User login

How to refine your approach to peripheral arterial disease

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD), the progressive disorder that results in ischemia to distal vascular territories as a result of atherosclerosis, spans a wide range of presentations, from minimally symptomatic disease to limb ischemia secondary to acute or chronic occlusion.

The prevalence of PAD is variable, due to differing diagnostic criteria used in studies, but PAD appears to affect 1 in every 22 people older than age 40.1 However, since PAD incidence increases with age, it is increasing in prevalence as the US population ages.1-3

PAD is associated with increased hospitalizations and decreased quality of life.4 Patients with PAD have an estimated 30% 5-year risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from a vascular cause.3

Screening. Although PAD is underdiagnosed and appears to be undertreated,3 population-based screening for PAD in asymptomatic patients is not recommended. A Cochrane review found no studies evaluating the benefit of asymptomatic population-based screening.5 Similarly, in 2018, the USPSTF performed a comprehensive review and found no studies to support routine screening and determined there was insufficient evidence to recommend it.6,7

Risk factors and associated comorbidities

PAD risk factors, like the ones detailed below, have a potentiating effect. The presence of 2 risk factors doubles PAD risk, while 3 or more risk factors increase PAD risk by a factor of 10.1

Increasing age is the greatest single risk factor for PAD.1,2,8,9 Researchers using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that the prevalence of PAD increased from 1.4% in individuals ages 40 to 49 years to almost 17% in those age 70 or older.1

Demographic characteristics. Most studies demonstrate a higher risk for PAD in men.1-3,10 African-American patients have more than twice the risk for PAD, compared with Whites, even after adjustment for the increased prevalence of associated diseases such as hypertension and diabetes in this population.1-3,10

Continue to: Genetics...

Genetics. A study performed by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute suggested that genetic correlations between twins were more important than environmental factors in the development of PAD.11

Smoking. Most population studies show smoking to be the greatest modifiable risk factor for PAD. An analysis of the NHANES data yielded an odds ratio (OR) of 4.1 for current smokers and of 1.8 for former smokers.1 Risk increases linearly with cumulative years of smoking.1,2,9,10

Diabetes is another significant modifiable risk factor, increasing PAD risk by 2.5 times.2 Diabetes is also associated with increases in functional limitation from claudication, risk for acute coronary syndrome, and progression to amputation.1

Hypertension nearly doubles the risk for PAD, and poor control further increases this risk.2,9,10

Chronic kidney disease (CKD). Patients with CKD have a progressively higher prevalence of PAD with worsening renal function.1 There is also an association between CKD and increased morbidity, revascularization failure, and increased mortality.1

Two additional risk factors that are less well understood are dyslipidemia and chronic inflammation. There is conflicting data regarding the role of individual components of cholesterol and their effect on PAD, although lipoprotein (a) has been shown to be an independent risk factor for both the development and progression of PAD.12 Similarly, chronic inflammation has been shown to play a role in the initiation and progression of the disease, although the role of inflammatory markers in evaluation and treatment is unclear and assessment for these purposes is not currently recommended.12,13

Continue to: Diagnosis...

Diagnosis

Clinical presentation

Lower extremity pain is the hallmark symptom of PAD, but presentation varies. The classic presentation is claudication, pain within a defined muscle group that occurs with exertion and is relieved by rest. Claudication is most common in the calf but also occurs in the buttock/thigh and the foot.

However, most patients with PAD present with pain that does not fit the definition of claudication. Patients with comorbidities, physical inactivity, and neuropathy are more likely to present with atypical pain.14 These patients may demonstrate critical or acute limb ischemia, characterized by pain at rest and most often localized to the forefoot and toes. Patients with critical limb ischemia may also present with nonhealing wounds/ulcers or gangrene.15

Physical exam findings can support the diagnosis of PAD, but none are reliable enough to rule the diagnosis in or out. Findings suggestive of PAD include cool skin, presence of a bruit (iliac, femoral, or popliteal), and palpable pulse abnormality. Multiple abnormal physical exam findings increase the likelihood of PAD, while the absence of a bruit or palpable pulse abnormality makes PAD less likely.16 In patients with PAD, an associated wound/ulcer is most often distal in the foot and usually appears dry.17

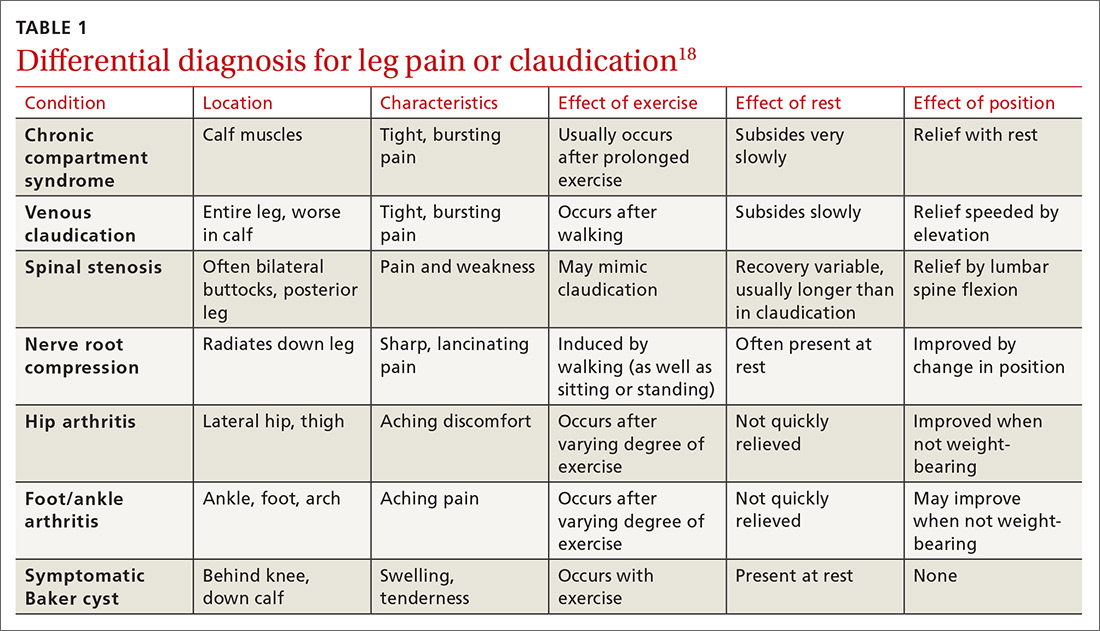

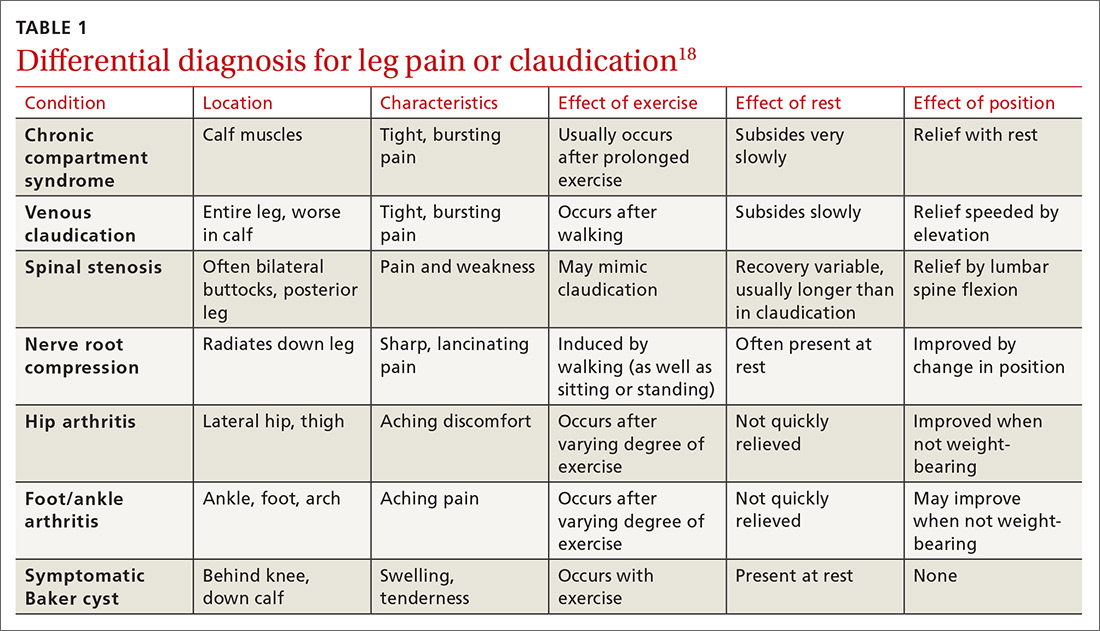

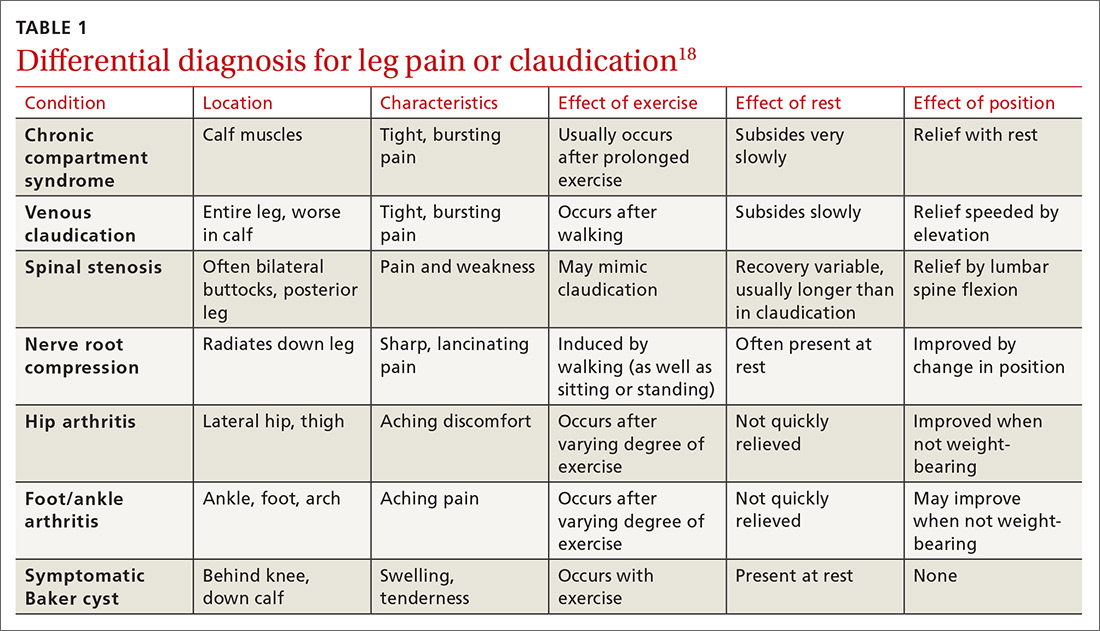

The differential diagnosis for intermittent leg pain is broad and includes neurologic, musculoskeletal, and venous etiologies. Table 118 lists some common alternate diagnoses for patients presenting with leg pain or claudication.

Continue to: Diagnostic testing...

Diagnostic testing

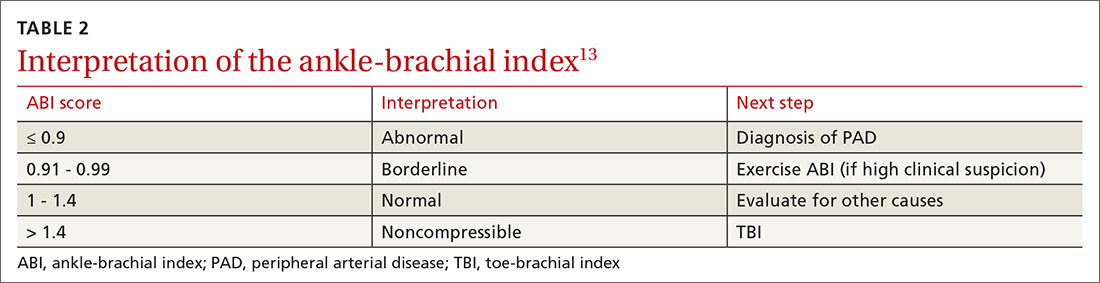

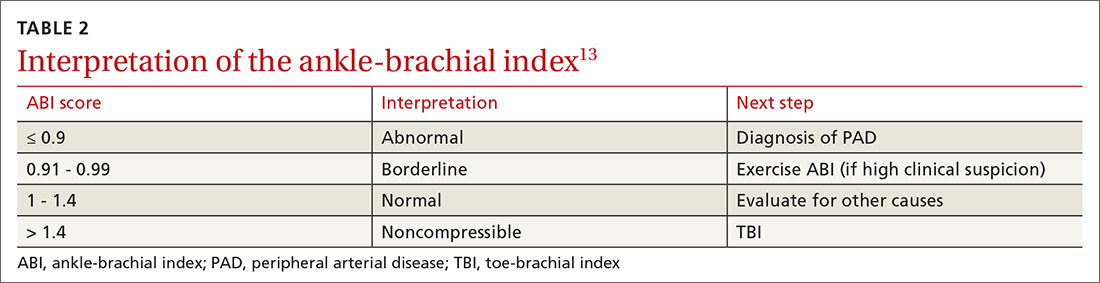

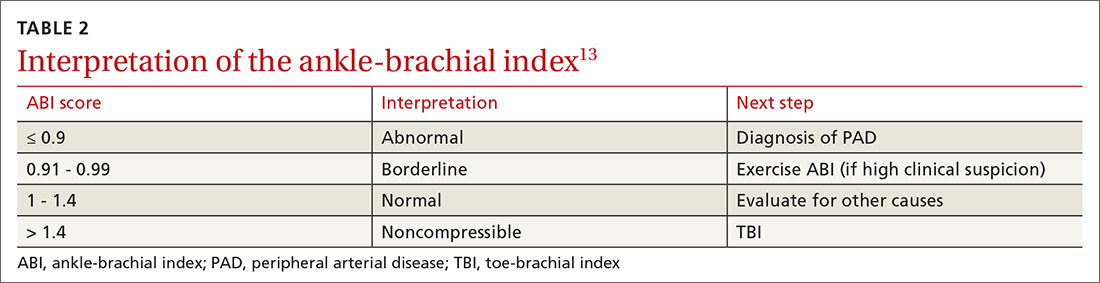

An ankle-brachial index (ABI) test should be performed in patients with history or physical exam findings suggestive of PAD. A resting ABI is performed with the patient in the supine position, with measurement of systolic blood pressure in both arms and ankles using a Doppler ultrasound device. Table 213 outlines ABI scoring and interpretation.

An ABI > 1.4 is an invalid measurement, indicating that the arteries are too calcified to be compressed. These highly elevated ABI measurements are common in patients with diabetes and/or advanced CKD. In these patients, a toe-brachial index (TBI) test should be performed, because the digital arteries are almost always compressible.13

Patients with symptomatic PAD who are under consideration for revascularization may benefit from radiologic imaging of the lower extremities with duplex ultrasound, computed tomography angiography, or magnetic resonance angiography to determine the anatomic location and severity of stenosis.13

Management of PAD

Lifestyle interventions

For patients with PAD, lifestyle modifications are an essential—but challenging—component of disease management.

Continue to: Smoking cessation...

