User login

Eruptive Vellus Hair Cysts in Identical Triplets With Dermoscopic Findings

Case Report

Four-year-old identical triplet girls with numerous asymptomatic scattered papules on the chest of 4 months’ duration were referred to a dermatologist by their pediatrician for molluscum contagiosum. The patients’ father reported that there was no history of trauma, irritation, or manipulation to the affected area. Their medical history was notable for prematurity at 32 weeks’ gestation and congenital dermal melanocytosis. Family history was notable for their father having acne and similar papules on the chest during adolescence that resolved with isotretinoin therapy.

On physical examination there were multiple smooth, hyperpigmented to erythematous, comedonal, 1- to 2-mm papules dispersed on the anterior central chest of all 3 patients (Figure 1). Clinically, these lesions were fairly indistinguishable from other common dermatologic conditions such as acne or milia. Dermoscopic examination revealed homogenous yellow-white areas surrounded by light brown to erythematous halos (Figure 2). Histopathologic examination was not performed given the benign clinical diagnosis and avoidance of biopsy in pediatric populations. Based on dermoscopic features and history, a diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) in identical triplets was made.

Comment

Pathogenesis

Eruptive vellus hair cysts, first introduced by Esterly et al1 in 1977, are uncommon benign lesions presumed to be caused by an abnormal development of the infundibular portion of the hair follicle.2 They are usually 1- to 3-mm, reddish brown, monomorphous papules overlapping with pilosebaceous and apocrine units.3 Although the lesions typically are located on the chest and extremities, they may occur on the face, abdomen, axillae, buttocks, or genital area.1,3 The inheritance of EVHCs is unclear. The majority of reported cases are sporadic; however, the literature mentions 19 families affected by autosomal-dominant EVHCs based on phylogeny.3 In 2015, EVHCs were reported in identical twins, further supporting the case for a genetic mutation.4 We augment this autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern by presenting a case of identical triplets with EVHCs. The patients’ father reported similar lesions in childhood, further underscoring a genetic basis.

The pathogenesis of EVHC is uncertain, with 2 main theories. Some propose retention of vellus hair and keratin in a cavity formed by an abnormal vellus hair follicle causing infundibular occlusion. Others consider the growth of benign follicular hamartomas that differentiate to become vellus hairs.1

Clinical Presentation

The sporadic form of EVHCs is noted to be more common and clinically presents later, with an average age at onset of 16 years and an average age at diagnosis of 24 years.3 The sporadic form occurs without trauma or manipulation as a precursor. Less commonly, lesions present at birth or in early infancy and may show an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with a similar distribution across relatives.3

Other variants of EVHCs have been described. Late-onset EVHC usually occurs at 35 years or older (average age, 57 years), with a female to male predominance of 2.5 to 1.3 This late onset may be attributed to proliferation of ductal follicular keratinocytes or loss of perifollicular elastic fibers exacerbated by exogenous factors such as manipulation, UV rays, or trauma.5

For unilesional EVHC, the average age at diagnosis is 27 years.3 Some of these lesions may be pedunculated and greater than 8 mm. There is a female to male predominance of 2 to 1. Eruptive vellus hair cysts with steatocystoma multiplex can be seen with an average age at onset of 19 years and a female to male predominance of 0.2 to 1. There may be a family history of this subset, as reported in 3 patients with this pattern.3

Diagnosis

The recommended workup for EVHCs varies by patient and age. Eruptive vellus hair cysts present an opportunity to utilize noninvasive diagnostic procedures, especially for the pediatric population, to avoid scarring and pain from manipulation or biopsies. Although many practitioners may comfortably diagnose EVHCs clinically, 6 cases were misdiagnosed as steatocystoma multiplex, keratosis pilaris, or milia prior to histopathology revealing vellus hair cysts.6

Dermoscopy presents as a useful diagnostic aid. Eruptive vellus hair cysts exhibit light yellow homogenous circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.2,7 A central gray-blue color point may be seen due to melanin in the pigmented hair shaft.7 A dermoscopy review of EVHCs reported radiating capillaries.2 Occasionally, nonfollicular homogenous blue pigmentation may be seen due to a connection to atrophic hair follicles in the mid dermis and no normal hair follicle around the cysts.8 In comparison, dermoscopic characteristics of molluscum contagiosum demonstrated a polylobular, white-yellow, amorphous structure at the center with a hardened central umbilicated core and a crown of hairpin vessels at the periphery. Additionally, comedonal acne, commonly mistaken for EVHCs, reveals a brown-yellow hard central plug with sparse inflammation under dermoscopy.2 Thus, differentiation of these entities with dermoscopy should be highly prioritized to better aid in the diagnosis of pediatric dermatologic conditions using painless noninvasive techniques.

Treatment

The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern. Twenty-five percent of EVHCs spontaneously resolve with transepidermal hair elimination or a granulomatous reaction.4,5 A case report of 4 siblings with congenital EVHCs also described a mother with similar lesions that resolved spontaneously in early adulthood,3 as our patients’ father also noted. Treatment modalities including topical keratolytic agents such as urea 10%, retinoic acid 0.05%, tazarotene cream 0.1%, and lactic acid 12%; incision and drainage; CO2 laser; or erbium-doped YAG laser ablation have been tried with minimal improvement.9 Of note, tazarotene cream 0.1% has demonstrated better results than both erbium-doped YAG laser and drainage and incision of EVHCs.4 Additionally, another report evidenced partial improvement with calcipotriene within 2 months with some lesions completely resolved and others flattened, which may be attributed to the antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on the ductal follicular keratinocytes by calcipotriene.5 Lastly, an additional study indicated that isotretinoin and vitamin A derivatives were ineffective for clearing EVHCs.10

Conclusion

We presented 3 identical triplets with the classic pediatric onset and dermoscopic findings of EVHCs on the trunk. Although the definitive diagnosis of EVHCs relies on histopathology, we argue that their unique dermoscopic findings combined with a thorough clinical examination is sufficient to recognize this benign condition and avoid painful procedures in the pediatric population.

- Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pinkus H. Eruptive vellus hair cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:500-503.

- Alfaro-Castellón P, Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Dermoscopy distinction of eruptive vellus hair cysts with molluscum contagiosum and acne lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:772-773.

- Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

- Pauline G, Alain H, Jean-Jaques R, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an original case occurring in twins [published online July 11, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E209-E212.

- Erkek E, Kurtipek GS, Duman D, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: report of a pediatric case with partial response to calcipotriene therapy. Cutis. 2009;84:295-298.

- Shi G, Zhou Y, Cai YX, et al. Clinicopathological features and expression of four keratins (K10, K14, K17 and K19) in six cases of eruptive vellus hair cysts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:496-499.

- Panchaprateep R, Tanus A, Tosti A. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic features of body hair disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:890-900.

- Takada S, Togawa Y, Wakabayashii S, et al. Dermoscopic findings in eruptive vellus hair cysts: a case report. Austin J Dermatol. 2014;1:1004.

- Khatu S, Vasani R, Amin S. Eruptive vellus hair cyst presenting as asymptomatic follicular papules on extremities. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:213-215.

- Urbina-Gonzalez F, Aguilar-Martinez A, Cristobal-Gil M, et al. The treatment of eruptive vellus hair cysts with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:465-466.

