User login

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Lifeguards play a crucial role in ensuring water safety, but they also are uniquely positioned to promote skin cancer prevention and proper sunscreen use.1,2 There are several benefits and challenges to offering skin cancer prevention training for lifeguards.3 We examine the advantages of training, highlight the role lifeguards can play in larger public skin cancer prevention efforts, and address practical techniques for developing lifeguardfocused skin cancer education programs. By providing this knowledge to lifeguards, we can improve community health outcomes and encourage sun-safe behaviors in high-risk outdoor locations.

Benefits of Skin Cancer Prevention Training for Lifeguards

Research has shown that lifeguards are at an elevated risk for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma due to frequent prolonged occupational sun exposure.1,2,4-6 Therefore, comprehensive education on skin cancer prevention—including instruction on proper sunscreen application techniques and the importance of regular reapplication as well as how to recognize suspicious skin lesions—should be incorporated into lifeguard certification programs. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a skin cancer prevention program for lifeguards found that many of the participants lacked a thorough understanding of the different types of skin cancer.5 Another study found that lifeguards at pools in areas where societal norms supporting sun safety are stronger exhibited noticeably more sun protection practices, with regression estimates of 0.22 (95% CI, 0.17-0.26).7 Empowering lifeguards with valuable health knowledge during their regular training could potentially reduce their risk for skin cancer,4 as they may be more inclined to use sunscreen appropriately and reach out to a dermatologist for regular skin checks and evaluation of suspicious lesions.

Role of Lifeguards in Public Skin Cancer Prevention Efforts

Once trained on skin cancer prevention, lifeguards also can play a pivotal role in promoting sunscreen use among the public. Despite the widespread availability of high-quality sunscreens, many swimmers and beachgoers neglect to regularly apply or reapply sunscreen, especially on commonly exposed areas such as the back, shoulders, and face.8 Educating lifeguards on skin cancer prevention could enhance health outcomes by increasing early detection rates and promoting sun-safe behaviors among the general public.9 However, additional training requirements might increase the cost and time commitment for lifeguard certification, potentially leading to staffing shortages.3,7 There also is a risk of lifeguards overstepping their role and providing inaccurate medical advice, which could cause distress or even lead to liability issues.7 Balancing these factors will be crucial in developing effective and sustainable skin cancer prevention programs for lifeguards.

Implementing Lifeguard Skin Cancer Training

Implementing skin cancer prevention training programs for lifeguards requires strategic collaboration between dermatologists, and lifeguard training organizations to ensure that the participants receive consistent and comprehensive training.10 Additionally, public health campaigns can support these efforts by raising awareness about the importance of sun safety and regular skin checks.6 Tailored training modules/materials, ongoing technical assistance, and active, multicomponent approaches that account for both individual and environmental factors can increase program implementation in a variety of community settings.

Final Thoughts

Through effective education, lifeguards can potentially have a substantial impact on skin cancer prevention, both among lifeguards themselves and the general public. By promoting proper sunscreen use, lifeguards can help reduce the incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers. Future studies should focus on developing and implementing targeted education initiatives for lifeguards, fostering collaboration between relevant stakeholders, and raising public awareness about the importance of sun safety and early skin cancer detection. These efforts ultimately could lead to improved public health outcomes and reduced skin cancer rates, particularly in high-risk populations that frequently are exposed to UV radiation.

- Enos CW, Rey S, Slocum J, et al. Sun-protection behaviors among active members of the United States Lifesaving Association. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-20.

- Verma K, Lewis DJ, Siddiqui FS, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery management of melanoma and melanoma in situ. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606123/

- Verma KK, Joshi TP, Lewis DJ, et al. Nail technicians as partners in early melanoma detection: bridging the knowledge gap. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:586. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03342-0

- Geller AC, Glanz K, Shigaki D, et al. Impact of skin cancer prevention on outdoor aquatics staff: the Pool Cool program in Hawaii and Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2001;33:155-161. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0870

- Hiemstra M, Glanz K, Nehl E. Changes in sunburn and tanning attitudes among lifeguards over a summer season. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:430-437. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.050

- Verma KK, Ahmad N, Friedmann DP, et al. Melanoma in tattooed skin: diagnostic challenges and the potential for tattoo artists in early detection. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:690. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03415-0

- Hall DM, McCarty F, Elliott T, et al. Lifeguards’ sun protection habits and sunburns: association with sun-safe environments and skin cancer prevention program participation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:139-144. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.553

- Emmons KM, Geller AC, Puleo E, et al. Skin cancer education and early detection at the beach: a randomized trial of dermatologist examination and biometric feedback. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:282-289. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.040

- Rabin BA, Nehl E, Elliott T, et al. Individual and setting level predictors of the implementation of a skin cancer prevention program: a multilevel analysis. Implement Sci. 2010;5:40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-40

- Walkosz BJ, Buller D, Buller M, et al. Sun safe workplaces: effect of an occupational skin cancer prevention program on employee sun safety practices. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:900-997. doi:10.1097 /JOM.0000000000001427

Lifeguards play a crucial role in ensuring water safety, but they also are uniquely positioned to promote skin cancer prevention and proper sunscreen use.1,2 There are several benefits and challenges to offering skin cancer prevention training for lifeguards.3 We examine the advantages of training, highlight the role lifeguards can play in larger public skin cancer prevention efforts, and address practical techniques for developing lifeguardfocused skin cancer education programs. By providing this knowledge to lifeguards, we can improve community health outcomes and encourage sun-safe behaviors in high-risk outdoor locations.