Smoking cessation. As with other atherosclerotic diseases, PAD progression is strongly correlated with smoking. A trial involving 204 active smokers with PAD showed that 5-year mortality and amputation rates dropped by more than half in those who quit smoking within a year, with numbers needed to treat (NNT) of 6 for mortality and 5 for amputation.19 Because of this dramatic effect, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines encourage providers to address smoking at every visit and use cessation programs and medication to increase quit rates.13

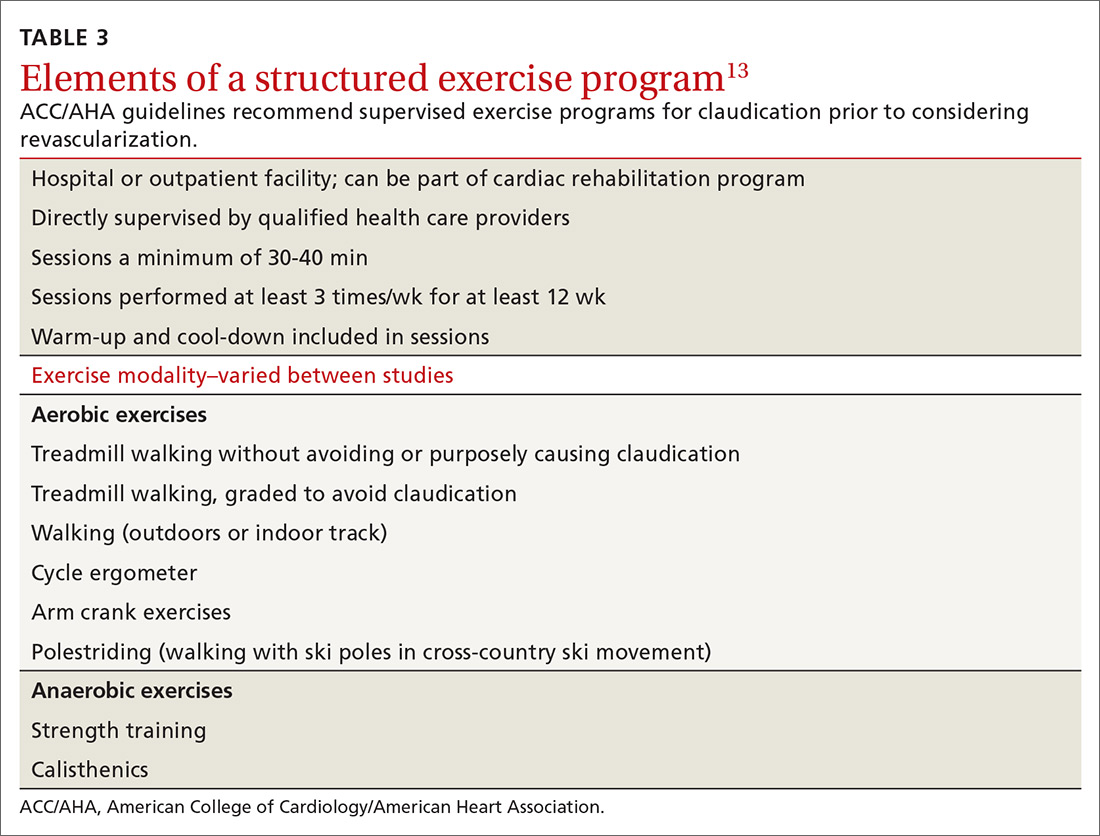

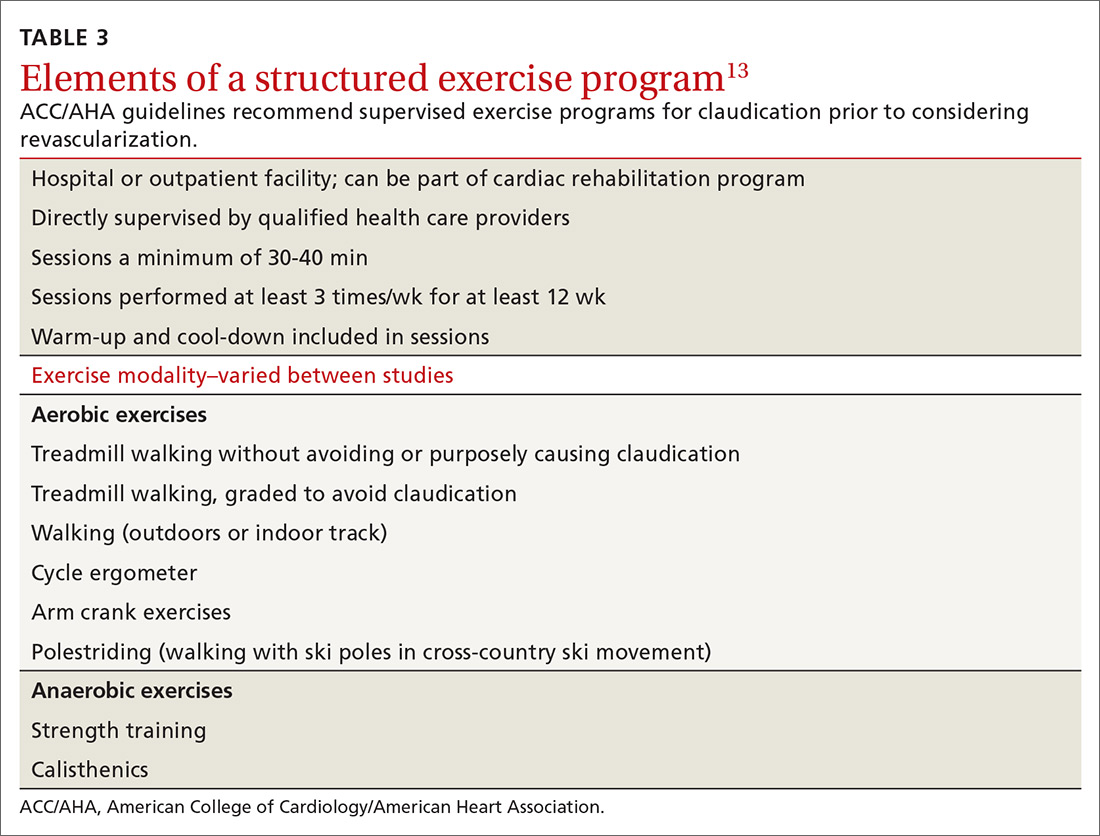

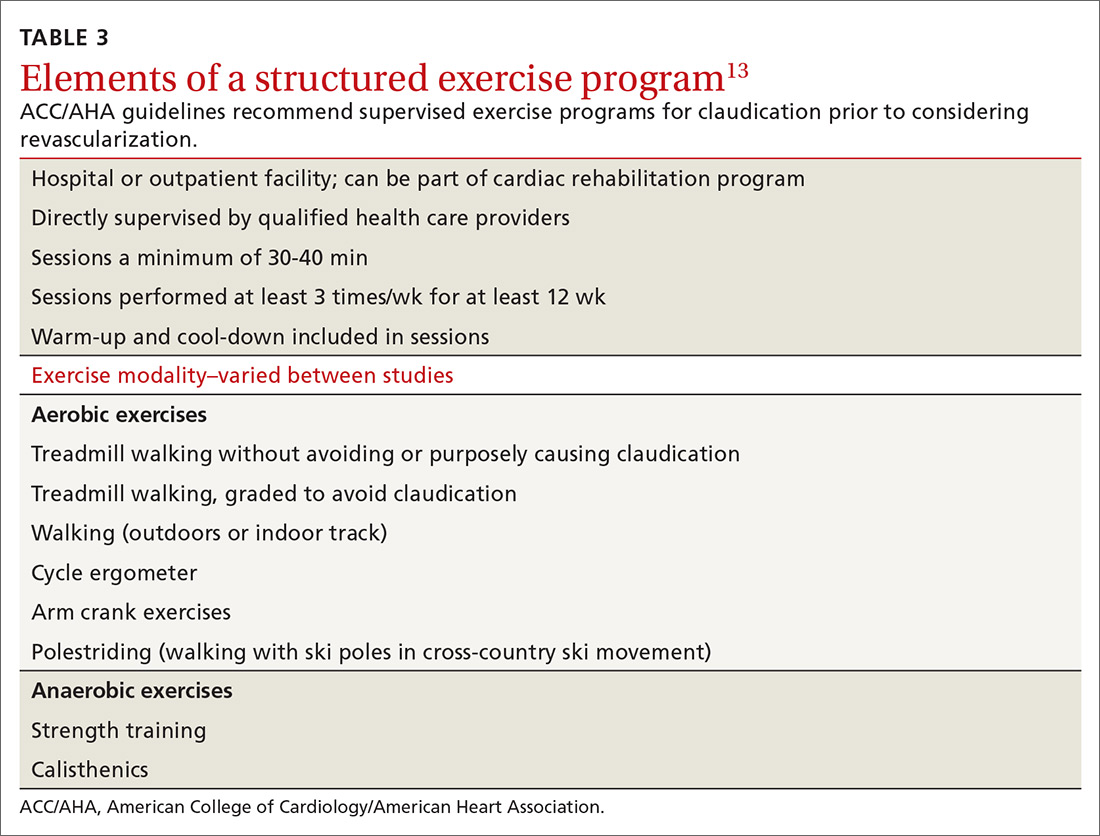

Exercise may be the most important intervention for PAD. A 2017 Cochrane review found that supervised, structured exercise programs increase pain-free and maximal walking distances by at least 20% and also improve physical and mental quality of life.20 In a trial involving 111 patients with aortoiliac PAD, supervised exercise plus medical care led to greater functional improvement than either revascularization plus medical care or medical care alone.21 In a 2018 Cochrane review, neither revascularization or revascularization added to supervised exercise were better than supervised exercise alone.22 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend supervised exercise programs for claudication prior to considering revascularization.13TABLE 313 outlines the components of a structured exercise program.

Unfortunately, the benefit of these programs has been difficult to reproduce without supervision. Another 2018 Cochrane review demonstrated significant improvement with supervised exercise and no clear improvement in patients given home exercise or advice to walk.23 A recent study examined the effect of having patients use a wearable fitness tracker for home exercise and demonstrated no benefit over usual care.24

Diet. There is some evidence that dietary interventions can prevent and possibly improve PAD. A large randomized controlled trial showed that a Mediterranean diet lowered rates of PAD over 1 year compared to a low-fat diet, with an NNT of 336 if supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil and 448 if supplemented with nuts.25 A small trial of 25 patients who consumed non-soy legumes daily for 8 weeks showed average ABI improvement of 6%, although there was no control group.26

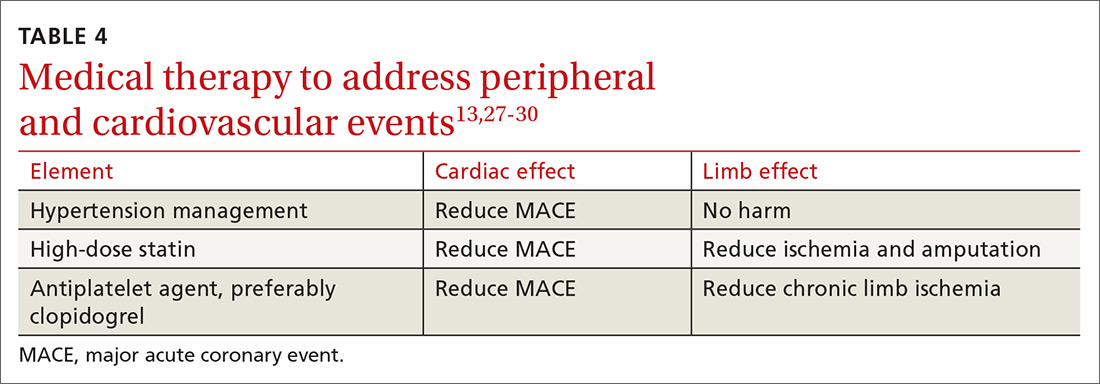

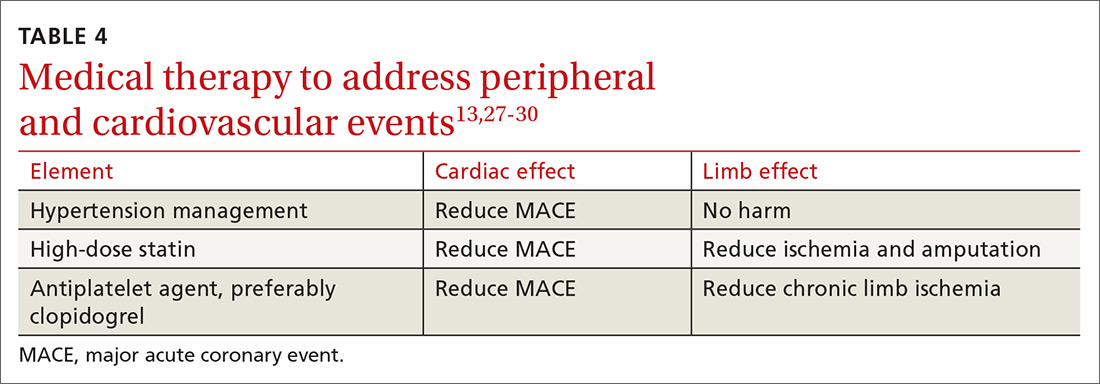

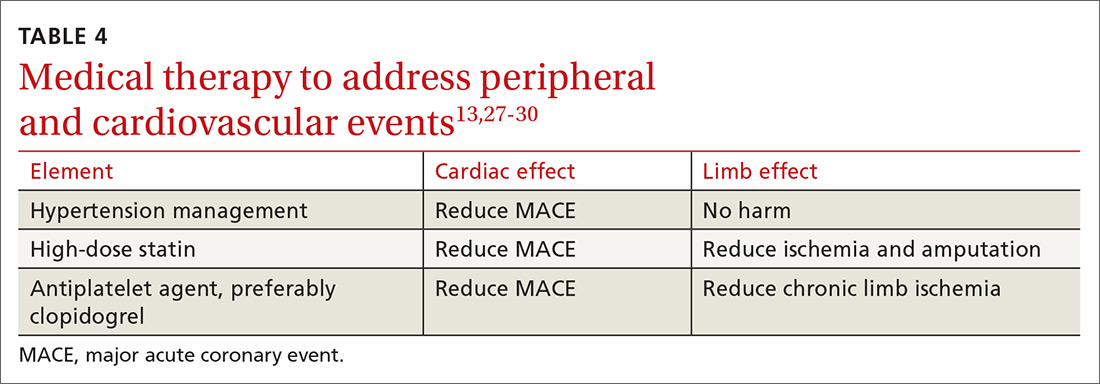

Medical therapy to address peripheral and cardiovascular events

Standard medical therapy for coronary artery disease (CAD) is recommended for patients with PAD to reduce cardiovascular and limb events. For example, treatment of hypertension reduces cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, and studies verify that lowering blood pressure does not worsen claudication or limb perfusion.

13TABLE 413,27-30 outlines the options for medical therapy.

Continue to: Statins...

Statins reduce cardiovascular events in PAD patients. A large study demonstrated that 40 mg of simvastatin has an NNT of 21 to prevent a coronary or cerebrovascular event in PAD, similar to the NNT of 23 seen in treatment of CAD.27 Statins also reduce adverse limb outcomes. A registry of atherosclerosis patients showed that statins have an NNT of 56 to prevent amputation in PAD and an NNT of 28 to prevent worsening claudication, critical limb ischemia, revascularization, or amputation.28

Antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel is recommended for symptomatic patients and for asymptomatic patients with an ABI ≤ 0.9.13 A Cochrane review demonstrated significantly reduced mortality with nonaspirin antiplatelet agents vs aspirin (NNT = 94) without increase in major bleeding.29 Only British guidelines specifically recommend clopidogrel over aspirin.31

Dual antiplatelet therapy has not shown consistent benefits over aspirin alone. ACC/AHA guidelines state that dual antiplatelet therapy is not well established for PAD but may be reasonable after revascularization.13

Voraxapar is a novel antiplatelet agent that targets the thrombin-binding receptor on platelets. However, trials show no significant coronary benefit, and slight reductions in acute limb ischemia are offset by increases in major bleeding.13

For patients receiving medical therapy, ongoing evaluation and treatment should be based on claudication symptoms and clinical assessment.