Case Report

Four-year-old identical triplet girls with numerous asymptomatic scattered papules on the chest of 4 months’ duration were referred to a dermatologist by their pediatrician for molluscum contagiosum. The patients’ father reported that there was no history of trauma, irritation, or manipulation to the affected area. Their medical history was notable for prematurity at 32 weeks’ gestation and congenital dermal melanocytosis. Family history was notable for their father having acne and similar papules on the chest during adolescence that resolved with isotretinoin therapy.

On physical examination there were multiple smooth, hyperpigmented to erythematous, comedonal, 1- to 2-mm papules dispersed on the anterior central chest of all 3 patients (Figure 1). Clinically, these lesions were fairly indistinguishable from other common dermatologic conditions such as acne or milia. Dermoscopic examination revealed homogenous yellow-white areas surrounded by light brown to erythematous halos (Figure 2). Histopathologic examination was not performed given the benign clinical diagnosis and avoidance of biopsy in pediatric populations. Based on dermoscopic features and history, a diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) in identical triplets was made.

Comment

Pathogenesis

Eruptive vellus hair cysts, first introduced by Esterly et al1 in 1977, are uncommon benign lesions presumed to be caused by an abnormal development of the infundibular portion of the hair follicle.2 They are usually 1- to 3-mm, reddish brown, monomorphous papules overlapping with pilosebaceous and apocrine units.3 Although the lesions typically are located on the chest and extremities, they may occur on the face, abdomen, axillae, buttocks, or genital area.1,3 The inheritance of EVHCs is unclear. The majority of reported cases are sporadic; however, the literature mentions 19 families affected by autosomal-dominant EVHCs based on phylogeny.3 In 2015, EVHCs were reported in identical twins, further supporting the case for a genetic mutation.4 We augment this autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern by presenting a case of identical triplets with EVHCs. The patients’ father reported similar lesions in childhood, further underscoring a genetic basis.

The pathogenesis of EVHC is uncertain, with 2 main theories. Some propose retention of vellus hair and keratin in a cavity formed by an abnormal vellus hair follicle causing infundibular occlusion. Others consider the growth of benign follicular hamartomas that differentiate to become vellus hairs.1

Clinical Presentation

The sporadic form of EVHCs is noted to be more common and clinically presents later, with an average age at onset of 16 years and an average age at diagnosis of 24 years.3 The sporadic form occurs without trauma or manipulation as a precursor. Less commonly, lesions present at birth or in early infancy and may show an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with a similar distribution across relatives.3

Other variants of EVHCs have been described. Late-onset EVHC usually occurs at 35 years or older (average age, 57 years), with a female to male predominance of 2.5 to 1.3 This late onset may be attributed to proliferation of ductal follicular keratinocytes or loss of perifollicular elastic fibers exacerbated by exogenous factors such as manipulation, UV rays, or trauma.5

For unilesional EVHC, the average age at diagnosis is 27 years.3 Some of these lesions may be pedunculated and greater than 8 mm. There is a female to male predominance of 2 to 1. Eruptive vellus hair cysts with steatocystoma multiplex can be seen with an average age at onset of 19 years and a female to male predominance of 0.2 to 1. There may be a family history of this subset, as reported in 3 patients with this pattern.3

Diagnosis

The recommended workup for EVHCs varies by patient and age. Eruptive vellus hair cysts present an opportunity to utilize noninvasive diagnostic procedures, especially for the pediatric population, to avoid scarring and pain from manipulation or biopsies. Although many practitioners may comfortably diagnose EVHCs clinically, 6 cases were misdiagnosed as steatocystoma multiplex, keratosis pilaris, or milia prior to histopathology revealing vellus hair cysts.6

Dermoscopy presents as a useful diagnostic aid. Eruptive vellus hair cysts exhibit light yellow homogenous circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.2,7 A central gray-blue color point may be seen due to melanin in the pigmented hair shaft.7 A dermoscopy review of EVHCs reported radiating capillaries.2 Occasionally, nonfollicular homogenous blue pigmentation may be seen due to a connection to atrophic hair follicles in the mid dermis and no normal hair follicle around the cysts.8 In comparison, dermoscopic characteristics of molluscum contagiosum demonstrated a polylobular, white-yellow, amorphous structure at the center with a hardened central umbilicated core and a crown of hairpin vessels at the periphery. Additionally, comedonal acne, commonly mistaken for EVHCs, reveals a brown-yellow hard central plug with sparse inflammation under dermoscopy.2 Thus, differentiation of these entities with dermoscopy should be highly prioritized to better aid in the diagnosis of pediatric dermatologic conditions using painless noninvasive techniques.

Treatment

The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern. Twenty-five percent of EVHCs spontaneously resolve with transepidermal hair elimination or a granulomatous reaction.4,5 A case report of 4 siblings with congenital EVHCs also described a mother with similar lesions that resolved spontaneously in early adulthood,3 as our patients’ father also noted. Treatment modalities including topical keratolytic agents such as urea 10%, retinoic acid 0.05%, tazarotene cream 0.1%, and lactic acid 12%; incision and drainage; CO2 laser; or erbium-doped YAG laser ablation have been tried with minimal improvement.9 Of note, tazarotene cream 0.1% has demonstrated better results than both erbium-doped YAG laser and drainage and incision of EVHCs.4 Additionally, another report evidenced partial improvement with calcipotriene within 2 months with some lesions completely resolved and others flattened, which may be attributed to the antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on the ductal follicular keratinocytes by calcipotriene.5 Lastly, an additional study indicated that isotretinoin and vitamin A derivatives were ineffective for clearing EVHCs.10

Conclusion

We presented 3 identical triplets with the classic pediatric onset and dermoscopic findings of EVHCs on the trunk. Although the definitive diagnosis of EVHCs relies on histopathology, we argue that their unique dermoscopic findings combined with a thorough clinical examination is sufficient to recognize this benign condition and avoid painful procedures in the pediatric population.

Case Report

Four-year-old identical triplet girls with numerous asymptomatic scattered papules on the chest of 4 months’ duration were referred to a dermatologist by their pediatrician for molluscum contagiosum. The patients’ father reported that there was no history of trauma, irritation, or manipulation to the affected area. Their medical history was notable for prematurity at 32 weeks’ gestation and congenital dermal melanocytosis. Family history was notable for their father having acne and similar papules on the chest during adolescence that resolved with isotretinoin therapy.

On physical examination there were multiple smooth, hyperpigmented to erythematous, comedonal, 1- to 2-mm papules dispersed on the anterior central chest of all 3 patients (Figure 1). Clinically, these lesions were fairly indistinguishable from other common dermatologic conditions such as acne or milia. Dermoscopic examination revealed homogenous yellow-white areas surrounded by light brown to erythematous halos (Figure 2). Histopathologic examination was not performed given the benign clinical diagnosis and avoidance of biopsy in pediatric populations. Based on dermoscopic features and history, a diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) in identical triplets was made.

