User login

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

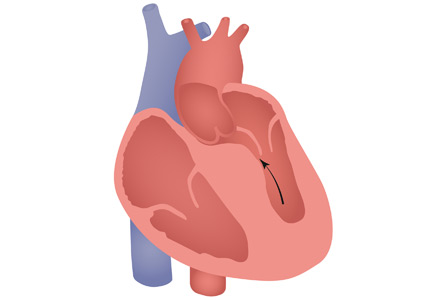

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

Cardiac mass: Tumor or thrombus?

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Patnaik et al1 about a patient who had a cardiac metastasis of ovarian cancer, and we would like to raise a few points.

It is important to clarify that metastatic cardiac tumors are not necessary malignant. Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a benign small-muscle tumor that can spread to the heart, causing various cardiac symptoms.2 Even with extensive disease, patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis may remain asymptomatic until cardiac involvement occurs. The most common cardiac symptoms are dyspnea, syncope, and lower-extremity edema.

Cardiac involvement in intravenous leiomyomatosis may occur via direct invasion or hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the tumor. In leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, cardiac invasion usually occurs via direct spread through the inferior vena cava into the right atrium and ventricle. Thus, cardiac involvement with these tumors (except for nephroma) was reported to exclusively involve the right side of the heart.

In 2014, we reported a unique case of intravenous leiomyomatosis that extended from the right side into the left side of the heart and the aorta via an atrial septal defect.2 Intracardiac extension of intravenous leiomyomatosis may result in pulmonary embolism, systemic embolization if involving the left side, and, rarely, sudden death.2

In patients with malignancy, differentiating between thrombosis and tumor is critical. These patients have a hypercoagulable state and a fourfold increase in thrombosis risk, and chemotherapy increases this risk even more.3 Although tissue pathology examination is important for differentiating thrombosis from tumor, visualization of the direct extension of the mass from the primary source into the heart through the inferior vena cava by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may help in making this distinction.2

- Patnaik S, Shah M, Sharma S, Ram P, Rammohan HS, Rubin A. A large mass in the right ventricle: tumor or thrombus? Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:517–519.

- Abdelghany M, Sodagam A, Patel P, Goldblatt C, Patel R. Intracardiac atypical leiomyoma involving all four cardiac chambers and the aorta. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2014; 15:271–275.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:4902–4907.

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Patnaik et al1 about a patient who had a cardiac metastasis of ovarian cancer, and we would like to raise a few points.

It is important to clarify that metastatic cardiac tumors are not necessary malignant. Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a benign small-muscle tumor that can spread to the heart, causing various cardiac symptoms.2 Even with extensive disease, patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis may remain asymptomatic until cardiac involvement occurs. The most common cardiac symptoms are dyspnea, syncope, and lower-extremity edema.

Cardiac involvement in intravenous leiomyomatosis may occur via direct invasion or hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the tumor. In leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, cardiac invasion usually occurs via direct spread through the inferior vena cava into the right atrium and ventricle. Thus, cardiac involvement with these tumors (except for nephroma) was reported to exclusively involve the right side of the heart.

In 2014, we reported a unique case of intravenous leiomyomatosis that extended from the right side into the left side of the heart and the aorta via an atrial septal defect.2 Intracardiac extension of intravenous leiomyomatosis may result in pulmonary embolism, systemic embolization if involving the left side, and, rarely, sudden death.2

In patients with malignancy, differentiating between thrombosis and tumor is critical. These patients have a hypercoagulable state and a fourfold increase in thrombosis risk, and chemotherapy increases this risk even more.3 Although tissue pathology examination is important for differentiating thrombosis from tumor, visualization of the direct extension of the mass from the primary source into the heart through the inferior vena cava by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may help in making this distinction.2

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Patnaik et al1 about a patient who had a cardiac metastasis of ovarian cancer, and we would like to raise a few points.

It is important to clarify that metastatic cardiac tumors are not necessary malignant. Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a benign small-muscle tumor that can spread to the heart, causing various cardiac symptoms.2 Even with extensive disease, patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis may remain asymptomatic until cardiac involvement occurs. The most common cardiac symptoms are dyspnea, syncope, and lower-extremity edema.

Cardiac involvement in intravenous leiomyomatosis may occur via direct invasion or hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the tumor. In leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, cardiac invasion usually occurs via direct spread through the inferior vena cava into the right atrium and ventricle. Thus, cardiac involvement with these tumors (except for nephroma) was reported to exclusively involve the right side of the heart.