Medical therapy for claudication

Several medications have been proposed for symptomatic treatment of intermittent claudication. Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor with the best risk-benefit ratio. A Cochrane review showed improvements in maximal and pain-free walking distances compared to placebo and improvements in quality of life with cilostazol 100 mg taken twice daily.32 Adverse effects included headache, dizziness, palpitations, and diarrhea.29

Continue to: Pentoxifylline...

Pentoxifylline is another phosphodiesterase inhibitor with less evidence of improvement, higher adverse effect rates, and more frequent dosing. It is not recommended for treatment of intermittent claudication.13,33

Supplements. Padma 28, a Tibetan herbal formulation, appears to improve maximal walking distance with adverse effect rates similar to placebo.34 Other supplements, including vitamin E, ginkgo biloba, and omega-3 fatty acids, have no evidence of benefit.35-37

When revascularizationis needed

Patients who develop limb ischemia or lifestyle-limiting claudication despite conservative therapy are candidates for revascularization. Endovascular techniques include angioplasty, stenting, atherectomy, and precise medication delivery. Surgical approaches mainly consist of thrombectomy and bypass grafting. For intermittent claudication despite conservative care, ACC/AHA guidelines state endovascular procedures are appropriate for aortoiliac disease and reasonable for femoropopliteal disease, but unproven for infrapopliteal disease.13

Acute limb ischemia is an emergency requiring immediate intervention. Two trials revealed identical overall and amputation-free survival rates for percutaneous thrombolysis and surgical thrombectomy.38,39 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend anticoagulation with heparin followed by the revascularization technique that will most rapidly restore arterial flow.13

For chronic limb ischemia, a large trial showed angioplasty had lower initial morbidity, length of hospitalization, and cost than surgical repair. However, surgical mortality was lower after 2 years.40 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend either surgery or endovascular procedures and propose initial endovascular treatment followed by surgery if needed.13 After revascularization, the patient should be followed periodically with a clinical evaluation and ABI measurement with further consideration for routine duplex ultrasound surveillance.13

Outcomes

Patients with PAD have variable outcomes. About 70% to 80% of patients with this diagnosis will have a stable disease process with no worsening of symptoms, 10% to 20% will experience worsening symptoms over time, 5% to 10% will require revascularization within 5 years of diagnosis, and 1% to 5% will progress to critical limb ischemia, which has a 5-year amputation rate of 1% to 4%.2 Patients who require amputation have poor outcomes: Within 2 years, 30% are dead and 15% have had further amputations.18

In addition to the morbidity and mortality from its own progression, PAD is an important predictor of CAD and is associated with a significant elevation in morbidity and mortality from CAD. One small but well-designed prospective cohort study found that patients with PAD had a more than 6-fold increased risk of death from CAD than did patients without PAD.41

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Francesca Cimino, MD, FAAFP, for her help in reviewing this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, DO, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL 32214; dustinksmith@yahoo.com

1. Eraso LH, Fukaya E, Mohler ER 3rd, et al. Peripheral arterial disease, prevalence and cumulative risk factor profile analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:704-711.

2. Pasternak RC, Criqui MH, Benjamin EJ, et al; American Heart Association. Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference: Writing Group I: epidemiology. Circulation. 2004;109:2605-2612.

3. Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317-1324.

4. Olin JW, Sealove BA. Peripheral artery disease: current insight into the disease and its diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:678-692.

5. Andras A, Ferkert B. Screening for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD010835.

6. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Redmond N, et al. Screening for peripheral artery disease using ankle-brachial index: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:184-196.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease risk assessment with ankle-brachial index: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;230:177-183.

8. American Heart Association Writing Group 2. Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Symposium II: screening for atherosclerotic vascular diseases: should nationwide programs be instituted? Circulation. 2008;118:2830-2836.

9. Berger JS, Hochman J, Lobach I, et al. Modifiable risk factor burden and the prevalence of peripheral artery disease in different vascular territories. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:673-681.

10. Joosten MM, Pai JK, Bertoia ML, et al. Associations between conventional cardiovascular risk factors and risk of peripheral artery disease in men. JAMA. 2012;308:1660-1667.

11. Carmelli D, Fabsitz RR, Swan GE, et al. Contribution of genetic and environmental influences to ankle-brachial blood pressure index in the NHLBI Twin Study. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:452-458.

12. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, et al. Risk factors for progression of peripheral arterial disease in large and small vessels. Circulation. 2006;113:2623-2629.

13. Gerald-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e726-e779.

14. McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286:1599-1606.

15. Cranley JJ. Ischemic rest pain. Arch Surg. 1969;98:187-188.

16. Khan NA, Rahim SA, Anand SS, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295:536-546.

17. Wennberg PW. Approach to the patient with peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2013;128:2241-2250.

18. Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II). Eur J Vas Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:S1-S75.

19. Armstrong EJ, Wu J, Singh GD, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with decreased mortality and improved amputation-free survival among patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1565-1571.

20. Lane R, Harwood A, Watson L, et al. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(12):CD000990.

21. Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, et al; CLEVER Study Investigators. Supervised exercise versus primary stenting for claudication resulting from aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: six-month outcomes from the claudication: exercise versus endoluminal revascularization (CLEVER) study. Circulation. 2012;125:130-139.

22. Fakhry F, Fokkenrood HJP, Pronk S, et al. Endovascular revascularization versus conservative management for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(3):CD010512.

23. Hageman D, Fokkenrood HJ, Gommans LN, et al. Supervised exercise therapy versus home-based exercise therapy versus walking advice for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(4):CD005263.

24. McDermott MM, Spring B, Berger JS, et al. Effect of a home-based exercise intervention of wearable technology and telephone coaching on walking performance in peripheral artery disease: the HONOR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1665-1676.

25. Ruiz-Canela M, Estruch R, Corella D, et al. Association of Mediterranean diet with peripheral artery disease: the PREDIMED randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:415-417.

26. Zahradka P, Wright B, Weighell W, et al. Daily non-soy legume consumption reverses vascular impairment due to peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2013;230:310-314.

27. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. Randomized trial of the effects of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin on peripheral vascular and other major vascular outcomes in 20536 people with peripheral arterial disease and other high-risk conditions. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:645-655.

28. Kumbhani DJ, Steg G, Cannon CP, et al. Statin therapy and long-term adverse limb outcomes in patients with peripheral artery disease: insights from the REACH registry. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2864-2872.

29. Wong PF, Chong LY, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Antiplatelet agents for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11):CD001272.

30. Critical Leg Ischaemia Prevention Study (CLIPS) Group, Catalano M, Born G, Peto R. Prevention of serious vascular events by aspirin amongst patients with peripheral arterial disease: randomized, double-blind trial. J Intern Med. 2007;261:276-284.

31. Morley RL, Sharma A, Horsch AD, et al. Peripheral artery disease. BMJ. 2018;360:j5842.

32. Bedenis R, Stewart M, Cleanthis M, et al. Cilostazol for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD003748.

33. Salhiyyah K, Forster R, Senanayake E, et al. Pentoxifylline for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD005262.

34. Stewart M, Morling JR, Maxwell H. Padma 28 for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(3):CD007371.

35. Kleijnen J, Mackerras D. Vitamin E for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(1):CD000987.

36. Nicolai SPA, Kruidenior LM, Bendermacher BLW, et al. Ginkgo biloba for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD006888.

37. Campbell A, Price J, Hiatt WR. Omega-3 fatty acids for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD003833.

38. American Surgical Association, New York Surgical Society, Philadelphia Academy of Surgery, Southern Surgical Association (US), Central Surgical Association. Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity: the STILE trial. Ann Surg. 1994;220:251-268.

39. Ouriel K, Veith FJ, Sasahara AA.

40. Bradbury AW, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FGR, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL): multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1925-1934.

41. Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:381-386.

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD), the progressive disorder that results in ischemia to distal vascular territories as a result of atherosclerosis, spans a wide range of presentations, from minimally symptomatic disease to limb ischemia secondary to acute or chronic occlusion.

The prevalence of PAD is variable, due to differing diagnostic criteria used in studies, but PAD appears to affect 1 in every 22 people older than age 40.1 However, since PAD incidence increases with age, it is increasing in prevalence as the US population ages.1-3

PAD is associated with increased hospitalizations and decreased quality of life.4 Patients with PAD have an estimated 30% 5-year risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from a vascular cause.3

Screening. Although PAD is underdiagnosed and appears to be undertreated,3 population-based screening for PAD in asymptomatic patients is not recommended. A Cochrane review found no studies evaluating the benefit of asymptomatic population-based screening.5 Similarly, in 2018, the USPSTF performed a comprehensive review and found no studies to support routine screening and determined there was insufficient evidence to recommend it.6,7

Risk factors and associated comorbidities

PAD risk factors, like the ones detailed below, have a potentiating effect. The presence of 2 risk factors doubles PAD risk, while 3 or more risk factors increase PAD risk by a factor of 10.1

Increasing age is the greatest single risk factor for PAD.1,2,8,9 Researchers using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that the prevalence of PAD increased from 1.4% in individuals ages 40 to 49 years to almost 17% in those age 70 or older.1

Demographic characteristics. Most studies demonstrate a higher risk for PAD in men.1-3,10 African-American patients have more than twice the risk for PAD, compared with Whites, even after adjustment for the increased prevalence of associated diseases such as hypertension and diabetes in this population.1-3,10

Continue to: Genetics...

Genetics. A study performed by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute suggested that genetic correlations between twins were more important than environmental factors in the development of PAD.11

Smoking. Most population studies show smoking to be the greatest modifiable risk factor for PAD. An analysis of the NHANES data yielded an odds ratio (OR) of 4.1 for current smokers and of 1.8 for former smokers.1 Risk increases linearly with cumulative years of smoking.1,2,9,10

Diabetes is another significant modifiable risk factor, increasing PAD risk by 2.5 times.2 Diabetes is also associated with increases in functional limitation from claudication, risk for acute coronary syndrome, and progression to amputation.1

Hypertension nearly doubles the risk for PAD, and poor control further increases this risk.2,9,10

Chronic kidney disease (CKD). Patients with CKD have a progressively higher prevalence of PAD with worsening renal function.1 There is also an association between CKD and increased morbidity, revascularization failure, and increased mortality.1

Two additional risk factors that are less well understood are dyslipidemia and chronic inflammation. There is conflicting data regarding the role of individual components of cholesterol and their effect on PAD, although lipoprotein (a) has been shown to be an independent risk factor for both the development and progression of PAD.12 Similarly, chronic inflammation has been shown to play a role in the initiation and progression of the disease, although the role of inflammatory markers in evaluation and treatment is unclear and assessment for these purposes is not currently recommended.12,13

Continue to: Diagnosis...

Diagnosis

Clinical presentation

Lower extremity pain is the hallmark symptom of PAD, but presentation varies. The classic presentation is claudication, pain within a defined muscle group that occurs with exertion and is relieved by rest. Claudication is most common in the calf but also occurs in the buttock/thigh and the foot.

However, most patients with PAD present with pain that does not fit the definition of claudication. Patients with comorbidities, physical inactivity, and neuropathy are more likely to present with atypical pain.14 These patients may demonstrate critical or acute limb ischemia, characterized by pain at rest and most often localized to the forefoot and toes. Patients with critical limb ischemia may also present with nonhealing wounds/ulcers or gangrene.15

Physical exam findings can support the diagnosis of PAD, but none are reliable enough to rule the diagnosis in or out. Findings suggestive of PAD include cool skin, presence of a bruit (iliac, femoral, or popliteal), and palpable pulse abnormality. Multiple abnormal physical exam findings increase the likelihood of PAD, while the absence of a bruit or palpable pulse abnormality makes PAD less likely.16 In patients with PAD, an associated wound/ulcer is most often distal in the foot and usually appears dry.17

The differential diagnosis for intermittent leg pain is broad and includes neurologic, musculoskeletal, and venous etiologies. Table 118 lists some common alternate diagnoses for patients presenting with leg pain or claudication.

Continue to: Diagnostic testing...

Diagnostic testing

An ankle-brachial index (ABI) test should be performed in patients with history or physical exam findings suggestive of PAD. A resting ABI is performed with the patient in the supine position, with measurement of systolic blood pressure in both arms and ankles using a Doppler ultrasound device. Table 213 outlines ABI scoring and interpretation.

An ABI > 1.4 is an invalid measurement, indicating that the arteries are too calcified to be compressed. These highly elevated ABI measurements are common in patients with diabetes and/or advanced CKD. In these patients, a toe-brachial index (TBI) test should be performed, because the digital arteries are almost always compressible.13

Patients with symptomatic PAD who are under consideration for revascularization may benefit from radiologic imaging of the lower extremities with duplex ultrasound, computed tomography angiography, or magnetic resonance angiography to determine the anatomic location and severity of stenosis.13

Management of PAD

Lifestyle interventions

For patients with PAD, lifestyle modifications are an essential—but challenging—component of disease management.

Continue to: Smoking cessation...

Smoking cessation. As with other atherosclerotic diseases, PAD progression is strongly correlated with smoking. A trial involving 204 active smokers with PAD showed that 5-year mortality and amputation rates dropped by more than half in those who quit smoking within a year, with numbers needed to treat (NNT) of 6 for mortality and 5 for amputation.19 Because of this dramatic effect, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines encourage providers to address smoking at every visit and use cessation programs and medication to increase quit rates.13

Exercise may be the most important intervention for PAD. A 2017 Cochrane review found that supervised, structured exercise programs increase pain-free and maximal walking distances by at least 20% and also improve physical and mental quality of life.20 In a trial involving 111 patients with aortoiliac PAD, supervised exercise plus medical care led to greater functional improvement than either revascularization plus medical care or medical care alone.21 In a 2018 Cochrane review, neither revascularization or revascularization added to supervised exercise were better than supervised exercise alone.22 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend supervised exercise programs for claudication prior to considering revascularization.13TABLE 313 outlines the components of a structured exercise program.

Unfortunately, the benefit of these programs has been difficult to reproduce without supervision. Another 2018 Cochrane review demonstrated significant improvement with supervised exercise and no clear improvement in patients given home exercise or advice to walk.23 A recent study examined the effect of having patients use a wearable fitness tracker for home exercise and demonstrated no benefit over usual care.24

Diet. There is some evidence that dietary interventions can prevent and possibly improve PAD. A large randomized controlled trial showed that a Mediterranean diet lowered rates of PAD over 1 year compared to a low-fat diet, with an NNT of 336 if supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil and 448 if supplemented with nuts.25 A small trial of 25 patients who consumed non-soy legumes daily for 8 weeks showed average ABI improvement of 6%, although there was no control group.26

Medical therapy to address peripheral and cardiovascular events

Standard medical therapy for coronary artery disease (CAD) is recommended for patients with PAD to reduce cardiovascular and limb events. For example, treatment of hypertension reduces cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, and studies verify that lowering blood pressure does not worsen claudication or limb perfusion.

13TABLE 413,27-30 outlines the options for medical therapy.

Continue to: Statins...

Statins reduce cardiovascular events in PAD patients. A large study demonstrated that 40 mg of simvastatin has an NNT of 21 to prevent a coronary or cerebrovascular event in PAD, similar to the NNT of 23 seen in treatment of CAD.27 Statins also reduce adverse limb outcomes. A registry of atherosclerosis patients showed that statins have an NNT of 56 to prevent amputation in PAD and an NNT of 28 to prevent worsening claudication, critical limb ischemia, revascularization, or amputation.28

Antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel is recommended for symptomatic patients and for asymptomatic patients with an ABI ≤ 0.9.13 A Cochrane review demonstrated significantly reduced mortality with nonaspirin antiplatelet agents vs aspirin (NNT = 94) without increase in major bleeding.29 Only British guidelines specifically recommend clopidogrel over aspirin.31

Dual antiplatelet therapy has not shown consistent benefits over aspirin alone. ACC/AHA guidelines state that dual antiplatelet therapy is not well established for PAD but may be reasonable after revascularization.13

Voraxapar is a novel antiplatelet agent that targets the thrombin-binding receptor on platelets. However, trials show no significant coronary benefit, and slight reductions in acute limb ischemia are offset by increases in major bleeding.13

For patients receiving medical therapy, ongoing evaluation and treatment should be based on claudication symptoms and clinical assessment.

