User login

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

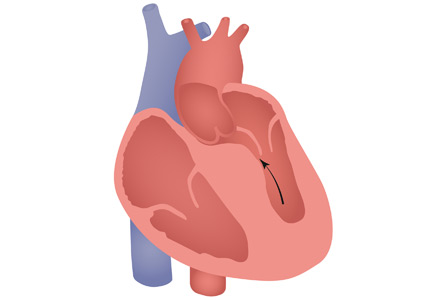

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010