In 2014, we reported a unique case of intravenous leiomyomatosis that extended from the right side into the left side of the heart and the aorta via an atrial septal defect.2 Intracardiac extension of intravenous leiomyomatosis may result in pulmonary embolism, systemic embolization if involving the left side, and, rarely, sudden death.2

In patients with malignancy, differentiating between thrombosis and tumor is critical. These patients have a hypercoagulable state and a fourfold increase in thrombosis risk, and chemotherapy increases this risk even more.3 Although tissue pathology examination is important for differentiating thrombosis from tumor, visualization of the direct extension of the mass from the primary source into the heart through the inferior vena cava by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may help in making this distinction.2

- Patnaik S, Shah M, Sharma S, Ram P, Rammohan HS, Rubin A. A large mass in the right ventricle: tumor or thrombus? Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:517–519.

- Abdelghany M, Sodagam A, Patel P, Goldblatt C, Patel R. Intracardiac atypical leiomyoma involving all four cardiac chambers and the aorta. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2014; 15:271–275.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:4902–4907.

- Patnaik S, Shah M, Sharma S, Ram P, Rammohan HS, Rubin A. A large mass in the right ventricle: tumor or thrombus? Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:517–519.

- Abdelghany M, Sodagam A, Patel P, Goldblatt C, Patel R. Intracardiac atypical leiomyoma involving all four cardiac chambers and the aorta. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2014; 15:271–275.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:4902–4907.

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

A 64-year-old woman had a remote history of generalized fatigue, tightness of the hands, tingling and numbness of the face, joint stiffness, and bluish discoloration of the fingers that worsened with cold weather. Laboratory testing at that time had revealed an antinuclear antibody titer over 1:320 (reference range < 1:10), anti-Scl-70 antibody 100 U/mL (< 32 U/mL), and thyroid-stimulating hormone 10.78 mIU/L (0.4–5.5). Pulmonary function testing showed a pattern of restrictive lung disease. She was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, Raynaud phenomenon, and scleroderma. She was referred to a rheumatologist, who prescribed levothyroxine and penicillamine.

Despite treatment, she continued to feel fatigued, and she requested the addition of minocycline to the scleroderma treatment after seeing a report on television. Minocycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed. She reported improvement of her symptoms for the next 2 years but was then lost to follow-up with the rheumatologist. She continued to take penicillamine and minocycline as prescribed by her primary care physician.

She presented to our clinic with bluish discoloration (Figure 1) that had started 1 year before as a small area but had spread to involve the entire face, fingers, gums, teeth, and sclera, and included a dark discoloration of the neck and upper chest. She had been taking minocycline for nearly 9 years. We referred her to a dermatologist, who diagnosed minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. Her minocycline was stopped. Skin biopsy was not done, as the dermatologist was confident making the diagnosis without biopsy. At 1 year later, she continued to have the widespread skin pigmentation with no improvement at all.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hyperpigmentation is the darkening in the natural color of the skin, usually from increased deposition of melanin in the epidermis or dermis, or both. It can occur in different degrees of blue, brown, and black (from lightest to darkest). Less frequently, it may be caused by the deposition in the dermis of an endogenous or exogenous pigment, such as hemosiderin, iron, or heavy metal.1 The hyperpigmentation can be circumscribed or more diffuse.

The differential diagnosis of diffuse skin pigmentation includes Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, cutaneous malignancies, sunburn, and drug-induced hyperpigmentation.1,2 Medications commonly cited as causing hyperpigmentation include minocycline, amiodarone, bleomycin, prostaglandins, oral contraceptives, phenothiazine, and antimalarial drugs.1,3 In Addison disease, the pigmentation is typically diffuse, with accentuation in sun-exposed areas, flexures, palmar and plantar creases, and areas of pressure or friction.2 The bronze discoloration of hemochromatosis is from a combination of hemosiderin deposition and increased melanin production.1 Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents with brownish oval-shaped macules and patches. Early lesions may have thin, raised, erythematous borders that typically involve the trunk, but they may spread to the neck, upper extremities, and face.4

The role of minocycline in the treatment of scleroderma is controversial. Early reports involving a small number of patients showed a benefit of minocycline in decreasing symptoms,5,6 but these findings were not achieved in a larger multicenter trial.7

Types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Three types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation occur3,8:

- Type 1—blue-grey coloration on the face in areas of inflammation

- Type 2—blue-grey coloration on normal skin on the skin of the shins and forearms

- Type 3—the least common, characterized by diffuse muddy brown or blue-grey discoloration in sun-exposed areas, as in our patient.