Medical therapy for claudication

Several medications have been proposed for symptomatic treatment of intermittent claudication. Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor with the best risk-benefit ratio. A Cochrane review showed improvements in maximal and pain-free walking distances compared to placebo and improvements in quality of life with cilostazol 100 mg taken twice daily.32 Adverse effects included headache, dizziness, palpitations, and diarrhea.29

Continue to: Pentoxifylline...

Pentoxifylline is another phosphodiesterase inhibitor with less evidence of improvement, higher adverse effect rates, and more frequent dosing. It is not recommended for treatment of intermittent claudication.13,33

Supplements. Padma 28, a Tibetan herbal formulation, appears to improve maximal walking distance with adverse effect rates similar to placebo.34 Other supplements, including vitamin E, ginkgo biloba, and omega-3 fatty acids, have no evidence of benefit.35-37

When revascularizationis needed

Patients who develop limb ischemia or lifestyle-limiting claudication despite conservative therapy are candidates for revascularization. Endovascular techniques include angioplasty, stenting, atherectomy, and precise medication delivery. Surgical approaches mainly consist of thrombectomy and bypass grafting. For intermittent claudication despite conservative care, ACC/AHA guidelines state endovascular procedures are appropriate for aortoiliac disease and reasonable for femoropopliteal disease, but unproven for infrapopliteal disease.13

Acute limb ischemia is an emergency requiring immediate intervention. Two trials revealed identical overall and amputation-free survival rates for percutaneous thrombolysis and surgical thrombectomy.38,39 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend anticoagulation with heparin followed by the revascularization technique that will most rapidly restore arterial flow.13

For chronic limb ischemia, a large trial showed angioplasty had lower initial morbidity, length of hospitalization, and cost than surgical repair. However, surgical mortality was lower after 2 years.40 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend either surgery or endovascular procedures and propose initial endovascular treatment followed by surgery if needed.13 After revascularization, the patient should be followed periodically with a clinical evaluation and ABI measurement with further consideration for routine duplex ultrasound surveillance.13

Outcomes

Patients with PAD have variable outcomes. About 70% to 80% of patients with this diagnosis will have a stable disease process with no worsening of symptoms, 10% to 20% will experience worsening symptoms over time, 5% to 10% will require revascularization within 5 years of diagnosis, and 1% to 5% will progress to critical limb ischemia, which has a 5-year amputation rate of 1% to 4%.2 Patients who require amputation have poor outcomes: Within 2 years, 30% are dead and 15% have had further amputations.18

In addition to the morbidity and mortality from its own progression, PAD is an important predictor of CAD and is associated with a significant elevation in morbidity and mortality from CAD. One small but well-designed prospective cohort study found that patients with PAD had a more than 6-fold increased risk of death from CAD than did patients without PAD.41

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Francesca Cimino, MD, FAAFP, for her help in reviewing this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, DO, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL 32214; dustinksmith@yahoo.com

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD), the progressive disorder that results in ischemia to distal vascular territories as a result of atherosclerosis, spans a wide range of presentations, from minimally symptomatic disease to limb ischemia secondary to acute or chronic occlusion.

The prevalence of PAD is variable, due to differing diagnostic criteria used in studies, but PAD appears to affect 1 in every 22 people older than age 40.1 However, since PAD incidence increases with age, it is increasing in prevalence as the US population ages.1-3

PAD is associated with increased hospitalizations and decreased quality of life.4 Patients with PAD have an estimated 30% 5-year risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from a vascular cause.3

Screening. Although PAD is underdiagnosed and appears to be undertreated,3 population-based screening for PAD in asymptomatic patients is not recommended. A Cochrane review found no studies evaluating the benefit of asymptomatic population-based screening.5 Similarly, in 2018, the USPSTF performed a comprehensive review and found no studies to support routine screening and determined there was insufficient evidence to recommend it.6,7

Risk factors and associated comorbidities

PAD risk factors, like the ones detailed below, have a potentiating effect. The presence of 2 risk factors doubles PAD risk, while 3 or more risk factors increase PAD risk by a factor of 10.1

Increasing age is the greatest single risk factor for PAD.1,2,8,9 Researchers using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that the prevalence of PAD increased from 1.4% in individuals ages 40 to 49 years to almost 17% in those age 70 or older.1

Demographic characteristics. Most studies demonstrate a higher risk for PAD in men.1-3,10 African-American patients have more than twice the risk for PAD, compared with Whites, even after adjustment for the increased prevalence of associated diseases such as hypertension and diabetes in this population.1-3,10

Continue to: Genetics...

Genetics. A study performed by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute suggested that genetic correlations between twins were more important than environmental factors in the development of PAD.11

Smoking. Most population studies show smoking to be the greatest modifiable risk factor for PAD. An analysis of the NHANES data yielded an odds ratio (OR) of 4.1 for current smokers and of 1.8 for former smokers.1 Risk increases linearly with cumulative years of smoking.1,2,9,10

Diabetes is another significant modifiable risk factor, increasing PAD risk by 2.5 times.2 Diabetes is also associated with increases in functional limitation from claudication, risk for acute coronary syndrome, and progression to amputation.1

Hypertension nearly doubles the risk for PAD, and poor control further increases this risk.2,9,10

Chronic kidney disease (CKD). Patients with CKD have a progressively higher prevalence of PAD with worsening renal function.1 There is also an association between CKD and increased morbidity, revascularization failure, and increased mortality.1

Two additional risk factors that are less well understood are dyslipidemia and chronic inflammation. There is conflicting data regarding the role of individual components of cholesterol and their effect on PAD, although lipoprotein (a) has been shown to be an independent risk factor for both the development and progression of PAD.12 Similarly, chronic inflammation has been shown to play a role in the initiation and progression of the disease, although the role of inflammatory markers in evaluation and treatment is unclear and assessment for these purposes is not currently recommended.12,13

Continue to: Diagnosis...

Diagnosis

Clinical presentation

Lower extremity pain is the hallmark symptom of PAD, but presentation varies. The classic presentation is claudication, pain within a defined muscle group that occurs with exertion and is relieved by rest. Claudication is most common in the calf but also occurs in the buttock/thigh and the foot.

However, most patients with PAD present with pain that does not fit the definition of claudication. Patients with comorbidities, physical inactivity, and neuropathy are more likely to present with atypical pain.14 These patients may demonstrate critical or acute limb ischemia, characterized by pain at rest and most often localized to the forefoot and toes. Patients with critical limb ischemia may also present with nonhealing wounds/ulcers or gangrene.15

Physical exam findings can support the diagnosis of PAD, but none are reliable enough to rule the diagnosis in or out. Findings suggestive of PAD include cool skin, presence of a bruit (iliac, femoral, or popliteal), and palpable pulse abnormality. Multiple abnormal physical exam findings increase the likelihood of PAD, while the absence of a bruit or palpable pulse abnormality makes PAD less likely.16 In patients with PAD, an associated wound/ulcer is most often distal in the foot and usually appears dry.17

The differential diagnosis for intermittent leg pain is broad and includes neurologic, musculoskeletal, and venous etiologies. Table 118 lists some common alternate diagnoses for patients presenting with leg pain or claudication.

Continue to: Diagnostic testing...

Diagnostic testing

An ankle-brachial index (ABI) test should be performed in patients with history or physical exam findings suggestive of PAD. A resting ABI is performed with the patient in the supine position, with measurement of systolic blood pressure in both arms and ankles using a Doppler ultrasound device. Table 213 outlines ABI scoring and interpretation.

An ABI > 1.4 is an invalid measurement, indicating that the arteries are too calcified to be compressed. These highly elevated ABI measurements are common in patients with diabetes and/or advanced CKD. In these patients, a toe-brachial index (TBI) test should be performed, because the digital arteries are almost always compressible.13

Patients with symptomatic PAD who are under consideration for revascularization may benefit from radiologic imaging of the lower extremities with duplex ultrasound, computed tomography angiography, or magnetic resonance angiography to determine the anatomic location and severity of stenosis.13

Management of PAD

Lifestyle interventions

For patients with PAD, lifestyle modifications are an essential—but challenging—component of disease management.

Continue to: Smoking cessation...

Smoking cessation. As with other atherosclerotic diseases, PAD progression is strongly correlated with smoking. A trial involving 204 active smokers with PAD showed that 5-year mortality and amputation rates dropped by more than half in those who quit smoking within a year, with numbers needed to treat (NNT) of 6 for mortality and 5 for amputation.19 Because of this dramatic effect, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines encourage providers to address smoking at every visit and use cessation programs and medication to increase quit rates.13

Exercise may be the most important intervention for PAD. A 2017 Cochrane review found that supervised, structured exercise programs increase pain-free and maximal walking distances by at least 20% and also improve physical and mental quality of life.20 In a trial involving 111 patients with aortoiliac PAD, supervised exercise plus medical care led to greater functional improvement than either revascularization plus medical care or medical care alone.21 In a 2018 Cochrane review, neither revascularization or revascularization added to supervised exercise were better than supervised exercise alone.22 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend supervised exercise programs for claudication prior to considering revascularization.13TABLE 313 outlines the components of a structured exercise program.

Unfortunately, the benefit of these programs has been difficult to reproduce without supervision. Another 2018 Cochrane review demonstrated significant improvement with supervised exercise and no clear improvement in patients given home exercise or advice to walk.23 A recent study examined the effect of having patients use a wearable fitness tracker for home exercise and demonstrated no benefit over usual care.24

Diet. There is some evidence that dietary interventions can prevent and possibly improve PAD. A large randomized controlled trial showed that a Mediterranean diet lowered rates of PAD over 1 year compared to a low-fat diet, with an NNT of 336 if supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil and 448 if supplemented with nuts.25 A small trial of 25 patients who consumed non-soy legumes daily for 8 weeks showed average ABI improvement of 6%, although there was no control group.26

Medical therapy to address peripheral and cardiovascular events

Standard medical therapy for coronary artery disease (CAD) is recommended for patients with PAD to reduce cardiovascular and limb events. For example, treatment of hypertension reduces cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, and studies verify that lowering blood pressure does not worsen claudication or limb perfusion.

13TABLE 413,27-30 outlines the options for medical therapy.

Continue to: Statins...

Statins reduce cardiovascular events in PAD patients. A large study demonstrated that 40 mg of simvastatin has an NNT of 21 to prevent a coronary or cerebrovascular event in PAD, similar to the NNT of 23 seen in treatment of CAD.27 Statins also reduce adverse limb outcomes. A registry of atherosclerosis patients showed that statins have an NNT of 56 to prevent amputation in PAD and an NNT of 28 to prevent worsening claudication, critical limb ischemia, revascularization, or amputation.28

Antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel is recommended for symptomatic patients and for asymptomatic patients with an ABI ≤ 0.9.13 A Cochrane review demonstrated significantly reduced mortality with nonaspirin antiplatelet agents vs aspirin (NNT = 94) without increase in major bleeding.29 Only British guidelines specifically recommend clopidogrel over aspirin.31

Dual antiplatelet therapy has not shown consistent benefits over aspirin alone. ACC/AHA guidelines state that dual antiplatelet therapy is not well established for PAD but may be reasonable after revascularization.13

Voraxapar is a novel antiplatelet agent that targets the thrombin-binding receptor on platelets. However, trials show no significant coronary benefit, and slight reductions in acute limb ischemia are offset by increases in major bleeding.13

For patients receiving medical therapy, ongoing evaluation and treatment should be based on claudication symptoms and clinical assessment.

Medical therapy for claudication

Several medications have been proposed for symptomatic treatment of intermittent claudication. Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor with the best risk-benefit ratio. A Cochrane review showed improvements in maximal and pain-free walking distances compared to placebo and improvements in quality of life with cilostazol 100 mg taken twice daily.32 Adverse effects included headache, dizziness, palpitations, and diarrhea.29

Continue to: Pentoxifylline...

Pentoxifylline is another phosphodiesterase inhibitor with less evidence of improvement, higher adverse effect rates, and more frequent dosing. It is not recommended for treatment of intermittent claudication.13,33

Supplements. Padma 28, a Tibetan herbal formulation, appears to improve maximal walking distance with adverse effect rates similar to placebo.34 Other supplements, including vitamin E, ginkgo biloba, and omega-3 fatty acids, have no evidence of benefit.35-37

When revascularizationis needed

Patients who develop limb ischemia or lifestyle-limiting claudication despite conservative therapy are candidates for revascularization. Endovascular techniques include angioplasty, stenting, atherectomy, and precise medication delivery. Surgical approaches mainly consist of thrombectomy and bypass grafting. For intermittent claudication despite conservative care, ACC/AHA guidelines state endovascular procedures are appropriate for aortoiliac disease and reasonable for femoropopliteal disease, but unproven for infrapopliteal disease.13

Acute limb ischemia is an emergency requiring immediate intervention. Two trials revealed identical overall and amputation-free survival rates for percutaneous thrombolysis and surgical thrombectomy.38,39 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend anticoagulation with heparin followed by the revascularization technique that will most rapidly restore arterial flow.13

For chronic limb ischemia, a large trial showed angioplasty had lower initial morbidity, length of hospitalization, and cost than surgical repair. However, surgical mortality was lower after 2 years.40 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend either surgery or endovascular procedures and propose initial endovascular treatment followed by surgery if needed.13 After revascularization, the patient should be followed periodically with a clinical evaluation and ABI measurement with further consideration for routine duplex ultrasound surveillance.13

Outcomes

Patients with PAD have variable outcomes. About 70% to 80% of patients with this diagnosis will have a stable disease process with no worsening of symptoms, 10% to 20% will experience worsening symptoms over time, 5% to 10% will require revascularization within 5 years of diagnosis, and 1% to 5% will progress to critical limb ischemia, which has a 5-year amputation rate of 1% to 4%.2 Patients who require amputation have poor outcomes: Within 2 years, 30% are dead and 15% have had further amputations.18

In addition to the morbidity and mortality from its own progression, PAD is an important predictor of CAD and is associated with a significant elevation in morbidity and mortality from CAD. One small but well-designed prospective cohort study found that patients with PAD had a more than 6-fold increased risk of death from CAD than did patients without PAD.41

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Francesca Cimino, MD, FAAFP, for her help in reviewing this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, DO, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL 32214; dustinksmith@yahoo.com

1. Eraso LH, Fukaya E, Mohler ER 3rd, et al. Peripheral arterial disease, prevalence and cumulative risk factor profile analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:704-711.

2. Pasternak RC, Criqui MH, Benjamin EJ, et al; American Heart Association. Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference: Writing Group I: epidemiology. Circulation. 2004;109:2605-2612.

3. Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317-1324.

4. Olin JW, Sealove BA. Peripheral artery disease: current insight into the disease and its diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:678-692.

5. Andras A, Ferkert B. Screening for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD010835.

6. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Redmond N, et al. Screening for peripheral artery disease using ankle-brachial index: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:184-196.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease risk assessment with ankle-brachial index: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;230:177-183.

8. American Heart Association Writing Group 2. Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Symposium II: screening for atherosclerotic vascular diseases: should nationwide programs be instituted? Circulation. 2008;118:2830-2836.

9. Berger JS, Hochman J, Lobach I, et al. Modifiable risk factor burden and the prevalence of peripheral artery disease in different vascular territories. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:673-681.

10. Joosten MM, Pai JK, Bertoia ML, et al. Associations between conventional cardiovascular risk factors and risk of peripheral artery disease in men. JAMA. 2012;308:1660-1667.

11. Carmelli D, Fabsitz RR, Swan GE, et al. Contribution of genetic and environmental influences to ankle-brachial blood pressure index in the NHLBI Twin Study. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:452-458.

12. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, et al. Risk factors for progression of peripheral arterial disease in large and small vessels. Circulation. 2006;113:2623-2629.

13. Gerald-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e726-e779.

14. McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286:1599-1606.

15. Cranley JJ. Ischemic rest pain. Arch Surg. 1969;98:187-188.

16. Khan NA, Rahim SA, Anand SS, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295:536-546.

17. Wennberg PW. Approach to the patient with peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2013;128:2241-2250.

18. Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II). Eur J Vas Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:S1-S75.

19. Armstrong EJ, Wu J, Singh GD, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with decreased mortality and improved amputation-free survival among patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1565-1571.

20. Lane R, Harwood A, Watson L, et al. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(12):CD000990.

21. Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, et al; CLEVER Study Investigators. Supervised exercise versus primary stenting for claudication resulting from aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: six-month outcomes from the claudication: exercise versus endoluminal revascularization (CLEVER) study. Circulation. 2012;125:130-139.

22. Fakhry F, Fokkenrood HJP, Pronk S, et al. Endovascular revascularization versus conservative management for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(3):CD010512.

23. Hageman D, Fokkenrood HJ, Gommans LN, et al. Supervised exercise therapy versus home-based exercise therapy versus walking advice for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(4):CD005263.

24. McDermott MM, Spring B, Berger JS, et al. Effect of a home-based exercise intervention of wearable technology and telephone coaching on walking performance in peripheral artery disease: the HONOR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1665-1676.

25. Ruiz-Canela M, Estruch R, Corella D, et al. Association of Mediterranean diet with peripheral artery disease: the PREDIMED randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:415-417.

26. Zahradka P, Wright B, Weighell W, et al. Daily non-soy legume consumption reverses vascular impairment due to peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2013;230:310-314.

27. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. Randomized trial of the effects of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin on peripheral vascular and other major vascular outcomes in 20536 people with peripheral arterial disease and other high-risk conditions. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:645-655.

28. Kumbhani DJ, Steg G, Cannon CP, et al. Statin therapy and long-term adverse limb outcomes in patients with peripheral artery disease: insights from the REACH registry. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2864-2872.

29. Wong PF, Chong LY, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Antiplatelet agents for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11):CD001272.

30. Critical Leg Ischaemia Prevention Study (CLIPS) Group, Catalano M, Born G, Peto R. Prevention of serious vascular events by aspirin amongst patients with peripheral arterial disease: randomized, double-blind trial. J Intern Med. 2007;261:276-284.

31. Morley RL, Sharma A, Horsch AD, et al. Peripheral artery disease. BMJ. 2018;360:j5842.

32. Bedenis R, Stewart M, Cleanthis M, et al. Cilostazol for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD003748.

33. Salhiyyah K, Forster R, Senanayake E, et al. Pentoxifylline for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD005262.

34. Stewart M, Morling JR, Maxwell H. Padma 28 for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(3):CD007371.

35. Kleijnen J, Mackerras D. Vitamin E for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(1):CD000987.

36. Nicolai SPA, Kruidenior LM, Bendermacher BLW, et al. Ginkgo biloba for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD006888.

37. Campbell A, Price J, Hiatt WR. Omega-3 fatty acids for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD003833.

38. American Surgical Association, New York Surgical Society, Philadelphia Academy of Surgery, Southern Surgical Association (US), Central Surgical Association. Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity: the STILE trial. Ann Surg. 1994;220:251-268.

39. Ouriel K, Veith FJ, Sasahara AA.

40. Bradbury AW, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FGR, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL): multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1925-1934.

41. Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:381-386.

1. Eraso LH, Fukaya E, Mohler ER 3rd, et al. Peripheral arterial disease, prevalence and cumulative risk factor profile analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:704-711.

2. Pasternak RC, Criqui MH, Benjamin EJ, et al; American Heart Association. Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference: Writing Group I: epidemiology. Circulation. 2004;109:2605-2612.

3. Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317-1324.

4. Olin JW, Sealove BA. Peripheral artery disease: current insight into the disease and its diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:678-692.

5. Andras A, Ferkert B. Screening for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD010835.

6. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Redmond N, et al. Screening for peripheral artery disease using ankle-brachial index: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:184-196.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease risk assessment with ankle-brachial index: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;230:177-183.

8. American Heart Association Writing Group 2. Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Symposium II: screening for atherosclerotic vascular diseases: should nationwide programs be instituted? Circulation. 2008;118:2830-2836.

9. Berger JS, Hochman J, Lobach I, et al. Modifiable risk factor burden and the prevalence of peripheral artery disease in different vascular territories. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:673-681.

10. Joosten MM, Pai JK, Bertoia ML, et al. Associations between conventional cardiovascular risk factors and risk of peripheral artery disease in men. JAMA. 2012;308:1660-1667.

11. Carmelli D, Fabsitz RR, Swan GE, et al. Contribution of genetic and environmental influences to ankle-brachial blood pressure index in the NHLBI Twin Study. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:452-458.

12. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, et al. Risk factors for progression of peripheral arterial disease in large and small vessels. Circulation. 2006;113:2623-2629.

13. Gerald-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e726-e779.

14. McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286:1599-1606.

15. Cranley JJ. Ischemic rest pain. Arch Surg. 1969;98:187-188.

16. Khan NA, Rahim SA, Anand SS, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295:536-546.

17. Wennberg PW. Approach to the patient with peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2013;128:2241-2250.

18. Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II). Eur J Vas Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:S1-S75.

19. Armstrong EJ, Wu J, Singh GD, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with decreased mortality and improved amputation-free survival among patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1565-1571.

20. Lane R, Harwood A, Watson L, et al. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(12):CD000990.

21. Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, et al; CLEVER Study Investigators. Supervised exercise versus primary stenting for claudication resulting from aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: six-month outcomes from the claudication: exercise versus endoluminal revascularization (CLEVER) study. Circulation. 2012;125:130-139.

22. Fakhry F, Fokkenrood HJP, Pronk S, et al. Endovascular revascularization versus conservative management for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(3):CD010512.

23. Hageman D, Fokkenrood HJ, Gommans LN, et al. Supervised exercise therapy versus home-based exercise therapy versus walking advice for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(4):CD005263.

24. McDermott MM, Spring B, Berger JS, et al. Effect of a home-based exercise intervention of wearable technology and telephone coaching on walking performance in peripheral artery disease: the HONOR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1665-1676.

25. Ruiz-Canela M, Estruch R, Corella D, et al. Association of Mediterranean diet with peripheral artery disease: the PREDIMED randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:415-417.

26. Zahradka P, Wright B, Weighell W, et al. Daily non-soy legume consumption reverses vascular impairment due to peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2013;230:310-314.

27. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. Randomized trial of the effects of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin on peripheral vascular and other major vascular outcomes in 20536 people with peripheral arterial disease and other high-risk conditions. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:645-655.

28. Kumbhani DJ, Steg G, Cannon CP, et al. Statin therapy and long-term adverse limb outcomes in patients with peripheral artery disease: insights from the REACH registry. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2864-2872.

29. Wong PF, Chong LY, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Antiplatelet agents for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11):CD001272.

30. Critical Leg Ischaemia Prevention Study (CLIPS) Group, Catalano M, Born G, Peto R. Prevention of serious vascular events by aspirin amongst patients with peripheral arterial disease: randomized, double-blind trial. J Intern Med. 2007;261:276-284.

31. Morley RL, Sharma A, Horsch AD, et al. Peripheral artery disease. BMJ. 2018;360:j5842.

32. Bedenis R, Stewart M, Cleanthis M, et al. Cilostazol for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD003748.

33. Salhiyyah K, Forster R, Senanayake E, et al. Pentoxifylline for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD005262.

34. Stewart M, Morling JR, Maxwell H. Padma 28 for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(3):CD007371.

35. Kleijnen J, Mackerras D. Vitamin E for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(1):CD000987.

36. Nicolai SPA, Kruidenior LM, Bendermacher BLW, et al. Ginkgo biloba for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD006888.

37. Campbell A, Price J, Hiatt WR. Omega-3 fatty acids for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD003833.

38. American Surgical Association, New York Surgical Society, Philadelphia Academy of Surgery, Southern Surgical Association (US), Central Surgical Association. Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity: the STILE trial. Ann Surg. 1994;220:251-268.

39. Ouriel K, Veith FJ, Sasahara AA.

40. Bradbury AW, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FGR, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL): multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1925-1934.

41. Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:381-386.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

❯ Use the ankle-brachial index for diagnosis in patients with history/physical exam findings suggestive of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). A

❯ Strongly encourage smoking cessation in patients with PAD as doing so reduces 5-year mortality and amputation rates. B

❯ Use structured exercise programs for patients with intermittent claudication prior to consideration of revascularization; doing so offers similar benefit and lower risks. A

❯ Recommend revascularization for patients who have limb ischemia or lifestyle-limiting claudication despite medical and exercise therapy. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Primary prevention of VTE spans a spectrum

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common and dangerous disease, affecting 0.1%-0.2% of the population annually—a rate that might be underreported.1 VTE is a collective term for venous blood clots, including (1) deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of peripheral veins and (2) pulmonary embolism, which occurs after a clot travels through the heart and becomes lodged in the pulmonary vasculature. Two-thirds of VTE cases present clinically as DVT2; most mortality from VTE disease is caused by the 20% of cases of pulmonary embolism that present as sudden death.1

VTE is comparable to myocardial infarction (MI) in incidence and severity. In 2008, 208 of every 100,000 people had an MI, with a 30-day mortality of 16/100,0003; VTE disease has an annual incidence of 161 of every 100,000 people and a 28-day mortality of 18/100,000.4 Although the incidence and severity of MI are steadily decreasing, the rate of VTE appears constant.3,5 The high mortality of VTE suggests that primary prevention, which we discuss in this article, is valuable (see “Key points: Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism”).

SIDEBAR

Key points: Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism

- Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE), a disease with mortality similar to myocardial infarction, should be an important consideration in at-risk patients.

- Although statins reduce the risk of VTE, their use is justified only if they are also required for prevention of cardiovascular disease.

- The risk of travel-related VTE can be reduced by wearing compression stockings.

- The choice of particular methods of contraception and of hormone replacement therapy can reduce VTE risk.

- Because of the risk of bleeding, using anticoagulants for primary prevention of VTE is justified only in certain circumstances.

- Pregnancy is the only condition in which there is a guideline indication for thrombophilia testing, because test results in this setting can change recommendations for preventing VTE.

- Using a risk-stratification model is key to determining risk in both medically and surgically hospitalized patients. Trauma and major orthopedic surgery always place the patient at high risk of VTE.

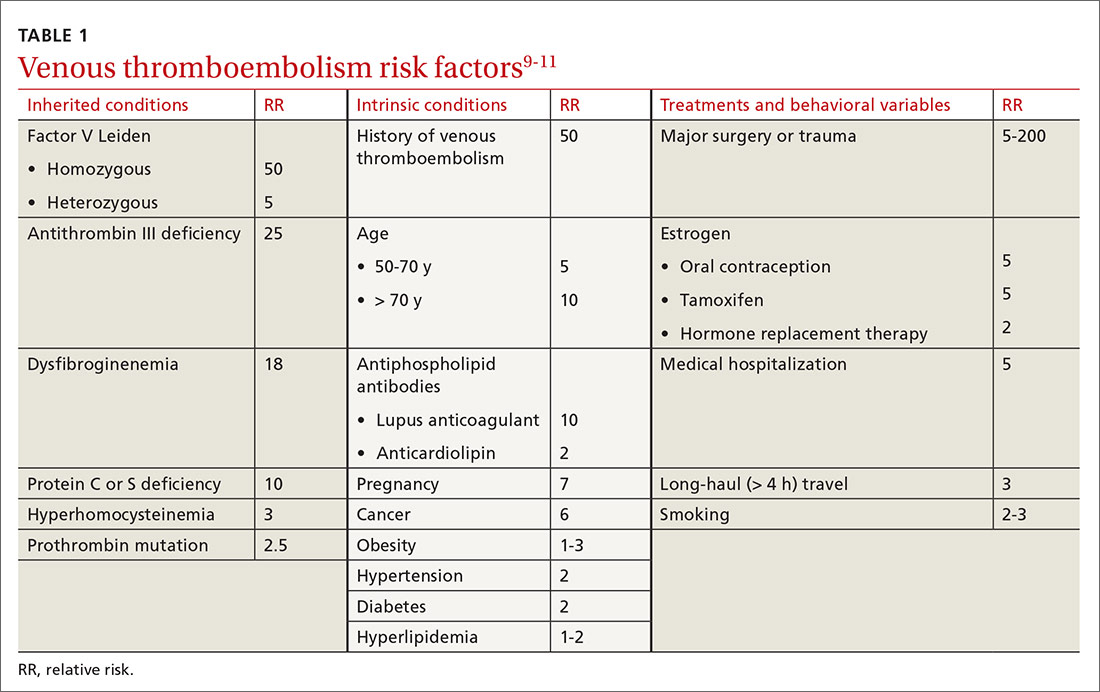

Risk factors

Virchow’s triad of venous stasis, vascular injury, and hypercoagulability describes predisposing factors for VTE.6 Although venous valves promote blood flow, they produce isolated low-flow areas adjacent to valves that become concentrated and locally hypoxic, increasing the risk of clotting.7 The great majority of DVTs (≥ 96%) occur in the lower extremity,8 starting in the calf; there, 75% of cases resolve spontaneously before they extend into the deep veins of the proximal leg.7 One-half of DVTs that do move into the proximal leg eventually embolize.7

