User login

Vacuum extraction: Tips for achieving an optimal outcome

CASE: Is vacuum extraction right for this delivery?

A 41-year-old woman (G2P2002) is at term in her third pregnancy, and the fetus exhibits prolonged deceleration that does not resolve while the mother pushes from a +3 station. The fetus, estimated to weigh 8 lb, is in the occiput anterior (OA) position. The mother is willing to consider vaginal extraction, and you must weigh the factors that may influence successful delivery.

Vacuum extraction (VE) is an effective method to facilitate delivery. From 2007 to 2013, VE was used to facilitate about 3% of vaginal deliveries in the United States.1 By contrast, cesarean delivery rates over the same period averaged about 30%.2

Controversy exists on the pros and cons of operative vaginal deliveries versus cesarean delivery, as well as on the instruments and operational approaches used. While opinion tends to be resolute and influential, evidence remains inconclusive.

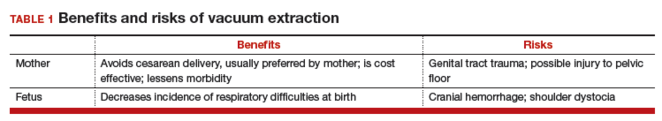

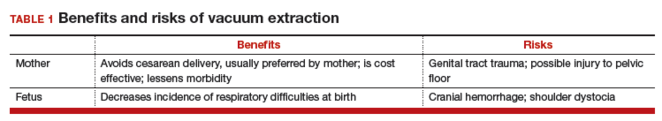

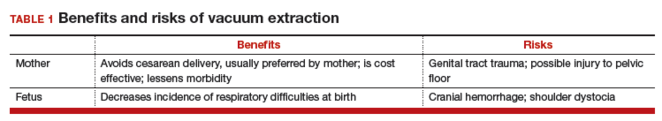

Multiple factors influence a decision on whether to choose VE. The clinician’s own bias regarding delivery routes and comfort level with performing VE are important. The patient, too, may have preconceived opinions about VE. Knowing the indications for VE and its benefits and risks (TABLE 1) can help the patient make an informed choice and the counseling on which will be needed in obtaining the patient’s informed consent. The expectations and desires of the patient in concert with the experience and skill of the clinician will serve to achieve the optimal decision.

Indications for VE

Maternal indications for the use of VE include prolongation or arrest of the second stage of labor. Another indication is the need to shorten the second stage due to a maternal cardiac or cardiovascular disorder or due to maternal exhaustion.

Fetal indications include nonreassuring fetal status or a need to correct for minor degrees of malposition (asynclitism, deflexion) that historically have been addressed with the use of obstetric forceps. VE delivery in these circumstances requires a very experienced and skilled operator.

Further selection criteria

Birthweight influences the consideration of VE. Low birthweight or prematurity are contraindications to the use of VE due to concerns about fetal/neonatal bleeding. Large fetuses will have issues with cephalopelvic disproportion, thus increasing the risk for 2 disorders: shoulder dystocia and fetal cranial bleeding.

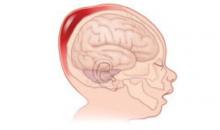

Cranial bleeding, both intracranial and extracranial, can result in serious neonatal morbidity and mortality. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or with the use of VE. In using VE, force is transmitted to the fetal scalp. The scalp then has the tendency to pull on its contents and attachments—skull bones, brain, fluids, etc. The scalp attachments include vessels at right angles to the scalp, which may be traumatized or torn by the pulling force. This may lead to subgaleal hemorrhage, a collection of blood in the large potential space below the scalp and above the aponeurosis. Enough force may be generated to deform the intracranial contents and cause intracranial bleeding.

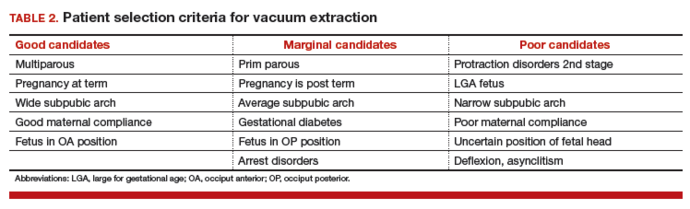

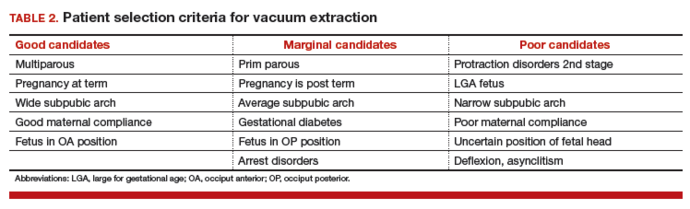

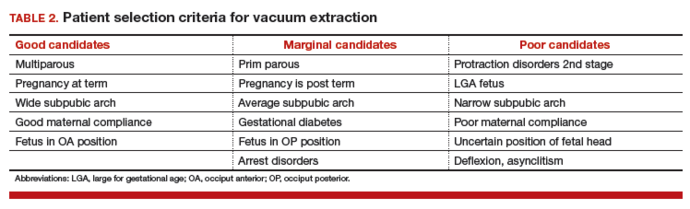

The likelihood of success with VE varies depending on maternal anatomy, the position of the fetal head, gestational age, and the presence or absence of gestational diabetes (TABLE 2).

Delivery by VE: Main considerations

After determining that a candidate is suitable for VE and obtaining informed consent, consider key operative factors:

- choice of extraction cup

- adequate anesthesia

- careful maternal positioning

- maternal bladder emptying

- review of fetal status.

Two major cup types are available: rigid and flexible.

Rigid plastic cup. This design is similar to the metal cup used by Malmström and attaches to the scalp via chignon formation. A variation of the rigid cup is the mityvac “M” that mimics the Malmström design but incorporates a semiflexible handle to facilitate proper cup placement and aid in the direction of pulling force.

Flexible cup. This type of cup flattens against the scalp with vacuum and may result in less minor scalp trauma than the rigid cup.

Greater force can be employed with rigid cup designs than with flexible cups, which can increase the chances of a successful delivery when the fetus is in the occiput posterior (OP) position. Flexible designs tend to cause less damage to the scalp than the rigid cup but are reported to have a higher failure rate.

Cardinal rule of any procedure. Prior to cup placement, remember this rule: abandon the procedure if it proves too difficult. Most deliveries will occur with 3 or 4 pulls.3 Difficulties include:

- failure to gain station with the initial pull

- repetitive cup pop-offs (3 or more)

- an excessive duration of the procedure (>10 minutes).

Less than optimal placement of the vacuum extractor will increase the risk of scalp trauma, particularly in nulliparous women.3

If the procedure is unsuccessful, the resulting options include cesarean delivery and expectant management.