Comment

Pathogenesis

Eruptive vellus hair cysts, first introduced by Esterly et al1 in 1977, are uncommon benign lesions presumed to be caused by an abnormal development of the infundibular portion of the hair follicle.2 They are usually 1- to 3-mm, reddish brown, monomorphous papules overlapping with pilosebaceous and apocrine units.3 Although the lesions typically are located on the chest and extremities, they may occur on the face, abdomen, axillae, buttocks, or genital area.1,3 The inheritance of EVHCs is unclear. The majority of reported cases are sporadic; however, the literature mentions 19 families affected by autosomal-dominant EVHCs based on phylogeny.3 In 2015, EVHCs were reported in identical twins, further supporting the case for a genetic mutation.4 We augment this autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern by presenting a case of identical triplets with EVHCs. The patients’ father reported similar lesions in childhood, further underscoring a genetic basis.

The pathogenesis of EVHC is uncertain, with 2 main theories. Some propose retention of vellus hair and keratin in a cavity formed by an abnormal vellus hair follicle causing infundibular occlusion. Others consider the growth of benign follicular hamartomas that differentiate to become vellus hairs.1

Clinical Presentation

The sporadic form of EVHCs is noted to be more common and clinically presents later, with an average age at onset of 16 years and an average age at diagnosis of 24 years.3 The sporadic form occurs without trauma or manipulation as a precursor. Less commonly, lesions present at birth or in early infancy and may show an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with a similar distribution across relatives.3

Other variants of EVHCs have been described. Late-onset EVHC usually occurs at 35 years or older (average age, 57 years), with a female to male predominance of 2.5 to 1.3 This late onset may be attributed to proliferation of ductal follicular keratinocytes or loss of perifollicular elastic fibers exacerbated by exogenous factors such as manipulation, UV rays, or trauma.5

For unilesional EVHC, the average age at diagnosis is 27 years.3 Some of these lesions may be pedunculated and greater than 8 mm. There is a female to male predominance of 2 to 1. Eruptive vellus hair cysts with steatocystoma multiplex can be seen with an average age at onset of 19 years and a female to male predominance of 0.2 to 1. There may be a family history of this subset, as reported in 3 patients with this pattern.3

Diagnosis

The recommended workup for EVHCs varies by patient and age. Eruptive vellus hair cysts present an opportunity to utilize noninvasive diagnostic procedures, especially for the pediatric population, to avoid scarring and pain from manipulation or biopsies. Although many practitioners may comfortably diagnose EVHCs clinically, 6 cases were misdiagnosed as steatocystoma multiplex, keratosis pilaris, or milia prior to histopathology revealing vellus hair cysts.6

Dermoscopy presents as a useful diagnostic aid. Eruptive vellus hair cysts exhibit light yellow homogenous circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.2,7 A central gray-blue color point may be seen due to melanin in the pigmented hair shaft.7 A dermoscopy review of EVHCs reported radiating capillaries.2 Occasionally, nonfollicular homogenous blue pigmentation may be seen due to a connection to atrophic hair follicles in the mid dermis and no normal hair follicle around the cysts.8 In comparison, dermoscopic characteristics of molluscum contagiosum demonstrated a polylobular, white-yellow, amorphous structure at the center with a hardened central umbilicated core and a crown of hairpin vessels at the periphery. Additionally, comedonal acne, commonly mistaken for EVHCs, reveals a brown-yellow hard central plug with sparse inflammation under dermoscopy.2 Thus, differentiation of these entities with dermoscopy should be highly prioritized to better aid in the diagnosis of pediatric dermatologic conditions using painless noninvasive techniques.

Treatment

The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern. Twenty-five percent of EVHCs spontaneously resolve with transepidermal hair elimination or a granulomatous reaction.4,5 A case report of 4 siblings with congenital EVHCs also described a mother with similar lesions that resolved spontaneously in early adulthood,3 as our patients’ father also noted. Treatment modalities including topical keratolytic agents such as urea 10%, retinoic acid 0.05%, tazarotene cream 0.1%, and lactic acid 12%; incision and drainage; CO2 laser; or erbium-doped YAG laser ablation have been tried with minimal improvement.9 Of note, tazarotene cream 0.1% has demonstrated better results than both erbium-doped YAG laser and drainage and incision of EVHCs.4 Additionally, another report evidenced partial improvement with calcipotriene within 2 months with some lesions completely resolved and others flattened, which may be attributed to the antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on the ductal follicular keratinocytes by calcipotriene.5 Lastly, an additional study indicated that isotretinoin and vitamin A derivatives were ineffective for clearing EVHCs.10

Conclusion

We presented 3 identical triplets with the classic pediatric onset and dermoscopic findings of EVHCs on the trunk. Although the definitive diagnosis of EVHCs relies on histopathology, we argue that their unique dermoscopic findings combined with a thorough clinical examination is sufficient to recognize this benign condition and avoid painful procedures in the pediatric population.

- Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pinkus H. Eruptive vellus hair cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:500-503.

- Alfaro-Castellón P, Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Dermoscopy distinction of eruptive vellus hair cysts with molluscum contagiosum and acne lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:772-773.

- Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

- Pauline G, Alain H, Jean-Jaques R, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an original case occurring in twins [published online July 11, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E209-E212.

- Erkek E, Kurtipek GS, Duman D, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: report of a pediatric case with partial response to calcipotriene therapy. Cutis. 2009;84:295-298.

- Shi G, Zhou Y, Cai YX, et al. Clinicopathological features and expression of four keratins (K10, K14, K17 and K19) in six cases of eruptive vellus hair cysts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:496-499.

- Panchaprateep R, Tanus A, Tosti A. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic features of body hair disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:890-900.

- Takada S, Togawa Y, Wakabayashii S, et al. Dermoscopic findings in eruptive vellus hair cysts: a case report. Austin J Dermatol. 2014;1:1004.

- Khatu S, Vasani R, Amin S. Eruptive vellus hair cyst presenting as asymptomatic follicular papules on extremities. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:213-215.

- Urbina-Gonzalez F, Aguilar-Martinez A, Cristobal-Gil M, et al. The treatment of eruptive vellus hair cysts with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:465-466.

- Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pinkus H. Eruptive vellus hair cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:500-503.

- Alfaro-Castellón P, Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Dermoscopy distinction of eruptive vellus hair cysts with molluscum contagiosum and acne lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:772-773.

- Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

- Pauline G, Alain H, Jean-Jaques R, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an original case occurring in twins [published online July 11, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E209-E212.

- Erkek E, Kurtipek GS, Duman D, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: report of a pediatric case with partial response to calcipotriene therapy. Cutis. 2009;84:295-298.

- Shi G, Zhou Y, Cai YX, et al. Clinicopathological features and expression of four keratins (K10, K14, K17 and K19) in six cases of eruptive vellus hair cysts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:496-499.

- Panchaprateep R, Tanus A, Tosti A. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic features of body hair disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:890-900.

- Takada S, Togawa Y, Wakabayashii S, et al. Dermoscopic findings in eruptive vellus hair cysts: a case report. Austin J Dermatol. 2014;1:1004.

- Khatu S, Vasani R, Amin S. Eruptive vellus hair cyst presenting as asymptomatic follicular papules on extremities. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:213-215.

- Urbina-Gonzalez F, Aguilar-Martinez A, Cristobal-Gil M, et al. The treatment of eruptive vellus hair cysts with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:465-466.