The prevalence of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation varies between 2.4% and 41% and is highest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,9 Type 1 pigmentation is not correlated with treatment duration or cumulative dose, while type 2 and 3 are associated with long-term therapy.8 In type 3, changes are nonspecific, consisting of increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and melanin-only staining dermal melanophages. Types 1 and 2 may resolve slowly, whereas type 3 can persist indefinitely.3,8,10

TREATMENT

Treatment involves early recognition, discontinuation of the drug, and avoidance of sun exposure. Treatment with pigment-specific lasers has shown promise.8,10

- Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults: Part I. Diagnostic approach, café au lait macules, diffuse hyperpigmentation, sun exposure, and phototoxic reactions. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68:1955–1960.

- Thiboutot DM. Clinical review 74: dermatological manifestations of endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80:3082–3087.

- Geria AN, Tajirian AL, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA. Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2009; 17:123–126.

- Schwartz RA. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: the continuing enigma of Cinderella or ashy dermatosis. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:230–232.

- Le CH, Morales A, Trentham DE. Minocycline in early diffuse scleroderma. Lancet 1998; 352:1755–1756.

- Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:267–269.

- Mayes MD, O’Donnell D, Rothfield NF, Csuka ME. Minocycline is not effective in systemic sclerosis: results of an open-label multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:553–557.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. London, UK: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:125–126.

- Roberts G, Capell HA. The frequency and distribution of minocycline induced hyperpigmentation in a rheumatoid arthritis population. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1254–1257.

- Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, Friedman PM. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med 2016; 48:234–237.

A 64-year-old woman had a remote history of generalized fatigue, tightness of the hands, tingling and numbness of the face, joint stiffness, and bluish discoloration of the fingers that worsened with cold weather. Laboratory testing at that time had revealed an antinuclear antibody titer over 1:320 (reference range < 1:10), anti-Scl-70 antibody 100 U/mL (< 32 U/mL), and thyroid-stimulating hormone 10.78 mIU/L (0.4–5.5). Pulmonary function testing showed a pattern of restrictive lung disease. She was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, Raynaud phenomenon, and scleroderma. She was referred to a rheumatologist, who prescribed levothyroxine and penicillamine.

Despite treatment, she continued to feel fatigued, and she requested the addition of minocycline to the scleroderma treatment after seeing a report on television. Minocycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed. She reported improvement of her symptoms for the next 2 years but was then lost to follow-up with the rheumatologist. She continued to take penicillamine and minocycline as prescribed by her primary care physician.

She presented to our clinic with bluish discoloration (Figure 1) that had started 1 year before as a small area but had spread to involve the entire face, fingers, gums, teeth, and sclera, and included a dark discoloration of the neck and upper chest. She had been taking minocycline for nearly 9 years. We referred her to a dermatologist, who diagnosed minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. Her minocycline was stopped. Skin biopsy was not done, as the dermatologist was confident making the diagnosis without biopsy. At 1 year later, she continued to have the widespread skin pigmentation with no improvement at all.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hyperpigmentation is the darkening in the natural color of the skin, usually from increased deposition of melanin in the epidermis or dermis, or both. It can occur in different degrees of blue, brown, and black (from lightest to darkest). Less frequently, it may be caused by the deposition in the dermis of an endogenous or exogenous pigment, such as hemosiderin, iron, or heavy metal.1 The hyperpigmentation can be circumscribed or more diffuse.

The differential diagnosis of diffuse skin pigmentation includes Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, cutaneous malignancies, sunburn, and drug-induced hyperpigmentation.1,2 Medications commonly cited as causing hyperpigmentation include minocycline, amiodarone, bleomycin, prostaglandins, oral contraceptives, phenothiazine, and antimalarial drugs.1,3 In Addison disease, the pigmentation is typically diffuse, with accentuation in sun-exposed areas, flexures, palmar and plantar creases, and areas of pressure or friction.2 The bronze discoloration of hemochromatosis is from a combination of hemosiderin deposition and increased melanin production.1 Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents with brownish oval-shaped macules and patches. Early lesions may have thin, raised, erythematous borders that typically involve the trunk, but they may spread to the neck, upper extremities, and face.4

The role of minocycline in the treatment of scleroderma is controversial. Early reports involving a small number of patients showed a benefit of minocycline in decreasing symptoms,5,6 but these findings were not achieved in a larger multicenter trial.7

Types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Three types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation occur3,8:

- Type 1—blue-grey coloration on the face in areas of inflammation

- Type 2—blue-grey coloration on normal skin on the skin of the shins and forearms

- Type 3—the least common, characterized by diffuse muddy brown or blue-grey discoloration in sun-exposed areas, as in our patient.