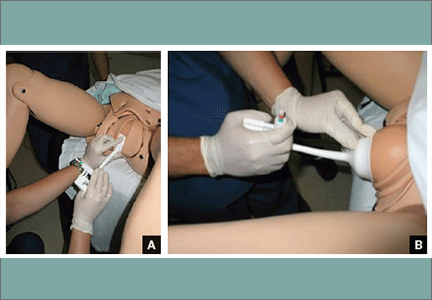

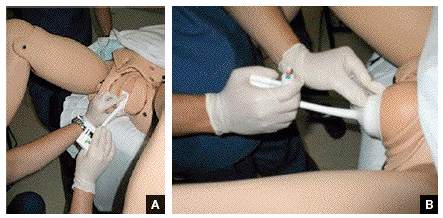

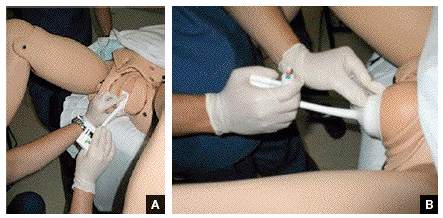

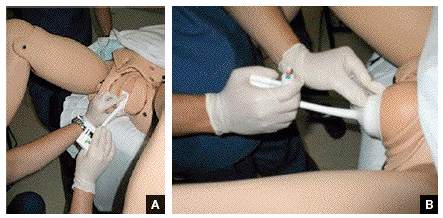

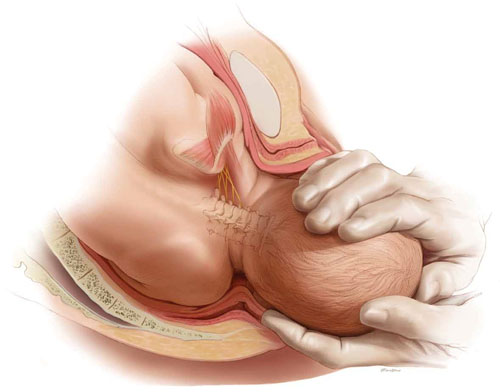

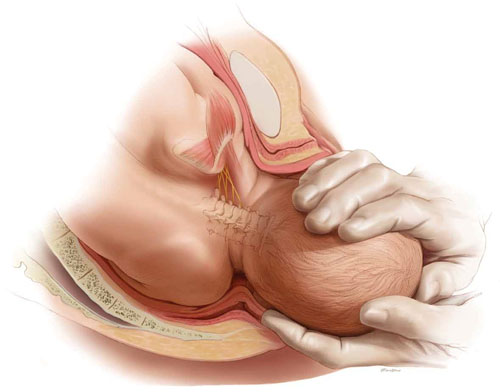

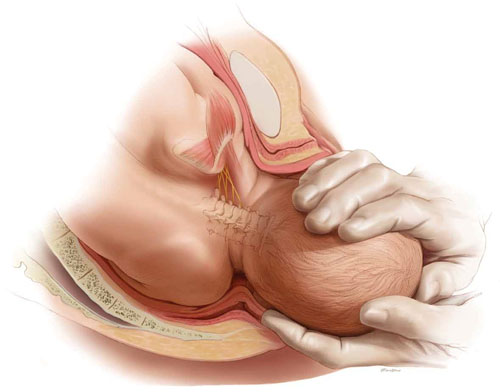

Tip. Use both hands during the pull to more reliably detect a problem with cup attachment, thereby minimizing the possibility of detachment and subsequent scalp trauma (FIGURE).

Key points of technique

Perform a careful and thorough pelvic examination to determine fetal station, position, attitude, and synclitism.

The optimal cup placement is 2- to 3-cm proximal to the posterior fontanel or, alternatively, 5- to 6-cm distal to the anterior fontanel, assuming the fetal head is properly flexed.4 The correct point of flexion will result in the smallest diameter of the fetal head presenting to the birth canal and should minimize the force necessary to achieve delivery.

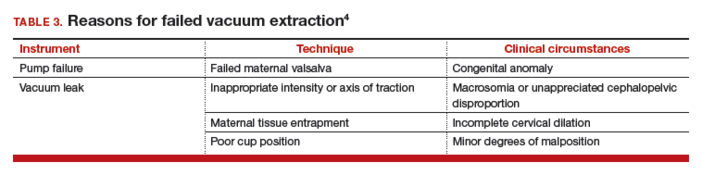

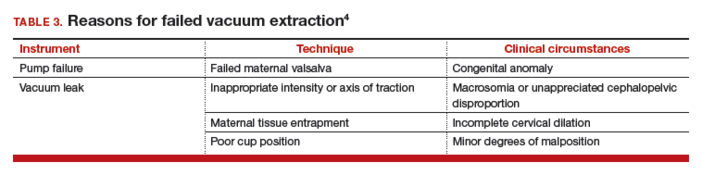

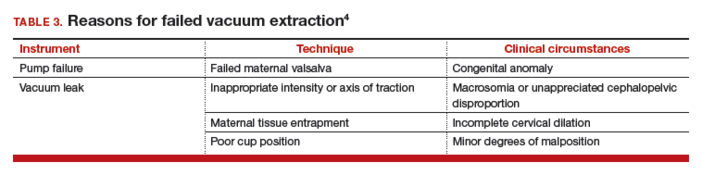

Use minimal vacuum to attach the cup to the fetal head. As the subsequent contraction develops, apply full vacuum with the hand device. Encourage maternal expulsive effort and use traction only in concert with pushing efforts. Three pushes facilitated with pulling may be achieved during a single contraction. Failure to bring about descent with the initial pull indicates potential failure with this approach and, in the absence of technical reasons for the failure, merits serious consideration of abandoning the procedure (TABLE 3).

In the event of failed delivery with VE, it is important to recognize that you should not make a second attempt with another instrument; the chance of success is low and the risk of injury is significantly increased.5

Carefully document the decision for VE and its implementation

The medical record is the most important witness to the event. Clearly record the following items, preferably as close in time to the decision/event as possible:

- the indication for the procedure

- the antecedent labor course

- maternal anesthesia

- personnel present

- instruments employed

- position and station of the fetal head

- force and duration of traction

- nature of the attempt

- immediate condition of the neonate, and any resuscitative efforts.

Closing reminders and advice

In preparing to discuss the patient’s preferences for delivery, understand clearly the risks and benefits of VE and develop a comfortable approach to sharing this information with your patient and her family. Also, if VE is selected, consider performing the procedure in the cesarean delivery room. This will serve to remind you to be mindful to abandon the procedure, if need be, at an appropriate point.

CASE: Resolved

You apply the vacuum extractor, and a small amount of vacuum demonstrates satisfactory attachment. On the second pull, the fetus easily delivers, and the Apgar scores are 8 and 8. The birthweight is 3,725 g. The vacuum-assisted delivery has resulted in the shortest delay in delivery and without adverse consequences for neonate or mother.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 154 Summary: operative vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1118–1119.

- Baskett TF, Fanning CA, Young DC. A prospective observational study of 1000 vacuum assisted deliveries with the OmniCup device. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(7):573–580.

- O’Grady JP. Instrumental delivery. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello LA, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008:475.

- Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1709–1714.

CASE: Is vacuum extraction right for this delivery?

A 41-year-old woman (G2P2002) is at term in her third pregnancy, and the fetus exhibits prolonged deceleration that does not resolve while the mother pushes from a +3 station. The fetus, estimated to weigh 8 lb, is in the occiput anterior (OA) position. The mother is willing to consider vaginal extraction, and you must weigh the factors that may influence successful delivery.

Vacuum extraction (VE) is an effective method to facilitate delivery. From 2007 to 2013, VE was used to facilitate about 3% of vaginal deliveries in the United States.1 By contrast, cesarean delivery rates over the same period averaged about 30%.2

Controversy exists on the pros and cons of operative vaginal deliveries versus cesarean delivery, as well as on the instruments and operational approaches used. While opinion tends to be resolute and influential, evidence remains inconclusive.

Multiple factors influence a decision on whether to choose VE. The clinician’s own bias regarding delivery routes and comfort level with performing VE are important. The patient, too, may have preconceived opinions about VE. Knowing the indications for VE and its benefits and risks (TABLE 1) can help the patient make an informed choice and the counseling on which will be needed in obtaining the patient’s informed consent. The expectations and desires of the patient in concert with the experience and skill of the clinician will serve to achieve the optimal decision.

Indications for VE

Maternal indications for the use of VE include prolongation or arrest of the second stage of labor. Another indication is the need to shorten the second stage due to a maternal cardiac or cardiovascular disorder or due to maternal exhaustion.

Fetal indications include nonreassuring fetal status or a need to correct for minor degrees of malposition (asynclitism, deflexion) that historically have been addressed with the use of obstetric forceps. VE delivery in these circumstances requires a very experienced and skilled operator.

Further selection criteria

Birthweight influences the consideration of VE. Low birthweight or prematurity are contraindications to the use of VE due to concerns about fetal/neonatal bleeding. Large fetuses will have issues with cephalopelvic disproportion, thus increasing the risk for 2 disorders: shoulder dystocia and fetal cranial bleeding.

Cranial bleeding, both intracranial and extracranial, can result in serious neonatal morbidity and mortality. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or with the use of VE. In using VE, force is transmitted to the fetal scalp. The scalp then has the tendency to pull on its contents and attachments—skull bones, brain, fluids, etc. The scalp attachments include vessels at right angles to the scalp, which may be traumatized or torn by the pulling force. This may lead to subgaleal hemorrhage, a collection of blood in the large potential space below the scalp and above the aponeurosis. Enough force may be generated to deform the intracranial contents and cause intracranial bleeding.