Benefits of Skin Cancer Prevention Training for Lifeguards

Research has shown that lifeguards are at an elevated risk for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma due to frequent prolonged occupational sun exposure.1,2,4-6 Therefore, comprehensive education on skin cancer prevention—including instruction on proper sunscreen application techniques and the importance of regular reapplication as well as how to recognize suspicious skin lesions—should be incorporated into lifeguard certification programs. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a skin cancer prevention program for lifeguards found that many of the participants lacked a thorough understanding of the different types of skin cancer.5 Another study found that lifeguards at pools in areas where societal norms supporting sun safety are stronger exhibited noticeably more sun protection practices, with regression estimates of 0.22 (95% CI, 0.17-0.26).7 Empowering lifeguards with valuable health knowledge during their regular training could potentially reduce their risk for skin cancer,4 as they may be more inclined to use sunscreen appropriately and reach out to a dermatologist for regular skin checks and evaluation of suspicious lesions.

Role of Lifeguards in Public Skin Cancer Prevention Efforts

Once trained on skin cancer prevention, lifeguards also can play a pivotal role in promoting sunscreen use among the public. Despite the widespread availability of high-quality sunscreens, many swimmers and beachgoers neglect to regularly apply or reapply sunscreen, especially on commonly exposed areas such as the back, shoulders, and face.8 Educating lifeguards on skin cancer prevention could enhance health outcomes by increasing early detection rates and promoting sun-safe behaviors among the general public.9 However, additional training requirements might increase the cost and time commitment for lifeguard certification, potentially leading to staffing shortages.3,7 There also is a risk of lifeguards overstepping their role and providing inaccurate medical advice, which could cause distress or even lead to liability issues.7 Balancing these factors will be crucial in developing effective and sustainable skin cancer prevention programs for lifeguards.

Implementing Lifeguard Skin Cancer Training

Implementing skin cancer prevention training programs for lifeguards requires strategic collaboration between dermatologists, and lifeguard training organizations to ensure that the participants receive consistent and comprehensive training.10 Additionally, public health campaigns can support these efforts by raising awareness about the importance of sun safety and regular skin checks.6 Tailored training modules/materials, ongoing technical assistance, and active, multicomponent approaches that account for both individual and environmental factors can increase program implementation in a variety of community settings.

Final Thoughts

Through effective education, lifeguards can potentially have a substantial impact on skin cancer prevention, both among lifeguards themselves and the general public. By promoting proper sunscreen use, lifeguards can help reduce the incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers. Future studies should focus on developing and implementing targeted education initiatives for lifeguards, fostering collaboration between relevant stakeholders, and raising public awareness about the importance of sun safety and early skin cancer detection. These efforts ultimately could lead to improved public health outcomes and reduced skin cancer rates, particularly in high-risk populations that frequently are exposed to UV radiation.

Lifeguards play a crucial role in ensuring water safety, but they also are uniquely positioned to promote skin cancer prevention and proper sunscreen use.1,2 There are several benefits and challenges to offering skin cancer prevention training for lifeguards.3 We examine the advantages of training, highlight the role lifeguards can play in larger public skin cancer prevention efforts, and address practical techniques for developing lifeguardfocused skin cancer education programs. By providing this knowledge to lifeguards, we can improve community health outcomes and encourage sun-safe behaviors in high-risk outdoor locations.

Benefits of Skin Cancer Prevention Training for Lifeguards

Research has shown that lifeguards are at an elevated risk for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma due to frequent prolonged occupational sun exposure.1,2,4-6 Therefore, comprehensive education on skin cancer prevention—including instruction on proper sunscreen application techniques and the importance of regular reapplication as well as how to recognize suspicious skin lesions—should be incorporated into lifeguard certification programs. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a skin cancer prevention program for lifeguards found that many of the participants lacked a thorough understanding of the different types of skin cancer.5 Another study found that lifeguards at pools in areas where societal norms supporting sun safety are stronger exhibited noticeably more sun protection practices, with regression estimates of 0.22 (95% CI, 0.17-0.26).7 Empowering lifeguards with valuable health knowledge during their regular training could potentially reduce their risk for skin cancer,4 as they may be more inclined to use sunscreen appropriately and reach out to a dermatologist for regular skin checks and evaluation of suspicious lesions.

Role of Lifeguards in Public Skin Cancer Prevention Efforts

Once trained on skin cancer prevention, lifeguards also can play a pivotal role in promoting sunscreen use among the public. Despite the widespread availability of high-quality sunscreens, many swimmers and beachgoers neglect to regularly apply or reapply sunscreen, especially on commonly exposed areas such as the back, shoulders, and face.8 Educating lifeguards on skin cancer prevention could enhance health outcomes by increasing early detection rates and promoting sun-safe behaviors among the general public.9 However, additional training requirements might increase the cost and time commitment for lifeguard certification, potentially leading to staffing shortages.3,7 There also is a risk of lifeguards overstepping their role and providing inaccurate medical advice, which could cause distress or even lead to liability issues.7 Balancing these factors will be crucial in developing effective and sustainable skin cancer prevention programs for lifeguards.