The prevalence of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation varies between 2.4% and 41% and is highest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,9 Type 1 pigmentation is not correlated with treatment duration or cumulative dose, while type 2 and 3 are associated with long-term therapy.8 In type 3, changes are nonspecific, consisting of increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and melanin-only staining dermal melanophages. Types 1 and 2 may resolve slowly, whereas type 3 can persist indefinitely.3,8,10

TREATMENT

Treatment involves early recognition, discontinuation of the drug, and avoidance of sun exposure. Treatment with pigment-specific lasers has shown promise.8,10

A 64-year-old woman had a remote history of generalized fatigue, tightness of the hands, tingling and numbness of the face, joint stiffness, and bluish discoloration of the fingers that worsened with cold weather. Laboratory testing at that time had revealed an antinuclear antibody titer over 1:320 (reference range < 1:10), anti-Scl-70 antibody 100 U/mL (< 32 U/mL), and thyroid-stimulating hormone 10.78 mIU/L (0.4–5.5). Pulmonary function testing showed a pattern of restrictive lung disease. She was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, Raynaud phenomenon, and scleroderma. She was referred to a rheumatologist, who prescribed levothyroxine and penicillamine.

Despite treatment, she continued to feel fatigued, and she requested the addition of minocycline to the scleroderma treatment after seeing a report on television. Minocycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed. She reported improvement of her symptoms for the next 2 years but was then lost to follow-up with the rheumatologist. She continued to take penicillamine and minocycline as prescribed by her primary care physician.

She presented to our clinic with bluish discoloration (Figure 1) that had started 1 year before as a small area but had spread to involve the entire face, fingers, gums, teeth, and sclera, and included a dark discoloration of the neck and upper chest. She had been taking minocycline for nearly 9 years. We referred her to a dermatologist, who diagnosed minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. Her minocycline was stopped. Skin biopsy was not done, as the dermatologist was confident making the diagnosis without biopsy. At 1 year later, she continued to have the widespread skin pigmentation with no improvement at all.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hyperpigmentation is the darkening in the natural color of the skin, usually from increased deposition of melanin in the epidermis or dermis, or both. It can occur in different degrees of blue, brown, and black (from lightest to darkest). Less frequently, it may be caused by the deposition in the dermis of an endogenous or exogenous pigment, such as hemosiderin, iron, or heavy metal.1 The hyperpigmentation can be circumscribed or more diffuse.

The differential diagnosis of diffuse skin pigmentation includes Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, cutaneous malignancies, sunburn, and drug-induced hyperpigmentation.1,2 Medications commonly cited as causing hyperpigmentation include minocycline, amiodarone, bleomycin, prostaglandins, oral contraceptives, phenothiazine, and antimalarial drugs.1,3 In Addison disease, the pigmentation is typically diffuse, with accentuation in sun-exposed areas, flexures, palmar and plantar creases, and areas of pressure or friction.2 The bronze discoloration of hemochromatosis is from a combination of hemosiderin deposition and increased melanin production.1 Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents with brownish oval-shaped macules and patches. Early lesions may have thin, raised, erythematous borders that typically involve the trunk, but they may spread to the neck, upper extremities, and face.4

The role of minocycline in the treatment of scleroderma is controversial. Early reports involving a small number of patients showed a benefit of minocycline in decreasing symptoms,5,6 but these findings were not achieved in a larger multicenter trial.7

Types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Three types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation occur3,8:

- Type 1—blue-grey coloration on the face in areas of inflammation

- Type 2—blue-grey coloration on normal skin on the skin of the shins and forearms

- Type 3—the least common, characterized by diffuse muddy brown or blue-grey discoloration in sun-exposed areas, as in our patient.

The prevalence of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation varies between 2.4% and 41% and is highest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,9 Type 1 pigmentation is not correlated with treatment duration or cumulative dose, while type 2 and 3 are associated with long-term therapy.8 In type 3, changes are nonspecific, consisting of increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and melanin-only staining dermal melanophages. Types 1 and 2 may resolve slowly, whereas type 3 can persist indefinitely.3,8,10

TREATMENT

Treatment involves early recognition, discontinuation of the drug, and avoidance of sun exposure. Treatment with pigment-specific lasers has shown promise.8,10

- Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults: Part I. Diagnostic approach, café au lait macules, diffuse hyperpigmentation, sun exposure, and phototoxic reactions. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68:1955–1960.