The likelihood of success with VE varies depending on maternal anatomy, the position of the fetal head, gestational age, and the presence or absence of gestational diabetes (TABLE 2).

Delivery by VE: Main considerations

After determining that a candidate is suitable for VE and obtaining informed consent, consider key operative factors:

- choice of extraction cup

- adequate anesthesia

- careful maternal positioning

- maternal bladder emptying

- review of fetal status.

Two major cup types are available: rigid and flexible.

Rigid plastic cup. This design is similar to the metal cup used by Malmström and attaches to the scalp via chignon formation. A variation of the rigid cup is the mityvac “M” that mimics the Malmström design but incorporates a semiflexible handle to facilitate proper cup placement and aid in the direction of pulling force.

Flexible cup. This type of cup flattens against the scalp with vacuum and may result in less minor scalp trauma than the rigid cup.

Greater force can be employed with rigid cup designs than with flexible cups, which can increase the chances of a successful delivery when the fetus is in the occiput posterior (OP) position. Flexible designs tend to cause less damage to the scalp than the rigid cup but are reported to have a higher failure rate.

Cardinal rule of any procedure. Prior to cup placement, remember this rule: abandon the procedure if it proves too difficult. Most deliveries will occur with 3 or 4 pulls.3 Difficulties include:

- failure to gain station with the initial pull

- repetitive cup pop-offs (3 or more)

- an excessive duration of the procedure (>10 minutes).

Less than optimal placement of the vacuum extractor will increase the risk of scalp trauma, particularly in nulliparous women.3

If the procedure is unsuccessful, the resulting options include cesarean delivery and expectant management.

Tip. Use both hands during the pull to more reliably detect a problem with cup attachment, thereby minimizing the possibility of detachment and subsequent scalp trauma (FIGURE).

Key points of technique

Perform a careful and thorough pelvic examination to determine fetal station, position, attitude, and synclitism.

The optimal cup placement is 2- to 3-cm proximal to the posterior fontanel or, alternatively, 5- to 6-cm distal to the anterior fontanel, assuming the fetal head is properly flexed.4 The correct point of flexion will result in the smallest diameter of the fetal head presenting to the birth canal and should minimize the force necessary to achieve delivery.

Use minimal vacuum to attach the cup to the fetal head. As the subsequent contraction develops, apply full vacuum with the hand device. Encourage maternal expulsive effort and use traction only in concert with pushing efforts. Three pushes facilitated with pulling may be achieved during a single contraction. Failure to bring about descent with the initial pull indicates potential failure with this approach and, in the absence of technical reasons for the failure, merits serious consideration of abandoning the procedure (TABLE 3).

In the event of failed delivery with VE, it is important to recognize that you should not make a second attempt with another instrument; the chance of success is low and the risk of injury is significantly increased.5

Carefully document the decision for VE and its implementation

The medical record is the most important witness to the event. Clearly record the following items, preferably as close in time to the decision/event as possible:

- the indication for the procedure

- the antecedent labor course

- maternal anesthesia

- personnel present

- instruments employed

- position and station of the fetal head

- force and duration of traction

- nature of the attempt

- immediate condition of the neonate, and any resuscitative efforts.

Closing reminders and advice

In preparing to discuss the patient’s preferences for delivery, understand clearly the risks and benefits of VE and develop a comfortable approach to sharing this information with your patient and her family. Also, if VE is selected, consider performing the procedure in the cesarean delivery room. This will serve to remind you to be mindful to abandon the procedure, if need be, at an appropriate point.

CASE: Resolved

You apply the vacuum extractor, and a small amount of vacuum demonstrates satisfactory attachment. On the second pull, the fetus easily delivers, and the Apgar scores are 8 and 8. The birthweight is 3,725 g. The vacuum-assisted delivery has resulted in the shortest delay in delivery and without adverse consequences for neonate or mother.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Is vacuum extraction right for this delivery?

A 41-year-old woman (G2P2002) is at term in her third pregnancy, and the fetus exhibits prolonged deceleration that does not resolve while the mother pushes from a +3 station. The fetus, estimated to weigh 8 lb, is in the occiput anterior (OA) position. The mother is willing to consider vaginal extraction, and you must weigh the factors that may influence successful delivery.

Vacuum extraction (VE) is an effective method to facilitate delivery. From 2007 to 2013, VE was used to facilitate about 3% of vaginal deliveries in the United States.1 By contrast, cesarean delivery rates over the same period averaged about 30%.2

Controversy exists on the pros and cons of operative vaginal deliveries versus cesarean delivery, as well as on the instruments and operational approaches used. While opinion tends to be resolute and influential, evidence remains inconclusive.

Multiple factors influence a decision on whether to choose VE. The clinician’s own bias regarding delivery routes and comfort level with performing VE are important. The patient, too, may have preconceived opinions about VE. Knowing the indications for VE and its benefits and risks (TABLE 1) can help the patient make an informed choice and the counseling on which will be needed in obtaining the patient’s informed consent. The expectations and desires of the patient in concert with the experience and skill of the clinician will serve to achieve the optimal decision.

Indications for VE

Maternal indications for the use of VE include prolongation or arrest of the second stage of labor. Another indication is the need to shorten the second stage due to a maternal cardiac or cardiovascular disorder or due to maternal exhaustion.

Fetal indications include nonreassuring fetal status or a need to correct for minor degrees of malposition (asynclitism, deflexion) that historically have been addressed with the use of obstetric forceps. VE delivery in these circumstances requires a very experienced and skilled operator.

Further selection criteria

Birthweight influences the consideration of VE. Low birthweight or prematurity are contraindications to the use of VE due to concerns about fetal/neonatal bleeding. Large fetuses will have issues with cephalopelvic disproportion, thus increasing the risk for 2 disorders: shoulder dystocia and fetal cranial bleeding.

Cranial bleeding, both intracranial and extracranial, can result in serious neonatal morbidity and mortality. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or with the use of VE. In using VE, force is transmitted to the fetal scalp. The scalp then has the tendency to pull on its contents and attachments—skull bones, brain, fluids, etc. The scalp attachments include vessels at right angles to the scalp, which may be traumatized or torn by the pulling force. This may lead to subgaleal hemorrhage, a collection of blood in the large potential space below the scalp and above the aponeurosis. Enough force may be generated to deform the intracranial contents and cause intracranial bleeding.

The likelihood of success with VE varies depending on maternal anatomy, the position of the fetal head, gestational age, and the presence or absence of gestational diabetes (TABLE 2).

Delivery by VE: Main considerations

After determining that a candidate is suitable for VE and obtaining informed consent, consider key operative factors:

- choice of extraction cup

- adequate anesthesia

- careful maternal positioning

- maternal bladder emptying

- review of fetal status.

Two major cup types are available: rigid and flexible.

Rigid plastic cup. This design is similar to the metal cup used by Malmström and attaches to the scalp via chignon formation. A variation of the rigid cup is the mityvac “M” that mimics the Malmström design but incorporates a semiflexible handle to facilitate proper cup placement and aid in the direction of pulling force.

Flexible cup. This type of cup flattens against the scalp with vacuum and may result in less minor scalp trauma than the rigid cup.

Greater force can be employed with rigid cup designs than with flexible cups, which can increase the chances of a successful delivery when the fetus is in the occiput posterior (OP) position. Flexible designs tend to cause less damage to the scalp than the rigid cup but are reported to have a higher failure rate.

Cardinal rule of any procedure. Prior to cup placement, remember this rule: abandon the procedure if it proves too difficult. Most deliveries will occur with 3 or 4 pulls.3 Difficulties include:

- failure to gain station with the initial pull

- repetitive cup pop-offs (3 or more)

- an excessive duration of the procedure (>10 minutes).

Less than optimal placement of the vacuum extractor will increase the risk of scalp trauma, particularly in nulliparous women.3

If the procedure is unsuccessful, the resulting options include cesarean delivery and expectant management.

Tip. Use both hands during the pull to more reliably detect a problem with cup attachment, thereby minimizing the possibility of detachment and subsequent scalp trauma (FIGURE).

Key points of technique

Perform a careful and thorough pelvic examination to determine fetal station, position, attitude, and synclitism.