Implementing Lifeguard Skin Cancer Training

Implementing skin cancer prevention training programs for lifeguards requires strategic collaboration between dermatologists, and lifeguard training organizations to ensure that the participants receive consistent and comprehensive training.10 Additionally, public health campaigns can support these efforts by raising awareness about the importance of sun safety and regular skin checks.6 Tailored training modules/materials, ongoing technical assistance, and active, multicomponent approaches that account for both individual and environmental factors can increase program implementation in a variety of community settings.

Final Thoughts

Through effective education, lifeguards can potentially have a substantial impact on skin cancer prevention, both among lifeguards themselves and the general public. By promoting proper sunscreen use, lifeguards can help reduce the incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers. Future studies should focus on developing and implementing targeted education initiatives for lifeguards, fostering collaboration between relevant stakeholders, and raising public awareness about the importance of sun safety and early skin cancer detection. These efforts ultimately could lead to improved public health outcomes and reduced skin cancer rates, particularly in high-risk populations that frequently are exposed to UV radiation.

- Enos CW, Rey S, Slocum J, et al. Sun-protection behaviors among active members of the United States Lifesaving Association. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-20.

- Verma K, Lewis DJ, Siddiqui FS, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery management of melanoma and melanoma in situ. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606123/

- Verma KK, Joshi TP, Lewis DJ, et al. Nail technicians as partners in early melanoma detection: bridging the knowledge gap. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:586. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03342-0

- Geller AC, Glanz K, Shigaki D, et al. Impact of skin cancer prevention on outdoor aquatics staff: the Pool Cool program in Hawaii and Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2001;33:155-161. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0870

- Hiemstra M, Glanz K, Nehl E. Changes in sunburn and tanning attitudes among lifeguards over a summer season. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:430-437. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.050

- Verma KK, Ahmad N, Friedmann DP, et al. Melanoma in tattooed skin: diagnostic challenges and the potential for tattoo artists in early detection. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:690. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03415-0

- Hall DM, McCarty F, Elliott T, et al. Lifeguards’ sun protection habits and sunburns: association with sun-safe environments and skin cancer prevention program participation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:139-144. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.553

- Emmons KM, Geller AC, Puleo E, et al. Skin cancer education and early detection at the beach: a randomized trial of dermatologist examination and biometric feedback. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:282-289. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.040

- Rabin BA, Nehl E, Elliott T, et al. Individual and setting level predictors of the implementation of a skin cancer prevention program: a multilevel analysis. Implement Sci. 2010;5:40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-40

- Walkosz BJ, Buller D, Buller M, et al. Sun safe workplaces: effect of an occupational skin cancer prevention program on employee sun safety practices. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:900-997. doi:10.1097 /JOM.0000000000001427

- Enos CW, Rey S, Slocum J, et al. Sun-protection behaviors among active members of the United States Lifesaving Association. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-20.

- Verma K, Lewis DJ, Siddiqui FS, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery management of melanoma and melanoma in situ. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606123/

- Verma KK, Joshi TP, Lewis DJ, et al. Nail technicians as partners in early melanoma detection: bridging the knowledge gap. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:586. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03342-0

- Geller AC, Glanz K, Shigaki D, et al. Impact of skin cancer prevention on outdoor aquatics staff: the Pool Cool program in Hawaii and Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2001;33:155-161. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0870

- Hiemstra M, Glanz K, Nehl E. Changes in sunburn and tanning attitudes among lifeguards over a summer season. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:430-437. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.050

- Verma KK, Ahmad N, Friedmann DP, et al. Melanoma in tattooed skin: diagnostic challenges and the potential for tattoo artists in early detection. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:690. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03415-0

- Hall DM, McCarty F, Elliott T, et al. Lifeguards’ sun protection habits and sunburns: association with sun-safe environments and skin cancer prevention program participation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:139-144. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.553

- Emmons KM, Geller AC, Puleo E, et al. Skin cancer education and early detection at the beach: a randomized trial of dermatologist examination and biometric feedback. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:282-289. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.040

- Rabin BA, Nehl E, Elliott T, et al. Individual and setting level predictors of the implementation of a skin cancer prevention program: a multilevel analysis. Implement Sci. 2010;5:40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-40

- Walkosz BJ, Buller D, Buller M, et al. Sun safe workplaces: effect of an occupational skin cancer prevention program on employee sun safety practices. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:900-997. doi:10.1097 /JOM.0000000000001427

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis Resolution With Topical Dapsone

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a disease characterized by inflammation of small vessels with characteristic clinical findings of petechiae and palpable purpura.1 Numerous etiologies have been described, but the disease commonly remains idiopathic.2,3 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis often spontaneously resolves within weeks and requires only symptomatic treatment. Chronic or severe disease can require systemic medical treatment with agents such as colchicine, dapsone, and corticosteroids. These agents are effective but carry risks of serious side effects.4,5 These side effects and/or medical contraindications prevent some patients from taking systemic medications for LCV. We present a case of LCV that resolved after treatment with topical dapsone, highlighting a potential new treatment ofLCV with a markedly better side-effect profile.