Practice Points

- Eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) are 1- to 3-mm round, dome-shaped, flesh-colored, asymptomatic, benign papules typically occurring on the chest and extremities.

- Pathogenesis and inheritance are unclear. Although the majority of EVHC cases are sporadic, the strong influence of genes is indicated by numerous reports of families in whom 2 or more members were affected.

- Dermoscopy is a noninvasive diagnostic procedure that should be utilized to diagnose EVHCs in the pediatric population; specifically, EVHCs exhibit light yellow, homogenous, circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.

- The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern; however, one-quarter of cases may resolve spontaneously.

Pediatric Primary Cutaneous Blastomycosis Clinically Responsive to Itraconazole

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic disease caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is naturally occurring worldwide but particularly prominent in the Great Lakes, Mississippi, and Ohio River areas of the United States. The disease was first described by Thomas Caspar Gilchrist in 1894 and historically has been referred to as Gilchrist disease, North American blastomycosis, or Chicago disease.1,2 Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin resulting in primary cutaneous disease. Clinically, the lesions are polymorphic and may appear as well-demarcated verrucous plaques containing foci of pustules or ulcerations. Lesions typically heal centrifugally with a cribriform scar.3

We describe an adolescent with a unique history of inoculation 2 weeks prior to the development of a biopsy-confirmed lesion of cutaneous blastomycosis on the left chest wall that clinically resolved following 6 months of itraconazole.

Case Report

A 16-year-old adolescent boy with a history of morbid obesity, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented for evaluation of a painful, slowly enlarging skin lesion on the left chest wall of 2 months’ duration. According to the patient, a “small pimple” appeared at the site of impact 2 weeks following a fall into a muddy flowerbed in Madison, Wisconsin. The patient recalled that although he had soiled his clothing, there was no identifiable puncture of the skin. Despite daily application of hydrogen peroxide and a 1-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the lesion gradually enlarged. Complete review of systems as well as exposure and travel history were otherwise negative.

Physical examination revealed a 5.0×2.5-cm exophytic, firm, well-circumscribed plaque with a papillated crusted surface on the left side of the chest near the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic workup, including complete blood cell count with differential, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus antibody/antigen testing, interferon-gamma release assay, and chest radiograph were all within normal limits.

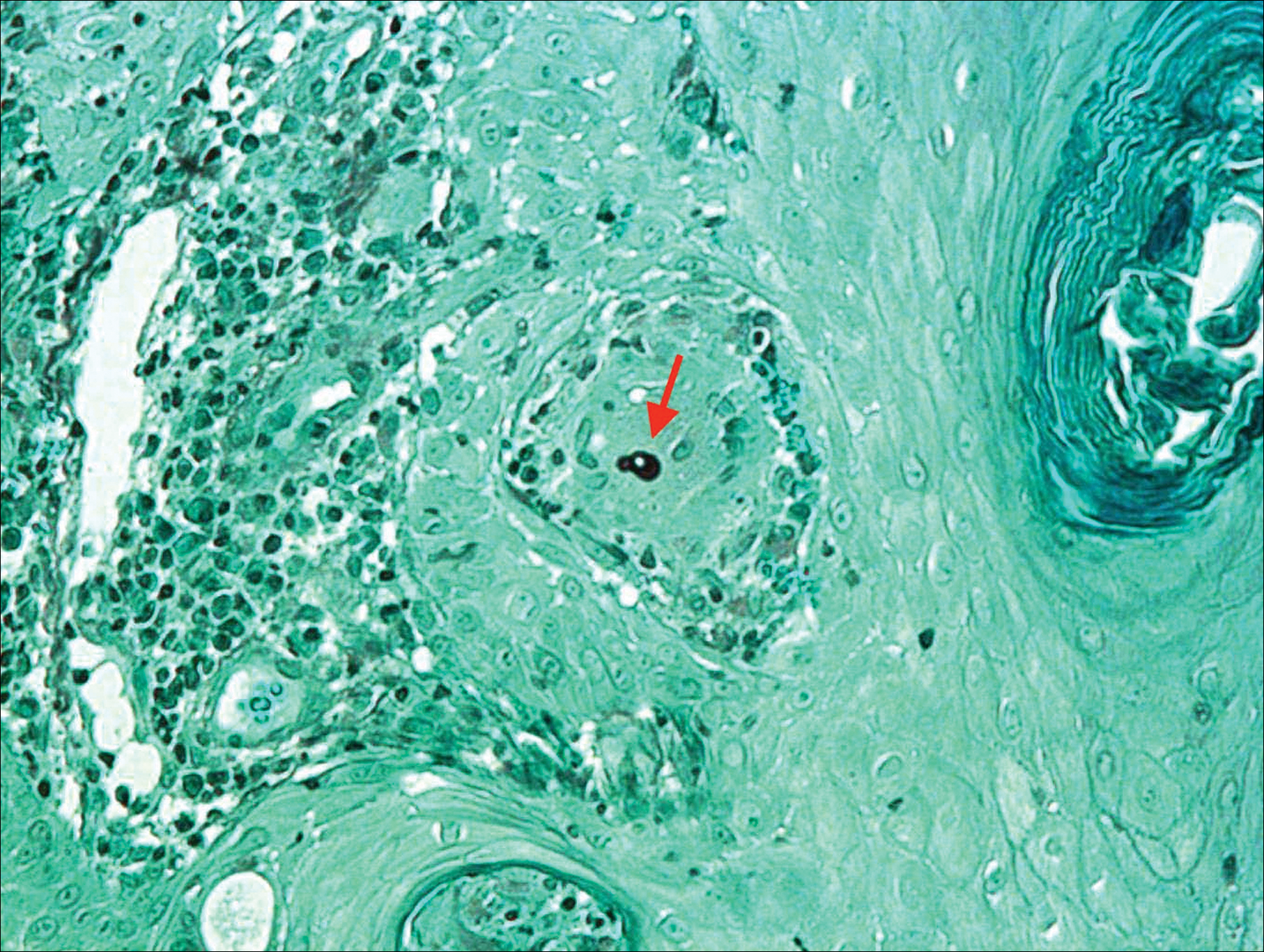

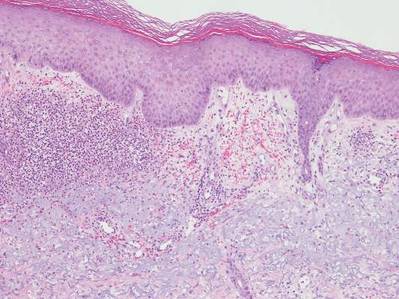

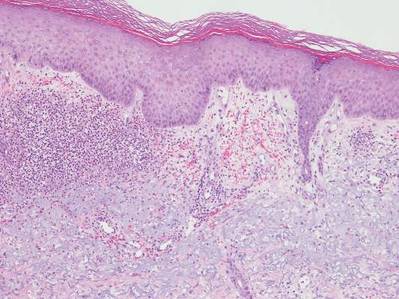

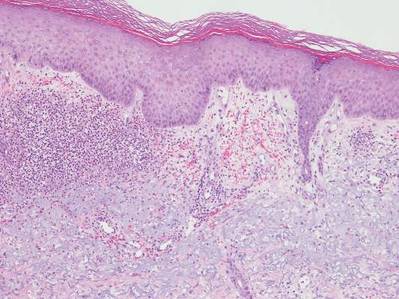

Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with a brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Displayed in Figure 3 is the Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain that highlighted the thick double-contoured wall-budding yeasts.

The patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous blastomycosis. Treatment was initiated with itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg 2 times daily for 6 months. Following 3 months of therapy, the lesion had markedly improved with violaceous dyschromia and no residual surface changes. After 5 months of itraconazole, the patient stopped taking the medication for 2 months due to pharmacy issues and then resumed. After 6 total months of therapy, the lesion healed with only residual dyschromia and itraconazole was discontinued.

Comment

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic pyogranulomatous disease caused by the dimorphic fungus B dermatitidis, naturally occurring in the soil with a worldwide distribution.4 Individuals affected by the disease often reside in locations where the fungus is endemic, specifically in areas that border the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, the Great Lakes, and Canadian provinces near the Saint Lawrence Seaway. More recently there has been an increased incidence of blastomycosis, with the highest proportion found in Wisconsin and Michigan.1,2 Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.1 Despite the ubiquitous presence of B dermatitidis in regions where the species is endemic, it is likely that many individuals who are exposed to the organism do not develop infection.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis for the development of disease in a particular individual remains unclear. Immunosuppression is not a prerequisite for susceptibility, as evidenced by a review of 123 cases of blastomycosis in which a preceding immunodepressive disorder was present in only 25% of patients. The same study found that it was almost equally common as diabetes mellitus and present in 22% of patients.5 The organism is considered a true pathogen given its ability to affect healthy individuals and the presence of a newly identified novel 120-kD glycoprotein antigen (WI-1) on the cell wall that may confer virulence via extracellular matrix and macrophage binding. Intact cell-mediated immunity that prevents the conversion of conidia (the infectious agent) to yeast (the form that exists at body temperature) plays a key role in conferring natural resistance.6,7

Cutaneous infection may occur by either dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic disease or less commonly via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease. With respect to systemic disease, infection occurs through inhalation of conidia from moist soil containing organic debris, with an incubation period of 4 to 6 weeks. In the lungs, in a process largely dependent on host cell-mediated immunity, the mold quickly converts to yeast and may then either multiply or be phagocytized.2,6,7 Transmission does not occur from person to person.7 Asymptomatic infection may occur in at least 50% of patients, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. Symptomatic pulmonary disease may range from mild flulike symptoms to overt pneumonia, clinically indistinguishable from community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and cancer. Of patients with primary pulmonary disease, 25% to 80% have been reported to develop secondary organ involvement via lymphohematogenous spread most commonly to the skin, followed respectively by the skeletal, genitourinary, and central nervous systems. Currently, there are 54 documented cases of secondary disseminated cutaneous blastomycosis in children reported in the literature.3,8-14

Presentation

Primary cutaneous disease resulting from direct cutaneous inoculation is rare, especially among children.14 Of 28 cases of isolated cutaneous blastomycosis reported in the literature, 12 (42%) were pediatric.3,8-21 Inoculation blastomycosis typically presents as a papule that expands to a well-demarcated verrucous plaque, often up to several centimeters in diameter, and is located on the skin at the site of contact. The lesion may exhibit a myriad of features ranging from pustules or nodules to focal ulcerations, either present centrally or within raised borders that ultimately may communicate via sinus tracking.7 Lesions that are purely pustular in morphology also have been reported. Healing typically begins centrally and expands centrifugally, often with cribriform scarring.2,4,22 Histologic features of primary and secondary blastomycosis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal microabscesses, and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation.4 Classically, broad-based budding yeast are identified with a doubly refractile cell wall that is best visualized on periodic acid–Schiff staining.2

Diagnosis

In approximately 50% of patients with cutaneous blastomycosis resulting from secondary spread, there may be an absence of clinically active pulmonary disease, posing a diagnostic dilemma when differentiating from primary cutaneous disease.1,2,4 Furthermore, the skin findings exhibited in primary and secondary cutaneous blastomycosis cannot be distinguished by clinical inspection.19 To fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of primary cutaneous blastomycosis, there must be an identifiable source of infection from the environment, a lesion at the site of contact, a proven absence of systemic infection, and visualization and/or isolation of fungus from the lesion.4,12 The incubation period of lesions is shorter in primary cutaneous disease (2 weeks) and may aid in its differentiation from secondary disease, which typically is longer with lesions presenting 4 to 6 weeks following initial exposure.4

Treatment

Under the current 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, 6 to 12 months of itraconazole is the treatment recommendation for mild to moderate pulmonary systemic disease without central nervous system involvement.7 Central nervous system disease and moderate to severe pulmonary and systemic disease are treated with intravenous amphotericin B followed by 12 months of oral itraconazole.1,7 Primary cutaneous disease, unlike secondary disease, may self-resolve; however, primary cutaneous disease usually is treated with 6 months of itraconazole, though successful therapy with surgical excision, radiation therapy, and incision and drainage have been reported.19

Unlike secondary cutaneous blastomycosis, primary inoculation disease may be self-limited; however, as treatment with antifungal therapy has become the standard of care, the disease’s propensity to self-resolve has not been well studied.4 Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.1,22 Effective treatment duration may be difficult to definitively assess because of the self-limited nature of the disease. Our patient showed marked improvement after 3 months and resolution of the skin lesion following 6 months of itraconazole therapy. Our findings support the previously documented observation that systemic therapy might potentially be needed only for the time required to eliminate the clinical evidence of cutaneous disease.19 Our patient received the full 6 months of treatment according to current guidelines. Among a review of 22 cases of primary inoculation blastomycosis, the 5 patients who were treated with an azole agent alone showed disease clearance with an average treatment course of 3.2 months, ranging from 1 to 6 months.19 Further studies that assess the time to clearance with antifungal therapy and subsequent recurrence rates may be warranted.

Conclusion

Pediatric primary cutaneous blastomycosis is a rare cutaneous disease. Identifying sources of probable inoculation from the environment for this patient was unique in that the patient fell into a muddy puddle within a flowerbed. Given the patient’s atopic history, a predominance of humoral over cell-mediated immunity may have placed him at risk. He responded well to 6 months of oral itraconazole and there was no ulceration or scar formation. An increased awareness of this infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenhua Liu, MD (Libertyville, Illinois), for reviewing the pathology and Pravin Muniyappa, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for referring the case.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Smith JA, Riddell Jt, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:440-449.

- Fisher KR, Baselski V, Beard G, et al. Pustular blastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:355-358.

- Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

- Lemos LB, Baliga M, Guo M. Blastomycosis: the great pretender can also be an opportunist. initial clinical diagnosis and underlying diseases in 123 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:194-203.

- Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21-40, vii.

- Blastomycosis. In: Kimberlin DW, ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:263-264.

- Brick KE, Drolet BA, Lyon VB, et al. Cutaneous and disseminated blastomycosis: a pediatric case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:23-28.

- Fanella S, Skinner S, Trepman E, et al. Blastomycosis in children and adolescents: a 30-year experience from Manitoba. Med Mycol. 2011;49:627-632.

- Frost HM, Anderson J, Ivacic L, et al. Blastomycosis in children: an analysis of clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:49-56.