The optimal cup placement is 2- to 3-cm proximal to the posterior fontanel or, alternatively, 5- to 6-cm distal to the anterior fontanel, assuming the fetal head is properly flexed.4 The correct point of flexion will result in the smallest diameter of the fetal head presenting to the birth canal and should minimize the force necessary to achieve delivery.

Use minimal vacuum to attach the cup to the fetal head. As the subsequent contraction develops, apply full vacuum with the hand device. Encourage maternal expulsive effort and use traction only in concert with pushing efforts. Three pushes facilitated with pulling may be achieved during a single contraction. Failure to bring about descent with the initial pull indicates potential failure with this approach and, in the absence of technical reasons for the failure, merits serious consideration of abandoning the procedure (TABLE 3).

In the event of failed delivery with VE, it is important to recognize that you should not make a second attempt with another instrument; the chance of success is low and the risk of injury is significantly increased.5

Carefully document the decision for VE and its implementation

The medical record is the most important witness to the event. Clearly record the following items, preferably as close in time to the decision/event as possible:

- the indication for the procedure

- the antecedent labor course

- maternal anesthesia

- personnel present

- instruments employed

- position and station of the fetal head

- force and duration of traction

- nature of the attempt

- immediate condition of the neonate, and any resuscitative efforts.

Closing reminders and advice

In preparing to discuss the patient’s preferences for delivery, understand clearly the risks and benefits of VE and develop a comfortable approach to sharing this information with your patient and her family. Also, if VE is selected, consider performing the procedure in the cesarean delivery room. This will serve to remind you to be mindful to abandon the procedure, if need be, at an appropriate point.

CASE: Resolved

You apply the vacuum extractor, and a small amount of vacuum demonstrates satisfactory attachment. On the second pull, the fetus easily delivers, and the Apgar scores are 8 and 8. The birthweight is 3,725 g. The vacuum-assisted delivery has resulted in the shortest delay in delivery and without adverse consequences for neonate or mother.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 154 Summary: operative vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1118–1119.

- Baskett TF, Fanning CA, Young DC. A prospective observational study of 1000 vacuum assisted deliveries with the OmniCup device. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(7):573–580.

- O’Grady JP. Instrumental delivery. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello LA, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008:475.

- Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1709–1714.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 154 Summary: operative vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1118–1119.

- Baskett TF, Fanning CA, Young DC. A prospective observational study of 1000 vacuum assisted deliveries with the OmniCup device. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(7):573–580.

- O’Grady JP. Instrumental delivery. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello LA, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008:475.

- Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1709–1714.

In this Article

- Patient selection criteria

- Key technique points

- Important documentation

3 clear dos, and 3 specific don'ts, of vacuum extraction

EHRs and medicolegal risk: How they help, when they could hurt

Survey: Many physicians plan to leave or scale down practice

Janelle Yates (February 2012)

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere, MA (October 2011)

The medical record has evolved considerably since it originated in ancient Greece as a narrative of cure.1 For one thing, it’s now electronic. For another, it’s no longer a medical record but a health record. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the distinction is not a trivial one. A medical record is used by clinicians mostly for diagnosis and treatment, whereas the health record focuses on the total wellbeing of the patient.2 The medical record is used primarily within a practice. The electronic health record (EHR) reaches across borders to other offices, institutions, and clinicians.

Use of the EHR has been stimulated by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act,3 which offers grants and incentives for “meaningful use” of electronic records.4 After 2014, medical practices that do not use EHRs will face a financial penalty that amounts to 2% of 2013 clinical revenue.

EHRs have been hailed as a panacea and derided as anathema. Whatever your perspective, there is no denying that they dramatically increase the immediate and easy availability of information and, therefore, influence decision-making in regard to medical care, cost-effectiveness, and patient safety. EHRs have the potential to improve communication, broaden access to information, and help guide clinical decision-making through the use of best-practice algorithms. When used properly—which means taking advantage of the EHR’s full potential and adapting to the way information is organized and analyzed—the EHR can reduce adverse events and help defend the appropriateness of the care provided. This lowers your medicolegal risk. When used improperly or haphazardly, they may increase that risk. In this article, we elaborate on both.

EHRs have many benefits

Improved communication. EHRs facilitate communication between healthcare providers. A primary care physician can access a consultant’s report practically as it is written. Providers also can carry on a dialogue electronically, planning together for care that will best serve the patient, with less redundancy and time.

The EHR also facilitates communication between physician and patient, allowing the physician to see the patient’s recent history and plan her management while speaking to her on the phone. Issues can be addressed with greater accuracy and expediency, leading to reduced anxiety for the patient and increased compliance.

Seamless integration. Information can be entered into the EHR and integrated into the full record more seamlessly than it is with written records. And data can be entered once and used many times.

Enhanced decision-making. Decision-making depends on careful analysis of a clinical scenario. Protocols, templates, and order sets embedded in the EHR can reduce medical errors by identifying scenarios for the physician to review.5,6

The EHR can also highlight adverse drug-drug interactions and help avoid potential allergic reactions. Murphy and colleagues reported a reduction of medical errors by utilizing a pharmacy-driven EHR component—a reduction from 90% to 47% on the surgical unit and from 57% to 33% on the medicine unit.7

Improved documentation. The EHR can enhance documentation by offering specific and detailed templates for informed consent, making it more comprehensive than a handwritten notation of the risks and benefits.

Decipherability is another strength of the EHR. Because physicians are notorious for poor handwriting skills, some hospitals now require a writing sample as part of their privileging process. The EHR avoids this issue entirely.8 Typos and grammatical errors are minimized by spellchecking and grammar-correcting programs written into the EHR.

Quality assurance. Timely evaluation of approaches to clinical care is available to physicians as well as hospitals that use EHRs.9 An individual physician can perform personal quality-assurance audits. And hospital management can gather cumulative statistics more quickly and easily.5,6,10,11

Patient data can be accessed independent of medical department, with lab tests, imaging studies, and pathology reports readily available for review. And accessibility is available regardless of geographic location.

EHRs are not perfect, and neither are their users. EHRs present the potential for problems related to absent or erroneous data entry, patient privacy issues, misunderstanding and misuse of software, and development of metadata.

With initial use, EHRs can create documentation gaps with the transition from paper to electronic records. In addition, inadequate provider training can create new error pathways, and a failure to use EHRs consistently can lead to loss of data and communication errors. These gaps and errors can increase medicolegal risk, as can the more extensive documentation often seen with early use, which creates more discoverable data. The temptation to cut and paste risks repeating earlier errors and omitting new information.

Another area of risk involves communication with the patient via email. A failure to reply could result in claims of negligence, and information overload could obscure pertinent pieces of information. And a departure from clinical decision support could be used by the patient to defend allegations of negligence.

With widespread use of EHRs, improved access to data could change the “duty” owed to the patient. In addition, clinical decision support embedded within the software could become the de facto “standard of care.”

The learning curve can be steep

The learning curve for EHRs may be steep and, at times, discouraging. One reason is that data are organized differently than in the conventional paper record, where information is read and analyzed in a progressive and stepwise manner, as in an analog or vertical system. The EHR is a digital format, so finding information requires digital (horizontal) inquiry. Information is, therefore, utilized in both horizontal and vertical formats in everyday situations. If data are entered incorrectly, all subsequent decisions could be flawed. And if the EHR suggests a plan, and that plan is not performed by the provider, the risk of liability could increase.

Inadvertent violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) with an EHR could increase medicolegal risk. For example, HIPAA allows for patients to make corrections to inaccurate information in their personal documents, but access by the patient could require the physician to review all records viewed by the patient after visit notes have been entered. This could drive up the cost of practice and reduce face-to-face time between physician and patient. Patients are not necessarily the best judges of which information is most important in their medical records.

Internet access raises concerns about the privacy of sensitive issues and misuse of information. Making a patient’s protected health information accessible electronically leaves physicians and hospitals at risk for a government fine or lawsuit. In several instances, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has levied fines against small practices and government agencies.