Case Report

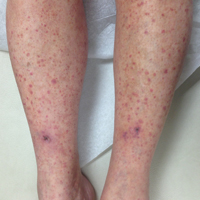

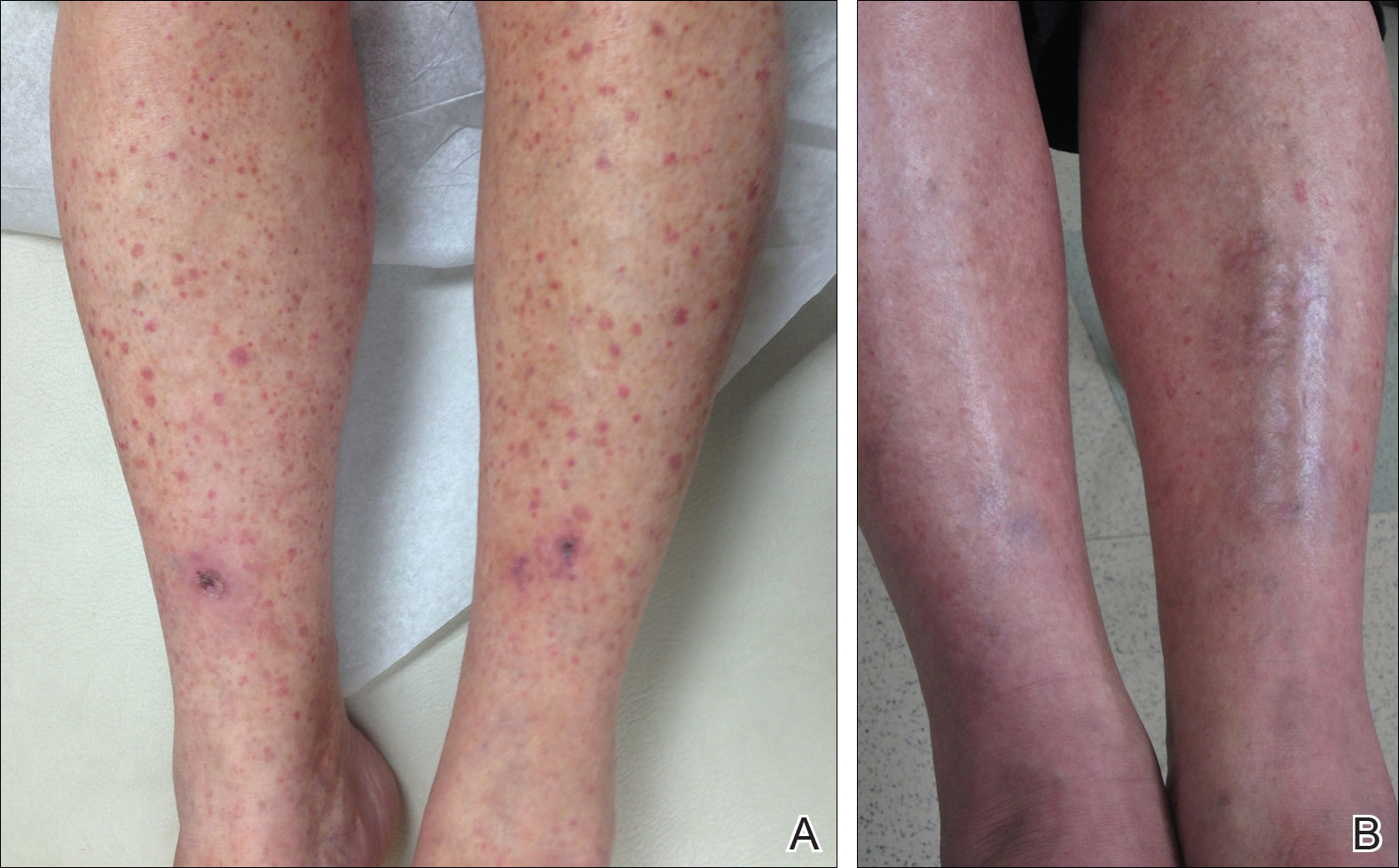

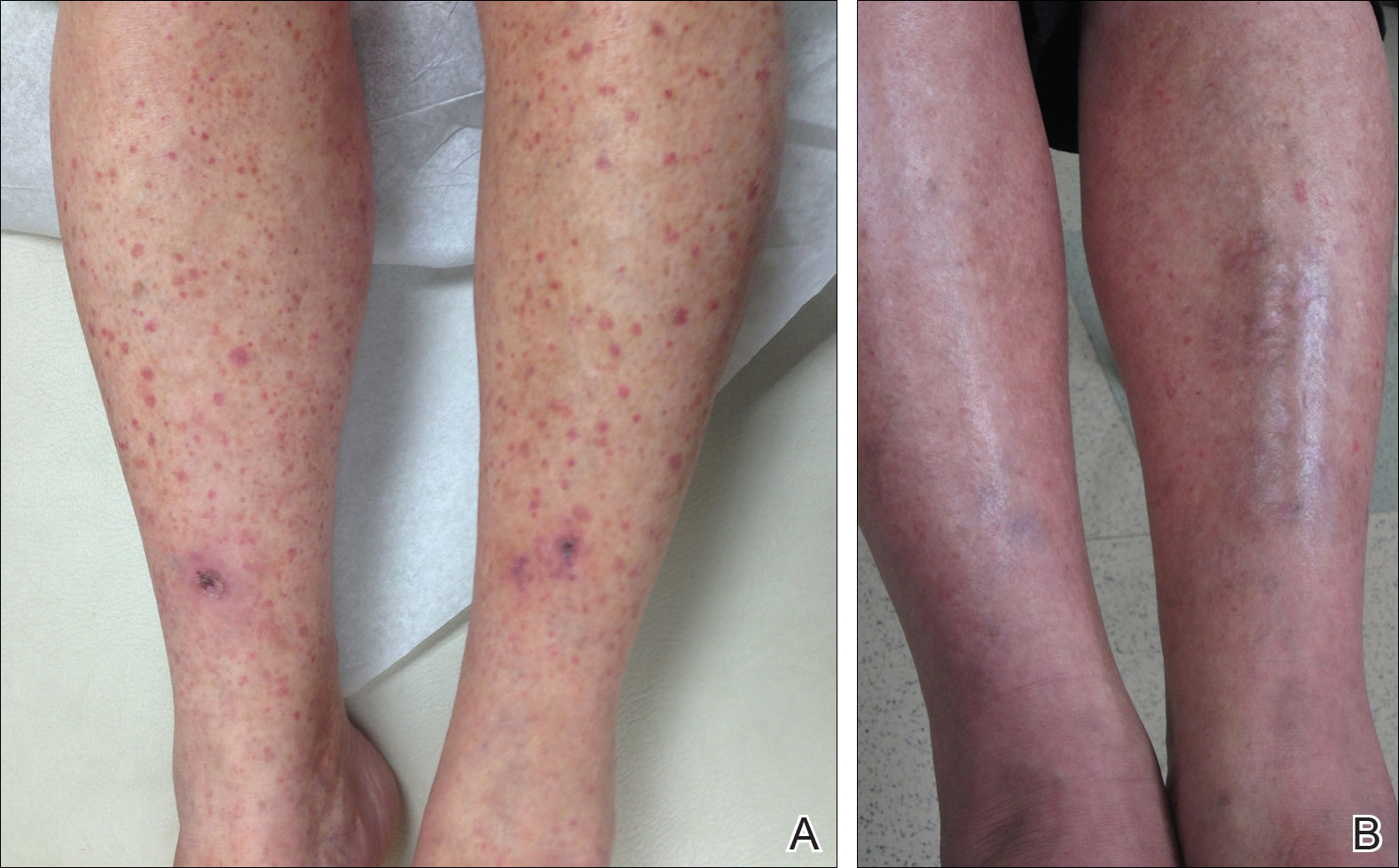

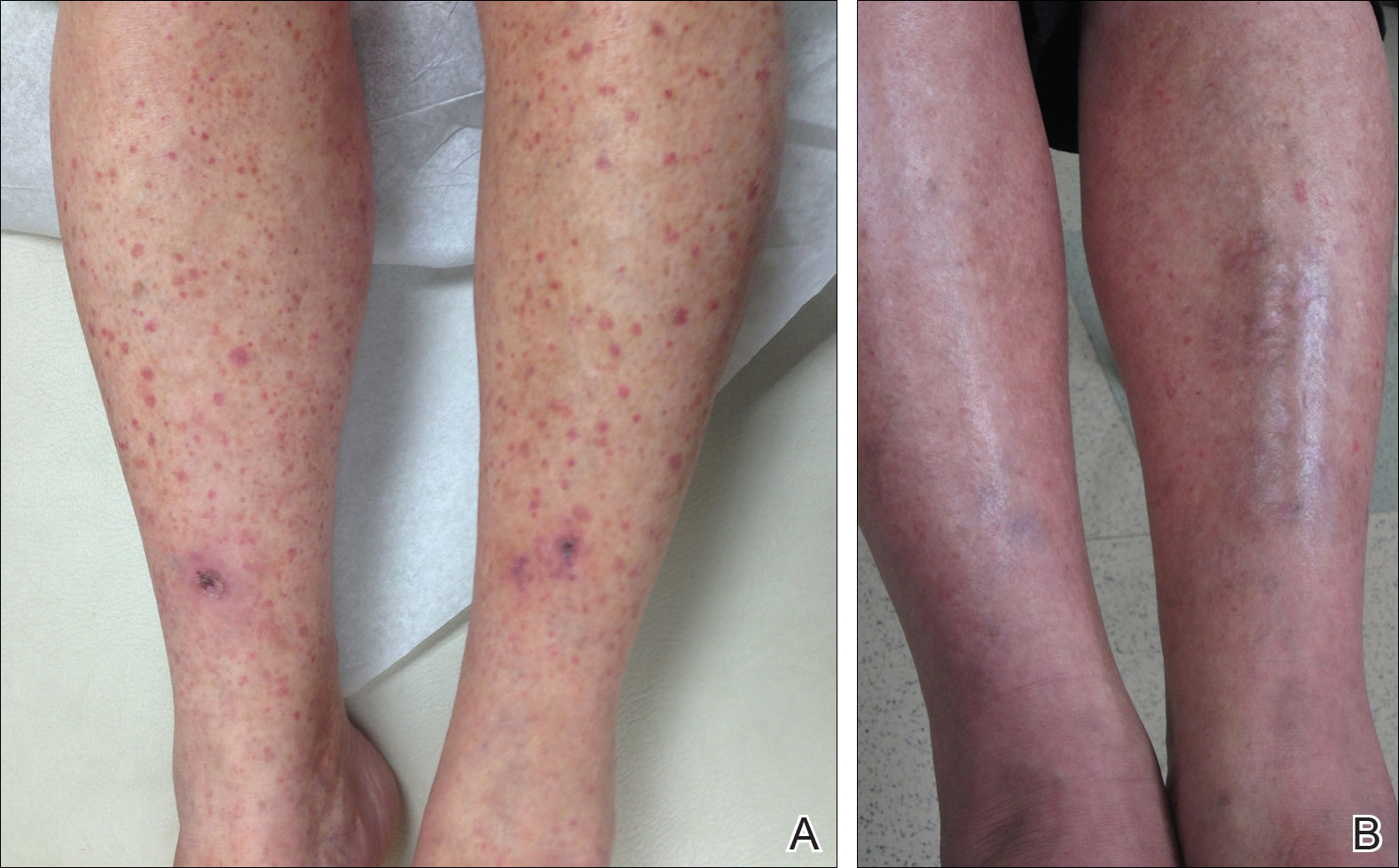

A 60-year-old woman with recent upper respiratory tract and sinus infections presented to our dermatology clinic with painful palpable purpura on the bilateral shins, thighs, and dorsal aspects of the feet of several months’ duration (Figure, A). Her primary care provider initiated treatment with amoxicillin and doxycycline for the infections. When the rash developed approximately 1.5 weeks following initiation of her symptoms, the patient was referred to the dermatology and rheumatology departments at our institution. The treating dermatologist (M.B.T.) obtained a 4-mm punch biopsy from the right lower leg and LCV was shown on histology. The patient completed a 14-day course of doxycycline and amoxicillin without resolution of the eruption. After an extensive investigation, the treating rheumatologist concluded that the LCV was idiopathic or secondary to an infection or drug exposure. The rheumatologist started the patient on oral prednisone for the chronic symptomatic LCV, but she was intolerant of this medication and discontinued it after 1 week. Our dermatology clinic started her on triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, but she continued to experience new and worsening lesions. At her follow-up appointment 1 month later, triamcinolone cream was discontinued and dapsone gel 5% twice daily was started. She experienced resolution of her previously recalcitrant LCV within 3 weeks (Figure, B).

