sand via feces. Humans become accidental hosts through contact with the contaminated sand or soil3; however, the larvae are unable to penetrate deeper than the upper dermis of the skin in humans, subsequently limiting the infection. Because humans are accidental hosts, the larvae are unable to complete their life cycle and larval death occurs within weeks to months after the initial infection3; thus treatment may be unnecessary unless complications arise.

Cutaneous larva migrans is most commonly observed in travelers or inhabitants of tropical coastal regions but can occur anywhere in the world.1 Clinically, CLM presents as an enlarging, intensely pruritic, erythematous linear or serpiginous tract,3 most commonly on the hands, feet, abdomen, and buttocks.1 Complications may include allergic reactions, secondary bacterial infections, and hookworm folliculitis.4 Although rare, migration to the intestinal tract5 and/or hematological spread with Löffler syndrome has been described.6 Although this dermatological disease has been well described in the medical literature, it is not well recognized by Western physicians and is consequently either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.4 Although the infection is usually self-limiting without treatment, the risk for prolonged active disease may occur, with 1 reported case lasting up to 18 months.4,5 The first indicator of CLM is intense pruritus localized to the site of infection.4 As the larvae migrate or creep, they create a lesion that may appear edematous with vesiculobullous lesions that are either serpiginous or linear.4 The differential diagnosis may include fungal infection, bacterial infection, and atypical herpes simplex infections; however, the key finding in CLM is the presence of undulating tracts localized to the borders of the lesion.2 Patients may report experiencing a stinging sensation prior to the formation of the erythematous scaly papule,5 which is attributed to the initial penetration of the larva into the skin. This development, accompanied with a history of travel to tropical or subtropical regions, should elicit CLM as a likely diagnosis. Because hookworms are a type of helminth, they likely elicit an eosinophilic immune response and thus peripheral eosinophilia may be present.5

Effective treatment of CLM is accomplished with oral albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 to 7 days.2,7 Alternatively, oral ivermectin, topical thiabendazole, and cryosurgery can be used,2 though albendazole currently is the preferred treatment of CLM.7

- Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM, et al. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:799-807.

- Roest MA, Ratnavel R. Cutaneous larva migrans contracted in England: a reminder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:389-390.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:434-437.

- Hochedez P, Caumes E. Hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. J Travel Med. 2007;14:326-333.

- Bravo F, Sanchez MR. New and re-emerging cutaneous infectious diseases in Latin America and other geographic areas. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:655-668, viii.

- Guill MA, Odom RB. Larva migrans complicated by Loeffler’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1525-1526.

- Caumes E. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:811-814.

- Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM, et al. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:799-807.

- Roest MA, Ratnavel R. Cutaneous larva migrans contracted in England: a reminder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:389-390.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:434-437.

- Hochedez P, Caumes E. Hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. J Travel Med. 2007;14:326-333.

- Bravo F, Sanchez MR. New and re-emerging cutaneous infectious diseases in Latin America and other geographic areas. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:655-668, viii.

- Guill MA, Odom RB. Larva migrans complicated by Loeffler’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1525-1526.

- Caumes E. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:811-814.

A 62-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a severely pruritic and painful rash of 1 week’s duration. The rash began as an erythematous papule on the right buttock but had spread in a serpiginous manner to the groin and left buttock. The patient stated that he could see the rash spreading in a serpiginous manner over a matter of hours. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable and a review of symptoms was otherwise negative. Physical examination revealed an erythematous serpiginous eruption that was most prominent on the right buttock but extended to the left buttock and down the right leg. He also exhibited several erythematous papules with excoriations in that region.