In one case, HHS fined Phoenix Cardiac Surgery in Phoenix, Arizona, $100,000 for posting surgery and appointment schedules on an Internet-based calendar that was accessible to the public.12 In another, HHS fined the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston $1.5 million after it reported the loss of an encrypted personal laptop containing the protected health information of patients and research subjects.13 The Alaska Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) agreed to pay HHS $1.7 million after it reported the loss of a USB drive—possibly containing protected health information—from the vehicle of a DHSS employee.14

In traditional physician practices that employ handwritten records, the potential for compromise of patient information is limited. An organization may lose a few patient charts in the office and recover from the loss without incident. With the EHR, the loss poses a significant threat. The cases mentioned above were attributed to negligence or ignorance. The consequences could be worse if the compromise of EHR data is determined to be intentional. On September 4, 2010, hackers may have exposed the personal information of approximately 9,493 patients at Southwest Seattle Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine in Burien, Washington. Even with the best encryption technology, any electronic system remains vulnerable to external attack.

Metadata reveal how original data are used

Another concern regarding EHRs involves metadata—”data about data content.”15 Metadata is structured information that describes, locates, explains, or manages information. Metadata relevant to the EHR includes the data and time it was reviewed by the provider and whether it was manipulated in any way. Clearly, there is a potential for use and misuse by third-party reviewers.

Specialty-specific EHRs are recommended

Many ObGyns have found that most EHR systems are inadequate to the task of recording and analyzing information relevant to their specialty. Obstetric care is episodic and frequent. Data are added into the flow that must be considered at each visit, such as gestational age, fetal growth, labs (and normative values), prenatal diagnostic studies, and so on, representing both vertical and horizontal processing.16

The legal discovery process poses challenges that have not yet been resolved

The legal discovery process grants all parties to a lawsuit equal access to information. Under ideal circumstances, the EHR can provide comprehensive data more quickly than traditional records can. The problem is determining what constitutes relevant data and which party has the burden or benefit of making that decision. Uncontrolled access has the potential to violate privacy and privilege requirements.

Rules regarding discovery are still being debated in regard to their applicability to digital discovery.17 Even before a lawsuit is filed, the potential for “data mining” by third parties could lead to allegations of malpractice.

How to use EHRs responsibly without increasing risk

Good communication between patient and provider is paramount in the provision of quality medical care. Adherence to evidence-based standards with thorough documentation always serves the best interests of both patients and providers. The EHR can facilitate this process.

Our recommendations for appropriate use of your EHR include:

- Spend time learning the ins and outs of your particular EHR, and make sure your staff does the same. This will help reduce the likelihood that errors will be introduced into the record and ensure consistent use.

- Use individual sign-ons for anyone involved in data entry. This step facilitates the identification of users responsible for inaccurate use or errors, so that the situation can be addressed efficiently.

- Do not let third parties enter or manipulate data. This could jeopardize patient privacy, as well as the integrity of the record itself.

- Track all data entry on a regular basis. The frequency of tracking should be a function of routine as well as clinical circumstance. All new data from the previous interval should be reviewed at the time of the subsequent visit in order to direct care and ensure proper data entry.

Because of the considerable risk of liability claims in ObGyn practice, it is critical that the medical record accurately and precisely reflects the circumstances of each case. The EHR can be an effective and useful tool to document what occurred (and when) in a clinical scenario.18 As with all medical records, completeness and accuracy are the first and best defense against allegations of medical malpractice.

1. The Casebooks Project. History of Medical Record-keeping. http://www.magicandmedicine.hps.cam.ac.uk/on-astrological-medicine/further-reading/history-of-medical-record-keeping/. Accessed February 26 2013.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. EMR vs EHR—What is the difference? Health IT Buzz. http://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/electronic-health-and-medical-records/emr-vs-ehr-difference/. Accessed February 20, 2013.

3. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act of 2009. HITECH Act. Pub L No 111-5 Div A tit XIII Div B tit IV Feb 17 2009, 123 stat 226, 467. Codified in scattered sections of 42 USCA.

4. Mangalmurti S, Murtagh L, Mello M. Medical malpractice liability in the age of electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):2060-2067.

5. Reid P, Compton D, Grossman J, et al. Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Healthcare Partnership. Committee on Engineering and the Health Care System, Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

6. Grossman J. Disruptive innovation in healthcare: challenges for engineering. The Bridge. 2008;38:10-16.

7. Murphy E, Oxencis C, Klauck J, et al. Medication reconciliation at an academic medical center; implementation of a comprehensive program from admission to discharge. Am J Health-System Pharmacy. 2009;66(23):2126-2131.

8. Schuler R. The smart grid: a bridge between emerging technologies society and the environment. The Bridge. 2010;40:42-49.

9. Haberman S, Feldman J, Merhi Z, et al. Effect of clinical decision support on documentation compliance in an electronic medical record. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 Pt 1):311-317.

10. Hasley S. Decision support and patient safety: the time has come. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):461-465.

11. Lagrew D, Stutman H, Sicaeros L. Voluntary physician adoption of an inpatient electronic medical record by obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(6):690.e1-e6.

12. Dolan PL. $100,000 HIPAA fine designed to send message to small physician practices. American Medical News. 2012. http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2012/04/30/bisd0502.htm. Accessed February 26, 2013.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Massachusetts provider settles HIPAA case for $1.5 million [news release]. September 17 2012. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/09/20120917a.html. Accessed February 26, 2013.

14. US Department of Health and Human Services. Alaska settles HIPAA security case for $1,700,000 [news release]. June 26, 2012. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/06/20120626a.html. Accessed February 26, 2013.

15. National Information Standards Organization. Understanding Metadata. Bethesda MD: NISO Press; 2004. http://www.niso.org/publications/press/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2013.

16. McCoy M, Diamond A, Strunk A. Special requirements of electronic medical record systems in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):140-143.

17. The Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure: The Impact of Digital Discovery. http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitaldiscovery/digdisc_library_4.html. Accessed February 26 2013.

18. Quinn M, Kats A, Kleinman K, et al. The relationship between electronic health records and malpractice claims. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1187-1188.

Survey: Many physicians plan to leave or scale down practice

Janelle Yates (February 2012)

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere, MA (October 2011)

The medical record has evolved considerably since it originated in ancient Greece as a narrative of cure.1 For one thing, it’s now electronic. For another, it’s no longer a medical record but a health record. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the distinction is not a trivial one. A medical record is used by clinicians mostly for diagnosis and treatment, whereas the health record focuses on the total wellbeing of the patient.2 The medical record is used primarily within a practice. The electronic health record (EHR) reaches across borders to other offices, institutions, and clinicians.

Use of the EHR has been stimulated by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act,3 which offers grants and incentives for “meaningful use” of electronic records.4 After 2014, medical practices that do not use EHRs will face a financial penalty that amounts to 2% of 2013 clinical revenue.

EHRs have been hailed as a panacea and derided as anathema. Whatever your perspective, there is no denying that they dramatically increase the immediate and easy availability of information and, therefore, influence decision-making in regard to medical care, cost-effectiveness, and patient safety. EHRs have the potential to improve communication, broaden access to information, and help guide clinical decision-making through the use of best-practice algorithms. When used properly—which means taking advantage of the EHR’s full potential and adapting to the way information is organized and analyzed—the EHR can reduce adverse events and help defend the appropriateness of the care provided. This lowers your medicolegal risk. When used improperly or haphazardly, they may increase that risk. In this article, we elaborate on both.

EHRs have many benefits

Improved communication. EHRs facilitate communication between healthcare providers. A primary care physician can access a consultant’s report practically as it is written. Providers also can carry on a dialogue electronically, planning together for care that will best serve the patient, with less redundancy and time.

The EHR also facilitates communication between physician and patient, allowing the physician to see the patient’s recent history and plan her management while speaking to her on the phone. Issues can be addressed with greater accuracy and expediency, leading to reduced anxiety for the patient and increased compliance.

Seamless integration. Information can be entered into the EHR and integrated into the full record more seamlessly than it is with written records. And data can be entered once and used many times.