Comment

Established therapies for LCV carry serious side-effect profiles, which can preclude their use.5 Therefore, a topical therapeutic alternative for LCV would be ideal. Systemic prednisone is the first-line therapy for chronic and/or symptomatic LCV, but its side effects include suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, immunosuppression, osteonecrosis, and glucose intolerance.5 Colchicine therapy carries risks for blood dyscrasia, immunosuppression, and gastrointestinal tract upset. Systemic dapsone also is an effective therapy for chronic and/or symptomatic LCV.5,6 However, systemic dapsone requires glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency screening and routine monitoring of blood counts, and it also carries the risk for serious adverse effects including neuropathy, blood dyscrasia, and hypersensitivity syndrome.5,6 Topical dapsone may provide similar efficacy with far fewer adverse effects and has proven to be a safe treatment of acne, even when used in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. It displays low systemic absorption and does not accumulate over time once a steady state is reached.7 It also has been shown to be beneficial in other vasculopathies such as erythema elevatum diutinum and in other neutrophilic inflammatory disorders such as pyoderma gangrenosum.8,9 A case of methemoglobinemia due to topical dapsone has been reported.10 Although this effect is rare, clinicians should be aware of such adverse effects when using medications for off-label purposes.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis can spontaneously resolve; however, our patient’s disease was chronic for several months, and she continued to develop new lesions without signs of resolution. After initiating topical dapsone, she experienced resolution within 3 weeks.

Conclusion

Topical dapsone is a novel approach for treating LCV. Given this drug’s favorable side-effect profile compared to the currently available therapeutic alternatives, we believe it is a reasonable option in select patients. Further investigation is needed to prove its efficacy, but it could be an ideal alternative for patients with contraindications to traditional therapies and/or for those unable to tolerate systemic therapy.

- Koutkia P, Mylonakis E, Rounds S, et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis: an update for the clinician. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:315-322.

- Af Ekenstam E, Callen JP. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. clinical and laboratory features of 82 patients seen in private practice. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:484-489.

- Gyselbrecht L, de Keyser F, Ongenae K, et al. Etiological factors and underlying conditions in patientswith leucocytoclastic vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14:665-668.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucglà A, et al. Colchicine in the treatment of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. results of a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1399-1402.