- Thiboutot DM. Clinical review 74: dermatological manifestations of endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80:3082–3087.

- Geria AN, Tajirian AL, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA. Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2009; 17:123–126.

- Schwartz RA. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: the continuing enigma of Cinderella or ashy dermatosis. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:230–232.

- Le CH, Morales A, Trentham DE. Minocycline in early diffuse scleroderma. Lancet 1998; 352:1755–1756.

- Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:267–269.

- Mayes MD, O’Donnell D, Rothfield NF, Csuka ME. Minocycline is not effective in systemic sclerosis: results of an open-label multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:553–557.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. London, UK: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:125–126.

- Roberts G, Capell HA. The frequency and distribution of minocycline induced hyperpigmentation in a rheumatoid arthritis population. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1254–1257.

- Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, Friedman PM. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med 2016; 48:234–237.

- Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults: Part I. Diagnostic approach, café au lait macules, diffuse hyperpigmentation, sun exposure, and phototoxic reactions. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68:1955–1960.

- Thiboutot DM. Clinical review 74: dermatological manifestations of endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80:3082–3087.

- Geria AN, Tajirian AL, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA. Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2009; 17:123–126.

- Schwartz RA. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: the continuing enigma of Cinderella or ashy dermatosis. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:230–232.

- Le CH, Morales A, Trentham DE. Minocycline in early diffuse scleroderma. Lancet 1998; 352:1755–1756.

- Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:267–269.

- Mayes MD, O’Donnell D, Rothfield NF, Csuka ME. Minocycline is not effective in systemic sclerosis: results of an open-label multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:553–557.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. London, UK: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:125–126.

- Roberts G, Capell HA. The frequency and distribution of minocycline induced hyperpigmentation in a rheumatoid arthritis population. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1254–1257.

- Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, Friedman PM. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med 2016; 48:234–237.

In reply: Eruptive xanthoma

In Reply: In our article, we described a patient who presented with markedly elevated triglyceride and hemoglobin A1c. Hypertriglyceridemia might be secondary to underlying diseases, including uncontrolled diabetes, or to inherited lipid disorders. In the optimal situation, our patient would have benefited most not only from strict control of his triglycerides and diabetes, but also from testing for inherited lipid disorders. Although insulin was initiated, he refused fibrates and genetic counseling, and he refused to be reassessed later. After 1 and 3 months, his clinical and laboratory findings had improved dramatically, deterring us from further intervention.

In Reply: In our article, we described a patient who presented with markedly elevated triglyceride and hemoglobin A1c. Hypertriglyceridemia might be secondary to underlying diseases, including uncontrolled diabetes, or to inherited lipid disorders. In the optimal situation, our patient would have benefited most not only from strict control of his triglycerides and diabetes, but also from testing for inherited lipid disorders. Although insulin was initiated, he refused fibrates and genetic counseling, and he refused to be reassessed later. After 1 and 3 months, his clinical and laboratory findings had improved dramatically, deterring us from further intervention.

In Reply: In our article, we described a patient who presented with markedly elevated triglyceride and hemoglobin A1c. Hypertriglyceridemia might be secondary to underlying diseases, including uncontrolled diabetes, or to inherited lipid disorders. In the optimal situation, our patient would have benefited most not only from strict control of his triglycerides and diabetes, but also from testing for inherited lipid disorders. Although insulin was initiated, he refused fibrates and genetic counseling, and he refused to be reassessed later. After 1 and 3 months, his clinical and laboratory findings had improved dramatically, deterring us from further intervention.

Eruptive xanthoma

An obese 50-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, recently diagnosed diabetes, and a history of grand mal seizures presented to the emergency room complaining of skin rash for 1 week. He denied having fever, chills, myalgia, abdominal pain, visual changes, recent changes in medications, or contact with anyone with similar symptoms.

He was a smoker, with a history of 20 pack-years; he denied abusing alcohol and taking illicit drugs.

He had no family history of diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or coronary artery disease. His medications included lisinopril, simvastatin, niacin, metformin, and phenytoin.