Enhanced decision-making. Decision-making depends on careful analysis of a clinical scenario. Protocols, templates, and order sets embedded in the EHR can reduce medical errors by identifying scenarios for the physician to review.5,6

The EHR can also highlight adverse drug-drug interactions and help avoid potential allergic reactions. Murphy and colleagues reported a reduction of medical errors by utilizing a pharmacy-driven EHR component—a reduction from 90% to 47% on the surgical unit and from 57% to 33% on the medicine unit.7

Improved documentation. The EHR can enhance documentation by offering specific and detailed templates for informed consent, making it more comprehensive than a handwritten notation of the risks and benefits.

Decipherability is another strength of the EHR. Because physicians are notorious for poor handwriting skills, some hospitals now require a writing sample as part of their privileging process. The EHR avoids this issue entirely.8 Typos and grammatical errors are minimized by spellchecking and grammar-correcting programs written into the EHR.

Quality assurance. Timely evaluation of approaches to clinical care is available to physicians as well as hospitals that use EHRs.9 An individual physician can perform personal quality-assurance audits. And hospital management can gather cumulative statistics more quickly and easily.5,6,10,11

Patient data can be accessed independent of medical department, with lab tests, imaging studies, and pathology reports readily available for review. And accessibility is available regardless of geographic location.

EHRs are not perfect, and neither are their users. EHRs present the potential for problems related to absent or erroneous data entry, patient privacy issues, misunderstanding and misuse of software, and development of metadata.

With initial use, EHRs can create documentation gaps with the transition from paper to electronic records. In addition, inadequate provider training can create new error pathways, and a failure to use EHRs consistently can lead to loss of data and communication errors. These gaps and errors can increase medicolegal risk, as can the more extensive documentation often seen with early use, which creates more discoverable data. The temptation to cut and paste risks repeating earlier errors and omitting new information.

Another area of risk involves communication with the patient via email. A failure to reply could result in claims of negligence, and information overload could obscure pertinent pieces of information. And a departure from clinical decision support could be used by the patient to defend allegations of negligence.

With widespread use of EHRs, improved access to data could change the “duty” owed to the patient. In addition, clinical decision support embedded within the software could become the de facto “standard of care.”

The learning curve can be steep

The learning curve for EHRs may be steep and, at times, discouraging. One reason is that data are organized differently than in the conventional paper record, where information is read and analyzed in a progressive and stepwise manner, as in an analog or vertical system. The EHR is a digital format, so finding information requires digital (horizontal) inquiry. Information is, therefore, utilized in both horizontal and vertical formats in everyday situations. If data are entered incorrectly, all subsequent decisions could be flawed. And if the EHR suggests a plan, and that plan is not performed by the provider, the risk of liability could increase.

Inadvertent violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) with an EHR could increase medicolegal risk. For example, HIPAA allows for patients to make corrections to inaccurate information in their personal documents, but access by the patient could require the physician to review all records viewed by the patient after visit notes have been entered. This could drive up the cost of practice and reduce face-to-face time between physician and patient. Patients are not necessarily the best judges of which information is most important in their medical records.

Internet access raises concerns about the privacy of sensitive issues and misuse of information. Making a patient’s protected health information accessible electronically leaves physicians and hospitals at risk for a government fine or lawsuit. In several instances, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has levied fines against small practices and government agencies.

In one case, HHS fined Phoenix Cardiac Surgery in Phoenix, Arizona, $100,000 for posting surgery and appointment schedules on an Internet-based calendar that was accessible to the public.12 In another, HHS fined the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston $1.5 million after it reported the loss of an encrypted personal laptop containing the protected health information of patients and research subjects.13 The Alaska Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) agreed to pay HHS $1.7 million after it reported the loss of a USB drive—possibly containing protected health information—from the vehicle of a DHSS employee.14

In traditional physician practices that employ handwritten records, the potential for compromise of patient information is limited. An organization may lose a few patient charts in the office and recover from the loss without incident. With the EHR, the loss poses a significant threat. The cases mentioned above were attributed to negligence or ignorance. The consequences could be worse if the compromise of EHR data is determined to be intentional. On September 4, 2010, hackers may have exposed the personal information of approximately 9,493 patients at Southwest Seattle Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine in Burien, Washington. Even with the best encryption technology, any electronic system remains vulnerable to external attack.

Metadata reveal how original data are used

Another concern regarding EHRs involves metadata—”data about data content.”15 Metadata is structured information that describes, locates, explains, or manages information. Metadata relevant to the EHR includes the data and time it was reviewed by the provider and whether it was manipulated in any way. Clearly, there is a potential for use and misuse by third-party reviewers.

Specialty-specific EHRs are recommended

Many ObGyns have found that most EHR systems are inadequate to the task of recording and analyzing information relevant to their specialty. Obstetric care is episodic and frequent. Data are added into the flow that must be considered at each visit, such as gestational age, fetal growth, labs (and normative values), prenatal diagnostic studies, and so on, representing both vertical and horizontal processing.16

The legal discovery process poses challenges that have not yet been resolved

The legal discovery process grants all parties to a lawsuit equal access to information. Under ideal circumstances, the EHR can provide comprehensive data more quickly than traditional records can. The problem is determining what constitutes relevant data and which party has the burden or benefit of making that decision. Uncontrolled access has the potential to violate privacy and privilege requirements.

Rules regarding discovery are still being debated in regard to their applicability to digital discovery.17 Even before a lawsuit is filed, the potential for “data mining” by third parties could lead to allegations of malpractice.

How to use EHRs responsibly without increasing risk

Good communication between patient and provider is paramount in the provision of quality medical care. Adherence to evidence-based standards with thorough documentation always serves the best interests of both patients and providers. The EHR can facilitate this process.

Our recommendations for appropriate use of your EHR include:

- Spend time learning the ins and outs of your particular EHR, and make sure your staff does the same. This will help reduce the likelihood that errors will be introduced into the record and ensure consistent use.

- Use individual sign-ons for anyone involved in data entry. This step facilitates the identification of users responsible for inaccurate use or errors, so that the situation can be addressed efficiently.

- Do not let third parties enter or manipulate data. This could jeopardize patient privacy, as well as the integrity of the record itself.

- Track all data entry on a regular basis. The frequency of tracking should be a function of routine as well as clinical circumstance. All new data from the previous interval should be reviewed at the time of the subsequent visit in order to direct care and ensure proper data entry.

Because of the considerable risk of liability claims in ObGyn practice, it is critical that the medical record accurately and precisely reflects the circumstances of each case. The EHR can be an effective and useful tool to document what occurred (and when) in a clinical scenario.18 As with all medical records, completeness and accuracy are the first and best defense against allegations of medical malpractice.

Survey: Many physicians plan to leave or scale down practice

Janelle Yates (February 2012)

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere, MA (October 2011)

The medical record has evolved considerably since it originated in ancient Greece as a narrative of cure.1 For one thing, it’s now electronic. For another, it’s no longer a medical record but a health record. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the distinction is not a trivial one. A medical record is used by clinicians mostly for diagnosis and treatment, whereas the health record focuses on the total wellbeing of the patient.2 The medical record is used primarily within a practice. The electronic health record (EHR) reaches across borders to other offices, institutions, and clinicians.

Use of the EHR has been stimulated by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act,3 which offers grants and incentives for “meaningful use” of electronic records.4 After 2014, medical practices that do not use EHRs will face a financial penalty that amounts to 2% of 2013 clinical revenue.

EHRs have been hailed as a panacea and derided as anathema. Whatever your perspective, there is no denying that they dramatically increase the immediate and easy availability of information and, therefore, influence decision-making in regard to medical care, cost-effectiveness, and patient safety. EHRs have the potential to improve communication, broaden access to information, and help guide clinical decision-making through the use of best-practice algorithms. When used properly—which means taking advantage of the EHR’s full potential and adapting to the way information is organized and analyzed—the EHR can reduce adverse events and help defend the appropriateness of the care provided. This lowers your medicolegal risk. When used improperly or haphazardly, they may increase that risk. In this article, we elaborate on both.

EHRs have many benefits

Improved communication. EHRs facilitate communication between healthcare providers. A primary care physician can access a consultant’s report practically as it is written. Providers also can carry on a dialogue electronically, planning together for care that will best serve the patient, with less redundancy and time.

The EHR also facilitates communication between physician and patient, allowing the physician to see the patient’s recent history and plan her management while speaking to her on the phone. Issues can be addressed with greater accuracy and expediency, leading to reduced anxiety for the patient and increased compliance.