- Sunderkotter C, Bonsmann G, Sindrilaru A, et al. Management of leukocytoclastic vasculitis: clinical review. J Dermatol Treat. 2005;16:193-206.

- Zhu YI, Stiller MJ. Dapsone and sulfones in dermatology: overview and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:420-434.

- Stotland M, Shalita AR, Kissling RF. Dapsone 5% gel: a review of its efficacy and safety in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:221-227.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, et al. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:481-484.

- Handler MZ, Hamilton H, Aires D. Treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed dapsone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1059-1061.

- Swartzentruber GS, Yanta JH, Pizon AF. Methemoglobi-nemia as a complication of topical dapsone. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:491-492.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a disease characterized by inflammation of small vessels with characteristic clinical findings of petechiae and palpable purpura.1 Numerous etiologies have been described, but the disease commonly remains idiopathic.2,3 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis often spontaneously resolves within weeks and requires only symptomatic treatment. Chronic or severe disease can require systemic medical treatment with agents such as colchicine, dapsone, and corticosteroids. These agents are effective but carry risks of serious side effects.4,5 These side effects and/or medical contraindications prevent some patients from taking systemic medications for LCV. We present a case of LCV that resolved after treatment with topical dapsone, highlighting a potential new treatment ofLCV with a markedly better side-effect profile.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman with recent upper respiratory tract and sinus infections presented to our dermatology clinic with painful palpable purpura on the bilateral shins, thighs, and dorsal aspects of the feet of several months’ duration (Figure, A). Her primary care provider initiated treatment with amoxicillin and doxycycline for the infections. When the rash developed approximately 1.5 weeks following initiation of her symptoms, the patient was referred to the dermatology and rheumatology departments at our institution. The treating dermatologist (M.B.T.) obtained a 4-mm punch biopsy from the right lower leg and LCV was shown on histology. The patient completed a 14-day course of doxycycline and amoxicillin without resolution of the eruption. After an extensive investigation, the treating rheumatologist concluded that the LCV was idiopathic or secondary to an infection or drug exposure. The rheumatologist started the patient on oral prednisone for the chronic symptomatic LCV, but she was intolerant of this medication and discontinued it after 1 week. Our dermatology clinic started her on triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, but she continued to experience new and worsening lesions. At her follow-up appointment 1 month later, triamcinolone cream was discontinued and dapsone gel 5% twice daily was started. She experienced resolution of her previously recalcitrant LCV within 3 weeks (Figure, B).

Comment

Established therapies for LCV carry serious side-effect profiles, which can preclude their use.5 Therefore, a topical therapeutic alternative for LCV would be ideal. Systemic prednisone is the first-line therapy for chronic and/or symptomatic LCV, but its side effects include suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, immunosuppression, osteonecrosis, and glucose intolerance.5 Colchicine therapy carries risks for blood dyscrasia, immunosuppression, and gastrointestinal tract upset. Systemic dapsone also is an effective therapy for chronic and/or symptomatic LCV.5,6 However, systemic dapsone requires glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency screening and routine monitoring of blood counts, and it also carries the risk for serious adverse effects including neuropathy, blood dyscrasia, and hypersensitivity syndrome.5,6 Topical dapsone may provide similar efficacy with far fewer adverse effects and has proven to be a safe treatment of acne, even when used in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. It displays low systemic absorption and does not accumulate over time once a steady state is reached.7 It also has been shown to be beneficial in other vasculopathies such as erythema elevatum diutinum and in other neutrophilic inflammatory disorders such as pyoderma gangrenosum.8,9 A case of methemoglobinemia due to topical dapsone has been reported.10 Although this effect is rare, clinicians should be aware of such adverse effects when using medications for off-label purposes.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis can spontaneously resolve; however, our patient’s disease was chronic for several months, and she continued to develop new lesions without signs of resolution. After initiating topical dapsone, she experienced resolution within 3 weeks.

Conclusion

Topical dapsone is a novel approach for treating LCV. Given this drug’s favorable side-effect profile compared to the currently available therapeutic alternatives, we believe it is a reasonable option in select patients. Further investigation is needed to prove its efficacy, but it could be an ideal alternative for patients with contraindications to traditional therapies and/or for those unable to tolerate systemic therapy.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a disease characterized by inflammation of small vessels with characteristic clinical findings of petechiae and palpable purpura.1 Numerous etiologies have been described, but the disease commonly remains idiopathic.2,3 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis often spontaneously resolves within weeks and requires only symptomatic treatment. Chronic or severe disease can require systemic medical treatment with agents such as colchicine, dapsone, and corticosteroids. These agents are effective but carry risks of serious side effects.4,5 These side effects and/or medical contraindications prevent some patients from taking systemic medications for LCV. We present a case of LCV that resolved after treatment with topical dapsone, highlighting a potential new treatment ofLCV with a markedly better side-effect profile.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman with recent upper respiratory tract and sinus infections presented to our dermatology clinic with painful palpable purpura on the bilateral shins, thighs, and dorsal aspects of the feet of several months’ duration (Figure, A). Her primary care provider initiated treatment with amoxicillin and doxycycline for the infections. When the rash developed approximately 1.5 weeks following initiation of her symptoms, the patient was referred to the dermatology and rheumatology departments at our institution. The treating dermatologist (M.B.T.) obtained a 4-mm punch biopsy from the right lower leg and LCV was shown on histology. The patient completed a 14-day course of doxycycline and amoxicillin without resolution of the eruption. After an extensive investigation, the treating rheumatologist concluded that the LCV was idiopathic or secondary to an infection or drug exposure. The rheumatologist started the patient on oral prednisone for the chronic symptomatic LCV, but she was intolerant of this medication and discontinued it after 1 week. Our dermatology clinic started her on triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, but she continued to experience new and worsening lesions. At her follow-up appointment 1 month later, triamcinolone cream was discontinued and dapsone gel 5% twice daily was started. She experienced resolution of her previously recalcitrant LCV within 3 weeks (Figure, B).