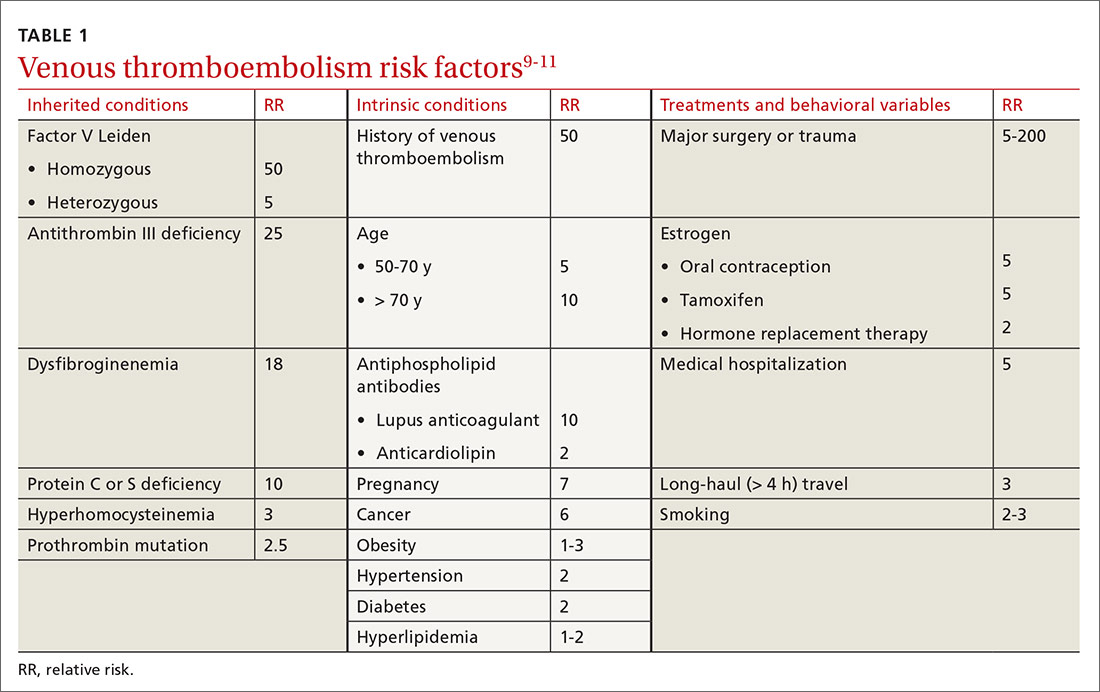

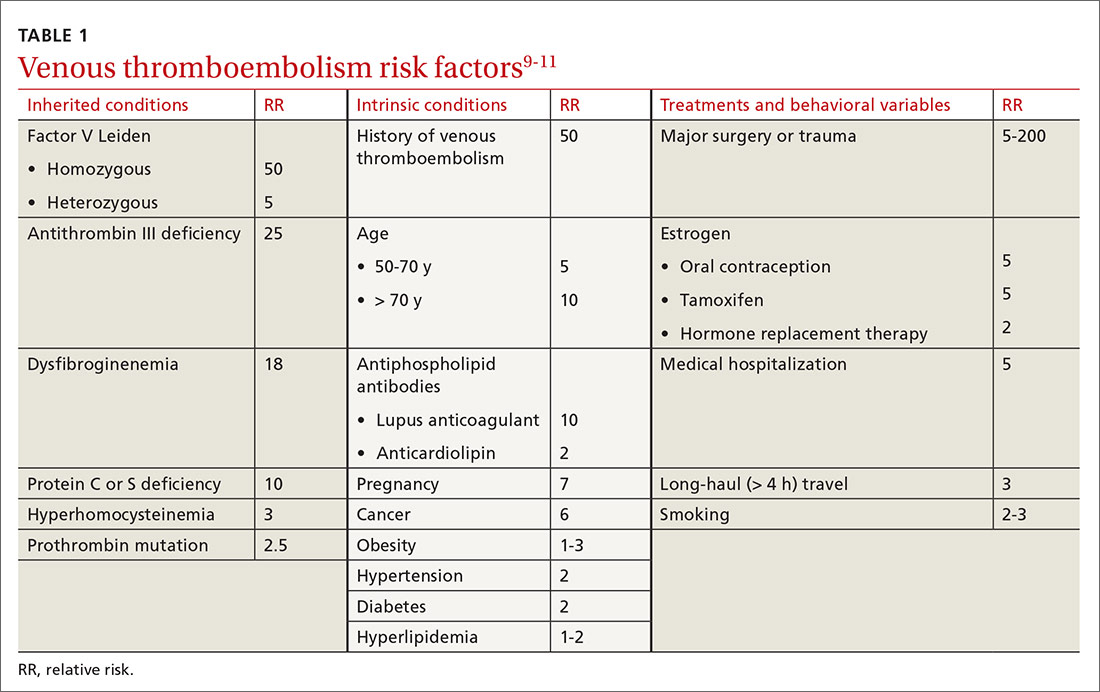

Major risk factors for VTE comprise inherited conditions, medical history, medical therapeutics, and behaviors (TABLE 1).9-11 Unlike the preventive management of coronary artery disease (CAD), there is no simple, generalized prevention algorithm to address VTE risk factors.

Risk factors for VTE and CAD overlap. Risk factors for atherosclerosis—obesity, diabetes, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia—also increase the risk of VTE (TABLE 1).9-11 The association between risk factors for VTE and atherosclerosis is demonstrated by a doubling of the risk of MI and stroke in the year following VTE.11 Lifestyle changes are expected to reduce the risk of VTE, as they do for acute CAD, but studies are lacking to confirm this connection. There is no prospective evidence showing that weight loss or control of diabetes or hypertension reduces the risk of VTE.12 Smoking cessation does appear to reduce risk: Former smokers have the same VTE risk as never-smokers.13

Thrombophilia testing: Not generally useful

Inherited and acquired thrombophilic conditions define a group of disorders in which the risk of VTE is increased. Although thrombophilia testing was once considered for primary and secondary prevention of VTE, such testing is rarely used now because proof of benefit is lacking: A large case–control study showed that thrombophilia testing did not predict recurrence after a first VTE.14 Guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) do not address thrombophilia, and the American Society of Hematology recommends against thrombophilia testing after a provoked VTE.15,16

Primary prophylaxis of patients with a family history of VTE and inherited thrombophilia is controversial. Patients with both a family history of VTE and demonstrated thrombophilia do have double the average incidence of VTE, but this increased risk does not offset the significant bleeding risk associated with anticoagulation.17 Recommendations for thrombophilia testing are limited to certain situations in pregnancy, discussed in a bit.16,18,19

Continue to: Primary prevention of VTE in the clinic

Primary prevention of VTE in the clinic

There is no single, overarching preventive strategy for VTE in an ambulatory patient (although statins, discussed in a moment, offer some benefit, broadly). There are, however, distinct behavioral characteristics and medical circumstances for which opportunities exist to reduce VTE risk—for example, when a person engages in long-distance travel, receives hormonal therapy, is pregnant, or has cancer. In each scenario, recognizing and mitigating risk are important.

Statins offer a (slight) benefit

There is evidence that statins reduce the risk of VTE—slightly20-23:

- A large randomized, controlled trial showed that rosuvastatin, 20 mg/d, reduced the rate of VTE, compared to placebo; however, the 2-year number needed to treat (NNT) was 349.20 The VTE benefit is minimal, however, compared to primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with statins (5-year NNT = 56).21 The sole significant adverse event associated with statins was new-onset type 2 diabetes (5-year number needed to harm = 235).21

- A subsequent meta-analysis confirmed a small reduction in VTE risk with statins.22 In its 2012 guidelines, ACCP declined to issue a recommendation on the use of statins for VTE prevention.23 When considering statins for primary cardiovascular disease prevention, take the additional VTE prevention into account.

Simple strategies can help prevent travel-related VTE

Travel is a common inciting factor for VTE. A systematic review showed that VTE risk triples after travel of ≥ 4 hours, increasing by 20% with each additional 2 hours.24 Most VTE occurs in travelers who have other VTE risk factors.25 Based on case–control studies,23 guidelines recommend these preventive measures:

- frequent calf exercises

- sitting in an aisle seat during air travel

- keeping hydrated.

A Cochrane review showed that graded compression stockings reduce asymptomatic DVT in travelers by a factor of 10, in high- and low-risk patients.26

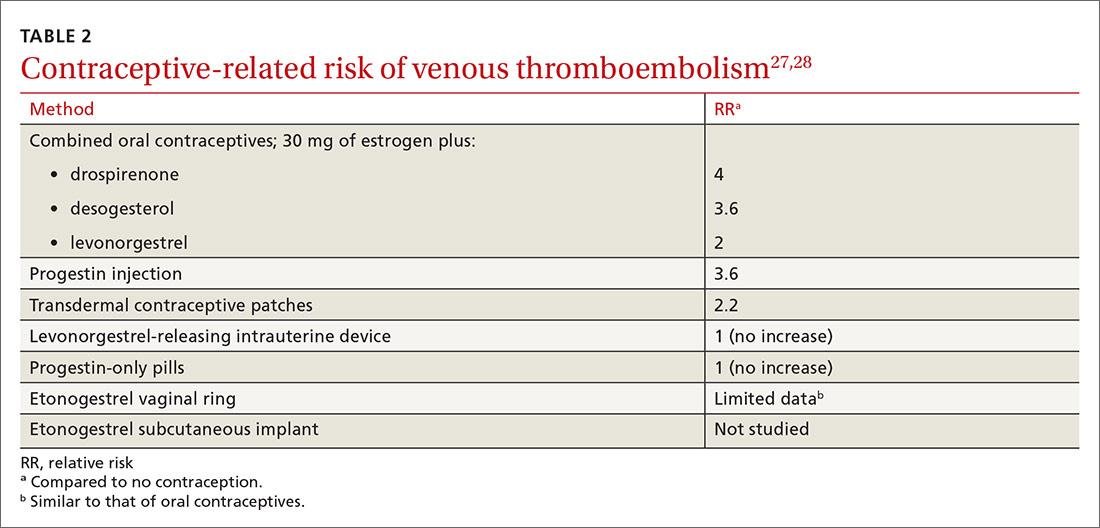

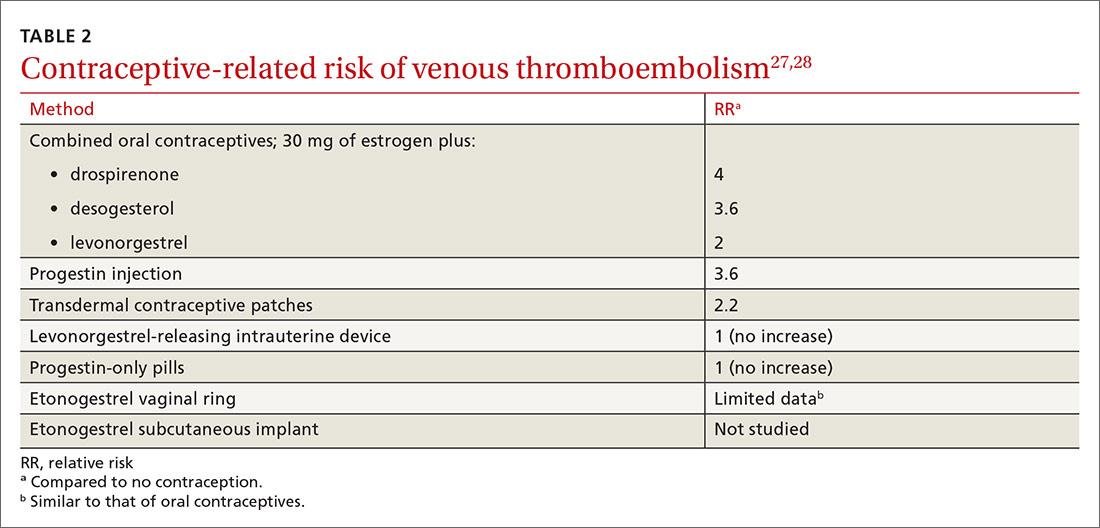

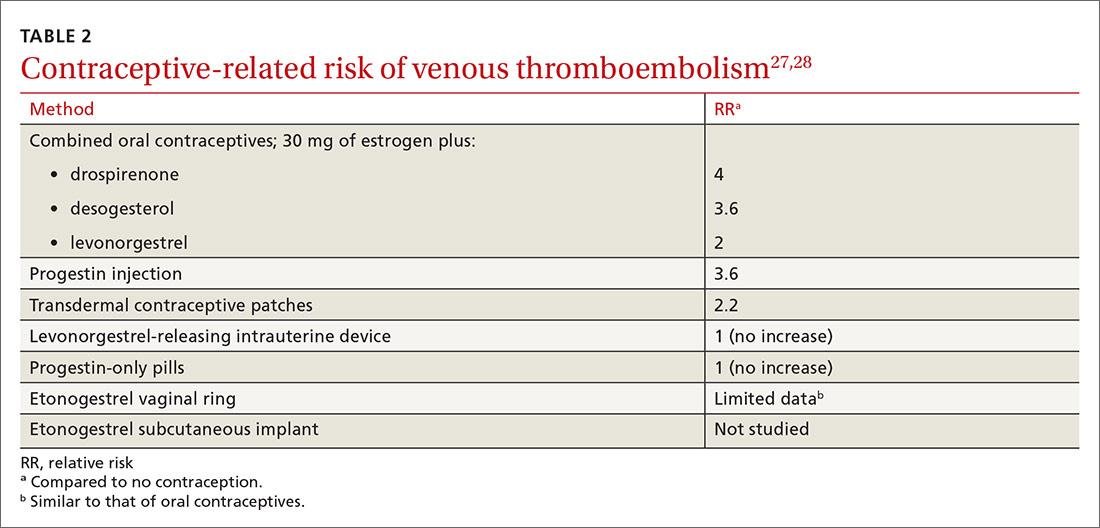

VTE risk varies with type of hormonal contraception

Most contraceptives increase VTE risk (TABLE 227,28). Risk with combined oral contraceptives varies with the amount of estrogen and progesterone. To reduce VTE risk with oral contraceptives, patients can use an agent that contains a lower dose of estrogen or one in which levonorgestrel replaces other progesterones.27

Continue to: Studies suggest that the levonorgestrel-releasing...

Studies suggest that the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and progestin-only pills are not associated with an increase in VTE risk.27 Although the quality of evidence varies, most nonoral hormonal contraceptives have been determined to carry a risk of VTE that is similar to that of combined oral contraceptives.28

In hormone replacement, avoid pills to lower risk

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for postmenopausal women increases VTE risk when administered in oral form, with combined estrogen and progestin HRT doubling the risk and estrogen-only formulations having a lower risk.29 VTE risk is highest in the first 6 months of HRT, declining to that of a non-HRT user within 5 years.29 Neither transdermal HRT nor estrogen creams increase the risk of VTE, according to a systematic review.30 The estradiol-containing vaginal ring also does not confer increased risk.29