- Shukla S, Singh S, Jain M, et al. Paediatric cutaneous blastomycosis: a rare case diagnosed on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:119-121.

- Smith RJ, Boos MD, Burnham JM, et al. Atypical cutaneous blastomycosis in a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on infliximab. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1386-E1389.

- Wilson JW, Cawley EP, Weidman FD, et al. Primary cutaneous North American blastomycosis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:39-45.

- Zampogna JC, Hoy MJ, Ramos-Caro FA. Primary cutaneous north american blastomycosis in an immunosuppressed child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:128-130.

- Balasaraswathy P, Theerthanath. Cutaneous blastomycosis presenting as non-healing ulcer and responding to oral ketoconazole. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:19.

- Bonifaz A, Morales D, Morales N, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis. an imported case with good response to itraconazole. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2016;33:51-54.

- Clinton TS, Timko AL. Cutaneous blastomycosis without evidence of pulmonary involvement. Mil Med. 2003;168:651-653.

- Dhamija A, D’Souza P, Salgia P, et al. Blastomycosis presenting as solitary nodule: a rare presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:133-135.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Motswaledi HM, Monyemangene FM, Maloba BR, et al. Blastomycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1090-1093.

- Rodríguez-Mena A, Mayorga J, Solís-Ledesma G, et al. Blastomycosis: report of an imported case in Mexico, with only cutaneous lesions [in Spanish]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:210-212.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic disease caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is naturally occurring worldwide but particularly prominent in the Great Lakes, Mississippi, and Ohio River areas of the United States. The disease was first described by Thomas Caspar Gilchrist in 1894 and historically has been referred to as Gilchrist disease, North American blastomycosis, or Chicago disease.1,2 Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin resulting in primary cutaneous disease. Clinically, the lesions are polymorphic and may appear as well-demarcated verrucous plaques containing foci of pustules or ulcerations. Lesions typically heal centrifugally with a cribriform scar.3

We describe an adolescent with a unique history of inoculation 2 weeks prior to the development of a biopsy-confirmed lesion of cutaneous blastomycosis on the left chest wall that clinically resolved following 6 months of itraconazole.

Case Report

A 16-year-old adolescent boy with a history of morbid obesity, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented for evaluation of a painful, slowly enlarging skin lesion on the left chest wall of 2 months’ duration. According to the patient, a “small pimple” appeared at the site of impact 2 weeks following a fall into a muddy flowerbed in Madison, Wisconsin. The patient recalled that although he had soiled his clothing, there was no identifiable puncture of the skin. Despite daily application of hydrogen peroxide and a 1-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the lesion gradually enlarged. Complete review of systems as well as exposure and travel history were otherwise negative.

Physical examination revealed a 5.0×2.5-cm exophytic, firm, well-circumscribed plaque with a papillated crusted surface on the left side of the chest near the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic workup, including complete blood cell count with differential, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus antibody/antigen testing, interferon-gamma release assay, and chest radiograph were all within normal limits.

Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with a brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Displayed in Figure 3 is the Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain that highlighted the thick double-contoured wall-budding yeasts.

The patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous blastomycosis. Treatment was initiated with itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg 2 times daily for 6 months. Following 3 months of therapy, the lesion had markedly improved with violaceous dyschromia and no residual surface changes. After 5 months of itraconazole, the patient stopped taking the medication for 2 months due to pharmacy issues and then resumed. After 6 total months of therapy, the lesion healed with only residual dyschromia and itraconazole was discontinued.

Comment

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic pyogranulomatous disease caused by the dimorphic fungus B dermatitidis, naturally occurring in the soil with a worldwide distribution.4 Individuals affected by the disease often reside in locations where the fungus is endemic, specifically in areas that border the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, the Great Lakes, and Canadian provinces near the Saint Lawrence Seaway. More recently there has been an increased incidence of blastomycosis, with the highest proportion found in Wisconsin and Michigan.1,2 Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.1 Despite the ubiquitous presence of B dermatitidis in regions where the species is endemic, it is likely that many individuals who are exposed to the organism do not develop infection.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis for the development of disease in a particular individual remains unclear. Immunosuppression is not a prerequisite for susceptibility, as evidenced by a review of 123 cases of blastomycosis in which a preceding immunodepressive disorder was present in only 25% of patients. The same study found that it was almost equally common as diabetes mellitus and present in 22% of patients.5 The organism is considered a true pathogen given its ability to affect healthy individuals and the presence of a newly identified novel 120-kD glycoprotein antigen (WI-1) on the cell wall that may confer virulence via extracellular matrix and macrophage binding. Intact cell-mediated immunity that prevents the conversion of conidia (the infectious agent) to yeast (the form that exists at body temperature) plays a key role in conferring natural resistance.6,7

Cutaneous infection may occur by either dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic disease or less commonly via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease. With respect to systemic disease, infection occurs through inhalation of conidia from moist soil containing organic debris, with an incubation period of 4 to 6 weeks. In the lungs, in a process largely dependent on host cell-mediated immunity, the mold quickly converts to yeast and may then either multiply or be phagocytized.2,6,7 Transmission does not occur from person to person.7 Asymptomatic infection may occur in at least 50% of patients, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. Symptomatic pulmonary disease may range from mild flulike symptoms to overt pneumonia, clinically indistinguishable from community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and cancer. Of patients with primary pulmonary disease, 25% to 80% have been reported to develop secondary organ involvement via lymphohematogenous spread most commonly to the skin, followed respectively by the skeletal, genitourinary, and central nervous systems. Currently, there are 54 documented cases of secondary disseminated cutaneous blastomycosis in children reported in the literature.3,8-14

Presentation

Primary cutaneous disease resulting from direct cutaneous inoculation is rare, especially among children.14 Of 28 cases of isolated cutaneous blastomycosis reported in the literature, 12 (42%) were pediatric.3,8-21 Inoculation blastomycosis typically presents as a papule that expands to a well-demarcated verrucous plaque, often up to several centimeters in diameter, and is located on the skin at the site of contact. The lesion may exhibit a myriad of features ranging from pustules or nodules to focal ulcerations, either present centrally or within raised borders that ultimately may communicate via sinus tracking.7 Lesions that are purely pustular in morphology also have been reported. Healing typically begins centrally and expands centrifugally, often with cribriform scarring.2,4,22 Histologic features of primary and secondary blastomycosis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal microabscesses, and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation.4 Classically, broad-based budding yeast are identified with a doubly refractile cell wall that is best visualized on periodic acid–Schiff staining.2

Diagnosis

In approximately 50% of patients with cutaneous blastomycosis resulting from secondary spread, there may be an absence of clinically active pulmonary disease, posing a diagnostic dilemma when differentiating from primary cutaneous disease.1,2,4 Furthermore, the skin findings exhibited in primary and secondary cutaneous blastomycosis cannot be distinguished by clinical inspection.19 To fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of primary cutaneous blastomycosis, there must be an identifiable source of infection from the environment, a lesion at the site of contact, a proven absence of systemic infection, and visualization and/or isolation of fungus from the lesion.4,12 The incubation period of lesions is shorter in primary cutaneous disease (2 weeks) and may aid in its differentiation from secondary disease, which typically is longer with lesions presenting 4 to 6 weeks following initial exposure.4