Seamless integration. Information can be entered into the EHR and integrated into the full record more seamlessly than it is with written records. And data can be entered once and used many times.

Enhanced decision-making. Decision-making depends on careful analysis of a clinical scenario. Protocols, templates, and order sets embedded in the EHR can reduce medical errors by identifying scenarios for the physician to review.5,6

The EHR can also highlight adverse drug-drug interactions and help avoid potential allergic reactions. Murphy and colleagues reported a reduction of medical errors by utilizing a pharmacy-driven EHR component—a reduction from 90% to 47% on the surgical unit and from 57% to 33% on the medicine unit.7

Improved documentation. The EHR can enhance documentation by offering specific and detailed templates for informed consent, making it more comprehensive than a handwritten notation of the risks and benefits.

Decipherability is another strength of the EHR. Because physicians are notorious for poor handwriting skills, some hospitals now require a writing sample as part of their privileging process. The EHR avoids this issue entirely.8 Typos and grammatical errors are minimized by spellchecking and grammar-correcting programs written into the EHR.

Quality assurance. Timely evaluation of approaches to clinical care is available to physicians as well as hospitals that use EHRs.9 An individual physician can perform personal quality-assurance audits. And hospital management can gather cumulative statistics more quickly and easily.5,6,10,11

Patient data can be accessed independent of medical department, with lab tests, imaging studies, and pathology reports readily available for review. And accessibility is available regardless of geographic location.

EHRs are not perfect, and neither are their users. EHRs present the potential for problems related to absent or erroneous data entry, patient privacy issues, misunderstanding and misuse of software, and development of metadata.

With initial use, EHRs can create documentation gaps with the transition from paper to electronic records. In addition, inadequate provider training can create new error pathways, and a failure to use EHRs consistently can lead to loss of data and communication errors. These gaps and errors can increase medicolegal risk, as can the more extensive documentation often seen with early use, which creates more discoverable data. The temptation to cut and paste risks repeating earlier errors and omitting new information.

Another area of risk involves communication with the patient via email. A failure to reply could result in claims of negligence, and information overload could obscure pertinent pieces of information. And a departure from clinical decision support could be used by the patient to defend allegations of negligence.

With widespread use of EHRs, improved access to data could change the “duty” owed to the patient. In addition, clinical decision support embedded within the software could become the de facto “standard of care.”

The learning curve can be steep

The learning curve for EHRs may be steep and, at times, discouraging. One reason is that data are organized differently than in the conventional paper record, where information is read and analyzed in a progressive and stepwise manner, as in an analog or vertical system. The EHR is a digital format, so finding information requires digital (horizontal) inquiry. Information is, therefore, utilized in both horizontal and vertical formats in everyday situations. If data are entered incorrectly, all subsequent decisions could be flawed. And if the EHR suggests a plan, and that plan is not performed by the provider, the risk of liability could increase.

Inadvertent violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) with an EHR could increase medicolegal risk. For example, HIPAA allows for patients to make corrections to inaccurate information in their personal documents, but access by the patient could require the physician to review all records viewed by the patient after visit notes have been entered. This could drive up the cost of practice and reduce face-to-face time between physician and patient. Patients are not necessarily the best judges of which information is most important in their medical records.

Internet access raises concerns about the privacy of sensitive issues and misuse of information. Making a patient’s protected health information accessible electronically leaves physicians and hospitals at risk for a government fine or lawsuit. In several instances, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has levied fines against small practices and government agencies.

In one case, HHS fined Phoenix Cardiac Surgery in Phoenix, Arizona, $100,000 for posting surgery and appointment schedules on an Internet-based calendar that was accessible to the public.12 In another, HHS fined the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston $1.5 million after it reported the loss of an encrypted personal laptop containing the protected health information of patients and research subjects.13 The Alaska Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) agreed to pay HHS $1.7 million after it reported the loss of a USB drive—possibly containing protected health information—from the vehicle of a DHSS employee.14

In traditional physician practices that employ handwritten records, the potential for compromise of patient information is limited. An organization may lose a few patient charts in the office and recover from the loss without incident. With the EHR, the loss poses a significant threat. The cases mentioned above were attributed to negligence or ignorance. The consequences could be worse if the compromise of EHR data is determined to be intentional. On September 4, 2010, hackers may have exposed the personal information of approximately 9,493 patients at Southwest Seattle Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine in Burien, Washington. Even with the best encryption technology, any electronic system remains vulnerable to external attack.

Metadata reveal how original data are used

Another concern regarding EHRs involves metadata—”data about data content.”15 Metadata is structured information that describes, locates, explains, or manages information. Metadata relevant to the EHR includes the data and time it was reviewed by the provider and whether it was manipulated in any way. Clearly, there is a potential for use and misuse by third-party reviewers.

Specialty-specific EHRs are recommended

Many ObGyns have found that most EHR systems are inadequate to the task of recording and analyzing information relevant to their specialty. Obstetric care is episodic and frequent. Data are added into the flow that must be considered at each visit, such as gestational age, fetal growth, labs (and normative values), prenatal diagnostic studies, and so on, representing both vertical and horizontal processing.16

The legal discovery process poses challenges that have not yet been resolved

The legal discovery process grants all parties to a lawsuit equal access to information. Under ideal circumstances, the EHR can provide comprehensive data more quickly than traditional records can. The problem is determining what constitutes relevant data and which party has the burden or benefit of making that decision. Uncontrolled access has the potential to violate privacy and privilege requirements.

Rules regarding discovery are still being debated in regard to their applicability to digital discovery.17 Even before a lawsuit is filed, the potential for “data mining” by third parties could lead to allegations of malpractice.

How to use EHRs responsibly without increasing risk

Good communication between patient and provider is paramount in the provision of quality medical care. Adherence to evidence-based standards with thorough documentation always serves the best interests of both patients and providers. The EHR can facilitate this process.

Our recommendations for appropriate use of your EHR include:

- Spend time learning the ins and outs of your particular EHR, and make sure your staff does the same. This will help reduce the likelihood that errors will be introduced into the record and ensure consistent use.

- Use individual sign-ons for anyone involved in data entry. This step facilitates the identification of users responsible for inaccurate use or errors, so that the situation can be addressed efficiently.

- Do not let third parties enter or manipulate data. This could jeopardize patient privacy, as well as the integrity of the record itself.

- Track all data entry on a regular basis. The frequency of tracking should be a function of routine as well as clinical circumstance. All new data from the previous interval should be reviewed at the time of the subsequent visit in order to direct care and ensure proper data entry.

Because of the considerable risk of liability claims in ObGyn practice, it is critical that the medical record accurately and precisely reflects the circumstances of each case. The EHR can be an effective and useful tool to document what occurred (and when) in a clinical scenario.18 As with all medical records, completeness and accuracy are the first and best defense against allegations of medical malpractice.

1. The Casebooks Project. History of Medical Record-keeping. http://www.magicandmedicine.hps.cam.ac.uk/on-astrological-medicine/further-reading/history-of-medical-record-keeping/. Accessed February 26 2013.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. EMR vs EHR—What is the difference? Health IT Buzz. http://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/electronic-health-and-medical-records/emr-vs-ehr-difference/. Accessed February 20, 2013.

3. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act of 2009. HITECH Act. Pub L No 111-5 Div A tit XIII Div B tit IV Feb 17 2009, 123 stat 226, 467. Codified in scattered sections of 42 USCA.

4. Mangalmurti S, Murtagh L, Mello M. Medical malpractice liability in the age of electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):2060-2067.

5. Reid P, Compton D, Grossman J, et al. Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Healthcare Partnership. Committee on Engineering and the Health Care System, Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

6. Grossman J. Disruptive innovation in healthcare: challenges for engineering. The Bridge. 2008;38:10-16.

7. Murphy E, Oxencis C, Klauck J, et al. Medication reconciliation at an academic medical center; implementation of a comprehensive program from admission to discharge. Am J Health-System Pharmacy. 2009;66(23):2126-2131.

8. Schuler R. The smart grid: a bridge between emerging technologies society and the environment. The Bridge. 2010;40:42-49.