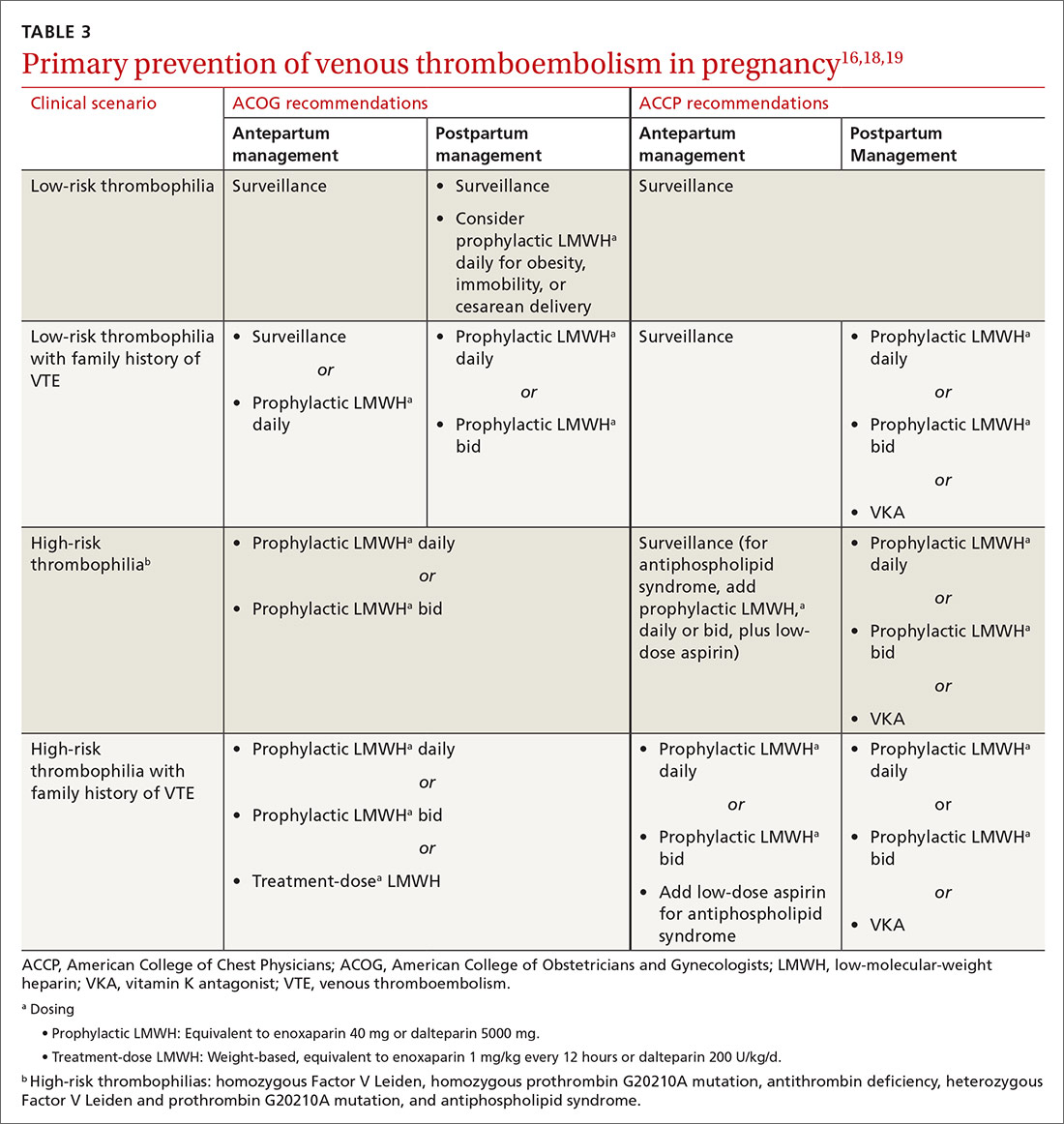

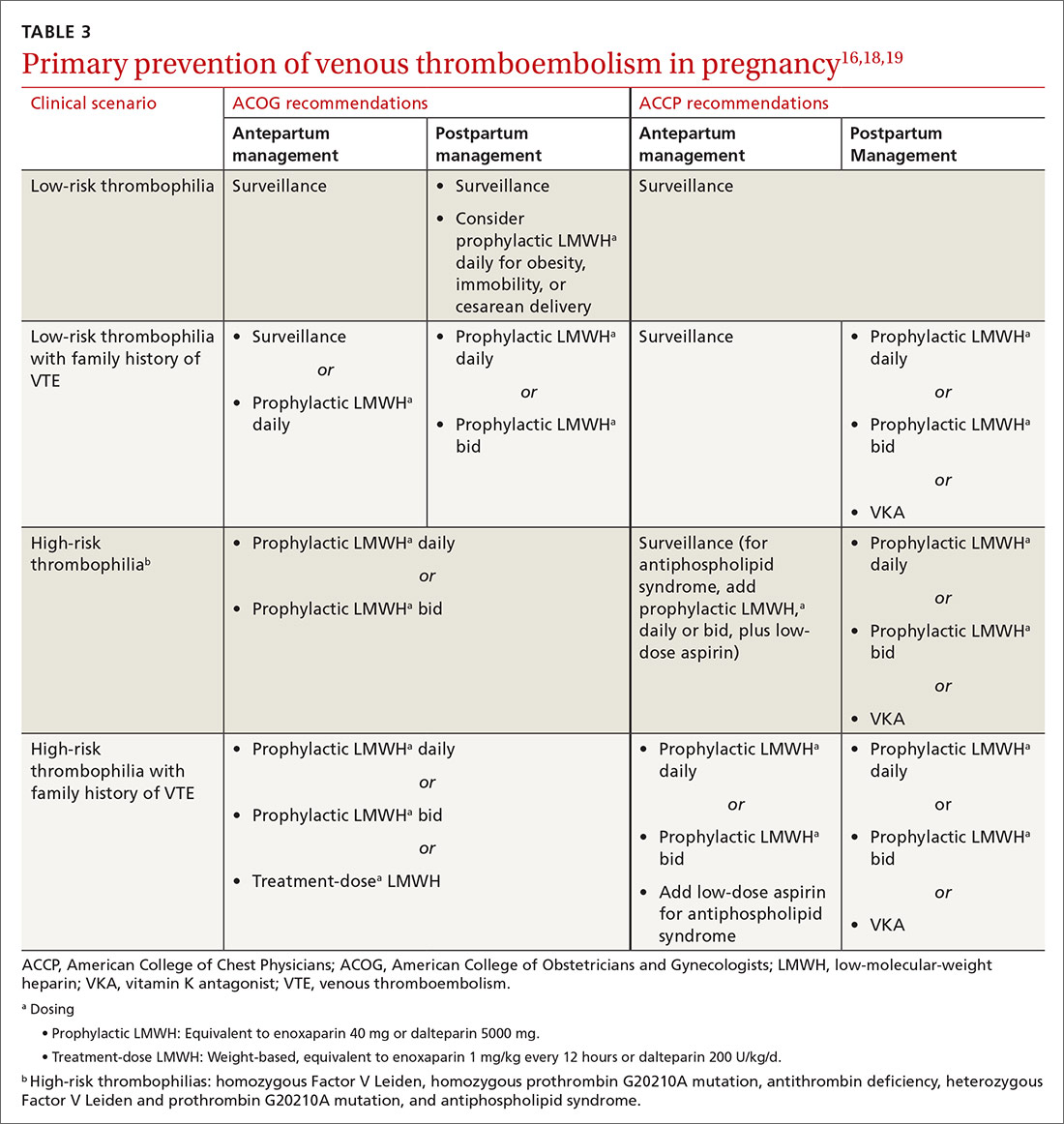

Pregnancy, thrombophilia, and VTE prevention

VTE affects as many as 0.2% of pregnancies but causes 9% of pregnancy-related deaths.18 The severity of VTE in pregnancy led the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to recommend primary VTE prophylaxis in patients with certain thrombophilias.18 Thrombophilia testing is recommended in patients with proven high-risk thrombophilia in a first-degree relative.18 ACOG recognizes 5 thrombophilias considered to carry a high risk of VTE in pregnancy18:

- homozygous Factor V Leiden

- homozygous prothrombin G20210A mutation

- antithrombin deficiency

- heterozygous Factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutation

- antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

ACOG recommends limiting thrombophilia testing to (1) any specific thrombophilia carried by a relative and (2) possibly, the antiphospholipid antibodies anticardiolipin and lupus anticoagulant.18,19 Antiphospholipid testing is recommended when there is a history of stillbirth, 3 early pregnancy losses, or delivery earlier than 34 weeks secondary to preeclampsia.19

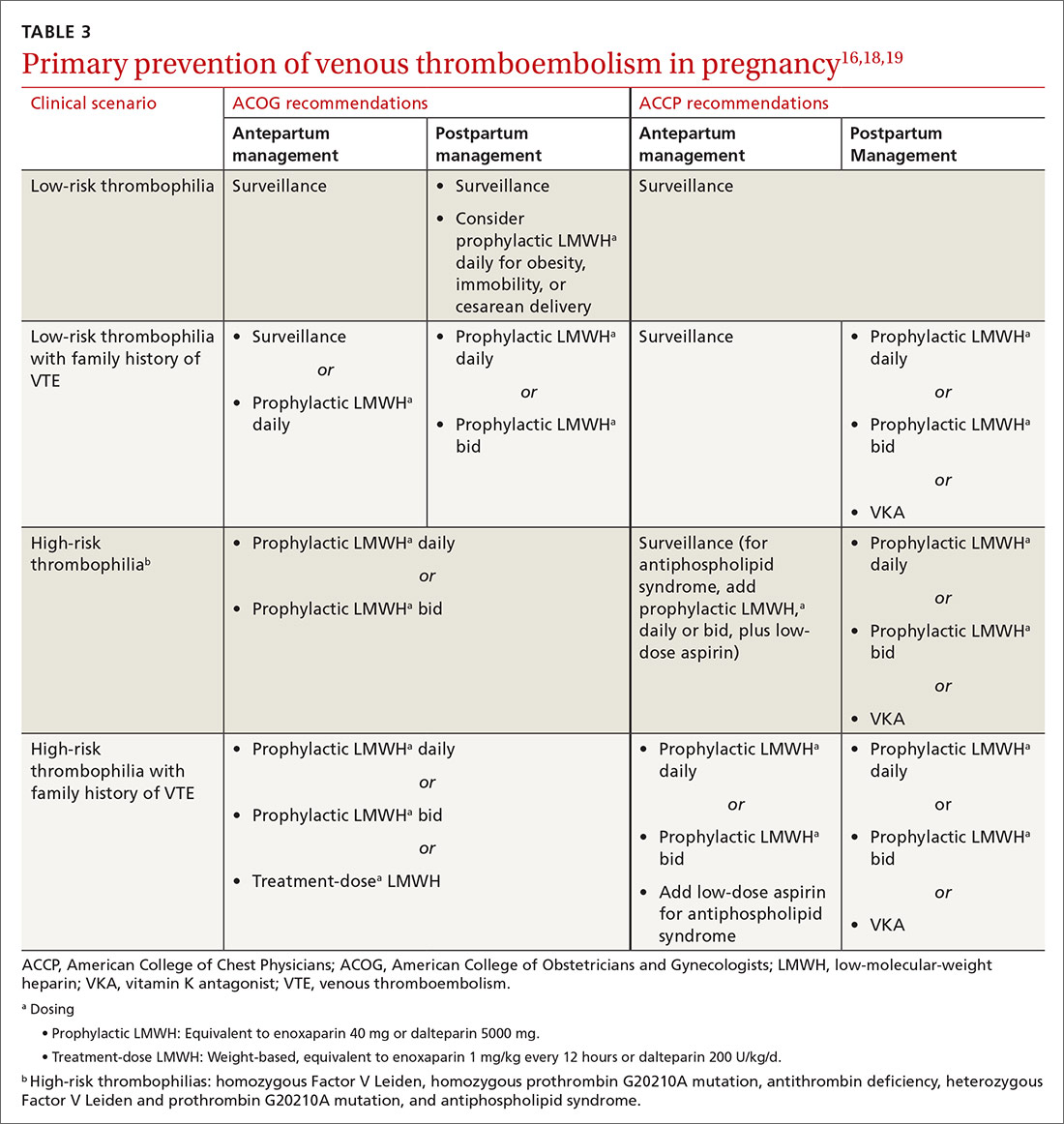

Primary VTE prophylaxis is recommended for pregnant patients with a high-risk thrombophilia; low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is safe and its effects are predictable.18 Because postpartum risk of VTE is higher than antepartum risk, postpartum prophylaxis is also recommended with lower-risk thrombophilias18; a vitamin K antagonist or LMWH can be used.18 ACCP and ACOG recommendations for VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy differ slightly (TABLE 316,18,19).

Continue to: Cancer increases risks of VTE and bleeding

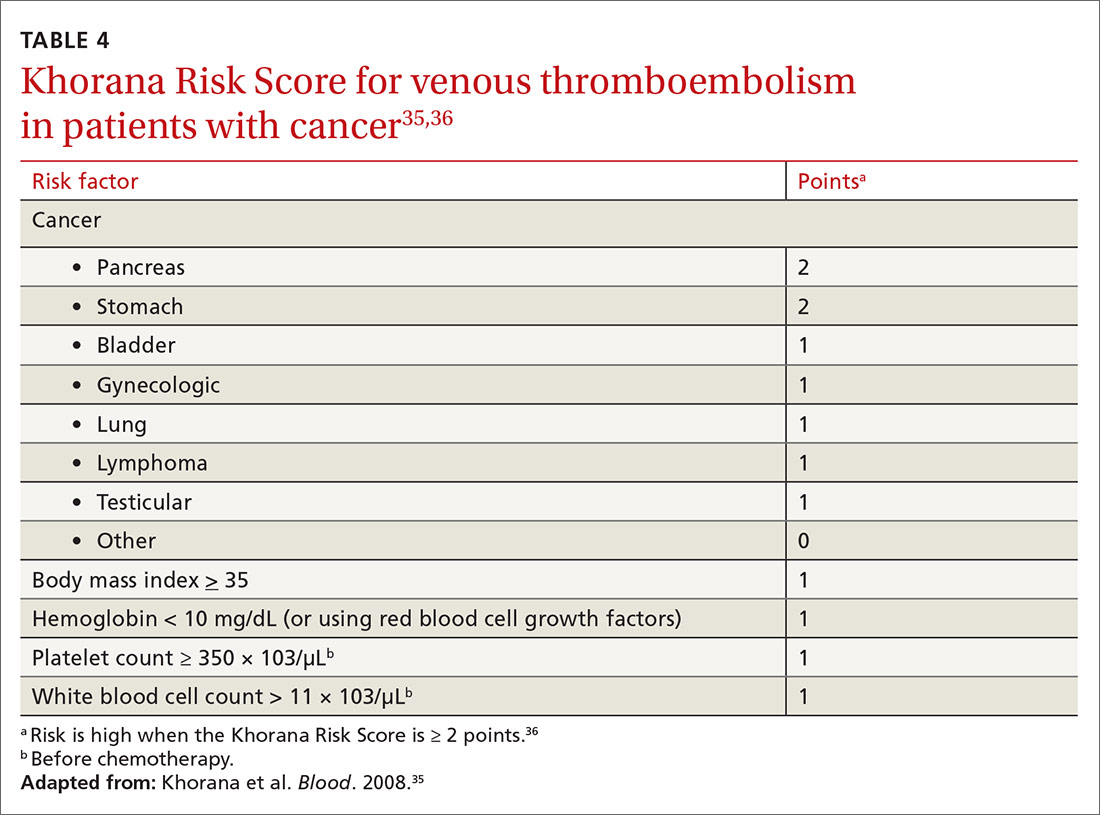

Cancer increases risks of VTE and bleeding

Cancer increases VTE risk > 6-fold31; metastases, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy further increase risk. Cancer also greatly increases the risk of bleeding: Cancer patients with VTE have an annual major bleeding rate ≥ 20%.32 Guidelines do not recommend primary VTE prophylaxis for cancer, although American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines discuss consideration of prophylaxis for select, high-risk patients,33,34 including those with multiple myeloma, metastatic gastrointestinal cancer, or metastatic brain cancer.31,34 Recent evidence (discussed in a moment) supports the use of apixaban for primary VTE prevention during chemotherapy for high-risk cancer.