On physical examination, the lesions were small, reddish-yellow, nonpruritic tender papules covering the extensor surfaces of the knees, the forearms, the abdomen, and the back (Figure 1). Laboratory test results:

- Total cholesterol 1,045 mg/dL (reference range 100–199)

- Triglycerides 7,855 mg/dL (30–149)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 0.52 mIU/L (0.4–5.5)

- Fasting blood glucose 441 mg/dL (65–100)

- Hemoglobin A1c 12.6% (4.0–6.0)

- Total protein 7.2 g/dL (6.0–8.4)

- Albumin 4 g/dL (3.5–5.0)

- Creatinine 1 mg/dL (0.70–1.40)

- Glomerular filtration rate 79 mL/min/1.73 m2 (> 60)

- Urinalysis showed no proteinuria.

Histologic analysis of a lesion-biopsy specimen showed dermal foamy macrophages and loose lipids, which confirmed the suspicion of eruptive xanthoma.

The patient was started on strict glycemic and lipid control. Metformin and statin doses were increased and insulin was added. Three months later, laboratory results showed total cholesterol 128 mg/dL, triglycerides 164 mg/dL, fasting blood glucose 88 mg/dL, and hemoglobin A1c 5.5%. This was accompanied by marked improvement of the skin lesions (Figure 2).

CAUSES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Eruptive xanthoma is a cutaneous disease most commonly arising over the extensor surfaces of the extremities and on the buttocks and shoulders, and it can be caused by high levels of serum triglycerides and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.1 Hypothyroidism, end-stage renal disease, and nephrotic syndrome can cause secondary hypertriglyceridemia,2 which can cause eruptive xanthoma in severe cases. Patients with eruptive xanthoma may also have ophthalmologic and gastrointestinal involvement, such as lipemia retinalis (salmon-colored retina with creamy-white retinal vessels), abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.3

Other types of xanthoma associated with dyslipidemia include tuberous, tendinous, and plane xanthoma. Tuberous xanthoma is a firm, painless, deeper, red-yellow, larger nodular lesion, and the size may vary.4 Tendinous xanthoma is a slowly enlarging subcutaneous nodule typically located near tendons or ligaments in the hands, feet, and the Achilles tendon. Plane xanthoma is a flat papule or patch that can occur anywhere on the body.

The differential diagnosis includes disseminated granuloma annulare, non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis (xanthoma disseminatum, micronodular form of juvenile xanthogranuloma), and generalized eruptive histiocytoma. Eruptive xanthoma is differentiated from disseminated granuloma annulare by the abundance of perivascular histiocytes and xanthomized histiocytes, the presence of lipid deposits, and the deposition of hyaluronic acid on the edges.5 Xanthoma disseminatum consists of numerous, small, red-brown papules that are evenly spread on the face, skin-folds, trunk, and proximal extremities.6 Juvenile xanthogranuloma occurs mostly in children and is characterized by discrete orange-yellow nodules, which commonly appear on the scalp, face, and upper trunk. It is in most cases a solitary lesion, but multiple lesions may occur.7 Lesions of generalized eruptive histiocytoma are firm, erythematous or brownish papules that appear in successive crops over the face, trunk, and proximal surfaces of the limbs.

TREATMENT

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves dietary restriction, exercise, and drug therapy to control the hyperlipidemia and the diabetes.2 Early recognition and proper control of hypertriglyceridemia can prevent sequelae such as acute pancreatitis.3

- Durrington P. Dyslipidaemia. Lancet 2003; 362:717–731.

- Brunzell JD. Clinical practice. Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1009–1017.

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121:10–12.

- Siddi GM, Pes GM, Errigo A, Corraduzza G, Ena P. Multiple tuberous xanthomas as the first manifestation of autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20:1376–1378.

- Cooper PH. Eruptive xanthoma: a microscopic simulant of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol 1986; 13:207–215.

- Rupec RA, Schaller M. Xanthoma disseminatum. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41:911–913.

- Ferrari F, Masurel A, Olivier-Faivre L, Vabres P. Juvenile xanthogranuloma and nevus anemicus in the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. JAMA Dermatol 2014; 150:42–46.

An obese 50-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, recently diagnosed diabetes, and a history of grand mal seizures presented to the emergency room complaining of skin rash for 1 week. He denied having fever, chills, myalgia, abdominal pain, visual changes, recent changes in medications, or contact with anyone with similar symptoms.

He was a smoker, with a history of 20 pack-years; he denied abusing alcohol and taking illicit drugs.