Treatment

Under the current 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, 6 to 12 months of itraconazole is the treatment recommendation for mild to moderate pulmonary systemic disease without central nervous system involvement.7 Central nervous system disease and moderate to severe pulmonary and systemic disease are treated with intravenous amphotericin B followed by 12 months of oral itraconazole.1,7 Primary cutaneous disease, unlike secondary disease, may self-resolve; however, primary cutaneous disease usually is treated with 6 months of itraconazole, though successful therapy with surgical excision, radiation therapy, and incision and drainage have been reported.19

Unlike secondary cutaneous blastomycosis, primary inoculation disease may be self-limited; however, as treatment with antifungal therapy has become the standard of care, the disease’s propensity to self-resolve has not been well studied.4 Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.1,22 Effective treatment duration may be difficult to definitively assess because of the self-limited nature of the disease. Our patient showed marked improvement after 3 months and resolution of the skin lesion following 6 months of itraconazole therapy. Our findings support the previously documented observation that systemic therapy might potentially be needed only for the time required to eliminate the clinical evidence of cutaneous disease.19 Our patient received the full 6 months of treatment according to current guidelines. Among a review of 22 cases of primary inoculation blastomycosis, the 5 patients who were treated with an azole agent alone showed disease clearance with an average treatment course of 3.2 months, ranging from 1 to 6 months.19 Further studies that assess the time to clearance with antifungal therapy and subsequent recurrence rates may be warranted.

Conclusion

Pediatric primary cutaneous blastomycosis is a rare cutaneous disease. Identifying sources of probable inoculation from the environment for this patient was unique in that the patient fell into a muddy puddle within a flowerbed. Given the patient’s atopic history, a predominance of humoral over cell-mediated immunity may have placed him at risk. He responded well to 6 months of oral itraconazole and there was no ulceration or scar formation. An increased awareness of this infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenhua Liu, MD (Libertyville, Illinois), for reviewing the pathology and Pravin Muniyappa, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for referring the case.

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic disease caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is naturally occurring worldwide but particularly prominent in the Great Lakes, Mississippi, and Ohio River areas of the United States. The disease was first described by Thomas Caspar Gilchrist in 1894 and historically has been referred to as Gilchrist disease, North American blastomycosis, or Chicago disease.1,2 Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin resulting in primary cutaneous disease. Clinically, the lesions are polymorphic and may appear as well-demarcated verrucous plaques containing foci of pustules or ulcerations. Lesions typically heal centrifugally with a cribriform scar.3

We describe an adolescent with a unique history of inoculation 2 weeks prior to the development of a biopsy-confirmed lesion of cutaneous blastomycosis on the left chest wall that clinically resolved following 6 months of itraconazole.

Case Report

A 16-year-old adolescent boy with a history of morbid obesity, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented for evaluation of a painful, slowly enlarging skin lesion on the left chest wall of 2 months’ duration. According to the patient, a “small pimple” appeared at the site of impact 2 weeks following a fall into a muddy flowerbed in Madison, Wisconsin. The patient recalled that although he had soiled his clothing, there was no identifiable puncture of the skin. Despite daily application of hydrogen peroxide and a 1-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the lesion gradually enlarged. Complete review of systems as well as exposure and travel history were otherwise negative.

Physical examination revealed a 5.0×2.5-cm exophytic, firm, well-circumscribed plaque with a papillated crusted surface on the left side of the chest near the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic workup, including complete blood cell count with differential, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus antibody/antigen testing, interferon-gamma release assay, and chest radiograph were all within normal limits.

Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with a brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Displayed in Figure 3 is the Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain that highlighted the thick double-contoured wall-budding yeasts.

The patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous blastomycosis. Treatment was initiated with itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg 2 times daily for 6 months. Following 3 months of therapy, the lesion had markedly improved with violaceous dyschromia and no residual surface changes. After 5 months of itraconazole, the patient stopped taking the medication for 2 months due to pharmacy issues and then resumed. After 6 total months of therapy, the lesion healed with only residual dyschromia and itraconazole was discontinued.

Comment

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic pyogranulomatous disease caused by the dimorphic fungus B dermatitidis, naturally occurring in the soil with a worldwide distribution.4 Individuals affected by the disease often reside in locations where the fungus is endemic, specifically in areas that border the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, the Great Lakes, and Canadian provinces near the Saint Lawrence Seaway. More recently there has been an increased incidence of blastomycosis, with the highest proportion found in Wisconsin and Michigan.1,2 Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.1 Despite the ubiquitous presence of B dermatitidis in regions where the species is endemic, it is likely that many individuals who are exposed to the organism do not develop infection.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis for the development of disease in a particular individual remains unclear. Immunosuppression is not a prerequisite for susceptibility, as evidenced by a review of 123 cases of blastomycosis in which a preceding immunodepressive disorder was present in only 25% of patients. The same study found that it was almost equally common as diabetes mellitus and present in 22% of patients.5 The organism is considered a true pathogen given its ability to affect healthy individuals and the presence of a newly identified novel 120-kD glycoprotein antigen (WI-1) on the cell wall that may confer virulence via extracellular matrix and macrophage binding. Intact cell-mediated immunity that prevents the conversion of conidia (the infectious agent) to yeast (the form that exists at body temperature) plays a key role in conferring natural resistance.6,7

Cutaneous infection may occur by either dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic disease or less commonly via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease. With respect to systemic disease, infection occurs through inhalation of conidia from moist soil containing organic debris, with an incubation period of 4 to 6 weeks. In the lungs, in a process largely dependent on host cell-mediated immunity, the mold quickly converts to yeast and may then either multiply or be phagocytized.2,6,7 Transmission does not occur from person to person.7 Asymptomatic infection may occur in at least 50% of patients, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. Symptomatic pulmonary disease may range from mild flulike symptoms to overt pneumonia, clinically indistinguishable from community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and cancer. Of patients with primary pulmonary disease, 25% to 80% have been reported to develop secondary organ involvement via lymphohematogenous spread most commonly to the skin, followed respectively by the skeletal, genitourinary, and central nervous systems. Currently, there are 54 documented cases of secondary disseminated cutaneous blastomycosis in children reported in the literature.3,8-14

Presentation

Primary cutaneous disease resulting from direct cutaneous inoculation is rare, especially among children.14 Of 28 cases of isolated cutaneous blastomycosis reported in the literature, 12 (42%) were pediatric.3,8-21 Inoculation blastomycosis typically presents as a papule that expands to a well-demarcated verrucous plaque, often up to several centimeters in diameter, and is located on the skin at the site of contact. The lesion may exhibit a myriad of features ranging from pustules or nodules to focal ulcerations, either present centrally or within raised borders that ultimately may communicate via sinus tracking.7 Lesions that are purely pustular in morphology also have been reported. Healing typically begins centrally and expands centrifugally, often with cribriform scarring.2,4,22 Histologic features of primary and secondary blastomycosis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal microabscesses, and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation.4 Classically, broad-based budding yeast are identified with a doubly refractile cell wall that is best visualized on periodic acid–Schiff staining.2