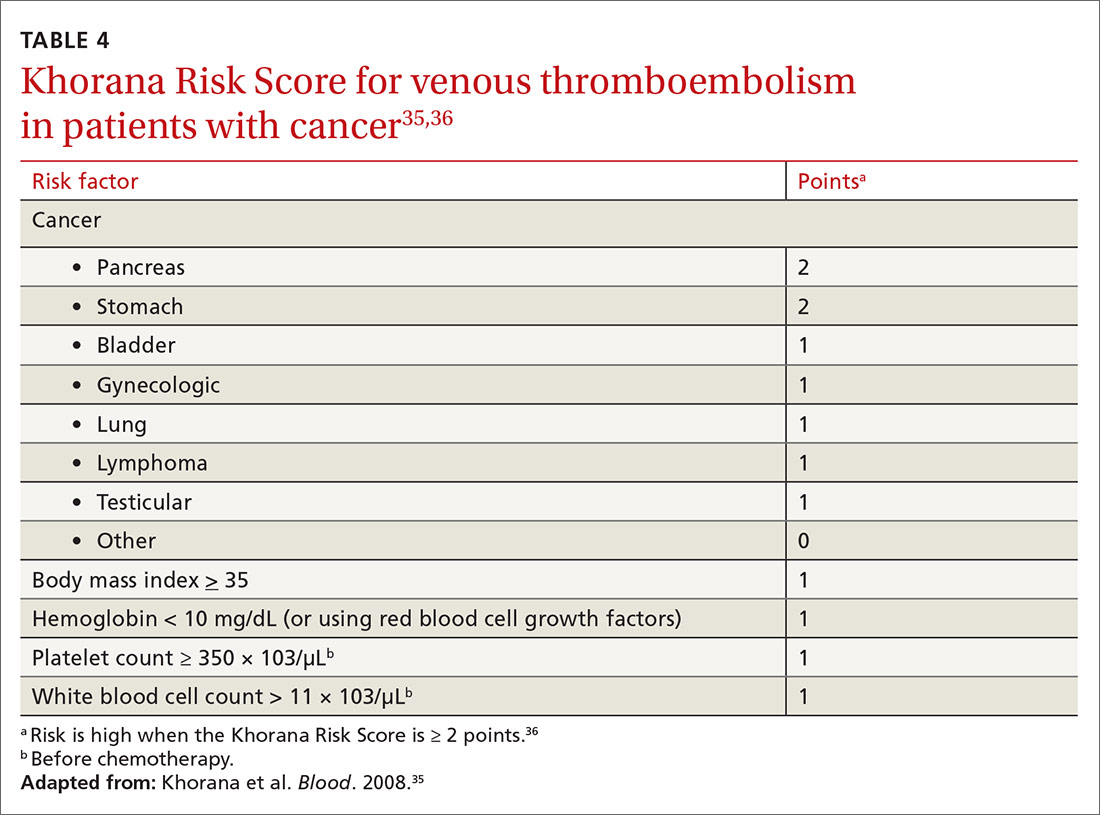

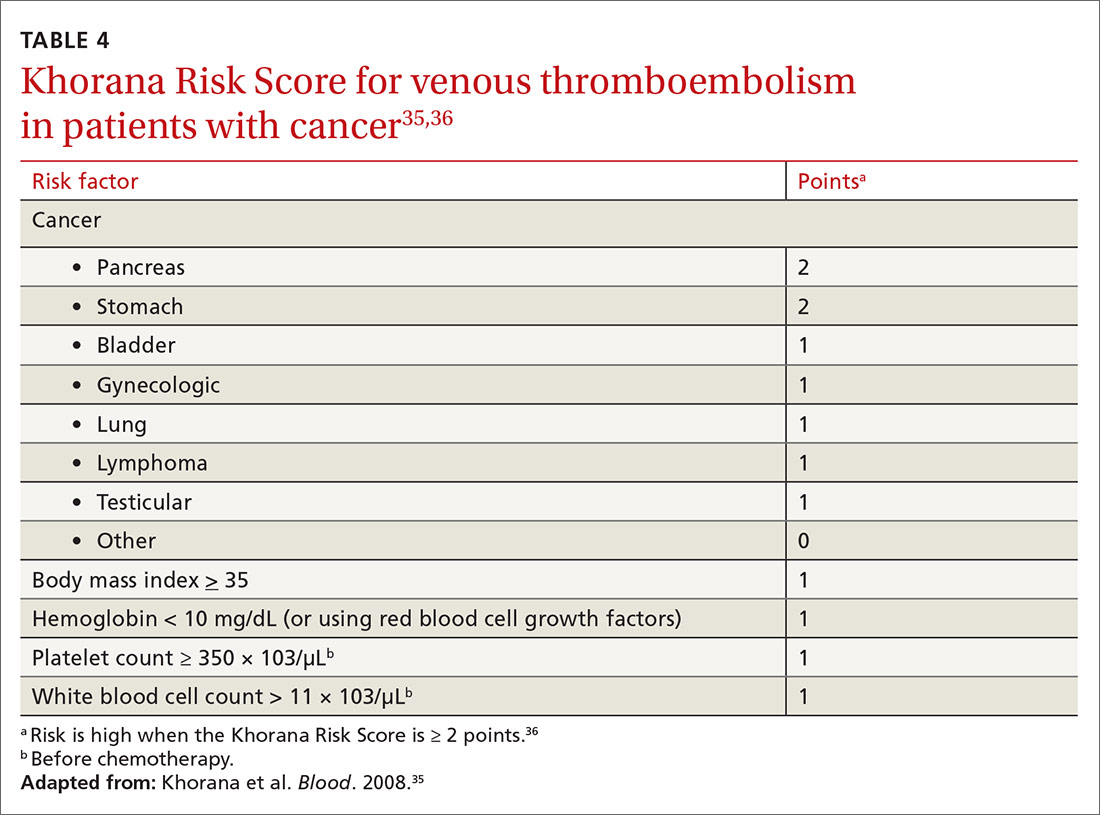

The Khorana Risk Score (TABLE 435,36) for VTE was developed and validated for use in patients with solid cancer35: A score of 2 conveys nearly a 10% risk of VTE over 6 months.36 A recent study of 550 cancer patients with a Khorana score of ≥ 2—the first evidence of risk-guided primary VTE prevention in cancer—showed that primary prophylaxis with 2.5 mg of apixaban, bid, reduced the risk of VTE (NNT = 17); however, the number needed to harm (for major bleeding) was 59.37 Mortality was not changed with apixaban treatment

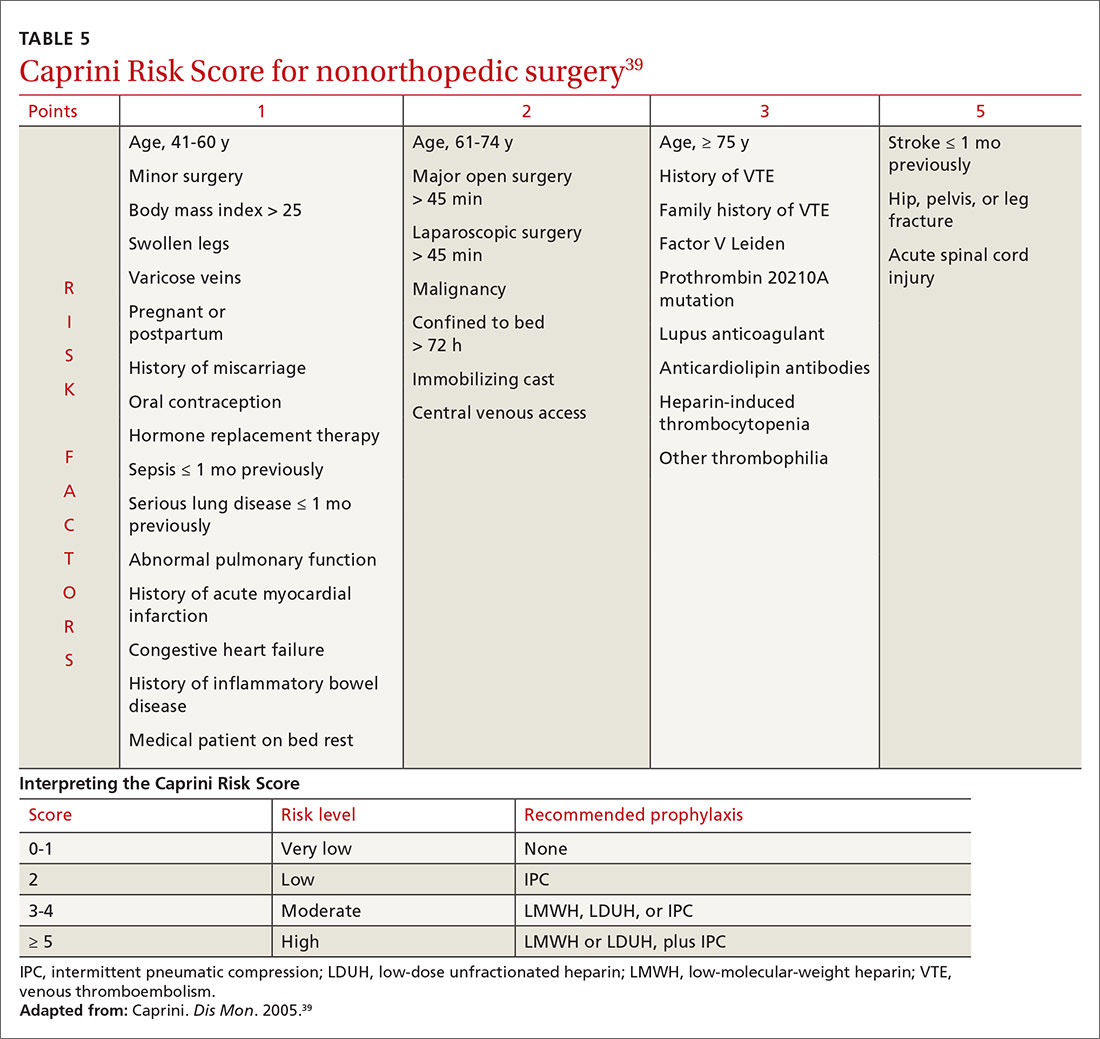

Primary VTE prevention in med-surg hospitalizations

The risk of VTE increases significantly during hospitalization, although not enough to justify universal prophylaxis. Recommended prevention strategies for different classes of hospitalized patients are summarized below.

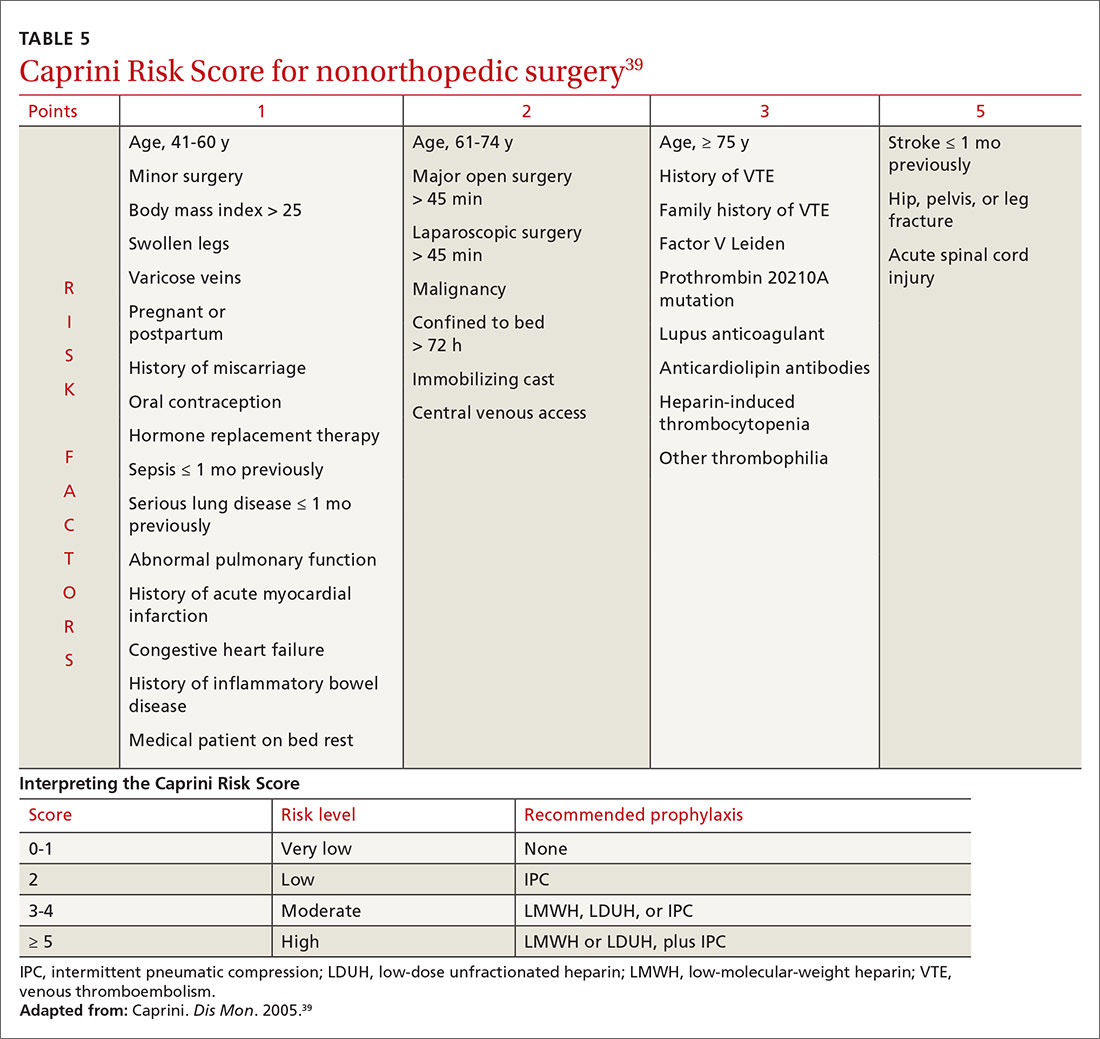

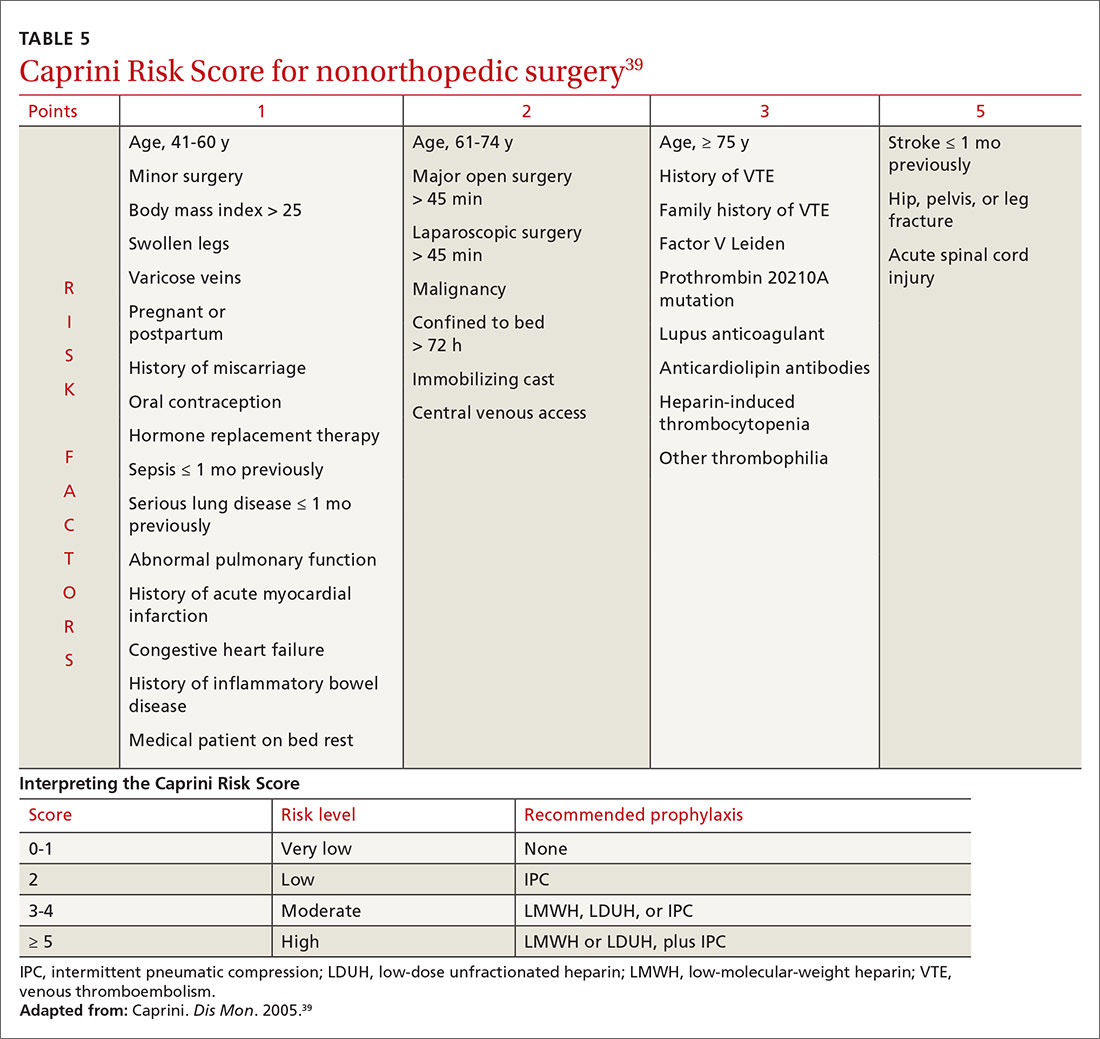

In medically hospitalized patients, risk is stratified with a risk-assessment model. Medically hospitalized patients have, on average, a VTE risk of 1.2%23; 12 risk-assessment models designed to stratify risk were recently compared.38 Two models, the Caprini Score (TABLE 5)39 and the IMPROVE VTE Risk Calculator,40 were best able to identify low-risk patients (negative predictive value, > 99%).38 American Society of Hematology guidelines recommend IMPROVE VTE or the Padua Prediction Score for risk stratification.41 While the Caprini score only designates 11% of eventual VTE cases as low risk, both the IMPROVE VTE and Padua scores miss more than 35% of eventual VTE.38

Because LMWH prophylaxis has been shown to reduce VTE by 40% without increasing the risk of major bleeding, using Caprini should prevent 2 VTEs for every 1000 patients, without an increase in major bleeding and with 13 additional minor bleeding events.42