He had no family history of diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or coronary artery disease. His medications included lisinopril, simvastatin, niacin, metformin, and phenytoin.

On physical examination, the lesions were small, reddish-yellow, nonpruritic tender papules covering the extensor surfaces of the knees, the forearms, the abdomen, and the back (Figure 1). Laboratory test results:

- Total cholesterol 1,045 mg/dL (reference range 100–199)

- Triglycerides 7,855 mg/dL (30–149)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 0.52 mIU/L (0.4–5.5)

- Fasting blood glucose 441 mg/dL (65–100)

- Hemoglobin A1c 12.6% (4.0–6.0)

- Total protein 7.2 g/dL (6.0–8.4)

- Albumin 4 g/dL (3.5–5.0)

- Creatinine 1 mg/dL (0.70–1.40)

- Glomerular filtration rate 79 mL/min/1.73 m2 (> 60)

- Urinalysis showed no proteinuria.

Histologic analysis of a lesion-biopsy specimen showed dermal foamy macrophages and loose lipids, which confirmed the suspicion of eruptive xanthoma.

The patient was started on strict glycemic and lipid control. Metformin and statin doses were increased and insulin was added. Three months later, laboratory results showed total cholesterol 128 mg/dL, triglycerides 164 mg/dL, fasting blood glucose 88 mg/dL, and hemoglobin A1c 5.5%. This was accompanied by marked improvement of the skin lesions (Figure 2).

CAUSES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Eruptive xanthoma is a cutaneous disease most commonly arising over the extensor surfaces of the extremities and on the buttocks and shoulders, and it can be caused by high levels of serum triglycerides and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.1 Hypothyroidism, end-stage renal disease, and nephrotic syndrome can cause secondary hypertriglyceridemia,2 which can cause eruptive xanthoma in severe cases. Patients with eruptive xanthoma may also have ophthalmologic and gastrointestinal involvement, such as lipemia retinalis (salmon-colored retina with creamy-white retinal vessels), abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.3

Other types of xanthoma associated with dyslipidemia include tuberous, tendinous, and plane xanthoma. Tuberous xanthoma is a firm, painless, deeper, red-yellow, larger nodular lesion, and the size may vary.4 Tendinous xanthoma is a slowly enlarging subcutaneous nodule typically located near tendons or ligaments in the hands, feet, and the Achilles tendon. Plane xanthoma is a flat papule or patch that can occur anywhere on the body.

The differential diagnosis includes disseminated granuloma annulare, non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis (xanthoma disseminatum, micronodular form of juvenile xanthogranuloma), and generalized eruptive histiocytoma. Eruptive xanthoma is differentiated from disseminated granuloma annulare by the abundance of perivascular histiocytes and xanthomized histiocytes, the presence of lipid deposits, and the deposition of hyaluronic acid on the edges.5 Xanthoma disseminatum consists of numerous, small, red-brown papules that are evenly spread on the face, skin-folds, trunk, and proximal extremities.6 Juvenile xanthogranuloma occurs mostly in children and is characterized by discrete orange-yellow nodules, which commonly appear on the scalp, face, and upper trunk. It is in most cases a solitary lesion, but multiple lesions may occur.7 Lesions of generalized eruptive histiocytoma are firm, erythematous or brownish papules that appear in successive crops over the face, trunk, and proximal surfaces of the limbs.

TREATMENT

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves dietary restriction, exercise, and drug therapy to control the hyperlipidemia and the diabetes.2 Early recognition and proper control of hypertriglyceridemia can prevent sequelae such as acute pancreatitis.3

An obese 50-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, recently diagnosed diabetes, and a history of grand mal seizures presented to the emergency room complaining of skin rash for 1 week. He denied having fever, chills, myalgia, abdominal pain, visual changes, recent changes in medications, or contact with anyone with similar symptoms.

He was a smoker, with a history of 20 pack-years; he denied abusing alcohol and taking illicit drugs.

He had no family history of diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or coronary artery disease. His medications included lisinopril, simvastatin, niacin, metformin, and phenytoin.

On physical examination, the lesions were small, reddish-yellow, nonpruritic tender papules covering the extensor surfaces of the knees, the forearms, the abdomen, and the back (Figure 1). Laboratory test results:

- Total cholesterol 1,045 mg/dL (reference range 100–199)

- Triglycerides 7,855 mg/dL (30–149)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 0.52 mIU/L (0.4–5.5)

- Fasting blood glucose 441 mg/dL (65–100)

- Hemoglobin A1c 12.6% (4.0–6.0)

- Total protein 7.2 g/dL (6.0–8.4)

- Albumin 4 g/dL (3.5–5.0)

- Creatinine 1 mg/dL (0.70–1.40)

- Glomerular filtration rate 79 mL/min/1.73 m2 (> 60)

- Urinalysis showed no proteinuria.