Comment

Established therapies for LCV carry serious side-effect profiles, which can preclude their use.5 Therefore, a topical therapeutic alternative for LCV would be ideal. Systemic prednisone is the first-line therapy for chronic and/or symptomatic LCV, but its side effects include suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, immunosuppression, osteonecrosis, and glucose intolerance.5 Colchicine therapy carries risks for blood dyscrasia, immunosuppression, and gastrointestinal tract upset. Systemic dapsone also is an effective therapy for chronic and/or symptomatic LCV.5,6 However, systemic dapsone requires glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency screening and routine monitoring of blood counts, and it also carries the risk for serious adverse effects including neuropathy, blood dyscrasia, and hypersensitivity syndrome.5,6 Topical dapsone may provide similar efficacy with far fewer adverse effects and has proven to be a safe treatment of acne, even when used in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. It displays low systemic absorption and does not accumulate over time once a steady state is reached.7 It also has been shown to be beneficial in other vasculopathies such as erythema elevatum diutinum and in other neutrophilic inflammatory disorders such as pyoderma gangrenosum.8,9 A case of methemoglobinemia due to topical dapsone has been reported.10 Although this effect is rare, clinicians should be aware of such adverse effects when using medications for off-label purposes.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis can spontaneously resolve; however, our patient’s disease was chronic for several months, and she continued to develop new lesions without signs of resolution. After initiating topical dapsone, she experienced resolution within 3 weeks.

Conclusion

Topical dapsone is a novel approach for treating LCV. Given this drug’s favorable side-effect profile compared to the currently available therapeutic alternatives, we believe it is a reasonable option in select patients. Further investigation is needed to prove its efficacy, but it could be an ideal alternative for patients with contraindications to traditional therapies and/or for those unable to tolerate systemic therapy.

- Koutkia P, Mylonakis E, Rounds S, et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis: an update for the clinician. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:315-322.

- Af Ekenstam E, Callen JP. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. clinical and laboratory features of 82 patients seen in private practice. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:484-489.

- Gyselbrecht L, de Keyser F, Ongenae K, et al. Etiological factors and underlying conditions in patientswith leucocytoclastic vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14:665-668.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucglà A, et al. Colchicine in the treatment of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. results of a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1399-1402.

- Sunderkotter C, Bonsmann G, Sindrilaru A, et al. Management of leukocytoclastic vasculitis: clinical review. J Dermatol Treat. 2005;16:193-206.

- Zhu YI, Stiller MJ. Dapsone and sulfones in dermatology: overview and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:420-434.

- Stotland M, Shalita AR, Kissling RF. Dapsone 5% gel: a review of its efficacy and safety in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:221-227.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, et al. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:481-484.

- Handler MZ, Hamilton H, Aires D. Treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed dapsone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1059-1061.

- Swartzentruber GS, Yanta JH, Pizon AF. Methemoglobi-nemia as a complication of topical dapsone. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:491-492.

- Koutkia P, Mylonakis E, Rounds S, et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis: an update for the clinician. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:315-322.

- Af Ekenstam E, Callen JP. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. clinical and laboratory features of 82 patients seen in private practice. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:484-489.

- Gyselbrecht L, de Keyser F, Ongenae K, et al. Etiological factors and underlying conditions in patientswith leucocytoclastic vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14:665-668.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucglà A, et al. Colchicine in the treatment of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. results of a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1399-1402.

- Sunderkotter C, Bonsmann G, Sindrilaru A, et al. Management of leukocytoclastic vasculitis: clinical review. J Dermatol Treat. 2005;16:193-206.

- Zhu YI, Stiller MJ. Dapsone and sulfones in dermatology: overview and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:420-434.

- Stotland M, Shalita AR, Kissling RF. Dapsone 5% gel: a review of its efficacy and safety in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:221-227.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, et al. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:481-484.

- Handler MZ, Hamilton H, Aires D. Treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed dapsone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1059-1061.

- Swartzentruber GS, Yanta JH, Pizon AF. Methemoglobi-nemia as a complication of topical dapsone. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:491-492.

Practice Points

- Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is characterized by inflammation of small vessels with characteristic clinical findings of petechiae and palpable purpura.

- Leukocytoclastic vasculitis often spontaneously resolves within weeks and requires only symptomatic treatment, but chronic or severe disease can require systemic medical treatment with agents such as colchicine, dapsone, and corticosteroids.