9. Haberman S, Feldman J, Merhi Z, et al. Effect of clinical decision support on documentation compliance in an electronic medical record. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 Pt 1):311-317.

10. Hasley S. Decision support and patient safety: the time has come. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):461-465.

11. Lagrew D, Stutman H, Sicaeros L. Voluntary physician adoption of an inpatient electronic medical record by obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(6):690.e1-e6.

12. Dolan PL. $100,000 HIPAA fine designed to send message to small physician practices. American Medical News. 2012. http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2012/04/30/bisd0502.htm. Accessed February 26, 2013.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Massachusetts provider settles HIPAA case for $1.5 million [news release]. September 17 2012. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/09/20120917a.html. Accessed February 26, 2013.

14. US Department of Health and Human Services. Alaska settles HIPAA security case for $1,700,000 [news release]. June 26, 2012. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/06/20120626a.html. Accessed February 26, 2013.

15. National Information Standards Organization. Understanding Metadata. Bethesda MD: NISO Press; 2004. http://www.niso.org/publications/press/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2013.

16. McCoy M, Diamond A, Strunk A. Special requirements of electronic medical record systems in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):140-143.

17. The Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure: The Impact of Digital Discovery. http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitaldiscovery/digdisc_library_4.html. Accessed February 26 2013.

18. Quinn M, Kats A, Kleinman K, et al. The relationship between electronic health records and malpractice claims. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1187-1188.

1. The Casebooks Project. History of Medical Record-keeping. http://www.magicandmedicine.hps.cam.ac.uk/on-astrological-medicine/further-reading/history-of-medical-record-keeping/. Accessed February 26 2013.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. EMR vs EHR—What is the difference? Health IT Buzz. http://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/electronic-health-and-medical-records/emr-vs-ehr-difference/. Accessed February 20, 2013.

3. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act of 2009. HITECH Act. Pub L No 111-5 Div A tit XIII Div B tit IV Feb 17 2009, 123 stat 226, 467. Codified in scattered sections of 42 USCA.

4. Mangalmurti S, Murtagh L, Mello M. Medical malpractice liability in the age of electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):2060-2067.

5. Reid P, Compton D, Grossman J, et al. Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Healthcare Partnership. Committee on Engineering and the Health Care System, Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

6. Grossman J. Disruptive innovation in healthcare: challenges for engineering. The Bridge. 2008;38:10-16.

7. Murphy E, Oxencis C, Klauck J, et al. Medication reconciliation at an academic medical center; implementation of a comprehensive program from admission to discharge. Am J Health-System Pharmacy. 2009;66(23):2126-2131.

8. Schuler R. The smart grid: a bridge between emerging technologies society and the environment. The Bridge. 2010;40:42-49.

9. Haberman S, Feldman J, Merhi Z, et al. Effect of clinical decision support on documentation compliance in an electronic medical record. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 Pt 1):311-317.

10. Hasley S. Decision support and patient safety: the time has come. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):461-465.

11. Lagrew D, Stutman H, Sicaeros L. Voluntary physician adoption of an inpatient electronic medical record by obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(6):690.e1-e6.

12. Dolan PL. $100,000 HIPAA fine designed to send message to small physician practices. American Medical News. 2012. http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2012/04/30/bisd0502.htm. Accessed February 26, 2013.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Massachusetts provider settles HIPAA case for $1.5 million [news release]. September 17 2012. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/09/20120917a.html. Accessed February 26, 2013.

14. US Department of Health and Human Services. Alaska settles HIPAA security case for $1,700,000 [news release]. June 26, 2012. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/06/20120626a.html. Accessed February 26, 2013.

15. National Information Standards Organization. Understanding Metadata. Bethesda MD: NISO Press; 2004. http://www.niso.org/publications/press/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2013.

16. McCoy M, Diamond A, Strunk A. Special requirements of electronic medical record systems in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):140-143.

17. The Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure: The Impact of Digital Discovery. http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitaldiscovery/digdisc_library_4.html. Accessed February 26 2013.

18. Quinn M, Kats A, Kleinman K, et al. The relationship between electronic health records and malpractice claims. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1187-1188.

More strategies to avoid malpractice hazards on labor and delivery

Sound strategies to avoid malpractice hazards on labor and delivery

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD, and Alexis C. Gimovsky, MD

CASE 1: Pregestational diabetes, large baby, birth injury

A 31-year-old gravida 1 is admitted to labor and delivery. She is at 39-5/7 weeks’ gestation, dated by last menstrual period and early sonogram. The woman is a pregestational diabetic and uses insulin to control her blood glucose level.

Three weeks before admission, ultrasonography (US) revealed an estimated fetal weight of 3,650 g—at the 71st percentile for gestational age.

After an unremarkable course of labor, delivery is complicated by severe shoulder dystocia. The newborn has a birth weight of 4,985 g and sustains an Erb’s palsy-type injury. The mother develops a rectovaginal fistula after a fourth-degree tear.

In the first part of this article, we discussed how an allegation of malpractice can arise because of an unexpected event or outcome for a mother in your care, or her baby, apart from any specific clinical action you undertook. We offered an example: Counseling that you provide about options for prenatal care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

In this article, we enter the realm of the hands-on practice of medicine and discuss causation: namely, the actions of a physician, in the course of managing labor and delivering a baby, that put that physician at risk of a charge of malpractice because the medical care 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed mother or newborn.

Let’s return to the opening case above and discuss key considerations for the physician. Three more cases follow that, with analysis and recommendations.

Considerations in CASE 1

- A woman who has pregestational diabetes should receive ongoing counseling about the risks of fetal anomalies, macrosomia, and problems in the neonatal period. Be certain that she understands that these risks can be ameliorated, but not eliminated, with careful blood glucose control.

- The fetus of a diabetic gravida develops a relative decrease in the ratio of head circumference-to-abdominal circumference that predisposes it to shoulder dystocia. Cesarean delivery can decrease, but not eliminate, the risk of traumatic birth injury in a diabetic mother. (Of course, cesarean delivery will, on its own, substantially increase the risk of maternal morbidity—including at any subsequent cesarean delivery.)

What do they mean? terms and concepts intended to bolster your work and protect you

It’s not easy to define what constitutes “best care” in a given clinical circumstance. Generalizations are useful, but they may possess an inherent weakness: “Best practices,” “evidence-based care,” “standardization of care,” and “uniformity of care” usually apply more usefully to populations than individuals.

Such concepts derive from broader applications in economics, politics, and science. They are useful to define a reasonable spectrum of anticipated practices, and they certainly have an expanding role in the care of patients and in medical education (TABLE). Clinical guidelines serve as strategies that may be very helpful to the clinician. All of us understand and implement appropriate care in the great majority of clinical scenarios, but none of us are, or can be, expert in all situations. Referencing and using guidelines can fill a need for a functional starting point when expertise is lacking or falls short.

Best practices result from evidence-directed decision-making. This concept logically yields a desirable uniformity of practice. Although we all believe that our experience is our best teacher, we may best serve patients if we sample knowledge and wisdom from controlled clinical trials and from the experiences of others. What is accepted local practice must also be considered important when you devise a plan of care.1,2

A selected glossary of clinical care guidelines

| Term | What does it mean? |

|---|---|

| “Best practice” | A process or activity that is believed to be more effective at delivering a particular outcome than any other when applied to a particular condition or circumstance. The idea? With proper processes, checks, and testing, a desired outcome can be delivered with fewer problems and unforeseen complications than otherwise possible.5 |

| “Evidence-based care” | The best available process or activity arising from both 1) individual expertise and 2) best external evidence derived from systematic research.6 |

| “Standard of care” | A clinical practice to maximize success and minimize risk, applied to professional decision-making.7 |

| “Uniformity of practice” | Use of systematic, literature-based research findings to develop an approach that is efficacious and safe; that maximizes benefit; and that minimizes risk.8 |

Consider the management of breech presentation that is recognized at the 36th week antepartum visit: Discussion with the patient should include 1) reference to concerns with congenital anomalies and genetic syndromes, 2) in-utero growth and development, and 3) the delivery process. The management algorithm may include external cephalic version, elective cesarean delivery before onset of labor, or cesarean delivery after onset of labor. Each approach has advocates—based on expert opinion clinical trials.