Diagnosis

In approximately 50% of patients with cutaneous blastomycosis resulting from secondary spread, there may be an absence of clinically active pulmonary disease, posing a diagnostic dilemma when differentiating from primary cutaneous disease.1,2,4 Furthermore, the skin findings exhibited in primary and secondary cutaneous blastomycosis cannot be distinguished by clinical inspection.19 To fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of primary cutaneous blastomycosis, there must be an identifiable source of infection from the environment, a lesion at the site of contact, a proven absence of systemic infection, and visualization and/or isolation of fungus from the lesion.4,12 The incubation period of lesions is shorter in primary cutaneous disease (2 weeks) and may aid in its differentiation from secondary disease, which typically is longer with lesions presenting 4 to 6 weeks following initial exposure.4

Treatment

Under the current 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, 6 to 12 months of itraconazole is the treatment recommendation for mild to moderate pulmonary systemic disease without central nervous system involvement.7 Central nervous system disease and moderate to severe pulmonary and systemic disease are treated with intravenous amphotericin B followed by 12 months of oral itraconazole.1,7 Primary cutaneous disease, unlike secondary disease, may self-resolve; however, primary cutaneous disease usually is treated with 6 months of itraconazole, though successful therapy with surgical excision, radiation therapy, and incision and drainage have been reported.19

Unlike secondary cutaneous blastomycosis, primary inoculation disease may be self-limited; however, as treatment with antifungal therapy has become the standard of care, the disease’s propensity to self-resolve has not been well studied.4 Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.1,22 Effective treatment duration may be difficult to definitively assess because of the self-limited nature of the disease. Our patient showed marked improvement after 3 months and resolution of the skin lesion following 6 months of itraconazole therapy. Our findings support the previously documented observation that systemic therapy might potentially be needed only for the time required to eliminate the clinical evidence of cutaneous disease.19 Our patient received the full 6 months of treatment according to current guidelines. Among a review of 22 cases of primary inoculation blastomycosis, the 5 patients who were treated with an azole agent alone showed disease clearance with an average treatment course of 3.2 months, ranging from 1 to 6 months.19 Further studies that assess the time to clearance with antifungal therapy and subsequent recurrence rates may be warranted.

Conclusion

Pediatric primary cutaneous blastomycosis is a rare cutaneous disease. Identifying sources of probable inoculation from the environment for this patient was unique in that the patient fell into a muddy puddle within a flowerbed. Given the patient’s atopic history, a predominance of humoral over cell-mediated immunity may have placed him at risk. He responded well to 6 months of oral itraconazole and there was no ulceration or scar formation. An increased awareness of this infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenhua Liu, MD (Libertyville, Illinois), for reviewing the pathology and Pravin Muniyappa, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for referring the case.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Smith JA, Riddell Jt, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:440-449.

- Fisher KR, Baselski V, Beard G, et al. Pustular blastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:355-358.

- Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

- Lemos LB, Baliga M, Guo M. Blastomycosis: the great pretender can also be an opportunist. initial clinical diagnosis and underlying diseases in 123 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:194-203.

- Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21-40, vii.

- Blastomycosis. In: Kimberlin DW, ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:263-264.

- Brick KE, Drolet BA, Lyon VB, et al. Cutaneous and disseminated blastomycosis: a pediatric case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:23-28.

- Fanella S, Skinner S, Trepman E, et al. Blastomycosis in children and adolescents: a 30-year experience from Manitoba. Med Mycol. 2011;49:627-632.

- Frost HM, Anderson J, Ivacic L, et al. Blastomycosis in children: an analysis of clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:49-56.

- Shukla S, Singh S, Jain M, et al. Paediatric cutaneous blastomycosis: a rare case diagnosed on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:119-121.

- Smith RJ, Boos MD, Burnham JM, et al. Atypical cutaneous blastomycosis in a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on infliximab. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1386-E1389.

- Wilson JW, Cawley EP, Weidman FD, et al. Primary cutaneous North American blastomycosis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:39-45.

- Zampogna JC, Hoy MJ, Ramos-Caro FA. Primary cutaneous north american blastomycosis in an immunosuppressed child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:128-130.

- Balasaraswathy P, Theerthanath. Cutaneous blastomycosis presenting as non-healing ulcer and responding to oral ketoconazole. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:19.

- Bonifaz A, Morales D, Morales N, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis. an imported case with good response to itraconazole. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2016;33:51-54.

- Clinton TS, Timko AL. Cutaneous blastomycosis without evidence of pulmonary involvement. Mil Med. 2003;168:651-653.

- Dhamija A, D’Souza P, Salgia P, et al. Blastomycosis presenting as solitary nodule: a rare presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:133-135.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Motswaledi HM, Monyemangene FM, Maloba BR, et al. Blastomycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1090-1093.

- Rodríguez-Mena A, Mayorga J, Solís-Ledesma G, et al. Blastomycosis: report of an imported case in Mexico, with only cutaneous lesions [in Spanish]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:210-212.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Smith JA, Riddell Jt, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:440-449.

- Fisher KR, Baselski V, Beard G, et al. Pustular blastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:355-358.

- Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

- Lemos LB, Baliga M, Guo M. Blastomycosis: the great pretender can also be an opportunist. initial clinical diagnosis and underlying diseases in 123 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:194-203.

- Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21-40, vii.

- Blastomycosis. In: Kimberlin DW, ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:263-264.

- Brick KE, Drolet BA, Lyon VB, et al. Cutaneous and disseminated blastomycosis: a pediatric case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:23-28.

- Fanella S, Skinner S, Trepman E, et al. Blastomycosis in children and adolescents: a 30-year experience from Manitoba. Med Mycol. 2011;49:627-632.

- Frost HM, Anderson J, Ivacic L, et al. Blastomycosis in children: an analysis of clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:49-56.

- Shukla S, Singh S, Jain M, et al. Paediatric cutaneous blastomycosis: a rare case diagnosed on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:119-121.

- Smith RJ, Boos MD, Burnham JM, et al. Atypical cutaneous blastomycosis in a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on infliximab. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1386-E1389.

- Wilson JW, Cawley EP, Weidman FD, et al. Primary cutaneous North American blastomycosis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:39-45.

- Zampogna JC, Hoy MJ, Ramos-Caro FA. Primary cutaneous north american blastomycosis in an immunosuppressed child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:128-130.

- Balasaraswathy P, Theerthanath. Cutaneous blastomycosis presenting as non-healing ulcer and responding to oral ketoconazole. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:19.

- Bonifaz A, Morales D, Morales N, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis. an imported case with good response to itraconazole. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2016;33:51-54.

- Clinton TS, Timko AL. Cutaneous blastomycosis without evidence of pulmonary involvement. Mil Med. 2003;168:651-653.

- Dhamija A, D’Souza P, Salgia P, et al. Blastomycosis presenting as solitary nodule: a rare presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:133-135.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Motswaledi HM, Monyemangene FM, Maloba BR, et al. Blastomycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1090-1093.

- Rodríguez-Mena A, Mayorga J, Solís-Ledesma G, et al. Blastomycosis: report of an imported case in Mexico, with only cutaneous lesions [in Spanish]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:210-212.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease.

- Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.

- Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.

- Increased awareness of this rare infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Itchy Papules and Plaques on the Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.