Histologic analysis of a lesion-biopsy specimen showed dermal foamy macrophages and loose lipids, which confirmed the suspicion of eruptive xanthoma.

The patient was started on strict glycemic and lipid control. Metformin and statin doses were increased and insulin was added. Three months later, laboratory results showed total cholesterol 128 mg/dL, triglycerides 164 mg/dL, fasting blood glucose 88 mg/dL, and hemoglobin A1c 5.5%. This was accompanied by marked improvement of the skin lesions (Figure 2).

CAUSES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Eruptive xanthoma is a cutaneous disease most commonly arising over the extensor surfaces of the extremities and on the buttocks and shoulders, and it can be caused by high levels of serum triglycerides and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.1 Hypothyroidism, end-stage renal disease, and nephrotic syndrome can cause secondary hypertriglyceridemia,2 which can cause eruptive xanthoma in severe cases. Patients with eruptive xanthoma may also have ophthalmologic and gastrointestinal involvement, such as lipemia retinalis (salmon-colored retina with creamy-white retinal vessels), abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.3

Other types of xanthoma associated with dyslipidemia include tuberous, tendinous, and plane xanthoma. Tuberous xanthoma is a firm, painless, deeper, red-yellow, larger nodular lesion, and the size may vary.4 Tendinous xanthoma is a slowly enlarging subcutaneous nodule typically located near tendons or ligaments in the hands, feet, and the Achilles tendon. Plane xanthoma is a flat papule or patch that can occur anywhere on the body.

The differential diagnosis includes disseminated granuloma annulare, non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis (xanthoma disseminatum, micronodular form of juvenile xanthogranuloma), and generalized eruptive histiocytoma. Eruptive xanthoma is differentiated from disseminated granuloma annulare by the abundance of perivascular histiocytes and xanthomized histiocytes, the presence of lipid deposits, and the deposition of hyaluronic acid on the edges.5 Xanthoma disseminatum consists of numerous, small, red-brown papules that are evenly spread on the face, skin-folds, trunk, and proximal extremities.6 Juvenile xanthogranuloma occurs mostly in children and is characterized by discrete orange-yellow nodules, which commonly appear on the scalp, face, and upper trunk. It is in most cases a solitary lesion, but multiple lesions may occur.7 Lesions of generalized eruptive histiocytoma are firm, erythematous or brownish papules that appear in successive crops over the face, trunk, and proximal surfaces of the limbs.

TREATMENT

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves dietary restriction, exercise, and drug therapy to control the hyperlipidemia and the diabetes.2 Early recognition and proper control of hypertriglyceridemia can prevent sequelae such as acute pancreatitis.3

- Durrington P. Dyslipidaemia. Lancet 2003; 362:717–731.

- Brunzell JD. Clinical practice. Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1009–1017.

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121:10–12.

- Siddi GM, Pes GM, Errigo A, Corraduzza G, Ena P. Multiple tuberous xanthomas as the first manifestation of autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20:1376–1378.

- Cooper PH. Eruptive xanthoma: a microscopic simulant of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol 1986; 13:207–215.

- Rupec RA, Schaller M. Xanthoma disseminatum. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41:911–913.

- Ferrari F, Masurel A, Olivier-Faivre L, Vabres P. Juvenile xanthogranuloma and nevus anemicus in the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. JAMA Dermatol 2014; 150:42–46.

- Durrington P. Dyslipidaemia. Lancet 2003; 362:717–731.

- Brunzell JD. Clinical practice. Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1009–1017.

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121:10–12.

- Siddi GM, Pes GM, Errigo A, Corraduzza G, Ena P. Multiple tuberous xanthomas as the first manifestation of autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20:1376–1378.

- Cooper PH. Eruptive xanthoma: a microscopic simulant of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol 1986; 13:207–215.

- Rupec RA, Schaller M. Xanthoma disseminatum. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41:911–913.

- Ferrari F, Masurel A, Olivier-Faivre L, Vabres P. Juvenile xanthogranuloma and nevus anemicus in the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. JAMA Dermatol 2014; 150:42–46.